Abstract

Objectives: The aim of this interventional programme was to educate children undergoing treatment at the haemato-oncology department in how to improve their oral hygiene skills. Methods: Children (and their parents) treated at the haemato-oncology department for haematological malignancies and disorders were educated and instructed in how to improve their dental oral hygiene skills. Instructions, demonstration and practice of toothbrushing techniques, as well as interproximal cleaning, were carried out in three separate sessions. In each session, toothbrushing skills were evaluated using the Ashkenazi index to assess improvement in oral hygiene skills over time. Four assessments were performed and recorded for each participant: before the initial explanation; immediately following the explanation; and 3 and 6 weeks following the first visit. Results: Overall, 52 children were enrolled in the programme. The first toothbrushing performance skill evaluation revealed a low score of 10.44 out of a total of 40; this was significantly increased, following the instruction session, to 33.02 (P < 0.001). This improvement was maintained at the follow-up visits at 3 weeks (35.09 ± 6.3) and 6 weeks (36.34 ± 8.3). Following the instructions, a significant increase was accomplished in both ‘reach’ and ‘stay’ components of the score, to 18.44 out of 20 for ‘reach’ and 17.9 out of 20 for ‘stay’ at the last visit (P < 0.01). Conclusions: Individual supervised toothbrushing education, including a methodological toothbrushing technique, appears to be very effective. Educating medically compromised high-risk patients, such as hospitalised children, might be a good way to improve oral health and prevent future disease in this population.

Key words: Plaque, gingival health, education, prevention

INTRODUCTION

Dental caries is inescapably the most prevalent disease of young children in most countries1. Despite its decreasing prevalence in schoolchildren, dental caries is still an important public health problem2. In addition, periodontal disease is a condition that might be sometimes be underestimated and underdiagnosed among children and adolescents3., 4., 5..

Several investigations have found that a school-based dental programme offering screening, education and dental referral is effective at improving oral health among children1., 6., 7., 8.. Efforts involving oral prevention programmes that incorporate supervised toothbrushing and use of toothpaste with fluoride have been shown to be effective in reducing dental caries in children9., 10.. The results suggest that the adoption of this practice can increase the effectiveness of such programmes in more vulnerable individuals. Useful information for evaluating and reorienting school-based supervised toothbrushing programmes was obtained, suggesting a significant decline in dental caries in a broader population, which can represent a substantial reduction of dental care needs through training auxilliary personnel operating in dental public services10.

Most oral hygiene programmes are aimed at elementary schoolchildren11. The supervision of toothbrushing at school has been recommended because some parents have a low level of knowledge and understanding of the importance of oral hygiene techniques12.

There is limited literature on oral health care for hospitalised children; however, generalised oral health care is often neglected in hospitalised children13. Most nursing literature focuses on the care of oncology patients13. Several studies have concluded that the focus on a child’s primary medical condition can lead to neglect in other health areas13., 14., 15.. The authors stated that unmet oral health needs of medically compromised children can impact general health and quality of life, and recommended an increase in hospital-based dental services and oral health education of providers13., 14., 15.. In children treated at a haemato-oncology department for haematological malignancies and disorders, both the disease and its treatment might radically change the environmental conditions in the oral cavity and thus it seems highly important to make an effort to improve and maintain oral hygiene in this group of children during their hospital stay.

The aim of this interventional programme was to educate children at a haemato-oncology department in improving their oral hygiene skills.

METHODS

During a 4-month period, trained oral health providers from the Department of Periodontology at the Rambam Health Care Campus visited the Haemato-oncology Department at this hospital three times a week. During each visit, children (and their parents) treated at the haemato-oncology department for haematological malignancies and disorders (both daycare outpatients and hospitalised patients) were educated and instructed in how to improve their dental oral hygiene skills. Parents of children in the younger age groups were invited to attend the demonstration and received instruction on how their child should brush their teeth as they are usually involved with patients’ oral home care. We also recommended supervised toothbrushing until the child reached the age of 7. Instructions, demonstration and practice of toothbrushing techniques, as well as interproximal cleaning, were given to the children (and their parents) in three separate sessions (3 weeks apart). Oral health measures (toothbrush, toothpaste, dental floss, etc.) were provided to the children at no cost (courtesy of GABA-Colgate Israel, Petah Tikva, Israel). The toothbrushes used were Elmex (GABA International AG, Therwil, Switzerland), which were given, as appropriate, according to the age of the child. In each session, toothbrushing skills were evaluated using the Ashkenazi index to assess the improvement in oral hygiene skills over time16., 17.. The Ashkenazi index is based on the ability to perform effective toothbrushing based on two criteria: placement of the toothbrush on each tooth segment to be brushed (‘reach’); and completion of enough strokes on each segment (‘stay’). The Ashkenazi index has previously been reported and validated16., 17.. Overall, four assessments were performed and recorded for each participant: before the initial explanation; immediately following the explanation; and 3 and 6 weeks following the first visit. Three trained oral health providers (the three authors) were included in this study and they were calibrated before the study commenced.

Data were collected and tabulated for analysis. Descriptive statistics was initially performed. To compare baseline brushing skill with the follow-up values, a Student’s paired t-test was also used. A 5% significance level was considered statistically significant.

The work was conducted in accordance with the World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki; the project was waived by the Institutional Ethical Review Board because of the nature of the programme. Verbal consent was obtained from the parents or guardians of all participants involved in the study before enrolment.

RESULTS

Overall, 52 children were enrolled in the programme. There were 28 (53.8%) male subjects and 24 (46.2%) female subjects, with an average age of 12.6 ± 4.9 (range 5–20) years; 35 (67.3%) were of Arab origin and 17 (32.7%) of Jewish origin.

All 52 attended the first follow-up visit, 3 weeks after the initial visit; however, eight failed to attend the last follow-up visit at 6 weeks.

The first toothbrushing performance skill evaluation revealed a low score of 10.44 (5.02 ± 3.5 for the maxilla and 5.42 ± 4.6 for the mandible), out of a total of 40, which was significantly increased, following the instruction session, to 33.02 (16.27 ± 5.5 for the maxilla and 16.75 ± 5.1 for the mandible; P < 0.001). This improvement was maintained at the follow-up visits at 3 weeks (35.09 ± 6.3) and 6 weeks (36.34 ± 8.3). Figure 1 depicts the toothbrushing performance skill evaluation scores for the different time points. The 6-week follow-up scores reached the highest achievable score of 40.

Figure 1.

Toothbrushing performance skill evaluation scores at the different study time points.

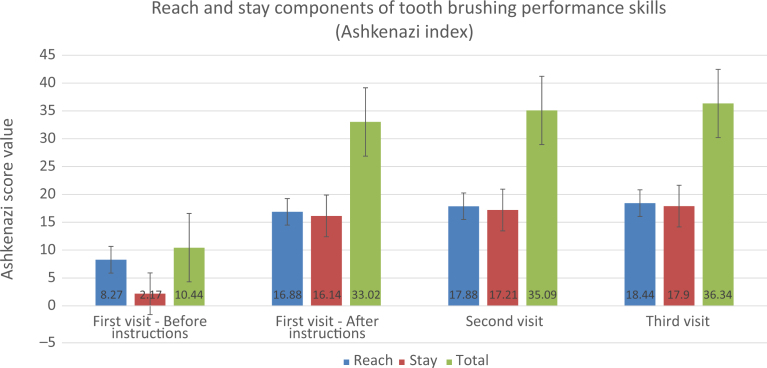

When the results were divided into the ‘reach’ and the ‘stay’ components it was observed that, at baseline, both scores were very low; however, the ‘stay’ component was mostly deficient with an average initial score of 2.17 ± 3 out of 20 (Figure 2). Nevertheless, following the instructions given, a significant increase was accomplished in both ‘reach’ and ‘stay’ components, up to a level of 18.44 out of 20 for ‘reach’ and 17.9 out of 20 for ‘stay’ at the last visit (P < 0.01; Figure 2). No differences in improvement were observed between the different age groups.

Figure 2.

The ‘Reach’ and ‘Stay’ components of toothbrushing performance skills.

DISCUSSION

Although dental caries and periodontal diseases are multifactorial, it is recognised that dental plaque is an important mediating factor for these diseases18., 19..

Efforts involving oral prevention programmes, which incorporate supervised toothbrushing and use of toothpaste with fluoride, have been shown to be effective in reducing dental caries in children20. Even though oral health is recognised as being an essential part of overall health, it has too often been overlooked and neglected13. When it comes to removing dental plaque, appropriate toothbrushing is the most effective way to clean bacterial plaque and debris from the tooth surfaces21. It has been previously established that it is important to create good habits at an early age to prevent caries22. This study was a pilot study using a pre–post test design in which interest focused primarily on comparing toothbrushing skills in children before and after standardised toothbrushing education. The fact that the postinstruction examinations of the participants’ skills was performed just several weeks after the educational session might make it seem less significant, but the aim was to evaluate the participants’ initial perception and understanding of the information that was provided to them. The finding that improvement in the toothbrushing skills scores remained stable over the 6 weeks of follow-up is encouraging; however, it should be remembered that occasional re-enforcement and re-instruction will probably be needed to maintain good performance of oral hygiene over time19. Previous results of studies assessing toothbrushing performance using the same index (the Ashkenazi index) revealed the same magnitude of improvement in healthy children16., 17.; however, the ability to change and improve oral care, even during a state of a life-threatening disease, is highly promising and should guide us when dealing with medically compromised high-risk patients. Obviously, a long-term follow-up of the brushing skills, as well as the results in terms of caries and periodontal disease prevalence, will further elucidate the educational benefit of this suggested programme.

Hospital personnel, especially in hospitals with dental departments, are in a unique position (given that they play such a significant role in the delivery of health care) to contribute to the identification, care and prevention of oral health problems in children13. A proposed plan for hospitals, such as that presented here, which can contribute to oral health improvement in children, includes three very basic components: assessment; oral care; and education. These interventions are far from being novel, but there may be a gap between the theory and practice of oral care for hospitalised patients13. Nursing and other supportive hospital personnel often focus on patient teaching, yet oral health is an area that is probably low on the list of topics to cover, if not off the radar screen entirely. Areas that might need to be covered include cavity prevention techniques, such as brushing and limiting sugar in the diet; regular dental visits; and oral injury prevention23., 24.. Inadequate knowledge may be a leading barrier to good oral health, and health-care professionals, such as nurses, can play an important role in providing this knowledge13., 25..

When referring to children hospitalised at the haemato-oncology department for haematological malignancies and disorders, it should be remembered that both the disease and its treatment might jeopardise oral health conditions26. The combination of damaged immunoregulatory mechanisms, together with lower motivation for oral hygiene and the high risk for oral mucositis during intensive multidrug chemotherapy, might result in profound deterioration in oral health26. In order to lower the risk of such complications, patients should take special care of their oral hygiene27., 28.. Oral complications may also influence the modifications of chemotherapy by increasing the probability of prolonged in-patient treatment and the financial resources required for treatment of paediatric cancer patients29. Therefore, throughout the process of treatment, children and parents should be subject to special care of the interdisciplinary treatment team26.

All children should receive professional dental care as their primary and permanent dentition develops. Prevention, early detection and management of dental problems can be attended to, which will serve to improve a child’s oral and overall health30. A well developed plan of care can contribute to evidence-based practice for guiding this important, yet often neglected, aspect of care13.

Follow-up on oral care performance at home between the meetings was beyond the scope of this work. Future programmes and studies should focus also on adherence and compliance to the recommended oral care instructions at home; this could be undertaken either by self-reported means or by assessment of periodontal soft tissue inflammation31., 32..

CONCLUSIONS

Individual supervised toothbrushing education, including a methodological toothbrushing technique, appears to be very effective. Educating medically compromised high-risk patients, such as hospitalised children, might be a good way to improve oral health and prevent future disease in this population.

Acknowledegments

The program was supported by GABA-Colgate Israel.

Competing Interest

The authors have no competing interest related to this work.

REFERENCES

- 1.Livny A, Vered Y, Slouk L, et al. Oral health promotion for schoolchildren – evaluation of a pragmatic approach with emphasis on improving brushing skills. BMC Oral Health. 2008;31:4. doi: 10.1186/1472-6831-8-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Petersen PE. The World Oral Health Report 2003: continuous improvement of oral health in the 21st century – the approach of the WHO Global Oral Health Programme. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2003;31(Suppl 1):3–24. doi: 10.1046/j..2003.com122.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Demmer RT, Papapanou PN. Epidemiologic patterns of chronic and aggressive periodontitis. Periodontol. 2010;2000:28–44. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0757.2009.00326.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Levin L, Baev V, Lev R, et al. Aggressive periodontitis among young Israeli army personnel. J Periodontol. 2006;77:1392–1396. doi: 10.1902/jop.2006.050323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Levin L, Einy S, Zigdon H, et al. Guidelines for periodontal care and follow-up during orthodontic treatment in adolescents and young adults. J Appl Oral Sci. 2012;20:399–403. doi: 10.1590/S1678-77572012000400002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Collins E, Fair N, Dickinson A, et al. Collaboration between primary and secondary/tertiary services in oral health. Primary Health Care. 2009;19:35–39. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Melvin CS. A collaborative community based oral program for school-age children. Clin Nurse Spec. 2006;20:18–22. doi: 10.1097/00002800-200601000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Livny A, Sgan-Cohen HD. A review of a community program aimed at preventing early childhood caries among Jerusalem infants–a brief communication. J Public Health Dent. 2007;67:78–82. doi: 10.1111/j.1752-7325.2007.00015.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Curnow MM, Pine CM, Burnside G, et al. A randomised controlled trial of the efficacy of supervised toothbrushing in high-caries-risk children. Caries Res. 2002;36:294–300. doi: 10.1159/000063925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Frazao P. Effectiveness of the bucco-lingual technique within a school-based supervised toothbrushing program on preventing caries: a randomized controlled trial. BMC Oral Health. 2011;11:11. doi: 10.1186/1472-6831-11-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Do TTH, Lindmark U, Do QT, et al. Effectiveness of oral hygiene after supervised tooth-brushing education in six-year-old children at a primary school in Vietnam. J Behav Health. 2012;1:279–285. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kolawole KA, Oziegbe EO, Bamise CT. Oral hygiene measures and the periodontal status of school children. Int J Dent Hygiene. 2011;9:143–148. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-5037.2010.00466.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Blevins JY. Oral health care for hospitalized children. Pediatr Nurs. 2011;37:229–235. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Saunders C, Roberts E. Dental attitudes, knowledge, and health practices of parents of children with congential heart disease. Arch Dis Child. 1997;76:539–540. doi: 10.1136/adc.76.6.539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nicopoulos M, Brennan MT, Kent ML, et al. Oral health needs and barriers to dental care in hospitalized children. Spec Care Dentist. 2007;27:206–211. doi: 10.1111/j.1754-4505.2007.tb00348.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Levin L, Marom Y, Ashkenazi M. Brushing skills and plaque reduction using single- and triple-headed toothbrushes. Quintessence Int. 2012;43:525–531. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Telishevesky YS, Levin L, Ashkenazi M. Assessment of parental tooth-brushing following instruction with single-headed and triple-headed toothbrushes. Pediatr Dent. 2012;34:331–336. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Loe H. Oral hygiene in the prevention of caries and periodontal disease. Int Dent J. 2000;50:129–139. doi: 10.1111/j.1875-595x.2000.tb00553.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kwon T, Levin L. Cause-related therapy: a review and suggested guidelines. Quintessence Int. 2014;45:585–591. doi: 10.3290/j.qi.a31808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jackson RJ, Newman HN, Smart GJ, et al. The effects of a supervised toothbrushing program on the caries increment of primary school children, initially aged 5–6 years. Caries Res. 2005;39:108–115. doi: 10.1159/000083155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Okada M, Kuwahara S, Kaihara Y, et al. Relationship between gingival health and dental caries in children aged 7–12 years. J Oral Sci. 2000;42:151–155. doi: 10.2334/josnusd.42.151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Alm A, Wendt LK, Koch G, et al. Oral hygiene and parent-related factors during early childhood in relation to approximal caries at 15 years of age. Caries Res. 2008;42:28–36. doi: 10.1159/000111747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Levin L. Prevention–the (sometimes-forgotten) key to success. Quintessence Int. 2012;43:789. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Levin L, Zadik Y. Education on and prevention of dental trauma: it’s time to act! Dent Traumatol. 2012;28:49–54. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-9657.2011.01060.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Foster H, Fitzgerald J. Dental disease in children with chronic illness. Arch Dis Child. 2005;90:703–708. doi: 10.1136/adc.2004.058065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pels E, Mielnik-Błaszczak M. Oral hygiene in children suffering from acute lymphoblastic leukemia living in rural and urban regions. Ann Agric Environ Med. 2012;19:529–533. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Peterson DE. New Strategies for Oral Mucositis Management in Cancer Patients. J Support Oncol. 2006;4(Suppl 1):9–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mielnik-Błaszczak M, Krawczyk D, Kuc D, et al. Hygienic habits and the dental condition in 12-year-old children. Adv Med Sci. 2006;51:142–144. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Biwersi C, Hepping N, Bode U, et al. Bloodstream infections in a German paediatric oncology unit: prolongation of inpatient treatment and additional costs. Int J Hyg Environ Health. 2009;212:541–546. doi: 10.1016/j.ijheh.2009.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry (AAPD). Guideline on periodicity of examination, preventive dental services, anticipatory guidance/counseling, and oral treatment for infants, children, and adolescents; 2013. Available from: http://www.aapd.org/media/Policies_Guidelines/G_Periodicity.pdf Accessed 20 May 2015

- 31.Ashkenazi M, Bidoosi M, Levin L. Factors associated with reduced compliance of children to dental preventive measures. Odontology. 2012;100:241–248. doi: 10.1007/s10266-011-0034-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ashkenazi M, Cohen R, Levin L. Self-reported compliance with preventive measures among regularly attending pediatric patients. J Dent Educ. 2007;71:287–295. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]