Abstract

Objective:The aim of the study was to identify the impact of prenatal lectures in breastfeeding and neonatal care in Romania.

Methods:We distributed a questionnaire to mothers who gave birth at the Bucur Maternity, Bucharest, Romania. A study group was constituted from women who attended prenatal lectures and their answers were compared with those from women who did not have prenatal education.

Results:The study included 122 women. Primiparous women tend to participate in educational lectures to a greater extent than others (p=0.001). Participants in prenatal lectures breastfeed longer than non-participants (.0.001) and they had at least university studies in a higher proportion (94.06%) than non-attenders (52.38%). Women without prenatal lectures live predominantly in rural areas (p=0.003). Most women who attended classes (86.2%) considered that information provided by prenatal lectures was useful. Exclusively breastfeeding was more frequent among participants (47.49%) than non-participants (38.89%).

Conclusion:Primiparity, high level of education and living in urban areas are the main characteristics of female participants in prenatal lectures, who tend to breastfeed longer and ensure exclusive human milk feeding for their babies in a higher proportion than non-participants.

Keywords:breastfeeding, prenatal and postnatal classes, primiparity, education.

INTRODUCTION

Human milk is considered the optimal source of nutrition for infants, with health benefits for themselves and their mothers. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), continue breastfeeding is recommended up to the age of two years (1). Many experts suggest exclusive breastfeeding for the first six months, followed by a diet based on human milk with solid food up to the age of one-year (2). Despite recommendations, many women fall short of those goals (3).

It has been shown that women who intended to breastfeed during pregnancy were more prone to initiate and maintain breastfeeding for a longer period (4). Those mothers tend to be aware of the WHO recommendation to exclusively breastfeed and to disregard the idea that infant formulas were as good as breast milk (5, 6). A higher level of education, non-smoker status, primiparous, Asian or Hispanic, feeling comfortable with breastfeeding in public and not having a plan to return to work are all good predictors of exclusive breastfeeding (5, 7-10). At the opposite side, women who had previous births or previous negative experience with breastfeeding as well as those who were pregnant with twins or who did not attend antenatal classes were less likely to follow breastfeeding recommendations (7, 11). A higher incidence of breastfeeding has been reported when a healthcare provider offered advice to women and answered their questions and concerns (12).

There are only few temporary or permanent contraindications to breastfeeding. Examples of permanent contraindications include the fol- lowing situations: when the infant has classic galactosemia, when the mother is infected with HIV or HTLV I/II, suspected or confirmed with Ebola virus disease and when she is using illicit drugs. Breastfeeding is only temporary contraindicated when the mother has untreated brucellosis, untreated active tuberculosis, an active HSV infection with lesions at the level of the breast, or is taking certain medications (13, 14).

MATERIAL AND METHODS

We performed a prospective study that included women who delivered at “Bucur” Maternity, Bucharest, Romania, and had attended prenatal courses before birth. We designed a self-administered questionnaire which was composed of items about breastfeeding and neonatal care. All women were asked to complete the questionnaire at the end of the prenatal lectures. Data were collected between June 2020 and April 2021. Patients who attended the prenatal course constituted the study group. In parallel we formed a control group comprising pregnant women who had also delivered in our department but had not attended prenatal lectures. The questionnaires were distributed online.

RESULTS

The present study includes 122 women who answered the questionnaires. Among the 122 respondents, 82.79% participated in the prenatal education courses (n=101), and the remaining 17.21% did not attend them (n=21).

Regarding the environment of origin, most respondents (86.89%) lived in urban areas (n=106) and 13.1% in rural areas (n=16).

There was an association between participation in educational lectures and women's origin, because those from rural areas tended to attend courses in a smaller proportion than women who lived in urban areas (÷2=9,100, p=0.003, coefficients Cramer's Phi and V=0.273). Thus, within the group of attenders, 91.09% were from urban areas (n=92) and 8.91% from rural areas (n=9), whereas in the group of non-attenders, 66.67% were from urban areas (n=14) and 33.33% from rural areas (n=7).

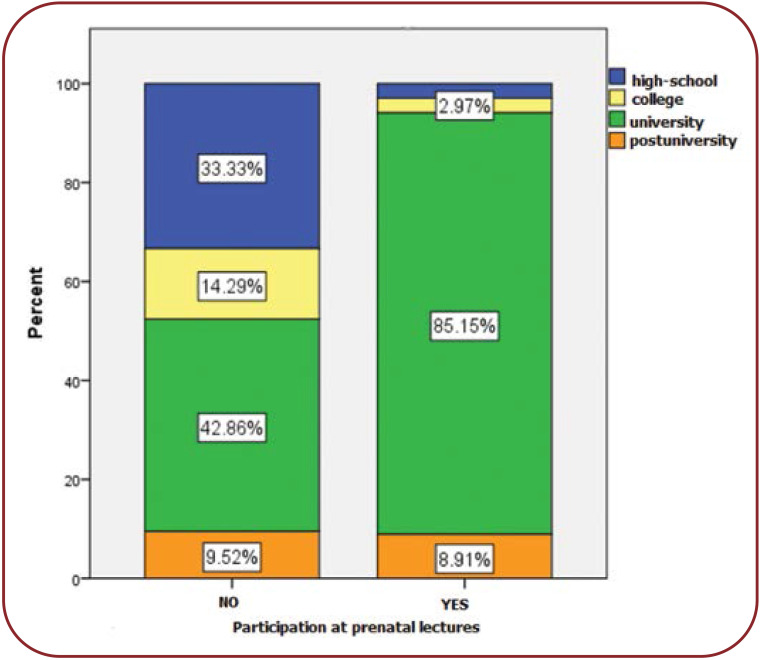

It was noted that the majority of women included in the study had university studies. Most of participants in prenatal lectures had university studies, followed by postgraduate, college and high school education (Figure 1).

Among course attenders, most women were giving birth to their first child, representing 90.10% of all participants (n=91), and only 9.9% had more than one child (n=10).

In the group of women who did not participate in educational lectures, the percentage of first-time mothers was only 61.9% of respondents (n=13), while the remaining 38.10% had more children (n=8).

A Chi-square test was used to check the correlation between participation in pre- and postnatal education courses and each responder’s number of children. There was a statistically significant association between these two parameters, χ²=10.988, p=0.001, while Cramer's Phi and V coefficients (0.300) showed a moderate relationship between the two variables (p=0.001). This statistical test revealed that interest in preand postnatal education courses was higher among first-time mothers compared to those with more children.

Among the 122 women included in the sample, 26.23% (n=32) delivered vaginally, and 73.77% (n=90) by caesarean section. The distribution was similar within the two groups. The most useful or interesting course topics included new-born care, appreciated by 55.7% (n=68) of attenders, followed by breastfeeding [29.5% (n=36)], preparation for childbirth [9% (n=11)], nutrition and hygiene in pregnancy [3.3% (n=4)] and postpartum care [0.8% (n=1)].

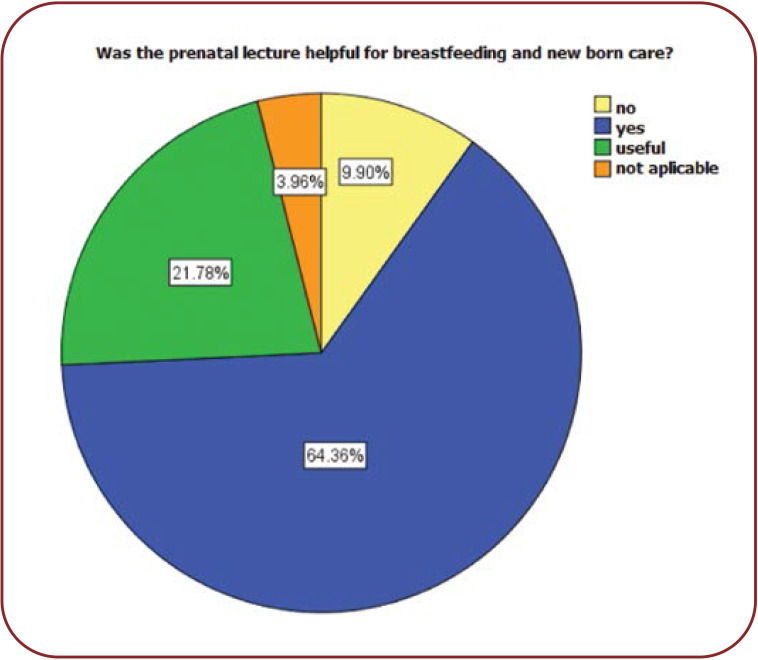

Among attenders at the pre- and postnatal education course, 64.36% (n=65) of them believed that it helped them with breastfeeding, and for 21.8% (n=22) of them it provided useful information regarding breastfeeding. Only 9.9% (n=10) of participants considered that this course was not useful for them in terms of breastfeeding (Figure 2).

The most cited reasons for the course usefulness of breastfeeding included the novelty of information, preferred by 47.37% (n=45) of participants, followed by practical examples [17.89% (n=17)], knowledge about how to prevent unpleasant situations [12.63% (n=12)], receiving information that motivated them [8.42% (n=8)], and convincing the partner to support them [1.1% (n=1)].

It was observed that more than a third, more precisely 36.84% (n=42) of our study participants needed professional support for breastfeeding, 15.8% (n=18) considered that it was not necessary to ask for a professional breastfeeding support, while almost half of participants, that is 47.4% (n=54) stated that they did not need support.

There was no statistically significant association between course attendance and the need for support from professional breastfeeding. However, at the time of completing the questionnaire, 61.16% (n=74) of mothers were still breastfeeding, and 14.88% (n=8) were offering their baby another milk formula in addition to breast milk. Almost a quarter of women (23.97%) (n=29) were no longer breastfeeding at the time of completing the questionnaire. The distributions of answers were statistically similar within the two groups.

In the study group, the following aspects regarding the exclusivity of breastfeeding were observed: none of the women who attended the course stated that they had not breastfeed. Virtually all participants in the course were breastfeeding (to a greater or lesser extent), either exclusively or using a supplement from other sources. In comparison, 22.22% (n=4) of women who did not attend the course stated that they did not breastfeed (at all). A percentage of 47.92% from attenders stated that breastfeeding was exclusively (n=46). From women who did not attend the course, 38.89% breastfeed exclusively (n=7).

A proportion of 20.83% (n=20) of attenders admitted that they used a combination feeding method (breast milk and infant formula). Among mothers who did not attend the course, 11.11% (n=2) supplemented breastfeeding with formula. Among mothers who were no longer breastfeeding, 12.5% (n=12) belonged to the attender group and 5.56% (n=1) to the non-attender one, whereas 18.75% (n=18) of participants in the course and 22.22% (n=4) of those who did not participate had already introduced baby food diversification.

A Chi-square test was used to verify the correlation between participation in pre- and postnatal education courses and breastfeeding. There was a statistically significant association between the two parameters, χ²=23.077, p≤0.001, and Cramer's Phi and V coefficients (0.450) revealed a moderate association between the two variables (p.0.001). This statistical test showed that there were significant differences between the two groups in terms of feeding the baby. On one hand, participants in the course tended to practice breastfeeding to a greater extent (whether it was exclusively administered or mixed), and on the other hand, breastfeeding/absence/inability to breastfeed was more common among non-attenders.

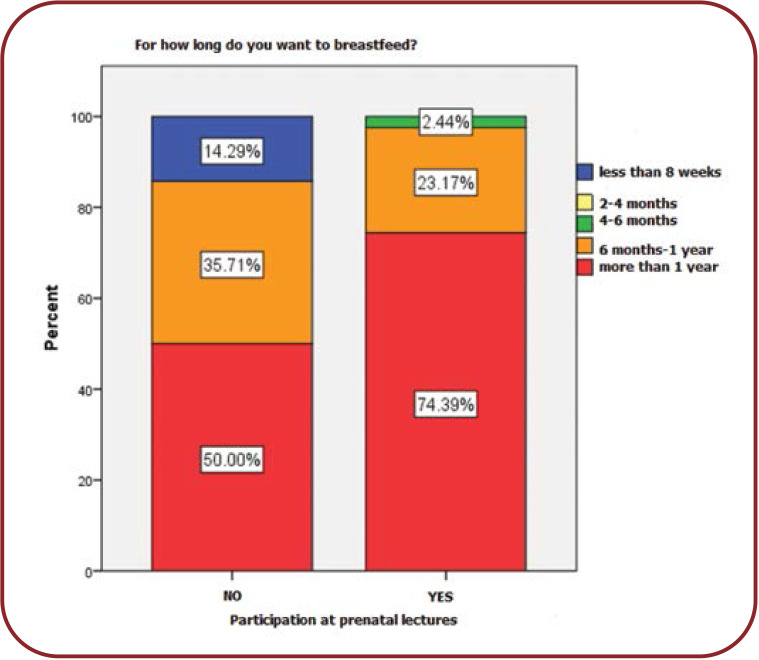

We noted the following aspects regarding babies’ age up to which the mothers wanted to breastfeed: all mothers, regardless of whether they attended the course or not, wished to breastfeed for as long as possible. Thus, 74.39% (n=61) of participants wanted to breastfeed their baby for more than a year, which was also a visible trend among women who did not participate in educational lectures (50%) (n=7). A significant part of all mothers [23.17% (n=19) of the course attenders and 35.71% (n=5) of non-attenders] wanted to breastfeed between six months and one year. Only 2.44% (n=2) of attenders expressed their wish to breastfeed for 4-6 months, which was in fact the shortest breastfeeding period chosen by the course participants. Among mothers who did not attend the course, only 14.29% (n=2) wanted to breastfeed for a maximum of eight weeks. The Chi-square test was used to check the correlation between participation in the course and baby’s age up to which breastfeeding was desired. There was a statistically significant association between these two parameters, χ²=13.813, p=0.003, and Cramer's Phi and V coefficients (0.379) showed a moderate association between the two variables. This statistical test indicated that women who attended the course were more likely to breastfeed for a longer period than the other ones. Also, non-attenders wanted to give up breastfeeding after a shorter period (Figure 3).

DISCUSSION

In our study, the majority of women who attended the course were primiparous. Other studies showed that the intention to breastfeed was correlated with both the initiation and duration of breastfeeding (4). Therefore, primiparous women are more likely to follow breastfeeding recommendations, but mothers who had previous births are less compliant, a possible explanation beeing that their feeling that they had enough experience and knowledge about that topic from their previous pregancies. A systematic review published by Vieira et al and a retrospective cohort study which included women from all hospitals in Ontario, Canada, came to the same conclusions as us (7, 10).

Our data indicated that the level of education and living in urban areas played a decisive role in attending ante- and post-natal courses, and those who attended classes were prone to breastfeed longer than those who did not participate. However, most women from both groups wanted to breastfeed more than one year and only few non-participants opted for breastfeeding less than six months. The relationship between the socio-economic status and compliance to breastfeeding recommendations has been noticed in many scientific studies (7, 15). On the other hand, it is also important to highlight that the inability to breastfeed was more commonly seen among non-attenders, and only this group comprised women who did not breastfeed at all. It has been shown that mother-child relationship was stronger when breastfeeding was practiced due to the skin-to-skin effect (16).

The most commonly reported argument in favour of course attendance in terms of breastfeeding was the novelty of information delivered to participants. It is a well-known fact that science discovers more and more things about human milk, so the need to learn the latest news from a clinician is considered mandatory by many mothers. Although there was no statistically significant difference between course attendance and the need for support from healthcare experts, it has been proved that receiving advice from a medical doctor was associated with a higher incidence of breastfeeding (12). Furthermore, most participants believed that information presented in the pre- and postnatal classes was useful.

An important proportion of participants had also considered important to learn how to prevent unexpected situations and others appreciated the practical examples offered by our lectures. A baby with inappropriate position or unattached to the breast can lead to sore or cracked nipples (17-19). Most participants in the study group had delivered by cesarean section (C-section). Therefore, as surgical incision can lead to pain, which may affect baby’s positioning at the breast, C-section is a risk factor for bad breastfeeding technique and complication such as cracked nipples, this association being confirmed by some studies (20), but rejected by others (21, 22). Nevertheless, we believed it was important to inform the mothers about these possible complications as well as to offer them advice because it has been demonstrated that controlling the pain could allow a correct breastfeeding procedure (23). Nipple trauma can occur in higher rates among primiparous women (21, 22) and those who also use a feeding bottle (18, 24), both characteristics, and especially the first one, being found among our study participants. Consequently, women appreciated the breastfeeding lessons even more when they started to understand the risk factors, unpleasant conditions, and importance of breastfeeding technique and how to deal with them.

Breast engorgement was one of the greatest fears among our subjects. Primary engorgement usually occurs between 3-5 days after delivery due to interstitial edema and decreased level of progesterone (25). When the baby grows up and is no longer fed so frequently for as much diversification with solid food had started, secondary breast engorgement can develop, leading to hard, tight, and painful sensations at the level of the breasts, and this may be the reason why non-attenders tend to abandon breastfeeding earlier. Both pharmacological (enzyme therapy, oxytocin, anti-inflammatory agents) and non-pharmacological (acupuncture, cold packs, ultrasounds, cabbage leaves) treatments have been considered useful for the treatment of engorgement (26-28).

Because many of our subjects had a cesarean delivery, it is important to note that a C-section is correlated with a higher chance of delayed onset of lactogenesis (29, 30). This aspect is important to be known by both the doctor and patient, especially because the mother may experience a lot of distress and anxiety during the peri- and postnatal periods. Therefore, in our program we tried to prevent future worries of mothers who were eligible to cesarean delivery, and we think we succeeded (a significant proportion of subjects stated they felt motivated at the end of lessons). Using both breasts at every feeding and also alternating which breast they start milking can help stimulating the human milk supply. Even more, one study claimed that women who delivered by C-section experienced peak engorgement 1-2 days later than those with vaginal birth (31).

Although food diversification has to start some time, WHO and health experts’ recommendations should be properly followed (1, 2). We noticed that women who attended pre- and postnatal classes had a longer duration of exclusive breastfeeding than non-attenders. Thus, participants were more eligible to adequate breastfeeding.

CONCLUSION

Most women attending pre- and post-natal classes are primiparous and live in urban areas. A higher level of professional education is positively correlated with the interest towards participation in prenatal courses. We found no link between class attendance and the way of birth. Inability to breastfeed is more common among non-attenders. Participants tend to breastfeed their babies longer and also exclusively in a higher proportion than non-participants. Breastfeeding mixed with infant formulas had been more frequently used by women who attended the classes. Most of the women believed it was useful to attend prenatal lectures and they felt that the information provided by us helped them to breastfeed adequately. They mostly appreciated the novelty of information and practical examples.

Conflict of interests: none declared

Financial support: none declared

Informed consent: All participants gave their consent for study participation.

FIGURE 1.

Patients’ distribution based on their last studies

FIGURE 2.

Patients’ distribution based on usefulness of prenatal lectures

FIGURE 3.

Patient’s distribution based on their intention to breastfeed

Contributor Information

Anca Maria BALASOIU, PhD, IOSUD Department, “Carol Davila” University of Medicine and Pharmacy,Bucharest, Romania.

Mihai-Daniel DINU, “Carol Davila” University of Medicine and Pharmacy, Bucharest, Romania.

Gabriel-Petre GORECKI, “Titu Maiorescu” University of Medicine, Bucharest, Romania; Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, “St John” Hospital, “Bucur” Maternity,Bucharest, Romania.

Romina-Marina SIMA, “Carol Davila” University of Medicine and Pharmacy, Bucharest, Romania; Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, “St John” Hospital, “Bucur” Maternity,Bucharest, Romania.

Liana PLES, “Carol Davila” University of Medicine and Pharmacy, Bucharest, Romania; Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, “St John” Hospital, “Bucur” Maternity,Bucharest, Romania.

References

- 1.Marks EJ, Grant CC, de Castro TG, et al. Agreement between Future Parents on Infant Feeding Intentions and Its Association with Breastfeeding Duration: Results from the Growing Up in New Zealand Cohort Study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2018;15 doi: 10.3390/ijerph15061230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stuebe AM, Bonuck K. What predicts intent to breastfeed exclusively? Breastfeeding knowledge, attitudes, and beliefs in a diverse urban population. Breastfeed Med. 2011;6:413. doi: 10.1089/bfm.2010.0088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wen LM, Baur LA, Rissel C, et al. Intention to breastfeed and awareness of health recommendations: findings from first-time mothers in southwest Sydney, Australia. Int Breastfeed J. 2009;4:9. doi: 10.1186/1746-4358-4-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vieira TO, Martins CD, Santana GS, et al. [Maternal intention to breastfeed: a systematic review]. Cien Saude Colet. 2016;21:3845. doi: 10.1590/1413-812320152112.17962015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Thomas-Jackson SC, Bentley GE, Keyton K, et al. In-hospital Breastfeeding and Intention to Return to Work Influence Mothers’ Breastfeeding Intentions. J Hum Lact, 2016. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.McKee MD, Zayas LH, Jankowski KB. Breastfeeding intention and practice in an urban minority population: relationship to maternal depressive symptoms and mother–infant closeness. J Reprod Infant Psychol, 2004.

- 10.Lutsiv O, Pullenayegum E, Foster G, et al. Women’s intentions to breastfeed: a population-based cohort study. BJOG. 2013;120:1490. doi: 10.1111/1471-0528.12376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Burns W, Rovnyak V, Friedman C, et al. BAP: Testing of a Breastfeeding History Questionnaire to Identify Mothers at Risk for Postpartum Formula Supplementation. Clinical Lactaction. 2018;9 [Google Scholar]

- 12.Smith LA, Geller NL, Kellams AL, et al. Infant Sleep Location and Breastfeeding Practices in the United States, 2011-2014. Acad Pediatr. 2016;16:540. doi: 10.1016/j.acap.2016.01.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sachs HC, Committee On Drugs. The transfer of drugs and therapeutics into human breast milk: an update on selected topics. Pediatrics. 2013;132:e796. doi: 10.1542/peds.2013-1985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Johnston M, Landers S, Noble L, et al. Breastfeeding and the use of human milk. Pediatrics. 2012;129:e827. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-3552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gurka KK, Hornsby PP, Drake E, et al. Exploring intended infant feeding decisions among low-income women. Breastfeed Med. 2014;9:377. doi: 10.1089/bfm.2014.0013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Safari K, Saeed AA, Hasan SS, et al. The effect of mother and newborn early skin-to-skin contact on initiation of breastfeeding, newborn temperature and duration of third stage of labor. Int. Breastfeed J. 2018;13:32. doi: 10.1186/s13006-018-0174-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cadwell K, Turner-Maffei C, Blair A, et al. Pain reduction and treatment of sore nipples in nursing mothers. J Perinat Educ. 2004;13:29–35. doi: 10.1624/105812404X109375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Centuori S, Burmaz T, Ronfani L et al. Nipple care, sore nipples, and breastfeeding: a randomized trial. J Hum Lact. 1999;15:125–130. doi: 10.1177/089033449901500210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Morland-Schultz K, Pamela D, Hill PD. Prevention of and therapies for nipple pain: a systematic review. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs. 2005;34:428–437. doi: 10.1177/0884217505276056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Peres JAT. Uso da lisozima na fissura da mama puerperal. J Bras Ginecol. 1980;90:317–319. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Coca KP, Abrão ACFV. Avaliação do efeito da lanolina na cicatrização dos traumas mamilares. Acta Paul Enferm. 2008;21:11–16. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shimoda GT, Silva IA, Santos JLF. Características, frequência e fatores presentes na ocorrência de lesão de mamilos em nutrizes. Rev Bras Enferm. 2005;58:529–534. doi: 10.1590/s0034-71672005000500006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Franz KB, Kalmen BA. Breastfeeding works for cesareans too. RN. 1979;42:39–47. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.França MCT, Giugliani ERJ, Oliveira LD, et al. Bottle feeding during the first month of life: determinants and effect on breastfeeding technique. Rev Saude Publica. 2008;42:607–614. doi: 10.1590/s0034-89102008005000028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Murata T, Hanzawa M, Nomura Y. The clinical effects of “protease complex” on postpartum breast engorgement. J Jpn Obstet Gynecol Soc. 1965;12:139–147. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wong B, Koh S, Hegney D, et al. The effectiveness of cabbage leaf application (treatment) on pain and hardness in breast engorgement and its effect on the duration of breastfeeding. JBI Libr Syst Rev. 2012;10:1185–1213. doi: 10.11124/01938924-201210200-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mangesi L, Dowswell T. Treatments for breast engorgement during lactation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 29.Scott J, Binns C, Oddy W. Predictors of delayed onset of lactation. Matern Child Nutr. 2007;3:186–193. doi: 10.1111/j.1740-8709.2007.00096.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dewey KG, Nommsen-Rivers LA, Heinig MJ, et al. Risk factors for suboptimal infant breastfeeding behavior, delayed onset of lactation, and excess neonatal weight loss. Pediatrics. 2003;112:607–619. doi: 10.1542/peds.112.3.607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]