Abstract

Frontline health-care workers experienced moral injury long before COVID-19, but the pandemic highlighted how pervasive and damaging this psychological harm can be. Moral injury occurs when individuals violate or witness violations of deeply held values and beliefs. We argue that a continuum exists between moral distress, moral injury, and burnout. Distinguishing these experiences highlights opportunities for intervention and moral repair, and may thwart progression to burnout.

INTRODUCTION

The COVID-19 pandemic traumatized health-care workers. During its first 18 months, nearly 20% of the medical workforce left their jobs.1 The reasons are many, including shortages of staff and personal protective equipment, as well as shortages of critical care beds and equipment that potentially harmed patients.2–6 Clinicians felt distressed by their roles in allocating limited resources and in adjudicating which patients would receive treatment in inferior makeshift settings.3,6–8 During the Omicron wave, some health-care workers who tested positive for COVID-19 were required to return to work without isolating or further testing, potentially spreading the virus to patients.9 These scenarios amplified anguish among frontline workers, inflicting a kind of harm known as “moral injury.”

DEFINING MORAL INJURY

“Moral injury” is a term used in the military veteran literature to define a wound that results from “doing something that violates one’s own ethics, ideals, or attachments.”10 The term was introduced by Veterans Affairs psychiatrist Jonathan Shay to describe an experience not adequately captured by post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Whereas PTSD originates from a frightening or dangerous event, Shay identifies moral injury as a psychological trauma resulting from (1) a betrayal of what is morally correct, (2) by someone who holds legitimate authority, (3) in a high-stakes situation.11 The perpetrator of moral wrong is an authority figure, but the injury is inflicted on a subordinate who is required to carry out the morally violative action.

Brett Litz broadens the definition of moral injury to include “the lasting psychological, biological, spiritual, behavioral, and social impact of perpetrating, failing to prevent, or bearing witness [emphasis added] to acts that transgress deeply held moral beliefs and expectations.”12 Accordingly, moral injury can result from both acts of commission and acts of omission. Litz also utilizes a framework in which the individual is himself the actor of wrongdoing, as opposed to an authoritative figure or structure. In all cases, regardless of who commits the act in question, moral injury ruptures self-identity and can lead to feelings of guilt, shame, and social withdrawal.

Moral injury plagued medicine long before the current pandemic. Economic, legal, and institutional pressures frequently forced clinicians to treat patients in ways they found morally reprehensible, whether by rushing them through clinic visits or hospital stays, or by continuing aggressive treatments for dying patients. As Talbot and Dean put it, “The moral injury of health care is not the offense of killing another human in the context of war. It is being unable to provide high-quality care and healing in the context of health care.”13 Intractable morally violative acts have anguished clinicians, inducing moral injury.

THE RELATIONSHIP OF MORAL INJURY TO MORAL DISTRESS AND BURNOUT

Moral injury is distinct from, yet related to, two other concepts common in medical discourse: moral distress and burnout. (See Table 1.) Although individual experiences may not always fit neatly into one category, their differences remain important for distinguishing methods for intervention and repair.

Table 1.

Distinguishing Moral Injury from Moral Distress and Burnout

| Moral distress | Moral injury | Burnout | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Definition | “Psychological distress of being in a situation in which one is constrained from acting on what one knows to be right”14 | “The lasting psychological, biological, spiritual, behavioral, and social impact of perpetrating, failing to prevent, or bearing witness to acts that transgress deeply held moral beliefs and expectations”12 |

“A syndrome of emotional exhaustion, loss of meaning in work, feelings of ineffectiveness, and a tendency to view people as objects rather |

| Symptoms | Unease, discomfort, frustration, anger, feelings of powerlessness, palpitations | Guilt, shame, anger, disgust, social withdrawal, ruptured identity, existential crisis | Numbness, carelessness, disengagement, exhaustion, depersonalization |

| Duration | Acute | Chronic | Chronic |

| Methods for repair | Removal of inciting situation, systems reform, strengthening moral identity through community, cultivating moral resilience | Institutional-level structural reform; community- and peer-based interventions | Sabbatical; intensive therapy for addiction or depression; change of career |

| Potential consequences | Moral injury | Burnout | Medical error, malpractice, dissatisfied patients, staff turnover, addiction, suicide |

Andrew Jameton coined the term “moral distress,” characterizing it as “1) psychological distress of 2) being in a situation in which one is constrained from acting 3) on what one knows to be right.”14 Moral distress is the immediate result of participating in or witnessing a morally troubling situation. For example, a nurse might experience it when a doctor asks her to administer a treatment she finds objectionable. Moral distress might linger a few hours after the inciting event, but if her individual sense of the good remains intact, it often resolves.15 However, repeated or severe violations may leave a moral residue, which can accumulate and lead to moral injury.16,17

Whereas the nursing literature often focuses on moral distress, physicians commonly describe their work-related exasperation as “burnout.” Definitions vary somewhat, but burnout is generally understood as a combination of emotional exhaustion, depersonalization or cynicism, and a sense of reduced personal accomplishment.18,19 The prevalence of burnout among doctors varies widely, with more than half of U.S. physicians reporting at least one symptom.18,20

The diagnosis of burnout is not made uniformly; a recent meta-analysis found wide heterogeneity across indices used, as well as across score cutoffs within the same tool.20 Although moral distress and moral injury are not the only causes of burnout, moral injury can contribute to its core symptoms. The inability to practice medicine in a way that coheres with one’s moral expectations is distressing. Doubts about one’s abilities to carry out the good can lead to ineffectiveness and a reduced sense of personal accomplishment. Perhaps most significantly, moral injury can lead to cynicism, depersonalization, and disengagement.

But moral injury is not itself burnout. The fact that so many doctors are concerned about the possibility of burning out suggests that they are not yet emotionally numb. By contrast, physicians who burn out are no longer distressed at the violation of deeply held moral beliefs, because they are beyond feeling. The detachment and depersonalization associated with burnout can be viewed as the absence of distress or moral investment altogether.

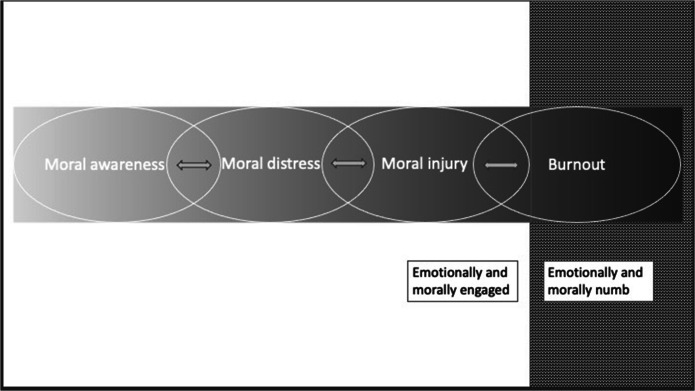

We offer a heuristic describing the interplay among moral awareness, distress, injury, and burnout. (See Fig. 1.) We argue that they exist on a spectrum. Moral distress, if sustained, is a common cause of clinician moral injury. If unchecked, moral injury may lead to burnout.21 In practice, the progression is often uneven, and there can be movement back and forth along the continuum. A singular morally distressing event may be so injurious that it leads swiftly to burnout.22 In others, the same event might trigger only moral distress. While not perfect, this continuum is helpful for considering interventions before burnout. Moral distress can be mitigated and moral injury thwarted if the inciting circumstance or event is removed. Addressing moral injury to prevent burnout is more difficult. It requires attending both to the organizational climates and structures that lead to ethical violations and to the clinician’s ruptured moral identity.

Figure 1.

Interplay among moral awareness, distress, injury, and burnout.

IDENTIFYING MORAL INJURY

Objective tools have been proposed for diagnosing moral injury. Koenig and colleagues adapted their scale for military veterans to a 10-item version specific for the health-care workforce, the MISS-HP.23 When administered to a cohort of clinicians in early 2020, the estimated prevalence of moral injury was 41%. An additional study used the 9-item Moral Injury Events Scale (MIES) to evaluate psychiatric symptoms and moral injury among U.S. health-care workers during the COVID-19 pandemic.24 Nineteen percent of respondents answered “yes” to the question “I acted in ways that violated my own moral code or values,” and 45% answered “yes” to the question “I feel betrayed by leaders who I once trusted.” Higher MIES scores were associated with higher rates of depression and anxiety.25

Although objective, easy-to-administer scales can be useful in identifying moral injury, clinicians and researchers emphasize that such metrics risk pathologizing moral injury, which ought not be considered a disorder.7,26,27 Moral emotions, as identified by the aforementioned screening tools, are proper and understandable responses to moral violation.28 By contrast, the locus of pathology is the set of circumstances that gives rise to moral violations—not the injured individual—which is why mindfulness or yoga sessions alone cannot fix moral injury. A context-driven problem requires context- and community-based solutions.29

PREVENTING AND REPAIRING MORAL INJURY

Although moral distress may be unavoidable in health care,21 moral injury and burnout are not. To prevent and repair moral injury and thwart its progression to burnout, health-care leadership must acknowledge that the problem is not individual weakness but rather systems and contexts in need of reform. Cultivating moral resilience allows clinicians to overcome moral obstacles in their practice and mitigate downstream effects of moral distress.30 However, clinicians, no matter how resilient, cannot indefinitely sustain excess workloads with paltry resources. Hospital administrators must therefore prioritize staffing and supply shortages as matters of first importance. Insufficient staffing was a key cause of nursing distress pre-COVID-19.31 Moreover, during the pandemic, some hospitals innovated by incorporating medical students and non-clinical staff into aspects of direct patient care, offering signing and retention bonuses, and cross-training clinical staff.32 Such measures can mitigate moral dissonance by reassuring clinicians that management is uncompromisingly dedicated to high-quality patient care.

Structural reforms are also necessary. Health-care settings can be highly chaotic, and chaotic work environments have been associated with stress and a desire to leave practice.33 Many institutions have experienced a substantial rise in patient volume over decades without a proportionate increase in staff or workspace, which translates into compromised care of patients. Twenty-five percent of patients who do not trust their doctors say it is because their doctors spend too little time with them.34 Permitting more patient-facing time by reducing patient volume and offloading non-medical tasks to support staff reinforce a culture committed to the well-being of both patients and clinicians. Furthermore, although admittedly difficult to come by, providing a sufficient quiet work space promotes a healthy environment in which clinicians can concentrate on practicing high-quality, ethical medicine.21

Clear communication from leadership is essential for rectifying the morally injurious sense among health-care workers that executives prioritize revenue over patient and clinician health. Only about half of physicians say they trust health-care leaders and executives34; this is a sobering statistic and creates a challenge for health-care leadership attempting to address clinician distress. Hoert and colleagues show that when employees trust that leadership is committed to their well-being, they report less job stress, greater wellness activity participation, and greater levels of health behavior.35 Health-care administrators and leadership have the responsibility to engage clinicians through transparent communication, and empower all members of the health system to raise questions and concerns toward the goal of improving institutional and personal well-being.36

In addition to addressing the circumstances and contexts that give rise to moral injury, health-care leadership and communities must work toward repairing the wounds of the morally injured themselves. During the COVID-19 pandemic, physician groups developed concrete approaches to building a community among frontline health-care workers. Fins and Resnick propose a model for peer support that promotes conversation among colleagues who have shared traumatic experiences, emphasizes bearing witness and normalizing clinicians’ reactions, and employs frequent expressions of gratitude.7 Psychiatrists at the University of Minnesota deployed a peer support model based on a U.S. Army framework, which assigns combatants a “Battle Buddy” capable of understanding their specific stressors. Similarly, the Minnesota program paired buddies within clinicians’ units and encouraged mutual contact 2 to 3 times per week. The goal was to promote clinicians’ sense of purpose and hopefulness—both critical for preventing moral injury.37 Additional promising resources for fostering supportive communities among health-care workers include Schwartz Rounds, Unit Based Ethics Conversation, the Moral Distress Map, and integrating chaplains trained in helping individuals process moral injuries.38–42

CONCLUSION

The COVID-19 pandemic has taken an enormous toll on health professionals who repeatedly have been forced to participate in and bear witness to situations that violate their deeply held beliefs. Some have progressed to burnout or have left the profession. However, most clinicians have stayed in their jobs and continue to care—both for their patients and for the moral integrity of their work. By reframing burnout as downstream of moral distress and moral injury, this paper offers hope to health-care professionals and leadership. Interventions that reduce moral distress and injury also diminish the likelihood of physician burnout.

The term moral injury reminds us of the profound moral questions involved in the practice of medicine. Clinicians are not simply tired after working long hours or physically strenuous shifts; they are taking great personal risk to care for their fellow human beings. As the U.S. Surgeon General’s Advisory on Addressing Health Worker Burnout insists, “we have a moral obligation to address the long-standing crisis of burnout, exhaustion, and moral distress across the health community. We owe health workers far more than our gratitude. We owe them an urgent debt of action.”43 To avoid widespread clinician burnout, moral injury must be identified and addressed before the wounds of health care result in permanent and irreversible loss.

Declarations

Conflict of Interest

AR was supported by grant number T32HS026121 from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Other authors have no pertinent conflicts of interest to report.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Galvin G. Nearly 1 in 5 Health Care Workers Have Quit Their Jobs During the Pandemic. https://morningconsult.com/2021/10/04/health-care-workers-series-part-2-workforce/. Updated 4 October 2021.

- 2.Kleinpell R, Ferraro DM, Maves RC, et al. Coronavirus Disease 2019 Pandemic Measures: Reports From a National Survey of 9,120 ICU Clinicians. Crit Care Med. 2020;48(10):e846–e855. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000004521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wahlster S, Sharma M, Lewis AK, et al. The Coronavirus Disease 2019 Pandemic's Effect on Critical Care Resources and Health-Care Providers: A Global Survey. Chest. 2021;159(2):619–633. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2020.09.070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shanafelt T, Ripp J, Trockel M. Understanding and Addressing Sources of Anxiety Among Health Care Professionals During the COVID-19 Pandemic. JAMA. 2020;323(21):2133–2134. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.5893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fernandez-Castillo RJ, Gonzalez-Caro MD, Fernandez-Garcia E, Porcel-Galvez AM, Garnacho-Montero J. Intensive care nurses' experiences during the COVID-19 pandemic: A qualitative study. Nurs Crit Care 2021. 10.1111/nicc.12589. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Butler CR, Wong SPY, Wightman AG, O’Hare AM. US Clinicians’ Experiences and Perspectives on Resource Limitation and Patient Care During the COVID-19 Pandemic. JAMA Network Open. 2020;3(11):e2027315–e2027315. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.27315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Resnick KS, Fins JJ. Professionalism and Resilience After COVID-19. Acad Psychiatry. 2021;45(5):552–556. doi: 10.1007/s40596-021-01416-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hossain F, Clatty A. Self-care strategies in response to nurses' moral injury during COVID-19 pandemic. Nurs Ethics 2021;28(1):23-32. (In eng). 10.1177/0969733020961825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 9.California Nurses Association. California nureses condemn state’s decision to send asymptomatic or exposed health care workers back to work without isolation or testing. https://www.nationalnursesunited.org/press/california-nurses-condemn-states-decision-to-send-health-care-workers-back-to-work. Updated 8 January 2022.

- 10.Shay J. Moral Injury. Intertexts. 2012;16(1):57–66. doi: 10.1353/itx.2012.0000. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shay J, Munroe J .“Group and Milieu Therapy for Veteras with Complex PTSD”. In: Saigh PA, Bremner, J.D., ed. Posttraumatic Stress Disorder, A Comprehensive Text. Boston, MA: Allyn & Bacon.

- 12.Litz BT, Stein N, Delaney E, et al. Moral injury and moral repair in war veterans: a preliminary model and intervention strategy. Clin Psychol Rev. 2009;29(8):695–706. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2009.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Talbot SG, Dean W. Physicians aren’t ‘burning out.’ They’re suffering from moral injury. STAT News. https://www.statnews.com/2018/07/26/physicians-not-burning-out-they-are-suffering-moral-injury/. Updated 26 July 2018.

- 14.Jameton A. Nursing practice : the ethical issues. Englewood Cliffs, N.J: Prentice-Hall; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Čartolovni A, Stolt M, Scott PA, Suhonen R. Moral injury in healthcare professionals: A scoping review and discussion. Nursing Ethics. 2021;28(5):590–602. doi: 10.1177/0969733020966776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Atuel HR, Barr N, Jones E, et al. Understanding moral injury from a character domain perspective. Journal of Theoretical and Philosophical Psychology 2021.

- 17.Epstein EG, Hamric AB. Moral distress, moral residue, and the crescendo effect. J Clin Ethics 2009;20(4):330-42. (In eng). [PubMed]

- 18.Shanafelt TD, Hasan O, Dyrbye LN, et al. Changes in Burnout and Satisfaction With Work-Life Balance in Physicians and the General US Working Population Between 2011 and 2014. Mayo Clin Proc 2015;90(12):1600-13. (In eng). 10.1016/j.mayocp.2015.08.023. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 19.Leiter MP, Maslach C. Latent burnout profiles: A new approach to understanding the burnout experience. Burnout Research. 2016;3(4):89–100. doi: 10.1016/j.burn.2016.09.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rotenstein LS, Torre M, Ramos MA, et al. Prevalence of Burnout Among Physicians: A Systematic Review. JAMA. 2018;320(11):1131–1150. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.12777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Linzer M, Poplau S. Eliminating burnout and moral injury: Bolder steps required. EClinicalMedicine. 2021;39:101090. doi: 10.1016/j.eclinm.2021.101090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dzeng E, Wachter RM. Ethics in Conflict: Moral Distress as a Root Cause of Burnout. J Gen Intern Med 2020;35(2):409-411. (In eng). 10.1007/s11606-019-05505-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 23.Mantri S, Lawson JM, Wang Z, Koenig HG. Identifying Moral Injury in Healthcare Professionals: The Moral Injury Symptom Scale-HP. J Relig Health 2020;59(5):2323-2340. (In eng). 10.1007/s10943-020-01065-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 24.Nash WP, Marino Carper TL, Mills MA, Au T, Goldsmith A, Litz BT. Psychometric evaluation of the Moral Injury Events Scale. Mil Med 2013;178(6):646-52. (In eng). 10.7205/milmed-d-13-00017. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 25.Amsalem D, Lazarov A, Markowitz JC, et al. Psychiatric symptoms and moral injury among US healthcare workers in the COVID-19 era. BMC Psychiatry 2021;21(1):546. (In eng). 10.1186/s12888-021-03565-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 26.Kinghorn W. Challenging the Hegemony of the Symptom: Reclaiming Context in PTSD and Moral Injury. J Med Philos. 2020;45(6):644–662. doi: 10.1093/jmp/jhaa023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Farnsworth JK, Drescher KD, Evans W, Walser RD. A functional approach to understanding and treating military-related moral injury. J Contextual Behav Sci. 2017;6(4):391–397. doi: 10.1016/j.jcbs.2017.07.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tessman L. Moral distress in health care: when is it fitting? Med Health Care Philos 2020;23(2):165-177. (In eng). 10.1007/s11019-020-09942-7. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 29.Cahill JM, Kinghorn W, Dugdale L. Repairing moral injury takes a team: what clinicians can learn from combat veterans. J Med Ethics 2022 (In eng). 10.1136/medethics-2022-108163. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 30.Rushton CH. Cultivating Moral Resilience. Am J Nurs. 2017;117(2 Suppl 1):S11–s15. doi: 10.1097/01.Naj.0000512205.93596.00. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Corley MC, Minick P, Elswick RK, Jacobs M. Nurse moral distress and ethical work environment. Nurs Ethics. 2005;12(4):381–90. doi: 10.1191/0969733005ne809oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Boyle P . Hospitals innovate amid dire nursing shortages. https://www.aamc.org/news-insights/hospitals-innovate-amid-dire-nursing-shortages. Updated 7 September 2021.

- 33.Linzer M, Manwell LB, Williams ES, et al. Working conditions in primary care: physician reactions and care quality. Ann Intern Med 2009;151(1):28-36, w6-9. (In eng). 10.7326/0003-4819-151-1-200907070-00006. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 34.NORC at the University of Chicago. Surveys of Trust in the US Healthcare System. https://www.norc.org/PDFs/ABIM%20Foundation/20210520_NORC_ABIM_Foundation_Trust%20in%20Healthcare_Part%201.pdf. Updated 21 May 2021.

- 35.Hoert J, Herd AM, Hambrick M. The Role of Leadership Support for Health Promotion in Employee Wellness Program Participation, Perceived Job Stress, and Health Behaviors. Am J Health Prom. 2016;32(4):1054–1061. doi: 10.1177/0890117116677798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sangal RB, Bray A, Reid E, et al. Leadership communication, stress, and burnout among frontline emergency department staff amid the COVID-19 pandemic: A mixed methods approach. Healthc (Amst) 2021;9(4):100577. (In eng). 10.1016/j.hjdsi.2021.100577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 37.Albott CS, Wozniak JR, McGlinch BP, Wall MH, Gold BS, Vinogradov S. Battle Buddies: Rapid Deployment of a Psychological Resilience Intervention for Health Care Workers During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Anesthesia & Analgesia. 2020;131(1):43–54. doi: 10.1213/ane.0000000000004912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lown BA, Manning CF. The Schwartz Center Rounds: evaluation of an interdisciplinary approach to enhancing patient-centered communication, teamwork, and provider support. Acad Med 2010;85(6):1073-81. (In eng). 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181dbf741. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 39.Helft PR, Bledsoe PD, Hancock M, Wocial LD. Facilitated ethics conversations: a novel program for managing moral distress in bedside nursing staff. JONAS Healthc Law Ethics Regul 2009;11(1):27-33. (In eng). 10.1097/NHL.0b013e31819a787e. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 40.Dudzinski DM. Navigating moral distress using the moral distress map. J Med Ethics 2016;42(5):321-4. (In eng). 10.1136/medethics-2015-103156. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 41.Carey LB, Hodgson TJ. Chaplaincy, Spiritual Care and Moral Injury: Considerations Regarding Screening and Treatment. Frontiers in Psychiatry 2018;9 (Original Research) (In English). 10.3389/fpsyt.2018.00619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 42.“Caring for Our ‘Wounded Healers’.” Kettering Health (blog). https://ketteringhealth.org/caring-for-our-wounded-healers/. Updated 12 November 2021.

- 43.United States. Public Health Service. Office of the Surgeon General. “Addressing Health Worker Burnout: The U.S. Surgeon General’s Advisory on Building a Thriving Health Workforce.” https://www.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/health-worker-wellbeing-advisory.pdf Updated 2022.

- 44.Maslach C, Jackson SE, Leiter MP. Maslach Burnout Inventory (3rd ed.). 1996.