Abstract

Introduction: Blood culture test is the gold standard test to diagnose bloodstream infections, but contamination is the main problem in this valuable test. False positive results in blood cultures are mainly due to contamination that occurs mostly during pre-analytical procedures like sample collection and sometimes during sample processing.

Materials and method:Our prospective observational study was undertaken at St. Theresa Hospital, Hyderabad, India, during January 2020–June 2020. Blood cultures received from inpatient departments (IPD) and outpatient departments (OPD) are included.

Sample size: The contamination rate was calculated by dividing the total number of contaminated blood cultures by the total number of cultures multiplied by 100.

Results:Blood culture contamination rate is 2.4%, which is within the limit as per the standard guideline.

Conclusion:Contamination occurred mainly due to improper disinfection of the skin and environmental contamination.

Keywords:bloodstream infections, blood culture contamination rate (BCC), blood culture, phlebotomy, antisepsis.

BACKGROUND

Contamination due to skin flora especially in a single culture makes interpretation difficult and may result in excessive and sometimes unnecessary use of antibiotics, with the risk of promoting bacterial resistance, increased morbidity and mortality, extended hospital stays, and increased costs.

Factors associated with blood culture contamination include poor technique and procedure used to collect blood, lack of dedicated phlebotomists, improper skin antisepsis. The acceptable blood contamination rate benchmark is <3% (1, 2).

INTRODUCTION

Blood culture is the gold standard method to detect bloodstream infections (bacteremia and septicemia). False positive results in blood cultures may occur due to contamination during preanalytical procedures like sample collection and, sometimes, during sample processing.

A contaminant is defined as a microorganism that is supposed to be introduced into the culture during either specimen collection or processing and that may not be pathogenic for the patient. Frequently isolated organisms as contaminants in blood culture include Staphylococci (CoNS), aerobic spare-bearing bacilli (ASB), Viridans group streptococci, Corynebacterium spp., Propionibacterium spp., Micrococcus spp., and Clostridium perfringens. Most of these organisms are present on the skin as normal commensal flora (1). Various studies show that the contamination rate ranges between 0.6-6% (2-4); it depends upon the sample collection method and processing in the laboratory. The benchmark of blood contamination rate is <3%, as proposed by the Clinical Laboratory Standard Institute (CLSI) (5). The present study was undertaken to estimate the rate of blood culture contamination, source of contamination and most prevalent organisms isolated during blood culture contamination.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

The present research is a prospective observational study conducted over a period of six months from January 2020 to June 2020 in a tertiary care hospital, Hyderabad, India. A total of 522 blood samples from IPD and OPD were collected. All age groups of patients with clinical suspicion of bacteremia were included in the study and those already started on antibiotics were excluded. Blood samples were collected as per the laboratory manual from IPD and OPD. The collection of the sample was noted in the checklist.

Collection procedure

Blood culture samples were collected before starting antibiotic therapy. The persons who collected them were instructed to follow strict infection control practices such as hand hygiene, including glove wearing. The venipuncture site was cleaned with 70% alcohol from the center to periphery and allowed to dry for 30 seconds; also, no attempt to palpate the vein after disinfection of the venipuncture site was done. Then, 5 mL of blood were collected and aseptically added into a 50 mL blood culture bottle (before adding the blood, the top of the bottle was cleaned with 70% alcohol) containing brain heart infusion (BHI) media. The blood to media ratio was 1:10. Once the sample was collected, it has been transported to the microbiology laboratory for processing. Culture bottles were incubated at 37°C for 24 hours and then inoculated into blood agar and McConkey agar, serially every day, for seven days, until growth was observed. Then, plates were further processed for identification of contamination and antibiotic sensitivity.

Identification of contamination

Contamination was considered if the following organisms were isolated after 24 hours of incubation: Staphylococcus aureus, Streptococcus pneumoniae, Escherichia coli, Klebsiella pneumonia, other Enterobacteriaceae, Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Candida albicans (3) as well as coagulase- negative Staphylococci (CoNS), Corynebacterium species, Bacillus species other than Bacillus anthracis, Propionibacterium acnes, Micrococcus species, Viridans group Streptococci, Enterococci, and Clostridium perfringens (3).

Calculation of blood culture contamination rate

The rate of blood culture contamination was calculated by dividing the total number of contaminated blood cultures by the total number of cultures multiplied by 100.

RESULTS

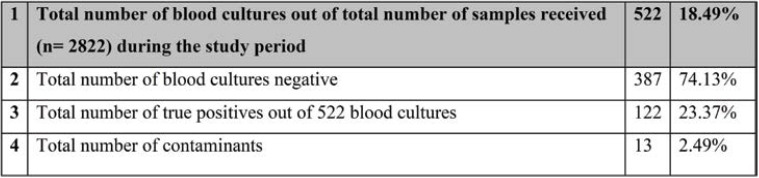

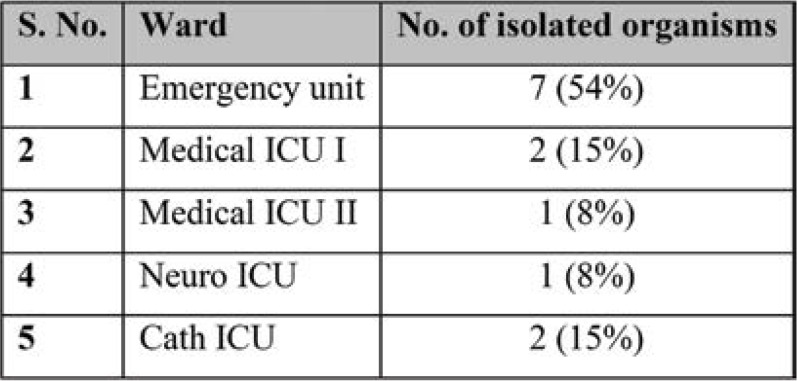

During this six-month period, a total of 2822 culture samples were received, of which 522 (18.49%) were blood cultures collected from both IPD and OPD departments. Thirteen of the 522 cultures were contaminated and the positivity rate was about 2.4% (Table 1). When compared with the previous data from July 2019 to December 2019, blood culture contamination (BCC) was higher, reaching 6.9% (28 out of 403 cultures were found to be contaminated). Age-wise and sex-wise distribution is shown in Table 2 and Figure 1. All contaminated blood cultures were received from the IPD: seven (54%) from the Emergency unit, three (23%) from Medical ICU I and II, two (15%) from Cath ICU, and one (8%) from Neuro ICU (Table 3). The following organisms were isolated in contaminated blood cultures in various proportions: Staphylococcus epidermidis [six (46.2%)], Staphylococcus hemolyticus [two (15.4%)], Staphylococcus citreus [one (7.7%)] and ABS [four (30.8%)] (Table 4).

Table 1 shows age-wise and sex-wise isolation of blood contaminants, and Figure 1 depicts age-wise isolated contaminants, with patients aged 56-65 and 66-75 years showing more contaminants. Six out of nine (>66%) patients in the 56-65-year age group had comorbidities, including diabetes mellitus and hypertension with cerebrovascular accident (CVA). The majority of these cases arrived at the Emergency unit after 4 pm, since the OPD was closed after 4 pm, and two of them were admitted after 6 pm, when the OPT was opened from 6 pm to 9 pm. Age-wise distribution showed one male patient <45 who presented with a road traffic accident, two patients aged 46-55 years, one male with fever and known diabetes mellitus, and one female with CVA, while in the age group of 56-65 years there were five high risk patients (three males and two females) with either hypertension, diabetes or cardiac problems.

The contamination rate was the highest in the Emergency unit, given the serious challenges posed for infection control and prevention. The highest incidence was seen in the evening. This is normal, because during this period of the work day nurses are very busy attending cases (the usual patient inflow is of two to three patients every hour) and need to change gloves and wash their hands for each important task they perform.

The questionnaire-based route cause analysis (Figure 2) revealed that 61.5% of the healthcare workers believed changing gloves was merely lack of time, 23% were not complying with hand hygiene and 7.69% failed to disinfect the hub of the bottle.

DISCUSSION

In the present study, the BCC rate is 2.4%, which is below the threshold rate as proposed by CLSI (<3%). Though the contamination rate has been set at 2% to 3%, actual rates appear to vary substantially amongst different institutions, ranging from as low as 0.6% to over 6% (4–6). In a one-year research from Nigeria, a contamination incidence of 10.4% was discovered (7). Lalezari et al reported that 50% of all positive blood cultures were found to contain contaminants (8). There is additional evidence to imply that these rates have been rising in recent decades. Technological advancements that enable the detection of lesser concentrations of living bacteria in the blood, greater use of indwelling catheters for therapy, and modifications in phlebotomy methods to reduce the danger of needlestick injuries have all been mentioned as explanations for the rise (9). In this study, we found that the contamination rate was generally higher in males than females, and cultures from elderly patients in the age group of 56-65 years were more vulnerable to contamination. This is consistent with the study done by Hemeg et al, who reported similar findings (10). This could be attributed to the difficulties in obtaining the less accessible veins in elderly people (11).

Determining the departments that produce the most BCC contamination should be the first step in reducing the rate of BCC. Culture contamination can be efficiently reduced by focusing on crowded departments with high rates of BCC such as IM and ICU, and applying particular procedures as part of quality improvement initiatives. In this study, all contaminated blood cultures were received from the IPD, including seven (54%) from the Emergency unit, three (23%) from Medical ICU I and II, two (15%) from Cath ICU and one (8%) from Neuro ICU. A similar study reported that surgical units had the highest rate of BCC (3.92%), followed by intensive care (2.61%) and medical units (2.48%) (12). The greater BCC incidence in the medical wards is connected to patients’ number and health status, since there are more older patients with comorbidities who are admitted in such settings, making blood collection problematic (10). Another study found that overcrowding in emergency rooms can result in BCC rates as high as 10% to 12% (13).

The following organisms were isolated in various proportions in contaminated blood cultures: Staphylococcus epidermidis [six (46.2%)], Staphylococcus hemolyticus [two (15.4%)], Staphylococcuscitreus [one (7.7%)] and ASB [four (30.8%)]. During venipuncture, bacteria from the normal physiological microbiota of both patients and staff can be transmitted to transport medium, which can be identified as BCC. Previous studies have reported that CoNS were the most prevalent bacterium identified from BCC (84.3%), which is inconsistent with the findings of the current study (10, 14, 15). In an analysis of 843 occurrences of positive blood cultures in adult inpatients from three hospitals throughout the country, Weinstein et al found that when specific organisms were isolated from a blood culture, they nearly invariably indicated real bacteremia or fungemia. Staphylococcus aureus, Streptococcus pneumoniae, Escherichia coli and other Enterobacteriaceae, Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Candida albicans were among the identified microbes (16). Another study reported that of 20 (24.7%) instances of clinically significant bacteremia, there were 10 (12.3%) episodes of ambiguous bacteremia, and 59 (72.8%) occurrences of contamination were found among 81 episodes of CoNS blood culture findings (17). When CoNS were isolated from blood cultures, other studies have found rates of genuine bacteremia ranging from 10% to 26.4% (18). Because bloodstream infections frequently include just one organism, doctors may mistakenly believe that a blood culture container containing many species is contaminated. However, investigations have indicated that polymicrobial bacteremias account for 6% to 21% of all genuine bacteremias, with the majority occurring among individuals in high-risk categories. As a result, the simple presence of several organisms in a blood culture bottle does not automatically imply blood culture contamination (19). Multiple sets of blood cultures have been suggested to work up possible bloodstream infections for these reasons. Culture contamination may be indicated by the existence of only one positive set among at least two sets obtained at the same time.

In our questionnaire-based route cause analysis, we found that 61.5% of healthcare workers believed changing gloves was merely lack of time, 23% were not complying with hand hygiene and 7.69% failed to disinfect the hub of the bottle. Contamination in blood cultures has been linked to a number of factors, including the use of existing indwelling or invasive devices like ports or intravenous catheters rather than peripheral venipuncture and use of unhygienic and improper aseptic techniques for sterilising the skin while drawing blood, especially by untrained phlebotomists. Although it is impossible to reach contamination rates of zero or even close to zero, there are several viable methods for reducing contamination. Healthcare personnel who take blood cultures is frequently in a rush, unaware of the necessity of antiseptic preparation contact time and less likely to wait for 1.5 to 2 minutes rather than half a minute before drawing blood. Aseptic preparation of the area where blood is to be drawn should be emphasized. Studies have shown that using iodine tincture has reduced the contamination rate (6, 20). A study reported that, when compared to a typical povidone-iodine preparation, an alcoholic solution of 0.5% chlorhexidine gluconate employed as an antiseptic prior to blood culture resulted in considerably lower contamination rates (21). Also, hand hygiene with alcohol-based sanitizer is recommended, and non-sterile gloves must be worn (22). When blood samples were collected through venipuncture rather than a catheter, a meta-analysis of nine trials found that the contamination rate was reduced (23). A recent study found that culture samples taken through catheter had a higher risk of contamination than the ones acquired via venipuncture (24).

Efforts to reduce BCC rates might considerably reduce not only the length of hospital stays but also the use of unneeded antibiotics, lowering costs and limiting the growing threat of drug resistance. Instead of extracting blood for culture in a hurry, nurses should be taught to focus on stringent sterile rules. Prior to venipuncture, the skin should be thoroughly cleaned, and blood should not be drawn from indwelling devices such as catheters.

CONCLUSION

Monitoring blood culture contamination is an important quality assurance indicator of laboratory performance. Though blood cultures are the gold standard method in the diagnosis of bloodstream infections, there is a high risk of contamination. Contamination of blood samples poses a great challenge to an accurate diagnosis. In the present study, the contamination rate ranged within the normal limits (2.4%). All contaminated blood cultures are received from IPDs. All isolated organisms were from the normal commensal flora or air contamination. There is a need for strict disinfection procedures or policies to be followed with hand hygiene and regular training of HCWs should be implemented. It is always important and recommended to evaluate the contamination rate, so that preventive measures can be taken, and also because it is among the quality indicators which are being monitored by accreditation bodies in microbiology such as NABL and NABH (8).

Conflict of interests: none declared.

Financial support: This work was supported by the institute as a part of quality assurance, hence the resources were the routine procurements in the Department of Microbiology, Central Lab.

TABLE 1.

Total number of blood cultures with true positives, contaminants and negatives

TABLE 2.

Age-wise and sex-wise distribution of contaminants in blood culture

FIGURE 1.

Sex-wise distribution of contaminants in blood culture

TABLE 3.

Ward wise contamination rate

TABLE 4.

Organisms isolated from the blood cultures

FIGURE 2.

Questionnaire-based route cause analysis

Contributor Information

Rathod GUNVANTI, Department of Pathology & Lab Medicine, All India Institute of Medical Sciences (AIIMS), Bibinagar, Telangana, India.

Jyothi Tadi LAKSHMI, Department of Microbiology, All India Institute of Medical Sciences, Bibinagar, India.

Kaliappan ARIYANACHI, Department of Anatomy, All India Institute of Medical Sciences, Bibinagar, India.

Mallamgunta SARANYA, Department of Microbiology, ESIC Medical College & Hospitals, Hyderabad, India.

Sarvam KAMLAKAR, Department of Microbiology, All India Institute of Medical Sciences, Bibinagar, India.

Varatharajan SAKTHIVADIVEL, Department of Medicine, All India Institute of Medical Sciences, Bibinagar, India.

Archana GAUR, Department of Physiology, All India Institute of Medical Sciences, Bibinagar, India.

Shalam Shireen NIKHAT, Department of Microbiology, All India Institute of Medical Sciences, Bibinagar, India.

Triveni SAGAR, Department of Medicine, ESIC Medical College & Hospitals, Hyderabad, India.

Kesavulu CHENNA, Department of Medicine, ESIC Medical College & Hospitals, Hyderabad, India.

Meena S. VIDYA, Department of Anatomy, Tiruvallur Medical College, Tamil Nadu, India

References

- 1.Dargère S, Cormier H, Verdon R. Contaminants in blood cultures: importance, implications, interpretation and prevention. Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2018;24:964–969. doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2018.03.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hall KK, Lyman JA. Updated review of blood culture contamination. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2006;19:788–802. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00062-05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chandrasekar PH, Brown WJ. Clinical issues of blood cultures. Arch Intern Med. 1994;154:841–849. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mylotte JM, Tayara A. Blood cultures: clinical aspects and controversies. Eur J ClinMicrobiol Infect Dis. 2000;19:157–163. doi: 10.1007/s100960050453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wilson ML, Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. Principles and procedures for blood cultures: approved guideline. Wayne, Pa.: Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute; 2007.

- 6.Strand CL, Wajsbort RR, Sturmann K. Effect of iodophor vs iodine tincture skin preparation on blood culture contamination rate. JAMA. 1993;269:1004–1006. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chukwuemeka IK, Samuel Y. Quality assurance in blood culture: A retrospective study of blood culture contamination rate in a tertiary hospital in Nigeria. Niger Med J. 2014;55:201–203. doi: 10.4103/0300-1652.132038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lalezari A, Cohen MJ, Svinik O, et al. A simplified blood culture sampling protocol for reducing contamination and costs: a randomized controlled trial. ClinMicrobiol Infect Dis. 2020;26:470–474. doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2019.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Weinstein MP. Blood culture contamination: persisting problems and partial progress. J Clin Microbiol. 2003;41:2275–2278. doi: 10.1128/JCM.41.6.2275-2278.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hemeg HA, Almutairi AZ, Alharbi NL, et al. Blood culture contamination in a tertiary care hospital of Saudi Arabia. A one-year study. Saudi Med J. 2020;41:508–515. doi: 10.15537/smj.2020.5.25052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cappuccino & Welsh. Microbiology: A Laboratory Manual. Global Edition, 11th Edition | Pearson [Internet]. [cited 2022 Mar 8].

- 12.Alnami AY, Aljasser AA, Almousa RM, et al. Rate of blood culture contamination in a teaching hospital: A single center study. J Taibah Univ Med Sci. 2015;10:432–436. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bowen CM, Coleman T, Cunningham D. Reducing Blood Culture Contaminations in the Emergency Department: It Takes a Team. J Emerg Nurs. 2016;42:306–311. doi: 10.1016/j.jen.2015.10.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Alahmadi YM, Aldeyab MA, McElnay JC, et al. Clinical and economic impact of contaminated blood cultures within the hospital setting. J Hosp Infect. 2011;77:233–236. doi: 10.1016/j.jhin.2010.09.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Doern GV, Carroll KC, Diekema DJ, et al. Practical Guidance for Clinical Microbiology Laboratories: A Comprehensive Update on the Problem of Blood Culture Contamination and a Discussion of Methods for Addressing the Problem. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2019;33:e00009–e00019. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00009-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Weinstein MP, Towns ML, Quartey SM, et al. The clinical significance of positive blood cultures in the 1990s: a prospective comprehensive evaluation of the microbiology, epidemiology, and outcome of bacteremia and fungemia in adults. Clin Infect Dis. 1997;24:584–602. doi: 10.1093/clind/24.4.584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Souvenir D, Anderson DE, Palpant S, et al. Blood cultures positive for coagulase-negative staphylococci: antisepsis, pseudobacteremia, and therapy of patients. J Clin Microbiol. 1998;36:1923–1926. doi: 10.1128/jcm.36.7.1923-1926.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Herwaldt LA, Geiss M, Kao C, Pfaller MA. The positive predictive value of isolating coagulase-negative staphylococci from blood cultures. Clin Infect Dis. 1996;22:14–20. doi: 10.1093/clinids/22.1.14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sharma M, Riederer K, Johnson LB, Khatib R. Molecular analysis of coagulase-negative Staphylococcus isolates from blood cultures: prevalence of genotypic variation and polyclonal bacteremia. Clin Infect Dis. 2001;33:1317–1323. doi: 10.1086/322673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Little JR, Murray PR, Traynor PS, Spitznagel E. A randomized trial of povidone-iodine compared with iodine tincture for venipuncture site disinfection: effects on rates of blood culture contamination. Am J Med. 1999;107:119–125. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(99)00197-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mimoz O, Karim A, Mercat A, et al. Chlorhexidine compared with povidone-iodine as skin preparation before blood culture. A randomized, controlled trial. Ann Intern Med. 1999;131:834–837. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-131-11-199912070-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Garcia RA, Spitzer ED, Beaudry J, et al. Multidisciplinary team review of best practices for collection and handling of blood cultures to determine effective interventions for increasing the yield of true-positive bacteremias, reducing contamination, and eliminating false-positive central line–associated bloodstream infections. Am J Infect Control. 2015;43:1222–1237. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2015.06.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Snyder SR, Favoretto AM, Baetz RA, et al. Effectiveness of practices to reduce blood culture contamination: A Laboratory Medicine Best Practices systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Biochem. 2012;45:999–1011. doi: 10.1016/j.clinbiochem.2012.06.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Self WH, Speroff T, McNaughton CD, et al. Blood Culture Collection through Peripheral Intravenous Catheters Increases the Risk of Specimen Contamination among Adult Emergency Department Patients. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2012;33:524–526. doi: 10.1086/665319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]