Abstract

Background and study aims Gastric cancer (GC) is increasingly reported and a leading cause of death in patients with familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP). Identifying features in patients with FAP who harbor sessile gastric polyps, likely precursors to GC, may lead to alterations in endoscopic surveillance in those patients and allow endoscopic intervention to decrease the risk of GC. The aim of this study was to identify demographic and clinical factors in patients with FAP who harbor sessile gastric polyps.

Patients and methods We retrospectively compared demographic, clinical, and endoscopic features in consecutive adult patients with FAP who presented for a surveillance endoscopy at a tertiary-care center with a FAP registry who harbor sessile gastric polyps to those without them. Sessile gastric polyps included pyloric gland adenomas, gastric adenomas, hyperplastic polyps, and fundic gland polyps with high-grade dysplasia. We also display the location of germline APC pathogenic variants in patients with and without sessile gastric polyps.

Results Eighty patients with FAP were included. Their average age was 48 years and 70 % were male . Nineteen (24 %) had sessile gastric polyps. They were older ( P < 0.03), more likely to have a family history of GC ( P < 0.05), white mucosal patches in the proximal stomach ( P < 0.001), and antral polyps ( P < 0.026) compared to patients without a gastric neoplasm. No difference in Spigelman stage, extra-intestinal manifestations, or surgical history was note. 89 % of patients with a gastric neoplasm had an APC pathogenic variant 5’ to codon 1309.

Conclusions Specific demographic, endoscopic, and genotypic features are associated with patients with FAP who harbor sessile gastric polyps. We recommend heightened awareness of these factors when performing endoscopic surveillance of the stomach with resection of gastric neoplasia when identified.

Introduction

Gastric polyposis is an extra-colonic and common manifestation of familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP) 1 2 . Data demonstrate that nearly all patients with FAP have proximal gastric polyposis 3 . Historically, FAP related gastric cancer (GC) was reported to be rare 4 5 . The incidence of GC is rising in patients with FAP with one recent report demonstrating a standardized incidence ratio of 140 for gastric cancer (GC) compared to the general US population 1 . Recent data reports that GC is now the most common cause of death in patients with FAP once colectomy has been performed 6 7 .

Unfortunately, the majority of FAP-related GC cases are diagnosed at an advanced stage and survival is poor 1 2 7 . A carpeting of proximal gastric polyposis, large mounds of proximal gastric polyps, and solitary sessile proximal gastric polyps > 10 mm are associated with the development of GC and make it difficult to adequately survey the stomach. While the precursor lesion to GC in FAP has not been confirmed, observational data suggests GC most likely arises from a gastric neoplasm such as a pyloric gland adenoma, gastric adenoma, or fundic gland polyps with high-grade dysplasia. These neoplastic lesions are more prevalent in patients with FAP related GC 1 8 9 10 11 . Recent data suggest mucosal features on endoscopy can differentiate neoplastic gastric polyps from fundic gland polyps with low-grade or no dysplasia in patients with FAP with a sensitivity and specificity of 79 % and 80 %, respectively 12 .

Since FAP related GC is usually diagnosed at an advanced stage and deadly, identifying clinical and endoscopic features in patients with FAP likely to harbor sessile gastric polyps (Paris Classification Is) may alert clinicians to alter endoscopic surveillance and management. The aim of this study was to identify demographic, clinical and endoscopic factors in patients with FAP who harbor sessile gastric polyps.

Patients and methods

Patient population

Adults with FAP, without a personal history of GC, and who were part of a recently published study to develop endoscopic criteria to distinguish sessile gastric polyps in FAP based on mucosal features were included. Details regarding endoscopic protocol have previously been described. Briefly, we prospectively collected 150 polyps from consecutive patients who presented for a surveillance endoscopy at a tertiary referral center. Sessile polyps, examined under high-definition white light and narrow band imaging, were resected with the aim of developing criteria to visually assess for pathology associated with gastric cancer 12 . In this study, we retrospectively compared demographic and clinical features between patients with FAP with sessile gastric polyps to those without those lesions. Neoplastic gastric polyps include pyloric gland adenomas with or without dysplasia, gastric adenomas (tubular adenomas, gastric adenomas with intestinal features and gastric adenomas-foveolar type), hyperplastic polyps, and fundic gland polyps with high-grade dysplasia. Fundic gland polyps with low-grade or no dysplasia were classified as non-neoplastic. We also explored a genotype-phenotype correlation based on codon location of APC pathogenic variant (PV) and the presence of sessile gastric polyps. For this portion, we also retrospectively reviewed the APC PV for those with a personal history of gastric cancer who had been excluded from the demographic and clinical feature analysis.

This study was Institutional Review Board-approved and patients were part of the David G. Jagelman Inherited Colorectal Cancer Registries within the Sanford R. Weiss, MD, Center for Hereditary Colorectal Neoplasia at the Cleveland Clinic.

Variables

Demographic and clinical variables collected from the medical record include age, sex, APC PV, extra-intestinal manifestations (osteomas, desmoid tumors, congenital hypertrophy of the retinal pigment epithelium (CHRPE), thyroid nodules or cancer, sebaceous cysts, supernumerary teeth), cancer history (colon, stomach, any other), current substance use (alcohol – yes/no, tobacco – yes/no), medication use at any time (proton pump inhibitors, H 2 blockers, sulindac, and other nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs), family history (FAP, GC), total number of esophagogastroduodenoscopies, length of surveillance period, and surgical history (upper GI surgery type, lower gastrointestinal surgery type).

Endoscopic data included the location, number and size of polyps in the stomach: the presence and size of white mucosal patches (mucosal areas that appear pale compared to the surrounding mucosa of at least 1 cm in size), polypoid mounds (clusters of polyps that are at least 2 cm in size), carpeting of gastric polyposis (areas of gastric polyposis without any intervening normal mucosa), and pathology (including Helicobacter pylori status and presence of intestinal metaplasia ) . The Spigelman stage of duodenal polyposis was calculated based on the duodenal polyp number, size range, pathology, and degree of dysplasia. We included the location of APC PV of patients with FAP within our registry who developed gastric cancer for comparison. 1

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics are presented as mean ± standard deviation, median (25th, 75th percentiles) or frequency (percent). A univariable analysis was performed to assess factors associated with risk status. Analysis of variance (ANOVA) or the nonparametric Kruskal–Wallis tests were used to compare continuous variables and Pearson’s Chi-square tests were used for categorical factors.

All analyses were performed using SAS (version 9.4, The SAS Institute, Cary, North Carolina, United States) and P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Eighty patients with FAP were included. Nineteen (23.8 %) had at least one gastric neoplasm and 61 (76.3 %) did not. There were no differences in the length of the endoscopic surveillance period (8.4 vs 7.9 years, P = 0.73) or number of EGDs (7.4 vs 6, P = 0.19) between patients with and without sessile gastric polyps. The patients with sessile gastric polyps were older (53.6 years ± 3.1 vs 46.2 ± 1.7), and a larger proportion had a family history of GC (n = 4, 21.1 % vs n = 3, 4.9 %, P = 0.051), than patients without sessile gastric polyps, respectively. No other significant differences in demographics, extra-intestinal manifestations, family history, and surgical history between the two groups were noted ( Table 1 ). Extra-intestinal manifestations were not notably different between those with sessile gastric polyps and those without: desmoid tumors (10.5 vs 11.5 %, P = 0.99), osteomas (5.3 vs 16.4 %, P = 0.45), sebaceous cysts (15.8 vs 21.3 %, P = 0.75), supernumerary teeth (5.3 vs 6.6 %, P = 0.99), and CHRPE (5.3 VS 13.1 %, P = 0.68).

Table 1. Demographic and clinical features in patients with and without sessile gastric polyps.

| Total patients n = 80 (%) | Patients with gastric neoplasm N = 19 (24 %) (%) | Patients without gastric neoplasm N = 61 (76 %) (%) | P value | |

| Age (std dev) | 48 (1.5) | 53.6 (3.1) | 46.2 (1.7) | 0.03 |

| Male | 56 (70) | 14 (73.7) | 42 (68.9) | 0.69 |

| APC pathogenic variant * | 45 (256.3) | 10 (52.6) | 35 (57.4) | 0.47 |

| Family history of FAP | 48 (60) | 12 (63.2) | 36 (59) | 0.60 |

| Family history of GC | 7 (8.8) | 4 (21.1) | 3 (4.9) | 0.05 |

| Other cancer | 0.28 | |||

| Thyroid carcinoma | 1 (1.3) | 0 (0) | 1 (1.6) | |

| Renal cell cancer | 1 (1.3) | 0 (0) | 1 (1.6) | |

| Ampullary carcinoma | 2 (2.5) | 0 (0) | 2 (3.3) | 0.99 |

| Colon adenocarcinoma | 11 (13.8) | 4 (21.1) | 7 (11.5) | 0.28 |

| Barrett’s esophagus | 1 (1.3) | 1 (5.3) | 0 (0) | 0.28 |

| Any tobacco use | 14 (17.5) | 3 (15.8) | 11 (18) | 0.99 |

| Any alcohol use | 24 (30) | 5 (26.3) | 19 (31.1) | 0.78 |

| PPI | 48 (60) | 15 (78.9) | 33 (54.1) | 0.06 |

| H 2 | 8 (10) | 2 (10.5) | 6 (9.8) | 0.99 |

| NSAID | 20 (25) | 8 (42.1) | 12 (19.7) | 0.07 |

| Sulindac | 18 (22.5) | 4 (21.1) | 14 (23) | 0.99 |

| Upper GI surgery | 11 (13.8) | 3 (15.9) | 7 (11.5) | 0.44 |

| Pylorus-preserving duodenectomy | 6 (7.5) | 1 (5.3) | 5 (8.2) | |

| Whipple | 1 (1.3) | 1 (5.3) | 0 (0) | |

| Bilroth I | 1 (1.3) | 0 (0) | 1 (1.6) | |

| Bilroth II | 2 (2.5) | 1 (5.3) | 1 (1.6) | |

| Partial duodenectomy | 1 (1.3) | 0 (0) | 1 (1.6) | |

| Colon surgery (IPAA, IRA, EI) | 70 (87.5) | 53 (86.9) | 17 (89.5) | 0.99 |

FAP, familial adenomatous polyposis; GC, gastric cancer; PPI, proton pump inhibitor; NSAID, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug; GI, gastrointestinal; IPAA, ileal pouch-anal anastomosis; IRA, ileorectal anastomosis; EI, endo ileostomy .

Only if data available on pathogenic variant in individual.

On endoscopy, no differences in the location by number or size of gastric polyps were noted. A carpeting of gastric polyps was similarly noted (26.3 % vs 18 %-19.7 %) in both groups. Compared to patients without sessile gastric polyps, white mucosal patches in the cardia and fundus (n = 6, 31.6 % vs n = 1, 1.6%, P = 0.001) and gastric body (n = 3, 15.8 vs n = 0, 0 %, P = 0.012), and antral polyps irrespective neoplasm location (n = 4, 21.1 % vs n = 2, 3.3 %, P = 0.026) were more common in patients with sessile gastric polyps. H. pylori , intestinal metaplasia, or autoimmune gastritis was not found in any of the specimens. The Spigelman stage of duodenal polyposis did not differ between patient groups ( Table 2 ).

Table 2. Endoscopic features in patients with and without sessile gastric polyps.

| Total Patients N = 80 (%) | Patients With Gastric Neoplasm N = 19 (24 %) | Patients Without Gastric Neoplasm N = 61 (76 %) | P value | |

| Fundus/cardia | ||||

| Polyps present | 77 (96.3) | 18 (94.7) | 59 (96.7) | 0.56 |

| # of polyps | 0.51 | |||

|

4 (5) | 0 (0) | 4 (6.6) | |

|

12 (15) | 4 (21.1) | 8 (13.1) | |

|

9 (11.3) | 2 (10.5) | 7 (11.5) | |

|

18 (22.5) | 2 (10.5) | 16 (26.2) | |

|

34 (42.5) | 10 (52.6) | 24 (39.3) | |

| Polyp Size | 0.92 | |||

|

58 (72.5) | 15 (78.9) | 43 (70.5) | |

|

16 (20) | 3 (15.8) | 13 (21.3) | |

|

1 (1.3) | 0 (0) | 1 (1.6) | |

| Carpeting | 17 (21.3) | 5 (26.3) | 12 (19.7) | 0.53 |

| Polypoid mounds | 3 (3.8) | 1 (5.3) | 2 (3.3) | 0.56 |

| White mucosal patch | 7 (8.8) | 6 (31.6) | 1 (1.6) | 0.001 |

| Body | ||||

| Polyps present | 75 (93.8) | 18 (94.7) | 57 (93.4) | 0.99 |

| Number of polyps | 0.86 | |||

|

5 (6.3) | 1 (5.3) | 4 (6.6) | |

|

12 (15) | 4 (21.1) | 8 (13.1) | |

|

9 (11.3) | 2 (10.5) | 7 (11.5) | |

|

16 (20) | 2 (10.5) | 14 (23) | |

|

33 (41.3) | 9 (47.4) | 24 (39.3) | |

| Polyp size | 0.72 | |||

|

55 (68.8) | 15 (78.9) | 40 (65.6) | |

|

17 (21.3) | 3 (15.8) | 14 (23) | |

|

1 (1.3) | 0 (0) | 1 (1.6) | |

| Carpeting | 16 (20) | 5 (26.3) | 11 (18) | 0.43 |

| Mounds | 4 (5) | 2 (10.5) | 2 (3.3) | 0.24 |

| White mucosal patch | 3 (3.8) | 3 (15.8) | 0 (0) | 0.01 |

| Antrum | ||||

| Polyps present | 6 (7.5) | 4 (21.1) | 2 (3.3) | 0.03 |

| Number of polyps | ||||

|

74 (92.5) | 59 (96.7) | 15 (78.9) | 0.02 |

|

4 (5.0) | 2 (3.3) | 2 (10.5) | |

|

2 (2.5) | 0 (0) | 2 (10.5) | |

| Polyp size | 0.01 | |||

|

4 (5) | 2 (10.5) | 2 (3.3) | |

|

2 (2.5) | 2 (10.5) | 0 (0) | |

| Mounds | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0.99 |

| White mucosal patch | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0.99 |

| Duodenum | ||||

| Number of duodenal polyps | ||||

|

21 (26.3) | 4 (21.1) | 17 (27.9) | 0.74 |

|

14 (17.5) | 4 (21.1) | 10 (16.4) | |

|

24 (30) | 8 (42.1) | 16 (26.2) | |

|

18 (22.5) | 3 (15.8) | 15 (24.6) | |

| Sizes of polyps in duodenum | 0.82 | |||

|

21 (26.3) | 4 (21.1) | 17 (27.9) | |

|

25 (31.3) | 8 (42.1) | 17 (27.9) | |

|

20 (25) | 5 (26.3) | 15 (24.6) | |

|

12 (15) | 2 (10.5) | 10 (16.4) | |

| Spigelman stage | 0.68 | |||

|

2 (10.5) | 0 (0) | 2 (10.5) | |

|

27 (33.8) | 7 (36.8) | 20 (32.8) | |

|

32 (40) | 9 (47.4) | 23 (37.7) | |

|

16 (20) | 2 (10.5) | 14 (23) | |

|

3 (6.3) | 1 (5.2) | 2 (4.9) | |

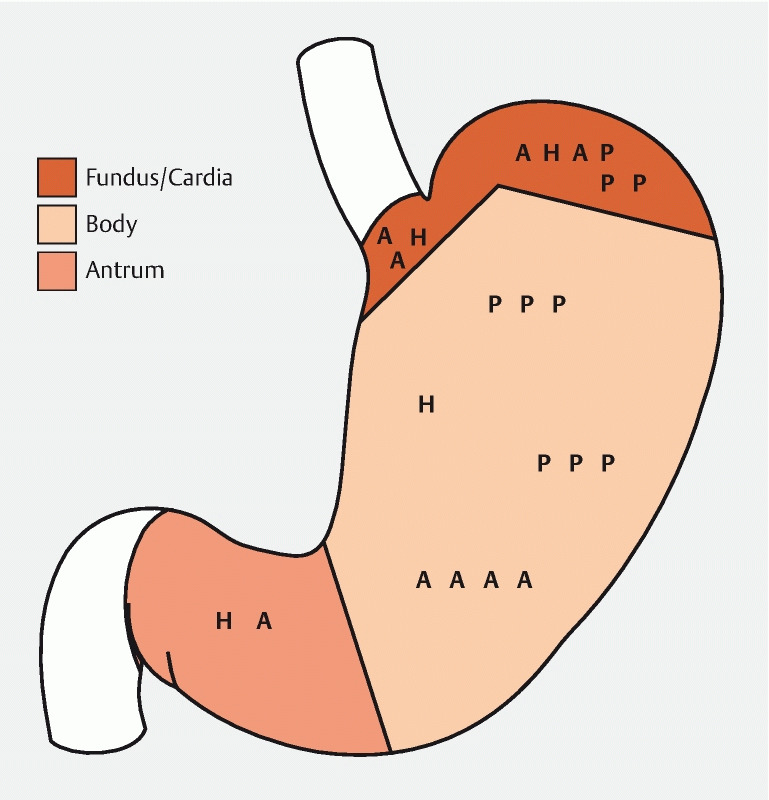

Pyloric gland adenomas were most often located in the cardia and fundus, followed by the body, with none in the antrum while hyperplastic polyps were distributed evenly throughout the stomach ( Fig. 1 ). The body contained polyps of all histologic types and only two (hyperplastic polyp and gastric adenoma) of the twenty-two resected sessile gastric polyps were located in the antrum.

Fig. 1.

Distribution of the twenty-two resected gastric neoplastic polyps by histology. A, gastric adenoma; P, pyloric gland adenoma; H, hyperplastic polyp.

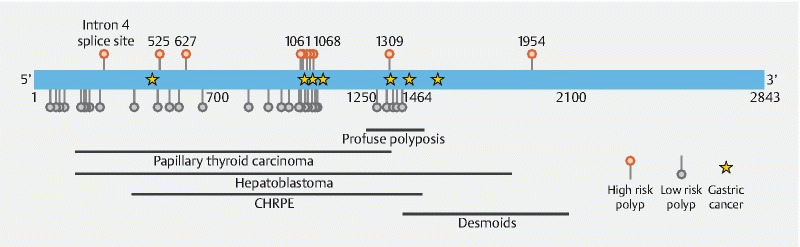

Eighteen of nineteen patients with sessile gastric polyps had a PV at or 5’ to codon 1309 with a clustering of APC pathogenic variants between codon 1061–1068 ( Fig. 2 ) representing a typical distribution of mutations in FAP. Six of seven GC patients with known pathogenic variants had APC mutations at or 5’ to codon 1328, with three clustered between codon 1060–1150. Five patients with gastric cancer or sessile gastric polyps had APC 3182del5 or 3183del5 pathogenic variants. Those without a gastric neoplasm had PV distributed between codon 1 and 1464 ( Table 3 ).

Fig. 2.

Representation of the APC gene: Numbers in black represent codons; circles represent location of APC pathogenic variants in patients with sessile gastric polyps (orange) and patients without them (gray) patients. Stars represent APC PV of the seven of eleven patients with FAP related GCs in our registry (not part of this study) for which patient pathogenic variant details are available.

Table 3. APC pathogenic variants based on nucleotide position in patients based on neoplastic polyp pathology as well as in gastric cancer cases.

| Mutations associated with GC 1 (n 2 = 7/11) | Mutations associated with HP (n 2 = 4/4) | Mutations associated with GA (n 2 = 4/10) | Mutations associated with PGA (n 2 = 2/5) |

| 453delA 3182del5 1495C > T 3202del4 4350delA Q1328X 4733_4734delGT | 3183del5 3183del5 3202del4 3927_3931delAAAGA | IVS4 + G > A 3183del5 3183del5 5860_5863delTTTG | 1873 C > T 1875_1878delGACA |

GC, gastric cancer.

GC cases and pathogenic variants from another study (Mankaney, Leonne)

Patients with a pathogenic variant / total number of patients with respective pathology.

Discussion

All patients with FAP develop gastric polyposis and are at an increased risk for GC compared to the general population 1 13 14 . A recent publication from a US polyposis registry observed that GC is the leading cause of death in FAP and attenuated FAP. GC cases are likely increasing as risk-reducing colorectal surgery and post-surgical lower endoscopic surveillance have decreased early deaths from colorectal cancer 7 . Reasons other than increasing age of the FAP population – attributed to improved colorectal and duodenal cancer prevention – for this relatively recent GC occurrence in Western FAP populations remain unclear 1 6 . Case control and observational studies on FAP related GC have established risk factors associated with cancer but have not explored risk factors for sessile gastric polyps, the precursor to GC. Prior to or concurrently with GC diagnosis, endoscopic features including a carpeting of proximal gastric polyposis, proximal polypoid mounds of polyps, and white mucosal patches are commonly seen, which make it difficult to survey the stomach for neoplastic lesions 1 8 9 . Criteria that utilize mucosal features to differentiate neoplastic from non-neoplastic polyps on endoscopy have been developed 12 . Endoscopists who perform upper endoscopic surveillance in FAP should be familiar with high-risk clinical and endoscopic features and able to identify and resect sessile gastric polyps prior to GC or provide endoscopic management to debulk proximal polyposis when the stomach becomes difficult to survey. Recommended surveillance intervals as well as additional surveillance strategies include abdominal imaging if concerning history is found and EGD intervals ranging from 3 months to a year, which discussion for gastrectomy in those with advanced disease 1 .

We noted that patients with FAP with sessile gastric polyps were older in age, more likely to have a family history of GC, have white mucosal patches in the proximal stomach, and antral polyps irrespective of gastric neoplasm location. The average age at detection of sessile gastric polyps in this study, a prior Cleveland clinic study, and at St. Mark’s was 54, 46.5, and 44 years, respectively 1 2 . The average age of GC our prior study, in the St. Mark’s, our prior study, and the Utah registry was 57, 58, and 52.3 years respectively 1 2 13 . The 10-year window between the age of gastric neoplasm detection and GC in these Western FAP populations provides a window for heightened surveillance and endoscopic management. We hypothesize a phenotypic shift occurs in the late 40 s or early 50 s possibly due to age or medication related change in the microbiome and unidentified environmental risk factors in those with an APC gene predisposition to GC. Earlier data from 30 years ago demonstrated similar rates of GC between the FAP and general population which is not the case at this time with a standardized incidence rate of 140 15 . Shibata noted that FAP related GC in Japanese patients occur two decades after colectomy, similar to our findings 8 13 . The intestinal microbiota impacts oncogenesis), and patients with an APC PV have gut microbial compositional differences that predispose to colorectal cancer 16 17 . Interestingly, the GC risk factor H. pylori has a low prevalence rate when polyposis is present in FAP 3 . None of our patients were found to have H. pylori.

The endoscopic finding of white mucosal patches was seen in nearly a third of patients with sessile gastric polyps and in only 1.6 % of patients without them. This finding corroborates the results of an earlier study in which stomachs with white mucosal patches harbored high-risk gastric pathology within and outside of the patch 9 . In our experience the patches tend to be large, and most often in the fundus. We found antral polyps in one in five patients with sessile gastric polyps but only in 3 % of patients without them. We also did not note any difference in polyp size between the two groups while previous studies have demonstrated a correlation between polyp size and gastric cancer or dysplasia in fundic gland polyps 3 8 . This suggests that other endoscopic criteria need to be applied in identifying sessile gastric polyps especially when < 1 cm and before gastric cancer presents 12 .

We found most APC PV from our patients with gastric cancer and sessile gastric polyps were located 5’ of codon 1328 with a clustering between codon 1061–1150. Given the descriptive nature of these findings, as well as distribution typical of APC pathogenic variants in FAP, we are unable to draw any genotype-phenotype associations. All eight GC cases had pathogenic variants that occurred between codons 685–2040 in the St. Mark’s FAP registry where when compared to 64 % of 2974 FAP controls from the InSiGHT database. Only two of 21 patients with a gastric adenoma had an APC pathogenic variant 3’ of codon 1390 2 . All gastric cancer and most adenoma cases appear to localize 5’ to are within the center of the APC gene.

We did not discern any differences in demographic features, disease phenotype (cancer history, extra-intestinal manifestations, surgical history), or stage of duodenal polyposis between those with and without sessile gastric polyps. Though this is similar to findings from two other studies that evaluated clinical features of gastric adenomas to those without, FAP related GC and advanced stage of duodenal polyposis have been shown and may both progress with advancing age 2 8 18 .

This study is limited by the small number of sessile gastric polyps. GC is a relatively new occurrence, and the prevalence of the pathology noted in this study mirrors what has been previously described even though the precursor lesion is unknown 11 . The different neoplasms likely differentially progress to cancer if at all. The study was a single tertiary-care center study and patients are in a hereditary cancer registry which has over 1000 families from around the country so the results may not be generalizable. Furthermore, some individuals may have had surveillance performed at other institutions. The intent of the study was to explore sessile gastric polyps however other morphologies may also be associated with gastric cancer risk adding selection bias. Given the profuse, proximal gastric polyposis in many of our patients, endoscopic sampling of all lesions is impossible and high-risk gastric lesions may be missed. Though white mucosal patches were not biopsied and their spatial relationship to resected polyps were not recorded we have previously described the pathology findings 9 .

Conclusions

In conclusion, we recommend heightened awareness of the risk of sessile gastric polyps and gastric cancer in patients with FAP. We have identified features that, when present, should prompt increased intensity of gastric endoscopic surveillance, including gastric white mucosal patches, antral polyps, and family history of gastric cancer, especially in an individual with an APC pathogenic variant 5’ to 1328. In FAP, the focus has traditionally been on describing the duodenum given its established cancer risk however more care should be taken to describe gastric findings. Individuals with these features should have more frequent surveillance intervals than currently recommended (based on duodenal polyposis alone). Endoscopic criteria to visually identify these lesions have recently been developed and should be utilized 12 . Further studies should be multicentered, investigate genotype-phenotype correlations for GC in their FAP populations, explore other exposures which heighten or decrease sessile gastric polyps, and establish protocols for endoscopic detection and management of patients with worrisome endoscopic findings in their stomachs and FAP related gastric neoplasia.

Acknowledgments

Funded by the American College of Gastroenterology Clinical Research Award

Footnotes

Competing interests The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Mankaney G, Leone P, Cruise M et al. Gastric cancer in FAP: a concerning rise in incidence. Familial Cancer. 2017;16:371–376. doi: 10.1007/s10689-017-9971-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Walton S J, Frayling I M, Clark S K. Gastric tumours in FAP. Fam Cancer. 2017;16:363–369. doi: 10.1007/s10689-017-9966-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bianchi L K, Burke C A, Bennett A E et al. Fundic gland polyp dysplasia is common in familial adenomatous polyposis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;6:180–185. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2007.11.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Offerhaus G J, Giardiello F M, Krush A J et al. The risk of upper gastrointestinal cancer in familial adenomatous polyposis. Gastrointest Endosc. 1992;102:1980–2. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(92)90322-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Burt R W. Gastric fundic gland polyps. Gastroenterology. 2003;125:1462–9. doi: 10.1016/j.gastro.2003.07.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sample D C, Samadder N J, Pappas L M et al. Variables affecting penetrance of gastric and duodenal phenotype in familial adenomatous polyposis patients. BMC Gastroenterol. 2018 doi: 10.1186/s12876-018-0841-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cannon A R, Keener M, Neklason D et al. Surgical interventions, malignancies, and causes of death in a FAP patient registry. J Gastrointest Surg. 2021;25:452–456. doi: 10.1007/s11605-019-04412-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Leone P, Mankaney G, Sarvapelli S et al. Endoscopic and histologic features associated with gastric cancer in familial adenomatous polyposis. Gastrointest Endosc. 2019;89:961–8. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2018.12.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kunnathu N D, Mankaney G, Bhatt A et al. Worrisome endoscopic feature in the stomach of patients with familial adenomatous polyposis: the proximal white mucosal patch. Gastrointest Endosc. 2018;88:569–570. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2018.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Calavas L, Rivory J, Hervieu V et al. Macroscopically visible flat dysplasia in the fundus of 3 patients with familial adenomatous polyposis. Gastrointest Endosc. 2017;85:679–680. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2016.03.1499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wood L D, Salaria S N, Cruise M W et al. Upper GI tract lesions in familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP): enrichment of pyloric gland adenomas and other gastric and duodenal neoplasms. Am J Surg Pathol. 2014;38:389–93. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0000000000000146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mankaney G, Cruise M, Sarvepalli S et al. Surveillance for pathology associated with cancer on endoscopy (SPACE): criteria to identify high-risk gastric polyps in familial adenomatous polyposis. Gastrointest Endosc. 2020;92:755–762. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2020.04.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shibata C, Ogawa H, Miura K et al. Clinical characteristics of gastric cancer in patients with familial adenomatous polyposis. Tohoku J. Ex. Med. 2013;229:143–6. doi: 10.1620/tjem.229.143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Park S Y, Ryu J K, Park J H et al. Prevalence of gastric and duodenal polyps and risk factors for duodenal neoplasm in Korean patients with familial adenomatous polyposis. Gut Liver. 2011;5:46–51. doi: 10.5009/gnl.2011.5.1.46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jagelman D G, DeCosse J J, Bussey H J. Upper gastrointestinal cancer in familial adenomatous polyposis. Lancet. 1988;1:1149–51. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(88)91962-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Guyton K, Alverdy J C. The gut microbiota and gastrointestinal surgery. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;14:43–54. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2016.139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Liang S, Mao Y, Liao M et al. Gut microbiome associated with APC gene mutation in patients with intestinal adenomatous polyps. Int J Biol Sci. 2020;16:135–146. doi: 10.7150/ijbs.37399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ngamruengphong S, Boardman L A, Heigh R I et al. Gastric adenomas in familial adenomatous polyposis are common, but subtle, and have a benign course. Hered Cancer Clin Pract. 2014;12:4. doi: 10.1186/1897-4287-12-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]