PURPOSE:

Despite an increase in the number of physician assistants (PAs) in the oncology workforce, their potential to meet anticipated demand for oncology services may be hindered by high rates of burnout. The aim of this study was to examine the association between organizational context (OC) and burnout among oncology PAs to better understand factors associated with burnout.

METHODS:

A national survey of oncology PAs was conducted to explore relationships between burnout and the OC in which the PA practiced. The Areas of Worklife Survey (AWS) assessed OC by examining six key workplace qualities (workload, control, reward, community, fairness, and values). Burnout was assessed using the Maslach Burnout Inventory.

RESULTS:

PAs demonstrating burnout scored significantly lower across all domains of the AWS than those without burnout (P < .001 for each AWS subscale). The median score for each domain of the AWS and burnout (No v Yes) were as follows: workload (3.33 v 2.67), control (3.67 v 3.00), reward (4.00 v 3.67), community (4.00 v 3.67), fairness (3.33 v 2.67), and values (4.00 v 3.33). Multivariable analysis found that mismatches between the PA and their work environment in workload (odds ratio [OR] = 1.99; 95% CI, 1.32 to 3.02; P = .001), reward (OR = 1.89, 95% CI, 1.18 to 3.02; P = .008), and values (OR = 2.25; 95% CI, 1.31 to 3.88; P = .003) were more likely to report burnout. Differences in burnout in the context of workload were not explained by patient volume, practice structure, or professional autonomy.

CONCLUSION:

Workload, reward, and values were associated with greater odds of burnout, with workload being the most common mismatch in job fit. Sustainable workloads and consistency in rewards (financial, institutional, and social) for oncology PAs should be an employer's focus to help mitigate their risk of burnout.

INTRODUCTION

Physician assistants (PAs) and advanced practice registered nurses, collectively referred to as advanced practice providers (APPs), are instrumental members of the health care team and provide quality care to patients with cancer. As a result of their education and training, APPs provide a wide variety of specialized patient care services in various oncology subspecialties across the entire continuum of cancer care.1 The value of APPs to the oncology health care team is reflected by their contributions to practice efficiency, patient satisfaction, and the professional satisfaction of their collaborating physicians.2 As a result, there has been a significant increase in the employment of APPs in oncology practices to help mitigate the projected shortage of oncologists in the near future.3,4

Despite the growing number of APPs in the oncology workforce, their capacity to meet the anticipated demand for oncology care may be hindered by practice limitations imposed by federal and state laws and regulations, facility policy, and influence of employers and physicians on the APP practice model. Another potential barrier is the high rate of burnout reported by oncology APPs. In 2015, the rate of burnout reported among oncology advanced practice registered nurses was 31.3% and was slightly higher for oncology PAs at 34.8%.5,6 More recently, a significant increase in the rate of burnout for oncology PAs was identified with almost half reporting at least one symptom of burnout.7 As a result of burnout, APPs may be more likely to reduce their work hours and to leave the specialty of oncology or their profession in general.8 It is therefore vital to have a better understanding of the prevalence of burnout and its origins in the oncology APP workforce and factors related to burnout that may affect future workforce projections.

The current study was designed to explore the organizational context (OC) in which the oncology PA practices and its association with burnout. The conceptual framework for this study is based on the bidirectional relationships between OC, team context, and the team member.9 In this model, greater impact and influence is from the organization level onto the team, and then the individual (Appendix Fig A1, online only). Oncology PAs may be more susceptible to organizational factors increasing their risk of burnout as their clinical role is established at the system level and then further refined at the practice level. PAs may have limited influence at these levels leading to imbalances in their perception of job fit, a greater feeling that they are working below their level of education and training, and a more acute sense of decreased efficiency in team-based care.10,11 This conceptual framework also has important implications when exploring how teamwork affects the risk of burnout, and it aligns with current concepts for promoting provider well-being which focus on system level solutions as the primary driver of burnout.12 Moreover, the collaborative practice between physicians and PAs working in a shared practice environment can be easily explored within this context-based paradigm.

The impact of OC has been investigated in regard to how it can influence the intention of oncology nurse practitioners to leave their profession.5 But to our knowledge, the association between OC and burnout has not previously been reported for APPs. Herein, we report a cross-sectional analysis of burnout among oncology PAs as part of a larger longitudinal study of provider well-being and career satisfaction.

METHODS

Oncology PAs from the 2019 membership database of the Association of Physician Assistants in the Oncology were contacted to participate in a study on provider well-being and collaborative practice as previously reported.13 Survey invitations were sent electronically using the research electronic data capture web-based survey platform. After providing electronic informed consent, all participants were invited to complete the full-length survey with three weekly reminder e-mails sent to potential participants who had not completed the full-length survey. Participants who completed this survey were offered a gift card of $10 in US dollars in appreciation for their time spent completing the survey. PAs who did not complete the full-length survey were invited to complete a brief survey to assess for response bias. The study was approved by the Fox Chase Cancer Center Institutional Review Board.

Full-Length and Brief Survey

The full-length survey included 74 items in total to assess personal and professional characteristics (eight items), collaborative practice information (four items), collaborative physician relationship (three items), team structure, organization structure, and context (37 items), and burnout (22 items). The brief survey included six items that assessed age, sex, area of clinical practice, subspecialty, and a validated two-item assessment of burnout.14,15

Burnout

Burnout was the primary end point of this study and was assessed using the Maslach Burnout Inventory (MBI), considered the gold standard for the assessment of burnout. The MBI is a 22-item psychometric tool that includes the three domains of burnout: emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, and sense of personal accomplishment. Each subscale includes multiple questions for which participants report the frequencies of each item on a 7-point Likert scale (never, a few times a year or less, once a month or less, a few times a month, once a week, a few times a week, or every day). For each participant, total scores for each subscale were calculated and categorized as low, medium, or high on the basis of cut scores established by the MBI manual.16 Consistent with prior research, we defined professional burnout as a high score on the emotional exhaustion (score ≥ 27) and/or depersonalization (score ≥ 10) subscale.6,17-19 High scores on either of these subscales is concerning and has been associated with decreased quality of patient care by health care providers.20

OC

The Areas of Worklife Survey (AWS) was used to evaluate the association between burnout and the OC in which the oncology PA practiced. The AWS is based on the theoretical framework that suggests the greater the imbalance between the employee's perceptions of their work environment, the greater their risk of burnout. The model suggests that as the lack of congruence between the person and their job environment increases, there is a resultant increase in their risk of exhaustion, cynicism, and burnout. The six subscales the model includes are workload (the amount of work to be done in a given time), control (the opportunity to make choices and decisions, to solve problems, and to contribute to the fulfillment of responsibilities), reward (financial and social, for contributions on the job), community (the quality of an organization's social environment), fairness (the extent to which the organization has consistent and equitable rules for everyone), and values (what is important to the organization and to its members).

The short 18-item version of the AWS is reported for this study as opposed to the longer 28-item version. The short version maintains factor structure and can be used when participants have a large number of items to complete for a survey. Participants reported their level of agreement for each item in the AWS on a 5-point Likert scale, with the highest level of agreement (strongly agree) given a score of 5 and the lowest level of agreement (strongly disagree) given a score of 1. A score of 3 was chosen when it was hard to decide. Each subscale is given an overall score that represents the average of three items in a given domain. Cut scores were used to establish level of job fit for each domain consistent with prior studies.21,22 A mismatch between the person and their work environment for each domain was defined by a subscale score < 3.0, whereas a high level of congruence with the work environment was defined by a subscale score > 3.0. A subscale score = 3 was categorized as unable to decide.

Statistical Analysis

Standard descriptive statistics were used to describe the personal and professional characteristics of the oncology PAs. To assess associations by burnout status, chi square tests and Fisher's exact tests were used for categorical variables, and Wilcoxon rank sum test was used for continuous variables. Multivariable analysis was performed using logistic regression to identify independent variables associated with burnout; associations are presented as odds ratios (ORs) with 95% CIs. Statistical analyses were performed by using SAS, version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

RESULTS

Out of 917 oncology PAs invited to participate in the study, 342 PAs consented to participate for an overall response rate of 37.3%. Full-length surveys were completed by 234 PAs and are included in the full analysis (24.9%). An additional 85 participants completed the brief survey. Twenty-three incomplete surveys were excluded from the analysis.

The mean age of the participants was 40.3 years and they were more often female (86.3%) and married (78.2%). In regard to professional practice, participants reported a median of 10 years in clinical practice as an oncology PA and were more commonly working in the outpatient setting (67.1%). The most frequently reported practice setting was an Academic Medical Center (59.8%) with private practice (33.7%) and Veteran's Administration or other setting (6.4%) reported less often. The most common subspecialty of participants was medical oncology (70.5%) followed by surgical oncology (16.7%), radiation oncology (5.1%), or other (7.7%; Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Personal and Professional Characteristics of Full Length and Brief Survey Participants

Out of the 85 participants who completed at least part of the brief survey, 66 PAs reported their clinical practice was in oncology. Five participants (5.9%) were no longer in clinical practice and 12 participants (14.1%) identified that their principal area of clinical practice was now outside the field of oncology. There was no difference reported in female sex (83.3% v 86.3%; P = .54), age (41.9 v 40.3; P = .25), or subspecialty (P = .86) for participants who completed the brief or full-length survey.

OC and Burnout

Burnout rates for PAs in 2019 were presented in a prior report that compared the rate of burnout in 2019 to the rate from 2015. In brief, 48.7% of oncology PAs were considered to be burned out with a high score on the emotional exhaustion or depersonalization subscale. Emotional exhaustion was the most common symptom that contributed to burnout with 43.6% of PAs reporting a high level of emotional exhaustion. High levels of depersonalization were reported by 22.2% of PAs and a low sense of personal accomplishment by 12.9%. For the current study, we also assessed for potential response bias by comparing the rate of burnout for the participants who completed the brief survey versus the full-length survey. There was no significant difference in the overall rate of burnout on the basis of the previously validated two-item assessment (38.9% v 27.3%; P = .083) or the contribution of emotional exhaustion and/or depersonalization to the overall rate of burnout (P = .083).

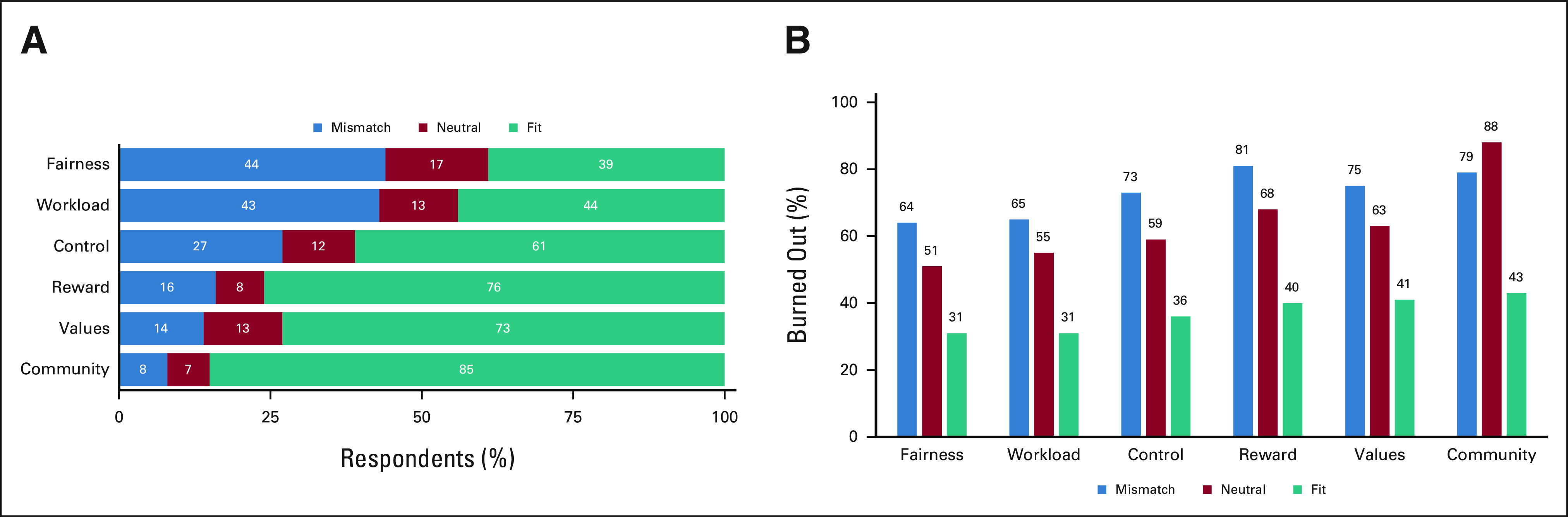

In the current study, PAs who were burned out scored significantly lower across all domains of the AWS compared with those who were not burned out (Wilcoxon test, P < .001 for each scale; Appendix Table A1, online only). The median score for each domain of the AWS when burnout is absent or present are as follows: workload (3.33 v 2.67), control (3.67 v 3.00), reward (4.00 v 3.674), community (4.00 v 3.67), fairness (3.33 v 2.67), and values (4.00 v 3.33). Using established cut scores, fairness and workload were the most common mismatch in job fit, reported by 44.4% and 42.7% of Pas, respectively. PAs reported congruency with job fit most commonly for the community (85.0%) and values (73.5%) domains. Rates of burnout for each domain of the AWS were significantly higher for PAs who reported a mismatch in job fit for a given domain (each scale; chi square P < .001 and trend test P < .001 for all domains). Burnout rates exceeded 60% for every subscale of the AWS when a mismatch in job fit was present, with the highest rates reported for the community and values domains where 78.9% and 75.0% of PAs, respectively, reported at least one symptom of burnout. The largest difference in the rate of burnout between PAs with a job fit compared with PAs with a job mismatch was found in the control (36.4% in job fit v 72.6% in mismatch) and reward (36.4% v 72.6%) domains (Figure 1).

FIG 1.

(A) The distribution of job fit among oncology PAs for each subscale of the AWS. For each subscale, fit = AWS score > 3, neutral = AWS score = 3, and mismatch = AWS score < 3. (B) The rate of burnout among oncology PAs for each subscale of the AWS survey. For each organizational factor, the rate of burnout is significantly higher when the oncology PA has a perceived mismatch in job fit. Chi square P < .001 for all subscales. AWS, Areas of Worklife Survey; PA, physician assistant.

Workload, Collaborative Practice, and Burnout

To assess the association between the AWS workload domain and burnout, we examined patient care volume of oncology PAs and found the total number of patients seen per week were similar for all PAs with or without the presence of burnout (median 45 v 40; P = .23). When examined by subspecialty, there was no difference in the median number of patients seen per week for PAs who reported burnout compared with those who did not for medical oncology (43 v 49; P = .82), surgical oncology (35 v 25; P = .64), or radiation oncology (30 v 45; P = .40). However, the small sample sizes for surgical oncology (n = 39) and radiation oncology (n = 13) limit the power to detect a difference for those specialties (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Collaborative Practice Model Structure and Support, Workload, and Burnout

In addition, the percentage of patients seen independently out of the total number of patients seen per week (independent and shared visits with the collaborating attending) were examined as a measure of clinical autonomy. Overall, oncology PAs with burnout reported seeing 60.1% of patients independently, which is similar to the 61.6% patients reported to have been seen independently by PAs who were not burned out (P = .98). There was a significant difference in the percentage of patients seen independently by specialty, with the highest percentage in medical oncology (65.5%), followed by other subspecialties (62.8%), radiation oncology (48.7%), and surgical oncology (44.0%); P = .004. A difference in visit autonomy for each subspecialty on the basis of the presence or absence of burnout was not found; medical oncology (65.6 v 65.4; P = .73), other subspecialties (54.6 v 68.0; P = .35), radiation oncology (22.2 v 51.1; P = .40), and surgical oncology (37.3 v 49.7; P = .20), again, possibly influenced by the small sample size.

Overall, satisfaction with working in a collaborative practice model was common, with 88.5% of PAs reporting being highly satisfied or satisfied working with their collaborative physicians, with only 8.5% neutral and 3.0% dissatisfied. A significantly lower rate of burnout was seen with a higher rate of satisfaction with the collaborative practice model (trend test P < .001). PAs who were neutral or dissatisfied with the model had significantly higher rates of burnout (71.4% and 80.0%, respectively) compared with PAs who were highly satisfied or satisfied (53.5% and 37.0%, respectively). Similarly, more time spent by PAs practicing at the top of their education and experience was associated with lower rates of burnout. When PAs spent 75% or more of their time working at the top of the education and experience, the rate of burnout was 43.4%; however, the rate increased to 56.7% for PAs spending < 75% of their time. Finally, characteristics of the practice model and structure were examined to identify potential factors associated with burnout. There was no difference in the rate of burnout for oncology PAs on the basis of working exclusively with specific physician(s) or all of the practices' physicians, or the number of attending physicians the PA directly worked with, or the continuity in the working relationship with nurses and medical assistants (Table 3).

TABLE 3.

Predictors of PA Burnout

Multivariable Analysis

To identify variables associated with burnout, univariate models were performed with all variables, the AWS variables alone, and with all non-AWS variables. The number of hours worked per week, perception of fairness in compensation, quality of the relationship with the collaborating physician, percentage of time spent on direct and indirect patient care, and all six domains of the AWS were associated with an increased odds of burnout when all variables were included. In the model with only AWS variables, the odds of burnout were independently associated with burnout for the workload, reward, and values domain. In the final multivariate model, the association between workload and burnout remained significant with nearly a 100% increase in the odds of burnout associated with a lack of job fit for the workload domain (OR for burnout = 1.99, P = .001). Similarly, a lower degree of congruence between the PA and the reward and values domains was associated with increased odds of burnout in the multivariable model (reward OR = 1.89, P = .008 and value OR = 2.25, P = .003). Finally, a 10% increase in the amount of time spent on indirect patient care was associated with 29% increase in the odds of burnout (OR = 1.29, P = .021; Table 3). The number of hours worked per week and the relationship with the collaborating physician were not associated with burnout in the final model.

DISCUSSION

Burnout among oncology PAs poses a threat to the delivery of quality care to patients with cancer and may affect the health care workforce's capacity to meet the anticipated increase in demand for oncologic services. The current study significantly contributes to our understanding of oncology PA burnout and work engagement and demonstrates associations between burnout and oncology PAs' perceptions of work setting qualities as assessed by the AWS. Consistent with the theoretical framework, when there is a mismatch in the oncology PAs' perception of the OC (ie, lack of job fit), the rate of burnout is significantly increased. Fairness and workload were the most commonly reported mismatches in job fit, reported by over 40% of oncology PAs with associated rates of burnout of 64% and 65%, respectively. Workplace qualities independently associated with burnout included the domains of workload, reward, and values.

The results from this study have several implications for administrative and clinical leaders at organizations that employ APPs in oncology and the future oncology workforce. As organizations explore opportunities to increase oncology PA engagement, workload may be an area to focus specific attention. In the current study, a mismatch in perceived workload was both common among oncology PAs and associated with high rates of burnout. For these overextended groups of PAs, a focus managing the demands of the job and resources available to them may improve their work-life and promote engagement.23 It is also important to note that understanding the workload of the oncology PA extends beyond a simple assessment of performance metrics such as patient volume or relative value units that are commonplace in many health care settings. For example, in the current study, there was no statistical difference in the number of patients seen by PAs with or without burnout. This is not entirely surprising as the value of oncology APPs is not defined by productivity metrics alone as their role incorporates numerous aspects of patient care that are not always directly linked to a patient visit or relative value unit.4,24 Similarly, in a prior study of APP collaborative practice, there was no association between an APP's perceived workload and objective measurements of productivity when assessed by number of patient visits.2 One strategy for organizations to better understand and enhance the workload of oncology PAs may be with intermittent time and effort studies in which PAs self-report their professional effort over a defined period. When this strategy was executed at a large academic medical center, opportunities to reduce underutilization and enhance the role of the oncology PA were identified.25 Time and effort studies when approached as a process improvement exercise may also help to improve practice efficiency and increase the overall value of PAs as members of team-based oncology care. Furthermore, by creating a more sustainable workload, oncology PAs may be able to refine or expand clinical skills or explore additional professional development opportunities.

Our study also found that lower rates of burnout were observed when PAs work at the top of their degree and training, and also when they are satisfied with their collaborative practice model. With the anticipated increase in APPs employed in oncology, it will be important to ensure they are integrated into team-based care with modern collaborative practice models that focus on improved patient care and increased clinical efficiency and productivity.26 As an example, the University of North Carolina Medical Center was successful in expanding the APP role related to chemotherapy ordering through a comprehensive educational, training, and privileging process.27 Both physicians and APPs perceived the program to be beneficial and thought it streamlined the chemotherapy ordering process and improved clinical efficiency. It would appear that many centers would benefit from exploring chemotherapy privileging opportunities as a recent survey of the oncology APP workforce reported that 25% of Nurse Practitioners and 33% of PAs could not write prescriptions for chemotherapy at their practice.4 In the same survey, the most common factors that determined or affected their practice model were physician preference, employer policy, state scope of practice laws, and patient complexity. This would suggest that improvements to the collaborative practice model can be made at the local level but opportunities also exist at the state and national levels to remove barriers that prevent APPs in oncology from practicing at the top of their degree and training.

It is important to recognize potential limitations of the study. Although the response rate for this study is similar to or exceeds the rates of other studies of PA burnout, it is possible the study may be limited by response bias. We explored this possibility and found that there was no difference in age, sex, subspecialty, or the overall rate of burnout for PAs who completed the full-length survey compared with PAs who did not respond to the initial survey invitations and only completed the brief survey. Our findings are consistent with other studies of health care providers that have failed to identify differences in responding and nonresponding providers in research studies.28 The professional characteristics of the participants in this study were also similar with respect to age, sex, hours worked, and number of patients seen per week to oncology PAs in the 2019 specialty profile of certified PAs from the National Commission on Certification of Physician Assistants.29 This would suggest that the current study cohort is representative of the oncology PA at large. However, the study was underpowered to detect small differences within the surgical and radiation oncology subspecialties, which is a limitation of the study. Finally, although workload was identified as a significant factor associated with PA burnout, the current study focused on the demand and resource aspects of workload but did not examine the opportunities and options for PAs to recover from chronic work overload and restore or maintain balance in job-related stress.

In conclusion, the rate of burnout among oncology PAs is compelling and may have significant implications in meeting the future demand for oncology services. Workload, reward, and value domains of OC were associated with burnout, with workload being the most common mismatch in job fit. Organizations that maintain a sustainable workload within modern collaborative practice models are likely to increase the engagement of oncology PAs and reduce their risk of burnout. Finally, additional research is warranted to better understand the attributes of rewards and recognition for oncology PAs that increase their vulnerability to burnout.

APPENDIX

FIG A1.

The conceptual framework put forward by Kumra et al.9 The association between organizational cultural competence and teamwork climate in a network of primary care practices. Health Care Manage Rev, 2018. IMO, input-mediator-output; OC, organizational context.

TABLE A1.

AWS Domain Scores and Burnout

Eric D. Tetzlaff

Consulting or Advisory Role: Blueprint Medicines

Speakers' Bureau: Blueprint Medicines

Heather M. Hylton

This author is a member of the JCO Oncology Practice Editorial Board. Journal policy recused the author from having any role in the peer review of this manuscript.

Michael J. Hall

Research Funding: AstraZeneca

Patents, Royalties, Other Intellectual Property: I share a patent with several Fox Chase investigators for a novel method to investigate hereditary CRC genes (Inst)

Travel, Accommodations, Expenses: GRAIL

Other Relationship: Myriad Genetics, Invitae, Caris Life Sciences

No other potential conflicts of interest were reported.

DISCLAIMER

The contents of this study are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the Association of Physician Assistants in Oncology or the National Institutes of Health.

PRIOR PRESENTATION

Presented in part at the 2020 Annual Meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology.

SUPPORT

Supported by a research award from the Association of Physician Assistants in Oncology and by Fox Chase Cancer Center Core Grant Number: P30 CA006927 from the National Institutes of Health.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conception and design: Eric D. Tetzlaff, Heather M. Hylton, Zachary Hasse

Collection and assembly of data: Eric D. Tetzlaff

Data analysis and interpretation: Eric D. Tetzlaff, Heather M. Hylton, Karen J. Ruth, Zachary Hasse, Michael J. Hall

Manuscript writing: All authors

Final approval of manuscript: All authors

Accountable for all aspects of the work: All authors

AUTHORS' DISCLOSURES OF POTENTIAL CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

Association of Organizational Context, Collaborative Practice Models, and Burnout Among Physician Assistants in Oncology

The following represents disclosure information provided by authors of this manuscript. All relationships are considered compensated unless otherwise noted. Relationships are self-held unless noted. I = Immediate Family Member, Inst = My Institution. Relationships may not relate to the subject matter of this manuscript. For more information about ASCO's conflict of interest policy, please refer to www.asco.org/rwc or ascopubs.org/op/authors/author-center.

Open Payments is a public database containing information reported by companies about payments made to US-licensed physicians (Open Payments).

Eric D. Tetzlaff

Consulting or Advisory Role: Blueprint Medicines

Speakers' Bureau: Blueprint Medicines

Heather M. Hylton

This author is a member of the JCO Oncology Practice Editorial Board. Journal policy recused the author from having any role in the peer review of this manuscript.

Michael J. Hall

Research Funding: AstraZeneca

Patents, Royalties, Other Intellectual Property: I share a patent with several Fox Chase investigators for a novel method to investigate hereditary CRC genes (Inst)

Travel, Accommodations, Expenses: GRAIL

Other Relationship: Myriad Genetics, Invitae, Caris Life Sciences

No other potential conflicts of interest were reported.

REFERENCES

- 1. Reynolds RB, McCoy K. The role of Advanced Practice Providers in interdisciplinary oncology care in the United States. Chin Clin Oncol. 2016;5:44. doi: 10.21037/cco.2016.05.01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Towle EL, Barr TR, Hanley A, et al. Results of the ASCO study of collaborative practice arrangements. J Oncol Pract. 2011;7:278–282. doi: 10.1200/JOP.2011.000385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Gajra ANC, Klink AJ, Yeh TC, et al. The role and scope of practice of advanced practice providers in United States community oncology. J Clin Pathw. 2020;6:36–41. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Bruinooge SS, Pickard TA, Vogel W, et al. Understanding the role of advanced practice providers in oncology in the United States. J Oncol Pract. 2018;14:e518–e532. doi: 10.1200/JOP.18.00181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Bourdeanu L, Pearl Zhou Q, DeSamper M, et al. Burnout, workplace factors, and intent to leave among hematology/oncology nurse practitioners. J Adv Pract Oncol. 2020;11:141–148. doi: 10.6004/jadpro.2020.11.2.2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Tetzlaff ED, Hylton HM, DeMora L, et al. National study of burnout and career satisfaction among physician assistants in oncology: Implications for team-based care. J Oncol Pract. 2018;14:e11–e22. doi: 10.1200/JOP.2017.025544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Tetzlaff ED, Hylton HM, Ruth K, et al. Burnout among oncology physician assistants (PAs) from 2015 to 2019. J Clin Oncol. 2020;38:11009. doi: 10.1200/OP.21.00051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Halasy MP, West CP, Shanafelt T, et al. PA job satisfaction and career plans. JAAPA. 2021;34:1–12. doi: 10.1097/01.JAA.0000750968.07814.d0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kumra T, Hsu YJ, Cheng TL, et al. The association between organizational cultural competence and teamwork climate in a network of primary care practices. Health Care Manage Rev. 2018;45:106–116. doi: 10.1097/HMR.0000000000000205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Edwards ST, Helfrich CD, Grembowski D, et al. Task delegation and burnout trade-offs among primary care providers and nurses in Veterans Affairs Patient Aligned Care Teams (VA PACTs) J Am Board Fam Med. 2018;31:83–93. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.2018.01.170083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.(CHLM) CfHLaM . PA and NP Workplace Experiences; National Summary Report. Alexandria, VA: American Academy of Physician Assistants; 2019. p. 10. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Shanafelt TD, Noseworthy JH. Executive leadership and physician well-being: Nine organizational strategies to promote engagement and reduce burnout. Mayo Clin Proc. 2017;92:129–146. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2016.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Tetzlaff ED, Hylton HM, Ruth KJ, et al. Changes in Burnout among oncology physician assistants between 2015 and 2019. JCO Oncol Pract. 2022;18:e47–e59. doi: 10.1200/OP.21.00051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. West CP, Dyrbye LN, Satele DV, et al. Concurrent validity of single-item measures of emotional exhaustion and depersonalization in burnout assessment. J Gen Intern Med. 2012;27:1445–1452. doi: 10.1007/s11606-012-2015-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. West CP, Dyrbye LN, Sloan JA, et al. Single item measures of emotional exhaustion and depersonalization are useful for assessing burnout in medical professionals. J Gen Intern Med. 2009;24:1318–1321. doi: 10.1007/s11606-009-1129-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Maslach C, Jackson S, Leiter M, et al. Maslach Burnout Inventory Manual. ed 4. Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologists Press; 1996-2018. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Dyrbye LN, Varkey P, Boone SL, et al. Physician satisfaction and burnout at different career stages. Mayo Clin Proc. 2013;88:1358–1367. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2013.07.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Shanafelt TD, Boone S, Tan L, et al. Burnout and satisfaction with work-life balance among US physicians relative to the general US population. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172:1377–1385. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2012.3199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Shanafelt TD, Gradishar WJ, Kosty M, et al. Burnout and career satisfaction among US oncologists. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32:678–686. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.51.8480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Melnick ER, Powsner SM, Shanafelt TD: In reply—Defining physician burnout, and differentiating between burnout and depression Mayo Clinic Proc 921456–1458.2017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Fiabane E, Giorgi I, Sguazzin C, et al. Work engagement and occupational stress in nurses and other healthcare workers: The role of organisational and personal factors. J Clin Nurs. 2013;22:2614–2624. doi: 10.1111/jocn.12084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Laschinger HK, Wong CA, Greco P. The impact of staff nurse empowerment on person-job fit and work engagement/burnout. Nurs Adm Q. 2006;30:358–367. doi: 10.1097/00006216-200610000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Leiter MP, Maslach C. Latent burnout profiles: A new approach to understanding the burnout experience. Burnout Res. 2016;3:89–100. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Pickard T. Calculating your worth: Understanding productivity and value. J Adv Pract Oncol. 2014;5:128–133. doi: 10.6004/jadpro.2014.5.2.6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Moote M, Nelson R, Veltkamp R, et al. Productivity assessment of physician assistants and nurse practitioners in oncology in an academic medical center. J Oncol Pract. 2012;8:167–172. doi: 10.1200/JOP.2011.000395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Shulman LN. Efficient and effective models for integrating advanced practice professionals into oncology practice. Am Soc Clin Oncol Educ Book. 2013:377–379. doi: 10.14694/EdBook_AM.2013.33.e377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Carrasquillo MA, Vest TA, Bates JS, et al. A chemotherapy privileging process for advanced practice providers at an academic medical center. J Oncol Pharm Pract. 2020;26:116–123. doi: 10.1177/1078155219846959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Kellerman SE, Herold J. Physician response to surveys: A review of the literature. Am J Prev Med. 2001;20:61–67. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(00)00258-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.National Commission on Certification of Physician Assistants I . 2019 Statistical Profile of Certified Physician Assistants: An Annual Report of the National Commission on Certification of Physician Assistants. National Commission on Certification of Physician Assistants; 2020. [Google Scholar]