Abstract

Objectives: The profession of dental hygienist is one of the few in which the primary function of the practitioner is to prevent oral disease and to promote the well-being of patients. The aim of this study was to investigate clinical training conditions in schools of dental hygiene in eight countries (the USA, Canada, the UK, Sweden, Denmark, Thailand, South Korea and Japan). Methods: In 2006, we sent out a questionnaire in which we asked dental hygiene schools about how they educate dental hygiene students. Results: The techniques taught to students in schools in Western industrialised nations, such as the USA, Canada, Denmark, the UK and Sweden, were mainly related to dental preventive measures and dental health guidance. By contrast, training schools in South Korea and Japan placed less emphasis on dental preventive measures and dental health guidance. Dental hygienists in Thailand are trained to perform local anaesthesia and to fill and extract deciduous teeth although the country does not have a specific qualification system. Conclusions: The contents of clinical training and education in schools of dental hygiene differ greatly among countries.

Key words: Dental hygienist, education, clinical training

INTRODUCTION

Oral health conditions are closely related to people’s general health, quality of life and lifestyle. There is growing acceptance that oral health is an essential component of total health1. The profession of dental hygienist is one of the few in which the primary function of the practitioner is the prevention of oral disease and the promotion of patient well-being. The dental hygienist plays many different roles, including those of clinician, health promoter, educator, consumer advocate, change agent, administrator, manager and researcher2. Dental hygiene is a licensed profession in many countries and the length of the education programme and number of years of training required vary among countries. In Japan, the length of all dental hygiene training courses was extended from 2 years to 3 years in 2011. In order to accord with international standards, there is a need to improve training programmes. Overall, the number of dental hygienists has increased over the years and clinical dental practice has continued to evolve3. However, it is not clear how training schools implement the clinical and practical teaching that represents the most important component of dental hygienist education.

The aim of the present study was to investigate how dental hygiene students are educated and trained for clinical practice in eight countries around the world.

METHODS

We conducted a cross-sectional survey designed to collect data from training institutions in the USA, Canada, Denmark, the UK, Sweden, Thailand, South Korea and Japan. We selected countries which have very different health and dental care delivery systems in different parts of the world.

The subjects for this survey were the staff of dental hygienist training institutions in those countries. We devised a questionnaire that included items on the level of satisfaction with clinical training and 30 items on clinical and practical training practices and sent this by mail or email to all schools of dental hygiene in the selected countries except the USA and Sweden. For practical reasons we selected to survey schools in two states in the USA (Pennsylvania and Washington) and half of all institutions in Sweden. The survey was conducted in 2006. Target schools were sent a letter describing the study and the questionnaire. When they filled out and sent back the questionnaire, we considered this indicative of their consent to inclusion in the study. We received responses from 110 schools (78.6%) in Japan, one (6.3%) in the USA, 13 (35.1%) in Canada, two (100%) in Denmark, nine (56.2%) in the UK, four (50.0%) in Sweden, six (100%) in Thailand and 33 (62.3%) in South Korea. Data were analysed using chi-squared tests in spss Version 17.0J (SPSS, Inc., Tokyo, Japan). This study was approved by the Ethical Committee of Aichi-Gakuin University, Nagoya, Japan, and conducted in full accordance with the World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki.

RESULTS

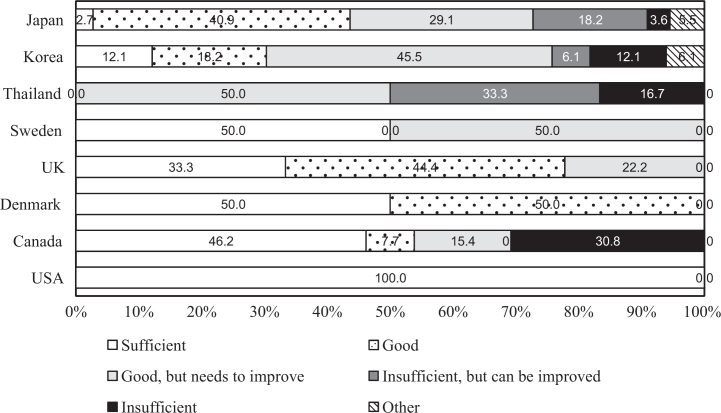

Figure 1 shows the levels of satisfaction with clinical training of dental hygienist educators in eight countries. Only one school in the USA responded to our survey. There was significant difference among levels of satisfaction across countries. (P < 0.001). More than 50% of respondents in the USA, Canada, Denmark, the UK and Sweden rated their level of satisfaction with clinical training as ‘sufficient’ or ‘good’. However, more than 50% of respondents in Thailand, South Korea and Japan rated their level of satisfaction with clinical training as ‘insufficient’ or ‘needs to improve’.

Figure 1.

Levels of satisfaction with clinical training in dental hygienist education in eight countries.

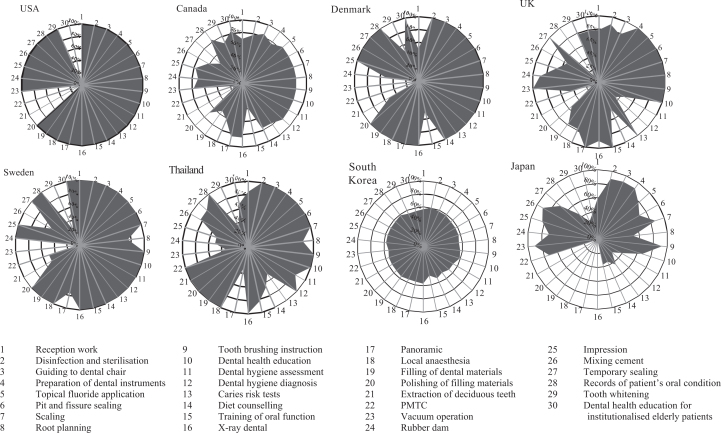

Items pertaining to clinical training in schools of dental hygiene in the eight countries are shown in Table 1 and Figure 2. The three components ‘Disinfection and sterilisation’, ‘Guiding to the dental chair’ and ‘Preparation of dental instruments’ achieved higher scores than all other practices in all countries. In Japan, the percentages of schools that required dental hygienists to perform other tasks (Reception work, Disinfection and sterilisation, Vacuum operation), as well as those indicated by their job specifications, were higher than for other items and compare with data in Figure 2. Clinical training in the responding school in the USA covered almost all training items. No significant difference was found among countries for items such as: ‘Reception work’; ‘Caries risk tests’; ‘Training of oral function’; ‘Polishing of filling materials’; ‘Rubber dam’, and ‘Temporary sealing’. Training in ‘Tooth brushing instruction’ (P < 0.001) and ‘Dental health education’ (P < 0.05) were included in the practical curriculum at almost all training schools in all countries except Japan and South Korea. Training in the prevention of dental caries items ‘Topical fluoride application’ (P < 0.05) and ‘Pit and fissure sealing’ (P < 0.05) was conducted within clinical training in < 60% of schools in South Korea and < 70% of schools in Japan. Training in the preventive periodontal disease item ‘Root planning’ (P < 0.05) was carried out in > 80% of schools in the USA, Canada, Denmark, the UK and Sweden, but in only about 50% of schools in Japan and South Korea. Clinical training in ‘Diet counselling’ (P < 0.001) was delivered in > 80% of schools in the USA, the UK and Sweden, but in < 30% of schools in Japan. Figure 2 shows radar charts that give percentages indicating how much each clinical training item is included in the curriculum in each country. The radar charts for the respective countries have distinct characteristics. The charts for Denmark, Sweden and the USA show similar patterns that indicate schools in these countries tend to provide more education on dental health guidance and dental treatment. The charts for the UK, Thailand and Japan show similar patterns, indicating that more training is provided on preventive dentistry and assisting dentists. The charts for South Korea and Japan show that clinical training items are included to a lesser extent than in other countries.

Table 1.

Items in clinical training in eight countries

| No. | Item | USA | Canada | Denmark | UK | Sweden | Thailand | South Korea | Japan | χ2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % (n) | % (n) | % (n) | % (n) | % (n) | % (n) | % (n) | % (n) | |||

| 1 | Reception work | 100 (1) | 69.2 (9) | 100 (1) | 33.3 (3) | 100 (4) | 83.3 (5) | 60.4 (30) | 60.6 (60) | NS |

| 2 | Disinfection and sterilisation | 100 (1) | 76.9 (10) | 100 (2) | 77.8 (7) | 100 (4) | 100 (6) | 58.5 (32) | 80.8 (80) | † |

| 3 | Guiding to dental chair | 100 (1) | 84.6 (11) | 100 (2) | 88.9 (8) | 100 (4) | 100 (6) | 58.5 (31) | 81.8 (81) | ‡ |

| 4 | Preparation of dental instruments | 100 (1) | 76.9 (10) | 100 (2) | 77.8 (7) | 100 (4) | 100 (6) | 56.6 (31) | 81.8 (81) | ‡ |

| 5 | Topical fluoride application | 100 (1) | 84.6 (11) | 100 (2) | 100 (9) | 100 (4) | 100 (6) | 56.6 (30) | 67.7 (67) | * |

| 6 | Pit and fissure sealing | 100 (1) | 84.6 (11) | 100 (2) | 100 (9) | 100 (4) | 100 (6) | 56.6 (30) | 64.6 (64) | * |

| 7 | Scaling | 100 (1) | 84.6 (11) | 100 (2) | 100 (9) | 75.0 (4) | 100 (6) | 54.7 (30) | 79.8 (79) | ‡ |

| 8 | Root planning | 100 (1) | 84.6 (11) | 100 (2) | 100 (9) | 100 (3) | 83.3 (5) | 56.6 (29) | 46.5 (46) | * |

| 9 | Tooth brushing instruction | 100 (1) | 84.6 (11) | 100 (2) | 100 (9) | 100 (4) | 100 (6) | 58.5 (30) | 79.8 (79) | ‡ |

| 10 | Dental health education | 100 (1) | 84.6 (11) | 100 (2) | 100 (9) | 100 (4) | 100 (6) | 52.8 (31) | 49.5 (49) | * |

| 11 | Dental hygiene assessment | 100 (1) | 84.6 (11) | 100 (2) | 100 (9) | 100 (4) | 83.3 (5) | 52.8 (28) | 24.2 (24) | ‡ |

| 12 | Dental hygiene diagnosis | 100 (1) | 84.6 (11) | 100 (2) | 44.4 (4) | 100 (4) | 100 (6) | 49.1 (28) | 22.2 (22) | ‡ |

| 13 | Caries risk tests | 0.0 (0) | 76.9 (10) | 100 (2) | 33.3 (3) | 100 (4) | 50.0 (3) | 52.8 (26) | 39.4 (39) | NS |

| 14 | Diet counselling | 100 (1) | 76.9 (10) | 50.0 (2) | 100 (9) | 100 (4) | 66.7 (4) | 45.3 (28) | 29.3 (29) | ‡ |

| 15 | Training of oral function | 100 (1) | 38.5 (5) | 100 (1) | 44.4 (4) | 100 (4) | 83.3 (5) | 56.6 (24) | 20.2 (20) | NS |

| 16 | X-ray dental | 100 (1) | 84.6 (11) | 100 (2) | 100 (9) | 75.0 (4) | 100 (6) | 54.7 (30) | – (–) | ‡ |

| 17 | Panoramic | 100 (1) | 84.6 (11) | 100 (2) | 88.9 (8) | 100 (4) | 33.3 (2) | 54.7 (29) | – (–) | ‡ |

| 18 | Local anaesthesia | 100 (1) | 61.5 (8) | 100 (2) | 100 (9) | 100 (4) | 100 (6) | 56.6 (29) | – (–) | ‡ |

| 19 | Filling of dental materials | 100 (1) | 53.8 (7) | 100 (2) | 77.8 (7) | 100 (4) | 100 (6) | 54.7 (30) | – (–) | ‡ |

| 20 | Polishing of filling materials | 100 (1) | 69.2 (9) | 50.0 (2) | 77.8 (7) | 50.0 (4) | 100 (6) | 54.7 (29) | 57.6 (57) | NS |

| 21 | Extraction of deciduous teeth | 0.0 | 15.4 (2) | 0.0 (1) | 55.6 (5) | 50.0 (2) | 100 (6) | 54.7 (29) | – (–) | ‡ |

| 22 | PMTC | 0.0 | 15.4 (2) | 0.0 (0) | 11.1 (1) | 0.0 (2) | 100 (6) | 52.8 (29) | 62.6 (62) | ‡ |

| 23 | Vacuum operation | 100 (1) | 76.9 (10) | 50.0 (0) | 44.4 (4) | 100 (0) | 33.3 (2) | 56.6 (28) | 79.8 (79) | ‡ |

| 24 | Rubber dam | 100 (1) | 69.2 (9) | 100 (1) | 100 (9) | 100 (4) | 50.0 (3) | 56.6 (30) | 61.6 (61) | NS |

| 25 | Impression | 100 (1) | 76.9 (10) | 100 (2) | 88.9 (8) | 50.0 (4) | 50.0 (3) | 56.6 (30) | 73.7 (73) | * |

| 26 | Mixing cement | 100 (1) | 61.5 (8) | 100 (2) | 66.7 (6) | 100 (2) | 83.3 (5) | 56.6 (30) | 79.8 (79) | ‡ |

| 27 | Temporary sealing | 100 (1) | 46.2 (6) | 100 (2) | 55.6 (5) | 100 (4) | 83.3 (5) | 58.5 (30) | 66.7 (66) | NS |

| 28 | Records of patients oral condition | 100 (1) | 84.6 (11) | 50.0 (2) | 100 (9) | 25.0 (4) | 100 (6) | 54.7 (31) | 37.4 (37) | ‡ |

| 29 | Tooth whitening | 100 (1) | 69.2 (9) | 100 (1) | 11.1 (1) | 100 (1) | 33.3 (2) | 54.7 (29) | 27.3 (27) | † |

| 30 | Dental health education for institutionalised elderly patients | – (–) | 84.6 (11) | 100 (2) | 77.8 (7) | 75.0 (4) | 66.7 (4) | 48.5 (29) | 16.2 (16) | ‡ |

P < 0.05, †P < 0.01, ‡P < 0.001.

NS, not significant; PMTC, professional mechanical tooth cleaning.

Figure 2.

Comparison of clinical training in eight countries. PMTC, professional mechanical tooth cleaning.

DISCUSSION

In European countries, dental hygienists are trained to acquire core skills in prevention and oral health promotion, including in periodontal therapy4. In 1949, dental hygienists in Japan were initially educated as health workers who worked at health centres5. Data for 2008 show that about 91% of dental hygienists worked in dental offices as clinicians6. Nakagaki et al.7 reported that dental hygiene students were given priority training in assisting in dental examination. Fewer dental hygienists are employed in Japan and South Korea than in European countries3. Although Thailand does not have a dental hygienist training programme, schools in Thailand train dental nurses to provide health care interventions. Thus, the discrepancies between the education and employment of dental hygienists resulted in differing levels of satisfaction in Asian and Western countries.

The items of clinical and practical training listed in the questionnaire were classified under the four categories of: dental examination assistance; dental preventive measures; dental health guidance, and dental treatments. Western industrialised nations, such as Canada, Denmark, Sweden and the USA, provided students mainly with training in dental preventive measures and dental health guidance. By contrast, schools in the UK and Japan taught dental preventive practices and trained students to assist in dental examination. Schools in Thailand, which train dental nurses to provide health care interventions, offered training mainly in dental preventive practices and dental treatments. This difference in the dental professions system resulted in training curricula with different contents. Some respondents did not understand the meaning of ‘PMTC’, which was included among the items listed in the questionnaire; this suggests that the term is not commonly used in countries other than Japan. In Japan, ‘PMTC’ is a widely known acronym for ‘professional mechanical tooth cleaning’, which refers to the polishing of the tooth surface with power-driven instruments. Under the traditional models of care, the dentist is responsible for deciding which services a dental hygienist should provide3. However, there has been an increasing shift to collaborative practice in which the dentist and dental hygienist together decide on the services to be administered and direct supervision of the hygienist is not required3. In Japan and in part of South Korea, the dentist decides all the dental hygiene procedures to be provided and is always onsite3 when the dental hygienist performs them. In Denmark, Sweden and part of Canada, the dental hygienist decides on which dental hygiene services should be administered, in collaboration with the client but without the dentist3. In the UK, the USA, and parts of South Korea and Canada, the dental hygienist and dentist together decide on dental hygiene services3. Therefore, training practices for dental hygiene students vary according to the dental hygienist regulation system in place in each country.

Johnson8 reported that as the profession of dental hygienist has evolved, it has remained remarkably consistent globally, particularly in terms of its scope of clinical practice. Öhrn et al.9 revealed that the length of dental hygiene education is a key factor in influencing the application of research findings to practice. In 1998, in order to facilitate a better curriculum for the dental hygienist, the House of Delegates of the International Federation of Dental Hygiene (IFDH) Education Committee proposed model curricula for 2-, 3- and 4-year dental hygiene programmes10. Blitz and Hovius10 claimed that international standards for dental hygienist education could not be tailored to fit all countries, but indicated a need to develop an appropriate training programme for dental hygienists in each country. In this study, dental hygienist education in Asian countries differed from that in other countries. In Japan, as the dental hygiene training course has recently been extended from 2 to 3 years, there is an urgent need to improve clinical training programmes in order to ensure they are of a similar standard to programmes elsewhere in the world.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Professor Dowen Birkhed (Department of Cariology, Sahlgrenska Academy, Gothenburg University, Gothenburg, Sweden), Associate Professor Kim Baek Il (Department of Preventive Dentistry, Yonsei University, Yonsei, South Korea) and Professor Komkham Pattanaporn (Department of Community Dentistry, Faculty of Dentistry, Chiang Mai University, Chiang Mai, Thailand) for their kind support of the survey reported in this paper. This study was funded by a grant-in-aid for research on medical safety and health technology from the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare, Japan, 2006 (H18-health care-general-049).

Conflicts of interest

None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Peterson PE. The World Oral Health Report 2003: continuous improvement of oral health in the 21st century: the approach of the WHO Global Oral Health Programme. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2003;31(Suppl. 1):3–24. doi: 10.1046/j..2003.com122.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mueller-Joseph L, Homenko DF, Wilkins EM. In: Clinical Practice of the Dental Hygienist. 9th edn. Wilkins EM, editor. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; Baltimore, MD: 2005. The professional dental hygienist; pp. 3–14. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Johnson PM. International profiles of dental hygiene 1987 to 2006: a 21-nation comparative study. Int Dent J. 2009;59:63–77. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Luciak-Donsberger C, Eaton KA. Dental hygienists in Europe: trends towards harmonisation of education and practice since 2003. Int J Dent Hyg. 2009;7:273–284. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-5037.2009.00402.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yoshida N, Endo K, Komaki M. Dental hygiene education in Japan: present status and future directions. Int J Dent Hyg. 2004;2:179–184. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-5037.2004.00097.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Japan Health Statistics Office, Vital and Health Statistics Division. Report on Public Health Administration and Services. 2008. http://www.mhlw.go.jp/toukei/saikin/hw/eisei/08-2/index.html [Accessed 24 December 2011]

- 7.Nakagaki H, Matsui K, Matsuda Y, et al. Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare; Tokyo: 2006. A Study on Goals and Achievement Levels of Clinical and Practical Trainings as Part of Dental Hygienist Education. A Comprehensive Study Report Supported by Grant-In-Aid for Research Project on Medical Safety and Health Technology. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Johnson PM. International profiles of dental hygiene 1987 to 2001: a 19-nation comparative study. Int Dent J. 2003;53:299–313. doi: 10.1111/j.1875-595x.2003.tb00763.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Öhrn K, Olsson C, Wallin L. Research utilisation among dental hygienists in Sweden – a national survey. Int J Dent Hyg. 2005;3:104–111. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-5037.2005.00135.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Blitz P, Hovius M. Towards international curriculum standards. Int J Dent Hyg. 2002;1:57–61. doi: 10.1034/j.1601-5037.2003.00009.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]