Abstract

Background

The endothelium is essential for maintaining vascular physiological homeostasis and the endothelial injury leads to the neointimal hyperplasia because of the excessive proliferation of vascular smooth muscle cells. Endothelial Foxp1 (forkhead box P1) has been shown to control endothelial cell (EC) proliferation and migration in vitro. However, whether EC‐Foxp1 participates in neointimal formation in vivo is not clear. Our study aimed to investigate the roles and mechanisms of EC‐Foxp1 in neointimal hyperplasia.

Methods and Results

The wire injury femoral artery neointimal hyperplasia model was performed in Foxp1 EC‐specific loss‐of‐function and gain‐of‐function mice. EC‐Foxp1 deletion mice displayed the increased neointimal formation through elevation of vascular smooth muscle cell proliferation and migration, and the reduction of EC proliferation hence reendothelialization after injury. In contrast, EC‐Foxp1 overexpression inhibited the neointimal formation. EC‐Foxp1 paracrine regulated vascular smooth muscle cell proliferation and migration via targeting matrix metalloproteinase‐9. Also, EC‐Foxp1 deletion impaired EC repair through reduction of EC proliferation via increasing cyclin dependent kinase inhibitor 1B expression. Delivery of cyclin dependent kinase inhibitor 1B‐siRNA to ECs using RGD (Arg‐Gly‐Asp)‐peptide magnetic nanoparticle normalized the EC‐Foxp1 deletion‐mediated impaired EC repair and attenuated the neointimal formation. EC‐Foxp1 regulates matrix metalloproteinase‐9/cyclin dependent kinase inhibitor 1B signaling pathway to control injury induced neointimal formation.

Conclusions

Our study reveals that targeting EC‐Foxp1‐matrix metalloproteinase‐9/cyclin dependent kinase inhibitor 1B pathway might provide future novel therapeutic interventions for restenosis.

Keywords: cyclin dependent kinase inhibitor 1B (Cdkn1b), matrix metalloproteinase‐9 (MMP9), neointimal formation, transcription factor forkhead box protein P1 (Foxp1)

Subject Categories: Vascular Disease, Basic Science Research, Growth Factors/Cytokines

Nonstandard Abbreviations and Acronyms

- Cdkn1b

cyclin dependent kinase inhibitor 1B

- ECs

endothelial cells

- Foxp1

Forkhead box P1

- HUVECs

human umbilical vein endothelial cells

- MMP9

matrix metalloproteinase‐9

- RT‐qPCR

real‐time quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction

- VSMCs

vascular smooth muscle cells

Clinical Perspective.

What Is New?

Endothelial‐specific knockout of Foxp1 (forkhead box P1) increases neointimal formation after injury, and endothelial Foxp1 overexpression inhibits neointimal formation.

EC (endothelial cell)‐Foxp1 paracrine regulates vascular smooth muscle cell proliferation and migration via targeting matrix metalloproteinase‐9.

EC‐Foxp1 deletion impaired EC repair through reduction of EC proliferation via increasing cyclin dependent kinase inhibitor 1B expression.

What Are the Clinical Implications?

Percutaneous coronary intervention causes injury to the vascular endothelium leading to incomplete reendothelialization that is usually dysfunctional, and which stimulates the proliferation and migration of smooth muscle cells, thereby promoting neointimal hyperplasia.

EC‐Foxp1‐matrix metalloproteinase‐9/cyclin dependent kinase inhibitor 1B pathway has the potential to provide future novel therapeutic interventions for restenosis.

Percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) is now a well‐established treatment for coronary artery disease, which is the major cause of mortality worldwide. 1 , 2 However, restenosis remains a fundamental complication of any percutaneous intervention and although stenting dramatically reduces restenosis, it does not entirely eliminate it. Management of patients with in‐stent restenosis remains an important clinical problem.

The pathophysiologic mechanism of restenosis is heterogeneous and mainly attributed to the aggressive neointimal proliferation from dysregulation of endothelial cells (ECs) and excess vascular smooth muscle cell (VSMC) proliferation and migration. 3 , 4 , 5 , 6 Because ECs play an important role in the proliferation and migration of VSMC in the process of intimal hyperplasia, the cellular and molecular pathways that regulate this process are needed to further investigated.

The healthy endothelium communicates with the underlying VSMCs to control the homeostasis of mature vessels. 6 , 7 PCI‐induced vascular injury results in the release of growth factors, cytokines by activated endothelium, which stimulates the aberrant proliferation and migration of smooth muscle cells (SMCs), and then leads to the formation of neointima and restenosis. 4 , 6 , 8 , 9 Our previous study showed that endothelial GATA zinc finger transcription factor family‐6 transcriptionally regulated platelet‐derived growth factor‐B expression to control VSMC proliferation and migration in a paracrine manner contributing to neointimal formation, 10 which further corroborate the importance of EC‐VSMC communications.

PCI stent deployment damaged the vascular endothelium and caused the repopulation of the denuded regions from adjacent ECs. 11 , 12 The incomplete reendothelialization or the regenerated endothelium might have impaired function promoting in‐stent restenosis. 7 , 8 , 11 , 12 The drug‐eluting stents efficiently inhibit neointimal hyperplasia through decreasing cell proliferation, but also restrain reendothelialization of the vessel where the stent is deployed, hence leading to late in‐stent restenosis and thrombosis events. A study reported that increase of endothelial proliferation or reendothelialization after injury correlated with the diminished intimal hyperplasia. 13 However, the molecular mechanisms regulating reendothelialization and the function of repaired endothelium are incompletely understood.

Foxps (forkhead box proteins P) are large modular transcription repressors that bind to a motif sequence (5′‐TRTTTRY‐3′) on the target gene. 14 , 15 Foxp1 is highly expressed in vascular ECs and our previous study showed Foxp1 expression in endocardium repressed Sox17 expression, which, through regulation of b‐catenin activity, controlled Fgf16/20 expression and influenced cardiomyocyte proliferation, and further ventricular myocardial development. 16 Our recent study reported that Foxp1 repressed endothelial transforming growth factor‐β signals to inhibit fibroblast proliferation and transformation to myofibroblasts, and further attenuated pathological cardiac remodeling and improved cardiac function. 17 Therefore, we hypothesize that Foxp1 might regulate endothelial function to control VSMC phenotypic change and influence wire injury EC denuded induced neointimal formation. Also, Foxp1 was reported to be essential for endothelial angiogenic function and silencing of Foxp1 in vitro resulted in inhibition of proliferation, tube formation, and migration of cultured ECs. 18 Hence, we explored the roles and mechanisms of Foxp1 in injury‐induced reendothelialization for neointimal formation in vivo.

Our study found that Foxp1 deletion in ECs resulted in significant increase of VSMC proliferation/migration and neointimal formation upon wire injury and we identified matrix metalloproteinase‐9 (MMP9) as a Foxp1 direct target gene, and the EC‐Foxp1‐MMP9 pathway regulated VSMC proliferation and migration. Also, EC‐Foxp1 deletion mice exhibited a significant decrease of reendothelialization following femoral artery injury, and a cell cycle regulating gene, cyclin dependent kinase inhibitor 1B (Cdkn1b), was identified as the Foxp1 target gene. Delivery of Cdkn1b‐siRNA using RGD (Arg‐Gly‐Asp)‐peptide magnetic nanoparticle with high endothelial cell affinity reversed the EC‐Foxp1 deletion‐mediated impaired EC repair and attenuated the neointimal formation. Contrary to EC‐Foxp1 loss‐of‐function mice, EC‐Foxp1 gain‐of‐function mice were protected against neointimal hyperplasia with increase of EC proliferation and decrease of VSMC proliferation and migration. The results of this study expand our understanding of wire injury EC denudation induced neointimal hyperplasia and will help to identify potential therapeutic targets of endothelial signals for future therapeutic interventions for restenosis.

METHODS

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. See Data S1 for detailed Materials and Methods.

Animals

All animal procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at Tongji University. The conditional Foxp1 loss‐of‐function (Foxp1 flox/flox ) 16 and gain‐of‐function mice 19 were crossed with tamoxifen‐inducible Cdh5 promoter‐driven Cre line (Cdh5‐Cre ERT2 ) 20 to generate EC‐specific Foxp1 loss‐ and gain‐of‐function mice, Foxp1 ECKO and Foxp1 ECTg mice. Wire injury‐induced femoral arterial neointima formation mouse model was performed with a detailed description in Data S1. Details of lentiviral‐MMP9‐shRNA infection in vivo and delivery of Cdkn1b‐siRNA to endothelial cells using RGD (Arg‐Gly‐Asp)‐pepetide magnetic nanoparticle, hematoxylin and eosin staining, and immunostaining, were also provided in Data S1.

Molecular Methods

The details of real‐time quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT‐qPCR), immunoblotting, expression vectors, cell culture/transfection and proliferation/migration assay, lentiviral package, isolation of mouse lung endothelial cells, RNA high‐throughput sequencing methods were provided in Data S1, as well as chromatin immunoprecipitation assay, and luciferase reporter assay.

Statistical Analysis

Continuous variables were presented as mean±SEM, and the statistical analysis was performed using SPSS 16.0 Statistics. Unpaired 2‐tailed Student t‐test was used for comparisons between 2 groups, and 1‐way ANOVA followed by the post‐hoc Tukey multiple comparison analysis for multiple groups. Two‐way repeated‐measures ANOVA was used for comparisons between multiple groups when there were 2 experimental factors. P<0.05 means statistically significant.

RESULTS

Genetic Inhibition of Foxp1 in Endothelium Promotes Neointimal Formation Following Injury through Increase of VSMC Proliferation and Migration

Vascular endothelial dysfunction plays a vital role in the pathogenesis of vascular diseases including neointimal thickening and atherosclerosis. EC activation was reported to be associated with reduced Foxp1–dependent transcriptional activation. 17 , 21 , 22 , 23 We found a 54% reduction of Foxp1 expression in endothelium of injured femoral arteries by RT‐qPCR (P=0.0252) (Figure S1A). Immunostaining on injured femoral arteries also confirmed the decrease of Foxp1 expression in endothelium (Figure S1B). These data indicated that endothelial Foxp1 (EC‐Foxp1) might participate in wire‐injury induced neointimal formation. To confirm the role of EC‐Foxp1 in neointimal formation after wire injury, EC‐Foxp1 deletion mice (Foxp1 ECKO ) were generated and RT‐qPCR demonstrated 70% reduction in Foxp1 mRNA level in ECs from Foxp1 ECKO mice (P=0.001), which was further confirmed by immunostaining and Western blot (Figure 1A).

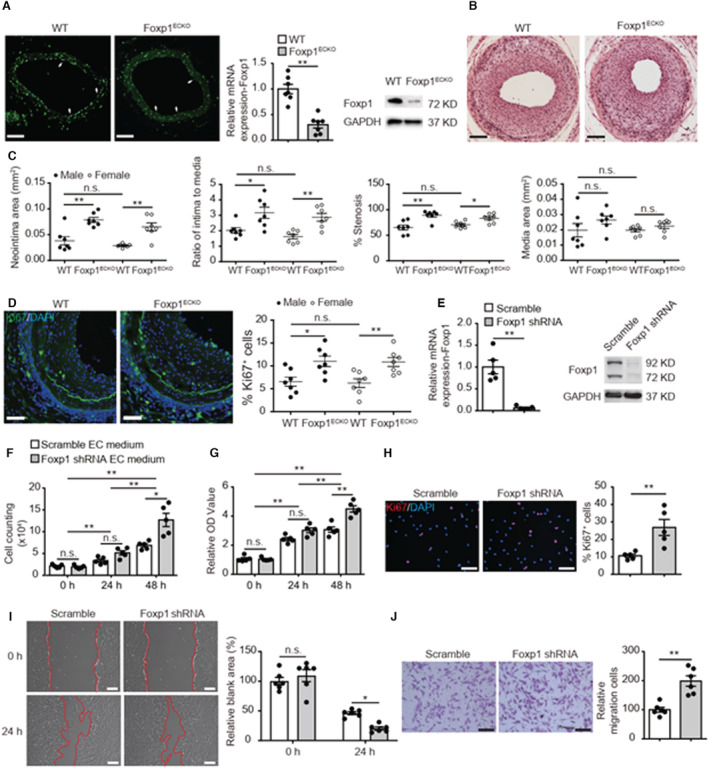

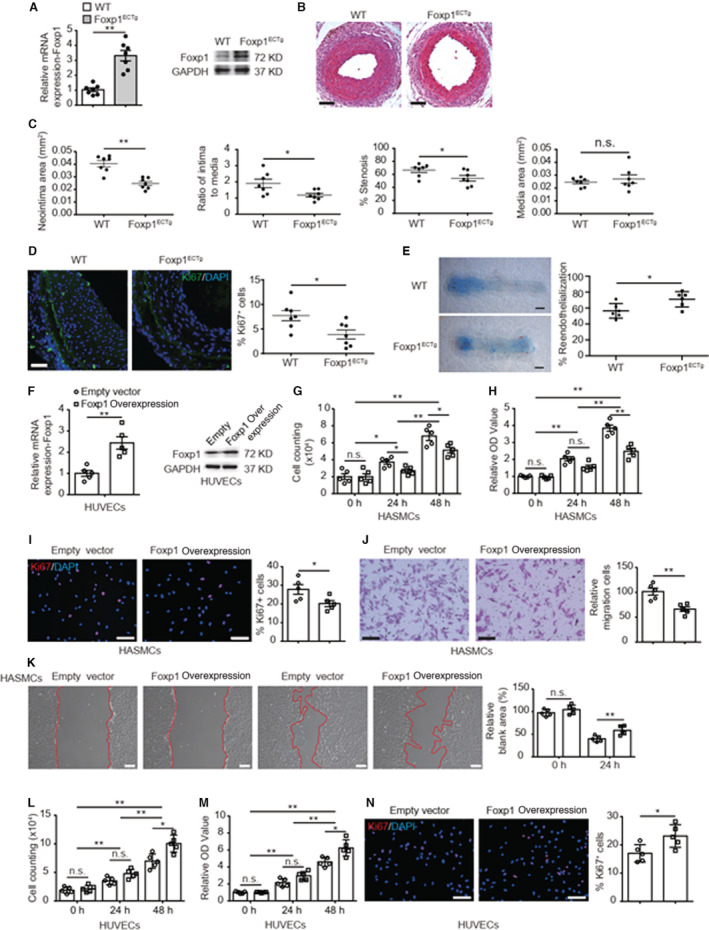

Figure 1. Genetic deletion of endothelial cell (EC)‐Foxp1 (forkhead box P1) increases neointimal formation through promoting vascular smooth muscle cell proliferation and migration.

A, Foxp1 immunostaining (left) in femoral artery, real‐time quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (middle) and Western blot (right) in vascular ECs of EC‐Foxp1 deletion mice (Foxp1 ECKO , Foxp1 flox/flox ;Cdh5Cre ERT2 ) and wild‐type mice (n=7). White arrowheads indicating Foxp1 staining in ECs. B and C, Foxp1 ECKO mutant mice of both male and female sex exhibit increased neointimal formation at 28 days after femoral artery wire injury compared with wild‐type littermate mice, with representative images (B) and quantification of neointima area, intima to media ratio, percentage stenosis and media area (C) (n=7 females/7 males for each group). D, Foxp1 ECKO mutant mice exhibit significantly increased cell proliferation in the neointima by Ki67 immunostaining, with representative images (left) and quantification data (right) (n=7 females/7 males for each group). E, Significant reduction of Foxp1 expression in human umbilical vein ECs treated with lentiviral Foxp1‐shRNA is confirmed by real‐time quantitative reverse transcription (left) and Western blot (right) compared with human umbilical vein ECs with control scramble‐shRNA (n=5). F through H, Condition medium from Foxp1 knockdown human umbilical vein ECs significantly increases human aortic smooth muscle cell proliferation assessed by cell counting (F), 3‐(4, 5‐dimethylthiazol‐2‐yl)‐2, 5‐diphenyltetrazolium bromide (G), and Ki67 staining with quantification of Ki67‐positive cells on the right (H) (n=5). Statistical values of cell counting and 3‐(4, 5‐dimethylthiazol‐2‐yl)‐2, 5‐diphenyltetrazolium bromide are shown in Data S2. I and J, Condition medium from Foxp1 knockdown human umbilical vein endothelial cells significantly increases human aortic smooth muscle cell migration shown by wound healing (I) and transwell assay (J) with representative images (left) and quantification (right) (n=6). Data are means±SEM. EC indicates endothelial cell; Foxp1, forkhead box P1; OD, optical density; and WT, wild‐type. *P<0.05, **P<0.01. Scale bars: A=50 μm, B, D, H, I, J=100 μm.

Specific deletion of Foxp1 in ECs caused significantly increased neointimal area from 0.03±0.004 μm2 in wild‐type (WT) mice (mean±SEM) to 0.07±0.005 μm2 in Foxp1 ECKO mice (P=0.001), intima‐to‐media ratio from 1.8±0.1 to 3.0±0.2 (P=0.001) and percentage of stenosis from 68.0±2.7% to 86.3±2.5% (P=0.001) without change of media area from 0.02±0.002 μm2 to 1.8±0.1 μm2 (P>0.05) at day 28 after wire injury of femoral artery, and no sex difference was observed in the process of neointimal formation (Figure 1B and 1C). Significantly increased proliferation was observed in the neointima of Foxp1 ECKO mice by Ki67 immunostaining (Foxp1 ECKO versus WT: 10.9±0.7% versus 6.4±0.7%; P=0.001) (Figure 1D). Because the injury‐induced neointima is mainly composed of VSMCs, 24 the result suggested that the increased neointimal formation in Foxp1 ECKO mice after injury was attributable to the increase of VSMC proliferation.

To further confirm the in vivo findings, we then knockdown Foxp1 in cultured human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) and investigated the effects of EC‐Foxp1 on VSMC proliferation and migration. Foxp1 expression was reduced by 99% in HUVECs treated with Foxp1 shRNA (Figure 1E). The effect of Foxp1 knockdown in HUVECs on cell proliferation of human aortic smooth muscle cells was determined by cell counting, 3‐(4, 5‐dimethylthiazol‐2‐yl)‐2, 5‐diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT) assay, and Ki67 staining assay (Figure 1F through Figure 1H). SMCs incubated with scramble EC medium increased cell number from 2.1±0.2×104 at 0 hours to 3.4±0.4×104 (P=0.0.06) at 24 hours and 6.9±0.4×104 (P=0.001) at 48 hours, with significant increase of cell number between 24 and 48 hours (P=0.001). SMCs treated with Foxp1 shRNA EC medium also increased cell number from 1.9×104 at 0 hours to 5.2×104 (P=0.002) at 24 hours and 12.7×104 (P=0.003) at 48 hours, with significant difference between 24 and 48 hours (P=0.005). We further found a significant increase in cell number between scramble EC medium and Foxp1 shRNA EC medium at 48 hours (P=0.049) (Figure 1F). Similarly, the relative MTT activity (MTT activity divided by that at 0 hours) of SMCs incubated with scramble EC medium was 2.4±0.1 (P=0.001) at 24 hours and 3.1±0.2 (P=0.001) at 48 hours, with significant increase of cell number between 24 and 48 hours (P=0.002). While the relative MTT activity of SMCs after Foxp1 shRNA EC medium treatment was 3.0±0.2 (P=0.001) at 24 hours and 4.5±0.2 (P=0.001) at 48 hours, with significant increase of cell number between 24 and 48 hours (P=0.001). MTT activity of SMCs incubated with Foxp1 shRNA EC medium was higher than that with scramble EC medium at 48 hours (P=0.004) (Figure 1G). Ki67 staining assay showed an increase in the percentage of Ki67+ SMCs treated with Foxp1 shRNA EC medium (26.9±4.6%) compared with SMCs treated with scramble EC medium (10.6±0.9%; P=0.009). In addition to increased VSMC proliferation, we found that the condition medium of Foxp1 knockdown HUVECs promoted human aortic smooth muscle cell migration shown by wound healing (Relative blank area: Foxp1 shRNA 20.2±2.6 versus scramble shRNA 46.2±2.5 at 24 hours after wounding; P=0.017) and transwell chemotactic assay (Foxp1 shRNA 198.7±18.0 versus scramble shRNA 100.1±8.3; P=0.001) (Figure 1I and 1J). These data suggest that EC‐Foxp1 deficiency increases VSMC proliferation and migration contributing to the increase of neointimal hyperplasia in vivo.

EC‐Foxp1 Regulates VSMC Proliferation and Migration and Neointimal Formation Via Regulating MMP9 Expression

To explore the downstream mechanisms by which EC‐Foxp1 affected injury‐induced neointimal hyperplasia, we performed RNA sequencing with ECs from Foxp1 deletion and littermate control WT mice was performed as previous described. 21 RT‐qPCR showed 2‐fold increase of matrix metalloproteinase (MMP)‐9 expression in endothelium after femoral artery injury (P=0.001) (Figure S1C), which was confirmed by Immunostaining (Figure S1D). Foxp1 deletion in EC further increased MMP9 expression shown by RNA sequencing (Table S1), which was confirmed by RT‐qPCR (2‐fold increase; P=0.001) (Figure 2A) and Western blot (Figure 2B). Moreover, we found an increased activity of EC‐MMP9 from 20.5±3.4 in WT mice to 58.2±6.2 in Foxp1 ECKO mutant mice (P=0.001) (Figure 2C).

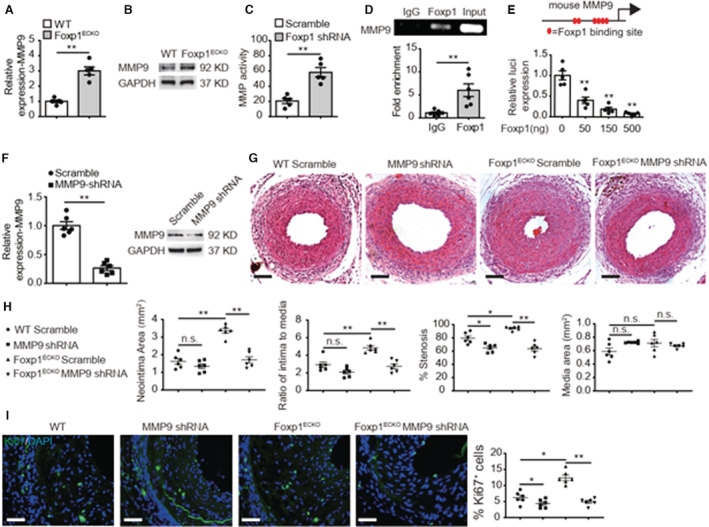

Figure 2. Foxp1 directly regulate matrix metalloproteinase‐9 (MMP9) gene expression in endothelial cells (ECs) and in vivo MMP9 inhibition reverses the enhanced neointimal formation.

A through C, Foxp1 ECKO mutant mice exhibit increased expression and activity of MMP9 shown by real‐time quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (A), Western blot (B), and MMP activity assay (C) in vascular ECs compared with wild‐type littermates (n=5). D, Chromatin immunoprecipitation assay shows that Foxp1 binds to the mouse MMP9 promoter by quantitative polymerase chain reaction and in agarose gel (n=6). E, The promoter region of MMP9, −4.0 kb to −3.5 kb before ATG translational site has 6 Foxp1 binding sites (left) and luciferase assay shows that Foxp1 expression vector dose‐dependent suppresses the luciferase reporter activity of this MMP9 promoter region (right) (n=5). F, Real‐time quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction and Western blot confirms the decreased expression of MMP9 in wire‐injured femoral artery after application of lentiviral MMP9‐shRNA compared with lentiviral scramble‐shRNA (n=6). G and H, MMP9 knockdown reverses the increased neointimal formation at 28 days after femoral artery wire injury caused by EC‐Foxp1 deletion, with representative images (G) and quantification of neointima area, intima‐to‐media ratio, percentage stenosis and media area (H) (n=6 for each group). I, MMP9 knockdown reverses EC‐Foxp1 deletion mediated increase of Ki67‐positive cells in neointima at 28 days after femoral artery wire injury, with representative images (left) and quantification data (right) (n=6 for each group). Data are means±SEM. EC indicates endothelial cell; Foxp1, forkhead box P1; IgG, immunoglobulin G; MMP9, matrix metalloproteinase‐9; OD, optical density; and WT, wild‐type. *P<0.05, **P<0.01. Scale bars: G, I=100 μm.

To validate the regulatory role of Foxp1 on MMP9 expression, we performed chromatin immunoprecipitation assays in mouse lung ECs and found that Foxp1 bound to the mouse MMP9 promoter (Figure 2D). There are 6 Foxp1 binding sites in the promoter region from −4.0 kb to −3.5 kb before the translational starting site of the MMP9 gene (Figure S2A) and luciferase reporter assay showed that Foxp1 overexpression repressed the luciferase activity in a dose‐dependent manner (Figure 2E and Figure S2B).

Previous studies reported that activation of MMP9 was involved in SMC proliferation and migration contributing to neointimal formation. 25 , 26 , 27 To clarify whether the EC‐Foxp1‐MMP9 pathway regulates VSMC proliferation and migration, we constructed a lentiviral MMP9 shRNA vector and applied this lenti‐MMP9 shRNA to Foxp1 ECKO mice and the littermate WT control mice attempting to rescue the EC‐Foxp1 deficiency‐mediated increased neointimal hyperplasia phenotypes. 73.4% MMP9 reduction was observed in femoral artery treated with lenti‐MMP9 shRNA by qPCR, which was confirmed by Western blotting (Figure 2F). MMP9 knockdown by lenti‐MMP9 shRNA inhibited wire injury induced neointimal hyperplasia shown by decreased neointima area (MMP9 shRNA 1.6±0.2 μm2 versus scramble shRNA 1.3±0.1 μm2; P>0.05), intima‐to‐media ratio (MMP9 shRNA 2.9±0.3 versus scramble shRNA 2.1±0.2; P>0.05) and percent of stenosis (MMP9 shRNA 79.6±3.4% versus scramble shRNA 64.8±2.5%; P=0.007). Immunostaining showed that MMP9 knockdown decreased the increased Ki67‐positive cells in the neointima of mice from 6.2±0.7% to 4.4±0.5% (P>0.05). Furthermore, MMP9 knockdown significantly reversed the increased neointimal hyperplasia in Foxp1 ECKO mutant mice as shown by reversal of the increased neointimal area (MMP9 shRNA 1.7±0.2 μm2 versus scramble shRNA 3.4±0.1 μm2; P=0.001), intima‐to‐media ratio (MMP9 shRNA 2.7±0.3 versus scramble shRNA 4.9±0.2 μm2; P=0.025) and percent of stenosis (MMP9 shRNA 63.5±3.5% versus scramble shRNA 94.7±1.2% μm2; P=0.001) in the femoral artery wire injury model compared with the scramble shRNA vector control (Figure 2G and 2H). MMP9 knockdown also reversed the increased Ki67‐positive cells in the neointima of Foxp1 ECKO mutant mice from 12.4±0.9% to 4.9±0.4% (P=0.001) (Figure 2I), suggesting that the EC‐Foxp1‐MMP9 signal might regulate VSMC proliferation and control in vivo neointimal formation.

We next used the constructed lentiviral MMP9 shRNA vector to investigate the role of MMP9 from ECs in VSMC proliferation and migration. RT‐qPCR analysis demonstrated >90% MMP9 expression decrease in lentiviral MMP9 shRNA infected HUVECs (P=0.001), which was confirmed by Western blot (Figure 3A). Consistent with in vivo results, MMP9 knockdown in HUVECs decreased SMC proliferation assessed by cell counting (9.1±0.6×104 to 5.6±0.5×104; P=0.008 at 48 hours), MTT assay (1.5±0.06 to 1.3±0.04 at 24 hours; P=0.015, 3.1±0.2 to 2.0±0.1 at 48 hours; P=0.015) and Ki67 staining assay (18.7±1.0% to 9.5±1.2%; P=0.001), and migration assessed by wound healing (54.3±2.6 to 74.3±3.0; P=0.001) and transwell chemotactic assay (100.0±5.6 to 57.2±7.0; P=0.017). Moreover, the condition medium from lentiviral MMP9 shRNA–infected HUVECs significantly reversed the EC‐Foxp1 knockdown induced increased SMC proliferation (Figure 3B through 3D) by cell counting (13.5±0.8×104 to 7.8±0.8×104 at 48 hours; P=0.005), MTT assay (5.0±0.4 to 2.8±0.2 at 48 hours; P=0.008) and Ki67 staining assay (25.4±1.9% to 10.3±1.0%; P=0.001). MMP9 knockdown in HUVECs also reversed the EC‐Foxp1 knockdown mediated increase in migration by wound healing (42.6±2.7 to 66.1±1.9; P=0.001) and transwell chemotactic assay (160.0±12.5 to 77.6±8.6; P=0.001) (Figure 3E and 3F). These data suggest that Foxp1 deletion in EC regulates MMP9 resulting in the attenuated VSMC proliferation and migration and in vivo neointimal formation.

Figure 3. Endothelial matrix metalloproteinase‐9 (MMP9) knockdown reverses Foxp1 knockdown‐mediated increased vascular smooth muscle cell proliferation and migration in a paracrine manner.

A, MMP9 expression is significantly decreased in human umbilical vein endothelial cells treated with lentiviral MMP9‐shRNA compared with lentiviral scramble‐shRNA by real‐time quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (left) and Western blot (right) (n=5). B through D, The condition medium of human umbilical vein endothelial cells treated with lentiviral MMP9‐shRNA reverses the Foxp1 knockdown‐mediated increase of vascular smooth muscle cell proliferation in comparison with that of human umbilical vein endothelial cells treated with lentiviral scramble‐shRNA, shown by cell counting (B), 3‐(4, 5‐dimethylthiazol‐2‐yl)‐2, 5‐diphenyltetrazolium bromide assay (C) and Ki67 staining with quantification on the right (D) (n=5). Statistical values of cell counting and MMT are shown in Data S2. E and F, Knockdown MMP9 in human umbilical vein endothelial cells reverses the Foxp1 knockdown mediated increase of vascular smooth muscle cell migration, shown by wound healing (E) and transwell assay (F), with representative images (left) and quantification data (right) (n=5). Data are means±SEM. Foxp1 indicates forkhead box P1; HASMCs, human aortic smooth muscle cells; MMP9, matrix metalloproteinase‐9; and NC, negative control. *P<0.05, **P<0.01. Scale bars: D, E, F=100 μm.

Endothelial Foxp1 Deletion Impairs Endothelial Repair and Enhances Wire Injury Induced Neointimal Formation

The impaired endothelium results in neointimal thickening following PCI treatment and the improvement of endothelial repair was correlated with the diminished intimal hyperplasia induced by endothelial denudation. 28 , 29 Therefore, we studied the effects of EC‐Foxp1 on reendothelialization contributing to the injury‐induced neointimal hyperplasia. We found an impaired endothelial repair in Foxp1 ECKO mutant mice (50.6±3.7%) at day 7 after femoral artery injury compared with WT mice (63.2±3.0%; P=0.024) assessed by Evans blue staining (Figure 4A). Consistent with the in vivo findings, a significant decrease of cell proliferation shown by cell counting (from 10.1±0.6×104 to 5.5±0.5×104 at 48 hours; P=0.029), MTT assay (from 2.4±0.1 to 1.8±0.1 at 48 hours; P=0.040), and Ki67 staining (from 16.3±1.3 to 10.8±1.1; P=0.012) (Figure 4B through Figure 4D) and attenuation of cell migration shown by wound healing (from 38.1±2.8 to 50.6±2.2; P=0.049) and transwell chemotactic assay (from 100±2.4% to 77.5±2.3%; P=0.001) (Figure S3A and S3B) were observed in Foxp1 knockdown HUVECs. These data highlight that EC‐Foxp1 deletion impairs EC repair after wire injury by decrease of EC proliferation and migration, therefore aggravates the injury‐induced neointimal formation.

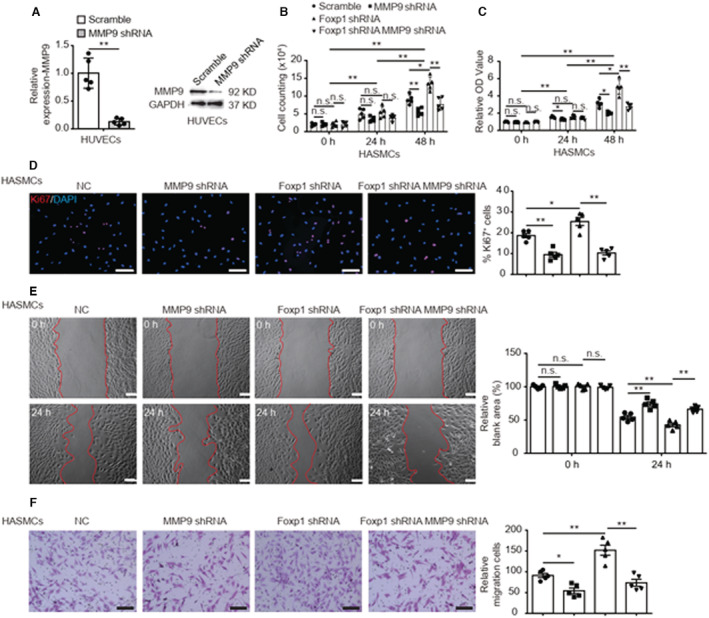

Figure 4. Endothelial cell (EC)‐Foxp1 (forkhead box P1) regulates cyclin dependent kinase inhibitor 1B (Cdkn1b) expression contributing to endothelial repair after injury denudation and neointimal formation.

A, EC‐Foxp1 deletion mice exhibit significant less EC coverage of whole mount femoral artery by in situ Evans blue staining at 7 days after wire injury compared with wild‐type littermate control mice, with representative images (left) and quantification (right) (n=6 for each group). B through D, Human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) treated with lentiviral Foxp1‐shRNA display decreased cell proliferation in comparison with HUVECs treated with lentiviral scramble‐shRNA, shown by cell counting (B), 3‐(4, 5‐dimethylthiazol‐2‐yl)‐2, 5‐diphenyltetrazolium bromide assay (C) and Ki67 staining with quantification on the right (D) (n=5). Statistical values of cell counting and MMT are shown in Data S2. E and F, HUVECs treated with lentiviral Foxp1‐shRNA display increased expression of Cdkn1b shown by real‐time quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (E) and Western blot (F) compared with HUVECs treated with lentiviral scramble‐shRNA (n=5). G, Chromatin immunoprecipitation assay shows that Foxp1 binds to the mouse Cdkn1b promoter by quantitative polymerase chain reaction (down) with agarose gel (up) (n=5). H, The promoter region of Cdkn1b, −1.4kb before Exon 1 has 3 Foxp1‐binding sites (left) and luciferase assay shows that Foxp1 expression vector dose‐dependent suppresses the luciferase reporter activity of this Cdkn1b promoter region (right) (n=5). I, The efficiency of decreased Cdkn1b expression following RGD (Arg‐Gly‐Asp)‐peptide magnetic nanoparticle application was confirmed by real‐time quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction in lung ECs (n=8). J, RGD (Arg‐Gly‐Asp)‐nanoparticles target delivery of Cdkn1b‐siRNA to endothelial cells (ECs) reverses the Foxp1 deletion‐mediated decreased EC repair following wire injury, shown by in situ Evans blue staining of femoral artery (n=8). K, Decreased expression of Cdkn1b in HUVECs treated with Cdkn1b‐siRNA is confirmed by real‐time quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction and Western blot (n=5). L through N, Cdkn1b‐siRNA knockdown HUVECs reverses the Foxp1 knockdown‐mediated decrease of cell proliferation in comparison with HUVECs treated with scramble‐siRNA, shown by cell counting (L), 3‐(4, 5‐dimethylthiazol‐2‐yl)‐2, 5‐diphenyltetrazolium bromide assay (M) and Ki67 staining with quantification on the right (N) (n=5). Statistical values of cell counting and MMT are shown in Data S2. Data are means±SEM. Cdkn1b indicates cyclin dependent kinase inhibitor 1B; Foxp1, forkhead box P1; HUVECs, human umbilical vein endothelial cells; IgG, immunoglobulin G; MMP9, matrix metalloproteinase‐9; NC, negative control; OD, optical density; and WT, wild‐type. *P<0.05, **P<0.01. Scale bars: A, J=1 mm; D, N=100 μm.

EC‐Foxp1 Regulates Endothelial Repair After Injury Denudation and Control Neointimal Formation Via Targeting Cdkn1b Gene Expression

FOX proteins play vital roles in cell cycle progression, proliferation, and differentiation. 30 We found a 1.7‐fold increased expression of Cdkn1b in HUVECs upon Foxp1 knockdown by RT‐qPCR (P=0.001) (Figure 4E), which was confirmed by Western blot (Figure 4F). We analyzed the promoter of the Cdkn1b gene and found multiple Foxp1 binding sites (Figure S4A and S4B). Further chromatin immunoprecipitation assays confirmed that Foxp1 directly bound to the Cdkn1b promoter (Figure 4G). We next cloned the promoter region from −1.4 kb to −0.2 kb before exon 1 of the Cdkn1b gene into pGL3 promoter luciferase reporter vector and luciferase reporter assay showed that Foxp1 expression dose‐dependent repressed the luciferase activity (Figure 4H).

To clarify whether the EC‐Foxp1‐Cdkn1b pathway regulates EC proliferation and contributes to neointimal formation, we constructed RGD (Arg‐Gly‐Asp)‐peptide magnetic nanoparticles to target deliver Cdkn1b–siRNA and rescue the EC‐Foxp1 deletion‐mediated impaired EC repair in Foxp1 ECKO mice. 65% decreased Cdkn1b expression following RGD (Arg‐Gly‐Asp)‐peptide magnetic nanoparticle application was assessed by RT‐qPCR in lung ECs (P=0.009) (Figure 4I). We found that in vivo EC‐Cdkn1b knockdown significantly improved the repair of the EC denuded femoral artery from 64.6±3.2% to 78.9±4.3% by Evans blue staining (P=0.024). Furthermore, EC‐Cdkn1b knockdown reversed the impaired EC repair of the EC denuded femoral artery in Foxp1 ECKO mutant mice from 51.4±3.1% to 70.3±2.5% (P=0.002) (Figure 4J), suggesting that the EC‐Foxp1‐Cdkn1b signal might regulate EC repair contributing to in vivo neointimal formation.

To further confirm these in vivo findings, we used siRNA to knockdown Cdkn1b and investigate the effects of Cdkn1b on EC‐Foxp1 deletion‐mediated decreased proliferation in in vitro cultured HUVECs. The efficiency of decreased Cdkn1b expression in HUVECs was confirmed by RT‐qPCR (88% reduction; P=0.001) and Western blot (Figure 4K). Cdkn1b‐siRNA in HUVECs increased cell proliferation assessed by cell counting (5.6±0.4×104 to 8.3±0.5×104 at 24 hours; P=0.010, 8.6±0.6×104 to 12.5±0.7×104 at 48 hours; P=0.016), MTT assay (1.6±0.07 to 2.2±0.1 at 24 hours; P=0.030, 2.4±0.1 to 3.5±0.2, P=0.007 at 48 hours), and Ki67 staining assay (22.7±1.9% to 30.2±2.2%; P=0.016). We further found that Cdkn1b‐siRNA normalized the EC‐Foxp1 knockdown‐mediated decreased cell proliferation compared with scramble siRNA by cell counting (4.0±0.3×104 to 6.6±0.3×104 at 24 hours; P=0.002, 5.9±0.5×104 to 9.4±0.5×104 at 48 hours; P=0.005), MTT assay (1.1±0.05 to 1.9±0.1 at 24 hours; P=0.003, 1.7±0.1 to 2.6±0.2 at 48 hours; P=0.018), and Ki67 staining assay (13.5±1.1% to 24.4±1.9%; P=0.005); (Figure 4L and 4N), thus providing evidence that the EC‐Foxp1‐Cdkn1b pathway might regulate injury denuded EC repair through cell proliferation and control in vivo neointimal formation.

EC‐Foxp1 Gain‐of‐Function Attenuates Wire Injury Induced Neointimal Formation Through Decreased VSMC Proliferation and Migration and Improved Endothelial Repair

Contrary to EC‐Foxp1 loss‐of‐function mice, EC‐Foxp1 gain‐of‐function (Foxp1 ECTg ) mice which had elevated Foxp1 expression in ECs (2.3‐fold increase by RT‐qPCR; P=0.001) (Figure 5A), displayed decreased neointimal area from 0.04±0.002 μm2 to 0.02±0.002 μm2 (P=0.001), intima‐to‐media ratio from 1.9±0.3 to 1.1±0.1 (P=0.012) and percentage of stenosis from 66.7±3.6% to 48.6±3.9% (P=0.005), with no change in media area from 0.02±0.001 μm2 to 0.02±0.003 μm2 (P>0.05) (Figure 5B and 5C). VSMC proliferation in the neointima of Foxp1 ECTg mice was decreased from 7.7±1.0% to 3.9±0.9% assessed by Ki67 antibody immunostaining compared with the littermate WT control mice (P=0.017) (Figure 5D), and EC repair in Foxp1 ECTg mice was improved evaluated by Evans blue staining at day 7 after femoral artery injury (WT 56.5±3.7% versus Foxp1ECTg 70.5±4.1%; P=0.030) (Figure 5E). We found reduced MMP9 (71.8% reduction; P=0.004) and Cdkn1b (53.5% reduction; P=0.016) expression in ECs of Foxp1 ECTg mice compared with littermateWT control mice (Figure S5A). Recombinant MMP9 protein (rMMP9) significantly reversed the reduction of neointimal hyperplasia in Foxp1 ECTg mice assessed by intima‐to‐media ratio (PBS 1.2±0.2 versus rMMP9 2.3±0.2; P=0.003), percent of stenosis (PBS 57.8±2.0% versus rMMP9 80.3±2.4%; P=0.001), and reduced Ki67‐positive cells immunostaining (PBS 3.1±0.6% versus rMMP9 11.6±1.7%; P=0.001) in the wire injury femoral artery (Figure S5B and S5C).

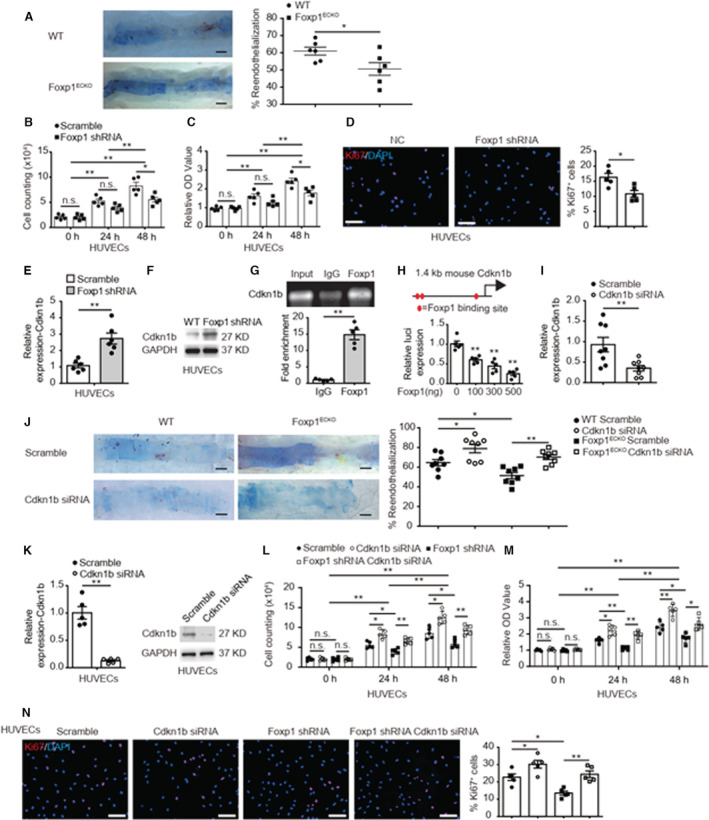

Figure 5. Endothelial cell (EC)‐Foxp1 (forkhead box P1) gain‐of‐function attenuates vascular neointimal formation through facilitation of EC repair and reduction of vascular smooth muscle cell proliferation and migration after wire injury.

A, EC‐Foxp1 gain‐of‐function mice (Foxp1 ECTg ) exhibit a significant increase of Foxp1 expression in vascular ECs compared with wild‐type mice by real‐time quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (left) and Western blot (right) (n=7). B and C, Foxp1 ECTg mutant mice exhibit decreased neointimal formation at 28 days after femoral artery wire injury compared with wild‐type littermates, with representative images (B) and quantification of neointima area, intima to media ratio, percentage stenosis and media area (C) (n=7 for each group). D, Foxp1 ECTg mutant mice exhibit significantly decreased cell proliferation in neointima at 28 d after femoral artery wire injury, with representative images (left) and quantification data (right) (n=7 for each group). E, Foxp1 ECTg mutant mice exhibit a significant increase of EC coverage of femoral artery by in situ Evans blue staining at 7 days following wire injury compared with wild‐type littermates, with representative images (left) and quantification (right) (n=6 for each group). F, Real‐time quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction and Western blot confirm the significant increase of Foxp1 expression in human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) treated with Foxp1 overexpression vector compared with empty control vector (n=5). G through I, Condition medium from Foxp1 overexpression HUVECs significantly inhibits human aortic smooth muscle cell proliferation compared with that from HUVECs of control vector, shown by cell counting (G), 3‐(4, 5‐dimethylthiazol‐2‐yl)‐2, 5‐diphenyltetrazolium bromide assay (H), and Ki67 staining with quantification of Ki67‐positive cells on the right (I) (n=5). Statistical values of cell counting and MMT are shown in Data S2. J and K, Condition medium from Foxp1 overexpression HUVECs significantly inhibits human aortic smooth muscle cell migration compared with that from HUVECs of control vector, shown by transwell (J) and wound healing assay (K), with representative images (left) and quantification (right) (n=5). L through N, Foxp1 overexpression in HUVECs increases cell proliferation in comparison with that of control vector, shown by cell counting (L), 3‐(4, 5‐dimethylthiazol‐2‐yl)‐2, 5‐diphenyltetrazolium bromide assay (M) and Ki67 staining with quantification on the right (N) (n=5). Statistical values of cell counting and MMT are shown in Data S2. Data are means±SEM. Foxp1 indicates forkhead box P1; HASMCs, human aortic muscle cells; HUVECs, human umbilical vein endothelial cells; MMP9, matrix metalloproteinase‐9; OD, optical density; and WT, wild‐type. *P<0.05, **P<0.01. Scale bars: B, D, I, J, K, N=100 μm; E=1 mm.

We then overexpressed Foxp1 in HUVECs and investigated the effects of EC‐Foxp1 gain‐of‐function on VSMC proliferation and migration. Foxp1 overexpression was confirmed by RT‐qPCR (1.4‐fold increase; P=0.002) and Western blot (Figure 5F), and Foxp1 overexpression in HUVEC significantly decreased the cell proliferation of human aortic smooth muscle cells as shown by cell counting (empty 3.7±0.2×104 versus Foxp1 overexpression 2.7±0.2×104 at 24 hours; P=0.046, empty 6.8±0.4×104 versus Foxp1 OE 5.1±0.3×104 at 48 hours; P=0.043), MTT assay (empty 3.8±0.2 versus Foxp1 overexpression 2.5±0.2; P=0.002), and Ki67 staining (empty 27.8±2.6% versus 20.2±1.6%; P=0.038) (Figure 5G through Figure 5I). The condition medium of Foxp1 overexpressed HUVECs also significantly reduced the migration of human aortic smooth muscle cells shown by transwell chemotactic (empty 100.0±7.1 versus Foxp1 overexpression 66.3±4.6; P=0.003) and wound healing assay (empty 39.9±2.9 versus Foxp1 overexpression 58.5±4.2; P=0.006) (Figure 5J and 5K). Moreover, The HUVECs of Foxp1 overexpression exhibited increase of cell proliferation shown by cell counting (empty 7.0±0.6×104 versus Foxp1 overexpression 10.1±0.7×104; P=0.029), MTT assay (empty 4.6±0.2 versus Foxp1 overexpression 6.2±0.4; P=0.042), and Ki67 staining (empty 17.0±1.4% versus Foxp1 overexpression 23.1±1.8; P=0.026) (Figure 5L and Figure 5N) and increase of cell migration shown by wound healing (empty 56.9±2.6 versus Foxp1 overexpression 29.7±2.4; P=0.001) and transwell chemotactic assay (empty 100.0±5.7 versus Foxp1 overexpression 204.7±10.6; P=0.001) (Figure S6). EC‐Cdkn1b overexpression reversed the EC‐Foxp1 gain‐of‐function‐mediated increase of EC proliferation compared with the control empty vector by cell counting (empty 3.6±0.2 versus Cdkn1b overexpression 3.0±0.1 at 24 hours; P=0.039, empty 8.4±0.3 versus Cdkn1b overexpression 6.7±0.3 at 48 hours; P=0.007) and MTT (empty 1.6±0.07 versus Cdkn1b overexpression 1.3±0.05 at 24 hours; P=0.018, empty 3.6±0.15 versus Cdkn1b overexpression 2.2±0.07 at 48 hours; P=0.007) (Figure S5D through S5F). These data indicate that EC‐Foxp1 overexpression restricts VSMC proliferation and migration and improves EC repair leadings to the attenuation of neointimal hyperplasia in vivo via EC‐Foxp1‐MMP9/Cdkn1b signaling pathway.

Overall, our data reveal that EC‐Foxp1 reduces MMP9 expression to restrict VSMCs proliferation and migration, as well as suppresses Cdkn1b expression to promote EC proliferation for improvement of EC repair, and that both work together resulted in the attenuation of the injury induced neoinitmal hyperplasia (Figure 6).

Figure 6. Working model of how endothelial cell‐Foxp1 (forkhead box P1) regulates neointimal hyperplasia through matrix metalloproteinase‐9/cyclin dependent kinase inhibitor 1B signal pathway following femoral artery injury.

Endothelial cell‐Foxp1 paracrine reduces matrix metalloproteinase‐9 expression to restrict vascular smooth muscle cells proliferation and migration and suppresses cyclin dependent kinase inhibitor 1B expression to promote endothelial cell proliferation for improvement of endothelial cell repair, and both work together leading to the attenuation of the injury induced neointimal hyperplasia. Cdkn1b indicates cyclin dependent kinase inhibitor 1B; EC, endothelial cells; Foxp1, forkhead box P1; MMP9, matrix metalloproteinase‐9; and WT, wild‐type.

DISCUSSION

Vascular stent placement has become a common procedure in cardiovascular disease, which can dredge occluded vessels and restore blood flow. However, stent deployment causes injury of vascular endothelium followed by excess VSMC proliferation and migration contributing to neointimal hyperplasia and hence restenosis, which is still a clinical problem, although stent technology advances have incrementally improved the outcomes. Foxp1 was reported to be important in EC proliferation and migration, 18 and our previous study demonstrated an important role of EC‐Foxp1 in the regulation of cardiomyocyte proliferation, 16 cardiac fibroblast proliferation, and myofibroblast transformation. 17 The present study demonstrated that EC‐Foxp1 regulates the MMP9/Cdkn1b signaling pathway to control VSMC proliferation/migration and reendothelialization, thus, we uncovered a novel role of EC‐Foxp1 in neointimal hyperplasia responsible for restenosis.

During the process of neointimal hyperplasia, VSMCs can transform from the static contractile state to the proliferative synthetic state in the response to pathological stimuli. Loss of endothelium or activated dysfunctional ECs induced excessive proliferation and migration of synthetic SMCs until endothelium is functionally recovered. 4 , 5 , 6 , 7 , 8

MMP9, one member of the MMP family, participates in the degradation of the ECM in the physiological and pathophysiological processes involving tissue remodeling associated with cardiovascular diseases. 31 , 32 , 33 , 34 MMP9 is secreted by neutrophils, macrophages, and fibroblasts. 31 , 32 MMP9 is also detected in vascular ECs and VSMC and it is important for early‐stage arterial remodeling and causes a rise in pressure through altered vessel distensibility responsible for hypertension. 33 The 3 key target regulation genes of myocardin‐related transcription factor‐A/serum response factor, including vinculin, MMP‐ 9, and integrin β1, were reported to regulate VSMC migration and are crucial for pathological vascular remodeling in mice. 34 Also, MMP9 was activated after arterial injury 35 and during preparation of vein grafts 36 and it is essential for the migration of smooth muscle cells into the intima contributing to injury induced neointimal formation. 37 MMP9 was involved in proangiogenic EC function and endothelial cell mediated medial disruption during the progression of abdominal aortic aneurysm. 38 However, it was still unknown about the transcriptional regulation of MMP9 expression in ECs and the roles of EC‐MMP9 in neointimal formation. Our data indicate that EC‐Foxp1 directly regulates MMP9 expression and increase of MMP9 and neointimal formation caused by loss‐of Foxp1 in ECs could be rescued by local delivery of lentiviral MMP9 shRNA to the injured artery, therefore providing in vivo evidence that EC‐Foxp1‐MMP9 pathway may be therapeutic targets for injury‐induced neointimal formation.

A healthy EC layer is the most important factor in maintaining vascular homeostasis. PCI stent deployment causes vascular injury and damaged ECs are repaired by locally derived ECs. 12 Delayed and impaired endothelial recovery are involved in late stent restenosis and thrombosis. 13 , 39 The biological factors and the cellular and molecular mechanisms that govern the reendothelialization process are not clear. Loss of endothelial protein tyrosine phosphatase‐1B, a negative regulator of receptor tyrosine kinase signaling for cell proliferation and senescence, impaired reendothelialization and the failure to induce smooth muscle cell quiescence and resulted in neointimal hyperplasia. 40 A recent study found that activation of the transcription factor FOXO1 (forkhead box O1) in ECs limited cell cycle progression, metabolic activity, and vascular expansion. 41 Foxp1 was essential in the regulation of EC proliferation and migration. 18 A previous study demonstrated that EC‐MMP9 promoted angiogenesis through activating PAR1 in apoE−/− mice, 42 however, we did not find significant change of EC proliferation and migration in the baseline unstimulated condition (data not shown). Possibly MMPs might exert different effects on baseline or prorestenotic condition in comparison with the proinflammatory condition in apoE−/− mice. Moreover, we found MMP9 knockdown did not change the decreased EC proliferation upon EC‐Foxp1 deletion (data not shown). Therefore, we further explored the mechanisms, and we found regulation of EC‐Foxp1 for Cdkn1b to control endothelial repair and hence neointimal formation. Delivery of Cdkn1b‐siRNA using RGD (Arg‐Gly‐Asp)‐peptide magnetic nanoparticle to ECs reversed the EC‐Foxp1 deletion‐mediated impaired EC repair and attenuated the neointimal formation, thus providing in vivo evidence of EC‐Foxp1 regulation of Cdkn1b controlling reendothelialization of endothelial injury and further influencing neointimal hyperplasia.

Taken together, these data using both EC‐Foxp1 loss‐ and gain‐of‐function mice demonstrate that EC‐Foxp1 regulates injury induced neointimal formation by paracrine modulation of MMP9 for VSMC proliferation and migration and cell autonomous modulation of Cdkn1b of reendothelialization controlling neointimal formation. The EC target delivery of MMP9/Cdkn1b might provide future novel therapeutic interventions for restenosis.

Sources of Funding

This study was supported by the funds from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 82070456, 81800253, 81970233, 81770259, 81970234, 81970232, 81903174, 81770094, 81870202, 81570237, 81870197), Shanghai Rising‐Star Program (Grant no. 21QA1401400, 20QA1408100), Shanghai Science and Technology innovation Action Plan (Grant no. 19JC1414500), Health System Academic Leader Training Plan of Pudong District Shanghai (Grant no. PWRd2018‐06), Peak Disciplines (Type IV) of Institutions of Higher Learning in Shanghai.

Disclosures

None.

Supporting information

Supplemental Material is available at https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/suppl/10.1161/JAHA.122.026378

For Sources of Funding and Disclosures, see page 13.

Contributor Information

Li Lin, Email: linli777@126.com.

Jie Liu, Email: kenliujie@126.com.

Tao Zhuang, Email: zhuangtao5217@163.com.

REFERENCES

- 1. Serruys PW, Ono M, Garg S, Hara H, Kawashima H, Pompilio G, Andreini D, Holmes DR Jr, Onuma Y, King Iii SB. Percutaneous coronary revascularization: JACC historical breakthroughs in perspective. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2021;78:384–407. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2021.05.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Chacko L, Howard JP, Rajkumar C, Nowbar AN, Kane C, Mahdi D, Foley M, Shun‐Shin M, Cole G, Sen S, et al. Effects of percutaneous coronary intervention on death and myocardial infarction stratified by stable and unstable coronary artery disease: a meta‐analysis of randomized controlled trials. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2020;13:e006363. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.119.006363 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Yang X, Yang Y, Guo J, Meng Y, Li M, Yang P, Liu X, Aung LHH, Yu T, Li Y. Targeting the epigenome in in‐stent restenosis: from mechanisms to therapy. Mol Ther Nucleic Acids. 2021;23:1136–1160. doi: 10.1016/j.omtn.2021.01.024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Otsuka F, Finn AV, Yazdani SK, Nakano M, Kolodgie FD, Virmani R. The importance of the endothelium in atherothrombosis and coronary stenting. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2012;9:439–453. doi: 10.1038/nrcardio.2012.64 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Marx SO, Totary‐Jain H, Marks AR. Vascular smooth muscle cell proliferation in restenosis. Circ Cardiovasc Interv. 2011;4:104–111. doi: 10.1161/CIRCINTERVENTIONS.110.957332 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Owens GK, Kumar MS, Wamhoff BR. Molecular regulation of vascular smooth muscle cell differentiation in development and disease. Physiol Rev. 2004;84:767–801. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00041.2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Cornelissen A, Vogt FJ. The effects of stenting on coronary endothelium from a molecular biological view: time for improvement? J Cell Mol Med. 2019;23:39–46. doi: 10.1111/jcmm.13936 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. van Beusekom HM, Whelan DM, Hofma SH, Krabbendam SC, van Hinsbergh VW, Verdouw PD, van der Giessen WJ. Long‐term endothelial dysfunction is more pronounced after stenting than after balloon angioplasty in porcine coronary arteries. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1998;32:1109–1117. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(98)00348-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Wang J, Jin X, Huang Y, Ran X, Luo D, Yang D, Jia D, Zhang K, Tong J, Deng X, et al. Endovascular stent‐induced alterations in host artery mechanical environments and their roles in stent restenosis and late thrombosis. Regen Biomater. 2018;5:177–187. doi: 10.1093/rb/rby006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Zhuang T, Liu J, Chen X, Pi J, Kuang Y, Wang Y, Tomlinson B, Chan P, Zhang Q, Li Y, et al. Cell‐specific effects of GATA (GATA zinc finger transcription factor family)‐6 in vascular smooth muscle and endothelial cells on vascular injury neointimal formation. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2019;39:888–901. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.118.312263 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Wang X, Fang F, Ni Y, Yu H, Ma J, Deng L, Li C, Shen Y, Liu X. The combined contribution of vascular endothelial cell migration and adhesion to stent re‐endothelialization. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2021;9:641382. doi: 10.3389/fcell.2021.641382 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Van der Heiden K, Gijsen FJ, Narracott A, Hsiao S, Halliday I, Gunn J, Wentzel JJ, Evans PC. The effects of stenting on shear stress: relevance to endothelial injury and repair. Cardiovasc Res. 2013;99:269–275. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvt090 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Hutter R, Carrick FE, Valdiviezo C, Wolinsky C, Rudge JS, Wiegand SJ, Fuster V, Badimon JJ, Sauter BV. Vascular endothelial growth factor regulates reendothelialization and neointima formation in a mouse model of arterial injury. Circulation. 2004;110:2430–2435. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000145120.37891.8A [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Li S, Weidenfeld J, Morrisey EE. Transcriptional and DNA binding activity of the Foxp1/2/4 family is modulated by heterotypic and homotypic protein interactions. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24:809–822. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.2.809-822.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Shu W, Yang H, Zhang L, Lu MM, Morrisey EE. Characterization of a new subfamily of winged‐helix/forkhead (fox) genes that are expressed in the lung and act as transcriptional repressors. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:27488–27497. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M100636200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Zhang Y, Li S, Yuan L, Tian Y, Weidenfeld J, Yang J, Liu F, Chokas AL, Morrisey EE. Foxp1 coordinates cardiomyocyte proliferation through both cell‐autonomous and nonautonomous mechanisms. Genes Dev. 2010;24:1746–1757. doi: 10.1101/gad.1929210 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Liu J, Zhuang T, Pi J, Chen X, Zhang Q, Li Y, Wang H, Shen Y, Tomlinson B, Chan P, et al. Endothelial Forkhead box transcription factor P1 regulates pathological cardiac remodeling through transforming growth factor‐beta1‐Endothelin‐1 signal pathway. Circulation. 2019;140:665–680. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.119.039767 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Grundmann S, Lindmayer C, Hans FP, Hoefer I, Helbing T, Pasterkamp G, Bode C, de Kleijn D, Moser M. FoxP1 stimulates angiogenesis by repressing the inhibitory guidance protein semaphorin 5B in endothelial cells. PLoS One. 2013;8:e70873. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0070873 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Wang H, Geng J, Wen X, Bi E, Kossenkov AV, Wolf AI, Tas J, Choi YS, Takata H, Day TJ, et al. The transcription factor Foxp1 is a critical negative regulator of the differentiation of follicular helper T cells. Nat Immunol. 2014;15:667–675. doi: 10.1038/ni.2890 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Wang Y, Nakayama M, Pitulescu ME, Schmidt TS, Bochenek ML, Sakakibara A, Adams S, Davy A, Deutsch U, Luthi U, et al. Ephrin‐B2 controls VEGF‐induced angiogenesis and lymphangiogenesis. Nature. 2010;465:483–486. doi: 10.1038/nature09002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Zhuang T, Liu J, Chen X, Zhang L, Pi J, Sun H, Li L, Bauer R, Wang H, Yu Z, et al. Endothelial Foxp1 suppresses atherosclerosis via modulation of Nlrp3 inflammasome activation. Circ Res. 2019;125:590–605. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.118.314402 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Li H, Wang Y, Liu J, Chen X, Duan Y, Wang X, Shen Y, Kuang Y, Zhuang T, Tomlinson B, et al. Endothelial Klf2‐Foxp1‐TGFbeta signal mediates the inhibitory effects of simvastatin on maladaptive cardiac remodeling. Theranostics. 2021;11:1609–1625. doi: 10.7150/thno.48153 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Bot PT, Grundmann S, Goumans MJ, de Kleijn D, Moll F, de Boer O, van der Wal AC, van Soest A, de Vries JP, van Royen N, et al. Forkhead box protein P1 as a downstream target of transforming growth factor‐beta induces collagen synthesis and correlates with a more stable plaque phenotype. Atherosclerosis. 2011;218:33–43. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2011.05.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Chappell J, Harman JL, Narasimhan VM, Yu H, Foote K, Simons BD, Bennett MR, Jorgensen HF. Extensive proliferation of a subset of differentiated, yet plastic, medial vascular smooth muscle cells contributes to neointimal formation in mouse injury and atherosclerosis models. Circ Res. 2016;119:1313–1323. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.116.309799 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Mason DP, Kenagy RD, Hasenstab D, Bowen‐Pope DF, Seifert RA, Coats S, Hawkins SM, Clowes AW. Matrix metalloproteinase‐9 overexpression enhances vascular smooth muscle cell migration and alters remodeling in the injured rat carotid artery. Circ Res. 1999;85:1179–1185. doi: 10.1161/01.res.85.12.1179 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Johnson JL, Dwivedi A, Somerville M, George SJ, Newby AC. Matrix metalloproteinase (MMP)‐3 activates MMP‐9 mediated vascular smooth muscle cell migration and neointima formation in mice. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2011;31:e35–e44. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.111.225623 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Gliesche DG, Hussner J, Witzigmann D, Porta F, Glatter T, Schmidt A, Huwyler J. Meyer Zu Schwabedissen HE. Secreted matrix Metalloproteinase‐9 of proliferating smooth muscle cells as a trigger for drug release from stent surface polymers in coronary arteries. Mol Pharm. 2016;13:2290–2300. doi: 10.1021/acs.molpharmaceut.6b00033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Tesfamariam B. Endothelial repair and regeneration following intimal injury. J Cardiovasc Transl Res. 2016;9:91–101. doi: 10.1007/s12265-016-9677-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Jian D, Wang W, Zhou X, Jia Z, Wang J, Yang M, Zhao W, Jiang Z, Hu X, Zhu J. Interferon‐induced protein 35 inhibits endothelial cell proliferation, migration and re‐endothelialization of injured arteries by inhibiting the nuclear factor‐kappa B pathway. Acta Physiol. 2018;223:e13037. doi: 10.1111/apha.13037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Lam EW, Brosens JJ, Gomes AR, Koo CY. Forkhead box proteins: tuning forks for transcriptional harmony. Nat Rev Cancer. 2013;13:482–495. doi: 10.1038/nrc3539 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Yabluchanskiy A, Ma Y, Iyer RP, Hall ME, Lindsey ML. Matrix metalloproteinase‐9: many shades of function in cardiovascular disease. Physiology. 2013;28:391–403. doi: 10.1152/physiol.00029.2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Siefert SA, Sarkar R. Matrix metalloproteinases in vascular physiology and disease. Vascular. 2012;20:210–216. doi: 10.1258/vasc.2011.201202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Lehoux S, Lemarie CA, Esposito B, Lijnen HR, Tedgui A. Pressure‐induced matrix metalloproteinase‐9 contributes to early hypertensive remodeling. Circulation. 2004;109:1041–1047. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000115521.95662.7A [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Minami T, Kuwahara K, Nakagawa Y, Takaoka M, Kinoshita H, Nakao K, Kuwabara Y, Yamada Y, Yamada C, Shibata J, et al. Reciprocal expression of MRTF‐A and myocardin is crucial for pathological vascular remodelling in mice. EMBO J. 2012;31:4428–4440. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2012.296 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Zempo N, Kenagy RD, Au YP, Bendeck M, Clowes MM, Reidy MA, Clowes AW. Matrix metalloproteinases of vascular wall cells are increased in balloon‐injured rat carotid artery. J Vasc Surg. 1994;20:209–217. doi: 10.1016/0741-5214(94)90008-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. George SJ, Zaltsman AB, Newby AC. Surgical preparative injury and neointima formation increase MMP‐9 expression and MMP‐2 activation in human saphenous vein. Cardiovasc Res. 1997;33:447–459. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(96)00211-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Cho A, Reidy MA. Matrix metalloproteinase‐9 is necessary for the regulation of smooth muscle cell replication and migration after arterial injury. Circ Res. 2002;91:845–851. doi: 10.1161/01.res.0000040420.17366.2e [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Ramella M, Boccafoschi F, Bellofatto K, Follenzi A, Fusaro L, Boldorini R, Casella F, Porta C, Settembrini P, Cannas M. Endothelial MMP‐9 drives the inflammatory response in abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA). Am J Transl Res. 2017;9:5485–5495. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Finn AV, Joner M, Nakazawa G, Kolodgie F, Newell J, John MC, Gold HK, Virmani R. Pathological correlates of late drug‐eluting stent thrombosis: strut coverage as a marker of endothelialization. Circulation. 2007;115:2435–2441. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.693739 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Jager M, Hubert A, Gogiraju R, Bochenek ML, Munzel T, Schafer K. Inducible knockdown of endothelial protein tyrosine phosphatase‐1B promotes neointima formation in obese mice by enhancing endothelial senescence. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2019;30:927–944. doi: 10.1089/ars.2017.7169 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Andrade J, Shi C, Costa ASH, Choi J, Kim J, Doddaballapur A, Sugino T, Ong YT, Castro M, Zimmermann B, et al. Control of endothelial quiescence by FOXO‐regulated metabolites. Nat Cell Biol. 2021;23:413–423. doi: 10.1038/s41556-021-00637-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Florence JM, Krupa A, Booshehri LM, Allen TC, Kurdowska AK. Metalloproteinase‐9 contributes to endothelial dysfunction in atherosclerosis via protease activated receptor‐1. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0171427. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0171427 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Wang M, Ihida‐Stansbury K, Kothapalli D, Tamby MC, Yu Z, Chen L, Grant G, Cheng Y, Lawson JA, Assoian RK, et al. Microsomal prostaglandin e2 synthase‐1 modulates the response to vascular injury. Circulation. 2011;123:631–639. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.973685 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Konishi H, Sydow K, Cooke JP. Dimethylarginine dimethylaminohydrolase promotes endothelial repair after vascular injury. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;49:1099–1105. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2006.10.068 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Pi J, Tao T, Zhuang T, Sun H, Chen X, Liu J, Cheng Y, Yu Z, Zhu HH, Gao WQ, et al. A MicroRNA302‐367‐Erk1/2‐Klf2‐S1pr1 pathway prevents tumor growth via restricting angiogenesis and improving vascular stability. Circ Res. 2017;120:85–98. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.116.309757 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Akash MS, Rehman K, Li N, Gao JQ, Sun H, Chen S. Sustained delivery of IL‐1Ra from pluronic F127‐based thermosensitive gel prolongs its therapeutic potentials. Pharm Res. 2012;29:3475–3485. doi: 10.1007/s11095-012-0843-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Lu MM, Li S, Yang H, Morrisey EE. Foxp4: a novel member of the Foxp subfamily of winged‐helix genes co‐expressed with Foxp1 and Foxp2 in pulmonary and gut tissues. Gene Expr Patterns. 2002;2:223–228. doi: 10.1016/s1567-133x(02)00058-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Banham AH, Beasley N, Campo E, Fernandez PL, Fidler C, Gatter K, Jones M, Mason DY, Prime JE, Trougouboff P, et al. The FOXP1 winged helix transcription factor is a novel candidate tumor suppressor gene on chromosome 3p. Cancer Res. 2001;61:8820–8829. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Lu MM, Li S, Yang H, Morrisey EE. Foxp4: a novel member of the Foxp subfamily of winged‐helix genes co‐expressed with Foxp1 and Foxp2 in pulmonary and gut tissues. Mech Dev. 2002;119:S197–S202. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4773(03)00116-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Tian Y, Zhang Y, Hurd L, Hannenhalli S, Liu F, Lu MM, Morrisey EE. Regulation of lung endoderm progenitor cell behavior by miR302/367. Development. 2011;138:1235–1245. doi: 10.1242/dev.061762 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.