To the Editor:

The COVID-19 pandemic has put a major strain on healthcare systems around the globe. Early reports have shown sharp reductions in most non-COVID diagnoses, from aortic dissections to cancer.1 , 2 Efforts to control the pandemic have also had an important impact on the availability and capacity of viral hepatitis testing services.3 In addition, the perceived risk of COVID-19 may affect a patient’s willingness to visit healthcare professionals. Together, this may result in delayed or missed opportunities to diagnose patients with chronic viral hepatitis. A recent modelling study by Blach et al. published in Journal of Hepatology, underscores the potential detrimental effect on patient outcomes associated with disruptions in interventions aimed at viral hepatitis elimination.4 However, the magnitude of the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on viral hepatitis care in the EU region is currently unclear.

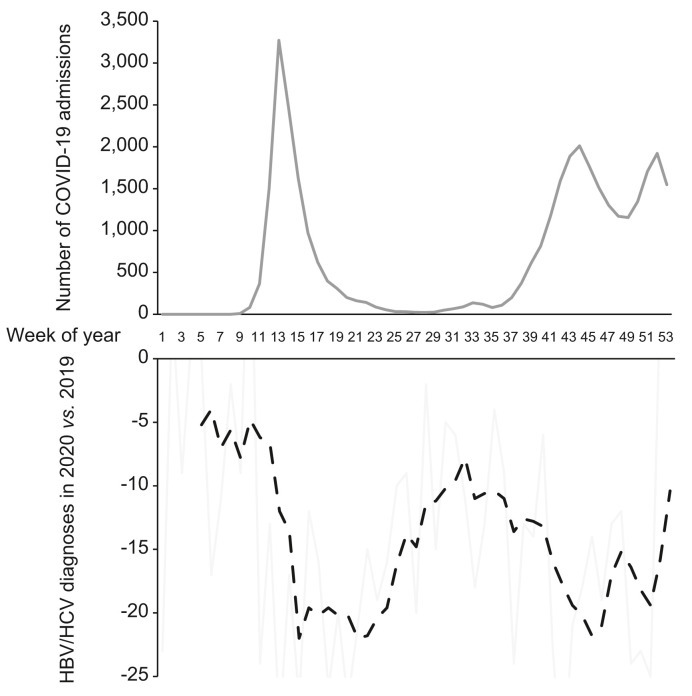

HBV/HCV infections are notifiable conditions under the Dutch Public Health Act, and testing facilities automatically report novel positive test results to the local Public Health Service. After assessment by specialised staff the cases are classified as novel acute or chronic infections and reported electronically to the National Institute for Public Health and the Environment. In order to assess the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on novel chronic HBV and HCV diagnoses, we compared the number of reported cases in 2020 to the number of cases reported in 2019. In 2019, there were 1,105 novel chronic HBV and 664 novel chronic HCV diagnoses, which declined to 674 and 379 in 2020. We therefore observed an overall reduction of novel chronic viral hepatitis diagnoses of 40% (39% for HBV and 43% for HCV, p <0.001 compared to 2019). Interestingly, the weekly relative reduction in new chronic HBV and HCV diagnoses mirrored the weekly number of COVID-19 admission in the Netherlands. The sharpest drops in novel reported cases coincided with the peaks of the first and second COVID-19 admission waves (COVID-19 data from the NICE foundation,5 Fig. 1 ). Still, even during the summer months when the number of COVID-19 admissions was limited, the number of reported chronic viral hepatitis cases remained below the number reported in 2019.

Fig. 1.

COVID-19 admissions and HBV/HCV diagnoses in the Netherlands.

The number of COVID-19 admissions in the Netherlands per week in 2020 (upper panel) and the reduction in the number of weekly reported new chronic HBV and HCV diagnoses in 2020 compared to the same week in 2019 (lower panel, with weekly reported cases in grey and the moving average in dashed black).

It is important to note that the current findings contrast sharply with previous observations that the number of reported acute HBV cases in the Netherlands did not decline during the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic.6 This discrepancy is probably explained by the high frequency of clinical symptoms in patients with acute HBV, which may prompt consultation with healthcare providers. Conversely, chronic HBV and HCV are often asymptomatic and novel cases are typically identified only through additional testing performed in patients with elevated liver enzymes found during evaluation of (often unrelated) non-specific complaints, or as part of screening for sexually transmitted infections. A study in primary care practices in the Netherlands reported a rapid decline in the number of patients consulting general practitioners for non-severe symptoms during the COVID pandemic,7 and the strong reduction in novel chronic viral hepatitis cases that persisted even during periods with low numbers of COVID admissions therefore most likely reflects missed opportunities for diagnosis and not delays in reporting. This is all the more relevant since the next opportunity for diagnosis may only come once the first liver-related complication has already developed.8 It is therefore imperative that once widespread vaccination strategies allow for reallocation of healthcare assets to non-COVID related care, we refocus our attention to meeting WHO hepatitis elimination goals by identifying and linking these non-diagnosed patients to care. We will continue our monitoring of viral hepatitis diagnoses in the Netherlands to quantify to what extent these efforts are successful.

Financial support

The authors received no financial support to produce this manuscript.

Authors’ contributions

Study concept and design, data acquisition and analysis, critical revision of manuscript for important intellectual content and approval of final version: all authors.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest that pertain to this work.

Please refer to the accompanying ICMJE disclosure forms for further details.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhep.2021.04.015.

Supplementary data

The following is the supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Dinmohamed A.G., Visser O., Verhoeven R.H.A., Louwman M.W.J., van Nederveen F.H., Willems S.M., et al. Fewer cancer diagnoses during the COVID-19 epidemic in the Netherlands. Lancet Oncol. 2020;21:750–751. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(20)30265-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.El-Hamamsy I., Brinster D.R., DeRose J.J., Girardi L.N., Hisamoto K., Imam M.N., et al. The COVID-19 pandemic and acute aortic dissections in New York: a matter of public Health. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020;76:227–229. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2020.05.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Simoes D., Stengaard A.R., Combs L., Raben D. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on testing services for HIV, viral hepatitis and sexually transmitted infections in the WHO European Region, March to August 2020. Euro Surveill. 2020;25 doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2020.25.47.2001943. Euro TC-iacop. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Blach S., Kondili L.A., Aghemo A., Cai Z., Dugan E., Estes C., et al. Impact of COVID-19 on global HCV elimination efforts. J Hepatol. 2021;74:31–36. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2020.07.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.https://www.rivm.nl/coronavirus-covid-19/grafieken. Last accessed on 19-03-2021.

- 6.Middeldorp M., van Lier A., van der Maas N., Veldhuijzen I., Freudenburg W., van Sorge N.M., et al. Short term impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on incidence of vaccine preventable diseases and participation in routine infant vaccinations in The Netherlands in the period March-September 2020. Vaccine. 2021;39:1039–1043. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2020.12.080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schers H., van Weel C., van Boven K., Akkermans R., Bischoff E., olde Hartman T. The COVID-19 pandemic in Nijmegen, The Netherlands: changes in presented Health problems and demand for primary care. Ann Fam Med. 2021;19:44–47. doi: 10.1370/afm.2625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lapointe-Shaw L., Chung H., Holder L., Kwong J.C., Sander B., Austin P.C., et al. Diagnosis of chronic hepatitis B peri-complication: risk factors and trends over time. Hepatology. 2020 Sep 15 doi: 10.1002/hep.31557. Online ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.