Abstract

Titanium dioxide nanoparticles (TiO2NPs) usage is increasing in everyday consumer products, hence, assessing their toxic impacts on living organisms and environment is essential. Various studies have revealed the significant role of TiO2NPs physicochemical properties on their toxicity. However, TiO2NPs are still poorly characterized with respect to their physicochemical properties, and environmental factors influencing their toxicity are either ignored or are too complex to be assessed under laboratory conditions. The outcomes of these studies are diverse and inconsistent due to lack of standard protocols. TiO2NPs toxicity also differs for in vivo and in vitro systems, which must also be considered during standardization of protocols to maintain uniformity and reproducibility of results. This review critically evaluates impact of different physicochemical parameters of TiO2NPs and other experimental conditions, employed in different laboratories in determining their toxicity towards bacteria. These important observations may be helpful in evaluation of environmental risks posed by these nanoparticles and this can further assist regulatory bodies in policymaking.

Keywords: Bacteria, Environment, Physicochemical parameters, TiO2 Nanoparticles, Toxicity

Introduction

Significant biotechnological advancements have been made in environmental and industrial sectors to make human life sustainable [1–4]. However, the recent pandemic attack has demonstrated its impact on human health and increased economic load worldwide. This disastrous activity suggests that more attention needs to be paid to the management of infectious diseases [5–7]. Nanotechnology, make use of nanoparticles (NPs) with unique properties, has the potential to develop new materials having applications in wide areas like biomedicine, food industries, textile manufacturing, enzyme immobilization, bioenergy production, biosensors, agriculture, electronics and telecommunication etc. [8–14]. The synthesis of nanomaterials by various methods i.e. physical, chemical, and biological have led to diverse alteration in their properties and applications [15–20]. According to their size, shape and physicochemical properties, NPs are classified into several categories like metal oxide NPs, carbon-based NPs, polymeric NPs, lipid-based NPs, semiconductor NPs, and ceramic NPs etc. Metal oxide nanoparticles (TiO2, CuO, Fe2O3, ZnO, and others) have gained importance due to their uniform size distribution (10–100 nm) and large surface area. Titanium dioxide nanoparticles (TiO2NPs) are one of the most produced and utilised NPs in commercial products due to their photocatalytic properties and inert nature of TiO2 [21, 22]. Overall, a significant development in nanotechnology is playing a key role in various biotechnological applications for sustainable progress [23–32]. The manufacturing of NPs has expanded dramatically over the last decade, owing to their wide range of uses in everyday items. As a result, these NPs have been released into the environment uncontrollably. The toxic effects of NPs, as well as their fate and transport behavior, govern the probability of NPs being a source of emerging pollutants in the environment. The residues of the products incorporating TiO2NPs are released in the environment at different stages i.e., production, usage and disposal, by different routes like air, rain and sewage [33–35]. When TiO2NPs enter the environment, they undergo various types of physical, chemical and biological transformations. These transformations alter TiO2NPs physicochemical properties due to changes in their surface chemistry which modify their toxicity. TiO2NPs make aggregates in presence of natural organic matter (NOM) that range from nanometres to micrometres and have been reported to adsorb other ligands on their surface further magnifying their toxicity [36]. Also, interactions with macromolecules of flora and fauna tissues form a layer on their surface, known as bio-corona, which gives a biological identity to them [37, 38].

Numerous studies have reported the toxic and adverse effects of TiO2NPs in different organisms like algae, Drosophila, Daphnia, mice, zebrafish, humans etc. [39–47]. Of all organisms, bacteria are ubiquitous and can adapt easily to adverse environmental conditions and pollutants; as a result, NPs interact with them more readily than any other higher organisms. Bacterial contact with NPs can either be toxic, or they can be resistant to them. Bacterial metabolites like enzymes, organic acids, and extracellular polymeric substances (EPS) have been shown to modify the hydrophobicity, charge, and surface properties of nanoparticles. Despite the fact that bacteria lack internalisation mechanisms, as found in eukaryotes, TiO2NPs have been scanned inside the bacterial cells [48]. There are numerous studies which have been conducted to examine toxic impact of TiO2NPs on bacteria, but their ecotoxicological effects are poorly understood due to their limited characterization [38, 49, 50]. Hence, it is crucial to examine how TiO2NPs and bacteria interact in the environment with respect to their physicochemical properties (like stability, size, aggregation, surface charge, optical properties, catalytic behavior, and adsorption capacity) and enviornmental factors. The indiscriminate and widespread use of TiO2NPs has resulted in higher human and environmental exposure but their adverse impact is largely not determined, necessitating the assessment of their ecotoxicological effects [38, 51]. This review evaluates TiO2NPs toxicity towards bacteria and assesses various physicochemical parameters employed during laboratory studies to gain insight into nanoparticle-bacterial interactions in the environment.

Physicochemical Parameters of TiO2NPs

The major physicochemical parameters that influence the toxicity of TiO2NPs include pH, ionic strength (IS), size, surface charge, crystal structure, components of the media, aggregation, optical properties, catalytic behavior, zeta potential, and solar radiations (UVA region).

Ionic Strength and pH

Nanoparticles never remain in their native state, they form aggregates that modify their size, surface area and other physicochemical properties [52]. Toxicity of TiO2NPs in a solution is highly influenced by IS i.e. total ion concentration and pH. According to Derjaguin-Landau-Verwey-Overbeek (DLVO) theory, the aggregation of NPs depends on the isoelectric point and pH of the solution [53]. The attractive van der Waals forces between TiO2NPs and an increased IS of solution, decreases the zeta potential and thickness of the electric double layer (electrostatic forces), resulting in enhanced aggregation [54]. The surface charge of TiO2NPs in aqueous suspension depends upon the surface ionization, which changes with the pH of solution. TiO2NPs can be positively or negatively charged at lower and higher pH, respectively, whereas, they have no net charge at the isoelectric point [53]. TiO2NPs have been reported to form aggregates of several hundred nanometers to micrometers depending on the nature of electrolytes and ionic strength of aqueous solution in acidic pH range, for example, TiO2NPs of 4–5 nm size are reported to readily form stable aggregates of diameter 50–60 nm at pH 4.5 in 4.5 M NaCl. But raising the ionic strength to 16.5 M while keeping the pH constant, results in 20–1000 nm micro-size aggregates, which have been shown to be toxic to bacteria [55]. In surface waters and soil, the presence of low concentrations of divalent cations (e.g., Ca2+, Mg2+) magnify this effect and speeds up the production of these micro-sized aggregates. At high NaCl concentrations, NPs adsorb on the bacterial cell surface more efficiently leading to cell death. The mechanisms involved have been studied through various molecular approaches like transcriptomics, and proteomics along with biochemical analysis. It has been shown that during these enhanced interactions, depolarization of cell membrane occurs, which in turn increases the efflux of potassium and magnesium ions with simultaneous influx of sodium ions and ATP depletion [56]. It has been reported in a recent study that increasing pH to 7, increases the antibacterial activity of TiO2NPs modified with dendrimers in case of Staphylococcus aureus and Escherichia coli [57]. In most toxicological studies, for optimum bacterial growth, pH is maintained between 5 and 7; however, homogenous TiO2NPs suspensions, with strong repulsive forces can be achieved only at acidic pH to prevent aggregation [58]. As a result, standardising the pH of the solutions used in toxicological studies is critical.

Salts and Natural Organic Matter

In addition to NPs, many monovalent and divalent salts play an important role in bacterial aggregation, e.g., Ca2+ causes bacterial aggregation in mouth resulting in dental plaque formation [59]. Also, in an aqueous solution, salts like Al3+ have been reported to dissociate and adhere to the surfaces of NPs and bacteria, neutralising their surface charges, resulting in the formation of large flocs as seen in sewage treatment plants [50]. At alkaline pH, TiO2NPs have a negative charge, however, if the salt concentration is high, such as 0.1 M NaCl, TiO2NPs and bacteria interact well [58]. The divalent cations (like Ca2+) lead to higher TiO2NPs aggregation, for example, 0.0128 M CaCl2 in solution changes the zeta potential from positive to negative and causes TiO2NPs to aggregate more efficiently than 0.0125 M NaCl [55]. Therefore, during TiO2NPs toxicology studies, it is critical to examine different types of salts and their concentrations. NOM has a high hydrophobicity and carries several functional groups with a strong affinity for metal oxide surfaces in water. The presence of NOM, like fulvic and humic acids, in water reservoirs like sea, lagoons, rivers and groundwater, also affect the aggregation, steric repulsion and electrophoretic mobility (EM) of TiO2NPs [36]. There are higher chances of formation of large-sized aggregates and less EM of TiO2NPs in seawater with high IS and low NOM [53]. As a result, TiO2NPs are not as reactive in the environment as they are in laboratory experiments, due to the existence of NOM, which operates as a protective shell surrounding these NPs. NOM prevent direct contact of NPs with living organisms and also reduce the adverse effects caused by reactive oxygen species (ROS) [60]. Therefore, it is important to examine both organic and inorganic environmental factors that influence the impact of these NPs on organisms in the laboratory conditions to make accurate risk assessments.

Sonication

Probe sonication is a commonly used method for dispersion of TiO2NPs in an aqueous solution and for dissociation of their agglomerates. Due to probe sonication, initially the hydrodynamic diameter decreases but then increases with time. The hydrodynamic diameter of TiO2NPs is higher in solution (90 nm) as compared to the normal particle size (25 nm), leading to their increased toxicity [61]. Probe sonication has been reported to not only disperse TiO2NP agglomerates in solution, but it also induces agglomeration due to increased particle-particle interaction and thus influences their toxicity [61, 62].

Since TiO2NPs aggregation is primarily determined by pH and IS of the solution, probe sonication never creates uniformly dispersed nanoparticles. When sonicated TiO2NPs suspension is transferred from a stock solution to a working solution, it leads to variations in pH, IS and other physicochemical properties of TiO2NPs such as size, surface area and zeta potential, creating their heterogeneous distribution [63]. A major reason of variation in TiO2NPs suspension properties is the lack of consistency in the standardization of sonication in different laboratories. Hence, it is critical to either use pulsed probe sonication or directly add powdered TiO2NPs along with bacteria to carry out toxicological analysis in laboratories.

Size, Optical Properties and Crystal Structure

NPs possess optical properties such as transmission, absorption, reflection and light emission, which depend on their electron configuration. Although, TiO2NPs show phototoxicity via generation of ROS, they are also used for photodegrading organic pollutants and toxic dyes in the environmental samples by ultraviolet (UV) light [64]. They can be doped with several metals/non-metals such as Fe (III), Co (II), Ni (II), Ag (I), C, N and S etc., to shift the band edge for better absorption efficiency [65–67]. For example, CdS@TiO2 (CT) nanocomposites are better photocatalysts than TiO2NPs alone, since in composites, the absorption band edge is shifted towards visible region, which makes photocatalytic degradation of pollutants in industrial waste samples more efficient [68]. Similarly, Fe-doping of TiO2NPs at concentrations as low as 0.1% has been reported to enhance their photocatalytic activities by inducing photogenerated pores and photoexcited electrons. These photogenerated pores produce highly oxidizing species which are toxic to bacteria [69]. The coating of silica (SiO2) leads to dipole formation at rutile TiO2NPs: SiO2 junction, leading to an increased photoexcited electrons positive charge of rutile TiO2NPs and is found to be coat thickness dependendent. This enhances the interactions between the bacterial cell surface and TiO2NPs resulting in an increased photocatalytic and antibacterial properties [70]. While SiO2 modified TiO2NPs have reduced toxic effects at lower concentrations on the higher organisms but an increase in their ratio (TiO2:SiO2 3:1) can damage these cells due to ROS production leading to cell necrosis, cell cycle arrest and DNA damage etc. [71]. Upon activation by UV and visible light, TiO2NPs show increased cytotoxicity but, in a size dependent manner i.e., smaller the size of NPs, higher is the toxicity. Higher toxicity of small TiO2NPs is due to their large surface area per ml and a very strong correlations (R2 = 0.9 and above) between the surface area and toxicity has been reported. Thus, overall toxicity, cell membrane damage and ROS production of TiO2NPs can be attributed to a large extent to their surface area and size [72].

There are four major crystal forms of TiO2NPs: rutile (stable; tetragonal), anatase (metastable; tetragonal), brookite (rhombohedral) and TiO2-B (monoclinic), which exhibit different properties. For example, the anatase and brookite forms are more stable in nanoscale dimensions and rutile and anatase forms of TiO2NPs with the same size have the same toxicity towards E. coli [73, 74]. However, the anatase form of TiO2NPs is more photocatalytically active and shows higher toxicity when exposed to UV light due to induced oxidative stress to the cells [75]. Furthermore, rod-shaped TiO2NPs are more toxic than spherical particles of the same size and surface area, demonstrating that the shape of NPs plays an important role in toxicity [46]. As a result, while investigating the ecotoxicity of TiO2NPs, a detailed and careful evaluation of their crystal structure must be carried out.

Adsorption Capacity

NPs with higher adsorption capacity have the potential to be used for recovering pollutants from waste waters and to enhance the adsorption capacity of NPs their surface modifications are carried out by using different types of dopants. Dopants create charge space carrier regions on the surface of TiO2NPs leading to accelerated production of -OH radicals and increased rate of photocatalysis. They also act as active sites for adsorption of pollutants on their surface, and thus enhance the rate of photodegradation [76]. The adsorption capacity of TiO2NPs may be improved by synthesizing TiO2 nanopowder at low temperatures (nearly 100 °C) and alkaline pH resulting in porous TiO2NPs with high surface area and high adsorption capacity [77]. Photoactivation of TiO2NPs leads to production of ROS and adsorption of biomolecules on their surface, the two major reasons for their toxicity. Proteins and other macromolecules easily get adsorbed onto the TiO2NPs surface, thereby giving them a new biological identity, which may be toxic. More protein molecules get adsorbed on smaller sized NPs because of their large surface area. For example, chitosan-TiO2 composite film was formed by TiO2 nanopowder which resulted in reduced transmission of visible light and enhanced photocatalytic antimicrobial properties of these composites, leading to improved shelf life of packaged food [78]. However, coating TiO2NPs with compounds like poly (ethylene-alt-maleic anhydride) (PEMA) lowers their adsorption capability as it hinders biomolecule adsorption and leads to the generation of hydroxyl radical (OH−) during photoactivation [72].

Surface Charge

Surface of TiO2NPs shows a strong positive charge at pH 3.0 and the point of zero charge (PZC) is attained at pH 5.8−6.2 (pHPZC). At pH above pHPZC, the overall charge on TiO2NPs becomes negative [79]. The positively charged TiO2NPs show more toxicity than negatively charged NPs. Bacteria in aqueous solution have negative charge on their surface due to membrane phospholipids, whereas TiO2NPs have a positive charge, resulting in strong electrostatic interactions among them. Hence, toxicity of TiO2NPs decreases with increasing pH (5−10) [75]. Therefore, during the laboratory studies, the agglomeration of NPs should also be considered as an important factor contributing to the levels of complexity [61].

Catalytic Behavior

The most significant catalysis shown by TiO2NPs is photocatalysis, whereby they degrade dyes, phenolic compounds and other pollutants upon photoactivation. Factors such as concentration of pollutants, concentration of catalysts and pH influences photocatalysis. pH influences aggregation of catalysts, generation of OH− radicals, charge on catalysts etc. [80]. TiO2 nanotubes are more effective pollutant scavengers as compared to TiO2NPs, as the former shows dual activity i.e., better adsorption efficiency and photocatalysis [81]. There have been recent advances in the TiO2NPs based photocatalysis, where strategies such as doping with cations and anions; codoping with cations and anions; self-doping with Ti3+ and doping with metals has been carried out, leading to enhanced photocatalysis potential of TiO2NPs [82]. For example, Fe–Ag co-doped TiO2NPs are outstanding in their performance for removal of flumioxazin pesticide residues [83]. TiO2NPs are also used as catalysts for production of pharmacologically important substances such as pyrimido [4,5-d] pyrimidines [84].

The physicochemical parameters of TiO2NPs control their reactivity and bioavailability, which has a significant impact on their environmental toxicity. Therefore, taking into account these parameters is pivotal while studying their adverse effects on organisms in laboratories and to understand ecotoxicological impacts of these NPs (Fig. 2).

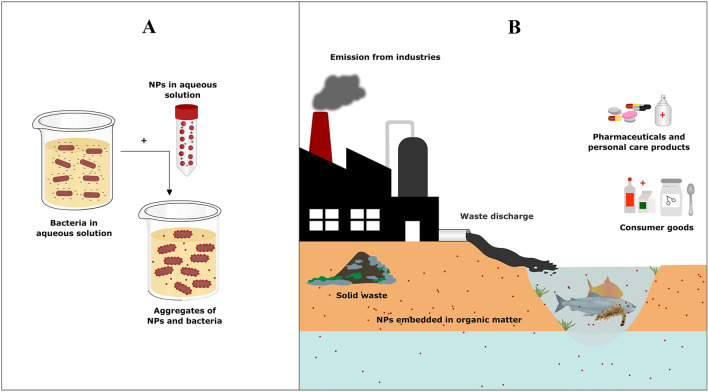

Fig. 1.

Schematic representation to depict differences between laboratory and environmental conditions to study nanoparticles (NPs) and bacterial interactions. A Under laboratory conditions, NPs are used in pure form and high concentrations with optimum pH and ionic strength. Bacteria are also devoid of any stress or interspecies competition. B In the environment, NPs combine with inorganic and organic material as well as experience fluctuating pH and ionic strength. Bacteria also experience competitive inhibition from other organisms

Fig. 2.

Various physicochemical properties affecting nanoparticle toxicity on bacteria and other organisms

Bacterial Characteristics and Behavior in Aqueous Media

To understand the toxic effects of TiO2NPs on bacteria, it is important to study the behavior of bacteria in aqueous media. Gram-positive bacteria have a thicker cell wall and can withstand higher concentrations of TiO2NPs than Gram-negative ones. The standard procedure used to check the toxicity of TiO2NPs towards bacteria in laboratories is to mix both in physiological water, incubate at optimum temperature for specific time intervals and then determine percentage survival of the cells.

It is imperative to examine bacterial survival in a given IS solution as they behave like charged particles in solution due to ionizing macromolecules present on their cell wall and membrane and follow the extended DLVO theory like NPs [85, 86]. As IS rises, the electric double layer shrinks and van der Waals forces take over, leading to cell aggregation which is influenced by the valence of cations in the solution. However, one significant distinction between TiO2NPs and bacteria is that the latter are living organisms with extremely dynamic surface properties, mostly resistant to external factors and can deviate from the DLVO principle [85]. Also, bacterial surfaces are more complex than non-biological colloids due to EPS like polysaccharides, glycoprotein, and lipopolysaccharides released by bacteria which provide an extra layer of defence [87]. The physicochemical properties like pH and IS of the medium have a substantial effect on the adsorption of EPS on TiO2NPs surfaces, which in turn influences the aggregation behavior of TiO2NPs. Also, aggregation rate of TiO2NPs decreases in the presence of EPS due to steric repulsion which prevents the adsorption of EPS onto NPs and it has been shown that the aggregation can be completely stopped in high IS concentrations e.g., 50 mM NaCl along with 10 mg L−1 EPS in Bacillus substilis [52]. Thus, presence of EPS in the bacterial biofilms provides protection from the toxic effects of NPs.

TiO2NPs-Bacterial Interactions

As discussed above, pH, IS, NOM, and valence of cations, all affect the stability of TiO2NPs and bacteria. What happens if both TiO2NPs and bacteria are present in the same solution? They can either attract or repel each other or stay independent. Several investigations have shown toxicity of TiO2NPs towards E. coli, due to cell lysis, as demonstrated through TEM (Transmission electron microscopy) and SEM (Scanning electron microscopy) studies [21, 88–90]. Surprisingly, very few studies in literature illustrate the effects of these physicochemical parameters on TiO2NPs-bacterial interactions. NPs exhibit change in their toxicity towards bacteria in culture media, owing to the presence of media particles, changes in bacterial surface characteristics during growth, and media components affecting bacterial physicochemical properties [91]. For example, the presence of peptone and yeast extract have a considerable influence on the Lactobacillus acidophilus cell wall. Changes in concentrations of these media components have significant effects on surface charges, hydrophobicity, and nitrogen-to-carbon ratio of cell walls [92]. Zeta potential of the bacterial surface depends upon the number of ionisable groups on their surface and factors like pH and IS. Enterococcus faecalis strains show pH-dependent culture heterogeneity in cell surface charges, which is independent of aggregation substances (Aggs), enterococcal surface protein (encoded by the esp gene), growth medium or growth phase [93, 94]. Thus, characterization of bacterial surface physicochemical properties is significant during in vitro TiO2NPs toxicological studies.

Only few reports focused on E. coli are available that compare the surface properties of various bacteria in relation to physicochemical properties of TiO2NPs. Therefore, there is a pressing need to investigate the impact of these NPs on other environmental bacterial strains. For example, C. metallidurans, a heavy metal-resistant environmental strain with unique cell wall compositions and a powerful efflux mechanism (gene duplication/horizontal gene transfer) is observed to be resistant to TiO2NPs [95].

Toxicity of TiO2NPs towards bacteria is assessed in control and test samples by comparing the number of viable to dead cells but other effects like bacterial behavior, their physiological activities are generally ignored. As surface characteristics and zeta potential fluctuate with the growth kinetics of bacteria, it is critical to relate the toxicity of TiO2NPs with different bacterial growth phases. Furthermore, most studies have used high concentrations of TiO2NPs (100−500 mg/L) against bacteria but these high concentrations are rarely found in the environment [21, 96]. The long-term effects of low concentrations of TiO2NPs on bacteria are generally overlooked due to relatively short incubation periods (24−48 h) used in laboratories, ageing effects of NPs due to surrounding environment and altered absorption capacity and photosensitivity [97]. Hence, new methodologies or approaches must be developed to assess the toxicological impacts of NPs to draw clear inferences.

Mechanism of TiO2NPs Toxicity

The mechanisms of TiO2NPs toxicity against bacteria are still debated. Nonetheless, it is well-established that TiO2NPs produce ROS like hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), hydroxyl free radical (OH•−) and superoxide anions (O2•−) in the presence of UV light in an aqueous environment, which leads to bacterial cell surface modification and mortality [8, 98]. The mechanism of ROS generation is influenced by size, shape, surface area, and other physicochemical properties of TiO2NPs. Due to their large surface area, small NPs produce more ROS and are more toxic. Excess ROS generation, decreased antioxidants and glutathione (GSH) levels, and increased lipid peroxidation, are the major signs of oxidative stress. The bacterial cell wall and membrane have been shown to be damaged by oxidative stress, which alters their permeability through membrane depolarization and loss of integrity [21, 99]. When exposed to ROS, two oxidative stress genes (Kat A and Ahp C) and a general stress response gene (Dna K) have been shown to increase their expression levels by 52, 7, and 17 times, respectively [100]. Bacterial cell walls and membranes are the first line of defence, they provide a protective barrier, assisting bacteria in maintaining their morphology and physiological activities. ROS cause damage to the bacterial cell wall by oxidising organic components such as lipopolysaccharide, phosphatidylethanolamine and peptidoglycan, due to their vulnerability to TiO2NPs induced peroxidation [101]. As a consequence of cell membrane damage by TiO2NPs, the mitochondrial respiratory chain is also disturbed [98]. Although, mitochondria produce superoxide anions as natural by-product of the electron transfer respiratory chain, mitochondrial enzymes such as superoxide dismutase (SOD), glutathione peroxidase, and catalase convert them to H2O2 and finally into water. But due to TiO2NPs induced large production of ROS, these enzymes are unable to counteract the damage, like triggering protein denaturation and cytoplasm leakage [102]. DNA is highly susceptible to ROS radicals, which attack the sugar phosphate bonds, causing DNA strand breaks. For bacteria, this molecular level damage is extremely detrimental since it impacts all critical cellular functions, jeopardising the cellular integrity and ultimately leading to cell death [101]. The above-mentioned physicochemical properties of TiO2NPs influence ROS production and hence their toxicological effects.

Apart from ROS, TiO2NPs impart their toxicological effects by attaching to bacteria. The exact mechanism of toxicity is unknown; however, it is assumed that multilayers of NPs on the bacterial surface may block the ion channels, resulting in osmotic imbalance [21]. In a recent study, E. coli has been shown to produce membrane vesicles and repair damaged cell membrane parts to overcome this osmotic imbalance [21]. These new insights into bacterial defence mechanisms need to be further investigated in order to better understand, not just the interactions between TiO2NPs and microbes in the environment, but also to combat antimicrobial resistance (AMR).

Methods to Assess TiO2NPs Toxicity

Toxicity of a particular compound towards bacteria can be checked by CFU count, however, this method is not suitable to assess TiO2NPs toxicity as they make aggregates with bacteria, which cannot be broken down by simple vortexing. Hence, colonies arising on media plates, after a particular incubation time, are not derived from a single cell but from a collection of cells, which can mislead the results. Commonly used methods for assessment of bacterial susceptibility or resistance to antimicrobials such as TiO2NPs are growth inhibition assay, disc diffusion assay, BacLight assay, SEM and TEM [96, 97]. TiO2NPs induced ROS production, (hydroxyl radicals, hydrogen peroxide and peroxyl radicals) can be measured by using the probe 2',7'-dichlorodihydrofluorescein diacetate (H2DCF-DA). This is a non-fluorescent dye but when it diffuses through bacterial plasma membrane, it is hydrolysed by cellular esterases and converts into 2,7-dichlorodihydrofluorescein (DCFH). DCFH is further converted into fluorescent 2,7- dicholorofluorescein (DCF) which can be detected by absorption or fluorescence spectroscopy [103, 104]. Also, bacterial cell membrane damage and cell morphology changes caused by ROS can be measured by lipid peroxidation assay and field emission scanning electron microscopy (FESEM), respectively [98]. A powerful method for evaluating spatially resolved TiO2NPs effects on bacterial biosurface nanomechanics at single-cell level is done by multiparametric atomic force microscopy/spectroscopy (AFM). It also incorporates electrophoretic cell fingerprinting into the context of TiO2NPs toxicity assessment at a level that goes beyond the usual zeta-potential approach, which is ineffective for deciphering the electrokinetic features of soft (ion and flow-permeable) bacterial surfaces [21]. Various methods and parameters used in different toxicology studies of TiO2NPs vary in different laboratories, therefore, it is essential to standardize physicochemical parameters and methods, to understand the actual behavior of NPs towards bacteria under native conditions for more effective and conclusive ecotoxicological studies (Table.1).

Table 1.

Different methods used to assess the toxicity of some commonly used NPs towards bacteria

| NPs | Size(nm)/morphology | Model bacteria | Experimental conditions | Toxicity | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CuO | > 50/na | Nitrifying bacteria in soil | Sonicated NPs used to assess NEA and DEA in soil microcosms. Microbial abundance measured by qPCR | NEA and DEA reduced by ~ 50% and ~ 40%, respectively, after 90 days exposure to upto 100 mg Kg−1 NPs | [105] |

| Ag | 10–50/spherical | Azotobacter vinelandii | Bacteria exposed to NPs on solid media and flow cytometry, nitrogenase activity, ROS production used to assess toxicity | 0.1 mg L−1 NPs inhibited bacterial growth and fourfold increase in ROS production after 4 h treatment and upto 60% reduction in nitrogenase activity | [106] |

|

10–80/spherical 30–60/spherical |

Escherichia coli Pseudomonas aeruginosa Escherichia coli Streptococcus aureus |

Resting cells exposed to NPs. LIVE/DEAD BacLight test, ATP production assay and flow cytometry used to check toxicity Bacterial cells exposed to NPs and growth inhibition checked by Kirby-Bauer method |

Dose-dependent toxicity, upto 2.5 mg L−1 NPs inhibited P. aeruginosa growth, 80 mg L−1 NPs inhibited E. coli K12 growth and delayed exponential phase NPs showed zone of inhibition in the range of 2.2 cm for S. aureus and 2.1 cm against E. coli. MIC was found to be ~ 30 µM |

[107–109] | |

| CuO, NiO, ZnO and Sb2O3 | 10–210/na |

Escherichia coli Bacillus subtilis Streptococcus aureus |

Bacteria exposed to sonicated NPs dispersed in agar medium and toxicity checked by CFU method | Maximum growth inhibition of upto 90% was seen with CuO NPs (125 mg L−1) and minimum was seen with ZnO NPs (upto 60%) | [110] |

| Al2O3 | < 50/na | Pseudomonas putida | Bacteria exposed to sonicated NPs and growth inhibition checked by turbidity method | 200 mg L−1 NPs showed ~ 80% growth inhibition | [111] |

| < 50/spherical | Soil Microorganisms | Microcalorimetric measurements and urease activity | Low toxicity below 100 µg mL−1; toxicity increased with increased concentration | [112] | |

| Au | 16/spherical | Salmonella typhimuriumCHO cells | Growth inhibition and mutagenic test was conducted in the presence of light and in the dark | No toxicity in S. typhimurium. NPs were photo-mutagenic due to the presence of Au+ citrate ions. Concentration upto 50 µg mL−1 could induce substantial DNA damage (~ 20%) in CHO cells | [113] |

| TiO2 | 6/spherical |

Escherichia coli Bacillus subtilis |

Resting cells exposed to sonicated NPs (pH and ionic strength measured). Toxicity checked by CFU method Disc diffusion method, ROS generated DCF, PI and SYTO9 fluorescent dyes for viable cell count |

Growth inhibition of upto 80% was seen with TiO2NPs (100 mg L−1) MIC was found to be ~ 200 µg mL−1 |

[96, 98] |

| Fe3O4 | 50/spherical | Vibrio fischeri | Acute toxicity levels were analysed using Microtox bioassay | Pure Fe3O4 showed higher acute toxicity (EC50 ~ 250 µg mL−1) | [114, 115] |

|

30–50/spherical, and 1–3 µm/yolk-shell |

Yolk-shell (EC50 ~ 650 µg mL−1) less toxic than pure Fe3O4 (EC50 ~ 350 µg mL−1) | ||||

| Au-peptide | 25/spherical |

Staphylococcus aureus, Bacillus cereus, Enterococcus faecalis |

Agar diffusion assay | Au-peptide showed zone of inhibition in the range of 22–25 mm | [116] |

| CELE-Ag | 15/spherical | Staphylococcus aureus, Bacillus cereus, Enterococcus faecalis, Candida tropicalis, Candida krusei, Candida lusitaniae, Candida guilliemondii, Penicillium chrysogenum | Agar diffusion assay | CELE-AgNPs showed zone of inhibition in the range 10–24 mm | [117] |

| Ag-composite | 15/spherical | Staphylococcus aureus, Escherichia coli | CFU method | MIC of Ag-GSiO2 NPs was 0.3 mg mL−1 for S. aureus and 0.35 mg mL−1 for E. coli | [118] |

| Fe-composite | 100/spherical | Vibrio fischeri | Acute toxicity levels were analysed using Microtox bioassay | EC50 values upto 415 μg/mL after 15 min | [119] |

na Data or information is not available

Conclusions and Future Directions

In twenty-first century, TiO2NPs have widespread applications, but they also pose tremendous challenges for scientists, owing to their ecotoxicological effects. Bacteria are ideal model systems for assessing the toxicity of novel antimicrobials and other eco-toxic compounds. Although, TiO2NPs toxicity has been extensively documented from laboratory studies on E. coli and other bacteria, their harmful effects in the environment are not well understood. As TiO2NPs toxicity depends on their physicochemical properties and bacterial surface characteristics, it is critical to consider bacterial physiology in different aqueous media of specific IS and pH; however, these parameters are often neglected during in vitro studies. Gaps in toxicological studies must be addressed, and new standardised methodologies for investigating the harmful effects of TiO2NPs on bacteria must be developed and designed. All these efforts are warranted in order to do a risk assessment of TiO2NPs ecotoxicity. Nanoparticles are promising antimicrobial alternative to combat AMR. They can act synergistically with a wide variety of antibiotics, to augment the antibacterial activity of traditional antibiotics. However, their toxicological effects must be thoroughly investigated before they can be used as an alternative antimicrobials. Green synthesis of TiO2NPs, an environment friendly approach for the production of non-toxic NPs, can be helpful in the production of safer and more stable NPs and tap their full potential for various ecological engineering and commercial applications. Hence, characterization of TiO2NPs and bacteria is important to better understand their interactions in a holistic manner.

Acknowledgements

PS, RK and MY acknowledge Gargi College, Miranda House and Maitreyi College, University of Delhi, Delhi, India, respectively for providing infrastructural support.

Abbreviations

- NPs

Nanoparticles

- TiO2NPs

Titanium dioxide nanoparticles

- NOM

Natural organic matter

- EPS

Extracellular polymeric substances

- IS

Ionic strength

- DLVO

Derjaguin, Landau, Verwey, and Overbeek

- EM

Electrophoretic mobility

- ROS

Reactive oxygen species

- PZC

Point of zero charge

- GSH

Glutathione

- TEM

Transmission electron microscopy

- SEM

Scanning electron microscopy

- SOD

Superoxide dismutase

- AMR

Antimicrobial resistance

- CFU

Colony forming units

- H2DCF-DA

2',7'-Dichlorodihydrofluorescein diacetate

- DCFH

2,7-Dichlorodihydrofluorescein

- DCF

2,7- Dicholorofluorescein

- FESEM

Field emission scanning electron microscopy

- AFM

Atomic force microscopy/spectroscopy

- NEA

Nitrification enzyme activity

- DEA

Denitrification enzyme activity

- CHO

Chinese hamster ovary cells

- MIC

Minimum inhibitory concentration

- EC50

Half maximal effective concentration

Author Contributions

PS and RK designed and wrote the manuscript. MY contributed in writing and proof reading.

Funding

Not Applicable.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Poonam Sharma and Rekha Kumari contributed equally to this work.

Contributor Information

Poonam Sharma, Email: poonam.sharma@gargi.du.ac.in.

Rekha Kumari, Email: rekha.kumari@mirandahouse.ac.in.

References

- 1.Patel SKS, Gupta RK, Kumar V, et al. Biomethanol production from methane by immobilized cocultures of methanotrophs. Indian J Microbiol. 2020;60:318–324. doi: 10.1007/s12088-020-00883-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kalia VC, Patel SKS, Cho B-K, et al. Emerging applications of bacteria as anti-tumor agents. Sem Cancer Biol. 2021 doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2021.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Patel SKS, Shanmugam R, Lee J-K, et al. Biomolecules production from greenhouse gases by methanotrophs. Indian J Microbiol. 2021;61:449–457. doi: 10.1007/s12088-021-00986-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Patel SKS, Das D, Kim SC, Cho B-K, Lee J-K, Kalia VC. Integrating strategies for sustainable conversion of waste biomass into dark-fermentative hydrogen and value-added products. Renew Sustain Energy Rev. 2021;150:111491. doi: 10.1016/j.rser.2021.111491. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Patel SKS, Lee J-K, Kalia VC. Deploying biomolecules as anti-COVID-19 agents. Indian J Microbiol. 2020;60:263–268. doi: 10.1007/s12088-020-00893-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rishi P, Thakur K, Vij S, et al. Diet, gut microbiota and COVID-19. Indian J Microbiol. 2020;60:420–429. doi: 10.1007/s12088-020-00908-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Thakur V, Bhola S, Thakur P, et al. Waves and variants of SARS-CoV-2: understanding the causes and effect for COVID-19 catastrophe. Infection. 2021 doi: 10.1007/s15010-021-01734-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pagolu R, Singh R, Shanmugam R, et al. Site-directed lysine modification of xylanase for oriented immobilization onto silicon dioxide nanoparticles. Bioresour Technol. 2021;331:125063. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2021.125063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Patel SKS, Gupta RK, Kim S-Y, et al. Rhus vernicifera laccase immobilization on magnetic nanoparticles to improve stability and its potential application in bisphenol A degradation. Indian J Microbiol. 2021;61:45–54. doi: 10.1007/s12088-020-00912-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ziental D, Czarczynska-Goslinska B, Mlynarczyk DT, et al. Titanium dioxide nanoparticles: prospects and applications in medicine. Nanomaterials. 2020;10(2):387. doi: 10.3390/nano10020387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bayda S, Adeel M, Tuccinardi T, et al. The history of nanoscience and nanotechnology: from chemical-physical applications to nanomedicine. Molecules. 2019;25:112. doi: 10.3390/molecules25010112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kumar A, Park GD, Patel SKS, et al. SiO2 microparticles with carbon nanotube-derived mesopores as an efficient support for enzyme immobilization. Chem Eng J. 2019;359:1252–1264. doi: 10.1016/j.cej.2018.11.052. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Otari SV, Patel SKS, Kim S-Y, et al. Copper ferrite magnetic nanoparticles for the immobilization of enzyme. Indian J Microbiol. 2019;59:105–108. doi: 10.1007/s12088-018-0768-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kalia VC (2015) Microbes: The most friendly beings? In: Kalia VC (Ed.) Quorum sensing vs quorum quenching: a battle with no end in sight, pp 1–5. Springer, India. doi:10.1007/978-81-322-1982-8_1

- 15.Ray S, Patel SKS, Singh M, Singh GP, Kalia VC (2019) Exploiting polyhydroxyalkanoates for tissue engineering. In: Kalia VC (Ed.) Biotechnological Applications of Polyhydroxyalkanaotes. Springer, Singapore, pp 271–282. 10.1007/978-981-13-3759-8_10

- 16.Kalia VC, Ray S, Patel SKS, Singh M, Singh GP, (2019) Applications of polyhydroxyalkanoates and their metabolites as drug carriers. In: Kalia VC (Ed.) Biotechnological Applications of Polyhydroxyalkanaotes. Springer, Singapore, pp 35–48. 10.1007/978-981-13-3759-8_3

- 17.Patel SKS, Kim JH, Kalia VC, et al. Antimicrobial activity of amino-derivatized cationic polysaccharides. Indian J Microbiol. 2019;59:96–99. doi: 10.1007/s12088-018-0764-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Otari SV, Patel SKS, Kalia VC, et al. One-step hydrothermal synthesis of magnetic rice straw for effective lipase immobilization and its application in esterification reaction. Bioresour Technol. 2020;302:122887. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2020.122887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kalia VC, Patel SKS, Shanmugam R, et al. Polyhydroxy alkanoates: trends and advances towards biotechnological applications. Bioresour Technol. 2021;326:124737. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2021.124737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Patel SKS, Kalia VC. Advancements in the nanobiotechnological applications. Indian J Microbiol. 2021;61:401–403. doi: 10.1007/s12088-021-00979-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pagnout C, Razafitianamaharavo A, Sohm B, et al. Osmotic stress and vesiculation as key mechanisms controlling bacterial sensitivity and resistance to TiO2 nanoparticles. Commun Biol. 2021;4(1):678. doi: 10.1038/s42003-021-02213-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Patra JK, Das G, Fraceto LF, et al. Nano based drug delivery systems: recent developments and future prospects. J Nanobiotechnol. 2020;16:71. doi: 10.1186/s12951-018-0392-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Anwar MZ, Kim DJ, Kumar A, et al. SnO2 hollow nanotubes: a novel and efficient support matrix for enzyme immobilization. Sci Rep. 2017;7:15333. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-15550-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Otari SV, Kumar M, Anwar MZ, et al. Rapid synthesis and decoration of reduced graphene oxide with gold nanoparticles by thermostable peptides for memory device and photothermal applications. Sci Rep. 2017;7:10980. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-10777-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Patel SKS, Otari SV, Kang YC, et al. Protein-inorganic hybrid system for efficient his-tagged enzymes immobilization and its application in L-xylulose production. RSC Adv. 2017;7:3488–3494. doi: 10.1039/c6ra24404a. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kumar A, Kim I-W, Patel SKS, et al. Synthesis of protein-inorganic nanohybrids with improved catalytic properties using Co3(PO4)2. Indian J Microbiol. 2018;58:100–104. doi: 10.1007/s12088-017-0700-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Patel SKS, Lee JK, Kalia VC. Nanoparticles in biological hydrogen production: an overview. Indian J Microbiol. 2018;58:8–18. doi: 10.1007/s12088-017-0678-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Patel SKS, Otari SV, Li J, et al. Synthesis of cross-linked protein-metal hybrid nanoflowers and its application in repeated batch decolorization of synthetic dyes. J Hazard Mater. 2018;347:442–450. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2018.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kumar V, Patel SKS, Gupta RK, et al. Enhanced saccharification and fermentation of rice straw by reducing the concentration of phenolic compounds using an immobilization enzyme cocktail. Biotechnol J. 2019;14:1800468. doi: 10.1002/biot.201800468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Patel SKS, Choi H, Lee J-K. Multi-metal based inorganic–protein hybrid system for enzyme immobilization. ACS Sustain Chem Eng. 2019;7:13633–13638. doi: 10.1021/acssuschemeng.9b02583. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Patel SKS, Gupta RK, Kumar V, et al. Influence of metal ions on the immobilization of β-glucosidase through protein-inorganic hybrids. Indian J Microbiol. 2019;59:370–374. doi: 10.1007/s12088-019-0796-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Patel SKS, Jeon MS, Gupta RK, et al. Hierarchical macro-porous particles for efficient whole-cell immobilization: application in bioconversion of greenhouse gases to methanol. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2019;11:18968–18977. doi: 10.1021/acsami.9b03420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Khan I, Saeed K, Khan I. Nanoparticles: properties, applications and toxicity. Arab J Chem. 2019;12(7):908–931. doi: 10.1016/j.arabjc.2017.05.011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bundschuh M, Filser J, Lüderwald S, et al. NPs in the environment: Where do we come from, where do we go to? Environ Sci Europe. 2018;30:6. doi: 10.1186/s12302-018-0132-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tolaymat T, Abdelraheem W, Badawy AE, et al. The path towards healthier societies, environments, and economies: a broader perspective for sustainable engineered nanomaterials. Clean Technol Environ Policy. 2016;18:2279–2291. doi: 10.1007/s10098-016-1146-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Danielsson K, Gallego-Urrea JA, Hassellov M, et al. Influence of organic molecules on the aggregation of TiO2 nanoparticles in acidic conditions. J Nanopart Res. 2017;19(4):133. doi: 10.1007/s11051-017-3807-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Juárez-Maldonado A, Tortella G, Rubilar O, et al. Biostimulation and toxicity: the magnitude of the impact of nanomaterials in microorganisms and plants. J Adv Res. 2021;31:113–126. doi: 10.1016/j.jare.2020.12.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Georgantzopoulou A, Carvalho PA, Vogelsang C, et al. Ecotoxicological effects of transformed silver and titanium dioxide nanoparticles in the effluent from a lab-scale wastewater treatment system. Environ Sci Technol. 2018;52(16):9431–9441. doi: 10.1021/acs.est.8b01663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bameri L, Sourinejad I, Ghasemi Z, et al. Toxicity of TiO2 nanoparticles to the marine microalga Chaetoceros muelleri Lemmermann, 1898 under long-term exposure. Environ Sci Pollut Res. 2022 doi: 10.1007/s11356-021-17870-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Alaraby M, Hernández A, Marcos R. Novel insights into biodegradation, interaction, internalization and impacts of high-aspect-ratio TiO2 nanomaterials: a systematic in vivo study using Drosophila melanogaster. J Hazard Mater. 2021;409:124474. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2020.124474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Baranowska-Wójcik E, Szwajgier D, Oleszczuk P, et al. Effects of titanium dioxide NPs exposure on human health-a review. Biolog Trace Element Res. 2020;193:18–129. doi: 10.1007/s12011-019-01706-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Dar GI, Saeed M, Wu A (2020) Toxicity of TiO2 Nanoparticles. In: Wu A, Ren W (Eds.) Applications in nanobiotechnology and Nanomedicine. Wiley Online Library, pp 67–103. 10.1002/9783527825431.ch2

- 43.Lammel T, Mackevica A, Johansson BR, Sturve J. Endocytosis, intracellular fate, accumulation, and agglomeration of titanium dioxide (TiO2) nanoparticles in the rainbow trout liver cell line RTL-W1. Environ Sci Pollut Res Internat. 2019;26(15):15354–15372. doi: 10.1007/s11356-019-04856-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Al-Ammari A, Zhang L, Yang J, et al. Toxicity assessment of synthesized titanium dioxide nanoparticles in fresh water algae Chlorella pyrenoidosa and a zebrafish liver cell line. Ecotoxicol Environ Saf. 2021;211:111948. doi: 10.1016/j.ecoenv.2021.111948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Jia X, Wang S, Zhou L, Sun L. The potential liver, brain, and embryo toxicity of titanium dioxide nanoparticles on mice. Nanoscale Res Lett. 2017;12(1):478. doi: 10.1186/s11671-017-2242-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Shah SN, Shah Z, Hussain M, Khan M. Hazardous effects of titanium dioxide nanoparticles in ecosystem. Bioinorg Chem Appl. 2017;2017:4101735. doi: 10.1155/2017/4101735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Johari S, Asghari S. Acute toxicity of titanium dioxide nanoparticles in Daphnia magna and Pontogammarus maeoticus. J Adv Environ Health Res. 2015;3(2):111–119. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kumar A, Pandey AK, Singh SS, et al. Cellular uptake and mutagenic potential of metal oxide nanoparticles in bacterial cells. Chemosphere. 2011;83(8):1124–1132. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2011.01.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Eymard-Vernain E, Luche S, Rabilloud T, Lelong C. ZnO and TiO2 nanoparticles alter the ability of Bacillus subtilis to fight against a stress. PLoS ONE. 2020;15(10):e0240510. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0240510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Li H, Wu S, Du C, et al. Preparation, performances, and mechanisms of microbial flocculants for wastewater treatment. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17:1360. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17041360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Simonin M, Richaume A, Guyonnet J, et al. Titanium dioxide nanoparticles strongly impact soil microbial function by affecting archaeal nitrifiers. Sci Rep. 2016;6:33643. doi: 10.1038/srep33643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lin D, Story SD, Walker SL, et al. Role of pH and ionic strength in the aggregation of TiO2 nanoparticles in the presence of extracellular polymeric substances from Bacillus subtilis. Environ Pollut. 2017;228:35–42. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2017.05.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Romanello MB, Fidalgo de Cortalezzi MM. An experimental study on the aggregation of TiO2 nanoparticles under environmentally relevant conditions. Water Res. 2013;47(12):3887–3898. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2012.11.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kao JY, Cheng WT. Study on dispersion of TiO2 nanopowder in aqueous solution via near supercritical fluids. ACS Omega. 2020;5(4):1832–1839. doi: 10.1021/acsomega.9b03101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.French RA, Jacobson AR, Kim B, et al. Influence of ionic strength, pH, and cation valence on aggregation kinetics of titanium dioxide nanoparticles. Environ Sci Technol. 2009;43:1354–1359. doi: 10.1021/es802628n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sohm B, Immel F, Bauda P, Pagnout C. Insight into the primary mode of action of TiO2 nanoparticles on Escherichia coli in the dark. Proteomics. 2015;15(1):98–113. doi: 10.1002/pmic.201400101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Matboo SA, Nazari S, Niapour A, Niri MV, Asgari E, Mokhtari SA. Antibacterial effect of TiO2 modified with poly-amidoamine dendrimer - G3 on S. aureus and E. coli in aqueous solutions. Water Sci Technol. 2022;85:605–616. doi: 10.2166/wst.2022.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Pagnout C, Jomini S, Dadhwal M, et al. Role of electrostatic interactions in the toxicity of titanium dioxide nanoparticles toward Escherichia coli. Coll Surf B Biointerfaces. 2012;92:315–321. doi: 10.1016/j.colsurfb.2011.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Leitão TJ, Cury JA, Tenuta L. Kinetics of calcium binding to dental biofilm bacteria. PLoS ONE. 2018;13(1):e0191284. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0191284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Arvidsson R, Hansen SF, Baun A. Influence of natural organic matter on the aquatic ecotoxicity of engineered nanoparticles: Recommendations for environmental risk assessment. NanoImpact. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.impact.2020.100263. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Murugadoss S, Brassinne F, Sebaihi N, et al. Agglomeration of titanium dioxide nanoparticles increases toxicological responses in vitro and in vivo. Part Fibre Toxicol. 2020;17:10. doi: 10.1186/s12989-020-00341-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Tantra R, Sikora A, Hartmann NB, et al. Comparison of the effects of different protocols on the particle size distribution of TiO2 dispersions. Particuology. 2015;19:35–44. doi: 10.1016/j.partic.2014.03.017. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Abbas Q, Yousaf B, Amina Ali MU, et al. Transformation pathways and fate of engineered NPs (ENPs) in distinct interactive environmental compartments: a review. Environ Int. 2020;138:105646. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2020.105646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Mosquera-Vargas E, Herrera-Molina D, Diosa JE (2021) Structural and optical properties of TiO2 nanoparticles and their photocatalytic behavior under visible light. Ingeniería y Competitividad 23(2). In press 2021. 10.25100/iyc.v23i2.10965

- 65.Chakhtouna H, Benzeid H, Zari N, et al. Recent progress on Ag/TiO2 photocatalysts: photocatalytic and bactericidal behaviors. Environ Sci Pollut Res Int. 2021;28(33):44638–44666. doi: 10.1007/s11356-021-14996-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.El Mragui A, Logvina Y, Pinto da Silva L, et al. Synthesis of Fe- and Co-doped TiO2 with improved photocatalytic activity under visible irradiation toward carbamazepine degradation. Materials. 2019;12(23):3874. doi: 10.3390/ma12233874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Komaraiah D, Radha E, Sivakumar J, et al. Structural, optical properties and photocatalytic activity of Fe3+ doped TiO2 thin films deposited by sol-gel spin coating. Surf Interfaces. 2019;17:100368. doi: 10.1016/j.surfin.2019.100368. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Badhe RA, Ansari A, Garje SS. Study of optical properties of TiO2 nanoparticles and CdS@TiO2 nanocomposites and their use for photocatalytic degradation of rhodamine B under natural light irradiation. Bull Mater Sci. 2021;44:11. doi: 10.1007/s12034-020-02313-1S. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Meng D, Liu X, Xie Y, Du Y, Yang Y, Xiao C. Antibacterial activity of visible light-activated TiO2 thin films with low level of Fe doping. Adv Mater Sci Eng. 2019;1:1–8. doi: 10.1155/2019/5819805. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Romero-Morán A, Zavala-Franco A, Sánchez-Salas JL, Méndez-Rojas MÁ, Molina-Reyes J. Electrostatically charged rutile TiO2 surfaces with enhanced photocatalytic activity for bacteria inactivation. Catal Today. 2022 doi: 10.1016/j.cattod.2022.01.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Bengalli R, Ortelli S, Blosi M, et al. In vitro toxicity of TiO2:SiO2 nanocomposites with different photocatalytic properties. Nanomater. 2019;9(7):1041. doi: 10.3390/nano9071041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Xiong S, George S, Ji Z, et al. Size of TiO2 nanoparticles influences their phototoxicity: an in vitro investigation. Arch Toxicol. 2013;87(1):99–109. doi: 10.1007/s00204-012-0912-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Reghunath S, Pinheiro D, Sunaja DKR. A review of hierarchical nanostructures of TiO2: advances and applications. Appl Surf Sci Adv. 2021;3:100063. doi: 10.1016/j.apsadv.2021.100063. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Tay Q, Liu X, Tang Y, et al. Enhanced photocatalytic hydrogen production with synergistic two-phase anatase/brookite TiO2 nanostructures. J Phys Chem. 2013;117(29):14973–14982. doi: 10.1021/jp4040979. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Lin X, Li J, Ma S, et al. Toxicity of TiO2 Nanoparticles to Escherichia coli: effects of particle size, crystal phase and water chemistry. PLoS ONE. 2014;9(10):e110247. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0110247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Sescu AM, Favier L, Lutic D, et al. TiO2 doped with noble metals as an efficient solution for the photodegradation of hazardous organic water pollutants at ambient conditions. Water. 2021;13(1):19. doi: 10.3390/w13010019. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Scrimieri L, Velardi L, Serra A, et al. (2020) Enhanced adsorption capacity of porous titanium dioxide nanoparticles synthetized in alkaline sol. Appl Phys A. 2020;126:926. doi: 10.1007/s00339-020-04103-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Siripatrawan U, Kaewklin P. Fabrication and characterization of chitosan-titanium dioxide nanocomposite film as ethylene scavenging and antimicrobial active food packaging. Food Hydrocoll. 2018;84:125–134. doi: 10.1016/j.foodhyd.2018.04.049. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Ramirez L, Gentile SR, Zimmermann S, Stoll S. Behavior of TiO2 and CeO2 nanoparticles and polystyrene nanoplastics in bottled mineral, drinking and Lake Geneva waters. Impact of water hardness and natural organic matter on nanoparticle surface properties and aggregation. Water. 2019;11(4):721. doi: 10.3390/w11040721. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Razzaq Z, Khalid A, Ahmad P, et al. Photocatalytic and antibacterial potency of titanium dioxide nanoparticles: a cost-effective and environmentally friendly media for treatment of air and wastewater. Catalysts. 2021;11(6):709. doi: 10.3390/catal11060709. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Niu L, Zhao X, Tang Z, et al. Difference in performance and mechanism for methylene blue when TiO2 nanoparticles are converted to nanotubes. J Clean Prod. 2021;297:126498. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2021.126498. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 82.El Hakim S, Chave T, Nada AA, et al. Tailoring noble metal-free Ti@TiO2 photocatalyst for boosting photothermal hydrogen production. Front Catal. 2021;1:669260. doi: 10.3389/fctls.2021.669260. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Rao TN, Prashanthi Y, Ahmed F, et al. Photocatalytic applications of Fe–Ag Co-doped TiO2 nanoparticles in removal of flumioxazin pesticide residues in water. Front Nanotechnol. 2021;3:652364. doi: 10.3389/fnano.2021.652364. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Bakhshali-Dehkordi R, Ghasemzadeh MA, Safaei-Ghomi J. Green synthesis and immobilization of TiO2 NPs using ILs-based on imidazole and investigation of its catalytic activity for the efficient synthesis of pyrimido[4,5-d]pyrimidines. J Mol Struct. 2020;1206:127698. doi: 10.1016/j.molstruc.2020.127698. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Cavitt TB, Pathak N. Modeling bacterial attachment mechanisms on superhydrophobic and superhydrophilic substrates. Pharmaceuticals. 2021;14:977. doi: 10.3390/ph14100977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Poortinga T, Bos R, Norde W, Busscher HJ. Electric double layer interactions in bacterial adhesion to surfaces. Surf Sci Rep. 2002;47(1):1–32. doi: 10.1016/S0167-5729(02)00032-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Harimawan A, Ting YP. Investigation of extracellular polymeric substances (EPS) properties of P. aeruginosa and B. subtilis and their role in bacterial adhesion. Coll Surf B Biointerfaces. 2016;146:459–467. doi: 10.1016/j.colsurfb.2016.06.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Hou J, Wang L, Wang C, et al. Toxicity and mechanisms of action of titanium dioxide nanoparticles in living organisms. J Environ Sci. 2019;75:40–53. doi: 10.1016/j.jes.2018.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Baek S, Joo SH, Blackwelder P, Toborek M. Effects of coating materials on antibacterial properties of industrial and sunscreen-derived titanium-dioxide nanoparticles on Escherichia coli. Chemosphere. 2018;208:196–206. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2018.05.167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Leung YH, Xu X, Ma AP, et al. Toxicity of ZnO and TiO2 to Escherichia coli cells. Sci Rep. 2016;6:35243. doi: 10.1038/srep35243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Millour M, Doiron K, Lemarchand K, Gagné JP. Does the bacterial media culture chemistry affect the stability of nanoparticles in nanotoxicity assays? J Xenobiot. 2015;5(2):5772. doi: 10.4081/xeno.2015.5772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Nachtigall C, Vogel C, Rohm H, Jaros D. How capsular Exopolysaccharides affect cell surface properties of lactic acid bacteria. Microorganisms. 2020;8(12):1904. doi: 10.3390/microorganisms8121904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Kalia VC, Patel SKS, Kang YC, Lee JK. Quorum sensing inhibitors as antipathogens: biotechnological applications. Biotechnol Adv. 2019;37:68–90. doi: 10.1016/j.biotechadv.2018.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.van Merode A, van der Mei HC, Busscher HJ, Waar K, Krom BP. Enterococcus faecalis strains show culture heterogeneity in cell surface charge. Microbiology (Reading, Engl.) 2006;152:807–814. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.28460-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Simon-Deckers A, Loo S, Mayne-L'hermite M, Herlin-Boime N, Menguy N, Reynaud C, Gouget B, Carrière M. Size-, composition- and shape-dependent toxicological impact of metal oxide nanoparticles and carbon nanotubes toward bacteria. Environ Sci Technol. 2009;43(21):8423–8429. doi: 10.1021/es9016975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Sharma P. Characterization and bacterial toxicity of titanium dioxide NPs. Int J Scientific Res. 2021;10:9–11. doi: 10.36106/ijsr/0132760. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Jiang C, Chen Q. Effect of long-term low concentrations of TiO2 nanoparticles on dewaterability of activated sludge and the relevant mechanism: the role of nanoparticle aging. Environ Sci Pollut Res. 2021 doi: 10.1007/s11356-021-16451-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Kumar N, Mittal A, Yadav M, et al. Photocatalytic TiO2/CdS/ZnS nanocomposite induces Bacillus subtilis cell death by disrupting its metabolism and membrane integrity. Indian J Microbiol. 2021;61(4):487–496. doi: 10.1007/s12088-021-00973-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Wang L, Hu C, Shao L. The antimicrobial activity of nanoparticles: present situation and prospects for the future. Int J Nanomedicine. 2017;12:1227–1249. doi: 10.2147/IJN.S121956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Calero JL, Berríos ZO, Suarez OM (2019) Biodegradable chitosan matrix composite reinforced with titanium dioxide for biocidal applications. https://www.intechopen.com/chapters/65677

- 101.Dicastillo CLd, Correa MG, Martínez FB, Streitt C & Galotto MJ (2020). Antimicrobial effect of titanium dioxide nanoparticles. In: Mares M, Lim SHE, Lai K & Cristina R (Eds.), Antimicrobial resistance - a one health perspective. IntechOpen. 10.5772/intechopen.90891

- 102.Gea M, Bonetta S, Iannarelli L, et al. Shape-engineered titanium dioxide nanoparticles (TiO2-Nps): cytotoxicity and genotoxicity in bronchial epithelial cells. Food Chem Toxicol. 2019;127:89–100. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2019.02.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Čapek J, Roušar T. Detection of oxidative stress induced by nanomaterials in cells-the roles of reactive oxygen species and glutathione. Molecules. 2021;26(16):4710. doi: 10.3390/molecules26164710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Kalia VC, Shouche Y, Purohit HJ, Rahi P (2017) Mining of microbial wealth and metagenomics. Springer, Berlin, Germany. http://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-10-5708-3

- 105.Simonin M, Cantarel AA, Crouzet A, Gervaix J, Martins JM, Richaume A. Negative effects of copper oxide nanoparticles on carbon and nitrogen cycle microbial activities in contrasting agricultural soils and in presence of plants. Front Microbiol. 2018;9:3102. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2018.03102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Zhang L, Wu L, Si Y, Shu K. Size-dependent cytotoxicity of silver nanoparticles to Azotobacter vinelandii: growth inhibition, cell injury, oxidative stress and internalization. PLoS ONE. 2018;13:e0209020. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0209020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Xiao X, He EJ, Lu XR, et al. Evaluation of antibacterial activities of silver nanoparticles on culturability and cell viability of Escherichia coli. Sci Total Environ. 2021;794:148765. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.148765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Chen Z, Yang P, Yuan Z, Guo J. Aerobic condition enhances bacteriostatic effects of silver nanoparticles in aquatic environment: an antimicrobial study on Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Sci Rep. 2017;7(1):7398. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-07989-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Pathak M, Sharma M, Ojha H, Kumari R, Sharma N, Roy B, Jain G. Green synthesis, characterization and antibacterial activity of silver nanoparticles. Green Chem Technol Lett. 2016;2:103–109. doi: 10.18510/gctl.2016.2210. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Baek YW, An YJ. Microbial toxicity of metal oxide NPs (CuO, NiO, ZnO, and Sb2O3) to Escherichia coli, Bacillus subtilis, and Streptococcus aureus. Sci Total Environ. 2011;409:1603–1608. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2011.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Doskocz N, Affek K, Załęska-Radziwiłł M (2017) Effects of aluminium oxide NPs on bacterial growth. E3S Web Conf 17: 00019. 10.1051/e3sconf/20171700019

- 112.Zhang C, Lin X, Miao Y. The study of the biotoxicity effect of alumina nanoparticle on soil microbes. IOP Conf Ser Earth Environ Sci. 2021;772:012094. doi: 10.1088/1755-1315/772/1/012094. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 113.George JM, Magogotya M, Vetten MA, et al. From the Cover: an investigation of the genotoxicity and interference of gold nanoparticles in commonly used in vitro mutagenicity and genotoxicity assays. Toxicol Sci. 2017;156(1):149–166. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfw247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Patel SKS, Choi SH, Kang YC, et al. Eco-friendly composite of Fe3O4-reduced graphene oxide particles for efficient enzyme immobilization. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2017;9:2213–2222. doi: 10.1021/acsami.6b05165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Patel SKS, Choi SH, Kang YC, et al. Large-scale aerosol-assisted synthesis of biofriendly Fe2O3 yolk-shell particles: a promising support for enzyme immobilization. Nanoscale. 2016;8:6728–6738. doi: 10.1039/C6NR00346J. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Otari SV, Patel SKS, Jeong JH, et al. A green chemistry approach for synthesizing thermostable antimicrobial peptide-coated gold nanoparticles immobilized in an alginate biohydrogel. RSC Adv. 2016;6:86808–86816. doi: 10.1039/c6ra1488k. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Otari SV, Pawar SH, Patel SKS, et al. Canna edulis leaf extract-mediated preparation of stabilized silver nanoparticles: characterization, antimicrobial activity, and toxicity studies. J Microbiol Biotechnol. 2017;27:731–738. doi: 10.4014/jmb.1610.10019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Otari SV, Patel SKS, Kalia VC, et al. Antimicrobial activity of biosynthesized silver nanoparticles decorated silica nanoparticles. Indian J Microbiol. 2019;59:379–382. doi: 10.1007/s12088-019-00812-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Patel SKS, Anwar MZ, Kumar A, et al. Fe2O3 yolk-shell particles-based laccase biosensor for efficient detection of 2,6-dimethoxyphenol. Biochem Eng J. 2018;132:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.bej.2017.12.013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]