Abstract

For a Closed Loop Supply Chain (CLSC), disaster is a risk source of unknown-unknowns, which may result in production disruptions with significant consequences on -but not limited to-profitability. For this reason, we provide a System Dynamics (SD)-based analysis for disaster events on the operation of CLSCs in order to study the system response (production/collection/disassembly/remanufacturing/recycling rates, inventories, cost, profit). This response is examined through the dynamics at a manufacturer, parts producer, collector, and disassembly center level, by providing control mechanisms for resilient CLSCs under disaster effects. In this dynamic analysis, COVID-19 is treated as a disaster event. Five different business scenario settings are presented for the manufacturer, which are considered as alternative mitigation policies in responding to product demand. The extensive simulation results provide insights for policy-makers, which depend on the reduction in manufacturer's production, reduction in product demand and duration of recovery period which are considered as causal effects due to the COVID-19 outbreak. For all combinations, holding base stocks during the pre-disaster period is proposed as the best mitigation policy in terms of manufacturer's inventory. In terms of economic impact, holding base stocks or coordination with third party are revealed as the best choice depending on the combination, while remote inventory policy adoption as the worst choice.

Keywords: System dynamics, Disaster management, Supply chain management, Closed-loop supply chains

Abbreviations

- BM

Basic Mechanism

- BS

Business Scenario

- CI

Collection Inventory

- CLSC

Closed Loop Supply Chain

- CM

Control Mechanism

- MI

Manufacturer's Inventory

- PPI

Parts Producer's Inventory

- RI

Retailer's Inventory

- RMSI

Raw Materials Supplier's Inventory

- RP

Remanufacturable Parts

- RPI

Remanufacturable Part Inventory

- SC

Supply Chain

- SD

System Dynamics

- UPI

Used-product inventory

- WI

Wholesaler's Inventory

1. Introduction

In tackling uncertainties and disruptions in supply chain (SC) dynamics, it is important to know if and to what extent the study is dealing with known effects, unknown effects or a combination of the two. Experience demonstrates that policies crafted to operate within a certain range of conditions are often faced with unexpected challenges outside that range (Maureen et al., 2020). Makridakis et al. (2010) propose to distinguish between known-known, known-unknown, and unknown-unknown risks when handling uncertainty in a given situation: There is no uncertainty associated with known-knowns, as we know exactly what will happen, in contrast with known-unknowns where we know that there is a risk. In unknown-unknowns, however, we do not even know if there is a risk. In SC management, Simchi-Levi defines unknown-unknown risks as events where it is difficult to quantify the likelihood of occurrence and shows some mitigation strategies, such as creating capacity and sourcing redundancy, increasing velocity in supplying and responding, and adding flexibility to the SC (Simchi-Levi, 2010).

For a SC, disaster is a risk source of unknown-unknowns (Simchi-Levi, 2010) as is the case with the COVID-19 pandemic (Pawson et al., 2020). It may result in production disruptions with significant consequences on profitability. There are a lot of such real-world examples. Toyota production line had to be shut down for two weeks when its sole supplier of brake-fluid proportioning valves was hit by fire in 1997 (Reitman, 1997). The 1999 Taiwan earthquake caused a two-week global semiconductor shortage, as Taiwan was the third largest supplier of computer accessories in the world at that time (Li and Chen, 2010). Other disruptions were caused by epidemics, like the outbreak of mad cow disease that caused a shortage of leather goods in Europe in 2001 and the outbreak of SARS that impacted information technology SCs in 2003 (Natarajarathinam et al., 2009). The policy that should be adopted in facing production disruption owing to disasters is a crucial issue. In 2000, for example, the Phillips Electronics semiconductor plant in Albuquerque, New Mexico, was the sole microchips supplier of Ericsson. This plant was destroyed by fire due to the 2000 lightning incident resulting in about $400 million loss for Ericsson (Eglin, 2003). On the contrary, Nokia, a competitor of Ericsson and a major customer of the same Philips Electronics plant, sensed this disruption following a multiple-supplier strategy and responsiveness, and took immediate action by switching its chip orders to other Philips plants, as well as to other Japanese and American suppliers. This quick response resulted in increasing Nokia's handset market share from 27% to 30% (Latour, 2001). Considering the estimated numbers of 2018, 315 disasters around the world have led to 11,804 deaths, 68.5 million people affected and $131.7 billion economic damage (CRED, 2019). Zhang et al. (2020) analyzed the economic loss of four selected ports in China due to typhoon-induced wind disasters from 2007 to 2017. The overall economic loss calculated as the sum of reputational loss, loss to the shippers, loss to the carrier and loss to the ports was approximately equal to $20 billion.

Emergency response operations are crucial in order to reduce the impact of a disaster phenomenon on the SCs. Coordinated operations among SC actors and optimized emergency SC operations are critical to provide a speedy response to the presence of demand uncertainty, which remains one of the main challenges in disasters (Song et al., 2018). As Ivanov and Dolgui (2020a) mention, the questions that arose from the drastic increase or decrease of demand due to the COVID-19 outbreak cannot be resolved within a narrow SC perspective, but rather require an analysis at a larger scale by going beyond the existing state-of-the-art in SC resilience.

Systems thinking, in particular System Dynamics (SD), has been identified as a promising holistic approach to disaster management by considering the systemic environments within a larger system (Tang and Nurmaya Musa, 2011; Galindo and Batta, 2013; Borja et al., 2019). This approach can be employed for modeling and testing SC risk mitigation policies and recovery plans to gain insights into situations of dynamic complexity and policy resistance (Ivanov and Sokolov, 2020). However, SD is underutilized when focusing on the explanation of closed-loop supply chain (CLSC) dynamics. In addition, its contribution is minimal especially when dealing with the dynamics of integrated CLSC networks (Ivanov and Dolgui, 2020b). Gu and Gao (2012) and Borja et al. (2019) introduce integrated CLSC systems with remanufacturing and recycling operations for long-term dynamic analysis and decision making, but in the absence of disaster effects whilst also ignoring any operational disruption settings.

By considering that CLSCs have been recently affected by pandemics at an extraordinary extent, our study takes the research conducted by Gu and Gao (2012) and Borja et al. (2019) further by incorporating the modeling of potential large-scale disruptions owing to disasters, along with their direct and side effects on CLSC operations, into both forward and reverse channels. Our purpose is to provide an SD-based analysis for the COVID-19 effects on the operation of integrated CLSCs. Moreover, the analysis incorporates adaptive control mechanisms and studies risk mitigation policies under alternative business scenario settings.

The proposed SD model deals with a single manufacturer/multi-echelon CLSC with remanufacturing and recycling activities. The actors involved in the forward channel are the raw materials supplier, parts producer, manufacturer, wholesaler and retailer, while in the reverse channel it is the collector and the disassembly center. The reverse channel activities include the operations of disassembly, remanufacturing and recycling of used-product returns. Remanufacturing operations produce “as-good-as-new” parts for the manufacturer, while recycling operations supplies the parts producer with recycled raw materials. We formulate a dynamic hypothesis about the effects of the COVID-19 phenomenon on the manufacturer's production together with side effect impacts on the operations of other involved actors. We study the response of CLSC systems (transient flows, inventories, cost, profit) to different levels of recovery time. This response is examined through the dynamics at the manufacturer, parts producer, collector and disassembly center level, by introducing control mechanisms for resilient CLSCs that will be able to control the rate of inflows and outflows for each echelon at both channels under disaster effects. This dynamic analysis considers five business scenario settings for the manufacturer as alternative mitigation policies in responding to the wholesaler's orders. The first scenario refers to an inventory management policy which remains constant throughout the planning-horizon, while the second one assumes that the manufacturer adopts a speedy stock replenishment policy and operates with an additional shift in the post-disaster period. The third scenario adopts a remote inventory policy. The fourth and fifth scenario adopt a coordinated planning approach. In particular, in the fourth scenario, the manufacturer satisfies the wholesaler's demand by contracting with a third-party producer who is not affected by the disaster event, while, in the fifth scenario, the manufacturer satisfies the wholesaler's demand by contracting with a third-party producer who did not operate during the disaster period but has an increased percentage of supply in the post-disaster period.

The first scenario is indicated by Ivanov, 2020a, Ivanov, 2020b, Rozhkov et al. (2022) and Shahed et al. (2020), who have underlined the necessity for different inventory level policies in order to mitigate the risk owing to the COVID-19 pandemic, as well as to maximize the total profit of SCs.

The second and third scenario are suggested by Chopra and Sodhi (2004), who mention that leading companies have stored either excess production capacity (second scenario) or excess inventory (third scenario) when dealing with supply chain risks.

The fourth and fifth scenario are based on coordinated approaches suggested by Raj et al. (2022) and Scheller et al. (2021) at the different levels of the SC, with the aim of addressing the risks that emerge in SCs.

All of the above-mentioned scenarios are tested under alternative settings regarding the reduction of wholesaler demand (Ivanov, 2020a, Ivanov, 2020b), the reduction in the manufacturer's production and the duration of the recovery period (Ivanov 2020; Ivanov and Dolgui et al., 2020). These settings are considered as causal effects due to the COVID-19 outbreak.

The rest of the paper is organized as follows. Section 2 provides a literature review of the fundamentals of disaster management so to identify the research gap. Section 3 presents a generic description of the CLSC under study and the formulation of direct and side effects of a disaster event hitting the manufacturer. The mathematical representation of the SD model and of control mechanisms is given in Section 4. Section 5 provides the settings of a numerical experimentation for the case of COVID-19, followed by a concluding discussion based on results gained by extensive simulation experimentation. The final section contains a brief summary, the limitations of this study and directions for future work.

2. Literature review

The research agenda in disaster management has received increased attention during the last 15 years. It is remarkable that, although the topic is suitable for OR/MS research (Rameshwar et al., 2019), the scientific community has not yet produced enough articles dealing with operations management issues in large-scale disasters; an interesting review of this field is provided in Altay and Green (2006), Galindo and Batta (2013) and Farahani et al. (2020). Nevertheless, the contributions are almost minimal if the research questions are directed to unknown-unknown effects on CLSC operations. This is probably caused by the fact that the detailed impact of a disaster on the operations of CLSCs is rather unknown (Ivanov, 2020a, Ivanov, 2020b; Ivanov and Dolgui, 2020b; Dolgui et al., 2020; Holguín-Veras et al., 2012). In addition, as Borja et al. (2019) notice, the literature on the dynamic behavior of CLSCs is still very limited. However, possible scenarios can be examined by means of models, which describe the interactions between different parts of the system under study. In the case of unknown-unknown effects, these interactions are rather non-linear, while the efficiency of the models is directly dependent on their ability to be based on a feedback structure by employing adaptive control mechanisms and considering time delays (Surana et al., 2005). This combination calls for a dynamic modeling approach. Complex adaptive systems theory (Surana et al., 2005; Hwarng and Yuan, 2014; Li et al., 2010), chaos theory (Hwarng and Xie, 2008; Wu and Zhang, 2007), catastrophe theory (Helbing et al., 2006) and catastrophe-risk approaches (Peterson, 2002), disaster preparedness (John Kwesi-Buor et al., 2019), along with non-linear dynamic approaches (Mosekilde and Laugesen, 2008; Wu and Zhang, 2007; Chang et al., 2007), provide such methods for the dynamic analysis and optimization of CLSCs under disaster effects. However, models based on these methods usually lead to complex approaches and to restrictions on the number of state variables and on cost structure that they can handle.

System-oriented and holistic approaches have been identified as important in modeling the complex, deeply uncertain and dynamic elements of disaster management (Tang and Nurmaya Musa, 2011; Altay and Green III, 2006; Galindo and Batta, 2013; Borja et al., 2019). In particular, the SD methodology introduced by Forrester (1961), provides a simpler and more flexible modeling and simulation framework for decision-making in dynamic and complex industrial management problems (Größler et al., 2008; John Kwesi-Buor et al., 2019). It is an appropriate approach to study disaster operations problems in a CLSC context, mainly due to the following two reasons: (i) it has the ability to integrate soft factors into an operations analysis; (ii) it can deal with increased complexity caused by causal influences among different involved actors, non-linear behavior and time delays (Sterman, 2000; Größler et al., 2008; Aydin, 2020). Additionally, benefits of using SD models include: (i) allowing for the exploration and evaluation of alternative scenarios, making their impact on the performance of the system testable and, (ii) being highly appreciated and well understood by managers, because they enrich brainstorming and have a lower reliance on hard data than other methods (Sterman, 2000). This methodology provides an understanding of changes occurring within a system by focusing on the interaction between physical flows, information flows, delays and policies that create the dynamics of the variables of interest. Thereafter, the SD methodology searches for policies to improve system performance by considering the causal influences of relative decisions on the operational dynamics (Georgiadis and Michaloudis, 2012; Yang et al., 2020).

Although SD has been identified as promising for modeling complex and adaptive to nonlinear evolutionary change problems (Tang and Nurmaya Musa, 2011), the SD contributions in SC management are mainly focused on operational and transportation disruptions and on risk management issues: Wilson (2007) investigates the effect of transportation disruptions for the case of a five-echelon supply chain; Chen et al. (2011) examine the effect of disruptions considering pipeline inventory control and vendor-managed inventory control; Li et al. (2016) apply two mitigation policies (increase of transportation equipment capacity and increase of the amount for transportation equipment) in order to deal with risk management issues in chemical SCs; Lawrence et al. (2019) present a conceptual approach to improve hurricane disaster logistics, by combining holistic thinking with simulation and information technologies; Zhang et al. (2021) propose mitigation organizational strategies to cope with different node interruptions in order to improve the overall efficiency and operational capabilities in SCs; Bashiri et al. (2021) study the sustainability risks in the Indonesia–UK coffee SC by combining SD with multiple criteria decision-making techniques.

The contributions are limited when focusing on integrating aspects of SC and aspects of reverse logistics using SD (Ivanov and Dolgui, 2020b). Indeed, the formulation of dynamic strategic capacity planning policies (Georgiadis et al., 2006; Georgiadis and Athanasiou, 2013), the examination of the bullwhip effect (Tombido et al., 2020), the impact of environmental legislation on long-term dynamic behavior of closed-loop remanufacturing networks (Yang J. et al., 2020), and the ecological and economic dimensions of sustainability in closed-loop recycling networks (Manoranjan and Giri, 2020) are some of the few fields that have received special attention. These models include either remanufacturing or recycling options of product reuse, while the integration of both remanufacturing and recycling into a closed-loop model for long-term evolutionary analysis and decision making is introduced by Gu and Gao (2012). However, these studies focus on CLSC dynamics and ignore any disaster effects. This results in little research, which is limited in examining disaster operations issues by employing the SD approach (Altay and Green, 2006; Galindo and Batta, 2013; Rebs et al., 2019; Farahani et al., 2020).

3. System and problem description

3.1. System description and main assumptions

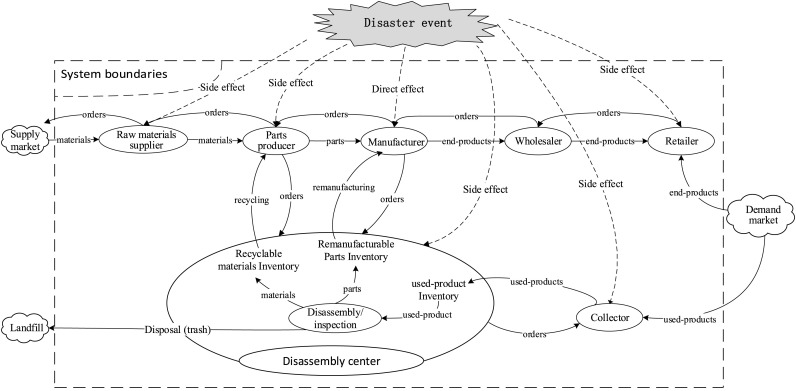

Fig. 1 exhibits a very generic description of the CLSC under study. In particular we deal with a single manufacturer/multi-echelon CLSC with remanufacturing and recycling activities. The forward supply chain comprises five echelonsa Raw materials supplier, Parts producer, Manufacturer, Wholesaler, and Retailer. The Raw materials supplier obtains materials from the Supply market. The Parts producer produces parts by using two inflows of materials; original raw materials by Raw materials supplier and materials recovered by recycling. Priority is given to supply with recycled materials. The Manufacturer produces end-products by assembling n = 1, 2, …,N parts. The Manufacturer obtains these parts by using two inflows; original parts supplied by Parts producer and parts obtained from a remanufacturing recovery process which has priority over using original parts. The Wholesaler purchases end-products from the Manufacturer, while the Retailer from the Wholesaler in order to satisfy demand (Demand Market). A basic assumption made about the forward supply line is that unsatisfied orders placed by Retailer and Wholesaler as well as unsatisfied Demand market are backlogged and are satisfied in a subsequent time period.

Fig. 1.

Integrated Closed Loop Supply Chain and disaster effects.

The reverse channel includes the activities of collection (provided by Collector), disassembly (provided by Disassembly center), remanufacturing, recycling, and Disposal. In particular, used-products are collected by the Collector for reuse and thereafter are transferred and sold to the Disassembly center. The re-manufacturability condition (quality) of parts obtained through the disassembly procedure is inspected so as to sort them into the remanufacturable stream. The condition of parts rejected for remanufacturing is inspected for recycling. The parts accepted for recycling are sorted as recyclable materials, while those rejected are controllably disposed as trash (Disposal). The output of remanufacturing is “as-good-as-new parts” for the Manufacturer while that of the recycling process is substitutes of virgin raw materials for the Parts producer. With regard to buy/supply relationships among involved actors, we assume a single-supplier strategy in both channels, which means that a single Parts producer is the sole supplier for the Manufacturer, the latter is the sole supplier for a single Wholesaler etc.

3.2. Problem description

The focal point of this paper is the examination of the dynamic behavior of a CLSC system under disaster effects hitting the manufacturer, as well as the investigation of the efficiency of adopted alternative mitigation policies. This examination takes also into consideration, the side effects of each mitigation policy on the operations of other actors.

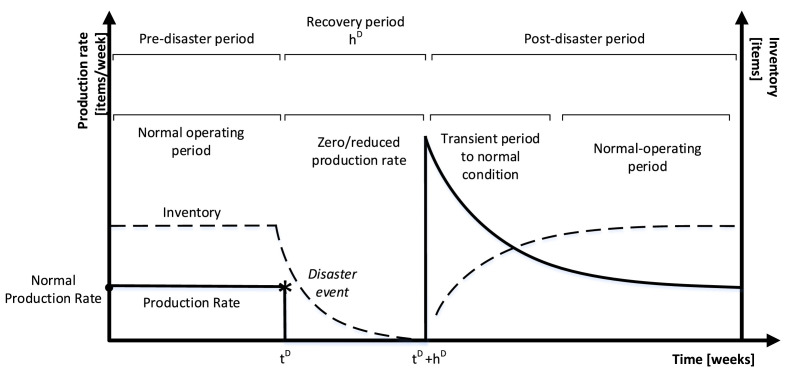

The modeling of the disaster effect on the production rate of the manufacturer is shown in Fig. 2 , which illustrates a likelihood pattern for the production rate at pre-disaster, disaster recovery and post-disaster time periods; t D is the unknown time of occurrence of a disaster event, while h D is the unknown duration of recovery period. This approach is based on the disaster resilience triangle concept originally introduced by Bruneau et al. (2003) and thereafter extended by Zobel and Khansa (2014). As also shown in Fig. 2, we assume that during the recovery period (h D) shipments from the manufacturer to the wholesaler are possible if there is inventory. During the recovery period two options are considered regarding the disruptions at the manufacturer level due to the disaster effect: zero production rate; reduced production rate. These options in combination with the adopted single-supplier strategy, causes the following side effects on the operations of other actors involved in both forward and reverse channel (see Fig. 1): (i) zero or reduced purchase rate for original parts between the Parts producer and the Manufacturer; (ii) zero or reduced remanufacturing and recycling rates at the Disassembly center; and (iii) decreased purchase rate for used-products between the Disassembly center and the Collector due to the shrinkage of remanufacturing and recycling activities.

Fig. 2.

Likelihood pattern for production rate and end-products inventory under disaster effect at manufacturer level.

To deal with the dynamic response of the CLSC system to the above-mentioned disaster effects, we develop a SD model which provides a stock and flow structure of the CLSC under study. The modeling approach is based on a disaster-free SD model of a similar system provided by Gu and Gao (2012), which incorporates adaptive control mechanisms for each echelon. These mechanisms control the inventory level by regulating the related inflow(s) for the actual state to be aligned with its desired state. We extend this SD model by embedding additional dynamic adaptive control mechanisms for four echelons (namely Manufacturer, Parts producer, Disassembly center, and Collector) as resilient mechanisms for policy design under disaster effects. The rest of the echelons (Raw materials supplier, Wholesaler, Retailer) are controlled by adopting the mechanisms introduced by Gu and Gao (2012). For compatibility reasons, we follow the same notation given in Gu and Gao (2012). From now on, the control mechanisms provided by Gu and Gao (2012) are denoted as BMs (Basic Mechanisms) throughout this text, while the mechanisms provided by the present study are denoted as CMs (Control Mechanisms), for a clear distinction between these two contributions.

The CMs provide an adaptive response to sudden changes in the system's state due to the effects of a disaster event by exhibiting a goal-seeking behavior, which aims to return the system's state to an equilibrium. We introduce five CMs (CM1-CM5) for the examination of the system's response, which are related to the manufacturer's operation. Each mechanism corresponds to a different business scenario (BS1-BS5) which expresses an alternative mitigation policy adopted by the manufacturer in dealing with disaster effects. In the first scenario (BS1) (Ivanov, 2020a, Ivanov, 2020b; Rozhkov et al., 2022; Shahed et al., 2020), the system's response is examined by developing and holding different base stocks of serviceable inventory as desired states during the pre-disaster period. These stock levels are endogenously defined by the dynamics of wholesaler orders to satisfy demand throughout a whole long-term planning-horizon (active CM1). The second scenario (BS2) (Chopra and Sodhi, 2004) involves the addition of a second shift by the manufacturer when entering the post-disaster period but only for a time period h rec; thereafter the manufacturer returns to one shift operation (active CM2). In scenario BS3 (Chopra and Sodhi, 2004) (active CM3), the manufacturer adopts a remote inventory policy in supplying the wholesaler during the recovery period; the remote inventory is built during the pre-disaster period. In scenario BS4 (Raj et al., 2022; Scheller et al., 2021) (active CM4) a contracting scheme between the manufacturer and a third-party manufacturer is examined under different settings regarding the percentage of wholesaler orders agreed to be satisfied; the third-party manufacturer satisfies a specific percentage of orders (denoted as low) during the pre-disaster and post-disaster periods, but this percentage shifts to a high value during the recovery period (we assume that the third-party manufacturer continues to operate during the crisis). Finally, scenario BS5 (Raj et al., 2022; Scheller et al., 2021) (active CM5) is a variation of BS4 with the only difference being that during the crisis the third-party manufacturer does not operate. In this scenario, the contracted manufacturer is responsible to satisfy a specific percentage of orders (denoted as low) during the pre-disaster period. Τhis percentage shifts to zero during the recovery period. During the post-disaster period, it shifts to a high value for a time period h rec, but thereafter shifts again to its low value.

The remaining three CMs relate to the operations of the Parts producer (CM6), the Disassembly center (CM7) and the Collector (CM8) respectively. These CMs are activated within the recovery period and practically build temporary inventories which are used to manage supply in the post-disaster period. Table 1 provides an overview of dynamic study options provided by the SD model. In Table 1, BBS (basic scenario) refers to CLSCs ignoring disaster events or not affecting by a disaster event when it occurs (absence of all CMs (CM1 – CM8) but active BMs for all echelons).

Table 1.

Overview of dynamic study options.

| Mode of the SD model | Scenario | Control mechanisms | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Disaster-free model [hD = 0] | BBS (Basic) | CM1, CM2, CM3, CM4, CM5, CM6,CM7, CM8 non-active BMs active for all actors | |||

| Disaster active model [tD, hD≠0] | Alternative Scenarios | Manufacturer | Parts producer | Disassembly center | Collector |

| BS1 | active CM1 | active CM6 | active CM7 | active CM8 | |

| BS2 | active CM2 | ||||

| BS3 | active CM3 | ||||

| BS4 | active CM4 | ||||

| BS5 | active CM5 | ||||

4. The SD model

Stocks and flows, along with feedback loops, are the two central concepts of the SD theory. Stocks are the accumulations (e.g., inventories) of the inflows (e.g., production rate) and the outflows (e.g. shipments) within the chain. SD uses a particular diagramming notation for stocks and flows. Stocks are represented by rectangles; inflows are represented by pipes pointing into (adding to) the stock and outflows are represented by pipes pointing out of (subtracting from) the stock. Stocks are defined by the stock equations as the time integrals of the net flows. Flows are defined by the rate equations as the time functions of stocks and system parameters. In SD models, the stock and flow perspective represent time as unfolding continuously; events can happen at any time, change can occur continuously. The structure of a system in the SD methodology is captured by linking the stock and flow structure with feedback mechanisms and is represented by a stock-flow diagram, which is the graphical representation of the mathematical model [33]. The arrows (causal links) inside a stock-flow diagram represent the relations among variables. The direction of the causal links displays the direction of the effect. Signs ‘‘+’’ or ‘‘-’’ at the upper end of these links exhibit the sign of the effect. When the sign is ‘‘+’‘, the variables change in the same direction; otherwise, they change in the opposite one. The stock-flow diagram is translated into a system of differential equations, which is then solved via simulation, supported nowadays by high graphical simulation programs such as PowerSim®, Vensim®, i-think®, Stella®.

A presentation of the full stock-flow diagram of the SD model (and the related equations in a simulation software format) is beyond the scope of this paper, as it contains more than 360 elements (stocks, flows, auxiliaries, and constants) and because the analysis may differ from one CLSC to another. Alternatively, the objective is to facilitate the reproducibility of the SD approach in different real-world networks by providing a high-level overview of a simulated CLSC. Hence, this section provides the analytical mathematical equations by keeping the analysis as generic as possible.

4.1. Generic stock and flow structure

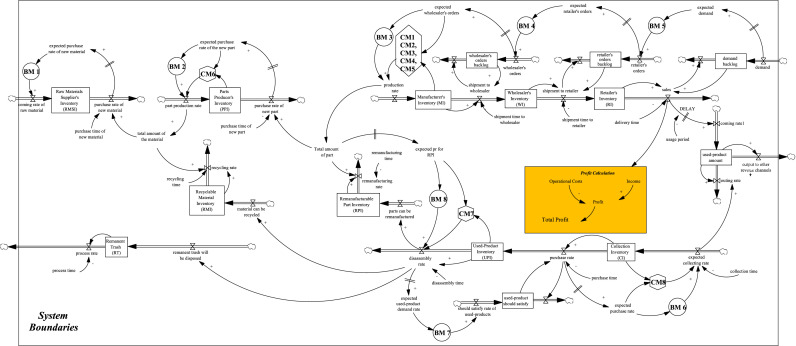

The generic stock-flow diagram is shown in Fig. 3 . The forward supply chain begins from the upper left corner. Raw Materials Supplier's Inventory (RMSI) is increased by the coming rate of new material and is decreased by the purchase rate of new material that is the flow of virgin (new) materials to the parts producer. The demand of the parts producer for materials (total amount of the material) is satisfied with priority over recycled materials defining recycling rate, while the unsatisfied part of demand is fulfilled by the raw materials supplier (purchase rate of new material). Parts Producer's Inventory (PPI) is increased by part production rate and is depleted by purchase rate of new part. The manufacturer's demand for parts (Total amount of the part) is satisfied with priority over remanufactured parts, thus defining the remanufacturing rate. The unsatisfied part of demand is fulfilled by supplies from the parts producer (purchase rate of new part). The production rate increases the Manufacturer's Inventory (MI) in end-products, which is subsequently depleted by shipment to wholesaler in order to satisfy as many of the wholesaler's orders as possible. Production rate is subject to the availability of inventory in parts; either recycled or new. The shipments to the wholesaler take shipment time (shipment time to wholesaler) and deplete the unfulfilled wholesaler's orders (wholesaler's orders backlog). The shipment to the wholesaler increases the Wholesaler's Inventory (WI). The Wholesaler's Inventory is depleted by shipment to retailer, which also takes shipment time (shipment time to retailer). The shipment to retailer depletes the retailer's unfulfilled orders (retailer's orders backlog) and increases the Retailer's Inventory (RI). The latter is decreased by sales which take delivery time to satisfy demand for end-products (demand). All unsatisfied market demand is backlogged and satisfied in a subsequent time period (demand backlog). The same stands for orders placed by the retailer and directed to the wholesaler (retailer's orders backlog), as well as for orders placed by the wholesaler and directed to the manufacturer (wholesaler's orders backlog). Following a time delay (the usage period of a product), sales turn into used-products (coming rate 1).

Fig. 3.

Stock and flow diagram of the CLSC under study.

The reverse channel starts with the collection activities. The stock of used-products at the collector (Collection Inventory (CI)) is increased by the expected collecting rate. The values of this rate are practically the forecasted values of the disassembly center's demand for used-products (further details on this are provided in subsection 4.3.2). The Collection Inventory is depleted by supplies to the disassembly center (purchase rate), which also deplete the unsatisfied demand of the disassembly center (used-product should satisfy); the demand of the disassembly center for used-products is expressed by should satisfy rate of used-product, while the unsatisfied demand is backlogged and satisfied in a subsequent time period. The purchase rate increases the Used-product inventory (UPI) at the disassembly center, which is depleted by the disassembly rate UPI. The parts obtained through the disassembly operation (disassembly rate) are sorted into three streams. In particular, the output of the disassembly sorts the used-products (after inspection) with priority into remanufacturable parts. These parts (parts that can be remanufactured) increase the level of Parts to remanufacture. Parts rejected for remanufacturing are sorted as recyclable materials (material can be recycled), which increase the level of Recyclable Material Inventory (RMI). Parts rejected for recycling are disposed as trash (remanent trash will be disposed). Finally, the remanufacturing rate delivers remanufactured parts to the manufacturer while the recycling rate delivers recycled materials to the parts producer.

All stocks appearing in the forward and reverse channels of the generic stock and flow structure shown in Fig. 3 are controlled by means of two sets of control mechanisms. The first set includes BMs (indicated in Fig. 3 as BM1 – BM8). The second set refers to mechanisms which are introduced in Section 3.2 (see Table 1); they are indicated in Fig. 3 as CM1 – CM8. The mechanisms of this second set control the stocks at the Manufacturer, the Parts producer, the Disassembly center, and the Collector, by regulating the related flows in order to respond to the direct and side effects of a disaster event. The structure of these CMs is based on the well-established stock management structure suggested by Sterman (1989).

In the following subsections, the generic structure given in Fig. 3 is further extended by analyzing the stock and flow as well as the feedback structure of each CM introduced in Table 1.

4.2. Control mechanisms and forward supply chain equations

4.2.1. Manufacturer: CM1 – CM5

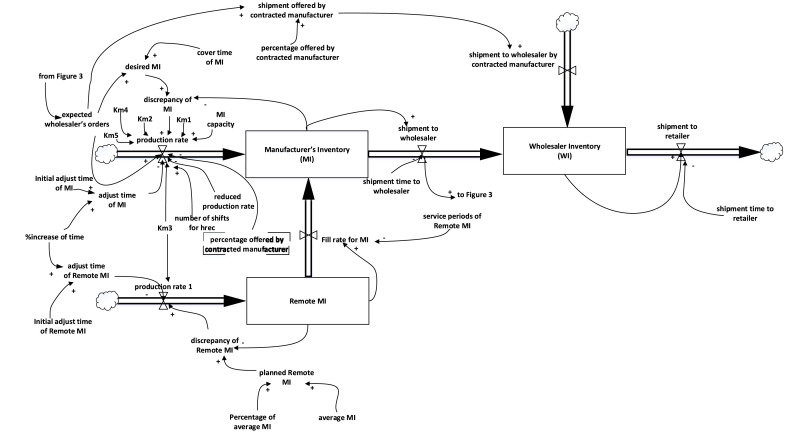

Fig. 4 represents the stock and flow structure of CM1 – CM5. Mechanisms CM1-CM3 control the serviceable inventory at manufacturer level (Manufacturer's Inventory (MI)), while CM4 and CM5 control the serviceable inventories at both manufacturer and wholesaler levels (Wholesaler Inventory (WI)). CM1 and CM2 reflect scenarios BS1 and BS2 respectively, by holding base stocks during the pre-disaster period. In scenario BS1 the manufacturer adopts one shift operation, while in BS2 it adopts two shift operation at the beginning of the post-disaster period for a period h rec. During period h rec, the manufacturer utilizes its capacity (MI capacity) to the maximum in order to satisfy the unsatisfied orders of the wholesaler created during period h D due to reduced or zero production. The stock and flow structure of CM3 is based on a remote inventory policy adopted by the manufacturer (Remote MI) in supplying the wholesaler during the recovery period (scenario BS3). CM4 reflects scenario BS4 where, the manufacturer enters into a contract with a third-party manufacturer who will fulfill a percentage (percentage offered by contracted manufacturer) of expected wholesaler's orders placed by the wholesaler. During normal operating conditions (pre-disaster and post-disaster periods), the third-party manufacturer is responsible for satisfying a low percentage of orders. On the contrary, the contracted manufacturer becomes the sole supplier of the wholesaler for the whole recovery period, being responsible for satisfying a high percentage of orders. Finally, CM5 reflects scenario BS5 which is a variation of BS4; during the recovery period the third-party manufacturer stops supplying the wholesaler, but at the beginning of the post-disaster period and for a time period h rec , it is responsible for satisfying a high percentage of orders. In both scenarios BS4 and BS5, Wholesaler Inventory is increased by shipment to wholesaler (i.e. shipments from manufacturer) and shipment to wholesaler by contracted manufacturer.

Fig. 4.

Stock and flow structure of CM1-CM5.

Parameters K mi (i = 1, .5) shown in Fig. 4 take dual values (0/1), activating (K mi = 1) or deactivating (K mi = 0) the corresponding CMi.. The sets of control parameters that fully describe CM1-CM5 are the following:

CM11 : [K m1, cover time of MI, initial adjust time of MI, %increase of time].

CM2: [K m2, cover time of MI, initial adjust time of MI, %increase of time, h rec].

CM3: [K m3 , cover time of MI, initial adjust time of MI, percentage of average MI, initial adjust time of Remote MI, %increase of time, service periods of Remote MI].

CM4: [K m4 , cover time of MI, initial adjust time of MI, %increase of time, low percentage offered by contracted manufacturer, high percentage offered by contracted manufacturer].

CM5: [K m5 , cover time of MI, initial adjust time of MI, %increase of time, low percentage offered by contracted manufacturer, high percentage offered by contracted manufacturer, h rec].

The mathematical representation for CM1-CM5 is given by the following equations; where equations are differentiated by the corresponding CMi, the values of parameters K mi are given to indicate the active mechanism.

| (1) |

| (2) |

| (3) |

| (4) |

| (5) |

| (6) |

| (7) |

| (8) |

| (9) |

Eq. (1) represents the stock equation for MI in end-products. There are two inflows adding to the MI. The first inflow is the production rate (see Eq. (2)). The second (fill rate for MI), is defined by Eq. (3) (it is activated during the recovery period under CM3; further details are given below).

In Eq. (2), production rate is defined for the pre-disaster period, post-disaster period and during the recovery period h D, as the combination of the expected wholesaler's orders with an adjustment that brings the MI in line with its desired value (desired MI). Production rate is subject to the availability of actual stock in parts. During the period h D, the dual variable reduced production rate defines a zero production capacity or a percentage of reduction in production capacity, while during the period h rec the number of shifts is defined by Eq. (4) (one shift operation for active CM1, CM3, CM4, CM5, but two shift operation for active CM2). The percentage offered by contracted manufacturer in Eq. (2) is defined by Eq. (5) under CM4 or CM5, while the expected wholesaler's orders is a forecasted value for wholesaler's orders (see Fig. 3 and Eq. (9)) calculated from a first-order exponential smoothing. The adjustment of MI is based on a proportional rule that controls the discrepancy (discrepancy of MI) between desired MI and actual MI (Eq. (6)). The adjustment time (adjust time of MI) represents how quickly the manufacturer decides to close the gap between the desired and the actual inventory level. It is defined by Eq. (7), where the parameter %increase of time expresses the increase in the initial value of adjustment time (resulting in slow adjustments) due to the disaster effect.

The outflow from MI (shipment to wholesaler) is defined by Eq. (8) (the wholesaler's orders backlog is shown in Fig. 3). The formulation of Eq. (8) depends on active CMi; the same formulation for CM1, CM2 and CM3, but different for CM4 and CM5 depending on the percentage offered by contracted manufacturer (see Eq. (5)). The desired level of MI is defined by the following Eq. (10):

| (10) |

where, cover time of MI is the base stock expressed in time units.

Finally, the production rate1 activated in scenario BS3, represents additional end-product production during normal operating conditions (pre-disaster, post-disaster), for building a remote inventory (Remote MI). This rate is defined by Eq. (11) in order for the actual level of Remote MI to be aligned with its desired level (planned Remote MI) subject to the adjustment time (adjust time of Remote MI); the discrepancy between planned and actual values is given by Eq. (12), while the planned values of remote inventory are defined by Eq. (13) as a percentage of average MI.

| (11) |

| (12) |

| (13) |

Production rate1 increases the level of Remote MI subject to the availability of actual stock in parts. Remote MI is depleted by fill rate for MI (see Eq. (3)), which increases the actual level of MI in order to satisfy demand set by the wholesaler. The definition of Remote MI is given by Eq. (14):

| (14) |

| (15) |

| (16) |

where,

| (17) |

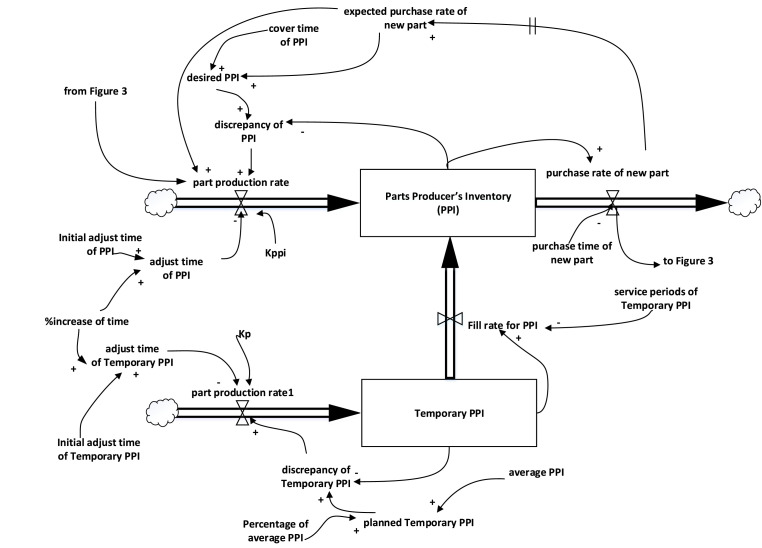

4.2.2. Parts producer: CM6

Fig. 5 presents the stock and flow structure of CM6, which controls the serviceable inventory at parts producer level (Parts Producer's Inventory (PPI)).

Fig. 5.

Stock and flow structure of CM6.

The inventory of the parts producer (Parts Producer's Inventory (PPI)) is increased by two inflows, namely part production rate and fill rate for PPI, and it is depleted by supplies to the manufacturer (purchase rate of new parts). As already discussed, the manufacturer's needs in parts are satisfied with priority over remanufactured parts, and the remaining unsatisfied part is fulfilled by purchase rate of new parts. Due to the side effects of a disaster event hitting the manufacturer, purchase rate of new parts becomes zero or decreases during period h D. At the same time, CM6 builds a temporary inventory (Temporary PPI) through the activation of part production rate1. This inventory is used to manage the manufacturer's future orders during the post-disaster period, as these orders are expected to increase compared with those placed during the pre-disaster period. By regulating the values of part production rate1, CM6 brings the actual values of Temporary PPI in line with a predefined desired state (planned Temporary PPI). This desired level is defined as a percentage of the average values (average PPI) of Parts Producer's Inventory. The Temporary PPI is depleted by fill rate for PPI, which is activated only during the post-disaster period; the values of this fill rate are subject to service periods of Temporary PPI.2

| (18) |

| (19) |

where fill rate for PPI is defined by Eq. (26) and expected purchase rate of new part is a forecasted value for supply-orders in new parts placed by the manufacturer and directed to the parts producer (purchase rate of new part) - see Fig. 3. These forecasted values are calculated from a first-order exponential smoothing.

| (20) |

| (21) |

| (22) |

| (23) |

| (24) |

| (25) |

| (26) |

Adjust time of PPI, adjust time of Temporary PPI and service periods of Temporary PPI are formulated in a way similar to that presented for the case of adjust time of MI (see Eq. (7)).

Finally, if the side effects of the disaster event on the operation of parts producer results in zero production during period h D, the production rate of parts producer is defined by Eq. (27) instead of Eq. (19). This case is activated by means of on/off control parameter K ppi (1 active production, 0 non-active production).

| (27) |

CM6 is activated or deactivated by means of on/off control parameter K p (1/0 values). The set of control parameters that fully describe CM6 is the following:

CM6: [K p , K ppi , cover time of PPI, initial adjust time of PPI, percentage of average PPI, initial adjust time of Temporary PPI, % increase of time, service periods of Temporary PPI].

4.3. Control mechanisms and reverse supply chain equations

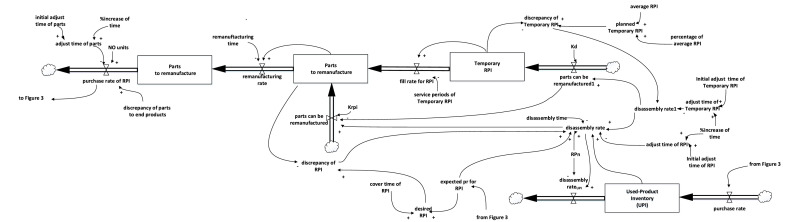

4.3.1. Disassembly center: CM7

Fig. 6 presents the stock and flow structure of CM7, which controls the serviceable inventory in remanufacturable parts (Remanufacturable Part Inventory (RPI)) obtained by disassembling (disassembly rate) used-products (Used-Product Inventory (UPI)) at the disassembly center. In addition, the mechanism builds a temporary inventory in remanufacturable parts (Temporary RPI) only during h D and controls its inventory level as well. As in the case of the parts producer, this temporary inventory is built to deal with the manufacturer's rather increased needs for remanufactured parts within the post-disaster period.

Fig. 6.

Stock and flow structure of CM7.

In particular, disassembly rate is regulated in a similar way to that presented in the previous subsection in order for the actual values of RPI and Temporary RPI to be aligned with their desired states (desired RPI and planned Temporary RPI respectively). The disassembly rate is defined as follows:

| (28) |

where, expected pr for RPI is the expected values of manufacturer's demand for parts (total amount of the part - see Fig. 3), while RP n is for each n = 1, …N, the amount of the remanufacturable parts obtained by disassembling one item of used-product.

The control of RPI is obtained by the following Eqs. (29), (30):

| (29) |

| (30) |

In Eq. (28), disassembly rate1 is activated during the period h D and represents the needs for building Temporary RPI. It is defined by the following equations:

| (31) |

| (32) |

| (33) |

Parts can be remanufatured1 as defined by Eq. (34) increases Temporary RPI:

| (34) |

On the other hand, parts can be remanufactured is defined by Eq. (35) and increases Parts to remanufacture (Eq. (38)):

| (35) |

Temporary RPI is depleted by fill rate for RPI, which is activated during the post-disaster period (t > t D + h D) according to the following Eqs. 36 and 37:

| (36) |

| (37) |

The definition of stock equations for Parts to remanufacture and RPI are given by Eqs. (38), (39):

| (38) |

| (39) |

where,

| (40) |

| (41) |

Finally, if the side effects of the disaster event on the operation of disassembly center results in zero remanufacturing activities during period h D, the amount of parts which can be remanufactured are defined by Eq. (42) instead of Eq. (35). This case is activated by means of on/off control parameter K rpi (1 active remanufacturing, 0 non-active remanufacturing).

| (42) |

CM7 is activated or deactivated by means of on/off control parameter K d (1/0 values). The set of control parameters that fully describe CM7 is the following:

CM7: [K d , K rpi , cover time of RPI, initial adjust time of RPI, percentage of average RPI, initial adjust time of Temporary RPI, %increase of time, service periods of Temporary RPI].

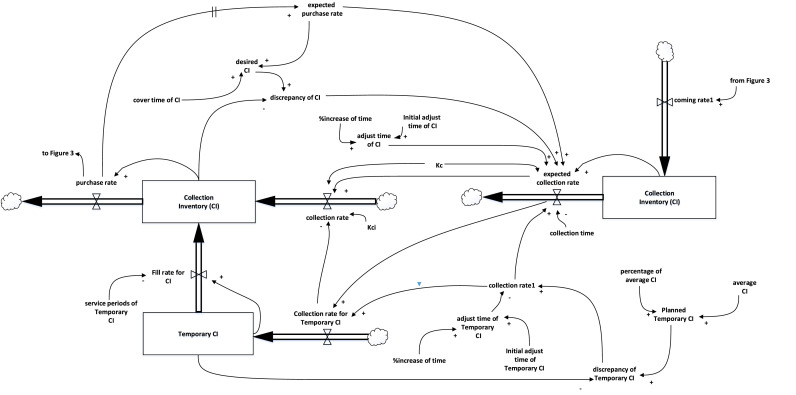

4.3.2. Collector: CM8

Fig. 7 presents the stock and flow structure of CM8, which controls the serviceable inventory in collected used-products (Collection Inventory (CI)). The description of the structure of CM8 is similar to that of CM7. When there is no disaster event, expected collection rate is planned for increasing CI, which is depleted by supplies in used-products to the disassembly center (purchase rate). When a disaster event occurs, expected collection rate starts to build a temporary inventory (Temporary CI) during period h D. When the manufacturer returns to a normal operating condition (post-disaster period), expected collection rate is planned for increasing CI, which is now filled also by fill rate for CI.

Fig. 7.

Stock and flow structure of CM8.

The mathematical representation for controlling CI is provided by the following Eqs. (43), (44), (45), (46):

| (43) |

| (44) |

where, expected purchase rate is a forecasted value for supply-orders in used-products placed by the disassembly center and directed to the collector (purchase rate should satisfy rate of used-products – see Fig. 3). These expected values are calculated from a first-order exponential smoothing.

| (45) |

| (46) |

The mathematical representation for controlling Temporary CI is provided by the following Eqs. (47), (48), (49), (50), (51), (52), (53):

| (47) |

| (48) |

| (49) |

| (50) |

| (51) |

| (52) |

| (53) |

If the side effects of the disaster event on the collector results in zero collection activities during period h D, Eq. (53) shall be differentiated as follows:

| (54) |

This case is activated or deactivated by means of on/off control parameter K ci (1/0 values).

Control parameter K c, which takes the values 1/0, activates or deactivates CM8. The set of control parameters that fully describe CM8 is the following:

CM8: [K c , K ci , cover time of CI, initial adjust time of CI, percentage of average CI, initial adjust time of Temporary CI, %increase of time, service periods of Temporary CI].

4.4. Profit equations

Profit equations are provided through profit per period (Profit) and Total Profit as the sum of Profit (profit per simulation time-step) over the simulation horizon. The Profit is captured by monetary flows created by physical flows per period (Profit calculation in Fig. 3).

| (55) |

| (56) |

Sales and Price refer to market demand. Operational Costs include: (i) production, inventory holding, and transportation costs in the forward channel, i.e. the sum of operational costs for the raw materials supplier, the parts producer, the manufacturer, the wholesaler and the retailer; (ii) collection, disassembly, remanufacturing, recycling, transportation, holding, and disposal costs in the reverse channel, i.e. the sum of operational costs for the collector, the disassembly center, the remanufacturer, and the recycler; and (iii) cost of supplies by a contracted third-party manufacturer in the case of scenarios BS4 and BS5. The detailed income/cost equations are based on standard calculations.

5. The case of COVID-19 - numerical experimentation and discussion

Since the outbreak of coronavirus (COVID-19 disease) on December 19, 2019, in the city of Wuhan, China, the number of infections and deaths has been rapidly increasing globally, thus justifying its declaration as a pandemic by the World Health Organization on March 11, 2020.

One of the sectors most affected by the pandemic is the supply chain in all its aspects due to the restrictive measures (including full lockdowns) imposed in most countries of the world, even in economically developed ones (Suborna, 2020). The impact of COVID-19 on the operations of supply chains worldwide can be classified as unknown-unknown effects, in the category of catastrophic events (Pawson et al., 2020). This particular nature of the COVID-19 gives rise to uncertainties and disturbances, which should be managed in the best possible way in order to restore balance in the system at the transportation level (Maureen et al., 2020) and, consequently, at the financial level. Specific disruption scenarios are used to develop and test supply chain resilience models, while uncertainty associated with threats, including consideration of “unknown-unknowns”, remains rare. This is because most publications focus only on supply chain networks and exclude associated system components from their research, thus creating a gap that needs to be bridged (Maureen et al., 2020). Ivanov, 2020a, Ivanov, 2020b adopts a new term, the viable supply chain (VSC), as an underlying SC property spanning three perspectives, which could help firms in their decisions on recovery and re-building of their SCs after global, long-term crises such as the COVID-19 pandemic. These perspectives are agility, resilience, and sustainability.

5.1. Development and validation of the SD model

The modeling approach of a disaster event given in subsection 4.1, along with the stock-flow structures of CMs presented in subsections 4.2-4.3, are integrated into the generic model structure shown in Fig. 3. The resulting larger picture of the stock and flow diagram is given in, Appendix A while the full equations of the SD model in Powersim®10 format are given in Appendix B. For clarity reasons, all Powersim equations are given in alphabetical order and categorized as stock (Appendix B1), flow (Appendix B2), and auxiliary equations (Appendix B3). The full SD model includes several types of parameters (inputs) that can be tuned to reproduce the behavior of a specific system: (i) operational costs given in Appendix B4 (the values of these parameters are selected based on those given in Table 2 ); (ii) smoothing factors used in forecasting through first order exponential smoothing operations given in Appendix B5.1; (iii) operational parameters that describe inventory control policies (inventory cover times and adjustment times) given in Appendix B5.2. (the values of these parameters are selected as median values based on those given in Table 3 ); (iv) physical parameters which depend on product and operation characteristics (such parameters are number of parts per end-product, and processing, shipment, delivery and inspection times, price) which are given in Appendix B5.3.

Table 2.

Typical values of cost parameters in CLSCs.

| Product | Variable | Value | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Electrical and electronic equipment | collection cost | 9,8 €/item | Besiou et al. (2012) |

| Electric and electronic products | Disassembly cost | 0,85 €/item | Karagiannidis et al. (2005) |

| Non defined product | MI holding cost | 0,80–1,00 €/item | Schmidt and Singh (2012) |

| Electrical and electronic equipment | recycling cost | 3028 €/item | Besiou et al. (2012) |

| Electrical and electronic equipment | RMSI holding cost | 0,725 €/item/week | Besiou et al. (2012) |

| Non defined product | 0,60€/item/week | Schmidt and Singh (2012) | |

| Non defined product | W transportation cost | 0,60€/item | Rozhkov et al. (2022) |

| Electrical and electronic equipment | UPI holding cost | 0,725 €/item/week | Besiou et al. (2012) |

| Electrical and electronic equipment | WI holding cost | 0,725 €/item/week | Besiou et al. (2012) |

Table 3.

Typical values of time parameters in CLSCs.

| Product | Variable | Value | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Electrical and electronic equipment | Initial inventory adjust time | 1 week | Besiou et al. (2012) |

| undefined product | 1–10 weeks |

Chang and Lin (2019) Rabelo et al. (2011) Udenio et al. (2015) |

|

| undefined product | |||

| chemical product | |||

| Electrical and electronic equipment | cover time | 2–8 weeks | Besiou et al. (2012),Rabelo et al. (2011) |

| undefined product | |||

| Electrical and electronic equipment | Purchase time of new material + adjust time of parts | 2 weeks | Besiou et al. (2012) |

| Electrical and electronic equipment | shipment time to retailer + delivery time | 2 weeks | Besiou et al. (2012) |

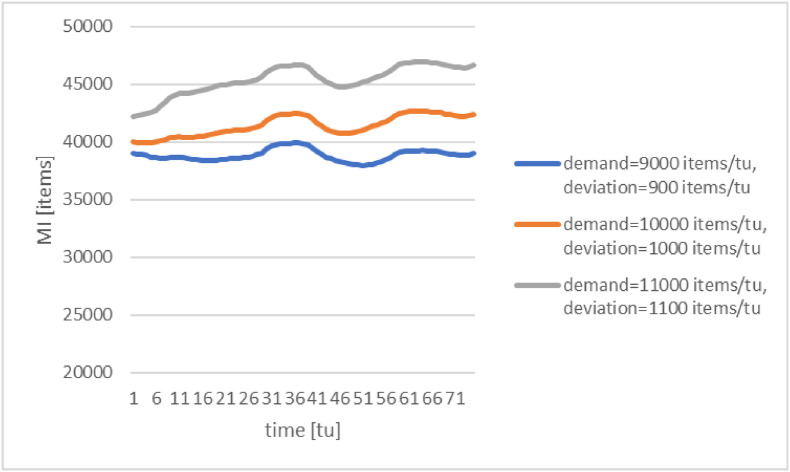

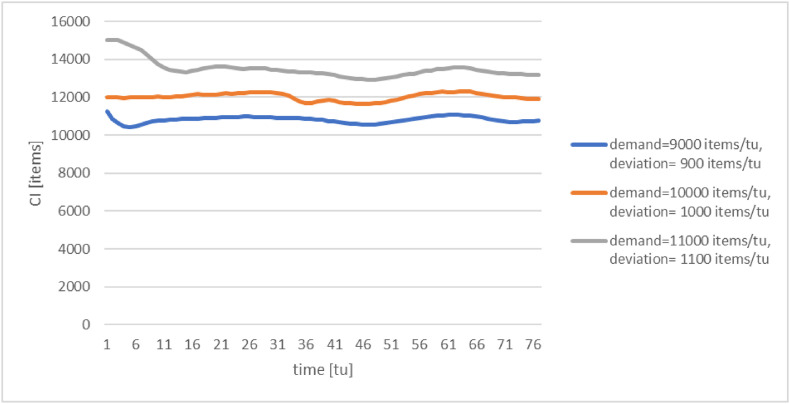

The model's validity was checked by conducting tests suggested by the SD literature (Forrester and Senge, 1980; Sterman, 2000; Barlas, 2000). First, the model's dimensional consistency was checked. Then, extreme condition tests were conducted, checking whether the model behaves realistically even under extreme situations. For example, it was checked that as inflows into serviceable inventories (manufacturer's inventory, wholesaler's inventory, and retailer's inventory) are sequentially set to zero, all stock and flows gradually approach zero. In addition, if no used-products are collected, only original materials and new parts are used for production and also, if there is no demand production ceases. The model was further validated by testing the behavior of partial models. As shown in Fig. 8, Fig. 9 , these tests revealed that the model behavior exhibits meaningful sensitivity to selected parameters and reasonable value variations (up to 10%) of these parameters yielded the same qualitative behavior. Integration error tests were subsequently conducted to test for changes in behavior by cutting the simulation time step (dt) in half and also by using different integration methods (Euler, Runge-Kutta). The model employs the Euler integration method with time-step equal to 1 week, while the results of integration tests indicated no integration errors. Finally, under settings given in Gu and Gao (2012), the disaster-free model replicated the same behavior.

Fig. 8.

MI level studied with sensitivity analysis.

Fig. 9.

CI level studied with sensitivity analysis.

5.2. Settings

The SD model was executed for a simulation horizon of 18 months with time-step equal to 1 week. Demand for end-products follows a normal distribution function [Demand ∼ N(10,000 items/week, 1000 items/week]. The end-product is produced by assembling N = 5 parts. The sale price of the end-product is equal to 200 € per item, while the values of the cost parameters in Appendix B4 represent furnishings and household equipment (major household appliances -electric or not- and small electric household appliances).

Regarding the modeling of COVID-19 effect, the time of occurrence of COVID-19 event is set to t D = 10 weeks (occurrence in mid-March 2020). The duration of the recovery period (h D) is equal to 6 weeks (mean time of quarantine period due to COVID-19 in mid-March 2020) taking into account the elements mentioned by Oraby et al. (2022), while h rec is set at 4 weeks.

The settings for the values of parameters associated with the description of all CMs are as follows:

CM1: [K m1 = 1, cover time of MI = 4 weeks, initial adjust time of MI = 4 weeks, %increase of time = 30%]

CM2: [K m2 = 1, cover time of MI = 4 weeks, initial adjust time of MI = 4 weeks, %increase of time = 30%, h rec = 4 weeks]

CM3: [K m3 = 1, cover time of MI = 4 weeks, initial adjust time of MI = 4 weeks, percentage of average MI = 100%, initial adjust time of Remote MI = 4 weeks, %increase of time = 30%, service periods of Remote MI = 2 weeks].

CM4: [K m4 = 1, cover time of MI = 4 weeks, initial adjust time of MI = 4 weeks, %increase of time = 30%, low percentage offered by contracted manufacturer 5%, high percentage offered by contracted manufacturer = 10%].

CM5: [K m5 = 1, cover time of MI = 4 weeks, initial adjust time of MI 4 weeks, %increase of time 30%, low percentage offered by contracted manufacturer = 5%, high percentage offered by contracted manufacturer = 10%, h rec = 4 weeks].

CM6: [K p = 0/1, K ppi = 0/1, cover time of PPI = 2 weeks, initial adjust time of PPI = 4weeks, percentage of average PPI = 100%, initial adjust time of Temporary PPI = 4 weeks, % increase of time = 30%, service periods of Temporary PPI = 2 weeks].

CM7: [K d = 0/1, K rpi = 0/1, cover time of RPI = 2weeks, initial adjust time of RPI = 4 weeks, percentage of average RPI = 100%, initial adjust time of Temporary RPI = 4weeks, %increase of time 30%, service periods of Temporary RPI = 1 week].

CM8: [K c = 0/1, K ci = 0/1, cover time of CI = 2weeks, initial adjust time of CI = 2weeks, percentage of average CI = 100%, initial adjust time of Temporary CI = 4weeks, %increase of time = 30%, service periods of Temporary CI = 1 week].

All parameters that are not explicitly handled by the experimental design are set equal to the values of Appendix B5.

5.3. Recommendations for mitigating COVID-19 effects

We concentrate on the efficiency of the five business scenario settings (BS1-BS5) for the manufacturer in responding to wholesaler's orders. Specifically, we examine the dynamic response of the system under scenarios (recall from Table 1 BS1-BS5 with the embedded CM1, CM2, CM3, CM4 and CM5 settings) in combination with: (i) 26 sets of value for CM6-CM8 (CM6 (K p = 0/1, K ppi = 0/1), CM7(K d = 0/1, K rpi = 0/1) and CM8 (K c = 0/1, K ci 0/1)); (ii) two sets of value for the reduction of production rate (50%, 100%) and three sets of value for the reduction of demand (0%, 20%, 50%) due to the COVID-19 phenomenon. All possible combinations (5*26*2*3 = 1920) represent a broad area of response scenarios for mitigating the COVID-19 effects.

For each combination, 20 repetitive simulation runs were conducted to test for alternative generators of random numbers (used in definition of Demand), giving thus a total of 1920*20 = 38,400 runs. In each run, the values of stock variables and of smoothing functions were firstly initialized by considering an initialization horizon of 200 weeks, in order to capture the system's behavior outside its transient region. Thereafter, a simulation horizon of 18 months, starting at t = 0 and using time-step equal to 1 week, represents the real-time experimentation for each combination. Throughout investigation, the CLSC profitability (profit per week (Profit) – see Eq. (55), Total profit - see Eq (56) and manufacturer's stock level (MI – see Eq. (1)), during the recovery and post-disaster period (as the mean values of 20 repetitive runs) are considered as the output of the relative combinations. The output results are presented as ratios to the corresponding values obtained by the simulation run of the basic scenario (i.e. Profit index, Total profit index, MI index); the basic scenario (BBS) refers to a CLSC operation under normal conditions (disaster-free model - see Table 1).

-

(i)

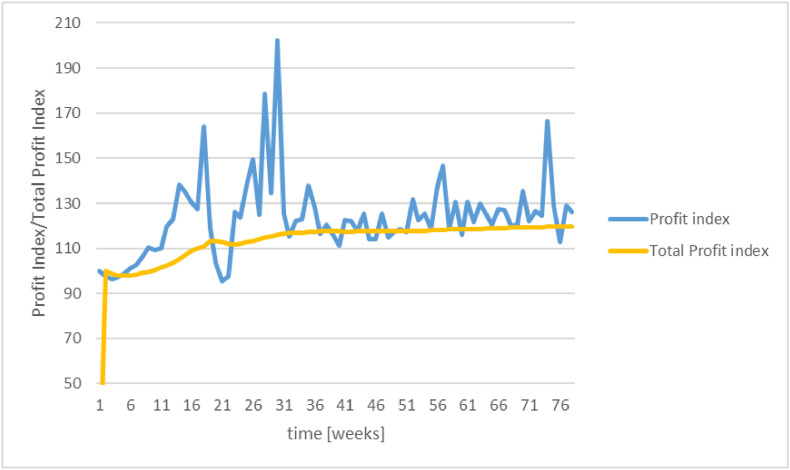

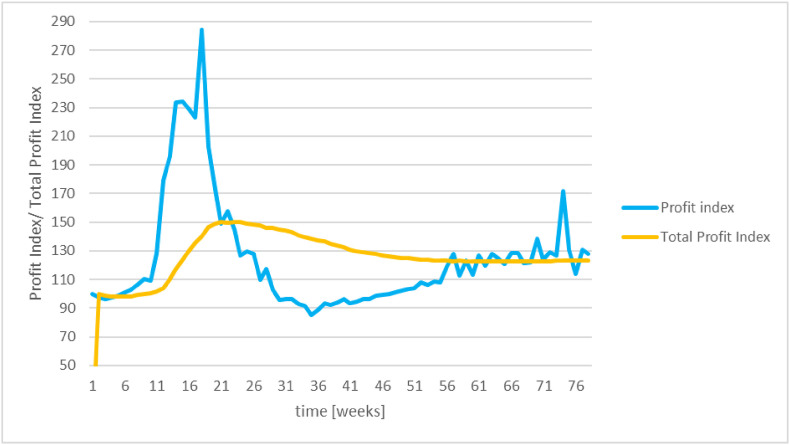

Profitability: For the recovery and post-disaster period, Table 4 displays the best and worst mitigation policies for each combination of reduction of production rate and reduction of demand. The lower/upper limits of the Total profit index express the detected minimum/maximum values. Depending on the combination, it turns out that the best policy recommendations are either BS1 or BS5. Both policies bring profitability back to its pre-disaster levels. For each policy, recommendations regarding the activation of CM6-CM8 are also indicated in Table 4. On the contrary, BS3 forms the worst policy choice as it leads to high profit loss for all combinations. Fig. 10 and Fig. 11 provide an explanation of Total profit index, through the dynamics of Profit index for scenarios BS1 and BS2 respectively, in combination with the corresponding values of the parameters for CM6-CM8, for which the best policy is identified.

-

(ii)

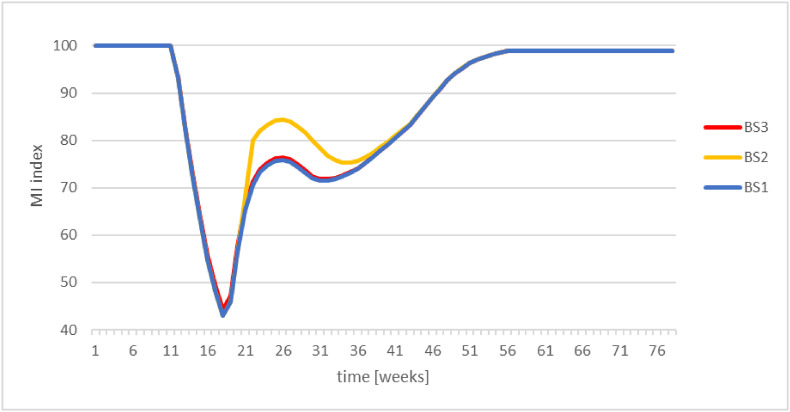

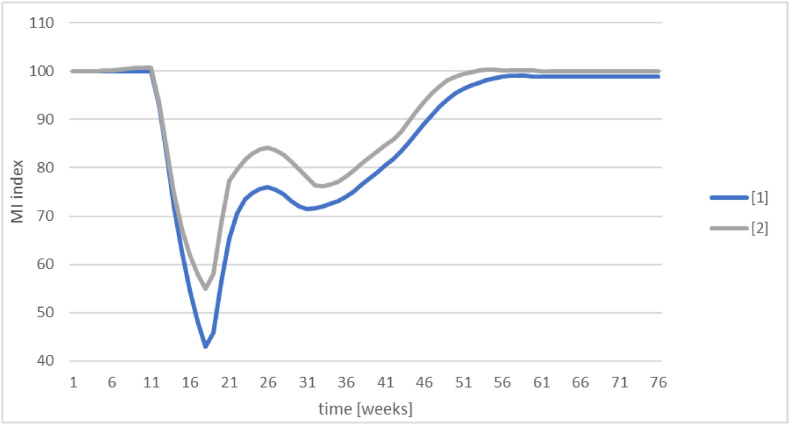

Manufacturer's inventory (MI): We study the dynamic behavior of MI for all combinations of reduction of production rate and reduction of demand to identify those BSs with minimal effects on the manufacturer's stock level. For each BS, Table 5 displays the values of the MI index at the time that the state of the MI enters equilibrium (nearly constant). It displays also, the minimum values of the MI index detected after the occurrence of COVID-19 effect. It turns out that for all combinations the values of index at the equilibrium state range between 96,70 and 99,60 for BS1, BS2 and BS3, thus forming, effective mitigation policies which bring the stock level back almost to its pre-disaster levels. BS4 and BS5 seem to be less effective policy suggestions (range 89,50 to 89,90). The time that the state of MI enters equilibrium is also indicated inside Table 5; after 40–45 weeks from the occurrence of the COVID-19 event for scenarios BS1, BS2 and BS3, while after 50–60 weeks for scenarios BS4 and BS5. Regarding the minimum values of MI index, these appear during the first 3 weeks of the post COVID-19 period for scenarios BS1, BS2 and BS3, while during the first 6 weeks for scenarios BS4 and BS5. Almost zero values are observed for 100% reduction of production rate under scenarios BS1, BS2 and BS3. Based on detailed experimental results not shown for brevity, it is noticeable that the aforementioned key observations are independent from the parameter values for CM6-CM8. Fig. 12 provides an explanation of ΜΙ index, through its dynamics under the best policies BS1, BS2 and BS3.

Table 4.

Best/worst mitigation policies.

| reduction of production rate | reduction of demand | Best/Worst cases | BS | CM6 |

CM7 |

CM8 |

Total Profit index |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower |

Upper |

||||||||||

| Kp | Kppi | Kd | Krpi | Kc | Kci | ||||||

| 0% | 0% | Basic scenario | 100 | 100 | |||||||

| 50% | 50% | Best | BS1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 82.02 | 113.49 |

| Worst | BS3 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 46.10 | 86.56 | ||

| 50% | 20% | Best | BS1or BS2 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 102.27 | 119.88 |

| Worst | BS3 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 73.76 | 92.06 | ||

| 100% | 50% | Best | BS1or BS2 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 93.97 | 113.06 |

| Worst | BS3 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 61.82 | 87.15 | ||

| 100% | 20% | Best | BS5 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 102.44 | 130.91 |

| Worst | BS3 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 79.07 | 98.00 | ||

| 50% | 0% | Best | BS5 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 100.57 | 136.64 |

| Worst | BS3 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 77.33 | 96.70 | ||

| 100% | 0% | Best | BS1or BS2 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 104.01 | 150.01 |

| Worst | BS3 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 79.07 | 115.94 | ||

Fig. 10.

Profit index and Total Profit index for 50% reduction of production rate and 20% reduction of demand. Scenario BS1

CM1: [Km1 = 1, cover time of MI = 4 weeks, initial adjust time of MI = 4 weeks, %increase of time = 30%]

CM6: [Kp = 0, Kppi = 1, cover time of PPI = 2 weeks, initial adjust time of PPI = 4weeks, percentage of average PPI = 100%, initial adjust time of Temporary PPI = 4 weeks, % increase of time = 30%, service periods of Temporary PPI = 2 weeks].

CM7: [Kd = 1, Krpi = 1, cover time of RPI = 2weeks, initial adjust time of RPI = 4 weeks, percentage of average RPI = 100%, initial adjust time of Temporary RPI = 4weeks, %increase of time 30%, service periods of Temporary RPI = 1 week].

CM8: [Kc = 1, Kci = 0, cover time of CI = 2weeks, initial adjust time of CI = 2weeks, percentage of average CI = 100%, initial adjust time of Temporary CI = 4weeks, %increase of time = 30%, service periods of Temporary CI = 1 week].

Fig. 11.

Profit index and Total Profit index for 100% reduction of production rate and 0% reduction of demand Scenario BS2

CM2: [Km2 = 1, cover time of MI = 4 weeks, initial adjust time of MI = 4 weeks, %increase of time = 30%, hrec = 4 weeks]

CM6: [Kp = 0, Kppi = 1, cover time of PPI = 2 weeks, initial adjust time of PPI = 4weeks, percentage of average PPI = 100%, initial adjust time of Temporary PPI = 4 weeks, % increase of time = 30%, service periods of Temporary PPI = 2 weeks].

CM7: [Kd = 0, Krpi = 1, cover time of RPI = 2weeks, initial adjust time of RPI = 4 weeks, percentage of average RPI = 100%, initial adjust time of Temporary RPI = 4weeks, %increase of time 30%, service periods of Temporary RPI = 1 week].

CM8: [Kc = 0, Kci = 1, cover time of CI = 2weeks, initial adjust time of CI = 2weeks, percentage of average CI = 100%, initial adjust time of Temporary CI = 4weeks, %increase of time = 30%, service periods of Temporary CI = 1 week].

Table 5.

Results of MI index.

| reduction of production rate | reduction of demand | Scenarios |

MI index |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Min | Equilibrium state (value/time [week]a) | |||

| 0% | 0% | BBS | 100 | 100/0 |

| 50% | 50% | BS1 | 42.92 | 98.90/41 |

| BS2 | 42.92 | 98.90/41 | ||

| BS3 | 44.22 | 98.90/41 | ||

| BS4 | 20.98 | 89.50/50 | ||

| BS5 | 21.44 | 89.50/50 | ||

| 50% | 20% | BS1 | 38.42 | 99.36/42 |

| BS2 | 38.42 | 99.36/41 | ||

| BS3 | 39.72 | 99.36/41 | ||

| BS4 | 23.08 | 89.60/50 | ||

| BS5 | 21.26 | 89.60/50 | ||

| 100% | 50% | BS1 | 0.09 | 98.90/42 |

| BS2 | 0.09 | 98.90/42 | ||

| BS3 | 0.42 | 98.90/42 | ||

| BS4 | 20.98 | 89.80/53 | ||

| BS5 | 17.54 | 89.80/53 | ||

| 100% | 20% | BS1 | 0.09 | 99.25/41 |

| BS2 | 0.09 | 99.20/41 | ||

| BS3 | 0.41 | 99.25/41 | ||

| BS4 | 23.08 | 89.80/56 | ||

| BS5 | 21.82 | 89.80/53 | ||

| 50% | 0% | BS1 | 33.92 | 99.66/40 |

| BS2 | 33.39 | 99.66/40 | ||

| BS3 | 34.69 | 99.66/40 | ||

| BS4 | 25.53 | 89.80/60 | ||

| BS5 | 25.25 | 89.80/60 | ||

| 100% | 0% | BS1 | 0.09 | 96.43/45 |

| BS2 | 0.09 | 96.42/45 | ||

| BS3 | 0.41 | 96.70/45 | ||

| BS4 | 25.53 | 89.80/60 | ||

| BS5 | 27.10 | 89.90/60 | ||

In number of weeks (t-tD).

Fig. 12.

MI index for 50% reduction of production rate and 50% reduction of demand cover time of MI = 4 weeks, initial adjust time of MI = 4 weeks, %increase of time = 30%.

Scenario BS1: CM1 [Km1 = 1]

Scenario BS2: CM2 [Km2 = 1, cover time of MI = 4 weeks, hrec = 4 weeks]

Scenario BS3: CM3 [Km3 = 1, percentage of average MI = 100%, initial adjust time of Remote MI = 4 weeks, service periods of Remote MI = 2 weeks].

As it appears from the results in Table 5 BS4 and BS5 (not shown in Fig. 12) are less effective suggestions. In particular, the transition period to equilibrium state is much longer in BS4 and BS5 compared to BS1, BS2 and BS3 (9–20 weeks). Especially for the case of BS1, Fig. 13 illustrates the dynamics under different inventory control in order to explain the speedy response to emergency conditions. It appears from the results in Fig. 13 that for an initial adjust time of MI that is equal to 2 weeks, the system enters equilibrium 5 weeks earlier compared to an initial adjust time of MI that is equal to 4 weeks.

Fig. 13.

BS1 for alternative values of initial adjust time of MI for 50% reduction of production rate and 50% reduction of demand cover time of MI = 4 weeks, %increase of time = 30%

[1] CM1: [Km1 = 1, initial adjust time of MI = 4 weeks]

[2] CM1: [Km1 = 1, initial adjust time of MI = 2 weeks].

It is important to mention, though, that best (and worst) policy recommendations which are discussed in this subsection are still the best (and worst) choices under different settings for operational parameters (Appendix B5).

-

(iii)

Main findings: Taking all the above into consideration, we observe that various best policy choices emerge in order to address the disruptions caused by the advent of COVID-19 at an economic as well as a manufacturer's inventory level. These choices differ depending on the targeted outcome. If our target is to: a) restore the system to a pre-COVID-19 state from an economic perspective; and b) achieve (if possible) a higher total profit compared to the Basic Scenario, we should first and foremost consider the percentage of reduction of production rate and demand. In case the reduction of production rate and demand are 100% and 20% respectively, or 50% and 0% respectively, contracting with a third-party manufacturer is deemed the best policy choice. In the rest of the cases, best solutions revolve around the preservation of basic stock during the pre-COVID-19 period and the inclusion of additional shifts when production returns to pre-COVID-19 levels.

On the other hand, if we aim to restore MI to pre-COVID-19 levels as soon as possible, we should implement basic stock preservation policies. Creating remote inventory by the manufacturer in order to supply the wholesaler during the recovery period is the worst choice in terms of profit. What is more, system adjustment plays an important role, as the system responds quicker when initial adjust time of MI receives lower values, which restores equilibrium faster.

For all best scenarios, in order to study the impact of recovery time (h D) on both profitability and MI, we investigate the system response under two additional sets of value; h D = 7 weeks and h D = 12 weeks. These values were considered as representative values for a lockdown period due to COVID-19, given that no lockdown period of less than 6 weeks or of more than 12 weeks has ever been observed in CLSC systems. The comparative examination of the results of this “what-if” analysis and of those obtained for h D = 6 weeks, leads to the following observations:

-

•

Best (and worst) policy recommendations for h D = 6 weeks are still the best (and worst) choices for all combinations of reduction of production rate and reduction of demand.

-

•

In terms of profitability, an increase in h D by 1 Week (7 weeks) has a very small (about 1,5%) impact on total profit for all combinations of reduction of production rate and reduction of demand. However, for the case of h D = 12 weeks significant losses arise: about 15% for 50% reduction of production rate and 50% reduction of demand (worst case); about 5% for the rest combinations.

-

•

In terms of manufacturer's inventory, the time that the inventory dynamics enter equilibrium remains the same for all combinations, but the MI index is now equal to 80 (reduction by 20%).

All the above-mentioned points can provide guidance for CLSC managers in order to implement appropriate policies before and during a disaster event, with the aim of reducing the impact as much as possible on the system's behavior. Settings regarding the reduction of wholesaler demand and reduction of production rate are indispensable in order to implement the most appropriate policy choice, especially if we desire to preserve an economically sustainable system.

6. Summary and future research

We presented a comprehensive dynamic model for a single manufacturer/multi-echelon CLSC with remanufacturing and recycling activities to study the system response under disaster effects. The model integrates the simulation discipline and the theory of nonlinear dynamics and feedback control into a dynamic consideration of CLSC networks. This approach allows the comprehensive description and dynamic analysis of the system elements (production/collection/disassembly/remanufacturing/recycling, inventories, cost, profit), taking into account interactions of the variables and actors represented in the model. The simulated CLSC generates the dynamics of the system as endogenous consequences of the embedded control mechanisms and provides an ‘‘experimental’’ tool for planning, testing and revealing effective business scenarios for mitigating the disaster effects. It should be noted that the SD model presented could be a tool for the managers of any SC for resilient supply chain management, with the purpose of creating a SC that will be resistant to risks. Configurating the SD model is indispensable for such a purpose: The SD model should be adapted to the features of each SC examined and appropriate values should be given each time for its fixed variables.

Under COVID-19 effects hitting the manufacturer, the model was illustrated through its application to a number of mitigation policy scenarios together with their side effects on the operations of other actors, using the CLSC profitability and manufacturer's stock during the recovery and post COVID-19 period as measures of performance. Extensive numerical experimentation provided recommendations for mitigation policies that are expected to perform best depending on the reduction in manufacturer's production, reduction in product demand and duration of disaster recovery period due to the COVID-19 outbreak.

The results presented in this paper certainly do not exhaust all aspects of disaster management in CLSCs. Coordinated operations among supply chain actors and optimized emergency supply chain operations to provide a speedy response to the presence of demand uncertainty could be open questions calling for policy formulation. The study under drastically increased demand (e.g. facial masks, hand sanitizer, disinfection spray) or under different remanufacturing settings could be also, additional areas in extending the scope of this paper. It could be assumed, for example, that the remanufacturing process may produce not only as-good-as-new products, but also B-class products directed to secondary markets.

Footnotes

The structure of CM1 reflects the structure on which is based the development of all mechanisms used in Gu and Gao (2012) (shown as BM1 - BM8 in Fig. 3). For example, in Fig. 3, mechanism BM1 controls the stock level at Raw Materials Supplier's Inventory (RMSI) to be aligned with its desired state by regulating the inflow (owing rate of new material) through the related parameters of cover time and adjusting time.

n = 1,2, … …..N for all array equations.

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijpe.2022.108593.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- Altay N., Green W.G., III OR/MS research in disaster operations management. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2006;175:475–493. [Google Scholar]

- Aydin N. vol. 256. 2020. (Designing Reverse Logistics Network of End-Of-Life-Buildings as Preparedness to Disasters under Uncertainty” Journal Of Cleaner Production). [Google Scholar]

- Barlas Y. Formal aspects of model validity and validation in system dynamics. Syst. Dynam. Rev. 2000;12(3):183–210. [Google Scholar]

- Bashiri M., Tjahjono B., Lazell J., Ferreira J., Perdana T. The dynamics of sustainability risks in the global coffee supply chain: a case of Indonesia–UK. Sustainability. 2021;13:589. [Google Scholar]

- Besiou M., Georgiadis P., Van Wassenhove L.N. Official recycling and scavengers: symbiotic or conflicting? Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2012;218(2012):563–576. [Google Scholar]

- Borja P., Mohamed M.N., Syntetos A.A. The effect of returns volume uncertainty on the dynamic performance of closed-loop supply chains. Journal of Remanufacturing. 2019;10:1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Bruneau M., Chang S.E., Eguchi R.T., Lee G.G., O'Rourke T.D., Reinhorn A.M., et al. A framework to quantitatively assess and enhance the seismic resilience of communities. Earthq. Spectra. 2003;19(4):733–752. [Google Scholar]

- Chang M.-S., Tseng Y.-L., Chen J.-W. A scenario planning approach for the flood emergency logistics preparation problem under uncertainty. Transport. Res. E Logist. Transport. Rev. 2007;43(6):737–754. [Google Scholar]

- Chang W.-S., Lin Y.-T. The effect of lead-time on supply chain resilience performance. Asia Pac. Manag. Rev. 2019;24:298–309. [Google Scholar]

- Chen J.X., Li G.H., Shi G.H. Supply chain system dynamics simulation with disruption risks. Ind. Eng. Manag. 2011;16(6):35–41. [Google Scholar]

- Chopra S., Sodhi M.S. MIT Sloan Management Review.; 2004. Managing Risk to Avoid Supply-Chain Breakdown. [Google Scholar]

- CRED . 2019. Disasters 2018: Year in Review. Brussels, April 2019. [Google Scholar]