Abstract

China has become one of the leading study abroad destinations worldwide. Recent research also indicates that international students encounter diverse life challenges and mental health issues in China. Therefore, scholars have shown increasing interest in their adjustment in Chinese social and academic settings. Seeking theoretical guidance from the Job Demands-Resources Model with mediation and moderation assumptions, our study aimed to test the dual processes (i.e., the health impairment process and the motivational process) leading to academic, sociocultural, and psychological adjustment, among international students sojourning in China. Using a convenience sampling method, our study recruited 1,001 participants (535 males and 466 females; Mage = 22.73; SD = 1.62) who completed an online survey including scales of perceived cultural distance (contextual demands), social support from local members (contextual resources), coping self-efficacy (personal resources), acculturative stress, intercultural engagement, as well as three types of cross-cultural adjustment (academic, sociocultural, and psychological adjustment). Results based on the structural equation modeling (SEM) analyses indicated that perceived cultural distance had indirect relationships with the three types of adjustment through the mediator of acculturative stress. Social support from locals had indirect relationships with the three types of adjustment through the mediators of acculturative stress and intercultural engagement. Coping self-efficacy had indirect relationships with academic and sociocultural adjustment through the mediator of intercultural engagement. Additionally, social support from locals was revealed as a moderator that buffered the relationship between perceived cultural distance and acculturative stress. These mediated and moderated relationships not only confirmed the dual processes underlying international student adjustment, but also added new knowledge of how demands and resources can interplay to predict the dual processes.

Keywords: International student, China, Health impairment, Motivation, Cross-cultural adjustment

Introduction

China has become the third top destination for international students worldwide, behind the U.S. and UK (Cao & Meng, 2022). Scholars begin to show interest in international students’ cross-cultural experiences in Chinese social and academic contexts. Some studies explored this promising topic and revealed that this cohort suffered from diverse acculturative stressors that can undermine their quality of life, such as stressful emotions, social and academic disintegration, and health-related issues (e.g., Cao et al., 2020; Ding, 2016; English et al., 2022, 2015; Wen et al., 2018; Yang et al., 2018). Since these revealed daunting transitional challenges stem from social, academic, and psychological domains, such empirical evidence clearly informs that there is a need of more comprehensive investigations of what factors can help this cohort achieve optimal cross-cultural adjustment (Ward et al., 2001).

From the theoretical perspective, there are also three types of cross-cultural adjustment. For minority groups in general, Ward and colleagues distinguished sociocultural and psychological adjustment (e.g., Ward & Kennedy, 1999; Ward et al., 2004). Sociocultural adjustment denotes “the ability to ‘fit in’, to acquire culturally appropriate skills, and to negotiate interactive aspects of the host environment”, whereas psychological adjustment denotes psychological well-being or satisfaction but is often measured by various symptoms of psychological depression in the host environment (e.g., sadness, loneliness, and frustration) (Ward & Kennedy, 1999). Meanwhile, international students can be a special minority group facing unfamiliar academic environment and striving additionally for academic goals. Therefore, researchers have more recently argued that for international students, academic adjustment should be examined as an extra type of adjustment (Rienties et al., 2012). Academic adjustment refers to the extent to which international students can acclimate to various academic demands of host universities, such as instructional methods, teaching approaches, classroom interactions, and management styles (Gong & Fan, 2006).

Although the three types of adjustment are all important markers of international students’ performance and success in the host contexts, rather few studies simultaneously investigate them within a single research design (Cao et al., 2022). Therefore, our study intends to move beyond previous studies and obtain a more integrative understanding of international students’ performance by simultaneously considering all three types of adjustment. To achieve the objective, our study incorporates an inter-disciplinary perspective and seeks theoretical guidance from the Job Demands-Resources Model (JD-R; Bakker & Demerouti, 2017; Schaufeli & Taris, 2014). The theory articulates two underlying processes that can lead to personal performance. Specifically, one process is the health impairment process (i.e., the negative process) and the other process is the motivational process (i.e., the positive process). Guided by JD-R, we can examine positive and negative predictors of international students’ academic, sociocultural, and psychological adjustment, thus providing novel interpretations of how the dual processes can be related to cross-cultural adjustment.

Theoretical framework

JD-R is originally focused on occupational well-being and has three key propositions. The first proposition is that there are two types of job characteristics and one type of personal characteristics that can influence personal and/or organizational performance: job demands (i.e., aspects of the job that involve physio-psychological costs due to demands for sustained efforts, such as job insecurity and excessive workload), job resources (i.e., aspects of the job that facilitate achieving work goals and stimulating personal growth, such as social support and training programs), as well as personal resources (i.e., personal beliefs concerning the extent to which the environment is under control, such as self-efficacy and optimism) (Bakker & Demerouti, 2017). According to the theory, job demands may be negative predictors of health/performance, while job and personal resources may function similarly as positive predictors of health/performance (Bakker & Demerouti, 2017).

The second proposition of JD-R is that the demands and resources instigate two different processes with mediation perspectives. One is the health impairment process wherein work stress (or burnout) mediates the relationships of the demands and resources to health/performance (Mudrak et al., 2018; Schaufeli & Taris, 2014). The other is the motivational process wherein engagement (or motivation) mediates relationships of job/personal resources to health/performance (Schaufeli & Taris, 2014). Also noteworthy is that the relationship between job demands and work motivation (or engagement) is not assumed in JD-R because this relationship may largely result from personal characteristics of employees and organizational characteristics of the job (Schaufeli & Taris, 2014).

The third proposition of JD-R concerns moderation perspectives: job/personal resources may buffer the impact of job demands on stress or burnout, whereas job demands may boost the impact of job/personal resources on engagement (Bakker & Demerouti, 2017). Adequate empirical evidence has been offered for the moderation perspectives in JD-R by showing that employees experiencing job demands may not suffer from high levels of stress or exhaustion when they have access to sufficient resources (e.g., Dicke et al., 2018; Xanthopoulou et al., 2007), and that employees possessing sufficient resources may be highly motivated or engaged in work, particularly when they encounter high demands (e.g., Cao et al., 2020; Dicke et al., 2018).

Why can JD-R guide research on cross-cultural adjustment?

Despite JD-R originally emphasizing work contexts, a few studies have recently extended the theory to researching academic performance of students samples with specific academic demands and/or resources (Lee et al., 2020; Wilson & Sheetz, 2010). Specifically, Lee et al. (2020) utilized JD-R and distinguished Korean high school students’ academic burnout profiles into four clusters (distressed, Laissez-Faire, struggling, and well-functioning groups) according to academic motivation. Wilson and Sheetz (2010) also employed this theory and revealed that IT students’ group task demands and resources predicted group academic success through the mediator of academic pressure. Moving further beyond, Cao and Meng’s (2022) review article utilized the theory to categorize predictors of international student adjustment into four clusters (i.e., contextual resources, contextual demands, personal resources, and personal demands) and recommended that future research apply this theory to gain new insights into sojourners’ performance.

Similar to employees with demands and resources from the working contexts, international students sojourning in host academic and sociocultural contexts inevitably suffer from various contextual demands (for example: cultural distance, discrimination, and academic workload), and benefit from various contextual resources (for example: social support, receptive host contexts, and intercultural training) and personal resources (for example: self-efficacy and proactive personality). Therefore, following the first proposition of JD-R, we assume that contextual demands may be negative predictors of cross-cultural adjustment, while contextual resources may be positive predictors of cross-cultural performance. The underlying mechanism is that excessive contextual demands stemming from host environments tend to give rise to challenges and hassles that require international students to make sustained efforts and undermine their adjustment, while adequate contextual resources from host environments and personal resources from the selves tend to facilitate international students’ development in affective, behavioral, and cognitive domains that may bolster their adjustment. Hence, guided by JD-R, we aim to empirically test international student adjustment by selecting the predictors: perceived cultural distance as contextual demands, social support from locals as contextual resources, and coping self-efficacy as personal resources. Although JD-R emphasizes that any demand and any resource can be included as predictors (Bakker & Demerouti, 2017; Schaufeli & Taris, 2014), the definitions and importance of these selected predictors will be discussed in the subsequent sections.

Following the second proposition of JD-R, we assume that international students’ contextual demands and contextual/personal resources may also activate the dual processes (the health impairment process and the motivational process) with acculturative stress and intercultural engagement acting as mediators. Acculturative stress is conceptualized as stressful responses occurring while adapting to host cultures (Taušová et al., 2019). Intercultural engagement is conceptualized as international students’ engagement in Chinese social gatherings or events. In details, excessive contextual demands (i.e., cultural distance) may consume much time and energy and thus may be turned into stressful emotions. However, contextual (i.e., support from locals) and personal resources (i.e., coping self-efficacy) may help achieve goals, recover from stressful emotions, enhance social skills, as well as reinforce self-regulated motivation for intercultural activities (Cao & Meng, 2022). In turn, acculturative stress may negatively predict adjustment resulting from the aroused anxiety and withdrawal intentions (Bae, 2020), while intercultural engagement may positively predict adjustment due to the acquisition of culture-specific skills (Cao & Meng, 2020; Kim, 2001). Finally, following the third proposition of JD-R, our final purpose is to investigate the interaction effects between contextual demands and contextual/personal resources on acculturative stress and intercultural engagement, respectively.

Applying JD-R to the cross-cultural adjustment literature brings several novel perspectives. First, JD-R emphasizes that any demand and any resource can be incorporated as predictors (Bakker & Demerouti, 2017; Schaufeli & Taris, 2014), and thus may offer a broad scope and flexibility in exploring antecedents of cross-cultural adjustment. Second, guided by JD-R, we can investigate both negative (the health impairment process) and positive (the motivational process) pathways, thus yielding a comprehensive interpretation of adjustment. Finally, JD-R assumes interactive effects between the demands and resources, which may unpack unique functioning mechanisms.

Perceived cultural distance, social support and coping self-efficacy as predictors

Cultural distance means discrepancy between cultures in terms of norms, values, traditions and religion (Chen et al., 2010). In this study, perceived cultural distance, instead of national scores of cultural dimensions, is measured because the former manifests individual differences. When international students relocate in the unfamiliar host environment, they experience collisions between heritage and host cultures. As a contextual challenge, cultural distance is a major source of other acculturative stressors since international students without host culture knowledge have no clue of what behaviors are appropriate, where social support is available, and how their purposes can be fulfilled. Sticking to JD-R, we examine its relationships with adjustment and acculturative stress. Cao et al. (2016) surveyed Chinese international students and found that cultural distance was associated with sociocultural and academic adjustment difficulties. International students perceiving the two cultures in contact as highly different feel more depressed both mentally and psychologically. Supporting this argument, Taušová et al. (2019) found that cultural distance was directly related to acculturative stress, and indirectly related to mental health problems via acculturative stress.

We examine a specific source of social support (perceived levels of support from Chinese locals) as contextual resources since host supportive environments tend to be central to minority members’ health, emotions, and behaviors. According to JD-R, support from locals may have relationships with acculturative stress, intercultural engagement and cross-cultural adjustment. Regarding the social support‒acculturative stress relationship, studies evidenced the protective roles of social support in reducing acculturative stress among international students in Cyprus (Ladum & Burkholder, 2019). Regarding the social support‒social engagement relationship, Rochelle and Shardlow (2014) revealed that social support can increase social participation among UK Chinese. In a more recent study, Lai et al. (2019) targeted immigrants in the U.S. and found community support positively predicted their engagement in both cognitive and social activities. Regarding the support‒adjustment relationship, studies revealed that international students with wide access to social support tended to be better adapted both academically (Cao et al., 2021; Cura & Işık, 2016) and psychologically (Bender et al., 2019).

As personal resources, coping self-efficacy means individuals’ confidence in their capacities to cope effectively with threats and challenges and has three dimensions: using problem-focused coping, stopping unpleasant thoughts, and getting support from friends and family (Chesney et al., 2006). This construct has been applied to various social groups suffering from stressful events, such as marginalized youths (Melato et al., 2017). Surprisingly, it is scarcely applied to international students who also face many stressful challenges (see two exceptions: Elemo & Türküm, 2019; Smith & Khawaja, 2014). The two studies showed that coping self-efficacy can be promoted through psycho-educational interventions designed for international students, but they did not provide empirical evidence for the predictive roles of coping self-efficacy.

In this vein, we rely on prior research targeting other social groups to support our assumed relationships of coping self-efficacy with acculturative stress, intercultural engagement and adjustment. As argued by Rodebaugh (2006), self-efficacious individuals tend to be high in persistence in a specific task or activity. It may hold true for international students because those who are low in coping self-efficacy tend to lack confidence in dealing with stressful and unpredictable breakdowns in communicating with outgroup members, and consequently lead to intergroup avoidance and withdrawal intentions (Rast et al., 2018). In addition, coping self-efficacy was revealed to alleviate perceived stress of patients (Chesney et al., 2006) and academic stress of university undergraduates (Watson & Watson, 2016), and enhance psychosocial well-being of marginalized youths (Melato et al., 2017).

Acculturative stress and intercultural engagement as mediators

JD-R offers insights into pathways to cross-cultural adjustment with acculturative stress and intercultural engagement as mediators. Regarding mediations of acculturative stress, we can also find theoretical support from the acculturation process model (Ward et al., 2001) positing that acculturation is a dynamic process wherein acculturative stress occupies a linking place, created by life challenges and exerting influence on adjustment. Empirically, Taušová et al. (2019) established acculturative stress as a mediator between cultural distance and psychological adjustment (i.e., mental health and satisfaction) among international students. Furthermore, Bae (2020) revealed acculturative stress as a mediator between social capital (sources of social support) and depression symptoms among multicultural adolescents.

According to Kim’s integrative theory of cross-cultural adaptation (Kim, 2001), minority members’ engagement in the host society can facilitate achieving adjustment through acquired insights and culture-specific skills. As discussed previously, social support and coping self-efficacy may activate international students’ willingness for engagement in Chinese social gatherings. In turn, actively engaged individuals may be more familiar with Chinese cultural norms and traditions, as well as Chinese locals’ values and behavioral features, thus achieving better functional fitness and adjustment. However, a thorough literature review informs that such theoretically grounded mediation paths are scarcely examined among minority members. Most relevant to our objectives can be the study by Oppedal and Idsoe (2015) who found that host cultural competence (measured mainly by competence for engagement in the host society) mediated the relationship between support from Norwegian friends and depressive symptoms among refugees in Norway. Besides, relevant mediations were also evidenced among student cohorts. For example, social support was indirectly related to school satisfaction via school engagement (Gutiérrez et al., 2017). For the coping self-efficacy‒adjustment relationship mediated by engagement, we can find support in academic settings. For students, the relationship between self-efficacy and achievement was mediated by academic engagement (Ucar & Sungur, 2017); for teachers, the relationship between self-efficacy and job satisfaction was mediated by work engagement (Li et al., 2017).

Interactions among cultural distance, social support and coping self-efficacy

Our final purpose is to test the moderation perspectives in JD-R. Specifically, job/personal resources may act as moderators, buffering the negative impact of job demands on job stress or burnout; job demands may act as moderators, boosting the positive impact of job/personal resources on work engagement (Bakker & Demerouti, 2017).

Accordingly, it is first expected that both support from locals and coping self-efficacy can buffer the relationship between cultural distance and acculturative stress. Empirically, the positive relationship between discrimination (contextual demand) and poor health symptoms disappeared at high social support among Mexican-Americans (Finch & Vega, 2003). Similar moderations were also evidenced for coping-related variables. Asian Indians’ active coping buffered effects of discrimination on anxiety (Nadimpalli et al., 2016). Such protective roles of coping were found in other social groups at risks. Boulton (2013) focused on college students with childhood bullying victimization and found that problem-focused coping lessened the adverse effects of verbal and physical victimization and social exclusion on social anxiety.

It is also expected that cultural distance may interact with social support and coping self-efficacy to predict intercultural engagement. The underlying reason is that accessible resources may be particularly salient and useful in stimulating motivation or engagement when there are high demands (Bakker & Demerouti, 2017). In his conservation of resources theory (COR), Hobfoll (2001) also notes that all resources are motivational in nature and individuals may depend more on the motivating forces when encountering stressors or challenges. Hence, there are reasons to assume that international students may benefit more from their coping self-efficacy and social support when cultural distance is high rather than low. However, the supportive evidence is hardly available except for Hua et al. (2019) who found that the positive relationship between proactive personality (personal resources) and social integration was shown only at high levels of cultural distance. Despite the scarce evidence, the two moderation perspectives are worth investigating because they are theoretically driven.

The current study

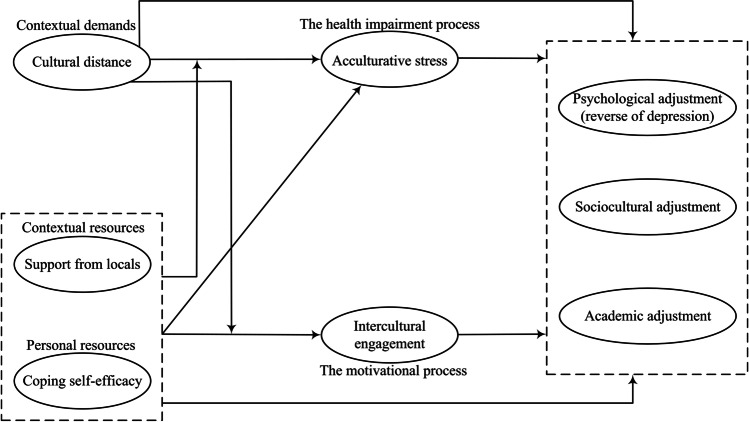

Guided by JD-R, we propose a conceptual model of cross-cultural adjustment (see Fig. 1), including both mediation and moderation perspectives. As shown in the figure, it is assumed that perceived cultural distance (contextual demands) may have indirect relationships with the three types of cross-cultural adjustment via the mediator of acculturative stress. Both social support from locals (contextual resources) and coping self-efficacy (personal resources) may have indirect relationships with the three types of cross-cultural adjustment via the mediators of acculturative stress and intercultural engagement. Additionally, cultural distance may interact with social support from locals and coping self-efficacy in predicting acculturative stress and intercultural engagement. Accordingly, the following research hypotheses are proposed.

Fig. 1.

The conceptual research model

Regarding mediation effects:

H1: Acculturative stress will be a mediator between cultural distance and psychological (H1a), sociocultural (H1b), and academic (H1c) adjustment.

H2: Acculturative stress and intercultural engagement will be mediators between social support and psychological (H2a), sociocultural (H2b), and academic (H2c) adjustment.

H3: Acculturative stress and intercultural engagement will be mediators between coping self-efficacy and psychological (H3a), sociocultural (H3b), and academic (H3c) adjustment.

Regarding moderation effects:

H4: Cultural distance will be positively associated with acculturative stress when social support (H4a) or coping self-efficacy (H4b) is low, but this relationship will be weaker or disappear when social support or coping self-efficacy is high.

H5: Social support (H5a) and coping self-efficacy (H5b) will be positively associated with intercultural engagement when cultural distance is high, but the two relationships will be weaker or disappear when cultural distance is low.

Methods

In this section, we mainly introduced data collection procedures, background information of the participants, instruments used to measure the constructs, and major data analysis strategies for examining the relationships among the constructs.

Data collection procedures

Conducting the study was approved by the ethnics committee of the university where the first author is working. All procedures performed in this study involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee, as well as with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

All participants were international students currently sojourning in mainland China. The authors utilized two large-scale online communities in China where international students can interact and discuss with each other. Using the convenience sampling method, the authors attempted to identify international students in China via the online communities. Once a potential participant was identified, online messages were sent individually to inform them of research objectives, voluntariness and anonymity of participation, as well as selection criteria. The criteria mandated that all participants must be full-time international students currently sojourning in Mainland China. If they met the selection criteria and agreed to participate, the link to the online English survey was sent to them. Prior to filling in the online survey, all participants returned the informed consent forms. The data collection began in May of 2020 and lasted nearly two months till the end of July.

Participants

Altogether 1,001 international students returned the informed consents for participation and completed the online survey. The participants (N = 1,001) were from 19 countries, mainly Japan (N = 167), Russia (N = 93), Canada (N = 93), France (N = 83), and South Korea (N = 76). Most of them were from Asia (N = 591), followed by Europe (N = 231), and North America (N = 179). They studied at various universities mainly located in large Chinese cities, such as Beijing (N = 278), Shanghai (N = 266) and Guangzhou (N = 123). There were 535 males and 466 females, with age ranging from 18 to 25 years old (M = 22.73; SD = 1.62), and with length of stay in China ranging from 6 to 39 months (M = 19.29; SD = 8.83).

Measures

The whole questionnaire was administered in English since proficiency in English is a basic requirement for international students applying to study in China. The measures included in the questionnaire were as follows:

Cultural distance. The six-item scale from Chen et al. (2010) was used to measure perceived cultural distance pertaining to beliefs, values, norms, customs and religions (item example: To what extent are life and customs of China different from those of your home country?). Response categories ranged from 1 = not at all different to 5 = highly different (α = 0.96).

Social support from locals. Six items were adapted from the short-form Social Support Questionnaire (Sarason et al., 1987). An example was “You can really count on Chinese friends to distract you from worries when you feel under stress”. Response categories ranged from 1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree (α = 0.91).

Coping self-efficacy. We utilized Chesney et al.’s (2006) short-form coping self-efficacy scale which asked a general question: “When things aren’t going well for you, or when you’re having problems, how confident or certain are you that you can do the following?”. The scale has three dimensions: using problem-focused coping (six items; example: Break an upsetting problem down into smaller parts), stopping unpleasant thoughts (four items; example: Take your mind off unpleasant thoughts), and getting support from friends and family (three items; example: Get emotional support from friends and family). Response categories of all items ranged from 1 = not at all to 5 = very strongly (problem-focused coping: α = 0.91; stopping unpleasant thoughts: α = 0.90; getting support: α = 0.78).

Acculturative stress. We utilized Benet-Martinez and Haritatos’ (2005) scale to measure levels of acculturative stress stemming from four dimensions: language skills (three items; example: You often feel misunderstood or limited in daily situations because of linguistic barriers), intercultural relations (three items; example: You have had disagreements with co-ethnic members for liking Chinese ways of doing things), cultural isolation (three items; example: Your living environment is not multicultural enough), and academic work (three items: example: You have to study much harder because of your particular ethnic/cultural status). Response categories ranged from 1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree (language skills: α = 0.92; intercultural relations: α = 0.92; cultural isolation: α = 0.91; academic work: α = 0.88).

Intercultural engagement. The six-item scale (Kim et al., 2016) was used to assess how frequently international students engaged in Chinese social gatherings or events (item example: How often do you attend Chinese social events?). Response categories ranged from 1 = not at all to 5 = very often (α = 0.90).

Cross-cultural adjustment. Our study used measures of cross-cultural adjustment designed specifically for international students. Gong and Fan’s (2006) international student adjustment scales were used to measure academic adjustment (five items; example: To what extent are you adjusted to academic requirements at the host university?) and sociocultural adjustment (five items; example: To what extent are you adjusted to being associated with Chinese locals?). Response categories ranged from 1 = not at all to 5 = extremely well. Psychological adjustment was measured by eight items (example: You feel sad to be away from your home country) (Demes & Geeraert, 2014). Response categories ranged from 1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree. Since the eight items tapped different psychological depressive symptoms, we recoded them for consistency with academic and sociocultural adjustment (psychological adjustment: α = 0.97; sociocultural adjustment: α = 0.90; academic adjustment: α = 0.89).

Statistical analyses

Main analyses are conducted with structural equation modeling (SEM) in AMOS 22.0. The model-data fit is assessed with these indices: χ2/df ratio (< 3), TLI (> 0.90), CFI (> 0.95), SRMR (< 0.08) and RMSEA (< 0.08) (Hu & Bentler, 1999). Additionally, mediation effects are tested using the bootstrap method in SEM. Moderation effects are probed using simple slope analyses.

Results

Preliminary analyses

Table 1 presents means, standard deviations, correlations of the focal variables and the demographics (gender, age, length of residence in China, and continents of origin). The results showed that age negatively correlated with the mediator of acculturative stress and the outcome of psychological adjustment. Length of residence positively correlated with the outcomes of sociocultural and academic adjustment. Thus, they were included in the model for analyses.

Table 1.

Means, standard deviations, and correlations of the focal and demographic variables

| Variable | M | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Cultural distance | 3.16 | 1.10 | — | |||||||||||

| 2. Support from locals | 3.97 | 0.68 | 0.08* | — | ||||||||||

| 3. Coping self-efficacy | 3.72 | 0.71 | 0.21** | 0.65** | — | |||||||||

| 4. Acculturative stress | 2.70 | 0.97 | 0.18** | − 0.12** | − 0.08* | — | ||||||||

| 5. Intercultural engagement | 3.61 | 0.69 | 0.26** | 0.56** | 0.64** | − 0.03 | — | |||||||

| 6. Academic adjustment | 3.75 | 0.72 | 0.18** | 0.62** | 0.72** | − 0.11** | 0.74** | — | ||||||

| 7. Sociocultural adjustment | 3.75 | 0.76 | 0.13** | 0.63** | 0.71** | − 0.13** | 0.75** | 0.85** | — | |||||

| 8. Psychological adjustment | 3.43 | 0.99 | − 0.14** | 0.14** | 0.06 | − 0.67** | 0.04 | 0.10** | 0.12** | — | ||||

| 9. Gender | 1.47 | 0.50 | − 0.02 | 0.00 | − 0.03 | − 0.01 | 0.03 | − 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.01 | — | |||

| 10. Age | 22.73 | 1.62 | − 0.06* | − 0.02 | − 0.05 | 0.11** | − 0.03 | − 0.01 | − 0.03 | − 0.11** | 0.01 | — | ||

| 11. Length of residence | 19.29 | 8.83 | − 0.10** | 0.05 | 0.07* | − 0.05 | 0.05 | 0.09** | 0.09** | 0.01 | − 0.02 | 0.17** | — | |

| 12. Continents of origins | 1.59 | 0.77 | 0.05 | − 0.04 | − 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.01 | − 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.03 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.06* | — |

Note. * p < .05; ** p < .01

Testing the measurement model and the common method bias

Among the eight latent variables in the measurement model, acculturative stress and coping self-efficacy were represented by their respective sub-scales, while others were represented by their individual items. The results yielded a good model-data fit: χ2 (831, N = 1001) = 2348.31, p < .001, χ2/df = 2.83, SRMR = 0.03, RMSEA = 0.04, CFI = 0.96 and TLI = 0.96, with factor loadings ranging from 0.73 to 0.93. Additionally, composite reliability (CR) values exceeded the criterion of 0.60, demonstrating good reliability. Average variance extracted (AVE) exceeded the criterion of 0.50, demonstrating good convergent validity. We computed square roots of the AVE, and the value for each scale exceeded its correlation coefficients with other scales, demonstrating good discriminant validity. These results are reported in Table 2.

Table 2.

CR, AVE and square roots of AVE for the variables in the measurement model

| Value | Cultural distance | Support from locals | Coping self-efficacy | Acculturative stress | Intercultural engagement | Academic adjustment | Sociocultural adjustment | Psychological adjustment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CR | 0.96 | 0.91 | 0.93 | 0.95 | 0.90 | 0.89 | 0.90 | 0.97 |

| AVE | 0.79 | 0.64 | 0.80 | 0.82 | 0.60 | 0.62 | 0.64 | 0.78 |

| Square roots of AVE | 0.89 | 0.80 | 0.89 | 0.91 | 0.77 | 0.79 | 0.80 | 0.88 |

Podsakoff et al. (2003) recommend that studies using self-reported measures conduct Harman’s single factor test to check the common method bias. Accordingly, we forced all 61 items to load on a single unrotated factor, which extracted 30.08% of the total variance, far below the warning cut-off criterion of 50%. Besides, a single-factor was assessed, which received a rather poor model fit: χ2 (1769, N = 1001) = 37340.58, p < .001, χ2/df = 21.11, SRMR = 0.23, RMSEA = 0.14, CFI = 0.37 and TLI = 0.35. The combined analyses indicated that the common method bias cannot be a problem for the present study.

Testing the structural model

The structural model additionally contained the two latent interaction terms (cultural distance × support from locals and cultural distance × coping self-efficacy) and the demographics of age and length of residence. For constructing the latent interactions, we employed the matched-pair strategy as recommended by Marsh et al. (2004), which has been demonstrated to outperform other construction strategies in assessing interacting effects.

The structural model (see Fig. 2) fitted the data satisfactorily: χ2 (1083, N = 1001) = 3062.24, p < .001, χ2/df = 2.59, SRMR = 0.03, RMSEA = 0.04, CFI = 0.96 and TLI = 0.96. Standardized path coefficients revealed that cultural distance positively predicted acculturative stress (β = 0.22, p < .001) and negatively predicted sociocultural adjustment (β = -0.07, p = .001), but had no direct relationships with psychological (β = 0.01, p = .775) and academic (β = -0.01, p = .533) adjustment. Support from locals negatively predicted acculturative stress (β = -0.18, p = .001), and positively predicted intercultural engagement (β = 0.22, p < .001), psychological (β = 0.07, p = .034), sociocultural (β = 0.11, p < .001) and academic (β = 0.11, p < .001) adjustment. Coping self-efficacy positively predicted intercultural engagement (β = 0.55, p < .001), sociocultural (β = 0.32, p < .001) and academic (β = 0.37, p < .001) adjustment, but was non-significant for acculturative stress (β = 0.01, p = .861) and psychological adjustment (β = -0.07, p = .101). Additionally, acculturative stress negatively predicted psychological (β = -0.60, p < .001), sociocultural (β = 0.07, p < .001) and academic (β = -0.06, p = .006) adjustment. Intercultural engagement positively predicted sociocultural (β = 0.55, p < .001) and academic (β = 0.50, p < .001) adjustment, but was non-significant for psychological adjustment (β = 0.01, p = .723). The interaction between cultural distance and support from locals predicted acculturative stress (β = -0.19, p = .003), but all other interactions were non-significant. As for the demographics of age and length of stay in China, the only significance was found between age and acculturative stress (β = 0.12, p < .001), but these coefficient paths were not shown in the model for its parsimony.

Fig. 2.

Results of testing the structural model. * p < .05, ** p < .01, *** p < .001; The demographics of age and length of stay in China are not shown for parsimony of the model; Covariances between the exogenous and those between the endogenous variables are not shown for parsimony of the model; The solid lines indicate the significant standardized coefficient paths; The dotted lines indicate non-significant standardized coefficient paths

Testing mediation and moderation effects

Mediation was assessed with the bootstrapping method in SEM. Mediation can be confirmed if 95% confidence intervals (CI) do not contain zero (Shrout & Bolger, 2002). Results showed that cultural distance had indirect relationships with psychological [95% CI (-0.239, -0.114)], sociocultural [95% CI (-0.025, -0.007)] and academic [95% CI (-0.023, -0.005)] adjustment via acculturative stress. Thus, H1 received support. Support from locals was indirectly related to psychological [95% CI (0.036, 0.249)], sociocultural [95% CI (0.059, 0.218)], and academic [95% CI (0.054, 0.200)] adjustment via acculturative stress and intercultural engagement. Thus, H2 received support. Coping self-efficacy had indirect relationships with sociocultural [95% CI (0.225, 0.394)] and academic [95% CI (0.206, 0.365)] adjustment, but not with psychological adjustment [95% CI (-0.114, 0.095)]. Intercultural engagement mediated these two relationships since coping self-efficacy did not predict acculturative stress, which violated the precondition of a mediation process. Thus, only H3b and H3c received partial support.

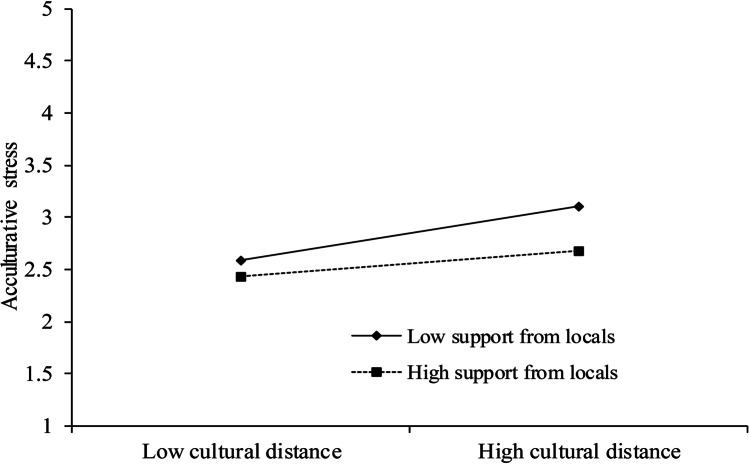

Support from locals moderated the relationship between cultural distance and acculturative stress. To further probe this moderation, we conducted a simple slope analysis (Aiken & West, 1991) to test effects of cultural distance on acculturative stress at low (one SD below the mean) and high (one SD above the mean) levels of support. The results revealed that the positive relationship between cultural distance and acculturative stress was weaker at high (t = 3.11; p = .002) than at low support (t = 5.50; p < .001) (see Fig. 3). Thus, only H4a received support.

Fig. 3.

Interaction effects between cultural distance and social support on acculturative stress

Discussion and implications

The present study made the initial attempt to empirically test JD-R among international students. Keeping this goal in mind, we purposefully selected perceived cultural distance as contextual demands, social support from locals as contextual resources, and coping self-efficacy as personal resources. The results derived from the SEM analyses indicated that these demands and resources functioned differently in the dual processes. Furthermore, the mediation and moderation perspectives within JD-R were largely confirmed. These findings cannot only shed new lights on cross-cultural adjustment, but can also inspire future research due to the broad scope and flexibility of JD-R.

The roles of perceived cultural distance, social support, and coping self-efficacy

Our results indicated that perceived cultural distance was related with the health impairment process (acculturative stress), while local support and coping self-efficacy was related with the motivational process (intercultural engagement). The stressor of cultural distance is commonly experienced by international students since the initial phase of relocation. High levels of cultural distance represent enormous discrepancies in cultural norms, social traditions, values and behavioral features, thus bringing about misunderstandings, ineffective communication and dissatisfying adjustment (Taušová et al., 2019). For example, international students from low context cultures (cultures where messages are encoded in the explicit language) may have confusion and embarrassment when communicating with Chinese locals featured by high context cultures (cultures where messages are implicitly conveyed via tones, facial expressions and gestures) (Hall, 1976). These conflicts stemming from negotiating with aspects of host cultures can help explain the relationships of cultural distance with acculturative stress and adjustment.

The argument that job and personal resources may function similarly (Bakker & Demerouti, 2017) was largely supported since both local support and coping self-efficacy were directly related to intercultural engagement, and indirectly related to adjustment. Substantial support from host-nationals is suggestive of a receptive and welcoming host environment, which has potentials to evoke minority members’ willingness to be engaged (Rochelle & Shardlow, 2014). Wide access to informational and practical support may better inform international students of when and where traditional activities are available and how to behave in the activities, thus increasing their participating behaviors. The positive relationships of local support with different facets of adjustment were consistent with prior research (Bender et al., 2019; Cura & Işık, 2016). The findings implied that local support seemed important in international students’ overall acculturation process. Given that coping self-efficacy is scarcely examined among international students with various challenges, we expanded the literature by revealing its roles in predicting engagement and adjustment. Individuals high in coping self-efficacy tend to hold strong beliefs in their coping skills necessary for handling challenging contexts (Chesney et al., 2006). Such beliefs can enable the individuals to be actively engaged in activities involving hardships or challenges. Coping self-efficacious international students have strong desires to explore new cultures, and consequently reinforce engaging behaviors (e.g., participating in the host society and building intercultural relationships), thereby facilitating achieving optimal adjustment through active coping, persistence and self-regulation.

Nonetheless, we also found two differences between social support and coping self-efficacy. First, coping self-efficacy did not predict acculturative stress and psychological adjustment. The results were somewhat contrary to prior studies revealing its relationship with academic stress (Watson & Watson, 2016) and psychosocial well-being (Melato et al., 2017). It implied that sole reliance on personal coping skills may be insufficient to attenuate acculturative stress. Plausibly, many international students, particularly those high in coping self-efficacy, may feel emotionally and physically exhausted resulting from their own active and aggressive coping with new and stubborn stressors. Many others, particularly those low in coping self-efficacy, may feel reluctant to cope actively (e.g., learning Chinese language and building relationships with locals), and consequently, acculturative stress and psychological symptoms still remained and bothered them. This may be particularly the case with international students featured by temporary relocation and would return to home countries after completing academic purposes. Second, local support buffered the relationship between cultural distance and acculturative stress. The moderation implied that local support could offer essential contextual resources for sojourners to reduce stress or recover from stress when they encounter challenges. However, the personal resources of coping self-efficacy did not attenuate this relationship. As discussed by Watson andp; Watson (2016), coping self-efficacy can be better interpreted in task- or stressor-specific contexts, whereas cultural distance is a more general stressor manifested in various domains. Hence, it is recommended that future studies examine whether coping self-efficacy can buffer effects of specific contextual demands (e.g., prejudice and academic workload) to enrich the literature.

The roles of acculturative stress and intercultural engagement

As expected, acculturative stress negatively predicted all three types of adjustment. The findings were consistent with previous research (Bae, 2020; Taušová et al., 2019). However, international students’ engagement in Chinese social gatherings positively predicted academic and sociocultural adjustment, but not psychological adjustment. Through social engagements, students can acquire culture-specific skills for interacting with locals and learn norms and traditions of the host society (Kim, 2001), thus contributing to sociocultural adjustment. The acquired knowledge and skills may facilitate acculturating to the on-campus life by effectively interacting with domestic peers, teachers, and administrators and understanding styles and demands of host universities, thus contributing to academic adjustment. However, though actively engaged, many international students in China may still feel homesick for being away from home countries, feel lonely without close friends, and feel frustrated about striving for academic goals, as also revealed by Ding (2016).

Our study unpacked several novel yet important mediational processes with acculturative stress and intercultural engagement as the mediators, which confirmed JD-R (Schaufeli & Taris, 2014). Regarding contextual demands, cultural distance was related with the health impairment process (acculturative stress), which in turn negatively predicted the three types of adjustment. The results stressed the energy-consuming nature of cultural distance, undermining adjustment through gradually draining emotional resources. Regarding personal resources, coping self-efficacy was related with the motivational process (intercultural engagement), which in turn positively predicted academic and sociocultural adjustment. The results suggested instrumental values of coping self-efficacy, functioning as a means to adjustment through engagement. By contrast, social support from locals as contextual resources was related with the dual processes leading to all three types of cross-cultural adjustment.

Taken together, these findings concerning the direct, mediated, and moderated relationships informed that the main propositions of JD-R were suitable for researching international student adjustment. Although a few prior studies have extended the application of JD-R to academic contexts (i.e., Lee et al., 2020; Wilson & Sheetz, 2010). These studies simply considered a part of its propositions. For example, Lee et al. (2020) only tested motivational and burnout factors among Korean high school students, but neglected the mediated and moderated relationships in the JD-R. Wilson and Sheetz (2010) only considered the health impairment process in the JD-R, but neglected the motivational process. Therefore, our study not only contributed to the existing literature by comprehensively testing the propositions of JD-R, but also broadened its application in a new student sample in higher education (i.e., international students).

Counseling implications

Noteworthy is that the revealed relationships were based on a cross-sectional design. Hence, it is not possible to interpret the results as causal effects that can be revealed by longitudinal or experimental studies. However, the associations revealed in our study can also highlight several counselling practices directed by host universities at promoting international students’ adjustment. Our results unveiled several mediational paths to adjustment: the dark side starting from cultural distance and the bright sides starting from coping self-efficacy and local support. Given China being a vast country with many unique cultures that even vary widely across regions, cultural distance can be a common and salient stressor for international students and undermine their acculturation and adjustment if this stressor is left unrecognized and unresolved. University counsellors need to recognize the necessity of bridging cultural gaps perceived by the students, through orientation programs, regular-based and thematically diverse trainings, and informal leisure workshops. These activities can be utilized to introduce China’s national and regional cultures since a better understanding can help reduce perceived cultural distance. The moderation role of support from locals in buffering detrimental effects of cultural distance informs that these activities can be designed more wisely by inviting domestic students to share, discuss and collaborate with international students. The mixing strategy with cooperative attitudes and common interest potentially creates a win-win situation: enhancing both parties’ multi-cultural awareness and knowledge, providing reciprocal support resources, and increasing chances of intercultural engagement. The cognitive factor of coping self-efficacy is more complex for improvement. Encouragingly, studies have evidenced that coping self-efficacy was dynamic and can be improved via psycho-educational interventions designed for international students (Elemo & Türküm, 2019; Smith & Khawaja, 2014). The interventions emphasized varied experimental assignments, such as sharing and discussing coping strategies in past sojourn experiences and brainstorming coping strategies in future sojourn experiences. Educators, counselors and administrators can apply these evidence-based interventions while taking local sociocultural features into account. Two extra aspects may need to be integrated into the interventions. First, international students should be made aware of the importance of achieving a fit between stressful events and coping strategies. For instance, problem-focused coping may be more adaptive when stressors are evaluated as controllable, while emotion-focused coping may be more adaptive when stressors are evaluated as uncontrollable (Chesney et al., 2006). Second, given that self-efficacy is accumulated through successful experiences, intervention instructors need to provide positive and timely feedback to international students who have effectively or innovatively coped with a stressful event. We also suggest that host universities update their counseling programs by regularly evaluating international students’ acculturative stress. Thus, international students at risks can be identified and given counseling guidance and adequate support to help them recover from the stress.

Limitations and future research recommendations

Despite the above-mentioned contributions and implications evidenced from the study, some limitations need to be acknowledged. First, our cross-sectional design requires caution to refer to the investigated relationships as causal relationships. Future research can collect longitudinal data to gain more insights into these relationships. Second, this study merely focused on one source of social support (i.e., support from locals). However, recent studies were increasingly aware of the importance of differentiating predictive roles of social support from multiple sources. Thus, future research can simultaneously examine social support from co-ethnics, host-nationals and multi-national peers. In addition, Bender et al.’s (2019) meta-analysis showed that subjective and objective support functioned differently in international students’ psychological outcomes. Thus, future research can take into account the two types of support and provide empirical evidence on their more nuanced differences. Third, we did not collect much demographic information due to the large number of items in the questionnaire. Future research can address the limitation by collecting more demographics (e.g., language ability, academic field, prior experiences and socio-economic status) to better understand international students’ adjustment in China. Finally, it should be noted that our study was carried out after the outbreak of the Covid-19 pandemic. This pandemic has substantially affected management practices (e.g., social distancing and quarantine policies), teachers’ teaching methods (e.g., transferring traditional classroom teaching to online teaching), and students’ mental health (e.g., anxiety and depression) in higher education worldwide (Allen et al., 2022; Tao et al., 2022). The negative effects can be particularly salient for international students, including those sojourning in China (English et al., 2022; Meng et al., 2022). However, our study did not examine the pandemic-related constructs (e.g., fear of Covid-19, anxiety about Covid-19, and precautionary behaviors) that may play important roles in international student adjustment. Therefore, future research is recommended to utilize JD-R and test how demands and resources relevant to the Covid-19 pandemic can be related to international student adjustment.

Funding

The current study was supported by the National Social Sciences Fund of China (Grant number: 19BSH116).

Data availability

The data set used in this study can be available from the first author upon reasonable request.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Ethical approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. This article does not contain any studies with animals performed by any of the authors.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Chun Cao, Email: caogecheng@aliyun.com.

Qian Meng, Email: mengqianlucky@aliyun.com.

References

- Aiken LS, West SG. Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. Sage; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Allen R, Kannangara C, Vyas M, Carson J. European university students’ mental health during COVID-19: Exploring attitudes towards COVID-19 and governmental response. Current Psychology. 2022 doi: 10.1007/s12144-022-02854-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bae SM. The relationship between social capital, acculturative stress and depressive symptoms in multicultural adolescents: Verification using multivariate latent growth modeling. International Journal of Intercultural Relations. 2020;74:127–135. doi: 10.1016/j.ijintrel.2019.11.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bakker AB, Demerouti E. Job demands-resources theory: Taking stock and looking forward. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology. 2017;22(3):273–285. doi: 10.1037/ocp0000056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bender M, van Osch Y, Sleegers W, Ye M. Social support benefits psychological adjustment of international students: Evidence from a meta-analysis. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology. 2019;50(7):827–847. doi: 10.1177/0022022119861151. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Benet-Martinez V, Haritatos J. Bicultural identity integration (BII): Components and psychosocial antecedents. Journal of Personality. 2005;73(4):1015–1050. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6494.2005.00337.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boulton MJ. Associations between adults’ recalled childhood bullying victimization, current social anxiety, coping, and self-blame: evidence for moderation and indirect effects. Anxiety Stress & Coping. 2013;26(3):270–292. doi: 10.1080/10615806.2012.662499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao C, Zhu C, Meng Q. An exploratory study of inter-relationships of acculturative stressors among Chinese students from six European Union (EU) countries. International Journal of Intercultural Relations. 2016;55:8–19. doi: 10.1016/j.ijintrel.2016.08.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cao C, Meng Q. Effects of online and direct contact on Chinese international students’ social capital in intercultural networks: testing moderation of direct contact and mediation of global competence. Higher Education. 2020;80:625–643. doi: 10.1007/s10734-020-00501-w. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cao C, Shang L, Meng Q. Applying the job demands-resources model to exploring predictors of innovative teaching among university teachers. Teaching and Teacher Education. 2020;89:103009. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2019.103009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cao C, Zhu C, Meng Q. Chinese international students’ coping strategies, social Support resources in response to academic stressors: Does heritage culture or host context matter? Current Psychology. 2021;40:242–252. doi: 10.1007/s12144-018-9929-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cao C, Meng Q. A systematic review of predictors of international students’ cross-cultural adjustment in China: current knowledge and agenda for future research. Asia Pacific Education Review. 2022;23:45–67. doi: 10.1007/s12564-021-09700-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cao C, Zhang J, Meng Q. A social cognitive model predicting international students’ cross-cultural adjustment in China. Current Psychology. 2022 doi: 10.1007/s12144-022-02784-x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chen G, Kirkman BL, Kim K, Farh CI, Tangirala S. When does cross-cultural motivation enhance expatriate effectiveness? A multilevel investigation of the moderating roles of subsidiary support and cultural distance. Academy of Management Journal. 2010;53(5):1110–1130. doi: 10.5465/amj.2010.54533217. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chesney MA, Neilands TB, Chambers DB, Taylor JM, Folkman S. A validity and reliability study of the coping self-efficacy scale. British Journal of Health Psychology. 2006;11(3):421–437. doi: 10.1348/135910705X53155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cura, Ü., & Işık, A. N. (2016). Impact of acculturative stress and social support on academic adjustment of international students. Edu Sci 41, pp. 333–347.

- Demes KA, Geeraert N. Measures matter: Scales for adaptation, cultural distance, and acculturation orientation revisited. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology. 2014;45(1):91–109. doi: 10.1177/0022022113487590. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dicke T, Stebner F, Linninger C, Kunter M, Leutner D. A longitudinal study of teachers’ occupational well-being: Applying the job demands-resources model. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology. 2018;23(2):262–277. doi: 10.1037/ocp0000070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding X. Exploring the experiences of international students in China. Journal of Studies in International Education. 2016;20(4):319–338. doi: 10.1177/1028315316647164. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Elemo AS, Türküm AS. The effects of psychoeducational intervention on the adjustment, coping self-efficacy and psychological distress levels of international students in Turkey. International Journal of Intercultural Relations. 2019;70:7–18. doi: 10.1016/j.ijintrel.2019.02.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- English AS, Zeng ZJ, Ma JH. The stress of studying in China: Primary and secondary coping interaction effects. Springerplus. 2015;4(1):1–14. doi: 10.1186/s40064-015-1540-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- English AS, Yang Y, Marshall RC, Nam BH. Social support for international students who faced emotional challenges midst Wuhan’s 76-day lockdown during early stage of the COVID-19 pandemic. International Journal of Intercultural Relations. 2022;87:1–12. doi: 10.1016/j.ijintrel.2022.01.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finch BK, Vega WA. Acculturation stress, social support, and self-rated health among Latinos in California. Journal of Immigrant Health. 2003;5(3):109–117. doi: 10.1023/A:1023987717921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gong Y, Fan J. Longitudinal examination of the role of goal orientation in cross-cultural adjustment. Journal of Applied Psychology. 2006;91(1):176–184. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.91.1.176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gutiérrez M, Tomás JM, Romero I, Barrica JM. Perceived social support, school engagement and satisfaction with school. Revista de Psicodidáctica. 2017;22(2):111–117. doi: 10.1016/j.psicod.2017.01.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hall ET. Beyond culture. Doubleday; 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Hobfoll SE. The influence of culture, community, and the nested-self in the stress process: Advancing conservation of resources theory. Applied Psychology. 2001;50(3):337–421. doi: 10.1111/1464-0597.00062. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hu LT, Bentler PM. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling. 1999;6(1):1–55. doi: 10.1080/10705519909540118. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hua J, Zheng L, Zhang G, Fan J. Proactive personality and cross-cultural adjustment: A moderated mediation model. International Journal of Intercultural Relations. 2019;72:36–44. doi: 10.1016/j.ijintrel.2019.06.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kim YY. Becoming intercultural: An integrative theory of communication and cross-cultural adaptation. Sage; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Kim Y, Wang Y, Oh J. Digital media use and social engagement: How social media and smartphone use influence social activities of college students. Cyberpsychology Behavior and Social Networking. 2016;19(4):264–269. doi: 10.1089/cyber.2015.0408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ladum A, Burkholder GJ. Psychological adaptation of international students in the northern part of Cyprus. Higher Learning Research Communications. 2019;9(1):1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Lai DW, Li J, Lee VW, Dong X. Environmental factors associated with Chinese older immigrants’ social engagement. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2019;67(S3):S571–S576. doi: 10.1111/jgs.15899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee MY, Lee MK, Lee MJ, Lee SM. Academic burnout profiles and motivation styles among Korean high school students. Japanese Psychological Research. 2020;62(3):184–195. doi: 10.1111/jpr.12251. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li M, Wang Z, Gao J, You X. Proactive personality and job satisfaction: The mediating effects of self-efficacy and work engagement in teachers. Current Psychology. 2017;36(1):48–55. doi: 10.1007/s12144-015-9383-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Marsh HW, Wen Z, Hau KT. Structural equation models of latent interactions: evaluation of alternative estimation strategies and indicator construction. Psychological Methods. 2004;9(3):275–300. doi: 10.1037/1082-989X.9.3.275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melato SR, Van Eeden C, Rothmann S, Bothma E. Coping self-efficacy and psychosocial well-being of marginalised South African youth. Journal of Psychology in Africa. 2017;27(4):338–344. doi: 10.1080/14330237.2017.1347755. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Meng Q, Li A, Zhang H. How can offline and online contact predict intercultural communication effectiveness? Findings from domestic and international students in China. International Journal of Intercultural Relations. 2022;89:63–78. doi: 10.1016/j.ijintrel.2022.05.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mudrak J, Zabrodska K, Kveton P, Jelinek M, Blatny M, Solcova I, Machovcova K. Occupational well-being among university faculty: A job demands-resources model. Research in Higher Education. 2018;59(3):325–348. doi: 10.1007/s11162-017-9467-x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nadimpalli SB, Kanaya AM, McDade TW, Kandula NR. Self-reported discrimination and mental health among Asian Indians: Cultural beliefs and coping style as moderators. Asian American Journal of Psychology. 2016;7(3):185–194. doi: 10.1037/aap0000037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oppedal B, Idsoe T. The role of social support in the acculturation and mental health of unaccompanied minor asylum seekers. Scandinavian Journal of Psychology. 2015;56(2):203–211. doi: 10.1111/sjop.12194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Podsakoff PM, MacKenzie SB, Lee JY, Podsakoff NP. Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. Journal of Applied Psychology. 2003;88(5):879–903. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.88.5.879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rast III, Gaffney DE, Yang F. The effect of stereotype content on intergroup uncertainty and interactions. The Journal of Social Psychology. 2018;158(6):711–720. doi: 10.1080/00224545.2017.1407285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rienties B, Beausaert S, Grohnert T, Niemantsverdriet S, Kommers P. Understanding academic performance of international students: the role of ethnicity, academic and social integration. Higher Education. 2012;63(6):685–700. doi: 10.1007/s10734-011-9468-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rochelle TL, Shardlow SM. Health, functioning and social engagement among the UK Chinese. International Journal of Intercultural Relations. 2014;38:142–150. doi: 10.1016/j.ijintrel.2013.08.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rodebaugh TL. Self-efficacy and social behavior. Behaviour research and therapy. 2006;44(12):1831–1838. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2005.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarason IG, Sarason BR, Shearin EN, Pierce GR. A brief measure of social support: Practical and theoretical implications. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships. 1987;4(4):497–510. doi: 10.1177/0265407587044007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schaufeli WB, Taris TW. A critical review of the job Demands-resources model: Implications for improving work and health. In: Bauer GF, Hämmig O, editors. Bridging occupational, organizational and public health. Springer; 2014. pp. 43–68. [Google Scholar]

- Shrout PE, Bolger N. Mediation in experimental and nonexperimental studies: New procedures and recommendations. Psychological Methods. 2002;7(4):422–445. doi: 10.1037/1082-989X.7.4.422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith RA, Khawaja NG. A group psychological intervention to enhance the coping and acculturation of international students. Advances in Mental Health. 2014;12(2):110–124. doi: 10.1080/18374905.2014.11081889. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tao Y, Hou W, Niu H, Ma Z, Zhang S, Zhang L, Liu X. Centrality and bridge symptoms of anxiety, depression, and sleep disturbance among college students during the COVID-19 pandemic-a network analysis. Current Psychology. 2022 doi: 10.1007/s12144-022-03443-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taušová J, Bender M, Dimitrova R, van de Vijver F. The role of perceived cultural distance, personal growth initiative, language proficiencies, and tridimensional acculturation orientations for psychological adjustment among international students. International Journal of Intercultural Relations. 2019;69:11–23. doi: 10.1016/j.ijintrel.2018.11.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ucar FM, Sungur S. The role of perceived classroom goal structures, self-efficacy, and engagement in student science achievement. Research in Science & Technological Education. 2017;35(2):149–168. doi: 10.1080/02635143.2017.1278684. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ward C, Kennedy A. The measurement of sociocultural adaptation. International Journal of Intercultural Relations. 1999;23(4):659–677. doi: 10.1016/S0147-1767(99)00014-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ward C, Bochner S, Furnham A. The psychology of culture shock. 2. Routledge; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Ward C, Leong CH, Low M. Personality and sojourner adjustment: An exploration of the Big Five and the cultural fit proposition. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology. 2004;35(2):137–151. doi: 10.1177/0022022103260719. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Watson JC, Watson AA. Coping self-efficacy and academic stress among Hispanic first-year college students: The moderating role of emotional intelligence. Journal of College Counseling. 2016;19(3):218–230. doi: 10.1002/jocc.12045. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wen W, Hu D, Hao J. International students’ experiences in China: Does the planned reverse mobility work? International Journal of Educational Development. 2018;61:204–212. doi: 10.1016/j.ijedudev.2017.03.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson EV, Sheetz SD. A demands-resources model of work pressure in IT student task groups. Computers & Education. 2010;55(1):415–426. doi: 10.1016/j.compedu.2010.02.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Xanthopoulou D, Bakker AB, Dollard MF, Demerouti E, Schaufeli WB, Taris TW, Schreurs PJG. When do job demands particularly predict burnout? The moderating role of job resources. Journal of Managerial Psychology. 2007;22:766–786. doi: 10.1108/02683940710837714. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yang N, Xu Y, Chen X, Yu B, Yan H, Li S. Acculturative stress, poor mental health and condom-use intention among international students in China. Health Education Journal. 2018;77(2):142–155. doi: 10.1177/0017896917739443. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data set used in this study can be available from the first author upon reasonable request.