Abstract

Objective: Memories of dental pain may influence both subsequent pain experiences during dental treatment and future decisions about whether to go to a dentist. The main aims of this study were to assess memory of pain and pain-related affect induced by tooth restoration. Methods: A total of 39 women who underwent tooth restoration rated their state anxiety before dental treatment, and the intensity and unpleasantness of pain and the emotions they felt immediately after dental treatment. Either 3 months or 6 months later, the participants were asked to recall their state anxiety, the intensity and unpleasantness of pain and the emotions they had felt. Results: Regardless of the length of recall delay, participants accurately remembered both pain intensity and unpleasantness. Although the state anxiety felt before the pain experience was found to be remembered accurately, the positive affect that accompanied pain was underestimated and the negative affect that accompanied pain was overestimated. Positive affect experienced, state anxiety experienced and recalled state anxiety accounted for 32% and 30%, respectively, of the total variance in recalled intensity and unpleasantness of pain. Conclusion: It is concluded that although dental pain is remembered accurately, affective variables, rather than experienced pain, have an effect on memory of pain.

Key words: Dental pain, memory of pain, memory of affect, positive affect, state anxiety

INTRODUCTION

There is evidence that memory of past pain influences subsequent experiences of pain1., 2., 3., and may play a role in the development of chronic pain4., 5.. Moreover, it has been found that memories of painful medical procedures influence the willingness of patients to undergo future painful medical procedures6, and their subsequent decisions about pain stimuli in psychological studies7.

Although the memory of dental pain appears to influence both subsequent experience of pain during dental treatment and future decisions about whether to go to a dentist, there have been only a few studies on the memory of dental pain and the findings of these studies are inconsistent. Some studies have found that the recall of dental pain is overestimated8., 9., 10. and others have found that dental pain is remembered accurately11., 12.. The state anxiety before dental procedures13., 14., immediately after dental procedures8, as well as during pain recall8., 13. have been found to be correlated with recalled pain. Furthermore, recalled state anxiety10 and trait anxiety12 have been correlated with recalled pain, and patients who score high on trait anxiety12 and trait dental anxiety have been found to be less accurate in their recall of pain9. Pain experienced9., 10., 12., 13., 14. and expected pain9., 14. have also have been found to be correlated with recalled pain.

Previous research on memory of dental pain has a number of shortcomings. First, most of the studies have focused on pain induced by invasive procedures such as tooth extraction10., 11., implant insertion8, tooth crown lengthening13 and root canal therapy14. Other studies have assessed the memory of pain induced by a range of different dental procedures12 and dental procedures in general9. Second, with the exception of one study14, the length of the delay between the experience of pain and its recall (the ‘recall delay’) has been relatively short: from 1 week to 3 months. Moreover, although two studies used two different recall delays, it was not possible to investigate the effects of recall delay on the accuracy of the memory of pain in those studies because (i) the pain experienced during or immediately after the dental procedure was not assessed13 or (ii) pain experienced and pain recalled were assessed by two different measures14. Third, only one of the previous studies on memory of dental pain has assessed two pain dimensions (i.e. pain intensity and pain unpleasantness)14. Fourth, only two studies have investigated the memory of affect (or emotion) that accompanied dental pain10., 11..

The main aim of the present study was to assess the memory of pain induced by a less invasive, but very common dental procedure (i.e. tooth restoration). The second aim of the study was to investigate the effect of the length of recall delay on the memory of dental pain. The third aim was to compare memory of pain intensity and pain unpleasantness. The fourth aim was to assess the memory of the affect that accompanies dental pain. The fifth and final aim of the study was to investigate factors that may influence memory of pain (i.e. pain experienced, and both recalled and experienced affect).

METHODS

Participants

A total of 39 women participated in the study. The mean (± SD) age of the participants was 45.15 ± 13.82 years. Participants were recruited in the waiting room of a dentist’s office while they were waiting for their dental appointment. Those patients that were scheduled to have a tooth restored were invited to participate in a questionnaire study about pain that consisted of three phases: the first phase began when individuals agreed to participate in the study; the second phase was conducted immediately after dental treatment; and the third phase was conducted either 3 months or 6 months after dental treatment. The participants were not informed that the third phase of the study would investigate memory of pain.

After giving their written informed consent to participate in the study, the participants were assigned randomly to two experimental groups that differed in terms of the length of the delay between the second and the third phases of the study. The first group consisted of 20 participants who completed the third phase of the study about 3 months after the second phase. The second group consisted of 19 participants who completed the third phase of the study about 6 months after the second phase (Table 1). The research was conducted in full accordance with the World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki and the study protocol was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the Institute of Psychology of Jagiellonian University.

Table 1.

Group means and standard deviations of all the study variables

| Recall delay | N | Recall delay (days) | Pain intensity |

Pain unpleasantness |

State anxiety |

Positive affect |

Negative affect |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Experienced | Recalled | Experienced | Recalled | Experienced | Recalled | Experienced | Recalled | Experienced | Recalled | |||

| 3 | 20 | 94.00 ± 4.84 | 2.55 ± 3.3 | 2.00 ± 1.65 | 2.65 ± 3.01 | 2.05 ± 1.82 | 3.25 ± 2.73 | 2.95 ± 2.78 | 28.56 ± 10.49 | 19.5 ± 10.74 | 13.18 ± 3.17 | 18.76 ± 10.14 |

| 6 | 19 | 189.58 ± 13.36 | 1.16 ± 1.74 | 2.11 ± 2.02 | 1.32 ± 1.63 | 2.53 ± 2.52 | 2.79 ± 2.55 | 3.26 ± 2.56 | 29.95 ± 9.52 | 21.42 ± 8.32 | 12.89 ± 8.7 | 16.21 ± 6.49 |

Measures

The participants rated pain intensity on an 11-point numeric rating scale (NRS), ranging from 0 = ‘no pain’ to 10 = ‘the most intense pain imaginable’. Pain unpleasantness was measured by a similar 11-point NRS, ranging from 0 = ‘not at all unpleasant pain’ to 10 = ‘the most unpleasant pain imaginable’. State anxiety was also measured by an 11-point NRS, ranging from 0 = ‘no anxiety’ to 10 = ‘the most intense anxiety imaginable’. Positive and negative affect were measured by the two, 10-item, mood scales of the Positive and Negative Affect Schedule (PANAS)15. Respondents were asked to rate the extent to which they experienced each particular emotion on a five-point scale: 1 = ‘very slightly or not at all’, 2 = ‘a little’, 3 = ‘moderately’, 4 = ‘quite a bit’ and 5 = ‘very much’.

Design and procedures

The study consisted of three phases, as mentioned above. The first phase began when participants agreed to participate in the study. At that time, they were asked to rate their state anxiety about the pain they would experience as a result of the dental treatment.

The second phase of the study was conducted immediately after the dental procedure. During this phase, participants rated the intensity of the pain and the unpleasantness of the pain they felt at that moment, and the positive and negative emotions they felt at that moment.

At 3 months or 6 months after the second phase (depending on the experimental condition), the participants were asked to rate the state anxiety they had felt during the first phase of the study, the intensity and the unpleasantness of pain they had felt during the second phase of the study and the emotions they had felt during the second phase of the study. It was emphasised that they were being asked to recall and describe how they remembered the anxiety, the pain and the emotions they felt during the previous phases of the study, rather than to recall how they had rated the anxiety, pain and emotions on the same scales in the previous phases of the study.

Statistical analysis

Statistical comparisons were performed using a repeated measures, analysis of variance (anova) design, with length of recall delay (3 months and 6 months) as a between-subject factor and type of rating (experienced and recalled) as a within-subject factor. Separate anovas were conducted for each dependent variable: pain intensity, pain unpleasantness, state anxiety, positive affect and negative affect.

Stepwise multiple regression was performed to determine the degree to which pain memory was predicted by experienced pain intensity or unpleasantness, experienced and recalled state anxiety, and experienced and recalled positive and negative affect. Separate analyses were performed for recalled pain intensity and pain unpleasantness (the dependent variables in the analyses), using forward, stepwise regression. Seven predictor (or independent) variables were tested in each of the two regression analyses. All the analyses were conducted using the STATISTICA data analysis software system version 10 (StatSoft Inc., Tulsa, OK, USA). The level of significance was set at P < 0.05 for rejecting the null hypothesis in all the statistical analyses.

RESULTS

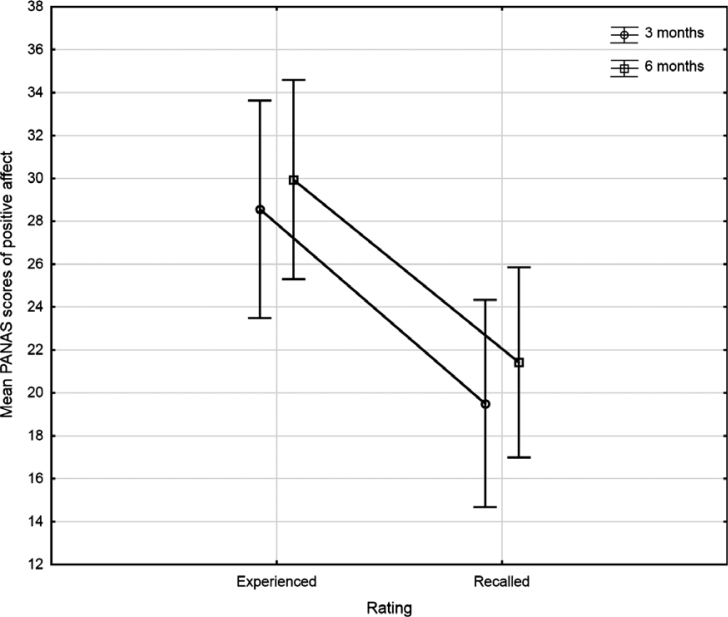

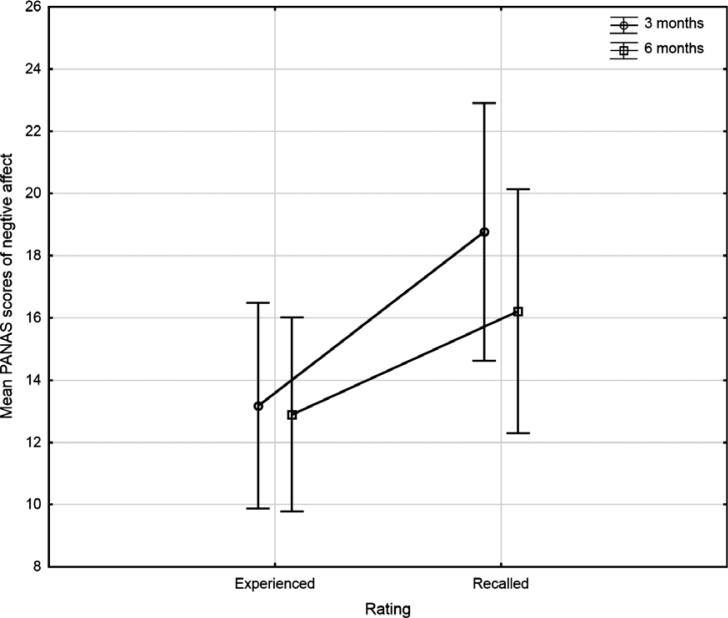

The anova revealed that type of rating had a significant main effect on positive affect (F(1,33) = 23.88, P < 0.001, ŋ2 = 0.42), and negative affect (F(1,34) = 7.13, P < 0.01, ŋ2 = 0.17). These results indicated that participants recalled less positive affect and greater negative affect in the third phase of the study than they reported experiencing in the second phase of the study (Figures 1 and 2). No significant main effect of recall delay was found and no significant interactions were found between the two design factors.

Figure 1.

Positive and Negative Affect Schedule (PANAS) scores of the experienced and recalled positive affect in two study groups, recalling pain 3 months or 6 months after dental treatment. Regardless of the length of recall delay, the subjects recalled less positive affect than they reported when they were in pain.

Figure 2.

Positive and Negative Affect Schedule (PANAS) scores of the experienced and recalled negative affect in two study groups, recalling pain 3 months or 6 months after dental treatment. Regardless of the length of recall delay, the subjects recalled more negative affect than they reported when they were in pain.

The other anovas did not reveal any main or interaction effects for pain intensity, pain unpleasantness or state anxiety, indicating that regardless of the length of the recall delay, pain intensity, pain unpleasantness and state anxiety were recalled accurately.

Given that none of the anovas found significant main effects of recall delay, stepwise multiple regression analyses were performed on the entire sample to examine the extent to which the seven independent variables predicted the two pain recall measures. The first stepwise regression predicted recalled pain intensity – the dependent variable. As seen in Table 2, recalled negative affect was a significant predictor of recalled pain intensity in Steps 1 (β = 0.44), 2 (β = 0.36) and 3 (β = 0.61), but not in Step 4 (β = 0.38), the final step of the analysis. Experienced positive affect was a significant negative predictor of recalled pain intensity in Step 4 (β = −0.34). State anxiety experienced also was a significant negative predictor in Step 4 (β = −0.52) and recalled state anxiety was a marginal, positive predictor (β = 0.46). The Step 4 variables accounted for 32% of the total variance in recalled pain intensity.

Table 2.

Results of the forward stepwise multiple regression analysis predicting the recalled intensity of pain

| Independent variables | β | t | P | R2 | F | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Step 1 | Recalled negative affect | 0.44 | 2.81 | 0.01 | 0.17 | 7.89 | 0.01 |

| Step 2 | Recalled negative affect | 0.36 | 2.33 | 0.05 | |||

| Positive affect experienced | −0.29 | −1.84 | 0.08 | 0.22 | 5.92 | 0.01 | |

| Step 3 | Recalled negative affect | 0.61 | 2.83 | 0.01 | |||

| Positive affect experienced | −0.29 | −1.87 | 0.07 | ||||

| State anxiety experienced | −0.34 | −1.62 | 0.12 | 0.26 | 5.02 | 0.01 | |

| Step 4 | Recalled negative affect | 0.38 | 1.55 | 0.13 | |||

| Positive affect experienced | −0.34 | −2.27 | 0.05 | ||||

| State anxiety experienced | −0.52 | −2.32 | 0.05 | ||||

| Recalled state anxiety | 0.46 | 1.88 | 0.07 | 0.32 | 4.95 | 0.01 |

The second stepwise regression examined the ability of the seven independent variables to predict recalled unpleasantness of pain (Table 3). Experienced positive affect (β = −0.43) and state anxiety experienced (β = −0.58) were significant, negative predictors of recalled unpleasantness of pain in Step 4, and recalled state anxiety was a marginally significant, positive predictor (β = 0.45). The Step 4 variables accounted for 30% of the total variance in recalled unpleasantness of pain.

Table 3.

Results of the forward stepwise multiple regression analysis predicting the recalled unpleasantness of pain

| Independent variables | β | t | P | R2 | F | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Step 1 | Positive affect experienced | −0.44 | −2.79 | 0.01 | 0.17 | 7.8 | 0.01 |

| Step 2 | Positive affect experienced | −0.42 | −2.71 | 0.01 | |||

| Recalled state anxiety | 0.25 | 1.6 | 0.12 | 0.2 | 5.36 | 0.01 | |

| Step 3 | Positive affect experienced | −0.47 | −3.24 | 0.01 | |||

| Recalled state anxiety | 0.6 | 2.83 | 0.01 | ||||

| State anxiety experienced | −0.49 | −2.28 | 0.05 | 0.3 | 5.78 | 0.01 | |

| Step 4 | Positive affect experienced | −0.43 | −2.84 | 0.01 | |||

| Recalled state anxiety | 0.45 | 1.84 | 0.08 | ||||

| State anxiety experienced | −0.58 | −2.55 | 0.05 | ||||

| Recalled negative affect | 0.28 | 1.16 | 0.26 | 0.3 | 4.72 | 0.01 |

DISCUSSION

The major finding of the study is that dental pain intensity and unpleasantness were remembered accurately in the present sample. These findings are in line with the results of previous research showing that past dental pain is remembered accurately11., 12.. However, the results of the present study are contrary to the results of previous research showing that the recalling of dental pain is overestimated8., 9., 10.. However, unlike the previous studies on memory of the pain induced by invasive procedures8., 10., 11., 13., 14., or other dental procedures9., 12., the present study assessed memory for pain induced by a single, less invasive dental procedure (i.e. tooth restoration).

Although dental pain was found to be remembered accurately in the present study, positive affect was underestimated and negative affect was overestimated. These findings are consistent with the results of a previous study on memory of dental pain that found the mood that accompanied painful experiences was remembered as being more negative than it actually was11. In contrast, state anxiety, which is also an affective variable, was remembered accurately in the present study. However, participants recalled the state anxiety they felt before the pain experience, and the positive and negative affect that accompanied pain. These findings suggest that although memory of the positive and negative affect accompanying pain is distorted, memory of anxiety preceding the experience of pain is accurate.

The length of recall delay had no effect on the memory of either pain or affect. Previous studies on memory of dental pain found that the length of delay between the experience of pain and its recall was an important factor influencing the memory of pain13., 14.. Unlike the present study, however, these other studies used within-subject designs, different time-intervals of recall delay and their designs did not allow them to compare experienced and recalled pain. It is possible (i) that the comparison of pain recall at longer recall delays than used in the present study would reveal an influence of the length of recall delay on the memory of dental pain and affect, or (ii) that the results of the studies using a within-subject design might have been biased by repeated pain recall13., 14..

In light of the present results, dental pain appears to be remembered accurately. However, pain experienced did not influence the memory of pain in the present study. Positive affect experienced and state anxiety experienced were found to be the best single, negative predictors of both recalled pain intensity and unpleasantness. Recalled state anxiety was found to be a marginally significant, positive predictor of both recalled pain intensity and unpleasantness. Together with recalled negative affect (which was not a significant predictor in the final steps of regression analyses) they accounted for 32% of the total variance in recalled pain intensity and 30% of the total variance in recalled unpleasantness of pain.

The effect of both experienced and recalled state anxiety on recalled pain in the current study is consistent with the results of previous studies on memory of dental pain. The state anxiety felt before dental procedures13., 14. as well as recalled state anxiety10 have been found to be correlated with recalled pain. However, unlike the results of the present study, previous studies also reported a correlation between experienced pain and recalled pain9., 10., 12., 13., 14.. Moreover, the present study is the first to show that positive affect may have a significant effect on the memory of dental pain.

It should be noted that the experienced variables (state anxiety and positive affect) were found to be negative predictors of recalled pain, while recalled anxiety was positive predictor of recalled pain in the current study. This suggests that recalled affect may have a different effect on memory of pain than experienced affect has on recollection of pain.

Some limitations of the present study should be acknowledged. First, only dental pain induced by tooth restoration was studied and the results may not be generalisable to other types of dental pain. Second, only females participated in the study and, in view of gender differences in pain perception, the results may not be generalisable to males. Third, recall delays that are different from those examined in this study (i.e. 3 months and 6 months), may yield different results.

The present study appears to be the first to assess the memory of pain induced by tooth restoration, and the first to attempt to determine the effect of positive affect on memory of dental pain. The study found that both the intensity and the unpleasantness of pain were remembered accurately, regardless of the length of the recall delay. Although the state anxiety reported before the experience of pain was found to be remembered accurately, positive affect that accompanied the pain was underestimated and negative affect that accompanied the pain was overestimated. The most important finding of the present study seems to be the fact that pain experienced did not predict recalled pain. Both recalled intensity and unpleasantness of pain were predicted by experienced positive affect, experienced state anxiety and recalled state anxiety. In other words, although dental pain is remembered accurately, affective variables, rather than experienced pain, had an effect on memory of pain.

Acknowledgements

I thank Maria Krzemień, Patryk Mazurkiewicz, and Niwad Putteeraj for their assistance with the preparation of the study materials and data collection. The study was funded by the Faculty of Philosophy of the Jagiellonian University. I have no conflicts of interest.

Conflict of interest

None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Chen E, Zeltzer LK, Craske MG, et al. Children’s memories for painful cancer treatment procedures: implications for distress. Child Dev. 2000;71:933–947. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gedney JJ, Logan H. Pain related recall predicts future pain report. Pain. 2006;121:69–76. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2005.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Noel M, Chambers CT, Mcgrath PJ, et al. The influence of children’s pain memories on subsequent pain experience. Pain. 2012;153:1563–1572. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2012.02.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tasmuth T, Kataja M, Blomqvist C, et al. Treatment-related factors predisposing to chronic pain in patients with breast cancer – a multivariate approach. Acta Oncol. 1997;36:625–630. doi: 10.3109/02841869709001326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tasmuth T, Von Smitten K, Hietanen P, et al. Pain and other symptoms after different treatment modalities of breast cancer. Ann Oncol. 1995;6:453–459. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.annonc.a059215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Redelmeier DA, Katz J, Kahneman D. Memories of colonoscopy: a randomized trial. Pain. 2003;104:187–194. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3959(03)00003-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kahneman D, Fredrickson BL, Schreiber CA, et al. When more pain is preferred to less: adding a better end. Psychol Sci. 1993;4:401–405. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Eli I, Schwartz-Arad D, Baht R, et al. Effect of anxiety on the experience of pain in implant insertion. Clin Oral Implants Res. 2003;14:115–118. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0501.2003.140115.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kent G. Memory of dental pain. Pain. 1985;21:187–194. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(85)90288-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mcneil DW, Helfer AJ, Weaver BD, et al. Memory of pain and anxiety associated with tooth extraction. J Dent Res. 2011;90:220–224. doi: 10.1177/0022034510385689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Beese A, Morley S. Memory for acute pain experience is specifically inaccurate but generally reliable. Pain. 1993;53:183–189. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(93)90079-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rocha EM, Marche TA, Von Baeyer CL. Anxiety influences children’s memory for procedural pain. Pain Res Manag. 2009;14:233–237. doi: 10.1155/2009/535941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Eli I, Baht R, Kozlovsky A, et al. Effect of gender on acute pain prediction and memory in periodontal surgery. Eur J Oral Sci. 2000;108:99–103. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0722.2000.00777.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gedney JJ, Logan H, Baron RS. Predictors of short-term and long-term memory of sensory and affective dimensions of pain. J Pain. 2003;4:47–55. doi: 10.1054/jpai.2003.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Watson D, Clark LA, Tellegen A. Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: the PANAS scales. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1988;54:1063–1070. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.54.6.1063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]