Abstract

Riparian vegetation is frequently exposed to abiotic stress, which generates reactive oxygen species (ROS) caused by strong differences in a river’s hydrological conditions. Among different ROS, hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) is relatively steady and can be measured appropriately. Thus, the quantification of plant H2O2 can be used as a stress indicator for riparian vegetation management. The current study examines the spatial distribution of plants by riparian vegetation communities across the elevation gradient of riparian zones through quantification of environmental stress using foliar H2O2 concentration. The trees Salix spp., Robinia pseudoacacia, Ailanthus altissima with Juglans mandshurica, and the herbs Phragmites australis, Phragmites japonica, and Miscanthus sacchariflorus were selected for this study. Leaf tissues were collected to analyze H2O2 concentration, meanwhile riparian soil was sampled to measure total nitrogen (TN), total phosphorus (TP), and moisture content. The H2O2 concentration of tree species increased with higher soil moisture content, which was negatively correlated for Salix and herb spp., in which H2O2 concentration always decreased with high soil moisture. In this study, we found a unique significant interaction between soil moisture content and H2O2 concentration, both positively or negatively correlated relationships, when compared with other parameters, such as TN or TP concentrations or TN: TP in riparian soil. The species-specific distribution zones can be explained by the H2O2 concentration in the plant for gravelly and sandy channels on a theoretical range of soil moisture. Each species’ H2O2 concentration was estimated through derived equations and is directly related to an elevation above the channel. The comparison with the observed distribution of plant elevations in the field indicated that all species showed a spatial distribution that acts as species-specific elevations where H2O2 concentrations stayed below 40 μmol/gFW. Hence, the present study suggests that foliar H2O2 concentration can be a useful benchmark for the distribution potentiality of riparian vegetation.

Subject terms: Plant sciences, Plant ecology

Introduction

Riparian vegetation is naturally adapted to abiotic conditions characterized by fluctuating water, sediment, and nutrients1. Riparian plants are diverse in species, structure, and regeneration strategies2,3. Therefore, riparian habitats are regarded as biodiversity corridors for restoration4–7, providing an ecotone between the terrestrial and aquatic ecosystems8,9. Despite the importance of riparian vegetation, riparian degradation often occurs due to various natural disturbances and human activities reducing species diversity10,11. This degradation affects the composition and the plant community structure12. The magnitude, frequency, and duration of flood events have a distinct impact on the creation of the riparian environment. This impact occurs through inundation frequency, level, duration13–17, and flow velocity during the inundated period, driving erosion in other fluvial landforms and deposition of the transported sediment17–19. The sediment moisture content of riparian zones is associated with the stratigraphy of alluvium, groundwater, hyporheic flows20, and the position in the flood or plain corridor21. However, it generally decreases with elevation, depending on the sediment particle size22. These conditions help a riparian species to grow at the elevation of its preferred riparian soil moisture zone23. Due to frequent flood disturbances the sediment accumulations cannot develop properly. As a result, its nutrient level may decrease24,25. The sediment nutrient level may also determine which species can distribute at specific zones15,26,27. The sediment nutrient level in riparian soil, especially TN or TP concentration, can filter and alter its biogeochemistry28–31. For instance, wetland plants take up 16–75% of TN32,33.

The species distribution depends on previously experienced abiotic stresses. However, when subjected to flood disturbance, river habitat conditions change frequently and often suddenly, which is related to the source of deposited sediment and fluvial dynamics. Therefore, it is difficult to evaluate the spatial distribution of each species. There may be an effect with the presence and abundance of dominent factors in preference to promote or inhibit under these complex and constantly changing stressful environments. Causal observation of plant traits, such as growth rate and biomass, commonly used in vegetation monitoring34–36, are not necessarily appropriate evaluation methods. The traits may have been developed under different abiotic conditions than the ones at the monitoring time. Thus, false correlations with the prevailing abiotic conditions may occur. Therefore, an immediate monitoring system is needed to gain information on the possible suitable conditions that can explain the spatial distribution of each species.

Living organisms and biological systems play a significant role against stress to prevent or repair damage. When plants are subjected to environmental stress through metabolic and physiological adjustments, ROS is generated in different organelles depending on the stressor types (e.g., anoxia, drought)37,38. Some ROS is scavenged relatively quickly by antioxidants, and the homogeneity of ROS in tissues is maintained by balancing the ROS and antioxidants. The balance flips over when oxidative stress surpasses the scavenging capacity of the antioxidants39. During exposure to different types of environmental stressors, H2O2 is generated38,40. The H2O2 in plant tissues is relatively stable and can easily be measured41,42. H2O2 measurement is suitable with minimum losses compared with other ROS, such as the superoxide radical (O2·−) and the hydroxyl radical (OH·−). H2O2 has been extensively used to quantify ROS damage or stress levels in many plant studies. Therefore, H2O2 can be used as an indicator of the physiological status of plants and to monitor the response of plants against the intensity of environmental stress43–46. The application of stress response biomarkers, such as H2O2 content in plant tissues using an empirical model, could be an efficient tool in the context of habitat suitability, too. It is necessary to determine the relationship between H2O2 concentration and species-specific abiotic conditions of its habitat to apply this H2O2 indicator in practice47,48.

The main objective of this study is to empirically determine the relationships between species-specific habitat conditions and the H2O2 concentration in riparian plant leaves to understand the feasible H2O2 level for the species to grow, in order to explore the conditions as an index of plant distribution.

Results

Edaphic condition of the riparian zone

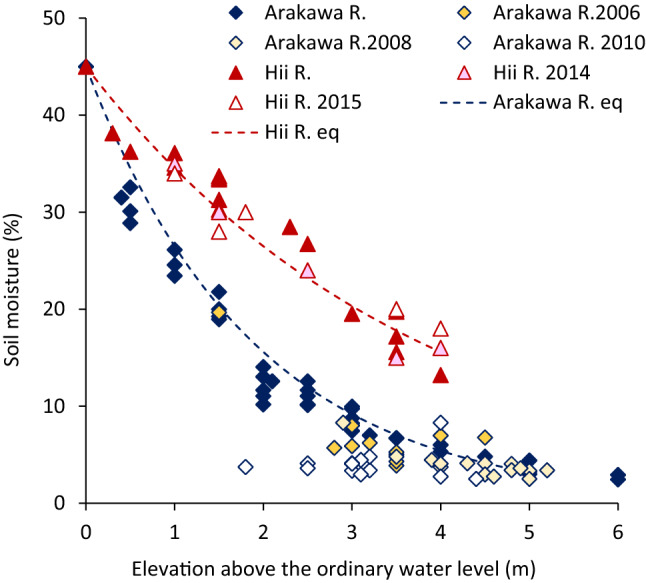

The soil moisture content gradually decreased with increased elevation away from the channel at both the Arakawa River and Hii River sites (r = −0.90, p < 0.01 for the Arakawa River and r = −0.98, p < 0.01 for the Hii River) (Fig. 1). The distributions were empirically given as follows:

Figure 1.

Relationship between elevation above ordinary water level and soil moisture. Data are from this study and previous studies from 2006 to 201522,30,56,66.

For the Arakawa River (gravelly) site (r = 0.99):

| 1 |

For the Hii River (sandy) site (r = 0.99):

| 2 |

where elevation is given in meters above the ordinary water level.

No significant difference was observed in the deviation from these curves between the previously observed results in other studies and the present study (Arakawa River, r = 0.91, p < 10−7 for 2006, r = 0.89, p < 10−7 for 2008, and r = 0.78, < 10−7 for 2010; Hii River, r = 0.99, p < 0.01 for 2014 and r = 0.98, p < 0.01 for 2015)26,49–53. For any given elevation, soil moisture is always higher in the Hii River, owing to the smaller particle size of the riparian soil.

Unlike soil moisture content, the sampled riparian soil TN and TP concentrations did not show a specific trend with respect to surface elevation (Arakawa River, r = 0.4, p = 0.12 for TN and r = 0.35, p = 0.18 for TP; Hii River, r = −0.16, p = 0.6, for TN and r = 0.33, p = 0.2 for TP). The average riparian soil TN concentration at the Arakawa River site was lower than that at the Hii River. At the Arakawa River site, soil TN values ranged between approximately 0.1% and 0.2%, regardless of elevation, whereas the values distributed widely between 0.1 and 0.4% at the Hii River site. These high values can be caused by the smaller particle size of the riparian soil at the Hii River. No significant difference was observed from the previous studies17,26,49–53.

Riparian soil TP was relatively similar in both rivers, ranging between 0.01 and 0.05%. The TN: TP ratio ranged from 1 to 4 at both river sites54.

Species-specific distributional elevation and H2O2 concentration

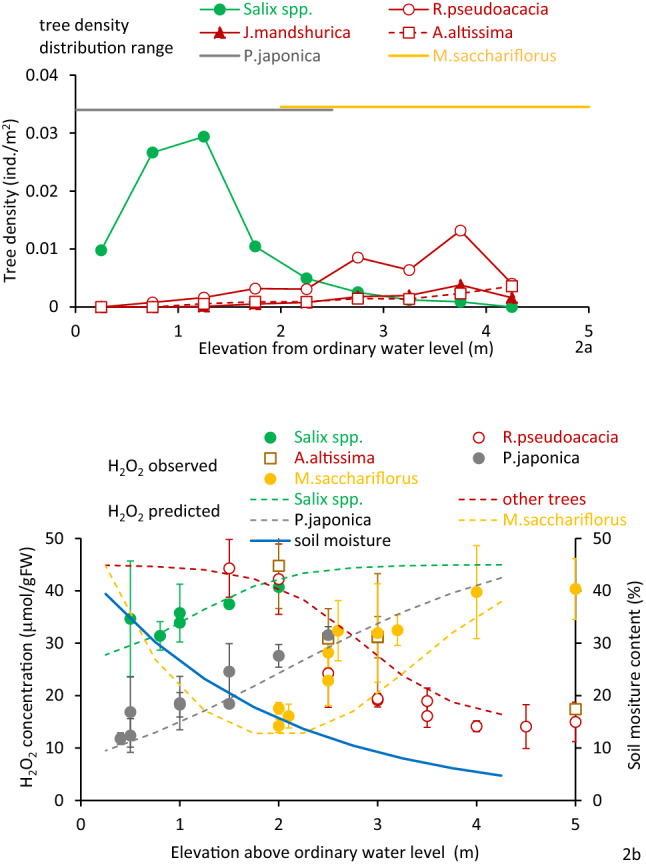

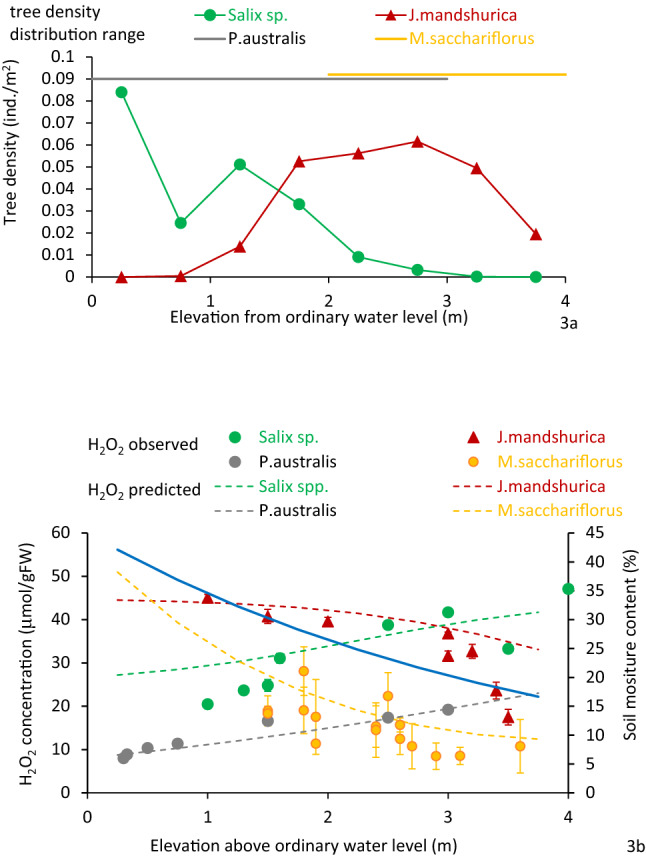

The elevation ranges, leaf H2O2 concentration of target species, and leaf H2O2 concentration compared with the soil moisture distribution are shown in Figs. 2 and 3. Salix spp. were distributed at elevations lower than 2.5 m from the ordinary water level at both river sites, while other tree species were distributed from 2.0 m upwards. For herbs, Phragmites spp. were primarily located at elevations lower than 2.5 m from the ordinary water level, while M. sacchariflorus thrived from 1.5 m upwards.

Figure 2.

(a) Tree density and herb colonies at the Arakawa River site elevations of entire observed area. (b) Soil moisture and H2O2 concentration of samples and simulated results from Eqs. (3) to (6) distributions are also shown. Vertical bars in (b) are standard deviations.

Figure 3.

(a) Tree density and herb colonies at different elevations at the Hii River site of entire observe area. (b) Soil moisture and H2O2 concentration of samples and simulated results from Eq. (3) to (6) distribution are also shown. Vertical bars in (b) are standard deviations.

Foliar H2O2 concentration with respect to soil moisture content

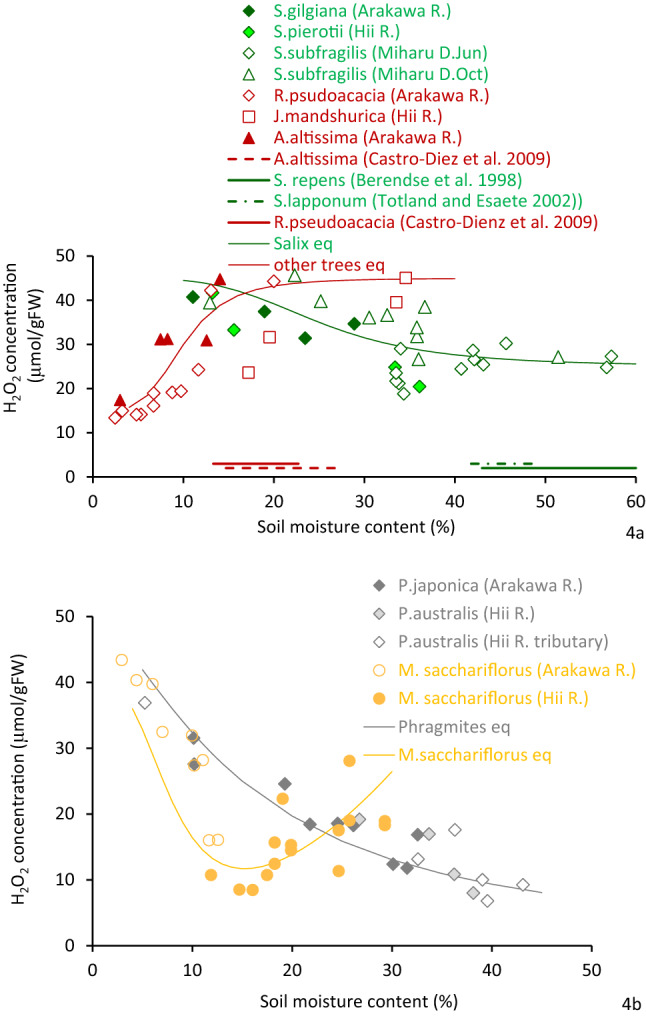

Figure 4a displays the relation between soil moisture content and foliar H2O2 concentration of trees. The figure includes the foliar H2O2 values of S. subfragilis at the Miharu Reservoir44 and the soil moisture range of other reports55,56 for comparison. The Salix species localized generally at higher soil moisture sites than other species57–61. Regardless of rivers and the reservoir site, the foliar H2O2 concentration of all Salix species had a significant decreasing trend with increasing soil moisture content (r = −0.89, p < 0.01 for S. pierotii; r = −0.92, p < 0.1 for S. gilgiana; r = −0.5, p < 0.1 for S. subfragilis). This continued until the soil moisture content reached 35%, keeping the nearly constant value with higher soil moisture content. Thus, the lowest leaf H2O2 concentration (20 µmol/gFW) was recorded at higher than 35% soil moisture content.

Figure 4.

Relationship between soil moisture and leaf H2O2 for (a) different tree species and (b) herbaceous species. Reported soil moisture contents are added (Castro-Diez et al.55; Berendse et al.56; Totland and Esaete57).

Other tree species exhibited positive correlations between soil moisture content and H2O2 concentration (r = 0.66, p < 0.01). The value of H2O2 concentration (approximately 15 µmol/gFW) was lowest at around 5% soil moisture content (the driest condition), then rose with increasing soil moisture until approximately 20–30%, where it attained about 40 µmol/gFW.

Foliar H2O2 concentration of herbaceous species concerning soil moisture content is presented in Fig. 4b. Regardless of sites, similar species-specific trends were observed. M. sacchariflorus had a higher H2O2 concentration at low soil moisture conditions, which decreased with increasing soil moisture until 15% (r = −0.94, p < 0.001). It slightly increased again with higher moisture content. Phragmites spp. showed a uniquely decreasing trend with soil moisture content (r = −0.84, p < 0.001). Overall, there was a negative correlation between herb species and soil moisture content (r = −0.80, p < 10−5).

Foliar H2O2 concentration with respect to other factors

TN and TP contents of plant biomass have organ-specific differences. Plant’s N: P ratios < 10 and > 20 often (not always) correspond to N- and P-limited biomass production in short term periods respectively, although it can vary in the long term62,63. The TN contents of plant biomass were approximately 0.9%, 0.4%, and 2.1% of roots, stems, and leaves of Salix spp., respectively, and 1.3%, 0.6%, 3.0% for R. pseudoacacia. TP contents were 0.1%, 0.01%, 0.12% for Salix spp. and 0.05%, 0.12%, and 0.07% for R. pseudoacacia. For herbs, whole-plant values were 1.9 ± 0.25% for TN and 0.19 ± 0.03% for TP. The nitrogen and phosphorus ratio of plant biomass’s range was 10 to 30. This was much larger than the nitrogen and phosphorus ratio of soils, which was 1 to 4. Therefore, compared with phosphorus, nitrogen seems to be more restrictive for plant growth. However, given the correlation between biomass (of P. australis or M. sacchariflorus) and riparian soil, the TN and TP contents were 0.24 ± 0.05 (p = 0.37) for TN and 0.1 ± 0.37 (p = 0.71) for TP (data not shown). There was no correlation between biomass and TN or TP contents in the riparian soil.

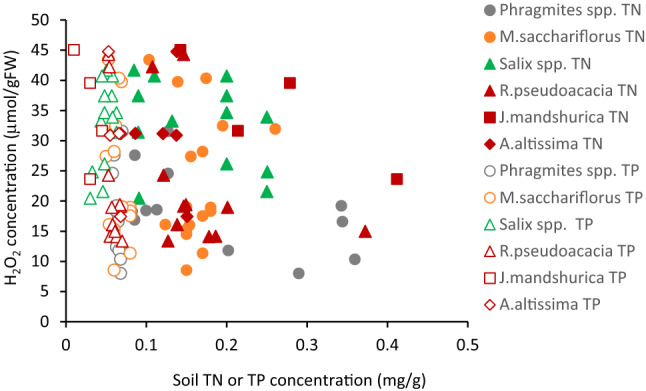

The H2O2 concentration with respect to riparian soil TN or TP contents is shown in Fig. 5. J. mandshurica were distributed at a wide range of TN concentrations, compared with other species, while Salix species’ habitat had relatively low riparian soil TN concentration. However, the H2O2 concentration of all species scattered largely, and there was no significant correlation with riparian soil TN or TP concentrations, and TN: TP (S. gilgiana: r = −0.16, p = 0.73 for TN and H2O2, r = −0.43, p = 0.34 for TP and H2O2, r = −0.06, p = 0.90 for TN: TP and H2O2; S. pierotii: r = −0.31, p = 0.55 for TN and H2O2, r = 0.66, p = 0.15 for TP and H2O2, r = −0.46, p = 0.36 for TN: TP and H2O2; J. mandshurica: r = −0.80, p = 0.1 for TN and H2O2, r = −0.78, p > 0.1 for TP and H2O2, and r = −0.13, p = 0.76 for TN: TP and H2O2; R. pseudoacacia: r = 0.35, p = 0.25 for TN and H2O2, r = −0.56, p = 0.08 for TP and H2O2, r = −0.256, p = 0.45 for TN: TP and H2O2; A. altissima: r = −0.187, p = 0.67 for TN and H2O2, r = −0.71, p = 0.178 for TP and H2O2, r = 0.25, p = 0.690, for TN: TP and H2O2).

Figure 5.

Relationship between leaf H2O2 concentration and soil TN or TP contents.

For herb species, M. sacchariflorus were distributed over a relatively wide range of riparian soil TN concentrations (0.15–0.26%), and its foliar H2O2 concentration varied between 16 and 50 µmol/gFW. P. australis exhibited 12 to 32 µmol/gFW of H2O2 concentrations in 0.10–0.35% of riparian soil TN concentration. P. japonica were distributed near the shoreline of the channel, where TN concentration was relatively low. There was no significant correlation between H2O2 and TN or TP concentrations and TN: TP in riparian soil (P. japonica: r = −0.063, p = 0.871 for TN and H2O2, r = −0.497, p = 0.174 for TP and H2O2, r = 0.041, p = 0.917 for TN: TP and H2O2; P. australis: r = 0.454, p = 0.546 for TN and H2O2, r = −0.754, p = 0.246 for TP and H2O2, r = 0.748, p = 0.246 for TN: TP and H2O2; M. sacchariflorus: r = 0.044, p = 0.866 for TN and H2O2, r = −0.241, p = 0.352 for TP and H2O2, r = 0.181, p = 0.486 for TN: TP and H2O2).

The non-linear regression analysis was performed for each species to find out effect of different parameters (soil moisture, H2O2, TN, TP, TN: TP). Salix spp., R. pseudoacacia, A. altissima, and J.mandshurica individually show significant correlation between soil moisture content and H2O2 (p < 0.001, p < 0.001, p = 0.002, and p < 0.05 respectively), whereas no significant results were observed (p = 0.459 for Salix species, p = 0.884 for R. pseudoacacia, p = 0.186 for A.altissima, and p = 0.652 for J.mandshurica) among parameters (soil moisture, TN, TP, and TN:TP). Herb species also exhibit a similar type of significant trend in the nonlinear regression analysis. Phragmites spp. and M. sacchariflorus indicate significant correlation between soil moisture content and H2O2 (p < 0.001 for both species) On the contrary, no significant results were noticed (p = 0.076 for Phragmites spp., and p = 0.138 for M. sacchariflorus) among parameters (soil moisture, TN, TP, and TN:TP).

We cannot find significant trends between H2O2 concentration and riparian soil TN or TP. One of the reasons is because the variation range of TN and TP was too small to affect H2O2 concentration in the observed sites64, indicating the insignificant effect of nutrients on H2O2. However, widely various TN or TP variations may have a possibility to affect H2O2 concentration.

Modeling foliar H2O2 concentration

From the above discussion we can conclude that due to the insignificant impact of nutrients especially TN or TP concentration, the H2O2 concentration in plants is solely related to soil moisture content. The simple empirical equations can be formulated based on the Monod equations. The equations show the fundamental structure as easily explicit and broaden the underlying mechanism of the species.

For tree species:

Salix spp.

| 3 |

(for the range of soil moisture < 60%, r = −0.60, p < 10−4).

Other tree spp. (Juglans mandshurica, Robinia pseudoacacia, Ailanthus altissima):

| 4 |

(for the range of soil moisture < 40%, r = 0.76, p < 10−4).

For herbaceous species:

Phragmites spp.

| 5 |

(for the range of soil moisture < 45%, r = 0.92, p < 10−9).

Miscanthus sacchariflorus:

| 6 |

(for the range of soil moisture < 30%, r = 0.89, p < 10−3);

where soil moisture is given by %.

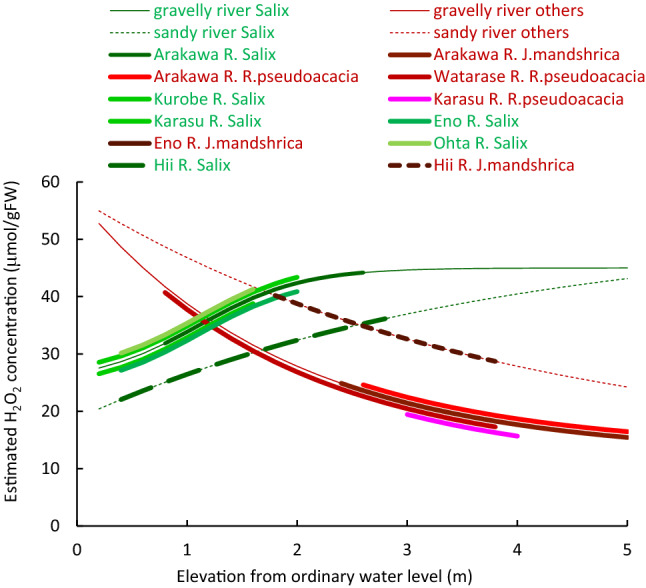

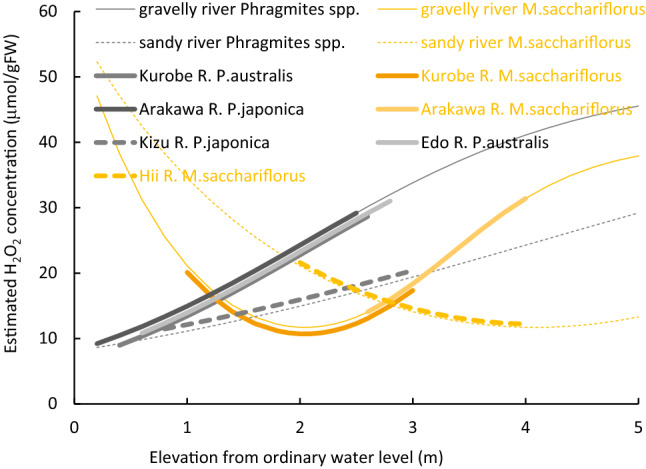

Soil moisture distribution depends on the sediment particle size composition. This relationship was similar for either gravelly or sandy rivers (Fig. 1). For simplicity, soil moisture at the ground surface at the Arakawa River site, Eq. (1), and the Hii River site, Eq. (2), are used as representative of those gravelly rivers and sandy rivers in general. Substituting Eqs. (1) and (2) into (3) to (6), H2O2 concentration for each type of plant is given as a function of the elevation. The estimated H2O2 concentration is presented in Figs. 6 and 7. The locations of observed plants in the present study and other reports are displayed by thick lines in the figures.

Figure 6.

Estimated H2O2 concentration of tree species as a function of elevation from ordinary water level, compared with observed distribution (solid lines: gravelly reaches; dashed lines: sandy reaches; thick lines: observed distribution; green lines: Salix spp.; red lines: other species; Arakawa R., Hii R., Watarase R., Eno R., Ohta R.: this study; Karas R.17; Kurobe27,66).

Figure 7.

Estimated H2O2 concentration of herb species as a function of elevation from ordinary water level, compared with observed distribution (solid lines: gravelly reaches; dashed lines: sandy reaches; thick lines: observed distribution; gray lines: Phragmites spp.; orange lines: M.sacchariflorus; Arakawa R., Hii R., Watarase R., Edo R.: this study; Karas R.51; Kurobe R.27,67).

Both Salix spp. and other tree species are restricted to areas with stress levels less than 40 to 45 μmol/gFW. Therefore, Salix spp. can only distribute starting from the ordinary water level up to 4 m in gravelly rivers and 6 m in sandy rivers. In contrast, other tree species can distribute from 1 m upwards in gravelly rivers and 3 m upwards in sandy rivers. For herbaceous species, all species areas appear where soil moisture results in an H2O2 concentration below 40 μmol/gFW. Phragmites spp. can, therefore, distribute at elevations up to 3 m in gravelly rivers and more than 5 m in sandy rivers. M. sacchariflorus grows at higher elevations and cannot grow below1.5 m above the ordinary water level.

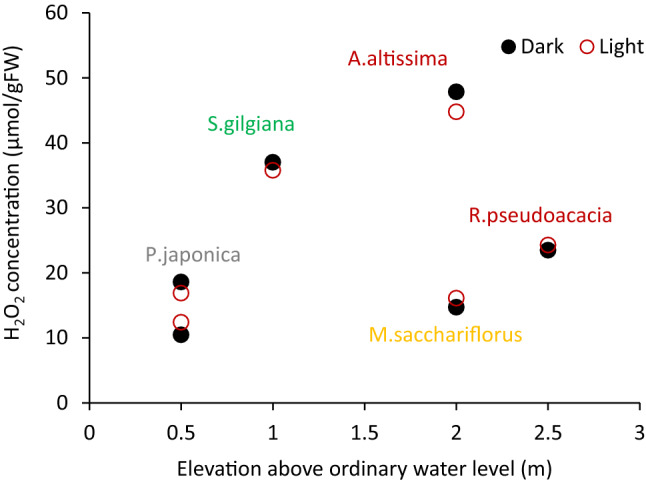

H2O2 is generated under stressed conditions. Thus, the intensity of stresses is correlated to the H2O2 concentration. H2O2 concentrations of light-exposed and dark-adapted samples are shown in Fig. 8. There was no difference in H2O2 concentration between the two treated leaves (p = 0.96) for all tested species, indicating that dark conditions do not cause significant stress.

Figure 8.

H2O2 concentration differences of light-exposed and dark-adapted samples.

To ensure the efficacy of our derived equation, we try to analyze their suitability with the general additive model (GAM). We found that GAM supports our derived equations appropriately among different parameters (elevation, soil moisture content, H2O2, TN, TP, and TN: TP). The H2O2 concentration of tree species increased with higher soil moisture content, yet in terms of Salix spp., the relation is vise-versa. In the case of herb species, Phragmites spp. shows a significant negative correlation with soil moisture content and H2O2, whereas M. sacchariflorus shows a “U” shaped correlation with soil moisture content and H2O2. Considering these situations and derived equations, tree and herb species were divided into four groups in GAM analysis. Twso groups from tree species (Salix spp. and other tree species), and another two groups from herb species (Phragmites spp. and M. sacchariflorus). Salix spp., Phragmites spp., M. sacchariflorus, exhibit significant correlation with soil moisture content and H2O2 among parameters (elevation, soil moisture content, H2O2, TN, TP, and TN: TP) (Tables 1, 2 and 3). In the case of other tree species, significant correlation occurs with H2O2 and soil moisture content shown in Table 4, and elevation shows a strong correlation with H2O2 (Table 4). Supplementary Fig. 1 and Supplementary Fig. 2 represent the observed correlation with confidence intervals.

Table 1.

General additive model for Salix spp. to find out correlation among parameters.

| Parameters | edf | Ref.df | F | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Approximate significance of smooth terms | ||||

| s(Elevation) | 1 | 1 | 0.41 | 0.53735 |

| s(Soil Moisture) | 1 | 1 | 14.230 | < 0.05 |

| s(Soil TN) | 1 | 1 | 0.001 | 0.97290 |

| s(Soil TP) | 1 | 1 | 0.359 | 0.56564 |

| s(Soil TN: TP) | 1 | 1 | 0.005 | 0.94761 |

R-sq.(adj) = 0.766 Deviance explained = 85.6%.

GCV = 20.288 Scale est. = 11.593.

Table 2.

General additive model for Phragmites spp. to observe correlation among parameters.

| Parameters | edf | Ref.df | F | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Approximate significance of smooth terms | ||||

| s(Elevation) | 1 | 1 | 0.422 | 0.5368 |

| s(Soil Moisture) | 1 | 1 | 11.343 | < 0.05 |

| s(Soil TN) | 1 | 1 | 0.054 | 0.8232 |

| s(Soil TP) | 1 | 1 | 0.309 | 0.5958 |

| s(Soil TN: TP) | 1 | 1 | 0.063 | 0.8090 |

R-sq.(adj) = 0.897 Deviance explained = 94%.

GCV = 8.8054 Scale est. = 4.7414.

Table 3.

General additive model for Miscanthus sacchariflorus to find out relationship among parameters.

| Parameters | edf | Ref.df | F | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Approximate significance of smooth terms | ||||

| s(Elevation) | 1 | 1 | 0.001 | 0.9762 |

| s(Soil Moisture) | 1.981 | 1.998 | 6.642 | < 0.05 |

| s(Soil TN) | 1 | 1 | 1.216 | 0.2988 |

| s(Soil TP) | 1.574 | 1.812 | 1.077 | 0.4555 |

| s(Soil TN: TP) | 1.290 | 1.490 | 0.779 | 0.3683 |

R-sq.(adj) = 0.864 Deviance explained = 92.2%.

GCV = 29.554 Scale est. = 15.916.

Table 4.

General additive model for other tree species to evaluate interaction among parameters.

| Parameters | edf | Ref.df | F | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Approximate significance of smooth terms | ||||

| s(Elevation) | 1.980 | 1.998 | 10.618 | < 0.01 |

| s(Soil Moisture) | 1 | 1 | 7.231 | < 0.05 |

| s(Soil TN) | 1 | 1 | 0.639 | 0.431164 |

| s(Soil TP) | 1.606 | 1.844 | 2.273 | 0.078004 |

| s(Soil TN: TP) | 1 | 1 | 0.415 | 0.525103 |

R-sq.(adj) = 0.728 Deviance explained = 78.2%.

GCV = 45.069 Scale est. = 35.012.

Discussion

In Japanese rivers, the volume of sediments has substantially decreased over the last five decades because of the construction of dams upstream, gravel mining, and the reduction of sediment inflow due to the afforestation of the upstream mountainous areas. Therefore, the riparian morphology and sediment characteristics remain relatively stable, even though it is subjected to recurrent large flooding events17,27,65,66. Most of the sampling points were inundated only during a large flooding event, which occurs approximately once every 10 years, with the inundation lasting for a maximum of one week. Therefore, the measured soil moisture content is characteristic of the study site most of the time. The moisture content that the riparian zone reaches is highly affected by sediment particle composition; it is higher at sandy channels than at gravelly channels, as shown in the present study. There were good agreements between the results of previously observed cases (from Eqs. (1) and (2)) and the current study at both river sites.

Several other factors can affect riparian vegetation stress. In the riparian zone of the observed reach, generally nitrogen rather than phosphorus becomes critical for plant growth17,67–69, and it may thus influence the growth of vegetation via soil moisture. However, in the present study, there was no correlation between plant tissue H2O2 concentration and TN along with TP concentration in the riparian soil for the tree and herb species as shown in Fig. 6. Therefore, nitrogen and phosphorus were considered as neither major factors for limiting growth nor regulating species distribution in both rivers. Also, solar radiation did not affect the H2O2 concentration as expressed in Fig. 5. The last major flooding was more than two years ago, and no erosion or deposition trace was observed on the soil surface26. Thus, mechanical disturbances on the ground surface during floods likely did not affect the distribution of plants. Therefore, soil moisture seems to be the major component of stress for the plants in this case.

Threshold H2O2 concentration

When a plant is exposed to environmental stress, it generates H2O2 in different organelles. This occurs partly in the scavenging process of various reactive oxygen species and partly directly37,38. However, some H2O2 is scavenged by the antioxidant activities and finally converted to water and oxygen. Under high-stress conditions, plant tissues become damaged and die off due to the high concentration of H2O2. Therefore, there is likely a threshold concentration below which plants do not deteriorate or die47,48. In the present study, no cases with H2O2 concentrations higher than 40–50 µmol/gFW were observed for tree species. Concentrations above 40 to 50 µmol/gFW of H2O2 seem to be too high to maintain a healthy condition for a tree species. For example, Salix subfragilis in the Miharu Dam highly deteriorated at H2O2 concentration levels ~ 40 to 50 µmol/gFW, which was caused by at least 5 months of low soil moisture44. The low soil moisture condition seems to be a high stressor for Salix spp. At the same time, each species distributed only the elevation where the H2O2 concentration becomes lower than these values.

In the present study, R. pseudoacacia and A. altissima growing on low elevation sites along the Arakawa River had a high H2O2 concentration of 40 to 50 µmol/gFW. These plants may experience greater stress with high soil moisture. All R. pseudoacacia and A. altissima plants intrude and grow at the lower elevation sites (below 1 m, 30% moisture; Fig. 1), had died off over the course of several years26,52,54 without being subjected to flood disturbance. This situation indicates that more than 40–50 μmol/gFW of H2O2 concentration reflects harsh conditions for R. pseudoacacia and A. altissima (Fig. 2a). In contrast, all S. gilgiana growing at elevations above 3 m had disappeared after several years26,52,54. S. gilgiana cannot spread at this elevation, probably because of very low soil moisture content. For herbaceous species, no Phragmites spp., were found at elevations with less than 10% soil moisture in the gravelly channel and 20% in the sandy channel. This corresponds to an H2O2 concentration of 35 μmol/gFW and above. M. sacchariflorus distributed at relatively low soil moisture, with the lowest being about 5%, corresponding to higher than 40 μmol/gFW of H2O2 concentration. Although the water potential was not measured in this study, the sediment’s logarithmic scale of suction (pF) was approximately 4 at 10% moisture content69,70. The pF ~ 3 to 4 corresponds to the wilting point and is nearly the critical condition for the continued growth of many herbaceous plants71,72. The 40–50 μmol/gFW of H2O2 concentration obtained for the existing plants seems to be the critical value for survival. The lowest elevation where M. sacchariflorus was found was approximately 1.5 m above the ordinary water level, where the plant had about 30 μmol/gFW of H2O2 concentration. The location seemed close to the lowest elevation for the distribution, although this was not absolutely critical. Thus, the H2O2 concentration of M. sacchariflorus is U-shaped with respect to soil moisture. For other species, Salix spp. and Phragmites spp. were not found in water, and the H2O2 concentration is unknown, and other tree species growing at very low soil moisture conditions were not obtained. However, there is a possibility the H2O2 concentration also has a U-shaped trend.

The threshold condition of H2O2 concentration spans a relatively wide range, from 35 to 50 μmol/gFW species specifically. However, plants begin to die off with H2O2 concentrations higher than the threshold value as was observed in this study. Thus, the threshold condition delineates the habitat conditions where plants can form.

Characteristics of tree species

Salix species usually are dominant at low elevation zones57–61. In the present study, Salix species always developed above the ordinary water level, and no Salix was found in the constantly inundated zone. Salix spp. make use of hydrochory: dispersal of seeds through water, which encroaches onto the shoreline in spring44,58. Therefore, the distribution of Salix spp. seems to reflect the physiological survival of occupied seeds.

For Salix spp., H2O2 concentration decreases accordance with soil moisture content till 40%. This situation indicates low stress in high soil moisture content. Then, it slightly increased with more than 40% soil moisture. The preferable soil moisture of these Salix species appears to be around 40%, which was near saturation. Several experiments indicated that even steady inundation does not lead to high stress as long as oxygen concentration is sufficiently present in the substrate61. Other tree species in the present study provided a relatively unique increasing trend of H2O2 concentration from 5% of soil moisture to higher levels. The soil moisture thus is the major component determining the potential locations for spatial distribution in the riparian zone.

For R. pseudoacacia, the highest photosynthesis rate was reported at 17% soil moisture. It was substantially lower at 8% and 24%73, and the highest reported leaf water potential was at 13% soil moisture, compared to lower soil moisture contents74. These results suggest the species’ preferred specific soil moisture conditions, which is confirmed in the present results (Figs. 2a and 3a). The soil moisture content at the root zone of trees was not measured in the present study. However, it can be derived from the soil moisture distribution in Fig. 1. The soil moisture at the deepest root zone (i.e., 4 m above the ordinary water surface and 2.5 m below the ground surface) was 16%, although the surface soil moisture content was ~ 5%52. This species does not seem to prefer a high moisture level, although it is typically found in riparian zones. Specifically, this species can thrive at higher elevations in the riparian zone54,75. Since this species uses hydrochory like the Salix spp., these results also imply that seeds can reach the preferred elevations only during very high water levels. A. altissima showed a similar trend of H2O2 concentration in response to soil moisture content as found in R. pseudoacacia. The H2O2 concentration level of J. mandshurica was slightly lower than R. pseudoacacia and A. altissima, indicating that this species prefers higher moisture content. Its high buoyancy can be more easily dispersed downstream and captured ashore at the riverside, where the soil moisture content is more congenial to its growth.

Characteristics of herbaceous species

H2O2 concentration in herbaceous species decreased with increasing soil moisture, and this relationship was consistent regardless of species. M. sacchariflorus is one of the most common species of the riparian zone and is distributed at higher elevations than Phragmites spp. However, the H2O2 concentration of M. sacchariflorus was as high as 40 μmol/gFW when it grew on soil with approximately 5% moisture content. No distribution was found at higher elevations where the riparian soil has less than the soil moisture content. Phragmites spp., on the other hand, is typically distributed in the lower elevation zone where the soil moisture content is > 10%16. The tissue H2O2 concentration of Phragmites spp. in response to soil moisture content also indicates its preference for higher moisture conditions.

H2O2 concentration as the monitoring system

Riparian plants are subject to various stress factors, and they establish successfully only in areas where stress levels are sufficiently low. The riparian zone is often affected by flood disturbance, which changes the channel topography. However, although the reduction of sediment flux erodes the channel bed, it provides a stable habitat for riparian vegetation65,66. Groundwater level variation takes a longer period than surface water and does not change much during a short period. If the soil moisture distribution is properly maintained with an appropriate period of low flow, regardless of short flood occurrences, the elevations where these species distribute or disappear can be predicted. Measurement of H2O2 can be a method to evaluate the threshold values of certain determining abiotic variables beyond which plants cannot survive. Therefore, their chance of disappearance under these conditions can be forecasted. This method is also more precise than most previous methods based on plant traits and empirical monitoring of their spatial distribution only. It is difficult to understand their preferred habitats by the general condition of their spatial distribution, owing to various types of stresses combined with different intensities and frequencies, and exposure periods10,13,15. Also, it is highly dependent on confounding factors like timing and unusual events. The physiological condition of each species determines their unique distribution, excluding physical mortality.

Conclusion

Riparian vegetation encounters different environmental stresses. The findings of this study demonstrate that the spatial distribution of different species in a riparian zone occurs in the context of elevation and soil moisture content. The nutrient level especially TN and TP cannot play significant role due to a small variation of TN and TP concentration. The H2O2 concentration and soil moisture content solely significant in the observed sight. The species-specific distribution zones can be explained by the H2O2 concentration in the plant, which could be a rapid, efficient, and reliable monitoring indicator for vegetation distribution. This study suggests that foliar H2O2 concentration represents the sum of all abiotic stress, and the plant population decreases or cannot survive when it is beyond a critical value.

Methodology

Ethical permission

This study has been approved by the Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, Transport and Tourism, Japan (KasenGijutsuKaihatuH22-2, KasenBikaChousaH18-130, and KasenKikin 271271003).

Study site

Field sampling was conducted in the gravelly sites of the Arakawa River and the sandy sites of the Hii River to compare differences depending on sediment particle size (Fig. 9). Both sites were in the anastomosing section. The Arakawa River is located at the center of Japan, originating from the Chichibu Mountains, flowing over 173 km before draining into Tokyo Bay. The middle section of the river consists of gravel channels typical of Japanese rivers.

Figure 9.

Studied sites at Arakawa River (left) and Hii River (right). Photo credits: Takashi Asaeda.

Sampling was conducted at the Kumagaya Oaso gravel bar, 84 km upstream of the river mouth (36°8′20″ N, 139°20′35″ E). The channel slope was approximately 1/500, and the mean sediment particle size at the sampling site was approximately D50 = 50 mm (D25 = 10 mm, and D75 = 99 mm). The land use in the basin upstream of the sampling site was mostly agriculture and forests. Historically, the riparian zone was occupied by non-vegetated gravel areas until 50 years ago. However, vegetation coverage has gradually increased since then due to river regulation, and now half of the area is covered with woody or herbaceous plant species. More details of the Arakawa sampling site are given in other works of the authors16,17,26,49,52.

The Hii River is located in the Shimane prefecture (Western region of Japan). The river originates from the Chugoku Mountains and flows first into Shinji Lake, then into Naka Lake before draining into the Sea of Japan. It extends about 153 km and drains a basin of about 2017 km2. Eighty percent of the basin area is covered with forest, and the downstream 20% is covered chiefly with rice fields and residential areas. The sampling site was located 14 km upstream of Shinji Lake (35°21′57″ N, 132°47′20″ E), where the channel slope was approximately 1/600, and the bed was entirely composed of sand, D50 = 0.5 mm (D25 = 0.1 mm and D75 = 0.8 mm). This sand had been deposited in the past after iron mining activities upstream.

The riparian zones of both sampling sites are characterized by an upward elevation gradient across the river channel, reaching about 10 m in elevation above the water level in its ordinary flow condition. Groundwater levels have been relatively constant over the years and are tied to the ordinary river water level, at least at the locations where sampling was conducted (The Arakawa Upstream River Management Office, The Izumo River Management Office). Therefore, the riparian topsoil-to-groundwater distance increases as the distance from the river channel increases, while the overall soil moisture level decreases. The sediment’s rhizospheric zone was not saturated with water, and oxygen could penetrate sufficiently except in the zone close to channels76,77. All sampling points were taken on the riparian slopes where the ground surface was moderately covered with vegetation without being completely shaded. Both rivers and riparian zones are subject to intense flooding events. These floods are generally short and are caused by heavy rainfall. Once every 10 years, a major flood occurs. In all cases, however, the water level returns relatively quickly to the normal condition, that is, within less than a week. Except for these events, the water surface level is relatively stable. The soil moisture pattern in the riparian zone, which decreases with elevation from the ordinary water level, has not changed significantly for decades, as evapotranspiration rate balances with precipitation rate in most seasons. These conditions make the selected field sites excellent for studying the relationship between soil moisture and plant stress.

Plant and soil sampling

Sampling was conducted between 10:00 and 14:00 on days with normal, fine weather conditions for the respective sites and more than a month after the most recent flood. In the Arakawa River, the sampling dates were May 5 and June 6, 2017, nearly 2 years after a large flood on September 9, 2015, which submerged sampling points. In the Hii River, sampling dates were October 11–13, 2016, more than 3 years after a large flood. The sampling dates were more than a year later than flooding in the respective rivers in all cases.

Dominant plant species of each site were sampled for this study. The major tree species at the Arakawa site were S. gilgiana, S. subfragilis, R. pseudoacacia, and A. altissima; the major herbaceous species were P. australis, P. japonica, and M. sacchariflorus. At the Hii River site, the major tree species were S. pierotii and J. mandshurica; the major herbaceous species were P. australis and M. sacchariflorus. After surveying 30 km of the riparian zone along the river reaches, three healthy mature individuals per tree species and five well-developed plants per herb species across the elevation gradient of the site were selected and marked.

Selected tree species were 3 to 5 m high, and herb species were about 1.5 to 2 m high. The average root depth of the sampled plants was approximately 2 ± 0.5 m for the tree species and 0.3 ± 0.1 m for the herb species (not sampled, data based on the works)17,26,49,50,52.

Well-grown leaves exposed to solar radiation were carefully sampled by hand. To measure the difference between the solar radiation exposed and dark-adapted samples, additional leaves of the tree species were shaded for 30 min by covering them with a well-ventilated paper bag before sampling. All sampled leaves were sealed in a plastic bag immediately after sampling and stocked in an icebox filled with dry ice (~ − 70 °C) to transport to the laboratory, where samples were frozen at − 80 °C until analysis. It took 8 h at most to transport to the laboratory. The half-life period of H2O2 is about 1.4 to 58 h in water78,79.

The low temperature in the stocked icebox may be a stress to changing H2O2 concentration. However, the temperature declined quickly to below − 10 °C, which is lower than the freezing point of H2O2 as the tissue thickness was less than 1 mm. There was no significant difference in the H2O2 tissue concentrations between the icebox-stocked and immediately analyzed samples (p = 0.76) and between icebox-stocked and non-stocked samples (p = 0.90).

The exact location of all sampled plants was recorded using GPS (Garmin eTrex). Absolute elevations of sampling points and the ordinary water level above the sea level (referenced to Tokyo peil (T.P.)) were obtained from the surveyed sectional map of the Upstream Arakawa River Management Office for the Arakawa river site and the River Management Offices of Izumo for the Hii River site. Soil samples were collected in triplicate from 20 cm below the ground surface from all plant sampling points. The riparian soil was stocked in tightly sealed plastic bags and brought to the laboratory for analysis.

H2O2 assays of plant leaves

In the analytical process of H2O2 concentration, the fresh plant leaves were dry frozen with liquid nitrogen and ground (~ 500 mg) together with an ice-cold 50 mM phosphate buffer (pH 6.0). Polyvinylpyrrolidone (PVP) was added to this extraction to mask the effect of phenolic compounds in the plant materials. The extraction was centrifuged at 5000 rpm at 4 °C for 15 min, and the supernatant was separated. An aliquot of 750 μL extracted supernatant was mixed with 2.5 mL of 0.1% titanium sulfate in 20% (v/v) H2SO480. The mixture was centrifuged at 5000 × g at 20 °C for 15 min. The intensity of the yellow color developed through the reaction was measured spectrophotometrically (UV mini 1210, Shimadzu, Japan) at a wavelength of 410 nm. The absorption at 410 nm includes the effect of other soluble compounds81. Thus, the H2O2 concentration was calculated from the slope of the standard curve obtained from the known H2O2 concentration, which was offset, derived by the intercept absorption rate with zero H2O2 concentration samples82. The results were compared with those of the e-FOX method68, and a suitable correlation (r = 0.971) was obtained. The results were presented as μmol/gFW (Fresh weight).

Soil analyses

The moisture content of the soil samples was determined using the weight loss method. The soil sample was weighed initially and subjected to drying at 105 ºC in an electric oven until a constant weight over time was recorded. Soil moisture content was estimated by the difference between the initial and final weights of the sample. Soil nutrient analyses were conducted only for the fine sediment component (< 128 μm). TN and TP were analyzed separately from the soil in different method. TN in the sediment (oven-dried) was analyzed by a CHN elemental analyzer (Yanako CHN coder MT-5 and Autosampler MTA-3, manufactured by Yanako CO., Ltd., Japan). TP was determined by the molybdenum blue colorimetric method83 after digestion with H2SO4–HClO4 (APHA, 1998)84.

Distribution analysis of target species

In both river sites, all individual trees taller than 1 m were counted per species for the entire gravel bar for the Arakawa River and the area between the dikes of the Hii River along a 2.7 km long stretch85. Compared with the channel morphology obtained by the MLIT River Management Office of each river, the Arakawa Upstream River Management Office, and the Izumo River Management Office, tree densities were obtained for every 0.5 m elevation.

Statistical analysis

Data analyses were carried out using R86 for the dependent variables. Raw data of all variables were checked for normal distribution with the one-sample Kolmogorov–Smirnov test and for homogeneity of the variances with Levene's test. When necessary, arcsine transformation was performed. Results are presented as mean ± SD (n = 3). Data were subjected to a one-way Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) followed by Dunkan’s multiple range test to evaluate the mean difference at a 0.05 significance level. The correlation coefficient (r) and the significance levels (p) were used to evaluate the strength and significance of the parameters estimated. Non-linear regression analysis was performed to view species to species effect among parameters (H2O2, soil moisture content, TN, TP, and TN: TP). A general additive model was performed to find out the efficacy of derived Monod equations among parameters (soil moisture, H2O2, TN, TP, TN: TP, and elevation).

Supplementary Information

Author contributions

T.A. contributed the conceptualization, field work, data analysis, and wrote the manuscript together with other members; M.R. performed the chemical analyses and edited throughout, including figures; L.V.K. collected samples and performed chemical analyses; J.S. reviewed and commented on the manuscript; M.H.R. edited throughout.

Funding

This work was financially supported by the Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (B) (19H02245), (C) (20K04714) and the Fund for the Promotion of Joint International Research (18KK0116) of Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS). JS is grateful to the Antwerp University Research Fund (BOF; Project no. 43171).

Data availability

The authors highly appreciate and state that data is available for everyone in the supplementary file named Raw Data.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-022-17658-2.

References

- 1.Gurnell AM, et al. Vegetation propagule dynamics and fluvial geomorphology. In: Bennett SJ, Simon A, et al., editors. Riparian Vegetation and Fluvial Geomorphology. American Geophysical Union; 2004. pp. 209–211. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Leibowitz SG. Isolated wetlands and their functions: An ecological perspective. Wetlands. 2003;23:517–531. doi: 10.1672/0277-5212(2003)023[0517:IWATFA]2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Maingi JK, Marsh SE. Composition, structure, and regeneration patterns in a gallery forest along the Tana River near Bura, Kenya. For. Ecol. Manag. 2006;236:211–228. doi: 10.1016/j.foreco.2006.09.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Corbacho C, Sánchez JM, Costillo E. Patterns of structural complexity and human disturbance of riparian vegetation in agricultural landscapes of a Mediterranean area. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2003;95:495–507. doi: 10.1016/S0167-8809(02)00218-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Heuner M, et al. Ecosystem engineering by plants on wave-exposed intertidal flats is governed by relationships between effect and response traits. PLoS ONE. 2015;10:e0138086. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0138086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.González E, Lucia MRF, Bourgeois B, Boz B, Nilsson C, Palmer G, Sher AA. Integrative conservation of riparian zones. Biol. Cons. 2017;211:20–29. doi: 10.1016/j.biocon.2016.10.035. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bourgeois B, González E, Vanasse A, Aubin I, Poulin M. Spatial processes structuring riparian plant communities in agroecosystems: Implications for restoration. Ecol. Appl. 2016;26:2103–2115. doi: 10.1890/15-1368.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Malason, G.P. Riparian Landscapes. Cambridge University Press, 12–27 (1993).

- 9.Hrivnal R, et al. Drivers of plant species composition in alder-dominated forests with contasting connectivity. Wetlands Ecol. Manag. 2020;28:137–150. doi: 10.1007/s11273-019-09700-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Villarin LA, Chapin DM, Jones JE. Riparian forest structure and succession in second-growth stands of the central Cascade Mountains, Washington, USA. For. Ecol. Manag. 2009;257:1375–1385. doi: 10.1016/j.foreco.2008.12.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nallaperuma B, Asaeda T. Long-term changes in riparian forest cover under a dam-induced flow regime: the accompanying a numerical modelling perspective. J. Ecohydraul. 2019;4:106–112. doi: 10.1080/24705357.2019.1663714. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mligo C. Diversity and distribution pattern of riparian plant species in the Wami River system, Tanzania. J. Plant Ecol. 2016;10:259–270. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Johansson ME, Nilsson C, Nilsson E. Do rivers function as corridors for plant dispersal? J. Veg. Sci. 1996;7:593–598. doi: 10.2307/3236309. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Casanova MT, Brock MA. How do depth, duration and frequency of flooding influence the establishment of wetland plant communities? Plant Ecol. 2000;147:237–250. doi: 10.1023/A:1009875226637. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pettit NE, Froend RH, Davies PM. Identifying the natural flow regime and the relationship with riparian vegetation for two contrasting western Australian rivers. Regul. Rivers: Res. Manag. 2001;17:201–215. doi: 10.1002/rrr.624. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Asaeda T, Baniya MB, Rashid MH. Effect of floods on the growth of Phragmites japonica on the sediment bar of regulated rivers: A modelling approach. Int. J. River Basin Manag. 2011;9:211–220. doi: 10.1080/15715124.2011.613837. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Asaeda T, Sanjaya K. The effect of the shortage of gravel sediment in midstream river channels on riparian vegetation cover. River Res. Appl. 2017;33:1107–1118. doi: 10.1002/rra.3166. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Steiger J, James M, Gazelle F. Channelization and consequences on floodplain system functioning on the Garonne River, SW France. Regul. Rivers: Res. Manag. 1998;14:13–23. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1099-1646(199801/02)14:1<13::AID-RRR473>3.0.CO;2-B. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Florsheim JL, et al. From deposition to erosion: Spatial and temporal variability of sediment sources, storage, and transport in a small agricultural watershed. Geomorphology. 2011;132:272–286. doi: 10.1016/j.geomorph.2011.04.037. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schilling EK, Li Z, Zhang KY. Groundwater–surface water interaction in the riparian zone of an incised channel, Walnut Creek, Iowa. J. Hydrol. 2006;327:140–150. doi: 10.1016/j.jhydrol.2005.11.014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Timm RK, Wissmar RC, Small JW, Leschine TM, Lucchetti G. A screening procedure for prioritizing riparian management. Environ. Manag. 2004;33(1):151–161. doi: 10.1007/s00267-003-2980-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ma X, Chen Y, Zhu C, Li W. The variation in soil moisture and the appropriate groundwater table for desert riparian forest along the Lower Tarim River. J. Geog. Sci. 2011;21:150–162. doi: 10.1007/s11442-011-0835-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nilsson C, Svedmark M. Basic principles and ecological consequences of changing water regimes: Riparian plant communities. Environ. Manag. 2002;30:468–480. doi: 10.1007/s00267-002-2735-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rashid, M.H. & Asaeda, T. Seasonal variation of carbohydrates in Pueraria montana as affected by soil characteristics in a river floodplain. p. 1–4. In The 36th IAHR World Congress. The Hague, the Netherlands (2015).

- 25.Rashid MH, Uddin MN, Sarkar A, Parveen M, Asaeda T. The growth and nutrient uptake of invasive vines on contrasting riverbank soils. River Res. Appl. 2019;35:749–758. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Asaeda T, Gomes PIA, Sakamoto K, Rashid MH. Tree colonization trends on a sediment bar after a major flood. River Res. Appl. 2011;27:976–984. doi: 10.1002/rra.1372. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Asaeda T, Rashid MH, Sanjaya HLK. Flushing sediment from reservoirs triggers forestation in the downstream reaches. Ecohydrology. 2015;8:426–437. doi: 10.1002/eco.1513. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Brix H. Treatment of wastewater in the Rhizosphere of Wetland plants-the root-zone method. Water Sci. Technol. 1987;19:107–118. doi: 10.2166/wst.1987.0193. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Reed SC, Crites RW, Middlebrooks EJ. Natural Systems for Waste Management and Treatment. McGraw-Hill; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tanner CC. Plants for constructed wetland treatment systems—A comparison of the growth and nutrient uptake of eight emergent species. Ecol. Eng. 1996;7:59–83. doi: 10.1016/0925-8574(95)00066-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Vidon P. Riparian zone management and environmental quality: A multi-contaminant challenge. Hydrol. Process. 2010;24:1532–1535. doi: 10.1002/hyp.7740. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Reddy K, DeBusk W. Nutrient storage capabilities of aquatic and wetland plants. Aquat. Plants Water Treat. Resour. Recov. 1987;66:337–357. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Peterson SB, Teal JM. The role of plants in ecologically engineered wastewater treatment systems. Ecol. Eng. 1996;6:137–148. doi: 10.1016/0925-8574(95)00055-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Barko JW, Gunnison D, Carpenter SR. Sediment interactions with submersed macrophyte growth and community dynamics. Aquat. Bot. 1991;41:41–65. doi: 10.1016/0304-3770(91)90038-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Riis T, Olesen B, Clayton JS, Lambertini C, Brix H, Sorrell BK. Growth and morphology in relation to temperature and light availability during the establishment of three invasive aquatic plant species. Aquat. Bot. 2012;102:56–64. doi: 10.1016/j.aquabot.2012.05.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.O’Hare MT, et al. Plants in aquatic ecosystems: Current trends and future directions. Hydrobiologia. 2017;812:1–11. doi: 10.1007/s10750-017-3190-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mittler R. Oxidative stress, antioxidant and stress tolerance. Trends Plant Sci. 2002;7:405–410. doi: 10.1016/S1360-1385(02)02312-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sharma P, Jha AB, Dubey RS, Pessarakli M. Reactive oxygen species, oxidative damage, and antioxidative defense mechanism in plants under stressful conditions. J. Bot. 2012;2012:26. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dumont S, Rivoal J. Consequences of oxidative stress on plant glycolytic and respiratory metabolism. Front. Plant Sci. 2019;10:166. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2019.00166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Asada K. Production and scavenging of reactive oxygen species in chloroplasts and their functions. Plant Physiol. 2006;141:391–396. doi: 10.1104/pp.106.082040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Satterfield CN, Bonnell AH. Interferences in titanium sulfate method for hydrogen peroxide. Anal. Chem. 1955;27:1174–1175. doi: 10.1021/ac60103a042. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zhou B, Wang J, Guo Z, Tan H, Zhu X. A simple colorimetric method for determination of hydrogen peroxide in plant tissues. Plant Growth Regul. 2006;49:113–118. doi: 10.1007/s10725-006-9000-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Asaeda T, Senavirathna MDHJ, Xia L-P, Barnuevo A. Application of hydrogen peroxide as an environmental stress indicator for vegetation management. Engineering. 2018;4:610–616. doi: 10.1016/j.eng.2018.09.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Asaeda T., Senavirathna, M.D.H.J., Vamsi Krishna, L. & Yoshida, N. Impact of regulated water levels on willows (Salix subfragilis) at a flood-control dam, and the use of hydrogen peroxide as an indicator of environmental stress. Ecol. Eng.127, 96–102 (2019).

- 45.Barnuevo A, Asaeda T. Integrating the ecohysiology and biochemical stress indicators into the paragram of mangerove ecology and a rehabilitation blueprint. PLoS ONE. 2018;13(8):e0202227. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0202227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Asaeda T, Rahman M, Abeynayaka HDL. Hydrogen peroxide can be a plausible biomarker in cyanobacterial bloom treatment. Sci. Rep. 2022;12:12. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-02978-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Asaeda, T., Senavirathna, M.D.H.J., and Vamsi Krishna, L. Evaluation of habitat preferances of invasive macrophte Egeria densa in different channel slopes using hydrogen peroxide as an indicator. Front. Plant Sci.11, Article 422 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 48.Asaeda T, Rashid MH, Schoelynck J. Tissue hydrogen peroxide concentration can explain the invasiveness of aquatic macrophytes: A modeling perspective. Front. Enviro. Sci. 2021;8:516301. doi: 10.3389/fenvs.2020.516301. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Asaeda T, Siong K, Kawashima T, Sakamoto K. Growth of Phragmites japonica on a sandbar of regulated river: Morphological adaptation of the plant to low water and nutrient availability in the substrate. River Res. Appl. 2009;25:874–891. doi: 10.1002/rra.1191. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Karunaratne S, Asaeda T, Yutani K. Growth performance of Phragmites australis in Japan: Influence of geographic gradient. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2003;50:51–66. doi: 10.1016/S0098-8472(02)00114-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Asaeda T, Rajapakse L. Effects of spates of differential magnitudes on a Phragmites japonica population on a sandbar of a frequently disturbed river. River Res. Appl. 2008;24:1310–1324. doi: 10.1002/rra.1128. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Asaeda T, Gomes PIA, Takeda E. Spatial and temporal tree colonization in a midstream sediment bar and the mechanisms governing tree mortality during a flood event. River Res. Appl. 2010;26:960–976. doi: 10.1002/rra.1322. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Vamsi-Krishna L, Rashid MH, Asaeda T. Spatial pattern of foliar hydrogen peroxide concentration and its implication in riparian vegetation management. Landscape Ecol. Eng. 2021;17:471–480. doi: 10.1007/s11355-021-00464-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Asaeda T, Rashid MH, Baker RA. Dynamic modelling of soil nitrogen budget and vegetation colonization in sediment bars of a regulated river. River Res. Appl. 2015;31:470–484. doi: 10.1002/rra.2802. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Castro-Díez P, Fierro-Brunnenmeister N, González-Muñoz N, Gallardo A. Effects of exotic and native tree leaf litter on soil properties of two contrasting sites in the Iberian Peninsula. Plant Soil. 2009;350:179–191. doi: 10.1007/s11104-011-0893-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Berendse F, Lammerts EJ, Olff H. Soil organic matter accumulation and its implications for nitrogen mineralization and plant species composition during succession in coastal dune slacke. Plant Ecol. 1998;137:71–78. doi: 10.1023/A:1008051931963. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Totland Ø, Esaete J. Effects of willow canopies on plant species performance in a low-alpine community. Plant Ecol. 2002;161:157–166. doi: 10.1023/A:1020345632498. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ishikawa S. Seedling growth traits of three salicaceous species under different conditions of soil and water level. Ecol. Rev. 1994;23:1–6. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Sasaki A, Nakatsubo T. Nitrogen and phosphorus economy of the riparian shrub Salix gracilistyla in western Japan. Wetl. Ecol. Manag. 2007;15:165–174. doi: 10.1007/s11273-006-9012-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Hernandez-Leal MS, Suarez-Atilano M, Pinero D, Gonzalez-Rodriguez A. Regional patterns of genetic structure and environmental differentiation in willow populations (Salix humboldtiana Willd.) from Central Mexico. Ecol. Evol. 2019;9:9564–9579. doi: 10.1002/ece3.5475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Nakai A, Yurugi Y, Kisanuki H. Growth responses of Salix gracilistyla cuttings to a range of substrate moisture and oxygen availability. Ecol. Res. 2009;24:1057–1065. doi: 10.1007/s11284-009-0583-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Güsewell S, Koerselman W, Verhoeven JTA. Biomass N: P ratios as indicators of nutrient limitation for plant populations in wetlands. Ecol. Appl. 2003;13:372–384. doi: 10.1890/1051-0761(2003)013[0372:BNRAIO]2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Güsewell S. N:P ratios in terrestrial plants: variation and functional significance. New Phytol. 2004;164:243–266. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2004.01192.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Gomes PIA, Asaeda T. Spatial and temporal heterogeneity of Eragrostis curvula in the downstream flood meadow of a regulated river. Ann. Limnol. Int. J. Lim. 2009;45:181–193. doi: 10.1051/limn/2009015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Liebault F, Piegay H. Causes of 20th century channel narrowing in mountain nd Piedmont Rivers of southwestern France. Earth Surf. Process. Landf. 2002;27:425–444. doi: 10.1002/esp.328. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Lach J, Wyzga B. Chanel incision and flow increase of the Upper Wislok River, southern Poland, subsequent to the reafrorestatopm og ots catchment. Earth Surf. Proc. Land. 2002;27:445–462. doi: 10.1002/esp.329. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Asaeda T, Rashid MH, Kotagiri S, Uchida T. The role of soil characteristics in the succession of two herbaceous lianas in a modified river floodplain. River Res. Appl. 2011;27:591–601. doi: 10.1002/rra.1374. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Kachi N, Hirose T. Limiting nutrients for plant growth in coastal sand dune soils. J. Ecol. 1983;71:937–944. doi: 10.2307/2259603. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Asaeda T, Rashid MH. The impacts of sediment released from dams on downstream sediment bar vegetation. J. Hydrol. 2012;430–431:25–38. doi: 10.1016/j.jhydrol.2012.01.040. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Duttine A, Benedetto HD, Bang DP. Viscous properties of sands and mixtures of sand/clay from hollow cylinder tests. In: Ling H, Callisto L, Leshchinsky D, Koseki J, editors. Soil Stress–Strain Behavior: Measurement, Modeling and Analysis. Springer; 2007. pp. 367–382. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Laio F, Porporato A, Ridolfi L, Rodriguez-Iturbe I. Plants in water-controlled ecosystems: active role in hydrologic processes and response to water stress. Adv. Water Resour. 2001;24:707–723. doi: 10.1016/S0309-1708(01)00005-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Porporato A, Laio F, Ridolfi L, Rodriguez-Iturbe I. Plants in water-controlled ecosystems: Active role in hydrologic processes and response to water stress. Adv. Water Resour. 2001;24:725–744. doi: 10.1016/S0309-1708(01)00006-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Yang, B. Peng, C., Zhu, Q., Zhou, X., Liu, W., Duan, M., Wang, H., Liu, Z., Guo, X. & Wang, M. The effects of persistent drought and waterlogging on the dynamics of nonstructural carbohydrates of Robinia pseudoacacia L. seedlings in Northwest China. For. Ecosyst. 6, article number 23 (2019).

- 74.Li KR, Wang HH, Han G, Wang QJ, Fan J. Effects of brassinolide on the survival, growth and drought resistance of Robinia pseudoacacia seedlings under water-stress. New For. 2007;35:255–266. doi: 10.1007/s11056-007-9075-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Pratt RB, Black RA. Do invasive trees have a hydraulic advantage over native trees? Biol. Invas. 2006;8:1331–1341. doi: 10.1007/s10530-005-0422-y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Guilloy H, González E, Muller E, Hughes FMR, Barsoum N. Abrupt drops in water table level influence the development of Populus nigra and Salix alba seedlings of different ages. Wetlands. 2011;31:1249–1261. doi: 10.1007/s13157-011-0238-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Karrenberg S, Edwards PJ, Kollmann J. The life history of Salicaceae living in the active zone of floodplains. Freshw. Biol. 2002;47:733–748. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2427.2002.00894.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Cooper WJ, Lean DRS. Hydrogen peroxide concentration in a Northern lak: Photochemical formation and diel variability. Environ. Sci. Technol. 1989;23:1425–1428. doi: 10.1021/es00069a017. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 79.EU-RAR European Union, Institute for Health and Consumer protection. Risk Assesment Report (EU-PAR), Hydrogen Peroxide. 2nd Priority List, 38 (2003).

- 80.Jana S, Choudhuri MA. Glycolate metabolism of three submersed aquatic angiosperms during ageing. Aquat. Bot. 1982;12:345–354. doi: 10.1016/0304-3770(82)90026-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Queval G, Hager J, Gakiere B, Noctor G. Why are litreature data for H2O2 contents so variable? A discussion of potential difficulties in the quantitative assay for leaf extracts. J. Exp. Bot. 2008;59:135–146. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erm193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Cheeseman JM. Hydrogen peroxide concentrations in leaves under natural conditions. J. Exp. Bot. 2006;57:2435–2444. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erl004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Murphy J, Riley JP. A modified single solution method for the determination of phosphate in natural waters. Anal. Chim. Acta. 1962;27:31–36. doi: 10.1016/S0003-2670(00)88444-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 84.APHA . Standard Methods for the Examination of Water and Wastewater. 18. America Public Health Association; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 85.Lama GFC, Errico A, Pasquino V, Mizaeri A, Preti F, Chirico GB. Velocity uncernity quatification based on riparian vegetation indices in open channels colonized by Phragmites australis. J. Ecohydraulis. 2022;7:71–76. doi: 10.1080/24705357.2021.1938255. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 86.R Development Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna (http://www.R-project.org). http://www.R-project.org. Accessed 1 July 2011.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The authors highly appreciate and state that data is available for everyone in the supplementary file named Raw Data.