Abstract

Using a panel data set (n = 49,626), this research tests opposing hypotheses about the influence of brand personality dimensions (BPDs) on customer-based brand equity (CBBE) and the evolution of this influence over an 18-year period. The results show that, on average, the BPDs of excitement, competence, and sincerity have more positive effects on CBBE than sophistication and ruggedness. Furthermore, the effects of sincerity, sophistication, and ruggedness on CBBE have declined over time while the effects of excitement and competence have grown more positive: A 1% change in excitement is associated with a .45% change in CBBE in 2001 and a .71% change in 2018 (a 58% increase), while a 1% change in competence is associated with a .42% change in CBBE in 2001 and a .60% change in 2018 (a 43% increase). How these effects vary between countries, industry sectors, and brand types is also explored.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s11747-022-00895-2.

Keywords: Brand personality, Customer-based brand equity, Panel data

Introduction

A clear prediction emerges from the brand personality (BP) literature: A strong and appealing BP can improve customer responses to marketing activities and, thus, brand equity (for reviews and meta-analyses, see Eisend & Stokburger-Sauer, 2013a, 2013b; MacInnis & Folkes, 2017; Radler, 2018). Beyond this broad assertion, the influence of specific brand personality dimensions (BPDs; i.e., excitement, competence, sincerity, sophistication, and ruggedness; Aaker, 1997) on customer-based brand equity (CBBE)1 and its outcomes (e.g., brand choice) remains somewhat unclear for at least two reasons.

First, most BP studies, which are experiments or surveys, concentrate on examining the effects of one BPD and overlook the other dimensions that constitute the whole personality of a given brand. Perhaps this occurs because these studies tend to assume that a brand’s personality profile is typically characterized by a high score on a single BPD. This also possibly occurs for methodological reasons. Specifically, these studies almost systematically investigate BPD effects using as stimuli a brand that ranks high on a given BPD and a comparable brand that ranks low on that same BPD, while disregarding how these brands rank on the other four BPDs. As such, most BP studies do not detail how different BPDs might exert unique effects on customer responses. Therefore, despite unambiguous evidence of the positive impacts of BPDs on customer responses, knowledge about which BPDs contribute more or less to CBBE is incomplete. This is an important gap in the literature, because if the effects of BPDs differ, it would indicate that different BPDs can operate in diverse ways and influence customers through diverse routes. In that case, treating BPDs as equivalent contributors to CBBE could result in imprecise theories and ill-advised branding decisions. To the best of our knowledge, Eisend and Stokburger-Sauer’s meta-analyses (2013a, 2013b) offer the only comprehensive evidence to date of the differential effects of the five BPDs. Briefly, they found that the BPDs of competence and sincerity tended to have the most positive impact on brand attitude, whereas the BPDs of ruggedness and excitement tended to have the least positive impact. Our study complements theirs because, unlike most studies in the BP literature and thus included in these meta-analyses, our analysis simultaneously considers the effect of all five BPDs and does not assume that a brand’s personality profile is typically characterized by a high score on a single BPD. Furthermore, our study is based on a sizable sample of actual brands and panel data.

The second reason that the influence of specific BPDs on CBBE and its outcomes remains somewhat unclear is that, perhaps due to the challenges associated with obtaining longitudinal data on BP, prior work almost systematically relies on cross-sectional evidence to understand the effects of BPDs. Therefore, dynamic notions of time have been virtually absent from this literature and research cannot precisely predict whether, why, and how the effects of BPDs might change over time. Yet, time is a fundamental management construct, and customer responses to marketing actions are inherently dynamic (Zhang & Chang, 2021). Understanding how the BP–CBBE link has evolved is thus essential to the development of more informative BP frameworks, more relevant practical insights, and a better grasp of the results of previous BP studies. To our knowledge, only Aaker et al. (2004) have investigated changes in BPD effects over time, showing that the effects of the BPDs of sincerity and excitement can evolve over a 58-day period at the customer level, depending on whether customers observe brands commit acts of transgression. Our study complements theirs because it documents the evolution of the effects of all five BPDs at the brand level and over a longer time period and suggests a mechanism other than the observation of transgressions to explain changes in BPD effects over time.

The main goal of this study is to help address these two research gaps and thereby enhance both scholars’ and practitioners’ understanding of which BPDs have relatively more positive effects on CBBE, how the effect of each BPD evolves over time, and what factors might explain these effects and their evolution. Accordingly, we build on prior research on BP and human personality, as well as evidence of the changing values and personality profile of the population, to derive alternative predictions about the relative effects of BPDs on CBBE and their evolution at the population level over time. We offer alternative hypotheses because prior related research points in opposite directions. Thus, building on this research leads to competing predictions.

We test the alternative hypotheses we propose using a proprietary panel data set, comprising 49,626 brand-year observations over the period 2001–2018 for 6,858 unique brands. Our analyses reveal that each BPD tends to have a positive effect on CBBE. However, excitement, competence, and sincerity tend to be more influential than sophistication and ruggedness. We also find that the effects of the BPDs of excitement and competence on CBBE exhibit increasingly positive trends over the 18-year period of our data. Conversely, the effects of the other three BPDs exhibit declining trends. To supplement these findings and offer evidence of their generalizability, we report a series of exploratory analyses. These analyses suggest that the relative effects of BPDs on CBBE are fairly comparable, both in the United States (U.S.) and Japan, as well as across several industry sectors, although we observe intersectoral differences. Furthermore, the evolution of the effects of BPDs on brands’ financial performance over time follows a pattern somewhat consistent with the evolution of their effects on CBBE. We discuss the main contributions, implications, and limitations of our findings in the “Discussion” section.

Theoretical background

CBBE and BP constructs

Building equity is an important strategic issue for brands. As a fundamental branding construct, CBBE has received substantial attention from both scholars and practitioners (for discussions, see Keller, 1993; Keller & Lehmann, 2006). A brand possesses higher (lower) CBBE if customers respond more (less) favorably to its marketing activities than they do to the same activities performed by another brand (Keller, 1993). For example, Disney enjoys relatively high CBBE because customers think and feel more positively about Disney’s ads, recall its logo more easily, and find its theme parks more distinctive compared with similar ads, logos, or theme parks belonging to other brands.

Brands invest substantial effort and resources into building a BP that resonates with customers. As such, considerable research attention has been devoted to the BP construct (Brasel & Hagtvedt, 2016; Chun & Davies, 2006; Freling et al., 2011; Labrecque & Milne, 2012; Malär et al., 2012; Venable et al., 2005; Wentzel, 2009), which refers to the collection of human-like traits that customers ascribe to brands (Aaker, 1997). In fact, our literature search yielded 358 peer-reviewed articles on this construct.2 According to prior research, BP largely determines the effects of marketing activities on customer responses (Keller, 1993). Continuing with our illustration, customers might feel more positively about Disney’s ads, because they perceive Disney as friendlier than other brands, and they identify with this BP. As prior work has frequently corroborated, a strong and appealing BP can positively influence customer behavior (Eisend & Stokburger-Sauer, 2013a, 2013b; MacInnis & Folkes, 2017; Radler, 2018). For example, such a BP can increase brand evaluations, brand name recall (Freling & Forbes, 2005), customer satisfaction, loyalty (Brakus et al., 2009), willingness to buy (Aaker et al., 2010, 2012; Bennett & Hill, 2012; Freling et al., 2011), and CBBE (Lieven et al., 2014; Luffarelli et al., 2019; Magnusson et al., 2019; Sirianni et al., 2013). According to extant findings, BP influences CBBE and its manifestations because the personalities exhibited by brands offer symbolic, identity-expressive, self-enhancing, and self-building benefits to customers (Aaker, 1997; Aaker et al., 2004; Aguirre-Rodriguez et al., 2012; Keller, 1993; MacInnis & Folkes, 2017; Maehle et al., 2011; Malär et al., 2011).

BPDs and human personality profile and values

To conceptualize and operationalize BP for this research, we follow Aaker (1997), whose framework has received considerable support and has been cited more than 13,300 times.3 The theoretical foundation for her framework rests on research into human personality traits, specifically the Big Five dimensions of human personality. This widely accepted taxonomy describes five universal, dimensional features of human personality: extraversion, conscientiousness, agreeableness, neuroticism, and openness to experience (Goldberg, 1990; McCrae & Costa, 1997). Using this taxonomy as a basis, Aaker’s framework classifies the human-like traits that customers ascribe to brands according to five dimensions: excitement, competence, sincerity, sophistication, and ruggedness.4 This operationalization of BPDs combines both brand-specific scale items and items from validated human personality inventories. Thus, some BPDs closely correspond to the Big Five dimensions of human personality; however, others do not. More precisely, excitement, competence, and sincerity mirror the human personality dimensions of extraversion, conscientiousness, and agreeableness, respectively (Aaker et al., 2001). “Agreeableness and Sincerity both capture the idea of warmth and acceptance; Extroversion and Excitement both connote the notions of sociability, energy, and activity; Conscientiousness and Competence both encapsulate responsibility, dependability, and security” (Aaker, 1997, p. 353). Therefore, these three BPDs tend to reflect customers’ actual selves (Aaker, 1997; Aaker et al., 2001).

In contrast, sophistication and ruggedness do not closely correspond to any Big Five dimensions of human personality (ibid.). They correspond to motivational goals central to an institutionalized, dominant cultural value—a shared idea about what is ideal, desirable, and aspirational—in the U.S.: power (Schwartz, 1999; Schwartz & Bardi, 2001; Shepherd et al., 2015). Power values represent goals such as attaining social status, influence, prestige, wealth, authority, and dominance (ibid.). Previous research has linked the BPD of sophistication to customers’ aspiration to status, prestige, and wealth (Aaker, 1997; Aaker et al., 2001). The BPD of ruggedness reflects ideals of strength, toughness, and masculinity (ibid.), which resonate with power-related values, such as a desire for status, social power, authority, and dominance (Batra et al., 2017). Thus, these two BPDs tend to reflect ideal or aspirational selves (Aaker, 1997; Aaker et al., 2001).

Congruities between BP and customers’ selves

Customers find brands more valuable, relevant, and meaningful when they can identify more and stronger (vs. less and weaker) congruities between their actual and ideal selves and the personalities of brands (MacInnis & Folkes, 2017; Malär et al., 2011; Schmitt, 2012; Shepherd et al., 2015; Stokburger-Sauer et al., 2012). Despite clear evidence that congruities between customers’ selves and brands’ personalities result in favorable outcomes for brands, whether congruities with the actual or ideal self result in more positive effects is less clear (Radler, 2018). Some studies demonstrate that congruities with customers’ actual selves result in more favorable outcomes (Astakhova et al., 2017; Huber et al., 2018; Japutra et al., 2019; Malär et al., 2011). Conversely, other studies find that congruities with customers’ aspirational selves can have more positive effects for brands (Aguirre-Rodriguez et al., 2012; Ekinci et al., 2008; Helgeson & Supphellen, 2004; Hosany & Martin, 2012).

Hypothesis development

We build on this theoretical background to develop opposing hypotheses about which BPDs have relatively more positive effects on CBBE. We develop these alternative predictions because extant findings leave open the possibility that congruities between BP and either customers’ actual or ideal selves result in more favorable outcomes. We also develop opposing hypotheses about the evolution of the effects of BPDs over time because mixed evidence leaves open the possibility that the prevalence of the Big Five dimensions, personality traits, and values that BPDs mirror have either increased or decreased at the population level.

Relative effects of BPDs

Consistent with the self-brand congruence literature, we expect that correspondences and dissimilarities between the five BPDs and customers’ actual selves versus aspirational selves have implications for the relative effects of BPDs on CBBE. If congruities between customers’ actual selves and BP result in more favorable outcomes for brands, the BPDs of excitement, competence, and sincerity might, on average, have more positive effects on CBBE than the BPDs of sophistication and ruggedness because, as discussed previously, these three BPDs more strongly reflect customers’ actual selves. Conversely, if congruities between customers’ ideal selves and BP result in more favorable outcomes for brands, the BPDs of sophistication and ruggedness might, on average, have more positive effects on CBBE than the other three BPDs because, as discussed earlier, they more strongly reflect customers’ ideal selves.

H1.1

The BPD of excitement has a more positive effect on CBBE than (a) the BPD of sophistication and (b) the BPD of ruggedness.

H1.2

The BPD of excitement has a less positive effect on CBBE than (a) the BPD of sophistication and (b) the BPD of ruggedness.

H2.1

The BPD of competence has a more positive effect on CBBE than (a) the BPD of sophistication and (b) the BPD of ruggedness.

H2.2

The BPD of competence has a less positive effect on CBBE than (a) the BPD of sophistication and (b) the BPD of ruggedness.

H3.1

The BPD of sincerity has a more positive effect on CBBE than (a) the BPD of sophistication and (b) the BPD of ruggedness.

H3.2

The BPD of sincerity has a less positive effect on CBBE than (a) the BPD of sophistication and (b) the BPD of ruggedness.

Evolution of the effects of excitement and competence

Research indicates that the prevalence of the Big Five dimensions and their associated personality traits and values have been changing at the population level over time (Billstedt et al., 2013; Greenfield, 2013; Jokela et al., 2017; Mroczek & Spiro, 2003; Smits et al., 2011; Terracciano et al., 2005; Twenge, 2001). These changes largely reflect variations in the proportional representation of various generational cohorts in the population, which tend to exhibit different Big Five profiles, personality traits, and values. Generational cohorts tend to have disparate values and personality profiles because of macro-environmental shifts that affect the upbringing and character of cohort members (Greenfield, 2013; Smits et al., 2011; Twenge, 2001, 2014). For example, millennials (born in the 1980s–1990s), who now account for a substantial percentage of the population, rank higher on extraversion than previous generational cohorts (Smits et al., 2011; Twenge, 2001), possibly raising the average level of extraversion in the population.

Changes in the personality profile of the population are likely to have implications for the effects of BPDs on CBBE. We expect that, as the personality profile of the population changes, the effects of the three BPDs that align more closely with the Big Five dimensions of human personality also evolve systematically over time. More specifically, as the personality profile of the population changes, the three BPDs that more closely mirror the Big Five dimensions of human personality—excitement, competence, and sincerity—should undergo an evolution of their level of congruence with customers’ actual selves. In turn, the effects of these three BPDs on CBBE should evolve because, as the literature discussed previously illustrates, congruities between customers’ actual selves and the personality of a brand influence the relationship between BP and CBBE. We discuss the ways in which the Big Five personality profile of the population might have changed and the implications that these changes can have for the BP–CBBE relationship in the following paragraphs.

Most studies indicate that, in the recent past, extraversion, conscientiousness, and their associated personality traits and values have become more prevalent at the population level due to economic and socio-cultural changes (Billstedt et al., 2013; Jokela et al., 2017; Mroczek & Spiro, 2003; Smits et al., 2011; Terracciano et al., 2005; Twenge, 2001). For example, as the economy has become more service oriented, the ability to communicate has grown more important. Consequently, extraversion in the population might have increased (Twenge, 2001). With the arrival of more entrepreneurial firms, self-employed persons, and gig workers, the importance of being self-directed, efficacious, self-reliant, and autonomous has also risen (Ravenelle, 2019; Vecchio, 2003), likely raising the average level of conscientiousness in the population. These findings offer evidence for the heightened prevalence of extraversion and conscientiousness at the population level. However, a few studies find modest decreases in extraversion and conscientiousness in younger generational cohorts (Eastman et al., 2021; Lissitsa and Kol, 2021), suggesting that the prevalence of these two dimensions of human personality in the population might have diminished.

Because the prevalence of the Big Five dimensions of extraversion and conscientiousness at the population level has either increased or decreased and recalling that the BPDs of excitement and competence mirror extraversion and conscientiousness, respectively, we anticipate that the proportion of customers who sense stronger connections between their actual selves and these two BPDs has evolved over time. Thus, we propose that the positive impacts of the BPDs of excitement and competence on CBBE have also changed over time.

H4.1

The effect of the BPD of excitement on CBBE has increased over time.

H4.2

The effect of the BPD of excitement on CBBE has decreased over time.

H5.1

The effect of the BPD of competence on CBBE has increased over time.

H5.2

The effect of the BPD of competence on CBBE has decreased over time.

Evolution of the effect of sincerity

In seeking to derive predictions about the BPD of sincerity, we also find mixed results regarding changes in the prevalence of agreeableness at the population level. Several studies find modest increases in agreeableness over time (Roberts et al., 2006; Smits et al., 2011; Terracciano et al., 2005), suggesting this personality trait might have become more prevalent at the population level. Furthermore, research observes greater concern for the environment and sustainable behaviors (Diprose et al., 2019; White et al., 2019) and that agreeableness is positively associated with such concern and behaviors (Hirsh, 2010; Hopwood et al. 2021). Studies also demonstrate that agreeableness predicts engagement with social justice ideas (Butrus & Witenberg, 2013; Malti & Buchmann, 2010) and that support for social justice has ameliorated (Stroebe et al., 2015). This evidence suggests that agreeableness has become more prevalent at the population level. In contrast, other studies document important decreases in agreeableness or personality traits and behaviors typically associated with agreeableness (Campbell & Twenge, 2015; Eastman et al., 2021; Konrath et al., 2011; Twenge et al., 2012). Social and intrinsic values (e.g., making friends, helping others) and concern for others (e.g., empathy, desire to volunteer) have declined over time (Konrath et al., 2011; Twenge et al., 2012). Because people who score high on agreeableness display greater concern for others, altruism, and prosocial behaviors (Graziano & Eisenberg, 1997), the prevalence of agreeableness might have been diminishing. Furthermore, extant research indicates a decline in collectivistic values (Greenfield, 2013; Twenge, 2014) and that agreeableness positively relates to collectivism (Benet-Martinez and Karakitapoglu-Aygün, 2003). Other studies document that narcissism negatively correlates with agreeableness (Paulhus & Williams, 2002) and that narcissism has increased (Twenge, 2013; Twenge & Campbell, 2008). This evidence points to a decrease in agreeableness in the population.

Because the prevalence of the Big Five dimension of agreeableness has either increased or decreased and recalling that the BPD of sincerity mirrors agreeableness, we anticipate that the proportion of customers who sense more and stronger congruities between their actual selves and this BPD has evolved over time. Correspondingly, we propose that the positive impact of the BPD of sincerity on CBBE has also changed over time.

H6.1

The effect of the BPD of sincerity on CBBE has increased over time.

H6.2

The effect of the BPD of sincerity on CBBE has decreased over time.

Evolution of the effects of sophistication and ruggedness

As we explained previously, the BPDs of sophistication and ruggedness do not share close connections with the Big Five dimensions of human personality but reflect ideal or aspirational selves shaped by institutionalized cultural values (Aaker, 1997; Aaker et al., 2001). Accordingly, changes in the Big Five profile of the population are unlikely to have implications for the evolution of the effects of the BPDs of sophistication and ruggedness on CBBE. Instead, we expect that, as the prevalence of power values like social status, influence, prestige, wealth, authority, and dominance evolve, the effects of the two BPDs that align more closely with these cultural values also evolve systematically over time. More specifically, as the prevalence of these cultural values changes over time, the proportion of customers who sense more and stronger congruities between their ideal or aspirational selves and the BPDs of sophistication and ruggedness should change. In turn, the effects of these two BPDs on CBBE should evolve because congruities between customers’ ideal selves and the personality of a brand influence the positivity of the relationship between BP and CBBE.

Several studies have found that younger generations tend to place considerably more importance on power values, such as achieving social influence, wealth, and status, than older generations (Lyons et al., 2007; Twenge, 2010), likely raising the importance of power as a cultural value in the population. Furthermore, due to the 2008 global financial crisis, the predominance of power values increased in countries with lower welfare spending (Sortheix et al., 2019), which is the case for the U.S. Conversely, some research has found that younger generational cohorts are less motivated by opportunities to exercise power than older cohorts (Wong et al., 2008), likely lessening the significance of power as a cultural value in the population. Because evidence for changes in the prevalence of power values is mixed, we ascertain two possibilities concerning the evolution of the effects of the BPDs of sophistication and ruggedness on CBBE. The first possibility is that these effects have become more positive over time, because power values have become more important in the population. The second possibility is that these effects have declined because power values have become less important.

H7.1

The effect of the BPD of sophistication on CBBE has increased over time.

H7.2

The effect of the BPD of sophistication on CBBE has decreased over time.

H8.1

The effect of the BPD of ruggedness on CBBE has increased over time.

H8.2

The effect of the BPD of ruggedness on CBBE has decreased over time.

Methodology

Data and sample

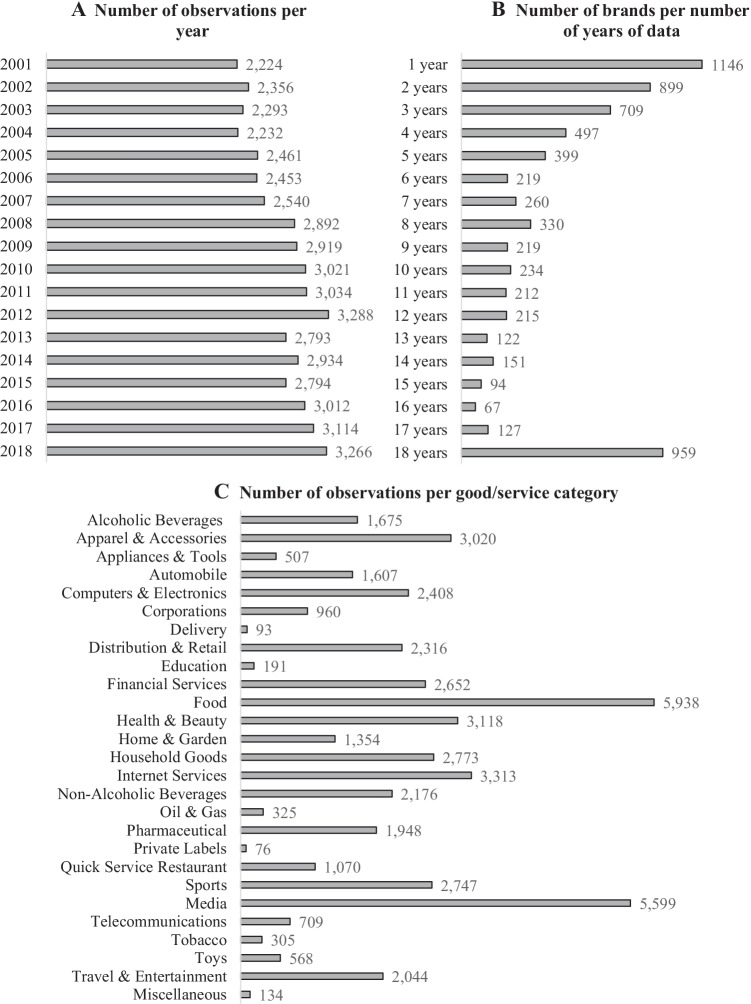

We use a proprietary, unbalanced panel data set obtained from the BrandAsset® Valuator (BAV) consulting group—a global strategic consultancy with branding expertise—to test our opposing hypotheses. The BAV group compiles this data set from a survey administered to a large, rotating sample of more than 10,000 customers representative of the U.S. population. It provided brand-level, annual data about customers’ perceptions of U.S. and non-U.S. brands available in the U.S.5 Our sample contains 49,626 brand-year observations over the period 2001–2018 for 6,858 unique brands in twenty-seven categories of goods and services defined by the BAV group. Figure 1 offers further information about the sample and lists these categories of goods and services.

Fig. 1.

Sample description

Variables

CBBE

Our dependent variable (CBBEit) is the well-known BAV measure.6 This measure is largely considered a valid and comprehensive measure of CBBE and has often been used in marketing studies (Batra et al., 2017; Heitmann et al., 2020; Lovett et al., 2013; Luffarelli et al., 2019; Stahl et al., 2012). Higher BAV scores indicate higher levels of CBBE.

Time

We capture the effect of time for the period 2001–2018 using indicator variables for each year t (Yeart).

BPDs

The BAV group asks respondents to indicate, on binary scales, whether they associate a brand with specific BP traits (e.g., “friendly;” 0 = “no,” 1 = “yes”). Subsequently, it aggregates these binary ratings across respondents to determine the percentage of respondents who believe a brand possesses a given trait. Our data set does not contain binary ratings at the individual respondent level but contains percentage scores at the brand level. Hence, we conducted our analyses at the brand level. For example, in our data set, a score of 12.85 for brand i in year t for the trait “friendly” indicates that 12.85% of the respondents surveyed in year t perceived brand i as friendly. For each brand i in year t, we create the five BPD measures by averaging the percentages for all the traits available in our data set that correspond to the traits in Aaker’s (1997) BP framework. Specifically, the traits “reliable,” “leader,” and “intelligent” form the measure of competence (Competenceit). The traits “friendly,” “original,” and “down-to-earth” form the measure of sincerity (Sincerityit), and the traits “upper-class,” “charming,” and “glamorous” form the measure of sophistication (Sophisticationit). We use the traits “daring,” “trendy,” “up-to-date,” “independent,” and “unique” to constitute the measure of excitement (Excitementit) if Yeart < 2018. However, if Yeart = 2018, this measure also includes the trait “cool.” We use the traits “rugged” and “tough” to constitute the measure of ruggedness (Ruggednessit) if Yeart ≤ 2005. If Yeart ≥ 2006, this measure only includes the trait “rugged.” These two traits are added or removed because the BAV group did not measure the trait “cool” before 2018 and the trait “tough” after 2005.7 In Web Appendix (WA) 1, we offer evidence that these measures are valid by demonstrating that brands that should rate high or low on a given BPD, according to prior studies, score relatively high or low, respectively, on that dimension in our data set. We also demonstrate that the correlations between our BPD measures and BPD measures collected using Likert scales range from strong to moderate in size.

Control variables

We control for variables that could confound the effects of BPDs on CBBE. We control for the percentage of respondents indicating that a brand i in year t is one of the brands they prefer (Preferenceit), a brand they buy or use at least occasionally (Usageit), a brand that performs well (Performanceit), and a brand whose goods or services are worth more (Valueit). Furthermore, we control for the number of respondents who indicated that they were at least slightly familiar with the brand (Familiarityit). We also include twenty-six indicator variables to control for the good/service category of each brand i (Good/Service Categoryi).

Table 1 provides pairwise correlations and descriptive statistics for the variables defined previously. WA 2 contains a factor analysis of the variables in Table 1. It also includes the correlations and descriptive statistics for the raw, untransformed variables, as well as plots of the yearly means and standard deviations of these variables.

Table 1.

Pairwise correlations and summary and descriptive statistics

| Panel A—Pairwise correlations | ||||||||||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | ||

| 1 | CBBE | |||||||||||

| 2 | Familiarity | .57 | ||||||||||

| 3 | Usage | .69 | .39 | |||||||||

| 4 | Preference | .61 | .36 | .84 | ||||||||

| 5 | Value | .66 | .27 | .43 | .46 | |||||||

| 6 | Performance | .62 | .29 | .26 | .33 | .59 | ||||||

| 7 | Sincerity | .70 | .34 | .63 | .52 | .53 | .26 | |||||

| 8 | Excitement | .25 | .05 | − .01 | .00 | .07 | .18 | .13 | ||||

| 9 | Competence | .66 | .35 | .28 | .32 | .55 | .74 | .44 | .14 | |||

| 10 | Sophistication | .07 | − .02 | − .14 | − .03 | .17 | .11 | − .02 | .54 | .00 | ||

| 11 | Ruggedness | .12 | .00 | .03 | .03 | .12 | .45 | .03 | .13 | .17 | − .07 | |

| Panel B—Summary and descriptive statistics | ||||||||||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | ||

| Minimum | .09 | 3.30 | .00 | .00 | .00 | .00 | 1.48 | 1.09 | 1.09 | .00 | .00 | |

| Mean | 2.44 | 6.67 | 2.64 | 3.15 | 1.93 | 2.25 | 2.68 | 2.23 | 2.52 | 1.90 | 1.89 | |

| Median | 2.41 | 6.81 | 2.80 | 3.25 | 1.92 | 2.22 | 2.66 | 2.22 | 2.52 | 1.85 | 1.78 | |

| Maximum | 5.32 | 10.19 | 4.58 | 4.54 | 3.58 | 3.72 | 3.88 | 3.28 | 3.83 | 3.60 | 3.87 | |

| SD | .85 | .72 | 1.14 | .85 | .45 | .40 | .32 | .25 | .34 | .39 | .50 | |

| VIF | 1.34 | 4.68 | 3.82 | 2.28 | 3.85 | 2.39 | 1.68 | 3.03 | 1.80 | 1.56 | ||

| Tolerance | .75 | .21 | .26 | .44 | .26 | .42 | .59 | .33 | .56 | .64 | ||

| Skewness | .11 | − .50 | − .50 | − 1.73 | .03 | .07 | .19 | .11 | − .02 | .83 | .90 | |

| Correlation(xt, xt-1) | .97 | .79 | .95 | .92 | .86 | .86 | .93 | .88 | .93 | .92 | .90 | |

n = 49,626. All the variables are log(1 + x) transformed. The pairwise correlations are statistically significant at p ≤ .01, except italicized correlations, which are not significant (p > .10). WA 2 contains a factor analysis of the variables in this table. It also includes information about for the raw, untransformed variables

Model formulation

We estimate the models in Eqs. 1 and 2:

| 1 |

| 2 |

where,

- CBBEit

customer-based brand equity of brand i in year t;

- α

intercept;

- Excitementit

rating of the BPD of excitement for brand i in year t;

- Competenceit

rating of the BPD of competence for brand i in year t;

- Sincerityit

rating of the BPD of sincerity for brand i in year t;

- Sophisticationit

rating of the BPD of sophistication for brand i in year t;

- Ruggednessit

rating of the BPD of ruggedness for brand i in year t;

- Yeart

indicator variables for each year t;

- Xit

vector of the following control variables: log(Preferenceit), log(Usageit), log(Performanceit), log(Valueit), log(Familiarityit), and Good/Service Categoryi;

- ηi

fixed effect of brand i;

- εit

error term for brand i in year t;

The coefficients β1–β5 in Eq. 1 denote the effects of BPDs on CBBE. In Eq. 2, the coefficients β1–β5 denote the effects of BPDs when year t equals zero (for the year 2001). The vectors of coefficients Γ2–Γ6 indicate how the effects of BPDs change over time. We use a log–log specification because of the potential ceiling effects with brand equity data. The outcome variable follows a log-normal distribution, and the estimation of a log–log model, in our case, is more efficient than the estimation of a linear–linear or log-linear model (e.g., the root-mean-square error is smaller, and the residuals are more normally distributed). We employ a log(1 + x) transformation to accommodate 0 values and include brand fixed effects to remove the unobserved heterogeneity caused by time-invariant brand characteristics.8 The inclusion of eliminates the risk of bias from unobservable variables that change over time but are constant across brands. Finally, we cluster standard errors at the brand level to account for the unexplained variation in the dependent variable that correlates across time within each brand.

Analyses and results

Descriptive analyses and model-free evidence

The correlations among the control variables and CBBE are statistically significant and range from strong to moderate in size (see Table 1, Panel A), indicating that these variables relate in meaningful ways to CBBE and are appropriate control variables. The correlations in Column 1 also depict that each of the five BPDs positively correlates with CBBE and that the pairwise correlations of CBBE with the BPDs of excitement, competence, and sincerity are stronger than those with sophistication and ruggedness. We also observe that the correlations among the BPDs are small or nearly null. Despite several strong correlations, multicollinearity does not appear to pose a problem for our analyses: The mean variance inflation factor (VIF) for Model 2 in Table 2 is 2.10 (for additional diagnostics, see Table 1, Panel B),9 and the standard errors in all the models we estimate are low. WA 2 includes a more systematic discussion of why multicollinearity is not likely to seriously affect the results reported next.

Table 2.

| (1) | (2) | (3) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Variable name | Controls | BPDs | BPDs × Yeart |

| Familiarity | .064*** | .060*** | .061*** |

| (.004) | (.003) | (.003) | |

| Usage | .252*** | .228*** | .211*** |

| (.015) | (.012) | (.012) | |

| Preference | − .089*** | − .103*** | − .091*** |

| (.014) | (.012) | (.012) | |

| Value | .262*** | .139*** | .122*** |

| (.007) | (.006) | (.006) | |

| Performance | .416*** | .131*** | .131*** |

| (.009) | (.008) | (.008) | |

| Sincerity | .353*** | .418*** | |

| (.015) | (.018) | ||

| Excitement | .460*** | .448*** | |

| (.014) | (.021) | ||

| Competence | .434*** | .423*** | |

| (.015) | (.019) | ||

| Sophistication | .059*** | .092*** | |

| (.010) | (.014) | ||

| Ruggedness | .022*** | .074*** | |

| (.006) | (.009) | ||

| Sincerity × Yeart | Decreased over time | ||

| Excitement × Yeart | Increased over time | ||

| Competence × Yeart | Increased over time | ||

| Sophistication × Yeart | Decreased over time | ||

| Ruggedness × Yeart | Decreased over time | ||

| Constant | .230*** | − 2.009*** | − 2.275*** |

| (.064) | (.067) | (.079) | |

| Year indicators (Yeart) | Included | Included | Included |

| Good/service category indicators | Included | Included | Included |

| Brand fixed effects | Included | Included | Included |

| Within R-squared | .483 | .609 | .627 |

| Between R-squared | .753 | .788 | .759 |

| Overall R-squared | .740 | .798 | .772 |

| Likelihood ratio | 18,692 | 25,613 | 26,810 |

n = 49,626 brand-year observations. The dependent variable is CBBEit. The robust clustered standard errors are in brackets below the coefficients. Model 2 corresponds to Eq. 1 and Model 3 to Eq. 2. In Model 3, the coefficients for the effects of BPDs are the conditional effects of each BPD when Yeart equals zero; that is, the effect of each BPD in 2001. The BPD × Yeart interaction terms in Model 3 are reported in Fig. 2 and WA 3

*** p ≤ .001; ** p ≤ .01; * p ≤ .05; + p ≤ .10

Hypothesis test results

We adopt a stepwise approach and report the results of our analyses in Table 2. In Model 1, we regress CBBE on the control variables. In Model 2, we add the BPD measures (Eq. 1). Subsequently, in Model 3, we add the 85 BPD × Yeart interaction terms (Eq. 2). During 2001–2018, Excitement (β = 0.460, p ≤ 0.001), Competence (β = 0.434, p ≤ 0.001), Sincerity (β = 0.353, p ≤ 0.001), Sophistication (β = 0.059, p ≤ 0.001), and Ruggedness (β = 0.022, p ≤ 0.01) all have positive average effects on CBBE (see Table 2, Model 2). Because we estimate a log–log model, the regression coefficients are elasticities. Thus, the results of this model indicate that an increase of 1% in perceived competence is associated with an approximately 0.434% increase in CBBE.10 A comparison of the R-squared values and likelihood ratios of Models 1 and 2 indicates that the five BPDs have informational value in explaining CBBE and, in particular, within-brand variance in CBBE.

A series of coefficient equality tests on the regression coefficients reported previously reveals that, on average, the BPDs of excitement, competence, and sincerity have more positive effects on CBBE than sophistication and ruggedness. The coefficient for Excitement is not significantly different from that for Competence (F = 1.42, p = 0.23). Nonetheless, both coefficients are significantly greater than the coefficient for Sincerity (Fs > 13.10, ps ≤ 0.001), which is significantly greater than the coefficient for Sophistication (F = 250.97, p ≤ 0.001), which in turn is higher than the coefficient for Ruggedness (F = 10.23, p ≤ 0.001). These results are consistent with H1.1, H2.1, and H3.1 but not H1.2, H2.2, and H3.2.

We find support for H4.1, H5.1, H6.2, H7.2, and H8.2 over H4.2, H5.2, H6.1, H7.1, and H8.1 by examining the BPD × Yeart interaction terms in Model 3. Throughout the study period, the effects of Excitement and Competence on CBBE have grown more positive, while the effects of the other three BPDs have declined. Considering the vast number of interaction terms included in Model 3, Table 2 simply indicates whether the effect of each BPD has increased or decreased significantly over time. Figure 2 depicts the interactions by plotting the changes in the effect of each BPD on CBBE over time at the mean values of the control variables. The parameter estimates for the eighty-five interactions are available in WA 3, and the statistical comparisons for the point estimates in Fig. 2 are available in WA 4.

Fig. 2.

Average marginal effects of BPDs on CBBE over time. Notes. This figure shows changes in the average marginal effect of each BPD over time at the mean values of the control variables, that is, the elasticities of each BPD for each year t. Statistical comparisons for all the point estimates are available in WA 3

Robustness tests

We conduct several tests to confirm the robustness of our findings. The rationale for these tests and detailed results are available in WA 5. We find that our results hold when we (1) trim and winsorize the dependent variable at the 1st and 99th percentiles; (2) employ a measure of Excitementit that does not include the trait “cool” if Yeart = 2018 and a measure of Ruggednessit that does not include the trait “tough” if Yeart ≤ 2005; (3) include the brands that we removed from our sample (see footnote5); (4) select only the brands for which we have 18 uninterrupted years of data; (5) select only the brands that entered the data set before the year 2013 and exclude any brands for which the last observation is for the year 2013; (6) select only brands that rank among the 95%, 85%, and 75% most familiar brands; (7) substitute the 26 Good/Service Categoryi indicator variables for indicator variables that capture 272 good/service subcategories; (8) eliminate any control variables that correlate at least mildly with CBBE or the BPD measures; (9) control for 23 additional brand associations and BP traits recorded in our data set; and (10) use the lag of the BPDs as independent variables.

To allay potential remaining concerns about heteroskedasticity and autocorrelation, we also estimate models with a correction for first-order autocorrelation and models with Driscoll–Kraay standard errors. To assuage potential concerns about the way we account for the effect of time, we estimate models that capture the effect of each year t using either a linear time trend (2001 = 0, 2002 = 1, …, 2018 = 17) or a binary dummy variable (0 = 2001–2009, and 1 = 2010–2018). To offer additional evidence that BPD effects are relatively comparable from one model to another, we estimate nested models that capture the effect of only one BPD at a time as well as nested models that include one BPD after another in a stepwise manner. To provide further evidence that the relatively high correlation between Sincerity and CBBE does not cause instability of the parameter estimates, we estimate a nested model that includes all the BPDs except the BPD of sincerity. Our results hold under these alternative model specifications.

In addition, we conduct a series of Chow tests and Granger non-causality tests. The Chow tests revealed statistically significant structural breaks between selected periods. Thus, they indicate that using indicator variables for each year t to capture the effect of time is more appropriate than using a linear time trend. These breaks are also consistent with the results in Fig. 2 and Table 2 and provide additional support for H4.1, H5.1, H6.2, H7.2, and H8.2. The Granger non-causality tests show that our BPD measures contain information that helps predict CBBE above and beyond the information contained in past values of CBBE.

Exploratory analyses

The preceding results offer insights into the relative effects of BPDs on CBBE at the population level in the U.S., one of the largest consumer markets, and across several industry sectors. Thus, two generalizability questions arise regarding whether the relative effects of BPDs generalize to other countries and whether they differ across good/service categories.

BPD effects in Japan

To help address the first question, we explore the effects of BPDs on CBBE in Japan (for more details, see WA 6) using a cross-sectional data set obtained from the BAV group. This data set features information about 1,187 brands evaluated by Japanese customers in 2010. We find that the BPDs of excitement, competence, and sincerity similarly have more positive effects than sophistication and ruggedness in Japan. Although these preliminary analyses suggest comparable relative effects of BPDs on CBBE in the U.S. and Japan, they must also be considered in light of limitations. First, the data set for Japan is cross-sectional, so we cannot include brand fixed effects to remove unobserved heterogeneity due to time-invariant brand characteristics. For the same reason, we cannot study changes over time. Second, our BPD measures capture the same constructs in the U.S. and Japan because the same method, instrument, and questions were used to collect data in both countries. Furthermore, standard back-translation procedures were employed to create a questionnaire administered in Japan to a sample of customers representative of the Japanese population. However, the structure of BP differs in these two countries. The BPD of ruggedness is replaced by the BPD of peacefulness in Japan, but the other four dimensions are common to both Japan and the U.S. (Aaker et al., 2001). Unfortunately, our data set does not contain any traits captured by the BPD of peacefulness. Therefore, this analysis does not perfectly mirror the structure of BP in Japan.

To help address the second question, we conduct a cluster analysis of elasticity measures for the effect of each BPD on CBBE in different good/service categories (for more details, see WA 7). The data are best described by two clusters: The first includes mostly good/service categories that can be considered “necessities” (e.g., beverages, food, health), while the second includes mostly good/service categories that can be considered “comforts” (e.g., restaurants, computers, electronics). In both clusters, the BPDs of excitement, competence, and sincerity have more positive effects than sophistication and ruggedness. Unrelated to our various predictions, we also find that the average effect of the BPD of competence is less positive in the “necessities” cluster than in the “comforts” cluster, whereas the average effects of the BPDs of excitement and sincerity on CBBE are more positive in the former than in the latter cluster. These findings must also be considered in light of their limitations. We conduct this cluster analysis at the good/service category level, not the brand level, because we do not have a balanced panel data set. This level of analysis unavoidably ignores the potentially relevant dissimilarities among the different classes of brands within these good/service categories. This limitation could explain why not all the categories that can be viewed as “necessities” or “comforts” are included in the first and second clusters, respectively. Alternatively, it is possible that BPD effects for some categories of “necessities” resemble more the BPD effects for some categories of “comforts,” and vice versa. We also recognize that the definition of what constitutes “necessities” and “comforts” may vary and that the clustering solution could have taken another form if we had a greater or lesser number of good/service categories in our data set and if we had data for other categories.

Another generalizability question is whether the evolution of the effects of BPDs on CBBE over time might parallel similar evolutions for other measures of brand equity. To help address this question, we examine the evolution of the effects of BPDs on brand sales. We obtained financial data for 358 of the 6,858 brands in our dataset from Compustat, probably the most comprehensive database of company financial data.11 We find that, over time, the effects of the BPDs of excitement and competence on brand sales have grown more positive, while the effects of sincerity and ruggedness have declined. Although the effect of sophistication has also declined over time, this change fails to reach statistical significance. We find comparable results when we use net income, gross profit, and earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation and amortization as dependent variables in these analyses (for more details, see WA 8). These results are consistent with those reported in Fig. 2 and suggest that the evolutions we document can be observed with other measures of brand equity. These analyses have shortcomings. First, they include relatively few brands because most of the brands in the BAV data set are not listed and hence are not required to publish any financial data. Second, the included brands are fairly distinctive and not representative of the wider population of brands because they are listed. Third, this Compustat sales data capture firms’ global financial performance, not just sales in the U.S. They also capture sales for firms, not brands. For instance, Coca-Cola sales data not only include sales generated by the Coca-Cola brand, but also sales generated by other brands owned by the firm. In our research context, the use of these sales data raises concerns because our BPD measures are gathered among U.S. customers for brands. These limitations could explain why the results of this analysis do not perfectly replicate the findings of the analyses with CBBE as the dependent variable, even if they offer additional evidence that BPDs can influence brand equity and that this influence evolves over time.

Discussion

Our study offers novel insights into the relationship between BP and CBBE by testing opposing predictions derived from extant research. Not only do we show which BPDs are, on average, most valuable in driving CBBE, but we also demonstrate how their effects have evolved over time. Table 3 offers a summary of our hypotheses and findings.

Table 3.

Summary of hypotheses and findings

| Hypotheses | Findings |

|---|---|

| H1.1: The BPD of excitement has a more positive effect on CBBE than (a) the BPD of sophistication and (b) the BPD of ruggedness | Supported |

| H1.2: The BPD of excitement has a less positive effect on CBBE than (a) the BPD of sophistication and (b) the BPD of ruggedness | Not supported |

| H2.1: The BPD of competence has a more positive effect on CBBE than (a) the BPD of sophistication and (b) the BPD of ruggedness | Supported |

| H2.2: The BPD of competence has a less positive effect on CBBE than (a) the BPD of sophistication and (b) the BPD of ruggedness | Not supported |

| H3.1: The BPD of sincerity has a more positive effect on CBBE than (a) the BPD of sophistication and (b) the BPD of ruggedness | Supported |

| H3.2: The BPD of sincerity has a less positive effect on CBBE than (a) the BPD of sophistication and (b) the BPD of ruggedness | Not supported |

| H4.1: The effect of the BPD of excitement on CBBE has increased over time | Supported |

| H4.2: The effect of the BPD of excitement on CBBE has decreased over time | Not supported |

| H5.1: The effect of the BPD of competence on CBBE has increased over time | Supported |

| H5.2: The effect of the BPD of competence on CBBE has decreased over time | Not supported |

| H6.1: The effect of the BPD of sincerity on CBBE has increased over time | Not supported |

| H6.2: The effect of the BPD of sincerity on CBBE has decreased over time | Supported |

| H7.1: The effect of the BPD of sophistication on CBBE has increased over time | Not supported |

| H7.2: The effect of the BPD of sophistication on CBBE has decreased over time | Supported |

| H8.1: The effect of the BPD of ruggedness on CBBE has increased over time | Not supported |

| H8.2: The effect of the BPD of ruggedness on CBBE has decreased over time | Supported |

Implications for the BP literature

The main contribution of our study comes from the evidence that the effects of BPDs are not static but evolve systematically over time and that the dynamic patterns in the BP–CBBE relationship might be empirical regularities. This contribution addresses a persistent gap: Even though time is a fundamental management construct and customer responses to marketing activities are inherently dynamic (Zhang & Chang, 2021), notions of time have been largely absent from BP research, which cannot precisely detail whether, why, or how the effects of BPDs evolve. The basic tenet of our proposed framework is that the effects of BPDs change over time because the prevalence of certain values and personality traits in the population evolve, which affects the proportion of customers who sense stronger congruities between their selves and a given BPD. Even though predicting the future is riddled with uncertainty, the effects we document can be extrapolated to a reasonable period, as long as the values and personality profiles of the population keep evolving in the same direction. Thus, for example, our findings suggest that if the Big Five dimension of extraversion continues to become more prevalent at the population level, the effect of the BPD of excitement should continue to grow more positively. As noted earlier, only Aaker et al. (2004) have investigated changes in BPD effects over time, showing that the effects of the BPDs of sincerity and excitement can evolve over a 58-day period at the customer level, depending on whether customers observe brands commit transgressions. Our results add to their study by documenting the evolution of the effects of all five BPDs at the brand level and over a longer window of time, as well as by suggesting a mechanism other than the observation of transgressions to explain changes in BPD effects over time. Overall, our findings highlight the need to seriously consider time when interpreting the findings of prior BP studies, developing BP frameworks, and making strategic suggestions to practitioners.

A further contribution of our study is to establish that, on average, the BPDs of excitement, competence, and sincerity—which more closely mirror three of the Big Five dimensions of human personality (Aaker, 1997; Aaker et al., 2001)—have more positive effects on CBBE, compared with sophistication and ruggedness. We offer a theoretical account based on self-brand congruity to explain this difference and thereby add to extant knowledge about the symbolic and self-expressive uses that customers make of brands, as well as contribute to the debate on the relative influence of the actual versus ideal self in shaping customer responses to BP. In addition to establishing these insights, our findings complement the available evidence regarding the differential effects of BPDs. Studies have shown that the BPD of competence is often more influential than that of warmth (which includes sincerity; Aaker et al., 2010, 2012; Bennett & Hill, 2012). Our results are consistent with this finding. To the best of our knowledge, Eisend and Stokburger-Sauer’s meta-analyses (2013a, 2013b) offer the only comprehensive evidence to date of the differential effects of the five BPDs in Aaker’s (1997) framework. Our results complement theirs because, unlike most studies in the BP literature and thus included in these meta-analyses, our analysis simultaneously considers the effect of all five BPDs, does not assume that a brand’s personality profile is typically characterized by a high score on a single BPD, and is based on a sizable sample of actual brands and panel data. Therefore, our study adds to the prior literature by providing a complete analysis of the differential effects of BPDs in one large longitudinal study. In line with the results of these meta-analyses, we find that competence and sincerity tend to be two of the most impactful BPDs, whereas ruggedness tends to be the least influential. However, our results are inconsistent with the meta-analytic finding that the BPD of sophistication tends to be more impactful than excitement and is often equally as influential as sincerity. Our results are also inconsistent with the meta-analytic finding that the BPD of excitement tends to be one of the least impactful BPDs. We do not believe that these discrepancies can be attributed to temporal disparities between our study and these meta-analyses, because almost all the articles examined in these meta-analyses were published after the year 2001 (the first year our data set spans). Some unique features of our study mentioned earlier probably explain these discrepancies. Thus, we conclude that employing different methodological approaches can influence BPD effect sizes. We hope that the comparison between our results and those of this meta-analysis will stimulate future research.

We also do not wish to imply that the BPDs of sophistication and ruggedness are unimportant. Our results simply reveal that, on average, across the brands included in our data set, these two BPDs influence CBBE less than the BPDs of excitement, competence, and sincerity. Overall, in revealing how different BPDs can operate in varied ways, with distinct impacts on customer responses, we show that treating BPDs as equally influential threatens to result in imprecise theoretical claims and inaccurate practical recommendations.

Along with these insights, our study offers the most comprehensive support to date for a central thesis of the BP literature, namely, that a strong and appealing BP tends to enhance customer responses. Using a sizable sample of actual brands, our study affirms the external validity of this claim and establishes the positive effects of BPDs on CBBE as an empirical regularity. This is a notable contribution, because a comprehensive empirical analysis of the effects of BPDs on the CBBE of actual brands was missing in the BP literature. In addition, the external validity of BP research had yet to be clearly established, so our results help allay some of the concerns about the theoretical relevance and practical value of the BP construct (for a discussion, see Radler, 2018).

Finally, the exploratory analyses demonstrate that the relative effects of BPDs on CBBE are fairly comparable, both in the U.S. and Japan, as well as across several industry sectors. Besides, they illustrate that the evolution of the effects of BPDs on brands’ financial performance over time follows a pattern largely consistent with the evolution of their effects on CBBE. Although these results require further confirmation, they offer initial evidence of the influence of BPDs in different countries, for different good/service categories, and on brands’ financial performance. These exploratory analyses also indicate that some of our findings can be generalized, to varying degrees, to multiple countries, distinct industry sectors, and outcome variables other than CBBE.

Implications for practitioners

The preceding discussion suggests that practitioners can benefit from fostering strong personalities for their brands. However, beyond this general recommendation, our findings also offer actionable insights and guidelines for crafting a more effective BP. In general, practitioners might seek to cultivate a more exciting or competent BP because these two BPDs generate greater equity on average. The results in Model 3, Table 2 reveal that a 1% increase in the BPD of excitement was associated with about a 0.45% increase in CBBE in 2001 and a 0.71% increase in 2018, reflecting a 58% increase in the effect of this BPD (see Fig. 2 and WA 4). Our results also show that a 1% increase in the BPD of competence is associated with about a 0.42% increase in CBBE in 2001 and a 0.60% increase in 2018, reflecting a 43% change in the effect of this BPD. The magnitudes of these relationships are fairly consistent across the models we estimate. Yet, they vary slightly. Caution is thus needed when considering the sizes of the effects we document.

In general, nurturing a sincere BP also might often be advantageous because it tends to exert a positive effect on CBBE. The results of Model 2, Table 2, show that a 1% change in sincerity is associated with an average increase of about 0.35% in CBBE over 2001–2018. However, the effect of this BPD has become less positive over time and tends to be weaker than the effects of excitement or competence. Moreover, our results show that nurturing a sophisticated or rugged BP is relatively less beneficial, on average, even though their effects on CBBE are more stable than the effects of the other three BPDs. With these insights, practitioners might more accurately anticipate and account for the dynamic nature of BPD effects. Although our results indicate that these insights are likely to apply to multiple countries and industry sectors to varying degrees, we also note a relevant distinction among industry sectors. Practitioners in charge of branding “necessities” might often find that nurturing an exciting or sincere BP is relatively more advantageous than nurturing a competent BP. Practitioners in charge of branding “comfort” goods or services instead might prefer to nurture a competent BP.

Nonetheless, caution is needed when acting on these insights because our results represent average effects. This implies, for example, that even if we find that nurturing a sophisticated BP is relatively less advantageous on average, some brands can greatly benefit from such a BP and might not suffer a decline in its effect, as is the case for luxury brands in our data set.12 This also implies that certain brands might not benefit as much as our findings indicate from cultivating a more exciting, competent, or sincere BP. For example, when their main competitors score high on these BPDs, as such, BP would be less differentiating. For the same reason, certain brands might benefit more from having a sophisticated or rugged personality when their main competitors do not score high on these BPDs. It is also likely that the average effects we document are qualified by the singularity of a brand’s personality profile (singularity is the extent to which a BP is focused on a given BPD rather than on others; Malär et al., 2012). Consistent with the results of Malär et al. (2012), we found in follow-up analyses that brands that score high on a given BPD and low on the other four BPDs have higher CBBE than brands that do not have a strong focus on one BPD.13 This implies that brands might not benefit as much as our findings suggest from fostering a more exciting, competent, or sincere BP when they score high on several BPDs. In contrast, brands might benefit more from having a sophisticated or rugged personality when they score high on one of these BPDs and low on the other four BPDs. These follow-up analyses also reveal that practitioners need not be afraid of watering down customers’ perceptions of all but one BPD, as a strong focus on one BPD leads to higher CBBE. Having a highly singular BP profile appears to be beneficial, regardless of the BPD that scores higher than the others.

Caution is also needed when acting on these insights for the reasons that follow. First, extrapolating our results to the near future seems justified. However, because customer responses to BPDs are dynamic, practitioners must also recognize the constant need for monitoring these responses. Second, our theory suggests that different cohorts of customers can react differently to the same BP. Hence, before implementing recommendations based on our findings, practitioners should clearly understand the values and personality profiles of the customers they target to ensure that the BP they develop resonates with these customers. Third, our study focuses on elucidating how BPDs affect brand equity. Thus, if other outcomes are of interest, practitioners must assess the effects of both the extent and type of BP changes they plan to implement as well as devise strategies to limit any potential negative influences of such changes. A gradual, steady change to the BP may be less likely to result in perceptions of brand inauthenticity than a quick, abrupt BP change, for example.

Limitations and research directions

Our study relies on the framework developed by Aaker (1997), but other notable BP frameworks exist (for examples, see Freling et al., 2011; Grohmann, 2009; Venable et al., 2005). Future work can add to ours by exploring the relative effects of the BPDs in those frameworks and their dynamics over time. For instance, in light of the substantial amount of research that has examined the construct of warmth (Aaker et al., 2010, 2012; Bennett & Hill, 2012), future work could seek to investigate how the influence of this BPD has evolved over time. Because we rely on Aaker’s framework, our investigation focuses on non-negative BP traits, though customers clearly might ascribe negative personality traits to brands. In WA 5, we describe analyses involving two negative BP traits (arrogant and unapproachable), which show that such traits can harm CBBE. However, a more complete analysis of the impact of negative BP traits would add to the extant BP literature. We also acknowledge that it would have been ideal if our dataset included all forty-two traits in Aaker’s framework. However, as noted earlier, most studies do not use all the BP traits in this framework to measure BPDs, seemingly because BP traits are best conceptualized as reflective indicators of BPDs.

Our data enable us to help answer questions that are difficult to address without the analysis of a data set like ours, yet they have limitations. Their main weakness is probably that our BPD variables are derived, as explained previously, from BP traits measured on binary scales. These scales force respondents to make dualistic evaluations, collapsing potentially important nuances in BP perceptions. One could, for instance, question how strongly respondents must associate a brand with a given trait to rate it as possessing that trait on a binary scale, and whether respondents’ internal threshold for categorizing a brand as having a given trait varies from trait to trait. The more positively skewed distributions and lower means of Sophisticationit and Ruggednessit (see Table 1) suggest that this threshold could be higher for the traits that form these two BPDs than for those that form the other three BPDs. These conceivable issues are perhaps less likely with the Likert scales typically used in the BP literature. Although the evidence in WA 1 should alleviate some concerns about the validity of our BPD measures, we cannot completely exclude the possibility that this binary method of data collection captures a different cognitive representation of a brand’s personality than finer-grained ratings. Hence, our study might suffer from decreased comparability with the studies in that literature. We hope that future research will examine whether our findings can be replicated using data collected differently. We also hope that future research will seek to uncover the conditions under which the BPDs of sophistication and ruggedness are more influential than the other three BPDs.

With our brand-level data, we also cannot empirically establish that shifts in values and the personality profile of the population change the proportion of customers who sense more and stronger congruities between their selves and a given BPD. Field or laboratory experiments that could test this mechanism with participants from different generational cohorts would be insightful. We also recognize that changes in self-brand congruence caused by shifts in values and the personality profile of the population might not be the sole contributing factors to the evolution of the effects of BPDs. We hope that future work will seek to uncover additional forces that might give rise to some aspects of this evolution. For example, to the extent that a sophisticated or rugged BPD reflects concepts of femininity and masculinity (for opposing views, see Aaker, 1997; Grohmann, 2009; Maehle et al., 2011), their diminished effects might correlate with the growing rejection of gender stereotypes that brands often exploit. Future research could also investigate when and how changes in a brand’s personality affect customers’ perceptions of brand authenticity because these perceptions might also help explain the effects we document.

Our analysis, model specification, and data restrict the number and type of moderators we can examine. For example, because we estimate a fixed-effect model to address potential endogeneity concerns, we cannot examine the moderating effects of time-invariant brand characteristics. Our preliminary exploratory analyses address other potential sources of heterogeneity in the effects of BPDs, but these analyses have limitations, as stated earlier. Thus, we call for studies into the effects of BPDs across countries because it is unlikely that BPDs have similar impacts universally. We also call for studies into the effects of BPDs on brands’ financial performance; only a few BP articles examine the association of BPDs or BP traits with financial performance (Luffarelli et al., 2019). Correspondingly, our analysis focuses on absolute BPD scores. It neither considers the relative score of a given BPD compared to a brand’s other BPDs, nor the personality profile of a brand’s main competitors. However, BP singularity (Malär et al., 2012) and originality (the extent to which a BP is perceived to be novel and distinct from that of competing brands; Freling et al., 2011) can affect customer responses. Future work can add to ours by assessing how the influence of these two BP characteristics has evolved over time and how they might moderate the effects of BPDs on CBBE.

Finally, we conceptualize time as a continuum divisible into objective, quantifiable units (years). Future studies might investigate BPD effects using other temporal lenses. Perhaps some BPDs grow more or less influential, depending on the season or time of day. Perhaps the effects of BPDs on CBBE change at varying phases of the product life cycle. Particular events (e.g., natural disasters) might also prompt fluctuations in the magnitude of the effects of BPDs. In a related sense, it would be valuable to understand the potential impact of exogenous shocks that could affect some of the Big Five dimensions of human personality at the population level and thus shape aggregate BPD effects. One such shock is the current COVID-19 pandemic. The work of Sutin et al. (2020) indicates that levels of agreeableness and conscientiousness do not appear to have changed due to this pandemic, unlike levels of extraversion, which might have increased slightly. In the aftermath of the pandemic, the effect of the BPD of excitement on CBBE might thus have become even more positive than our results suggest. However, as of this writing, there is not enough research on the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on enduring personality traits to appreciate how it will affect the evolution of BPD effects. We hope that work will study how the effects documented in our manuscript for the years 2001–2018 may have changed during and after this exogeneous shock, when its impact becomes clearer. Exploring research directions such as the ones we discussed in this section would not only advance theoretical knowledge about BPD effects but would also yield actionable insights for marketing practitioners.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

The authors sincerely thank Thijs Broekhuizen, Stephanie Feiereisen, and Panos Markou for their helpful comments on earlier versions of this article. They are also grateful for the financial support by Montpellier Business School and the data set provided by the BAV consulting group. The second and third authors have contributed equally to this study. They are listed in alphabetical order.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

Both “customer-based brand equity” and “consumer-based brand equity” have been used to refer to the same construct. We employ the former, which is more frequently used in the marketing literature, including Keller’s (1993) seminal article.

This search, conducted in April 2022, included all the journals in the marketing category of the 2018 Chartered ABS Journal Guide, the Journal of Business Research, and the Journal of Business Ethics. Only articles with the keywords “brand personality(ies)” in the abstract or title were counted. Therefore, this estimate is conservative.

This was the number of citations in April 2022.

The BPDs established initially among U.S. customers can diverge in other countries. In Spain, for example, the BPDs are excitement, sincerity, sophistication, passion, and peacefulness (Aaker et al., 2001). The data set for this study includes responses only from U.S. customers. However, we also report a preliminary, exploratory analysis of the effects of BPDs in Japan.

The data set we received from the BAV group contains information about 7,483 unique brands. However, because we enforce a more conventional definition of what constitutes a brand than the BAV group uses, we exclude several types of brands from our analyses: religions (e.g., Hinduism), festivals and holidays (e.g., Thanksgiving), military and governmental organizations (e.g., the U.S. Congress), locations (e.g., Argentina), loyalty programs (e.g., Delta SkyMiles), nonprofit organizations (e.g., Doctors Without Borders), celebrities and mascots (e.g., George Clooney), and a few brands classified as miscellaneous (e.g., Santa Claus). A robustness test shows that our findings are not a byproduct of this sampling decision.

The BAV measure is often adjusted to accommodate research objectives (for examples, see Batra et al., 2017; Heitmann et al., 2020; Stahl et al., 2012). We adjust it to avoid mechanical correlations between our dependent and independent variables. We recalculate the BAV scores after excluding the items “unique,” “leader,” and “reliable” because these items are BP traits in Aaker’s framework. The adjusted measure correlates strongly with the original, unadjusted BAV measure (r = .96).

Most studies do not use all of the BP traits in Aaker’s framework to measure BPDs (for examples, see Aaker et al., 2004; Brakus et al., 2009; Lovett et al., 2013; Luffarelli et al., 2019; Wentzel 2009), seemingly because BP traits are best conceptualized as reflective indicators of BPDs. Thus, using some but not all of the traits to capture BPDs should not alter their conceptual meaning (for a discussion, see Jarvis et al., 2003). The empirical evidence offered in WA 1 supports this view. For the same reason, the addition of the trait “cool” to the Excitementit measure when Yeart = 2018 and the removal of the trait “tough” from the Ruggednessit measure when Yeart ≥ 2006 should not threaten the validity of our findings. A robustness test offers empirical support for this assertion.

Hausman specification tests indicate that brand fixed effects are more appropriate than random effects to estimate Eq. 1 (χ2 = 25,076, p < .001) and Eq. 2 (χ2 = 34,492, p < .001).

In models that include BPD × Yeart interaction terms, the VIF exceeds the rule-of-thumb threshold of 10. However, high VIFs created by the inclusion of interaction terms can be safely ignored because they neither imply a multicollinearity problem nor should raise concerns for the estimation and interpretation of the results (for discussions, see Disatnik and Sivan 2016).

“Generally, using log(1 + x) and then interpreting the estimates as if the variable were log(y) is acceptable when the data on y contain relatively few zeros” (Wooldridge 2012, p. 193). Our BPD measures contain only eighteen zero values. For simplicity, then, we interpret the estimates as if our variables were log(y) transformed.

We find financial data for relatively few brands, because the Compustat database provides access only to data for publicly traded brands, whereas our data set includes many brands not listed on the stock market.

This analysis is available in WA 9. We find that luxury brands benefit more from nurturing a sophisticated BP than other types of brands and have not experienced a decline in the effect of this BPD.

These analyses are available in WA 9.

V Kumar served as Area Editor for this article.

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Jonathan Luffarelli, Email: j.luffarelli@montpellier-bs.com.

Sebastiano A. Delre, Email: s.delre@montpellier-bs.com

Polina Landgraf, Email: ysk3we@virginia.edu.

References

- Aaker JL. Dimensions of brand personality. Journal of Marketing Research. 1997;34(3):347–356. doi: 10.1177/002224379703400304. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Aaker JL, Benet-Martinez V, Garolera J. Consumption symbols as carriers of culture: A study of Japanese and Spanish brand personality constructs. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2001;81(3):482–508. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.81.3.492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aaker JL, Fournier S, Brasel SA. When good brands do bad. Journal of Consumer Research. 2004;31(1):1–16. doi: 10.1086/383419. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Aaker JL, Garbinsky EN, Vohs KD. Cultivating admiration in brands: Warmth, competence, and landing in the "golden quadrant". Journal of Consumer Psychology. 2012;22(2):191–194. doi: 10.1016/j.jcps.2011.11.012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Aaker JL, Vohs KD, Mogilner C. Nonprofits are seen as warm and for-profits as competent: Firm stereotypes matter. Journal of Consumer Research. 2010;37(2):224–237. doi: 10.1086/651566. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Aguirre-Rodriguez A, Bosnjak M, Sirgy MJ. Moderators of the self-congruity effect on consumer decision-making: A meta-analysis. Journal of Business Research. 2012;65(8):1179–1188. doi: 10.1016/j.jbusres.2011.07.031. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Astakhova M, Swimberghe KR, Wooldridge BR. Actual and ideal-self congruence and dual brand passion. Journal of Consumer Marketing. 2017;34(7):664–672. doi: 10.1108/JCM-10-2016-1985. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Batra R, Zhang YC, Aydinoğlu NZ, Feinberg FM. Positioning multicountry brands: The impact of variation in cultural values and competitive set. Journal of Marketing Research. 2017;54(6):914–931. doi: 10.1509/jmr.13.0058. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Benet-Martinez V, Karakitapoglu-Aygün Z. The interplay of cultural syndromes and personality in predicting life satisfaction: Comparing Asian Americans and European Americans. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology. 2003;34(1):38–60. doi: 10.1177/0022022102239154. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett AM, Hill RP. The universality of warmth and competence: A response to brands as intentional agents. Journal of Consumer Psychology. 2012;22(2):199–204. doi: 10.1016/j.jcps.2011.10.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Billstedt E, Waern M, Duberstein P, Marlow T, Hellström T, Östling S, Skoog I. Secular changes in personality: Study on 75-year-olds examined in 1976–1977 and 2005–2006. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2013;28(3):298–304. doi: 10.1002/gps.3825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brakus JJ, Schmitt BH, Zarantonello L. Brand Experience: What is it? How is it measured? Does it affect loyalty? Journal of Marketing. 2009;73(3):52–68. doi: 10.1509/jmkg.73.3.052. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brasel SA, Hagtvedt H. Living brands: Consumer responses to animated brand logos. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science. 2016;44(5):639–653. doi: 10.1007/s11747-015-0449-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]