Abstract

Background: Training culturally competent graduates who can practice effectively in a multicultural environment is a goal of contemporary dental education. The Global Oral Health Initiative is a network of dental schools seeking to promote global dentistry as a component of cultural competency training. Objective: Before initiating international student exchanges, a survey was conducted to assess students’ awareness of global dentistry and interest in cross-national clerkships. Methods: A 22-question, YES/NO survey was distributed to 3,487 dental students at eight schools in seven countries. The questions probed students about their school's commitment to enhance their education by promoting global dentistry, volunteerism and philanthropy. The data were analysed using Vassarstats statistical software. Results: In total, 2,371 students (67.9%) completed the survey. Cultural diversity was seen as an important component of dental education by 72.8% of the students, with two-thirds (66.9%) acknowledging that their training provided preparation for understanding the oral health care needs of disparate peoples. A high proportion (87.9%) agreed that volunteerism and philanthropy are important qualities of a well-rounded dentist, but only about one-third felt that their school supported these behaviours (36.2%) or demonstrated a commitment to promote global dentistry (35.5%). In addition, 87.4% felt that dental schools are morally bound to improve oral health care in marginalised global communities and should provide students with international exchange missions (91%), which would enhance their cultural competency (88.9%) and encourage their participation in charitable missions after graduation (67.6%). Conclusion: The study suggests that dental students would value international exchanges, which may enhance students’ knowledge and self-awareness related to cultural competence.

Key words: Cultural competency training, global dentistry, international student exchanges, global survey, student perceptions

Introduction

Global health addresses the needs of vulnerable populations by reducing the burden of disease and improving health outcomes for populations. Globally, access to dental care for vulnerable populations in both developing and developed countries remains an issue. In 2010, examination of the global burden of untreated caries, severe periodontitis and severe tooth loss found that these conditions were prevalent in 3.9 billion individuals1 with the global economic burden of dental disease estimated at $442 billion in direct and indirect costs2. Over the 20-year period (1990-2010), the global burden of oral conditions has shifted from severe tooth loss towards severe periodontitis and untreated caries; untreated caries was the most prevalent oral condition1.

Poor and underserved regions of developing and developed countries suffer from limited access to oral care resources3, with poverty being an indicator of higher risk for disease. Oral health is linked to non-communicable chronic disease by many related risk factors4 and may serve as an indicator of overall health status5, poor nutritional status, microbial infections, immune disorders and oral cancer5., 6. which result in increased mortality and morbidity. In March 2015 the Japan Dental Association co-sponsored a conference on oral health with the World Health Organization (WHO). The main findings of this conference were that oral disease and the prevention of non-communicable diseases run parallel in terms of cost-effective screening, diagnosis and treatment efforts, and impact on the global burden of disease7 for both developed and developing countries.

The Global Oral Health Initiative is a network of dental schools seeking to foster the global advancement of dentistry, promote an appreciation for cultural and socio-economic diversity and reinforce the virtues of philanthropy and volunteerism8., 9., 10.. Before initiating international student and faculty exchanges, all participating schools agreed to conduct a survey of students to understand their awareness of volunteerism and their perception of the role of dental schools in improving oral health globally. The awareness of the relationship between oral disease and the global burden of disease resulted in the American Dental Association (ADA) recommendation that dental schools should include programmes that emphasise the needs of underserved populations11. A study of dental schools found that 82% integrate some cultural competence into their curricula as a component of existing courses12. The lecture/seminar format was the approach most commonly used; few schools required members of the faculty to undergo cultural competency training12., 13.. In the USA, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services has established The National Standards for Culturally and Linguistically Appropriate Services in Health and Health Care14, guidelines for creating environments to support patient–provider interaction and delivery of services in a culturally appropriate manner.

Course work in cultural competency creates an awareness of the relationship between socio-economic disparities that impact access to dental care15 and initiates cultural and self-awareness13, but it does not create a willingness to care for vulnerable populations16. Students often view the needs of vulnerable populations, particularly those living in poverty, as being distant from themselves17. While education can shape student perceptions regarding the needs of vulnerable populations, community outreach programmes provide experiential reinforcement of didactic coursework18., 19..

As a result, the ADA has recommended that dental schools create programmes in which students, residents and faculty provide care to underserved populations in community clinics and practices, including cultural competency training, to provide necessary knowledge and skills to deal with diverse populations11. The Commission on Dental Accreditation (CODA) also mandates dental curricula to ensure that graduates are competent in managing a diverse patient population and have the necessary interpersonal and communication skills to function successfully in a multicultural work environment20. The goal of integrating cross-cultural education is to produce graduate dentists who are culturally sensitive, socially aware and community-oriented15., 21..

With limited literature specific to global dentistry as a means to prepare culturally competent dentists, this study sought to understand students’ perceptions about their dental school education regarding volunteerism and philanthropy and the impact of international exchange programmes. A cross-national survey of 2,371 American, Bulgarian, Brazilian, Greek, Macedonian, Saudi Arabian and Indian dental students, at eight colleges of dentistry on five different continents, was translated into six languages with the objective to probe students’ perceptions of how global dentistry and philanthropy fit into the mission of contemporary dental education. The results were used to assess the interest of dental students in participating in cross-national clerkships with foreign dental schools. Among the anticipated benefits are improved understanding of contemporary dental education satisfying students’ interest in global dentistry and cross-national clerkships as a possible dimension of their cultural competency training.

Materials and methods

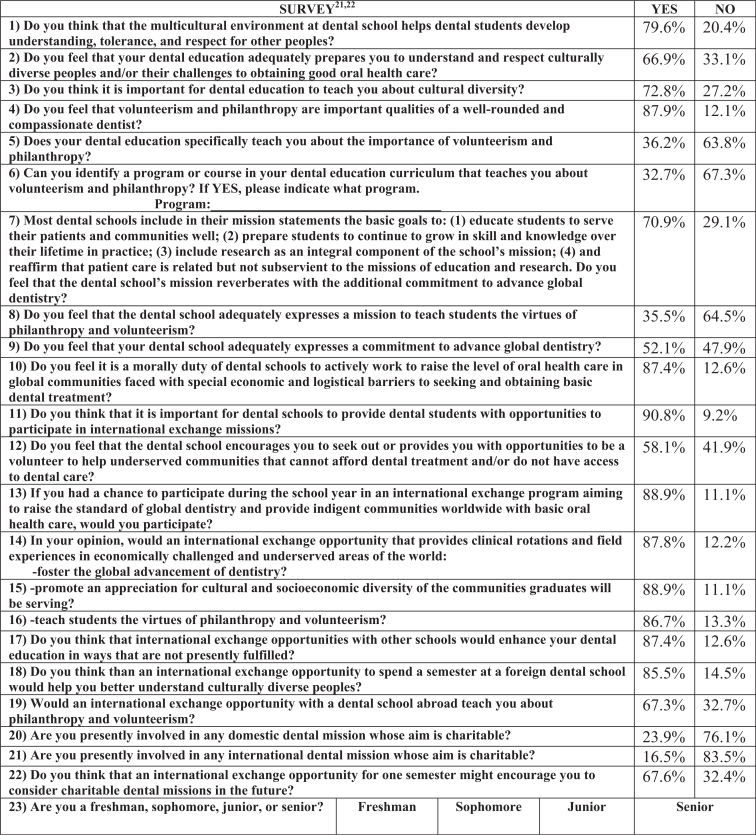

A team of educators and students from the USA and Bulgaria interacted via Skype to develop questions that would probe student perceptions regarding the role of their schools in supporting global dentistry and philanthropy22., 23.. The initial 22-question survey (Figure 1) was developed and reviewed by two translators who produced the Bulgarian language survey. The translated survey was then reviewed by the translators and one adjudicator to determine if the translation represented the questions’ original intent24., 25.. The survey was then translated from English into Greek, Portuguese, Macedonian and Arabic using the same procedure, and a retrospective think-aloud pretesting technique was used to harmonise the Bulgarian, Greek, Brazilian, Macedonian and Arabic language versions. A pilot test of the survey was carried out in which test respondents were debriefed to validate question equivalency and question content, ‘skip patterns’ and format25. After validating the survey in a pilot study in two of the schools22., 23., the survey was conducted at the other six schools. Data were collected according to the study protocols of each country.

Figure 1.

Survey (English text).

To ensure attention span was maintained throughout the questionnaire, the survey was limited to five closed-ended questions per minute with a total of 22 YES/NO questions26. Using the mission statements of each dental school, ADA recommendations and CODA requirements to formulate questions, the survey (Figure 1) focused on aspects of global dentistry such as volunteerism, cultural competency and philanthropy. One self-report question elicited data about students’ prior involvement in charitable dentistry. One question assessed students’ understanding of the intention of their training to make them culturally competent. Other questions assessed students’ perceptions about the fulfillment of those goals.

A total of 3,487 students (equivalent to years D1, D2, D3 and D4) in eight dental programmes – two in Bulgaria, and one each in Brazil, Greece (years 2–5), Macedonia, Saudi Arabia, India and the USA – were sent a letter by email describing the purpose of the survey and requesting voluntary participation, along with instructions for accessing the online survey through ‘Survey Monkey’. The dental schools that utilised the online survey sent a follow-up letter, 2 weeks later, to improve participation. Greece and India utilised paper versions of the survey; in these instances, students were asked to participate in the surveys during a lecture and assembly, respectively.

Descriptive statistics were performed on all the data and then according to institution (Tables 1 and 2). Differences in the percentage distribution of categorical variables across nationalities (YES = 1; NO = 0, P < 0.05) were analysed using a standard Pearson chi-square test27. The chi-square test was used to assess whether paired observations on polled responses from people at different schools in separate countries are independent of each other (i.e. to determine whether the response is affected by nationality)28. The data were analysed using Vassarstats statistical software. There were total 616 comparisons (28 possible comparative pairs among the eight schools) for all 22 questions. The schools were then ranked from lowest to highest, according to %YES answers, for each question, and were grouped according to their P-values, where chi-square P ≥ 0.05 indicated no significant difference in opinions for a particular question. Conversely, chi-square P< 0.05 indicated that the differences in the percentage of YES and NO answers between schools probably represent true substantive differences in opinion between student groups.

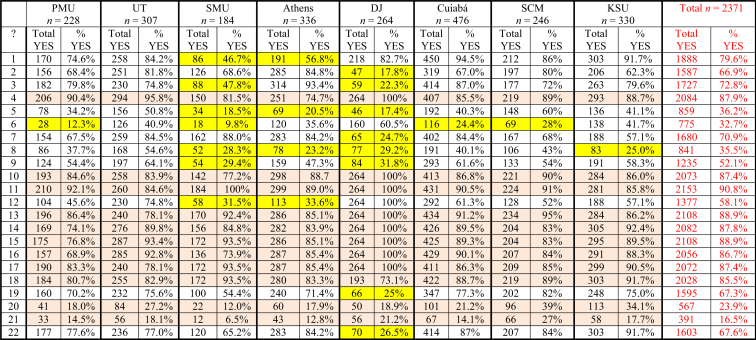

Table 1.

Collective count of ‘YES’ responses to survey questions from all institutions and a summary of chi-square test results for Questions 4, 10, 11, 13–18, 20 and 21. There are two possible responses to each question (YES/NO). The total percentage for the sum of YES and NO is 100% for all questions. Number values marked in red indicate the total count and percentage of ‘YES’ responses to each question from all institutions. The percentage of ‘YES’ responses for each institution that are highlighted in pink indicate that chi-square test P-values for each set of between-group comparisons are ≥ 0.05 for the given question and that group opinions were not significantly different from each other. There was unanimity among the groups for their responses to Questions 4, 10, 11, 13–18, 20 and 21. Number values highlighted in yellow indicate a significantly lower %YES response

Athens, University of Athens School of Dentistry (Greece); Cuiaba, University of Cuiaba College of Dentistry (Brazil); DJ, Divya Jyoti College of Dental Sciences and Research (India); KSU, King Saud University College of Dentistry (Saudia Arabia); PMU, Medical University of Plovdiv Faculty of Dental Medicine (Bulgaria); SCM, Sts. Cyril and Methodius University Faculty of Dentistry (Macedonia); SMU, Sofia Medical University Faculty of Dental Medicine (Bulgaria); UT, University of Tennessee Health Science Center College of Dentistry (USA).

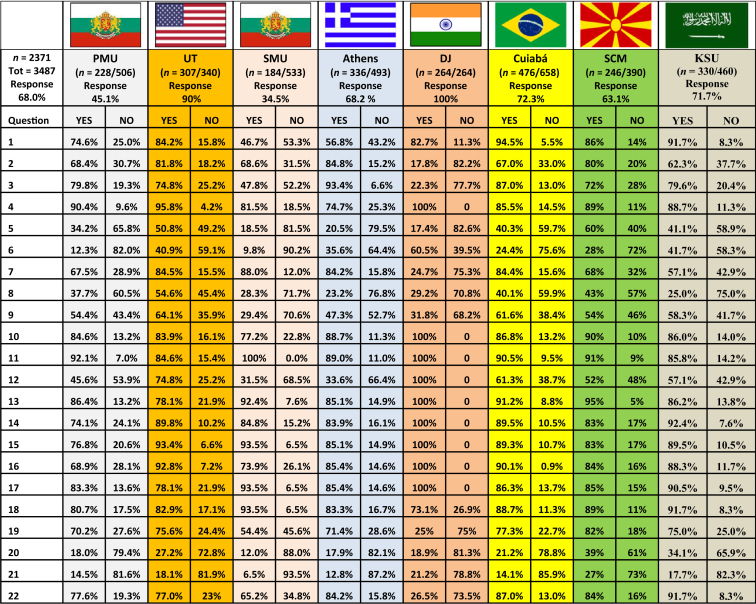

Table 2.

Percent ‘YES’ distribution of responses to survey questions, according to institution

Athens, University of Athens School of Dentistry (Greece); Cuiaba, University of Cuiaba College of Dentistry (Brazil); DJ, Divya Jyoti College of Dental Sciences and Research (India); KSU, King Saud University College of Dentistry (Saudia Arabia); PMU, Medical University of Plovdiv Faculty of Dental Medicine (Bulgaria); SCM, Sts. Cyril and Methodius University Faculty of Dentistry (Macedonia); SMU, Sofia Medical University Faculty of Dental Medicine (Bulgaria); UT, University of Tennessee Health Science Center College of Dentistry (USA).

The Institutional Review Board (IRB) of the University of Tennessee Health Science Center (UT) deemed the study (#12-02040-XM) exempt under 45CFR46.101 (b)(2) as it involves educational tests, surveys, interview procedures or observation of public behaviour. The study was approved by the Central Commission of Research Ethics (Bulgarian Ministry of Education and Science), the IRBs of the Sofia Medical University Faculty of Dental Medicine (SMU) and the Medical University of Plovdiv Faculty of Dental Medicine (PMU); the Institutional Ethics Committee (IEC) of Divya Jyoti College of Dental Sciences and Research (DJ); and the IRBs of the University of Cuiabá College of Dentistry (Cuiabá), the University of Athens School of Dentistry (Athens), Sts. Cyril and Methodius University Faculty of Dentistry (SCM) and King Saud University College of Dentistry (KSU).

As the respective IRB or IEC at each school considered the anonymous survey an exempt application, no informed consent form was required. In accordance with the waiver, the researchers provided the participants at each school with a written summary about the research, including: (i) the purpose of the research; (ii) the time involved; (iii) assessment of minimal risk; (iv) statement regarding benefit to participants; (v) contact for questions about the research; and (vi) contact for questions about rights as a research participant. The cover letter accompanying the survey served as the ‘implied’ informed consent form, whereby a statement contained in the letter indicated that completion and return of the survey implies consent to participate in the research. For participants in the Internet-based survey, the implied informed consent was obtained by presenting participants with the consent information and informing them that their consent is implied by submitting the completed survey. The survey did not ask for any identifiable information and was conducted in full accordance with The World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki.

Results

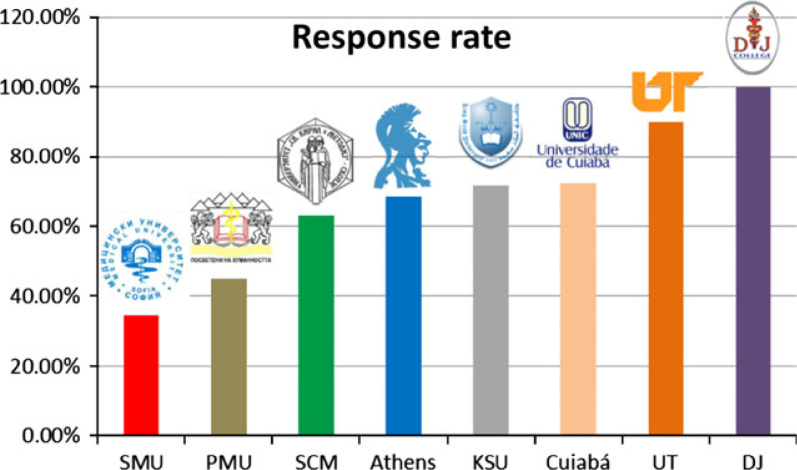

Of the 3,487 students initially approached, 2,371 completed the survey, giving a response rate of 67.9%. The response rates for the dental schools were: UT (USA), 90%; SMU and PMU (Bulgaria), 34.5% and 45.1% respectively, 39.6% collectively; Cuiabá (Brazil), 72.1%; Athens (Greece), 68.2%; SCM (Macedonia), 63.1%; KSU (Saudi Arabia), 71.1%; and DJ (India), 100% (Figure 2). The percentage of ‘YES’ responses to each question from each institution are presented in Tables 1 and 2. The margin of error for the entire sample (n = 2371) was ±0.3 at 99% confidence level (for individual institutions: UT, ±1.75 at 95% confidence level; SMU, ±5.85 at 95% confidence level; PMU, ±4.82 at 95% confidence level; Athens, ±3.02 at 95% confidence level; DJ, ±0 at 95% confidence level; Cuiabá, ±2.36 at 95% confidence level; SCM, ±3.8 at 95% confidence level; and KSU, ±2.87 at 95% confidence level).

Figure 2.

Response rates according to institution. Athens, University of Athens School of Dentistry (Greece); Cuiabá, University of Cuiabá College of Dentistry (Brazil); DJ, Divya Jyoti College of Dental Sciences and Research (India); KSU, King Saud University College of Dentistry (Saudi Arabia); PMU, Medical University of Plovdiv Faculty of Dental Medicine (Bulgaria); SCU, Sts. Cyril and Methodius University Faculty of Dentistry (Macedonia, FYROM), Sofia Medical University Faculty of Dental Medicine (Bulgaria); UT, University of Tennessee Health Science Center College of Dentistry (USA).

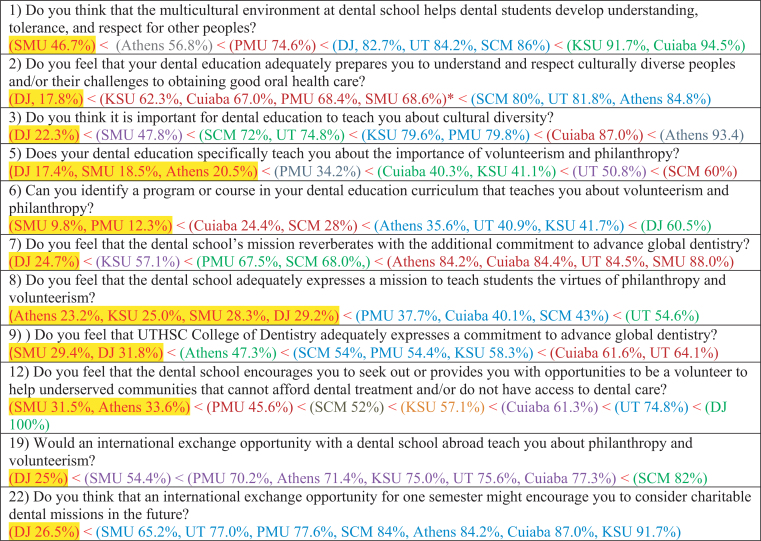

The greatest %YES distribution among institutions was found for Questions 1, 2, 3, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 12, 19 and 22 (Table 3). There was unanimity among the groups in their responses to Questions 4, 10, 11, 13–18, 20 and 21, with each comparison between schools (P ≥ 0.05) indicating no significant difference in opinion (Table 1) and that the students were likely to agree with each other on the issues, regardless of their nationality.

Table 3.

Summary of chi-square test results for Questions 1, 2, 3, 5–9, 12, 19 and 22

The schools are ranked from lowest to highest according to the %YES values obtained in response to each question. Schools with chi-square test values of P ≥ 0.05 for a given question are grouped together and colour-coded accordingly to indicate that their opinions were not significantly different from each other. Schools shown in different print colours for each set of between-group comparisons indicate chi-square values of P< 0.05 and that the differences in %YES and %NO answers between schools probably represent true substantive differences in opinion between student groups. Athens, University of Athens School of Dentistry (Greece); Cuiabá, University of Cuiabá College of Dentistry (Brazil); DJ, Divya Jyoti College of Dental Sciences and Research (India); KSU, King Saud University College of Dentistry (Saudia Arabia); PMU, Medical University of Plovdiv Faculty of Dental Medicine (Bulgaria); SCM, Sts. Cyril and Methodius University Faculty of Dentistry (Macedonia); SMU, Sofia Medical University Faculty of Dental Medicine (Bulgaria); UT, University of Tennessee Health Science Center College of Dentistry (USA).

In total, 79.6% concurred with the concept that multiculturalism supports development of the behaviours of understanding, tolerance and respect for other peoples (Q1). There was a wide range of responses to this statement according to the country of origin; for example, only half of the Bulgarian respondents (47%) agreed with this statement compared with a much higher number of Brazilian students (94.5%). Cultural diversity was seen as an important component of dental education by 72.8% of the students (Q3) with more than two-thirds (66.9%) acknowledging that their education provided preparation for understanding the needs of disparate peoples and the challenges of access to oral health care (Q2). The notable exception was the Indian students (17.8%) who overwhelmingly disagreed with their international colleagues. Only one (22.8%) student in five from India felt that cultural diversity was important to their dental education.

A total of 87.9% of the students agreed that volunteerism and philanthropy are important qualities of a well-rounded compassionate dentist (Q4), but only 36.2% felt that their dental education supported these behaviours (Q5). Consistent with the previous question, only 32.7% were able to identify a programme or course in their dental curriculum that specifically teaches them about volunteerism and philanthropy (Q6); 15.9% of US senior students were able to identify a local community-based dental mission in which they were required to participate.

In total, 70.9% of the respondents agreed that their dental school mission statements express an explicit commitment to advance global dentistry (Q7). However, only one-third of the respondents (35.5%) indicated that their programme demonstrates a commitment to promoting global dentistry (Q8,9). Moreover, 87.4% of the students felt that dental schools have a moral duty to improve the level of oral health care in global communities that face special socio-economic and logistical barriers to accessing basic equitable, quality dental care (Q10).

A high proportion (91%) of the students agreed with the importance for dental schools to provide students with opportunities to participate in international exchange missions (Q11). Over half (58.1%) of the students indicated that their dental school encouraged students to volunteer in underserved communities (Q12), with perceptions of no encouragement highest in the responses from Bulgarian (31.5%) and Greek (33.6%) students. Indian (100%) and US (74.8%) students felt that they were encouraged to volunteer in underserved areas, and 88.9% of students indicated a willingness to participate in an international exchange programme that aimed to raise the standard of global dentistry (Q13). The students agreed that clinical rotations and field experiences in underserved areas of the world would promote the global advancement of dentistry (87.8%), promote an appreciation for cultural and socio-economic diversity (88.9%) and teach students the virtues of philanthropy and volunteerism (86.7%) (Q14–16). Moreover, 87.4% felt that international exchange opportunities with other schools would enhance their dental education in ways that are not presently being provided (Q17).

The majority (85.5%) indicated that a semester-long international exchange opportunity at a foreign dental school would improve cultural competency (Q18) and broaden their perspectives regarding philanthropy and volunteerism (Q19). When asked if they were presently involved in any domestic dental charitable mission, just over one (23.9%) in five students reported YES (Q20). Although one (16.5%) in every six students also indicated that they were currently involved in a charitable international dental mission (Q21), only one American student named a specific programme. In total, 67.6% of the cohort indicated that an international exchange opportunity for one semester might encourage them to consider charitable dental missions in the future, but only 26.5% of Indian students agreed (Q22).

Discussion

Volunteerism and philanthropy were seen as important qualities of a well-rounded and compassionate dentist. However, students did not perceive these qualities as being strongly espoused or operationalised by their dental curriculum. The notable exceptions were Indian students who felt that the country had a moral duty to improve oral care, and the values were taught and reinforced by a range of compulsory experiential opportunities, integral to the Indian dental curriculum, with underserved indigent populations in nearby rural communities. Although the Indian students did not think that their dental education specifically taught the importance of volunteering and philanthropy, the mandatory experiential service-learning component of their curriculum fosters internalisation of the concepts. A follow-on study with the cohort should be conducted to see if they move from awareness to intentional action actually providing care to vulnerable populations and demonstrate increased self-efficacy and cultural competence16.

A further dichotomy arises with Indian students in that they did not feel that an international exchange opportunity for one semester would encourage them to consider future charitable dental missions. Yet, they unanimously agreed that the schools should provide international exchange missions to enhance their education and raise the standard of global health care. When considering the greater need in India compared with other nations in the study, the dichotomy raises a question of interpretation. Given the experiential learning opportunities integrated into the Indian dental curriculum, students may have perceived that international experiences would do little to add to their heightened sense of dedication to providing charitable care or viewed the question as referring to charitable care in other countries.

In comparison, nearly all the Bulgarian students were unable to identify a charitable care programme in their curriculum. The Bulgarian and Greek students had lower perceptions of school encouragement and commitment to serving in underserved regions. Angus Deaton, the Nobel Prize Laureate, writes that some countries have low average life evaluations, reflecting dissatisfaction with their lives and income29. Countries evolving out of communism into a more liberal democratic society also have low life evaluations, which may explain the responses of Bulgarian students. Brazilians’ life evaluations are only one point lower than those of US subjects, which is reflected in their responses. The differences in national responses reflect the impact of country-level influences, such as national wealth and educational attainment, societal collectivism and religiosity30 as well as how the constructs of volunteering are operationalised in dental programmes.

This cross-national study emphasises the gaps between the espoused values of dental schools and the perceptions and demonstrated behaviours of students. While improving oral health globally through volunteering is an espoused value, how social responsibility is operationalised in curriculum and reinforced with clinical experiences is evolving. Academic programmes will need to examine how best to reinforce a strong sense of social responsibility among future students.

Some studies show that contact with patients from diverse ethnic and cultural backgrounds during extramural rotations prepares students to interact with and treat such patients more competently beyond graduation31. Undergraduate humanitarian educational trips to underserved communities can have a significant personal, professional and social impact on dental students32. These missions can increase cultural education, self-confidence and public health awareness33.

Multidisciplinary service-learning programmes that involve dental students and faculty abroad may allow dental students to use their clinical skills in real-life situations. This has the potential to foster civic responsibility, while increasing students’ cultural awareness, cross-cultural communication skills and understanding of health-care challenges faced by disparate populations34. Evidence indicates that cross-cultural education in the classroom may enhance cross-cultural adaptability of students, but cross-cultural encounters expose students to social, environmental and cultural influences that affect health and diseases32., 35., 36., 37., 38..

On the whole, the survey suggests that dental education could do more to fulfill students’ expectations with regard to global dentistry. Although many students appear to be satisfied with current efforts to make them culturally competent, opportunities to engage them in global dentistry are probably insufficient. Philanthropy and volunteerism are not necessarily commensurate with cultural competence, but students do believe that global dentistry can enhance their cultural awareness. Many students feel that their dental education does not promote philanthropy and this was reflected in their responses to several questions that probed into this issue in various ways. While the students assumed that their school states a commitment to engage them in global dentistry, this commitment – contrary to perceptions – is not explicitly stated in the mission of any of the participating schools.

A limitation of the study was that the survey did not probe whether students recognise that local volunteer programmes can be as satisfying as humanitarian missions abroad. Poverty can be domestic as well as global, and one does not have to look far to find it. Future studies should investigate whether cross-national opportunities to reinforce intercultural communication skills taught in lectures and international externships to serve marginalised populations will enhance the likelihood that students will serve underserved communities in their clinical practice39., 40..

Conclusion

The study suggests that dental education programmes have room to improve both curricula and cross-cultural experiential opportunities. It demonstrates that dental students want their schools to provide them with international volunteer opportunities. Cross-national clerkships may enhance cultural competency training by reinforcing and promoting the internalisation of knowledge that will reduce racial and ethnic health disparities, both domestically and abroad.

Acknowledgements

To the Honorable Rossen Plevenliev, President of the Republic of Bulgaria; Mrs Irina Bokova, Director General of UNESCO; Commissioner Kristalina Georgieva, Miroslav Minev and Daniel Giorev, the European Commission for International Cooperation, Humanitarian Aid, and Crisis Response; Dr Andon Filchev, Dean of Sofia Medical University Faculty of Dental Medicine; Ronald C. Petrie, FNP-BC, Medical Attaché and His Excellency, Ambassador James B. Warlick Jr., American Embassy in Sofia, Bulgaria for their assistance in organising the student exchange programme. The authors also thank Dr Timothy L. Hottel (Dean), Ms Hannah Proctor and Mrs Brenda Scott for assistance in the survey at UTHSC College of Dentistry; Dr Andon Filchev (Dean) for assisting the survey at Sofia Medical University Faculty of Dental Medicine; Dr Mariana Atanasova Murdjeva (Vice-Rector of International Relations and Project Activity) and Dr Nina Musurlieva for assisting the survey at the Medical University of Plovdiv Faculty of Dental Medicine; Dr Ljupčo Gugučevski, Dean of Sts. Cyril and Methodius University Faculty of Dentistry; Dr Stuti Mohan, for assisting in the survey at Divya Jyoti College of Dental Sciences and Research, Dr Smiti Jassar Klaire, CEO, Divya Jyoti College of Dental Sciences and Research, for actively supporting student exchange programmes and research for the betterment of educational outcomes.

Funding

This study was supported by the Dean's Funds of: the University of Tennessee College of Dentistry, the Sofia Medical University Faculty of Dental Medicine, the Medical University of Plovdiv Faculty of Dental Medicine, Divya Jyoti College of Dental Sciences and Research, the University of Cuiaba School of Dentistry, the National Kappodistrian University of Athens Faculty of Dentistry, Sts. Cyril and Methodius University Faculty of Dentistry, and King Saud University College of Dentistry.

Competing interest

The authors have no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Marcenes W, Kassebaum NJ, Bernabé E, et al. Global burden of oral conditions in 1990-2010: a systematic analysis. J Dent Res. 2013;92:592–597. doi: 10.1177/0022034513490168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Listl S, Galloway J, Mossey PA, et al. Global economic impact of dental diseases. J Dent Res. 2015;94:1355–1361. doi: 10.1177/0022034515602879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Locker D. Deprivation and oral health: a review. Community Dent Oral Eipidemiol. 2000;28:161–169. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0528.2000.280301.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.World Health Organization. Strategies and approaches in oral disease prevention and health promotion: prevention and control of noncommunicable diseases (WHA53.17) [Internet]. Geneva; 2000 May 20. Available from: http://www.who.int/oral_health/strategies/en/014. Accessed 15 November 2015

- 5.Petersen PE. Challenges to improvement of oral health in the 21st century – the approach of the WHO Global Oral Health Programme. Int Dent J. 2004;54:329–343. doi: 10.1111/j.1875-595x.2004.tb00009.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sheiham A, Alexander D, Cohen L, et al. Global oral health inequalities: task group–implementation and delivery of oral health strategies. Adv Dent Res. 2011;23:259–267. doi: 10.1177/0022034511402084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.World Health Organization . World Health Organization; Geneva: 2015. Tokyo declaration on dental care and oral health for healthy longevity [Internet] April 2. Available from: http://www.who.int/oral_health/tokyodeclaration032015/en/. Accessed 15 November 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ivanoff CS. Proceedings of the Global Health & Innovation Conference (GHIC 2014) Yale University; New Haven, CT: 2014. Cross-national clerkships and cultural competence training in the predoctoral dental curriculum: an innovative global oral health initiative. April 12-13; Available from: http://www.uniteforsight.org/conference/speakers-2014#pitches. Accessed 10 November 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ivanoff CS, Hottel TL, Yaneva K, et al. Proceeding of the 141st Annual APHA Annual Meeting and Expo. Boston, MA; 2013. Cross-national clerkships and cross-cultural training in the predoctoral dental curriculum: a multidisciplinary global health initiative. November 2-6; Available from: https://apha.confex.com/apha/141am/webprogram/Paper277295.html. Accessed 10 November 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ivanoff CS. Proceedings of The 2014 Peace and Stability Operations Training and Education Workshop (PSOTEW), Office of the Deputy Assistant Secretary of Defense (Readiness) for the Department of Defense. George Mason University; Arlington, VA: 2014. Partnerships and innovation: novel approaches to training, educating, and engaging in peacekeeping and stability operations. An innovative global health initiative to complement the State Partnership Program. March 26; Available from: http://pksoi.army.mil/conferences/psotew/. Accessed 10 November 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 11.American Dental Association Future of dentistry: education chapter. J Am Coll Dent. 2002;19:18–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rowland ML, Bean CY, Casamassimo PS. A snapshot of cultural competency education in U.S. dental schools. J Dent Educ. 2006;70:982–990. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pilcher ES, Charles LT, Lancaster CJ. Development and assessment of a cultural competency curriculum. J Dent Educ. 2008;72:1020–1028. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. The national standards for culturally and linguistically appropriate services in health and health care [Internet]. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Available from: https://www.thinkculturalhealth.hhs.gov/Content/clas.asp. Accessed 15 November 2015

- 15.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services . U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research, National Institutes of Health; Rockville, MD: 2000. Oral health in America: a report of the surgeon general [Internet] Available from: www.nidcr.nih.gov/DataStatistics/SurgeonGeneral/default.htm. Accessed 15 November 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gundersen D, Bhagavatula P, Pruszynski JE, et al. Dental students’ perceptions of self-efficacy and cultural competence with school-based programs. J Dent Educ. 2012;76:1175–1182. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Reis CM, Rodriguez C, Macaulay AC, et al. Dental students’ perceptions of and attitudes about poverty: a Canadian participatory case study. J Dent Educ. 2014;78:1604–1614. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Coe JM, Best AM, Warren JJ, et al. Service-learning's impact on dental students’ attitude towards community service. Eur J Dent Educ. 2015;19:131–139. doi: 10.1111/eje.12113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Brondani MA. Teaching social responsibility through community service-learning in predoctoral dental education. J Dent Educ. 2012;76:609–619. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Commission on Dental Accreditation . American Dental Association; Chicago: 2007. Accreditation Standards for Dental Education Programs. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Davis EL, Stewart DCL, Guelmann M, et al. Serving the public good: challenges of dental education in the twenty-first century. J Dent Educ. 2007;71:1009–1019. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ivanoff CS, Ivanoff AE, Yaneva K, et al. Student perceptions about the mission of dental schools to advance global dentistry and philanthropy. J Dent Educ. 2013;77:1258–1269. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ivanoff CS, Ivanoff AE, Yaneva-Ribagina K, et al. Cтyдeнтcки възпpиятия oтнocнo oбpaзoвaтeлнa миcия нa дeнтaлнитe yчeбни зaвeдeния зa paзвитиeтo нa глoбaлнaтa дeнтaлнa мeдицинa и филaнтpoпия. Health Policy and Management (Здpaвнa пoлитикa и мeниджмънт) 2015;14:65–79. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Harkness JA. In: Cross-Cultural Survey Methods. Harkness JA, Van de Vijver FJR, Mohler PPH, editors. John Wiley; Hoboken, NJ: 2003. Questionnaire translation; pp. 33–56. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Survey Research Center . Survey Research Center, Institute for Social Research, University of Michigan; Ann Arbor, MI: 2010. Guidelines for Best Practice in Cross-Cultural Surveys. [Google Scholar]

- 26.SurveyMonkey. Response rates and surveying techniques tips to enhance survey respondent participation, 2009 [Internet]. Survey Monkey. Available from: http://s3.amazonaws.com/SurveyMonkeyFiles/Response_Rates.pdf. Accessed 15 November 2015

- 27.Kim JS, Dailey R. Wiley Munksgaard; Ames, IA: 2008. Biostatistics for Oral Health Care. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Harkness JA. In: Measuring Attitudes Cross-Nationally: Lessons from the European Social Survey. Jowell R, Roberts C, Fitzgerald R, Eva G, editors. Sage; London: 2007. Improving the comparability of translation; pp. 79–94. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Deaton A. Income, health, and well-being around the world: evidence from the Gallup World Poll. J Econ Perspect. 2008;22:53–72. doi: 10.1257/jep.22.2.53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Parboteeah KP, Cullen JB, Lim L. Formal volunteering: a cross-national test. J World Bus. 2004;39:431–441. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Thind A, Atchison K, Andersen R. What determines positive student perceptions of extramural clinical rotations? An analysis using 2003 ADEA senior survey data. J Dent Educ. 2005;69:355–362. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bimstein E, Gardner QW, Riley JL, et al. Educational, personal, and cultural attributes of dental students’ humanitarian trips to Latin America. J Dent Educ. 2008;72:1493–1509. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wynn LA, Krause DW, Kucine A, et al. Evolution of a humanitarian dental mission to Madagascar from 1999 to 2008. J Dent Educ. 2010;74:289–296. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Martinez-Mier EA, Soto-Rojas AE, Stelzner SM, et al. An international, multidisciplinary, service-learning program: an option in the dental school curriculum. Educ Health. 2011;24:259. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Magee KW, Darby ML, Connolly IM, et al. Cultural adaptability of dental hygiene students in the United States: a pilot study. J Dent Hyg. 2004;78:22–29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Damiano PC, Brown ER, Johnson JD, et al. Factors affecting dentist participation in a state Medicaid program. J Dent Educ. 1990;54:638–643. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Eklund SA, Pittman JL, Clark SJ. Michigan Medicaid's Healthy Kids dental program: an assessment of the first twelve months. J Am Dent Assoc. 2003;134:1509–1515. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.2003.0083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Huang C, Bian Z, Tai B, et al. Dental education in Wuhan, China: challenges and changes. JDE. 2007;71:304–311. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Berg R, Berkey DB. University of Colorado School of Dentistry's advanced clinical training and service program. J Dent Educ. 1999;63:938–943. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Graham BS. Educating dental students about oral health care access disparities. J Dent Educ. 2006;70:1208–1211. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]