Abstract

Objective: To assess the epidemiology and risk indicators for dental erosion among 12-year-old schoolchildren in South Brazil. Methods: A population-based cross-sectional survey was conducted in Porto Alegre, Brazil, using a representative sample of 12-year-old schoolchildren (n = 1,528). Dental erosion was recorded according to the Basic Erosive Wear Examination (BEWE) index. Parents answered questions on socio-economic status, brushing frequency and general health. Schoolchildren answered questions on dietary habits. Anthropometric data were collected. Statistical analysis included logistic and Poisson regression models. Results: The prevalence of dental erosion was 15% [95% confidence interval (95% CI): 13.6–16.5], being mainly mild erosion. Boys [odds ratio (OR) = 1.57, 95% CI: 1.17–2.10], private school attendees (OR = 1.45, 95% CI: 1.01–2.06) and schoolchildren reporting the daily consumption of soft drinks (OR = 5.04, 95% CI: 1.17–21.71) were more likely to have at least one tooth with dental erosion. Gender [boys, rate ratio (RR) = 1.66, 95% CI: 1.28–2.17], type of school (private, RR = 1.89, 95% CI: 1.53–2.35), the consumption of soft drinks (sometimes: RR = 5.27, 95% CI: 1.46–19.05; daily: RR = 6.82, 95% CI: 1.39–33.50) and the daily consumption of lemon (RR = 1.49, 95% CI: 1.11–2.00) were significantly associated with the number of affected surfaces. Conclusions: The present study found a moderate prevalence of dental erosion among young schoolchildren, with mild erosion being the most prevalent condition. Socio demographic variables and dietary habits were associated with dental erosion in this population.

Key words: Tooth erosion, prevalence, risk assessment, epidemiology

INTRODUCTION

Dental erosion is a multifactorial condition caused by the interplay of chemical, biological and behavioural factors, in which dental tissues are dissolved by acid not derived from bacterial metabolism1. It has been suggested in the literature that the prevalence of dental erosion is increasing as a result of modern dietary habits and lifestyles2. Globally, studies have reported prevalence rates of dental erosion ranging from 13% to 75% among 12-year-old children3., 4., 5., 6., 7., 8., 9., 10.. This wide variation is probably related to different diagnostic criteria and study sample characteristics.

Several studies have attempted to explain the occurrence of dental erosion among children and adolescents; however, few risk factors/indicators are well established in the literature. Whereas gender10., 11., 12., 13., 14. and the consumption of acid foods/beverages15 have been consistently associated with dental erosion, the investigation of socio-economic factors4., 6., 11., 16., 17., 18., 19. have yielded mixed results. Similarly, inconsistent associations with gastro-oesophageal disorders20 and asthma21., 22. have been reported. Recently, the childhood obesity epidemic and its possible consequences on oral health have received increased attention. In this context, data on the relationship between dental erosion and overweight/obesity among children and adolescents are very limited.

Few studies have investigated the occurrence of dental erosion and associated factors among children in developing countries, and this is especially true for Latin American populations4., 5., 6., 10.. Importantly, none of the studies conducted in Brazil used probability sampling strategies. Therefore, the aim of this study was to assess the epidemiology and risk indicators for dental erosion among 12-year-old South Brazilian schoolchildren.

METHODS

Study design and sample

A cross-sectional survey was performed between September 2009 and December 2010 to assess the oral health status of 12-year-old schoolchildren attending public and private schools in the city of Porto Alegre in South Brazil23. Porto Alegre had an estimated population of 1,409,939 inhabitants and a Human Development Index (HDI) of 0.805 in 2010. According to the Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics, 31.1% of families living in Porto Alegre had a monthly per-capita income of up to one Brazilian minimum wage in 201324. The National Health Survey of Schoolchildren showed that around 40% of schoolchildren attending the 9th grade reported a high consumption of soft drinks and sugary foods (5 days in the last seven)25.

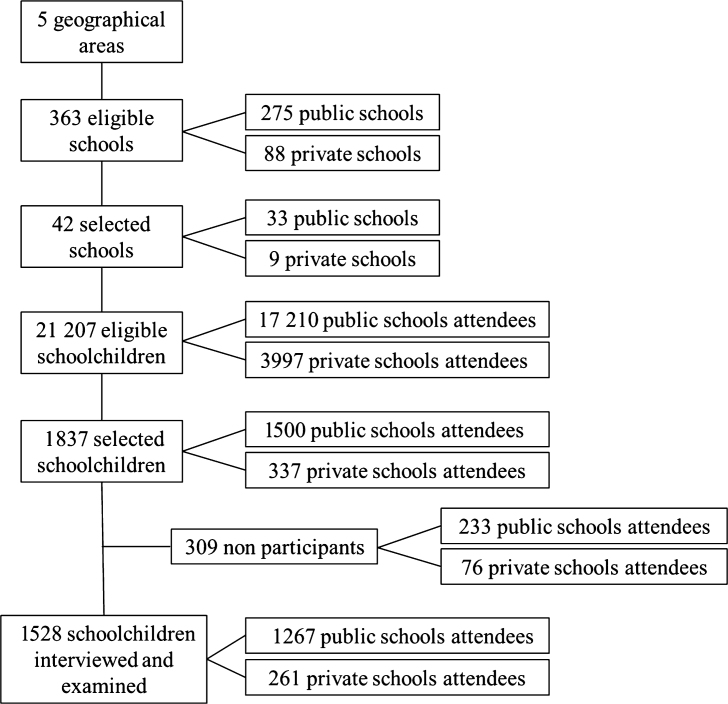

A multistage probability sampling strategy was used. The primary sampling unit consisted of five geographical areas organised according to the municipal water fluoridation system. Within each area, schools were randomly selected proportional to the number of existing private and public schools. A total of 42 schools were included in the study (33 public and nine private), ranging from two to 15 schools per area. Schoolchildren born in 1997 or 1998 were randomly selected proportional to school size. Figure 1 provides the flowchart of the study.

Figure 1.

Flowchart of the study.

Sample size calculation

Sample size calculation for the overall oral survey was based on available data regarding the prevalence of dental caries, which was estimated to be approximately 60%26. This approach was used to ensure the necessary sample size for the assessment of other study outcomes, including dental erosion. A sample size of 1,331 was calculated to be necessary to estimate a prevalence of dental caries of 60%26 with a precision level of ±3% for the 95% confidence interval (95% CI). A total recruitment of 1,837 was deemed necessary to account for a design effect of 30% and a non-response rate of 40%. Post-hoc calculations confirmed that the final sample of 1,528 schoolchildren enrolled in the present study far exceeded the sample size necessary for prevalence estimates of dental erosion at the 3% precision level (see the Discussion for details).

Data collection

Clinical examination was performed at the schools using artificial light, a clinical mirror and a probe, and with the students in a supine position. After tooth cleaning and drying, one examiner (L.S.A.) classified permanent incisors and first molars according to the Basic Erosive Wear Examination (BEWE) index27. The BEWE index classifies free surfaces into four scores, as follows: 0, without erosive wear; 1, initial loss of surface texture; 2, distinct defect, hard tissue loss <50% of the surface area; and 3, distinct defect, hard tissue loss ≥50% of the surface area. A few dental surfaces with extensive cavities and/or fillings and calculus were not scored.

Anthropometric data were gathered to allow the calculation of body mass index (BMI) [weight (kg)/height (m2)]. Participants were weighed using a digital scale, and two readings were made. A third assessment was taken if a difference of >0.3 kg was observed between measurements. The mean of the two closest measurements was used to calculate BMI. Height was measured to the nearest full centimeter using inelastic metric tape attached to a flat wall with no footer. The measurements were taken by a single examiner (N.D.T.) with the students wearing light clothing and no shoes.

A questionnaire to gather information on demographics, socio-economic characteristics, brushing frequency and information on general health of schoolchildren was sent to parents/legal guardians. The presence of gastro-oesophageal disorders was assessed by asking about regurgitation, difficulty/pain in swallowing, frequent vomiting and heartburn. Parents/legal guardians were also asked about history of asthma and any use of medication. Schoolchild answered a dietary questionnaire on the consumption of acid fruits and beverages. This questionnaire was completed in the classroom before the clinical examination, and the research team was available to answer any questions or concerns.

Measurement reproducibility

Before the beginning of the study, calibration was assessed by the repeated examination of 30 photographs including sound and eroded teeth with different degrees of erosion severity. During the survey, intra-examiner agreement was monitored by means of repeated examinations conducted on 61 randomly selected schoolchildren. To minimise any examiner bias, the second examination was conducted after a minimal time interval of 2 days. The lowest Cohen’s kappa value for BEWE was 0.75 (unweighted).

Non-response analysis

Detailed information regarding non-response is published elsewhere23. In brief, 1,528 of 1,837 (participation rate = 83.17%) schoolchildren were included. Telephone contact was established with 176 of 306 parents/legal guardians of the non-respondents, and reasons for non-participation included: no interest because of previous access to dental care (26%); schoolchildren refused to participate (27%); lack of informed consent or questionnaire (24%); not available at school during the normal survey schedule (19%) and 4% showed concern about biosecurity or refused to answer socioeconomic questions. A sample of 80 non-respondents was randomly selected for further demographic and socio-economic data analysis. Participants and non-respondents were compared using the chi-square and Fisher’s exact tests. No significant differences were observed between participants and non-respondents regarding gender (P = 0.31), race (P = 0.13) and school type (P = 0.70, chi-square test). A significant difference for socio-economic status was observed, with non-respondents being of higher socio-economic status than participants (P < 0.001). To minimise non-response bias caused by discrepancies between the study participants and subjects who did not participate, a weight variable based on information provided by the Primary Education School Census28 was used in the statistical analysis (see Data analysis for details).

Data analysis

Prevalence was defined as the percentage of schoolchildren presenting at least one dental surface with dental erosion. Extent was defined as the number of affected surfaces with erosive wear. Severity was categorised as no erosion (all teeth with score 0), mild erosion (one tooth or more with score 1) or severe erosion (one tooth or more with scores 2 or 3).

BMI-for-age Z-scores were calculated using specific software (AnthroPlus; WHO, Geneva, Switzerland). BMI-for-age Z-score is a measure of the standard deviation (SD) away from the standardised mean BMI. It is considered one of the most appropriate measures of weight in children and adolescents because it accounts for the wide, natural variation in growth. Using cut-offs recommended by the World Health Organization (WHO)29, the sample was categorised as follows: normal weight (BMI-for-age Z-score ≤ +1SD), overweight (BMI-for-age Z-score > +1SD to ≤ +2SD) and obese (BMI-for-age Z-score ≥ +2SD). Twenty-five schoolchildren classified as underweight (BMI-for-age Z-score ≤ −2SD) were included in the normal-weight category.

Socio-economic status was assessed using the standard Brazilian economic classification30, which is based on the education level of the head of the household, the family’s purchasing power, household characteristics and access to services. The household total score was calculated by adding predetermined weighted values for each item assessed. Based on the cut-offs proposed by the criterion, households were classified into low (≤13 points), mid–low (≥14 to ≤22 points), mid–high (≥23 to ≤28 points) and high (≥29 points). Toothbrushing frequency was categorised as ≤1, 2 and ≥3 times/day. The consumption of soft drinks, orange and lemon was classified as rarely/never, sometimes and daily. Gastro-oesophageal disorders and asthma were classified as absent or present.

Data analysis was performed using STATA software (Stata 11.1 for Windows; Stata Corporation, College Station, TX, USA) and using survey commands that take into account the survey design, including clustering, weighing and robust variance estimation. A weight variable was therefore used to adjust for the potential bias in the population estimates31. The sample weight was adjusted for the probability of selection and population distribution according to gender, school type and city area using the Primary Education School Census28. Pairwise comparisons for demographic, socio-economic and physical factors were carried out using the Wald test. The chosen level of statistical significance was 5%.

The association between dental erosion prevalence and extent and the explanatory variables was assessed using survey logistic and Poisson regression models, respectively. Odds ratio (OR), rate ratio (RR) and their respective 95% CIs were estimated and reported. Preliminary analysis was carried out using an univariable model and variables showing associations with P < 0.25 were selected for the multivariable analysis. Confounding and effect modification were assessed. Variables were considered as confounders if a change of 30% or more on other variables in the model was observed. Effect modification was assessed by including interaction terms in the multivariable models. No statistically significant interactions were observed. The contribution of each variable to the model was assessed using the Wald statistic.

Ethical considerations

This study was approved by the Federal University of Rio Grande do Sul Research Ethics Committee (299/08) and by the Municipal Health Department of Porto Alegre Research Ethics Committee (process no 001.049155.08.3/register no 288). All participants and their parents/legal guardians provided written informed consent. This study was conducted in full accordance with the World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki.

RESULTS

Overall, 229 out of 1,528 schoolchildren had at least one tooth with dental erosion, yielding a prevalence rate of 15%. Considering the whole sample, 0.55 (95% CI: 0.47–0.63) teeth and 0.64 (95% CI: 0.54–0.74) surfaces, on average, were affected by dental erosion. Among those who presented with dental erosion, 3.67 (95% CI: 3.30–4.05) teeth and 4.24 (95% CI: 3.84–4.63) surfaces, on average, were affected. The number of affected teeth ranged from two to twelve; 50% of the children had two affected teeth, 42% had three to six affected teeth and 8% had seven or more affected teeth. Mild erosion (BEWE score 1) was observed in the majority of cases (n = 207) whereas severe erosion (BEWE scores 2 and 3) was detected in 22 individuals. As shown in Table 1, the most commonly affected surfaces were the buccal surfaces of the upper central incisors and the palatal surfaces of all upper incisors (mild erosion). On the other hand, severe erosion was mostly found in the occlusal surfaces of lower first molars.

Table 1.

Intra-oral distribution of dental erosion according to tooth group and dental surface

| Erosion | Maxillary |

Mandibular |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Central incisors | Lateral incisors | First molars | Central incisors | Lateral incisors | First molars | ||

| Buccal | No | 2,788 (91.3) | 3,009 (99.2) | 2,993 (100) | 2,982 (97.7) | 2,982 (97.9) | 2,941 (99.4) |

| Mild | 258 (8.5) | 22 (0.7) | 0 | 68 (2.2) | 63 (2.1) | 19 (0.6) | |

| Severe | 6 (0.2) | 3 (0.1) | 0 | 4 (0.1) | 2 (0.1) | 0 | |

| Palatal/Lingual | No | 2,840 (93) | 2,906 (95.8) | 2,989 (99.7) | 3,046 (99.7) | 3,038 (99.7) | 2,960 (100) |

| Mild | 204 (6.7) | 122 (4) | 7 (0.2) | 8 (0.3) | 9 (0.3) | 0 | |

| Severe | 10 (0.3) | 6 (0.2) | 2 (0.1) | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Occlusal | No | – | – | 2,955 (98.4) | – | – | 2,860 (96.6) |

| Mild | – | – | 44 (1.5) | – | – | 72 (2.4) | |

| Severe | – | – | 4 (0.1) | – | – | 29 (1) | |

Values are given as n (%).

Prevalence of erosion was significantly higher among boys than girls, and among children who attended private schools than among those attending public schools (Table 2). Similarly, a significantly higher number of affected teeth/surfaces were observed among boys than girls and among private school attendees when compared with students attending public schools. Erosion extent was also significantly higher among schoolchildren with daily consumption of soft drinks. Borderline significant differences (P = 0.05) in the prevalence and extent of dental erosion were observed for soft drinks and lemon consumption, respectively.

Table 2.

Frequency distribution of the sample, erosion prevalence and extent (mean number of affected surfaces), according to explanatory variables

| Variable | n (%) | Prevalence(95% CI) | P* | Extent(95% CI) | P* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sociodemographics | |||||

| Gender | |||||

| Girls | 758 (49.7) | 12.1 (10.1–14.2) | 0.03† | 0.47 (0.35–0.60) | 0.03† |

| Boys | 770 (50.3) | 17.9 (14.4–21.3) | 0.80 (0.60–0.99) | ||

| Socio-economic status | 0.74† | 0.19† | |||

| High | 141 (9.2) | 15.9 (11.2–20.6) | Ref. | 0.70 (0.62–0.78) | Ref. |

| Mid–high | 358 (23.4) | 15.1 (12.0–18.2) | 0.66 | 0.72 (0.44–1.00) | 0.88 |

| Mid–low | 871 (57.0) | 15.5 (14.3–16.7) | 0.84 | 0.62 (0.52–0.72) | 0.16 |

| Low | 158 (10.4) | 11.1 (1.0–21.1) | 0.37 | 0.46 (−0.08 to 1.01) | 0.29 |

| School | |||||

| Public | 1,267 (82.9) | 14.0 (12.2–15.7) | 0.01† | 0.54 (0.43–0.65) | <0.001† |

| Private | 261 (17.1) | 18.9 (17.7–20.0) | 0.99 (0.94–1.04) | ||

| Dietary habits | |||||

| Soft drinks‡ | 0.18† | 0.04† | |||

| Rarely/never | 48 (3.1) | 4.7 (−4.4 to 13.8) | Ref. | 0.14 (–0.11 to 38.0) | Ref. |

| Sometimes | 1,031 (67.5) | 13.9 (11.3–16.5) | 0.05 | 0.59 (0.47–0.70) | 0.006 |

| Daily | 448 (29.4) | 18.8 (12.9–24.7) | 0.05 | 0.81 (0.44–1.19) | 0.03 |

| Orange‡ | 0.96† | 0.92† | |||

| Rarely/never | 118 (7.7) | 15.4 (7.6–23.1) | Ref. | 0.69 (0.21–1.17) | Ref. |

| Sometimes | 915 (59.9) | 15.2 (11.6–18.8) | 0.96 | 0.64 (0.55–0.73) | 0.79 |

| Daily | 494 (32.4) | 14.7 (9.7–19.7) | 0.79 | 0.63 (0.43–0.83) | 0.71 |

| Lemon‡ | 0.30† | 0.15† | |||

| Rarely/never | 694 (45.5) | 14.9 (13.8–15.9) | Ref. | 0.65 (0.52–0.78) | Ref. |

| Sometimes | 683 (44.8) | 14.4 (11.7–17.0) | 0.61 | 0.57 (0.43–0.72) | 0.39 |

| Daily | 148 (9.7) | 19.4 (13.6–25.3) | 0.11 | 0.89 (0.54–1.23) | 0.05 |

| General health | |||||

| Gastro-oesophageal disorders | |||||

| Absent | 1,450 (94.9) | 14.8 (13.4–16.2) | 0.08† | 0.62 (0.53–0.72) | 0.22† |

| Present | 78 (5.1) | 18.8 (13.3–24.2) | 0.89 (0.35–1.44) | ||

| Asthma | |||||

| Absent | 1,410 (92.3) | 14.9 (13.7–16.1) | 0.47† | 0.62 (0.52–0.73) | 0.51† |

| Present | 118 (7.7) | 17.3 (8.6–25.9) | 0.80 (0.16–1.43) | ||

| Weight status | 0.72† | 0.99† | |||

| Normal | 986 (64.53) | 15.5 (12.9–18.0) | Ref. | 0.64 (0.51–0.77) | Ref. |

| Overweight | 335 (21.92) | 14.4 (10.7–18.1) | 0.61 | 0.63 (0.55–0.71) | 0.88 |

| Obese | 207 (13.55) | 14.2 (7.8–20.7) | 0.61 | 0.64 (0.37–0.91) | 0.92 |

| Controlling variables | |||||

| Brushing frequency | 0.38† | 0.66† | |||

| ≤1 time/day | 341 (22.3) | 15.8 (10.7–20.8) | Ref. | 0.54 (0.27–0.81) | Ref. |

| 2 times/day | 677 (44.3) | 14.1 (11.5–16.7) | 0.52 | 0.67 (0.54–0.79) | 0.33 |

| ≥3 times/day | 510 (33.4) | 15.8 (13.4–18.3) | 0.98 | 0.66 (0.54–0.78) | 0.34 |

| Bruxism | |||||

| Absent | 1,110 (72.6) | 15.0 (12.7–17.2) | 0.91† | 0.59 (0.34–0.85) | 0.55† |

| Present | 418 (27.4) | 15.3 (9.9–20.6) | 0.65 (0.56–0.75) | ||

| Total | 1,528 (100) | 15.0 (13.6–16.5) | 0.64 (0.54–0.74) | ||

95% CI, 95% confidence interval; Ref., reference category.

Wald test.

Overall P-value testing the null hypothesis for all categories.

Because of missing data, the number values do not sum to 1,528.

The association between dental erosion prevalence and explanatory variables are shown in Table 3. In the multivariable analysis, it was observed that boys (OR = 1.57, 95% CI = 1.17–2.10), private school attendees (OR = 1.45, 95% CI = 1.01–2.06), and schoolchildren reporting the daily consumption of soft drinks (OR = 5.04, 95% CI = 1.17–21.71) were more likely to have at least one tooth with dental erosion.

Table 3.

Association between dental erosion prevalence and explanatory variables in univariable and multivariable logistic regression analyses

| Characteristic | Univariable |

Multivariable |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | 95% CI | P | OR | 95%CI | P | |

| Sociodemographics | ||||||

| Gender | ||||||

| Girls | Ref. | Ref. | ||||

| Boys | 1.57 | 1.17–2.11 | 0.002 | 1.57 | 1.17–2.10 | 0.003 |

| Socio-economic status | ||||||

| High | Ref. | |||||

| Mid–high | 0.94 | 0.54–1.62 | 0.82 | |||

| Mid–low | 0.97 | 0.59–1.59 | 0.90 | |||

| Low | 0.66 | 0.34–1.29 | 0.22 | |||

| School | ||||||

| Public | Ref. | Ref. | ||||

| Private | 1.43 | 1.00–2.03 | 0.045 | 1.45 | 1.01–2.06 | 0.04 |

| Dietary habits | ||||||

| Soft drinks | ||||||

| Rarely/never | Ref. | Ref. | ||||

| Sometimes | 3.27 | 0.77–13.78 | 0.11 | 3.62 | 0.84–15.49 | 0.08 |

| Daily | 4.69 | 1.10–19.9 | 0.04 | 5.04 | 1.17–21.71 | 0.03 |

| Orange | ||||||

| Rarely/never | Ref. | |||||

| Sometimes | 0.98 | 0.58–1.68 | 0.96 | |||

| Daily | 0.95 | 0.54–1.66 | 0.86 | |||

| Lemon | ||||||

| Rarely/never | Ref. | |||||

| Sometimes | 0.96 | 0.71–1.30 | 0.80 | |||

| Daily | 1.38 | 0.86–2.22 | 0.18 | |||

| General health | ||||||

| Gastro-oesophageal disorders | ||||||

| Absent | Ref. | |||||

| Present | 1.32 | 0.73–2.40 | 0.35 | |||

| Asthma | ||||||

| Absent | Ref. | |||||

| Present | 1.19 | 0.71–2.00 | 0.50 | |||

| Weight status | ||||||

| Normal | Ref. | |||||

| Overweight | 0.92 | 0.64–1.32 | 0.64 | |||

| Obese | 0.91 | 0.59–1.40 | 0.66 | |||

| Controlling variables | ||||||

| Brushing frequency | ||||||

| ≤1 time/day | Ref. | |||||

| 2 times/day | 0.87 | 0.61–1.26 | 0.47 | |||

| ≥3 times/day | 1.00 | 0.68–1.47 | 0.98 | |||

| Bruxism | ||||||

| Absent | Ref. | |||||

| Present | 1.02 | 0.74–1.41 | 0.89 | |||

95% CI, 95% confidence interval; OR, odds ratio; Ref., reference category.

Table 4 shows the association between the number of surfaces with dental erosion and the explanatory variables. After adjustment for other cofactors, gender (boys, RR = 1.66, 95% CI = 1.28–2.17), type of school (private, RR = 1.89, 95% CI = 1.53–2.35) and the consumption of soft drinks (sometimes: RR = 5.27, 95% CI = 1.46–19.05; daily: RR = 6.82, 95% CI = 1.39–33.50) and the daily consumption of lemon (RR = 1.49, 95% CI = 1.11–2.00) were significantly associated with the number of affected surfaces.

Table 4.

Association between dental erosion extent (mean number of affected surfaces) and explanatory variables in univariable and multivariable Poisson regression analyses

| Characteristic | Univariable |

Multivariable |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RR | 95% CI | P | RR | 95% CI | P | |

| Sociodemographics | ||||||

| Gender | ||||||

| Girls | Ref. | Ref. | ||||

| Boys | 1.68 | 1.26–2.23 | <0.001 | 1.66 | 1.28–2.17 | <0.001 |

| Socio-economic status | ||||||

| High | Ref. | |||||

| Mid–high | 1.03 | 0.73–1.45 | 0.87 | |||

| Mid–low | 0.89 | 0.77–1.02 | 0.09 | |||

| Low | 0.66 | 0.29–1.51 | 0.33 | |||

| School | ||||||

| Public | Ref. | Ref. | ||||

| Private | 1.84 | 1.59–2.13 | <0.001 | 1.89 | 1.53–2.35 | <0.001 |

| Dietary habits | ||||||

| - Soft drinks | ||||||

| Rarely/never | Ref. | Ref. | ||||

| Sometimes | 4.33 | 1.24–15.15 | 0.022 | 5.27 | 1.46–19.05 | 0.01 |

| Daily | 5.97 | 1.26–28.33 | 0.025 | 6.82 | 1.39–33.50 | 0.02 |

| Orange | ||||||

| Rarely/never | Ref. | |||||

| Sometimes | 0.93 | 0.56–1.54 | 0.77 | |||

| Daily | 0.91 | 0.60–1.39 | 0.67 | |||

| Lemon | ||||||

| Rarely/never | Ref. | Ref. | ||||

| Sometimes | 0.88 | 0.68–1.14 | 0.34 | 0.92 | 0.69–1.24 | 0.60 |

| Daily | 1.36 | 1.15–1.60 | <0.001 | 1.49 | 1.11–2.00 | 0.007 |

| General health | ||||||

| Gastro-oesophageal disorders | ||||||

| Absent | Ref. | |||||

| Present | 1.43 | 0.96–2.12 | 0.08 | |||

| Asthma | ||||||

| Absent | Ref. | |||||

| Present | 1.27 | 0.70–2.30 | 0.42 | |||

| Weight status | ||||||

| Normal | Ref. | |||||

| Overweight | 0.99 | 0.83–1.17 | 0.87 | |||

| Obese | 1.01 | 0.77–1.34 | 0.92 | |||

| Controlling variables | ||||||

| Brushing frequency | ||||||

| ≤1 time/day | Ref. | |||||

| 2 times/day | 1.23 | 0.83–1.81 | 0.30 | |||

| ≥3 times/day | 1.22 | 0.83–1.77 | 0.31 | |||

| Bruxism | ||||||

| Absent | Ref. | |||||

| Present | 0.90 | 0.66–1.24 | 0.54 | |||

95% CI, 95% confidence interval; Ref., reference category; RR, rate ratio.

DISCUSSION

Using data derived from a population-based cross-sectional study we investigated the epidemiology of dental erosion among 12-year-old schoolchildren from South Brazil. Dental erosion was present in 15% of the schoolchildren; this was mostly localised mild erosion affecting multiple teeth in particular upper incisors. Gender, type of school and dietary habits were associated with dental erosion in this population.

Our finding, that 15% of 12-year-old schoolchildren had dental erosion, was lower than in the majority of studies conducted on this age group3., 5., 7., 8., 11.. Two recent studies used the BEWE index to record dental erosion among 12-year-old subjects and found prevalence rates of 75% in Hong Kong9 and of 52.9% in Montevideo, Uruguay10. Direct comparisons among studies are difficult because of differences in diagnostic criteria and methods of examination. In our study, the fact that artificial light was used, tooth cleaning and drying were performed and students were in a supine position may have increased the accuracy of the clinical examination and could explain, at least in part, the lower estimates. In this regard, studies that have not followed similar protocols may have had trouble differentiating other causes of tooth wear. As previously discussed in the literature1, distinguishing among erosion, attrition and abrasion during a clinical examination is challenging, and this is especially true in epidemiological settings. To assess this phenomenon more clearly, we collected data on brushing frequency and bruxism as proxy variables for abrasion and attrition, respectively. These variables were neither associated with dental erosion nor affected by the other associations in the multivariable analyses.

The present study found that boys were more affected by dental erosion than girls, which is in agreement with previous studies11., 12., 13., 14.. An explanation for this finding is a matter of speculation but it might be related to food preferences and behavioural and lifestyle factors. Compared with girls, boys are more likely to prefer sour foods and beverages with lower pH levels2 and to practice intense physical activities, which may decrease salivary flow32., 33..

Students of private schools were more likely to be affected by dental erosion than public school attendees, whereas no significant trends could be observed regarding socio-economic status and dental erosion. These findings are in agreement with previous studies conducted in Brazil that also found a higher prevalence of dental erosion in private schools4., 16. and no association between erosion and socio-economic variables (economic class19 or family income6., 17.). In contrast, an inverse relationship seems to exist in developed countries, with dental erosion being more commonly associated with social deprivation11., 12., 18.. These differences could be explained by differences in dietary factors and lifestyle among socio-economic strata in developing and developed countries.

Extrinsic factors, including demineralising acidic foods/drinks, have been consistently associated with dental erosion15, which is in agreement with our findings. Soft drinks consumption and the consumption of lemon were significantly associated with erosion prevalence/extent in this population of schoolchildren, which may be explained by their low pH. Similarly, Zhang et al.9 reported that children who consume juice fruits at least once every 2 days had significantly higher BEWE scores than their counterparts who did not.

Dental erosion may be caused by intrinsic factors, such as gastro-oesophageal disorders, characterised by the retrograde flow of gastroduodenal contents into the oesophagus and the oral cavity. In our study, the association between gastro-oesophageal disorders and dental erosion did not reach statistical significance. In contrast to our findings, a recent systematic review showed that most studies found significant associations between gastro-oesophageal reflux and dental erosion20. The limited number of children with gastro-oesophageal disorder and the likely short duration of the exposure because of young age may explain our results, at least in part.

It has been suggested in the literature that asthma medications may cause dental erosion as a result of their effects on salivary flow/composition and low pH; however, no association was observed in this population. Although a case–control study has shown that asthmatic adolescents were more affected by dental erosion22, no association was found in a population-based longitudinal study conducted in the UK21, thus corroborating our findings.

No relationship between overweight/obesity and dental erosion was observed in this population of South Brazilian schoolchildren, which corroborates previous findings in a population-based sample of North American adolescents34. In contrast to these findings, Tong et al.35 and Isaksson et al.36 found that obese children and young adults were more likely to have dental erosion than were normal-weight individuals. Soft drinks consumption has been proposed as a common risk factor for both conditions. Although soft drinks consumption, as previously discussed, has been consistently associated with erosion, a recent meta-analysis has found a negligible association between sugar-sweetened beverages and BMI in children and adolescents, with a high chance of publication bias favouring studies with positive results37.

The strengths of our study include its large population-based sample of 12-year-old schoolchildren; clinical examination protocol encompassing tooth cleaning and drying; and the high reproducibility of the examiner. The cross-sectional nature may be seen as a shortcoming of this study because it impedes hypothesis of causality. However, cross-sectional studies are useful for identifying risk indicators to be investigated as definitive risk factors in further longitudinal assessments. The use of prevalence estimates of dental caries for the sample-size calculation might be seen as inappropriate for the present study. Nevertheless, post-hoc sample-size calculations, based on our present findings, indicate that the final sample of 1,528 schoolchildren would provide a precision level of approximately 2% for the 95% CI for prevalence estimates of dental erosion, which can be confirmed by the results presented in Table 2. In perspective, the sample size necessary to estimate the prevalence of dental erosion, assuming the observed prevalence of 15%, a precision of 3%, a design effect of 30% and non-response of 40%, would be 990 schoolchildren, which is far less than the 1,528 children enrolled in the present study sample. Thus, the present sample size clearly did not have any detrimental effect on our findings.

In conclusion, the present study found a moderate prevalence of dental erosion among young schoolchildren, with mild erosion being the most prevalent condition. The upper incisors were the most commonly affected teeth. Socio-demographic variables and dietary habits were associated with dental erosion in this population.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the support of the National Coordination of Post-graduate Education (CAPES), Ministry of Education, Brazil and Federal University of Rio Grande do Sul. We would like to thank Colgate-Palmolive Company for donating toothbrushes and toothpaste.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest related to this study.

REFERENCES

- 1.Lussi A, Jaeggi T. Erosion–diagnosis and risk factors. Clin Oral Investig. 2008;12(Suppl 1):S5–S13. doi: 10.1007/s00784-007-0179-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gambon DL, Brand HS, Veerman EC. Dental erosion in the 21st century: what is happening to nutritional habits and lifestyle in our society? Br Dent J. 2012;213:55–57. doi: 10.1038/sj.bdj.2012.613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Truin GJ, van Rijkom HM, Mulder J, et al. Caries trends 1996–2002 among 6- and 12-year-old children and erosive wear prevalence among 12-year-old children in The Hague. Caries Res. 2005;39:2–8. doi: 10.1159/000081650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Peres KG, Armenio MF, Peres MA, et al. Dental erosion in 12-year-old schoolchildren: a cross-sectional study in Southern Brazil. Int J Paediatr Dent. 2005;15:249–255. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-263X.2005.00643.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.de Carvalho Sales-Peres SH, Goya S, de Araujo JJ, et al. Prevalence of dental wear among 12-year-old Brazilian adolescents using a modification of the tooth wear index. Public Health. 2008;122:942–948. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2007.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gurgel CV, Rios D, Buzalaf MA, et al. Dental erosion in a group of 12- and 16-year-old Brazilian schoolchildren. Pediatr Dent. 2011;33:23–28. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Huew R, Waterhouse PJ, Moynihan PJ, et al. Dental erosion among 12 year-old Libyan schoolchildren. Community Dent Health. 2012;29:279–283. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Correr GM, Alonso RC, Correa MA, et al. Influence of diet and salivary characteristics on the prevalence of dental erosion among 12-year-old schoolchildren. J Dent Child (Chic) 2009;76:181–187. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhang S, Chau AM, Lo EC, et al. Dental caries and erosion status of 12-year-old Hong Kong children. BMC Public Health. 2014;14:7. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-14-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Alvarez Loureiro L, Fabruccini Fager A, Alves LS, et al. Erosive tooth wear among 12-year-old schoolchildren: a population-based cross-sectional study in Montevideo, Uruguay. Caries Res. 2015;49:216–225. doi: 10.1159/000368421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dugmore CR, Rock WP. The prevalence of tooth erosion in 12-year-old children. Br Dent J. 2004;196:279–282. doi: 10.1038/sj.bdj.4811040. discussion 3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Milosevic A, Young PJ, Lennon MA. The prevalence of tooth wear in 14-year-old school children in Liverpool. Community Dent Health. 1994;11:83–86. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Arnadóttir IB, Saemundsson SR, Holbrook WP. Dental erosion in Icelandic teenagers in relation to dietary and lifestyle factors. Acta Odontol Scand. 2003;61:25–28. doi: 10.1080/ode.61.1.25.28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bardolia P, Burnside G, Ashcroft A, et al. Prevalence and risk indicators of erosion in thirteen- to fourteen-year-olds on the Isle of Man. Caries Res. 2010;44:165–168. doi: 10.1159/000314067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Li H, Zou Y, Ding G. Dietary factors associated with dental erosion: a meta-analysis. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e42626. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0042626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mangueira DF, Sampaio FC, Oliveira AF. Association between socioeconomic factors and dental erosion in Brazilian schoolchildren. J Public Health Dent. 2009;69:254–259. doi: 10.1111/j.1752-7325.2009.00131.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vargas-Ferreira F, Praetzel JR, Ardenghi TM. Prevalence of tooth erosion and associated factors in 11–14-year-old Brazilian schoolchildren. J Public Health Dent. 2011;71:6–12. doi: 10.1111/j.1752-7325.2010.00194.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Al-Dlaigan YH, Shaw L, Smith A. Dental erosion in a group of British 14-year-old, school children. Part I: prevalence and influence of differing socioeconomic backgrounds. Br Dent J. 2001;190:145–149. doi: 10.1038/sj.bdj.4800908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Auad SM, Waterhouse PJ, Nunn JH, et al. Dental erosion amongst 13- and 14-year-old Brazilian schoolchildren. Int Dent J. 2007;57:161–167. doi: 10.1111/j.1875-595x.2007.tb00119.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Marsicano JA, de Moura-Grec PG, Bonato RC, et al. Gastroesophageal reflux, dental erosion, and halitosis in epidemiological surveys: a systematic review. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;25:135–141. doi: 10.1097/MEG.0b013e32835ae8f7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dugmore CR, Rock WP. Asthma and tooth erosion. Is there an association? Int J Paediatr Dent. 2003;13:417–424. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-263x.2003.00497.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Al-Dlaigan YH, Shaw L, Smith AJ. Is there a relationship between asthma and dental erosion? A case control study. Int J Paediatr Dent. 2002;12:189–200. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-263x.2002.00360.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Damé-Teixeira N, Alves LS, Susin C, et al. Traumatic dental injury among 12-year-old South Brazilian schoolchildren: prevalence, severity, and risk indicators. Dent Traumatol. 2013;29:52–58. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-9657.2012.01124.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics . Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics; Rio de Janeiro: 2014. Synthesis of Social Indicators. An Analysis of Living Conditions. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics . Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics; Rio de Janeiro: 2009. National Health Survey of Schoolchildren. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Barbachan e Silva B, Maltz M. [Prevalence of dental caries, gingivitis, and fluorosis in 12-year-old students from Porto Alegre – RS, Brazil, 1998/1999] Pesqui Odontol Bras. 2001;15:208–214. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bartlett D, Ganss C, Lussi A. Basic Erosive Wear Examination (BEWE): a new scoring system for scientific and clinical needs. Clin Oral Investig. 2008;12(Suppl 1):S65–S68. doi: 10.1007/s00784-007-0181-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Brazilian Ministry of Education . MEC/INEP; Brasília: 2010. Primary Education School Census. [Google Scholar]

- 29.de Onis M, Onyango AW, Borghi E, et al. Development of a WHO growth reference for school-aged children and adolescents. Bull World Health Organ. 2007;85:660–667. doi: 10.2471/BLT.07.043497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.ABEP . ABEP; São Paulo: 2009. Standard Brazilian Economic Classification. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Korn B, Graubard E. Wiley; New York, NY: 1999. Analysis of Health Surveys. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chicharro JL, Lucía A, Pérez M, et al. Saliva composition and exercise. Sports Med. 1998;26:17–27. doi: 10.2165/00007256-199826010-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mulic A, Tveit AB, Songe D, et al. Dental erosive wear and salivary flow rate in physically active young adults. BMC Oral Health. 2012;12:8. doi: 10.1186/1472-6831-12-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.McGuire J, Szabo A, Jackson S, et al. Erosive tooth wear among children in the United States: relationship to race/ethnicity and obesity. Int J Paediatr Dent. 2009;19:91–98. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-263X.2008.00952.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tong HJ, Rudolf MC, Muyombwe T, et al. An investigation into the dental health of children with obesity: an analysis of dental erosion and caries status. Eur Arch Paediatr Dent. 2014;15:203–210. doi: 10.1007/s40368-013-0100-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Isaksson H, Birkhed D, Wendt LK, et al. Prevalence of dental erosion and association with lifestyle factors in Swedish 20-year olds. Acta Odontol Scand. 2014;72:448–457. doi: 10.3109/00016357.2013.859727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Forshee RA, Anderson PA, Storey ML. Sugar-sweetened beverages and body mass index in children and adolescents: a meta-analysis. Am J Clin Nutr. 2008;87:1662–1671. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/87.6.1662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]