Abstract

Purpose of Review

This review summarizes recent clinical trial research on pharmacological treatments for substance use disorders, with a specific focus on agents with potential abuse liability.

Recent Findings

Pharmacological treatments for substance use disorders may include gabapentinoids, baclofen, modafinil, ketamine, cannabinoids, gamma-hydroxybutyrate, and psychedelics. Gabapentinoids may decrease negative subjective effects of withdrawal in alcohol and cannabis use disorders. Cannabinoids similarly appear to decrease use and withdrawal symptoms in cannabis use disorder, while research shows stimulant medications may reduce cravings and increase abstinence in cocaine use disorder. Ketamine and psychedelics may help treat multiple substance use disorders. Ketamine may reduce withdrawal symptoms, promote abstinence, and diminish cravings in alcohol and cocaine use disorders and psychedelics may promote remission, decrease use, and reduce cravings in alcohol and opioid use disorders.

Summary

Regardless of current regulatory approval statuses and potentials for abuse, multiple agents should not be dismissed prematurely as possible treatments for substance use disorders. However, further clinical research is needed before effective implementation can begin in practice.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s40429-022-00432-9.

Keywords: Substance-related disorders, Addictive behaviors, Craving, Abuse liability, Alcohol, Cannabinoids, Cocaine, Opioids

Introduction

Many US individuals experience substance use disorders (SUDs) [1]. According to the 2020 National Survey of Drug Use and Health (NSDUH), 40.3 million people aged 12 years or older had an SUD. While statistics for use of alcohol or cocaine have remained relatively stable, use of drugs such as cannabis and methamphetamines have shown upward trends recently. In addition, and compounded by the COVID-19 pandemic, the rate of drug-related overdoses increased by 15.7% from 2019 to 2020, reaching an all-time 12-month high of 100,000 + deaths as of December 2021 [2].

These statistics underscore a need for new or better interventions for SUDs. While previous reviews have summarized the development of treatments [3–5], these reviews have either focused on a specific SUD, a single treatment, or a specific neurobiological target or pathway. One theme that emerges from prior reviews is the potential abuse liability inherent to some pharmacological candidates (i.e., substitution approaches such as methadone, buprenorphine, or stimulants). While an important consideration, once a drug is labeled as having potential abuse liability, its consideration as a possible treatment option is often dismissed by clinical practitioners. For example, because of their varying degrees of possible abuse liability, gabapentin [6, 7], pregabalin [8], baclofen [9, 10], and bupropion [11] may not be routinely used generally by some practitioners when treating SUDs, despite the frequent use of these agents in clinical practice.

In the present narrative review, we describe potential pharmacological treatments for the most prevalent SUDs and specifically focus on drugs with potential abuse liability. The review examines recent clinical trials for treatment of alcohol, cannabis, cocaine, and opioid use disorders. For each SUD, research on specific drugs with potential abuse liability is described, and followed by discussion of the evidence for and against clinical implementation of the treatments.

Methods

A literature search was conducted by searching the following databases on the Ovid platform: MEDLINE, Embase, and PsycInfo. Searches were limited to English language articles from the last 15 years. A librarian was consulted, and a precise textword search strategy was created so that relevant articles were retrieved. The textword search strings included terms for the drugs of abuse and their treatments of interest. In addition, the search was limited to clinical trials, systematic reviews, and meta-analyses using a modified version of the Cochrane Highly Sensitive Search Strategy. (See Supplementary Information for search strategies for all databases.)

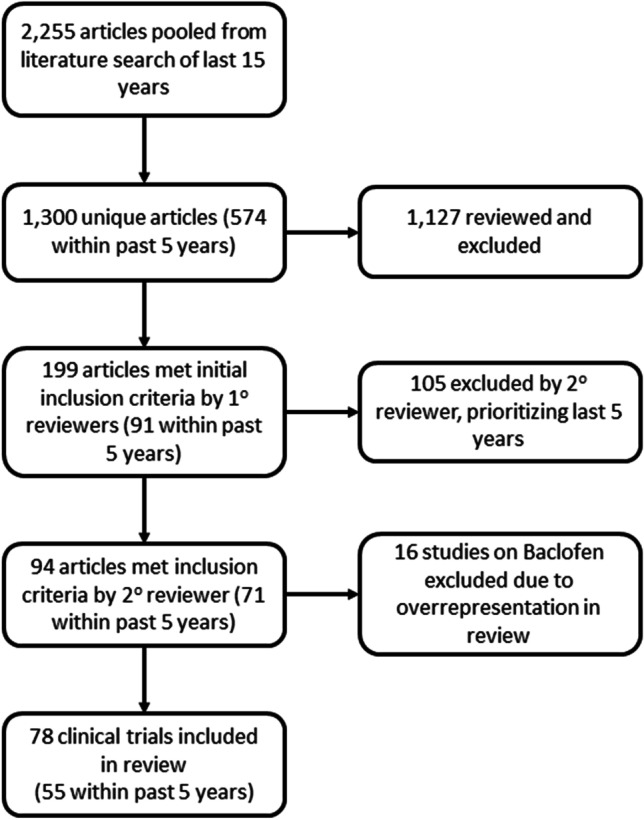

The final search retrieved a total of 2255 articles, which were pooled in EndNote and deduplicated [www.endnote.com]. The set of 1300 citations was uploaded to a Google Spreadsheet and tagged by each substance described in the article. Team members screened the title and abstract and determined whether to include or exclude the article based on relevance and whether or not study was a clinical trial. The full text of articles initially deemed potentially suitable was re-reviewed by one team member to determine inclusion in analyses. Articles published within the last 5 years were prioritized for inclusion in the review (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

The selection process of the articles included in the narrative review. After deduplication of articles found in the initial search, 1300 articles were reviewed by the authors. Of the initially selected articles, 199 met initial inclusion criteria and were reviewed again by one author. Articles within the last 5 years were prioritized for final inclusion, and 94 articles were deemed appropriate for inclusion in the review. Of note, baclofen as a potential treatment for AUD has been studied significantly more than the other pharmacological agents reviewed here. Due to its over-representation, 16 studies from 2017 to 2018 were further excluded from the final review

Alcohol Use Disorder (AUD)

Baclofen

A GABAB agonist hypothesized to modulate the mesolimbic reward system [12, 13•], baclofen has been reported to have some abuse liability [10]. Baclofen has been studied as a candidate treatment for AUD. Studies have demonstrated mixed results, with some finding baclofen a safe and effective intervention for abstinence promotion and maintenance [14], and others finding no significant difference between baclofen and placebo across a spectrum of end-points [15]. In the 2015 BACLAD study, 56 AUD participants were randomized to a double-blind treatment of either individually titrated baclofen (30–270 mg total daily dose) or placebo, and followed over the course of a 12-week “high dose” phase for effect on alcohol abstinence. Participants treated with baclofen were found to be significantly more likely to maintain abstinence from alcohol than those treated with placebo (15/22, 68.2% vs. 5/21, 23.8%, p = 0.014) [16]. The 2017 ALPADIR study attempted to replicate the BACLAD results, randomizing 320 AUD patients to either placebo (n = 162) or high-dose baclofen (n = 158, titration to baclofen 180 mg total daily dose maintenance). However, at the end of the 6-month study period, the authors observed no effect on abstinence. Notably, they observed a significant reduction in alcohol craving (p = 0.017) and consumption (p = 0.003) [17–19]. Follow-up analysis from the BACLAD group established that among subjects with alcoholic liver disease, baclofen increased both time to lapse and relapse, as well as percentage days abstinent (number needed to treat = 8.3) [20]. The authors further identified that high baseline alcohol consumption served as a positive predictor of baclofen’s benefit in AUD subjects [21]. Neuroimaging of alcohol cue-elicited functional activation in treatment-seeking individuals with AUD found that high dose (75 mg/day) baclofen was associated with decreased bilateral caudate nucleus and dorsal anterior cingulate activation in response to alcohol cues, and that deactivation of these areas was positively correlated with decreased heaving drinking days [22].

Gabapentinoids

Gabapentin, a GABA analogue, acts to potentiate GABA in the central nervous system [23], inhibit both glutamate synthesis and the functioning of sodium channels, modulate the alpha-2-delta subunit of voltage-gated calcium channels, and reduce the release of both dopamine and norepinephrine. Gabapentin has been reported to be abused, and such abuse may contribute to overdose deaths [6, 7]. The first full-scale 12-week, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of gabapentin involving 150 AUD adults found significant effects of gabapentin when compared to placebo, including elimination of heavy drinking and 12-week abstinence [24]. Specifically, the authors found that 1800 mg total daily dose had positive effects on abstinence (number needed to treat = 8, OR = 4.8), heavy drinking (number needed to treat = 5, OR = 2.8), decreases in average number of heavy drinking days per week, and total number of drinks consumed per week, compared to placebo. These effects were sustained at the study’s Week 24 follow-up encounter [24]. Similarly, a more recent study of 40 participants with AUD found that high-dose gabapentin (3600 mg/day) was associated with decreased number of heavy drinking days (p = 0.002) and increased percentage of days abstinent (p = 0.004) [25].

A separate randomized double-blind placebo-controlled study of 232 participants found no significant difference between extended-release gabapentin and placebo, hypothesizing that these results followed from any of several factors, including inadequacy of dosing, bioavailability of active drug in the setting of both alcohol use and suboptimal diet, and lack of nuance in the analysis [26]. In a randomized double-blind placebo-controlled trial of 44 participants treated with gabapentin, 12 (27%) reported no heavy-drinking days, as compared to 4 of the final 46 participants (9%) in the placebo group. Furthermore, 18% of gabapentin recipients reported total abstinence throughout the treatment period, as compared to 4% of placebo recipients. The authors qualified their results by noting that gabapentin produced stronger effects in participants with “high” withdrawal symptoms [27•].

Like gabapentin, pregabalin is a GABA analogue that may be abused. Pregabalin specifically binds to α2-δ1 and α2-δ2 calcium channel sub-units that attenuate the downstream release of excitatory neurotransmitters. Pregabalin is used to treat neuropathic pain, anxiety, and panic disorders, and has been studied for AUD. Following alcohol detoxification, individuals with AUD treated with pregabalin 150 mg daily in an outpatient treatment setting had higher retention in treatment (9.1 + / − 0.5 weeks) compared to placebo (7.1 + / − 0.5 weeks) [28]. Furthermore, individuals treated with pregabalin had decreased alcohol consumption, fewer heavy drinking days, and higher rates of abstinence. A meta-analysis by Cheng et al. found similar results in that pregabalin and gabapentin decreased percentage of heavy drinking (p = 0.0441) and symptoms of alcohol withdrawal (0.0425), compared to placebo [29••].

Ketamine

Ketamine is a commonly used clinical analgesic that has had increasing popularity as a recreational “club drug” since the 1990s. The precise mechanism of ketamine is not fully understood; however, NMDA antagonism may underlie its therapeutic benefit, similar to preclinical evidence from other NMDA antagonists [30]. As such, effects of ketamine may operate through glutamate systems that may be targeted in SUDs through multiple compounds including modulating drugs (e.g., mavoglurant) and nutraceuticals (e.g., n-acetyl cysteine). The effects of ketamine may extend beyond the glutamate system, with studies showing intravenous (IV) ketamine as an effective treatment for co-occurring AUD and major depressive disorder (MDD) or PTSD [31••]. In combination with 5 weeks of motivational enhancement therapy (MET), single-dose IV ketamine has also been found to significantly increase abstinence from alcohol, delay relapse and lower the likelihood of heavy drinking in AUD [32]. Furthermore, 3 ketamine infusions in combination with psychotherapy was found to significantly increase abstinence for 6 months following the last therapy session in individuals with AUD [33]. More acutely, ketamine infusions have also been found to reduce mean benzodiazepine (BZD) requirements for alcohol withdrawal [34]. Among patients with severe alcohol withdrawal symptoms and delirium tremens, those who were treated with IV ketamine at 0.15–0.3 mg/kg/h were less likely to be intubated and experience shorter intensive-care treatments [35].

Sodium Oxybate/GHB

Another “club drug,” gamma-hydroxybutyric acid (GHB), or its sodium salt (sodium oxybate), is a partial agonist of GABAB receptors [36]. Low doses of GHB can induce ethanol-like effects [37] and may compete for extra-synaptic GABAB receptors, suggesting a potential role for GHB in treating AUD [36]. Between 30 and 66% of GHB-treated AUD patients maintained total abstinence 3 months after drinking cessation [38]. Reviews in the last 5 years have noted alcohol-abstinence rates 34% higher for GHB treatment than for placebo [36] and reductions in alcohol consumption associated with GHB even if total abstinence was not achieved [39]. Additionally, GHB may be as effective as disulfiram and naltrexone (NTX) in the maintenance of abstinence in AUD [4, 40]. GHB may be particularly effective in preventing relapse associated with heavy drinking [41, 42]. Despite these potential benefits, GHB has a severe risk of intoxication and death when abused. However, to date, there has been no published data about related deaths when used for treatment of AUD. Clinical trials have had limited adverse events, with instances of abnormal cravings and abuse rare and limited to patients with co-occurring psychiatric conditions [39, 43], and these may constitute risk factors for craving and abuse of GHB [25].

Psychedelics

Psychedelics (a.k.a. hallucinogens or entheogens) are a class of psychoactive drugs whose primary mechanism of action may involve binding and activation of the 5-HT2a receptor [44••, 45]. “Classic” psychedelics include lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD), psilocybin and its metabolite psilocin, dimethyltryptamine (DMT), and mescaline. Synthetic compounds exist, as well as ibogaine, an indole alkaloid, and 3,4-Methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA or “molly”), a reuptake inhibitor at serotonin, dopamine and norepinphrine transporters, may be considered psychedelics given their subjective effects. The potential therapeutic use of psychedelics has been investigated for multiple psychiatric conditions including SUDs [46–48]. Thorough reviews of the literature of psychedelics in the treatment of SUDs have been previously published, with most finding that efficacy data, while promising, are limited due to the difficulty in researching these substances until very recently [49–51]. A meta-analyses of early studies of LSD for AUD found that following LSD administration, 59% of participants were significantly improved at 1 month post-LSD follow-up and alcohol use remained significantly decreased at 6-month follow-up, compared to decreased use in only 38% of control participants [52]. A survey of individuals with AUD found that following non-clinical psychedelic use, 83% reported no longer meeting AUD criteria [53]. Most participants described taking moderate-to-high doses of either LSD (38%) or psilocybin (36%), and reported that the experience facilitated their alcohol-use reduction by changing their life priorities or values. An open-label study among 10 AUD participants undergoing MET showed positive gains on abstinence, which were present at 36-week follow-up [54]. Despite the promising therapeutic effects of psychedelics, clinical trials for AUD are lacking.

MDMA-assisted psychotherapy has also been found to decrease alcohol consumption [55]. In one preliminary study, fourteen participants with AUD completed two sessions of MDMA-assisted psychotherapy and showed decreased alcohol consumption at 1 month follow-up (0.1 units of alcohol compared to 130.6 units of alcohol prior to MDMA therapy). The decrease in alcohol use was still significant at 9-month post-treatment, with participants drinking 18.7 units of alcohol on average, and nine of fourteen participants remaining completely abstinent.

Clinical Implementation

Recent studies of AUD treatment offer multiple options with varying degrees of clinical applicability. While baclofen showed initial promise, evidence for baclofen use in AUD appears increasingly constrained to specific-use cases. The most recent studies suggest that baclofen has the greatest benefit at higher doses, works best on craving, and works best for men with high baseline alcohol consumption [56], and perhaps particularly for those with alcoholic liver disease [57]. Given these limited applications for baclofen, and in light of the potential for both abuse [58] and overdose [20], it is challenging to advocate for baclofen as an early therapeutic intervention in AUD treatment.

Data support the use of gabapentinoids in AUD patients [59]. Gabapentin typically is well-tolerated, carries relatively low risk of adverse effects, helps with sleep disruption, and shows benefit in withdrawal and adjunctive benefit in anxiety. While gabapentin may be best suited for patients with high withdrawal-risk histories, co-occurring insomnia/anxiety, and possible concurrent treatment with naltrexone, it may provide enough benefit to shift cost–benefit analyses towards use in many patients. Similarly, pregabalin may decrease heavy drinking and alcohol withdrawal. Even at doses as high as 600 mg/day, adverse effects are relatively uncommon, with the most common being drowsiness [60]. Thus, the potential benefit of pregabalin in AUD largely outweighs the risks. As such, gabapentinoids are useful adjunctive medications for AUD treatment.

Ketamine and GHB offer promise in treating AUD. Both may increase abstinence, decrease drug use, and reduce feelings of craving. Ketamine may be particularly beneficial for individuals with histories of severe withdrawal [35]. However, both are limited by the need for more clinical trial data. Both ketamine and GHB may result in serious adverse consequences, including death, if used improperly. Logistical challenges for implementation such as supervised IV administration of ketamine, and standardized protocol for monitoring patient status must therefore also be addressed before being implemented successfully.

Like ketamine and GHB, early evidence suggests that psychedelics reduce cravings, decrease alcohol use, and may increase abstinence. Unlike ketamine and GHB, psychedelics are generally less addictive and relatively safe in terms of physical symptoms. Because of the intensity of the acute psychedelic experience, effective blinding during clinical trials is difficult if not impossible. Additionally, there is question whether traditional clinical trial protocols can effectively capture all of the factors contributing to psychedelic treatment outcomes. Finally, although grouped together in this review as “psychedelics,” research on AUD has been limited to LSD, MDMA, and recently psilocybin, which may have varying requirements for dosing supervision, harm potential, and efficacy in treating AUD. Thus, while these drugs may offer considerable potential for AUD treatment, significantly more research is needed before they may be implemented clinically.

Cannabis Use Disorder (CbUD)

Cannabinoid Agonists: Dronabinol and Nabilone

Currently, there are no medications approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to treat CbUD. The first cannabinoid agonist investigated for CbUD was dronabinol — an oral, synthetic formulation of tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) that is approved by the FDA (1) to treat chemotherapy-induced nausea; and, (2) to stimulate appetite among persons with HIV-related anorexia. A small (n = 14) placebo-controlled crossover study found that dronabinol significantly reduced self-administration of cannabis and suppresed withdrawal symptoms [61]. However, data from other phase 2 human laboratory studies and clinical trials suggest that while dronabinol may alleviate symptoms of cannabis withdrawal, it may not promote abstinence or reduce cannabis use [62–65].

Following dronabinol, the second cannabinoid agonist to be investigated for CbUD was nabilone, another THC analogue FDA-approved to treat nausea. Like dronabinol, nabilone (administered solo or in combination with zolpidem) reduced symptoms of cannabis withdrawal in human laboratory studies [66, 67, 68•]. Unlike dronabinol, nabilone also reduced cannabis self-administration in the laboratory, following a period of abstinence [66]. A 10-week randomized, placebo-controlled pilot clinical trial found that nabilone was safe and well-tolerated by persons with CbUD, but evidenced no difference in cannabis use between the nabilone and the placebo groups [69].

Nabiximols

Some of the other 70 currently known plant-based cannabinoids may also modify THC use. For example, cannabidiol (CBD), the second most abundant cannabinoid after THC, may have anxiolytic and neuroprotective effects that offset THC-induced anxiety and cognitive deficits [70]. In the first placebo-controlled trial testing the therapeutic efficacy of nabiximols, symptoms of cannabis withdrawal were reduced; however, there was no difference in cannabis use between the treatment and placebo groups [71]. In a subsequent pilot randomized, placebo-controlled clinical trial, nabiximols were examined in conjunction with MET and Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) among treatment-seeking persons with CbUD [72]. At 12-week follow-up, there was no difference in abstinence rates between the nabiximols and the placebo group; still, despite the absence of statistically significant differences in cannabis withdrawal scores, nabiximols appeared to reduce cannabis use, compared to placebo (70.5% vs. 42.6%). Finally, a multicenter randomized, placebo-controlled clinical trial tested the therapeutic efficacy of nabiximols, in conjunction with CBT-based counseling, among treatment-seeking persons with CbUD [73••]. This 12-week trial found that participants who received nabiximols reported significantly fewer days of cannabis use, without significant differences in adverse effects for up to 3 months following completion of nabiximols treatment [74].

Gabapentinoids

Gabapentin has also been tested to treat CbUD. One proof-of-concept 12-week randomized, placebo-controlled clinical trial examined effects of gabapentin among treatment-seeking persons with CbUD [75]. Compared to placebo, gabapentin (1200 mg/day) attenuated cannabis withdrawal and reduced cannabis use. Additionally, compared with participants who received placebo, participants who received gabapentin had better executive functioning and less negative affect. These cognitive/emotional effects may be due in part to gabapentin-induced changes to glutamate levels in the basal ganglia and activation of the posterior midcingulate cortex [76]. Pregabalin (300 or 450 mg/day) has also been studied as treatment for CbUD; however, no significant differences in use or remission were observed between pregabalin and placebo groups [77].

Ketamine

A recent small (n = 8) proof-of-concept trial found that IV infusion of ketamine (0.71 mg/kg or 1.41 mg/kg for non-responders) paired with MET and mindfulness-based relapse prevention significantly decreased and sustained reduced cannabis use for 6 weeks following infusion [78].

Clinical Implementation

Cannabinoid agonist treatments have been used to treat cannabis withdrawal syndrome, which is a recognized entity in the DSM-5 [63]. However, withdrawal suppression is typically not associated with improved long-term outcomes in the treatment of CbUD. Given their higher tolerability and likely lower abuse potential, nabiximols may hold particular therapeutic promise [79].

Taken together, evidence indicates that cannabinoid agonists may reduce withdrawal and cannabis use, but thus far there are no data indicating that they promote abstinence. Although there are early signs of efficacy for nabiximols, the dose-dependent efficacy of nabilone for CbUD remains to be tested in well-powered clinical trials.

There is preliminary evidence regarding the efficacy of gabapentin to reduce cannabis withdrawal and associated disruptions in sleep architecture. Although when compared to cannabinoid agonists, gabapentin is more widely used and generally perceived to have lower abuse liability, to our knowledge there are no drug discrimination studies comparing the abuse potential of these compounds among persons with CbUD.

Initial preliminary results of ketamine paired with behavioral therapy may decrease cannabis use. However, given that there was no control group, the therapeutic effects of ketamine vs. behavioral therapy cannot be ascertained, and larger placebo-controlled studies are needed.

While medications with lower abuse potential are in development, the efficacy and abuse potential of the existing medications may depend on the severity of CbUD and other clinical factors, such as the presence of other psychiatric disorders. Future research should investigate how to maximize therapeutic benefit while reducing abuse potential.

Cocaine Use Disorder (CUD)

Baclofen

CUD lacks an FDA-approved treatment. While research on baclofen as a potential therapeutic has been mixed, a recent randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of 25 men with CUD found that baclofen relative to placebo reduced neural activation in response to cocaine cues. Given that there were no between-group differences in neural response to sexual or aversive cues, a specificity of baclofen’s effect on drug cues was suggested [80].

Gabapentin

In 2019, a systematic review by Ahmed et al. concluded that the available evidence did not show that gabapentin produced any significant benefits with respect to cocaine craving, abstinence, treatment retention, or future use [81••]. Nonetheless, the review did not assess the question of relapse prevention.

Bupropion

Bupropion, a blocker of dopamine and norepinephrine reuptake, has shown abuse liability and mixed results in the treatment of CUD. With a chemical structure similar to amphetamines and cathinone, bupropion has demonstrated varying degrees of benefit, with one study showing no difference from placebo [82], and another finding potential benefit, but only in methadone-maintained men, and only in comparison to combined placebo and contingency management [83].

Modafinil

Modafinil is a blocker of dopamine re-uptake and an agonist at type II metabotropic glutamate receptors (mGluR2/3) that regulate extracellular glutamate levels and glutamate release in response to external stimuli. Modafinil induces a lower response on the amphetamine scale of the addiction research center inventory, and though it has abuse potential, it is lower than that of amphetamine [84].

Modafinil may normalize slow wave sleep in CUD and is associated with improved clinical outcomes, including cocaine-free urine toxicology [84]. Despite promise in human laboratory studies showing modafinil reducing cocaine self-administration and subjective positive effects of cocaine [85, 86], other findings are mixed. Secondary analyses of negative trials originally suggested that modafinil may be effective in subgroups of CUD such as that without co-occurring AUD [87] and in preventing relapse rather than maintaining abstinence [88]. Subsequent efforts at replicating these findings have been less successful [89–91].

Stimulants

Non-cocaine stimulants have been tested as potential treatments for CUD. Research testing lisdexamphetamine dimesylate for the treatment of CUD suggested reductions in craving but not in cocaine use, compared to placebo [92].

Studies of amphetamine in CUD patients include CUD with and without co-occurring opioid use disorder (OUD) [93, 94••] and co-occurring attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). This latter comorbidity is important as ADHD is overrepresented among CUD, and co-occurring ADHD and CUD is associated with poor long-term treatment outcomes [95].

Studies on stimulant efficacy for co-occurring CUD/ADHD have been inconclusive. In one study examining treatment efficacy of sustained-release methylphenidate, no significant benefits were found for ADHD, nor for primary outcomes of CUD; however, participants who showed improvement of ADHD symptoms with methylphenidate were additionally found to have fewer positive urine drug screens compared to non-responders [96]. A separate study tested higher doses of sustained-released amphetamine at 60 or 80 mg/day, in addition to CBT, and found improved treatment outcomes for both ADHD and CUD [97]. Higher doses of amphetamines appeared to offer more benefit for CUD while the lower dose was more beneficial for ADHD. A secondary analysis found that a particular subgroup of participants had longer periods of cocaine abstinence without improvement in ADHD symptoms, while in another subgroup, improvement in ADHD symptoms preceded and appeared to influence benefit in CUD symptoms [97].

Among individuals with co-occurring CUD and OUD who were undergoing heroin-assisted treatment, sustained-release dextroamphetamine was well tolerated and was associated with low attrition [93]. However, a recent systematic review by Chan et al. found that while cocaine-free urinalyses occurred more frequently with psychostimulants than placebo, the difference was not statistically significant [94••].

Ketamine

Preliminary clinical studies suggest efficacy of ketamine for treating CUD. A single, IV injection of ketamine (vs. lorazepam) increased motivation to quit and decreased cue-induced cravings [98]. A recent prospective, randomized, active placebo (midazolam) controlled trial found that a single IV injection of 0.5 mg/kg ketamine and mindfulness-based behavioral modification (MBBM) produced statistically significant and clinically superior outcomes, including prolonged times to relapse and fourfold higher end-of-trial abstinence rates, compared to midazolam [32, 99]. Additionally, subjective experience of mysticism during IV ketamine infusion was found to mediate effects of ketamine on decreased cocaine use and craving [100]. Notwithstanding promising preliminary clinical work in support for ketamine, its psychotomimetic effects and potential for abuse are important considerations.

Clinical Implementation

Further study of baclofen is warranted based on early results. While preclinical work has provided weak evidence of benefit and meta-analyses are not supporting clinical benefits [101], recent studies suggest potential benefits for cue exposure. Clinicians should be aware of baclofen’s abuse potential.

While the use of gabapentin for CUD lacks compelling support, the combination of (1) subjective benefit, (2) good tolerance, and (3) low adverse-effect profile leaves open the possibility of using gabapentin in CUD. Additionally, gabapentin helps to restore sleep architecture in CUD [90], albeit with a risk of habit formation.

Studies of bupropion and modafinil have found that both decreased the amount of urine-positive drug screens, but neither has been found to have substantial benefit in decreasing craving, relapse, or the subjective effects of cocaine in clinical trials. Stimulants, however, do appear to lower cravings and increase length of abstinence. There may be a particular clinical application of these medications in the use of treating CUD with co-occurring ADHD, but additional studies are needed to further confirm the exact benefit of these medications in individuals with dual diagnoses. Additionally, the potential for abuse of stimulant medications — especially in individuals with CUD — warrants caution when prescribing these medications.

Ketamine and psychedelic drugs may offer promise for treating CUD based on preclinical and observational studies. However, larger clinical trials appear needed before they may be recommended for use in non-research settings.

Opioid Use Disorder (OUD)

Ketamine

Given ketamine’s neuroplastic effects, it may augment psychotherapeutic interventions. One open-label study investigated dose-dependent effects of intramuscular ketamine, combined with psychotherapy, among persons with OUD [102]. Both the dissociative (2.0 mg/kg) and the non-dissociative (0.2 mg/kg) doses of ketamine reduced opioid craving, promoted longer abstinence, and were associated with positive changes in emotional attitudes [102]. In a follow-up study, repeated treatment sessions were associated with more frequent abstinence a year following treatment [103]. Additionally, administration of a single dose (IV or intranasal) of ketamine following surgical procedures may reduce opioid consumption for pain during recovery [104–107].

Psychedelics

Observational evidence suggests an association between psychedelic use and less opioid use. In 44,000 individuals using illicit opioids, those who used psychedelics had a 27% reduced odds of past-year opioid dependence and a 40% reduced odds of past-year opioid abuse when controlling for demographic variables and other drug use [108]. Online surveys of naturalistic use of psychedelics in non-clinical settings suggest less opioid use [109]. Additionally, psychedelic use has been associated with lower suicidal ideation and fewer suicide attempts among marginalized women who were prescribed opioids [110].

In particular, the psychedelic ibogaine has shown promise as a potential treatment for OUD [111]. Among 30 individuals with OUD, following administration of ibogaine, 50% of individuals remained abstinent from opioids at one month, and 23% of individuals continued to remain abstinent at 12 months [112]. Additional randomized, placebo-controlled clinical trials with control groups are needed to assess the efficacy of ibogaine.

Clinical Implementation

Ketamine appears to offer potential benefit in managing pain and opioid withdrawal, processes that may drive further opioid use. However, further work is needed to establish the efficacy of ketamine treatment for OUD, especially in light of ketamine’s abuse potential. Preliminary evidence indicates that psychedelics, and notably ibogaine, may offer potential in the treatment of OUD, and further randomized double-blind placebo-controlled trials are needed to formally assess efficacy and tolerability.

Conclusions

Pharmacological agents with potential abuse liability offer promise for treating SUDs. This narrative review assesses recent studies on such agents. While some agents such as gabapentin, baclofen, and modafinil are already available for use by clinicians, other treatments such as ketamine and cannabinoids are limited in their approved uses, and GHB and psychedelics have no FDA approval. Regardless of their current FDA approval statuses and potentials for abuse, these agents should not be dismissed with respect to potential treatment of SUDs.

Gabapentin, for example, may improve sleep and decrease negative subjective effects of withdrawal in AUD and CbUD with little additional risk to patients. Its ability to reduce discomfort associated with withdrawal makes gabapentin a worthwhile consideration for treating individuals who have recently stopped using alcohol and cannabis. Nabiximols appear to decrease use and withdrawal symptoms in CbUD, although it is less clear that they may promote abstinence. At the very least, off-label use may be considered for individuals with severe, treatment-refractory CbUD. Stimulant medications may reduce cravings and increase abstinence in CUD, especially in individuals with co-occurring ADHD. Although it may initially seem counterintuitive to treat CUD with a stimulant, this substitution approach is gaining neurobiological support based on chronic hypodopaminergic states after chronic cocaine use. Concerns about diversion could be mitigated in similar ways as with other substitution approaches (i.e., frequent monitoring of urine toxicology, using prescription monitoring databases, etc.).

Ketamine and psychedelics may offer benefits in treating multiple SUDs. Ketamine may reduce withdrawal symptoms, promote abstinence, and reduce cravings in AUD and CUD (especially when paired with therapy), and also reduce pain, discomfort, and cravings associated with OUD withdrawal. Psychedelics appear to promote durable remission, decrease use, and reduce cravings in AUD and OUD. However, these agents are limited by the lack of clinical trials in SUD populations. Although ketamine is now FDA-approved for treatment-resistant depression, and psilocybin and MDMA are being studied for treatment of PTSD and major depression, more studies of clinical outcomes are needed to investigate potential risks and benefits for use in SUDs.

Although the agents reviewed here all have therapeutic potential, there is still much knowledge to gain and further clinical research to be completed before effective implementation in practice. For instance, studies exploring and/or showing alterations in synaptic density across several SUDs motivates exploration of psychedelics and ketamine’s synaptotropic properties as potential mechanism of action [113, 114]. We do not yet have comparisons of efficacies between potential treatments, nor do we know how their potential for abuse may impact therapeutic benefits in individuals with SUDs. Additionally, as these pharmacologic agents are employed by clinicians, it should be established whether they constitute 1st, 2nd, or 3rd line treatments. Clinical trials with greater power in diverse groups of participants that compare multiple treatment arms are needed to investigate further the therapeutic effects of drugs with abuse potential.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

The work described in this article (or chapter or book) was funded in part by the State of Connecticut, Department of Mental Health and Addiction Services, but this publication does not express the views of the Department of Mental Health and Addiction Services or the State of Connecticut. The views and opinions expressed are those of the authors.

Funding

This work was funded by the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) award R25MH071584-14 (BM), The National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) awards R01 DA052454-01A1 (GAA, MNP), R21 1DA046030-02 (GAA), R21 DA043055 (GAA, MNP), and K23DA052682 (JPD). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIMH or NIDA.

Declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. Dr. Potenza has consulted for Opiant Therapeutics, Game Day Data, Baria-Tek, the Addiction Policy Forum, AXA and Idorsia Pharmaceuticals; has been involved in a patent application with Yale University and Novartis; has received research support from Mohegan Sun Casino and the National Center for Responsible Gaming; has participated in surveys, mailings or telephone consultations related to drug addiction, impulse-control disorders or other health topics; has consulted for and/or advised gambling and legal entities on issues related to impulse-control/addictive disorders; has provided clinical care in a problem gambling services program; has performed grant reviews for research-funding agencies; has edited journals and journal sections; has given academic lectures in grand rounds, CME events and other clinical or scientific venues; and has generated books or book chapters for publishers of mental health texts. The other authors do not report disclosures.

Footnotes

This article is part of the Topical Collection on Illicit Drugs in Therapy

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as: • Of importance •• Of major importance

- 1.Key substance use and mental health indicators in the United States: results from the 2020 national survey on drug use and health. 2020;156

- 2.Products - vital statistics rapid release - provisional drug overdose data [Internet]. 2022 [cited 2022 Apr 28]. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nvss/vsrr/drug-overdose-data.htm

- 3.Sloan ME, Gowin JL, Ramchandani VA, Hurd YL, Le Foll B. The endocannabinoid system as a target for addiction treatment: trials and tribulations. Neuropharmacology. 2017;124:73–83. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2017.05.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Volkow ND, Jones EB, Einstein EB, Wargo EM. Prevention and treatment of opioid misuse and addiction: a review. JAMA Psychiat. 2019;76:208–216. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2018.3126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Witkiewitz K, Litten RZ, Leggio L. Advances in the science and treatment of alcohol use disorder. Sci Adv Am Assoc Adv Sci. 2019;5:eaax4043. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.aax4043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Smith BH, Higgins C, Baldacchino A, Kidd B, Bannister J. Substance misuse of gabapentin. Br J Gen Pract. 2012;62:406–407. doi: 10.3399/bjgp12X653516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gomes T, Juurlink DN, Antoniou T, Mamdani MM, Paterson JM, van den Brink W. Gabapentin, opioids, and the risk of opioid-related death: a population-based nested case–control study. PLOS Medicine. Public Library of Science. 2017;14:e1002396. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1002396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schifano F. Misuse and abuse of pregabalin and gabapentin: cause for concern? CNS Drugs. 2014;28:491–496. doi: 10.1007/s40263-014-0164-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Das S, Palappalllil DS, Purushothaman ST, Rajan V. An unusual case of baclofen abuse. Indian J Psychol Med. 2016;38:475–476. doi: 10.4103/0253-7176.191383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ghosh S, Bhuyan D. Baclofen abuse due to its hypomanic effect in patients with alcohol dependence and comorbid major depressive disorder. Clinical Psychopharmacology and Neuroscience. Korean College Neuropsychopharmacol. 2017;15:187–9. doi: 10.9758/cpn.2017.15.2.187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stall N, Godwin J, Juurlink D. Bupropion abuse and overdose. CMAJ. 2014;186:1015. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.131534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Morley KC, Logge WB, Fraser I, Morris RW, Baillie AJ, Haber PS. High-dose baclofen attenuates insula activation during anticipatory anxiety in treatment-seeking alcohol dependant individuals: Preliminary findings from a pharmaco-fMRI study. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2021;46:28–36. doi: 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2021.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Farokhnia M, Deschaine SL, Sadighi A, Farinelli LA, Lee MR, Akhlaghi F, et al. A deeper insight into how GABA-B receptor agonism via baclofen may affect alcohol seeking and consumption: lessons learned from a human laboratory investigation. Mol Psychiatry Nature Publishing Group. 2021;26:545–555. doi: 10.1038/s41380-018-0287-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Addolorato G, Leggio L, Ferrulli A, Cardone S, Vonghia L, Mirijello A, et al. Effectiveness and safety of baclofen for maintenance of alcohol abstinence in alcohol-dependent patients with liver cirrhosis: randomised, double-blind controlled study. Lancet. 2007;370:1915–1922. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61814-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Garbutt JC, Kampov-Polevoy AB, Gallop R, Kalka-Juhl L, Flannery BA. Efficacy and safety of baclofen for alcohol dependence: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2010;34:1849–1857. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2010.01273.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Müller CA, Geisel O, Pelz P, Higl V, Krüger J, Stickel A, et al. High-dose baclofen for the treatment of alcohol dependence (BACLAD study): a randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2015;25:1167–1177. doi: 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2015.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Reynaud M, Aubin H-J, Trinquet F, Zakine B, Dano C, Dematteis M, et al. A randomized, placebo-controlled study of high-dose baclofen in alcohol-dependent patients-the ALPADIR study. Alcohol Alcohol. 2017;52:439–446. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agx030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rigal L, Sidorkiewicz S, Tréluyer J-M, Perrodeau E, Le Jeunne C, Porcher R, et al. Titrated baclofen for high-risk alcohol consumption: a randomized placebo-controlled trial in out-patients with 1-year follow-up. Addiction. 2020;115:1265–1276. doi: 10.1111/add.14927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Andrade C. Individualized, high-dose baclofen for reduction in alcohol intake in persons with high levels of consumption. J Clin Psychiatry Physicians Postgraduate Press Inc. 2020;81:8187. doi: 10.4088/JCP.20f13606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Morley KC, Baillie A, Fraser I, Furneaux-Bate A, Dore G, Roberts M, et al. Baclofen in the treatment of alcohol dependence with or without liver disease: multisite, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Br J Psychiatry. 2018;212:362–369. doi: 10.1192/bjp.2018.13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rombouts SA, Baillie A, Haber PS, Morley KC. Clinical predictors of response to baclofen in the treatment of alcohol use disorder: results from the BacALD trial. Alcohol Alcohol. 2019;54:272–278. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agz026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Logge WB, Morris RW, Baillie AJ, Haber PS, Morley KC. Baclofen attenuates fMRI alcohol cue reactivity in treatment-seeking alcohol dependent individuals. Psychopharmacology. 2021;238:1291–1302. doi: 10.1007/s00213-019-05192-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Prisciandaro JJ, Hoffman M, Brown TR, Voronin K, Book S, Bristol E, et al. Effects of gabapentin on dorsal anterior cingulate cortex GABA and glutamate levels and their associations with abstinence in alcohol use disorder: a randomized clinical trial. AJP Am Psychiatric Publish. 2021;178:829–837. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2021.20121757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mason BJ, Quello S, Goodell V, Shadan F, Kyle M, Begovic A. Gabapentin treatment for alcohol dependence: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174:70–77. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.11950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mariani JJ, Pavlicova M, Basaraba C, Mamczur-Fuller A, Brooks DJ, Bisaga A, et al. Pilot randomized placebo-controlled clinical trial of high-dose gabapentin for alcohol use disorder. Alcoholism Clin Exp Res. 2021;45:1639–52. doi: 10.1111/acer.14648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Falk DE, Ryan ML, Fertig JB, Devine EG, Cruz R, Brown ES, et al. Gabapentin enacarbil extended-release for alcohol use disorder: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multisite trial assessing efficacy and safety. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2019;43:158–169. doi: 10.1111/acer.13917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Anton RF, Latham P, Voronin K, Book S, Hoffman M, Prisciandaro J, et al. Efficacy of gabapentin for the treatment of alcohol use disorder in patients with alcohol withdrawal symptoms: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2020;180:728–736. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.0249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Krupitsky EM, Rybakova KV, Skurat EP, Semenova NV. Neznanov NG [A double blind placebo controlled randomized clinical trial of the efficacy and safety of pregabalin in induction of remission in patients with alcohol dependence] Zh Nevrol Psikhiatr Im S S Korsakova. 2020;120:33–43. doi: 10.17116/jnevro202012001133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cheng Y-C, Huang Y-C, Huang W-L. Gabapentinoids for treatment of alcohol use disorder: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Hum Psychopharmacol Clin Exp. 2020;35:e2751. doi: 10.1002/hup.2751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Strong CE, Kabbaj M. Neural mechanisms underlying the rewarding and therapeutic effects of ketamine as a treatment for alcohol use disorder. Frontiers in Behavioral Neuroscience [Internet]. 2020 [cited 2022 Mar 18];14. Available from: https://www.frontiersin.org/article/10.3389/fnbeh.2020.593860 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 31.Worrell SD, Gould TJ. Therapeutic potential of ketamine for alcohol use disorder. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2021;126:573–589. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2021.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dakwar E, Levin F, Hart CL, Basaraba C, Choi J, Pavlicova M, et al. A single ketamine infusion combined with motivational enhancement therapy for alcohol use disorder: a randomized midazolam-controlled pilot trial. AJP American Psychiatric Publishing. 2020;177:125–133. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2019.19070684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Grabski M, McAndrew A, Lawn W, Marsh B, Raymen L, Stevens T, et al. Adjunctive ketamine with relapse prevention-based psychological therapy in the treatment of alcohol use disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2022;179:152–162. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2021.21030277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jones JL, Mateus CF, Malcolm RJ, Brady KT, Back SE. Efficacy of ketamine in the treatment of substance use disorders: a systematic review. Front Psychiatry [Internet]. Frontiers; 2018 [cited 2021 Jul 14];9. Available from: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyt.2018.00277/full [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 35.Pizon AF, Lynch MJ, Benedict NJ, Yanta JH, Frisch A, Menke NB, et al. Adjunct ketamine use in the management of severe ethanol withdrawal. Crit Care Med. 2018;46:e768. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000003204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.van den Brink W, Addolorato G, Aubin H-J, Benyamina A, Caputo F, Dematteis M, et al. Efficacy and safety of sodium oxybate in alcohol-dependent patients with a very high drinking risk level. Addict Biol. 2018;23:969–986. doi: 10.1111/adb.12645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Skala K, Caputo F, Mirijello A, Vassallo G, Antonelli M, Ferrulli A, et al. Sodium oxybate in the treatment of alcohol dependence: from the alcohol withdrawal syndrome to the alcohol relapse prevention. Expert Opinion on Pharmacotherapy. Taylor & Francis. 2014;15:245–57. doi: 10.1517/14656566.2014.863278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Keating GM. Sodium oxybate: a review of its use in alcohol withdrawal syndrome and in the maintenance of abstinence in alcohol dependence. Clin Drug Investig. 2014;34:63–80. doi: 10.1007/s40261-013-0158-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Caputo F, Vignoli T, Tarli C, Domenicali M, Zoli G, Bernardi M, et al. A brief up-date of the use of sodium oxybate for the treatment of alcohol use disorder International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute. 2016;13:290. doi: 10.3390/ijerph13030290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Leone MA, Vigna‐Taglianti F, Avanzi G, Brambilla R, Faggiano F. Gamma‐hydroxybutyrate (GHB) for treatment of alcohol withdrawal and prevention of relapses. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews [Internet]. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd; 2010 [cited 2021 Jul 11]; Available from: https://www.cochranelibrary.com/cdsr/doi/10.1002/14651858.CD006266.pub2/full [DOI] [PubMed]

- 41.Mannucci C, Pichini S, Spagnolo EV, Calapai F, Gangemi S, Navarra M, et al. Sodium oxybate therapy for alcohol withdrawal syndrome and keeping of alcohol abstinence. Curr Drug Metab. 2018;19:1056–1064. doi: 10.2174/1389200219666171207122227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Guiraud J, Addolorato G, Aubin H-J, Batel P, de Bejczy A, Caputo F, et al. Treating alcohol dependence with an abuse and misuse deterrent formulation of sodium oxybate: results of a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2021;52:18–30. doi: 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2021.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Addolorato G, Lesch O-M, Maremmani I, Walter H, Nava F, Raffaillac Q, et al. Post-marketing and clinical safety experience with sodium oxybate for the treatment of alcohol withdrawal syndrome and maintenance of abstinence in alcohol-dependent subjects. Expert Opinion on Drug Safety. Taylor & Francis. 2020;19:159–66. doi: 10.1080/14740338.2020.1709821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Vollenweider FX, Preller KH. Psychedelic drugs: neurobiology and potential for treatment of psychiatric disorders. Nature Reviews Neuroscience Nature Publishing Group. 2020;21:611–624. doi: 10.1038/s41583-020-0367-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mertens LJ, Preller KH. Classical psychedelics as therapeutics in psychiatry – current clinical evidence and potential therapeutic mechanisms in substance use and mood disorders. Pharmacopsychiatry Georg Thieme Verlag KG. 2021;54:176–190. doi: 10.1055/a-1341-1907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Morgan C. Tripping up addiction: the use of psychedelic drugs in the treatment of problematic drug and alcohol use. Curr Opinion in Behav Sci 2017;6

- 47.Chi T, Gold JA. A review of emerging therapeutic potential of psychedelic drugs in the treatment of psychiatric illnesses. J Neurol Sci. 2020;411:116715. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2020.116715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rucker JJH, Iliff J, Nutt DJ. Psychiatry & the psychedelic drugs. Past, present & future. Neuropharmacology. 2018;142:200–18. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2017.12.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bogenschutz MP, Johnson MW. Classic hallucinogens in the treatment of addictions. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2016;64:250–258. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2015.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.DiVito AJ, Leger RF. Psychedelics as an emerging novel intervention in the treatment of substance use disorder: a review. Mol Biol Rep. 2020;47:9791–9799. doi: 10.1007/s11033-020-06009-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Dos Santos RG, Bouso JC, Alcázar-Córcoles MÁ, Hallak JE. Efficacy tolerability, and safety of serotonergic psychedelics for the management of mood, anxiety, and substance-use disorders: a systematic review of systematic reviews. Expert review of clinical pharmacology. Taylor & Francis. 2018;11:889–902. doi: 10.1080/17512433.2018.1511424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Krebs TS, Johansen P-Ø. Lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD) for alcoholism: meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Psychopharmacol SAGE Publications Ltd STM. 2012;26:994–1002. doi: 10.1177/0269881112439253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Garcia-Romeu A, Davis AK, Erowid F, Erowid E, Griffiths RR, Johnson MW. Cessation and reduction in alcohol consumption and misuse after psychedelic use. J Psychopharmacol SAGE Publications Ltd STM. 2019;33:1088–1101. doi: 10.1177/0269881119845793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Bogenschutz MP, Forcehimes AA, Pommy JA, Wilcox CE, Barbosa PCR, Strassman RJ. Psilocybin-assisted treatment for alcohol dependence: a proof-of-concept study. J Psychopharmacol. 2015;29:289–299. doi: 10.1177/0269881114565144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sessa B, Higbed L, O’Brien S, Durant C, Sakal C, Titheradge D, et al. First study of safety and tolerability of 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine-assisted psychotherapy in patients with alcohol use disorder. J Psychopharmacol. SAGE Publications Ltd STM; 2021;0269881121991792. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 56.Garbutt JC, Kampov-Polevoy AB, Pedersen C, Stansbury M, Jordan R, Willing L, et al. Efficacy and tolerability of baclofen in a U.S. community population with alcohol use disorder: a dose-response, randomized, controlled trial. Neuropsychopharmacol. Nature Publishing Group. 2021;46:2250–6. doi: 10.1038/s41386-021-01055-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kumar A, Sharma A, Bansal PD, Bahetra M, Gill HK, Kumar R. A comparative study on the safety and efficacy of naltrexone versus baclofen versus acamprosate in the management of alcohol dependence. Indian J Psychiatry. 2020;62:650–658. doi: 10.4103/psychiatry.IndianJPsychiatry_201_19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Tamama K, Lynch MJ. Newly emerging drugs of abuse. Handb Exp Pharmacol. 2020;258:463–502. doi: 10.1007/164_2019_260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kranzler HR, Feinn R, Morris P, Hartwell EE. A meta-analysis of the efficacy of gabapentin for treating alcohol use disorder. Addiction. 2019;114:1547–1555. doi: 10.1111/add.14655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Mariani JJ, Pavlicova M, Choi CJ, Brooks DJ, Mahony AL, Kosoff Z, et al. An open-label pilot study of pregabalin pharmacotherapy for alcohol use disorder. The American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse. Taylor & Francis. 2021;47:467–75. doi: 10.1080/00952990.2021.1901105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Schlienz NJ, Lee DC, Stitzer ML, Vandrey R. The effect of high-dose dronabinol (oral THC) maintenance on cannabis self-administration. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2018;187:254–260. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2018.02.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Haney M, Hart CL, Vosburg SK, Comer SD, Reed SC, Foltin RW. Effects of THC and lofexidine in a human laboratory model of marijuana withdrawal and relapse. Psychopharmacology. 2008;197:157–168. doi: 10.1007/s00213-007-1020-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Budney AJ, Vandrey RG, Hughes JR, Moore BA, Bahrenburg B. Oral delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol suppresses cannabis withdrawal symptoms. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2007;86:22–29. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2006.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Vandrey R, Stitzer ML, Mintzer MZ, Huestis MA, Murray JA, Lee D. The dose effects of short-term dronabinol (oral THC) maintenance in daily cannabis users. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2013;128:64–70. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2012.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Levin FR, Mariani JJ, Brooks DJ, Pavlicova M, Cheng W, Nunes EV. Dronabinol for the treatment of cannabis dependence: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2011;116:142–150. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2010.12.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Haney M, Cooper ZD, Bedi G, Vosburg SK, Comer SD, Foltin RW. Nabilone decreases marijuana withdrawal and a laboratory measure of marijuana relapse. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2013;38:1557–1565. doi: 10.1038/npp.2013.54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Herrmann ES, Cooper ZD, Bedi G, Ramesh D, Reed SC, Comer SD, et al. Effects of zolpidem alone and in combination with nabilone on cannabis withdrawal and a laboratory model of relapse in cannabis users. Psychopharmacology. 2016;233:2469–2478. doi: 10.1007/s00213-016-4298-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Herrmann ES, Cooper ZD, Bedi G, Ramesh D, Reed SC, Comer SD, et al. Varenicline and nabilone in tobacco and cannabis co-users: effects on tobacco abstinence, withdrawal and a laboratory model of cannabis relapse. Addict Biol. 2019;24:765–776. doi: 10.1111/adb.12664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Hill KP, Palastro MD, Gruber SA, Fitzmaurice GM, Greenfield SF, Lukas SE, et al. Nabilone pharmacotherapy for cannabis dependence: a randomized, controlled pilot study. Am J Addict. 2017;26:795–801. doi: 10.1111/ajad.12622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Boggs DL, Nguyen JD, Morgenson D, Taffe MA, Ranganathan M. Clinical and preclinical evidence for functional interactions of cannabidiol and Δ 9 -tetrahydrocannabinol. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2018;43:142–154. doi: 10.1038/npp.2017.209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Allsop DJ, Copeland J, Lintzeris N, Dunlop AJ, Montebello M, Sadler C, et al. A randomized controlled trial of nabiximols (Sativex®) as an agonist replacement therapy during cannabis withdrawal. JAMA Psychiat. 2014;71:281–291. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2013.3947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Trigo JM, Soliman A, Quilty LC, Fischer B, Rehm J, Selby P, et al. Nabiximols combined with motivational enhancement/cognitive behavioral therapy for the treatment of cannabis dependence: a pilot randomized clinical trial. PLOS ONE. Public Library Sci. 2018;13:e0190768. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0190768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Lintzeris N, Bhardwaj A, Mills L, Dunlop A, Copeland J, McGregor I, et al. Nabiximols for the treatment of cannabis dependence: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2019;179:1242–1253. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2019.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Lintzeris N, Mills L, Dunlop A, Copeland J, Mcgregor I, Bruno R, et al. Cannabis use in patients 3 months after ceasing nabiximols for the treatment of cannabis dependence: results from a placebo-controlled randomised trial. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2020;215:108220. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2020.108220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Mason BJ, Crean R, Goodell V, Light JM, Quello S, Shadan F, et al. A proof-of-concept randomized controlled study of gabapentin: effects on cannabis use, withdrawal and executive function deficits in cannabis-dependent adults. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2012;37:1689–1698. doi: 10.1038/npp.2012.14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Prisciandaro JJ, Mellick W, Squeglia LM, Hix S, Arnold L, Tolliver BK. Results from a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, crossover, multimodal-MRI pilot study of gabapentin for co-occurring bipolar and cannabis use disorders. Addict Biol. 2022;27:e13085. doi: 10.1111/adb.13085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Lile JA, Alcorn JL, Hays LR, Kelly TH, Stoops WW, Wesley MJ, et al. Influence of pregabalin maintenance on cannabis effects and related behaviors in daily cannabis users. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology. US: American Psychological Association; 2021;No Pagination Specified-No Pagination Specified. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 78.Azhari N, Hu H, O’Malley KY, Blocker ME, Levin FR, Dakwar E. Ketamine-facilitated behavioral treatment for cannabis use disorder: a proof of concept study. The American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse. Taylor & Francis. 2021;47:92–7. doi: 10.1080/00952990.2020.1808982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.D’Souza DC, Cortes-Briones J, Creatura G, Bluez G, Thurnauer H, Deaso E, et al. Efficacy and safety of a fatty acid amide hydrolase inhibitor (PF-04457845) in the treatment of cannabis withdrawal and dependence in men: a double-blind, placebo-controlled, parallel group, phase 2a single-site randomised controlled trial. The Lancet Psychiatry. 2019;6:35–45. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(18)30427-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Young KA, Franklin TR, Roberts DC, Jagannathan K, Suh JJ, Wetherill RR, et al. Nipping cue reactivity in the bud: baclofen prevents limbic activation elicited by subliminal drug cues. J Neurosci Soc Neurosci. 2014;34:5038–5043. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4977-13.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.•• Ahmed S, Bachu R, Kotapati P, Adnan M, Ahmed R, Farooq U, et al. Use of gabapentin in the treatment of substance use and psychiatric disorders: a systematic review. Frontiers in Psychiatry [Internet]. 2019 [cited 2022 Mar 18];10. Available from: https://www.frontiersin.org/article, 10.3389/fpsyt.2019.00228. This important review concluded that gabapentin is effective for mild to moderate acute alcohol withdrawal by reducing cravings, improving the rate of abstinence, and delaying return to heavy drinking. The review also suggests that gabapentin is more effective as an adjunctive medication rather than a monotherapy. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 82.Shoptaw S, Heinzerling KG, Rotheram-Fuller E, Kao UH, Wang P-C, Bholat MA, et al. Bupropion hydrochloride versus placebo, in combination with cognitive behavioral therapy, for the treatment of cocaine abuse/dependence. Journal of addictive diseases. Taylor & Francis. 2008;27:13–23. doi: 10.1300/J069v27n01_02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Poling J, Oliveto A, Petry N, Sofuoglu M, Gonsai K, Gonzalez G, et al. Six-month trial of bupropion with contingency management for cocaine dependence in a methadone-maintained population. Archives of general psychiatry. Am Med Assoc. 2006;63:219–28. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.63.2.219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Morgan PT, Angarita GA, Canavan S, Pittman B, Oberleitner L, Malison RT, et al. Modafinil and sleep architecture in an inpatient–outpatient treatment study of cocaine dependence. Drug Alcohol Dependence Elsevier. 2016;160:49–56. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2015.12.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Hart CL, Haney M, Vosburg SK, Rubin E, Foltin RW. Smoked cocaine self-administration is decreased by modafinil. Neuropsychopharmacol Nature Publishing Group. 2008;33:761–768. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1301472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Malcolm R, Swayngim K, Donovan JL, DeVane CL, Elkashef A, Chiang N, et al. Modafinil and cocaine interactions. The American journal of drug and alcohol abuse. Taylor & Francis. 2006;32:577–87. doi: 10.1080/00952990600920425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Anderson AL, Reid MS, Li S-H, Holmes T, Shemanski L, Slee A, et al. Modafinil for the treatment of cocaine dependence. Drug and alcohol Dependence Elsevier. 2009;104:133–139. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2009.04.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Haney M, Rubin E, Denson RK, Foltin RW. Modafinil reduces smoked cocaine self-administration in humans: effects vary as a function of cocaine ‘priming’ and cost. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2021;221:108554. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2021.108554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Kampman KM, Lynch KG, Pettinati HM, Spratt K, Wierzbicki MR, Dackis C, et al. A double blind, placebo controlled trial of modafinil for the treatment of cocaine dependence without co-morbid alcohol dependence. Drug and alcohol Dependence Elsevier. 2015;155:105–110. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2015.08.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Schmitz JM, Green CE, Stotts AL, Lindsay JA, Rathnayaka NS, Grabowski J, et al. A two-phased screening paradigm for evaluating candidate medications for cocaine cessation or relapse prevention: modafinil, levodopa–carbidopa, naltrexone. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2014;136:100–107. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2013.12.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Sangroula D, Motiwala F, Wagle B, Shah VC, Hagi K, Lippmann S. Modafinil treatment of cocaine dependence: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Substance Use & Misuse. Taylor & Francis. 2017;52:1292–306. doi: 10.1080/10826084.2016.1276597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Mooney ME, Herin DV, Specker S, Babb D, Levin FR, Grabowski J. Pilot study of the effects of lisdexamfetamine on cocaine use: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Drug Alcohol Dependence Elsevier. 2015;153:94–103. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2015.05.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Nuijten M, Blanken P, van de Wetering B, Nuijen B, van den Brink W, Hendriks VM. Sustained-release dexamfetamine in the treatment of chronic cocaine-dependent patients on heroin-assisted treatment: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. The Lancet. 2016;387:2226–2234. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)00205-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Chan B, Freeman M, Ayers C, Korthuis PT, Paynter R, Kondo K, et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis of medications for stimulant use disorders in patients with co-occurring opioid use disorders. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2020;216:108193. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2020.108193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Levin FR, Bisaga A, Raby W, Aharonovich E, Rubin E, Mariani J, et al. Effects of major depressive disorder and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder on the outcome of treatment for cocaine dependence. J Subst Abus Treat Oxford Pergamon-Elsevier Science Ltd. 2008;34:80–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2006.11.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Levin FR, Evans SM, Brooks DJ, Garawi F. Treatment of cocaine dependent treatment seekers with adult ADHD: double-blind comparison of methylphenidate and placebo. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2007;87:20–29. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2006.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Levin FR, Mariani JJ, Specker S, Mooney M, Mahony A, Brooks DJ, et al. Extended-release mixed amphetamine salts vs placebo for comorbid adult attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and cocaine use disorder: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry Am Med Assoc. 2015;72:593–602. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2015.41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Dakwar E, Levin F, Foltin RW, Nunes EV, Hart CL. The effects of subanesthetic ketamine infusions on motivation to quit and cue-induced craving in cocaine-dependent research volunteers. Biol Psychiatry Elsevier. 2014;76:40–46. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2013.08.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Dakwar E, Nunes EV, Hart CL, Foltin RW, Mathew SJ, Carpenter KM, et al. A single ketamine infusion combined with mindfulness-based behavioral modification to treat cocaine dependence: a randomized clinical trial. AJP Am Psychiatric Publishing. 2019;176:923–930. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2019.18101123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Dakwar E, Nunes EV, Hart CL, Hu MC, Foltin RW, Levin FR. A sub-set of psychoactive effects may be critical to the behavioral impact of ketamine on cocaine use disorder: results from a randomized, controlled laboratory study. Neuropharmacology. 2018;142:270–276. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2018.01.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Chan B, Kondo K, Freeman M, Ayers C, Montgomery J, Kansagara D. Pharmacotherapy for cocaine use disorder—a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Gen Intern Med. 2019;34:2858–2873. doi: 10.1007/s11606-019-05074-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Krupitsky E, Burakov A, Romanova T, Dunaevsky I, Strassman R, Grinenko A. Ketamine psychotherapy for heroin addiction: immediate effects and two-year follow-up. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2002;23:273–283. doi: 10.1016/S0740-5472(02)00275-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Krupitsky EM, Burakov AM, Dunaevsky IV, Romanova TN, Slavina TY, Grinenko AY. Single versus repeated sessions of ketamine-assisted psychotherapy for people with heroin dependence. J Psychoactive Drugs. 2007;39:13–19. doi: 10.1080/02791072.2007.10399860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Bouida W, Bel Haj Ali K, Ben Soltane H, Msolli MA, Boubaker H, Sekma A, et al. Effect on opioids requirement of early administration of intranasal ketamine for acute traumatic pain. Clin J Pain. 2020;36:458–62. doi: 10.1097/AJP.0000000000000821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Nielsen RV, Fomsgaard JS, Nikolajsen L, Dahl JB, Mathiesen O. Intraoperative S-ketamine for the reduction of opioid consumption and pain one year after spine surgery: a randomized clinical trial of opioid-dependent patients. Eur J Pain. 2019;23:455–460. doi: 10.1002/ejp.1317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Boenigk K, Echevarria GC, Nisimov E, von Bergen Granell AE, Cuff GE, Wang J, et al. Low-dose ketamine infusion reduces postoperative hydromorphone requirements in opioid-tolerant patients following spinal fusion: a randomised controlled trial. Eur J Anaesthesiol EJA. 2019;36:8–15. doi: 10.1097/EJA.0000000000000877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Nielsen RV, Fomsgaard JS, Siegel H, Martusevicius R, Nikolajsen L, Dahl JB, et al. Intraoperative ketamine reduces immediate postoperative opioid consumption after spinal fusion surgery in chronic pain patients with opioid dependency: a randomized, blinded trial. Pain. 2017;158:463–470. doi: 10.1097/j.pain.0000000000000782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Pisano VD, Putnam NP, Kramer HM, Franciotti KJ, Halpern JH, Holden SC. The association of psychedelic use and opioid use disorders among illicit users in the United States. J Psychopharmacol SAGE Publications Ltd STM. 2017;31:606–613. doi: 10.1177/0269881117691453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Garcia-Romeu A, Davis AK, Erowid E, Erowid F, Griffiths RR, Johnson MW. Persisting reductions in cannabis, opioid, and stimulant misuse after naturalistic psychedelic use: an online survey. Front Psychiatry. 2020;10:955. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2019.00955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Argento E, Braschel M, Walsh Z, Socias ME, Shannon K. The moderating effect of psychedelics on the prospective relationship between prescription opioid use and suicide risk among marginalized women. J Psychopharmacol SAGE Publications Ltd STM. 2018;32:1385–1391. doi: 10.1177/0269881118798610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Brown T. Ibogaine In The treatment of substance dependence. Current drug abuse reviews. 2013;6. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 112.Brown TK, Alper K. Treatment of opioid use disorder with ibogaine: detoxification and drug use outcomes. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse Taylor Francis. 2018;44:24–36. doi: 10.1080/00952990.2017.1320802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.D’Souza DC, Radhakrishnan R, Naganawa M, Ganesh S, Nabulsi N, Najafzadeh S, et al. Preliminary in vivo evidence of lower hippocampal synaptic density in cannabis use disorder. Mol Psychiatry. 2021;26:3192–3200. doi: 10.1038/s41380-020-00891-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Angarita GA, Worhunsky PD, Naganawa M, Toyonaga T, Nabulsi NB, Li C-SR, et al. Lower prefrontal cortical synaptic vesicle binding in cocaine use disorder: an exploratory 11 C-UCB-J positron emission tomography study in humans. Addict Biol. 2022;27:e13123. doi: 10.1111/adb.13123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.