Abstract

Objectives: The aim of this study was to examine non-cavitated approximal caries using non-invasive treatment methods. Materials and methods: Molar and premolar teeth with approximal caries were used in this in vivo study. Approximal caries lesions were evaluated with visual and radiographic inspection and with the DIAGNOdent device. Five groups were formed to study non-invasive treatment, and each had at least 25 early approximal carious lesions. Patients in the control group were not treated. After the separation, either ozone application, acidulated phosphate fluoride gel, CPP-ACP-containing material (Tooth Mousse), or an antibacterial bonding agent (Clearfil Protect Bond) was used. For 18 months after the non-invasive treatment, radiological controls were used to observe the progress of the initial and approximal caries in the 1st, 3rd, 6th and 12th months of follow-up. A Mann–Whitney U-test was used to perform the statistical analysis; in-group comparisons were made with the Wilcoxon signed-rank test, and a quantitative assessment was performed using a chi-squared test. Results: At the end of 18 months, the caries lesions in the control group were observed to progress (P < 0.01). The lesions that were scored as 1a during a visual inspection recovered by using non-invasive treatments. Conclusion: Approximal caries lesions that were detected at the early stages remained stationary when using antibacterial agents and materials that promoted remineralisation. Clinical relevance: Antibacterial agents and remineralisation materials can be used in treatment of early approximal caries lesions.

Key words: Non-cavitated caries lesions, remineralisation, ozone, casein phosphopeptide amorphous calcium phosphate, antibacterial resin infiltration, fluoride

INTRODUCTION

Dental caries is the most prevalent chronic disease of childhood, and teenagers manifest caries when they reach adulthood1. These lesions are most often diagnosed as approximal caries2.

Caries is traditionally detected by a combination of visual examination and probing. Probing pressure may damage the enamel over the subsurface of a carious lesion, which increases the risk of progression. Therefore, non-invasive methods are preferable to detect caries3. The detection of new caries and quantification techniques have been developed and investigated. These techniques include improvements in electronic resistance measurements, light scattering, quantitative laser or light-induced fluorescence, fibre-optic trans-illumination, magnetic resonance micro-imagery, ultrasound and digital radiography4., 5., 6..

The high rate of initial caries and its impact on further caries development underline the need to explore new strategies for caries prevention and therapy1. According to recent research, there are two different methods of stopping non-cavitated early caries lesions. One approach is to remineralise the lesion body with therapeutic agents, such as fluoride or casein phosphopeptide amorphous calcium phosphate (CPP-ACP). The other approach is to protect the lesion body from microorganisms by applying antibacterial agents, such as ozone, and resin infiltration.

Enamel caries lesions are characterised by the loss of mineral in the lesion body, while the surface remains highly mineralised. In the early stage, non-cavitated lesions and caries extending up to the dentine-enamel junction can be arrested or/and remineralised if therapeutic agents are applied for tissue healing7. The common treatment for enamel caries is the application of different fluorides, such as gels, varnishes and fluoride-releasing materials8. Fluoride is currently accepted as an effective topical agent for preventing caries by promoting enamel remineralisation with fluorapatite9., 10.. Topical fluoride has been recommended for the non-invasive treatment of incipient enamel subsurface lesions, particularly if the risk factors of poor oral hygiene and high-caries-risk diet are also targeted9., 10., 11..

Bioactive agents based on milk products have also been developed to release the elements that enhance the remineralisation of enamel and dentine under cariogenic conditions12. This activity has been attributed to the direct chemical effects of phosphoprotein casein and the calcium phosphate components in cheese. The mechanism of action of CPPs involves the ability to stabilise calcium phosphate in solution by binding ACP with their multiple phosphoserine residues, which allows small CPP-ACP clusters to form13. A multifactorial anti-cariogenic mechanism has been proposed for CPP-ACP. It has been claimed that CPP-ACP promotes remineralisation of the carious lesions by maintaining a supersaturated state of enamel mineral12., 14..

The most common methods of treating proximal caries lesions are currently either non-invasive or invasive15. Invasive approaches, such as sealing or resin infiltration, might bridge the gap between non-invasive and minimally invasive treatment options for proximal caries lesions16. On occlusal surfaces, fissure sealing is an effective method of preventing caries formation and lesion progression. Dental sealants and adhesives are not optimised for high penetrability and only show superficial penetration into natural enamel lesions. Using temporary tooth separation, the proximal non-cavitated caries lesions are sealed with dental adhesives17. Resin infiltration has been suggested as a new secondary prevention approach for active superficial proximal lesions that have penetrated deep into the enamel or just into the dentine1., 16., 18., 19., 20., 21.. Imazato et al.22 reported that incorporating the antibacterial monomer 12-methacryloyloxydodecylpyridinium bromide (MDPB) effectively provided a self-etching primer with antibacterial activity before curing. This monomer is synthesised by combining an antibacterial agent and a methacryloyl group; it shows antibacterial activity against oral bacteria23., 24..

Ozone treatment can be considered an alternative management strategy. The powerful ability of ozone to inactivate microorganisms has led to its use in water disinfection25. The gaseous or aqueous phases have a strong oxidising power and a reliable microbiocidal effect26. It has been reported that ozone treatment can reduce the total number of microorganisms and rehabilitate most of the root carious lesions27. Ozone works by breaking up the cell walls of bacteria, viruses and fungi, and breaking up sulphur compounds into non-smelling compounds. Ozone also kills the acid-producing bacteria that grow out of control and cause decay28. Santiago et al.1 found that the therapeutic sealants acted as a non-invasive treatment for early approximal enamel lesions.

The aim of this study was to examine the effectiveness of different non-invasive regimens on the non-cavitated approximal caries lesions over an 18-month period in vivo. The research hypothesis was that the presence of therapeutic agents and antibacterial agents prevents the non-cavitated approximal caries lesion surfaces from demineralisation and increases the remineralisation of these lesions.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Medicine, Istanbul University (25/04/2007-801). The study was conducted in full accordance with the World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki.

This study included 158 non-cavitated approximal caries lesions of the molar or premolar teeth in 42 patients. The patients visited the dental clinics at the Operative Department of Istanbul University, Faculty of Dentistry. Each patient provided informed written consent, and the ethics committee form was signed by each patient at the beginning of the study. In each patient, it was the aim to select one approximal site (two contacting surfaces) per quadrant. The clinical inclusion criteria were that the contacting surfaces should be without any fillings and different posterior tooth types should be involved. The following exclusion criteria were applied:

-

1

Patient use of any periodontal operation or topical fluoride application in the last 6 months.

-

2

Patient use of any special toothpaste, antibiotics or antibacterial mouthwash in the last 2 months.

-

3

Poor oral hygiene and poor tooth brushing techniques.

The importance of oral hygiene was discussed with the patients. At baseline and before the treatment, all of the subjects were prescribed a course of oral hygiene instructions followed by scaling and polishing with non-fluoride-containing paste. Professional instruction was given on brushing, floss use and interdental brushes. At the initial stage, 158 teeth with approximal caries lesions were clinically detected and diagnosed.

Approximal caries was evaluated by visual examination, radiographic examination and laser fluorescence examination. Five groups were created to analyse the non-invasive treatment of non-cavitated approximal caries lesions (n = 25). One of these groups served as the control group. After temporary tooth separation, the remaining four groups were treated with ozone (Healozone; KaVo Dental, Biberach/Riss, Germany), 1.23% acidulated phosphate fluoride gel (APF) (Sultan Dental Products, Hackensack, NJ, USA), CPP-ACP (Tooth Mousse; GC International, Itabashi-ku, Tokyo, Japan) or antibacterial bonding agent (Clearfil Protect Bond; Kuraray, Kurashiki, Okayama, Japan).

Assessment parameters

To gain access to the approximal space and confirm the presence of enamel lesions and their clinical status in the test groups, temporary tooth separation was performed1., 29.. An orthodontic elastic separator (American Orthodontics Corp., Sheboygan, WI, USA) was placed around the approximal contact area involving the affected tooth for 2 days. Pliers were used to stretch the separator and to snap it in between the two teeth. In most cases, the space obtained after tooth separation was between 0.5 mm and 1 mm. The surface was gently cleaned with pumice (Detartrine, Septodont; Saint-Mour-des-Fosses Cedex, France). The approximal area was cleaned with explorer and dental floss without wax (Oral-B Laboratories, Iowa City, IA, USA)29., 30., 31., 32..

Visual clinical examination

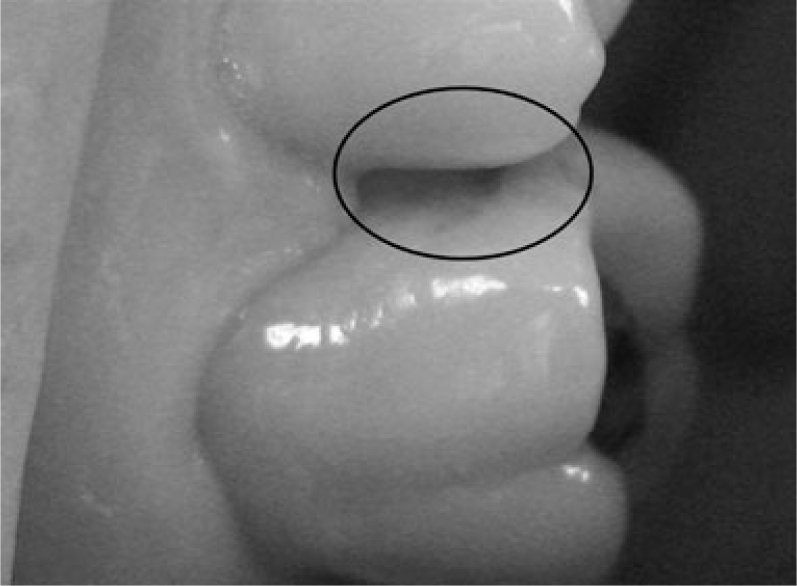

A visual examination of the lesions was made using the modified criteria described by Ekstrand33 (Table 1). Teeth that were scored 0 (Figure 1), 1a (Figure 2), 1b (Figure 3), 2a (Figure 4) and 2b (Figure 5) were included in the study.

Table 1.

Visual score system

| Score 0 | No change or slight change in enamel translucency after prolonged air drying (>5 seconds) |

| Score 1a | Opacity (white) hardly visible on the wet surface but distinctly visible after air drying (Figure 1) |

| Score 1b | Opacity (brown) hardly visible on the wet surface but distinctly visible after air drying (Figure 2) |

| Score 2a | Opacity (white) distinctly visible without air drying (Figure 3) |

| Score 2b | Opacity (brown) distinctly visible without air drying (Figure 4) |

| Score 3 | Localised enamel breakdown in opaque or discoloured enamel and/or greyish discolouration from the underlying dentine (Figure 5) |

| Score 4 | Cavitation in opaque or discoloured enamel exposing the dentine beneath |

Figure 1.

Visual examination score 1a.

Figure 2.

Visual examination score 1b.

Figure 3.

Visual examination score 2a.

Figure 4.

Visual examination score 2b.

Figure 5.

Visual examination score 3.

After washing and drying with contaminant-free compressed air, a cotton roll was applied. The visual examination of the approximal surface included an assessment of the colour, stain and verification of a non-cavitated carious lesion state according to the visual examination criteria.

Radiographic examination

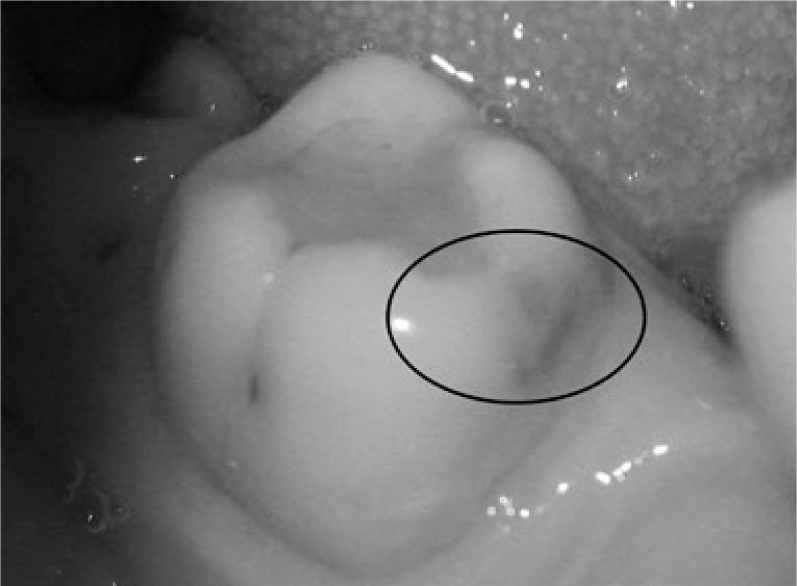

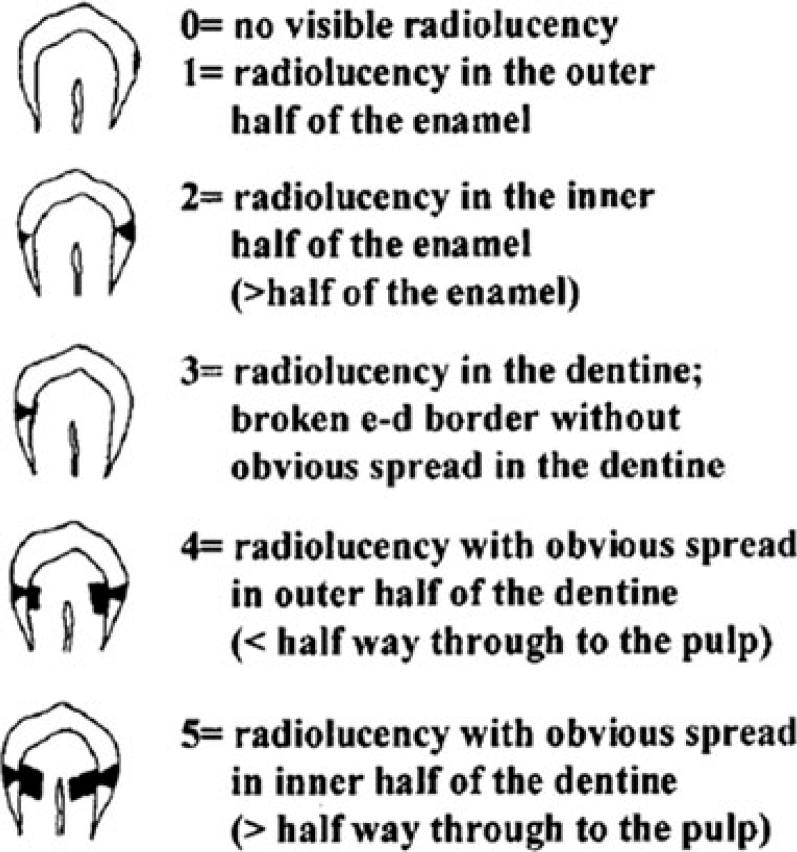

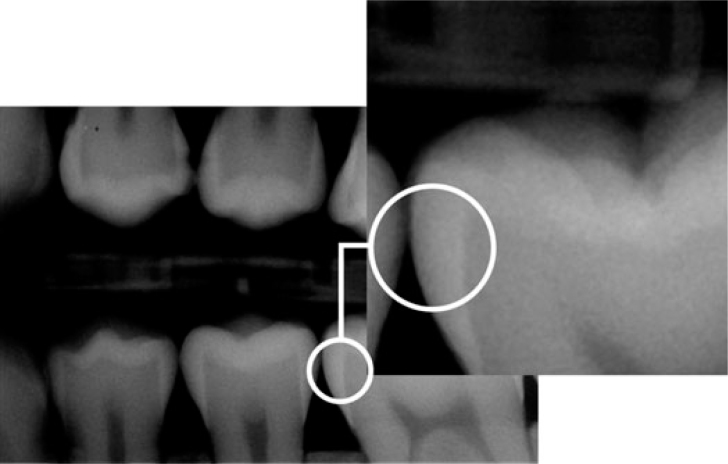

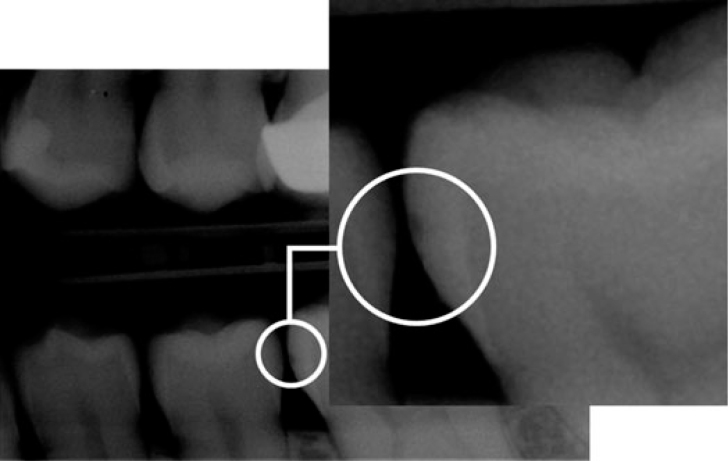

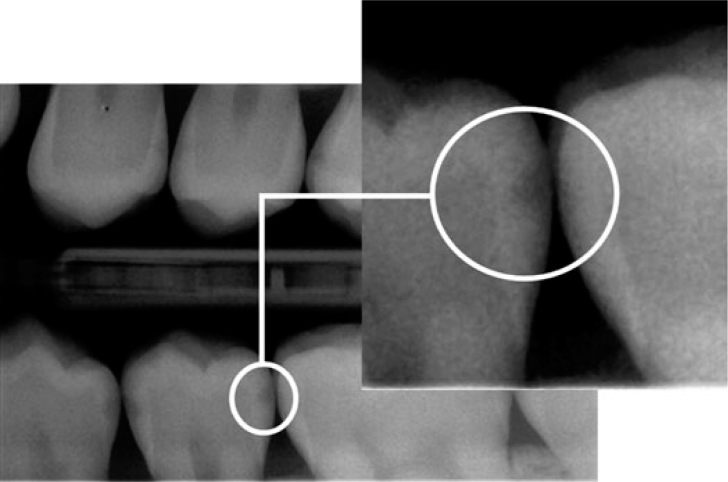

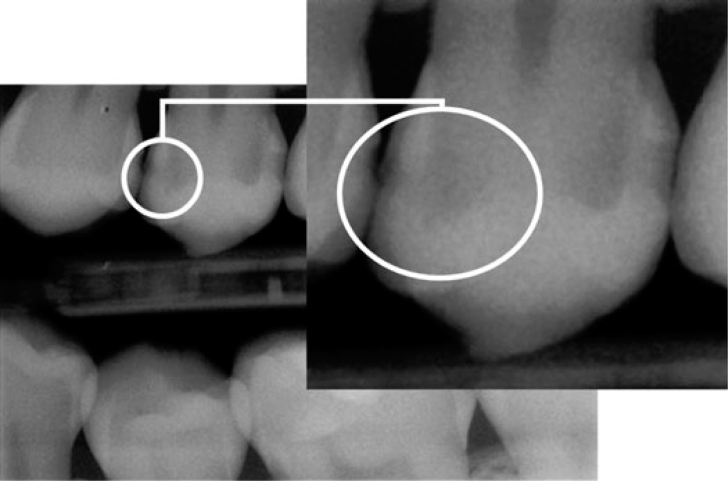

A radiographic examination of the lesions was made by bitewing radiography using the Stenlund34 scoring system (Table 2, Figure 6). Teeth that were scored 0 (Figure 7), 1 (Figure 8) and 2 (Figure 9) were included in the study. Teeth that were scored 3 (Figure 10) were excluded from the study.

Table 2.

Radiographic score system

| Score 0 | No visible radiolucency (Figure 7) |

| Score 1 | Radiolucency in the outer half of the enamel (Figure 8) |

| Score 2 | Radiolucency in the inner half of the enamel (Figure 9) |

| Score 3 | Radiolucency in the dentine; broken enamel–dentine border without obvious spread in the dentine (Figure 10) |

| Score 4 | Radiolucency with obvious spread in the outer half of the dentine |

| Score 5 | Radiolucency with obvious spread in the inner half of the dentine |

Figure 6.

Radiographic scores used to classify the depth of approximal caries lesions34.

Figure 7.

Radiographic examination score 0.

Figure 8.

Radiographic examination score 1.

Figure 9.

Radiographic examination score 2.

Figure 10.

Radiographic examination score 3.

Two posterior bitewing radiographs were taken on each side of the dentition with a head X-ray machine (Kodak, Trophy ETX Type: Irix 79, No: TIXH042, Beoubourg, France) under standardised conditions: 0.2 seconds, 70 kV and 8 mA. The film–tooth–tube distances were fixed by using a Kwik-Bite Senso Cover (Have-Neos Dental, Bioggio, Switzerland). The radiographs used for the study included the DDR (Vatec Model: HDS-100L, Lot: HDS100L-A133, Gyeonggi-do, Korea) with the Ezx-plus V3.3006 programme. The approximal surfaces (4 distal–7 mesial) were assessed for caries using a radiographic scoring system.

Laser fluorescence examination

Laser fluorescence examination was performed using the DIAGNOdent device (Type 2095, Sn 05-1519775; Kavo) and the score system of the manufacturer (Table 3). Teeth that were scored 0, 1 and 2 were included in the study.

Table 3.

Laser fluorescence score system

| Score 1 | Laser fluorescence score 0–4, no caries or white opaque lesions |

| Score 2 | Laser fluorescence score 5–10, enamel caries limited to the outer half of the enamel thickness |

| Score 3 | Laser fluorescence score 11–20, enamel caries limited to the inner half of the enamel thickness without obvious spread in the dentine |

| Score 4 | Laser fluorescence score ≥21, caries spread in the dentine |

The assessment of a tooth using the laser fluorescence system took place as follows: after calibration with a ceramic standard, the fluorescence of a sound spot on the smooth surface of the tooth was measured to provide a baseline value; this value was then subtracted electronically from the fluorescence of the site to be measured; finally, the tip of the laser device was placed on the approximal site and rotated around a vertical axis until the highest fluorescence reading was found. The teeth were assessed according to the scoring system described earlier.

Treatment groups

Patients were randomly assigned into five groups.

Group 1: nothing was applied in the control group.

Group 2: for fluoride treatment, APF was applied with a fine brush to the approximal surfaces chosen for 1 min.

Group 3: gaseous ozone was applied once for 40 seconds to the approximal surfaces without the use of remineralising solution.

Group 4: for CPP-ACP treatment, Tooth Mousse was applied with a microbrush to the approximal surfaces chosen. A CPP-ACP gel was given to the patients to use for 1 week.

Group 5: MDPB containing an antibacterial dentine bonding agent was applied according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The bonding was applied (Primer for 20 seconds, bonding agent for 10 seconds), and the light was cured (600 mW/cm2) (Bisco, Bisco VIP, Schaumburg, IL, USA).

Evaluation

The patients were clinically examined 1, 3, 6, 12 and 18 months later. Posterior bitewing radiographs were taken with a Kwik-Bite sensor film holder to control for the lesions. The radiographs, visual examination scores and DIAGNOdent values from baseline to 18 months were examined and then analysed blindly by one observer. The radiographs were transferred to the 16-inch laptop computer using Microsoft Office Picture Manager with 0 brightness, 0 contrasts, 0 mid-tones, 0 highlight, and 0 shadows setting in an isolated room lit with 75 watts. The approximal surfaces were classified according to the scoring index (Table 2).

Statistical analysis

The Number Cruncer Statistical System 2007 and PASS 2008 Statistical Software (NCSS, East Kaysville, UT, USA) package was used for the statistical analyses. During the evaluation of the study data, along with the descriptive statistical methods (frequency), the parameters that did not have a normal distribution were evaluated using the Mann–Whitney U-test and the Wilcoxon signed-rank test. The qualitative data were evaluated using a chi-squared test. The results were given with 95% confidence intervals and significance was defined as P < 0.05.

RESULTS

The lesions on the approximal tooth surface spaces between the first molars and second molars were characterised by a whitish/brownish discolouration of the enamel. A total of 158 posterior tooth surfaces with this appearance were treated. Thirty-three served as a control, ozone gas was applied to 27 posterior tooth surfaces, 33 were treated with fluoride, 33 were treated with antibacterial dentine bonding and 32 were treated with CPP-ACP. After 18 months, all of the patients were available for re-examination. The progression of the approximal caries lesions during the experimental period in relation to the baseline status is presented in Table 4.

Table 4.

Mean values (M) and standard deviation (SD) of baseline and 18-month scores of the groups

| Visual examination n (%) |

P | Radiographic examination n (%) |

P | DIAGNOdent measurements M ± SD | P | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1a | 1b | 2a | 2b | 3 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | ||||||

| Control group | 0 | – | 18 (54.5) | 9 (27.3) | 0 (0) | 6 (18.2) | 0 (0) | 0.001** | 12 (36.4) | 18 (54.5) | 3 (9.1) | 0 (0) | 0.001** | 14.82 ± 8.18 | 0.001** |

| 18. M | 0 (0) | 9 (27.3) | 9 (27.3) | 0 (0) | 11 (33.3) | 4 (12.1) | 2 (6.1) | 22 (66.7) | 2 (6.1) | 7 (21.2) | 24.24 ± 22.26 | ||||

| Ozone group | 0 | – | 3 (11.1) | 14 (51.9) | 2 (7.4) | 8 (29.6) | 0 (0) | 0.214 | 4 (14.8) | 20 (74.1) | 3 (11.1) | 0 (0) | 0.008** | 17.29 ± 8.65 | 0.025* |

| 18. M | 4 (14.8) | 0 (0) | 7 (25.9) | 3 (11.1) | 13 (48.1) | 0 (0) | 2 (7.4) | 18 (66.7) | 6 (22.2) | 1 (3.7) | 15.07 ± 7.37 | ||||

| Fluor group | 0 | – | 13 (39.4) | 10 (30.3) | 1 (3.0) | 9 (27.3) | 0 (0) | 0.134 | 6 (18.2) | 17 (51.5) | 10 (30.3) | 0 (0) | 0.001** | 18.73 ± 16.45 | 0.013* |

| 18. M | 5 (15.2) | 3 (9.1) | 10 (30.3) | 2 (6.1) | 12 36.4) | 1 (3.0) | 2 (6.1) | 13 (39.4) | 14 42.4) | 4 (12.1) | 25.91 ± 21.30 | ||||

| A. Bonding group | 0 | – | 17 (51.5) | 10 (30.3) | 2 (6.1) | 4 (12.1) | 0 (0) | 0.698 | 8 (24.2) | 21 (63.6) | 4 (12.1) | 0 (0) | 0.035** | 14.51 ± 12.35 | 0.302 |

| 18. M | 9 (27.3) | 8 (24.2) | 8 (24.2) | 1 (3.0) | 4 (12.1) | 3 (9.1) | 7 (21.2) | 19 (57.6) | 4 (12.1) | 3 (9.1) | 17.94 ± 22.26 | ||||

| CPP-ACP group | 0 | – | 12 (37.5) | 17 (53.1) | 1 (3.1) | 2 (6.3) | 0 (0) | 0.32 | 17 (53.1) | 14 (43.8) | 1 (3.1) | 0 (0) | 0.166 | 12.03 ± 4.73 | 0.011* |

| 18. M | 6 (18.8) | 12 (37.5) | 9 (28.1) | 1 (3.1) | 4 (12.5) | 0 (0) | 16 (50.0) | 12 (37.5) | 3 (9.4) | 1 (3.1) | 9.72 ± 6.66 | ||||

CPP-ACP, casein phosphopeptide amorphous calcium phosphate.

Wilcoxon sign test.

Bold values indicate statistically significant difference.

*P ≤ 0.05 **P ≤ 0.01.

In the control group, four of the 33 surfaces (12.1%) had a score of 3 on visual examination. The radiographic examination and DIAGNOdent measurements also showed progression of the dentine lesions. After 18 months, a visual score of ‘0’ could not be detected. All of the score differences between the baseline and experimental period were statistically significant (P < 0.01; Table 5).

Table 5.

Statistical comparison of the treatment groups versus the control group

| Visual examination | Radiographic examination | DIAGNOdent | |

|---|---|---|---|

| APF | χ2: 11.896; P: 0.036* | χ2: 12.132; P: 0.007** | Z: −0.218; P: 0.827 |

| Ozone | χ2: 20.017; P: 0.001** | χ2: 6.364; P: 0.095 | Z: −1.377; P: 0.169 |

| Antibacterial dentine bonding | χ2: 13.706; P: 0.018* | χ2: 5.430; P: 0.143 | Z: −3.171; P: 0.002** |

| CPP-ACP | χ2: 14.683; P: 0.012* | χ2: 18.519; P: 0.001** | Z: −4.479; P: 0.001** |

APF, acidulated phosphate fluoride gel; CPP-ACP, casein phosphopeptide amorphous calcium phosphate.

χ2, chi-squared test; Z, Mann–Whitney U-test.

*P < 0.05 **P < 0.01.

For the APF-treated surfaces, there was no progression on visual examination (P > 0.05). However, the radiographic examination (P < 0.01) and DIAGNOdent measurements were statistically significant (P < 0.05). The APF gel application visual examination (P < 0.05) and radiographic examination were statistically significant (P < 0.01) for the control group, but there was no progression in the DIAGNOdent measurements (P > 0.05) (Table 5).

For the ozone application group, there was no progression on visual examination (P > 0.05), but radiographic examination (P < 0.01) and DIAGNOdent measurements (P < 0.05) were statistically significant. The ozone application visual examination (P < 0.01) was statistically significant for the control group, but there was no progression on radiographic examination and DIAGNOdent measurements (P > 0.05; Table 5).

For the antibacterial dentine bonding group, there was no progression in the visual examination (P > 0.05) and DIAGNOdent measurements (P > 0.05), but the radiographic examination was statistically significant (P < 0.05). The antibacterial dentine bonding visual examination (P < 0.05) and DIAGNOdent measurements (P < 0.01) were statistically significant for the control group but there was no progression on radiographic examination (P > 0.05; Table 5).

For the CPP-ACP application group, there was no progression on visual examination (P > 0.05) and radiographic examination (P > 0.05), but the DIAGNOdent measurements were statistically significant (P < 0.05). Visual examination (P < 0.05) was statistically significant for the control group. The radiographic examination and DIAGNOdent measurements were also statistically significant (P < 0.01) (Table 5).

DISCUSSION

In this in vivo study, we examined the effects of different anti-cariogenic agents on approximal enamel caries using three diagnostic methods. Studies have shown that combining different diagnostic methods improved the detection of lesion activity33., 35..

Subjects from both groups were provided with a steady supply of fluoridated toothpaste and toothbrushes. All of the subjects were notified annually of their oral health status and copies of their radiographs were supplied to their chosen dental care provider. To the extent that it was possible to control in a large clinical trial, the only point of difference in terms of dental caries prevention was the inclusion of different non-invasive techniques.

Ismail (2004) described and discussed the content validity of a sample of caries detection criteria reported in the literature between January 1, 1966, and May 1, 2000. He reported that the content validity of the 29 criteria systems were substantially variable in the disease processes measured, inclusion and exclusion criteria, and examination conditions3. Our study used the classification described by Ekstrand. In this classification, non-cavitated enamel lesion detection was easier than other methods. Sheehy et al.36 and Stenlund et al.34 also used this classification in their study, and they reported that the visual system of caries detection was validated in vivo by histological examinations in the laboratory.

The combination of visual examination and bitewing radiography could enhance the correct diagnosis of dentine caries in permanent teeth1., 37.. Hintze et al.31 controlled the approximal white spot enamel lesions with bitewing radiographs for every six mounts for 2.5 years. They reported that more approximal surfaces were detected with bitewing radiographs31.

In the present study, the radiographic examination of lesions was made by bitewing radiography using the Stenlund (2002) scoring system. Previous investigations reported good reliability with this scoring system34., 38., 39..

Demineralisation can be detected using different methods. White spot lesions are not visually detectable until they have progressed to 200–300 μm into the enamel. Some of the diagnostic methods used are quantitative light fluorescence, electrical resistance caries monitoring device, fibre-optic trans-illumination, optical coherence tomography and laser fluorescence40. DIAGNOdent uses laser fluorescence to measure early demineralisation. Various reports in the literature have shown the value of DIAGNOdent as a reliable non-invasive caries-detecting device41. In this study, the DIAGNOdent device was used to detect early enamel caries lesions.

The results of this trial are presented using data obtained from standardised digital radiographs, visual examination and DIAGNOdent values. The assessment of the effectiveness of a preventive agent when an incipient lesion is detected requires diagnostic criteria that are highly refined and reproducible. A recent review of approximal caries diagnosis reported higher sensitivities for bitewing radiography than with fibre-optic trans-illumination and visual tactile assessment42. An additional advantage of radiographs is that the images can be stored indefinitely and are able to be reviewed under standardised conditions at any time. The radiographic methodology used in this study (standardised measurements, low dosage exposure and digital recording, and the use of dedicated on-site radiography) ensured that the effect of these issues was minimised. Standardised digital radiographic procedures in conjunction with a scoring method that grades lesion depth could potentially provide the most appropriate method of determining early carious lesion development in large-scale clinical trials and are particularly appropriate in a population with a low prevalence of caries.

The radiological scores of the control group showed statistically significant differences. The radiological measurement (score 0) was 36.4% at baseline and decreased to 6.8% after 18 months. This finding was similar to the visual examination and DIAGNOdent scores. Stenlund et al.34 reported that the individual-based incidence was 19 first new approximal lesions per 100 person-years. In our study, the incidence of new cavity formation was 21.2%, which was similar to the results of Stenlund’s study. After the 18-month trial, the radiological findings showed that the caries lesions reached to the dentine. These lesions needed drilling and filling.

Demineralisation takes place when specific bacteria are retained for a long time on the enamel surface. The bacteria metabolise fermentable carbohydrates and produce organic acids. These acids dissolve the calcium phosphate mineral of the enamel and dentine, resulting in demineralisation43. For this reason, we try to remove the acidogenic bacteria from the approximal area to prevent caries activity or to stop early caries lesions. The application of ozone as an oral antiseptic was used to prevent caries activity44., 45.. Baysan et al.27 reported that application of ozone gas was capable of reducing the numbers of Streptococcus mutans and Streptococcus sobrinus on saliva-coated glass beads. Holmes46 reported that leathery non-cavitated primary root caries can be arrested non-operatively with ozone and remineralising products. In a different study, ozone gas was used after cavity preparation and had striking antimicrobial effects against S. mutans. The result of the study showed that the application of ozone with the Heal-Ozone device (Healozone; KaVo Dental, Biberach/Riss, Germany) was a very promising therapy for eliminating residual microorganisms in deep cavities; therefore, it may potentially increase the clinical success of restoration28. In our study, the radiological scores of the ozone application group showed significantly different values. According to our results, the scores of the inner half of the enamel lesions (score 2) increased, but the scores of the outer half of the enamel lesions (score 1) were stable. There were no statistically significant differences in the visual examination values, but the results of the DIAGNOdent values were significantly different. Based on these values, we can say that ozone gas application removed the microorganisms in the outer half of the enamel lesions and stopped the demineralisation activity. However, ozone gas application did not remove the microorganisms in the deeper lesions. Baysan and Lynch47 reported that ozone might enhance the remineralisation of dentine, but results from Zaura et al.48 failed to confirm this hypothesis. They reported that clinically relevant exposure to ozone gas did not have a hazardous effect on dentine.

Clearfil Protect Bond has been developed as a self-etching/priming system. It has a cavity disinfecting effect with admixture of the acidic antibacterial monomer, MDPB, into the primer solution. Clearfil Protect Bond primer has a pH value of 2.023. It has been reported that a dentine primer incorporating MDPB showed antibacterial activity against oral microorganisms, such as S. mutans, before and after curing49. In a previous study of low-viscosity resins (infiltrates) based mainly on triethylene glycol dimethacrylate (TEGDMA), high penetration coefficients were capable of almost completely inhibiting the progression of natural enamel caries lesions in a low-demineralising environment50.

After 18 months, there were statistically significant differences in the DIAGNOdent values of the Clearfil Protect Bond group, but the radiological values remained stable. The score 1a values increased to 27.3%. This score showed that the MDPB-containing adhesive healed the white spot lesions. MDPB-containing adhesives did not participate in the remineralisation process. However, the application of adhesive removed the microorganisms in the lesion, and the daily use of fluoridated toothpaste may have played a role in the remineralisation process. The porous lesion surface was removed with the application of adhesive and this reduced the attachment of microorganisms to the tooth surface. Paris and Meyer-Lueckel16 reported that progression of the resin-infiltrated enamel lesions was significantly slower when compared with untreated lesions. In another study without acid conditioning, the surface layer of a non-cavitated natural caries lesion was a barrier that significantly prevented the penetration of a light-curing resin21. Paris and Meyer-Lueckel16 reported that resin infiltration was efficacious in preventing further demineralisation of artificial enamel caries lesions under cariogenic conditions.

Fluoride exposure has, however, not been completely successful from a long-term perspective39. This regimen has some limitations in high-risk and non-compliant patients, as well as with cavitated proximal lesions51., 52.. If the lesion progresses into the dentine, remineralising treatment often fails and operative treatment is generally recommended. With this therapy, infected tissue is commonly removed using burs and replaced with subsequent restoration42., 53.. In the present study, the radiographic examination values and the DIAGNOdent values showed that, after the 18-month trial, there were statistically significant differences in caries development. First, the visual inspection 1a scores decreased from 39.4% to 9.1%. This difference showed that fluoride application to approximal early lesions was not successful in the long-term. This finding was similar to those of Zantner et al.51. However, we motivated the patients regarding brushing and oral hygiene, but the control of the approximal surface plaque was difficult. The caries microorganisms in dental plaques were overshadowed by the effect of the fluoride application on non-approximal surfaces. In another study, professionally applied fluoride gel showed no statistically significant inhibitory effects on enamel and dentine lesions52. Several studies have shown that the application of fluoride to initial carious lesion results in surface remineralisation54., 55., 56..

The remineralising potential of CPP-ACP has been shown in animal studies57., 58., in vitro studies13., 14., 59. and in vivo studies12., 60.. It has been proposed that the anti-cariogenic mechanism of CPP-ACP resulted from ACP localisation at the tooth surface, which buffers the free calcium and phosphate ion activity and helps to maintain a state of supersaturation with respect to the enamel. This process leads to inhibition of demineralisation and promotion of remineralisation11. Another mechanism also favours remineralisation dynamics: CPPs were shown to stabilise ACP, to localise ACP in dental plaque and were anti-cariogenic in animal and in situ human caries models13., 58., 61., 62., 63.. Studies have shown that higher concentrations of CPP-ACP create more remineralisation60., 64.. In combination with fluoride, its effect on enamel remineralisation has also been investigated57., 65., 66.. The fluoride ions react with CPP-ACP to form CPP-amorphous calcium fluoride phosphate65. In the present study, we did not apply fluoride and CPP-ACP together. However, we propose that the daily use of fluoride toothpaste allowed for this type of synergistic activity on the enamel surfaces.

In clinical trials in patients with severe xerostomia, CPP-ACP in a mouth rinse revealed positive results in terms of caries prevention67. Ten Cate68 reported that fluoride enhanced mineral uptake during continuous remineralisation and inhibited mineral loss during demineralisation.

CONCLUSION

Based on the data from this study, we make the following conclusions: (1) CPP-ACP application depressed demineralisation of the non-cavitated enamel lesions and promoted remineralisation; (2) ozone gas application removed the microorganisms in the outer half of enamel lesions and stopped the demineralisation activity, however, ozone gas application cannot remove the microorganisms in deeper lesions; (3) MDPB-containing adhesives played no role in the remineralisation process; and (4) the daily use of fluoride in combination with other non-invasive techniques may enhance the treatment effectiveness of the approximal non-cavitated lesion.

Acknowledgement

We thank the Department of Restorative Dentistry of the Istanbul University Faculty of Dentistry.

Conflict of interest

None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Santiago SG, Cristian PB, Claes-Göran E. A 2-year clinical evaluation of sealed noncavitated approximal posterior carious lesions in adolescents. Clinical Oral Invest. 2005;9:239–243. doi: 10.1007/s00784-005-0010-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Majàre I, Källestål C, Stenlund H, et al. Caries development from 11 to 22 years of age: a prospective radiographic study. Prevalence and distribution. Caries Res. 1998;32:10–16. doi: 10.1159/000016424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ismail AI. Visual and visuo-tactile detection of dental caries. J Dent Res. 2004;83(Spec Iss C):56–66. doi: 10.1177/154405910408301s12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Assaf AV, Meneghim MC, Zanin L, et al. Assessment of different methods for diagnosis dental caries in epidemiological surveys. Commun Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2004;32:418–425. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0528.2004.00180.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Moore DJ, Wilson NHF. A review of modern non-invasive systems for caries detection. CPD Dentistry. 2001;2:86–90. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wenzel A. Digital radiography and caries diagnosis. Dentomaxillofac Radiol. 1998;27:3–11. doi: 10.1038/sj.dmfr.4600321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Featherstone JD. The continuum of dental caries – evidence for a dynamic disease process. J Dent Res. 2004;83(Spec No C):C39–C42. doi: 10.1177/154405910408301s08. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Donly KJ, Segura A, Wefel J S, et al. Evaluating the effects of fluoride-releasing dental materials on adjacent interproximal caries. J Am Dent Assoc. 1999;130:817–825. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.1999.0305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ekstrand J, Fejerskov O, Silverstone LM. Munksgaard; Copenhagen: 1988. Fluoride in Dentistry. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Thylstrup A, Fejerskov O. Munksgaard; Copenhagen: 1986. Textbook of Cariology. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cross KJ, Huq NL, Reynolds EC. Casein phosphopeptides in oral health – chemistry and clinical applications. Curr Pharm Des. 2007;13:793–800. doi: 10.2174/138161207780363086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Reynolds EC, Cai F, Shen P, et al. Retention in plaque and remineralization of enamel lesions by various forms of calcium in a mouthrinse or sugar-free chewing gum. J Dent Res. 2003;82:206–211. doi: 10.1177/154405910308200311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Reynolds EC. Remineralization of enamel subsurface lesions by casein phosphopeptide-stabilized calcium phosphate solutions. J Dent Res. 1997;76:1587–1595. doi: 10.1177/00220345970760091101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rahiotis C, Vougiouklakis G. Effect of a CPP-ACP agent on the demineralization and remineralization of dentine in vitro. J Dent. 2007;35:695–698. doi: 10.1016/j.jdent.2007.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pitts NB. Are we ready to move from operative to non-operative/preventive treatment of dental caries in clinical practice? Caries Res. 2004;38:294–304. doi: 10.1159/000077769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Paris S, Meyer-Lueckel H. Inhibition of caries progression by resin infiltration in situ. Caries Res. 2010;44:47–54. doi: 10.1159/000275917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Griffin SO, Oong E, Kohn W, et al. The effectiveness of sealants in managing caries lesions. J Dent Res. 2008;87:169–174. doi: 10.1177/154405910808700211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Meyer-Lueckel H, Paris S. Progression of artificial enamel caries lesions after infiltration with experimental light curing resins. Caries Res. 2008;42:117–124. doi: 10.1159/000118631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Martignon S, Ekstrand KR, Ericson MD. Efficacy of sealing proximal early active lesions: an 18-month clinical study evaluated by conventional and subtraction radiography. Caries Res. 2006;40:382–388. doi: 10.1159/000094282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ekstrand KR, Bakhshandeh A, Martignon S. Treatment of proximal superficial caries lesions on primary molar teeth with resin infiltration and fluoride varnish versus fluoride varnish only: efficacy after 1 year. Caries Res. 2010;44:41–46. doi: 10.1159/000275573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Paris S, Meyer-Lueckel H, Kielbassa AM. Resin infiltration of natural caries lesions. J Dent Res. 2007;86:662–666. doi: 10.1177/154405910708600715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Imazato S, Ehara A, Torii M, et al. Antibacterial activity of dentine primer containing MDPB after curing. J Dent. 1998;26:267–271. doi: 10.1016/s0300-5712(97)00013-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Imazato S. Antibacterial properties of resin composites and dentin bonding systems. Dent Mater. 2003;19:449–457. doi: 10.1016/s0109-5641(02)00102-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Imazato S, Kinomoto Y, Tarumi H, et al. Antibacterial activity and bonding characteristics of an adhesive resin containing antibacterial monomer MDPB. Dent Mater. 2003;19:313–319. doi: 10.1016/s0109-5641(02)00060-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.O’Hehir T E. Ozone and caries. Periodontics. 2003;23:45–60. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bocci V, Borrelli E, Travagli V, et al. The ozone paradox: ozone is a strong oxidant as well as a medical drug. Med Res Rev. 2009;29:646–682. doi: 10.1002/med.20150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Baysan A, Whiley RA, Lynch E. Antimicrobial effect of a novel ozone-generating device on micro-organisms associated with primary root caries lesions in vitro. Caries Res. 2000;34:498–501. doi: 10.1159/000016630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ploydorou O, Pelz K, Hahn P. Antibacterial effect of an ozone device and its comparison with two dentin-bonding systems. Eur J Oral Sci. 2006;114:349–353. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0722.2006.00363.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hintze H, Wenzel A, Danielsen B, et al. Reliability of visual examination, fibre-optic transillumination, and bite-wing radiography, and reproducibility of direct visual examination following tooth seperation for the identification of cavitated caries lesions in containing approximal surfaces. Caries Res. 1998;32:204–209. doi: 10.1159/000016454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kielbassa A M, Paris S, Lussi A, et al. Evaluation of cavitations in proximal caries lesions at various magnification levels in vitro. J Dent. 2006;34:817–822. doi: 10.1016/j.jdent.2006.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hintze H, Wenzel A, Danielsen B. Behaviour of approximal carious lesions assessed by clinical examination after tooth separation and radiography: a 2.5-year longitudinal study in young adults. Caries Res. 1999;33:415–422. doi: 10.1159/000016545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ratledge DK, Kidd EAM, Beighton D. A clinical and microbiological study of approximal carious lesions. Caries Res. 2001;35:3–7. doi: 10.1159/000047423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ekstrand KR, Ricketts DNJ, Kidd EAM, et al. Detection, diagnosing, monitoring and logical treatment of occlusal caries in relation to lesion activity and severity: an in vivo examination with histological validation. Caries Res. 1998;32:247–254. doi: 10.1159/000016460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Stenlund H, Majàre I, Källestål C. Caries rates related to approximal caries at ages 11–13: a 10-year follow-up study in Sweden. J Dent Res. 2002;81:455–458. doi: 10.1177/154405910208100704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gündüz K, Çelenk P. Çürük Tanısında Kullanılan Yeni Yöntemler. Cumhuriyet Dent J. 2003;6:43–49. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sheehy EC, Brailsford SR, Kidd EAM, et al. Comparison between visual examination and a laser fluorescence system for in vivo diagnosis of occlusal caries. Caries Res. 2001;35:421–426. doi: 10.1159/000047485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wenzel A. Bitewing and digital bitewing radiography for detection of caries lesions. J Dent Res. 2004;83(Spec Iss C):72–74. doi: 10.1177/154405910408301s14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Arrow P. Incidence and progression of approximal carious lesions among school children in Western Australia. Aust Dent J. 2007;52:216–226. doi: 10.1111/j.1834-7819.2007.tb00492.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mejàre I, Källestål C, Stenlund H. Incidence and progression of approximal caries from 11 to 22 years of age in Sweden: a prospective radiographic study. Caries Res. 1998;33:93–100. doi: 10.1159/000016502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pretty IA. Caries detection and diagnosis: novel technologies. J Dent. 2006;34:727–739. doi: 10.1016/j.jdent.2006.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lussi A, Megert B, Lonbbottom C, et al. Clinical performance of a laser fluorescence device for detection of occlusal caries lesions. Eur J Oral Sci. 2001;109:14–19. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0722.2001.109001014.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bader JD, Shugars DA, Bonito AJ. A systematic review of selected caries prevention and management methods. Commun Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2001;29:399–411. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0528.2001.290601.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Farrow ML, Newman SM, Oesterle LJ, et al. Filled and unfilled restorative materials to reduce enamel decalcification during fixed-appliance orthodontic treatment. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2007;132:e1–e6. doi: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2007.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Estrela C, Estrela CRA, Decurcio DA, et al. Antimicrobial potential of ozone in an ultrasonic cleaning system against Staphylococcus aureus. Braz Dent J. 2006;17:134–138. doi: 10.1590/s0103-64402006000200010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Huth KC, Saugel B, Jakob FM, et al. Effect of aqueous ozone on the NF-[kappa]B system. J Dent Res. 2007;86:451–456. doi: 10.1177/154405910708600512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Holmes J. Clinical reversal of root caries using ozone, double-blind, randomised, controlled 18-month trial. Gerodontology. 2003;20:114. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-2358.2003.00106.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Baysan A, Lynch E. Effect of ozone on the oral microbiota and clinical severity of primary root caries. Am J Dent. 2004;17:56–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zaura E, Buijs MJ, ten Cate JM. Effects of ozone and sodium hypochlorite on caries-like lesions in dentin. Caries Res. 2007;41:489–492. doi: 10.1159/000109086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Imazato S, Torii Y, Takatsuka T, et al. Bactericidal effect of dentin primer containing antibacterial monomer methacryloyloxydodecylpyridinium bromide (MDPB) against bacteria in human carious dentin. J Oral Rehabil. 2001;28:314–319. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2842.2001.00659.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Paris S, Meyer-Lueckel H. Infiltrants inhibit progression of natural caries lesions in vitro. J Dent Res. 2010;89:1276–1280. doi: 10.1177/0022034510376040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zantner C, Martus P, Kielbassa AM. Clinical monitoring of the effect of fluorides on long-existing white spot lesions. Acta Odontol Scand. 2006;64:115–122. doi: 10.1080/00016350500443297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Truin G-J, van’t Hof M. The effect of fluoride gel on incipient carious lesions in a low-caries child population. Commun Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2007;35:250–254. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0528.2007.00333.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Newbrun E. 3rd ed. Quintessence Publishing Co; Chicago, IL: 1989. Cariology. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lagerweij MD, Buchalla W, Kohnke S, et al. Prevention of erosion and abrasion by a high fluoride concentration gel applied at high frequencies. Caries Res. 2006;40:148–153. doi: 10.1159/000091062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Alttenburger MJ, Schirrmeister JF, Wrbas KT, et al. Fluoride uptake and remineralisation of enamel lesions after weekly application of differently concentrated fluoride gels. Caries Res. 2008;42:312–318. doi: 10.1159/000148164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Attin T, Lennon MA, Yakin M, et al. Deposition of fluoride on enamel surfaces released from varnishes is limited to vicinity of fluoridation site. Clin Oral Invest. 2007;11:83–88. doi: 10.1007/s00784-006-0080-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Reynolds EC, Cain CJ, Webber EL, et al. Anticariogenicity of calcium phosphate complexes of tryptic casein phosphopeptides in the rat. J Dent Res. 1995;74:1272–1279. doi: 10.1177/00220345950740060601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Yamaguchi K, Miyazaki M, Takamizawa T, et al. Effect of CPP-ACP paste on mechanical properties of bovine enamel as determined by an ultrasonic device. J Dent. 2006;34:230–236. doi: 10.1016/j.jdent.2005.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Oshiro M, Yamaguchi K, Takamizawa T, et al. Effect of CPP-ACP paste on tooth mineralization: an FE-SEM study. J Oral Sci. 2007;49:115–120. doi: 10.2334/josnusd.49.115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Shen P, Cai F, Nowicki A, et al. Remineralization of enamel subsurface lesions by sugar-free chewing gum containing casein phosphopeptide–amorphous calcium phosphate. J Dent Res. 2001;80:2066–2070. doi: 10.1177/00220345010800120801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Rosen S, Min DB, Harper DS, et al. Effect of cheese with and without sucrose on dental caries and recovery of Streptococcus mutans in rats. J Dent Res. 1984;63:894–896. doi: 10.1177/00220345840630061601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Reynolds EC, Johnson IH. Effect of milk on caries incidence and bacterial composition of dental plaque in the rat. Arch Oral Biol. 1981;26:445–451. doi: 10.1016/0003-9969(81)90042-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Harper DS, Osborn JC, Hefferren JJ, et al. Cariostatic evaluation of cheeses with diverse physical and compositional characteristics. Caries Res. 1986;20:123–130. doi: 10.1159/000260931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Walker GD, Cai F, Shen P, et al. Increased remineralization of tooth enamel by milk containing added casein phosphopeptide-amorphous calcium phosphate. J Dairy Res. 2006;73:74–78. doi: 10.1017/S0022029905001482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Reynolds EC, Cai F, Cochrane NJ, et al. Fluoride and casein phosphopeptide-amorphous calcium phosphate. J Dent Res. 2008;87:344–348. doi: 10.1177/154405910808700420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Cochrane NJ, Saranathan S, Cai F, et al. Enamel subsurface lesion remineralization with casein phosphopeptide stabilized solutions of calcium, phosphate and fluoride. Caries Res. 2008;42:88–97. doi: 10.1159/000113161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.David Hay K, Thomson WM. A clinical trial of the anticaries efficacy of casein derivatives complexed with calcium phosphate in patients with salivary gland dysfunction. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2002;93:271–275. doi: 10.1067/moe.2002.120521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.ten Cate JM. Review on fluoride, with special emphasis on calcium fluoride mechanisms in caries prevention. Eur J Oral Sci. 1997;105:461–465. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0722.1997.tb00231.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]