Abstract

Global access to coronavirus vaccines has been extraordinarily unequal and remains an ongoing source of global health insecurities from the evolution of viral variants in the bodies of the unvaccinated. There have nevertheless been at least 3 significant alternatives developed to this disastrous bioethical failure. These alternatives are reviewed in this article in the terms of “vaccine diplomacy,” “vaccine charity,” and “vaccine liberty.” Vaccine diplomacy includes the diverse bilateral deliveries of vaccines organized by the geopolitical considerations of countries strategically seeking various kinds of global and regional advantages in international relations. Vaccine charity centrally involves the humanitarian work of the global health agencies and donor governments that have organized the COVAX program as an antidote to unequal access. Despite their many promises, however, both vaccine diplomacy and vaccine charity have failed to deliver the doses needed to overcome the global vaccination gap. Instead, they have unfortunately served to immunize the global vaccine supply system from more radical demands for a “people’s vaccine,” technological transfer, and compulsory licensing of vaccine intellectual property (IP). These more radical demands represent the third alternative to vaccine access inequalities. As a mix of nongovernmental organization-led and politician-led social justice demands, they are diverse and multifaceted, but together they have been articulated as calls for vaccine liberty. After first describing the realities of vaccine access inequalities, this article compares and contrasts the effectiveness thus far of the 3 alternatives. In doing so, it also provides a critical bioethical framework for reflecting on how the alternatives have come to compete with one another in the context of the vaccine property norms and market structures entrenched in global IP law. The uneven and limited successes of vaccine diplomacy and vaccine charity in delivering vaccines in underserved countries can be reconsidered in this way as compromised successes that not only compete with one another, but that have also worked together to undermine the promise of universal access through vaccine liberty.

Keywords: vaccine apartheid, vaccine diplomacy, vaccine charity, vaccine liberty, structural violence

To help explain the challenges of unequal coronavirus disease 2019 vaccine access, we examine how vaccine diplomacy and vaccine charity have come together to block vaccine liberty in the context of structural market failure and market rule.

Global access to coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID) vaccines has been terribly unequal, raising urgent questions about how to respond to the resulting inequalities in vulnerability and the rising insecurities in protection caused by the evolution of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 in the bodies of the world’s unvaccinated populations [1]. The obstacles to vaccine access have increased death because of the virus in poor countries excluded from the benefits of mass vaccination, while also allowing for new variants of concern such as Omicron to spread from unvaccinated and undervaccinated areas to impose new waves of danger and damage across the whole planet. World Health Organization (WHO) leaders stressed from the early days of the pandemic that nothing short of universal vaccination globally was needed to bring COVID under control. “None of us are safe, until all of us are safe” became their rallying cry, and a clear guide for pursuing global herd immunity through vaccination, testing, and treatment [2]. But, far from rising to this challenge, we have witnessed the vast inequalities in access persist despite impressive breakthroughs in vaccine science, and despite at least 3 international responses that have sought to address the gaps in access. These responses can be broadly categorized and thereby distinguished from one another in the terms of (1) vaccine diplomacy, (2) vaccine charity, and (3) vaccine liberty. It is under these large overarching categories that we here evaluate their overlapping, but, as we will argue, also competing and thus ultimately inadequate efforts thus far to address the access inequalities.

Unfortunately, the dominant forms of vaccine diplomacy in the COVID pandemic have fallen far short of the forms of inter-state collaboration held up by Peter Hotez as the ideal approach to tackling infectious disease with scientists and governments working together across geopolitical divides as they did during the Cold War cases of the smallpox and polio vaccination campaigns [3]. Instead, as we describe, vaccine diplomacy during COVID has been nationalized and geopoliticized; most notably by Russia and China delivering nationally developed vaccines with a view to gaining geopolitical advantage, but also by the United States and other Western states competing to support geopolitical allies [4]. For the most part, however, the United States has led the world’s wealthy countries in the alternative direction of contributing vaccines on a charitable and multilateral basis to the “super” public-private-philanthropic partnership of COVAX [5]. Organized as an international, interagency effort by the Global Alliance for Vaccines and Immunizations (GAVI) in Geneva, but also backed by big philanthropic donors such as the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation (BMGF), and operationally allied in the same way as GAVI and BMGF with for-profit pharmaceutical firms, COVAX is the dominant form of vaccine charity. By February 2022, it had delivered almost 1.25 billion COVID vaccine doses, millions of them free at the point of delivery [6]. In this way, vaccine charity (and at least some vaccine diplomacy) shares something in turn with the call to “free the vaccine” made by advocates of vaccine liberty. These advocates include nongovernmental organizations and civil society movements such as Free the Vaccine, Right to Health Action, Médecins Sans Frontières, PrEP4All and Public Citizen, and the People’s Vaccine Alliance as well as numerous officials and public intellectuals calling for a people’s vaccine [7]. At the heart of their advocacy has been the demand for free access to COVID vaccine intellectual property (IP), including the freeing up of licensing to generic manufacturers through a waiver from the World Trade Organization’s (WTO) TRIPS rules, and the free sharing of vaccine production know how with the countries most in need of access. In clear contrast, therefore, to the geopolitical strings attached in vaccine diplomacy, and in direct opposition to the pharmaceutical firm patenting and profiteering left intact in vaccine charity, vaccine liberty has made the demand for patent-free universal access to life-saving vaccines its first priority. So far, however, this demand has not been met, and the many vaccine scientists in favor of freely sharing their innovations with the world for maximal humanitarian benefit (such as the Oxford University ChAdOx vaccine team that ended up signing onto an exclusive license with Astra Zeneca) have instead seen their IP monopolized by pharmaceutical firms and the profit-making interests of their shareholders [8].

More widely, the failure of the 3 main responses to correct vaccine access inequalities has been interpreted in relation to the global dominance of vaccine property structures and profit-making concerns over demands for reparative justice [9]. This a form of political-economic structural market failure that has itself been explained as a “successful market failure” because it reflects the successful entrenchment of IP patents, trade rules that extend the associated monopoly rights globally, and supporting neoliberal policy regimes and public-private partnerships [5, 10–14]. Building on these explanations, we examine how the 3 leading international responses to the inequalities have themselves come to compete with one another within this wider structural context of vaccine IP enclosure and monopolization. We argue on this basis that, in addition to successful market failure, another important explanation of the failure to universalize access can be found in how the nation-state–managed response of vaccine diplomacy and the public-private-philanthropic response of vaccine charity have effectively come together to foreclose on responses advanced by civil society activists and poor countries in the name of vaccine liberty.

To set the scene for comparing the 3 main responses and examining the ways in which they have interacted competitively, we first outline the problem of vaccine access inequality. Next, we describe the responses of vaccine diplomacy, vaccine charity and vaccine liberty in turn, outlining what each includes, and evaluating what they have each accomplished thus far by way of countering vaccine access inequality. We conclude in this way that, despite its wide global appeal and support, the struggle for vaccine liberty remains outmatched by the interlocking dominance of vaccine diplomacy and vaccine charity.

VACCINE ACCESS INEQUALITY

“The development and approval of safe and effective vaccines less than a year after the emergence of a new virus is a stunning scientific achievement, and a much-needed source of hope…But we now face the real danger that even as vaccines bring hope to some, they become another brick in the wall of inequality between the world’s haves and have-nots” [15].

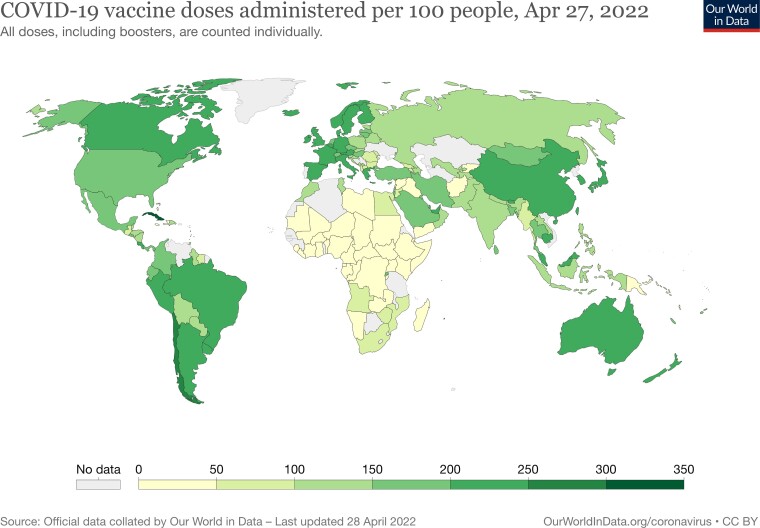

This was how the WHO director sounded the alarm about looming vaccine access inequalities in January 2021, just as wealthy countries were beginning to approve COVID vaccines for widespread use. “I need to be blunt,” he concluded, “the world is on the brink of a catastrophic moral failure – and the price of this failure will be paid with lives and livelihoods in the world’s poorest countries.” A year later, his words proved prescient, and his spatial metaphor of a wall separating the vaccine “haves” from “have-nots” all too telling. Still, in April 2022, much of Africa remained without any population level access at all, and even in the African countries where vaccination has begun the numbers of doses administered per capita remain extremely low (Figure 1). Describing their countries’ experiences of this global divide in access at the United Nations, African leaders were themselves despairing as well as outraged. Samia Suluhu Hassan, President of Tanzania, described the level of vaccine inequity as appalling. “It is truly disheartening to see that whilst most of our countries have inoculated less than 2 per cent of our populace and thus seek more vaccines for our people, other countries are about to roll out the third dose,” she said [16]. And Namibia’s President, Hage Geingob, summed up the state of affairs as being so severe that it amounted to “vaccine apartheid” [16].

Figure 1.

COVID-19 vaccine doses administered per 100 people, 27 April 2022 (all doses, including boosters, are counted individually).

Vaccine apartheid has since gone on to become an antiracist as well as epidemiologically and bioethically accurate representation of the vast global gaps in access to COVID vaccines. It is epidemiologically and bioethically accurate because it describes directly the exclusionary outcomes that the WHO director sought to depict with the spatial metaphor of the wall. Just like the spatial regulations of South African apartheid law, vaccine apartheid cuts whole communities off from access to life-saving biomedicine, reducing their health rights to what social theories of biopower describe as “biological sub-citizenship” [17, 18]. But by also indexing the distinctively racist result of excluding Africans from vaccine access, vaccine apartheid is also an antiracist description of the problem because it directly underlines the continuities of racist double standards and exclusions from the age of empire into the neocolonial present, even as leaders in global health have been redoubled calls for be decolonization [19]. Calling COVID vaccine access inequality “vaccine apartheid” critically underlines in this way how racist forms of coloniality have persisted into a time of pandemicity [20, 21]. However, in contrast to South African apartheid that was explicitly raciological in the political and legal system it used to enforce racist dispossession and disenfranchisement, vaccine apartheid is better understood as a form structural racism that has led to vaccine access inequalities through forms of structural violence [9]. Paul Farmer, a global health leader who did so much with his work to resist and repair the pathological effects of such structural violence, put it well in one of the last papers he published before his untimely death in 2022. Writing with the Harvard bioethicist Alicia Yamin, Farmer described global health in the time of COVID as being “deeply embedded in, and shaped by, interlocking systems of power—patriarchy, racism, coloniality, neoliberalism, and exploitative commerce, among others” [14]. It is precisely within these same interlocking systems of power that we see vaccine diplomacy and vaccine charity interlocking themselves to block vaccine liberty and thereby codetermine the structural violence of vaccine apartheid.

VACCINE DIPLOMACY

With the COVID pandemic intersecting with a new rise in inter-state competition and heightened forms of authoritarian nationalism around the world, we have seen vaccine diplomacy tied much more closely to the pursuit of geopolitical advantage by particular nations competing to deliver nationally branded vaccines while securing profits and so-called “soft-power” influence in the process [4, 22, 23]. Because of the Trump Administration taking a so-called “America First” approach to the vaccines coming out of Operation Warp Speed in the United States, the first movers in this newly nationalistic form of vaccine diplomacy were Russia (with its Sputnik V vaccine produced by the Gamaleya Institute with funding from the Russian Direct Investment Fund) and China (with the vaccines produced and branded by Sinovac, Sinopharm, and CanSino). Subsequently, they were joined by India, the United States, and EU member states with all sorts of flag-branded vaccines being diverted from the multilateral COVAX effort (or earmarked within the COVAX effort) into bilateral vaccine diplomacy of the kind initiated by Russia and China. By this point, the geopolitical imperatives guiding these practices were established. As a result, vaccine diplomacy in the COVID context can be broadly understood to encompass vaccine development and delivery schemes that have been pursued very narrowly in the name of national interest, national-state security and with a view to an economic return on vaccine development investments in pharmaceutical firms chosen as national champions.

In sum and in contrast to the Cold War inter-state collaborations undertaken to vaccinate against smallpox and polio, vaccine diplomacy with COVID vaccines has been both nationalized and geopoliticized. This has led to multiple unaccountable bilateral deals that have further frustrated efforts to lead a transparent and consensual multilateral approach to vaccine distribution by the WHO [15]. It has also undermined any kind of coordinated approach to pharmacovigilance in the recipient countries [24]. Far from the example of scientific internationalism represented by the work on an oral polio vaccine by Albert Sabin, Mikhail Chumakov, and Anatoly Smorodintsev, it has been shaped much more by national branding, national prestige, and narrowly defined national interests [3, 4]. These came to include the America First interests of the Trump administration in the United States, but they were led by the nation-building agendas of China and Russia, or at least the agendas of their leaders. President Xi’s China therefore conducted vaccine diplomacy partly as a “Health Silk Road” augmentation of its larger “Belt and Road Initiative” to develop ties and resource extraction supply chains globally, as well as in response to the damage done to China’s reputation by the initial outbreak of COVID in Wuhan [4]. And Putin’s Russia further escalated the geopoliticization of vaccine diplomacy by even engaging “in efforts to impugn the integrity or safety of Western COVID-19 vaccines through social media and other communications” [24].

The upshot of the geopoliticization and nationalization of COVID vaccine diplomacy is that it has been conducted with little regard for the resulting inequalities in distribution, nor the associated perversities of building-up surpluses in strategically valuable countries even as other countries remained without any reliable supply at all. The whole approach has encouraged yet more stockpiling and hoarding in the name of vaccine nationalism, as well as all sorts of overcharging and disputes over delivery contracts [23]. Ironically, therefore, even as vaccine diplomacy delivered vaccines it also increased vaccine apartheid. In the critical view of César Rodríguez-Garavito, “[t]hose responsible for this apartheid are … the governments of producer countries that have hoarded [vaccines] or used them to practice ‘vaccine diplomacy’ for geopolitical purposes” [25]. In addition, because of its ties to vaccine nationalism and vaccine hoarding, vaccine diplomacy has in turn contributed to the interlocking structural forces that have inhibited the capacity of both vaccine liberty and vaccine charity to correct the resulting inequalities. In relation to the efforts to promote a people’s vaccine for the whole world, vaccine diplomacy has done nothing to advance the sharing of vaccine IP and production know-how. Instead, by delivering vaccines for which national champions hold the patents, it has simply reinforced the global IP order and reduced the urgency of demands for a TRIPS waiver at the WTO. Meanwhile, the bilateralism of COVID vaccine diplomacy has also undercut the vaccine charity of all the multilateral efforts organized out of Geneva. China and Russia both declined initially to donate to COVAX, and the Trump Administration’s America First agenda even led it to start pulling the United States out of the WHO altogether. More generally, the nationalistic race to develop vaccine technology and the associated government investments in national champions set a diplomatic tone that has undermined the global solidarity on which the vision of COVAX originally rested. It is to the many other challenges facing this international public-private-philanthropic partnership that we turn next.

VACCINE CHARITY

COVID vaccine charity has largely been organized under the transnational institutional umbrella of COVAX to make charitable deliveries of vaccines on a multilateral basis. Led by GAVI, COVAX is viewed by its managers as the only viable solution to overcome vaccine access inequalities. “For lower-income funded nations, who would otherwise be unable to afford these vaccines,” GAVI’s Chief Executive Office Seth Berkley insists, “COVAX is quite literally a lifeline and the only viable way in which their citizens will get access to COVID-19 vaccines” [26]. Although the WHO was central to setting up COVAX as the so-called “vaccine pillar” of the Access to COVID-19 Tools Accelerator, the program has evolved in complex ways because of its dependence on philanthropy (especially the influence of the BMGF) as well as donations of both money and surplus vaccines by wealthy countries. It has thereby come to be administered by an extraordinarily hybrid assemblage of agencies led by GAVI and supported by the WHO, but also involving UNICEF, Pan American Health Organization, and the BMGF-supported Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovations. A kind of apotheosis in trends toward treating global health programming as a series of vertically targeted donor-directed investment schemes [27], the resulting multidimensional, multistakeholder, multilateral program has been well-described as a “super public-private partnership” [5]. But its organizational complexities, combined with their byzantine philanthro-capitalist financialization structures, including especially their close coordination with pharmaceutical firms, have led to far from super outcomes [28–30].

Critics have pointed to shortfalls at every stage of the COVAX delivery rollout. In May 2021, Anna Marriot of Oxfam (and colead of the People’s Vaccine Alliance) noted frustratedly that: “Nine people are dying every minute while the vaccine stores of COVAX … lie empty” (quoted in [31]). By June 2021, COVAX had still only distributed 89 million vaccine doses, less than 5% of its 2 billion target [5]. And by fall 2021, numerous representatives of poor country governments were themselves adding their own concrete complaints about entirely inadequate deliveries, including about late arrivals of shipments in which vaccine doses were already past the point of expiration [31, 32]. Over time, the pattern has become one of COVAX overpromising and underdelivering. Whereas the WHO estimated that the world needed about 11 billion COVD vaccine doses to ensure universal vaccination, and although COVAX set a goal of delivering 2.3 billion doses by 2022, by February 2022 the total cumulative number of deliveries by COVAX had still only reached about 1.25 billion, which included many millions of deliveries to high- and middle-income countries and not just to those most in need [6]. It is true that COVAX delivered its first dose in Ghana on 24 February 2021, which was less than 3 months after wealthy countries such as the United Kingdom started mass vaccination campaigns. It is also true that, unlike COVID vaccine diplomacy deliveries, COVAX has subsequently arranged for a large percentage of deliveries that have been free at the point of delivery in poor countries. However, just like vaccine diplomacy, these charitable deliveries have been inadequate in correcting the ongoing vaccine apartheid, limiting access in Africa most especially.

The inadequate response of vaccine charity to vaccine access inequalities was certainly not how the vision of COVAX began. According to Gavin Yammey, a member of the working group convened by GAVI in 2020 to discuss the design of the program, it was instead initially a “beautiful idea, born of solidarity” (Yammey, quoted in [29]). “Unfortunately,” Yammey went on to explain about the failure of the vision, “it didn’t happen. Rich countries behaved worse than anyone’s worst nightmares.” In this insider’s view, we see directly how the vaccine nationalism and vaccine hoarding problems overshadowing vaccine diplomacy also fell devastatingly on vaccine charity. The WHO director general was himself equally critical of how bilateralism came this way to trump multilateralism. “Even as they speak the language of equitable access,” he complained, “some countries and companies continue to prioritize bilateral deals, going around COVAX, driving up prices and attempting to jump to the front of the queue. This is wrong” [15]. But further constricting COVAX was its embeddedness within the wider institutional arrangements of philanthro-capitalist global health and the financialized approaches of the “New Washington Consensus,” of which Ghebreyesus has been much more supportive [5, 33; Stein, 2021]. Rather than challenging the market rules enforcing IP monopolies, these arrangements and approaches focus on using micromarket mechanisms to compensate for the macromarket failure: promoting investments in health in the name of wealth, and working in partnerships with the private sector while reducing government and other public sector agencies to the status of being donors alongside private philanthropies. For these reasons, as Kate Elder from MSF has consistently explained, “COVAX was not set up to succeed” [34]. “It was constructed to work within the current parameters of the pharmaceutical market, where you see how much money you can raise and then see what you can negotiate with industry for it” [34].

Another way to sum up the limitations of vaccine charity is that it has been stuck institutionally between the rock of vaccine nationalism and a soft place of public-private-philanthropic multilateralism. To be sure, along its journey from 2020 to 2022, COVAX has also been buffeted by supply shocks due, for example, to its overreliance on planned shipments from India’s Serum Institute that were diverted to deal with India’s own domestic crisis during the Delta surge. But all this time, its promises have delayed African countries signing orders with pharmaceutical firms and allowed those firms to retain pricing control on their patented vaccine IP. This has kept the most efficacious and expensive vaccines out of reach for most African countries, and meanwhile inoculated the overall vaccine supply system globally from more radical demands for the sharing of vaccine IP and production know-how as global public goods. The outcome of vaccine charity, in other words, whether intended or not, has been to create a kind of interlocking pincer movement with vaccine diplomacy. Structurally, they have come together to forestall calls for vaccine liberty. It is to these calls that we now turn in conclusion.

VACCINE LIBERTY

Like COVAX, the People’s Vaccine Alliance and other activist groups demanding vaccine liberty have themselves worked through multiple forms of multistakeholder and multilateral organization. But far from the heights of Davos, the home of the World Economic Forum, where Seth Berkley first hatched GAVI’s plan for COVAX, the struggle for vaccine liberty is better understood as a grassroots and insurgent movement for social justice; a movement more broadly aligned with the forms of alter-globalization civil society activism seen at the World Social Forum. It includes the activism of nongovernmental organizations such as Médecins Sans Frontières, PrEP4All, Public Citizen, Right to Health Action, and UAEM. And, along with all their direct advocacy and political lobbying, these organizations have engaged in a mix of street protests, symbolic politics, and website information sharing designed to educate the world’s public about their case for vaccine liberty. Additionally, though, the Free the Vaccine campaign and People’s Vaccine Alliance have also been tied from the start to state-led and civil-society supported efforts from poor countries themselves to demand a waiver from the WTO’s TRIPS rules to allow for the generic manufacturing of the best vaccine IP available. There is in all this activist and legal work a remarkable inversion of the normal neoliberal language about free trade. Vaccine liberty, argue its advocates, must involve emancipation from free trade rules precisely to free COVID vaccine IP instead. It is a testament to the power of this emancipatory inversion, and to the effective organizing work of the vaccine liberty movement, that shortly after he came to the White House, President Biden changed the official position of the US administration to support the calls for the TRIPS waiver at the WTO. Similarly significant at a symbolic level have been the high-profile endorsements of vaccine liberty by the UN Secretary General, the Pope, diverse other heads of state, and numerous Nobel laureates, scientists, and celebrities, including, in December 2021, Prince Harry and Meghan Markle, the Duke and Duchess of Sussex.

But so far at least, the important symbolic shifts in global vaccine politics generated by the movement for vaccine liberty have not led to any progress on the TRIPS waiver, and nor have they led to the US government using its considerable legal authority to march in and force vaccine IP sharing by Pfizer and Moderna [9]. This reticence has persisted even with the US government holding patents on some of the component IP of the messenger RNA vaccines, and even despite influential officials in the administration such as David Kessler and Anthony Fauci publicly stating their support for IP sharing to meet the goals of universal global vaccination. Undoubtedly, 1 reason why involves the strong resistance of the pharmaceutical firms themselves, and the powerful governments (including many in the European Union such as Germany, plus the United Kingdom and Switzerland) who see direct ties between pharmaceutical firm profits and national gross domestic product. There is also the ideological resistance of all those who insist that the manufacturing and distribution capacity for generic vaccines does not exist in poor countries, despite good evidence to the contrary [9, 35]. In a related form of “blame-the-victim” argument against vaccine liberty, others even argue that the real problem is instead African vaccine hesitancy; despite good counter arguments by African health leaders about the manageable scope of this challenge as well as its ironic ties to extractivist clinical trials on the continent by some of the same firms restricting access to life-saving IP [36]. However, our review here of the competing responses of vaccine diplomacy and vaccine charity, leads us to conclude that they have interlocked with one another as a particularly persistent and strong structural barrier to vaccine liberty.

Our conclusion, in short, is that every time advances are made in the case for opening up vaccine liberty both geopoliticized vaccine diplomacy and financialized vaccine charity shut the possibilities down. The former systematically reframes the debate in the narrow terms of national interest, whereas the latter presents itself as the only operational international alternative to ongoing vaccine apartheid ([9, 37]). Despite their many differences, both these dominant responses to vaccine access inequalities thereby intersect and interlock in ways that preempt the sorts of alternatives imagined by advocates of vaccine liberty. Along with these advocates, we concur that it does not have to be this way. As many scientific and legal experts have long argued (albeit to much resistance), there are both numerous precedents and generative platforms for biomedical innovation that produces public goods without the privatizing push for patents and paywalls [11, 38–40]. As Hotez has shown with the new COVID vaccine he codeveloped with Maria Elena Bottazzi and other colleagues at Baylor University, it is entirely possible to reimagine forms of collaborative vaccine science diplomacy that avoid geopolitics and also plan for global deliveries without patents on the shared science [3]. There are also many advocates working for the WTO’s COVID-19 Technology Access Pool and within the Geneva orbit of the WHO who see the possibility of vaccine charity being rearticulated with vaccine liberty to move away from the neoliberal norms of public-private-philanthropic partnership represented by COVAX [41]. But so far, at least, the possibilities for real vaccine liberty on a global basis have remained preemptively concluded by the more dominant kinds of vaccine diplomacy and vaccine charity that we have reviewed here.

Contributor Information

Matthew Sparke, Politics Department, University of California Santa Cruz, Santa Cruz, California, USA.

Orly Levy, Politics and Feminist Studies, University of California Santa Cruz, Santa Cruz, California, USA.

Notes

Supplement sponsorship. This supplement is sponsored by the Precision Vaccines Program of Boston Children’s Hospital.

Neither author has a potential conflict of interest or a funding source for the research related to this article.

References

- 1. Petersen E, et al. Emergence of new SARS-CoV-2 variant of concern Omicron (B.1.1.529)—highlights Africa’s research capabilities, but exposes major knowledge gaps, inequities of vaccine distribution inadequacies in global Covid-19 response and control efforts. Int J Infect Dis 2022; 11:268–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. WHO . A global pandemic requires a world effort to end it. Available at: https://www.who.int/news-room/commentaries/detail/a-global-pandemic-requires-a-world-effort-to-end-it-none-of-us-will-be-safe-until-everyone-is-safe. Accessed 25 February.

- 3. Hotez P. Preventing the Next Pandemic: Vaccine Diplomacy in a Time of Anti-science. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Lee ST. Vaccine diplomacy: nation branding and China’s COVID-19 soft power play. Place Brand Public Dipl 2021:1–15. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Storeng KT, Puyvallée AB, Stein F. COVAX and the rise of the ‘super public private partnership’ for global health. Glob Public Health 2021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. UNICEF . COVID-19 Vaccine Market Dashboard, 2022. Available at: https://www.unicef.org/supply/covid-19-vaccine-market-dashboard. Accessed 25 February 2022.

- 7. Gonsalves G, Yamey G. The covid-19 vaccine patent waiver: a crucial step towards a ‘people’s vaccine’. Br Med J 2021; 373:n1249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Hancock J. They pledged to donate rights to their COVID vaccine, then sold them to pharma’ Kaiser Health News, Available at: https://khn.org/news/rather-than-give-away-its-covid-vaccine-oxford-makes-a-deal-with-drugmaker/. Accessed 25 February 2022.

- 9. Harman S, Erfani P, Goronga T, Hickel J, Morse M, Richardson E. Global vaccine equity demands reparative justice—not charity. BMJ Global Health 2021; 6:e006504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Hassan F, Yamey G, Abbasi K. Profiteering from vaccine inequity: a crime against humanity? BMJ 2021; 374:2027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Kapczynski A. The right to medicines in an age of neoliberalism. Humanity 2019; 10:79–107. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Sparke M, Williams OD. Neoliberal disease: COVID-19, co-pathogenesis and global health insecurities. Environ Plan A 2022; 54(1):15–32. doi: 10.1177/0308518X211048905. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Stiglitz J, Wallach L. Will corporate greed prolong the pandemic? Project Syndicate, May 6, Available at: https://www.project-syndicate.org/onpoint/big-pharma-blocking-wto-waiver-to-produce-more-covid-vaccines-by-joseph-e-stiglitz-and-lori-wallach-2021-05. Accessed 25 February 2022.

- 14. Yamin A, Farmer P. Against nihilism: transformative human rights praxis for the future of global health, Open Global Rights. Available at: https://www.openglobalrights.org/against-nihilism-transformative-human-rights-praxis-for-the-future-of-global-health/. Accessed 25 February 2022.

- 15. Ghebreyesus TA. WHO Director-General's opening remarks at 148th session of the Executive Board. WHO, 2022. 18 January 2021 Available at: https://www.who.int/director-general/speeches/detail/who-director-general-s-opening-remarks-at-148th-session-of-the-executive-board. Accessed 25 February 2022.

- 16. UN . Decrying Covid-19 vaccine inequity, speakers in general assembly call for rich nations to share surplus doses, patent waivers allowing production in low-income countries. 2021. Available at: https://www.un.org/press/en/2021/ga12367.doc.htm. Accessed 25 February 2022.

- 17. Bosire E, Mendenhall E, Omondi GB, Ndetei D. When diabetes confronts HIV: biological sub-citizenship at a public hospital in Nairobi, Kenya. Med Anthropol Q 2018; 32:574–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Sparke M. Austerity and the embodiment of neoliberalism as Ill-health: towards a theory of biological sub-citizenship. Soc Sci Med 2017; 187:287–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Büyüm AM. Decolonising global health: if not now, when? BMJ Global Health 2020; 5:e003394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Richardson E. Pandemicity, COVID-19 and the limits of public health ‘science’. BMJ Global Health 2020; 5:e002571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Richardson E. Epidemic illusions: on the coloniality of global public health. Boston: MIT Press, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 22. EIU . Western powers have lost the vaccine diplomacy battle, Economist Intelligence Unit. Available at: https://www.eiu.com/n/western-powers-have-lost-the-vaccine-diplomacy-battle. Accessed 26 February 2022.

- 23. Kier G, Stronski P. Russia’s vaccine diplomacy is mostly smoke and mirrors. Carnegie Endowment for International Peace 2021. Available at: https://carnegieendowment.org/files/Kier_and_Stronski_Russia_Vaccine_Diplomacy.pdf. Accessed 25 February 2022.

- 24. Hotez PJ, Narayan KMV. Restoring vaccine diplomacy. JAMA 2021; 325:2337–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Rodríguez-Garavito C. Human rights responses against vaccine apartheid, Open Global Rights. 2021. Available at: https://www.openglobalrights.org/human-rights-responses-against-vaccine-apartheid/. Accessed 25 February 2022.

- 26. Berkeley S. COVAX explained. Available at: https://www.gavi.org/vaccineswork/covax-explained. Accessed 25 February 2022.

- 27. Sparke M. Neoliberal regime change & the remaking of global health: from roll-back disinvestment to roll-out reinvestment & reterritorialization. Rev Int Polit Econ 2020; 27:48–74. [Google Scholar]

- 28. MSF . Covax: A Broken Promise to the World. Dec 2021. Available at: https://msfaccess.org/covax-broken-promise-world

- 29. Usher A. A beautiful idea: how COVAX has fallen short. Lancet 2021; 397(10292):2322–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Stein F. Risky business: COVAX and the financialization of global vaccine equity. Globalization and Health 2021; 17:112. doi: 10.1186/s12992-021-00763-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Mahase E. Covid-19: Rich countries are putting ‘relationships with big pharma’ ahead of ending pandemic, says Oxfam. BMJ 2021; 373:n1342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Goldhill O, Furneaux R, Davies M. ‘Naively ambitious’: How COVAX failed on its promise to vaccinate the world, STAT 2021. Available at: https://www.thebureauinvestigates.com/stories/2021-10-08/how-covax-failed-on-its-promise-to-vaccinate-the-world. Accessed 25 February 2022.

- 33. Mitchell K, Sparke M. The new Washington consensus: millennial philanthropy and the making of global market subjects. Antipode 2016; 48:724–49. [Google Scholar]

- 34. Elder K. Ahead of Gavi’s board meeting MSF urges critical look at COVAX shortcomings. 2021. Available at: https://msfaccess.org/ahead-gavis-board-meeting-msf-urges-critical-look-covax-shortcomings. Accessed 25 February 2022.

- 35. Nolen S. Here’s why developing countries can make mRNA Covid vaccines. New York Times, 22 October 2021. Available at: https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2021/10/22/science/developing-country-covid-vaccines.html#commentsContainer&permid=115138462:115138462. Accessed 25 February 2022.

- 36. Mutombo PN, et al. COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy in Africa: a call to action. Lancet, Global Health 2021; 10(3):E320–E321. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(21)00563-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Su Z, et al. COVID-19 vaccine donations—vaccine empathy or vaccine diplomacy? a narrative literature review. Vaccines 2021; 9:1024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Angell M. The pharmaceutical industry—to whom is it accountable? New England Journal of Medicine 2000; 342:1902–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Davis BG. Could you patent the sun? ACS Cent Sci 2021; 7:508–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Grewal DS. Before peer production: Infrastructure gaps and the architecture of openness in synthetic biology. Stan Tech L Rev 2017; 20:143. Available at: https://openyls.law.yale.edu/bitstream/handle/20.500.13051/4572/20_1_4_grewal_before_peer_production_1.pdf? sequence=2 [Google Scholar]

- 41. Geneva Global Health Hub . The politics of a WHO pandemic treaty in a disenchanted world. Available at: https://g2h2.org/posts/24-november-2021. Accessed 25 February 2022.