Abstract

Purpose: To compare the ability of two active ingredients – sodium fluoride (NaF) and stannous fluoride (SnF2) – to inhibit hydroxyapatite (HAP) dissolution in buffered acidic media. Methods: Two in vitro studies were conducted. HAP powder, which is representative of tooth mineral, was pretreated with: test solutions of NaF or SnF2, 10 g solution per 300 mg HAP powder (Study 1); or NaF or SnF2 dentifrice slurry supernatants, 20 g supernate per 200 mg HAP powder for 1 minute followed by three washes with water, then dried (Study 2). About 50 mg of pretreated HAP was exposed to 25 ml of acid dissolution media adjusted to and maintained at pH 4.5 in a Metrohn Titrino reaction cell. Exposure of HAP to the media results in dissolution and release of hydroxide ion, increasing the pH of the solution. The increase in pH is compensated for by automatic additions of acid to maintain the original pH (4.5) of the reaction cell. Total volume of titrant added after 30 minutes was used to calculate the percentage reduction in dissolution versus non-treated HAP control. Results: Both F sources provided protection against acid dissolution; however, in each study, SnF2-treated HAP was significantly more acid-resistant than the NaF treated mineral. In study 1, at 280 ppm F, representing concentrations of F found in the mouth after in vivo dentifrice use, the reduction in HAP dissolution was 47.7% for NaF and 75.7% for the SnF2-treated apatite (extrapolated). In study 2, the reduction in HAP dissolution was 61.3% for NaF and 92.8% for SnF2-treated samples. Differences in percentage reduction were statistically significant (Paired-t test). Conclusions: Results of these studies demonstrate that both of the fluoride sources tested enhance the acid resistance of tooth mineral and that resistance is significantly greater after treatment with SnF2 compared with treatment of tooth mineral with NaF.

Key words: Erosion, toothwear, toothpaste, fluoride, stannous fluoride

INTRODUCTION

Protection against erosive acid challenge is critical for the prevention of dental erosion. Stannous fluoride (SnF2), a well-known anticaries agent, has also been shown to impart significant resistance to tooth mineral against erosive acid attack1., 2., 3., 4.. This effect is believed to be driven by the strong affinity of stannous ions for the mineral surface on teeth1. In vitro studies, using hydroxyapatite (HAP) powder, were used to demonstrate the mechanism of SnF2 protection against dental erosion. Hydroxyapatite, the primary mineral component of human enamel, provides an efficient means to determine the ability of compounds to attach to and protect tooth mineral against erosive acid dissolution5.

It has been over 60 years since SnF2 was first suggested as an agent for reducing the acid solubility of tooth enamel as a mechanism for the prevention of dental caries6., 7.. Since that time, the effectiveness of SnF2 in lowering the incidence of caries has been shown in numerous clinical trials8. The ability of the stannous ion to deliver enamel solubility reduction was noted in several publications in the early days of research on SnF26., 9., with one perspective being that the clinical effectiveness of the agent was likely dependent on the maintenance of the stannous ion in an active state10. Electron microscopic studies demonstrated that stannous ions could be deposited on intact enamel surfaces11. Other in vitro studies demonstrated the separate but additive protective effects of the stannous and fluoride ions against acid solubility of enamel12. However, the specific mechanism by which this protection was delivered was not clearly established13. Brudevold and co-workers9., 14. found little or no stannous ion uptake on the surface of teeth exposed to a SnF2 dentifrice, while Wachtel12 reported no evidence of significant stannous ion protection using in vitro enamel solubility tests. Meanwhile, Muhler15 demonstrated that daily application of SnF2 dentifrice increased the tin content of enamel, and Manly16 showed that the enamel solubility rate was related to the availability of stannous ion. Despite the differences in opinion regarding a specific mechanism of action, there was little doubt SnF2 was clinically effective in the control of caries. Importantly, the preponderance of evidence suggested that stability of the stannous ion played a major role in reducing the solubility of tooth enamel in acid.

Over the past several decades, new information has come to light regarding both the chemistry of SnF2 and methods for stabilisation of this highly reactive species into oral care products. Stannous fluoride is unstable in aqueous media and above pH 4 undergoes oxidation and hydrolysis reactions resulting in the formation of inactive stannous species and precipitates, leading to significant reductions in caries, gingivitis and dentinal hypersensitivity benefits. To compensate for the loss of stannous ion, dentifrice manufacturers stabilise SnF2 through the use of various formulation modifications, such as exclusion of water, use of chelating agents, such as pyrophosphate, gluconate, gantrez (a copolymer of maleic acid and methyl ether) or phytate, which are able to form soluble stannous complexes, or through the incorporation of another stannous compound, such as stannous chloride or stannous pyrophosphate as a reserve source of stannous ions17. Through careful formulation balancing and performance modelling, manufacturers have developed the ability to deliver products that now provide high levels of both stannous and fluoride ions during product use18.

Owing to their ability to provide high levels of available active, stabilised SnF2 dentifrices have gained significant respect in the dental community for their ability to not only fight caries but also to control plaque19, gingivitis20 and dentinal hypersensitivity21., 22., 23.. More recently, both in vitro1., 2. and in situ clinical studies3., 4. have demonstrated the superior ability of a stabilised SnF2 dentifrice to also protect teeth against erosive acid attack that can lead to dental erosion. Dental erosion is a condition arising from an overexposure of teeth to dietary acids that can result in tooth surface damage. Whereas caries results in loss of subsurface tooth mineral, dental erosion attacks the surface of teeth and can result in irreversible tooth surface loss24. The ability of SnF2 to protect tooth mineral against erosive acid challenges begs the question of whether its anti-erosion mechanism of action is similar to or different from its anti-caries mechanism of action.

The purpose of the current studies was to measure, in the absence of dentifrice components such as emulsifiers, humectants, detergents and flavours, the relative ability of freshly prepared NaF and SnF2 solutions to reduce acid solubilisation of powdered HAP (Study 1) and whether the relative ability of these active ingredients to reduce acid dissolution changes when incorporated into modern dentifrice formulations (Study 2). An in vitro HAP dissolution model was used to measure in vitro dissolution kinetics of pretreated HAP, a synthetic mineral analogue of teeth, under acidic solution conditions.

METHODS

The model uses HAP powder, a synthetic analogue of enamel and dentine, as a test substrate. The HAP powder (BioRad Laboratories, Hercules, CA, USA) was pretreated with a freshly made solution [Study 1: 10 g of NaF or SnF2 solutions (over the range of 12.5–400 ppm F) per 300 mg HAP powder] or dentifrice slurry supernatant (Study 2: 20 g of supernate per 200 mg HAP powder) followed by washing three times with water, then dried. About 50 mg of the pretreated HAP powder was then exposed to 25 ml of acid dissolution media. The pH of the media was adjusted to and maintained at pH 4.5. Exposure of HAP to the media results in dissolution and release of hydroxide ions, which increases the pH of the solution:

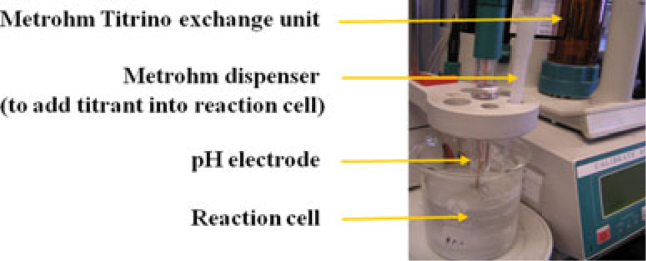

Compensation for increasing pH is made by sequential, automatic additions of 0.05 m lactic acid (Study 1) or dilute (0.1 n) hydrochloric acid (Study 2) to maintain the original pH (4.5) of the reaction cell (Metrohm Titrino – Figure 1; Brinkman Instruments, Riverview, FL, USA). As there is a finite amount of solution present, the rate of dissolution and subsequent amount of titrant added slows over time. The total volume of titrant added after 30 minutes was used to calculate per cent reductions versus control.

Figure 1.

Metrohn Titrino reaction cell system.

Preparation of treatment solutions (Study 1)

For the NaF treatment solutions a stock solution of 1000 ppm F (2.21 g NaF diluted to 1,000 ml) was prepared fresh in a Nalgene volumetric flask (Nalgene, Rochester, NY, USA) using reagent grade NaF powder and deionised, distilled water. Serial dilutions were made from this stock solution to concentrations of 25, 50, 100, 200 and 400 ppm F using deionised, distilled water.

For SnF2 treatment solutions a stock solution of 1,000 ppm F (4.124 g SnF2 diluted to 1000 ml) was prepared fresh in a Nalgene volumetric flask using reagent grade SnF2 powder and deionised, distilled water. Serial dilutions were made from this stock solution to concentrations of 12, 24, 49, 73, 121 and 243 ppm F using deionised, distilled water.

About 300 mg of HAP powder was added to 10 g of each treatment solution and thoroughly mixed for 1 minute to allow reaction between the apatite surfaces and the treatment solutions. Treatment solutions were then filtered and washed a total of three times using deionised, distilled water. The filtrate was recovered, dried and stored until ready for use in the dissolution experiments.

About 50 mg of the pre-treated HAP powder was added to 25 ml of dissolution media (0.10 m lactic acid + 0.15 m NaCl, pH 4.5) in the reaction cell (Metrohm Titrino). Titrant for reaction cell: 0.05 m lactic acid.

Preparation of treatments (Study 2)

Dentifrice slurries were prepared using commercially available dentifrices. Crest Cavity Protection dentifrice (The Procter & Gamble Company, Cincinnati, OH, USA), containing 1,100 ppm F as NaF and Crest Pro-Health dentifrice (The Procter & Gamble Company), containing 1,100 ppm F as SnF2 were used. Dentifrice slurries were prepared by thoroughly mixing one part dentifrice (10.0 g) with three parts (30.0 g) deionised, distilled water for approximately 2 minutes. After mixing, slurries were transferred to a 50 ml Nalgene tube and centrifuged at 12,400 g for 30 minutes to produce a supernatant. Twenty grams of the supernatant were removed for use in the study. Duplicate supernatants were prepared for each test product. About 200 mg of HAP powder was added to 20 g of each supernatant and thoroughly mixed for 1 minute to allow reaction between the apatite surfaces and the treatment. Treated HAP powders were then filtered, and washed a total of three times using deionised, distilled water. The recovered filtrate was freeze dried and stored until ready for use in the dissolution experiments.

About 50 mg of the pretreated HAP powder was added to 25 ml of dissolution media (0.05 m acetic acid, 0.05 m sodium acetate, 0.109 m sodium chloride) pH 4.5, in the reaction cell (Metrohm Titrino). Titrant for reaction cell: 0.10 n hydrochloric acid.

RESULTS

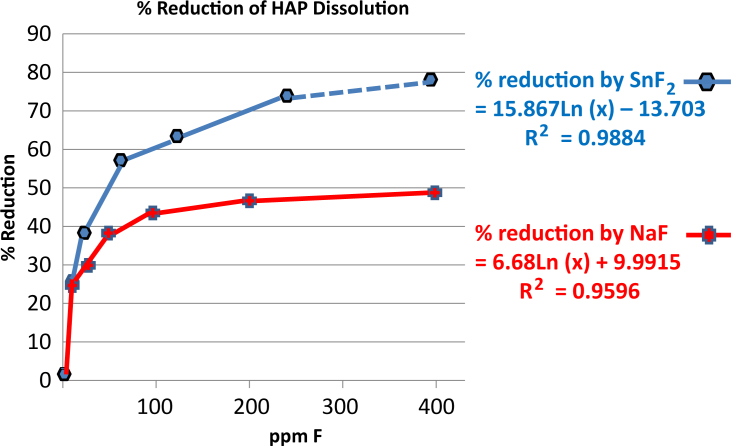

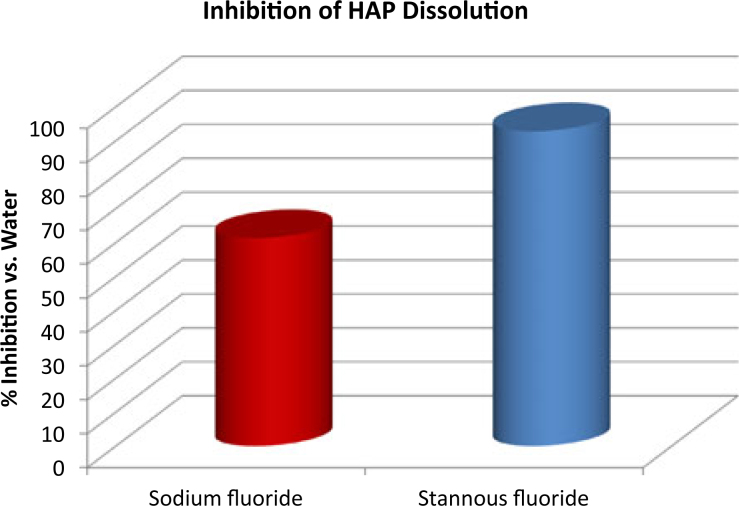

Both NaF and SnF2 provided protection against acid dissolution, with results significantly favouring performance by the SnF2 in each study. These results further demonstrated that the SnF2 remains active in the modern, stabilised formulation, providing a significant improvement over earlier dentifrices that suffered from stability issues. In Study 1, freshly prepared SnF2 and NaF solutions both reduced the dissolution rate of HAP powder compared with a non-treated HAP control. The percentage reduction in dissolution after 30 minutes (Table 1) was correlated with Log[concentration] of each ingredient (Figure 2). For the SnF2 series, % Reduction Y = 15.867Ln[F conc.] − 13.703, R2 = 0.9884; for the NaF series, % Reduction Y = 6.68Ln[F conc.] + 9.9915, R2 = 0.9596. At a given F concentration, e.g. 280 ppm, which represents the expected concentration of F found in the mouth after in vivo dentifrice use, the reduction in HAP dissolution for NaF was 47.6%, while reduction for the SnF2-treated sample was 75.7% (extrapolated – Table 2, Figure 2). In study 2, after 30 minutes of acid exposure (Table 3), the reduction in dissolution for the NaF-treated apatite was 61.3%, while the reduction in HAP dissolution for the stabilised SnF2-treated sample was 92.8% (Table 4, Figure 3). Differences in % reduction were statistically significant (paired t-test).

Table 1.

pH stat data (Study 1) – (a) NaF solutions, (b) SnF2 solutions

| Time (minutes) | Parts per million (ppm) F in solution |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 12.5 | 25 | 50 | 100 | 200 | 400 | |

| (a) | |||||||

| 0.0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 1.0 | 3.45 | 3.28 | 3.14 | 2.80 | 2.36 | 2.35 | 2.39 |

| 2.0 | 5.98 | 5.38 | 5.09 | 4.52 | 3.93 | 3.82 | 3.84 |

| 3.0 | 7.79 | 6.75 | 6.33 | 5.64 | 4.97 | 4.78 | 4.77 |

| 4.0 | 9.15 | 7.72 | 7.20 | 6.41 | 5.70 | 5.44 | 5.41 |

| 5.0 | 10.21 | 8.41 | 7.83 | 6.96 | 6.23 | 5.94 | 5.87 |

| 10.0 | 12.99 | 9.81 | 9.08 | 8.03 | 7.30 | 6.88 | 6.68 |

| 15.0 | 13.74 | 10.22 | 9.49 | 8.40 | 7.68 | 7.26 | 7.02 |

| 20.0 | 14.08 | 10.44 | 9.73 | 8.62 | 7.94 | 7.51 | 7.22 |

| 25.0 | 14.27 | 10.59 | 9.90 | 8.77 | 8.12 | 7.68 | 7.38 |

| 30.0 | 14.39 | 10.70 | 10.03 | 8.88 | 8.25 | 7.80 | 7.49 |

| Time (minutes) | Parts per million (ppm) in solution |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sn | 0 | 38 | 76 | 151 | 227 | 379 | 757 | |

| F | 0 | 12 | 24 | 49 | 73 | 121 | 243 | |

| (b) | ||||||||

| 0.0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 1.0 | 3.39 | 3.37 | 2.83 | 2.49 | 1.88 | 1.52 | 0.94 | |

| 2.0 | 5.76 | 5.34 | 4.49 | 4.02 | 3.31 | 2.61 | 1.61 | |

| 3.0 | 7.43 | 6.56 | 5.53 | 4.95 | 3.91 | 3.30 | 2.06 | |

| 4.0 | 8.67 | 7.39 | 6.23 | 5.57 | 4.42 | 3.76 | 2.27 | |

| 5.0 | 9.62 | 7.98 | 6.72 | 6.01 | 4.70 | 3.99 | 2.41 | |

| 10.0 | 12.09 | 9.02 | 7.56 | 6.72 | 5.26 | 4.52 | 2.85 | |

| 15.0 | 12.79 | 9.35 | 7.89 | 6.99 | 5.53 | 4.77 | 3.08 | |

| 20.0 | 13.12 | 9.55 | 8.09 | 7.17 | 5.69 | 4.92 | 3.23 | |

| 25.0 | 13.31 | 9.68 | 8.23 | 7.30 | 5.81 | 5.04 | 3.35 | |

| 30.0 | 13.43 | 9.78 | 8.33 | 7.40 | 5.90 | 5.13 | 3.45 | |

Figure 2.

Hydroxyapatite dissolution kinetics; comparison of aqueous solutions of SnF2 and NaF.

Table 2.

Results (study 1) – solutions

| NaF solutions | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parts per million (ppm) F in solution | 0 | 12.5 | 25 | 50 | 100 | 200 | 400 |

| Volume of titrant (ml) | 14.39 | 10.70 | 10.03 | 8.88 | 8.25 | 7.80 | 7.49 |

| % Reduction in dissolution | – | 25.7 | 30.3 | 38.3 | 42.7 | 45.8 | 47.9 |

| SnF2 solutions | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parts per million (ppm) in solution | Sn | 0 | 38 | 76 | 151 | 227 | 379 | 757 |

| F | 0 | 12 | 24 | 49 | 73 | 121 | 243 | |

| Volume of titrant (ml) | 13.43 | 9.78 | 8.33 | 7.40 | 5.90 | 5.13 | 3.45 | |

| % Reduction in dissolution | – | 27.2 | 38.0 | 44.9 | 56.1 | 61.8 | 74.3 | |

Table 3.

pH stat data (study 2) – dentifrice

| Time (minutes)* | Water† | NaF† | Stabilised SnF2† |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0.0 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| 1.0 | 1.43 | 0.94 | 0.14 |

| 2.0 | 2.99 | 1.25 | 0.14 |

| 3.0 | 3.60 | 1.41 | 0.16 |

| 4.0 | 4.04 | 1.50 | 0.18 |

| 5.0 | 4.18 | 1.55 | 0.18 |

| 10.0 | 4.54 | 1.70 | 0.22 |

| 15.0 | 4.70 | 1.79 | 0.26 |

| 20.0 | 4.80 | 1.83 | 0.30 |

| 25.0 | 4.83 | 1.88 | 0.33 |

| 30.0 | 4.89 | 1.89 | 0.35 |

Approximate time each measurement was taken.

Each data-point represents an average of three independent runs.

Table 4.

Results (Study 2) – dentifrice

| Test product | Average volume of titrant (ml) | % Reduction in dissolution | t-Test* |

|---|---|---|---|

| Water | 4.89 ± 0.24 | – | A |

| Crest Cavity Protection (NaF) | 1.89 ± 0.13 | 61.3 | B |

| Crest Pro-Health (stabilised SnF2) | 0.35 ± 0.04 | 92.8 | C |

Each mean value grouped according to statistical similarity in Student’s paired t-test.

Figure 3.

Per cent inhibition of hydroxyapatite (HAP) dissolution; SnF2versus NaF dentifrice.

DISCUSSION

When SnF2 dentifrices were originally developed, there was little knowledge regarding the relative benefits of stannous and fluoride ions on anticaries efficacy. Study-to-study differences made it difficult to arrive at a consensus as to the mechanism of action for this unique, metal based ingredient. While one study would detect significant differences in the ability of SnF2 to reduce enamel solubility16, another would not12. Researchers recognised that the mere presence of the compound in a dentifrice did not necessarily mean the product would be effective at protecting the enamel against caries acid attack. Some studies comparing fluoride solutions with and without stannous ions noted no differences in performance, suggesting the acid protection benefit was driven predominantly by the fluoride rather than the stannous ion. Studies by Manly16 demonstrated that in the SnF2 dentifrices he tested, less than 10% of the stannous ions were being used to provide enamel protection. Wachtel12 suggested that this level of stannous ion would be insufficient to provide significant protection to tooth surfaces against a prolonged acid challenge in vitro. These results strongly suggest one reason for the inconsistencies in performance of the original SnF2-containing products was a general lack of understanding and appreciation of the differences in total versus available active in these formulations. It is one thing to put SnF2 into a dentifrice but it can be quite another thing to keep the SnF2 stable within the dentifrice, allow it to release from the dentifrice during use and react with tooth surfaces with high levels of bioavailability.

Stabilisation of the SnF2 has enabled both the long-term viability of dentifrice formulations and the delivery of high levels of bioavailable SnF2. Compared with the original studies of SnF2, where less than 10% of the active was believed to be available, the current studies demonstrate that the marketed SnF2 dentifrice provides protection at least as good as that of a freshly prepared SnF2 solution. The SnF2 dentifrice used in Study 2 was a stabilised SnF2 formulation. Stabilisation of the formula provides significant levels of available active over the projected lifetime of the product – a marked improvement over the original SnF2 dentifrice available in the 1950s.

Cooley11 proposed that the fluoride ion penetrates the enamel surface, while the tin is deposited as a uniform coating on the tooth surface. Jordan25 demonstrated that SnF2 can react with tooth mineral to form a stannous fluorophosphate complex that coats the treated surface. The results of the current studies are in agreement with these early perspectives, clearly demonstrating the deposition of an acid resistant barrier layer onto the HAP. The enhanced protection provided by SnF2 suggests that the outer facing surface is likely composed primarily of stannous, as suggested by Jordan25, with the fluoride component penetrating, or at least positioned toward, the HAP surface11. When NaF is used to treat HAP powder, the reaction product favours formation of fluoridated apatite, with the F− component attaching to the HAP mineral and the Na+ dissolving into solution. With SnF2 treatment, the F again reacts with the HAP, while the Sn portion remains connected to the complex as a protective, barrier shield against acid attack.

Hydroxyapatite powders are particularly useful for modelling dissolution patterns of hard tissue surfaces in the presence of compounds that attach to and protect mineral surfaces against external challenges. In the current studies, powdered apatite was used to demonstrate the ability of SnF2 and NaF to protect the treated HAP against erosive acid dissolution. This type of model is particularly well-suited for understanding mechanisms of action related to dental erosion processes because dental erosion is a condition characterised by direct dissolution of tooth mineral in an acidic environment. Under the conditions of this model, SnF2 provided significantly greater protection against erosive acid attack compared with NaF. This particular set of studies compared only the ability of these two agents to attach to mineral surfaces and protect against direct acid challenges over a 30-minute period. Long-term duration of the acid resistance benefit would presumably depend on the tenacity with which the protective agent adheres to mineral surfaces, along with how completely the surface is coated. A separate study focused on both the deposition and retention of stannous ions onto intact, pellicle-coated human enamel surfaces26, as deposition and retention on pellicle-coated surfaces is important to understanding whether the protective benefits remain under more realistic conditions.

The powdered apatite studies reported here demonstrate the ability of SnF2 to attach to and protect exposed mineral surfaces against acid attack. While it is likely the primary anticaries benefit from SnF2 comes from its ability to fluoridate subsurface tooth mineral, the surface-facing stannous component provides enhanced resistance against dietary, erosive acids that can lead to dental erosion. Although early studies suggested the ability of SnF2 to coat and protect tooth mineral against acid challenge, the inconsistencies in results were most likely caused by the instability of formulations available at the time.

CONCLUSION

Results of the current studies suggest a primary mechanism of action for F is via enhancement of acid resistance of tooth mineral, and that resistance is significantly greater after treatment with SnF2 compared with treatment of tooth mineral with NaF.

Acknowledgements

These studies were funded by The Procter & Gamble Company, Mason, Ohio 45040, USA.

Conflicts of interest

A. A. Baig, S. L. Eversole and M. Lawless are full-time employees at The Procter & Gamble Company, Mason, OH, USA. J. Yan and N. Ji are full-time employees at The Procter & Gamble Company, Beijing, China. R. V. Faller is a retired Principal Scientist from The Procter & Gamble Company, Mason, OH, USA and is now an Associate Professor at the Kornberg School of Dentistry, Temple University, Philadelphia, PA, USA.

REFERENCES

- 1.Faller RV, Eversole SL, Tzeghai GE. Enamel protection: a comparison of marketed dentifrice performance against dental erosion. Am J Dent. 2011;24:205–210. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Faller RV, Eversole SL. Enamel protection from acid challenge – benefits of marketed fluoride dentifrices. J Clin Dent. 2013;24:25–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hooper SM, Newcombe RG, Faller R, et al. The protective effects of toothpaste against erosion by orange juice: studies in situ and in vitro. J Dent. 2007;35:476–481. doi: 10.1016/j.jdent.2007.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bellamy PG, Harris R, Date RF, et al. In situ clinical evaluation of a stabilised stannous fluoride dentifrice. Int Dent J. 2014;64(Suppl. 1):43–50. doi: 10.1111/idj.12102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Barbour ME, Shellis RP, Parker DM, et al. Inhibition of hydroxyapatite dissolution by whole casein: the effects of pH, protein concentration, calcium, and ionic strength. Eur J Oral Sci. 2008;116:473–478. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0722.2008.00565.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Muhler JC, Boyd TM, Van Huysen G. Effect of fluorides and other compounds on the solubility of enamel, dentin, and tricalcium phosphate in dilute acids. J Dent Res. 1950;29:182–193. doi: 10.1177/00220345500290021201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Muhler JC, Nebergall WH, Day HG. Studies on stannous fluoride and other fluorides in relation to solubility of enamel in acid and the prevention of experimental dental caries. J Dent Res. 1954;33:33–49. doi: 10.1177/00220345540330011001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stookey GK. In: Clinical Uses of Fluorides. Wei S, editor. Lea & Febiger; Philadelphia: 1985. Are all fluoride dentifrices the same? pp. 105–131. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brudevold F, Steadman LT, Gardner DE, et al. Uptake of tin and fluoride by intact enamel. JADA. 1956;53:159–164. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.1956.0171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jordan WA. Anticaries technics in non-fluoride areas: topical fluoride treatment. JADA. 1960;60:181–192. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.1960.0045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cooley WE. Reactions of tin (II) and fluoride ions with etched enamel. J Dent Res. 1961;40:1199–1210. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wachtel LW. In vitro comparison of effects of topical stannic fluoride and stannous fluoride solutions on enamel solubility. Arch Oral Biol. 1964;9:439–445. doi: 10.1016/0003-9969(64)90029-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wachtel LW, Strange JR. Examination of acid solubility protection afforded teeth by stannous fluoride dentifrices. J Dent Res. 1965;44:3–9. doi: 10.1177/00220345650440012701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brudevold F. Action of topically applied fluoride. J Dent Child. 1959;26:186–190. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Muhler JC. Stannous fluoride enamel pigmentation evidence of caries arrestment. J Dent Child. 1960;27:157–167. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Manly RS. Stability of stannous fluoride in dentifrices, Caries Symposium Zurich: The Present Status of Caries Prevention by fluorine-containing dentifrices. 1961. 70–78

- 17.Food and Drug Administration. Gingivitis ANPR Federal Register May 29 2003; 68FR 32249

- 18.Baig A, He T. A novel dentifrice technology for advanced oral health protection: a review of technical and clinical data. Compend Contin Educ Dent. 2005;26:4–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bellamy PG, Jhaj R, Mussett AJ, et al. Comparison of a stabilized stannous fluoride/sodium hexametaphosphate dentifrice and a zinc citrate dentifrice on plaque formation measured by digital plaque imaging (DPIA) with white light illumination. J Clin Dent. 2008;19:48–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Archila L, Bartizek RD, Winston JL, et al. The comparative efficacy of stabilized stannous fluoride/sodium hexametaphosphate dentifrice and sodium fluoride/triclosan/copolymer dentifrice for the control of gingivitis: a six-month randomized clinical study. J Periodontol. 2004;75:1592–1599. doi: 10.1902/jop.2004.75.12.1592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schiff T, He T, Sagel L, et al. Efficacy and safety of a novel stabilized stannous fluoride and sodium hexametaphosphate dentifrice for dentinal hypersensitivity. J Contemp Dent Pract. 2006;2:1–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.White DJ, Lawless MA, Fatade A, et al. Stannous fluoride/sodium hexametaphosphate dentifrice increases dentin resistance to tubule exposure in vitro. J Clin Dent. 2007;18:55–59. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.He T, Barker ML, Qaqish J, et al. Fast onset sensitivity relief of a 0.454% stannous fluoride dentifrice. J Clin Dent. 2011;22:46–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ganss C. In: Dental Erosion. From Diagnosis to Therapy. Lussi A, editor. Karger; Basel: 2006. Definition of erosion and links to tooth wear; pp. 9–16. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jordan TH, Wei SH, Bromberger SH, et al. Sn3F3PO4. The product of the reaction of stannous fluoride and hydroxyapatite. Arch Oral Biol. 1971;16:241–246. doi: 10.1016/0003-9969(71)90017-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Khambe D, Eversole SL, Mills T, et al. Protective effects of SnF2 – Part II. Deposition and retention on pellicle coated enamel. Int Dent J. 2014;64(Suppl. 1):11–15. doi: 10.1111/idj.12097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]