Abstract

Although improvements in certain oral health measures have been achieved, many global oral health matters and challenges exist. Collaborations and partnerships among various institutions are crucial in solving such problems. The main aim of the present study was to analyse the nature and extent of the partnership between dental faculties and National Dental Associations (NDAs). A questionnaire was developed, focusing on the relationship between NDAs and dental faculties within the World Dental Federation-European Regional Organization (FDI-ERO) zone with regard to major professional activities, such as dental education (both undergraduate and continuing education), workforce issues, improvement of national oral health, and science and knowledge transfer. The questionnaire was sent to all member NDAs within the ERO zone. The response rate was 21/41 (53.65%). The major activities in which NDAs were found to be involved were improvement of national oral health (100%), followed by continuing education activities (90%), whereas the activity which received least involvement was the development of an undergraduate dental curriculum (52%). The NDAs perceived their relationship with dental faculties to be quite satisfactory in the fields of continuing education, science and knowledge transfer, and the implementation of new technologies into daily dental practice. However, it was suggested that their relationship needed significant improvement with regard to the development of an undergraduate dental education curriculum, dental workforce issues and negotiations with the authorities regarding professional matters/issues. As the two important elements of organised dentistry, NDAs and dental faculties have a significant role to play in the improvement of oral health and in finding solutions to global oral health challenges; therefore, their collaboration and partnership are crucial for this purpose. On the basis of the perceptions of NDAs regarding their relationship with dental faculties, it can be concluded that their partnership can and should be further improved.

Key words: Collaboration, dental associations, dental faculties, oral health policy

INTRODUCTION

It is clear that, in general, the context of health and the provision of health care are complex issues with a wide variety of determinants (e.g. social, economical, cultural, professional, educational, political, etc.)1., 2.. Further, many health professions, payers, institutional organisations, governmental bodies, nongovernmental organisations and private sectors, each having their own weaknesses and strengths, are involved, and their interaction in the form of partnerships and collaboration is crucial for the improvement of health and the provision of healthcare services3., 4., 5., 6., 7., 8.. Increasing areas of collaboration and widening extents of partnerships between various health professions, health disciplines, specialities, governmental and nongovernmental organizations and health professionals are both expected and experienced each day and in every field of health3., 4., 5., 6., 7.. Partnerships in translation for advancing research and clinical care are likely to be important areas in which further interaction is needed9, and community health efforts also require similar collaboration, partnerships and synergy among various stakeholders6. The same is true with regard to oral health and oral health services5., 10., 11., 12..

Partnerships for improved oral health have been part of community health efforts for many years and in many countries. When the knowledge, skills and resources that are held by specific groups and organizations are combined into a larger entity of a partnership or coalition, a greater impact on oral health issues may be possible5., 11.. It is clear that the public’s access to oral health care can be improved through partnerships (e.g. partnerships among dental schools, oral health providers and communities), that dental–medical collaborations can reduce oral health disparities11 and that partnership particularly benefits the disadvantaged or underserved groups6., 12.. However, partnerships and collaboration in health and oral health arenas may not reach the desired extent at all levels, especially with regard to the gap between research and practice, societal needs and the need to promote civic engagement and social responsibility in health care3., 10., 13., 14.. As an example, interprofessional education should be key to the partnership of health professionals; however, the currently applied educational model does not seem to promote such interprofessional education; many barriers have been described to interprofessional education and dental students are rarely involved13.

As the two major actors and members of organized/institutionalized dentistry, the extent and success of professional collaboration between dental faculties and National Dental Associations (NDAs) may deserve particular interest at this point. This relationship is likely to be multifactorial, including various aspects of dental education, dental practice, public health and individual health of patients, and thus there are many areas in which efficient collaboration and partnership may be required.

The aim of the present study was to evaluate the areas of collaboration between dental faculties and NDAs within the World Dental Federation-European Regional Organization (FDI-ERO) zone. Further, particular identification of the areas requiring improved partnership, and suggestions and recommendations for such improvements, were also attempted.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The present study was conducted by the ERO Working Group entitled, ‘The Relationship Between Dental Practitioners and Universities’, in 2010–2011. A questionnaire (Figure 1) was developed and approved by the Working Group members to analyse the various important elements of the relationship between dental faculties and NDAs in countries which are members of FDI-ERO. Questions mainly focused on the potential relationship between NDAs and dental faculties in the following areas: undergraduate dental education, continuing professional development, knowledge and science transfer, professional and political matters, and oral health workforce issues. As the perpective of NDAs with regard to their relationship with dental faculties was investigated, the questionnaire was sent to the contact persons of a total of 41 NDAs.

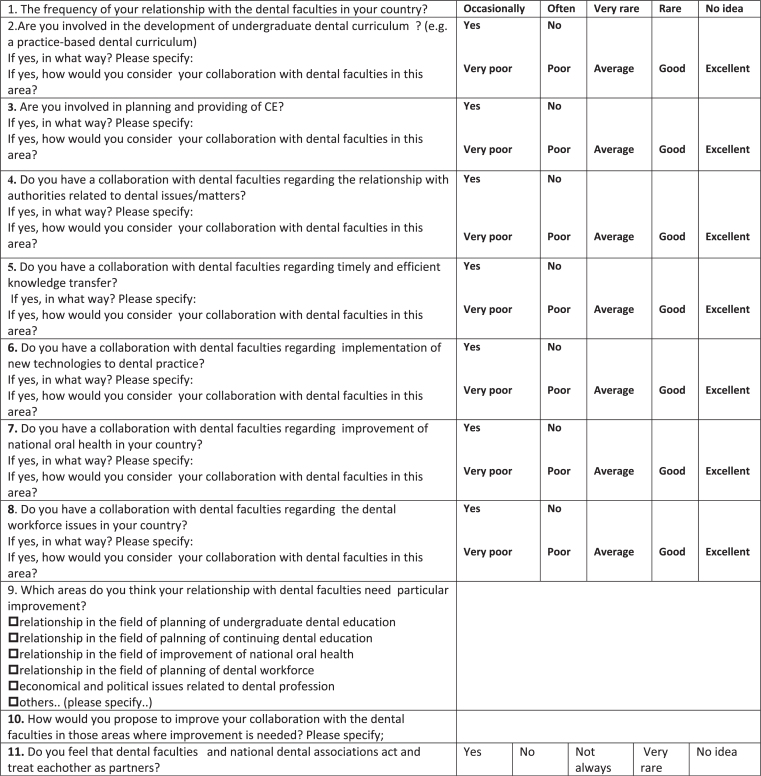

Figure 1.

Questionnaire: analysis of the nature and extent of collaboration between National Dental Associations (NDAs) and dental faculties in the European Regional Organization (ERO) zone.

RESULTS

A total of 22 countries and member NDAs responded: Austria, Croatia (Croatian RD), Czech Republic, Cyprus, Denmark, Estonia, France, Georgia, Italy (AIO), Israel, Kyrgiz Republic, the Netherlands, Poland, Portugal, Romania, Russia, Slovakia, Slovenia, Spain, Switzerland, Turkey and Uzbekistan. However, as Cyprus responded and stated that there were no dental faculties in their country, the response rate was calculated as 21/41 (53.65%).

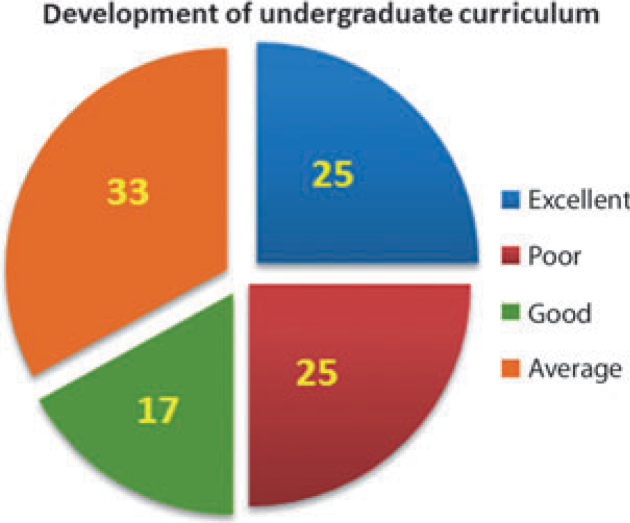

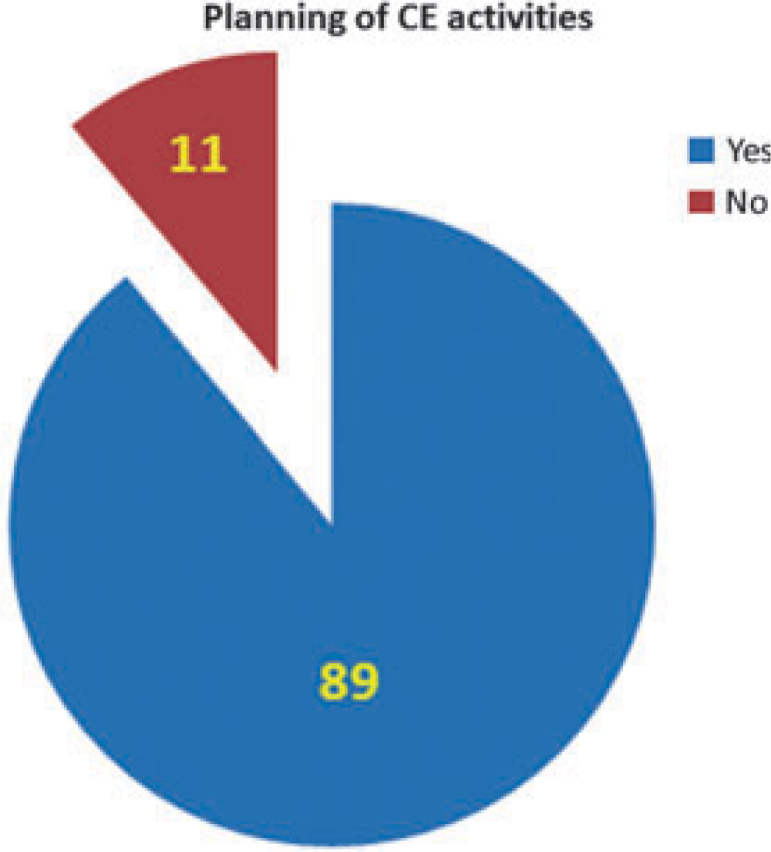

When the member NDAs were asked to consider the frequency of their relationship with dental faculties in their country, 33% answered that it was ‘occasional’, 24% that it was ‘very often’ and 43% that it was ‘often’. Table 1 demonstrates the areas in which NDAs in Europe were mainly involved. All NDAs (100%) were involved in the improvement of national oral health, followed by continuing education (CE) activities (90%); the least involved activity was the development of an undergraduate curriculum (52%). When NDAs responded ‘Yes’ to any of the professional activities that were mentioned in the questionnaire, they also provided detailed information with regard to these professional activities and how they collaborated with dental faculties. In the development of an undergraduate dental curriculum (Figure 2), the NDAs stated that this was as a consultant, especially when changes were proposed (Austria), or for hearings (Italy) or bilateral discussions (Israel), or, more directly, for discussing student educational programmes and for the development of specialisation programmes (Russia). CE activities (Figure 3) and the planning and/or provision of CE was an area in which NDAs played a more active role and had a good relationship with dental faculties. In some countries (e.g. Austria, France, Italy, Slovakia, Poland), this was a legal status for the NDA. In most countries in Europe, many providers were available in the field of CE (e.g. Switzerland, Czech Republic, Spain). However, NDAs frequently organised CE activities (seminars, congresses, symposiums, web-based courses, etc.) in cooperation with dental faculties/universities.

Table 1.

Professional areas in which National Dental Associations (NDAs) within the European Regional Organization (ERO) zone are mainly involved (%)

| Main activities of NDAs | % |

|---|---|

| Improvement of national oral health | 100 |

| Provision of continuing education | 90 |

| Planning of continuing education | 89 |

| Negotiations with authorities (economical and political matters) | 86 |

| Knowledge transfer | 75 |

| Dental workforce issues | 67 |

| Implementation of new technologies | 62 |

| Development of undergraduate curriculum | 52 |

Figure 2.

Perceived nature of the relationship between National Dental Associations (NDAs) and dental faculties with regard to the development of an undergraduate dental education curriculum (values are percentages).

Figure 3.

The extent of participation of National Dental Associations (NDAs) within the European Regional Organization (ERO) zone with regard to the planning of continuing education (CE) activities (values are percentages).

NDAs generally participated in negotiations with the authorities with regard to CE, vocational training, patient safety, prevention, agreements with the social security system, infrastructure, problems of dental students and oral health programmes. In some countries (e.g. Austria), NDAs were the only organisations legitimized to negotiate with the authorities with regard to the interests of dentists as a whole; in others, they were involved in negotiations in an advisory capacity (e.g. Israel, the Netherlands). NDAs were also actively involved in knowledge transfer, mainly through meetings, congresses, web sites, journals, e-mail, SMS network, publishing of dental books (Czech Republic), national CE programmes (Italy), public announcements and press notices (Israel). All NDAs participated in preventative programmes and activities aimed at improving public awareness of oral health issues. Dental workforce issues were also an area in which NDAs played a role. For example, in Turkey, the NDA is conducting studies and workshops on the employment and unemployment of dentists, and in Spain, Slovakia and Austria, NDAs maintain the registration and licensing of dentists. In France, the NDA is actively involved in rethinking and redefining the ‘Dental Team’, and the roles and responsibilities of each of its members, and also conducts work on workforce demographics and the continuity of care. In other countries (e.g. Austria, the Netherlands), NDAs are also part of the decision-making process with regard to the quota for students of dentistry.

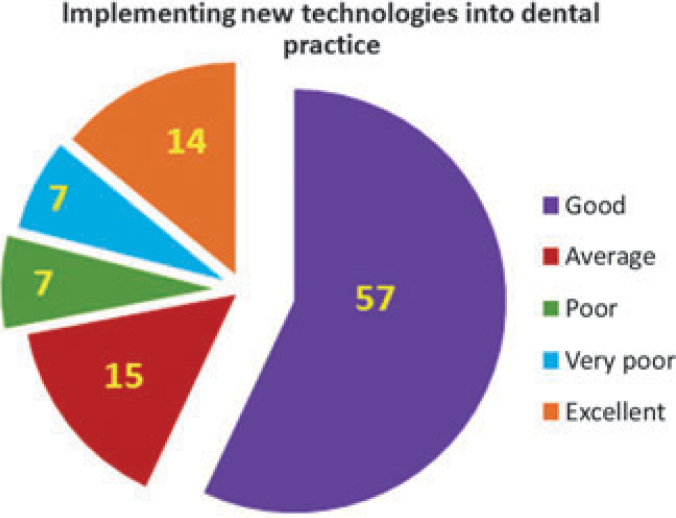

In Table 2, we see how NDAs perceive their relationship/collaboration with dental faculties in their country with regard to particular professional activities and tasks. When the sum of the excellent and good results was considered, it was found that the implementation of new technologies into dental practice (71%) (Figure 4) and the planning of CE (71%) were the two areas in which NDAs felt that they had a good partnership with dental faculties. Dental workforce issues (50%), development of an undergraduate dental curriculum (42%) and negotiations with authorities regarding economical/political matters (44%) were areas in which NDAs were not totally satisfied with their collaboration with dental faculties (<50%). Table 3 shows the professional areas that require improved collaboration between NDAs and dental faculties. All areas, except the planning of CE (7%), are suggested to require a similar level of improvement (17–19%). NDAs suggested that the active cooperation of dental faculty management personnel, the appointing of members of the profession (NDAs) to the governing bodies of universities, the achievement of a tighter contact between counterparts, the establishment of mutual working groups, the stimulation of cooperation with prominent scientists and professors, greater collaboration in dental force planning and student intake, and regular exchanges and joint meeting/activities could help to further improve the professional partnership between NDAs and dental faculties.

Table 2.

Perceived relationship of National Dental Associations (NDAs) with dental faculties in the European Regional Organization (ERO) zone (%)

| Area of collaboration | Excellent | Good | Very poor | Poor | Average |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Improvement of national oral health | 10 | 57 | 9 | 14 | 10 |

| Provision of continuing education | 21 | 37 | 5 | 5 | 32 |

| Planning of continuing education | 24 | 47 | N.A. | 6 | 23 |

| Economical, political matters | 11 | 33 | N.A. | 17 | 39 |

| Knowledge transfer | 20 | 47 | N.A. | 13 | 20 |

| Dental workforce issues | 14 | 36 | 7 | 14 | 29 |

| Implementation of new technologies | 14 | 57 | 7 | 7 | 15 |

| Development of undergraduate curriculum | 25 | 17 | N.A. | 25 | 33 |

N.A., not applicable.

Figure 4.

Perceived partnership with dental faculties with regard to the implementation of new technologies into dental practice (values are percentages).

Table 3.

Professional areas that require improved collaboration between National Dental Associations (NDAs) and dental faculties in the European Regional Organization (ERO) zone

| Area of collaboration | % |

|---|---|

| Economical, political matters | 19 |

| Development of undergraduate curriculum | 19 |

| Dental workforce issues | 19 |

| Provision of continuing education | 19 |

| Improvement of national oral health | 17 |

| Planning of continuing education | 7 |

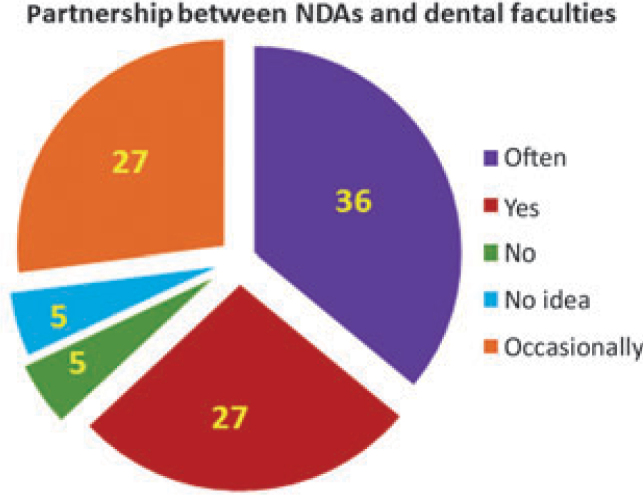

Although the majority (63%) felt that counterparts treated each other as partners, some NDAs stated that a real partnership was not evident (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Responses of National Dental Associations (NDAs) with regard to the partnership between NDAs and dental faculties (values are percentages).

DISCUSSION

Different educational and professional developments within the dental field create different sets of missions, norms and practices with regard to dental diseases and their appropriate treatment15. Agencies and individuals interested in making improvements in oral health status in any particular target group may begin a process of working with others who have an interest in improving the health and well-being of that target group. In a world that is increasingly synergistic and mutually dependent, improvements in oral health can be advanced by considering the elements of successful coalition building and by forming partnerships with multiple organizations and individuals5. Collaborative partnerships (people and organizations from multiple sectors working together in a common purpose) are a prominent strategy for community health improvement6., 11.. Thus, it is important develop efficient partnerships, and there are clearly defined compelling reasons for professionals in health and human services administration to collaborate with other stakeholders in the community. However, there are also barriers to such collaboration, and experiences with such partnerships may not always generate positive outcomes: recent research on partnership synergy – a key indicator of a successful collaboration process – has suggested that many of these partnerships are inadvertently compromising their own success by the way in which they involve community stakeholders13.

The present study has revealed that NDAs and dental faculties within the ERO zone have many activities in common. They have relationships in a wide array of professional areas, including continuing professional development, knowledge and science transfer, dental workforce issues and improvement of oral health at the national level. Improvement in national oral health is considered to be an important area in which synergy between various stakeholders is required, and increased collaboration with the public health sector and bold leadership in dental education are advocated11. As 100% of NDAs are involved in activities attempting to improve public oral health in their countries, an improved partnership with dental faculties would be in line with public benefits and professional principles and missions.

In general, the relationship with dental faculties was found to be satisfactory by NDAs in many dental fields. The best level of partnership was observed in collaboration for the planning of CE, the implementation of new technologies into dental practice and knowledge transfer. However, not all partnerships and collaborations have been succesful with positive outcomes13. It has even been suggested that experience with such partnerships, thus far, has generated frustration rather than results13. Our survey has indicated that NDAs are not totally satisfied with their relationship with dental faculties, and has underlined that their relationship requires improvement in certain professional areas. Greater support and collaboration are expected from dental faculties in the development of an undergraduate curriculum, dental workforce issues and in negotiating professional matters with authorities. The ability of a partnership to understand and address complex problems – and to sustain interventions over time – has been suggested to be related to who is involved in the partnership, how community stakeholders are involved, and the leadership and management of the partnership13. In this recent survey, participating NDAs have suggested that further improvement of the collaboration between NDAs and dental faculties is required.

There are many neglected global oral health issues and matters (e.g. the impact of oral health on general health, economic dimensions of oral diseases, burden of oral diseases and the inequalities in oral health care, barriers to oral healthcare services, workforce challenges, etc.), and world figures are not positive with regard to oral health and diseases.16., 17.. Even in developed countries, there are underserved populations and disparities in oral health care17., 18., and the situation is becoming even worse globally17. Furthermore, all the available data and statistics demonstrate that a variety of health actions need to be taken to solve these matters16., 17., 18.. Therefore, the collaboration between dental faculties and NDAs is crucial in solving these problems.

As a profession, dentistry has the responsibility to serve all the community, and the mission of many professional dental organisations is to improve oral health for all7., 8., 18., 19.. However, the role and mission of dental faculties can be redefined based on concepts such as professionalism, social justice, moral competency and changing expectations from dentists7., 8., 19., 20.. The public expects the new professionals from dental schools to have a certain level of expertise, but also to use it with integrity and public interest, which may require social awareness and concern about national and global dental problems20. Thus, it is natural that the profession (both the individual dentists and all components of organised dentistry) should be expected to be concerned for these problems and to take a leading role in addressing such matters and issues, and in advocating oral health7., 8., 19., 20.. The present study has revealed that all NDAs are involved in the improvement of oral health in their country; most NDAs are also involved in workforce issues and have a certain level of relationship with dental faculties in these fields. However, it is also obvious that greater collaboration is needed among everyone involved in dentistry to further improve public oral health at both a national and global level. This is reflected in this survey, as NDAs listed improvement in national oral health (17%) and dental workforce issues (19%) among the fields in which better partnerships between NDAs and dental faculties are needed.

Although this study was conducted in Europe, it is possible that there may be certain similarities between the relationship of NDAs and dental faculties in different parts of the world. This may be an issue worth analysing through a more global approach. Nevertheless, it is also important to consider the conditions and factors that may determine whether collaborative partnerships are effective3., 4., 6.. Thus, there is a need for regular analysis of the trends in collaborative partnerships in the oral health arena.

The present study highlights the importance of active cooperation between NDAs and dental faculties – the two major institutions in the oral health arena. Furthermore, the results may be considered as important as they aid counterparts to better understand the needs/demands of one another and serve as a guide to identify efficient ways of improving their relationship.

Acknowledgements

This project was developed by the ERO Working Group ‘The Relationship Between Dental Practitioners and Universities’. The authors wish to thank all members of the Working Group and Monica Lang for their kind support. The authors are also grateful to all the NDAs within the ERO zone who responded to the questionnaire.

REFERENCES

- 1.Gilson L, Sen PD, Mohammed S, et al. The potential of health sector non-governmental organizations: policy options. Health Policy Plan. 1994;9:14–24. doi: 10.1093/heapol/9.1.14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gellert GA. Non-governmental organizations in international health: past successes, future challenges. Int J Health Plann Manage. 1996;11:19–31. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1099-1751(199601)11:1<19::AID-HPM412>3.0.CO;2-#. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dewa CS, Trojanowski L, Cheng C et al. Lessons from a Canadian province: examining collaborations between the mental health and justice sectors. Int J Public Health 2011; DOI:10.1007/s00038-011-0268-2. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.Woodford JD. Synergies between veterinarians and para-professionals in the public and private sectors: organisational and institutional relationships that facilitate the process of privatising animal health services in developing countries. Rev Sci Tech. 2004;23:115–135. doi: 10.20506/rst.23.1.1472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Beaulieu E. Partnerships for better oral health. Int J Dent Hyg. 2003;1:101–104. doi: 10.1034/j.1601-5037.2003.00022.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Roussos ST, Fawcett SB. A review of collaborative partnerships as a strategy for improving community health. Annu Rev Public Health. 2000;21:369–402. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.21.1.369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Masella RS. Renewing professionalism in dental education. J Dent Educ. 2007;71:205–216. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dharamsi S, Pratt DD, MacEntee MI. How dentists account for social responsibility, economic imperatives and professional obligations. J Dent Educ. 2007;71:1583–1592. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Greenlee RT, Coleman LA, Nelson AF, et al. Partnerships in translation: advancing research and clinical care. The 14th Annual HMO Research Network Conference, April 13–16, 2008, Minneapolis, Minnesota. Clin Med Res. 2008;6:109–112. doi: 10.3121/cmr.2008.842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hood JG. Service-learning in dental education: meeting needs and challenges. J Dent Educ. 2009;73:454–463. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mouradian WE, Huebner C, DePaola D. Addressing health disparities through dental–medical collaborations, Part III: leadership for the public good. J Dent Educ. 2004;68:505–512. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rafter ME, Pesun IJ, Herren M, et al. A preliminary survey of interprofessional education. J Dent Educ. 2006;70:417–427. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.DeAngelis S, Warren C. Establishing community partnerships: providing better oral health care to underserved children. J Dent Hyg. 2001;75:310–315. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lasker RD, Weiss ES. Creating partnership synergy: the critical role of community stakeholders. J Health Hum Serv Adm. 2003;26:119–139. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wu ZY, Zhang ZY, Jiang XQ, et al. Comparison of dental education and professional development between mainland China and North America. Eur J Dent Educ. 2010;14:106–112. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0579.2009.00599.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Beaglehole R, Benzian H, Crail J, et al. FDI World Dental Federation, Myriad Editions; Brighton, UK: 2009. The Oral Health Atlas: Mapping a Neglected Global Health Issue. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jos VM, Welie JWM. In: Justice in Oral Health Care: Ethical and Educational Perspectives. Welie JWM, editor. Marquette University Press; Milwaukee: 2006. Are oral health disparities merely unfortunate or also unfair? An introduction to the book; pp. 7–14. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ottolenghi L, Bourgeois DM. Oral Health Interviews and Clinical Surveys: Overviews. Quintessenza Edizioni Srl; Milan: 2008. Health surveillance in Europe 2008. European global oral health indicators development project. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Niessen LC. In: Justice in Oral Health Care: Ethical and Educational Perspectives. Welie JWM, editor. Marquette University Press; Milwaukee: 2006. Oral health and social justice: oral health status, financing and opportunities for leadership; pp. 215–232. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rule JT, Welie JVM. In: Justice in Oral Health Care: Ethical and Educational Perspectives. Welie JWM, editor. Marquette University Press; Milwaukee: 2006. Justice, moral competencies and the role of dental schools. The profession’s mandate on issues of justice; pp. 234–259. [Google Scholar]