Abstract

COVID-19 cases on international cruise ships have attracted extensive attention from the international community as well as the world's tourism and shipping industry. This virus highlighted the plight that must be faced by cruise ships in complicated times and situations such as pandemics. The comparative method is adopted to analyze the management measures taken by the “Diamond Princess”, “Costa Serena”, “Westerdam” and “Grand Princess” cruises in response to the COVID-19 pandemic and then to summarize the common dilemmas faced by these cruise ships, including defects of their internal environment, unclear health-care obligations during an epidemic, weak collaboration between the parties involved and their limited performance, and widespread infodemic and unfavorable public opinion. Given these dilemmas, measures are suggested to deal with the “cruise dilemma”, including establishing and defining isolation standards on boards, enhancing the capacity of international organizations, the international community's joint response to the pandemic, promoting cooperation between countries, building an effective mechanism for the broad participation of the whole society, and standardizing the release of information and reasonably guiding public social opinion.

Keywords: COVID-19, Cruise tourism, Management strategies, Cruise dilemma, “Diamond princess”

Graphical abstract

1. Introduction

Cruise tourism is defined as a form of traveling involving an all-inclusive holiday on a cruise ship of at least 48 h with a set and specific itinerary in which the cruise ship calls at several ports or cities (Theobald, 2005; Klein, 2011). These cruises are characterized by a concentration of people (passengers) on a ship for a relatively significant period. According to the statistics from the Cruise Line International Association (CLIA), prior to the 1980s, this type of tourism was mainly considered a “privilege of a few elite”, but since then, this industry has constantly increased in popularity, reaching 30 million passengers in 2019 with a growth rate of 6.8% during the 2009–2019 period (CLIA, 2021a). Increased cruise tourism activity can kick start economic development within an area and consequently acts as a catalyst for other activities. Cruise tourism is an active, dynamic, and competitive industry that demands a continuous adaptation to customers' changing needs and desires; client satisfaction, enjoyment, and above all, safety are the main pillars of this profitable business.

COVID-19 is a contagious disease caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2). The virus is characterized by strong transmissibility and high infectiousness during its incubation period, which creates a dangerous threat to human health and life (He, 2020; Xu et al., 2021; Perillo et al., 2021; Milanes et al., 2021). The related impacts of world health events (i.e., Pandemics) became a topic of scientific concern starting in the second half of the 19th century (Yach and Bettcher, 1998). The discussion has focused on international laws and regulations to manage these events in recent decades. The increase in knowledge and the development of new technologies has led the international community to change the responses (management) to the diverse impacts generated for these world health events. From a historical point of view and according to the different management methods, the global approach to international public health can be divided into three stages (Table 1 ).

Table 1.

Development stage of a global joint response to the pandemic.

| Stage | Period | Organizations | Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| The 1st stage | Mid-19th Century → World War II | 1902, Pan American Sanitary Bureau | Importance was attached to the international law in the treaty-based governance of international public health events. |

| 1907, Office International d'Hygiène Publique | |||

| 1923, League of Nations Health Organization | |||

| 1924, Office International des Epizooties | |||

| The 2ndstage | End of the World War II → IHR (2005, International Health Regulations) | 1948, World Health Organization | The fulfilment of WHO's functions depended mainly on its members, and the gap among countries in economic, sanitary and medical technology development prevented many of the WHO's recommendations from being fully and effectively implemented. |

| The 3rdstage | IHR's entry into force → Present | WHO | IHR (2005) guaranteed the functions of WHO, standardized the obligations of its members, and achieved remarkable results in the governance of international public health issues. |

Source: Authors' compilation.

From these three stages, we can determine that effective management of international public health can be accomplished if the governance objectives are clearly defined, there exists active cooperation among stakeholders, the existing legal basis is sufficient and concrete, and the governance tools are specific and practical.The COVID-19 pandemic has created an unprecedented health and social scenario (Kane et al., 2021; Alfonso et al., 2021; Armenio et al., 2021; Fernández-González et al., 2022) and altered humans' everyday lives in all aspects, and of course, the tourism cruise industry is no exception. Since the COVID-19 outbreak, confirmed cases on international cruise ships, such as “Diamond Princess”, “Costa Serena”, “Westerdam” and “Grand Princess”, have focused the international community's attention on the dangers of cruise confinement (Sun and Zhao, 2022). Despite past norovirus outbreaks on cruise ships and despite the severity of the situation derived from COVID-19, countries have not reached a consensus on the prevention, control, and management of this kind of public health situation in particular environments, such as cruise ships. Even existing international conventions and domestic laws are inconsistent or, at a specific point, enter into conflict when the cruise industry tries to respond to these health events. The facts make clear that COVID-19 has been a virus without any such background information in our recent history. As long as cruise ships respond to these public health events, the existing international laws face an unprecedented challenge. The cruise dilemma has exposed a weakness in the existing international laws, which are focused on the distribution of national jurisdictions, leaving behind the protection of human safety. The above has generated a clear failure in the field of infection prevention and the management of public health on cruises.

COVID-19 is still active and continues to spread worldwide, generating a considerable impact on the global economy and the cruise industry. The cruise industry is facing complex challenges; from mid-March to September of the same year, cruise industry suspension caused global economic losses of 77 billion US dollars and job losses of 518,000 (CLIA, 2021b). When the “Diamond Princess”, “Costa Serena”, “Westerdam” and “Grand Princess” faced COVID-19, these cruise ships took different measures and achieved different results. After a comparison, this paper finds that the measures they take are different, and the results are also different. Therefore, taking the “Diamond Princess” with the most serious consequences as an example, the problems it encountered include defects in the internal environment on the ship, unclear obligations of cruise ship health protections, poor performance due to poor collaboration between different subjects and widespread infodemic and unfavorable public opinion. Finally, a set of solutions to cope with or at least minimize these related problems is also proposed.

The main body of this article is divided into three parts. Section 3 introduces the COVID-19 situation and summarizes the response of cruise ships in the event of COVID-19. Section 4 analyzes the specific embodiment of the cruise dilemma. In Section 5, this article proposes corresponding management strategies for dealing with the cruise dilemma.

2. Literature review, methods and materials

2.1. Literature review

The cruise ship industry has been heavily impacted by COVID-19 (Frittelli, 2020). During the COVID-19 pandemic, most of the coastal states lacked experience in addressing cruise pandemic responses (EU Healthy Gateways, 2021; Li et al., 2021; Bustos et al., 2021), and nearly 100 countries and regions closed their borders and banned the arrival of cruise ships (Cruise Critic, 2020). Cruise lines were practically shut down (Laskowski, 2020). For cruise ships that were still sailing and had infectious diseases, both passengers and crew felt helpless, anxious, and fearful (Subramanian, 2020). Taking the “Diamond Princess” cruise ship as an example, the first problem was jurisdictional (Matsui, 2021). Furthermore, the responsibilities and cooperation mechanisms of different actors are not clear (Zhou et al., 2020). Due to the differences between flag states and port states, cruise ships were unable to obtain help from flag states (Platzer, 2020).

Since there is no ensuing concrete legal consequence (Lin, 2020), there is clearly a need for a worldwide framework to tackle future crises (Dahl, 2020). In response to a series of problems encountered by cruise ships during the COVID-19 pandemic, some scholars proposed a reduction in passenger and crew population sizes, limiting the number of ports visited, shorter cruises (Pereira et al., 2021; Pedroza-Gutiérrez et al., 2021; Guagliardo et al., 2022), fewer and larger cabins should be created and more independent dining spaces and fewer seats should be created to increase personal space (Brewster et al., 2020). An ideal solution would be to create some kind of targeted system to ensure that only those who are contagious or potentially contagious are kept quarantined or isolated (Konnoth, 2020). Scholars have also suggested improving responsive measures in international law (Liu, 2021) and improving cruise tourism management (Hu and Li, 2022). Furthermore, who should bear the loss and how? Some scholars have proposed strengthening the jurisdiction of the flag state (Liu, 2021); national compensation funds will ideally play a supplementary role (Perry, 2021), and only cooperation between flag states and port states will make it possible to overcome any conflicts of implementation between the state sovereignty principle and assistance to persons in distress at sea (Choquet and Sam-Lefebvre, 2021).

2.2. Methods and materials

The literature was systematically searched, collected, and reviewed. This search was conducted primarily using the scientific databases Hein Online, Web of Science, Research Gate, Google Scholar, and the official websites of international organizations such as the United Nations World Tourism Organization (UNWTO). Information on COVID-19 was obtained from the World Health Organization (WHO) website. We collected accurate data on the victims of the “Diamond Princess” through the official website of the Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare of Japan.

The overall aim of this study is to analyze specific problems and difficulties caused by COVID-19 on cruise ships and to put forward countermeasures. This paper mainly adopts the method of comparative analysis. Comparison is a fundamental tool of analysis. It sharpens our power of description and plays a central role in concept formation by bringing into focus suggestive similarities and contrasts between cases (Collier, 1993). The “comparative analysis method” has a standard meaning within the discipline and in the social sciences more broadly: it refers to the methodological issues that arise in the systematic analysis of a small number of cases (Collier, 1993). This approach is developed by evaluating the countermeasures adopted for symptomatic confirmed cases on international cruise ships such as “Diamond Princess”, “Costa Serena”, “Westerdam” and “Grand Princess”. These four ships were chosen because they adopted different approaches to cope with the epidemic situation, reaching contrasting results. Through comparison, we can determine the specific dilemma of cruise ships when they encounter COVID-19. Fig. 1 shows a roadmap on the analytical framework of the article.

Fig. 1.

A roadmap on the analytical framework of the article

Source: Authors' compilation.

We cannot evaluate the advantages and disadvantages of national response measures based only on the results presented here. Therefore, after assessing all the methods used to minimize the COVID-19 impact on cruises, this paper points out the problems created by this virus in this type of tourism. The results are based on the analysis of documents promulgated by international organizations and actions taken by local governments regarding the management strategies used.

3. COVID-19 and experience of the cruise ship

3.1. COVID-19

In 2020, worldwide normalcy changed rapidly due to the COVID-19 pandemic. All activities in marine and coastal areas suffered in different ways from the resulting effects of massive population isolation (Menhat et al., 2021). Socioeconomic activities developed in coastal and marine areas, such as shipping and fisheries, had to adapt almost instantly to an emergency. COVID-19 certainly became the most troubling and complex pandemic that humanity has endured in the last century. This pandemic has dramatically impacted all social and economic systems and practices and triggered profound human health, development, and sociopsychological impacts on individuals, social groups, enterprises, and nations worldwide (Alcantara-Ayala et al., 2021). Since the COVID-19 outbreak, the international community's focus has been on how to deal with a complex situation that changes almost daily. While the WHO has been praised for its quickness in handling some of the more technical aspects of coping with this global crisis, countries approached the management of the situation individually.

In the case of China, the early lockdown and forced quarantine measures seem to have been effective, but such measures were not as easily implemented elsewhere (Casey, 2020). In South Korea, the focus has been on tracing the virus's spread through free, massive testing and then treating those infected. In this same country, social distancing has been encouraged through school closures, teleworking, and bans on large gatherings, but forced quarantine has not been implemented (Cha, 2020). Italy and Spain, which had a high number of deaths during the first wave, delayed their containment strategies and applied less restrictive lockdown methods (Benavides, 2020). In Germany, it is mainly local and regional governments that are responsible for health issues. In most cases, the federal government's role is limited to coordinating the measures undertaken by regional governments and recommending a specific course of action for the whole country (Terry, 2020).

Traditional global health leaders, such as the United States and the United Kingdom, proved to be unprepared to deal with the pandemic (Fidler, 2020). A strategy of containment, delay, research, and mitigation has produced mixed results in both countries. Schools in these countries stayed open longer, and initial restrictive measures were aimed more at the most vulnerable, such as the elderly and those with preexisting health conditions. While delaying actions may have allowed both countries to stave off some of the social and economic costs of the virus, it did not significantly lessen the spread of COVID-19 or subsequent deaths (Langfitt, 2020). Virtually all countries, either sooner or later in the pandemic, closed borders and/or restricted travel; in some cases, they trapped travelers away from home, including those on cruise ships. For example, Japan focused its actions on the prevention of disease entry and intensifying the capacity to face domestic spread (Matsui, 2021). This approach was used by several African countries and others that decided to increase border protection via flight restrictions, visa denials, and two-week quarantines for foreigners entering these countries. Currently, the main task of the WHO and the world governments is to deal with COVID-19, trying every means to control the pandemic and mitigate its harm based on three pillars: self-care, compassion, strengthening of health care (Gostin, 2019), continuing travel restrictions/requirements and quarantine when and where needed.

3.2. Cruise ship experience

In recent years, the cruise industry has become one of the most rapidly expanding, popular, profitable, and cost-effective businesses in the international tourism and services sector (Sun et al., 2019). The growth of cruise tourism has been characterized as explosive and phenomenal in recent decades (Papathanassis and Beckmann, 2011). Regarding the influence of COVID-19 on global cruise travel, COVID-19 has challenged the sufficiency of even these significant global efforts (Halabi, 2020), and the subsequent major impacts continue to impose new challenges to global cruise travel. The ongoing COVID-19 pandemic has compelled world governments to impose measures of restraint and social distancing involving coastal areas (Armenio et al., 2021).

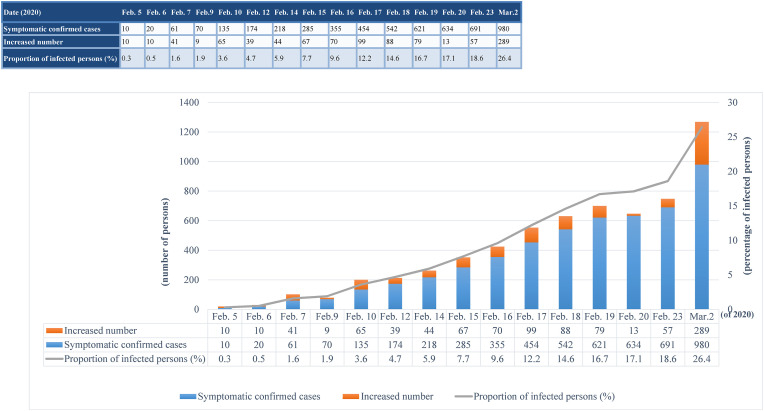

After the outbreak of COVID-19, symptomatic confirmed cases appeared on many cruise ships worldwide. Perhaps the most remarkable incident was that of the “Diamond Princess”. In January 2020, the British cruise “Diamond Princess” was affected by COVID-19 during its journey in Southeast Asia. There were 3711 passengers and crew members on board (National Institute of Infectious Diseases, 2020). Aside from the ten passengers initially confirmed to be infected and who were transported to hospitals, the rest of the passengers were not allowed to disembark and were confined to their cabins for fourteen days to see whether anyone else exhibited symptoms of the new coronavirus infection (Matsui, 2021). During the isolation period, the number of COVID-19 infections on this cruise ship increased. Because passengers on cruise ships came from different countries and regions, such as China, Japan, Britain, and the United States, the incident attracted extensive attention from the international community due to the isolation of the infection cases aboard. Fig. 2 shows that the number of confirmed cases increased rapidly and that the degree of attention to the incident also increased over time.

Fig. 2.

The development trend and percent of confirmed cases on the “Diamond Princess”

Source: Authors' compilation based on data collected from the websites of Japan's National Institute of Infectious Diseases (2020) (National Institute of Infectious Diseases, 2020).

However, the “Diamond Princess” was not the only case. Other cruise ships, such as “Costa Serena”, “Westerdam” and “Grand Princess”, were also affected by internal contagions. These four cruise ships adopted different approaches to cope with outbreaks, which resulted in different outcomes (Fig. 2). Although there were significant differences in the results, the fact that the proportion of confirmed passengers aboard the “Diamond Princess” was as high as 20% shows that the quarantine process implemented by Japan was far from optimal (Thompson and Yasharoff, 2020). Considering that the situation on each cruise ship was different, we cannot evaluate the advantages and disadvantages of national responses based on these results. However, COVID-19 has exposed the defects of the cruise ship industry when dealing with this kind of problem.

Fig. 3 briefly compares the place of departure, departure date, early warning time, docking place, prevention and control measures, follow-up treatment and infection statistics of the four international cruise ships. It can be seen from the epidemic events of each cruise ship share certain commonalities but also have their own unique peculiarities; different countries also displayed significant differences in the timing and methods of dealing with the epidemic. Judging from the results, the “Costa Serena” had no subsequent confirmed cases, and the entire processing process was widely praised; however, the “Westerdam” had doubts about its quarantine ability due to subsequent confirmed cases; the “Diamond Princess” had the largest number of infected people due to the quarantine on board, and it was also widely criticized by the international community; the “Grand Princess” took docking quarantine measures amid widespread international attention. Although there were 22 symptomatic confirmed cases, it is fortunate that the measures were taken properly, and the epidemic did not spread as much as it did on the “Diamond Princess”. Of course, the situation of each cruise ship is different, and it is not possible to simply evaluate the prevention and control measures of various countries based on the outcomes. However, since the consequences on the “Diamond Princess” were the most serious during the COVID-19 pandemic, this case caused the most controversy. Therefore, the following mainly analyzes the “Diamond Princess”.

Fig. 3.

Comparison of the COVID-19 outbreaks on popular international cruise ships

Source: Authors' compilation based on information compiled from the following materials: Thrilling 24 h -- the record of emergency response of Costa Selena (Xinhua, 2020b); About the current situation of new coronavirus infection and the response of the Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare (Ministry of Health Labor and Welfare, 2020); Press statement updates on the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) situation in Malaysia (Ministry of Health, 2020); Grand Princess accidents and incidents (CruiseMapper, 2020).

4. The specific “cruise dilemma”

International cruise ships generally sail through seas under the jurisdiction of multiple countries, and they carry many tourists. In the case of an epidemic, the difficulty is in determining which country is responsible for handling shipboard outbreaks. International cruise incidents may involve many countries, including the flag state of the cruise ship, the state of the port-of-call, the nationalities of the personnel on board (crew and passengers), and the country where the operator is located.

International and domestic laws regarding reception, rescuing, and applying control measures for international cruise ships with epidemic situations are inconsistent. This complexity led many countries to refuse to allow cruise ships to enter the port of call to avoid adverse effects (Hossain et al., 2021) based on considerations of national sovereignty or taking strict on-board isolation measures that seriously challenged the health rights of passengers and crew on board. Taking the “Diamond Princess” cruise ship as an example, Japan appeared unable to help the cruise ship as the port of call country. The United States, the country where the operator was located, stood idly by, and the United Kingdom, the ship's flag country, stayed out of the matter. These inactions caused the virus to spread rapidly, showed the lack of adequate response mechanisms, and exposed the total absence of cooperation between the involved countries.

4.1. Defects in the internal environment during cruises

Cruise vessels are isolated communities with a high population density, crowded public rooms, and living accommodations where sanitary facilities, water, and food supplies are shared. In these public areas, door handles, faucets, elevator buttons, handrails of stairs and passages and appliances in the buffet are common contact surfaces among passengers. These contact surfaces became the medium of virus transmission among passengers (Hu and Li, 2022). This crowding is even pronounced for ship crews. Hence, infectious diseases are easily transmitted abroad by infected persons and through different vectors, such as personal contact, contaminated surfaces, food, and water (Dahl, 2020).

From a medical resource perspective, cruise ships are usually equipped with basic medical facilities to provide medical services for passengers and crew. However, in the strict sense, their medical treatment capacity is considered very limited. In the case of severe emergencies, the medical conditions on cruise ships are unable to meet the real needs concerning medical resources. When passengers or crew members are unable to receive adequate treatment for a highly infectious virus, the result can be a mass infection. There are also deficiencies in daily epidemic prevention. For example, confirmed or suspected cases may not be effectively investigated and isolated in time. Alternatively, when disinfecting on board, it is impossible to accurately estimate the disinfection times and intensities, which results in insufficient effectiveness of ship disinfection efforts.

4.2. Unclear obligation of the cruise ship's health protection

On the “Diamond Princess” cruise ship, the first problem was a jurisdictional issue (Matsui, 2021). Most countries decline to accept cruise ships with public health risks with the pretext that they cannot take minimal health measures. Both the “Diamond Princess” and the “Westerdam” experienced delays while entering ports, and until now, there has been no risk assessment of these events based on objective evidence. The “Westerdam” had been drifting at sea for ten days before it docked in Cambodia on February 13, after being rejected by the ports of at least five countries or regions (Xinhua, 2020a).

Health protection on a cruise ship generally involves multiple sovereign countries. These countries include the flag state of the cruise ship, port-of-call countries, crew personnel nationalities, and the country where the operator is located. In the case of an on board epidemic, countries will dispute their responsibilities for control and treatment based on their national interests. At best, current provisions of international laws only define responsibilities or obligations for some limited subjects in specific fields related to health protections. Until there are international treaties that define and designate the distribution of countries' obligations and responsibilities for on-board health protection, there will be future health crises for the cruise industry.

For example, according to Article 94 (1) of the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), the flag State exercises jurisdiction and supervisory control over the administrative, technical and social matters of the ship. Public health management should be regarded as part of social matters, so when cruise ships sail on the high seas, the flag state should undertake its epidemic prevention and control obligations. According to the provisions of paragraph 2 of Article 98 under UNCLOS, the coastal state should undertake a general rescue obligation of ships that call in the country. Even if the coastal state is not obliged to receive epidemic-related cruise ships, it should actively carry out international cooperation and promote the establishment of a rescue system. While the International Health Regulations (IHR2005) provide for a system of free passage, according to paragraphs 1 and 2 of Article 28, a state party shall not deny a ship calling at any port of entry for public health reasons or refuse to grant entry to a ship that is not free from disease. Thus, the responsibilities of the flag state and the port-of-call country are listed in the UNCLOS, while core requirements of health capacity-building of port-of-call countries are found in the international health law. A similar situation exists for humanitarian health care/protection obligations, which are under the human rights laws. The International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR) is one of the most important human rights conventions. According to the right of health under Article 12 of the ICESCR, the state member has an obligation to ensure the “prevention, treatment and control of epidemic, endemic, occupational and other diseases”. Therefore, the nationalities of the passengers and crew members of the cruise ships involved in the epidemic have an obligation to rescue their own citizens. In the “Diamond Princess” incident, a large part of the reason why the port of Yokohama was willing to accept the “Diamond Princess” cruise ship was that there were many Japanese aboard.

Fig. 4 shows how international laws only stipulate the rights and obligations of some subjects in specific fields. These provisions are inconsistent or even conflict with the rights and obligations of health protection for a cruise in an epidemic situation. These inconsistent and legal conflicts allow many countries to fail to fulfill health-protection obligations. The above also allows them to avoid any type of participation (direct or indirect) in health protection on cruise ships.

Fig. 4.

Provisions related to cruise ships in international conventions

Source: Authors' compilation.

The management of a Public Health Emergency of International Concern (PHEIC), such as the coronavirus, may demand the application of overlapping international laws to cope with the situation. This complexity can blur the primary legal basis offered by IHR2005 and other treaties developed for the governance of the public health of the international community. These treaties do not provide legal consequences or responsibility for noncompliance with such obligations (Yee, 2020). Institutional overload and inconsistent standard-setting problems are already emerging in international health (Taylor, 2003). Additionally, public health issues involved in trade/economy concerns face many barriers, such as institutional resistance and a lack of coordination and resources (Sohn et al., 2004).

According to the above analysis, the flag state has an obligation to administer and control the epidemic situation on the cruise ship; the coastal state also has an obligation to grant epidemic-free passage to the cruise ship and the obligation to cooperate with neighboring countries to rescue the cruise ship. In the event of PHEIC, the coastal state can prevent the ship from entering the port or refuse to grant free passage on the grounds that “the port of entry does not have the capacity to implement sanitary measures” or that temporary sanitary measures are required; or on the grounds of the nationality of passengers and crew, based on the reason that the protection of human rights should entail actively rescuing the citizens of the country on the cruise ship. However, it is precisely because the abovementioned conventions have different regulations on who is obliged to rescue ships during COVID-19 that led to the “Diamond Princess” cruise ship incident; that is, when an epidemic occurs on the cruise ship, the flag state is indifferent, the coastal state shirks its responsibilities and has a failure of governance, and the countries of the nationalities of passengers and crew respond slowly, all reflecting the dilemma of the responsibility for cruise ships during an epidemic in practice.

To balance the health, trade, and movement of people, the IHR2005 empowers its members to enact laws to implement health policies following their circumstances on the condition that members adhere to the purposes of IHR2005 following Article 3.4. Although strengthening international cooperation in addressing global health issues has become a priority for many international organizations, unified coordination is still necessary. With many international organizations sharing law-making authority in global health and other health actors engaged in the international legislative process, international law-making can be considered fragmented, uncoordinated, and inefficient sprawl (Taylor, 2002). The most critical structural shortcoming of IHR2005 may be the lack of enforceable sanctions. For example, no legal consequences follow if a country fails to explain why it has adopted more restrictive traffic and trade measures than those recommended by the WHO. Based on the experiences of the cruises handling COVID-19 during the 2020–2021 period, it is evident that many operational problems exist within the IHR2005. The role of the IHR2005 seems not to be critical in guiding state parties to tackle such an outbreak (Lo, 2020). The pandemic-exposed controversies and gaps in international law suggest that global health treatment currently lacks the oversight of an effective system of law (Fidler, 2020).

4.3. Limited performance due to poor collaboration between different subjects

The cruise ship “Westerdam” was forced to drift at sea for 13 days. This highlighted a cautious attitude by countries toward ship arrivals after the COVID-19 outbreak. This kind of attitude and behavior caused many problems and inconveniences for passengers and crew members. The roles and responsibilities and the cooperation mechanisms of different actors are not clear in relation to public health emergencies during travel (Liu-Lastres et al., 2019). The shifts in global health law have driven many changes by lawmaking authorities toward a broader, more diverse range of the international actors involved. The new actors include United Nations (UN) agencies, UNWTO, International Arbitral Tribunals, UN Security Council, and large enterprises in health-related sectors such as food, medicine, and tobacco (Halabi, 2020). The COVID-19 outbreak exposed a collective vulnerability to an invisible enemy that could easily penetrate any border (Lee, 2020). In the face of a PHEIC, concerted efforts are needed from international organizations, countries, nongovernmental social organizations, enterprises, and individuals. From the cruises in the fight against COVID-19, poor coordination between the international public health governance subjects was a common denominator and became a problem out of hand.

First, the problem of uneven global development and scarce medical materials is undeniable. People in lower-income countries are most vulnerable and the social and economic infrastructure (including health systems) of these countries are less able to deal with novel and emerging infectious diseases (Kieny et al., 2014). People in these countries most often experience poor governance, violence, and political instability. By comparison, costly therapy and precision medicine are mostly available in wealthier countries (Gostin and Eric, 2020). The current signs are worrisome; critically needed medical supplies (including vaccines) and equipment necessary to cope with the COVID-19 situation have gone primarily to wealthy countries (such as the United States and Europe), which pay more for them (Bradley, 2020). A vast number of the world's people, overwhelmingly poor and marginalized, have not benefited from global health improvements (Gostin and Eric, 2020). These immense global health disparities are echoed in gaping inequities within countries—sometimes narrowing but often expanding (Gostin and Eric, 2020). Global forces, however, make it exceedingly hard to achieve health with equity, equality, and justice. The above makes it evident that there are significant differences in the resources available to governments worldwide to face the pandemic.

Following Articles 28 and 43 of IHR2005, a contracting member shall not prevent ships or aircraft from calling at any port of entry for public health reasons, nor shall it prevent passengers from getting on and off. However, when certain conditions are met, the contracting member may take additional health measures, including the prohibition of entry. In terms of additional health measures, it entirely depends on the epidemic prevention facilities, epidemic prevention level, and emergency management capacity at the port of entry. These factors vary significantly between developed and developing countries. Article 8.1.10 of the Handbook for Management of Public Health Events on Board Ships, promulgated by the WHO in 2016, states that “to prevent the international spread of disease and depending on the situation, entry or exit of a suspected or affected person can be denied”. As seen from the provisions of this article, on the issue of whether persons can enter after the ship enters port, members have significant discretion and can decide whether to allow persons to enter based on the actual situation. Therefore, it is not difficult to understand why the Japanese government decided to isolate all personnel of the “Diamond Princess” cruise ship for two weeks.

Second, no country acting alone can ensure all the conditions for health in this type of situation. To understand this, we can use as examples transnational forces/processes such as greenhouse gas emissions, volcanic eruptions or tsunamis, or global rules, and norms in areas such as trade and investment (Ottersen et al., 2014), transnational corporations that actively seek low-tax, low-regulation destinations, or the rapid spread of communicable diseases, such as COVID-19. From a geographical point of view, the imbalance in a country's development can be observed at many levels. Whenever an epidemic breaks out, the affected country or region's first response is the need for dynamic help from other countries to cope with the situation. Usually, countries that bear the disproportionate burden of disease have less capacity to manage the problem. In contrast, countries with the tools to manage health crises are deeply resistant to expending their political capital and economic resources necessary to improve health outside their borders (Gostin, 2008).

Despite IHR2005's demands of its members that they improve their domestic health-care conditions, developing countries, economically and technologically limited, are still unable to improve their domestic public health systems. These countries have difficulty providing adequate medical materials within a short time frame to deal with a PHEIC. Large cities and rural areas within these same countries are faced with different challenges when responding to a pandemic due to many factors, such as population density and infrastructure quality (Terry, 2020). Global health with justice (a world where all people, wherever they live and whoever they are, can equally benefit from health improvements) remains over the horizon (Gostin and Eric, 2020).

Furthermore, most countries are faced with internal differences in terms of economic and medical development between different regions inside their borders. This variation results in a heterogeneous and fuzzy ability to respond to any PHEIC. For countries that lack a strong central government to coordinate regulations and responses, the result is that different areas of the country will respond to a crisis in an uncoordinated manner. Trade activities also impact an individual nation's willingness to regulate public health and safety standards (Sohn et al., 2004). These activities can generate friction for cooperation mechanisms, including international law, emphasizing information sharing, science-based decision-making, and equitable access to health resources (Fidler, 2020). Thus, the lack of cooperation or poor collaboration between the various governance subjects seriously impaired the response to the COVID-19 pandemic.

4.4. Widespread inflammatory and unfavorable public opinion guidance

Messaging plays an important role in cruise pandemic prevention and control, meaning that cruise liners are supposed to maintain an open and communicative attitude toward passengers (Liu-Lastres et al., 2019). However, it is difficult for passengers to recognize the actual risk of infectious disease transmission, and the information dissemination on the cruise ship is not so smooth. Information management also played an essential role in COVID-19's cruise dilemma. After all, the cruise ships were isolated, and the information released by the governments and cruise companies was very limited compared to data presented for new cases confirmed daily by countries. During the isolation, no official information was presented about core issues such as domestic and foreign legal bases, specific prevention and control measures, or the implementation effect of isolation measures on board adopted by each government. In this way, the situation inevitably attracted more attention than usual, and comments from society and the media generated an infodemic.

According to the WHO, an infodemic situation is defined as too much information, including false or misleading information, in digital and physical environments during a disease outbreak (WHO, 2018). An infodemic, such as epidemics, involves the rapid spread of information of all kinds, including rumors, gossip, and unreliable data. The world is in an era of network connectivity, information flooding, and rapid dissemination of information. Once a public health emergency begins in a specific place, it quickly becomes the world's focus, generating various online comments mixed with both rational analysis and irrational misinformation, which together generate confusing noise. Under current world conditions, infodemics are a common distraction and can interfere with outbreak response, encompassing three main areas according to WHO: monitoring and identifying health threats, outbreak investigation, and actions for mitigation and control (WHO, 2018). Two basic needs drive these three areas. First, to prevent the epidemic from spreading, affected cities and countries may adopt lockdown policies, which increase the expectation of facts and security concerns. Second, people worry about reality, which is of little help in managing the pandemic.

After the COVID-19 outbreak, public media and the internet were full of different voices communicating all types of information (real and fake), seriously affecting the morale and enthusiasm of the people affected by the pandemic in terms of their responses. Given this situation, some countries promulgated restrictions, laws and even bans on the generation of new information that might go against fundamental human rights (Zhang, 2021). Experts are worried that some restrictions fail to meet necessary principles to ensure respect for human rights (Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights, 2020). Others contend that there has been increased pressure on civil liberties during the pandemic due to the enactment of states of emergency or emergency powers, which can influence opinion, freedom of the press and debate/discussion (Wiratraman, 2020).

Here, it is essential to highlight that a “state of emergency” is based on the somewhat artificial dichotomy of norms and exceptions, which endorses a bifurcated approach to balancing the interests of societal goals and individual rights (Wiratraman, 2020). Therefore, the extent to which COVID-19-related restrictions represent a departure from past governance patterns also varies between countries (Weber et al., 2020).

5. Management strategies to deal with the “cruise dilemma”

COVID-19 has been considered the “black swan” event of 2020 (Lim, 2020). Such events are no longer small probability events in human history, especially after entering the 21st century, where PHEIC has appeared many times. The first recorded smallpox epidemic began in Egypt in 1350 BCE, reaching China in 49 CE, Europe after 700, the Americas in 1520, and Australia in 1789. The bubonic plague, or “Black Death”, originated in Asia and spread to Europe in the fourteenth century, where it killed a fourth to a third of the population. Europeans carried diseases to the Americas in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries that destroyed up to 95 percent of the indigenous population (Nye and Welch, 2017). From the 1980s to the mid-21st century, 2013–2015, there were more than 12,000 significant outbreaks of novel diseases, 215 infectious diseases, and 44 million cases in 219 countries (Gostin, 2019).

Nevertheless, public health problems have been featured urgently and comprehensively in domestic and world affairs' political, economic, and social dynamics (Fidler, 2008). At the beginning of the 21st century, there was widespread recognition that national and international health are inseparable (Taylor and Bettcher, 2002). COVID-19 spread to many countries in less than a month. New PHEIC may still appear in the future. To avoid the cruise dilemma, cruise ships, as a prominent manifestation of the global public health crisis, will require the cooperation of all governance subjects. Management considerations to be implemented can be divided into four specific strategies.

5.1. Establishment and definition of isolation standards on board

Due to the internal environment of the cruise ship, once an epidemic occurs inside a cruise ship, it can spread easily and rapidly. In a scenario in which a port may not accept or cooperate during an epidemic, the cruise ship must be prepared with a clear prevention/contention/management strategy that must begin with one of the environments where the virus moves: the ventilation system. Modifying the ventilation system of a ship is both complex and expensive, generating a real cost-profit issue for the cruise company.

Another innovation is the Containerized Bio-Containment System (CBCS), which provides an optimal reference system for on board prevention and contention. The CBCS is a reliable, flyable medical transport unit to evacuate patients to clinical centers for life-saving treatment while maintaining full biocontainment. This system is mainly used to isolate and treat patients with severe infectious diseases during transportation processes (air, land, sea). The CBCS brings new possibilities in terms of prevention and contention of an epidemic on a cruise ship and does not require a total transformation of the ventilation system.

For optimal on board isolation, cruise ships could be equipped with several CBCSs, each with an independent ventilation system to isolate a few infected tourists at the beginning of the epidemic and thus avoid uncontrollable outbreaks. These independent containers are usually placed in a warehouse, which will not impact the daily operations of the cruise ship. In the case of emergencies, they can be temporarily placed on the top deck.

5.2. Enhance the capacity of international organizations

Both the “Diamond Princess” and the “Westerdam” experienced delays while entering the port. This is because once an epidemic occurs, international organizations have no coercive force to require a country to rescue the cruise ship infected by the epidemic. The WHO and the International Maritime Organization (IMO) must establish an optimal cooperation mechanism for the cruise industry's response to pandemics. As an organization in the field of global public health, the WHO should play a leading role in the construction of international cooperation mechanisms. However, as noted, current WHO mechanisms have many disadvantages.

-

•

Cruise ships are always moving on the sea. This involves obligations from different countries and thus sometimes makes the WHO global network system unable to play its role in a timely manner. Based on the legal system of ships, flag state control, and port state control established by many maritime conventions over the years (Zhang and Wang, 2022), the IMO can quickly implement convention obligations through the emergency response mechanism of the maritime administration of relevant countries. Therefore, the WHO and IMO should guide CLIA and the International Protection and Indemnity Association in the establishment of an international cooperation mechanism for cruise epidemic prevention and control.

-

•

The creation of a mechanism that reports/notifies any epidemic issues on cruise ships.

This mechanism must include the maritime administration of the flag state and the country's maritime administration where the actual ship operator is located. It is also expected that maritime administration of the historical port-of-call is involved together with the maritime administration of the affiliated port and local health and epidemic prevention department (or its equivalent). This involvement not only makes full use of the WHO's relevant experience in dealing with PHEIC. In the same way, this agency plays an active role in global information sharing, the unification and coordination of response measures, and public opinion response but also makes up for the disadvantages of countries that are trying to maintain freedom of action in public health matters and are unwilling to grant the WHO too much legislative power. Moreover, it also makes full use of IMO network resources to help epidemic emergency measures more suitable for the characteristics of ships and maritime activities.

The implementation and application of the IHR2005 is a shared responsibility of all the states' parties and WHO. As the largest international health organization and one of the larger specialized agencies of the United Nations, the WHO has far-reaching responsibilities to address global public health based on the responsibilities assigned by its constitution and its affiliation with the United Nations (Taylor, 2002). Article 2 of the WHO Constitution lists twenty-two functions of this organization, which, given the size and scale of the COVID-19 pandemic, almost all seem relevant to the impact of the disease (Gastorn, 2020). The WHO has unparalleled law-making power among international organizations with law-making authority (Lee, 2020). With its power and authority, this agency can influence international health policies. However, with the agency's visible reluctance to utilize its law-making power (Gostin et al., 2015), commentators have observed that the WHO is more satisfied with acting as a technical agency rather than embracing a leadership role in global health (Gostin et al., 2015).

A framework convention on global health or a similar mechanism would not be easy to achieve, and being realistic, it certainly would not provide an ideal solution. However, a framework convention would go toward the heart of the problem because it would address states' obligations to act outside their borders and, thus, establish the levels of commitment and the kinds of interventions necessary to make a meaningful difference in the world's population (Gostin, 2008).

In day-to-day public health governance, state parties should work actively with the WHO, mobilize financial resources, and facilitate the implementation of their IHR2005 obligations. They also must improve their national surveillance and response infrastructure to enable timely warning of public health risks and emergencies. In a public health risk or emergency, state parties shall promptly notify the WHO of the relevant risks and circumstances. The WHO should assess the situation in the country where the risk or event occurs and establish a particular event information website. While the event is in progress, the state's parties shall faithfully report daily to the WHO, which will publish the data on its website. The WHO shall make relevant information available to all focal points of state parties and the public, along with progress, guidance, and warnings.

In the case of a particular outbreak, the WHO should assign commissioners to the outbreak site for a rapid, better, and informed response. All the above functions shall be strictly observed and carried out by the WHO and the states' parties. State parties shall provide all facilities and support to the WHO for a better organization and performance of its duties. Additionally, the WHO must establish specific indicators for core competency readiness, which it hopes will help to better gauge member states' preparedness to respond to a public health emergency (Hyle et al., 2009). At a local level, the handling and control of COVID-19 and future pandemics are duties of governments in their respective jurisdictions. The WHO must work closely with governments in outbreak mitigation based on IHR2005 (Lo, 2020). Whether some of the criticism of the WHO's initial reaction to the crisis is justified or not, the situation provides an opportunity for this forum to share experiences and resources (Terry, 2020).

In an interconnected world driven by an increased economic globalization rate, global health governance can be considered contentious due to ideological disagreements (Lee, 2020). With this knowledge, during the extraordinary summit on COVID-19 (September 2021), the participating parties committed to taking all necessary actions within their respective mandates with relevant international organizations, including the WHO. They also expressed full support and commitment to enhancing the WHO's role in coordinating international anti-epidemic actions (People’s Daily, 2020).

5.3. Extensive participation of various subjects in the response to the epidemic

Since the place of registration, place of business, departure port, transit port, destination port, and passengers on the cruise ship may be in multiple countries, once an epidemic occurs on the cruise ship, it is difficult for a single country or organization to deal with it. This requires the joint efforts of all subjects to deal with it together.

5.3.1. Joint responses to the epidemic by the international community

The health protection for cruise ships with on board epidemics is not only a question of whether port countries are willing to accept a cruise ship but is also a public health and safety matter faced by the international community, requiring joint participation and response (Edwards, 2021). Health protection on a cruise ship with an epidemic situation is a humanitarian problem that must be faced and managed by the international community.

From a global perspective, emphasis must be placed on the obligation for cooperation between all agencies of the international community. This goal can be achieved by strengthening communication and cooperation with the WHO and other United Nations organizations, strengthening cooperation with other port countries based on building an effective epidemic cruise ship health-protection system, and protecting the minimum health rights and interests of passengers and crew on board.

The mechanisms for dealing with epidemic issues aboard cruise ships require the international community's joint participation, and there is currently a global consensus on the necessity of such updates. At the same time, in the context of a public health crisis, the responsibility of a state to protect human rights is not an “individual problem of a country” in a specific field. Instead, responses to pandemics are a comprehensive issue related to the international community's stability and the well-being of the global population.

5.3.2. Promotion of cross-border cooperation

Because of globalization, governments must increasingly turn to international cooperation to attain national public health objectives and to achieve some control over the transboundary forces that affect their populations (Taylor, 2003). As a result, countries in today's world must form interdependent relationships. Interdependence leads to shared benefits, which in turn encourage cooperation. Public health features universality, actuality, and practicality in application because it involves the fundamental and pervasive aspects of people's lives. Therefore, cooperation is conducive to people's well-being and will achieve a positive effect.

With the rapid outbreak of the novel coronavirus worldwide, and especially on cruise ships, the effective management of the outbreak required concerted global efforts (Lee, 2020). Leadership from heads of state and government helps boost management experience into national and global agendas (Gostin and Eric, 2020). Having paid an elevated price (i.e., deaths, contagions, economic losses), later in the pandemic, the international community strengthened joint efforts to combat the virus (Yang, 2020). The G20 Extraordinary Leaders' Summit, held on March 26 in response to the COVID-19 pandemic, marked the formation of an international consensus in which leaders expressed their commitment to task our top relevant officials with closely coordinating to support the global efforts to counter the pandemic's impacts. All countries should cooperate actively in the face of a public health event. First, affected countries or regions should take measures as soon as possible to prevent the epidemic from spreading to other countries. Second, other countries should help the affected countries as much as possible. State and local health departments are vital to protecting a nation from epidemics (Price, 2019). In today's globalized world, helping other countries to break away from the impact of public health events is essential to help oneself.

5.3.3. Build an effective mechanism for the broad participation of the whole society

While the WHO recognizes its responsibility as stated in its constitution for the nomenclature of diseases, the WHO also has been mindful of its functions to coordinate with other UN specialized agencies and scientific and technical groups (Gastorn, 2020). Unfortunately, the vast array of international health actors actively involved in global health cooperation, combined with people's widespread criticism of the United Nations and its specialized agencies, suggest a diminishing role for intergovernmental organizations in global health governance. Achieving global health justice requires authentic cooperation because the production of health equity at the global and domestic levels involves interdependent parties. This task requires individuals and groups to embrace and successfully fulfill their respective roles and responsibilities based on functions and needs and voluntary commitments (Ruger and Jennifer, 2012).

Some people have emphasized a ‘power shift’ from intergovernmental organizations to private-sector actors and the creative health coalitions described above (Kaul et al., 1999). Because public–private partnerships have proliferated since 2000, the contractual relationships between firms, governments, and large health-oriented foundations may serve as a significant source of global health law (Halabi, 2020). The dispersal of governance in contemporary history has occurred across different layers and scales of social relations from the local to the global, along with the emergence of various private regulatory mechanisms as well as those in the public sector (Scholte, 2005).

People are demanding decent health services. They want caring, compassionate, and highly qualified professionals. They demand affordable access to essential medicines, vaccines, and medical devices (Gostin and Eric, 2020). In responding effectively to significant disease outbreaks, in addition to the government and scientific research institutions, large pharmaceutical enterprises and research and development centers also play an active role through their advanced research resources and strong capability in research and development on immune and anti-epidemic drugs. Additionally, to face the virus, donations from all walks of life greatly alleviated medical and material resource shortages in the most affected areas. Given today's high-tech development, technology companies dominating artificial intelligence and drug development are indispensable in the fight against infectious diseases. Many volunteers are also a solid resource for countries to deal with outbreaks. Therefore, the WHO and countries should actively support and encourage these enterprises and individuals to make joint efforts.

5.4. Standardize the release of information and reasonably guide public opinion

In social networks, most public health emergencies belong to information communication activities shared in groups. The control of public opinion requires the mutual coordination and guidance of multiple institutions and organizations. Therefore, after COVID-19, as well as in future outbreaks, governments should take full advantage of the media to obtain accurate information and to release the latest information quickly and precisely about the epidemic situation, which should improve the public's understanding. Relevant governments and cruise companies should communicate closely to ensure all information is communicated smoothly and that it meets the standards of accuracy and consistency.

The infodemic played a role in health care during the pandemic. Prevention and control of infectious diseases inevitably involve reducing and restricting some human rights due to the use of sanitary measures. However, sanitary measures that restrict individual rights must follow the minimum principles of necessity and fairness. Public health authorities around the world have been legitimately concerned about misinformation during the COVID-19 pandemic. Unreliable information, mainly when disseminated by individuals from social media platforms, can cause severe harm and problems, whether maliciously intended or not. According to the WHO, successful management of infodemics must be based on monitoring, identification, analysis, control, and mitigation (WHO, 2018). In the 20th century, the exercise of public health powers that infringe on individual rights faded in developed countries as public health and health care systems improved (Fidler, 2002). Paragraph 1 of Article 3 and Article 32 of IHR2005 demonstrate the importance of human rights protection in international health governance. To explain the relation between optimal governance and human rights, “governance” is a right, whereas “human rights” are freedoms that authorities must defend (Ferreira-Snyman and Ferreira, 2006). Therefore, the IHR2005 stipulates the goals of international public health governance and incorporates the principle of human rights into its implementation system. In this sense, IHR2005 helps construct a public health system that integrates security, economy, people's livelihood, development, and human dignity with the attributes of public goods, rather than the previous IHR that was limited to removing restrictions on trade and travel.

Public opinion is the sum of the public's convictions, attitudes, and emotions in response to phenomena and societal problems, mixed with rational and irrational factors. However, how public opinions are developed determines whether their effects on social development and events are positive or negative. In this modern society featuring easy internet access, people's ideas and values are more diversified, as are their ways of receiving information and channels of spreading information. Additionally, compared with the traditional model, the development of public opinion is more rapid, and the combination of truth and rumor exerts a more obvious double-edged sword effect.

The importance of public opinion is evident. Therefore, as the provider of information and guidance for the global response to the pandemic, the WHO should, while ensuring the timely release of accurate information, clarify the spread of false information in society so that all people can feel optimistic about the situation through accurate information. Information management may be seen through the lens of government obligations and company responsibilities, particularly for companies involved in internet searching or social media. On February 14, WHO officials met with representatives from more than a dozen U.S. technology companies, including Facebook, Google, and Amazon; the primary topic of discussion was how these companies are working to tamp down the spread of misinformation (Farr and Rodriguez, 2020). In addition, all news media and other media should work hard to contain the spread of wrong information (misinformation, intentional disinformation) about epidemics to avoid public panic, which may affect efforts to prevent and control their spread.

6. Conclusions

Global public health security is a common aspiration. Against the background of globalization, the outbreak of a series of public health crises has posed an unprecedented threat to the international community. As an essential embodiment of the global public health crisis, the cruise epidemic has salient features in the form of the response to the epidemic, the manner of health protection, the allocation of responsibilities, and the subjects involved. This article compares the countermeasures of the four cruise ships “Diamond Princess”, “Costa Serena”, “Westerdam” and “Grand Princess” in response to COVID-19 outbreaks and then summarizes the shared dilemma faced by these cruise ships, including the defects of their internal environment, unclear health-care obligations in case of epidemic, weak collaboration between the parties involved and their poor performance, and widespread infodemic and unfavorable public opinion. Based on the international and domestic legal systems involved in the daily operation of cruise ships, this paper puts forward suggestions from the three dimensions of prevention in advance, control during the event, and inspection after the event. Measures taken by cruise ships to deal with the cruise dilemma include establishing and defining isolation standards on board, enhancing the capacity of international organizations, the international community's joint response to the pandemic, promoting cooperation between countries, building an effective mechanism for broad participation of the whole society, and standardizing the release of information and reasonably guiding public social opinion.

This article identifies the various problems that cruise companies have encountered during the COVID-19 pandemic and provides suggestions on how to deal with them. It is hoped that the research of this article, first, will provide a reference for the IMO, the WHO and other international organizations to revise their relevant international conventions; second, will provide suggestions for the domestic legislation of various countries to prevent the problems caused by PHEIC; and finally, will also provide recommendations for cruise companies to deal with possible PHEICs in the future. Of course, in response to the dilemma encountered by cruise ships during the epidemic, this article only proposes some macro response plans. Future research will take a specific problem as a starting point, conduct in-depth analysis, and put forward more detailed and actionable suggestions.

Funding

2019 major project of National Social Science Foundation of China “Research on the construction of legal system of socialist foreign relations with Chinese characteristics” (19ZDA167), 2019 annual research project of East China University of political science and law “Research on optimizing the legal guarantee of business environment in Shanghai”.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Data availability

The authors are unable or have chosen not to specify which data has been used.

References

- Alcantara-Ayala I., Burton I., Lavell A., Mansilla E., Maskrey A., Oliver-Smith A., Ramirez-Gomez F. Root causes and policy dilemmas of the Covid-19 pandemic global disaster. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduc. 2021;52 doi: 10.1016/j.ijdrr.2020.101892. article no. 101892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alfonso M.B., Arias A.H., Menéndez M.C., Ronda A.C., Harte A., Piccolo M.C., Marcovecchio J.E. Assessing threats, regulations, and strategies to abate plastic pollution in LAC beaches during COVID-19 pandemic. Ocean Coast Manag. 2021;208 doi: 10.1016/j.ocecoaman.2021.105613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armenio E., Mossa M., Petrillo A.F. Coastal vulnerability analysis to support strategies for tackling COVID-19 infection. Ocean Coast Manag. 2021;211:1–17. doi: 10.1016/j.ocecoaman.2021.105731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benavides L. 2020. Spain Briefly Passes Italy in Covid-19 Cases but Officials See Growth Rate Slowing.https://www.npr.org/sections/coronavirus-live-updates/2020/04/03/826699690/spain-briefly-passes-italy-in-covid-19-cases-but-officials-see-growth-rate-slowi [Google Scholar]

- Bradley J. In scramble for coronavirus supplies, rich countries push poor aside. 2020. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/04/09/world/coronavirus-equipment-rich-poor.html

- Brewster R.K., Sundermann A., Boles C.M. Lessons learned for COVID-19 in the cruise ship industry. Toxicol. Ind. Health. 2020;36:728–735. doi: 10.1177/0748233720964631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bustos M.L., Zilio M.I., Ferrelli F., Piccolo M.C., Perillo G.M., Van Waarde G., Manstretta G.M.M. Tourism in the COVID-19 context in mesotidal beaches: carrying capacity for the 2020/2021 summer season in Pehuén Co, Argentina. Ocean Coast Manag. 2021;206 doi: 10.1016/j.ocecoaman.2021.105584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casey H. Covid-19 and its international response. Australian Law Librarian. 2020;28:96–99. https://search.informit.org/doi/10.3316/agispt.20210909053194 [Google Scholar]

- Cha V. 2020. South Korea Offers a Lesson in Best Practices.https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/united-states/2020-04-10/south-korea-offers-lesson-best-practices [Google Scholar]

- Choquet A., Sam-Lefebvre A. Ports closed to cruise ships in the context of COVID-19: what choices are there for coastal states? Ann. Tourism Res. 2021;86 doi: 10.1016/j.annals.2020.103066. article no.103066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CLIA . Cruise Lines International Association; Washington: 2021. 2019 Cruise Trends and Industry Outlook.https://cruising.org/-/media/eu-resources/pdfs/CLIA%202019-Cruise-Trends--Industry-Outlook [Google Scholar]

- CLIA State of the cruise industry outlook. 2021. https://cruising.org/-/media/research-updates/research/2021-state-of-the-cruise-industry_optimized.ashx Available online at:

- Collier D. In: Political Science: the State of the Discipline II. Finifter A.W., editor. American Political Science Association; Washington: 1993. The comparative method; pp. 105–119. [Google Scholar]

- Critic Cruise. 2020. 2021. Coronavirus: Which Cruise Ports Are Closed?https://www.cruisecritic.com/news/5097/ [Google Scholar]

- CruiseMapper . 2020. Grand Princess Accidents and Incidents.https://www.cruisemapper.com/accidents/Grand-Princess-697 [Google Scholar]

- Dahl E. Coronavirus (Covid-19) outbreak on the cruise ship diamond princess. Int. Marit. Health. 2020;71:5–8. doi: 10.5603/MH.2020.0003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards N. Politics of the coastal professional. Ocean Coast Manag. 2021;202 doi: 10.1016/j.ocecoaman.2020.105419. article no. 105419. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- EU Healthy Gateways . 2021. COVID-19: EU Healthy Gateways Advice for Cruise Ships Operations.https://www.healthygateways.eu/ [Google Scholar]

- Farr C., Rodriguez S. 2020. Facebook, Amazon, Google and More Met with WHO to Figure Out How to Stop Coronavirus Misinformation.https://www.cnbc.com/2020/02/14/facebook-google-amazon-met-with-who-to-talk-coronavirus-misinformation.html?&qsearchterm=Menlo%20Park [Google Scholar]

- Fernández-González R., Pérez-Pérez M., Hervés-Estévez J., Garza-Gil M.D. Socio-economic impact of Covid-19 on the fishing sector: a case study of a region highly dependent on fishing in Spain. Ocean Coast Manag. 2022;221 doi: 10.1016/j.ocecoaman.2022.106131. article no. 106131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferreira-Snyman M.P., Ferreira G.M. Global good governance and good global governance. South African Yearbook of International Law. 2006;31:52–94. [Google Scholar]

- Fidler D.P. Introduction to written symposium on public health and international law. Chicago J. Int. Law. 2002;3:1–6. https://chicagounbound.uchicago.edu/cjil/vol3/iss1/4 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fidler D.P. Global health jurisprudence: a time of reckoning. Georgetown Law J. 2008;96:393–412. https://www.repository.law.indiana.edu/facpub/141 [Google Scholar]

- Fidler D.P. To fight a new coronavirus: the Covid-19 pandemic, political herd immunity, and global health jurisprudence. Chin. J. Int. Law. 2020;19:207–213. doi: 10.1093/chinesejil/jmaa016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Frittelli J. Congressional Research Service; 2020. COVID-19 and the Cruise Ship Industry.https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/IN/IN11245 [Google Scholar]

- Gastorn K. To name a new coronavirus and the associated pandemic: international law and politics. Chin. J. Int. Law. 2020;19:201–206. doi: 10.1093/chinesejil/jmaa024. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gostin L.O. Global health law governance. Emory Int. Law Rev. 2008;22:35–48. [Google Scholar]

- Gostin L.O. Global health security in an era of explosive pandemic potential. Asian Journal of WTO and International Health Law and Policy. 2019;14:267–285. [Google Scholar]

- Gostin L.O., Eric A.F. Imagining global health with justice: transformative ideas for health and well-being while leaving no one behind. Georgetown Law J. 2020;108:1535–1606. [Google Scholar]

- Gostin L.O., Stridhar D., Hougendobler D. The normative authority of the world health organization. Publ. Health. 2015;129:1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2015.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guagliardo S.A.J., Prasad P.V., Rodriguez A., Fukunaga R., Novak R.T., Ahart L., Reynolds J., Griffin I., Wiegand R., Quilter L.A.S., Morrison S., Jenkins K., Wall H.K., Treffiletti A., White S.B., Regan J., Tardivel K., Freeland A., Brown C., Wolford H., Johansson M.A., Cetron M.S., Slayton R.B., Friedman C.R. Cruise ship travel in the era of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): a summary of outbreaks and a model of public health interventions. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2022;74:490–497. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciab433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halabi S.F. The origins and future of global health law: regulation, security, and pluralism. Georgetown Law J. 2020;108:1607–1654. [Google Scholar]

- He S.Q. NIMBY behavior in epidemic prevention and control and its governance from the rule of law. J. Hum. Right. 2020;19:192–203. [Google Scholar]

- Hossain T., Adams M., Walker T.R. Role of sustainability in global seaports. Ocean Coast Manag. 2021;202 doi: 10.1016/j.ocecoaman.2020.105435. article no. 105435. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hu Z., Li W. Global health governance on cruise tourism: a lesson learned from COVID-19. Front. Mar. Sci. 2022;9 doi: 10.3389/fmars.2022.818140. article no. 818140. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hyle L.R., Asamoah A.K., Rufer R.T. International health law. Int. Lawyer. 2009;43:825–883. https://scholar.smu.edu/til/vol43/iss2/33 [Google Scholar]

- Kane B., Zajchowski C.A., Allen T.R., McLeod G., Allen N.H. Is it safer at the beach? Spatial and temporal analyses of beachgoer behaviors during the COVID-19 pandemic. Ocean Coast Manag. 2021;205 doi: 10.1016/j.ocecoaman.2021.105533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaul I., Grunberg I., Stern M. United Nations Development Programme. Oxford University Press; Oxford: 1999. Global Public Goods: International Cooperation in the 21st Century; p. 285. [Google Scholar]

- Kieny M.P., Evans D.B., Schmets G., Kadandale S. Health-system resilience: reflections on the ebola crisis in western Africa. Bull. World Health Organ. 2014;92:850. doi: 10.2471/BLT.14.149278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein R.A. Responsible cruise tourism: issues of cruise tourism and sustainability. J. Hospit. Tourism Manag. 2011;18:107–116. doi: 10.1375/jhtm.18.1.107. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Konnoth C. Narrowing tailoring the COVID-19 response. California Law Review Online. 2020;11:193–208. https://scholar.law.colorado.edu/articles/1310/ [Google Scholar]

- Langfitt F. U.K. health workers decry low rate of coronavirus tests for medical staff. 2020. https://www.npr.org/sections/coronavirus-live-updates/2020/04/02/826157269/u-k-health-workers-decry-low-rate-of-coronavirus-tests-for-hospital-staff

- Laskowski A. BU Today; 2020. Coronavirus Is Hitting the Cruise Line Industry Hard.http://www.bu.edu/articles/2020/coronavirus-is-hitting-the-cruise-line-industry-hard/ [Google Scholar]

- Lee T.L. Global health in a turbulence time: a commentary. Asian Journal of WTO and International Health Law and Policy. 2020;15:27–60. [Google Scholar]

- Lim N. Covid-19: implications for contracts under Singapore and English law. Singapore Comparative Law Review. 2020:119–127. [Google Scholar]

- Lin C.F. 2020. COVID-19 and the Institutional Resilience of the IHR(2005): Time for a Dispute Settlement Redesign?https://petrieflom.law.harvard.edu/resources/article/COVID-19-and-the-institutional-resilience-of-the-ihr-2005 [Google Scholar]

- Liu C. Public health and international obligations of states: the case of COVID-19 on cruise ships. Sustainability. 2021;13 doi: 10.3390/su132111604. article no. 11604. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liu-Lastres B., Schroeder A., Pennington-Gray L. Cruise line customers' responses to risk and crisis communication messages: an application of the risk perception attitude framework. Journal of Travel Reseach. 2019;58:849–865. [Google Scholar]

- Li S., Ding J., Zheng X., Sui Y. Beach tourists behavior and beach management strategy under the ongoing prevention and control of the COVID-19 pandemic: a case study of Qingdao, China. Ocean Coast Manag. 2021;215 doi: 10.1016/j.ocecoaman.2021.105974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lo C.F. The Missing operational components of the IHR (2005) from the experience of handling the outbreak of COVID-19: precaution, independence, transparency and universality. Asian Journal of WTO and International Health Law and Policy. 2020;15:1–26. [Google Scholar]

- Matsui S. Pandemic: covid-19 and the public health emergency. Ariz. J. Int. Comp. Law. 2021;38:139–200. http://hdl.handle.net/10150/657902 [Google Scholar]

- Menhat M., Zaideen I.M.M., Yusuf Y., Salleh N.H.M., Zamri M.A., Jeevan J. The impact of Covid-19 pandemic: a review on maritime sectors in Malaysia. Ocean Coast Manag. 2021;209 doi: 10.1016/j.ocecoaman.2021.105638. article no. 105638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milanes C.B., Montero O.P., Cabrera J.A., Cuker B. Recommendations for coastal planning and beach management in Caribbean insular states during and after the COVID-19 pandemic. Ocean Coast Manag. 2021;208 doi: 10.1016/j.ocecoaman.2021.105575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Health . 2020. Press Statement Updates on the Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Situation in Malaysia. chrome-extension://ibllepbpahcoppkjjllbabhnigcbffpi/https://covid-19.moh.gov.my/terkini/022020/situasi-terkini-16-feb-2020/25%20TPM%20-%2016022020%20-%20EN.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Health Labor and Welfare . Labor and Welfare; 2020. About the Current Situation of New Coronavirus Infection and the Response of the Ministry of Health.https://www.mhlw.go.jp/stf/newpage_11118.html [Google Scholar]