Abstract

Recent empirical evidence has documented that US middle-aged adults today are reporting lower mental and physical health than same-aged peers several decades ago. Individuals who attained fewer years of education have been most vulnerable to these historical changes. One overarching question is whether this phenomenon is confined to the US or whether it is transpiring across other high-income and upper-middle-income nations. To examine this question, we use nationally representative longitudinal panel data from five nations across different continents and cultural backgrounds (US, Australia, Germany, South Korea, and Mexico). Results revealed historical improvements in physical health for people in their 40s and early 50s across all five nations. Conversely, the direction of historical change in mental health vastly differed across nations. Later-born cohorts of US middle-aged adults exhibit worsening mental health and cognition. Australian middle-aged adults also experienced worsening mental health with historical time. In contrast, historical improvements for mental health were observed in Germany, South Korea, and Mexico. For US middle-aged adults, the protective effect of education diminished in later-born cohorts. Consistent across the other nations, individuals with fewer years of education were most vulnerable to historical declines or benefitted the least from historical improvements. We discuss potential reasons underlying similarities and differences between the US and other nations in these historical trends and consider the role of education.

Keywords: Culture Change, Adult Development, Socioeconomic Differences, Cohort Effects, Growth Curve Modeling, Cross-Cultural Research

The narrative surrounding midlife health and well-being in the US has come to the public forefront in the last 5 years and has revealed disturbing trends. Case and Deaton (2015) initially observed a rise in what they called deaths of despair amongst White non-Hispanic men and women aged 45–54 in the US who solely attained a high school education. Although this research has garnered a good deal of attention, the findings pale in comparison to the health inequities that have long existed based on gender, race, and social class across the adult lifespan, particularly in midlife (Muening et al., 2018; Roux, 2017). Recent evidence documents that following the Great Recession, middle-aged adults today exhibit more daily stress, chronic illnesses, functional limitations, and lower psychological well-being than same-aged peers in earlier historical times (Almeida et al., 2020; Kirsch et al, 2019). This research suggests that current cohorts of US middle-aged adults are doing more poorly than earlier-born cohorts and revealed that low to middle-socioeconomic status (SES) individuals are disproportionally impacted.

Our objective is to put these results in a larger perspective by directly comparing the nature of such disparities in the US with other high-income and upper-middle-income nations from different continents and cultural backgrounds (Australia, Germany, South Korea, and Mexico). Such a direct comparative approach that involves nationally representative longitudinal panel data also allows for identifying possibly disadvantaged midlife population segments within and across nations who are either most vulnerable to historical declines or benefitted the least from historical improvements. We also consider the role of years of education, which offers insights into sociocultural dynamics (Cohen & Varnum, 2016; Varnum & Grossmann, 2017).

Historical Embeddedness and Cultural Significance of Midlife in the US

Lifespan developmental psychology has long postulated that historical embeddedness and cultural contextualism influence developmental processes across the adult lifespan (Baltes, 1987; Wahl & Gerstorf, 2018). This framework proposes that historical-cultural conditions, markedly influenced by events, norms, and processes existing in a given historical period and how these evolve over time have important implications for shaping development (Baltes et al., 1998). Examining the effects of historical-cultural conditions is typically done by studying similarities and differences across persons based on their cohort or year of birth. A majority of research using this approach has focused on older adults aged 65 and older; a recent review by Gerstorf and colleagues (2020) concluded that older adults are getting younger or performing better than previous cohorts across mental and physical health and psychosocial indices. An area that has received much less attention is the extent to which middle-aged adults are doing better or more poorly compared to same-aged peers over historical time. Midlife is commonly referred to the period in the lifespan when individuals are aged 40 to 65 (Lachman, 2004) and regarded as a vibrant and pivotal period (Infurna et al., 2020; Lachman et al., 2015). Lifespan developmental psychology argues that development is a cumulative, lifelong process and studying cohort differences in midlife can help foreshadow the state of functioning for tomorrow’s older adults.

Cultural significance of midlife.

Middle-aged adults form the backbone of society. They carry much of the societal load through constituting most of the workforce, while simultaneously bridging the younger and older generations in the family through caregiving-related duties (Infurna et al., 2020; Lachman et al., 2015). Given the changing demographics of decreases in the number of children being born and the increasing number of older people, middle-aged adults are more relevant than ever before as a significant resource for families and society (Feinberg, 2018). Midlife is also a period in the lifespan where pertinent domains, such as mental and physical health undergo significant changes. Physical functioning typically begins to show decline and the onset of chronic illnesses arise, such as high blood pressure, cancer and arthritis (Lachman, 2004). Crystallized cognitive abilities, on average, are high and stable, but fluid abilities show initial decrements in midlife (Baltes et al., 1998). Focusing on mental health and well-being, there are conflicting reports with research showing depression and distress highest and well-being lowest in midlife (Blanchflower & Oswald, 2020), whereas others find that well-being increases during adulthood or is relatively stable (Galambos et al., 2020). The significance of midlife is further exemplified by empirical evidence demonstrating across nations that better health in midlife–as indexed by health-promoting behaviors (e.g., physical activity) and physiology (e.g., blood pressure)–foreshadows better health in old age (Laurner et al., 1995). These findings not only highlight the importance of examining changes in mental and physical health in midlife, but also call for giving more attention to how they evolve over historical time by comparing trends across cohorts and nations.

Changing expectations in midlife.

The very nature and expectations surrounding midlife is shifting in the context of changes in the timetables of younger adults and longevity of older adults and historical changes seen in social, cultural, and economic life arenas within- and across nations. Infurna and colleagues (2020) discuss two core challenges that middle-aged adults are confronting more than ever before: the changing nature of intergenerational dynamics (i.e., raising children, caregiving for aging parents/in-laws, and custodial grandparenting) and financial vulnerabilities. These cultural processes of shifting demands, expectations, and values placed on middle-aged adults have the potential to exert its toll on mental and physical health. For example, US middle-aged adults are confronting more parenting pressures than ever before (Ebbert et al., 2019), as well as having to (re)launch adult children due to a historically challenging labor market that has led to record numbers of young adults moving back home with their middle-aged parents (Feinberg, 2018). A direct impact of gains in life expectancy for middle-aged adults is having to take on more caregiving-related duties for their aging parents and other relatives, while continuing with full-time work (Reinhard et al., 2019). Increasing caregiving responsibilities across generations are transpiring while having to simultaneously contend with a shrinking social and healthcare safety net; such safety nets come in the form of few options of paid family leave and less comprehensive and accessible healthcare coverage that strains household budgets (Feinberg, 2018). US middle-aged adults are confronting financial vulnerabilities in the form of labor market volatility (stagnant wages and re-configuring one’s job or unemployment) and reduced strength of workplace social ties (Case & Deaton, 2020). The re-structuring of corporate America has led to less investment in employee development and a destabilization of unions giving employees less power and input (Case & Deaton, 2020).

Historical Trends of Mental and Physical Health in Midlife Within- and Between-Nations

There are likely to be cross-national variations in the pressures put on middle-aged adults, which could result in similarities and differences in the extent to which midlife mental and physical health is changing across cohorts within- and between-nations. For example, compared to the US, middle-aged adults living in other nations may be less likely to suffer from depression because of differences in the frequency of multigenerational households and expectations surrounding caregiving for raising children and contributing to the care of aging family members (Johnson & Wiener, 2006). The nature and type of government programs pertaining to family leave and healthcare drastically differ across the nations included. In the US, there is no federally mandated program for paid family leave (e.g., adoption, having children, caregiving for a spouse/partner or parent); such limitations greatly strain financial, mental and physical health (Infurna et al., 2020). This contrasts with nations that have extensive programs (e.g., Germany) where parents can take up to a year and more of paid parental leave, in addition to subsidized childcare. Although the US has the Federal Family and Medical Leave Act, which provides unpaid time off for family leave, only eight states in the US have extended paid family leave policies specifically for caregiving for an adult relative (Reinhard et al., 2019). People who are responsible for an aging loved one are often in midlife and working; therefore, they are at major risk for economic insecurity and declines in mental and physical health, along with reduced hours at work and having to change jobs or decide between caregiving and work(Feinberg,2018).

Historical advancements in healthcare and life expectancy are not universally experienced across low-, middle-, and high-income countries. The US spends more than any other nation on healthcare, but this has not translated into longer and healthier lives (Woolf & Aron, 2013). Rising healthcare costs and out-of-pocket spending in the US are leading to disruptions to medical care, substantial debt, and the threatening of household budgets (Grande et al., 2013). Conversely, nations that operate a universal healthcare system have experienced steady increases in life expectancy, whereas the US has been stagnant/declining (Olshansky et al.,2012). Stronger social safety nets in European nations helped buffer middle-aged adults from negative health effects from the Great Recession (Margerison-Zilko et al., 2016). Access to family care and an obligatory healthcare system may provide middle-aged adults with resources that buffer the frequent strains they are confronted with; research has documented that a lack of social policy pertaining to family leave and healthcare are linked to poorer well-being among parents and earlier deaths in the US (Beckfield & Bambra, 2016; Glass et al., 2016).

Historical trends of midlife mental and physical health in the US.

Historical changes in intergenerational relationships, coupled with more job and financial insecurities have made middle-aged adults more vulnerable to mental and physical health declines (Forbes & Krueger, 2019). The challenges confronting US middle-aged adults has coincided with historical shifts in their mental and physical health. In addition to rising rates of deaths of despair, prevalence rates of disability and metabolic disease in midlife have increased (Chen & Soan, 2015). Studies have documented increasing mental distress over historical time in middle-aged adults (Blanchflower & Oswald, 2020). Yet there is controversy about these patterns. For example, some have found that depressed affect is lowest in midlife (Sutin et al., 2013) and others have found that well-being remains relatively high and stable across adulthood (Galambos et al., 2020). Therefore, a lot remains to be understood regarding the variations that take place in midlife mental and physical health and whether patterns are consistent across cohorts and nations.

Cross-national comparisons of midlife mental and physical health.

Empirical evidence showing historical declines in midlife mental and physical health has primarily been found in US samples. The limited literature on cross-national comparisons suggests that the health of US middle-aged adults is lagging behind other nations. Research comparing midlife adults in the US and England using 2002 data found US middle-aged adults reported more chronic illnesses, and this pattern extended to biological markers of disease (Banks et al., 2006). Research using cross-sectional data from 2012 showed that US middle-aged adults exhibit higher rates of disability and chronic illness than same-aged peers in European and Asian nations (Lee et al., 2018). Limitations of findings include its cross-sectional nature and focus on only physical health. Our study will address these limitations by examining within-person longitudinal change in cohort differences on mental and physical health across five countries, with findings distinguishing universal trends vs those idiosyncratic to particular countries. We will additionally examine mental health to help evaluate whether trends are historically increasing, decreasing, or remaining stable across key outcomes of midlife.

Empirical approach to testing cohort differences in midlife mental and physical health within- and between-nations.

Lifespan developmental psychology discusses how development is profoundly shaped and co-regulated by the cultural and subcultural characteristics of the nation people are living in (Baltes, 1987). We seek to examine to what extent historical trends in declining midlife mental and physical health are confined to the US or transpiring in other countries around the globe. To do so, we examine historical trends in midlife mental and physical health from a US sample and Australia, Germany, South Korea, and Mexico. We chose these countries and panel surveys because they represent different continents, encompass different cultural backgrounds and perspectives (i.e., East vs. West vs. variations in ethnicity, i.e., Asian, Hispanic, and SES heterogeneity), have similarities and differences in government programs pertaining to family leave and healthcare, as well as differ in economic development by including countries that are considered high-income (US, Australia, Germany, and South Korea), as well as upper-middle-income (Mexico; see UN, 2020). Furthermore, the included nations and panel surveys allowed comparison in historical trends across nations because of similar types of mental and physical health outcomes being collected around a common time frame (early 2000s to present day).

Historical Change in Midlife Mental and Physical Health: Variations by Education

Researchers have emphasized that there are many different forms of culture beyond the operationalization of cross-national comparisons (i.e., East vs. West, nationality, and race/ethnicity). Following this tradition, in addition to comparing country-level results, we also conceptualize culture as differences by SES (educational attainment) within each nation (see Cohen & Varnum, 2016; Stephens et al., 2014). Stephens and colleagues (2014) discuss how social class is considered a subculture within a broader culture (i.e., nation) because of the socializing contexts of home, school, and workplace, each of which have downstream effects on inequalities and disparities. This is also consistent with and extends the view from Varnum and Grossman (2017) in that culture is defined as “a shared set of ideas, norms, and behaviors common to a group of people inhabiting a geographic location” such that there is also within-group variation in a geographic location that is in part structured by socioeconomic factors. For example, in the US, empirical evidence has long shown disparities in physical health across SES (Adler et al., 1994), whereas other nations do not show such disparities (Miyamoto et al., 2018). We consider this approach important because the effects of SES and the amount of heterogeneity in SES may vary across nations (e.g., SES may be less important in some cultures than in others). This suggests that educational attainment may be a key factor in understanding how cultures change over time. A consistent and striking finding across the studies that have found a worsening of midlife mental and physical health among later-born cohorts in the US is that such trends occur at a more rapid pace among those with fewer years of education (see Kirsch et al., 2019). Put differently, having more education, to a certain extent, is a protective factor against historical trends of declining mental and physical health among US middle-aged adults. One potential explanation for this is there is a premium that comes with more education, such as the availability of better jobs that are less physically demanding, more job security and higher pay, as well as greater accessibility to affordable healthcare (Case & Deaton, 2020).

The Present Study

The objective of the present study is to examine whether the worsening of middle-aged adults’ mental and physical health is confined to the US or whether it is transpiring in similar ways across other high- and upper-middle-income nations. We also empirically test whether these historical trends are generalizable across levels of educational attainment within nations. Using historical change as a lens constitutes a tool that helps us identify how and why gaps between population segments currently exist, and whether they have been narrowing or widening over the past decades. Evidence of worsening of US midlife mental and physical health has used cross-sectional data that compares functioning between cohorts within datasets, such as MIDUS data from 1995 and 2012 (Kirsch et al., 2019). Moving ahead, we use longitudinal data that permits the examination of within-person change and how this may have been shaped by the historical times people are living in (see Galambos et al., 2020). To do so, we utilize longitudinal panel data from nationally representative datasets in the US, Australia, Germany, South Korea, and Mexico. By comparing findings across nations with similarities and differences across cultural backgrounds and perspectives, government programs pertaining to family leave and healthcare, and economic development/policy, we are positioned to provide comparisons in and identify the nature of historical trends or cohort differences in the mental and physical health of middle-aged adults. This can also offer clues into predictors and sources of national differences in hopes of rethinking what influences mental and physical health for cohorts of middle-aged adults (for research providing insights on differential predictors of health and well-being across nations, see Kitayama et al., 2015; Ryff et al., 2015).

Methods

Longitudinal panel surveys consisting of nationally representative samples were used from five different nations, including the U.S. Health and Retirement Study (HRS), Household, Income, and Labour Dynamics of Australia (HILDA), German Socio-Economic Panel Study (SOEP), Korean Longitudinal Study of Aging (KLoSA), and Mexico Health and Aging Study (MHAS). Descriptions of participants, procedures and data accessibility for each study are reported in previous publications (HRS: McArdle et al.,2007; HILDA: Watson, 2010; SOEP: Wagner et al.,2007; KLoSA: Park et al.,2007; MHAS: Wong et al.,2017). We chose outcomes across the mental and physical health domains because these have conceptually and empirically been shown to be pertinent for middle-aged adults (Infurna et al., 2020). We note that not all studies included the same exact measures. For physical health, three out of five studies assessed health conditions and each study assessed physical functioning and self-rated health. Each study included measures pertaining to mental health, and cognition was included in two studies. Previous research has shown evidence to suggest cross-national equivalence in the measures included (Hu & Lee, 2011; Jain et al., 2016; Jebb et al., 2020), but we note that measurement equivalence continues to be one of the major challenges for cross-cultural comparisons and we elaborate on this in the Supplemental Online Materials (SOM). Due to space constraints, we provide a brief description of each study design, sample, and measures in the main text and present more detailed information on the measures, sample demographics (Table S1), and data collection time periods (Figures S1–S5) in the SOM. In each study, years of educational attainment was used as our indicator of SES. For our analyses, we included those observations in which participants were aged 40 (if available) thru 65 and participants were removed when they reached age 66 because this is the generally accepted age range for midlife (Lachman, 2004).

Participants, Study Designs, and Measures

United States: HRS.

The HRS is a nationally representative sample of households in the contiguous US of noninstitutionalized adults aged 50 years and older and their spouse (spouses younger than age 50 were included). Participants provide biennial reports on economic, psychosocial, mental, and physical health information. The HRS collects data via in-person and telephone interviews and every six years recruits a new cohort to refresh the sample.

We use biennial data obtained between 1992 and 2018 on functional limitations ([I]ADL; Rodgers & Miller, 1997), self-rated health (single-item), health conditions, depressive symptoms (CES-D; Radloff, 1977), and episodic memory (immediate and delayed recall). Our total sample for our analyses included 28,219 participants who were aged 40 thru 65 during the course of the study. The birth years represented in the data ranged from 1930 to 1969 (M = 1948, SD = 10.62).

Australia: HILDA.

The HILDA is a nationally representative panel study of households in Australia. Within a household, all persons aged 15 and over were invited to participate. Data are collected via face-to-face and telephone interviews and self-completed questionnaires.

We use annual data obtained between 2001 and 2018 on general perceptions of health, physical functioning, vitality, and mental health from the SF-36 (Ware et al., 1994) and single-item on life satisfaction. The total sample for our analyses included 10,836 participants aged 40 thru 65 during the study. The birth years represented are 1936 to 1969 (M = 1955, SD = 8.77).

Germany: SOEP.

The SOEP is a nationally representative panel study of households initiated in 1984 and covers residents of West and East Germany. All family members older than age 16 in a household were eligible for participation. Data is collected via face-to-face interviews and self-completed questionnaires. To reduce potential effects of the Berlin Wall coming down in 1989 and increase comparability with the other studies, we use data from 1992 through 2018.

Life satisfaction and self-rated health were assessed annually with single-items. Our sample for these analyses included 27,822 participants aged 40 thru 65 during the course of the study. The birth years represented in the data are from 1927 to 1969 (M = 1953, SD = 10.56).

Mental and physical health were assessed biennially from 2002 onwards using the SF-12 (Ware et al., 1994). Our total sample for these analyses included 22,610 participants aged 40 thru 65 during the study. The birth years represented are 1937 to 1969 (M = 1956, SD = 8.98).

South Korea: KLoSA.

The Korean Longitudinal Study of Aging began in 2006 and biennially collects data from people aged 45 and older who reside in South Korea not inclusive of Jeju Island. Data are collected via in-person computer assisted personal interviewing (CAPI).

We use biennial data obtained between 2006 and 2016 on functional limitations ([I]ADL; Rodgers & Miller, 1997), self-rated health (single-item), health conditions, cognition (MMSE), life satisfaction (single-item), and depressive symptoms (CES-D; Radloff, 1977). The sample for our analyses included 6,402 participants who were aged 45 thru 65 years during the course of the study. The birth years represented in the data are from 1938 to 1961 (M = 1951, SD = 6.20).

Mexico: MHAS.

The MHAS began in 2001 as a panel survey of people aged 50 years and older and their partners, living in private dwellings in both urban and rural areas in Mexico.

We use data from 2001, 2003, 2012, 2015, and 2018 on functional limitations ([I]ADL; Rodgers & Miller, 1997), self-rated health (single-item), health conditions, and depressive symptoms (CES-D; Radloff, 1977). The total sample for analyses was 20,803 participants aged 40 thru 65 during the study. The birth years represented are 1936 to 1969 (M = 1953, SD = 9.20).

Statistical Analyses

Time-in-study, age, and cohort.

Following Gerstorf et al. (2019), we examined intraindividual change as time-in-study, a time-varying variable quantified for each assessment as the number of years since baseline (T1) and centered at the middle of each individual’s repeated measures time-series. Age-related differences (age gradients) were examined as individuals’ chronological age (at their middle assessment) and centered at age 55, close to the average age within each of the samples. Cohort-related differences were examined as individuals’ birth year. Birth year was centered such that the earliest-born participants within each study served as the reference (for details, see Tables S2–S9 notes in SOM).

Data analysis.

Intraindividual changes, age-related, and history-related differences were examined using growth curve models (Grimm et al., 2017). We analyzed our data using growth curve models because our objective was to track how key indicators of physical and mental health develop as people move through midlife (i.e., within-person change) and how this may differ across historical times (i.e., between-person differences). For further conceptual and methodological reasoning of our selection of using growth curve models, please see SOM. Two models were estimated for each outcome within each sample. The first model examined whether there are cohort differences in levels and rates of change across each outcome and specified as

| (1) |

where person i’s score on the outcome at observation t, outcometi, is modeled as a function of a person-specific intercept, β0i; a person-specific linear slope coefficient, β1i; a person-specific quadratic slope coefficient, β2i, and residual error eti. Individual differences in the person-specific coefficients were modeled as

| (2) |

(i.e., Level 2 model) where γ00, γ10 and γ20 are the sample means or fixed-effects from the model and u0i and u1i estimate between-person differences in each parameter and are assumed to be normally distributed, correlated with each other, and uncorrelated with the residual errors, eti.

In the second model, we examined the role of education and accounted for gender and race (in the US sample) in the person-specific intercepts and linear rates of change, β0i and β1i; and tested all interaction terms with birth year. To maintain parsimony, if birthyear2 was not statistically significant, we dropped it and its interactions from the model. Person-level predictors were effect-coded/centered so that parameters indicated the average trajectory and differences associated with a particular variable (rather than a particular group). Models were fit using SAS (Proc Mixed; Littell et al., 2006). Following good practice (e.g., Grimm et al., 2017), we used Full Information Maximum Likelihood procedures to accommodate incomplete data under usual missing at random assumptions (Little & Rubin, 1987), with included variables (i.e., age, gender, and education) serving as attrition-informative variables that alleviate longitudinal selectivity for outcomes (McArdle, 1994). Background information on this procedure can be found in the SOM.

Results

The results are presented by category of outcome (physical health and mental health), followed by analyses pertaining to education. Our attention is focused on describing similarities and differences in cohort effects within and across nations. The SOM contains more detailed explanation of findings (e.g., age-related changes, gender and race differences), as well as Tables S2 to S9 provide the parameter estimates from the longitudinal models for each outcome.

Historical Trends of Health and Well-Being in Middle-Aged Adults

Physical health.

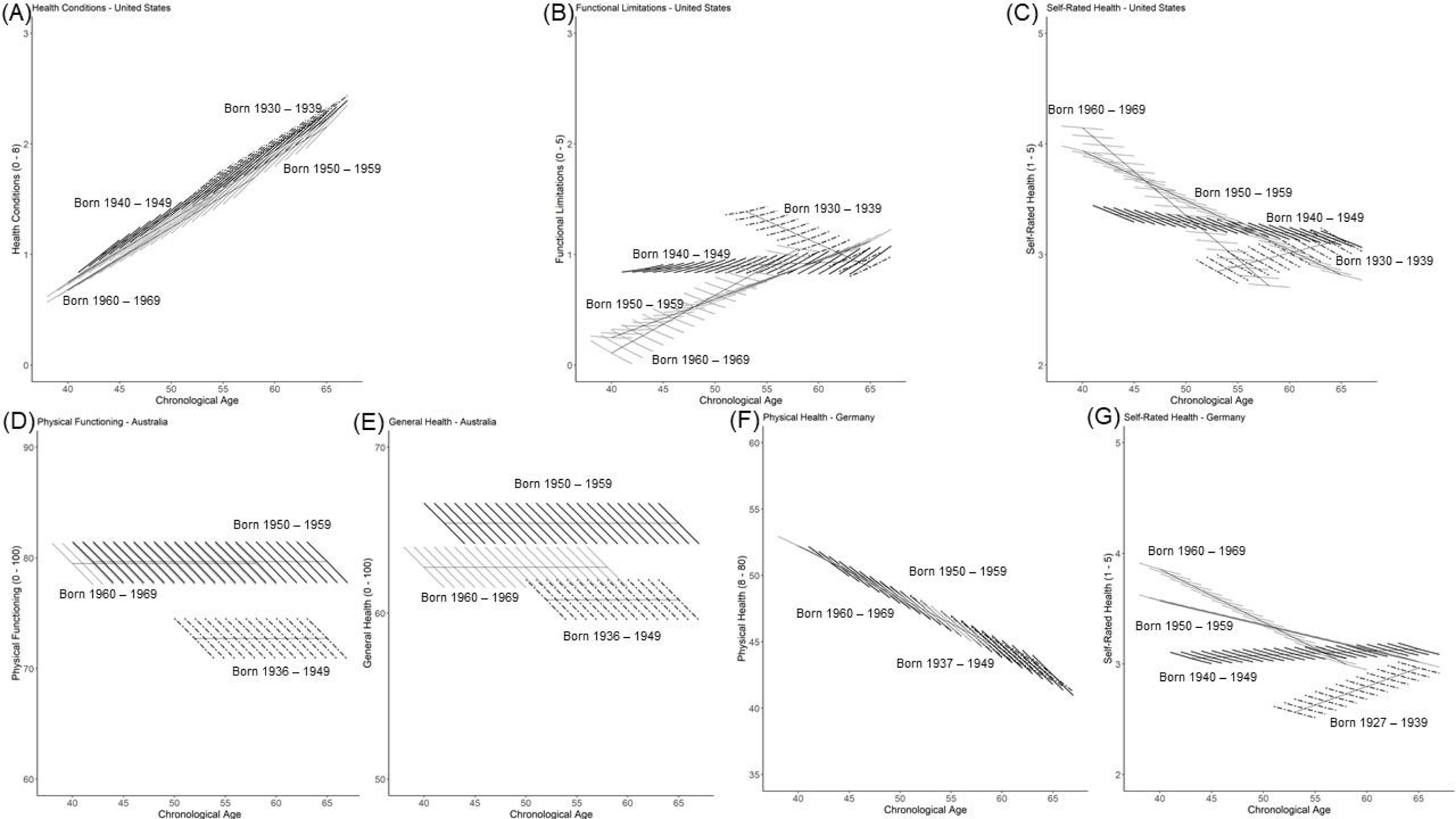

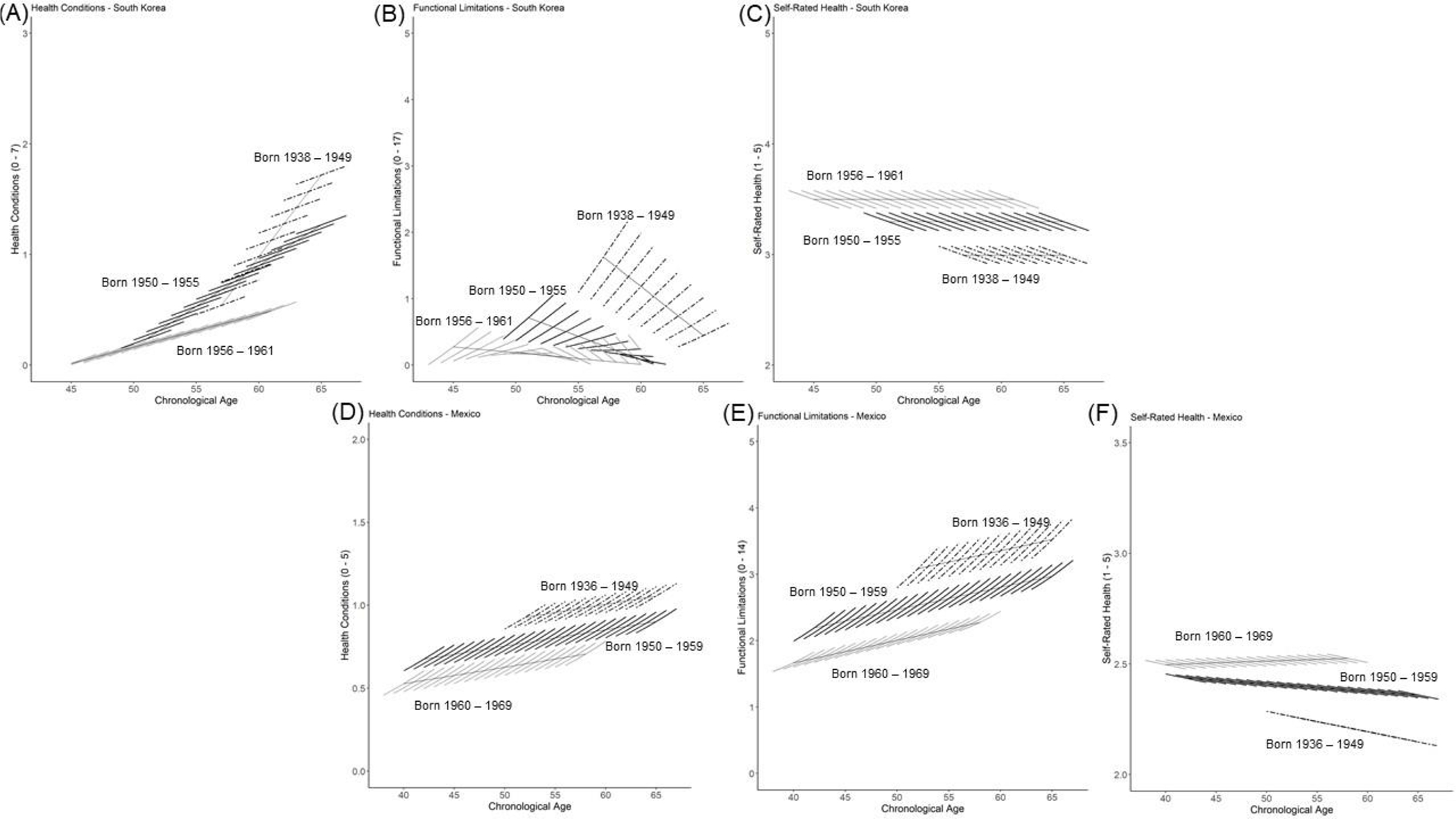

Results from growth curve models examining cohort-related differences in physical health are shown in Tables S2 and S3. Significant cohort effects were found for most outcomes with the magnitude and direction differing. Figure 1 graphically illustrates the findings for the US, Australia, and Germany and Figure 2 graphically illustrates the findings for South Korea and Mexico. For each figure and those that follow for mental health and education, the figures show for each cohort as a long, thin line the age and selection trends across midlife from age 40 to age 65 and as short-thick lines the model-implied within-person changes over 5 years with 1-year age increments. From Figures 1 and 2, it can be obtained that later-born cohorts across each nation, on average, reported fewer health conditions (Figure 1A, Figure 2A, and 2D). On average, later-born cohorts across each nation (except for Germany) reported better physical functioning (Figure 1B, 1D, 1F, 2B, 2E). Consistent across each nation, later-born cohorts, on average, reported better self-rated health (Figure 1C, 1E, 1G, 2C, and 2F). For the US, later-born cohorts showed historical improvements for physical functioning and self-rated health from ages 40 to 55, with advantages dissipating in the late 50s and early 60s. In sum, we observed historical improvements for people in their 40s and early 50s in physical health across all five nations.

Figure 1.

Cohort differences in model-implied trajectories in physical health for the US, Australia, and Germany. Across the nations, later-born cohorts reported fewer health conditions and functional limitations and better self-rated health. In the US, later-born cohorts reported better self-rated health and fewer functional limitations across ages 40 to 55, but improvements dissipated in the late 50s and early 60s.

Figure 2.

Cohort differences in model-implied trajectories in physical health for South Korea and Mexico. Later-born cohorts in each nation reported fewer health conditions and functional limitations and better self-rated health.

Mental health.

Results from growth curve models examining cohort-related differences in mental health are shown in Tables S4 and S5. Significant cohort effects were found for most outcomes with the magnitude and direction differing across them. Figure 3 graphically illustrates the findings for the US, Australia, and Germany and Figure 4 graphically illustrates the findings for South Korea and Mexico. For the US and Australia, Figure 3 demonstrates that later-born cohorts, on average, reported poorer overall mental health in the form of more depressive symptoms (Figure 3A), poorer memory (Figure 3B), and lower levels of mental health and well-being (Figures 3C, 3D, and 3E). In the US, when comparing at age 55 those born 1930 to 1939 with those born 1960 to 1969, the later-born cohort reported 0.60 more symptoms (d = 0.39). Historical trends in the rate of within-person change were observed in the US such that depressive symptoms increased over time, but were relatively stable for those born 1940 to 1949 and eventually declined for those born after 1950. In Australia, differences between earlier-born (1936–1949) and later-born (1960–1969) cohorts were in the medium effect size range for life satisfaction (d = 0.26) and mental health (d = 0.50). In contrast to this historical worsening in the US and Australia, later-born cohorts in Germany, South Korea, and Mexico each showed historical improvements in mental health (Figure 3F, 3G, Figure 4A, 4B, 4D) and cognition (Figure 4C). In Germany, for example, differences between earlier-born and later-born cohorts were in the medium to large effect size range for life satisfaction (d = .91) and mental health (d = .52). In Germany, historical trends in the rate of within-person change were also observed with later-born cohorts reporting increasing life satisfaction and mental health across midlife. Broadly speaking, we observed historical worsening of mental health and well-being in the US and Australia, but historical improvements in Germany, South Korea, and Mexico.

Figure 3.

Cohort differences in model-implied trajectories for mental health and well-being in the US, Australia, and Germany. In the US and Australia, later-born cohorts exhibited poorer mental health and well-being, whereas for Germany improvements in mental health and well-being were observed across cohorts.

Figure 4.

Cohort differences in model-implied trajectories for mental health and well-being in South Korea and Mexico. In each nation, on average, later-born cohorts reported better mental health and well-being.

Education.

Results from growth curve models that additionally included education and controlled for gender and race are shown in Tables S6 to S9. The general picture that consistently emerged across each of the nations was that attaining more years of education was associated with better functioning across the outcomes examined and by and large this did not differ across cohorts. There are some qualifications, though, to this picture of the advantages of education, particularly in the US in that the protective effects of education were diminished in later-born cohorts. Figure 5 graphically illustrates the findings for depressive symptoms, self-rated health, and memory. Figures 5A and 5B show that the differences between participants who attained a high school education vs. those who attained a college education is smaller for later-born cohorts. Attaining more years of education was associated with fewer depressive symptoms, but the protective effect for those who attained a college education dissipated in later-born cohorts (see those born in 1950 to 1959 and 1960 to 1969 in Figure 5B). The amount of historical increases in depressive symptoms is larger for those who completed college. Self-rated health revealed a similar pattern to that of depressive symptoms (see Figure 5C and 5D); more years of education was associated with higher levels of self-rated health, but this effect reversed in later-born cohorts with those attaining a college education reporting stronger declines across midlife (see those born in 1960–1969) than their well-educated age peers in earlier-born cohorts (see those born 1940 to 1949). Focusing on episodic memory, those who attained more years of education were more likely to exhibit better memory, but this effect was reduced in later-born cohorts (see Figures 5E and 5F) with those attaining a college education exhibiting lower levels of memory in later-born cohorts than their well-educated age peers in earlier-born cohorts.

Figure 5.

The effect of education on cohort differences for depressive symptoms, self-rated health, and episodic memory in the US. Broadly speaking, attaining more years of education was beneficial for earlier-born cohorts, but this dissipated for later-born cohorts in that the amount of historical increases in depressive symptoms and historical declines in self-rated health and episodic memory is larger for those who completed college. This is exemplified with the differences between those who attained a high school education vs. those who attained a college education becoming smaller over successive birth cohorts. For example, for those born in the 1930s, there is a noticeable difference in depressive symptoms between the two education groups at age 55, whereas this gap dissipates for those born in the 1960s. A similar pattern is observed for episodic memory and self-rated health.

Discussion

Our findings demonstrate that historical declines in US middle-aged adults’ mental and physical health do not necessarily generalize across other nations. Similar to the US, later-born cohorts of middle-aged adults in Australia exhibited historical declines in mental health. In contrast, we observed historical improvements in midlife mental and physical health in Germany, South Korea, and Mexico. Consistent across nations, those who attained fewer years of education benefitted the least from historical improvements. However, in the US, there was evidence to suggest that the protective effect of educational attainment dissipated in later-born cohorts. Our discussion elaborates on potential reasons underlying similarities and differences in historical changes across nations and SES and provides directions for future research.

Historical Trends of Mental and Physical Health in Midlife

Our findings follow a long scientific tradition that has utilized a lifespan developmental psychological framework in the study of cohort effects and cultural change across the lifespan. Research from Glen Elder (1974) documented how growing up during the Great Depression was profoundly shaped by how old the children were when they were going through the experience. Warner Schaie’s (1994) research found that trends in cognitive functioning differ in magnitude and direction by ability; historical improvements across cohorts were observed for inductive reasoning and verbal meaning, whereas number skills declined. Sutin and colleagues (2013) observed that later-born cohorts increased in well-being, but that cohorts who lived through the economic challenges of the early 20th century had lower well-being than those who lived during more prosperous times. A rich body of empirical evidence indicates that historical improvements in cognition, health, and well-being across a myriad of different countries have been most pronounced for those in the Third Age (i.e., their 60s and 70s; Gerstorf et al., 2020). In contrast, middle-aged adults in the US and Australia – but not the three other nations examined here – are trending in the opposite direction. These results offer insights into potential predictors and causes of national differences in what contributes to mental and physical health for middle-aged adults.

Linkage of findings to research on cultural change.

Our findings complement previous research that observed global shifts toward individualist values and practices over the past 50–100 years (see Grossmann & Varnum, 2015; Santos et al., 2017). Such global shifts could be attributable to greater population density and its associations with higher marriage age, decreased fertility, and later degree completion (Sng et al., 2017). Similar research on young adults that has covered over 40 years of time observed that recent cohorts are displaying increases in external locus of control, decreases in civic interest and trust and increases in individualistic traits (Twenge & Campbell, 2010). Individualization and modernization carry psychological costs, such as reductions in close social connections and support structures that are key when it comes to maintaining mental and physical health. Overlapping across previous findings and the current investigation is how cultural differences remain sizeable and are likely driven by socioeconomic and demographic factors, social orientation and capital, and ecological pressures.

Here, we observed in the US and other high-income and upper-middle-income nations that population-level changes in mental and physical health can occur over a short period of time. Our findings in the US of declining mental health across cohorts is similar to recent research showing that middle-aged adults post the 2008 Great Recession are reporting poorer overall mental and physical health across various outcomes (Almeida et al., 2020; Kirsch et al., 2019), as well as research showing mental distress increasing in US middle-aged adults since the early 1990s (Blanchflower & Oswald, 2020). The physical health of US middle-aged adults in their 40s and early 50s historically improved, but such improvements disappeared in later midlife (i.e., late 50s and early 60s). This complements research showing that adults in their early 60s are exhibiting more functional limitations and disabilities today than earlier cohorts (Seeman et al., 2010). Memory showed historical declines across cohorts, which contrasts with findings of historical improvements, such as the Flynn effect, in general cognition (Schaie, 1994). Research suggests that longer exposure to economic downturns is associated with poorer cognition (Burgard & Kalousova, 2015). One possible explanation for such dissipating improvements for later-born cohorts of US middle-aged adults is consequences of the Great Recession, which involved poorer physiology and increased work stress, income inequality, and healthcare costs (Burgard & Kalousova, 2015). Earlier-born cohorts in our US sample (i.e., those born in the 1930s and 1940s) were in midlife during the 1990s and early 2000s, whereas later-born cohorts of middle-aged adults were in their late 40s and 50s during the time leading up to and following the Great Recession. During times of recession, governments implement austerity measures that could disrupt prevention and treatment services provided by the public health and medical care systems and reduced funding to social protection programs, even as demands may rise (Burgard & Kalousovia, 2015).

Cross-national comparisons of cohort differences in midlife mental and physical health.

Of the nations included, Australia’s changes most closely mirrored those of the US in that there were historical declines in later-born cohorts’ mental health, but general improvements in physical health. Similar to the US, Australia is in the midst of an opioid epidemic that has led to many lives lost in death, whereas there is no evidence of this in Germany and other European nations, as well as South Korea (Lee, 2019; Shipton et al., 2018). The opioid epidemic has likely led to weakened family and community relationships and taken a toll on worker productivity, income, and gainful employment (Shipton et al., 2018). Economic research has shown increases in psychosocial job stressors and job insecurity, as well as greater government austerity measures that have reduced access to preventive social and health services, especially in regions with higher unemployment rates (Milner et al., 2014). The lack of employee commitment to workers may leave the worker without any feeling of connection and/or need to stay or be connected to work and/or a good employee. Long-term deterioration in employment opportunities could lead to rising income inequality, wage stagnation, less social protection and employment benefits, and intergenerational decline in employment security (Glymour et al., 2014).

A common theme for the findings pertaining to Germany, South Korea, and Mexico was historical improvements in both mental and physical health across cohorts of middle-aged adults. One overarching commonality across these nations for cohorts of middle-aged adults is the amount of socioeconomic changes that occurred. In the case of Germany, the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989 led to expansion of employment opportunities through investment of West German companies into East Germany, and West German regions with high concentration of households with social ties to the East exhibited substantially higher growth in income per capita in the early 1990s (Burchardi & Hassan, 2013). The fall of the Berlin Wall led to added years of life expectancy and broader trends of improvements in modifiable cardiovascular disease factors (Vogt, 2013). Follow-up analyses examining whether findings pertaining to Germany differed for those living in West or East Germany in 1989 did not reveal any differences in cohort effects based on location. Of note is also that the economy in Germany was hardly hit by the Great Recession. In the case of South Korea, the nation underwent short-term but intense socioeconomic changes after the liberation from the Japanese occupation during World War II (Heo et al., 2017). By taking into consideration when the KLoSA data were collected, 2006 to 2016, this was following the Asian financial crisis that began in 1997 and devastated the South Korean economy and altered many components of society until the mid-2000s (Lee & Yi, 2018). Furthermore, research shows high levels of social and political trust among South Koreans, largely due to now well-functioning economic, political, and welfare systems (Lee & Yi, 2018).

Mexico has seen gains in economic activity and healthcare reform in the last several decades, which could be driving the observed historical improvements in mental and physical health. The implementation of NAFTA improved economic activity through export-led growth driven by sales of manufactured goods, declines in inflation and surge in non-oil exports and foreign direct investment (Moreno-Brid et al., 2005). Focusing on healthcare reform, Mexico has seen substantial long-term public investment in its healthcare system through institutional and human resource development, and adoption of conceptual frameworks (WHO framework for health system performance), resulting in improvements in life expectancy and decreases in infant/child mortality (Frenk et al., 2006). By offering social protection in health via insurance to all citizens, reform is aimed to reduce catastrophic and out-of-pocket spending while promoting efficiency, equitable resource distribution and better-quality care (Knaul & Frenk, 2005).

Potential explanations for cross-national differences.

A big-picture question that arises from our findings is why historical trends in the US and Australia differed from those observed in Germany, South Korea, and Mexico? Furthermore, our findings contradict recent research from the WHO showing global increases in depression over time that spans generations (e.g., Baby Boomers, Generation X; WHO, 2017). Potential explanations span methodological and conceptual considerations. Methodologically, the nature of the analyses differs in that the WHO used cross-sectional data that confounds age and cohort, whereas we examined cohort changes using within-person longitudinal data. The contrasting approaches has been long-debated in the literature and due to space limitations cannot be given further attention here (see for example, Galambos et al., 2020). Conceptually, there are idiosyncrasies within nations that could lead to differences in historical trends observed here and with the WHO; we elaborate on them below.

At this juncture, we can only speculate, but we believe that nation-level differences in resource availability and economics have contributed to these differences. The nations included in our analyses profoundly differ in their healthcare systems. The US spends the most on healthcare, but ranks poorly on accessibility, patient safety, coordination, efficiency, and equity (Case & Deaton, 2020). Although the Affordable Care Act resulted in the uninsured rate declining and expansion of Medicare and Medicaid (Obama, 2016), the out-of-pocket costs associated with attaining healthcare continue to rise. Rising healthcare costs have a direct impact on one’s ability to put money in savings and retirement accounts, utilize preventive treatments (statins, hypertensives), and pay monthly bills (Case & Deaton, 2020; Infurna et al., 2020). Furthermore, lack of a centralized healthcare system may be a contributing factor in the opioid crisis in the US; Lee (2019) argues that a national healthcare system could help strictly monitor the distribution of such potent medications, whereas people who abuse are ambiguous under a private healthcare system that is under control of private insurance companies.

Another major factor to consider is the nature of employment. The last several decades have seen the landscape of work altered, which has implications for mental and physical health (see Dutton & Heaphy, 2003). Case and Deaton (2020) argue that the globalization of the economy, coupled with the outsourcing of American manufacturing jobs and the dehumanization of employees via the destabilization of unions has held great impact. Life-long commitment to a singular job is unlikely, and long-term commitment to the employee is also increasingly uncommon (Case & Deaton, 2020). Current cohorts of middle-aged adults are living in a time of rising income inequality and stagnant wages. The stagnation of wages and benefits, and lack of linkage, commitment and security from employers, coupled with large amounts of student debt, are dampening one’s ability to buy a home, start a family, and weigh on them and so may contribute to the historical worsening of mental and physical health.

Another factor to consider is changing family demographics that could lead to increasing stress among middle-aged people. There have been historical shifts in family composition given that today more people are unpartnered, do not have children, and are marrying later, along with people having more and different types of relationships due to remarriages and blended families (Fingerman, 2017). The result is more people who are single, in addition to middle-aged adults having fewer siblings with whom to share family stresses and burdens (Feinberg, 2018). At the same time, increasing numbers of middle-aged adults are taking on caregiving responsibilities for their aging parents and (re)launching grown-up children into adulthood (Reinhard et al., 2019). This showcases the double-edged sword nature of relationships; not all relationship types are beneficial for mental and physical health (Fingerman, 2017; Walen & Lachman, 2000).

Historical Change in Midlife Mental and Physical Health: Variations by Education

A consistent finding across the nations included was that individuals who attained more years of education were more likely to exhibit better functioning across the outcomes included. This finding, with a few exceptions in the US, did not differ across cohorts, suggesting that attaining more years of education has universal beneficial effects and coincides with opportunities for advanced education having increased dramatically for recent cohorts (Gerstorf et al., 2020). There are several possibilities for why this may be. Research on SES has long shown how individuals attaining more years of education are more likely to have better coping strategies for handling stress and engage in health-promoting behaviors, such as more physical activity and less likely to smoke and drink excessively (Adler et al., 1994). There is a premium that comes with attaining more years of education, such as the availability of better jobs that are less physically demanding, come with more job security and higher pay (Case & Deaton, 2020). Put differently, those who do not continue their education beyond high school are experiencing historical trends of more job insecurity, which can impact the meaning and status that work confers and less accessibility to affordable and high-quality healthcare (Case & Deaton, 2020).

Education findings specific to the US.

A surprising exception that was specific to the US was that the benefits of attaining more years of education dissipated or waned for later-born cohorts of middle-aged adults. This is exemplified in Figure 5, where those who attained a college education and were born in the 1960s reported stronger increases in depressive symptoms, declines in self-rated health, and lower levels of episodic memory across midlife than their similarly well-educated age peer in earlier historical times. Why might this be? One explanation could be due to degree inflation or the movement to require college degrees for entry level jobs that previously did not require advanced education. Another explanation is that the many challenges of midlife permeate all levels of education. Recent decades have seen a rise in parenting pressures in the form of investment in children’s success and greater involvement in school and extracurricular activities, which can negatively impact both kids and parents across mental health and substance use (Ebbert et al., 2019). Adult children of those in midlife have increasing difficulty in finding long-term job stability because of fewer job prospects, which can create a financial burden and weigh on the mental health of middle-aged parents (Infurna et al., 2020). On the other end of the generation spectrum is middle-aged adults’ involvement in caregiving duties and worries for aging family members. A recent AARP survey found that in 2017, family caregivers in the US provided 34 billion hours of care with their unpaid contributions valued at approximately $470 billion (Reinhard et al., 2019). On top of this, middle-aged adults are currently facing unprecedented financial vulnerabilities due to labor market instability and a shrinking social and healthcare safety net due to a lack of family policies and comprehensiveness and accessibility to affordable healthcare services and coverage. These issues/problems in the US are not solely confined to those with low SES, but recent decades have seen individuals from all gradients of SES feeling the impact.

Future research exploring other SES factors.

We note that our focus on education was driven by previous research (Case & Deaton, 2015; Kirsch et al., 2019), but research has also shown the importance of other indices of SES in contributing to pertinent outcomes in midlife, including relative comparisons and social status. For example, Carol Graham’s (2009) research on relative comparisons to others highlights the importance of identifying and monitoring trends in well-being and how future beliefs (i.e., hope and optimism) are linked to health, well-being, and economic opportunities. Analogous to this is Keith Payne’s (2017) research on the subjective social status ladder, which revealed that where people place themselves on the ladder in relation to others is predictive of health, well-being and economic outcomes. Future research would benefit from examining the extent to which these indicators of how people view themselves in relation to others is a potential moderator of cohort differences.

Limitations and Future Directions

In closing, we note several study limitations that signal the need for future research. First, our focus was on identifying the existence of cohort differences in midlife mental and physical health within- and across nations. Future research is needed to comprehensively examine gender and race differences. For example, we found gender differences in historical change across several nations, with later-born cohorts of women in the US reporting lower self-rated health and more depressive symptoms and in Australia, later-born cohorts of women reported poorer vitality (see SOM for further description). This falls in line with research showing that women are disproportionally impacted by some of the expectations of midlife, such as caregiving duties (Feinberg, 2018). We also found that in South Korea, later-born cohorts of women reported better self-rated health, fewer depressive symptoms and exhibited better cognition.

In the US sample, individuals who were white were more likely to report better mental and physical health across outcomes. Only one race by cohort interaction was significant; later-born cohorts of individuals who were white, on average, exhibited fewer depressive symptoms. These findings call for more research on mechanisms for gender and race differences within- and across nations and what individual- and nation-level resources could mitigate such disparities.

A second limitation was that we did not include nation-level factors in our analyses because of the lack of integrated longitudinal data sets across countries; we were restricted in what data were available to test the questions at hand. However, in the US and Australia, we found similarities in declining mental health, whereas historical improvements were observed across the outcomes examined for Germany, South Korea, and Mexico. This points to future research needing to examine whether differences in government programs pertaining to family leave and healthcare, as well as neighborhood and economic indicators (e.g., GINI coefficient, residential mobility) could account for such nation-level differences. Research within the US has found that individuals who lived in states that have implemented more conservative policies were more likely to experience a reduction in life expectancy from 1970–2014 (Montez et al., 2020). A third limitation was our focus on high- and upper-middle-income nations; future research is needed to examine whether our findings extend to other nations with different cultural backgrounds and perspectives. It is an open-question whether similar trends transpire in nations across the income spectrum. A fourth limitation centers on the measures not entirely being the same across studies and the designs slightly differing. Research on cross-national measurement equivalence is continuing to evolve, with a focus on harmonization (Hu & Lee, 2011). Lastly, our focus on descriptively identifying national differences in midlife mental and physical health limited our ability to examine individual-level factors that could operate as resources individuals can rely on to mitigate against historical declines. Psychosocial resources, such as social support and control beliefs are prime factors to first focus on due to existing research demonstrating their ability to promote resilience and their malleability to intervention (see Infurna et al., 2020).

Conclusion

Our findings paint a picture of historical changes in the mental and physical health of middle-aged adults that differs across nations. Given the challenging circumstances currently confronting the world in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic, it is an open question as to what the long-term ramifications will be, but due to its apparent economic, social, and psychological consequences (Vanderweele, 2020). Initial research has shown how adults are doing more poorly now, as compared to before the COVID-19 pandemic (APA, 2020). We speculate that our findings pertaining to the worsening of mental health in later-born cohorts of US middle-aged adults and disparities based on SES, gender, and race could continue and extend to physical health outcomes and to cohorts born in the 1970s and 1980s. Insights into individual- and nation-level resources can help identify factors that can make a difference in promoting health and well-being across time for the greater good for middle-aged adults and the families who rely on them.

Supplementary Material

Public Significance:

Recent empirical evidence has documented that large segments of US middle-aged adults are suffering more than in the past; one overarching question that arises is to what extent is this phenomenon confined to the US or whether it is transpiring in similar ways across other high-income and upper-middle-income nations around the globe? Middle-aged adults in each nation showed historical improvements in physical health until the early 50s, but middle-aged adults in the US and Australia experienced historical declines in mental health, whereas middle-aged adults in Germany, South Korea, and Mexico reported historical improvements in mental health. We discuss potential reasons why similarities and differences emerge in middle-aged adults across different nations and elaborate on directions for future research.

References

- Adler NE, Boynce T, Chesney MA, Cohen S, Folkman S, … & Syme SL (1994). Socioeconomic status and health: The challenge of the gradient. American Psychologist, 49(1), 15–24. 10.1037/0003-066X.49.1.15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Almeida DM, Charles ST, Mogle J, Drewelies J, Aldwin CM, Spiro III A, & Gerstorf D (2020). Charting adulthood development through (historically changing) daily stress processes. American Psychologist, 75(4), 511–524. 10.1037/amp0000597 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychological Association (2020). Stress in America 2020: A National Mental Health Crisis.

- Baltes PB (1987). Theoretical propositions of life-span developmental psychology: On the dynamics between growth and decline. Developmental Psychology, (5), 611–626. 10.1037/0012-1649.23.5.611 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Baltes PB, Lindenberger U, & Staudinger UM (1998). Life-span theory in developmental psychology. In Damon W & Lerner RM (Eds.), Handbook of child psychology (5th ed., Vol. 1, pp. 1029–1143). New York: Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- Banks J, Marmot M, Oldfield Z, & Smith JP (2006). Disease and disadvantage in the United States and in England. JAMA, 295(17), 2037–2045. 10.1001/jama.295.17.2037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beckfield J & Bambra C (2016). Shorter lives in stingier states: Social policy shortcomings help explain the US mortality disadvantage. Social Science & Medicine, 171, 30–38. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2016.10.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanchflower DG, & Oswald AJ (2020). Trends in extreme distress in the United States, 1993–2019. American Journal of Public Health, e1–e7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burchardi KB & Hassan TA (2013). The economic impact of social ties: Evidence from German Reunification. The Quarterly Journal of Economics,128(3),1219–1271. 10.1093/qje/qjt009 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Burgard SA, & Kalousova L (2015). Effects of the Great Recession: Health and well-being. Annual Review of Sociology, 41, 181–201. 10.1146/annurev-soc-073014-112204 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Case A, & Deaton A (2015). Rising morbidity and mortality in midlife among white non-Hispanic Americans in the 21st century. PNAS, 112(49), 15078–15083. 10.1073/pnas.1518393112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Case A, & Deaton A (2020). Deaths of despair and the future of capitalism. Princeton. [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y, Sloan FA (2015) Explaining disability trends in the U.S. elderly and near-elderly population. Health Services Research, 50(5), 1528–1549. 10.1111/1475-6773.12284 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen AB, & Varnum MEW (2016). Beyond east vs. west: social class, region and religion as forms of culture. Current Opinion in Psychology, 8, 5–9. 10.1016/j.copsyc.2015.09.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dutton JE, & Heaphy ED (2003). The power of high-quality connections. In Cameron KS, Dutton JE, & Quinn RE (Eds.), Positive organizational scholarship (pp. 263–278). SF: Berret-Koehler. [Google Scholar]

- Ebbert AM, Kumar NL, & Luthar SS (2019). Complexities in adjustment patterns among the „best and the brightest“: Risk and resilience in the context of high achieving schools. Research in Human Development, 16(1), 21–34. 10.1080/15427609.2018.1541376 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Elder GH Jr. (1974). Children of the Great Depression: Social change in life experience. Chicago, IL. [Google Scholar]

- Feinberg L (2018). Supporting employed family caregivers with workplace leave policies. [Google Scholar]

- Fingerman KL (2017). Millennials and their parents: Implications of the new young adulthood for midlife adults. Innovation in Aging, 1(3), igx026. 10.1093/geroni/igx026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forbes MK & Krueger RF (2019). The great recession and mental health in the United States. Clinical Psychological Science, 7(5), 900–913. 10.1177/2167702619859337 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frenk J, Gonzalez-Pier E, Gomez-Dantes O, Lezana MA, & Knaul FM (2006). Comprehensive reform to improve health system performance in Mexico, Lancet, 368(9546), 1524–1534. 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69564-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galambos NL, Krahn HJ, Johnson MD, & Lachman ME (2020). The U shape of happiness across the life course: Expanding the discussion. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 15(4), 989–912. 10.1177/1745691620902428 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerstorf D, Drewelies J, Duezel S, Smith J, Wahl H-W,…& Ram N(2019). Cohort differences in adult-life trajectories of internal and external control beliefs: A tale of more and better maintained internal control and fewer external constraints. Psychology & Aging, 34,1090–1108. 10.1037/pag0000389 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerstorf D, Hueluer G, Drewelies J, Willis SL, Schaie KW, & Ram N (2020). Adult development and aging in historical context.American Psychologist,75(4),525–539. 10.1037/amp0000596 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glymour MM, & Berkman LF (2014). Trends in Work-Family Context among U.S. Women by Education Level, 1976 to 2011. Population research and policy review, 33(5), 629–648. 10.1007/s11113-013-9315-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham C (2009).Happiness around the world:The paradox of happy peasants and miserable millionaires.

- Grande D, Barg FK, Johson S, & Cannuscio CC (2013). Life Disruptions for Midlife and Older Adults. Annals of Family Medicine, 11(1), 37–43. 10.1370/afm.1444 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grimm KJ, Ram N, & Estabrook R (2017). Growth modeling: Structural equation and multilevel modeling approaches. New York, NY: Guilford. [Google Scholar]

- Grossmann I, & Varnum MEW (2015). Social structure, infectious diseases, disasters, secularism, and cultural change in America. Psychological Science, 26(3), 311–324. 10.1177/0956797614563765 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heo J, Jeon S-Y, O, C-M., Hwang J, Oh J, & Cho Y (2017). The unrealized potential: Cohort effects and age-period-cohort analysis. Epidemiology and Health, 39, e2017056. 10.4178/epih.e2017056 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu P, & Lee J (2012). Harmonization of Cross-National Studies of Aging to the Health and Retirement Study: Chronic Medical Conditions. Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation. [Google Scholar]

- Infurna FJ, Gerstorf D, & Lachman ME (2020). Midlife in the 2020s: Opportunities and challenges. American Psychologist, 75(4), 470–485. 10.1037/amp0000591 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jain U, Min J, & Lee J (2016). Harmonization of cross-national studies of aging to the health and retirement study – user guide: family transfer – informal care. CESR-Schaeffer Working Paper. [Google Scholar]

- Jebb AT, Morrison M, Tay L, & Diener E (2020) Subjective Well-Being Around the World: Trends and Predictors Across the Life Span, Psychological Science, 31 (3), 293–305. 10.1177/0956797619898826 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson RW, & Wiener JM (2006). A profile of frail older Americans and their caregivers.

- Kirsch JA, Love GD, Radler BT, & Ryff CD (2019). Scientific imperatives via-a-vis growing inequality in America. American Psychologist, 74(7), 764–777. 10.1037/amp0000481 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitayama S, Park J, Boylan JM, Miyamoto Y, Levine CS … Ryff CD (2015). Expression of anger and ill health in two cultures: An examination of inflammation and cardiovascular risk. Psychological Science, 26 (2), 211–220. 10.1177/0956797614561268 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knaul FM, & Frenk J (2005). Health insurance in Mexico: Achieving universal coverage through structural reform. Health Affairs, 24 (6), 1467–1476. 10.1377/hlthaff.24.6.1467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lachman ME (2004). Development in Midlife. Annual Review of Psychology, 55(1), 305–331. 10.1146/annurev.psych.55.090902.141521 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lachman ME, Teshale S, & Agrigoroaei S (2015). Midlife as a pivotal period in the life course: Balancing growth and decline at the crossroads of youth and old age. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 39(1), 20–31. 10.1177/0165025414533223 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Launer LJ, Masaki K, Petrovitch H, Foley D, & Havlik RJ (1995). The association between midlife blood pressure levels and late-life cognitive function: The Honolulu-Asia Aging Study, JAMA, 1846–1851. 10.1001/jama.1995.03530230032026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee J-H (2019). The opioid epidemic and crisis in US: how about Korea? Korean Journal of Pain, 32(4), 243–244. 10.3344/kjp.2019.21.4.243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee J, Phillips D, Wilkens J, Chien S, Lin Y-C, Angrisani M, & Crimmins E (2018). Cross-country comparisons of disability and morbidity: Evidence from the Gateway to Global Aging Data. Journals of Gerontology: Medical Sciences, 73(11), 1519–1524. 10.1093/gerona/glx224 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee J, & Yi D (2018). Still a new democracy? Individual-level effects of social trust on political trust in South Korea. Asian Journal of Political Science. 10.1080/02185377.2018.1488595 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Littell RC, Miliken GA, Stroup WW, Wolfinger RD, & Schabenberger O (2006). SAS for mixed models (2nd ed.). Cary, NC: SAS Institute. [Google Scholar]

- Little RJA, & Rubin DB (1987). Statistical analysis with missing data. New York: Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- Margerison-Zilko Cl., Goldman-Mellor S, Falconi A, & Downing J (2016). Health impacts of the great recession: A critical review. Current Epidemiology Report, 3, 81–91. 10.1007/s40471-016-0068-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McArdle JJ (1994). Structural factor analysis experiments with incomplete data. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 29, 409–454. 10.1207/s15327906mbr2904_5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McArdle JJ, Fisher GG, & Kadlec KM (2007). Latent variable analyses of age trends from the Health and Retirement Study, 1992–2004. Psychology and Aging, 22(3), 525–545. 10.1037/0882-7974.22.3.525 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyamoto Y, Yoo J, Levine CS, Park J, Boylan JM … Ryff CD (2018). Culture and social hierarchy: Self- and other-oriented correlates of socioeconomic status across cultures. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 115 (3), 427–445. 10.1037/pspi0000133 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montez JK, Beckfield J, Cooney JK, Grumbach JM, Hayward MD, … & Zajacova A (2020). US state policies, politics, and life expectancy. The Milbank Quarterly, 98, 3, 668–699 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moreno-Brid JC, Santamaria J, & Valdivia JCR (2005). Industrialization and economic growth in Mexico after NAFTA: The road travelled. Development and Change, 36 (6), 1095–1119. [Google Scholar]

- Muening PA, Reynolds M, Fink DS, Zafari Z, & Geronimus AT (2018). America’s declining well-being, health, and life expectancy: Not just a white problem. AJPH, 108, 1626–1631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Obama B (2016). United States health care reform: Progress to date and next steps. JAMA, 316(5), 525–532. 10.1001/jama.2016.9797 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olshansky SJ, Antonucci T, Berkman L, Binstock RH, Boersch-Supan A, … & Rowe J (2012). Differences in life expectancy due to race and educational differences are widening, and many may not catch up. Health Affairs, 31(8), 1803–1813. 10.1377/hlthaff.2011.0746 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park JH, Lim S, Lim J-Y, Kim K-I, Han M-K, Yoon IY, … & Kim KW (2007). An overview of the Korean Longitudinal Study on Health and Aging. Psychiatry Investig, 4, 84–95. [Google Scholar]

- Payne K (2017). The broken ladder: How inequality affects the way we think, live, and die.

- Radloff LS (1977). The CES-D scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement, 1, 385–401. 10.1177/014662167700100306 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Reinhard SC, Feinberg LF, Houser A, Choula R, & Evans M (2019). Valuing the invaluable.

- Rodgers WL, & Miller B (1997). A comparative analysis of ADL questions in surveys of older people. The Journals of Gerontology: Psychological Sciences, 52B, 21–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roux AVD (2017). Despair as a cause of death: More complex than it first appears. American Journal of Public Health, 107, 10, 1566–1567. Doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2017.304041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryff CD, Miyamoto Y, Boylan JM, Coe CL, Karasawa M, … Kitayama S (2015). Culture, inequality, and health: Evidence from the MIDUS and MIDJA comparison. Culture Brain, 3, 1–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santos HC, Varnum MEW, & Grossmann I (2017). Global increases in individualism. Psychological Science, 28(9), 1228–1239. 10.1177/0956797617700622 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaie KW (1994). The course of adult intellectual development. American Psychologist, 49, 304–313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seeman TE, Merkin SS, Crimmins EM, & Karlamangla AS (2010). Disability trends among older americans: National health and nutrition examination surveys, 1988–1994 and 1999–2004. American Journal of Public Health, 100 (1), 100–107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shipton EA, Shipton EE & Shipton AJ (2018). A Review of the Opioid Epidemic: What Do We Do About It?. Pain & Therapy 7, 23–36. 10.1007/s40122-018-0096-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sng O, Neuberg SL, Varnum MEW, & Kenrick DT (2017). The crowded life is a slow life: Population density and life history strategy.JPSP,112(5),736–754. 10.1007/s40122-018-0096-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stephens NM, Markus HR, & Phillips LT (2014). Social class culture cycles: How three gateway contexts shape selves and fuel inequality. Annual Review of Psychology, 65(1), 611–634. 10.1146/annurev-psych-010213-115143 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sutin AR, Terracciano A, Milaneschi Y, An Y, Ferrucci L, & Zonderman AB (2013). The trajectory of depressive symptoms across the adult life span. JAMA Psychiatry, 70(8), 803–811. 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2013.193 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Twenge JM, & Campbell WK (2010). Birth cohort differences in the monitoring the future dataset and elsewhere: Further evidence for generation me. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 5(1), 81–88. 10.1177/1745691609357015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- United Nations (2020). World Economic Situation and Prospects. Retrieved from https://www.un.org/development/desa/dpad/wp-content/uploads/sites/45/WESP2020_Annex.pdf

- VanderWeele TJ (2020). Challenges estimating total lives lost in COVID-19 decisions. JAMA, 324(5), https://doi:10/1001/jama.2020.12187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varnum MEW, & Grossmann I (2017). Cultural change: The how and the why. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 12(6), 956–972. 10.1177/1745691617699971 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vogt TC (2013). How many years of life did the fall of the berlin wall add? A projection of east Germany life expectancy. Gerontology, 59(3), 276–282. 10.1159/000346355 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner GG, Frick JR, & Schupp J (2007). Enhancing the power of household panel studies: The case of the German Socio-Economic Panel Study (SOEP). Schmollers Jahrbuch, 127, 139–169. [Google Scholar]

- Wahl H-W, & Gerstorf D (2018). A conceptual framework for studying Context Dynamics in Aging (CODA). Developmental Review, 50(Part B), 155–176. 10.1016/j.dr.2018.09.003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Walen HR, & Lachman ME (2000). Social support and strain from partner, family, and friends: Costs and benefits for men and women in adulthood.JSPR,17,5–30. 10.1177/0265407500171001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ware JE, Kosinski M, & Keller SD (1994). SF-36 physical and mental health summary scales: A user’s manual. Boston, MA: The Health Institute, New England Medical Center. [Google Scholar]

- Watson N (2010). HILDA user manual—Release 8. Melbourne: University of Melbourne. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization (WHO): 2017. Depression and other common mental disorders: Global health estimates. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2017. Licence: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO. [Google Scholar]

- Wong R, Michaels-Obregon, & Palloni A (2017). Cohort Profile: The Mexican Health and Aging Study (MHAS). International Journal of Epidemiology, 46(2), e2. 10.1093/ije/dyu263 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woolf SH, Aron LUS Health in International Perspective: Shorter Lives, Poorer Health. Washington, DC: National Research Council and Institute of Medicine; 2013. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.