Abstract

Background

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention's Surveillance of Congenital Heart Defects Across the Lifespan project uses large clinical and administrative databases at sites throughout the United States to understand population‐based congenital heart defect (CHD) epidemiology and outcomes. These individual databases are also relied upon for accurate coding of CHD to estimate population prevalence.

Methods and Results

This validation project assessed a sample of 774 cases from 4 surveillance sites to determine the positive predictive value (PPV) for identifying a true CHD case and classifying CHD anatomic group accurately based on 57 International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD‐9‐CM) codes. Chi‐square tests assessed differences in PPV by CHD severity and age. Overall, PPV was 76.36% (591/774 [95% CI, 73.20–79.31]) for all sites and all CHD‐related ICD‐9‐CM codes. Of patients with a code for complex CHD, 89.85% (177/197 [95% CI, 84.76–93.69]) had CHD; corresponding PPV estimates were 86.73% (170/196 [95% CI, 81.17–91.15]) for shunt, 82.99% (161/194 [95% CI, 76.95–87.99]) for valve, and 44.39% (83/187 [95% CI, 84.76–93.69]) for “Other” CHD anatomic group (X 2=142.16, P<0.0001). ICD‐9‐CM codes had higher PPVs for having CHD in the 3 younger age groups compared with those >64 years of age, (X 2=4.23, P<0.0001).

Conclusions

While CHD ICD‐9‐CM codes had acceptable PPV (86.54%) (508/587 [95% CI, 83.51–89.20]) for identifying whether a patient has CHD when excluding patients with ICD‐9‐CM codes for “Other” CHD and code 745.5, further evaluation and algorithm development may help inform and improve accurate identification of CHD in data sets across the CHD ICD‐9‐CM code groups.

Keywords: birth defects, congenital heart defects, epidemiology, surveillance, validation

Subject Categories: Epidemiology, Congenital Heart Disease

Nonstandard Abbreviations and Acronyms

- CDC

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

- eHR

electronic health record

Clinical Perspective.

What Is New?

Four US sites associated with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention's Surveillance of Congenital Heart Defects Across the Lifespan project validated a sample of 774 cases with International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD‐9‐CM) congenital heart disease (CHD) codes to assess true CHD cases.

The majority of cases were associated with true CHD, though differences in positive predictive value (PPV) were noted based on anatomic complexity and ages of patients.

Cases with complex CHD codes, multiple CHD codes, and age groups <65 years of age had greater PPV identifying true CHD.

What Are the Clinical Implications?

ICD‐9‐CM codes can identify patients with CHD in databases with high PPV for the complex code group, but lower PPV in certain patient groups, particularly those aged >65 years, and with “Other” CHD ICD code group.

When attempting to identify cases with CHD, the presence of >1 CHD code increases the PPV for a true CHD, at the expense of sensitivity.

Development of algorithms is needed to improve the identification of CHD cases in databases across anatomic code groups and age ranges.

Research and surveillance of patients with congenital heart defects (CHD) using administrative and clinical data both rely on the diagnostic accuracy of applying International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD‐9‐CM) and International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD‐10‐CM) codes to detect CHD cases. Administrative data, commonly referred to as claims data, are data created for the purpose of either the billing of health care encounters or record keeping for a health care system or an organization. ICD codes captured in administrative data may vary by medical practice, health care system, and region; thus, it is unknown how representative these ICD codes are for their intended disease state. In a recent study conducted by Khan et al. (2018), ICD‐9‐CM administrative codes extracted from the electronic health record (eHR) of patients with various types of CHD lesions seen at a large academic health care system were <50% accurate (48.7% [95% CI, 47%–51%]) at classifying those with a true CHD. 1 However, when only patients with moderate or complex CHD anatomy were included, the positive predictive value (PPV) of having CHD increased to 77.2%, (95% CI, 74%–81%). When other factors like younger age, adult CHD, provider type, and ECG, or echocardiogram were documented at the CHD‐related encounter, the C‐statistic was 0.89 (95% CI, 0.88–0.90). 1 Correctly and consistently applied definitions of CHD may increase the accuracy of CHD prevalence, health care use, and health outcomes of individuals living with CHD using administrative health care data sets. However, prior studies have demonstrated that some ICD‐9‐CM codes may be associated with false positives and thus do not always reliably identify individuals who truly have CHD. 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 , 5

In studies of CHD using publicly available data sets like the National Inpatient Sample and the Kids' Inpatient Database or administrative data sources, a CHD case is typically defined by ICD‐9‐CM codes 745.xx to 747.xx for classification and more recently ICD‐10‐CM codes Q20 to Q28. While the range of these codes is broad and inclusive, this code group contains conditions that are not CHD, and thus, may include individuals who do not have CHD, creating misleading conclusions and misinformation. Furthermore, some codes in the CHD group may code for CHD, but may commonly be used incorrectly, as for “rule out” or normal variants. In particular, individuals with 1 CHD‐related ICD‐9‐CM code —745.5 — are often misclassified as having CHD. Frequently found in large CHD administrative data sets and commonly included in CHD literature, the ICD‐9‐CM code 745.5 (hereafter referred to as “code 745.5”) is used for both secundum atrial septal defect, a true CHD, and patent foramen ovale, a normal variant and not considered a CHD, seen in about 25% of the population. 2

The current project aims to validate the extent to which CHD‐related ICD‐9‐CM codes correctly identify CHD cases in administrative and clinical records by: (1) confirming patients as having a true CHD; and (2) classifying CHD anatomic grouping among those with true CHD. We hypothesized that both individual CHD codes and CHD anatomic groupings would have a high PPV (>80%) for CHD that would vary by anatomic group, but that coding errors would likely include patients who did not truly have a CHD.

Methods

This analysis has been replicated by 2 independent analysts. Because of the sensitive nature of the data collected for this study, requests to access the data set from qualified researchers trained in human subject confidentiality protocols may be sent to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) at jill.glidewell@cdc.hhs.gov.

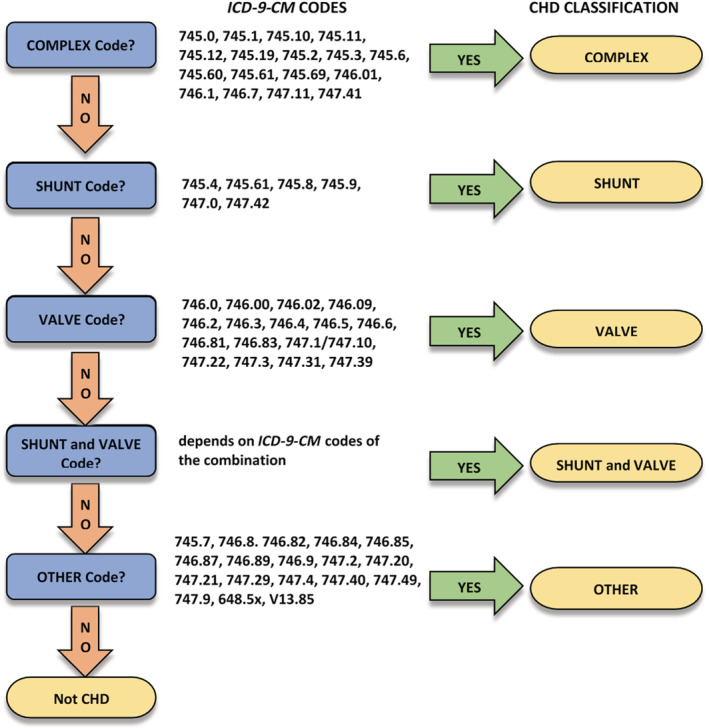

To improve upon CHD classification and as part of the multiyear CDC‐sponsored project Surveillance of Congenital Heart Defects Across the Lifespan (CDC‐RFA‐DD15‐1506), 6 4 sites reviewed the medical records of cases with CHD‐related ICD‐9‐CM codes identified from administrative data sources to calculate the PPV of these codes (745.xx–747.xx) in correctly identifying a case with CHD. Cases were ascertained by the presence of any CHD‐related 745.xx to 747.xx ICD‐9‐CM code documented in a health care encounter between January 1, 2011 and December 31, 2013. Inclusion criteria defined a case having the presence of any included ICD‐9‐CM code at any encounter, regardless of how many encounters had CHD ICD‐9‐CM codes. The ICD‐9‐CM codes to define the ICD code‐based anatomic groups were based on a hierarchy of codes, complex>shunt and valve>shunt or valve>“Other” CHD. The following codes were excluded as they were determined to be reflective of conditions other than true CHD: congenital heart block (746.86), absent/hypoplastic umbilical artery (747.5), pulmonary arteriovenous malformation (747.32), other anomalies of peripheral vascular system (747.6x), and other specified anomalies of circulatory system (747.8x); these codes were also excluded from the definition of CHD in the prior surveillance methods paper. 5 , 6 Cases with code 745.5 without another included CHD ICD‐9‐CM code were also excluded based on previous studies. 2 , 3 The Institutional Review Boards from Duke University in North Carolina (NC), Emory University in Georgia (GA), the New York State Department of Health (NY), and University of Utah (UT) approved an analysis of deidentified data to assess PPV of CHD‐related ICD‐9‐CM codes. 6 The requirement for informed consent was waived by each site's respective Institutional Review Board. Eligible codes were classified into 1 of 5 CHD anatomic groups: complex, shunts, valves, shunts and valves, and “Other” CHD or non‐specific defects 5 , 6 , 7 , 8 (Figure 1 and Data S1). Complex anatomy was based on native anatomy and defined as heart defects characterized by a recognized constellation of multiple specific defects which generally require intervention in the first year of life. Specific defects grouped as “complex” are defined in Data S1. 5 , 6 A code‐based hierarchy was developed such that the presence of a complex code designates the case as complex regardless of additional codes. 6 In the absence of a complex code, the presence of both a shunt and valve code designated “shunt and valve” group inclusion. The absence of complex, shunt or valve codes and only “Other” CHD anatomic group codes designated the case as belonging to the “Other” CHD anatomic group (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

ICD‐9‐CM code‐based hierarchy for congenital heart defect classification by native CHD anatomy group.

*Based on hierarchy reported in Ref. [6]. Individuals aged 1 to 64 years with documented congenital heart defects at health care encounters, 5 US surveillance sites, 2011 to 2013. CHD indicates congenital heart defect; and ICD‐9‐CM, International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification.

Data and Procedures

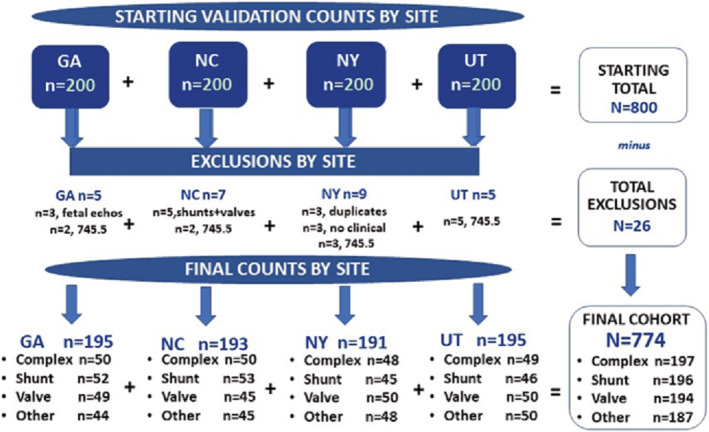

Data from the 4 sites (GA, NC, NY, UT) over a 3‐year project period, 2011 to 2013, were used for this validation. A total of 800 cases were planned for the validation study consisting of 200 cases from each of the 4 sites. Each site selected 50 cases from 4 mutually exclusive CHD anatomic groups as defined by the ICD code hierarchy (Figure 1) based on native anatomy: complex, shunt, valves, and “Other”, with each group further stratified by age: 1 to 10 years, 11 to 19 years, 20 to 64 years, >64 years (GA, NC, NY), or ages 11 to 19 years and 20 to 64 years (UT). Anatomic groups are described in Figure 1 and Data S1. To ensure a comparable distribution of cases by age, the data set was stratified by age group and a proportion was selected, based on the age distribution of the larger cohort, into each of the 4 mutually exclusive anatomic groups (Figure 2). Only those data sources where medical charts were accessible for review were eligible for inclusion. Cases identified only in administrative data, but without clinical records to review, were excluded. Of the total cases from the larger CHD surveillance project, 69.4% of GA's cases, 36.7% of NC's cases, 32.5% of NY's cases, and 97.6% of UT's cases were eligible for medical chart review and selection for the validation project.

Figure 2.

Cohort constructions and exclusions by site and congenital heart defect type.‡, §

‡ ICD‐9‐CM code 745.5 was omitted from the shunt group as it is used to indicate secundum atrial septal defect and patent foramen ovale, a normal variant. §“Other” congenital heart defect anatomic group consists of unspecific defects; congenital heart defect‐related ICD‐9‐CM codes and their assigned CHD anatomic grouping are displayed in Data S1. GA indicates Emory University in Georgia; ICD‐9‐CM, International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification; NC, Duke University in North Carolina; NY, New York State Department of Health; and UT, Utah.

During medical chart review, clinical investigators at each site supervised the review of predetermined variables abstracted from eHRs and noted the presence/absence of a true CHD based on review of CHD anatomy as determined by: (1) cardiac imaging, (2) clinical diagnosis by an outpatient or inpatient encounter with a pediatric or adult CHD provider, (3) CHD surgery, and (4) autopsy report. Included in this review, clinical investigators evaluated: (1) CHD case (Yes/No), and (2) CHD anatomic group correct (Yes/No). All available information from the eHR (including any data before 2011 or after 2013) was also used to confirm or refute the presence of CHD for each selected case. During chart review, information on type of CHD recorded, number of unique CHD codes per case, diagnostic tests received (ie, echocardiograms, cardiac catheterizations, cardiac surgery), autopsy reports or clinic notes, as well as date of diagnosis and type of provider who made the CHD diagnosis was evaluated. Additionally, demographic information including age, sex, race, and ethnicity was abstracted. With respect to race, small sample size for the “Other” race category necessitated this group be combined with the “unknown” race group (“Other” race includes American Indian/Alaskan Native, Asian, native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander, and multi‐racial).

The anatomic group of shunt and valve was excluded before case selection because it was assumed that if the case had codes for both of these anatomic groups, then the case was likely to be a true CHD case. Cases with code 745.5 in isolation or in combination with 746.89 or 746.9 were also excluded given the known poor PPV of these codes to represent a true CHD. 2 A total of 26 cases were excluded from analysis: 12 cases with code 745.5 in isolation or in combination with 746.89 or 746.9 among the sites that were found to be included in error after selection; 5 cases with both a shunt and valve diagnosis that were also erroneously selected for validation; 3 cases that did not have any clinical data to review; 3 cases that were inadvertently reviewed twice; and lastly, 3 cases whose only CHD code(s) were documented during an encounter for a fetal echocardiogram defined by the associated Current Procedural Terminology code (Figure 2). CHD codes occurring during performance of a fetal echocardiogram were excluded based on unpublished data showing that only 2.9% (4 out of 138) of women who had a CHD code solely associated with a fetal echocardiogram encounter actually had a true CHD, whereas the majority of CHD diagnosis codes documented during fetal echocardiogram encounters are intended for the fetus.

For GA, 200 cases, who resided in 1 of 5 metropolitan‐Atlanta counties (Clayton, Cobb, DeKalb, Fulton, Gwinnett) and were seen at least once at 1 of 3 health care systems with records available, were randomly selected for review. For the 1‐ to 10‐ and 11‐ to 19‐year‐old groups, 13 cases for each CHD anatomic class were selected, and for the 20‐ to 64‐ and >64‐year‐old groups, 12 cases for each anatomic class were selected. A total of 195 validated GA cases were retained and contributed to the pooled analyses (Figure 2).

For NC, 200 cases, each with at least 2 encounters, were randomly selected from eHRs at one data source which captured patients with CHD statewide. Similar to GA, 13 cases each for the 1‐ to 10‐ and 11‐ to 19‐year‐old groups, and 12 cases each for the 20‐ to 64‐ and >64‐year‐old groups were selected for review. A total of 193 validated NC cases were included for pooled analyses with other sites' data (Figure 2).

NY's sample of 200 cases was composed of patients who resided in 1 of 11 counties (Allegany, Bronx, Cattaraugus, Chautauqua, Erie, Genesee, Monroe, Niagara, Orleans, Westchester, Wyoming) in NY and who had a health care encounter at 1 of 2 clinical data sources. NY, like GA and NC, randomly selected 13 cases for each CHD anatomic class for 1‐ to 10‐year‐olds and 11‐ to 19‐year‐olds, and 12 cases for the 20‐ to 64‐year‐olds and >64‐year‐old groups. A total of 191 NY cases were retained and contributed to pooled analyses (Figure 2).

In UT, data sources included eHRs from 2 health care systems. While 200 CHD cases were randomly selected and stratified by anatomic groupings with 50 in each category, these classes were further stratified by 2 age groupings, 11‐ to 19‐year‐olds and 20‐ to 64‐year‐olds, with 25 cases each. Although the UT site did not collect data on individuals aged <10 or >64 years, they contributed a total of 195 validated cases to the pooled, multisite data set (Figure 2).

Statistical Analysis

PPVs for CHD were calculated overall, and by anatomic group, site, and number of unique CHD codes associated with a case. In addition, separate PPV analyses were conducted by sex, race, ethnicity, age group, and anatomic group. For age‐specific analyses, since UT did not contribute cases to the youngest age group, 1‐ to 10‐year‐olds, or the oldest age group category, >64‐year‐olds, UT was not included; age‐specific analyses included GA, NC, and NY only. For age‐specific analyses, PPV was first computed for age groups by sites, and then, also calculated omitting the “Other” CHD anatomic group, followed by omitting the >64‐year‐old age group, and finally, by omitting both the “Other” CHD anatomic group and the >64‐year‐old age group. Analyses for CHD anatomic group proceeded similarly except all 4 sites were included. Lastly, PPVs for having CHD (Yes/No) were calculated for several individual CHD ICD‐9‐CM codes and calculated by number of unique CHD codes.

Results

Table 1 shows number of cases by CHD anatomic groups, number of unique CHD‐related ICD‐9‐CM codes (single/multiple) recorded in encounters, followed by demographic characteristics of the sample, overall and by site. Slightly over half (51.16%, n=396) of the 774 cases were female, and 53.49% (n=414) had a single unique CHD‐related ICD‐9‐CM code recorded in the medical record. No significant differences were revealed for number of unique ICD‐9‐CM codes by site (X 2=7.14, P=0.0675) or sex by site (X 2=2.77, P=0.4278). No significant differences between age groups by site (GA, NC, and NY) in percent of individuals with one CHD‐related ICD‐9‐CM code were observed (X 2=4.04, P=0.6706). Across and by site, however, White race was most prevalent accounting for 66.67% of the sample, followed by Black and other/unknown race, 16.93% and 16.41%, respectively. The contribution of Black cases varied by site, with GA providing almost 40% of the cases, while UT contributed <5% (X 2=69.97, P<0.0001). The majority of the sample were non‐Hispanic (70.03%), and 18.86% of the sample's ethnicity was unknown (X 2=161.38, P<0.0001) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Cases Identified With a Congenital Heart Defect ICD‐9‐CM Code: Number of Codes and Demographics, Overall and by Sites

| Overall | Sites* | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GA | NC | NY | UT | ||

| CHD anatomic groups | |||||

| Noncomplex | |||||

| Complex | 197 | 50 | 50 | 48 | 49 |

| Shunt | 196 | 52 | 53 | 45 | 46 |

| Valve | 194 | 49 | 45 | 50 | 50 |

| “Other”† | 187 | 44 | 45 | 48 | 50 |

| Included in analyses | 774 | 195 | 193 | 191 | 195 |

| Excluded from data set | 26 | 5 | 7 | 9 | 5 |

| No. of unique CHD‐related ICD‐9‐CM codes for cases |

X 2 ‡ P value |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Single code | 414 (53.49%) | 114 (58.46%) | 94 (48.70%) | 111 (58.12%) | 95 (48.72%) |

7.14 P=0.0675 |

| Multiple unique codes | 360 (46.51%) | 81 (41.54%) | 99 (51.30%) | 80 (41.88%) | 100 (51.28%) | |

| Demographics | ||||||

| Age group (in y) | ||||||

| 1–10 | 50 (8.64%) | 18 (9.23%) | 11 (5.70%) | 21 (10.99) | … |

4.04 P=0.6706 |

| 11–19 | 156 (26.94%) | 52 (26.67%) | 52 (26.94%) | 52 (27.23%) | … | |

| 20–64 | 208 (35.92%) | 69 (35.38%) | 75 (38.86%) | 64 (33.51%) | … | |

| >64 | 165 (28.50%) | 56 (28.72%) | 55 (28.50%) | 54 (28.27%) | … | |

| Sex | ||||||

| Female | 396 (51.16%) | 105 (53.85%) | 94 (48.70%) | 91 (47.64%) | 106 (54.36%) |

2.77 P=0.4278 |

| Male | 378 (48.84%) | 90 (46.15%) | 99 (51.30%) | 100 (52.36%) | 89 (45.64%) | |

| Race | ||||||

| Black | 131 (16.93%) | 51 (26.15%) | 35 (18.13%) | 43 (22.51%) | <11 (−‐) | 69.97 P<0.0001 |

| White | 516 (66.67%) | 102 (52.31%) | 139 (72.02%) | 111 (58.12%) | 164 (84.10%) | |

| Other§ and unknown | 127 (16.41%) | 42 (21.54%) | 19 (9.84%) | 37 (19.37%) | 29 (14.87%) | |

| Ethnicity | ||||||

| Hispanic | 86 (11.11%) | 18 (9.23%) | <11 (−‐) | 44 (23.04%) | 17 (8.72%) |

161.38 P<0.0001 † |

| Non‐Hispanic | 542 (70.03%) | 132 (67.69%) | 173 (89.64%) | 142 (74.35%) | 95 (48.72%) | |

| Unknown | 146 (18.86%) | 45 (23.08%) | 13 (6.74%) | <11 (−‐) | 83 (42.56%) | |

Two numbers of unique CHD‐related ICD‐9‐CM codes (single code, multiple unique codes); 4 age groups (1–10, 11–19, 20–64, >64) for GA, NC, and NY only; UT omitted as cohort does not include 1–10 or >64‐year‐olds; 2 sexes (male, female); 3 races (Black, White, Other/unknown); and 3 ethnicities (Hispanic, non‐Hispanic, unknown). GA indicates Emory University in Georgia; ICD‐9‐CM, International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification; NC, Duke University in North Carolina; NY, New York State Department of Health; and UT, University of Utah.

Site‐specific percentages are column percentages; counts <11 not displayed.

“Other” CHD anatomic group consists of unspecific defects; CHD‐related ICD‐9‐CM codes and CHD anatomic groups are identified in Data S1.

X 2 applies to 5 Chi‐square analyses, which includes 4 sites: GA, NC, NY, UT, except the X 2 by age which omits UT: 2 number of unique CHD‐related ICD‐9‐CM codes (single code, multiple unique codes); 4 age groups (1–10, 11–19, 20–64, >64) for GA, NC & NY only; UT omitted as cohort does not include 1 to 10 or >64‐year‐olds; 2 sexes (male, female); 3 races (Black, White, Other/unknown); and 3 ethnicities (Hispanic, non‐Hispanic, unknown).

“Other” race includes American Indian/Alaskan Native, Asian, native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander, and multiracial.

The PPVs of having a CHD overall, by site, and by anatomic group with “Other” CHD anatomic group status (included/omitted) are seen in Table 2. PPV of having a CHD increased ≈ 10 percentage points from 76.36% (591/774; [95% CI, 73.20–79.31]) to 86.54% (508/587 [95% CI, 83.51–89.20]) after omitting the “Other” CHD anatomic group (X 2=22.28, P<0.0001). This pattern was also observed within each site: the increase in PPV ranged from 7.4% for NC (79.79%; 154/193 [95% CI, 73.43–85.22]) to 87.16%; 129/148 [95% CI, 80.68–92.09]) (ns)] to 14.6% for NY (70.68%; 135/191 [95% CI, 63.68–77.03] to 85.31%; 122/143 [95% CI, 78.43–90.67]); site‐specific Chi‐squares are for when “Other” CHD anatomic group was included versus omitted (Table 2). When all anatomic groups were combined regardless of whether “Other” CHD anatomic group was included or omitted, significant differences in PPV by site were not observed (X 2=5.15, P=0.1612 and X 2=0.35, P=0.9509, respectively) (Table 2). However, there was a significant difference in PPV for having a CHD by anatomic group. Of patients with a code for complex CHD, 89.85% (177/197 [95% CI, 84.76–93.69]) had a CHD (ie, 10.15% (20/197; 95% CI, 6.31–15.24) did not have CHD); corresponding PPV estimates were 86.73% (170/196 [95% CI, 81.17–91.15]) for shunt, 82.99% (161/194 [95% CI, 76.95–87.99]) for valve, and 44.39% (83/187 [95% CI, 84.76–93.69]) for “Other” CHD anatomic group (X 2=142.16, P<0.0001) (Table 2). In Table S1, for the complex and shunt categories, all sites reported PPVs >84.00%; for the valve category, UT's PPV was 76.0% (38/50 [95% CI, 61.83–86.94]) with other sites' PPVs >80% (89.80%; 44/49 [95% CI, 77.77–96.60]) for GA, 84.44% (38/45 [95% CI, 70.54–93.51]) for NC, and 82.00% (41/50 [95% CI, 68.56–91.42] for NY. In addition, the PPV of “Other” CHD anatomic group by site ranged from 27.08% (13/48 [95% CI, 15.28–41.85]) in NY to 55.56% (25/45 [95% CI, 40.00–70.36]) in NC (Table S1), and when “Other” CHD anatomic group was omitted, PPV for having a CHD did not differ significantly by anatomic group (X 2=3.96, P=0.1383) (Table 2). Lastly, when the PPVs of ICD‐9‐CM codes for correct CHD group assignment were assessed, among patients with ≥1 complex anatomic codes, 74.62% (147/197 [95% CI, 67.94–80.54]) were confirmed to have complex CHD (ie, 25.4% had a shunt, valve, “Other” CHD anatomic grouping, or no CHD); corresponding PPV estimates for identifying a patient with CHD in the correct CHD group were 84.18% (165/196; 95% CI, 87.31–88.99) for shunt, 80.41% (156/194; 95% CI, 74.12–85.75) for valve, and 29.41% (55/187; 95% CI, 22.99–36.50) for “Other” (X 2=168.02, P<0.0001) (Table S2).

Table 2.

PPV* of ICD‐9‐CM CHD Codes for Having a CHD Overall, by Site and by CHD Anatomic Group, with “Other”† CHD Anatomic Group Included and Omitted

| PPV* for having a CHD, overall |

X 2 † P value |

|

|---|---|---|

| “Other”‡ CHD included |

76.36% 591/774 [73.20–79.31] |

22.28 P<0.0001 § |

| “Other”‡ CHD omitted |

86.54% 508/587 [83.51–89.20] |

|

| PPV for having a CHD by site |

X 2 † P value |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GA | NC | NY | UT | ||

| “Other”‡ CHD included |

78.46% 153/195 [72.02–84.01] |

79.79% 154/193 [73.43–85.22] |

70.68% 135/191 [63.68–77.03] |

76.41% 149/195 [69.82–82.18] |

5.15 P=0.1612 |

| “Other”‡ CHD omitted |

87.42% 132/151 [81.05–92.25] |

87.16% 129/148 [80.68–92.09] |

85.31% 122/143 [78.43–90.67] |

86.21% 125/145 [79.50–91.37] |

0.35 P=0.9509 |

| PPV* for having a CHD by anatomic group |

X 2 † P value |

||||

| Complex | Noncomplex | “Other”‡ CHD included | “Other”‡ CHD omitted | ||

| Shunt§ | Valve | “Other”‡ | |||

| 89.85% | 86.73% | 82.99% | 44.39% | 142.16 P<0.0001‖ |

3.96 P=0.1383 |

| 177/197 [84.76–93.69] | 170/196 [81.17–91.15] | 161/194 [76.95–87.99] | 83/187 [37.14–51.81] | ||

ICD‐9‐CM indicates International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification; NC, Duke University in North Carolina; and PPV, positive predictive value.

95% CI presented within brackets for positive predictive values.

X 2 ‐ 5 Chi‐square analyses that include CHD overall, by site and by anatomic group: Overall CHD status (2: Yes/No) comparing when “Other” CHD anatomic group was included and omitted; by site—separate X 2s conducted when “Other” CHD anatomic group included and omitted: CHD status (2: Yes/No) by site (4: GA, NC, NY, and UT); by anatomic group ‐ separate X 2's conducted when: “Other” CHD anatomic group included: CHD status (2: Yes/No) by anatomic group (4: complex, shunt, valve, and “Other” CHD; and 2) “Other” CHD anatomic group omitted: CHD status (2: Yes/No) by anatomic group (3: complex, shunt, valve).

“Other” CHD anatomic group consists of unspecific defects; CHD‐related ICD‐9‐CM codes and assigned CHD anatomic group are displayed in Data S1.

ICD‐9‐CM code 745.5 was omitted from the shunt group as it is used to indicate secundum atrial septal defect and patent foramen ovale, a normal variant.

X 2 analyses that revealed significance group differences at the P<0.05 level or better.

Table 3 shows PPVs of having a CHD by number of unique CHD‐related ICD‐9‐CM codes overall and by anatomic group. Across all anatomic groups, when multiple unique codes were documented across 1 or multiple encounters, PPV was higher, 92.78% (334/360 [95% CI, 90.10–95.45]) compared with when a single CHD code was documented, 62.08% (257/414 [95% CI, 57.40–66.75]) (X 2=100.53, P<0.0001). This association was seen for anatomically complex CHD (X 2=29.88, P<0.0001), valve defects (X 2=13.05, P<0.0001), and the “Other” anatomic group (X 2=5.54, P=0.019). When >1 unique CHD‐related ICD‐9‐CM code appeared in the patient's eHR, PPV of having a CHD ranged from a low of 73.33% (11/15 [95% CI, 44.90–92.21]) in the “Other” CHD anatomic group to a high of 95.60% (152/159 [95% CI, 91.14–98.21]) in the complex group, compared with a range of 41.86% (72/172 [95% CI, 34.40–49.61]) in “Other” CHD anatomic group to 82.95% (73/88 [95% CI, 75.10–90.13]) in the shunt group for cases with a single CHD code.

Table 3.

PPV* of ICD‐9‐CM CHD Codes for Having a CHD By Number of Unique CHD Codes and Anatomic Group

|

Single CHD code |

Multiple unique CHD codes |

X 2 † P value |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| CHD anatomic group | |||

| Overall |

62.08% 257/414 [57.40–66.75] |

92.78% 334/360 [90.10–95.45] |

100.53 P<0.0001 |

| Complex |

65.79% 25/38 [48.65–80.37] |

95.60% 152/159 [91.14–98.21] |

29.88 P<0.0001 |

| Shunt† |

82.95% 73/88 [75.10–90.13] |

89.81% 97/108 [82.51–94.80] |

1.98 P=0.1590 |

| Valve |

75.00% 87/116 [66.11–82.57] |

94.87% 74/78 [87.39–98.59] |

13.05 P=0.0003 |

| “Other”‡ |

41.86% 72/172 [34.40–49.61] |

73.33% 11/15 [44.90–92.21] |

5.54 P=0.0186 |

CHD indicates congenital heart defect; ICD‐9‐CM, International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification; and PPV, positive predictive value.

95% CI presented within brackets [] for positive predictive values.

ICD‐9‐CM code 745.5 was omitted from the shunt group as it is used to indicate secundum atrial septal defect and patent foramen ovale, a normal variant.

“Other” CHD anatomic group consists of unspecific defects; CHD‐related ICD‐9‐CM codes and their assigned CHD anatomic grouping are displayed in Data S1.

Table 4 shows PPVs of having a CHD by 4 age groups, 1‐ to 10‐year‐olds, 11‐ to 19‐year‐olds, 20‐ to 64‐year‐olds, and >64‐year‐olds, by 3 sites (GA, NC, and NY). Compared with age groups ≤64 years whose PPVs were observed in the mid to lower 80% range (86.00%; 43/50 [95% CI, 73.26–95.62]) for 1‐ to 10‐year olds, 82.69% (129/156 [95% CI, 75.83–88.27]) for 11‐ to 19‐year‐olds, and 84.13% (175/208 [95% CI, 78.45–88.82]) for 20‐ to 64‐year‐olds), the PPV for those who were >64 years was significantly lower, 57.58% (95/165 [95% CI, 49.65–65.22]) (X 2=45.23, P<0.0001). When “Other” CHD anatomic group was omitted, the significant decreasing trend in PPV by age remained, with 95.24% (40/42 [95% CI, 83.84–99.42]) for 1‐ to 10‐year‐olds, 94.07% (111/118 [95% CI, 88.16–97.58]) for 11‐ to 19‐year‐olds, 93.90% (154/164 [95% CI, 89.07–97.04]) for 20‐ to 64‐year olds, and 66.10% (78/118 [95% CI, 56.81–74.56]) for those >64 years (X 2=58.82, P<0.0001). Table 4 also reveals the overall PPV of having CHD increased from 76.34% (442/579 [95% CI, 72.66–79.74]) when all 4 age and CHD anatomic groups were included to 94.14% (305/324 [95% CI, 72.66–79.74]) after both “Other” CHD anatomic group and the >64‐year‐olds were omitted (X 2=46.04, P<0.0001). However, when the >64‐year‐olds were excluded regardless of whether or not the “Other” CHD anatomic group was retained in the analysis, no trend in PPV for having a CHD by age was observed (including “Other”: X 2=0.34, P=0.8451 and excluding “Other”: X 2=0.11, P=0.9467, respectively). In addition, PPV for having a CHD showed no significant group differences whether “Other” CHD anatomic group was included or omitted for sex (X 2=1.16, P=0.2809 and X 2=1.48, P=0.2238, respectively), for race (X 2=5.62, P=0.0601 and X 2=0.35, P=0.8382, respectively), or for ethnicity (X 2=1.24, P=0.5381 and X 2=2.84, P=0.24, respectively) (Table S3).

Table 4.

PPV* of ICD‐9‐CMCHD Codes† for Having a CHD, Overall and by Age Group, for Three Sites with “Other”‡ CHD Anatomic Group Included and Omitted

| PPV* for having a CHD, for 4 age groups |

P value |

|

|---|---|---|

| “Other”‡ CHD included |

76.34% 442/579 [72.66–79.80] |

17.19 P<0.0001 |

| “Other”‡ CHD omitted |

86.65% 383/442 [83.12–89.68] |

|

| PPV* for having CHD by age groups |

P value |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1–10 y | 11–19 y | 20–64 y | >64 y | All 4 age groups | Three youngest age groups | |

| “Other”‡ CHD included |

86.00% 43/50 [73.26–95.62] |

82.69% 129/156 [75.83–88.27] |

84.13% 175/208 [78.45–88.82] |

57.58% 95/165 [49.65–65.22] |

45.23 P<0.0001 |

0.34 P=0.8451 |

| “Other”‡ CHD omitted |

95.24% 40/42 [83.84–99.42] |

94.07% 111/118 [88.16–97.58] |

93.90% 154/164 [89.07–97.04] |

66.10% 78/118 [56.81–74.56] |

58.82 P<0.0001 |

0.11 P=0.9467 |

| PPV* for having A CHD, for 3 age groups |

P value |

|

|---|---|---|

| “Other”‡ CHD included |

83.82% 347/414 [79.91–87.23] |

18.80 P<0.0001 |

| “Other”‡ CHD omitted |

94.14% 305/324 [90.99–96.43] |

|

X 2 for having a CHD when all 4 age groups and CHD anatomic groups were included (PPV=76.34%) compared with when >64‐year‐olds and “Other” CHD anatomic group were omitted (PPV=94.14%) was X 2=46.04, P<0.0001. CHD indicates congenital heart defect; ICD‐9‐CM, International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification; and PPV, positive predictive value.

95% CI presented within brackets [] for positive predictive values.

ICD‐9‐CM code 745.5 was omitted from the shunt group as it is used to indicate secundum atrial septal defect and patent foramen ovale, a normal variant.

“Other” CHD anatomic group consists of unspecific defects; CHD‐related ICD‐9‐CM codes and assigned CHD anatomic group are displayed in Data S1.

UT not included in these analyses as age groups 1–10 and >64 years were not reported.

PPV of having a CHD for individual ICD‐9‐CM CHD codes with sufficient case numbers are presented in Table 5. In isolation, tetralogy of Fallot (745.2) had a PPV of 84.2% for having a CHD, ventricular septal defect (745.4) had a PPV of 89.1%, and patent ductus arteriosus had a PPV of 81.3%. However, unspecified anomaly of heart (746.9) had a PPV of 42.2% and other congenital anomaly of heart (746.89) had a PPV of 23.1% for having a CHD. PPV for each of these individual ICD‐9‐CM CHD‐related codes were all >90.0% when multiple unique ICD‐9‐CM CHD‐related codes were identified.

Table 5.

Positive Predictive Value of Specific CHD ICD‐9‐CM Codes for Having CHD by Number of Select Unique CHD Codes

| ICD‐9‐CM code | Description of ICD‐9‐CM code | CHD anatomic group | Patients, n | PPV for having CHD | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Single CHD code |

Multiple unique CHD codes |

Total # with code | Single CHD code | Multiple Unique CHD codes | Total % with code | |||

| 745.2 | Tetralogy of Fallot | Complex | 19 | 53 | 72 | 84.2% | 94.3% | 91.7% |

| 745.4 | Ventricular septal defect | Shunt | 64 | 93 | 157 | 89.1% | 94.6% | 92.4% |

| 747.0 | Patent ductus arteriosus | Shunt | 16 | 36 | 52 | 81.3% | 94.4% | 90.4% |

| 746.4 | Bicuspid aortic valve and congenital aortic valve insufficiency | Valve | 61 | 37 | 98 | 82.0% | 97.3% | 87.8% |

| 746.02 | Congenital pulmonary valve stenosis | Valve | 10 | 37 | 47 | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% |

| 746.3 | Congenital stenosis of aortic valve | Valve | 16 | 24 | 40 | 87.5% | 95.8% | 92.5% |

| 747.1 | Coarctation of aorta | Valve | 12 | 26 | 38 | 66.7% | 100.0% | 89.5% |

| 746.9 | Unspecified anomaly of heart | Other | 45 | 89 | 134 | 42.2% | 94.4% | 76.9% |

| 746.89 | Other congenital anomaly of heart | Other | 26 | 39 | 65 | 23.1% | 92.3% | 64.6% |

| V13.65 | Personal history of corrected congenital Malformation of heart and circulatory system | Other | 11 | 38 | 49 | 54.5% | 92.1% | 83.7% |

| 746.85 | Coronary artery anomaly | Other | 26 | 12 | 38 | 61.5% | 91.7% | 71.1% |

| 746.87 | Malposition of heart and cardiac apex | Other | 12 | 15 | 27 | 33.3% | 93.3% | 66.7% |

| 747.29 | Other anomaly of aorta | Other | 14 | 12 | 26 | 35.7% | 91.7% | 61.5% |

CHD indicates congenital heart defect; ICD‐9‐CM, International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification; and PPV, positive predictive value.

Discussion

The primary aim of this validation project was to evaluate the PPV of ICD‐9‐CM codes and a code‐based anatomic hierarchy for identifying CHD cases, and secondarily, to assess the PPV of these codes by anatomic groups. Overall, 76.36% of patients with ≥1 CHD‐related ICD‐9‐CM codes had CHD. Across sites, of those with codes falling into the complex anatomic group, 86.00% to 92.00% had CHD, and only 27.08% to 55.56% of those with codes falling into the “Other” anatomic group had CHD. The PPV of ICD‐9‐CM codes for CHD was significantly higher for cases aged ≤64 years (83.82%) compared with those >64 years (57.58%). Furthermore, for cases aged ≥64 years, PPV of having CHD by anatomic group revealed a low PPV of 36.17% (17/47 [95% CI, 22.67–49.91]) for the “Other” anatomic group and a high of 73.17% (30/41 [95% CI, 59.61–85.78]) for valve lesions. This is consistent with findings from a previous study assessing the accuracy of code 745.5 to predict true atrial septal defects, in which younger patients, ages 11 to 20 years, were more likely to have a true atrial septal defect (64.3%) compared with those aged 21 to 40 years (23.7%) or 41 to 64 years (19.0%) (P<0.001). 2 Using ICD codes in a “rule‐out CHD” manner and incorrect coding for CHD may play a role in the low PPV for older CHD cases. Age‐related changes in valve morphology and function may mistakenly be coded as CHD. The “Other” CHD category includes non‐specific CHD codes such as “other congenital anomaly of the heart” that may be used inappropriately, for example, when ordering studies to investigate heart murmurs and symptoms of heart failure in older patients.

When examining the accuracy of ICD‐9‐CM‐based native CHD anatomy group, about two thirds of cases across all sites were categorized into the correct anatomic group and the other one‐third either did not have CHD or were categorized into the wrong group based on an incorrect code. The PPV of ICD‐9‐CM codes contained in eHR systems for identifying that a case truly has CHD of the indicated anatomic group ranged from 84.18% for shunt defect codes, excluding 745.5, to 29.41% for the “Other” CHD anatomic code group. Nonspecific codes in the “Other” CHD category may have a low PPV because they may have been used as “rule‐out” codes when ordering diagnostic tests or were misused for an acquired heart condition. For example, if a patient has low blood oxygen saturations, then a “rule out CHD” code such as 746.9 (unspecified congenital anomaly of heart) may be used to assess for CHD. A comparative PPV analysis for case classification revealed a lower PPV for single versus multiple code classification, 62.08% versus 92.78%, respectively (Table 3). While requiring multiple codes for case inclusion may likely avoid “rule out” code misclassification, it often comes at the expense of losing true CHD cases. In this study, relying on multiple codes alone would have resulted in reducing sensitivity by 33.2% (257/774) because 257 single‐coded true CHD cases would be excluded. Additionally, reasons for the assignment of an incorrect anatomic group may also include coding errors such as when a code in the 745.xx to 747.xx ICD‐9‐CM group has a decimal dropped, leading to conversion from 745 to 745.0, a code for truncus arteriosus (745.0), rather than an intended code, for instance 745.4, ventricular septal defect. Misuse of CHD codes may occur in other ways. For example, this study included 3 cases that were coded as “other septal defect” rather than ventricular septal defect. These coding errors highlight that nonspecific CHD ICD‐9‐CM codes may actually represent specific and true CHD that could have been better captured by a more specific CHD code.

Of the 774 total cases, 414 had a single CHD code and 360 had multiple unique CHD codes. Patients with more than one unique CHD code were more likely to have CHD, and this increase in PPV was significant for the complex and valve anatomic groups. Certain ICD‐9‐CM codes that frequently occur in combination with other CHD codes had PPVs >90%. For instance, tetralogy of Fallot (745.2) and ventricular septal defect (745.4) all had high PPVs for CHD in combination with other CHD codes.

Prior studies have also examined whether complexity of disease may play a role in the accuracy of coding in administrative data. Steiner et al. (2017) found certain complex CHD codes, such as tetralogy of Fallot and truncus arteriosus, performed well. 9 Khan et al. (2018) found that PPV of moderate or complex CHD codes for CHD was higher compared with simple shunt or valve defects or when coupled with other factors such as age, an encounter with an adult CHD provider, an echocardiogram or ECG compared with noncomplex CHD. 1 The current validation project found that the complex, shunt, and valve groups had higher PPV than the “Other” CHD group, supporting the conclusion that more specific diagnoses have a higher PPV for true CHD.

While this study did not examine sensitivity of administrative databases, other studies have demonstrated poor identification of CHD in state‐specific administrative databases for pediatric patients. 3 Cronk et al. (2003) investigated the sensitivity of ICD‐9 codes for identifying individuals with CHD in 4 administrative databases in Wisconsin and found that only 57.9% of CHD cases identified at Children's Hospital of Wisconsin were identified by ICD‐9 codes and/or a CHD checkbox indicative of the presence of CHD in any state database; a total of 216 cases (57.9%) of the 373 total cases were identified by a CHD ICD‐9 code in at least one of the 4 state databases. 10 Almost 62% (231 of 373) had a single CHD diagnosis and 91% (339 of 373) had 1 or 2 CHD diagnoses. Lack of reporting oversight and classification problems were thought to contribute to inadequate identification of CHD from such data sets.

Ideally, constructing an algorithm that utilizes data from administrative and eHRs will help to identify true CHD cases with improved accuracy and sensitivity. Machine learning is one possibility to improve both the PPV and sensitivity of CHD codes for CHD, and specific CHD type, based on ICD codes and other variables from clinical and administrative data sets, using the most predictive factors, while reducing the false negative rate. Restricting analyses to certain ICD codes and age categories may also improve the PPV. As a result of the current findings and previous research, 2 , 11 researchers may consider excluding the following codes from administrative data sets to improve the PPV for analyses seeking to study CHD:

ICD‐9‐CM and anatomically equivalent ICD‐10‐CM codes that code for conditions other than heart defects, including congenital heart block (746.86, Q24.6), pulmonary arteriovenous malformation (747.32, Q25.72), absent/hypoplastic umbilical artery (747.5, Q27.0), other anomalies of peripheral vascular system (747.6x, Q27.9), and other specified anomalies of circulatory system (747.8x, Q28.8). These codes were also excluded in the surveillance methodology. 5 , 6

The “Other” CHD anatomic group (as noted in Figure 1 and Data S1) and nonspecific ICD‐9‐CM codes and the equivalent ICD‐10‐CM codes including: other specified congenital anomalies of heart 746.8 (Q24.8), obstructive anomalies of heart, not elsewhere classified 746.84, coronary artery anomaly 746.85 (Q24.5), malposition of heart and cardiac apex 746.87 (Q24.0), other specified congenital anomalies of heart 746.89 (Q24.8), unspecified congenital anomaly of heart 746.9 (Q24.9), other congenital anomalies of aorta 747.2 (Q25.49), anomaly of aorta, unspecified 747.20 (Q25.40), anomalies of aortic arch 747.21, other anomalies of aorta 747.29 (Q25.49), congenital anomalies of great veins 747.4 (Q26.1), anomaly of great veins, unspecified 747.40 (Q26.9), other anomalies of great veins 747.49 (Q26.8), unspecified anomaly of circulatory system 747.9 (Q28.9, personal history of [corrected] congenital malformations of heart and circulatory system V13.65 (Z87.74)

Patent foramen ovale / atrial septal defect 745.5 / Q21.1 alone or in combination with the “Other” CHD category.

Codes found in combination are likely to be more accurate than an isolated CHD code, though 53% (414/774) of the cases in this validation project had a single unique CHD code. Therefore, it is suggested to avoid excluding cases with single CHD codes from algorithms and analyses; doing so could result in missed cases and lack of generalizability. Additionally, severity of CHD is not indicated by the number of unique CHD codes applied to an individual. It is notable that eliminating the ICD‐9‐CM codes above, or eliminating the >64‐year‐old group, will improve the PPV of CHD, but will also exclude a substantial number of true CHD cases. Certain codes are more likely to identify true CHD cases than others. Even though the vast majority of cases with complex and moderate CHD codes (80%–90%) have CHD, there remains about 1 in 4 or 5 cases who may either not have CHD or have a different severity type than what is coded. Sufficiently detailing how CHD is defined when using administrative data as well as understanding and documenting its limitations will improve the generalizability of the findings to the CHD population.

Limitations

The selected cases used in this analysis came from health care centers at locations where records could be reviewed. Thus, there was possible selection bias towards having true CHD, which might overestimate the PPV. However, using data from 2011 to 2013 may lead to an underestimation of PPV compared with more recent years as eHR use has become more standard. Coding may vary by data source, year, and individuals who document the code (medical versus billing department staff), potentially limiting broad applicability to other data sets. Coding practices vary across both regions and medical centers, which is both a strength and limitation of our paper. Our data set used ICD‐9‐CM codes, which can be mapped to ICD‐10‐CM codes. However, differences in coding practices may vary between the ICD‐9‐CM and ICD‐10‐CM eras, thus making our results not directly applicable to ICD‐10‐CM based data sets. For the individual ICD‐9‐CM codes assessed, the reported PPV is for having CHD (Yes/No) and we were unable to examine PPV for whether the case had the specific CHD documented. We did not have access to false negatives cases in the data available and thus could not calculate sensitivities of CHD ICD‐9‐CM codes.

Conclusions

This validation study using data from 4 sites affiliated with the CDC's Surveillance of Congenital Heart Disease Across the Lifespan project revealed that ICD‐9‐CM codes accurately classify patients with true CHD in the majority of cases labeled as complex, shunt, and valve. The PPV of “Other” non‐specific CHD ICD‐9‐CM codes was low and may not reflect true CHD. When >1 unique CHD code is associated with a case, the PPV for CHD increases. CHD codes had higher PPV in younger compared with older CHD cases. Further evaluation and algorithm development may help inform and improve the identification of CHD cases when administrative data sets are used.

Sources of Funding

This work was supported by the CDC Cooperative Agreement, Surveillance of Congenital Heart Defects Across the Lifespan; Funding Opportunity Announcements #DD15‐1506. The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the CDC.

Disclosures

None.

Supporting information

Data S1

Tables S1–S3

Acknowledgments

We thank the Pedigree and Population Resource of Huntsman Cancer Institute, University of Utah (funded in part by the Huntsman Cancer Foundation) for its role in the ongoing collection, maintenance, and support of the Utah Population Database. We also acknowledge partial support for the Utah Population Database through grant P30 CA2014 from the National Cancer Institute, University of Utah, and from the University of Utah's program in Personalized Health and Center for Clinical and Translational Science. We thank the University of Utah Center for Clinical and Translational Science (funded by National Institutes of Health Clinical and Translational Science Awards), the Pedigree and Population Resource, University of Utah Information Technology Services and Biomedical Informatics Core for establishing the Master Subject Index between the Utah Population Database, the University of Utah Health Sciences Center and Intermountain Healthcare. This analysis has undergone replication by Anaclare Sullivan.

Supplemental Material is available at https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/suppl/10.1161/JAHA.121.024911

For Sources of Funding and Disclosures, see page 12.

References

- 1. Khan A, Ramsey K, Ballard C, Armstrong E, Burchill LJ, Menashe V, Pantely G, Broberg CS. Limited accuracy of administrative data for the identification and classification of adult congenital heart disease. J Am Heart Assoc. 2018;7:e007378. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.117.007378 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Rodriguez FH III, Ephrem G, Gerardin JF, Raskind‐Hood C, Hogue C, Book W. The 745.5 issue in code‐based, adult congenital heart disease population studies: relevance to current and future ICD‐9‐CM and ICD‐10‐CM studies. Congenital Heart Dis. 2018;13:59–64. doi: 10.1111/chd.12563 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Agarwal S, Sud K, Menon V. Nationwide hospitalization trends in adult congenital heart disease across 2003–2012. J Am Heart Assoc. 2016;5:e002330. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.115.002330 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Broberg C, McLarry J, Mitchell J, Winter C, Doberne J, Woods P, Burchill L, Weiss J. Accuracy of administrative data for detection and categorization of adult congenital heart disease patients from an electronic medical record. Pediatr Cardiol. 2015;36:719–725. doi: 10.1007/s00246-014-1068-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Glidewell J, Book W, Raskind‐Hood C, Hogue C, Dunn JE, Gurvitz M, Ozonoff A, McGarry C, Van Zutphen A, Lui G, et al. Population‐based surveillance of congenital heart defects among adolescents and adults: surveillance methodology. Birth Defects Res. 2018;110:1395–1403. doi: 10.1002/bdr2.1400 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Glidewell JM, Farr SL, Book WM, Botto L, Li JS, Soim AS, Downing KF, Riehle‐Colarusso T, D'Ottavio AA, Feldkamp ML, et al. Individuals aged 1–64 years with documented congenital heart defects at healthcare encounters, five U.S. surveillance sites, 2011–2013. Am Heart J. 2021;238:100–108. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2021.04.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Marelli AJ, Mackie AS, Ionescu‐Ittu R, Rahme E, Pilote L. Congenital heart disease in the general population: changing prevalence and age distribution. Circulation. 2007;115:163–172. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.627224 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Marelli AJ, Ionescu‐Ittu R, Mackie AS, Guo L, Dendukuri N, Kaouache M. Lifetime prevalence of congenital heart disease in the general population from 2000 to 2010. Circulation. 2014;130:749–756. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.113.008396 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Steiner JM, Kirkpatrick JN, Heckbert SR, Habib A, Sibley J, Lober W, Randall J, Curtis JR. Identification of adults with congenital heart disease of moderate or great complexity from administrative data. Congenital Heart Dis. 2017;13:65–71. doi: 10.1111/chd.12524 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Cronk CE, Malloy ME, Pelech AN, Miller RE, Meyer SA, Cowell M, McCarver DG. Completeness of state administrative databases for surveillance of congenital heart disease. Birth Defects Res Part A: Clin Mol Teratol. 2003;67:597–603. doi: 10.1002/bdra.10107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Lui GK, McGarry C, Bhatt A, Book W, Riehle‐Colarusso TJ, Dunn JE, Glidewell J, Gurvitz M, Hoffman T, Hogue C, et al. Surveillance of congenital heart defects among adolescents at three U.S. sites. Am J Cardiol. 2019;124:137–143. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2019.03.044 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data S1

Tables S1–S3