Abstract

Background

Although potential therapeutic candidates for heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF) are emerging, it is still unclear whether they will be effective in patients with left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) of 60% or higher. Our aim was to identify the clinical characteristics of these patients with HFpEF by comparing them to patients with LVEF below 60%.

Methods and Results

From a multicenter, prospective, observational cohort (PURSUIT‐HFpEF [Prospective Multicenter Obsevational Study of Patients with Heart Failure with Preserved Ejection Fraction]), we investigated 812 consecutive patients (median age, 83 years; 57% women), including 316 with 50% ≤ LVEF <60% and 496 with 60% ≤ LVEF, and compared the clinical backgrounds of the 2 groups and their prognoses for cardiac mortality or HF readmission. Two hundred four adverse outcomes occurred at a median of 366 days. Multivariable Cox regression tests adjusted for age, sex, heart rate, atrial fibrillation, estimated glomerular filtration rate, N‐terminal pro‐B‐type natriuretic peptide, and prior heart failure hospitalization revealed that systolic blood pressure (hazard ratio [HR], 0.925 [95% CI, 0.862–0.992]; P=0.028), high‐density lipoprotein to C‐reactive protein ratio (HR, 0.975 [95% CI, 0.944–0.995]; P=0.007), and left ventricular end‐diastolic volume index (HR, 0.870 [95% CI, 0.759–0.997]; P=0.037) were uniquely associated with outcomes among patients with 50% ≤ LVEF <60%, whereas only the ratio of peak early mitral inflow velocity to velocity of mitral annulus early diastolic motion e′(HR, 1.034 [95% CI, 1.003–1.062]; P=0.034) was associated with outcomes among patients with 60% ≤ LVEF.

Conclusions

Prognostic factors show distinct differences between patients with HFpEF with 50% ≤ LVEF <60% and with 60% ≤ LVEF. These findings suggest that the 2 groups have different inherent pathophysiology.

Registration

URL: https://upload.umin.ac.jp/cgi‐open‐bin/ctr_e/ctr_view.cgi?recptno=R000024414; Unique identifier: UMIN000021831 PURSUIT‐HFpEF.

Keywords: heart failure with preserved ejection fraction, left ventricular ejection fraction, prognostic factor

Subject Categories: Heart Failure, Echocardiography, Prognosis, Mortality/Survival, Imaging

Nonstandard Abbreviations and Acronyms

- E/e′

ratio of peak early mitral inflow velocity to velocity of mitral annulus early diastolic motion e′

- HFpEF

heart failure with preserved ejection fraction

- HFrEF

heart failure with reduced ejection fraction

- LAVI

left atrial volume index

- LVEDVI

left ventricular end‐diastolic volume index

- LVMI

left ventricular mass index

- SVI

stroke volume index

- TAPSE

tricuspid annular plane systolic excursion

Clinical Perspective.

What Is New?

This is the first large observational study focusing on the differences between patients with heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF) with 50% ≤ left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) <60% and those with 60% ≤ LVEF from a prospective multicenter registry in East Asia (PURSUIT‐HFpEF [Prospective Multicenter Obsevational Study of Patients with Heart Failure with Preserved Ejection Fraction]).

Left ventricular end‐diastolic volume index, heart rate, and hemoglobin concentration were significantly different between patients with HFpEF whose LVEF was below or above 60%.

Although systolic blood pressure, high‐density lipoprotein/C‐reactive protein ratio, and left ventricular end‐diastolic volume index were characteristic prognostic factors in patients with HFpEF with LVEF below 60%, ratio of peak early mitral inflow velocity to velocity of mitral annulus early diastolic motion e′ was uniquely highlighted in patients with LVEF above 60%.

What Are the Clinical Implications?

These highlighted factors may allow us to propose possible hypotheses as to the cause of the different treatment effects of angiotensin receptor‐neprilysin inhibitor and sodium‐glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitor on patients with HFpEF with lower and higher LVEF, observed in the PARAGON‐HF (Prospective Comparison of ARNI With ARB Global Outcomes in HF With Preserved Ejection Fraction) and EMPEROR‐Preserved (Empagliflozin Outcome Trial in Patients With Chronic Heart Failure With Preserved Ejection Fraction) trials.

The ratio of peak early mitral inflow velocity to velocity of mitral annulus early diastolic motion e′ was particularly shown to be important for the prognosis of patients with HFpEF with LVEF above 60%, for whom a reliable therapeutic response has not been well established. Further investigations of what this parameter reflects among them will help us to find better ways to manage these difficult‐to‐treat patients.

Although several therapeutic drugs have been established for heart failure (HF) with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF), 1 the discovery of a therapeutic strategy for heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF) has been long awaited. The positive result of the EMPEROR‐Preserved (Empagliflozin Outcome Trial in Patients With Chronic Heart Failure With Preserved Ejection Fraction) study, 2 which showed that empagliflozin reduced the combined risk of cardiovascular death and HF hospitalization in patients with HFpEF, provided welcome hope for a treatment strategy for these patients. Despite the excellent main result, subgroup analysis revealed that effective results were limited to patients with left ventricular (LV) ejection fraction (LVEF) <50% and with LVEF ≥50% to <60%, and that no benefit accrued to patients with LVEF ≥60%. The PARAGON‐HF (Prospective Comparison of ARNI With ARB Global Outcomes in HF With Preserved Ejection Fraction) study 3 made the important suggestion of an angiotensin receptor–neprilysin inhibitor as a potential treatment choice for HFpEF. Although the main result was unfortunate, subgroup analysis showed that patients with LVEF ≤57% (median of participants) accrued a beneficial effect, but those with >57% did not.

The results of these latest trials have led to reconsideration of the clinical implications of LVEF in patients with HFpEF. The different therapeutic effects between upper and lower LVEF patients could have resulted from pathophysiological differences between the 2 populations. A recent HF classification based on LVEF was proposed partly on the basis of treatment strategies, and the consensus statement for this defines HFpEF as LVEF ≥50%. 4 We propose that efforts to establish effective treatment strategies overall for patients with HFpEF would benefit from a focus on the differences between patients with HFpEF with lower and higher LVEF.

As shown between patients with HFrEF and HFpEF, prognostic factors also likely differ between populations that pathophysiologically differ with regard to LVEF. 5 We previously reported several prognostic factors among hospitalized East Asian patients with HFpEF based on a prospective multicenter observational cohort, including sex, 6 blood pressure, 7 high‐density lipoprotein (HDL) to CRP (C‐reactive protein) ratio, 8 diastolic dysfunction, 9 LV filling pressure, 10 , 11 and right ventricular to pulmonary circulation coupling evaluated with tricuspid annular plane systolic excursion (TAPSE) to pulmonary arterial systolic pressure (PASP) ratio. 12 , 13

In the present exploratory study, we aimed to compare clinical characteristics, including these factors which we previously focused and reported as important prognostic markers, between patients with HFpEF with lower and higher LVEF. We also aimed to suggest potential pathophysiological differences between them, which might lead to the different pharmacological effects of the featured drugs.

METHODS

The authors declare that all supporting data are available within the article and its supplemental files.

Study Protocol and Setting

The PURSUIT‐HFpEF (Prospective Multicenter Obsevational Study of Patients with Heart Failure with Preserved Ejection Fraction) registry is a prospective, multicenter, observational cohort study that enrolled consecutive patients who were hospitalized for acute decompensated heart failure. Details of the registry have been described previously. 14 Briefly, in collaboration with 31 hospitals in Japan, we enrolled consecutive acute decompensated patients with HF who met the Framingham criteria 15 and the following on admission: (1) LVEF ≥50%, and (2) NT‐proBNP (N‐terminal pro‐B‐type natriuretic peptide) ≥400 pg/mL or brain natriuretic peptide ≥100 pg/mL. Major exclusion criteria were age <20 years, severe valvular disease or acute coronary syndrome on admission, life expectancy <6 months because of prognosis for a noncardiac disease, or previous heart transplantation. The anonymized data were transferred to Osaka University Hospital for analysis via a data capture system connected with electronic medical records. 16 Written informed consent was received from each participating patient. This study conformed to the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the institutional review board of each participating facility. It was registered under the Japanese UMIN Clinical Trials Registration (UMIN000021831).

Study Population

The 1095 patients with HFpEF were registered from June 2016 to December 2020. Of all participants, we excluded 17 patients who died in the hospital, 7 who were diagnosed as having cardiac amyloidosis, and 30 with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. We excluded an additional 162 patients whose LVEF at discharge was missing and 67 whose LVEF was <50%. Finally, 812 patients whose LVEF was above 50% at discharge were analyzed in this study (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Patients analyzed in this study.

Tree chart of the patient‐selection process. HCM indicates hypertrophic cardiomyopathy; HFpEF, heart failure with preserved ejection fraction; and LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction.

Laboratory Tests and Echocardiography

Laboratory and echocardiographic data were obtained at discharge. Comprehensive echocardiographic examinations were performed by trained cardiac sonographers in accordance with the American Society of Echocardiography guidelines. 17 In patients with atrial fibrillation (AF), recordings of 5 to 7 consecutive beats were recommended. Measurement of systolic or diastolic parameters for 1 beat occurring after 2 serial beats with average RR interval or 1 beat with an average Doppler wave contour with an average velocity was also permitted in accordance with previous studies. 18 LVEF, LV end‐diastolic volume index (LVEDVI), and stroke volume index (SVI) were calculated with the biplane Simpson method using apical 2‐ and 4‐chamber views. Left atrial volume index (LAVI) was also calculated with the biplane Simpson method. LV mass index (LVMI) was estimated with the Devereux formula. 19 Each parameter was indexed by body surface area. Relative wall thickness and cardiac remodeling category were defined according to the guideline. 17 The ratio of peak early mitral inflow velocity to the velocity of mitral annulus early diastolic motion e′ (E/e′) was calculated with the mean e′ velocity obtained from the septal and lateral sides of the mitral annulus. TAPSE and right ventricular dimension were obtained using a right ventricular focused apical 4‐chamber view, and PASP was estimated using diameter/collapsibility of the inferior vena cava and tricuspid regurgitation pressure gradient. 12

Clinical Outcome Measurement

The primary outcome was measured as a composite of cardiac mortality or HF rehospitalization. Duration of the follow‐up period was calculated from the day of discharge until an outcome, or to the time of last patient contact. Outpatient management after discharge was at the discretion of the attending physician at each facility. Outcomes and last patient contacts were generally checked up on at least once a year until 5 years after the discharge by confirming the last visits to each facility or by contact by telephone or mail interview to the patients, their family members, or the latest attending physicians.

Statistical Analysis

Continuous variables are presented as medians and interquartile ranges of 25% to 75% and were compared using the Kruskal‐Wallis test. Categorical variables are presented as numbers with percentages and were compared using Pearson χ2 test. The clinical end point was assessed with the Kaplan‐Meier method and compared with the log‐rank test for dichotomized groups divided by categorical variables and median values of continuous variables among the whole population. Cox proportional hazards regression models were used to calculate hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% CIs for associations between clinical factors of interest and outcome. These factors comprised fundamental background (age and sex); well‐established prognostic factors for patients with HFpEF 20 (HF history, AF, diabetes, estimated glomerular filtration rate [eGFR], NT‐proBNP, and the diastolic function markers 21 of LAVI, LVMI, and E/e′), including prognostic factors reported from our previous investigations in this registry (systolic blood pressure, 7 HDL/CRP, 8 and TAPSE/PASP ratios 12 , 13 ), and background factors that significantly differed between the 2 groups (heart rate, hematocrit, and LVEDVI). We used multivariable Cox proportional hazards regression analysis with statistical interaction terms to test for effect modification (described as P for interaction) in each LVEF‐categorized group. We then provided the stratified analysis to explore associations within each group. Multivariable Cox regression tests on outcomes for distinctive and interactive prognostic factors in each subgroup were performed using the covariates of age, sex, heart rate, AF, eGFR, log‐transformed NT‐proBNP, and prior HF hospitalization history. Although we studied lots of subgroup analyses, we considered corrections for multiple analyses were unnecessary because of the exploratory purpose. All statistical tests were 2‐sided, and P<0.05 as well as P for interaction <0.10 were regarded as statistically significant. Statistical analysis was performed using JMP Pro 13.2.1 (SAS Institute, Chicago, IL) or R software version 4.0.2 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria).

RESULTS

Patient Characteristics

Demographic and clinical characteristics of the patients are summarized in Table 1. In the overall population of 812, the median age was 83 years, 57% were women, and 23% had a history of prior HF. The major potential triggers for HF worsening were arrhythmia (237 cases, 29%) and excessive sodium/water intake (220 cases, 27%) (Table S1). They consisted of 316 patients (39%) with 50% ≤ LVEF <60% (LVEF50‐60) and 496 (61%) with 60% ≤ LVEF (LVEF60–). The LVEF50–60 and LVEF60– groups did not significantly differ in basic characteristics, including age (LVEF50–60 versus LVEF60–, 82 versus 83 years, P=0.204), sex (women of 53% versus 59%, P=0.087), prior HF history (24% versus 22%, P=0.589), and frequency of each comorbidity. Furthermore, although SVI (31.5 versus 32.5 mL/m2, P=0.075), LAVI (50 versus 49 mL/m2, P=0.758), E/e′ (12.2 versus 12.6, P=0.384), and LVMI (104 versus 101 mL/m2, P=0.103) were not statistically different, LVEDVI (57 versus 50 mL/m2, P<0.001) was significantly lower in the LVEF60– group of patients regardless of their lower heart rate (72 versus 69 bpm, P=0.005). Patients in the LVEF60– group showed lower NT‐proBNP (1290 versus 880 pg/mL, P<0.001) despite a higher PASP (30 versus 32 mm Hg, P=0.025). TAPSE (16.8 versus 18.0 mm, P<0.001), reflecting right ventricular contractility, was higher in the LVEF60– group of patients, whereas TAPSE/PASP ratio (0.55 versus 0.55 mm/mm Hg, P=0.280) was not statistically different between the groups. Hemoglobin concentration (11.4 versus 11.1 g/dL, P=0.002) and hematocrit (35.0% versus 33.7%, P=0.002) was significantly lower in the LVEF60– group. Among the potential triggers for HF worsening, cardiac ischemia was more frequently observed in the LVEF50–60 group (15 cases, 5%) than LVEF60– group (11 cases, 2%) (P=0.046; Table S1).

Table 1.

Patient Characteristics

| Characteristic | Overall, n=812 | Missing | 50% ≤ LVEF <60%, n=316 | 60% ≤ LVEF, n=496 | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, y | 83 [77–87] | 0 | 82 [76–87] | 83 [78–87] | 0.204 |

| Sex, women | 472 (57) | 0 | 168 (53) | 294 (59) | 0.087 |

| HF history | 182 (23) | 16 | 74 (24) | 108 (22) | 0.589 |

| Hypertension | 693 (86) | 3 | 264 (84) | 429 (87) | 0.306 |

| Diabetes | 269 (33) | 4 | 98 (31) | 171 (34) | 0.368 |

| Dyslipidemia | 345 (43) | 4 | 124 (39) | 221 (45) | 0.142 |

| Coronary artery disease | 147 (18) | 6 | 60 (19) | 87 (18) | 0.609 |

| Pacemaker implantation | 64 (8) | 1 | 24 (8) | 40 (8) | 0.802 |

| Stroke | 111 (14) | 6 | 38 (12) | 73 (15) | 0.272 |

| Sleep apnea | 39 (5) | 76 | 14 (5) | 25 (5) | 0.763 |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 61 (8) | 36 | 18 (6) | 43 (9) | 0.126 |

| Chronic kidney disease | 324 (40) | 6 | 131 (42) | 193 (39) | 0.482 |

| Malignancy | 99 (12) | 11 | 36 (12) | 63 (13) | 0.591 |

| Data at discharge | |||||

| Systolic blood pressure, mm Hg | 119 [107–132] | 0 | 118 [106–130] | 120 [107–132] | 0.376 |

| Heart rate, bpm | 70 [61–78] | 0 | 72 [62–80] | 69 [60–78] | 0.019 |

| Atrial fibrillation | 297 (37) | 1 | 112 (35) | 185 (37) | 0.578 |

| Hemoglobin, g/dL | 11.2 [10.0–12.5] | 1 | 11.4 [10.3–13.0] | 11.1 [9.7–12.3] | 0.002 |

| Hematocrit, % | 34.2 [30.8–38.1] | 1 | 35.0 [31.3–39.4] | 33.7 [30.1–37.6] | 0.002 |

| eGFR, mL/min per 1.73 m2 | 42 [30–55] | 13 | 44 [32–56] | 42 [29–54] | 0.396 |

| HDL, mg/dL | 43 [35–52] | 79 | 43 [35–52] | 43 [36–52] | 0.986 |

| CRP, mg/dL | 0.29 [0.11–0.80] | 10 | 0.29 [0.11–0.83] | 0.28 [0.11–0.79] | 0.743 |

| HDL/CRP | 148 [51–385] | 81 | 150 [48–407] | 145 [53–374] | 0.588 |

| NT‐proBNP, pg/mL | 1048 [466–2369] | 92 | 1290 [584–2720] | 880 [371–2005] | <0.001 |

| LVDd, mm | 45 [41–50] | 0 | 46 [41–51] | 45 [41–49] | 0.011 |

| LVEDV, mL | 77 [58–100] | 18 | 82 [63–109] | 74 [57–97] | <0.001 |

| LVEDVI, mL/m2 | 53 [41–66] | 23 | 57 [43–71] | 50 [40–63] | <0.001 |

| LVMI, g/m2 | 102 [85–121] | 8 | 104 [85–125] | 101 [86–119] | 0.103 |

| Relative wall thickness | 0.43 [0.37–0.50] | 2 | 0.42 [0.36–0.49] | 0.43 [0.38–0.50] | 0.130 |

| Remodeling category | 8 | 0.558 | |||

| Normal geometry | 236 (29) | 91 (29) | 145 (30) | ||

| Concentric remodeling | 188 (23) | 76 (24) | 112 (23) | ||

| Eccentric hypertrophy | 149 (19) | 64 (20) | 85 (17) | ||

| Concentric hypertrophy | 231 (29) | 83 (26) | 148 (30) | ||

| LVEF, % | 62 [57–66] | 0 | 55 [53–58] | 65 [62–69] | <0.001 |

| SVI, mL/m2 | 32.2 [25.2–40.6] | 23 | 31.5 [24.0–39.2] | 32.5 [25.6–41.2] | 0.075 |

| LAVI, mL/m2 | 49 [36–64] | 79 | 50 [36–63] | 49 [36–64] | 0.758 |

| E/e′, mean | 12.5 [9.8–16.8] | 51 | 12.2 [9.5–16.9] | 12.6 [10.0–16.8] | 0.384 |

| RVD, mm | 32 [28–36] | 92 | 32 [28–36] | 32 [27–36] | 0.456 |

| TAPSE, mm | 17.5 [14.8–20.4] | 50 | 16.8 [13.2–19.0] | 18.0 [15.4–21.2] | <0.001 |

| PASP, mm Hg | 31 [26–38] | 93 | 30 [25–38] | 32 [26–39] | 0.025 |

| TAPSE/PASP | 0.55 [0.42–0.72] | 117 | 0.55 [0.40–0.72] | 0.55 [0.43–0.73] | 0.280 |

| Medication at discharge | |||||

| Antiplatelet | 242 (30) | 1 | 97 (31) | 145 (29) | 0.670 |

| ACEi or ARB | 457 (56) | 0 | 176 (56) | 281 (57) | 0.789 |

| Calcium channel blocker | 416 (51) | 1 | 147 (47) | 269 (54) | 0.030 |

| β‐Blocker | 456 (56) | 1 | 195 (62) | 261 (53) | 0.012 |

| Loop diuretics | 640 (79) | 0 | 249 (79) | 391 (79) | 0.991 |

| Tolvaptan | 136 (17) | 0 | 49 (16) | 87 (18) | 0.449 |

| Mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist | 317 (39) | 0 | 145 (46) | 172 (35) | 0.001 |

| SGLT2 inhibitor | 50 (6) | 2 | 20 (6) | 30 (6) | 0.883 |

| Statins | 278 (34) | 0 | 104 (33) | 174 (35) | 0.512 |

| Digitalis | 31 (4) | 1 | 14 (4) | 17 (3) | 0.471 |

| Warfarin | 100 (12) | 0 | 39 (12) | 61 (12) | 0.692 |

| DOAC | 386 (48) | 0 | 157 (50) | 229 (46) | 0.292 |

Values are given as median [interquartile range] or n (%). Between‐group comparisons were performed using the Kruskal‐Wallis test or Pearson χ2 test. ACEi indicates angiotensin‐converting enzyme inhibitor; ARB, angiotensin receptor blocker; CRP, C‐reactive protein; DOAC, direct oral anticoagulants; E/e′, ratio of peak early mitral inflow velocity to velocity of mitral annulus early diastolic motion e′; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; HDL, high‐density lipoprotein cholesterol; HF, heart failure; LAVI, left atrial volume index; LVDd, left ventricular diastolic dimension; LVEDV, left ventricular end‐diastolic volume; LVEDVI, left ventricular end‐diastolic volume index; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; LVMI, left ventricular mass index; NT‐proBNP, N‐terminal pro‐B‐type natriuretic peptide; PASP, pulmonary arterial systolic pressure; RVD, right ventricular dimension; SGLT2, sodium‐glucose cotransporter 2; SVI, stroke volume index; and TAPSE, tricuspid annular plane systolic excursion.

Prognostic Factors on Clinical Outcome

Among the 812 patients, 204 patients (79 [25%] in the LVEF50–60 group and 125 [25%] in the LVEF60– group; Table 2) reached the clinical outcome of cardiac mortality or HF rehospitalization with a median (interquartile range) follow‐up of 366 days (93–720 days). Survival curve analysis showed that prognosis of the LVEF60– group did not differ to that of the LVEF50–60 group (log‐rank P=0.7970; Figure 2).

Table 2.

Adverse Outcomes

| Outcome | Overall, n=812 | Missing | 50% ≤ LVEF <60%, n=316 | 60% ≤ LVEF, n=496 | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All‐cause death | 143 (18) | 0 | 56 (18) | 87 (18) | 0.947 |

| Cardiac death | 55 (7) | 0 | 24 (8) | 31 (6) | 0.457 |

| HF rehospitalization | 193 (24) | 0 | 75 (24) | 118 (24) | 0.985 |

| Cardiac death+HF rehospitalization | 204 (25) | 0 | 79 (25) | 125 (25) | 0.949 |

Values are given as n (%). Between‐group comparisons were performed using Pearson χ2 test. HF indicates heart failure; and LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction.

Figure 2. Kaplan‐Meier curves of patients with HFpEF whose LVEF was below or above 60%.

HF indicates heart failure; HFpEF, heart failure with preserved ejection fraction; and LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction.

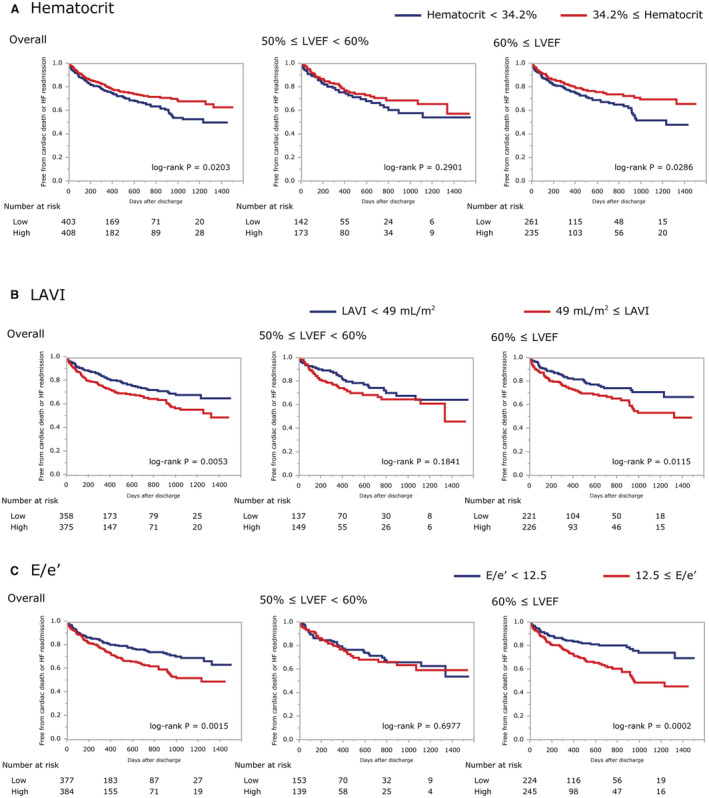

Sex (log‐rank P of overall, LVEF50–60, and LVEF60–: 0.6506, 0.8793, and 0.4357, respectively), diabetes (log‐rank P: 0.9079, 0.3790, and 0.3971, respectively), SVI (log‐rank P: 0.9326, 0.1026, and 0.1716, respectively), and LVMI (log‐rank P: 0.5803, 0.6446, and 0.2997, respectively) were not distinctive prognostic factors in any of the overall, LVEF50–60, or LVEF60– groups (Figure S1). On the other hand, HF history (log‐rank P: <0.0001, 0.0011, and <0.0001, respectively), AF (log‐rank P: 0.0025, 0.0498, and 0.0216, respectively), NT‐proBNP (log‐rank P: <0.0001, <0.0001, and 0.0002, respectively), eGFR (log‐rank P: 0.0004, 0.0356, and 0.0037, respectively), and TAPSE/PASP ratio (log‐rank P: 0.0007, 0.0135, and 0.0191, respectively) were significantly associated with the prognosis in all 3 groups (Figure S2). In addition, systolic blood pressure (log‐rank P: 0.3250, 0.0034, and 0.2809, respectively), heart rate (log‐rank P: 0.033, 0.0063, and 0.1115, respectively), HDL/CRP ratio (log‐rank P: 0.5632, 0.0133, and 0.2117, respectively), and LVEDVI (log‐rank P: 0.5608, 0.0380, and 0.3988, respectively) were particularly significant prognostic factors in the LVEF50–60 group (Figure 3). In contrast, LAVI (log‐rank P: 0.0053, 0.1841, and 0.0115, respectively), E/e′ (log‐rank P: 0.0015, 0.6977, and 0.0002, respectively), and hematocrit (log‐rank P: 0.0203, 0.2901, and 0.0286, respectively) were specific and significant prognostic factors in the LVEF60– group (Figure 4).

Figure 3. Kaplan‐Meier curves by potential specific prognostic factors for patients with 50% ≤ LVEF <60%.

Patients are divided with the median values of systolic blood pressure (A), heart rate (B), HDL/CRP ratio (C) and LVEDVI (D). CRP indicates C‐reactive protein; HDL, high‐density lipoprotein; HF, heart failure; LVEDVI, left ventricular end‐diastolic volume index; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; and SBP, systolic blood pressure.

Figure 4. Kaplan‐Meier curves by potential specific prognostic factors for patients with 60% ≤ LVEF.

Patients are divided with the median values of hematocrit (A), LAVI (B) and E/e' (C). E/e′, ratio of peak early mitral inflow velocity to velocity of mitral annulus early diastolic motion e′; HF, heart failure; LAVI, left atrial volume index; and LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction.

Univariable Cox regression models showed similar results (Figure 5). LVEF itself was not a significant prognostic factor for the overall population (HR, 0.962 [95% CI, 0.862–1.073] in 5% increments; P=0.491), for the LVEF50–60 group (HR, 0.740 [95% CI, 0.501–1.097] in 5% increments; P=0.133), and for the LVEF60– group (HR, 0.986 [95% CI, 0.809–1.189] in 5% increments; P=0.887). Moreover, multivariable Cox regression analyses also showed that LVEF did not predict adverse events even after adjusted by sex for the overall population (HR, 0.960 [95% CI, 0.859–1.071] in 5% increments; P=0.469), for the LVEF50–60 group (HR, 0.739 [95% CI, 0.497–1.100] in 5% increments; P=0.135), and for the LVEF60– group (HR, 0.984 [95% CI, 0.806–1.187] in 5% increments; P=0.869).

Figure 5. Predictors of composite outcome assessed by univariable Cox regression.

Forest plot depicting univariable HRs for the composite outcome (time to cardiac mortality or heart failure rehospitalization). CRP indicates C‐reactive protein; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; E/e′, ratio of peak early mitral inflow velocity to velocity of mitral annulus early diastolic motion e′; HF, heart failure; HR, hazard ratio; LAVI, left atrial volume index; log NT‐proBNP, log‐transformed N‐terminal pro–B‐type natriuretic peptide; LVEDVI, left ventricular end‐diastolic volume index; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; LVMI, left ventricular mass index; PASP, pulmonary arterial systolic pressure; SBP, systolic blood pressure; SVI, stroke volume index; and TAPSE, tricuspid annular plane systolic excursion.

Distinctive prognostic factors for the LVEF50–60 group were systolic blood pressure (HR, 0.896 [95% CI, 0.835–0.959] in 5‐mm Hg increments; P=0.001), heart rate (HR, 1.099 [95% CI, 1.013–1.188] in 5‐bpm increments; P=0.023), HDL/CRP ratio (HR, 0.961 [95% CI, 0.926–0.987] in 50‐unit increments; P<0.001), LVEDVI (HR, 0.878 [95% CI, 0.782–0.980] in 10‐mL/m2 increments; P=0.019), and SVI (HR, 0.891 [95% CI, 0.802–0.984] in 5‐mL/m2 increments; P=0.023), whereas those for the LVEF60– group were hematocrit (HR, 0.733 [95% CI, 0.616–0.867] in 5% increments; P<0.001), eGFR (HR, 0.823 [95% CI, 0.743–0.909] in 10‐mL/min per 1.73 m2 increments; P<0.001), and E/e′ (HR, 1.038 [95% CI, 1.012–1.060] in 1‐unit increments; P=0.004). Among these factors, systolic blood pressure (P for interaction, 0.004), hematocrit (P for interaction, 0.026), eGFR (P for interaction, 0.053), HDL/CRP ratio (P for interaction, 0.027), LVEDVI (P for interaction, 0.008), SVI (P for interaction, 0.011), and E/e′ (P for interaction, 0.047) had significant interactions for outcome with an effect modification by the LVEF categorization.

Both survival curve analysis and univariable Cox regression models showed that systolic blood pressure, HDL/CRP ratio, and LVEDVI were particularly distinctive prognostic factors for the LVEF50–60 group, and that hematocrit and E/e′ were also for the LVEF60– group. Multivariable Cox regression models were analyzed to adjust the predictability of these factors with age, sex, heart rate, AF, eGFR, NT‐proBNP, and prior HF history (Table 3). Although systolic blood pressure (HR, 0.925 [95% CI, 0.862–0.992] in 5‐mm Hg increments; P=0.028), HDL/CRP ratio (HR, 0.975 [95% CI, 0.944–0.995] in 50‐unit increments; P=0.007), and LVEDVI (HR, 0.870 [95% CI, 0.759–0.997] in 10‐mL/m2 increments; P=0.037) were revealed to be unique and statistically significant after adjustment for other factors in the LVEF50–60 group, only E/e′ (HR, 1.034 [95% CI, 1.003–1.062] in 1‐unit increments; P=0.034) was in the LVEF60– group. It should be also noted that only LVEDVI in the LVEF50–60 group (P for interaction, 0.011) had significant interaction for outcome with an effect modification by the LVEF categorization.

Table 3.

Multivariable Cox Regression Hazard Models for the Composite End Point of Cardiac Death or Heart Failure Readmission

| Overall: HR [95% CI] | P value | 50% ≤ LVEF <60%: HR [95% CI] | P value | 60% ≤ LVEF: HR [95% CI] | P value | P for interaction | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SBP, 5‐mm Hg increments | 0.994 [0.952–1.037] | 0.789 | 0.925 [0.862–0.992] | 0.028 | 1.045 [0.988–1.105] | 0.120 | 0.124 |

| Hematocrit, 5% increments | 0.936 [0.808–1.084] | 0.372 | 1.104 [0.889–1.355] | 0.365 | 0.827 [0.672–1.018] | 0.069 | 0.061 |

| HDL/CRP, 50‐unit increments | 0.993 [0.983–1.001] | 0.094 | 0.975 [0.944–0.995] | 0.007 | 0.999 [0.989–1.007] | 0.830 | 0.212 |

| LVEDVI, 10‐mL/m2 increments | 1.000 [0.921–1.080] | 0.996 | 0.870 [0.759–0.997] | 0.037 | 1.087 [0.981–1.195] | 0.110 | 0.011 |

| E/e′, 1‐unit increments | 1.015 [0.993–1.035] | 0.175 | 0.999 [0.963–1.028] | 0.954 | 1.034 [1.003–1.062] | 0.034 | 0.125 |

Cox regression tests were adjusted by age, sex, heart rate, atrial fibrillation, estimated glomerular filtration rate, log‐transformed N‐terminal pro‐B‐type natriuretic peptide, and prior heart failure history. CRP indicates C‐reactive protein; E/e′, ratio of peak early mitral inflow velocity to velocity of mitral annulus early diastolic motion e′; HDL, high‐density lipoprotein; HR, hazard ratio; LVEDVI, left ventricular end‐diastolic volume index; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; and SBP, systolic blood pressure.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we examined differences in clinical characteristics and prognostic factors between patients with LVEF below and above 60% in the PURSUIT‐HFpEF, an East Asian prospective, multicenter, observational study. The major finding was that LVEDVI, heart rate and hemoglobin concentration were significantly different between patients with HFpEF whose LVEF was below or above 60%. Furthermore, we also found more interestingly that prognostic outcomes showed no differences between these 2 groups, and that although systolic blood pressure, HDL/CRP ratio, and LV volume were characteristic prognostic factors in patients with LVEF below 60%, E/e′ was uniquely highlighted in patients with LVEF above 60%. Whereas it might still be difficult to explain what caused the different therapeutic effects on patients with HFpEF with higher and lower LVEF in PARAGON‐HF study and EMPEROR‐Preserved study, these findings indicate that key pathophysiological factors differed quite substantially between the 2 populations.

No Significant Prognostic Differences Between Lower and Higher LVEF Patients With HFpEF

As shown in the I‐PRESERVE (Irbesartan in Heart Failure with Preserved Systolic Function) trial, LVEF is a strong predictor of outcomes in HFpEF. 20 The TOPCAT (Treatment of Preserved Cardiac Function Heart Failure With an Aldosterone Antagonist Trial) also showed that lower LVEF predicted major outcomes, and that spironolactone had a favorable treatment effect, 22 as well as that systolic dysfunction had prognostic importance using LV longitudinal strain. 23 These previous studies were based on their respective inclusion criteria and an HFpEF definition of LVEF ≥45%. Although the adverse event risk of patients with LVEF50–60 did not significantly differ from that of patients with LVEF60– in our present study, this may be partly attributable to our different inclusion criteria of LVEF ≥50% compared with these previous studies.

Lower LVEF Patients With HFpEF Have Some Aspects of HFrEF

Patient characteristics assessment revealed that patients with LVEF50–60 presented larger LVEDVI than patients with LVEF60–, whereas their LVMI and SVI were not statistically different. Patients with LVEF50–60 showed a slightly larger LV volume than a healthy Japanese population on 3‐dimensional echocardiography (mean LVEDVI in men and in women was 50±12 and 46±9 mL/m2, respectively). 24 Lower LVEF patients showed a larger LV size even among patients with HFpEF, which was consistent with prior findings from comparisons of the TOPCAT, CHARM (Candesartan Cilexietil in Heart Failure Assessment of Reduction in Mortality and Morbidity), CHARMES (Echocardiographic Substudy), and PARAMOUNT (Prospective Comparison of ARNI With ARB on Management of Heart Failure With Preserved Ejection Fraction) trials. 25 The increased LV volume in patients with LVEF50–60 possibly reflects compensatory mechanisms for potential LV systolic dysfunction, as observed in the HFrEF phenotype. 26

Key Clinical Factors Among Lower LVEF Patients With HFpEF

A multivariable Cox regression model showed that systolic blood pressure, LVEDVI, and HDL/CRP ratio were particular prognostic factors among patients with LVEF50–60 (Table 3).

Lower blood pressure was associated with higher adverse event risks in this study. This association has been reported not only in HFrEF 27 , 28 , 29 but also in HFpEF. 30 It was speculated that lower blood pressure in HFpEF might reflect a more advanced disease state and lower cardiac output. The major difference between HFrEF and HFpEF lies in the fact that the loss of contractile function is accompanied by proportional LV enlargement in HFrEF, versus only slight LV dilatation in HFpEF. 31 LV dilatation in HFrEF compensates for the loss of contractile function. On this basis, the association between lower LVEDVI and worse outcome among patients with LVEF50–60 may reflect inadequate compensation for the loss of systolic function. The pathogenesis of contractile dysfunction in patients with HFpEF is possibly related to inflammation. 32 From the PURSUIT‐HFpEF registry, Yano et al evaluated the HDL/CRP ratio as an anti‐inflammatory marker and showed that the ratio on admission was an independent predictor for all‐cause mortality and cardiac death in patients with HFpEF. 8 We found that the ratio at discharge, in a more stable status, was a distinctive prognostic factor among lower LVEF patients with HFpEF. Empagliflozin potentially restores cardiac microvascular endothelial function via the modulation of inflammatory mediators. 33 Another sodium‐glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitor, dapagliflozin, is reported to mediate the proposed athero‐protective effects of elevated HDL and to ameliorate thrombin‐platelet‐mediated inflammation. 34 We found that a possible inflammatory marker of HDL/CRP ratio had significant prognostic importance among lower LVEF patients with HFpEF.

The prognostic importance of systolic blood pressure, HDL/CRP ratio, and LVEDVI in patients with LVEF50–60 with HFpEF might suggest that the pathophysiology closely links to the potential contractile dysfunction and eccentric remodeling, which partly overlap with HFrEF.

Key Clinical Factors in Higher LVEF Patients With HFpEF

Although E/e′ ratio was similar in the LVEF50–60 and LVEF60– groups, we found that it was a distinctive prognostic factor among patients with LVEF60– but not among patients with LVEF50–60 on not only univariable but also multivariable Cox regression models with adjustment for age, sex, heart rate, AF, eGFR, NT‐proBNP, and HF history (Table 3). E/e′ has been reported to be a prognostic factor for patients with HFpEF, 35 , 36 but precisely what E/e′ reflects warrants careful interpretation. E/e′ ratio is used to estimate LV filling pressure and diastolic function, but diagnostic accuracy is limited among patients with HFpEF because of the difficulty in reliably measuring LV chamber stiffness. 37 The Euro‐Filling study revealed that the positive and negative predictive values of an average E/e′ ratio ≥14 in detecting abnormal invasive LV filling pressure were modest, at only 56% and 62%, respectively. 38 It is noteworthy that E/e′ ratio was more definitive in the prognosis of our patients with LVEF60– than LVMI and LAVI, which also closely relate to diastolic function. This finding in turn emphasizes the particular importance of E/e′ among higher LVEF patients with HFpEF. Our findings indicate that patients with LVEF60– have some pathogenesis that is closely related to E/e′. These results warrant further investigation to clarify what E/e′ reflects in clinical settings.

Although many systemic background variables, including comorbidities and laboratory markers, showed no significant differences between our LVEF50–60 and LVEF60– groups, patients with LVEF60– presented with lower hematocrit, as was also seen in a previous study. 39 The negative result of multivariable Cox regression analysis among patients with LVEF60– showed that the prognostic value of anemia might represent confounding by other factors. However, it is noteworthy that a low hematocrit level was significantly associated with a poor prognosis on univariable Cox regression testing. Because anemia is reported to be an important prognostic factor among patients with HFpEF 40 and to be even more common in patients with HF with higher LVEF, 41 hemoglobin concentration should be enough focused.

The prognostic importance of E/e′ in patients with LVEF60– with HFpEF might suggest that diastolic dysfunction is deeply involved in the pathophysiology. Given the importance of hemoglobin concentration, systemic problems might also comprise the pathophysiology.

Nonnegligible Factors Among Patients With HFpEF Regardless of LVEF Category

LVEF is one profile factor in patients with HF. A consensus statement noted that, in addition to LVEF, cardiac structural and functional information is also important in guiding appropriate management for patients with HFpEF. 4 As shown in our univariable Cox regression testing (Figure 5), heart rate, AF, LAVI, and TAPSE/PASP ratio as well as NT‐proBNP were shown to warrant attention overall in patients with HFpEF, suggesting that the fundamental pathophysiology that causes these architectural and functional alterations should not be ignored. Increased wall stress is a common key factor for both of HFrEF and HFpEF, and affects cardiac myocyte morphology, ventricular volume, and wall thickness. 42 Moreover, systolic dysfunction is not unique to HFrEF, and diastolic dysfunction is not unique to HFpEF, meaning that all forms of HF are hybrids involving both abnormalities in varying proportion. 43 We showed here that LVEF could stratify patients with HFpEF into pathophysiologically differing subgroups.

LVEF is also known to be closely related to LV geometry, including intrasarcomeric cytoskeleton, extrasarcomeric cytoskeleton, and extracellular matrix. 44 Concentric LV hypertrophy is frequently observed in patients with HFpEF, and increased wall thickness amplifies systolic thickening, compensates for the decrease in myocardial fiber shortening, and preserves LVEF. 45 Although the distributions of LV remodeling category did not significantly differ between the LVEF50–60 and LVEF60– groups (P=0.558; Table 1), it should be noted that geometric aspects must be also considered when evaluating actual cardiac function among patients with HFpEF.

Limitations

Several limitations of this study should be noted. First, we analyzed 812 enrolled patients after excluding 162 without LVEF data, which could have introduced unavoidable selection bias. Second, the patient population was exclusively East Asian with quite an advanced age (median of 83 years), and the generalizability of our findings should therefore be considered carefully. Additionally, all patients were hospitalized with acute decompensated HF, and thus differed from participants in the EMPEROR‐Preserved and PARAGON‐HF trials, which should also be considered carefully when comparing results. Third, because we registered patients with HFpEF based on data at admission, we were unable to avoid including HF with patients with recovered LVEF. Fourth, despite the central interest in LVEF, we did not observe global longitudinal strain, which could provide more detailed evaluation for cardiac function including the systolic–diastolic coupling 46 among patients with HFpEF, because the strain was unfortunately not commonly measured in the participating centers. Cardiac sonographers were not blinded to clinical information, which may have caused measurement bias. Moreover, measurements were done by sonographers and were not evaluated by an imaging core laboratory. Fifth, the limited number of follow‐up completion among event‐free patients in this study must be noticed. Because the prognostic follow‐up period was planned to be as long as 5 years after discharge in the PURSUIT‐HFpEF registry, most of the event‐free patients were still under follow‐up. Of the 608 event‐free patients, only 2 completed the 5‐year follow‐up. Finally, further investigations including a purpose for verification are required to confirm the results of this study and to support a deeper understanding of the meaning of LVEF among patients with HFpEF.

CONCLUSIONS

We showed in a multicenter observational cohort study that prognostic factors distinctly differ between patients with HFpEF with 50% ≤ LVEF <60% versus those with 60% ≤ LVEF. These findings suggest that there are underlying pathophysiologic differences between these subgroups, upon which therapeutic strategies should be arranged.

Sources of Funding

This work was funded by Roche Diagnostics KK (Minato‐ku, Tokyo, Japan) and Fuji Film Toyama Chemical Co. Ltd. (Chuo‐ku, Tokyo, Japan).

Disclosures

Dr Nakatani has received honoraria from Roche Diagnostics. Dr Hikoso has received personal fees from Daiichi Sankyo Company, Bayer, Astellas Pharma, Pfizer Pharmaceuticals, and Boehringer Ingelheim Japan; and grants from Roche Diagnostics, FUJIFILM Toyama Chemical, and Actelion Pharmaceuticals. Dr Sakata has received personal fees from Otsuka Pharmaceutical, Ono Pharmaceutical, Daiichi Sankyo Company, Mitsubishi Tanabe Pharma Corporation, and Actelion Pharmaceuticals; and grants from Roche Diagnostic, FUJIFILM Toyama Chemical, Abbott Medical, Japan, Otsuka Pharmaceutical, Daiichi Sankyo Company, Mitsubishi Tanabe Pharma Corporation, and Biotronik. The other authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Supporting information

Data S1

Table S1

Figures S1–S2

Acknowledgments

The authors thank all of the investigators, clinical research coordinators, and data managers involved in the PURSUIT‐HFpEF registry for their dedicated contributions. In particular, the authors thank N. Yoshioka, K. Tatsumi, S. Kishimoto, N. Murakami, and S. Mitsuoka for their excellent assistance with data collection.

Supplemental Material is available at https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/suppl/10.1161/JAHA.122.025300

For Sources of Funding and Disclosures, see page 13.

REFERENCES

- 1. Vaduganathan M, Claggett BL, Jhund PS, Cunningham JW, Pedro Ferreira J, Zannad F, Packer M, Fonarow GC, McMurray JJV, Solomon SD. Estimating lifetime benefits of comprehensive disease‐modifying pharmacological therapies in patients with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction: a comparative analysis of three randomised controlled trials. Lancet. 2020;396:121–128. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30748-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Anker SD, Butler J, Filippatos G, Ferreira JP, Bocchi E, Böhm M, Brunner‐La Rocca HP, Choi DJ, Chopra V, Chuquiure‐Valenzuela E, et al. Empagliflozin in heart failure with a preserved ejection fraction. N Engl J Med. 2021;385:1451–1461. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2107038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Solomon SD, McMurray JJV, Anand IS, Ge J, Lam CSP, Maggioni AP, Martinez F, Packer M, Pfeffer MA, Pieske B, et al. Angiotensin‐neprilysin inhibition in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. N Engl J Med. 2019;381:1609–1620. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1908655 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Bozkurt B, Coats AJS, Tsutsui H, Abdelhamid CM, Adamopoulos S, Albert N, Anker SD, Atherton J, Böhm M, Butler J, et al. Universal definition and classification of heart failure: a report of the Heart Failure Society of America, Heart Failure Association of the European Society of Cardiology, Japanese Heart Failure Society and Writing Committee of the Universal Definition of Heart Failure: endorsed by the Canadian Heart Failure Society, Heart Failure Association of India, Cardiac Society of Australia and New Zealand, and Chinese Heart Failure Association. Eur J Heart Fail. 2021;23:352–380. doi: 10.1002/ejhf.2115 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Ho JE, Enserro D, Brouwers FP, Kizer JR, Shah SJ, Psaty BM, Bartz TM, Santhanakrishnan R, Lee DS, Chan C, et al. Predicting heart failure with preserved and reduced ejection fraction: the International Collaboration on Heart Failure Subtypes. Circ Heart Fail. 2016;9:e003116. doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.115.003116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Sotomi Y, Hikoso S, Nakatani D, Mizuno H, Okada K, Dohi T, Kitamura T, Sunaga A, Kida H, Oeun B, et al. Sex differences in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. J Am Heart Assoc. 2021;10:e018574. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.120.018574 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Nakagawa A, Yasumura Y, Yoshida C, Okumura T, Tateishi J, Yoshida J, Tamaki S, Yano M, Hayashi T, Nakagawa Y, et al. Distinctive prognostic factor of heart failure with preserved ejection fraction stratified with admission blood pressure. ESC Heart Fail. 2021;8:3145–3155. doi: 10.1002/ehf2.13420 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Yano M, Nishino M, Ukita K, Kawamura A, Nakamura H, Matsuhiro Y, Yasumoto K, Tsuda M, Okamoto N, Tanaka A, et al. High density lipoprotein cholesterol/C reactive protein ratio in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. ESC Heart Fail. 2021;8:2791–2801. doi: 10.1002/ehf2.13350 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Oeun B, Hikoso S, Nakatani D, Mizuno H, Suna S, Kitamura T, Okada K, Dohi T, Sotomi Y, Kojima T, et al. Prognostic impact of echocardiographic diastolic dysfunction on outcomes in patients with heart failure with preserved ejection fraction—insights from the PURSUIT‐HFpEF registry. Circ J. 2021;86:23–33. doi: 10.1253/circj.CJ-21-0300 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Matsuhiro Y, Nishino M, Ukita K, Kawamura A, Nakamura H, Yasumoto K, Tsuda M, Okamoto N, Tanaka A, Matsunaga‐Lee Y, et al. Alternative echocardiographic algorithm for left ventricular filling pressure in patients with heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Am J Cardiol. 2021;143:80–88. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2020.12.035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Abe H, Kosugi S, Ozaki T, Mishima T, Date M, Ueda Y, Uematsu M, Tamaki S, Yano M, Hayashi T, et al. Prognostic impact of echocardiographic congestion grade in HFpEF with and without atrial fibrillation. JACC: Asia. 2022;2:73–84. doi: 10.1016/j.jacasi.2021.10.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Nakagawa A, Yasumura Y, Yoshida C, Okumura T, Tateishi J, Yoshida J, Abe H, Tamaki S, Yano M, Hayashi T, et al. Prognostic importance of right ventricular‐vascular uncoupling in acute decompensated heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging. 2020;13:e011430. doi: 10.1161/CIRCIMAGING.120.011430 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Nakagawa A, Yasumura Y, Yoshida C, Okumura T, Tateishi J, Yoshida J, Abe H, Tamaki S, Yano M, Hayashi T, et al. Prognostic importance of pulmonary arterial capacitance in acute decompensated heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. J Am Heart Assoc. 2021;10:e023043. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.121.023043 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Suna S, Hikoso S, Yamada T, Uematsu M, Yasumura Y, Nakagawa A, Takeda T, Kojima T, Kida H, Oeun B, et al. Study protocol for the PURSUIT‐HFpEF study: a prospective, multicenter, observational study of patients with heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. BMJ Open. 2020;10:e038294. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-038294 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Vasan RS, Levy D. Defining diastolic heart failure: a call for standardized diagnostic criteria. Circulation. 2000;101:2118–2121. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.101.17.2118 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Matsumura Y, Hattori A, Manabe S, Takahashi D, Yamamoto Y, Murata T, Nakagawa A, Mihara N, Takeda T. Case report form reporter: a key component for the integration of electronic medical records and the electronic data capture system. Stud Health Technol Inform. 2017;245:516–520. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Lang RM, Badano LP, Mor‐Avi V, Afilalo J, Armstrong A, Ernande L, Flachskampf FA, Foster E, Goldstein SA, Kuznetsova T, et al. Recommendations for cardiac chamber quantification by echocardiography in adults: an update from the American Society of Echocardiography and the European Association of Cardiovascular Imaging. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2015;28:1–39.e14. doi: 10.1016/j.echo.2014.10.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Abe Y, Akamatsu K, Ito K, Matsumura Y, Shimeno K, Naruko T, Takahashi Y, Shibata T, Yoshiyama M. Prevalence and prognostic significance of functional mitral and tricuspid regurgitation despite preserved left ventricular ejection fraction in atrial fibrillation patients. Circ J. 2018;82:1451–1458. doi: 10.1253/circj.CJ-17-1334 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Devereux RB. Detection of left ventricular hypertrophy by M‐mode echocardiography. Anatomic validation, standardization, and comparison to other methods. Hypertension. 1987;9:II19–II26. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.9.2_pt_2.ii19 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Komajda M, Carson PE, Hetzel S, McKelvie R, McMurray J, Ptaszynska A, Zile MR, Demets D, Massie BM. Factors associated with outcome in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: findings from the Irbesartan in Heart Failure with Preserved Ejection Fraction Study (I‐PRESERVE). Circ Heart Fail. 2011;4:27–35. doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.109.932996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Kane GC, Karon BL, Mahoney DW, Redfield MM, Roger VL, Burnett JC Jr, Jacobsen SJ, Rodeheffer RJ. Progression of left ventricular diastolic dysfunction and risk of heart failure. JAMA. 2011;306:856–863. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.1201 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Solomon SD, Claggett B, Lewis EF, Desai A, Anand I, Sweitzer NK, O'Meara E, Shah SJ, McKinlay S, Fleg JL, et al. Influence of ejection fraction on outcomes and efficacy of spironolactone in patients with heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Eur Heart J. 2016;37:455–462. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehv464 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Shah AM, Claggett B, Sweitzer NK, Shah SJ, Anand IS, Liu L, Pitt B, Pfeffer MA, Solomon SD. Prognostic importance of impaired systolic function in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction and the impact of spironolactone. Circulation. 2015;132:402–414. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.115.015884 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Fukuda S, Watanabe H, Daimon M, Abe Y, Hirashiki A, Hirata K, Ito H, Iwai‐Takano M, Iwakura K, Izumi C, et al. Normal values of real‐time 3‐dimensional echocardiographic parameters in a healthy Japanese population: the JAMP‐3D Study. Circ J. 2012;76:1177–1181. doi: 10.1253/circj.CJ-11-1256 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Shah AM, Shah SJ, Anand IS, Sweitzer NK, O'Meara E, Heitner JF, Sopko G, Li G, Assmann SF, McKinlay SM, et al. Cardiac structure and function in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: baseline findings from the echocardiographic study of the Treatment of Preserved Cardiac Function Heart Failure with an Aldosterone Antagonist Trial. Circ Heart Fail. 2014;7:104–115. doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.113.000887 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Bristow MR, Kao DP, Breathett KK, Altman NL, Gorcsan J III, Gill EA, Lowes BD, Gilbert EM, Quaife RA, Mann DL. Structural and functional phenotyping of the failing heart: is the left ventricular ejection fraction obsolete? JACC Heart Fail. 2017;5:772–781. doi: 10.1016/j.jchf.2017.09.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Gheorghiade M, Abraham WT, Albert NM, Greenberg BH, O'Connor CM, She L, Stough WG, Yancy CW, Young JB, Fonarow GC. Systolic blood pressure at admission, clinical characteristics, and outcomes in patients hospitalized with acute heart failure. JAMA. 2006;296:2217–2226. doi: 10.1001/jama.296.18.2217 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Desai RV, Banach M, Ahmed MI, Mujib M, Aban I, Love TE, White M, Fonarow G, Deedwania P, Aronow WS, et al. Impact of baseline systolic blood pressure on long‐term outcomes in patients with advanced chronic systolic heart failure (insights from the BEST trial). Am J Cardiol. 2010;106:221–227. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2010.02.032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Banach M, Bhatia V, Feller MA, Mujib M, Desai RV, Ahmed MI, Guichard JL, Aban I, Love TE, Aronow WS, et al. Relation of baseline systolic blood pressure and long‐term outcomes in ambulatory patients with chronic mild to moderate heart failure. Am J Cardiol. 2011;107:1208–1214. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2010.12.020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Tsimploulis A, Lam PH, Arundel C, Singh SN, Morgan CJ, Faselis C, Deedwania P, Butler J, Aronow WS, Yancy CW, et al. Systolic blood pressure and outcomes in patients with heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. JAMA Cardiol. 2018;3:288–297. doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2017.5365 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Ky B, Plappert T, Kirkpatrick J, Silvestry FE, Ferrari VA, Keane MG, Wiegers SE, Chirinos JA, St John Sutton M. Left ventricular remodeling in human heart failure: quantitative echocardiographic assessment of 1,794 patients. Echocardiography. 2012;29:758–765. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8175.2012.01701.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Nevers T, Salvador AM, Grodecki‐Pena A, Knapp A, Velázquez F, Aronovitz M, Kapur NK, Karas RH, Blanton RM, Alcaide P. Left ventricular T‐cell recruitment contributes to the pathogenesis of heart failure. Circ Heart Fail. 2015;8:776–787. doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.115.002225 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Juni RP, Kuster DWD, Goebel M, Helmes M, Musters RJP, van der Velden J, Koolwijk P, Paulus WJ, van Hinsbergh VWM. Cardiac microvascular endothelial enhancement of cardiomyocyte function is impaired by inflammation and restored by empagliflozin. JACC Basic Transl Sci. 2019;4:575–591. doi: 10.1016/j.jacbts.2019.04.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Kohlmorgen C, Gerfer S, Feldmann K, Twarock S, Hartwig S, Lehr S, Klier M, Krüger I, Helten C, Keul P, et al. Dapagliflozin reduces thrombin generation and platelet activation: implications for cardiovascular risk reduction in type 2 diabetes mellitus. Diabetologia. 2021;64:1834–1849. doi: 10.1007/s00125-021-05498-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Donal E, Lund LH, Oger E, Hage C, Persson H, Reynaud A, Ennezat PV, Bauer F, Drouet E, Linde C, et al. New echocardiographic predictors of clinical outcome in patients presenting with heart failure and a preserved left ventricular ejection fraction: a subanalysis of the Ka (Karolinska) Ren (Rennes) Study. Eur J Heart Fail. 2015;17:680–688. doi: 10.1002/ejhf.291 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Okura H, Kubo T, Asawa K, Toda I, Yoshiyama M, Yoshikawa J, Yoshida K. Elevated E/E' predicts prognosis in congestive heart failure patients with preserved systolic function. Circ J. 2009;73:86–91. doi: 10.1253/circj.CJ-08-0457 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Sharifov OF, Schiros CG, Aban I, Denney TS, Gupta H. Diagnostic accuracy of tissue Doppler index E/e' for evaluating left ventricular filling pressure and diastolic dysfunction/heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. J Am Heart Assoc. 2016;5:e002530. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.115.002530 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Lancellotti P, Galderisi M, Edvardsen T, Donal E, Goliasch G, Cardim N, Magne J, Laginha S, Hagendorff A, Haland TF, et al. Echo‐Doppler estimation of left ventricular filling pressure: results of the multicentre EACVI Euro‐Filling study. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2017;18:961–968. doi: 10.1093/ehjci/jex067 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Kitada S, Kikuchi S, Tsujino T, Masuyama T, Ohte N. The prognostic value of brain natriuretic peptide in patients with heart failure and left ventricular ejection fraction higher than 60%: a sub‐analysis of the J‐MELODIC study. ESC Heart Fail. 2018;5:36–45. doi: 10.1002/ehf2.12206 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Okuno K, Naito Y, Asakura M, Sugahara M, Ando T, Yasumura S, Nagai T, Saito Y, Yoshikawa T, Masuyama T, et al. Effective blood hemoglobin level to predict prognosis in heart failure with preserved left ventricular ejection fraction: results of the Japanese heart failure syndrome with preserved ejection fraction registry. Heart Vessels. 2019;34:1168–1177. doi: 10.1007/s00380-019-01349-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Savarese G, Jonsson Å, Hallberg AC, Dahlström U, Edner M, Lund LH. Prevalence of, associations with, and prognostic role of anemia in heart failure across the ejection fraction spectrum. Int J Cardiol. 2020;298:59–65. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2019.08.049 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Katz AM, Rolett EL. Heart failure: when form fails to follow function. Eur Heart J. 2016;37:449–454. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehv548 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. De Keulenaer GW, Brutsaert DL. Systolic and diastolic heart failure are overlapping phenotypes within the heart failure spectrum. Circulation. 2011;123:1996–2005. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.981431 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Triposkiadis F, Giamouzis G, Boudoulas KD, Karagiannis G, Skoularigis J, Boudoulas H, Parissis J. Left ventricular geometry as a major determinant of left ventricular ejection fraction: physiological considerations and clinical implications. Eur J Heart Fail. 2018;20:436–444. doi: 10.1002/ejhf.1055 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. de Simone G, Devereux RB. Rationale of echocardiographic assessment of left ventricular wall stress and midwall mechanics in hypertensive heart disease. Eur J Echocardiogr. 2002;3:192–198. doi: 10.1053/euje.3.3.192 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Hasselberg NE, Haugaa KH, Sarvari SI, Gullestad L, Andreassen AK, Smiseth OA, Edvardsen T. Left ventricular global longitudinal strain is associated with exercise capacity in failing hearts with preserved and reduced ejection fraction. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2015;16:217–224. doi: 10.1093/ehjci/jeu277 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data S1

Table S1

Figures S1–S2