Abstract

Objectives: To compare the effect of 40 seconds versus 2 minutes brushing on saliva and dental biofilm fluid fluoride in children ages 4–5 years over 1 hour. Design: This was a single-blind, cross-over, randomised, two-period clinical study in healthy children. Three days before the start of each treatment subjects received a thorough brushing and then refrained from all oral hygiene procedures. At treatment visits, after collecting baseline biofilm and saliva samples, staff brushed the occlusal surfaces of the subject’s posterior teeth with a pea-sized amount (0.25 g) of NaF/silica toothpaste for the randomised time. Samples were taken at 5 minutes, 15 minutes, 30 minutes and 60 minutes after brushing and analysed for fluoride using a microanalytical methodology. There was a minimum 4-day washout period between treatments. Results: Log changes from baseline biofilm fluid and saliva fluoride were statistically significant (P < 0.05) for both brushing times at all post-brushing time-points [except 60 minutes saliva where P = 0.06 (t-test)]. Statistically significantly greater ln-AUC (area under the curve) was found for biofilm fluid and salivary fluoride after brushing for 2 minutes compared with brushing for 40 seconds over the 1-hour test period. There was a statistically significantly higher concentration of fluoride in the log change from baseline saliva levels after 5, 15, 30 and 60 minutes for the 2-minute brushing time compared with 40 seconds brushing time. There was no statistically significant difference in concentration of log change from baseline fluoride levels in biofilm fluid at each individual time-point (5, 15, 30 and 60 minutes) for the 2-minute brushing time compared with the 40-second brushing time, but significant differences were observed for 15, 30 and 60 minutes in favour of 2-minute brushing time when log biofilm fluid value was analysed. Conclusion: The findings provide further evidence for the benefits of increased duration of brushing with respect to fluoride delivery.

Key words: Biofilm-fluid, fluoride, retention, saliva, toothpaste, children, brushing time

INTRODUCTION

Dental caries occurs as a result of dissolution of enamel, caused by acids produced by the dental biofilm. Topical fluoride delivered by brushing with toothpaste is accepted as effective in the prevention of caries1, mainly because it decreases the rate of enamel demineralisation and enhances the rate of enamel remineralisation2., 3.. Numerous in vitro studies have shown that the rate of caries progression and remission is directly affected by the fluoride content of the liquid phase of the biofilm overlying the lesion4., 5., 6..

In practice, a tooth surface is only vulnerable to caries if it is covered by a biofilm2. Thus biofilm fluid is the key solvent in which minerals are exchanged at the tooth surface. The level of fluoride in biofilm, more specifically in biofilm fluid, appears to be directly related to its anti-caries effect7.

Fluoride in the biofilm fluid exists in equilibrium with fluoride in the saliva8, which in turn exists in equilibrium with fluoride bound to the oral soft tissues9, which are believed to be the principal fluoride reservoir after brushing. As fluoride levels in saliva and biofilm fluid are mutually interdependent, they are both important in the prevention of caries.

These complex exchange processes and nature of saliva flow over oral surfaces10 mean that oral delivery and clearance of fluoride is extremely difficult to model11, so clinical studies are critical to understand fully the impact of brushing duration and quantity of dentifrice on the process.

There have been several studies on the kinetics of fluoride in biofilm fluid after topical application. The pioneering work of Tatevossian12 reported increased fluoride levels in pooled biofilm fluid for 2 hours, after rinsing with 20 mmol/l NaF rinse. Vogel et al.13 found a strong linear correlation between salivary and biofilm fluid fluoride after administration of a 0.2% NaF rinse. Direct comparisons have also been made of fluoride in biofilm fluid after NaF and monofluorophosphate (MFP) rinses14., 15..

Starting from the work of Aasenden et al.16, there have been many studies of the kinetics of fluoride in saliva after topical application. The studies of Duckworth8., 9., 17., 18., 19. showed that fluoride clearance is biphasic: an initial rapid loss of fluoride in the first approximately 15 minutes followed by a much slower rate of loss for the ensuing hours. The rapid clearance phase has been attributed to loss of fluoride present in free solution in the oral fluids; the slow clearance phase has been attributed to loss of fluoride bound to oral surfaces, which must first dissociate into free solution before clearance.

Children are particularly vulnerable to caries. Teeth emerging during childhood will create certain ‘stagnation sites’, especially occlusal surfaces and interproximal areas, where cariogenic biofilm will accumulate even with regular toothbrushing habits20., 21.. If the overall remineralisation–demineralisation balance at these sites tends to favour demineralisation, it is likely that dental caries will progress to the cavitation stage within a few years (i.e. during childhood)21. Additional caries risk factors for children may include low dexterity/enthusiasm for brushing compared with adults; a diet higher in frequency and quantity of fermentable carbohydrates also predisposed to caries22., 23..

Recent studies have shown the importance in adults of brushing duration, and quantity of dentifrice used, on in-situ fluoride uptake and consequent remineralisation by early enamel lesions24., 25.. This suggests that caries protection from a dentifrice is dependent on both duration of brushing and quantity of paste used. To our knowledge, only one published study exists on saliva fluoride levels as a function of quantity of dentifrice used in children26; this concluded that quantity of dentifrice is very important.

This currently reported study used methodology utilised in previously reported studies evaluating fluoride in biofilm fluid in an adult population24., 25. with a number of adaptations in order to conduct the study in a younger population. Based on a pilot study to evaluate feasibility of conducting a study of this nature in a population of children aged 4–5 years we determined that the ability of children of this age to understand the concept of ‘spitting’ or to have the physical ability to provide saliva samples was varied. Consequently, the saliva collection method for this study has been modified in order to collect saliva samples from all subjects regardless of their ability to spit by using a modified mucus trap method instead of requesting that the subjects expectorate into a container.

The quantity of paste (0.25 g) was chosen from the near-universal dental professional body recommendation that children aged 6 years and under should brush with a ‘pea-sized’ quantity of paste. The only guidance (of which we are aware) as to the actual weight of a pea-size amount of paste is a European Union Committee recommendation which states that a ‘pea-sized’ amount should be taken as 0.25 g27. DenBesten and Ko26 reported that following brushing with 0.25 g of toothpaste, fluoride levels in saliva had returned to baseline levels within 45 minutes.

The purpose of the present study was to observe the fluoride clearance curve in children following two different brushing times was measured over a 1-hour period.

The brushing times used have been chosen in the light of existing data on how long children brush versus how long professionals recommend. A recent study of children’s brushing time found that the average time spent was 39 seconds28, which is in agreement with a previous study indicating approximately 40 seconds29. A general consensus among oral health-care professionals is that individuals should spend at least 120 seconds brushing their teeth with an effective technique at least twice a day.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study design

This was a single-blind (fluoride analyst), cross-over, randomised, two-period study in healthy children aged 4–5 years (inclusive) to evaluate the effect of two different brushing times (40 seconds and 2 minutes) on biofilm fluid fluoride and salivary fluoride levels over a 1-hour period after use of an experimental sodium fluoride/silica children’s toothpaste containing 1150 ppm fluoride. The study protocol and consent form was reviewed and approved by the Indiana University Institutional Review Board and the study conformed to the guidelines laid out in the Declaration of Helsinki.

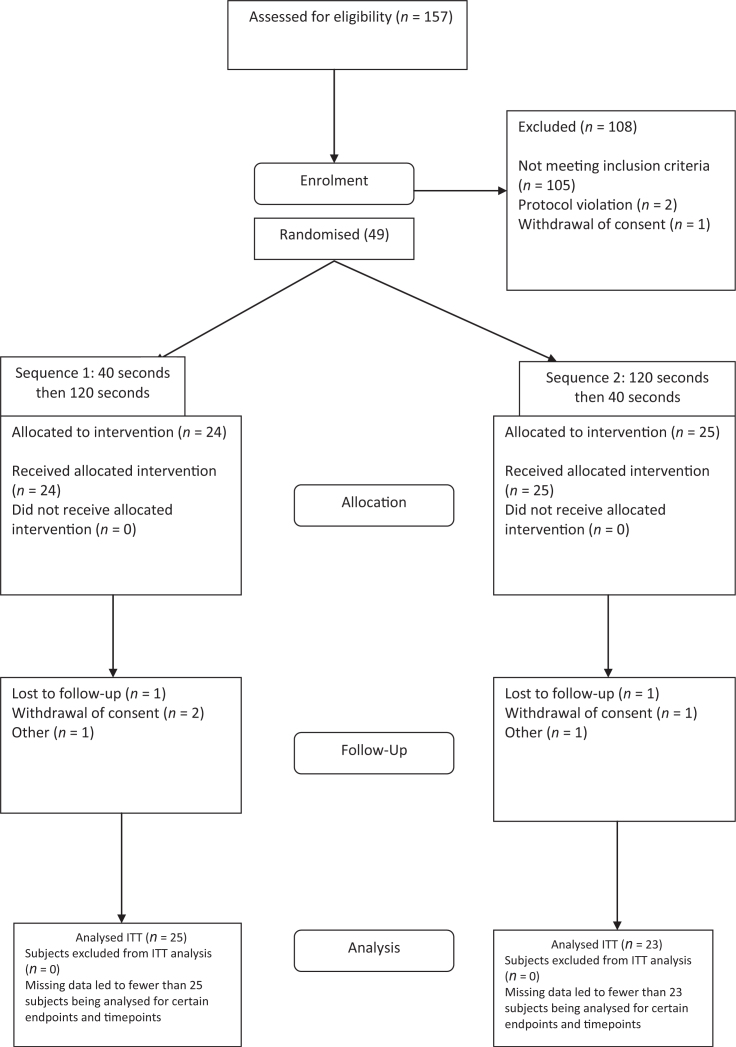

Parental/legal guardian informed consent was collected before any subject’s participation in this study – because of the age of the children no child assent was collected. A total of 157 healthy subjects between the ages of 4 and 5 years were screened from 21 October 2011 to 28 February 2012, with 49 subjects randomised to study treatment. The study completed in March 2012. The flow of the subjects through the study is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Trial profile.

Subjects were enrolled into the study if they:

-

•

Had a sufficient number of primary teeth that were fully erupted and not noticeably loose (at least one tooth per quadrant) to obtain an adequate biofilm sample

-

•

Produced at least 5 mg of biofilm at the required screening visits

-

•

Had adequate salivary flow (0.2 ml/minute using the mucus trap method) at the required screening visits

-

•

Subjects were excluded from the study if they were:

-

•

Undergoing therapy with products or drugs that in the opinion of the investigator or dental practitioner may influence salivary flow

-

•

Taking fluoride supplements or other fluoride products for health reasons except that naturally occurring in usual diet

-

•

Had been placed under the control or protection of an agency, organisation, institution or entity by the courts, the government or a government body, acting in accordance with powers conferred on them by law or regulation. This included a child cared for by foster parents or living in a care home or institution. This does not include a child who is adopted or has an appointed legal guardian.

Oral soft tissue (OST) and oral hard tissue (OHT) examinations were performed at the initial screening visit. Subjects then received a thorough brushing and flossing of all teeth using a marketed children’s toothpaste (Aquafresh® Kids toothpaste, GlaxoSmithKline Consumer Healthcare, L.P., Pittsburgh, PA, USA) and toothbrush (Aquafresh® Kids toothbrush) to remove all biofilm. Eligible subjects were instructed to refrain from all oral hygiene products and procedures for the next 3 days to allow sufficient growth of biofilm at their next visit.

The second screening visit was to assess whether subjects were likely to form sufficient amounts of biofilm during treatment visits, had sufficient salivary flow and could willingly sit for the collection processes, an OST examination was also performed at this visit by one of two trained dentists. At the end of the second screening visit subjects had their teeth flossed and thoroughly brushed with the marketed children’s toothpaste by one of three trained dental hygienists. For those that qualified to participate, the same toothpaste was provided to use at home for the duration of the study except during the 3-day no oral hygiene periods before each treatment visit.

Approximately 1 mg of biofilm was required for each sample in order to perform the analytical measurement (five samples were required in total at each visit: baseline, 5 minutes, 15 minutes, 30 minutes and 60 minutes after brushing). Therefore, at each treatment visit the subject was required to have approximately 5 mg of biofilm (following the 3-day brushing abstinence). Repeat screening and treatment visits were permitted for subjects who were unable to produce the required amount of biofilm or who were unable to attend both the brushing and subsequent biofilm collection visit within the 3-day time limit.

Subjects attended the study site 3 days before each treatment visit, where they received an OST assessment followed by having their teeth flossed and thoroughly brushed with the washout toothpaste by a trained dental hygienist. Subjects then abstained from oral hygiene until the treatment visit 3 days later.

At the treatment visits subjects received a pretreatment OST examination, a saliva sample was then collected followed by collection of an interproximal and buccal biofilm sample from the posterior teeth by a trained dental hygienist. The occlusal surfaces of the teeth were brushed by a trained dental hygienist with 0.25 g ± 0.03 g (a pea-sized amount) of the test dentifrice (an experimental sodium fluoride/silica children’s toothpaste containing 1150 ppm fluoride) for the randomized time (40 seconds or 120 seconds). Subjects then expectorated the toothpaste slurry and rinsed with 10 ml of deionised water for 10 seconds and expectorated. Only the occlusal surfaces were brushed to avoid disturbing the biofilm. Saliva samples were collected 5 ± 1 minutes, 15 ± 5 minutes, 30 ± 5 minutes and 60 ± 5 minutes after brushing. Approximately 1 mg of interproximal/buccal biofilm was collected immediately after each saliva sample. Thorough brushing, treatment brushing, plaque and saliva collection was conducted throughout the study by one of three trained hygienists for each subject. Subjects were required to remain at the site for the entire treatment phase.

At the end of each treatment period the hygienist or dentist thoroughly brushed the subject’s teeth using the commercial children’s toothpaste and study toothbrush. Subjects received a post-treatment OST examination. There was a minimum of 4 days before the next treatment period.

Randomisation procedure

Subjects were assigned randomisation numbers by a dispenser at the study site using a randomisation schedule list generated by the study sponsor. Randomisation numbers were assigned sequentially in chronological order as each subject was deemed to be fully eligible. Subjects received the corresponding two study treatments in the sequence order specified by a randomisation schedule using a Williams Latin Square design.

Saliva collection procedure (mucus trap method)

A mucus trap is a hand-powered suction device with an attached collection vial for collecting mucus or saliva, and a suction catheter that is often used with tracheotomy tubes. In this study, the suction source was the saliva ejector and a saliva ejector tip was inserted into the end of the catheter tube. The child was instructed to swallow all saliva at the beginning of the 5-minute collection and was then instructed to open their mouth while the saliva ejector tip was moved around in the child’s mouth to collect the saliva. The child was then instructed to close their mouth and the procedure was repeated periodically (every 10–20 seconds) for the 5-minute collection period.

Biofilm collection procedure

Immediately before dental biofilm collection, the subject was instructed to swallow all remaining saliva and then keep their mouth open. Interproximal and buccal biofilm samples were collected by one of the trained dental hygienists. Approximately 1 mg of dental biofilm was collected from the interproximal and buccal surfaces of the posterior teeth of all four quadrants. Biofilm samples were collected using a standardised approach. Using a stainless steel periodontal scaler (S. McCall 17/18 or IU 17/18, Hu-Friedy Mfg. Co, Inc., Chicago, IL, USA), pooled biofilm samples were collected from each interproximal area (buccal aspect) and buccal area starting from the upper right quadrant to the upper left, lower left and ending in the lower right quadrants. The pooled biofilm sample was then transferred to a preweighed plastic strip.

Biofilm-fluid fluoride analysis

The microanalytical method of Vogel et al.13 was used to analyse biofilm fluid samples for fluoride content:

-

•

Samples were placed, under mineral oil, on the surface of a specially constructed inverted F electrode. The mineral oil was used to prevent evaporation

-

•

Total ionic strength-adjusting solution (TISAB III) was added to the samples in a ratio of 9:1

-

•

The tip of a microreference electrode was placed in contact with the sample to complete the circuit.

Triplicate analyses was performed on each pooled biofilm fluid sample. Biofilm fluid fluoride was expressed as μg F/g, which was calculated by comparison with a standard fluoride curve constructed the same day of the analysis.

Saliva sample analysis

The concentration of fluoride was measured in all saliva samples. Samples were centrifuged for 10 minutes at 10,000 rpm (4,000 g gravity) at 7°C and the supernatant was stored at 4°C for immediate analysis or at −20°C for later fluoride analysis. Analysis of saliva was conducted using a modification of the hexamethyl-disiloxane (HMDS) microdiffusion method of Taves30 as modified by Martinez–Mier, et al.31. One millilitre of centrifuged saliva sample was pipetted into plastic Petri dishes (Falcon 15-cm plastic Petri dishes), adding enough deionised water to bring final volume in each Petri dish to 3.0 ml. A 0.05 m sodium hydroxide analytical reagent (NaOH) 50 μl trap solution was placed in five drops on the Petri dish lid and after the addition of 1 ml of sulphuric acid (H2SO4) saturated with HMDS through a small hole in the lid of the Petri dish; each dish was immediately tightly sealed with petroleum jelly. During overnight diffusion, fluoride was released by acid hydrolysis and trapped in the NaOH. The trap was recovered and buffered to pH 5.2 with 25 μl acetic acid (CH3COOH). The recovered solution was adjusted to a final volume of 100 ml with total ionic strength buffer (TISAB II). Fluoride was measured using a fluoride combination electrode (Orion Specific Ion Combination Fluoride Electrode, 96-909-00, Precision Instruments, Sarasota, FL, USA) and pH/ion meter (Orion EA940). The fluoride content (μg F) of the samples was calculated from a standard curve constructed from fluoride standards and microdiffused at the same time as the samples.

The amount of total fluoride in the samples was calculated based on the amount of fluoride divided by the volume of the sample and expressed as μg F/ml of sample.

The amount of fluoride delivered by the dentifrice to the saliva over the 1-hour post brushing period (i.e. the area under the salivary F clearance curve) was calculated via trapezoidal rule.

Criteria for evaluation of efficacy

For the primary objective, the criterion of success was whether there was a statistically significant increase in the biofilm fluid area under the curve (AUC) between brushing for 120 seconds compared with 40 seconds.

Safety

The safety profile of the experimental sodium fluoride children’s toothpaste was assessed with respect to the incidence of treatment–emergent adverse events (AEs) and OST abnormalities.

Calculation of sample size

The sample size was calculated for the primary efficacy parameter, AUC, for fluoride concentration in biofilm fluid in the 1 hour following a single use. With 50 completed subjects, it was calculated that there would be an estimated 80% power at the 0.05 level of significance, using two-sided testing, to detect a mean treatment difference on the natural logarithm scale of 0.285 for AUC (with a standard deviation of the difference estimated to be 0.705). This translated to a standardized effect size of 0.404. The estimate of standard deviation was based on a two similar, previous studies conducted on adults over a 4-hour period using a larger amount of toothpaste24., 32..

Statistical methods

The primary efficacy variable was the biofilm fluid AUC, the area under the biofilm fluid fluoride clearance curve, measured using the trapezoidal method. Subjects without fluoride data for at least three time-points after brushing, including the 1-hour time-point, did not have a sufficient number of data points for an accurate estimate of AUC to be calculated. In this case the AUC value was set to missing. Where the baseline value was missing, it was set as zero for calculation of AUC. Where the 1-hour value was missing, the AUC was also set to missing as it is not possible to calculate AUC accurately without this information. The efficacy analysis required natural logarithm transformation of AUC values before analysis because of failure of the assumptions of normality of the model residuals. Statistical analysis for natural logarithm-transformed AUC was performed with statistical analysis system (SAS) software (SAS Cary, NC, USA) using a linear model. An analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) model included subject (as a random effect), treatment and study period as factor and two baseline terms as covariates; (1) the subject-level baseline biofilm fluid concentration calculated as the mean baseline across both periods within a subject, and (2) the period-level baseline biofilm fluid concentration minus the subject-level baseline biofilm fluid concentration. Mean differences between the duration of brushing are presented with 95% confidence intervals. All tests were two-sided and performed at the 5% significance level.

The secondary efficacy variables were:

-

•

Biofilm fluid fluoride concentration at each post-brushing time-point (5, 15, 30 and 60 minutes)

-

•

Saliva fluoride AUC

-

•

Change in fluoride concentration in biofilm fluid from baseline at each time-point (5, 15, 30 and 60 minutes)

-

•

Change in fluoride concentration in saliva from baseline at each time-point (5, 15, 30 and 60 minutes).

The variables 1 and 2 were analysed in the same way as primary efficacy but with biofilm fluid and saliva fluid at baseline as the covariates for the biofilm and saliva endpoints, respectively. Natural logarithm transformations were required.

The variables 3 and 4 were analysed in the same way as primary efficacy but with biofilm fluid and saliva fluid at baseline as the covariates for the biofilm and saliva endpoints, respectively. Within-treatment change from baseline were assessed comparing the adjusted mean value observed from the ANCOVA model versus zero using a t-test. Natural logarithm transformations were required.

During the blinded data review, it was noted that there were some instances where the baseline levels of fluoride were not obtained owing to an inability to extract fluid from the total biofilm. This sensitivity analysis analysed the biofilm fluid fluoride in AUC without baseline levels as a covariate. The model terms included subjects (as a random effect), treatment and study periods in the analysis of variance (anova) model.

As the primary endpoint was predefined, there has been no adjustment for multiplicity.

RESULTS

It was planned to randomise 60 subjects to have 50 subjects complete both treatment periods of the study. One hundred fifty-seven subjects were screened, however, owing to entry criteria challenges (predominantly the inability to provide sufficient biofilm for all assessments), 49 subjects were randomised. A total of 42 subjects completed the study. A total of 48 subjects were included in an intent to treat (ITT) population and 47 subjects were included in the per protocol (PP) population. Efficacy analyses were based on the ITT population; PP population analyses were not performed. Seven of the randomised subjects did not complete the study, three were because of withdrawal of consent, two could not grow sufficient biofilm and two were lost to follow up.

Demographics

The baseline demographics for the study population are summarised in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographics of intent to treat study population

| Number of subjects | Age (years) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male | Female | Overall | Mean | Range | |

| Overall intent to treat | 25 | 23 | 48 | 4.4 | 4–5 |

Efficacy results

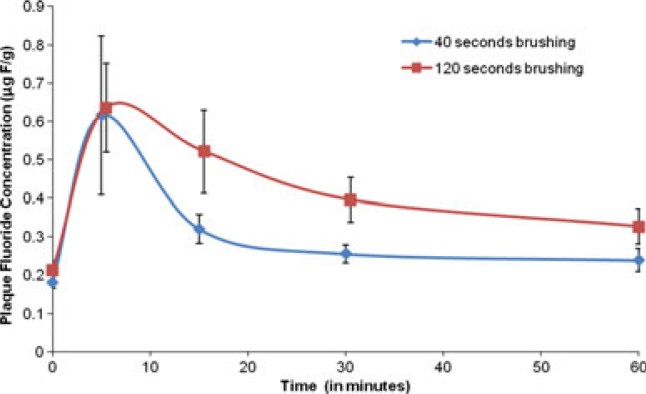

The mean (SE) fluoride concentrations in biofilm fluid at each time-point are shown in Figure 2. The values observed for 40-second and 2-minute brushing times, respectively, in μg F/g were: baseline 0.182 (0.016), 0.212 (0.025); 5 minutes 0.616 (0.206), 0.635 (0.116); 15 minutes 0.321 (0.037), 0.521 (0.108); 30 minutes 0.256 (0.023), 0.395 (0.058) and 60 minutes 0.239 (0.030), 0.327 (0.046).

Figure 2.

Summary of mean biofilm fluid fluoride concentration over time.

The mean (SE) fluoride concentrations in saliva at each time-point are shown in Figure 3. The values observed for 40-second and 2-minute brushing times, respectively, in μg F/g were: baseline 0.032 (0.004), 0.037 (0.006); 5 minutes 0.510 (0.050), 0.797 (0.102); 15 minutes 0.155 (0.014), 0.182 (0.017); 30 minutes 0.072 (0.006), 0.107 (0.013) and 60 minutes 0.039 (0.006), 0.049 (0.006).

Figure 3.

Summary of mean saliva fluoride concentration over time. ITT, intent to treat.

A statistically significant difference based on log-transformed AUC at 1 hour for both biofilm fluid fluoride (P = 0.0279) and saliva fluoride (P = 0.0033) was observed in favour of a 120-second brushing time compared with a 40-second brushing time (Tables 2 and 3).

Table 2.

Log biofilm fluid fluoride concentration between-treatment (40 seconds vs. 120 seconds brushing time) comparison

| Treatment | Parameter | Log biofilm fluid fluoride concentration of change from baseline (μg F/g) | ln AUC* | AUC† | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5 minutes | 15 minutes | 30 minutes | 60 minutes | ||||

| 40 seconds versus 120 seconds | Difference (mean) | −0.0976 | −0.1524 | −0.1991 | −0.1704 | −0.23 | 0.79 |

| 95% CI (lower, upper) | −0.42, 0.23 | −0.39, 0.08 | −0.45, 0.05 | −0.43, 0.09 | −0.44, −0.03 | 0.65, 0.97 | |

| P-value | 0.5460 | 0.1985 | 0.1197 | 0.1852 | 0.0279 | ||

Difference (Mean).

Ratio of geometric mean.

P-value <0.05 is significant and bold.

Table 3.

Log biofilm fluid fluoride concentration within-treatment change from baseline

| Treatment | Parameter | Log biofilm fluid fluoride concentration of change from baseline (μg F/g) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5 minutes | 15 minutes | 30 minutes | 60 minutes | ||

| 40 seconds | Change from baseline (adjusted mean*) | 0.8324 | 0.5466 | 0.3323 | 0.2143 |

| Standard error* | 0.1201 | 0.0930 | 0.0899 | 0.0855 | |

| P-value | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | 0.0005 | 0.0148 | |

| 120 seconds | Change from baseline (Adjusted Mean*) | 0.9299 | 0.6990 | 0.5314 | 0.3847 |

| Standard error* | 0.1238 | 0.0945 | 0.0901 | 0.0928 | |

| P-value | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | 0.0001 | |

Based on log transformed data.

P-values <0.05 are significant and bold.

Both the treatment groups showed a statistically significant change from baseline at each post-brushing time-point in terms of log biofilm fluid fluoride concentration and log saliva fluoride concentration except for 1 hour in the 40-second brushing time experimental group for saliva (P = 0.0630) (Tables 3 and 4).

Table 4.

Log biofilm fluid fluoride concentration between-treatment (40 seconds vs. 120 seconds brushing time) comparison (sensitivity analysis for AUC)

| Treatment | Parameter | Log biofilm fluid fluoride concentration (μg F/g) | ln AUC* | AUC† | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5 minutes | 15 minutes | 30 minutes | 60 minutes | ||||

| 40 seconds versus 120 seconds | Difference (mean) | −0.1400 | −0.2206 | −0.2852 | −0.2443 | −0.29 | 0.75 |

| 95% CI (lower, upper) | −0.45, 0.17 | −0.43, −0.01 | −0.48, −0.09 | −0.48, −0.01 | −0.52, −0.07 | 0.59, 0.93 | |

| P-value | 0.3619 | 0.0391 | 0.0063 | 0.0411 | 0.0123 | ||

Difference (mean).

Ratio of geometric mean.

P-values <0.05 are significant and bold.

No statistically significant difference in log change from baseline biofilm fluid fluoride concentration was observed at any individual post-brushing time-point comparing a 40-second brushing with a 120-second brushing (Table 2), but significant differences were observed for 15, 30 and 60 minutes in favour of the 120-second brushing time when the log biofilm fluid value was analysed rather than the change from baseline value (Table 5).

Table 5.

Log saliva fluoride concentration between-treatment (40 seconds vs. 120 seconds brushing time) comparison

| Treatment | Parameter | Log saliva fluoride concentration of change from baseline (μg F/g) | ln AUC* | AUC† | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5 minutes | 15 minutes | 30 minutes | 60 minutes | ||||

| 40 seconds versus 120 seconds | Difference (mean) | −0.4882 | −0.3073 | −0.4266 | −0.3195 | −0.27 | 0.76 |

| 95% CI (lower, upper) | −0.77, −0.20 | −0.58, −0.03 | −0.69, −0.16 | −0.64, −0.00 | −0.44, −0.10 | 0.64, 0.91 | |

| P-value | 0.0012 | 0.0299 | 0.0023 | 0.0496 | 0.0033 | ||

Difference (mean).

Ratio of geometric mean.

P-values <0.05 are significant and bold.

Statistically significant differences were observed for log change from baseline in saliva fluoride concentration at each individual post-brushing time-point comparing 40 seconds of brushing with 120 seconds of brushing (Table 6). The sensitivity analysis for log biofilm fluoride AUC gave consistent results (P = 0.0123) in favour of the 120-second brushing time (Table 5).

Table 6.

Log saliva fluoride concentration within-treatment change from baseline

| Treatment | Parameter | Log saliva fluid fluoride concentration of change from baseline (μg F/g) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5 minutes | 15 minutes | 30 minutes | 60 minutes | ||

| 40 seconds | Change from baseline (adjusted mean*) | 2.8527 | 1.6885 | 0.9465 | 0.2244 |

| Standard error* | 0.1241 | 0.1058 | 0.1041 | 0.1191 | |

| P-value | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | 0.0630 | |

| 120 seconds | Change from baseline (adjusted mean*) | 3.3408 | 1.9958 | 1.3731 | 0.5439 |

| Standard error* | 0.1245 | 0.1062 | 0.1045 | 0.1195 | |

| P-value | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | |

Based on log transformed data.

P-values <0.05 are significant and bold.

Safety results

A total of 49 subjects were included in the safety population. A total of nine subjects reported 10 treatment-emergent AEs. There were no oral AEs reported in this study. None of the AEs were treatment related and all were mild in intensity; no serious AEs were reported.

DISCUSSION

This single-blind (fluoride analyst), crossover, randomised, two-period study in healthy children aged 4–5 years (inclusive) evaluated the effect of two different brushing times (40 seconds and 2 minutes) on biofilm fluid fluoride and salivary fluoride levels over a 1 hour period in children aged 4–5 years using 0.25 g of toothpaste.

The results of the current study are in agreement with previous studies that have reported statistically significant differences on the AUC for both biofilm fluid fluoride and saliva fluoride24., 33.. Also in agreement with those previous reports is the fact that both treatment groups in the current study demonstrated a statistically significant (marginally significant in one case) change from baseline within treatment at each post-brushing time-point.

Our results provide evidence in support of the importance of the duration of brushing reported for adults24., 25.. Careful analysis of the fluoride values observed in this study shows that fluoride clearance is biphasic with an initial rapid loss of fluoride, followed by a much slower rate of loss for the ensuing 60 minutes, as previously reported by Duckworth and colleagues8., 9., 17., 18., 19..

CONCLUSION

The results of the present clinical study provide further evidence to support the fluoride delivery benefits of 2 minutes brushing in children.

Conflict of interest

Authors Newby, Fleming, North and Bosma are employed by GlaxoSmithKline Consumer Healthcare. Authors Martinez-Mier, Zero and Kelly were funded by GlaxoSmithKline Consumer Healthcare to conduct this study.

REFERENCES

- 1.Marinho VCC, Higgins JPT, Logan S, et al. Fluoride toothpastes for preventing dental caries in children and adolescents. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009;1:CD002278. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD002278. (Systematic Review) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.ten Cate JM. Current concepts on the theories of the mechanism of action of fluoride. Acta Odontol Scand. 1999;57:325–329. doi: 10.1080/000163599428562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Featherstone JDB. Prevention and reversal of dental caries: role of low level fluoride. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 1999;27:31–40. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0528.1999.tb01989.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.ten Cate JM, Duijsters PPE. Influence of fluoride in solution on tooth demineralization. II. Microradiographic data. Caries Res. 1983;17:513–519. doi: 10.1159/000260711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Moreno EC, Margolis HC, Murphy BJ. Effect of low levels of fluoride in solution on enamel demineralization in vitro. J Dent Res. 1986;65:23–29. doi: 10.1177/00220345860650010301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wefel JS, Harless JD. The effect of several topical fluoride agents on artificial lesion formation. J Dent Res. 1982;61:1169–1171. doi: 10.1177/00220345820610101201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ekstrand J, Oliveby A. Fluoride in the oral environment. Acta Odontol Scand. 1999;57:330–333. doi: 10.1080/000163599428571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Duckworth RM, Morgan SM, Murray AM. Fluoride in saliva and plaque following use of fluoride-containing mouthwashes. J Dent Res. 1987;668:1730–1734. doi: 10.1177/00220345870660120701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Duckworth RM, Morgan SM. Oral retention of fluoride after use of fluoride dentifrices. Caries Res. 1991;25:123–129. doi: 10.1159/000261354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dawes C, Watanabe S, Biglow Lecomte P, et al. Estimation of the velocity of the salivary film at some different locations in the mouth. J Dent Re. 1989;68:1479–1482. doi: 10.1177/00220345890680110201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Spadaro AC, Leitao DPS, Polizello AC, et al. Construction and evaluation of an inexpensive device that stimulates oral clearance. Braz Dent J. 2001;12:183–186. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tatevossian A. Distribution and kinetics of fluoride ions in the free aqueous and residual phases of human dental plaque. Arch Oral Biol. 1978;23:893–898. doi: 10.1016/0003-9969(78)90293-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vogel GL, Carey CM, Ekstrand J. Distribution of fluoride in saliva and plaque fluid after a 0.048 mol/L NaF rinse. J Dent Res. 1992;71:1553–1557. doi: 10.1177/00220345920710090201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ekstrand J. Fluoride in plaque fluid and saliva after NaF or MFP rinses. Eur J Oral Sci. 1997;105:478–484. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0722.1997.tb00234.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vogel GL, Mao Y, Chow LC, et al. Fluoride in plaque fluid, plaque, and saliva measured for 2 hours after a sodium fluoride monofluorophosphate rinse. Caries Res. 2000;34:404–411. doi: 10.1159/000016615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Aasenden R, Brudevold F, Richardson B. Clearance of fluoride from the mouth after topical fluoride treatment or the use of a fluoride mouthrinse. Arch Oral Biol. 1968;13:625–636. doi: 10.1016/0003-9969(68)90141-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Duckworth RM, Morgan SM, Burchell CK. Fluoride in plaque following use of dentifrices containing NaMFP. J Dent Res. 1989;68:130–133. doi: 10.1177/00220345890680020601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Duckworth RM, Knoop DTM, Stephen KW. Effect of mouthrinsing after toothbrushing with a fluoride dentifrice on human salivary fluoride levels. Caries Res. 1991;25:287–291. doi: 10.1159/000261378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Duckworth RM, Morgan SN, Gilbert RJ. Oral fluoride measurements for estimation of the anti-caries efficacy of fluoride treatments. J Dent Res. 1992;71:836–840. doi: 10.1177/002203459207100S09. Spec Iss. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Robinson C. Mass transfer of therapeutics through natural human plaque biofilms: a model for therapeutic delivery to pathological bacterial biofilms. Arch Oral Biol. 2011;56:829–836. doi: 10.1016/j.archoralbio.2011.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Carvalho JC, Ekstrand KR, Thylstrup A. Dental plaque and caries on occlusal surfaces of first permanent molars in relation to stage of eruption. J Dent Res. 1989;68:773–779. doi: 10.1177/00220345890680050401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gustafsson BE, Quensel CE, Lanke LS, et al. The Vipeholm dental caries study; the effect of different levels of carbohydrate intake on caries activity in 436 individuals observed for five years. Acta Odontol Scand. 1954;11:232–264. doi: 10.3109/00016355308993925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bradshaw DJ, Lynch RJM. Diet and the microbial aetiology of dental caries: new paradigms. Int Dent J. 2013;63(Suppl 2):64–72. doi: 10.1111/idj.12072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zero DT, Creeth JE, Bosma ML, et al. The Effect of brushing time and dentifrice quantity on fluoride delivery in vivo and enamel surface microhardness in situ. Caries Res. 2010;44:90–100. doi: 10.1159/000284399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Creeth J, Zero D, Mau M, et al. The effect of dentifrice quantity and toothbrushing behaviour on oral delivery and retention of fluoride in vivo. Int Dent J. 2013;63(Suppl 2):14–24. doi: 10.1111/idj.12075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.DenBesten P, Ko HS. Fluoride levels in whole saliva of preschool children after brushing with 0.25 g (pea-sized) as compared to 1.0 g (full-brush) of a fluoride dentifrice. Pediatr Dent. 1996;18:277–280. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.SCCNFP 2003. Opinion of the scientific committee on cosmetic products and non-food products intended for consumers concerning the safety of fluorine compounds in oral hygiene products for children under the age of 6 years. http://ec.europa.eu/food/fs/sc/sccp/out219_en.pdf

- 28.Newby EE, Ashburner SA, Bosma ML. A study to evaluate the normal toothbrushing habits of children. J Dent Res. 2009;88:2009. (poster 2001) [Google Scholar]

- 29.MacGregor IDM, Rugg-Gunn AJ. Survey of toothbrushing duration in 85 uninstructed English schoolchildren. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 1979;7:297–298. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0528.1979.tb01235.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Taves DR. Separation of fluoride by rapid diffusion using hexamethyldisiloxane. Talanta. 1968;15:969–974. doi: 10.1016/0039-9140(68)80097-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Martínez-Mier EA, Cury JA, Heilman JR, et al. Development of gold standard ion-selective electrode-based methods for fluoride analysis. Caries Res. 2011;45:3–12. doi: 10.1159/000321657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Creeth JE, Kelly SA, Mau M et al. Effect of Dentifrice Usage Regimen on Oral Retention of Fluoride. PER/IADR Congress, Helsinki, September 12–15, 2012. Abstract 26

- 33.Newby EE, Bosma ML, Yadav M, et al. Evaluation of plaque fluid fluoride retention after dentifrice application. Caries Res. 2009;43:179–244. Abstract 82. [Google Scholar]