Abstract

Background:

The Medicare Advantage (MA) program is rapidly growing. Limited evidence exists about the care experiences of MA beneficiaries with Alzheimer's Disease and Related Dementia (ADRD). Our objective was to compare care experiences for MA beneficiaries with and without ADRD.

Methods:

We examined MA beneficiaries who completed the Medicare Advantage Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems (CAHPS) and used inpatient, nursing home, or home health services in the past 3 years. We classified beneficiaries with ADRD using the presence of diagnosis codes in hospitals, nursing homes, and home health records. Our key measures included overall ratings of care and health plan, and indices of receiving timely care, care coordination, receiving needed care, and customer service. We compared differences between beneficiaries with and without ADRD using regression analysis adjusting for demographic, health, and plan characteristics, and stratifying by proxy response status.

Results:

Among beneficiaries sampled by CAHPS, 22.2% with ADRD completed the survey compared to 38.5% without ADRD. Among proxy responses, beneficiaries with ADRD were 4.2 (95% CI: 0.1–8.4) percentage points less likely to report a high score for receiving needed care, and 3.5 percentage points (95% CI: 0.2–6.9) less likely to report a high score for customer service. Among non-proxy responses, those with ADRD were 9.0 (95% CI: 5.5–12.5) percentage points less likely to report a high score for needed care, and 8.5 (95% CI: 5.4–11.5) percentage points less likely to report a high score for customer service.

Conclusions:

ADRD respondents to the CAHPS were more likely to be excluded from CAHPS performance measures because they did not meet eligibility requirements and rates of non-response were higher. Among responders with or without a proxy, MA enrollees with an ADRD diagnosis reported worse care experiences in receiving needed care and in customer service than those without an ADRD diagnosis.

Keywords: ADRD, Alzheimer's, CAHPS, Medicare Advantage

INTRODUCTION

The Medicare Advantage (MA) program is rapidly growing and now accounts for over 42% of Medicare beneficiaries nationally.1,2 MA differs from traditional Medicare (TM) in that private plans are paid on a capitated basis to cover the needs of their enrollees in a year. MA plans can offer additional supplemental benefits unavailable in TM.3 But they can also set specific networks of available providers4 and implement prior authorization requirements that may pose additional challenges for enrollees with chronic conditions.

Alzheimer's Disease and related dementias (ADRD) is a highly prevalent condition that is responsible for substantial care and cost burdens nationally.5-9 Individuals with ADRD and their caregivers often face additional barriers in access to care compared to other patients in the healthcare system. While both the MA program and the prevalence of ADRD continue to grow, there is currently limited evidence on the care experience of Medicare beneficiaries with ADRD in the MA program. While two recent studies have found substantially higher disenrollment rates for enrollees with ADRD from MA plans, few studies have examined the care experiences of MA enrollees with ADRD.10,11 Additionally, given that beneficiaries with ADRD may have cognitive decline or may be more likely to be institutionalized, it is unclear if their experiences are captured by current performance measurement initiatives.

In this study, we use a unique linkage of national survey data with claims and assessment data to examine the care experiences of MA enrollees with ADRD. Our two primary objectives are to understand the extent to which beneficiaries with ADRD are included in CAHPS performance measurement and to measure how the care experiences of enrollees with ADRD compared to those without.

METHODS

Data sources

Our primary source of data was the Medicare Advantage Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems (CAHPS) from 2015 through 2017. CAHPS surveys are fielded annually to a sample of 600 MA enrollees drawn from each contract. Traditionally, response rates for the CAHPS survey are similar to other health surveys, with slightly higher response rates for non-Hispanic White beneficiaries, and lower response rates for low-income beneficiaries.12-14 The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) uses CAHPS to measure the performance of MA plans. CAHPS surveys contain questions primarily related to an enrollee's experience with their care and detailed questions on enrollee demographics including self-reported race/ethnicity, income, and education level. The CAHPS survey is restricted to only non-institutionalized enrollees at the time of the survey. In addition to CAHPS, we used the Medicare Master Beneficiary Summary File (MBSF) to determine which beneficiaries were enrolled in MA and other enrollee characteristics including their ZIP Code, county, and hospital referral region of residence.

To classify beneficiaries with ADRD, we drew from three sources available for MA enrollees: The Medicare Provider Analysis and Review (MedPAR) files which include hospitalization records for over 90% of MA enrollees nationally, the Minimum Data Set (MDS) which is a nursing home assessment file for all Medicare beneficiaries ever admitted to a nursing home, and the Outcomes and Assessment Information Set (OASIS) which is a home health assessment file for all Medicare beneficiaries who receive home health care. We linked across all files in this study using a unique individual-level beneficiary ID.

Study sample

Our primary study sample were all MA beneficiaries who completed a CAHPS survey in either 2015, 2016, or 2017. We limited our sample to enrollees who had any utilization in any of our three files (MedPAR, MDS, and OASIS) used for ADRD classification to ensure that utilization alone did not contribute to any differences in outcomes. This led to an inclusion of 65,095 CAHPS respondents and an exclusion of 345,422 among MA beneficiaries without utilization. The CAHPS survey data also identifies beneficiaries that were selected for a CAHPS survey but did not complete the survey.

Classification of ADRD

The CAHPS survey does not include a question on whether the respondent has ever been diagnosed with ADRD. To identify enrollees who may have ADRD, we drew from the MedPAR, MDS, and OASIS.15 Each of these three files includes a range of ICD9 or ICD10 diagnosis codes that we used to identify ADRD diagnoses. We used the Chronic Conditions Data Warehouse (CCW) set of diagnosis codes.16 If a beneficiary had a diagnosis of ADRD across any of the included files, they were classified as having ADRD. Most beneficiaries were classified using the MedPAR file, with the second most ADRD diagnoses coming from the MDS. Consistent with the approach that Medicare uses to classify ADRD among traditional Medicare beneficiaries, we employed a three-year lookback period to identify ADRD diagnoses and used a rolling window for each year of CAHPS data. While this approach is likely to be more sensitive than using outpatient data alone, the limitation is that we may not detect ADRD among enrollees who do not utilize hospital or post-acute services during the study period. In sensitivity analysis, we also classified ADRD using 2015 MA encounter data that include all claims (including outpatient claims) for MA enrollees, and also only using the MA encounter data as a source of diagnosis and the results were largely unchanged (Table S3). We also assessed whether the results changed when excluding beneficiaries who received nursing home care, which may be associated with poor reports of care experience, and found similar results.

Outcome variables

We studied several outcomes designed to capture enrollees' care experiences. From the CAHPS survey, we used two overall measures for the respondents: (1) overall rating of their health care, and; (2) overall rating of their MA plan. Both questions ask respondents to rate on a scale of 1–10, with 10 being the best. As over 80% of respondents selected the top score for either question (10), consistent with prior studies we dichotomized these measures as 0/1 binary variables of whether the respondent selected 10 or any other value.17-19

In addition to the two overall measures, we calculated several indices that CMS uses to assess respondents' customer service experience, their care coordination experience, and whether they reported that they received needed care, got appointments and care quickly, and received needed prescriptions. These indices are based on multiple CAHPS questions and are scored out of 100.20,21 Similar to the single item questions above, we dichotomized these measures between top scorers (100), and everyone else (<100). In sensitivity analyses, we tested different thresholds for the top-rated category and found similar results.

Other variables

To adjust our analysis for potential confounders, we also included variables for the self-reported race, ethnicity, educational attainment, age, and income from the CAHPS surveys. From the MBSF we included dual eligibility status and if the beneficiary lived in a rural zip code. We also linked the MA contract number to publicly available MA characteristic data for premium, zero-premium plan, type of plan (health maintenance organization (HMO), preferred provider organization (PPO), other), special needs plan (SNP) types, and if the plan operates in multiple states. We also included flags for if the enrollee had any hospital, nursing home, or home health utilization in the year as well as flags for if the enrollee had additional comorbid conditions as reported by CAHPS.

The CAHPS survey includes a variable indicating whether a proxy helped the respondent fill out the survey. In our descriptive analysis, we found that the proxy reporting rate was substantially higher for enrollees with ADRD compared to enrollees without ADRD.22-24 To address this concern about potential differences in responses by proxy status, we stratified all of our analyses by the proxy status of the response. In sensitivity analyses we also used inverse probability weights (IPW) calculated from the probability to use a proxy response; however, the use of IPW for proxies may not offer substantial benefits over stratification.24

To compare if the experience of enrollees with ADRD is unique from other conditions, we additionally created flags to indicate whether enrollees were diagnosed with COPD, diabetes, glaucoma, acute myocardial infarction, schizophrenia, or heart failure. We selected these conditions following other work that compared ADRD outcomes9 and calculated them based on CCW code definitions following the same approach as ADRD.

Statistical analysis

We first descriptively compared CAHPS participation rates by ADRD status. We then compared the characteristics of those with an ADRD diagnosis in our sample to those who did not. Next, for each outcome we fit a linear probability model with a binary outcome variable, with ADRD status as our primary independent variable of interest, adjusting for each of the individual and plan characteristics listed above. All standard errors were clustered by a plan to account for similarities between beneficiaries in the same plans. We also include a county fixed effect in our analysis to account for regional differences. For all models, we started with an alpha of 0.05 and then used a Bonferroni adjustment for our 7 primary outcome measures to account for multiple comparisons.

In sensitivity analysis, we compared the primary outcomes using additional diagnoses from encounter records, tested the use of IPW to account for proxy responses, and tested additional forms of the outcome variables (dichotomized using alternative cutoffs, as continuous variables). We also compared differences in outcomes by enrollment in MA special needs plans and standard MA plans.

RESULTS

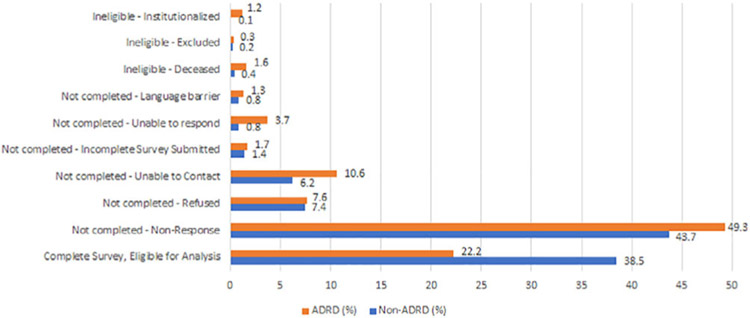

In Figure 1, we first compared the response rates to the CAHPS surveys by ADRD status. We find that while 38.5% of MA beneficiaries without ADRD were included in the performance measurement from the survey, only 22.2% of beneficiaries with ADRD were both eligible and completed the survey. Beneficiaries with ADRD had higher non-response rates (49.3% vs. 43.7%), higher rates of not being able to complete the survey due to comprehension or cognitive function (3.7% vs. 0.8%), and a higher rate of ineligibility due to being institutionalized at the time of the survey (1.2% vs. 0.1%).

FIGURE 1.

Response rates by ADRD status. The x-axis represents the % of ADRD or Non-ADRD respondents who fall into each response category. In the bottom row, Complete Survey, are the only beneficiaries who are included in quality reporting.

In Table 1, we compare the characteristics of enrollees with and without an ADRD diagnosis who completed the CAHPS survey. Our final analytic sample included 61,728 enrollees without ADRD and 3367 enrollees with ADRD. Our prevalence rate of ADRD in MA is similar to prior work.11 Enrollees in our sample with ADRD were older (mean age 83.4 vs. 74.3), more often dual eligible with Medicaid (39.6% vs. 23.5%) and were much more likely to use a proxy in completing the survey (57.6% vs. 15.3%). In Table Table S1, we present the unadjusted outcome rates by ADRD and proxy response status and in Table S2, we compare the unadjusted outcomes as continuous variables.

TABLE 1.

CAHPS respondents and plan characteristics by ADRD diagnosis

| Non ADRD | ADRD | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Patient characteristics | |||

| N | 61,728 | 3367 | |

| Disability as reason for entitlement | 19,510 (31.6%) | 1638 (48.6%) | <0.001 |

| Age | 74.3 (10.7) | 83.4 (8.5) | <0.001 |

| Female | 37,439 (60.7%) | 2285 (67.9%) | <0.001 |

| Race/ethnicity | |||

| White | 44,518 (72.1%) | 2644 (78.5%) | <0.001 |

| Black | 8192 (13.3%) | 347 (10.3%) | |

| Other/Unknown | 776 (1.3%) | 32 (1.0%) | |

| Asian | 1355 (2.2%) | 68 (2.0%) | |

| Hispanic | 6685 (10.8%) | 268 (8.0%) | |

| NA/AI | 202 (0.3%) | NA | |

| Dual | 14,511 (23.5%) | 1335 (39.6%) | <0.001 |

| Any Nursing Home Use | 11,920 (19.3%) | 2669 (79.3%) | <0.001 |

| Any Hospital Use | 49,969 (81.0%) | 2078 (61.7%) | <0.001 |

| Any Home Health use | 28,200 (45.7%) | 1686 (50.1%) | <0.001 |

| Education level | |||

| 8th grade or less | 5868 (10.2%) | 491 (16.2%) | <0.001 |

| Some high school | 7622 (13.3%) | 402 (13.3%) | |

| High school graduate or GED | 19,886 (34.6%) | 1135 (37.4%) | |

| Some college or 2-year degree | 14,672 (25.5%) | 599 (19.8%) | |

| 4-year college graduate | 4573 (8.0%) | 225 (7.4%) | |

| More than 4-year college degree | 4850 (8.4%) | 180 (5.9%) | |

| Used a Proxy | 8929 (15.3%) | 1785 (57.6%) | <0.001 |

| Plan characteristics | |||

| Special Needs Plan Type | Non-ADRD | ADRD | |

| No SNP | 45,904 (74.4%) | 2265 (67.3%) | <0.001 |

| Chronic | 1523 (2.5%) | 76 (2.3%) | |

| Dual | 14,291 (23.2%) | 1019 (30.3%) | |

| Plan type | |||

| HMO | 44,998 (72.9%) | 2443 (72.6%) | <0.001 |

| PPO | 11,705 (19.0%) | 550 (16.3%) | |

| Other/Unknown | 5025 (8.1%) | 374 (11.1%) | |

| Premium ($) | 51.2 (59.3) | 62.8 (65.5) | <0.001 |

| % Zero Premium | 16,996 (27.5%) | 687 (20.4%) | <0.001 |

| Star rating | |||

| Not Rated | 3205 (5.3%) | 121 (3.7%) | <0.001 |

| 2.5 | 2123 (3.5%) | 94 (2.9%) | |

| 3 | 8491 (14.2%) | 414 (12.8%) | |

| 3.5 | 15,835 (26.4%) | 842 (26.0%) | |

| 4 | 14,994 (25.0%) | 815 (25.1%) | |

| 4.5 | 12,652 (21.1%) | 808 (24.9%) | |

| 5 | 2538 (4.2%) | 146 (4.5%) | |

| Plan operates in multiple states | 12,904 (24.7%) | 707 (24.6%) | 0.1 |

| Plan size | |||

| Small (<3000) | 5070 (9.5%) | 361 (12.3%) | <0.001 |

| Medium (3000 to 20,000) | 18,279 (34.4%) | 1184 (40.3%) | |

| Large (>20,000) | 29,851 (56.1%) | 1391 (47.4%) | |

| For-profit plan | 206,701 (58.6%) | 1443 (48.7%) | <0.001 |

Note: NA indicates that the cell size was too small for inclusion in the table.

Abbreviations: HMO, Health Maintenance Organization; NA/AI, Native American, American Indian; PPO, Preferred Provider Organization; SNP, Special Needs Plan.

In Table 2, we present the results of our primary analysis. In general, enrollees with ADRD reported worse care experiences than enrollees without ADRD among both those who used a proxy respondent and those who did not. Among enrollees who used a proxy, those with ADRD were 4.2 (95% CI: 0.1–8.4) percentage points less likely to report a high score for getting needed care, and 3.5 percentage points (95% CI: 0.2–6.9) less likely to report a high score for the customer service index. Among enrollees who did not use a proxy, those with ADRD were 9.0 (95% CI: 5.5–12.5) percentage points less likely to report a high score for getting needed care, 8.5 (95% CI: 5.4–11.5) percentage points less likely to report a high score for the customer service index, and 4.2 (95% CI: 0.9–7.4) percentage points less likely to report a high score for getting needed. The group that did not use proxies had somewhat worse care experience scores than the groups that used a proxy and frequently performance was lower for those with ADRD compared to those without. Overall plan rating was an exception: non-proxy respondents with ADRD reported higher ratings than those without ADRD.

TABLE 2.

Adjusted differences in outcomes by ADRD and proxy status

| Outcome | Proxy response |

Non-proxy response |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline mean for patients without ADRD |

Percentage point difference for ADRD (95% CI) |

Baseline mean |

Percentage point difference for ADRD (95% CI) |

|

| Percent in the top score category | ||||

| Overall rating of care | 34.8 | −2.7 (−6.6 to 1.3) | 34.5 | 1.8 (−1.6 to 4.7) |

| Overall rating of plan | 26.2 | −3.8 (−7.8 to 0.2) | 29.9 | 3.8* (0.5 to 7.2) |

| Getting needed care | 49.1 | −4.2* (−8.4 to −0.1) | 51 | −9.0** (−12.5 to −5.5) |

| Getting appointments and care quickly | 16.9 | −0.1 (−2.4 to 4.3) | 20 | 1.4 (−1.6 to 4.3) |

| Customer service | 21.6 | −3.5* (−6.9 to −0.2) | 23.9 | −8.5** (−11.5 to −5.4) |

| Care coordination | 20.8 | −0.1 (−4.6 to 2.5) | 26.5 | 0.1 (−3.0 to 3.1)*** |

| Getting needed prescriptions | 64 | −2.4 (−6.3 to 2.5) | 65.1 | −4.2* (−7.4 to −0.9) |

Note: Results are stratified by whether a proxy helped to fill out the survey. The baseline mean is the mean value of the outcome for respondents without ADRD who responded to CAHPS. The percentage point differences are marginal effect estimates from a linear probability model adjusting for gender, race/ethnicity, rurality, education, the reason for eligibility, plan premium, plan rating, plan type (HMO, PPO, Other), plan multi-state or a single state, plan health system affiliation, and county fixed effects. All outcomes are binary variables of whether the beneficiary reported in the top-scoring category of each index (100).

<0.05

<0.01

<0.001.

In Table 3 we compare the difference in satisfaction expressed by those with ADRD relative to enrollees with other chronic disease conditions, stratified by proxy status. We found that for both the getting needed care index and the customer service index, the experience was substantially poorer for beneficiaries with ADRD, compared to beneficiaries with all other chronic conditions.

TABLE 3.

Adjusted differences in outcomes for different disease groups

| Proxy response |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcome | ADRD | COPD | AMI | Diabetes | Schizophrenia | Glaucoma | Heart failure |

| Overall rating of care | −2.7 | 0.4 | 2.4 | 0.4 | 14.3* | 1.3 | −1.1 |

| Overall rating of plan | −3.8 | 1.1 | 3.0 | 0.9 | −12.1 | −1.2 | −0.4 |

| Getting needed care index | −4.2* | 0.9 | 4.0* | −1.2 | −12.0 | −3.5 | −2 |

| Getting appointments and care quickly index | −0.1 | −1.9 | 1.8 | 0.4 | −2.3 | −3.2 | 0.3 |

| Customer service index | −3.5* | 4.1** | 2.3 | 0.7 | 3.1 | −3.8 | −3.9 |

| Care coordination index | −0.1 | −1.8 | 1.1 | −1.8 | −4.7 | 2.6 | 0 |

| Getting needed prescription index | −2.4 | −4.4** | −2.4 | −2.9* | −10.0 | −0.5 | −2.8 |

| Non-proxy response |

|||||||

| Outcome | ADRD | COPD | AMI | Diabetes | Schizophrenia | Glaucoma | Heart failure |

| Overall rating of care | 1.8 | −3.8** | −0.9 | −2.1** | −0.1 | −0.2 | 2.4 |

| Overall rating of plan | 3.8* | −4.0** | 1.9* | −1.7** | 9.0* | 0.1 | 3.7*** |

| Getting needed care index | −9.0** | −1.9** | 1.1 | −0.2 | −0.1 | −0.4 | 4.8* |

| Getting appointments and care quickly index | 1.4 | −2.6** | 0.4 | −0.9 | −0.4 | −3.7* | 3.2 |

| Customer service index | −8.5** | 1.0 | 0.3 | −0.6 | 0.5 | −0.3 | 4.1* |

| Care coordination index | 0.1 | −3.0** | −0.7 | −0.2 | 6.5* | −0.2 | 0.7 |

| Getting needed prescription index | −4.2* | −2.4** | −0.1 | −1.4** | −7.5* | −0.1 | 0.9 |

Note: Each value represents the adjusted percentage point difference in being in the top rating category for each outcome between having a given condition and not having the condition, stratified by if a proxy was used by the respondent. All models are adjusted for gender, race/ethnicity, rurality, education, the reason for eligibility, plan premium, plan rating, plan type (HMO, PPO, Other), multi-state or single-state status, plan health system affiliation, and county fixed effects.

<0.05

<0.01

<0.001.

In sensitivity analysis, we found that when including MA encounter records from 2015, we were able to classify an additional 1315 beneficiaries with ADRD who were sampled by the CAHPS. We find that after including these beneficiaries in our analysis, the results were similar to the primary analysis (Table S3). We also present results using IPW weights to account for proxy status (Table S4). When stratifying by special needs plan enrollment, we found similar differences in care experiences between those with and without ADRD (Table S5). Full regression output is available in Table S6.

DISCUSSION

Our study of the experiences of enrollees with ADRD in the MA program had four key findings. First, beneficiaries with ADRD were substantially less likely to be included in CAHPS performance measurement than beneficiaries without ADRD. Second, among those who were included in the performance measure, enrollees with ADRD reported significantly worse care experiences across several measures compared to those without ADRD. These differences for enrollees with ADRD were larger than beneficiaries with other chronic conditions, and respondents who did not use a proxy reported worse outcomes. Among non-proxy respondents, beneficiaries with ADRD reported higher overall plan ratings than those without ADRD.

Our study is among the first to study the care experiences of MA enrollees with and without ADRD. One prior study compared care experiences using the Medicare Current Beneficiary Survey and found that beneficiaries with ADRD did not report different care satisfaction scores regarding the quality of their medical care, and availability of specialists.25 Our study builds on the literature by using a larger sample of enrollees with ADRD who have had healthcare utilization and a different set of care experiences questions that are available in CAHPS.

Our study has important policy implications for evaluating the performance of MA plans in addressing the needs of their enrollees with ADRD. As the MA program continues to grow,26 and greater proportions of beneficiaries with ADRD select MA over Traditional Medicare, the need to measure and improve the quality of care for people with ADRD will only become more pressing. MA plans can offer additional benefits and care management services, such as caregiver support, adult daycare, and home modifications, which may be particularly relevant to people with ADRD and are unavailable in Traditional Medicare. However, MA plans' adoption of these benefits is low and the impact of these novel benefits on care experiences for MA enrollees needs further evaluation.3,27 Enrollment in SNPs, MA plans that are designed to take care of more complex patients, has rapidly grown from 1.3 million in 2011 to 3.8 million in 2021. While some early research finds some improved outcomes in these plans,28-31 our study does not find they were associated with significant improvements in care experiences among beneficiaries with ADRD. As MA risk adjustment now pays higher rates for enrollees with an ADRD diagnosis, it is even more important that plans address the needs of these beneficiaries.

What might be leading to these differences in care experiences for enrollees with ADRD? Prior work has found that MA beneficiaries tend to be admitted to lower quality hospitals, nursing homes, and home health agencies than those in TM,32-34 and that MA networks are often narrow in nature.4,35,36 While all beneficiaries in our study are enrolled in MA, narrow networks and other barriers to care such as prior authorizations may be an additional burden for beneficiaries with ADRD to navigate than healthier enrollees. Enrollees with dementia may also face challenges in selecting the right plan for them, leading to lowerrated care experiences.37 More research is needed to understand whether some plans perform better at meeting the care needs of enrollees with ADRD.

Our findings also have important implications for performance measurement in the MA program. We find that enrollees with ADRD are disproportionately undercounted in CAHPS responses due to both higher rates of non-response and less eligibility due to being institutionalized. CMS uses five CAHPS measures in their calculation of overall plan star ratings.38 If enrollees with ADRD are not included in these measures, then plans may not currently be held accountable for their outcomes. To address this, it is crucial to design performance measures that equitably include persons with serious health conditions, functional and cognitive decline, and who require proxies to complete surveys of patient experience Otherwise, plans may not be properly incentivized to address these care experience gaps. CMS may also need to use alternative survey modalities to better account for non-response among persons with ADRD, or may consider over-sampling older respondents with this condition.

Limitations

Our study has several limitations. First, given limitations in available data about the Medicare Advantage population, our main analysis is limited to enrollees who received hospital, nursing home, or home health care in any of our study years. As such, our results may not generalize to the care experiences of enrollees with ADRD but who do not receive these services. Second, the source of where an ADRD diagnosis was captured may influence our results, however, in sensitivity analyses, we find similar results across settings of care. Third, the MedPAR file may undercount ADRD cases as ADRD may not always be coded for inpatient stays. Fourth, while our finding that there are lower and non-response rates among enrollees with ADRD has important policy relevance, we are limited in being able to measure the care experiences among those who did not respond. Fifth, we do not have detailed information on why certain respondents used a proxy and why others did not. Sixth, this analysis is associational and we cannot draw causal inference from our findings.

CONCLUSIONS

In conclusion, MA enrollees with an ADRD diagnosis reported worse care experiences in receiving needed care and in customer service than those without an ADRD diagnosis. Further, relative to those without ADRD, ADRD respondents to the CAHPS were twice as likely to be excluded from CAHPS performance measures because they did not meet eligibility requirements or did not respond to the survey. In order to ensure that all enrollees in the MA program have access to high-quality services, more efforts may be needed to measure and address the care needs of the ADRD population.

Supplementary Material

Table S1: Unadjusted Differences in Outcomes by ADRD and Proxy Status

Table S2: Unadjusted Differences in Outcomes by ADRD Status- continuous variables

Table S3: Primary results including additional diagnoses from encounter claims

Table S4: Primary results using IPW to account for proxy status

Table S5: Care Experiences for Patients with ADRD in Dual Special Needs Plans and Non-Special Needs Plans, by Proxy Response

Table S6a: Full Regression Coefficients for Primary Analysis, Proxy Responses

Table S6b: Full Regression Coefficients for Primary Analysis, Non-Proxy Responses

Key points

Medicare Advantage enrollees with ADRD report worse care experiences than beneficiaries without ADRD

Beneficiaries with ADRD are disproportionately excluded from performance measurement through the CAHPS survey

Why does this paper matter?

As the Medicare Advantage program continues to grow, it is imperative that plans are held accountable for the outcomes and care experiences of their enrollees with ADRD.

Funding information

National Institute on Aging, Grant/Award Number: 5P01AG027296-13

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

Vincent Mor chairs the Scientific Advisory Board of naviHealth, a post-acute care convener. All other authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

SUPPORTING INFORMATION

Additional supporting information may be found in the online version of the article at the publisher's website.

REFERENCES

- 1.Meyers DJ, Johnston KJ. The growing importance of Medicare Advantage in health policy and health services research. JAMA Health Forum. 2021;2(3):e210235. doi: 10.1001/jamahealthforum.2021.0235 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Neuman P, Jacobson GA. Medicare Advantage checkup. N Engl J Med. 2018;379(22):2163–2172. doi: 10.1056/NEJMhpr1804089 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Meyers DJ, Durfey SNM, Gadbois EA, Thomas KS. Early adoption of new supplemental benefits by Medicare Advantage plans. JAMA. 2019;321(22):2238–2240. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.4709 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Meyers DJ, Rahman M, Trivedi AN. Narrow primary care networks in Medicare Advantage. J Gen Intern Med. 2021;19:488–491. doi: 10.1007/s11606-020-06534-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Black CM, Mehta V, Dubin B, Khandker RK, Ambegaonkar BM, Marsico M. Health care use among newly diagnosed Alzheimer's (AD) patients in a U.S. commercial Medicare Advantage insurance plan. Alzheim Dement J Alzheimers Assoc. 2017;13(7):P859. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2017.06.1216 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Joyce AT, Zhao Y, Bowman L, Flynn JA, Carter CT, Ollendorf DA. Burden of illness among commercially insured patients with Alzheimer's disease. Alzheim Dement J Alzheim Assoc. 2007;3(3):204–210. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2007.04.373 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Weiner M, Powe NR, Weller WE, Shaffer TJ, Anderson GF. Alzheimer's disease under managed care: implications from Medicare utilization and expenditure patterns. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1998;46(6):762–770. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1998.tb03814.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dwibedi N, Findley PA, Wiener CR, Shen C, Sambamoorthi U. Alzheimer disease and related disorders and out-of-pocket health care spending and burden among elderly Medicare beneficiaries. Med Care. 2018;56(3):240–246. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0000000000000869 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nicholas LH, Langa KM, Bynum JPW, Hsu JW. Financial presentation of Alzheimer disease and related dementias. JAMA Intern Med. 2021;181(2):220–227. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.6432 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Meyers DJ, Rahman M, Rivera-Hernandez M, Trivedi AN, Mor V. Plan switching among Medicare Advantage beneficiaries with Alzheimer's disease and other dementias. Alzheim Dement Transl Res Clin Interv. 2021;7(1):e12150. doi: 10.1002/trc2.12150 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jutkowitz E, Bynum JPW, Mitchell SL, et al. Diagnosed prevalence of Alzheimer's disease and related dementias in Medicare Advantage plans. Alzheim Dement Diagn Assess Dis Monit. 2020;12(1):e12048. doi: 10.1002/dad2.12048 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Beckett MK, Elliott MN, Burkhart Q, et al. The effects of survey version on patient experience scores and plan rankings. Health Serv Res. 2019;54(5):1016–1022. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.13172 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Burkhart Q, Orr N, Brown JA, et al. Associations of mail survey length and layout with response rates. Med Care Res Rev. 2021; 78(4):441–448. doi: 10.1177/1077558719888407 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Klein DJ, Elliott MN, Haviland AM, et al. Understanding non-response to the 2007 Medicare CAHPS survey. Gerontologist. 2011;51(6):843–855. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnr046 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Huckfeldt PJ, Escarce JJ, Rabideau B, Karaca-Mandic P, Sood N. Less intense Postacute care, better outcomes for enrollees in Medicare Advantage than those in fee-for-service. Health Aff. 2017;36(1):91–100. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2016.1027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gorina Y, Kramarow EA. Identifying chronic conditions in Medicare claims data: evaluating the chronic condition data warehouse algorithm. Health Serv Res. 2011;46(5):1610–1627. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2011.01277.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Meyers DJ, Rahman M, Wilson IB, Mor V, Trivedi AN. The relationship between Medicare Advantage star ratings and enrollee experience. J Gen Intern Med. 2021;12:3704–3710. doi: 10.1007/s11606-021-06764-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schmocker RK, Cherney Stafford LM, Siy AB, Leverson GE, Winslow ER. Understanding the determinants of patient satisfaction with surgical care using the Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems surgical care survey (SCAHPS). Surgery. 2015;158(6):1724–1733. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2015.06.018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Toomey SL, Zaslavsky AM, Elliott MN, et al. The development of a pediatric inpatient experience of care measure: child HCAHPS. Pediatrics. 2015;136(2):360–369. doi: 10.1542/peds.2015-0966 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Centers for Medicare an Medicaid Services. Scoring of MA & PDP CAHPS Survey Composite Measures. Published online November 2019. Accessed January 30, 2020. https://www.ma-pdpcahps.org/globalassets/ma-pdp/technical-specifications/scoring-of-ma--pdp-cahps-survey-composite-measures-2019.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 21.Centers for Medicare an Medicaid Services. Medicare Advantage and Prescription Drug Plan CAHPS® Survey. Published January 24, 2020. Accessed February 3, 2020. https://www.ma-pdpcahps.org/ [Google Scholar]

- 22.Roydhouse JK, Gutman R, Wilson IB, Kehl KL, Keating NL. Patient and proxy reports regarding the experience of treatment decision-making in cancer care. Psychooncology. 2020;29(11): 1943–1950. doi: 10.1002/pon.5528 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Roydhouse JK, Gutman R, Keating NL, Mor V, Wilson IB. Proxy and patient reports of health-related quality of life in a national cancer survey. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2018;16(1): 6. doi: 10.1186/s12955-017-0823-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Roydhouse JK, Gutman R, Keating NL, Mor V, Wilson IB. Propensity scores for proxy reports of care experience and quality: are they useful? Health Serv Outcomes Res Methodol. 2020; 20(1):40–59. doi: 10.1007/s10742-019-00205-4 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Park S, White L, Fishman P, Larson EB, Coe NB. Health care utilization, care satisfaction, and health status for Medicare Advantage and traditional Medicare beneficiaries with and without Alzheimer disease and related dementias. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(3):e201809. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.1809 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Meyers DJ, Mor V, Rahman M, Trivedi AN. Growth in Medicare Advantage greatest among Black and Hispanic enrollees. Health Aff. 2021;40(6):945–950. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2021.00118 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Meyers DJ, Gadbois EA, Brazier J, Tucher E, Thomas KS. Medicare plans' adoption of special supplemental benefits for the chronically ill for enrollees with social needs. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(5):e204690. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.4690 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Powers BW, Yan J, Zhu J, et al. The beneficial effects of Medicare Advantage special needs plans for patients with end-stage renal disease. Health Aff. 2020;39(9):1486–1494. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2019.01793 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Haviland AM, Elliott MN, Klein DJ, Orr N, Hambarsoomian K, Zaslavsky AM. Do dual eligible beneficiaries experience better health care in special needs plans? Health Serv Res. 2021;56(3): 517–527. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.13620 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhang Y, Diana ML. Effects of early dual-eligible special needs plans on health expenditure. Health Serv Res. 2018;53(4):2165–2184. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.12778 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Keohane LM, Zhou Z, Stevenson DG. Aligning medicaid and Medicare Advantage managed care plans for dual-eligible beneficiaries. Med Care Res Rev. 2021;79(2):207–217. doi: 10.1177/10775587211018938 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Meyers DJ, Mor V, Rahman M. Medicare Advantage enrollees more likely to enter lower-quality nursing homes compared to fee-for-service enrollees. Health Aff. 2018;37(1):78–85. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2017.0714 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Meyers DJ, Trivedi AN, Mor V, Rahman M. Comparison of the quality of hospitals that admit Medicare Advantage patients vs traditional Medicare patients. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(1): e1919310. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.19310 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schwartz ML, Kosar CM, Mroz TM, Kumar A, Rahman M. Quality of home health agencies serving traditional Medicare vs Medicare Advantage beneficiaries. JAMA Netw Open. 2019; 2(9):e1910622. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.10622 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sen AP, Meiselbach MK, Anderson KE, Miller BJ, Polsky D. Physician network breadth and plan quality ratings in Medicare Advantage. JAMA Health Forum. 2021;2(7):e211816. doi: 10.1001/jamahealthforum.2021.1816 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Graves JA, Nshuti L, Everson J, et al. Breadth and exclusivity of hospital and physician networks in US insurance markets. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(12):e2029419. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.29419 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.McWilliams JM, Afendulis CC, McGuire TG, Landon BE. Complex Medicare Advantage choices may overwhelm seniors—especially those with impaired decision making. Health Aff. 2011;30(9):1786–1794. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2011.0132 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.CMS. Medicare 2019 Part C & D star ratings technical notes. 21, 2019. https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Prescription-Drug-Coverage/PrescriptionDrugCovGenIn/Downloads/2019-Technical-Notes.pdf [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1: Unadjusted Differences in Outcomes by ADRD and Proxy Status

Table S2: Unadjusted Differences in Outcomes by ADRD Status- continuous variables

Table S3: Primary results including additional diagnoses from encounter claims

Table S4: Primary results using IPW to account for proxy status

Table S5: Care Experiences for Patients with ADRD in Dual Special Needs Plans and Non-Special Needs Plans, by Proxy Response

Table S6a: Full Regression Coefficients for Primary Analysis, Proxy Responses

Table S6b: Full Regression Coefficients for Primary Analysis, Non-Proxy Responses