Abstract

Aims: Attitudes of dentists and dental hygienists towards extended scope and independent dental hygiene practice are described in several studies, but the results are heterogenous. The purpose of this systematic review was to compare the attitudes of dentists and dental hygienists towards extended scope and independent dental hygiene practice. Methods: PubMed, AMED and CINAHL were screened by two independent assessors to identify relevant studies. Only quantitative studies that reported the percentages of dentists' and dental hygienists' attitude towards extended scope and independent dental hygiene practice were included. The random-effects model was used to synthesise possible heterogenous influences. Results: Meta proportions with regard to a positive attitude towards extended scope of practice are 0.54 for dentists and 0.81 for dental hygienists. Meta proportions of a positive attitude towards independent practice are 0.14 for dentists and 0.59 for dental hygienists. A meta analysis with regard to negative attitudes could only be performed on extended scope of practice and did not reveal a difference between the two professions. We obtained homogeneous outcomes of the studies included regarding negative attitudes of dentists . A minority of dentists hold negative attitudes towards extended scope of dental hygiene practice. Study outcomes regarding negative attitudes of dental hygienists were heterogeneous. Conclusions: Positive attitudes are present among a majority of dentists and dental hygienists with regard to extended scope of dental hygiene practice, while for independent dental hygiene practice this holds for a minority of dentists and a majority of dental hygienists.

Key words: Dental practice, general dental practice, hygienist, oral health policy, primary oral health care

Introduction

Dentists and dental hygienists are the two most prominent professions within the community delivering oral health care. Since its establishment in 19131, the profession of dental hygiene has changed drastically2. New legislation has enabled an extended scope and independent dental hygiene practice in many different countries3., 4., 5., 6., 7., 8., 9., 10.. Both policies are part of task shifting. The latter consists not only of rational distribution of tasks (extended scope of practice) between dentists and dental hygienists, but also independent practice. Extended scope of practice and independent practice may enhance efficiency11., 12., reduce costs13, increase patient comfort12., 14., 15. and make oral health care more accessible16. However, attitudes towards extended dental hygiene scope and independent dental hygiene practice, and potential differences in attitudes between professions, are currently unclear.

Attitude is defined as “a psychological tendency that is expressed by evaluating a particular entity with some degree of favor or disfavor”17. A positive attitude of dentists and dental hygienists towards these policies is required for task shifting. Professional status, culture and professionalisation issues can provide cues to the expected directions and magnitude of attitudes towards professional change among dentists and dental hygienists18., 19., 20., 21., 22., 23.. Several studies have investigated attitudes of dentists and dental hygienists towards the extended scope of practice and independent practice of dental hygienists24., 25., 26.. The findings are somewhat fragmentary and inconclusive. Therefore, the purpose of this systematic review was to compare attitudes of dentists and dental hygienists towards extended scope and independent dental-hygiene practice.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Four criteria were applied when considering if studies were suitable for inclusion: types of studies; types of participants; types of interventions; and types of outcome measures. All relevant cross-sectional surveys that focussed on extended scope of dental hygiene practice or independent dental-hygiene practice were included, as were all studies that provided information on attitudes regarding these two policies. Furthermore, no interventions were considered or included in this study. Finally, two types of outcome measures were relevant to our review: the proportions of practitioners with a positive or negative attitude towards an extended scope of dental hygiene practice; and the proportions of practitioners with a positive or negative attitude towards an independent dental hygiene practice according to dentists and dental hygienists. A positive attitude is defined as an evaluation of an entity that is good, useful, has good qualities, or of which one is being certain or sure that it is correct or true27. A negative attitude is defined as the opposite of a positive attitude.

Search methods for the identification of studies

In order to determine synonyms or related terminology of extended scope of practice and independent practice, the MeSH database was used. In addition, an exploratory literature search regarding synonyms or related terminology was conducted in PubMed using a Boolean search: tasks [All Fields] AND (‘dentists’ [MeSH Terms] OR ‘dentists’ [All Fields]) AND (‘dental hygienists’ [MeSH Terms] OR (‘dental’ [All Fields] AND ‘hygienists’ [All Fields]) OR ‘dental hygienists’ [All Fields]) OR (‘oral’ [All Fields] AND ‘hygienist’ [All Fields]).

To overcome the problem of not identifying all relevant publications, the ‘related articles’ function in PubMed was used as replacement of a full search28. This search function compares words from titles, abstracts and MeSH headings assigned using a powerful word-weighted algorithm29. The first, most relevant, publication, as found in the Boolean search, was used as a starting point of the related articles search. The publication of Abelsen & Olsen26 was the first publication relevant to the purpose of this study. Next, the publications associated with the content of the study of Abelsen & Olsen26 were identified using the related articles function in PubMed. Additionally, a search was performed in the AMED and CINAHL databases.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

Two assessors (J.J.R. and P.O.) independently screened all identified titles and excluded studies clearly not relevant to the topic. After title screening, agreement between the two independent assessors was calculated using Cohen's kappa coefficient30. According to Fleiss31 kappa values below 0.40 should be regarded as poor agreement, those between 0.40 and 0.75 as fair to good agreement and those exceeding 0.75 as excellent agreement. Title screening was followed by a consensus meeting between the two assessors to make a final selection of titles. When in doubt, abstracts were screened to determine their relevance. Then, one assessor (J.J.R.) screened all abstracts of the final list of titles to verify whether the corresponding studies were surveys measuring attitudes of dentists or dental hygienists.

Eligibility criteria were used (Table 1) for final selection of articles, such as cross-sectional surveys reporting the percentage or the proportion of dental or dental-hygiene practitioners with respect to positive or negative attitude towards expanded scope of practice or independent practice. Qualitative studies, or those using attitude measures based on multiple aspects, were excluded. The relevance of the final list of included studies was verified by the second assessor (P.O.).

Table 1.

Eligibility criteria for the literature-selection process

| Inclusion | Exclusion |

|---|---|

| Name or synonym of profession or discipline (e.g. dentist, GDP, dental hygienist or ADHP) | Other oral health professions (e.g. dental therapist) |

| Terms related to scope of practice, direct access independent practice and/or interprofessional or interdisciplinary change | Perspectives from a policy point of view |

| Terms related to attitude or perception | Publication based on one or few opinions |

| Quantitative research method | Qualitative research method |

| Terms or words referring to professional relationship between dental hygienists and dentists | Publication language other than English or Dutch |

| Indices related to percentages | Continuing professional development |

| Subjects related to specific clinical issues | Only faculty members or teachers |

| Attitude measures regarding task shifting and/or independent practice | Specialised dentists or dental hygienists |

| Percentages of dental or dental hygiene practitioners with a positive or negative attitude towards task shifting and/or independent practice | Students |

| Attitude measures which cannot discriminate between practitioners with a positive, neutral or negative attitude | |

| Attitude measures concerning multiple aspects |

ADHP, advanced dental hygiene practitioner; GDP, general dental practitioner.

Quality assessment

The quality of the cross-sectional surveys was evaluated using the Effective Public Health Practice Project (EPHPP) quality assessment tool for quantitative studies32. The EPHPP tool covers three categories relevant to survey studies: selection bias; study design; and data-collection methods. Each category consists of several questions allowing one of three possible judgements: strong; moderate; or weak. These are summarised in an overall quality score: strong (no ‘weak’ ratings); moderate (one ‘weak’ rating); or weak (two or more ‘weak’ ratings).

Data management and analyses

From each study, the operationalisation of attitude was extracted. Data reflecting attitude were extracted from eligible studies. Then, the percentages of dental and/or dental-hygiene practitioners with moderate to very positive or negative attitudes were retrieved. In addition, country and region, sampling type, response rate, gender distribution of practitioners and sample size were collected. In three studies, only subgroups of dentists or dental hygienists were reported. From these studies, aggregated proportions were calculated.

The proportion of positive or negative attitudes may be influenced by cultural, economic and political climate, causing random variance. For this reason, the random-effects model was used to synthesise possible heterogenous influences; however, those from type of profession and year of publication are statistically tested. A descriptive overview of the results according to forest plots is combined with statistical testing of effects after mixed-model estimation33. The forest plot34 presents the number of respondents (dentists or dental hygienists) answering affirmative (i.e. yes) with regard to a positive or negative attitude towards an extended scope of dental hygiene practice. In addition, the proportion of affirmative replies, with its 95% confidence interval, is given for each study, together with the meta effect of the proportion of positive or negative attitudes estimated from the random-effects model based on each profession. A meta-analysis was performed when at least two studies of each comparison group (dentists and dental hygienists) were available. A funnel plot was used to inspect indication of publication bias. The latter is unlikely when the largest studies are near the average while the results of smaller studies are distributed evenly on both sides of the average. This is also investigated using the regression test for funnel plot asymmetry when at least 10 studies were available for analyses34., 35..

Results

Description of studies

The exploratory literature search regarding synonyms or related terminology of task shifting resulted in the identification of 17 different terms. The following terms were found, besides extended scope of practice and independent practice: advanced hygienist skills36; changing skill mix37., 38.; changing task profiles39; maximised scope of practice40; expanding dental hygiene41; expanded duties42; expanded function12; task division26; expanding the role43; task redistribution44., 45., 46.; expanding the range of procedures47; extended competencies48; task sharing49; task shifting50; task transfer51; work distribution52; and task reallocation53.

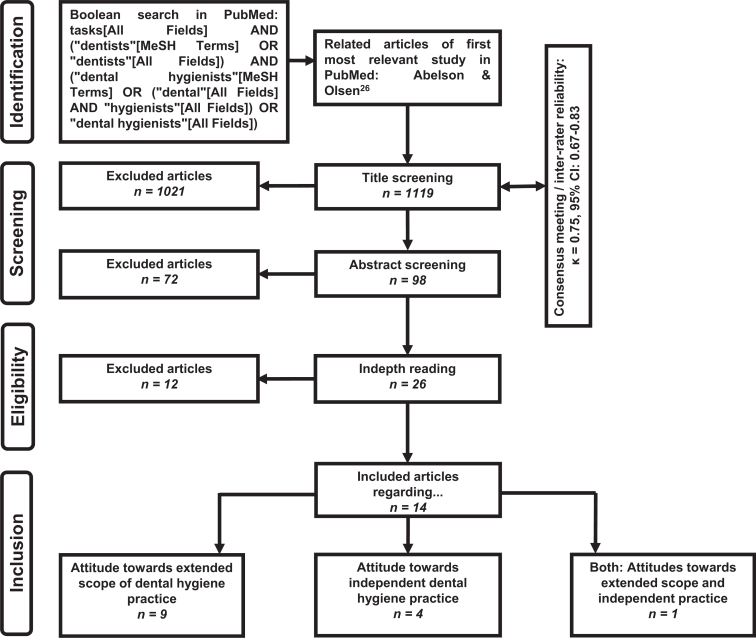

Using the related articles search, 1119 articles were identified in PubMed. The search of AMED and CINAHL found no additional articles. The inter-rater reliability regarding title screening was Cohen's kappa = 0.75 (95% CI: 0.67–0.83). Twenty-six studies were selected by title screening, among which 1424., 25., 26., 42., 54., 55., 56., 57., 58., 59., 60., 61., 62., 63. fulfilled the eligibility criteria (Figure 1). The reasons for excluding studies were as follows: one study only reported practitioners with a very positive attitude; one study reported attitudes towards several specific tasks and not extended scope in general; two studies reported specific motives regarding attitude towards extended scope of practice; in one study, the attitude statement consisted of multiple aspects; two studies described to what degree extended scope of practice was related to productivity; three studies primarily focused on job or career satisfaction related to extended scope of practice; one study concerned attitude of dentists towards dental hygienists in general; and one study focused on attitude towards interdisciplinary collaboration.

Figure 1.

Flow chart of the literature-selection process (Moher et al.64). 95% CI, 95% confidence interval.

The studies included were conducted on five different continents: North America (four from the USA and one from Canada); Africa (two from South Africa); Oceania (two from New Zealand and one from Australia); Europe (Finland, Norway, and the Netherlands); and Asia (Israel; Table 2). The response rate of the studies varied between 29.0% and 87.5%. Eight of the 14 studies reported a response rate higher than 60%. Sample sizes varied between 67 and 4522. Most sample sizes exceeded 300 participants. The oldest study was published in 1985 and the newest study was published in 2013.

Table 2.

Characteristics of studies included in the two meta-analyses regarding a positive attitude towards expanded scope and independent practice of dental hygienists

| Positive attitude towards | Study and country (state or province) | Sample type (size) | Response rate (%) | Gender distribution in sample | Profession | Proportion of practitioners with a positive attitude | Operationalisation of attitude |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % Female | |||||||

| Extended scope | Abelsen & Olsen26, Norway | Random (453) | 45.0 | 39.0 | Dentist | 0.60 | ‘…desirable to delegate’ |

| Random (108) | 42.0 | 99.1 | Dental hygienist | 0.55 | |||

| Ayers et al.55, New Zealand | Population (211) | 73.2 | 95.3 | Dental hygienist | 0.81 | ‘Interested in expanding range of procedures’ | |

| Blue et al.24, USA | Convenience (626) | 76.3 | 19.0 | Dentist | 0.54 | ‘…a positive impact on provision of quality dental care.’ | |

| Gordon & Rayner57, South Africa | Population (439) | 51.0 | Data not available | Dental hygienist | 0.93 | ‘wish to expand on current qualification’ | |

| Hopcraft et al.25, Australia (Victoria) | Random (183) | 64.7 | 15.6 | Dentist | 0.62* | ‘Dental hygienists should be able to increase the scope of practice’ | |

| Random (67) | 77.0 | 95.5 | Dental hygienist | 0.82 | |||

| Lambert et al.59, USA (Colorado, Kentucky and North Carolina) | Stratified (389) | 29.0 | 97.3** | Dental hygienist | 0.89** | ‘Overall level of support for’ extended function dental hygienist | |

| Moffat & Coates60, New Zealand | Random (330) | 66.8 | 30.4 | Dentist | 0.59 | ‘consider employing a dual-trained Oral Health graduate’ | |

| Murtomaa & Haugejorden61, Finland | Random (313) | 85.0 | 65.6 | Dentist | 0.69 | ‘…changes in the tasks performed by Extended Duty Dental Hygienist’ | |

| Sgan-Cohen et al.62, Israel | Convenience (156) | 87.5 | data not available | Dentist | 0.53*** | ‘Expected functions of dental hygienist…’ | |

| Van Wyk et al.42, South Africa | Random (138) | 47.0 | Data not available | Dental hygienist | 0.87 | ‘functions of the oral hygienist should be expanded?’ | |

| Independence | Adams54, Canada (Ontario) | Stratified (391) | 62.0 | 45.5 | Dentist | 0.04 | ‘Dental hygienists should be allowed to practice independently of dentists’ |

| Stratified (383) | 78.0 | 88.0 | Dental hygienists | 0.71 | |||

| Benicewicz & Metzger56, USA | Stratified (4522) | 49.6 | Data not available | Dental hygienist | 0.54 | ‘…dentist's presence in the facility not always be required’ | |

| Hopcraft et al.25, Australia (Victoria) | Random (183) | 64.7 | 15.6 | Dentist | 0.27* | ‘Dental hygienists should be allowed to practice independently’ | |

| Random (67) | 77.0 | 95.5 | Dental hygienist | 0.52 | |||

| Kaldenberg & Smith58, USA (Oregon) | Random (385) | 71.0 | 5.4 | Dentists | 0.10 | ‘I support independent practice for hygienists’ | |

| Van Dam et al.63, the Netherlands | Convenience (304) | 45.9 | 57.2 | Dentist | 0.67 | ‘not afraid that the independent dental hygienist will become competitor of the dentist’ |

The percentages of dentists with a positive attitude towards extended scope of dental hygiene practice are reported in six studies (Table 2). The percentages of dental hygienists were also reported in six studies. The percentages of dentists with a positive attitude towards independent dental-hygiene practice were reported in four studies, and three studies reported percentages of dental hygienists with a positive attitude towards independent dental-hygiene practice.

The percentages of dentists with a negative attitude towards extended scope of dental hygiene practice were reported in three studies (Table 3). The percentages of dental hygienists with a negative attitude towards extended scope of dental hygiene practice were also reported in three studies. The percentages of dentists with a negative attitude towards independent dental-hygiene practice were reported in three studies, and one study reported the percentage of dental hygienists with a negative attitude towards independent dental hygiene practice.

Table 3.

Characteristics of studies included in the two meta-analyses regarding a negative attitude towards expanded scope and independent practice of dental hygienists

| Negative attitude towards | Study and country (state or province) | Sample type (size) | Response rate (%) | Gender distribution in sample | Profession | Proportion of practitioners with a negative attitude | Operationalisation of attitude |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % Female | |||||||

| Extended scope | Abelsen & Olsen26, Norway | Random (453) | 45.0 | 39.0 | Dentist | 0.40 | ‘…desirable to delegate’ |

| Random (108) | 42.0 | 99.1 | Dental hygienist | 0.45 | |||

| Ayers et al.55, New Zealand | Population (211) | 73.2 | 95.3 | Dental hygienist | 0.19 | ‘Interested in expanding range of procedures’ | |

| Moffat & Coates60, New Zealand | Random (330) | 66.8 | 30.4 | Dentist | 0.41 | ‘consider employing a dual-trained Oral Health graduate’ | |

| Murtomaa & Haugejorden61, Finland | Random (313) | 85.0 | 65.6 | Dentist | 0.31 | ‘…changes in the tasks performed by Extended Duty Dental Hygienist’ | |

| Van Wyk et al.42, South Africa | Random (138) | 47.0 | Data not available | Dental hygienist | 0.04 | ‘functions of the oral hygienist should be expanded?’ | |

| Independence | Adams54, Canada (Ontario) | Stratified (391) | 62.0 | 45.5 | Dentist | 0.96 | ‘Dental hygienists should be allowed to practice independently of dentists’ |

| Stratified (383) | 78.0 | 88.0 | Dental hygienists | 0.29 | |||

| Kaldenberg & Smith58, USA (Oregon) | Random (385) | 71.0 | 5.4 | Dentists | 0.82 | ‘I support independent practice for hygienists’ | |

| Van Dam et al.63, the Netherlands | Convenience (304) | 45.9 | 57.2 | Dentist | 0.16 | ‘not afraid that the independent dental hygienist will become competitor of the dentist’ |

Risk of bias among the studies included

Three of 14 studies included were classified as ‘weak’ (Table 4) as a result of non-randomised sampling and potential selection bias.

Table 4.

Quality assessment of included studies

| Study | Selection bias | Study design | Data-collection methods | Global rating |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abelsen & Olsen26 | Moderate | Strong | Strong | Strong |

| Adams54 | Moderate | Strong | Moderate | Strong |

| Ayers et al.55 | Strong | Strong | Strong | Strong |

| Benicewicz & Metzger56 | Moderate | Strong | Moderate | Strong |

| Blue et al.24 | Weak | Weak | Moderate | Weak |

| Gordon & Rayner57 | Moderate | Moderate | Moderate | Strong |

| Hopcraft et al.25 | Moderate | Strong | Moderate | Strong |

| Kaldenberg & Smith58 | Moderate | Strong | Moderate | Strong |

| Lambert et al.59 | Moderate | Strong | Strong | Strong |

| Moffat & Coates60 | Moderate | Strong | Moderate | Strong |

| Murtomaa & Haugejorden61 | Strong | Strong | Moderate | Strong |

| Sgan-Cohen et al.62 | Weak | Weak | Weak | Weak |

| Van Dam et al.63 | Weak | Weak | Weak | Weak |

| Van Wyk et al.42 | Moderate | Strong | Strong | Strong |

Outcomes of studies included

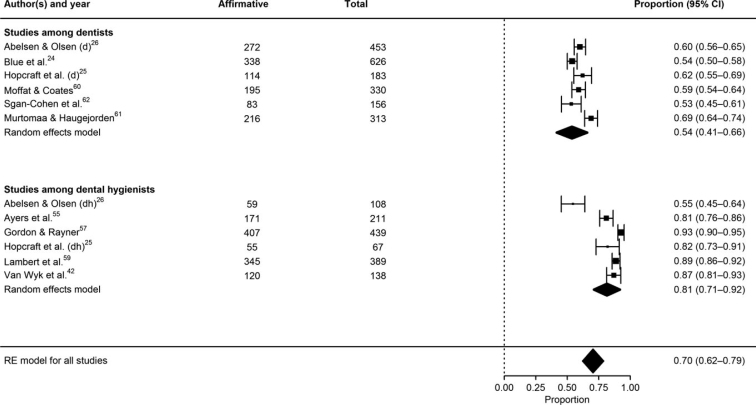

The forest plot from the meta-analysis in Figure 2 provides the number of respondents expressing a positive attitude towards extended scope of dental hygiene practice; the total numbers of dentists and dental hygienists; and the proportions of dentists and dental hygienists and corresponding 95% confidence intervals. All proportions were larger for dental hygienists than for dentists, with the study by Abelsen & Olsen26 as the only exception. The meta proportion for the dentists was 0.54 (95% CI: 0.41–0.66) and for the dental hygienists was 0.81 (95% CI: 0.71–0.92). The Wald statistic33 revealed no evidence for an effect of year of publication (estimate = −0.002, standard error = 0.004, t = −0.494, P = 0.634), and strong evidence65 for the difference in proportions of positive attitudes between the two professions towards extended scope of dental hygiene practice (estimate = −0.230, standard error = 0.063, t = −3.631, P = 0.006).

Figure 2.

Forest plot from the meta-analysis showing the number of respondents in each study expressing a positive attitude towards extended scope of dental hygiene practice (Affirmative), the total numbers of dentists and dental hygienists in each study, and the proportion and 95% confidence interval (95% CI) of the number of respondents in each study with an affirmative response. d, dentists; dh, dental hygienists; RE, random effects.

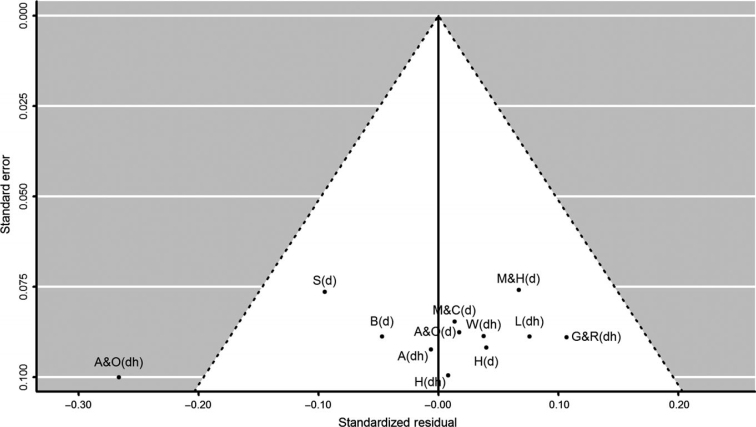

The funnel plot in Figure 3, with the standardised residuals versus standard errors of the mixed model for meta-analysis, revealed the Abelsen & Olsen26 study among dental hygienists as outlying to the left. A further sensitivity analysis indicated this study to be influential according to a studentised residual of −4.381 and a Cooks distance of 1.426. The funnel plot regression test indicated some degree of asymmetry (t = −2.612, d.f. = 8, P = 0.031)35. All studies but one were within the boundaries, thus indicating no publication bias.

Figure 3.

Funnel plot with standardised residuals versus standard errors from meta-analysis of studies on proportions of dentists and dental hygienists with a positive attitude towards extended scope of dental hygiene practice . A; A&O(d) A&O(dh), Abelsen & Olsen26; B, Blue et al.24; G&R, Gordon & Rayner57; H(d) H(dh), Hopcraft et al.25; L, Lambert et al.59; M&C, Moffat & Coates60; M&H, Murtomaa & Haugejorden61; S, Sgan-Cohen et al.62; d, dentists; dh, dental hygienists.

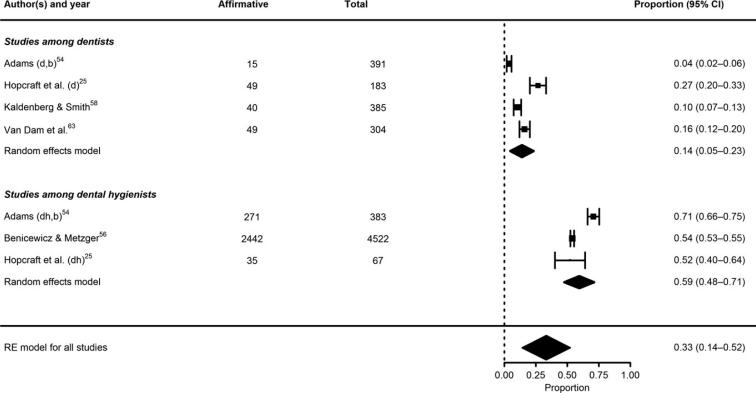

The forest plot from the meta-analysis in Figure 4 provides the number of respondents expressing a positive attitude towards independent dental hygiene practice; the total numbers of dentists and dental hygienists; and the proportion of dentists and dental hygienists and corresponding 95% confidence intervals. All proportions for dental hygienists were larger than those for dentists. The estimated meta proportion for the dentists was 0.14 (95% CI: 0.05–0.23) and for the dental hygienists was 0.59 (95% CI: 0.48–0.71). The Wald statistic33 revealed no evidence for an effect of year of publication (estimate = 0.005, standard error = 0.006, Z = 0.882, P = 0.428), and strong evidence65 for the difference in proportions of positive attitudes between the two professions towards extended scope of dental hygiene practice (estimate = −0.476, standard error = 0.081, Z = −5.860, P = 0.004). Data could not be analysed using a funnel plot because fewer than 10 studies were included77.

Figure 4.

Forest plot from the meta-analysis showing the number of respondents in each study expressing a positive attitude towards independent dental-hygiene practice (Affirmative), the total numbers of dentists and dental hygienists in each study, and the proportion and corresponding 95% confidence interval (95% CI) of the number of respondents in each study with an affirmative response. b, both dentists and dental hygienists; d, dentists; dh, dental hygienists; RE, random effects.

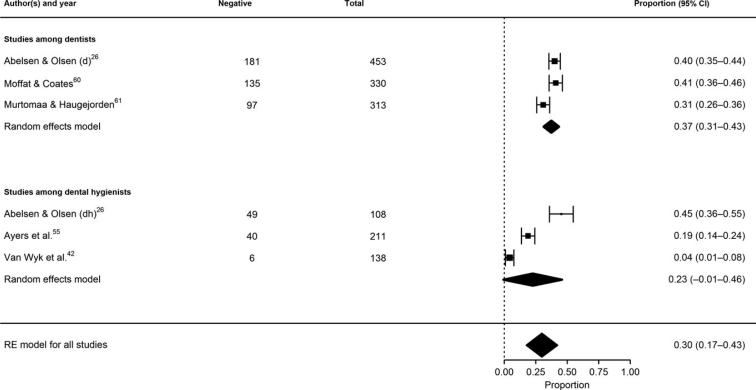

The forest plot from the meta-analysis in Figure 5 provides the number of respondents expressing a negative attitude towards extended scope of dental hygiene practice; the total numbers of dentists and dental hygienists; and the proportion of dentists and dental hygienists and the corresponding 95% confidence intervals. Compared with dentists, the proportions among dental hygienists were more heterogeneous. The meta proportion for the dentists was 0.37 (95% CI: 0.31–0.43) and for the dental hygienists was 0.23 (95% CI: −0.01 to 0.46). The Wald statistic33 revealed no evidence for an effect of year of publication (estimate = 0.008, standard error = 0.007, t = 1.161, P = 0.330), and no evidence65 for the difference in proportions of negative attitudes between the two professions towards extended scope of dental hygiene practice (estimate = 0.166, standard error = 0.118, t = 1.407, P = 0.254). A funnel plot was not constructed because fewer than 10 studies were available66.

Figure 5.

Forest plot from the meta-analysis showing the number of respondents in each study expressing a negative attitude towards extended scope of dental hygiene practice (Negative), the total numbers of dentists and dental hygienists in each study, and the proportion and corresponding 95% confidence interval (95% CI) of the number of respondents in each study with an affirmative response. d, dentists; dh, dental hygienists; RE, random effects.

No forest plot or funnel plot was made for negative attitude towards independent dental-hygiene practice because only three studies among dentists and a single study among dental hygienists were available (Table 3). The majority of dentists from two of three studies held a negative attitude. The study that reported a minority of dentists with a negative attitude originated from the Netherlands. The only study concerning dental hygienists reported a minority of practitioners with a negative attitude.

Discussion

Regarding dentists, we found that a majority have a positive attitude and a minority have a negative attitude towards extended scope of dental hygiene practice. A minority of dentists have a positive attitude towards independent dental-hygiene practice. The analysis of studies included, regarding a negative attitude of dentists towards independent dental hygiene practice, was not conclusive. The different attitudes of dentists towards extended scope and independent dental-hygiene practice can be explained by the following. People in high-status occupations, like dentists, advance by delegating lower-status skills and roles to subordinate groups, such as dental hygienists67., 68.. This could explain why 54% of dentists had a positive attitude towards an extended scope of dental hygiene practice but only 14% had a positive attitude towards independent dental hygiene practice. If dental hygienists became independent, they would no longer be subordinate and the dental profession would lose control over the treatment provided.

Our finding, that a majority of dental hygienists have a positive attitude towards an extended scope of practice, can be explained by the following. The expanded function of the dental hygienist is considered necessary for providing the appropriate dental hygiene care12., 39., for example local anaesthesia12., 14., 15. and dental radiographs69., 70.. Another explanation is the perceived need of dental hygienists for job enrichment. Extended scope of practice may contribute to more skill variety, which increases job satisfaction71. Finally, an extended scope of practice and independent practice can contribute to higher professional status72 and stronger professional identity21.

Possible explanations for the difference between dentists and dental hygienists in attitude are fear of potential economic loss73 and perceived threat to quality of care74, by dentists. Dentists want to maintain control over other oral health care occupations75., 76., and independent dental hygiene practice may reduce this control. As a consequence, dentists may have less influence on billing and, for this reason, are less likely to be in favour of independent dental hygiene practice. Furthermore, independent dental hygiene practice enables dental hygienists to practice without supervison; some dentists have doubts about the competence of dental hygienists54 and some dental hygienists do not feel confident enough to practice independently77.

Even though this study has limitations, it also has some clear strengths. Attitude towards extended scope or independent practice did not depend on year of publication. In addition, the findings regard studies across various countries. Eleven studies of the 14 included were of high quality. The outcomes of the three low-quality studies did not deviate from the other studies in the forest plots. Finally, with the Abelsen and Olsen study26 as the only exception, no publication bias was found with regard to studies concerning extended scope and independent practice. A weakness of the present study was the relatively small number of studies found to be suitable for inclusion. A potential explanation for this is the heterogenous terminology in use for extended scope of practice, making identification of relevant studies more difficult. However, because the related articles search function was used, it is very likely that all relevant studies were detected. According to Chang et al.28, a related articles search yielded considerably more publications compared with a Boolean search. Another weakness is that a regression test for funnel plot asymmetry concerning independent practice could not be applied because only seven studies were available. The same applies for studies reporting negative attitudes towards extended scope and independent practice. In these analyses, only six and four studies were included, respectively. For conclusiveness it has been recommended not to use the funnel plot asymmetry test when fewer than 10 studies are available66. However, this recommendation is based not only on the number of included studies but also on the heterogeneity in meta-analysis. The test performance for funnel plot asymmetry is somewhat poor, with a small number of studies and a large heterogeneity in meta-analysis78.

Several factors could influence the attitudes of dentists and dental hygienists. Variations in legislation is one variable that might explain different attitudes. However, the study of Lambert59 was conducted in three different American states with varying supervision levels: direct (dentist off-site); collaborative (dentist on-site and off-site); and independent. In this study no significant differences with regard to supervision level and attitude could be found. The authors explicitly mentioned the general response rate of 29% as a possible explanation for not finding significant differences.

Legislation in some countries, such as Australia, Canada, Switzerland and the USA, is multi-jurisdictional and has a regional basis79. Of the studies included, data on independent dental hygiene practice were reported by three on a regional level: Australia (Victoria); Canada (Ontario); and USA (Oregon). Dental hygienists were not allowed to practice independently at the time of publication. However, dental hygienists were allowed to perform independent practice during the publication of a Dutch study. The Dutch study reported a much higher proportion of dentists with a positive attitude towards independent dental hygiene practice compared with the other studies. In addition, in the Canadian study, dentists who employed a dental hygienist held more positive attitudes towards independent dental hygiene practice compared with non-employers. Dentists who oppose independent dental hygiene practice from the Victoria, Ontario and Oregon studies argued that dental hygienists lack training or knowledge to practice independently from the dentist. It seems that the experience of working with dental hygienists might explain these attitudinal differences. Unfortunately, the number of studies is too small to perform a separate meta-analysis.

More studies reported percentages of practitioners with positive attitudes related to two types of task shifting compared with negative attitudes. This could introduce a bias. Ten of the fourteen studies included measured negative attitudes, of which eight studies actually reported these attitudes. More specifically, with regard to extended scope of dental hygiene practice, three studies provided data on negative attitudes of dentists and three studies provided data on negative attitudes of dental hygienists. Outcomes regarding negative attitudes of dental hygienists were rather heterogeneous; the outcomes regarding negative attitudes of dentists were homogeneous. The latter confirms that the majority of dentists are not opposed to an extended scope of dental hygiene practice. However, not enough studies regarding negative attitudes towards independent practice were available for a thorough meta-analysis. The heterogeneity of study outcomes within the group of dental hygienists with regard to a negative attitude towards extended scope of practice could be explained by disunity of their profession. This emerging profession consists of different generations of dental hygienists with different qualifications and privileges owing to changes in policy and regulations in a relatively short period of time2. Dentistry is a much older occupation and has a well-established professional status80. The latter is reflected by the more homogenous outcomes of studies regarding attitudes of dentists towards task shifting.

Many variables could have influenced attitudes towards extended scope of practice and independent practice, such as different ratios of dentists and dental hygienists in each country, attitude related to specific tasks, position and maturity of profession. With regard to the ratio of these two professions: in the USA the ratio is almost equal81; whereas the number of dental hygienists in New Zealand are clearly in a minority compared with the number of dentists82. However, the proportions of dentists with a positive attitude towards extended scope of dental hygiene practice are very similar in these two countries24., 60.. Whether the same applies to the dental hygienists of these two countries is not known. With regard to the reasons related to specific tasks, some dental tasks are perceived by dental hygienists as important to their professional role83. Because of the limited information that is available on the attitude of practitioners with regard to specific tasks, more research is needed in this matter. In addition, motives in favour of and against task shifting should be identified. Social position might also influence attitudes. Some dentists still perceive dental hygienists as a dental auxiliary20. However, little is known about the social and psychological implications of task shifting and independent practice84., 85.. Another factor that may influence attitudes in this study is maturity of the dental hygiene profession, as this is different between countries. More specifically, the first year of legislation of practice in the USA was 1917, in Canada 1952, in South Africa 1969, in Australia and Finland 1972, in the Netherlands 1974, in Israel 1978, in Norway 1979 and in New Zealand 198886., 87.. However, there seems to be no relationship between professional maturity and the proportion of practitioners with a positive attitude. For example, dentists in the USA and in Israel are similar with regard to a positive attitude towards extended scope of dental hygiene practice and to Australian and New Zealand dental hygienists with regard to independent dental hygiene practice.

Conclusion

Dentists and dental hygienists differ in their attitude towards extended scope of dental hygiene practice but differ mostly with regard to independent dental hygiene practice. Positive attitudes are present in a majority of dentists, as well as dental hygienists, with regard to extended scope of dental hygiene practice, and for independent dental hygiene practice this holds for a minority of dentists and a majority of dental hygienists.

Acknowledgements

In carrying out this study, the authors would like to thank Letty Hartman, Senior Librarian of the Hanzemediatheek from the Hanze University of Applied Sciences, for her expertise and support regarding the retrieval of literature for the meta-analyses. We also like to show our gratitude for the financial support provided by Hanze University of Applied Sciences PhD Fund, School of Dentistry (University of Groningen), and the Center for Dentistry and Oral Hygiene, University Medical Center Groningen.

Competing interests statement

None declared.

References

- 1.Fones AC. 4th ed. Leas & Febiger; Philadelphia (PA): 1934. Mouth Hygiene; p. 248. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Johnson PM. International profiles of dental hygiene 1987 to 2006: a 21-nation comparative study. Int Dent J. 2009;59:63–77. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.van der Heuvel J, Jongbloed-Zoet C, Eaton K. The new style dental hygienist – changing oral health care professions in the Netherlands. Dent Health. 2006;44:3–10. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jongbloed-Zoet C, Bol-van den Hil EM, La Rivière-Ilsen J, et al. Dental hygienists in The Netherlands: the past, present and future. Int J Dent Hyg. 2012;10:148–154. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-5037.2012.00573.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.The Benefits of Dental Hygiene-Based Oral Health Provider Models. 1 Jan 2016.

- 6.Professional Profile and Competences of Dental Hygienists in Europe, EDHF resolution, adopted by the EDHF General Assembly on 12 September 2015.

- 7.General Dental Council of the United Kingdom: Scope of Practice for Dentists, Clinical dental technicians, Dental therapists, Dental hygienists, Orthodontic therapists, Dental nurses (effective from 30 September 2013).

- 8.National Board of Health and Welfare, Sweden: Competence Description for Registered Dental Hygienist, Article No. 2005-105-1 (effective from 2 October 2005).

- 9.Ministry of Health, Welfare and Sports of The Netherlands: Bulletin of Acts, Orders and Decrees of the Kingdom of the Netherlands, Volume 2006 nr. 147 (effective from 21 February 2006).

- 10.Council of European Dentists (CED) and the Association of Dental Education in Europe (ADEE): Competences of Dental Practitioners, CED-DOC-2013-030-E (effective from 6 June 2014).

- 11.Harris RV, Sun N. Dental practitioner concepts of efficiency related to the use of dental therapists. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2012;40:247–256. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0528.2012.00670.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.DeAngelis S, Goral V. Utilization of local anesthesia by Arkansas dental hygienists, and dentists' delegation/satisfaction relative to this function. Int J Dent Hyg. 2000;74:196–204. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fortner HS. A CDT code for hygienists. RDH. 2008;28:28–33. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lobene R. Harvard University Press; Massachusetts: 1979. The Forsyth Experiment; pp. 86–89. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sisty LePeau N, Nielson Thompson N, Lutjen D. Use, need and desire for pain control procedures by Iowa hygienists. J Dent Hyg. 1992;66:137–146. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Edgington E, Pimlott J. Public attitudes of independent dental hygiene practice. J Dent Hyg. 2000;74:261–270. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Eagly AH, Chaiken S. Harcourt Brace Jovanovich; Fort Worth, TX: 1999. The Psychology of Attitudes. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Macdonald KM. Sage; London: 1999. The Sociology of the Professions. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Plager KA, Conger MM. Advanced practice nursing: constraints to role fulfillment. IJANP. 2007;9:1–7. Available from: https://ispub.com/IJANP/9/1/3418 Accessed 19 May 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Swanson Jaecks KM. Current perceptions of the role of dental hygienists in interdisciplinary collaboration. J Dent Hyg. 2009;83:84–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tajfel H, Turner JC. Social comparison and group interest in ingroup favouritism. Eur J Soc Psychol. 1979;9:187–204. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Brewer MB. In: Handbook of Self and Identity. Leary MR, Tangey JP, editors. Guilford Press; New York, NY: 2003. Optimal distinctiveness, social Identity, and the self; pp. 480–491. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Adams TL. Inter-professional conflict and professionalization: dentistry and dental hygiene in Ontario. Soc Sci Med. 2004;58:2243–2252. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2003.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Blue CM, Funkhouser DE, Riggs S, et al. Utilization of nondentist providers and attitudes toward new provider models: findings from the National Dental Practice-Based Research Network. J Public Health Dent. 2013;73:237–244. doi: 10.1111/jphd.12020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hopcraft M, McNally C, Ng C, et al. Attitudes of the Victorian oral health workforce to the employment and scope of practice of dental hygienists. Aust Dent J. 2008;53:67–73. doi: 10.1111/j.1834-7819.2007.00012.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Abelsen B, Olsen JA. Task division between dentists and dental hygienists in Norway. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2008;36:558–566. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0528.2008.00426.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Oxford Dictionaries. Oxford Dictionaries Online. Oxford University Press. Accessed 2 April 2015.

- 28.Chang AA, Heskett KM, Davidson TM. Searching the literature using medical subject headings versus text word with PubMed. Laryngoscope. 2006;116:336–340. doi: 10.1097/01.mlg.0000195371.72887.a2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lin J, Wilbur WJ. PubMed related articles: a probabilistic topic-based model for content similarity. BMC Bioinformatics. 2007;8:423. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-8-423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cohen J. A coefficient of agreement for nominal scales. Educ Psychol Meas. 1960;20:37–46. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fleiss JL. 2nd ed. John Wiley & Sons; New York: 1981. Statistical Methods for Rates and Proportions; pp. 38–46. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Thomas BH, Ciliska D, Dobbins M, et al. A process for systematically reviewing the literature: providing the research evidence for public health nursing interventions. Worldviews Evid Based Nurs. 2004;1:176–184. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-475X.2004.04006.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Knapp G, Hartung J. Improved tests for a random effects meta-regression with a single covariate. Stat Med. 2003;22:2693–2710. doi: 10.1002/sim.1482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Viechtbauer W. Conducting meta-analyses in R with the metafor package. J Stat Softw. 2010;36:1–48. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Harbord RM, Egger M, Sterne JAC. A modified test for small-study effects in meta-analyses of controlled trials with binary endpoints. Stat Med. 2006;25:3443–3457. doi: 10.1002/sim.2380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Brian J, Cooper MD. Utilization of advanced hygienist skills in the private practice. J Indiana Dent Assoc. 1997;76:13–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Buchan J, Ball J, O'May F. If changing skill mix is the answer, what is the question? J Health Serv Res Policy. 2001;6:235–236. doi: 10.1258/1355819011927549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Falcon H. Summary of: modelling workforce skill-mix: how can dental professionals meet the needs and demands of older people in England? Br Dent J. 2010;208:116–117. doi: 10.1038/sj.bdj.2010.132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Petrén V, Levin G, Chohan T, et al. Swedish dental hygienists' preferences for workplace improvement and continuing professional development. Int J Dent Hyg. 2005;3:117–125. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-5037.2005.00138.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Christensen GJ. Increasing patient service by effective use of dental hygienists. J Am Dent Assoc. 1995;126:1291–1294. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.1995.0366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nash DA. Expanding dental hygiene to include dental therapy: improving access to care for children. J Dent Hyg. 2009;83:36–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Van Wyk CW, Toogood S, Scholtz L, et al. South African oral hygienists: their profile and perception of their profession and career. SADJ. 1998;53:537–546. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bernie KM. Advantages of expanding the role of the registered dental hygienist in tooth whitening. Dent Today. 2001;20:56–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.The Haworth Press; New York: 2003. Allied Health: Practice Issues and Trends in the New Millennium. Lecca PJ, Valentine P, Lyons KJ, editors. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Jerković-Ćosić K, van Offenbeek MA, van der Schans CP. Job satisfaction and job content in Dutch dental hygienists. Int J Dent Hyg. 2012;10:155–162. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-5037.2012.00567.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bruers JJ, van Rossum GM, Felling AJ, et al. Business orientation and willingsness to distribute dental tasks of Dutch dentists. Int Dent J. 2003;53:255–263. doi: 10.1111/j.1875-595x.2003.tb00754.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ayers KMS, Thomson WM, Rich AM, et al. Gender differences in dentists' working practices and job satisfaction. J Dent. 2008;36:343–350. doi: 10.1016/j.jdent.2008.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Corbey-Verheggen MJ. Oral hygienist with extended competencies. Ned Tijdschr Tandheelkd. 2001;108:323–325. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Widström E, Eaton KA, Luciak-Donsberger C. Changes in dentist and dental hygienist numbers in the European Union and Economic Area. Int Dent J. 2010;60:311–316. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.WHO (World Health Organisation) World Health Organization; Geneva: 2006. The World Health Report 2006 - Working Together for Health. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kidd MR, Watts IT, Mitchell CD, et al. Principles for supporting task substitution in Australian general practice. Med J Aust. 2006;185:20–22. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2006.tb00443.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wang Q. Working conflicts of nurses in hospital. CJN. 2000;35:732–734. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Nash DA, Friedman JW, Kavita R, et al. W.K. Kellogg Foundation; Michigan: 2012. A Review of the Global Literature on Dental Therapists. In the Context of the Movement to Add Dental Therapists to the Oral Health Workforce in the United States. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Adams TL. Attitudes to independent dental hygiene practice: dentists and dental hygienists in Ontario. J Can Dent Assoc. 2004;70:535–538. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ayers K, Meldrum AM, Thomson WM, et al. The working practices and job satisfaction of dental dygienists in New Zealand. J Public Health Dent. 2006;66:186–191. doi: 10.1111/j.1752-7325.2006.tb02578.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Benicewicz D, Metzger C. Supervision and practice of dental hygienists: report of ADHA survey. J Dent Hyg. 1989;63:173–180. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Gordon NA, Rayner CA. A national survey of oral hygienists in South Africa. SADJ. 2004;59:184. 186-188. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kaldenberg DO, Smith JC. The independent practice of dental hygiene: a study of dentists' attitudes. Gen Dent. 1990;38:268–271. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Lambert D, George M, Curran A, et al. Practicing dental hygienists' attitudes toward the proposed advanced dental hygiene practitioner: a pilot study. J Dent Hyg. 2009;83:117–125. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Moffat S, Coates D. Attitudes of New Zealand dentists, dental specialists and dental students towards employing dual-trained Oral Health graduates. Br Dent J. 2011;211:E16. doi: 10.1038/sj.bdj.2011.870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Murtomaa H, Haugejorden O. Finnish dentists' attitudes towards, and experience of, expanded-duty dental hygienists. Community Dent Health. 1987;4:143–150. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Sgan-Cohen HD, Mann J, Greene JJ. Expected functions of dental hygienists in Jerusalem. Perceptions of dentists and dental hygiene students. Dent Hyg (Chic) 1985;59:558–562. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Van Dam BA, den Boer JC, Bruers JJ. Recently graduated dentists: working situation and future plans. Ned Tijdschr Tandheelkd. 2009;116:499–506. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, et al. The PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. J Clin Epidemiol. 2009;62:1006–1012. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2009.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Sellke T, Bayarri MJ, Berger JO. Calibration of p values for testing precise null hypotheses. Am Stat. 2001;55:62–71. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Sterne J, Egger M, Moher D. In: Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. Version 5.0.0. Higgins J, Green S, editors. Cochrane Collaboration; Oxford: 2008. Addressing reporting biases. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Kronus CL. The evolution of occupational power. Sociol Work Occup. 1976;3:3–37. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Larkin GV. Tavistock; London: 1983. Occupational Monopoly and Modern Medicine. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Jansson L, Lavstedt S, Zimmerman M. Prediction of marginal bone loss and tooth loss–a prospective study over 20 years. J Clin Periodontol. 2000;29:672–678. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-051x.2002.290802.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Laurell L, Romao C, Hugoson A. Longitudinal study on the distribution of proximal sites showing significant bone loss. J Clin Periodontol. 2003;30:346–352. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-051x.2003.00298.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Hackman JR, Oldham GR. Addison-Wesley; Reading, MA: 1980. Work Redesign. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Omark RC. Training therapy of psychotherapists: professional socialization as interprofessional relations. Psychol Rep. 1978;42:1307–1310. doi: 10.2466/pr0.1978.42.3c.1307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Freidson E. 9th World Congress of Sociology; Uppsala, Sweden: 1978. The official Construction of Occupations: An Essay on the Practical Epistemology of Work. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Ross MK, Ibbetson RJ, Turner S. The acceptability of dually-qualified dental hygienist-therapists to general dental practitioners in South-East Scotland. Br Dent J. 2007;202:E8. doi: 10.1038/bdj.2007.45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Adams T. Dentistry and medical dominance. Soc Sci Med. 1999;48:407–420. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(98)00316-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Cotton F. Quality control, or just control? J Dent Hyg. 1990;64:320–322. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Virtanen JI, Tseveenjav B, Wang NJ, et al. Nordic dental hygienists' willingness to perform new treatment measures: barriers and facilitators they encounter. Scand J Caring Sci. 2011;25:311–316. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-6712.2010.00828.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Ioannidis JPA, Trikalinos TA. The appropriateness of asymmetry tests for publication bias in meta-analyses: a large survey. CMAJ. 2007;176:1091–1096. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.060410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Johnson PM. PMJ Consultants; Toronto: 2007. International Profiles of Dental Hygiene 1987 to 2006: A 21-nation Comparative Study. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Morison S, Marley J, Stevenson M, et al. Preparing for the dental team: investigating the views of dental and dental care professional students. Eur J Dent Educ. 2008;12:23–28. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0579.2007.00487.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Yamalik N, Ensaldo-Carrasco E, Cavalle E, et al. Oral health workforce planning part 2: figures, determinants and trends in a sample of World Dental Federation member countries. Int Dent J. 2014;64:117–126. doi: 10.1111/idj.12117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Dental Council New Zealand, www.dcnz.org.nz. Accessed 13 October 2015.

- 83.Petrén V, Levin G, Chohan T, et al. Swedish dental hygienists' preferences for workplace improvement and continuing professional development. Int J Dent Hyg. 2005;3:117–125. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-5037.2005.00138.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.McKeown L, Sunell S, Wickstrom P. The discourse of dental hygiene practice in Canada. Int J Dent Hyg. 2003;1:43–48. doi: 10.1034/j.1601-5037.2003.00006.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Gillis MV. Local anesthesia delivery by dental hygienists: an essential component of contemporary practice. JPH. 2000;9:19–22. [Google Scholar]

- 86.Coates DE, Kardos TB, Moffat SM, et al. Dental therapists and dental hygienists educated for the New Zealand environment. J Dent Educ. 2009;73:1001–1008. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Danner V. Looking back at 75 years of the journal: former editors reflect on their time with the journal. J Dent Hyg. 2002;76:10–13. [Google Scholar]