Abstract

Based on evidence-based dentistry (EBD) being a relatively new concept in dentistry, the attitudes, perceptions and level of awareness of dentists regarding EBD, and perceived barriers to its implementation into daily practice, were comparatively analysed in six countries of the FDI (World Dental Federation-Federation Dentaire Internationale)-European Regional Organization (ERO) zone (France, Georgia, Poland, Portugal, Slovakia and Turkey). For this purpose, a questionnaire, ‘The Relationship Between Dental Practitioners and Universities’, was developed by the FDI-ERO Working Group and applied by National Dental Associations (NDAs). A total of 850 valid responses were received, and cumulative data, comparisons between countries and potential impact of demographic variables were analysed. Regarding EBD, similar percentages of respondents reported that they ‘know what it is’ (32.8%) and ‘they practice’ (32.1%). Most respondents believed that ‘EBD is beneficial’ (89.1%); however, they had different thoughts regarding ‘who actually benefited from EBD’. Of the participants, 60% believed that ‘dentists experience difficulties in implementing EBD’. Although lack of time, lack of education and limited availability of evidence-based clinical guidelines were among the major barriers, there were differences among countries (P < 0.05). Significant differences were also observed between countries regarding certain questions such as ‘where EBD needed to be taught’ (P < 0.05), as both undergraduate and continuing education were suggested to be suitable. Age, practice mode and years of practice significantly affected many of the responses (P < 0.05). There was a general, positive attitude toward EBD; however, there was also a clear demand for more information and support to enhance dentists’ knowledge and use of EBD in everyday practice and a specific role for the NDAs.

Key words: Evidence-based dentistry, attitudes, perceptions, barriers, clinical implementation

INTRODUCTION

In dental practice, clinical decision making based on good-quality evidence is widely accepted to lead to more effective and efficient treatments1. Thus, evidence-based dentistry (EBD) is currently considered as the best approach to apply evidence from relevant research to the care of patients2. The American Dental Association defines EBD as ‘an approach to oral health care that requires the judicious integration of systematic assessments of clinically relevant scientific evidence, relating to the patient’s oral and medical condition and history, with the dentist’s clinical expertise and the patient’s treatment needs and preferences’3. Two main goals of EBD are to find best evidence and to transfer this to everyday practice2. Thereby, resolving the discrepancies between clinical research and dental practice might be possible4.

Evidence-based dentistry provides significant advantages to dentists, patients, the dental team and dental practice1., 5.. Dentists who make evidence-based clinical decisions have been shown to be able to continuously improve their clinical skills and performance. They can improve the quality and outcomes of the treatment by making decisions based on the best evidence with regard to treatment outcomes and cost-effectiveness after considering patient preferences1., 4., 6., 7.. The patients, who know that they will be treated in an evidence-based practice, can feel more confidence and trust in their dentist1., 8.. With regard to the dental team, staff confidence, trust and personal satisfaction can be increased by implementation of evidence-based practice. Thus, clinicians can provide interventions that are scientific, safe, efficient and cost-effective.

Evidence-based practice is a widely accepted term in medical fields worldwide; in dentistry, however, it has evolved over the past two decades and is still an emerging concept4., 6., 9.. Although the concept appears fundamentally simple and reasonable, dentists have been slow to translate current science into dental practice10., 11.. A number of studies have been performed to investigate the extent and mode of practitioners’ adoption of EBD and the described barriers to its implementation in countries around the world4., 9., 12., 13..

In several studies conducted among general dental practitioners, a low level of familiarity with evidence-based practice was found. Most respondents currently seek advice from their peer colleagues when faced with clinical uncertainties. Furthermore, only a small number of dentists could correctly define EBD and the various terms used in the field of EBD. The major barrier reported, by general dentists, to the practising of EBD was lack of time; however, a desire to find out more information on EBD was also observed4., 12.. In a study conducted by Madhavi et al.14 to evaluate EBD in orthodontics, it was reported that orthodontists generally had positive attitudes towards evidence-based practice. However, understanding the concept was poor, and awareness and understanding were influenced by age and educational level. Other barriers identified to practising EBD were the publication of ambiguous literature, lack of clinical guidelines and practical demands of work.

Other studies were also conducted to evaluate the levels of awareness and implementation of EBD among dentists in different countries8., 9., 12.. As an example, EBD was not a well-known concept among Malaysian dental practitioners. However, a majority of the respondents had positive attitudes, interest and a desire to learn further information about EBD8. In another study conducted among dentists in Kuwait, it was revealed that the overall awareness of EBD was low, and clinical decisions appeared to be mostly based on the clinician’s own judgment rather than on evidence-based sources. A majority of respondents highlighted the need for education in EBD12. Positive attitudes towards EBD were also observed among dental professionals in Sweden9. Although these studies attempted to assess awareness and implementation of EBD among different groups of clinicians, to the best of the authors’ knowledge, there is limited evidence regarding awareness and perceptions of dentists, from different countries within the FDI-ERO zone, towards EBD.

Therefore, the primary aim of this study was to perform a comparative evaluation of the awareness, attitudes and practice of EBD, and perceived barriers to its use, by dentists in France, Georgia, Poland, Portugal, Slovakia and Turkey. The potential factors affecting the perception, attitudes and practice of dentists were also analysed.

METHODS

A questionnaire, ‘The Relationship Between Dental Practitioners and Universities’, was developed by the World Dental Federation-European Regional Organization (FDI-ERO) Working Group to determine the perceptions, awareness and attitudes of dentists regarding EBD and the implementation of EBD in daily practice. The questionnaire had an introductory section describing the background of the questionnaire and its aims (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Questionnaire: (a) page 1 and (b) page 2.

This introduction was followed by nine closed questions aiming to analyse implementation of EBD into daily dental practice. In general, the issues focused on whether the dentists are familiar with EBD; if EBD is implemented in daily practice; if it is taught and, if so, when [e.g. undergraduate dental education (UDE) or continuing dental education (CDE)]; if there are obstacles to its effective implementation in practice; and if there is a perceived role in the field of EBD for the National Dental Associations (NDAs), as expressed by the individual dentists (e.g. organising courses, developing clinical guidelines and others) (The questionnaire is shown in Figure 1). The study was conducted in six countries of the FDI-ERO zone (France, Georgia, Portugal, Slovakia, Turkey and Poland), volunteered by their NDAs. The survey was either placed on the websites of each of these NDAs or was emailed to the member dentists by the relevant NDAs. Participants of the survey were voluntary responders.

The data were entered on a spreadsheet and the frequency distribution of the responses was calculated. For data analyses, the chi-square test was used (P < 0.05) using the SPSS Statistics for Windows Version 19.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA).

For analysis of cumulative data from the six countries, the percentage of responses to each questionnaire item was calculated. To compare awareness, perceptions, practice and perceived barriers of dentists from different countries towards EBD, pairwise comparisons of countries were performed using the chi-square test (P < 0.05).

The potential factors, including age, gender, years of practice and type of practice, affecting the perception, attitudes and practice of dentists were also analysed using the chi-square test (P < 0.05). From the questionnaire, ‘age’ of the respondents was obtained and categorised as ‘20–30’, ‘31–40’, ‘41–50’ and ‘≥51’ for comparison of age groups. Similarly, ‘years of practice’ was categorised as ‘0–10’, ‘11–20’, ‘21–30’ and ‘≥31’.

In the questionnaire, ‘kind of practice’ was evaluated under three categories, as follows: (i) General practice, or Specialist in dentistry; (ii) Private or public or Public and private; and (iii) Solo practice, or Solo practice in a medical clinic, or Group practice (in a dental clinic with other dentists), or Group practice (in a medical clinic with other dentists), or University faculty member (private university), or University faculty member (public university). In the third category, to obtain an adequate sample size for statistical analysis, the subcategories were combined into Solo practice, Group practice or University faculty member, which enabled us to evaluate further the potential impact of mode of various practice models on the perceptions and attitudes towards EBD.

RESULTS

A total of 850 responses were received from France, Georgia, Portugal, Slovakia, Turkey and Poland. Demographic characteristics of participants, expressed as number and frequency (percentage), are given in Table 1. Of the 850 valid responses obtained, most were from Portugal (n = 352; 41.4%), followed by Turkey (n = 209; 24.6%) and Poland (n = 145; 17.1%). Response rates to age, gender, years of practice and type of practice were different, and therefore the distribution of respondents according to these demographic variables was calculated on the basis of response rates. Regarding age, responders were evenly distributed between 20 and 50 years of age; in addition, 21.2% (n = 178) of dentists were ≥51 years of age. Gender was also evenly balanced, although female dentists were slightly more represented (n = 441; 52.9%). Most dentists who responded to the questionnaire were general practitioners (n = 675; 81.6%), working solo (n = 400; 48%) and in private practice (n = 644; 77.5%).

Table 1.

Demographic data (n = 850)

| Characteristics | Number | Frequency (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Country | ||

| France | 52 | 6.1 |

| Georgia | 28 | 3.3 |

| Portugal | 352 | 41.4 |

| Slovakia | 64 | 7.5 |

| Turkey | 209 | 24.6 |

| Poland | 145 | 17.1 |

| Age (years) | ||

| 20–30 years | 203 | 22.2 |

| 31–40 years | 235 | 28.1 |

| 41–50 years | 222 | 26.5 |

| ≥51 years | 178 | 21.2 |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 393 | 47.1 |

| Female | 441 | 52.9 |

| Years of practice | ||

| 0–10 years | 323 | 39.3 |

| 11–20 years | 235 | 28.7 |

| 21–30 years | 185 | 22.3 |

| ≥31 years | 87 | 10.5 |

| Kind of practice | ||

| General practitioner | 675 | 81.6 |

| Specialist | 152 | 18.4 |

| Kind of practice | ||

| Private | 644 | 77.5 |

| Public | 39 | 4.7 |

| Private and public | 148 | 17.8 |

| Kind of practice | ||

| Solo | 400 | 48 |

| Group practice | 365 | 44 |

| University | 62 | 7.6 |

| Others | 3 | 0.4 |

Overall data from six countries

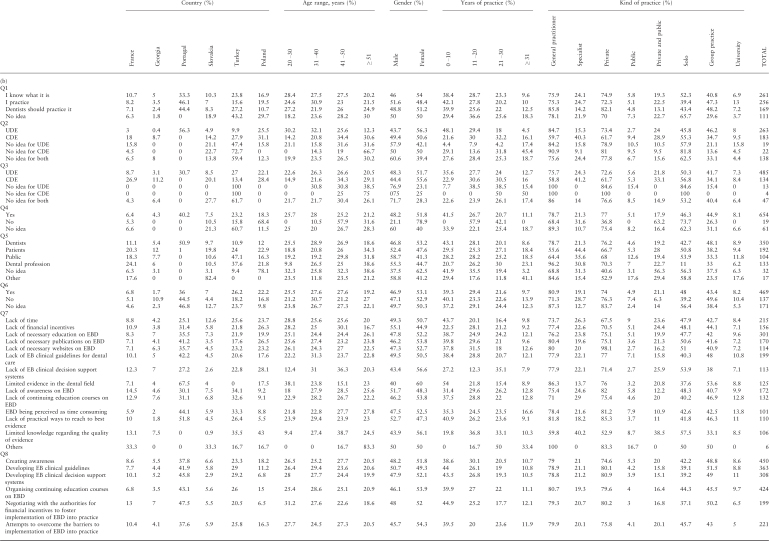

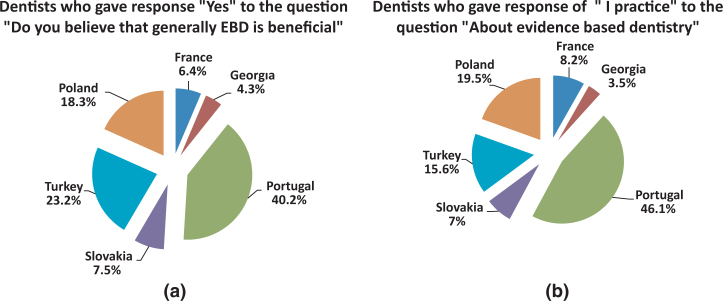

Table 2 presents the response to each question given by the total study group without stratification according to demographic variables. Regarding EBD, similar percentages of respondents reported that they ‘know what it is’ (32.8%) and ‘I practice’ (32.1%) (Figure 2). The reported level of learning of EBD was 41.9% and 29.3% for ‘undergraduate dental education’ and ‘continuing dental education’, respectively. However, the majority of respondents (71%) thought that ‘EBD should be taught in UDE’. A large proportion of the respondents (89.1%) believed that ‘EBD was beneficial’ (Figure 2). However, 60% of the respondents believed that ‘dentists experience difficulties in implementing EBD’, and they reported different ‘barriers to implementation of EBD into practice’. The most common reason for limited implementation was ‘lack of necessary education’, followed by ‘lack of time’. For the respondents, NDAs were expected to improve the implementation of EBD in practice by ‘creating awareness’ (22.7%) and ‘organising continuing education courses on EBD’ (21.3%). Desire for ‘developing evidence-based clinical guidelines’ was reported by 18.2% of the respondents, of whom 85% believed that ‘dental faculties and NDAs can collaborate for effective implementation of EBD into practice’.

Table 2.

Cumulative data for all participants

| Q1- About evidence-based dentistry (EBD)? | Q7- If yes, what are the barriers to implementation of EBD into practice?* | ||||

| Total | 797 | Total | 2023 | ||

| I know what it is | 261 | 32.8 | Lack of time | 215 | 10.6 |

| I practice | 256 | 32.1 | Lack of financial incentives | 156 | 7.7 |

| Dentists should practice it | 169 | 21.2 | Lack of necessary education on EBD | 301 | 14.9 |

| No idea | 111 | 13.9 | Lack of necessary publications on EBD | 170 | 8.4 |

| Q2- Has EBD been taught to you in | Lack of necessary websites on EBD | 112 | 5.5 | ||

| Total | 625 | Lack of EB clinical guidelines for dental care | 199 | 9.8 | |

| UDE | 262 | 41.9 | Lack of EB clinical decision support systems | 114 | 5.6 |

| CDE | 183 | 29.3 | Limited evidence available in the dental field | 126 | 6.2 |

| NI for UDE | 19 | 3 | Lack of awareness on EBD | 173 | 8.5 |

| NI for CDE | 22 | 3.5 | Lack of continuing education courses on EBD | 132 | 6.5 |

| NI for both | 138 | 22.1 | EBD being perceived as time consuming | 102 | 5 |

| Q3- Do you believe that EBD should be taught in | Lack of practical ways to reach to best evidence | 110 | 5.4 | ||

| Total | 683 | Limited knowledge regarding the quality of evidence (appraisal of evidence) | 107 | 5.3 | |

| UDE | 485 | 71 | Others | 6 | 0.3 |

| CDE | 134 | 19.6 | Q8- What is the role of National Dental Associations in improvement of the implementation of EBD in practice?* | ||

| NI for UDE | 13 | 1.9 | Total | 2001 | |

| NI for CDE | 4 | 0.6 | Creating awareness | 455 | 22.7 |

| NI for both | 47 | 6.9 | Developing EB clinical guidelines | 365 | 18.2 |

| Q4- Do you believe that generally EBD is beneficial | Developing EB clinical decision support systems | 308 | 15.4 | ||

| Total | 734 | Organising continuing education courses on EBD | 427 | 21.3 | |

| Yes | 654 | 89.1 | Negotiating with the authorities for financial incentives to foster implementation of EBD into practice | 200 | 10 |

| No | 19 | 2.6 | Attempts to overcome the barriers to implementation of EBD into practice | 221 | 11 |

| No idea | 61 | 8.3 | Others | 11 | 0.5 |

| Q5- If yes, who benefits from EBD and its implementation to dental practice | None | 14 | 0.7 | ||

| Total | 828 | Q9- Do you believe that dental faculties and National Dental Associations can collaborate for implementation of EBD into practice | |||

| Dentists | 350 | 42.3 | Total | 760 | |

| Patients | 192 | 23.2 | Yes | 646 | 85 |

| Public | 104 | 12.6 | No | 41 | 5.4 |

| Dental Profession | 133 | 16.1 | No idea | 73 | 9.6 |

| No idea | 32 | 3.9 | |||

| Other | 17 | 2.1 | |||

| Q6- Do you believe that dentists experience difficulties in implementing EBD | |||||

| Total | 779 | ||||

| Yes | 469 | 60.2 | |||

| No | 137 | 17.6 | |||

| No idea | 173 | 22.2 |

Multiple choice questions.

CDE, continuous dental education; EB, evidence-based; NI, no idea; UDE, undergraduate dental education.

Figure 2.

Frequency distribution of the total study population responses to (a) ‘Do you believe that generally EBD is beneficial?’ and (b) ‘About evidence based dentistry’.

Data based on individual countries

Varying numbers of dentists from the six participating countries responded to the question ‘About evidence based dentistry’ (Table 3a,b). Over 42% of Portuguese dentists ‘practice’ EBD and there was no dentist in that country who had ‘no idea’ about EBD (Table 3a). The percentage of dentists from Turkey who gave the response ‘I practice’ was significantly lower (P < 0.05) than those in France, Portugal and Poland (Table 4; Figure 3). All Portuguese dentists learned about EBD during their UDE, whereas more than half of Georgian and French dentists were trained in EBD during CDE. Statistical comparison of countries regarding the question ‘Has EBD been taught to you in’ generally revealed significant differences between counties (Table 4). In all countries, at least half of the respondents ‘believed that EBD should be taught in UDE’ (Table 3a). All dentists from Portugal and Georgia who were questioned thought that ‘EBD is beneficial’, and 76–90% of dentists from other countries agreed. Only one-third of French, Georgian and Slovakian dentists had been taught that ‘dentists’ get most benefits from implementing EBD, whereas this was the opinion of nearly 99% of Portuguese colleagues (Table 3a). Except for dentists from Portugal, about 25–29% of the respondents from five countries had been taught that ‘patients benefit from EBD’ and its implementation in dental practice. The benefits of EBD to the ‘public’ and ‘dental profession’ were most frequently reported by Turkish dentists (26.3% and 26.9%, respectively). About 70% of French and Polish dentists felt ‘difficulties in implementing EBD’, which was in contrast to Georgian dentists (30%) (Table 3a). Statistically significant differences (P < 0.05) were found between Georgia and Portugal, Portugal and Poland, and Turkey and Poland (Table 4). Regarding the question ‘what are the barriers to implementation of EBD into practice?’, dentists from Slovakia reported ‘lack of time’ as the most frequent barrier in implementation of EBD. For Portuguese dentists, ‘lack of time’ was not so important as in other countries (P < 0.001). In other countries, ‘lack of necessary education on EBD’ was the most frequent response, although ‘lack of awareness’ was also emphasised (Table 3a). The most frequently reported ‘role of NDAs in improvement of the implementation of EBD’ by French, Georgian, Slovakian and Polish dentists was ‘creating awareness’. The most popular response of dentists from Portugal and Turkey was ‘organising continuing education courses on EBD’. About 90% of dentists from France, Georgia, Portugal and Poland believed that ‘dental faculties and NDAs can collaborate for implementation of EBD into practice’, and 70% of dentists from Slovakia and Turkey agreed with this response (Table 3a).

Table 3.

(a) Percentages of respondents according to each variable and (b) Data based on age, gender, years of practice and kind of practice

Table 4.

Statistical data regarding comparative analysis of the six countries

| France/Georgia | France/Portugal | France/Slovakia | France/Turkey | France/Poland | Georgia/Portugal | Georgia/Slovakia | Georgia/Turkey | Georgia/Poland | Portugal/Slovakia | Portugal/Turkey | Portugal/Poland | Slovakia/Turkey | Slovakia/Poland | Turkey/Poland | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Q1 | |||||||||||||||

| I know what it is | 0.691 | 0.0001* | 0.287 | 0.002* | 0.004* | 0.022* | 0.882 | 0.115 | 0.151 | 0.006* | 0.199 | 0.195 | 0.086 | 0.132 | 0.891 |

| I practice | 0.628 | 0.415 | 0.233 | 0.002* | 0.554 | 1 | 0.888 | 0.178 | 0.983 | 0.483 | 0.0001* | 0.837 | 0.124 | 0.366 | 0.001* |

| Dentists should practice it | 0.519 | 0.913 | 1 | 1 | 0.107 | 0.523 | 0.576 | 0.488 | 0.761 | 1 | 0.845 | 0.021* | 1 | 0.123 | 0.021* |

| No idea | 0.483 | 0.0001* | 0.028* | 0.189 | 0.219 | 0.005* | 0.019* | 0.093 | 0.104 | 0.0001* | 0.0001* | 0.113 | 0.155 | 0.174 | 0.963 |

| Q2 | |||||||||||||||

| UDE | 0.151 | 0.0001* | 0.658 | 0.738 | 0.0001* | 0.0001* | 0.056 | 0.217 | 0.0001* | 0.002* | 0.0001* | 0.395 | 0.171 | 0.001* | 0.0001* |

| CDE | 0.754 | 0.0001* | 0.014* | 0.0001* | 0.005* | 0.0001* | 0.216 | 0.001* | 0.124 | 0.0001* | 0.0001* | 0.0001* | 0.018* | 0.858 | 0.003* |

| No idea for UDE | 0.548 | 0.002* | 1 | 0.711 | 0.189 | n.a. | 0.311 | 0.604 | 1 | 0.001* | 0.0001* | 0.024* | 0.511 | 0.204 | 0.373 |

| No idea for CDE | 1 | 0.129 | 0.222 | 0.208 | 0.264 | n.a. | 0.318 | 0.229 | n.a. | 0.0001* | 0.0001* | n.a. | 1 | 0.002* | 0.0001* |

| No idea for both | 0.058 | 0.0001* | 0.183 | 0.005* | 0.434 | 0.0001* | 0.508 | 1 | 0.001* | 0.0001* | 0.0001* | 0.0001* | 0.216 | 0.003* | 0.0001* |

| Q3 | |||||||||||||||

| UDE | 0.021* | 0.0001* | 0.076 | 0.021* | 0.414 | 0.338 | 0.474 | 0.469 | 0.055 | 0.001* | 0.0001* | 0.0001* | 0.958 | 0.207 | 0.028* |

| CDE | 0.252 | 0.0001* | 0.007* | 0.0001* | 0.0001* | 0.0001* | 0.435 | 0.0001* | 0.008* | 0.0001* | 0.0001* | 0.0001* | 0.0001* | 0.032* | 0.0001* |

| No idea for UDE | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | 0.078 | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | 0.374 | n.a. | n.a. | 0.0001* | n.a. | 0.087 | n.a. | 0.006* |

| No idea for CDE | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | 0.587 | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | 1 | n.a. | n.a. | 0.019* | n.a. | 0.576 | n.a. | 0.148 |

| No idea for both | 0.337 | 0.016* | 0.019* | 0.078 | 0.117 | 0.0001* | 0.374 | 0.777 | 0.001* | 0.0001* | 0.0001* | n.a. | 0.293 | 0.0001* | 0.0001* |

| Q4 | |||||||||||||||

| Yes | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. |

| No | |||||||||||||||

| No idea | |||||||||||||||

| Q5 | |||||||||||||||

| Dentists | 0.675 | 0.002* | 0.026* | 0.0001* | 0.0001* | 0.117 | 0.277 | 0.0001* | 0.0001* | 0.707 | 0.0001* | 0.0001* | 0.0001* | 0.001* | 0.017* |

| Patients | 0.653 | 0.0001* | 0.115 | 0.0001* | 0.0001* | 0.0001* | 0.336 | 0.0001* | 0.0001* | 0.0001* | 0.0001* | 0.0001* | 0.0001* | 0.0001* | 0.077 |

| Public | 0.638 | 0.0001* | 0.031* | 0.081 | 0.0001* | 0.0001* | 0.336 | 0.718 | 0.035* | 0.0001* | 0.0001* | 0.0001* | 0.376 | 0.396 | 0.005* |

| Dental profession | 0.011* | 0.0001* | 0.0001* | 0.0001* | 0.0001* | 0.0001* | 0.669 | 0.762 | 0.447 | 0.0001* | 0.0001* | 0.0001* | 0.865 | 0.902 | 0.383 |

| No idea | 1 | 0.016* | 0.586 | 0.261 | 0.031* | 0.074 | 0.518 | 0.397 | 0.082 | 0.154 | 0.051 | 0.0001* | 1 | 0.003* | 0.0001* |

| Other | 0.548 | 0.002* | 0.031* | 0.008* | 0.018* | n.a. | 0.005* | n.a. | n.a. | 0.0001* | n.a. | n.a. | 0.0001* | n.a. | 0.0001* |

| Q6 | |||||||||||||||

| Yes | n.a. | 0.331 | n.a. | 0.913 | n.a. | 0.0001* | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | 0.056 | 0.084 | 0.0001* | 0.081 | n.a. | 0.0001* |

| No | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. |

| No idea | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. |

| Q7 | |||||||||||||||

| Lack of time | 0.883 | 0.0001* | 0.669 | 0.196 | 0.994 | 0.032* | 0.499 | 0.671 | 0.927 | 0.0001* | 0.001* | 0.0001* | 0.023* | 0.417 | 0.074 |

| Lack of financial incentives | 0.422 | 0.001* | 0.031* | 0.013* | 0.673 | 0.268 | 0.376 | 0.591 | 0.607 | 1 | 0.449 | 0.0001* | 0.821 | 0.041* | 0.007* |

| Lack of necessary education on EBD | 0.037* | 0.017* | 0.192 | 0.038* | 0.501 | 0.0001* | 0.001* | 0.0001* | 0.002* | 0.627 | 0.771 | 0.018* | 0.791 | 0.339 | 0.058 |

| Lack of necessary publications on EBD | 1 | 0.727 | 0.077 | 0.187 | 0.364 | 0.686 | 0.058 | 0.165 | 0.681 | 0.068 | 0.098 | 0.007* | 0.413 | 0.001* | 0.0001* |

| Lack of necessary websites on EBD | 0.453 | 0.544 | 0.322 | 0.738 | 0.839 | 0.065 | 0.041* | 0.083 | 0.543 | 0.534 | 0.805 | 0.069 | 0.426 | 0.092 | 0.201 |

| Lack of EB clinical guidelines for dental care | 1 | 0.038* | 0.005* | 0.007* | 0.073 | 0.242 | 0.037* | 0.089 | 0.297 | 0.117 | 0.243 | 0.948 | 0.412 | 0.144 | 0.308 |

| Lack of EB clinical decision support systems | 1 | 0.0001* | 0.002* | 0.017* | 0.604 | 0.004* | 0.003* | 0.039* | 0.615 | 0.391 | 0.218 | 0.0001* | 0.126 | 0.004* | 0.024* |

| Limited evidence in the dental field | 1 | 0.361 | 0.202 | 0.0001* | 0.888 | 0.601 | 0.166 | 0.0001* | 0.776 | 0.006* | 0.0001* | 0.027* | 0.001* | 0.216 | 0.0001* |

| Lack of awareness on EBD | 0.146 | 0.0001* | 0.003* | 0.011* | 0.0001* | 0.062 | 0.549 | 1 | 0.031* | 0.349 | 0.0001* | 0.338 | 0.273 | 0.116 | 0.0001* |

| Lack of continuing education courses on EBD | 0.981 | 0.0001* | 0.031* | 0.094 | 0.0001* | 0.002* | 0.037* | 0.118 | 0.0001* | 0.736 | 0.004* | 0.344 | 0.328 | 0.302 | 0.003* |

| EBD being perceived as time consuming | 0.706 | 0.977 | 0.941 | 0.527 | 0.229 | 0.555 | 1 | 0.271 | 0.693 | 0.577 | 0.251 | 0.047* | 0.245 | 0.399 | 0.007* |

| Lack of practical ways to reach to best evidence | 0.125 | 0.488 | 0.072 | 0.276 | 0.001* | 0.281 | 1 | 0.549 | 0.617 | 0.123 | 0.461 | 0.0001* | 0.285 | 0.318 | 0.005* |

| Limited knowledge regarding the quality of evidence (appraisal of evidence) | 1 | 0.0001* | 0.0001* | 0.223 | 0.639 | 0.0001* | 0.0001* | 0.293 | 0.915 | 0.154 | 0.0001* | 0.0001* | 0.002* | 0.0001* | 0.003* |

| Others | 0.539 | 0.016* | 1 | 0.102 | 0.171 | n.a. | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.023* | 0.373 | 0.292 | 0.138 | 0.223 | 1 |

| Q8 | |||||||||||||||

| Creating awareness | 0.218 | 0.001* | 0.004* | 0.003* | 0.036* | 0.0001* | 0.0001* | 0.0001* | 0.003* | 0.771 | 0.671 | 0.089 | 0.591 | 0.166 | 0.226 |

| Developing EB clinical guidelines | 0.962 | 0.209 | 0.036* | 0.686 | 0.002* | 0.229 | 0.051 | 0.662 | 0.006* | 0.147 | 0.096 | 0.002* | 0.012* | 0.619 | 0.0001* |

| Developing EB clinical decision support systems | 1 | 0.012* | 0.0001* | 0.047* | 0.0001* | 0.117 | 0.0001* | 0.228 | 0.0001* | 0.0001* | 0.484 | 0.0001* | 0.0001* | 1 | 0.0001* |

| Organising continuing education courses on EBD | 1 | 0.747 | 0.076 | 0.851 | 0.201 | 1 | 0.228 | 1 | 0.478 | 0.031* | 0.848 | 0.099 | 0.029* | 0.371 | 0.097 |

| Negotiating with the authorities for financial incentives to foster implementation of EBD into practice | 1 | 0.001* | 0.0001* | 0.0001* | 0.0001* | 0.018* | 0.003* | 0.001* | 0.0001* | 0.134 | 0.051 | 0.0001* | 0.802 | 0.138 | 0.011* |

| Attempts to overcome the barriers to implementation of EBD into practice | 0.416 | 0.003* | 0.011* | 0.027* | 0.015* | 0.431 | 0.338 | 0.752 | 0.567 | 0.682 | 0.328 | 0.767 | 0.341 | 0.594 | 0.607 |

| None | 0.539 | 0.275 | 0.199 | 0.178 | 0.171 | 1 | n.a. | 1 | 1 | 0.597 | 0.716 | 0.679 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Other | n.a. | n.a. | 0.002* | 1 | 0.567 | n.a. | 0.029* | 1 | 1 | 0.0001* | 0.373 | 0.024* | 0.0001* | 0.001* | 0.309 |

| Q9 | |||||||||||||||

| Yes | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. |

| No | |||||||||||||||

| No idea | |||||||||||||||

CDE, continuing dental education; EB, evidence-based; EBD, evidence-based dentistry; UDE, undergraduate dental education. n.a, statistical comparison was not applicable because of the low response rate.

Difference is statistically significant (P < 0.05).

Figure 3.

(a) Frequency distribution of a total of 654 dentists who gave the response ‘yes’ to the question ‘Do you believe that generally EBD is beneficial?’, according to country. (b) Frequency distribution of a total of 256 dentists who gave the response ‘I practice’ to the question ‘About evidence based dentistry’, according to country.

Data regarding the potential impact of variables on perceptions and attitudes towards EBD

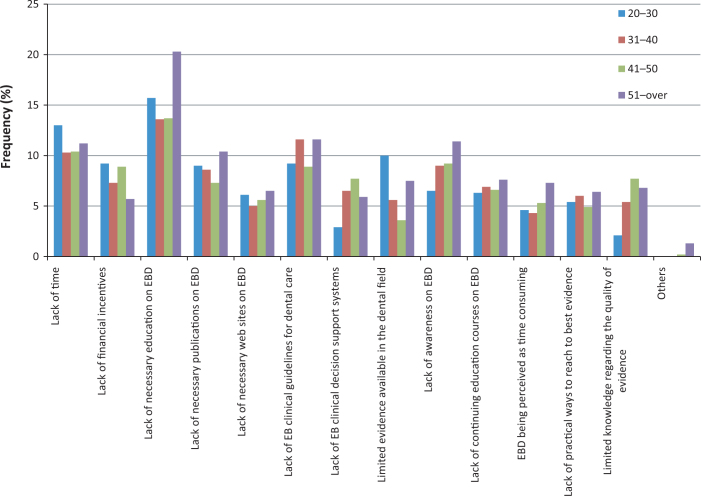

Data analyses with regard to the variables ‘age’ and ‘year of graduation from dental school’ revealed similar findings between countries regarding having knowledge about EBD (Table 5). The statistical results of these two variables indicate that EBD was taught to younger dentists in UDE, whereas EBD was taught to older dentists in CDE, and a higher proportion of young dentists ‘practised’ EBD compared with older dentists (Figure 4). Younger dentists more frequently ‘believed that generally EBD is beneficial’ compared with older dentists, and this finding was statistically significant (P < 0.05) (Table 5). ‘Lack of time’ was listed as a barrier more often among young dentists. ‘The lack of financial incentives’ seemed to be less important for dentists with more years in practice compared with those with fewer years in practice (Figure 5). Gender did not have significant effect on the respondents’ awareness perceptions and behaviour regarding EBD; however, the responses obtained from general practitioners were significantly different compared with those obtained from specialists in the aspects awareness (P = 0.002), practice (P = 0.004) and ‘find EBD beneficial’ (P < 0.001). Specialists also reported that they had received education on EBD during CDE (40.3%) rather than UDE (15.3%) (Table 5). Dentists working in public health-care services reported lack of time as the significantly (P < 0.001) most important barrier in implementation of EBD compared with private practice dentists. University members (36.6%) were more likely to practise EBD (P < 0.001) compared with solo (48%) and group (44%) practising dentists.

Table 5.

Data regarding the impact of age, gender, years of practice and kind of practice on the responses

| Age, years (n/%) |

Gender (n/%) |

Years of practice (n/%) |

Kind of practice (n/%) |

|||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 20–30 | 31–40 | 41–50 | ≥51 | P | Male | Female | P | 0–10 | 11–20 | 21–30 | ≥31–over | P | General practitioner | Specialist | P | Private | Public | Private and public | P | Solo | Group practice | University member | P | |

| Q1 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| I know what it is | 33.2 | 33.3 | 34.6 | 36.9 | 0.931 | 30.9 | 34.8 | 0.655 | 30.7 | 31.5 | 32.4 | 28.7 | 0.935 | 31.8 | 36 | 0.004* | 32.8 | 34.1 | 32.5 | 0.421 | 35.9 | 35.4 | 31.5 | 0.271 |

| I practice | 32.6 | 37.1 | 28.8 | 37.5 | 0.436 | 33.8 | 30.4 | 0.088 | 32.8 | 29.8 | 27.6 | 28.7 | 0.626 | 31.3 | 36.6 | 0.002* | 30.9 | 29.5 | 37 | 0.052 | 26 | 27.7 | 36.6 | 0.0001* |

| Dentists should practice it | 23.8 | 17.4 | 21.5 | 25.5 | 0.175 | 21.1 | 21.2 | 0.624 | 20.7 | 18.3 | 20 | 24.1 | 0.701 | 23.6 | 14 | 0.116 | 23.3 | 18.2 | 14.3 | 0.197 | 18.4 | 23.1 | 23.1 | 0.385 |

| No idea | 10.4 | 12.2 | 15.1 | 18.5 | 0.058 | 14.2 | 13.6 | 0.516 | 9.9 | 12.3 | 15.1 | 23 | 0.011* | 13.4 | 13.4 | 0.388 | 13 | 18.2 | 16.2 | 0.111 | 19.7 | 13.8 | 8.8 | 0.0001* |

| Q2 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| UDE | 30.2 | 52.5 | 38.1 | 18 | 0.0001* | 37.2 | 47.4 | 0.182 | 39 | 32.8 | 25.4 | 13.8 | 0.0001* | 47.7 | 26.7 | 0.116 | 43.8 | 18.9 | 45 | 0.002* | 33.4 | 55 | 48.7 | 0.639 |

| CDE | 19.1 | 23.8 | 35.8 | 31.5 | 0.0001* | 28.8 | 29.2 | 0.481 | 12.1 | 23 | 31.4 | 33.3 | 0.0001* | 23.2 | 48.7 | 0.0001* | 25.2 | 45.9 | 37.1 | 0.0001* | 30 | 27.9 | 28.3 | 0.015* |

| No idea for UDE | 2.9 | 1.9 | 3.4 | 3.4 | n.a. | 3.6 | 2.6 | 0.472 | 1.5 | 3 | 1.6 | 4.6 | n.a. | 3.4 | 2 | 1 | 3.4 | 5.4 | 1.4 | n.a. | 3.4 | 2.3 | 1.6 | 0.631 |

| No idea for CDE | 0 | 1.9 | 2.3 | 7.9 | 0.0001* | 3.6 | 3.5 | 0.954 | 0.6 | 1.3 | 3.8 | 11.5 | n.a. | 4.3 | 1.3 | 0.401 | 3.9 | 5.4 | 1.4 | n.a. | 5.9 | 2.3 | 1 | 0.006* |

| No idea for both | 19.9 | 20 | 20.5 | 23 | 0.036* | 26.9 | 17.3 | 0.001* | 11.5 | 16.2 | 18.4 | 28.7 | 0.001* | 21.3 | 21.3 | 0.068 | 23.8 | 24.3 | 15 | 0.407 | 27.2 | 14 | 20.4 | 0.001* |

| Q3 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| UDE | 78.4 | 74.7 | 66.3 | 57.7 | 0.046* | 68.9 | 73.2 | 0.411 | 52.9 | 56.6 | 62.2 | 70.1 | 0.018* | 73.5 | 66.1 | 0.0001* | 72.3 | 67.5 | 67.1 | 0.0001* | 66.7 | 74 | 73.3 | 0.311 |

| CDE | 14.4 | 17.1 | 23.8 | 21.9 | 0.001* | 17.5 | 21.8 | 0.487 | 9.3 | 17 | 21.6 | 24.1 | 0.0001* | 15.6 | 30.5 | 0 | 61.7 | 17.5 | 28.4 | 0.0001* | 20.9 | 22 | 19.5 | 0.044* |

| No idea for UDE | 0 | 2.4 | 2.1 | 2.8 | n.a. | 3 | 0.9 | 0.059 | 0.3 | 2.1 | 2.7 | 2.3 | n.a. | 2.6 | 0 | 0.142 | 2.3 | 5 | 0 | 3.3 | 2 | 0 | 0.028* | |

| No idea for CDE | 0 | 0 | 0.5 | 1.7 | n.a. | 0.9 | 0.3 | 0.348 | 0 | 0 | 1.1 | 2.3 | n.a. | 0.8 | 0 | 1 | 0.8 | 0 | 0 | 1.3 | 0 | 0 | ||

| No idea for both | 7.2 | 5.9 | 7.3 | 6.7 | 0.651 | 9.8 | 3.8 | 0.001* | 4.6 | 4.7 | 6.5 | 9.2 | 7.5 | 3.4 | 0.571 | 7.5 | 10 | 4.5 | 0.409 | 7.8 | 2 | 7.2 | 0.765 | |

| Q4 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Yes | 91.8 | 92.9 | 85.9 | 87.5 | 0.005* | 88.7 | 89.6 | 0.004* | 83.3 | 73.6 | 72.4 | 82.8 | 0.0001* | 89 | 92 | 0.0001* | 90.4 | 86.8 | 84.1 | n.a. | 84.8 | 87.1 | 92.4 | 0.041* |

| No | 0 | 1 | 5.8 | 3.4 | 1.1 | 4 | 0.0 | 4.7 | 4.3 | 0 | 2.3 | 4 | 1.3 | 0 | 8.7 | 2.8 | 9.7 | 1.2 | ||||||

| No idea | 8.2 | 6.1 | 8.4 | 9.6 | 10.2 | 6.4 | 6.2 | 5.5 | 8.1 | 12.6 | 8.7 | 4 | 8.3 | 13.2 | 7.2 | 12.4 | 3.2 | 6.4 | ||||||

| Q5 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Dentists | 51.7 | 49 | 42.3 | 36.5 | 0.467 | 39 | 45.8 | 0.891 | 46.4 | 41.7 | 37.8 | 34.5 | 0.114 | 48.1 | 30 | 0.068 | 46.3 | 30.8 | 34.9 | 0.681 | 33.8 | 52.5 | 48.6 | 0.023* |

| Patients | 20.9 | 19.4 | 22.5 | 37.1 | 0.0001* | 23.7 | 22.3 | 0.101 | 17.3 | 20.4 | 27.6 | 40.2 | 0.0001* | 18.2 | 33.6 | 0.0001* | 22 | 19.2 | 27.6 | 0.0001* | 25.4 | 14.8 | 22.9 | 0068 |

| Public | 11.6 | 9.7 | 14 | 18.5 | 0.011* | 14.6 | 10.6 | 0.012* | 9 | 12.3 | 14.1 | 21.8 | 0.011* | 11.8 | 15 | 0.0001* | 12.2 | 25 | 10.4 | 0.0001* | 13.6 | 13.1 | 10.6 | 0.025* |

| Dental profession | 7.6 | 17 | 14.9 | 28.7 | 0.0001* | 17.5 | 14.6 | 0.041* | 8.4 | 14.5 | 21.1 | 34.5 | 0.0001* | 16.1 | 16.6 | 0.0001* | 15.7 | 17.3 | 15.1 | 0.094 | 20.5 | 11.5 | 13.4 | 0.012* |

| No idea | 5.8 | 3.9 | 4.5 | 1.7 | 0.341 | 2.9 | 5 | 0.352 | 4 | 4.7 | 3.2 | 1.1 | 0.493 | 3.9 | 4 | 0.092 | 2.3 | 1.9 | 9.4 | 0.0001* | 4 | 6.6 | 3.2 | 0.647 |

| Other | 2.3 | 1 | 1.8 | 3.9 | n.a. | 2.4 | 1.7 | 0.465 | 1.5 | 1.3 | 1.1 | 8 | n.a. | 1.9 | 0.8 | 1 | 1.6 | 5.8 | 2.6 | n.a. | 2.6 | 1.6 | 1.4 | 0.123 |

| Q6 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Yes | 63 | 54.9 | 62.9 | 50.6 | 0.718 | 59.3 | 60.9 | 0.743 | 56.3 | 57.9 | 54.1 | 51.7 | 0.891 | 61 | 59.7 | 0.0001* | 58.2 | 62.2 | 68.1 | 0.017* | 60.4 | 56.9 | 59.6 | 0.028* |

| No | 15.3 | 19.4 | 14.1 | 20.8 | 17.3 | 17.7 | 17 | 13.6 | 16.8 | 21.8 | 15.6 | 26.2 | 17.4 | 27 | 15.3 | 14.6 | 12.3 | 19.5 | ||||||

| No idea | 21.7 | 21.2 | 22.9 | 21.3 | 23.3 | 21.4 | 19.8 | 21.3 | 22.7 | 18.4 | 23.4 | 14.1 | 24.4 | 10.8 | 16.7 | 25 | 30.8 | 21 | ||||||

| Q7 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Lack of time | 13 | 10.3 | 10.4 | 11.2 | 0.325 | 10.8 | 10.3 | 0.461 | 28.8 | 27.2 | 18.9 | 24.1 | 0.091 | 10.1 | 11.8 | 0.001* | 9.6 | 17.3 | 12.6 | 0.0001* | 10.9 | 11 | 10.6 | 0.608 |

| Lack of financial incentives | 9.2 | 7.3 | 8.9 | 5.7 | 0.193 | 8.9 | 6.7 | 0.026* | 20.1 | 18.3 | 16.8 | 16.1 | 0.734 | 7.8 | 7.5 | 0.134 | 7.4 | 7.3 | 9.6 | 0.053 | 7.7 | 9 | 7.7 | 1 |

| Lack of necessary education on EBD | 15.7 | 13.6 | 13.7 | 20.3 | 0.042* | 14.8 | 14.9 | 0.761 | 35.6 | 31.5 | 38.9 | 41.4 | 0.276 | 14.8 | 15.2 | 0.002* | 14.9 | 13.6 | 14.9 | 0.464 | 15.2 | 15.5 | 14 | 0.122 |

| Lack of necessary publications on EBD | 9 | 8.6 | 7.3 | 10.4 | 0.637 | 8.1 | 8.7 | 0.778 | 20.4 | 20.9 | 18.9 | 18.4 | 0.936 | 8.8 | 7.1 | 0.636 | 8.5 | 5.5 | 9.1 | 0.337 | 9.3 | 7.7 | 8 | 0.779 |

| Lack of necessary websites on EBD | 6.1 | 5 | 5.6 | 6.5 | 0.817 | 5.5 | 5.6 | 0.964 | 13 | 14.9 | 10.8 | 16.1 | 0.551 | 5.7 | 4.7 | 0.735 | 6 | 2.7 | 4.5 | 0.475 | 6.4 | 3.9 | 5.3 | 0.785 |

| Lack of EB clinical guidelines for dental care | 9.2 | 11.6 | 8.9 | 11.6 | 0.488 | 10.1 | 9.6 | 0.444 | 23.5 | 24.3 | 22.2 | 27.6 | 0.802 | 9.9 | 9.2 | 0.131 | 10.1 | 12.7 | 7.8 | 0.146 | 8.5 | 8.4 | 10.8 | 0.011* |

| Lack of EB clinical decision support systems | 2.9 | 6.5 | 7.7 | 5.9 | 0.005* | 5.1 | 6.1 | 0.389 | 9.6 | 14.5 | 21.6 | 10.3 | 0.002* | 5.7 | 5.4 | 0.269 | 5.4 | 2.7 | 7.3 | 0.041* | 6.5 | 6.5 | 5.2 | 0.376 |

| Limited evidence in the dental field | 10 | 5.6 | 3.6 | 7.5 | 0.0001* | 5.2 | 7.2 | 0.084 | 20.7 | 11.5 | 10.3 | 12.6 | 0.003 | 7 | 3.6 | 0.183 | 6.4 | 3.6 | 6.5 | 0.479 | 4.2 | 9 | 7.3 | 0.035* |

| Lack of awareness on EBD | 6.5 | 9 | 9.2 | 11.4 | 0.128 | 9.2 | 7.9 | 0.173 | 16.7 | 21.7 | 24.3 | 25.3 | 0.119 | 8.4 | 9 | 0.019* | 9.4 | 9.1 | 5.3 | 0.083 | 9.2 | 7.1 | 8.5 | 0.183 |

| Lack of continuing education courses on EBD | 6.3 | 6.9 | 6.6 | 7.6 | 0.981 | 6.3 | 6.8 | 0.819 | 14.9 | 16.2 | 15.7 | 19.5 | 0.767 | 6.1 | 8.2 | 0.001* | 6.6 | 5.5 | 6.5 | 0.781 | 5.5 | 6.5 | 6.8 | 0.023* |

| EBD being perceived as time consuming | 4.6 | 4.3 | 5.3 | 7.3 | 0.289 | 5 | 5.1 | 0.931 | 11.1 | 10.6 | 13 | 19.5 | 0.151 | 5.2 | 4.7 | 0.452 | 5.5 | 7.3 | 2.8 | 0.054 | 4.4 | 5.8 | 5 | 0.018* |

| Lack of practical ways to reach to best evidence | 5.4 | 6 | 4.9 | 6.4 | 0.901 | 6 | 5 | 0.206 | 13.9 | 12.3 | 14.1 | 11.5 | 0.888 | 5.9 | 4.3 | 1 | 6.2 | 3.6 | 3 | 0.102 | 4.6 | 6.5 | 6.4 | 0.149 |

| Limited knowledge regarding the quality of evidence | 2.1 | 5.4 | 7.7 | 6.8 | 0.0001* | 4.9 | 5.7 | 0.478 | 6.5 | 16.6 | 18.9 | 12.6 | 0.0001* | 4.2 | 9.2 | 0.0001* | 3.7 | 8.2 | 10.1 | 0.0001* | 7.2 | 3.2 | 4.1 | 0.052 |

| Others | 0 | 0 | 0.2 | 1.3 | n.a. | 0.3 | 0.3 | 1 | 0 | 0.4 | 1.6 | 2.3 | n.a. | 0.3 | 0 | 0.591 | 0.3 | 0.9 | 0 | n.a. | 0.4 | 0 | 0.4 | n.a |

| Q8 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Creating awareness | 22.2 | 21.1 | 24.7 | 28.7 | 0.128 | 22.9 | 22.5 | 0.486 | 53.6 | 57.4 | 49.7 | 55.2 | 0.465 | 22.6 | 23.5 | 0.032* | 21.7 | 27.9 | 26 | 0.101 | 23.2 | 21.6 | 23.9 | 0.001* |

| Developing EB clinical guidelines | 17.8 | 19.8 | 17 | 23.1 | 0.288 | 19.4 | 17.4 | 0.069 | 49.5 | 40.4 | 37.3 | 44.8 | 0.035 | 18.2 | 19 | 0.073 | 18.7 | 17.4 | 16.5 | 0.294 | 16 | 22.3 | 19.3 | 0.0001* |

| Developing EB clinical decision support systems | 15.9 | 15.7 | 14.8 | 18.8 | 0.251 | 15.3 | 15.3 | 0.743 | 41.2 | 34.9 | 31.9 | 36.8 | 0.176 | 15.3 | 16 | 0.103 | 15.9 | 14 | 13.3 | 0.194 | 13.9 | 17.6 | 16 | 0.0001* |

| Organising continuing education courses on EBD | 20 | 22.2 | 21.1 | 27.4 | 0.745 | 20.6 | 22.1 | 0.559 | 52.3 | 48.5 | 50.3 | 54 | 0.761 | 21.6 | 20.2 | 0.469 | 21.7 | 19.8 | 19.9 | 0.303 | 23.9 | 16.9 | 19.8 | 0.011* |

| Negotiating with the authorities for financial incentives to foster implementation of EBD into practice | 11.5 | 10.2 | 8.9 | 11.4 | 0.057 | 10.1 | 10 | 0.775 | 27.6 | 21.3 | 18.9 | 27.6 | 0.092 | 9.9 | 10.1 | 0.332 | 7 | 9.5 | 0.383 | 8.7 | 10.1 | 10.9 | 0.0001* | |

| Attempts to overcome the barriers to implementation of EBD into practice | 11.3 | 10 | 11.9 | 13.9 | 0.397 | 10.5 | 11.5 | 0.614 | 296.9 | 23.4 | 28.1 | 29.9 | 0.584 | 11.1 | 10.9 | 0.446 | 10.7 | 10.5 | 12.7 | 0.555 | 12.5 | 10.8 | 9.3 | 0.077 |

| None | 0 | 0.6 | 0.6 | 1.2 | n.a. | 0.5 | 0.6 | 1 | 0.3 | 2.1 | 2.2 | 1.1 | n.a. | 0.7 | 0 | 0.231 | 0.6 | 0 | 0.3 | n.a. | 0.9 | 0 | 0.5 | n.a |

| Other | 1.3 | 0.2 | 1 | 0.2 | n.a. | 0.7 | 0.7 | 1 | 2.217 | 0.5 | 2.3 | n.a. | 0.6 | 0.699 | 0.3 | 3.5 | 1.7 | n.a. | 1 | 0.7 | 0.3 | 0.073 | ||

| Q9 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Yes | 89.9 | 87 | 82.2 | 75 | 0.114 | 82 | 87.6 | 0.115 | 56.3 | 57.9 | 54.1 | 51.7 | 0.891 | 84.9 | 87.9 | 0.003* | 85.1 | 83.3 | 84.4 | n.a. | 78.6 | 91.7 | 88.8 | 0.061 |

| No | 4.3 | 5.3 | 7.1 | 6.3 | 6.4 | 4.6 | 17. | 13.6 | 16.8 | 21.8 | 5.3 | 6 | 5 | 2.8 | 7.8 | 7.4 | 5 | 3.7 | ||||||

| No idea | 5.9 | 7.7 | 10.7 | 18.7 | 11.6 | 7.8 | 19.8 | 21.3 | 22.7 | 18.4 | 9.8 | 6 | 9.9 | 13.9 | 7.8 | 14 | 3.3 | 7.5 | ||||||

CDE, continuing dental education; EB, evidence-based; EBD, evidence-based dentistry; UDE, undergraduate dental education. n.a, statistical comparison was not applicable because of the low response rate.

Difference is statistically significant (P < 0.05).

Figure 4.

(a) Frequency distribution of dentists who received evidence-based denstistry (EBD) education in ‘undergraduate dental education’, according to years of practice. (b) Frequency distribution of dentists who responded ‘I practice’ to the question ‘About evidence based dentistry’, according to years of practice.

Figure 5.

Frequency of reported barriers to the implementation of evidence-based dentistry (EBD) into practice.

DISCUSSION

Evidence-based medicine is the conscientious, explicit and judicious use of current best evidence in making decisions about the care of individual patients. The practice of evidence-based medicine means integrating individual clinical expertise with the best available external clinical evidence from systematic research20. Compared with medicine, evidence-based practice in dentistry is a relatively new concept that has evolved during the past 15–20 years and continues to evolve13., 21.. A number of previous studies have evaluated the level of awareness, and attitudes and practice of dentists of EBD, and described barriers to its implementation4., 8., 22., 23., 24.. These international reports provide evidence that the concept of EBD has different levels of awareness and adaptation amongst various groups of clinicians. However, to the best of the authors’ knowledge, there are currently very little data on a target population consisting of several FDI-ERO zone countries, together with the determination of the potential impact of a number of sociodemographic factors on evidence-based practice. Thus, the findings of the present study might be useful for designing effective national/regional/global strategies for implementing EBD into practice.

It was encouraging to note that when dentists were asked about EBD, most respondents reported familiarity and positive attitudes. Furthermore, 89.1% believed that ‘EBD is beneficial’. This finding, which is inconsistent with previous studies4., 8., 9. is important because it might reflect the high demands of modern-day dentists for best practice and clinical decision making. However, the percentage of dentists practising EBD (32.1%) was rather low among all respondents, in the absence of stratification according to country and other demographic variables (Figure 2), which also seems to be an important finding that needs to be taken into consideration.

The reasons for not adopting EBD in their daily practice might include the following: EBD is still an emerging concept and therefore the benefits of EBD in providing best practice are not known; poor understanding of evidence-based concepts by clinicians; and difficulties experienced by dentists in implementing EBD10., 11.. The last potential reason was confirmed by 60% of respondents in this study. As identifying barriers is an important step towards increasing evidence-based practice in dentistry, several studies were conducted to identify these barriers4., 8., 9., 11., 14.. In line with previous studies, the most frequently noted barriers were lack of education on EBD, lack of time and lack of clinical guidelines for dental care4., 8., 9.. Other frequent barriers reported in the reports were the ambiguous and conflicting nature of the literature, the demands of work, financial constraints and poor availability of evidence4., 8., 9.. Spallek et al.11 identified barriers previously not emphasised in the literature, such as fear of criticism by colleagues or lack of confidence in the research results. They performed a comprehensive survey on barriers to implementing EBD of early adopters. The survey included analysing barriers under the subtitles of associated with patient, with health-care provider and with health-care organisation, rating the barriers and their opinions for overcoming barriers. In the present study, basic barriers were identified by a large number of dentists. By revealing barriers, the practice of EBD, which aimed to provide continuous improvements in patient care based on new research developments, might be enhanced25. Taken together, all of these studies reveal that, despite the positive attitude of dentists towards EBD, there are an array of barriers in place when it comes to implementation of EBD in practice.

The role of NDAs in improvement of the implementation of EBD has also been evaluated in this survey, which previously had not been emphasised in the literature. The most frequent expectations of clinicians from NDAs included creating awareness, organising continuing education courses and developing evidence-based clinical guidelines. However, it should be emphasised that whilst well-developed evidence-based guidelines and continuing education courses improve dentists’ knowledge and overcome some barriers, they do not improve dentists’ clinical decision-making skills, which themselves may inadvertently create other barriers11., 13., 26., 27.. Therefore, drawing attention to finding best evidence and transferring this into everyday practice seems more important. Furthermore, producing guidelines is a precise procedure, and organisations should develop dissemination strategies for timely delivery of information, reduce the complexity of recommendations for clinicians and produce useable chairside tools with easy-to-understand evidence-based recommendations. The results of this survey also revealed that dentists have positive attitudes towards the collaboration of dental facilities and NDAs for implementation of EBD into practice, which has not been mentioned in the literature. In one study, conducted by Marshall et al.13 dental faculty members confirmed the importance of teaching students EBD. The EBD content of the facilities’ curriculum is unknown. It is likely that the collaboration of NDAs and dental faculties may have the potential to overcome some of the reported barriers and improve evidence-based practice.

Knowledge on EBD might be associated with cultural shifts or curricular variations9. Therefore, one objective of this study was to perform a comparative evaluation of the perceptions of dentists from six FDI-ERO zone countries: France, Georgia, Portugal, Slovakia, Turkey and Poland. As such a diverse response from FDI-ERO zone countries regarding EBD perceptions and attitudes of dentists has not previously been obtained, the findings of the present study might provide valuable information on the dentists in these countries. The literature reveals that EBD is presumed to be well accepted and practised in European countries8; however, this survey presents conflicting results. For example, the percentage of respondents who gave the response ‘I practice’ ranged from 20% to 42%. Although most of the dentists (77–100%) reported that they ‘believe EBD is beneficial’, EBD practice was still limited. This might be attributed to the lack of EBD training during UDE in all countries, except Portugal. Nowadays, academic dental institutions seek to provide curricular content and learning opportunities for students to develop an essential skill set for evidence-based practice. However, emphasis on EBD is relatively new, and thus educating undergraduate and graduate dentists on EBD may take time. Marshall et al.13 investigated the perceptions of members of a dental faculty regarding EBD and reported their positive attitudes and efforts in designing and expanding the EBD content in their curriculum. CDE is also an important resource for learning EBD11. In France and Georgia, most dentists learned EBD from CDE, rather than from their dental education.

Evaluation of perceived barriers according to country revealed that ‘lack of education’ and ‘lack of awareness on EBD’ were the most frequent difficulties. However, dentists from Slovakia reported ‘lack of time’ as the most frequent barrier in implementation of EBD, in line with previous studies4., 8., 9.. In contrast to the literature, ‘lack of time’ was of low statistical significance for dentists from Portugal compared with dentists from other countries. In the present study, lack of necessary education on EBD was the main difficulty. Besides these common difficulties, financial constrains were reported by dentists from Malaysia and the UK4., 8., poor availability of evidence was emphasised by dentists from Sweden9 and lack of Internet connection in the workplace was reported in Kuwait12. These results may lead to the conclusion that differences in sociocultural habits, the national economy, workplace conditions and health-care systems may influence dentists’ implementation of EBD.

A novel aspect of EBD, the role of NDAs in improvement of the implementation of evidence-based practice, was analysed in the present study. The results of the survey revealed that creating awareness was the most frequent expectation of dentists from the six countries included in this study; developing clinical guidelines and organising continuing education courses were also reported. This might be interpreted as the expectation, by dentists, of support and solutions from NDAs for the most frequently perceived barriers, such as ‘lack of education’ and ‘lack of awareness’. Whilst modern-day NDAs and institutions make efforts to emphasise the importance of EBD, efficient strategies to implement EBD should be applied, and the number of continuing educational courses may be increased. This might be a way to increase the collaboration between dental faculties and NDAs28.

Trends in awareness, perceptions and behaviour regarding EBD, with respect to age of participant and year of graduation from dental school, were quite prominent in the present study. Age of participant and years of practice did not have a significant effect on dentists regarding their awareness and practice of EDB. However, an important finding was that EBD was taught to younger dentists in UDE and they believed that education in UDE is the correct approach, whereas older dentists were educated in EBD through CDE. These findings support those reported in previous studies9., 29. indicating that EBD has evolved over the past two decades and that its inclusion in the curricula of academic dental institutions is relatively recent. A recent study of Straub-Morarend et al.9 indicated that as the year of dental school graduation became more recent, the percentage of students understanding EBD increased. They found that recent graduates were more likely to report insufficient time as a primary barrier to practising EBD, which is in agreement with our results; however, the results were not statistically significant. Considering all age groups, lack of education on EBD was the primary barrier, which was significantly higher for older dentists.

The responses obtained for general practitioners showed notable differences compared with those obtained for specialists. Specialists were significantly more likely to report that they ‘know’, ‘practice’ and ‘find EBD beneficial’, as indicated in previous research9. Following the trend of the dentists with more years in practice, specialists also reported that they had received education on EBD during CDE rather than during UDE. This may be related to the advanced training they received in evidence-based practice. Furthermore, all scientific activities performed during the postgraduate education period may make dentists familiar with critical thinking and EBD practice9., 13.. Regarding the barriers, specialists had a significant emphasis on quality of science and reported that limited knowledge was available regarding the quality of evidence. However, the skewed distribution of the general practitioners and specialists, in which general practitioners comprised the majority (81.6%) of respondents, should be considered when interpreting these findings.

University members were more likely to practice EBD; however, their frequency in this study was quite low (7.6%) compared with solo practising (48%) and group practising (44%) dentists. Their high awareness of, and effort to teach, EBD has previously been reported13. This study also uncovered interesting and unaddressed considerations regarding the effect of the type of practice on EBD. Awareness of the concept of EBD and believing its benefits was significantly low among solo practising dentists. This may indicate the advantages of team work and a multidisciplinary approach. Dentists working in public health-care services reported lack of time as a significant and the most important barrier to the implementation of EBD compared with private practice dentists. This reveals that the high demand by patients of public health-care services may preclude dentists from performing EBD practice. However, this finding should not be overestimated as 77.5% of the respondents worked in private, 4.7% worked in public and 17.8% worked in both private and public practices.

This questionnaire survey was anonymous and therefore the respondents could be comfortable communicating their true thoughts. However, the study included a number of limitations. One was the difficulty in achieving good feedback from most of the Web questionnaires. The data were self-reported and this is not the most accurate method of gathering the perceptions of health-care professionals29. However, it would have been difficult to gather information from such a large number of people from different countries using a method other than a self-reported survey. Another possible problem was that, even though the surveys were anonymous, in order to create a good impression, the respondents may not report their actual and true perceptions14. Setting a more detailed questionnaire, including items measuring the level of knowledge and practice, may partially overcome this problem. In previous studies, technical terms commonly used in evidence-based practice were considered and the source of information was asked for when faced with clinical uncertainties4., 8.. Further research is warranted, especially to identify knowledge levels and solutions to increase the use of the relevant literature in scientific practice.

Despite these limitations, the present study is likely to provide significant data based on the perceptions and attitudes of European dentists regarding EBD and implementation of EBD into daily practice. It is possible that these data may be a helpful tool for decision-makers, educators and members of organised dentistry who plan to further improvements the implementation of EBD into daily practice.

Evidence-based practice is a relatively new concept in dentistry. Awareness, attitudes and knowledge of dentists from different countries varied towards EBD, which might be attributed to socio-economic, cultural and curricular variations. Respondents expressed awareness and positive attitudes towards EBD; however, the frequency of practising EBD was low. Except for Portugal, there is a lack of EBD training during UDE in all countries, and young dentists, in particular, believed that they were receiving such education, during their undergraduate training, from the dental faculty. Dental specialists generally had a higher level of awareness regarding EBD compared with general practitioners. Lack of education on EBD, lack of time and lack of clinical guidelines for dental care were the major barriers identified in this study. Respondents desired to enhance their knowledge and use of EBD in everyday practice. They expect educational programmes to be organised by NDAs and supported by dental faculties.

Previous studies reveal the expressed need, for an improved collaboration between the NDAs and the dental faculties28., 30.. It is likely that EBD, and its effective implementation into practice, may be an appropriate area in which NDAs and dental faculties may consider for working together.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank to the six National Dental Associations (French Dental Association, Georgian Dental Association, Polish Dental Chamber, Portuguese Dental Association, Slovakian Dental Chamber, Turkish Dental Association) for kindly participating this survey. The authors also would like to thank all the members of WG.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Richards D, Lawrence A. Evidence based dentistry. Br Dent J. 1995;79:270–273. doi: 10.1038/sj.bdj.4808896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kishore M, Panat SR, Aggarwal As, et al. Evidence based dental care: integrating clinical expertise with systematic research. J Clin Diagn Res. 2014;8:259–262. doi: 10.7860/JCDR/2014/6595.4076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.ADA policy statement on evidence-based dentistry. Available from: http://ebd.ada.org/en/about/. Accessed 24 January 2015

- 4.Iqbal A, Glenny AM. General dental practitioners’ knowledge of and attitudes towards evidence based practice. Br Dent J. 2002;23:587–591. doi: 10.1038/sj.bdj.4801634. discussion 583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Merijohn GK, Bader JD, Frantsve-Hawley J, et al. Clinical decision support chairside tools for evidence-based dental practice. J Evid Based Dent Pract. 2008;8:119–132. doi: 10.1016/j.jebdp.2008.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sutherland SE. Evidence-based dentistry: part I. Getting started. J Can Dent Assoc. 2001;67:204–206. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bader J, Ismail A, Clarkson J. Evidence-based dentistry and the dental research community. J Dent Res. 1999;78:1480–1483. doi: 10.1177/00220345990780090101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yusof ZY, Han LJ, San PP, et al. Evidence-based practice among a group of Malaysian dental practitioners. J Dent Educ. 2008;72:1333–1342. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Straub-Morarend CL, Marshall TA, Holmes DC, et al. Toward defining dentists’ evidence-based practice: influence of decade of dental school graduation and scope of practice on implementation and perceived obstacles. J Dent Educ. 2013;77:137–145. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kao RT. The challenges of transferring evidence-based dentistry into practice. J Evid Based Dent Pract. 2006;6:125–128. doi: 10.1016/j.jebdp.2005.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Spallek H, Song M, Polk DE, et al. Barriers to implementing evidence-based clinical guidelines: a survey of early adopters. J Evid Based Dent Pract. 2010;10:195–206. doi: 10.1016/j.jebdp.2010.05.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McColl A, Smith H, White P, et al. General practitioner’s perceptions of the route to evidence based medicine: a questionnaire survey. BMJ. 1998;31:361–365. doi: 10.1136/bmj.316.7128.361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Marshall TA, Straub-Morarend CL, Qian F, et al. Perceptions and practices of dental school faculty regarding evidence-based dentistry. J Dent Educ. 2013;77:146–151. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Madhavji A, Araujo EA, Kim KB, et al. Attitudes, awareness, and barriers toward evidence-based practice in orthodontics. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2011;140:309–316. doi: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2010.05.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bauer J, Spackmart S, Chiappelli F, et al. Evidence-based dentistry: a clinician’s perspective. J Calif Dent Assoc. 2006;34:511–517. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gillette J, Matthews JD, Frantsve-Hawley J, et al. The benefits of evidence-based dentistry for the private dental office. Dent Clin North Am. 2009;53:33–45. doi: 10.1016/j.cden.2008.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Crawford JM, Briggs CL, Engeland CG. Publication bias and its implications for evidence-based clinical decision making. J Dent Educ. 2010;74:593–600. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ismail AI, Bader JD. Evidence-based dentistry in clinical practice. J Am Dent Assoc. 2004;135:78–83. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.2004.0024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chiappelli F, Prolo P, Newman M, et al. Evidence-based practice in dentistry: benefit or hindrance. J Dent Res. 2003;82:6–7. doi: 10.1177/154405910308200102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sackett DL, Rosenberg WMC, Muir Gray JA, et al. Evidence based medicine: what it is and what it isn’t. BMJ. 1996;312:71–72. doi: 10.1136/bmj.312.7023.71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gillette J. Answering clinical questions using the principles of evidence-based dentistry. J Evid Based Dent Pract. 2009;9:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jebdp.2008.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hannes K, Norré D, Goedhuys J, et al. Obstacles to implementing evidence-based dentistry: a focus group-based study. J Dent Educ. 2008;72:736–744. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nieri M, Mauro S. Continuing professional development of dental practitioners in Prato, Italy. J Dent Educ. 2008;72:616–625. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rabe P, Holmén A, Sjögren P. Attitudes, awareness, and perceptions on evidence-based dentistry and scientific publications among dental professionals in the county of Halland, Sweden: a questionnaire survey. Swed Dent J. 2007;31:113–120. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rinchuse D, Kandasamy S, Ackerman M. Deconstructing evidencein orthodontics: making sense of systematic reviews, randomized clinical trials, and meta-analyses. World J Orthod. 2008;9:167–176. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.van der Sanden WJ, Mettes DG, Plasschaert AJ, et al. Effectiveness of clinical practice guideline implementation on lower third molar management in improving clinical decision-making: a randomized controlled trial. Eur J Oral Sci. 2005;113:349–354. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0722.2005.00232.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Grol R. Successes and failures in the implementation of evidence based guidelines for clinical practice. Med Care. 2001;39(Suppl. 2):II46–II54. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200108002-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yamalik N, Mersel A, Margvelashvili V, et al. Analysis of the extent and efficiency of the partnership and collaboration between the dental faculties and National Dental Associations within the FDI–ERO zone: a dental faculties’ perspective. Int Dent J. 2013;63:266–272. doi: 10.1111/idj.12045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Iacopino AM. The influence of “new science” on dental education: current concepts, trends, and models for the future. J Dent Educ. 2007;71:450–462. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yamalik N, Mersel A, Cavalle E, et al. Collaboration between dental faculties and National Dental Associations (NDAs) within the World Dental Federation-European Regional Organization zone: an NDAs perspective. Int Dent J. 2011;61:307–313. doi: 10.1111/j.1875-595X.2011.00075.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]