Abstract

Aim: To analyse the changing trends in dental manpower production of India since 1920 and its development to date. Methods and Material: The databases consulted were those provided by the Central Bureau of Health Intelligence, Dental Council of India, and Ministry of Health and Family Welfare. Statistical analysis used: Descriptive statistics. Results: In India, dental education was formally established in 1920 when the first dental college was started. Current data revealed that there are 301 colleges nationwide granting degrees in dentistry, with a total of 25,270 student positions offering annually. Both the distribution of dental colleges and of dentists varies among the regions of the country with the greatest concentration in major urban areas, resulting in limited coverage in rural regions. Conclusions: The current scenario indicates that there is lack of systematic planning in the allocation and development of dental colleges in India.

Key words: Dental education, colleges, students, manpower, workforce, dentist to population ratio, India

INTRODUCTION

India has diverse ethnic, linguistic, geographic, religious and demographic features. It is the second most populous country of the world. With a population of 1.2 billion, India has more people than Europe, more than Africa and more than the entire Western Hemisphere1. To serve the oral health needs of this massive population, India has geared up its dental educational infrastructure. At present India has the greatest number of dental colleges in the world2. In addition the dental industry and the education sector have grown tremendously during the past decades.

This study was undertaken to analyse the changing trends in dental manpower production in India since 1920 and its development to date, including the number of dental colleges and distribution of trained professionals nationwide.

Dental education in India

The dental education sector in India provides training at the undergraduate, postgraduate and postdoctoral levels. The first degree, BDS (Bachelor of Dental Surgery), comprises undergraduate training of 4 years followed by 1 year of internship. The students rotate through various dental specialities after the completion of the formal coursework and examinations given during the first four years of the programme3. The curriculum prescribed by the Dental Council of India, a statutory body constituted under the Dentist Act, 1948, guides basic training in most major areas of dental care and is the prerequisite for further training in residency education. Postgraduate training includes residency programmes of 3 years duration, culminating in MDS (Master of Dental Surgery). Also there are 2-year diploma courses in postgraduate training. The National Board of Examinations, an autonomous organisation established by the Government of India, offers a Diploma of the National Board (DNB). This certification is recognised as equivalent to the MDS and is offered at selected hospitals across the country. Nine specialities of dentistry are offered at postgraduate level: prosthodontics, endodontics, orthodontics, oral surgery, periodontics, paedodontics, oral medicine and radiology, oral pathology and public health dentistry. In addition, there are 2-year certificate/diploma courses that are offered for paradental training, such as dental mechanics (dental laboratory technology), dental hygiene and dental assistance4., 5..

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This analysis was based on consultation of data available from public Indian agencies, including the Central Bureau of Health Intelligence, Dental Council of India and the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare. The data regarding dentists registered in various state dental councils across India was obtained from the official website of Central Bureau of Health Intelligence (CBHI). The CBHI is a national nodal institute of the Directorate General of Health Services, Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India. One of its objectives is to maintain and disseminate the annual National Health Profile (NHP). This publication takes into account recent trends in demography, disease profile and available health resources. It contains human resource indicators that provide us with an overview of the availability of trained and specialised medical, dental, nursing and paramedical workforces in the country. It also provides information regarding regional distribution and disparities. The official website of the Dental Council of India (DCI) was used to acquire information regarding various dental institutions across India. The DCI is a statutory body constituted under the Indian Dentists Act, 1948. The official website of DCI provides a search engine for various dental institutions across India, providing the list state wise and post graduation subject wise. The data regarding numbers of dental institutions, number of seats in graduation, and postgraduation courses were retrieved cautiously and entered into a Microsoft Excel spreadsheet for descriptive analysis. A thorough search was done on Google and PubMed to obtain other relevant data. The keywords ‘dental manpower India’, ‘dental workforce India’ and ‘oral workforce India’ were entered into the search engines. All pertinent data were retrieved and scrutinised to procure relevant information. The total retrieved data comprised 12 PubMed indexed articles, 18 articles not indexed in any standardised medical library and 21 news articles. After scrutinising all retrieved data only nine highly relevant articles were included in the final analysis.

RESULTS

Trends in government and private sector share

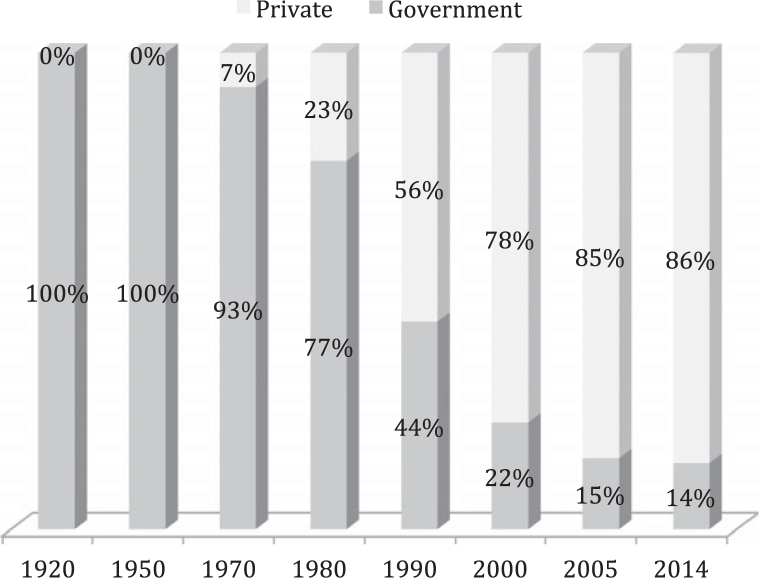

Dental education in India was formally established in 1920 when Dr Rafiuddin Ahmed established the first dental college in Kolkata (formerly known as Calcutta). In 1966, the first private dental institution was established; up to the year 1966 all dental colleges belonged to the government sector. Soon after this period there was a mushrooming in numbers of dental colleges. However, the growth was not uniform in the government and private sectors. Figure 1 shows trends in share of dental colleges by government and private sector from the year 1920 to 2014. In the 1970s, most colleges were government owned (92%) and only a negligible fraction belonged to the private sector (7%)4. After this period there was tremendous growth in the establishment of private dental colleges that led to the present scenario. The current data show that only 14% of the dental colleges are now owned by government and the remainder are in the private sector6.

Figure 1.

The changing ratio in government and private dental colleges in India.

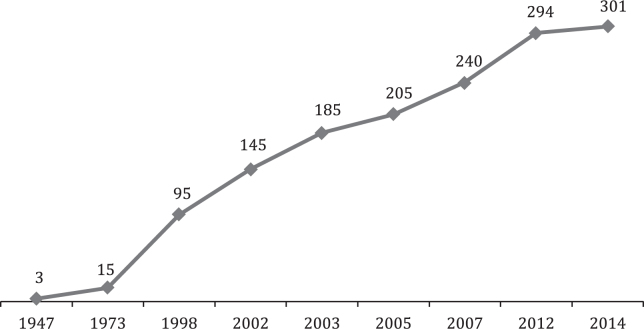

Trends in growth of dental colleges

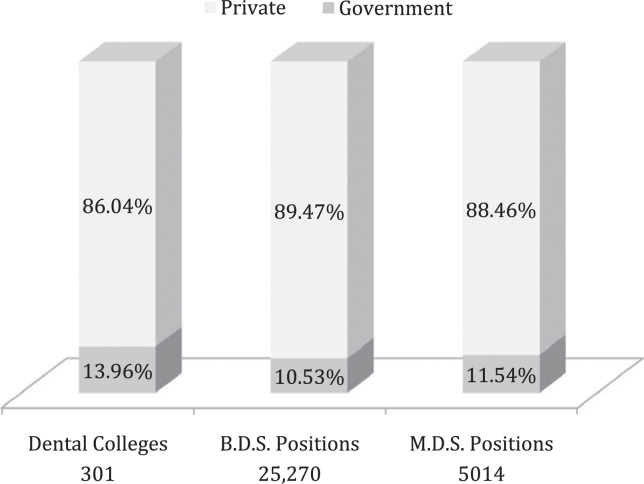

In 1947, when India achieved independence, there were only three dental colleges. In the 50 years after independence, the number grew to 955. The current data show that there are 301 dental colleges in India; of these, 259 belong to the private sector and 42 are government owned. Figure 2 shows the share of government and private sector in dental colleges and in the number of first-year student positions. In the period 1998–2014, 206 new dental colleges were established, resulting in a growth of 215.9% in just 16 years (an increase from 95 to 301 dental colleges)6., 7.. Figure 3 shows trends in growth of dental colleges in India. The growth of dental colleges led to an increase in the number of graduates per year. In the 1960s the number of dental graduates per year was 1,3708, and this has now increased to approximately 15,000.

Figure 2.

Share of government and private sector in dental colleges and in the number of first-year student positions in 2014.

Figure 3.

Trends in the increase of numbers of dental colleges in India.

Available positions for students

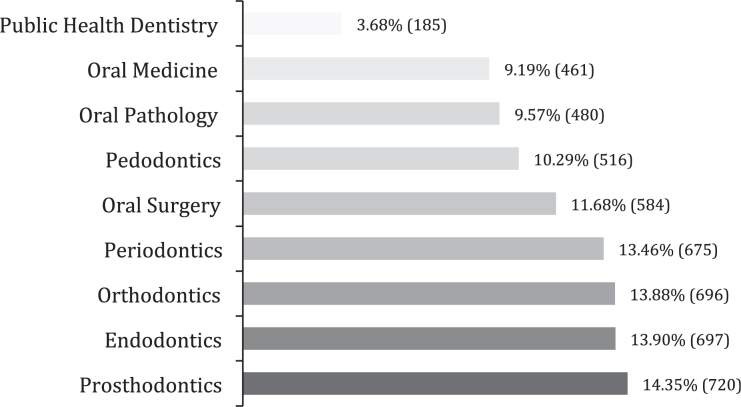

The present data shows that there are a total of 25,270 positions available for students to enter dentistry in India, of which 22,610 (89.47%) are offered by private colleges and 2,660 (10.53%) by the government colleges. Out of the 301 dental colleges, 205 provide postgraduate courses. There are a total of 5,014 positions available for entering postgraduate training. Of which 4,435 (88.46%) are provided by the private sector and 579 (11.54%) by the government sector. The maximum number of postgraduate positions are available in prosthodontics, followed by endodontics, orthodontics and other specialties. Figure 4 provides details of postgraduate positions available in nine branches of dentistry. Postgraduate diploma courses are provided by nine dental colleges and 39 positions are available. A total of 68 dental colleges offer paradental courses in dental mechanics and dental hygiene. Only 1,186 positions are available for dental mechanics and 833 for dental hygiene training. Thirteen colleges offer dental operating room assistant (DORA) training, for which there are 195 positions available6., 7..

Figure 4.

Number of postgraduate positions in nine branches of dentistry in 2014.

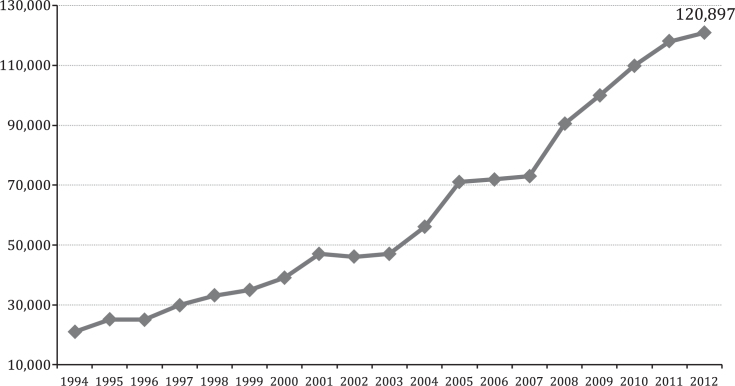

Trends in growth of registered dentists

In the year 1994, only 21,000 dentists were registered in various state dental councils across the country. This figure has gradually increased and current data show that there are 120,897 registered dentists, serving the oral health needs of the population. The growth in numbers of dentists in India is approximately 8% per year9. Figure 5 shows trends in growth of registered dentists in India.

Figure 5.

Trends in the increase of numbers of registered dentists in India.

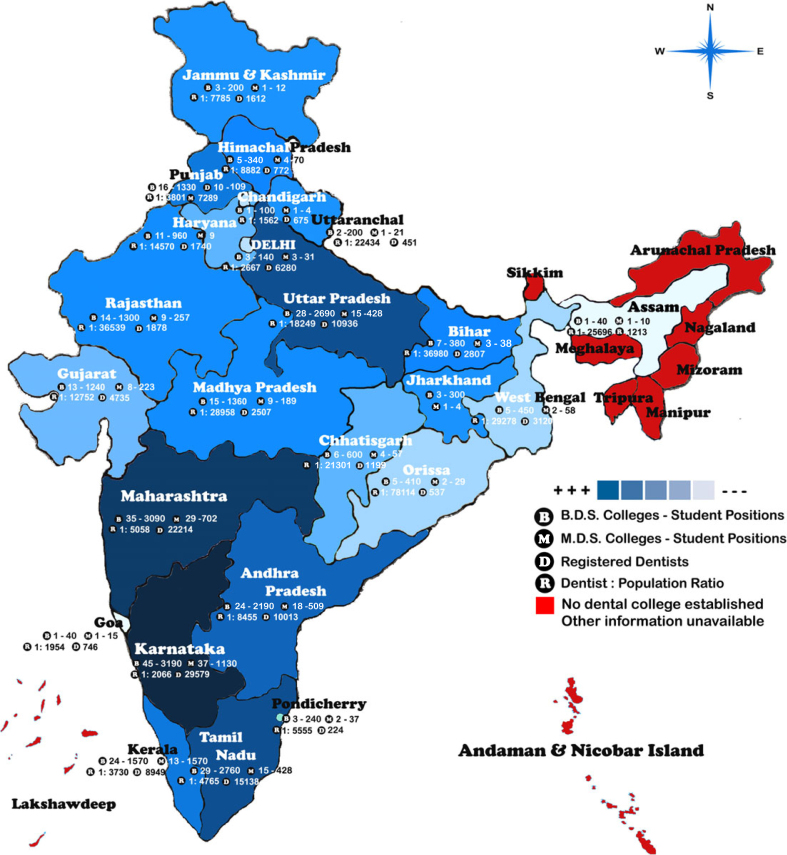

Figure 6 shows the geographic distribution of dental colleges across various states in India. It also shows the number of dental colleges, number of graduate positions available, number of dental colleges offering postgraduate courses and available number of postgraduate positions in each state/union territory. It also shows the number of dentist registered in each state and the state dentist to population ratio.

Figure 6.

Map showing details of dental manpower of India.

Dentist to population ratio

The current data show that in India the dentist to population ratio is 1:99929. The dentist to population ratio has markedly improved from 1960s when it was 1:301,0005. However, there is considerable variation in the distribution of dentists across various states. Some states/union territories, such as Delhi, Karnataka, Maharashtra, Kerala, Tamil Nadu, Punjab, Goa, Chandigarh and Pondicherry, have dentist to population ratios in the range 1:2000–1:5000, while most states/union territories have dentist to population ratios in the range 1:10,000–1:25,000. Some states are totally void of registered dentists.

There is also a misdistribution of dentists across the rural and urban areas of the country. The greatest numbers of dentists practise in urban agglomerations9. Considering that only 25% of dentists work in rural settings8, the rural dentist to population can roughly be estimated as 1:30,000. This contrasts with an urban dentist to population ratio of approximately 1:4,000.

DISCUSSION

Dentistry has expanded exponentially in recent years in India. Notably, in the last 15 years, there has been major expansion of the number of dental colleges and of the number of people who have joined the dental profession. A principal concern, nevertheless, of both professionals and the population at large is the quality of training and the probable shrinking of jobs for dentists in coming years because of an excessive production of dentists and resulting market saturation10.

India exceeds the USA, Brazil and all of Europe in the number of dental colleges and first-year positions for students. In the USA, there are 56 schools of dentistry with approximately 17,800 students and about 4,500 new graduates each year11. In Brazil, there are 191 colleges with approximately 17,000 available student positions in first year and about 10,000 new graduates annually2. Across Europe, there are 177 academic dental colleges and approximately 6,500 students graduate every year12. In India, there are 301 dental colleges and approximately 25,000 available positions for students to enter dentistry and about 15,000 students graduating annually. While the Indian population is increasing by 1.31% per year, the growth in the number of dentists is approximately 8% annually. A similar situation exists in Brazil and China. In Brazil, the number of dentists is increasing by 7% annually, while the population is growing by 1.89% per year2. In China, where the number of dentists is increasing by 4% annually, the population is growing by only 0.9%13.

In the 1990s, there was a rapid expansion of dental education in India, mainly of private colleges. Currently, 86% of the dental schools in India are private colleges. Dental colleges across the country participate in the mainstream of oral health-care delivery system5. Privatisation, in general, has been known to increase the gap between rich and poor, effectively encouraging survival of the richest, which cannot be an acceptable goal of any civilised society. This excessive privatisation has undermined oral health-care services and further limited access by the underprivileged14. One might expect that this escalating number of graduating dentists would address the shortage of dentists in India. However, for monetary reasons, dentists tend to cluster in cities or large towns rather than establishing dental practices in rural areas. Moreover, dental colleges are also concentrated in a few developed states, further worsening the misdistribution. The distribution of dental colleges in India is characterised by excessive geographic inequalities. Forty-five dental colleges exist in the state of Karnataka, whereas services of single institute are unavailable in north-eastern states such as Arunachal Pradesh, Sikkim, Meghalaya, Nagaland, Mizoram, Tripura and Manipur. There is a serious deficiency of dental colleges in the north-eastern states of India, which are most adversely affected by lack of dental professionals.

The distribution of professionals indicates a difference between the more and less developed regions of the nation, resulting in lack of dental assistance for much of the Indian population. In rural areas, the dentist to population ratio ranges from 1:30,000–1:1,00,000. Whereas in most of the developed urban areas the ratio averages to 1:4,000. Other countries also show similar distributions. In Brazil, the dentist to population ratio was reported to be 1:874 but the distribution of dentists was uneven, with average dentist to inhabitant ratios of 1:3,666 in the northern region and 1:800 in the south-eastern region2. In Hong Kong15 and Sri Lanka16 the status of dental practice is similar. One potential way of balancing in the rural–urban inequality could be through integration of dentists into the primary health-care system. The primary health-care system of India has a strong network of health centres and manpower. On March 31, 2011, there were 148,124 subcentres, 23,887 primary health centres (PHCs) and 4,809 community health centres (CHCs) with 31,530 health assistants and 260,083 health workers9. In addition to utilising these paramedical personnel in oral health education and prevention activities, if one dentist is recruited in every PHC and CHC, as suggested by the High-Level Expert Group on Universal Health Coverage17, about 30,000 dentists would have been working in the rural areas in government hospitals. However, the total number of dentists working in government hospitals, both rural and urban, as of January 1, 2012 was 3,8759. The failure of the government to absorb sufficient number of graduating dentists into the primary health-care system partly resulted in mushrooming of private dental clinics. Urban polarisation of private dental practitioners has made dental services entirely inaccessible to rural people18.

In the coming years, with this huge number of dental colleges in India, there should be ample availability of dentists throughout the country. However, there are growing concerns about market saturation and possible shrinkage of jobs in most urban cities of India. An intellectually stimulating environment for professional enrichment, lucrative working conditions and avenues for career growth should be provided to the young dentists19. Policies by the government and dental council can intervene the present situation to protect the fate of future dentists. The pursuit of the oral health of a nation should be steered by ethical principles, and should consider the social, cultural and economic conditions of the population, in order to transform dental practice that would benefit the society.

SUMMARY AND CONCLUSION

In the last 15 years, there has been a major expansion in the number of dental colleges and in the number of people who have joined the dental profession. The current data on dental professionals and dental education in India show that India has 301 colleges granting degrees in dentistry (259 private and 42 public), 25,270 available student positions and approximately 15,000 students graduate annually to give a dentist to population ratio of 1:9,992. However, there is lack of systematic planning and development of dental colleges in India, as is evident by their uneven geographic distribution. Despite India being a nation with one of the greatest number of dental schools and the highest number of graduates annually, we believe that this situation does not appear to have improved the oral health of the majority of the population. The incorporation of dentists into the primary health-care system, as suggested by the High-Level Expert Group on Universal Health Coverage, may help in bridging the rural–urban gap in the dental manpower distribution. Unavailability of robust data on public domains restrict further conclusions.

REFERENCES

- 1.Huab C, Sharma OP. India’s population reality: reconciling change and tradition. At: http://www.prb.org/pdf06/61.3IndiasPopulationReality_Eng.pdf. Accessed: March 4, 2013

- 2.Saliba NA, Moimaz SA, Garbin CA, et al. Dentistry in Brazil: its history and current trends. J Dent Educ. 2009;73:225–231. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Elangovan S, Allareddy V, Singh F, et al. Indian dental education in the new millennium: challenges and opportunities. J Dent Educ. 2010;74:1011–1016. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mahal AS, Shah N. Implications of the growth of dental education in India. J Dent Educ. 2006;70:884–891. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Parkash H, Duggal R, Mathur V. Guidelines for meaningful and effective utilization of available manpower at dental colleges for primary prevention of oro-dental problems in the country. GOI-WHO Collaboration Project; 2007.

- 6.Dental Council of India. College Details. At: http://www.dciindia.org/search.aspx. Accessed: Jan 20, 2014

- 7.Ministry of Health and Family Welfare. Dental colleges in India approved for conducting B.D.S. course. At: http://mohfw.nic.in/showfile.php?lid=138 Accessed: Jan 20, 2014

- 8.Tandon S. Challenges to the oral health workforce in India. J Dent Educ. 2004;68:28–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Central Bureau of Health Intelligence . Central Bureau of Health Intelligence; New Delhi: 2013. National Health Profile 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 10.World Health Organization . World Health Organization; New Delhi: 2007. Not enough here… Too many there… Health workforce of India. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Center for Public Policy and Advocacy . American Dental Education Association; Washington, DC: 2004. Dental Education at-a-Glance. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kravitz SA, Treasure ET. The Liaison Committee of the Dental Associations of the European Union; Cardiff: 2004. EU manual of dental practice, 2004. At: www.eudental.eu/library/104/files/eu_manual_05004-20051104-1148.pdf. Accessed: March 3, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schwarz E, Lo EC, Cai LH. Dental work force in China. J Dent Res. 2001;80:1962. doi: 10.1177/00220345010800110201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Aggarwal A. Strengthening the health care system in India: is privatization the only answer? Editorial. Indian J Community Med. 2008;33:69–70. doi: 10.4103/0970-0218.40869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lo ECM, Wong MC. Geographic distribution of private dentists in Hong Kong in 1989 and 1998. Br Dent J. 1999;186:172–173. doi: 10.1038/sj.bdj.4800054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Silva DD, Brailsford S, Bandara J. Dental workforce planning, Sri Lankan experience. At: http://www.econ.kuleuven.be/eng/tew/academic/prodbel/ORAHS2009/10.pdf Accessed: March 7, 2013

- 17.Srinath R. Planning Commission of India; 2011. High Level Expert Group Report on Universal Health Coverage for India. At: http://planningcommission.nic.in/reports/genrep/rep_uhc2111.pdf Accessed: Nov 12, 2012. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Suresh S. The great divide. Rural–urban gap in oral health in India. J Dent Oro Facial Res. 2012;8:1–6. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Prakash H, Mathur VP, Duggal R, et al. Dental workforce issues: a global concern. J Dent Educ. 2006;70:22–26. [Google Scholar]