Abstract

Patient safety is a relatively new discipline aimed at improving the quality of care, minimising treatment errors and improving the safety of patients. Although health professions always have a specific concern for patient safety, few practitioners have a clear understanding of the broad context and not all health-care providers practice it. This might well be because of limited availability of information and materials as well as a lack of national or international laws and regulations. Thus, through member National Dental Associations (NDAs) of FDI (World Dental Federation), the present study aimed at analysing the attitudes of dental practitioners to the issues of patient safety and risk management, and the availability of materials and laws and regulations. Determination of their specific needs and demands in these fields was also attempted. For this purpose, an online questionnaire was developed for the member NDAs to respond. Questions mainly focused on the awareness regarding patient safety, availability of materials and regulations and the particular topics for which dentists needed further knowledge and information. A total of 40 responses were received. While some countries lack any documents, patient safety documents and materials were available in some countries but they were mostly limited to infection control and radiation protection and did not address other important aspects of patient safety. The NDAs clearly demanded more information. A significant number of countries also lacked national laws and/or regulations regarding patient safety. Although dentistry always has a genuine concern for patient safety, the findings of the survey suggest that yet more efforts are needed to improve the knowledge, understanding and awareness of dental practitioners regarding its broad context and the relatively ‘new’ patient safety culture. NDAs, dental educators, national, regional and international dental organisations and health authorities all can play significant roles to achieve these goals.

Key words: Patient safety, needs/demands, dental education, laws, awareness

INTRODUCTION

Greater emphasis is placed on patient safety each day1 and, as a result, patient safety and risk management is becoming crucial for all health professions1., 2., 3., 4., 5., 6., 7., 8..

Despite the fact that patient safety generates knowledge by itself (accidents and complications associated with the use of materials, general procedures and clinical facilities), this discipline can be defined as a cross-sectional area that benefits from the well-established knowledge in other areas. Most of this shared knowledge refers to the complications inherent in the practice of the different areas of health disciplines. However, patient safety is multifactorial and very complex, includes many key elements and has various facets and cannot be simply defined as provision of safe health care or protection of patients from harm by the health-care providers. Patient and practitioner are naturally involved; however, there are economic, fiscal, social, cultural and organisational aspects9.

Health professionals are generally expected to have greater concern for patient safety and become more familiar with the multifactorial nature of patient safety, the many determinants and the integral components of provision of safe and competent health care (e.g. medication safety, procedural and surgical skills, effective teamwork, risk management, accurate and timely communication, work environment and organisation, implementation of new technology, redesigning of clinics and outpatient settings, safety education, and the impact of systems on the quality and safety of health care, etc.1., 3., 5., 7., 8., 9., 10., 11.). In 2002, World Health Organisation (WHO) member states agreed on a World Health Assembly resolution on patient safety because they saw the need to reduce the harm and suffering of patients and their families and recognised the compelling evidence of the economic benefits of improving patient safety1.

There are significant economic and human costs associated with adverse events1. Thus, in 1999, the Institute of Medicine report, ‘To err is human: Building a safer health system’, estimated that between 44,000 and 98,000 people die each year from medical errors in hospitals alone, thus making medical errors the eighth leading cause of death in the USA. The Institute of Medicine also estimated that preventable errors cost that nation about US$17 billion annually in direct and indirect costs. Despite this, patient safety is one of three domains of quality concerns2. As a result, many attempts have been made to improve the knowledge and understanding of health professionals regarding the essential elements of patient safety1., 2., 7., 8., 12..

Dentistry has always had a genuine concern and interest for issues related to patients and delivery of safe and quality care in daily dental practice. However, like other health professions, more attention is given to patient- and safety-related issues3., 4., 5., 8., 10., 12.. Further, a new professional understanding of patient safety, risk management and treating errors is emerging. Instead of hiding them, this new understanding accepts and promotes errors as a source of learning and subsequently an increasing number of publications on dental errors are becoming available3., 4., 5., 6., 7., 12.. As an example, Mendonça et al. consider dental prescribing errors as a potential area for improvement in the medication management process and patient safety. Improving the quality of dental prescriptions is suggested to reduce the risks for medication errors and to promote the rational use of pharmacotherapy, and patient safety3. In a population-based study, tooth extraction was shown to be associated with a low but significant risk of postoperative sepsis, especially in the elderly and patients with underlying diseases13. Further, owing to the danger of trans-infection of blood-borne diseases, dental practitioners are recommended to assess the risks of cross-infection after dental extraction14. In an analysis concerning the radiographical errors of undergraduate students, it was observed that 1,089 radiographs (64.06%) were acceptable, and 611 radiographs (35.94%) were unacceptable. It was suggested that determination of the distribution of anatomical region and error types could help to eliminate these errors and radiographic retakes4. Such reporting and analysis of errors can significantly help in the identification of the main contributing factors. According to all these studies, understanding the factors that lead to errors is essential for the consideration of changes that will prevent errors1., 3., 4., 7., 12., 13., 14.. It also needs to be considered that single events or errors most often result from the convergence of multiple contributing factors and preventing errors apparently requires a systems approach in order to modify the conditions that contribute to these errors2.

It is clear that, like other health professionals, dental practitioners are also expected to have an increased awareness, knowledge and concern for patient safety and risk management, and to practice patient safety in daily dental practice. However, according to the WHO: ‘Although, patient safety is becoming more widely recognised in health-care facilities worldwide, many health-care professionals still do not adequately practice it. Furthermore, it is not widely taught to students of health care’1. Thus, based on these facts, the aim of the present study was to evaluate the attitude of dental practitioners and their needs and demands, available laws/regulations and sources of information in the field of patient safety and risk management.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

A questionnaire was developed by the FDI Dental Practice Committee (DPC) to evaluate the attitudes of FDI member National Dental Associations (NDAs) regarding patient safety and risk management in daily dental practice. The questionnaire basically had an introduction section describing the background for and aims of this questionnaire and survey.

Risk management strategies have a central role to play in reducing failures, improving health outcomes, ensuring a high quality of clinical care and, most importantly, enshrining patient safety into daily clinical practice. As risk management is multifactorial and multiprofessional in nature, it is essential that organised dentistry and individual dental professionals acknowledge their responsibility to integrate risk management strategies and practice into oral health-care systems and collaborative dental practice. The following questionnaire was developed by the FDI Dental Practice Committee (DPC) in order to determine the specific needs, perceptions and attitudes of our member NDAs in the emerging field of patient safety and risk management and assist DPC to respond, with a particular focus on the need for an FDI ‘Patient Safety Manual For Dental Practice

This introduction was followed by nine questions aiming to analyse how NDAs generally considered and interpreted the issue of patient safety, with emphasis placed on patient safety issues within the health arena in recent years, the specific needs and demands of dental practitioners regarding patient safety and risk management, and availability of national documents, resources, laws or regulations where patient safety and risk management in dental practice was concerned. Questions were also available to identify the role and mission of FDI in developing informative documents in the field of patient safety and risk management. Figure 1 demonstrates the layout of the questionnaire. The NDAs were informed about the questionnaire and how they could access and fill it out electronically. The questionnaire was left for a month and the responses were then analysed by the DPC members who were actively involved in this project.

Figure 1.

Questionnaire on patient safety and risk management developed by the FDIDental Practice Committee (DPC).

RESULTS

A total of 40 responses were received. The responding NDAs were from Albania, Australia, Belgium, Botswana, Burkina Faso, Canada, Croatia, Czech Republic, Cyprus, Denmark, France, Fiji, Ghana, Greece, Haiti, Hong Kong, Hungary, Ireland, Japan, Kyrgyz Republic, Mali, Mauritius, Myanmar, the Netherlands, Nigeria, Portugal, Romania, Senegal, Sri Lanka, Sweden, Switzerland, Thailand, Turkey, Uganda, USA and Zimbabwe. More than one response was received from some countries as they had two NDAs.

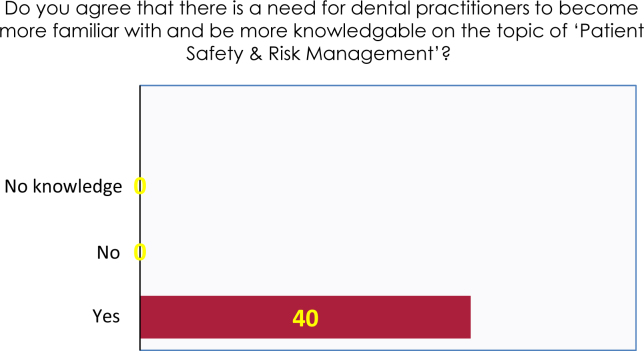

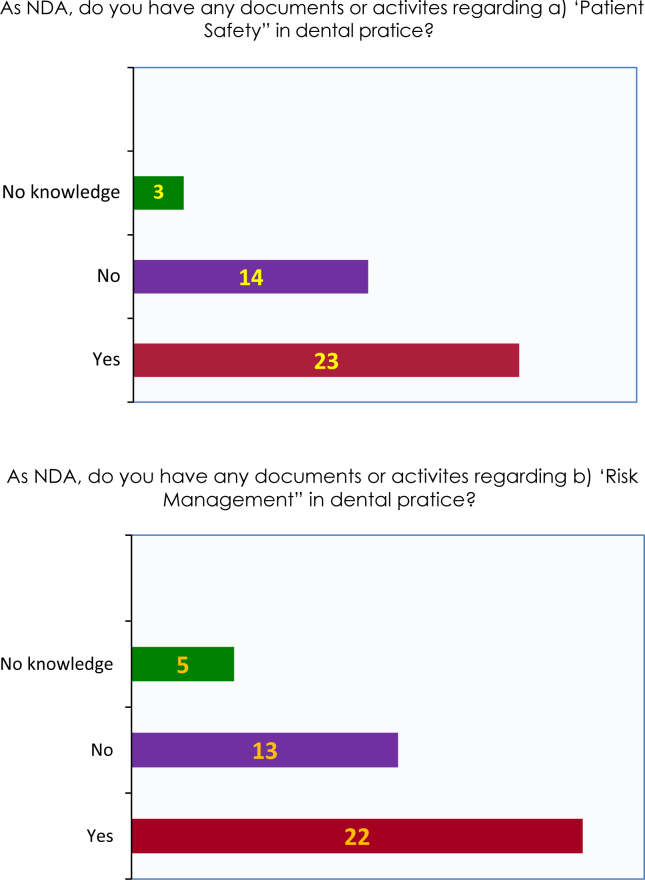

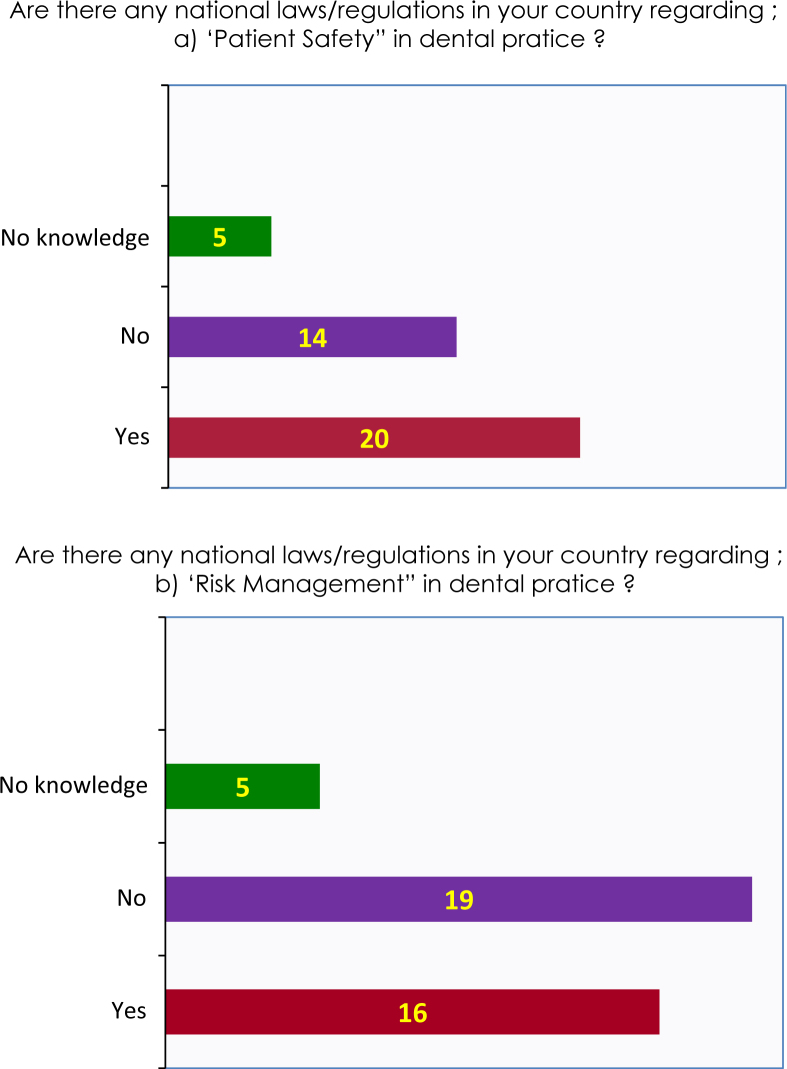

The majority of the participating NDAs agreed that more emphasis was placed on the issue of patient safety and risk management each day (n = 38) and that dental professionals needed more information and awareness in this field (n = 40) (Figure 2). As far as the availability of documents regarding patient safety and risk management was concerned, it appeared that more than one-third of the participating NDAs had no such documents or activities (Figure 3). Detailed analysis showed that the available documents were mostly concentrating on two issues: infection control and radiation protection. Only a few countries had best practice modules and annual inspections of dental practices or other important facets of patient safety. While 20 of the NDAs had national laws/regulations in the field of patient safety, 14 lacked such regulations, while four responded as having no knowledge (Figure 4).

Figure 2.

The need for more knowledge and familiarity regarding patient safety & risk management.

Figure 3.

The availability of materials and activities regarding patient safety and risk management in the participating countries.

Figure 4.

Availability of national laws/regulations regarding patient safety and risk management in the participating countries.

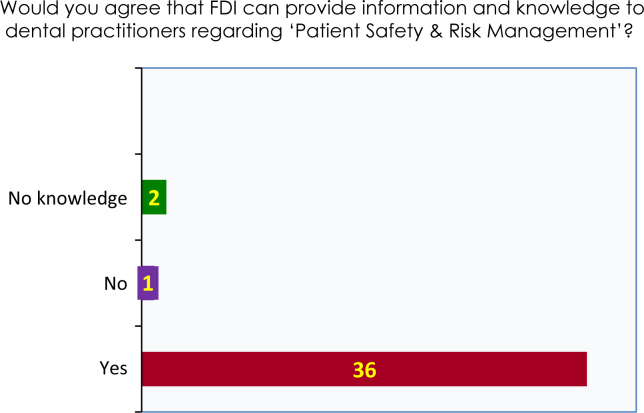

Of the 40 NDAs that responded to the questionnaire, 36 believed that the FDI could develop materials regarding patient safety and risk management (Figure 5) and most (n = 36) were in favour of an FDI patient safety manual for dentistry. The particular topics suggested to be included in the manual were also analysed and Table 1 shows the list of these topics. The participating NDAs also identified other areas where individual practitioners needed information and education about the patient; among these topics were universal laws/regulations regarding patient safety, patient privacy and confidentiality, ergonomics and clinical design, safety of dental materials, evidence regarding patient safety promotion and dental records.

Figure 5.

Perceived role of FDI in the field of patient safety and risk management.

Table 1.

The topics which NDAS demanded for information and knowledge regarding patient safety and risk management

| Definition of patient safety and general information | 32 |

| Why patient safety is important | 33 |

| Risk management | 32 |

| Infection control | 33 |

| Team work | 28 |

| Learning from errors | 25 |

| Ethical aspects of patient safety | 31 |

| Legal aspects of patient safety | 29 |

| Drugs and patient safety | 28 |

| Quality care and quality assurance | 31 |

| Essential elements of patient safety for ambulatory care | 30 |

DISCUSSION

The number of publications regarding patient safety and risk management in dentistry is increasing each day. Different aspects of patient safety (e.g. clinical, legal, ethical and professional) are being analysed3., 4., 6., 7., 8., 11., 12., 15.. Root cause analysis of errors and analysis of the circumstances that may have significant consequences for patient safety and economic loss are particular areas of interest3., 4., 11., 12.. Rogers and Malone16 highlighted that it is important for dentists to recognise the symptoms and the effects of stress on their physical, psychological and professional wellbeing both for themselves and for that of their patients. Of the working Dutch dentists, 21% had a certain risk, 13% had high overall levels of burnout and 2.5% were highly burned out15. Peer support was suggested to be important for helping dentists to cope16. In contrast, Soliman5 lists attempting procedures beyond skill level as an important factor for clinical failure. The technical skills of the dental practitioners performing root canal treatments was shown to require improvement and the need for consideration and explanation to the patient of all possible risks and complications before treatment was highlighted11.

In a population-based study, tooth extraction is shown to be associated with a low but significant risk of postoperative sepsis, especially in the elderly and patients with underlying diseases13. Further, the danger of transfection of blood-borne diseases is evident and dental practitioners need to assess the risks of cross-infection after dental extraction14. Based on the analysis of the medication errors, Mendoca et al.3 suggested that a pharmacist should be available for dispensing medication at all units and that dentists be trained continuously so that medication orders may become more legible and complete. In a study where analysis of events that led to wrong tooth extraction, errors during treatment and poor communication among clinicians led to this extraction. This can be avoided by greater caution on the part of the extracting clinician when following the treatment plan. Guidelines toward this end are recommended17.

Despite the availability of such information and materials, patient safety is still a relatively new discipline and not all health professionals have the necessary information and knowledge in this field1. Dentistry and the dental practitioners are not an exception and the survey results clearly show a significant need and demand of NDAs regarding patient safety and risk management3., 4., 7., 8., 9., 10., 11., 12.. The attitude of dental schools is clearly an important factor at this point. However, in addition to the dental schools, NDAs, regional and international dental organisations, specialty groups and health authorities may all play significant roles.

When the legal aspects of patient safety are concerned, it was shown that bad outcomes occurred in dentistry and sometimes these were the results of dental errors12. In both cases, it is argued that apologies are very important in maintaining a relationship with the patient that is based on trust and mutual respect. Nevertheless, apologies are often not forthcoming in dentistry for a number of reasons that deserve careful examination. In particular, the dentist’s fear that an apology will increase the risk of legal consequences may need additional concern18. It is certainly very important that health-care organisations develop a systems orientation to patient safety, rather than an orientation that attaches blame to individuals2.

The development and availability of standards/guidelines for patient safety can serve many purposes (e.g. establishing minimum levels of performance, consistency or uniformity across multiple individuals and organisations, and setting expectations for the organisations and health professionals affected by the standards)2. In general, in most parts of the world there are no specific documents, standards/guidelines or direct laws or regulations about patient safety in dentistry; however, some guides or manuals are available to assist dental professionals. In recent years, a large number of public and private organisations have been created, a large portion of which originate in the world of medicine. They have the objective of enhancing patient safety. The data appear to indicate that dentistry has fallen behind in this regard. Although there have been some initiatives on specific aspects in a wide range of organisations (FDI, American Dental Association, Council of European Dentists, General Dental Council, etc.), there does not appear to be one single entity with the sole mission of bringing together all of the knowledge and initiatives to focus on patient safety in dentistry12. The present study, in addition to the limited documentation regarding patient safety, confirms the fact that, in a significant number of countries, laws/regulations regarding patient safety and risk management are also not available.

Errors can be defined as the outcomes or patterns of outcomes one does not want and they may be classified as basically of two types: those that occur naturally as rare outcomes of effective processes and those that signal that the process is not working. Focusing on the latter is suggested to be vital for prevention of errors in health care19. Errors made by clinicians in dental practice usually require changes in the original planning of patient management17. Again, for this purpose, analysis of errors and awareness and knowledge in the field of patient safety and risk management is required. Further, assessment of the patient safety culture among dental practitioners may also be required10. One of the most important barriers to improving patient safety seems to be the lack of awareness of the extent to which errors occur daily in all health-care settings and organisations, which is likely to exist because the vast majority of errors are not reported, and they are not reported because personnel fear they will be punished2.

The error rate in medicine is known to be alarmingly large19 and discontent and litigation among patients is a problem that increasingly preoccupies the medical profession. It has been suggested that a considerable proportion of lawsuits originate from misunderstandings and not from treatment errors. Surgeons often concentrate on the legal requirements of informed consent and neglect to explain the practical consequences of the operation; the patients in turn tend not to ask about possible complications20. The error rate has not been looked at in dentistry. However, the prevention of error can only be developed by recognising and analysing the error itself7., 12., 19. and there seems to be a need for a better and thorough analysis of the errors in dentistry7.

A fundamental feature of the culture of patient safety is sharing of experiences as this provides the opportunity to learn from mistakes, which may also be considered as an ethical duty21. It is well accepted that implementing a system for notification and recording of adverse events that take place in professional practice is essential for a thorough analysis of iatrogenic errors in dental surgery22. According to Perea-Perez et al.,12 ‘Gaining knowledge of risk situations is basic to the implementation of any risk management system. To do so, it is necessary to have a reliable notification system for any type of adverse event, which ensures the anonymity of the person who reports it. It makes no sense to have information on adverse events if that information is not properly analysed through systems designed for the study of these events (e.g. root cause analysis, CRA) and prevention of other possible adverse events (e.g. failure mode and effects analysis, FMEA).

In contrast, most attention in patient safety has been paid to emergency preparedness8 and patient safety in hospitals. However, in many countries, patients receive most of their health care in primary-care settings20. The results of the survey also show us that, in the dental field, patient safety is limited mainly to infection control and radiation protection, while other important aspects of patient safety are addressed only in a few of the countries. This does not seem to comply well with the broader context of patient safety1, and dentistry seems to be in need of revising this limited understanding and implementation of patient safety into daily dental practice7. To achieve a threshold improvement in patient safety, market and regulatory strategies, public and private strategies, and strategies that are implemented inside health-care organisations, as well as in their external environment, also need consideration, and all of these strategies need to be employed in a balanced and complementary fashion2.

Further, the results of the survey generally revealed that, although patient safety is/has been a genuine concern for the profession, greater efforts are needed where the implementation of patient safety and risk management topics into the undergraduate dental curriculum, development of materials aiming at improving the knowledge and awareness of dental practitioners, working together for national laws/regulations for the improvement of patient safety and having a widely accepted culture of patient safety are concerned.

Acknowledgement

The authors thank to all member NDAs of FDI that kindly participated in this survey.

REFERENCES

- 1.WHO . WHO Press; France: 2011. Patient Safety Curriculum Guide for Medical Schools. Available from: www.who.int/patientsafety/activities/technical/medical_curriculum/en/index.html. Accessed October 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kohn LT, Corrigan JM, Donaldson MS. The Quality of Health Care in America Committee of the Institute of Medicine (IOM) National Academy Press; Washington, D.C.: 2009. To err is human: building a safety health system. Available from: http: www.nap.edu/openbook.php?record_id=9728&page=R1. Accessed 25 October 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mendonça JM, Lyra DP, Jr, Rabelo JS, et al. Analysis of detection of dental prescribing errors at primary health care units in Brazil. Pharm World Sci. 2010;32:30–35. doi: 10.1007/s11096-009-9335-7. E-pub: 2009 Oct 30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Paker I, Alkut MT. Evaluation of radiographic errors made by undergraduate students in periapical radiography. N Y State Dent J. 2009;75:45–48. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Solaiman T. Implant failure: attempting procedures beyond skill level. J Calif Dent Assoc. 2009;37:850–852. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bortoluzzi MC, Manfro R, De Déa BE, et al. Incidence of dry socket, alveolar infection, and postoperative pain following the extraction of erupted teeth. J Contemp Dent Pract. 2010;11:E033–E040. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Perea-Pérez B, Santiago-Sáez A, García-Marín F, et al. Patient safety in dentistry: dental care risk management plan. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal. 2011;16:e805–e809. doi: 10.4317/medoral.17085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Glotzer DL, Psoter WJ, Rekow ED. Emergency preparedness in the dental office. J Am Dent Assoc. 2004;135:1565–1570. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.2004.0083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sammer CE, Lykens K, Singh KP, et al. What is patient safety culture? A review of the literature. J Nurs Scholarsh. 2010;42:156–165. doi: 10.1111/j.1547-5069.2009.01330.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Leong P, Afrow J, Weber HP, et al. Attitudes toward patient safety standards in U.S. dental schools: a pilot study. J Dent Educ. 2008;72:431–437. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Givol N, Rosen E, Taicher S, et al. Risk management in endodontics. J Endod. 2010;36:982–984. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2010.03.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Perea-Perez B, Santiago-Saez A, Labajo-Gonzalez ME, et al. Professional liability in oral surgery: legal and medical study of 63 court sentences. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal. 2011;16:e526–e531. doi: 10.4317/medoral.16.e526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lee JJ, Hahn LJ, Kao TP, et al. Post-tooth extraction sepsis without locoregional infection – a population-based study in Taiwan. Oral Dis. 2009;15:602–607. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-0825.2009.01596.x. Epub 2009 Jul 8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chatzoudi M. Handling post-dental extraction patients: how to avoid trans-infection of blood-borne diseases. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2009;67:2583–2586. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2009.04.076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gorter RC, Albrecht G, Hoogstraten J, et al. Professional burnout among Dutch dentists. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 1999;27:109–116. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0528.1999.tb01999.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rogers C, Malone KM. Stress in Irish dentists: developing effective coping strategies. J Ir Dent Assoc. 2009;55:304–307. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Peleg O, Givat N, Halamish-Shani T, et al. Wrong tooth extraction: root cause analysis. Quintessence Int. 2010;41:869–872. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schwartz B. Errors in dentistry: a call for apology. J Am Coll Dent. 2005;72:26–32. Summer. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chambers DW. Errors. J Am Coll Dent. 2003;70:31–35. Summer. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Krause HR, Bremerian A, Rustemever J. Reasons for patients’ discomfort and litigation. J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 2001;29:181–183. doi: 10.1054/jcms.2001.0212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yamalik N, Perea PB. Patient safety and dentistry: what do we need to know? Fundamentals of patient safety, the safety culture and implementation of patient safety measures in dental practice. Int Dent J. 2012;62:189–196. doi: 10.1111/j.1875-595X.2012.00119.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Harmsen M, Gaal S, von Dumen S, et al. Patient safety in Dutch primary care: a study protocol. Implement Sci. 2010;5:50. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-5-50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]