Nonsuicidal self-injury (NSSI) refers to the deliberate destruction of body tissue without the intent to die and for purposes that are not socially sanctioned (International Society for the Study of Self-Injury, 2018; Nock, 2010). Historically, NSSI has been primarily studied within the context of borderline personality disorder; however, NSSI is now conceptualized as a clinically important behavior in its own right and the basis of a separate clinical condition (i.e., NSSI disorder) that has high rates of co-occurrence with other psychiatric disorders (American Psychiatric Association, 2013; Bentley et al., 2015; Patel et al., 2021). The lifetime prevalence of NSSI is estimated to be 6% in adults (Klonsky, 2011), although there is evidence that the prevalence of NSSI may be increasing (Klonsky, 2011; Swannell et al., 2014; Wester et al., 2018). The lifetime prevalence of NSSI appears to be slightly higher among active-duty service members (i.e., 6.3% - 7.9%; Turner et al., 2019) and even higher among military veterans, with estimates ranging from 13–16% (Lear et al., 2021; Monteith et al., 2020).

Despite meta-analytic findings suggesting that female adults engage in NSSI only slightly more often than male adults (i.e., small effect sizes), assessment of NSSI in male adults, especially veterans, has been largely overlooked until quite recently (Bresin & Schoenleber, 2015; Kimbrel et al., 2017). One potential source of under-identification may be that some forms of NSSI that are more common among male adults (e.g., wall/object punching, which is endorsed more frequently by male [44%] than female adults [19%]; Whitlock et al., 2011) are often omitted from NSSI assessments (Kimbrel et al, 2017). For example, Kimbrel and colleagues (2018) found that inclusion of wall/object punching in the operational definition of NSSI increased the overall rate of NSSI by 14% among a large, predominantly male veteran sample seeking treatment for posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). This rate of missed identification is concerning given that NSSI is one of the most robust predictors of suicidal ideation, attempts, and death by suicide identified to date (Klonsky et al., 2013; Kimbrel et al., 2015; Ribeiro et al., 2016; Turner et al., 2019; Ward-Ciesielski et al., 2016). The inclusion of NSSI disorder in the DSM-5 further supports the significant impairment and distress that may be associated with repeated NSSI (Gratz et al., 2015; Selby et al., 2012, 2015).

The recognition of NSSI disorder as a unique clinical construct in the DSM-5 has led to increased awareness of the need for the systematic assessment of NSSI behaviors in a variety of clinical settings. NSSI assessment largely falls into two formats: clinician-administered structured interviews and self-administered instruments. For example, the Clinician-Administered NSSI Disorder Index (CANDI) is a structured interview that assesses DSM-5 NSSI disorder criteria, including the frequency and consequences of, motives for, and interference and distress associated with NSSI (Gratz et al., 2015). The Self-Injurious Thoughts and Behaviors Interview (SITBI) is another commonly used structured interview of NSSI behaviors (in addition to self-injurious thoughts and suicidal behaviors) that was developed before the introduction of NSSI disorder in DSM-5. Both the CANDI and SITBI are estimated to take around 15 minutes to administer (Gratz et al., 2015; Nock et al., 2007), although both can take considerably longer for complex case presentations. Whereas structured interviews provide comprehensive assessment of NSSI characteristics, the robust relationship between NSSI and suicidality, as well as the significant functional impairment that can accompany NSSI, necessitates briefer assessments that can be administered efficiently in a variety of clinical settings. Notably, although there are several well-validated self-report measures of NSSI that do not require administration by a trained interviewer, including the Deliberate Self-Harm Inventory (DSHI; Gratz, 2001), the Non-Suicidal Self-Injury Assessment Tool (NSSI-AT; Whitlock et al., 2014), and the Self-Harm Inventory (SHI; Sansone et al., 1998), these measures assess multiple characteristics of NSSI (e.g., function, method, frequency, duration, severity) and, as such, are not necessarily feasible to administer in diverse clinical settings due to their relatively long administration times. In addition, the detailed questions about NSSI characteristics unnecessarily add to participant burden in settings where the base rate of NSSI may be relatively low (e.g., primary care clinics).

Rationale for the Present Study

Despite the availability of a number of psychometrically sound self- and clinician-administered measures of NSSI, there currently exists a significant gap in the assessment of NSSI in the form of a brief and efficient screen for NSSI appropriate for use in primary care and mental health settings. Such a screen is a necessary first step in developing clinical pathways for patients engaging in NSSI and may facilitate efficient identification of patients in need of more comprehensive assessment and treatment programs. Implementation of a screening tool in a large-scale primary care setting necessitates that the tool be as brief as possible and easy-to-score (e.g., Bliese et al., 2008; Prins et al., 2016). Just as brief depression and suicide screens are routinely used in clinics and healthcare systems worldwide to identify patients with these conditions, there is a pressing need for a brief and efficient NSSI screen that is appropriate for use in a wide range of settings. Such a screen should also: (1) capture NSSI behaviors that are prevalent among both male and female adults (i.e., address the current under-identification of NSSI in male adults); (2) be applicable to and useful across clinically heterogeneous populations; and (3) be appropriate for use in active service and veteran populations (Turner et al., 2019).

Study Objective & Hypotheses

The primary objective of the present research was to develop a brief screen for current NSSI that would be feasible to administer in a variety of clinical settings, including primary care clinics. We elected to conduct our initial work in this area among service-connected veterans with a range of psychiatric disorders, as prior research suggests that a high percentage of veterans who seek treatment for PTSD and other mental health conditions engage in NSSI (e.g., Kimbrel et al., 2018). Our goal was to develop a Screen for Nonsuicidal Self-Injury (SNSI) that would demonstrate a single factor structure and exhibit good psychometric properties (i.e., construct, convergent, divergent, and external validity; predictive validity; and internal consistency).

Methods

Participants and Procedures

Study participants (N = 124) were veterans recruited through the Durham Veterans Affairs Health Care System (VAHCS) to participate in a VA-sponsored study (#I01CX001486) designed to observe functional outcomes of NSSI in veterans. Veterans were recruited through phone calls and letters based on: (1) chart reviews indicating a history of treatment for PTSD or other mental health conditions; (2) referrals by VAHCS clinicians; or (3) inclusion in research recruitment databases. Recruitment efforts were made to oversample women veterans and veterans with NSSI to ensure sufficient representation for statistical analyses. Veterans seeking treatment for PTSD and other mental health conditions were specifically targeted in recruitment efforts because high rates of NSSI have been observed within this population previously (Kimbrel et al., 2018) and because NSSI is greatly underreported in medical records, particularly among men and veterans (Kimbrel et al., 2017).

Participants completed a phone screen to assess basic eligibility. Participants who met initial study criteria during the phone screen were then invited to complete an in-person screening appointment that was used to determine final eligibility. Eligible participants included veterans who had previously served in the United States military, were over the age of 18, were willing to complete study procedures, and had one or more current psychiatric disorders (excluding participants with bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, and schizoaffective disorder). Of the 124 enrolled participants, 37.9% (n = 47) reported past-year engagement in NSSI and approximately one-third (n = 41; 33.1%) met full diagnostic criteria for current NSSI disorder. The rest of the sample (n = 83; 66.9%) was comprised of veterans who met criteria for at least one lifetime psychiatric disorder. Table 1 provides descriptive statistics for the sample, including baseline demographic and clinical characteristics.

Table 1.

Baseline Demographic and Clinical Characteristics

| Current NSSI Disordera n = 41 |

No Current NSSI Disorder n = 83 |

p values | Effect Size | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 46.4 ± 12.7 | 49.9 ± 13.0 | .16 | 0.27 |

| Male assigned at birth %, (n) | 70.7% (29) | 75.9% (63) | .54 | 0.11 |

| Education, years | 14.5 ± 2.3 | 14.3 ± 2.2 | .65 | 0.09 |

| Race %, (n)b | ||||

| White | 43.9% (18) | 41.0% (34) | .76 | 0.06 |

| Black | 53.7% (22) | 50.6% (42) | .75 | 0.06 |

| Asian | 0.0% (0) | 1.2% (1) | .48 | 0.13 |

| > 1 Race | 2.4% (1) | 1.2% (1) | .61 | 0.09 |

| Ethnicity %, (n) | ||||

| Hispanic | 0.0% (0) | 2.4% (2) | .32 | 0.18 |

| Current NSSI Behaviors %, (n)c | 100.0% (41) | 7.2% (6) | <.01 | 3.44 |

| Current Psychiatric Disorders %, (n) | ||||

| Posttraumatic Stress Disorder | 90.2% (37) | 71.1% (59) | .02 | 0.73 |

| Major Depressive Disorder | 82.9% (34) | 47.0% (39) | <.01 | 0.94 |

| Borderline Personality Disorder | 78.1% (32) | 20.5% (17) | <.01 | 1.45 |

| Obsessive Compulsive Disorder | 46.3% (19) | 27.7% (23) | .04 | 0.45 |

| Generalized Anxiety Disorder | 26.8% (11) | 12.0% (10) | .04 | 0.54 |

| Panic Disorder | 24.4% (10) | 9.6% (8) | .03 | 0.61 |

| Alcohol Use Disorder | 22.0% (9) | 21.7% (18) | .97 | 0.01 |

| Social Anxiety Disorder | 19.5% (8) | 6.0% (5) | .02 | 0.73 |

| Eating disorder | 19.5% (8) | 8.4% (7) | .07 | 0.54 |

| Substance Use Disorder | 14.6% (6) | 6.0% (5) | .11 | 0.54 |

| Specific Phobia | 2.4% (1) | 2.4% (2) | .99 | 0.01 |

Note: Data presented as mean ± standard deviation unless otherwise indicated.

NSSI disorder assessed with the Clinician-Administered NSSI Disorder Index (CANDI),

Race undisclosed by five participants,

any NSSI behaviors endorsed on the Deliberate Self-Harm Inventory (DSHI), the Screen for Nonsuicidal Self-Injury (SNSI), or nonsuicidal behaviors endorsed on the Columbia-Suicide Severity Rating Scale (C-SSRS); NSSI = nonsuicidal self-injury.

Diagnostic and Clinical Interviews

The Clinician-Administered Nonsuicidal Self-Injury Disorder Index (CANDI; Gratz et al., 2015) was used to diagnose NSSI disorder. The CANDI is a semi-structured diagnostic interview that assesses each of the DSM-5-defined criteria for NSSI disorder. In addition to the number of behaviors endorsed in the past year, the CANDI also assesses how often different motives for the respective behaviors were experienced, how often various thoughts or emotions preceded NSSI, the frequency, length, and intensity of preoccupation of NSSI, the frequency and intensity of thoughts and urges to engage in NSSI, as well as impairment and distress associated with NSSI. The CANDI has been shown to have good interrater reliability (ᴋ = .83) and adequate internal consistency (α = .71; Gratz et al., 2015). Master’s level clinicians administered the CANDI under the supervision of a licensed clinical psychologist. Because NSSI disorder is currently listed as a condition for further study in the DSM-5, weekly diagnostic review groups were conducted with a licensed clinical psychologist and other licensed clinicians with expertise in NSSI to ensure diagnostic accuracy. The CANDI interview for all 124 participants was reviewed during the diagnostic review groups, with diagnostic consensus used to determine current NSSI disorder status for all participants at baseline and 12-months later.

The Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-5 (SCID-5; First et al., 2015) was administered to assess for current and lifetime psychiatric disorders, as well as for exclusion criteria (i.e., bipolar disorder and psychosis). Under the supervision of a licensed clinical psychologist, Master’s level clinicians administered the SCID-5. The reliability among the interviewers was excellent (Fleiss’ kappa = .92 for lifetime psychiatric disorders on fidelity training videos).

The Columbia-Suicide Severity Rating Scale (C-SSRS; Posner et al., 2011) was administered to assess for suicidal ideation and behavior, as well as the presence of NSSI (i.e., nonsuicidal behaviors). For this study, the semi-structured interview version of the C-SSRS was utilized. The interview consists of two ideation subscales (e.g., severity and intensity of ideation) and two subscales related to behavior (e.g., lethality and modality of behavior). The C-SSRS has been found to have good convergent validity with the Beck Scale for Suicidal Ideation in veterans and good predictive validity in assessing suicidal behavior (Matarazzo et al., 2019). The C-SSRS was used as a measure of convergent validity (i.e., NSSI at baseline) and predictive validity (i.e., NSSI and suicidal ideation re-assessed at 12 months).

Self-report Measures

The Deliberate Self-Harm Inventory (DSHI; Gratz, 2001) was used as a self-report measure of NSSI in conjunction with the CANDI. Specifically, the DSHI was administered to participants prior to the CANDI interview to identify relevant NSSI behaviors on which to focus the CANDI interview. The DSHI is a 17-item measure that lists various NSSI behaviors (e. g., cutting, burning, skin-carving, severe scratching, self-biting, sticking sharp objects into the skin, and head-banging) and asks participants to identify the specific forms of NSSI and frequency of each form engaged in during the past year. The DSHI has demonstrated good test-retest reliability and convergent and divergent validity in prior research (Gratz, 2001). The DSHI was used as a measure of convergent validity.

The Beck Scale for Suicide Ideation (BSS; Beck et al., 1979) is a 21-item measure that assesses current suicidal ideation and the intensity of suicidal attitudes, plans, and behavioral intentions. The items in the BSS are rated on a scale of zero to two, and a total score is calculated by summing the first 19 items. The BSS has been shown to have moderately high internal consistency (α = .84) and high interrater reliability (ᴋ = .98; Beck et al., 1997). The BSS was used as a measure of divergent validity.

The Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9; Kroenke et al., 2001) is a nine-item module based on the full Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ). The questionnaire is used to screen for the presence of major depression. The total scores of the PHQ-9 range from zero to 27 with each item being rated from zero to three. The PHQ-9 has been shown to have excellent internal consistency (α = .89; Kroenke et al., 2001) and adequate convergent and discriminant validity (Titov et al., 2011). The PHQ-9 was used as a measure of divergent validity.

The Urgency-Premeditation-Perseverance-Sensation Seeking-Positive Urgency Scale (UPPS-P; Whiteside & Lynam, 2001) is a 59-item self-report measure that assesses five dimensions of impulsivity. Participant are asked to rate items on a four-point Likert-type scale. Each subscale (i.e., negative urgency, lack of premedication, lack of perseverance, sensation seeking, and positive urgency) is scored by calculating the mean of the relevant items after reverse scoring relevant items. Each of the subscales has been shown to have adequate internal consistency (α = .82–.91) and convergent validity (Whiteside & Lynam, 2001). The UPPS-P was used as a measure of divergent validity.

The Sheehan Disability Scale (SDS; Sheehan et al., 1996) is a five-item questionnaire that assesses social and vocational impairment due to psychological symptoms. The first three items assess the extent of impairment in the domains of work/schooling, social life, and familial responsibilities on a scale from one to 10 and can be summed to calculate a total severity score. The final two questions assess how many days the patient has been affected by their psychological symptoms in the last week. The SDS was used as a measure of external validity.

The World Health Organization Disability Assessment Schedule 2.0 (WHODAS 2.0; Üstün et al., 2010) is a 36-item measure used to assess general health and disability levels based on the International Classification of Functioning, Disability, and Health. Participants were asked to rate how much difficulty they had completing various activities using a five-point scale. The WHODAS 2.0 has strong internal consistency and an overall test-retest reliability of r = .98 (Üstün et al., 2010). The WHODAS was used as a measure of external validity.

Item Development

An initial pool of 16 items designed to assess frequently endorsed NSSI behaviors was developed by the last author based on subject matter expertise and prior work in the area (Gratz, 2001; Kimbrel et al., 2018; Resnick & Weaver, 1994; Whitlock et al., 2014, 2021). To ensure that the SNSI had adequate content validity from the outset, several existing measures of NSSI were reviewed, including the DSHI (Gratz, 2001); NSSI-AT (Whitlock et al., 2014); an earlier unpublished version of the NSSI-AT, known as the Brief Non-Suicidal Self-Injury Assessment Tool (BNSSI-AT; Whitlock et al., 2021), which contains additional items; and the five-item version of the Habit Questionnaire (Kimbrel et al., 2018; Resnick & Weaver, 1994), which has been used in a number of prior studies of NSSI in veterans (see Table 2). To facilitate the speed with which participants could complete the SNSI (and thereby increase the speed of the general screening process), each item was structured to begin with the same stem: “Have you ever intentionally…” If participants endorse “yes” to the screening item, they are asked to indicate how many times they have engaged in this behavior in the past year on a five-point scale where one = “1 time” and five = “5+ times”. We elected to focus on the past year (as opposed to the past week or month) to make the screening consistent with Criterion A of the proposed NSSI disorder criteria (American Psychiatric Association, 2013), which requires that an individual endorses engaging in NSSI on at least five separate days in the past year. Two continuous scores can be calculated for the SNSI, one which sums the total number of behaviors endorsed (where “no” = “0” and “yes” = “1” for each behavior; Appendix A) and the other which sums the frequency items for each behavior (where an initial “no” response = “0” and “5+ times” = “5” for each behavior; Appendix B).

Table 2.

Item Characteristics for the Screen for Nonsuicidal Self-Injury (SNSI) Questions (Dichotomous Items)

| % (n) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Construct previously included on: | Current NSSI Disordera | No Current NSSI Disorder | ||||

| Screen for Nonsuicidal Self-injury (SNSI) Items | Habit | NSSI-AT | DSHI | BNSSI-AT | (n = 41) | (n = 83) |

| Have you ever intentionally punched or hit walls or objects to the point of bruising or bleeding? | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 78.05% (32) | 15.66% (13) | |

| Have you ever intentionally scratched yourself to the point that you bled or it left a mark? | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 46.34% (19) | 4.82% (4) |

| Have you ever intentionally bitten your cheeks, lips, or other parts of your body to the point of bleeding or breaking the skin? | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 41.46% (17) | 6.02% (5) | |

| Have you ever intentionally punched or hit yourself to the point of bruising or bleeding? | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 41.46% (17) | 1.20% (1) |

| Have you ever intentionally stuck sharp objects (e.g., needles, pins, staples) into your skin? | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 34.15% (14) | 4.82% (4) | |

| Have you ever intentionally banged your head against walls or objects to the point of bruising or bleeding? | ✓ | 29.27% (12) | 2.41% (2) | |||

| Have you ever intentionally cut yourself (e.g., on your wrists, legs, or torso)? | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 26.83% (11) | 0.00% (0) |

| Have you ever intentionally prevented wounds from healing? | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 24.39% (10) | 4.82% (4) | |

| Have you ever done anything else to intentionally hurt or mutilate your body on purpose that resulted in tissue damage (e.g., bruising or bleeding)? | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 21.95% (9) | 0.00% (0) | |

| Have you ever intentionally burned yourself (e.g., with a lighter or cigarette)? | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 12.20% (5) | 0.00% (0) |

| Have you ever intentionally rubbed your skin with glass or sandpaper until it left a mark? | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 4.88% (2) | 1.20% (1) | |

| Have you ever intentionally carved words, pictures, or designs into your skin? | ✓ | ✓ | 2.44% (1) | 1.20% (1) | ||

| Have you ever engaged in fighting or other aggressive activities with the specific intention of getting hurt? | ✓ | 2.44% (1) | 1.20% (1) | |||

| Have you ever intentionally put bleach, cleaning supplies, or acid onto your skin for the purpose of hurting yourself? | ✓ | ✓ | 0.00% (0) | 0.00% (0) | ||

| Have you ever intentionally ingested (swallowed) a dangerous substance(s) or sharp object(s), such as Drano, other cleaning substances, or pins? | ✓ | 0.00% (0) | 0.00% (0) | |||

| Have you ever intentionally broken your own bones or tried to break your own bones? | ✓ | ✓ | 0.00% (0) | 0.00% (0) | ||

Note: Items in bold indicate the items included in final versions of measure.

NSSI disorder assessed with the Clinician-Administered NSSI Disorder Index (CANDI); NSSI = nonsuicidal self-injury.

Item Selection

Frequencies of dichotomous endorsement of all NSSI behaviors are presented in Table 2 (see Supplementary Table 1 for frequency endorsement for all NSSI behaviors). SNSI items were selected based on the frequency with which they were endorsed by individuals diagnosed with NSSI disorder in the present study. Specifically, the 10 items that were selected for inclusion in the final version of the SNSI were the 10 items with the highest past-year frequency among participants with NSSI disorder. Final versions of the SNSI are presented in Appendix A and Appendix B. As can be seen in Table 2, the six items that were excluded from the final version of the SNSI were items that were endorsed by fewer than 5% of participants with NSSI disorder, whereas each of the ten items selected for inclusion in the SNSI were endorsed by 10% or more of participants diagnosed with NSSI disorder.

Statistical Approach

Frequencies, means, standard deviations, and range were calculated for all items. Internal consistency was assessed with Cronbach’s alpha. Factor structure was assessed through principal component analysis (PCA) and accompanying parallel analysis. Construct validity was assessed through group comparisons (i.e., NSSI disorder vs. no NSSI disorder on the CANDI) on SNSI total scores and with receiver operating characteristic (ROC) analyses predicting current NSSI disorder on the CANDI to determine optimal scoring according to Youden’s Index maximizing sensitivity and specificity (Youden, 1950). ROC analyses also examined potential performance differences on the SNSI based on demographic characteristics (i.e., age, sex assigned at birth, and race). Correlations between the SNSI and other measures were used to assess convergent (i.e., DSHI, C-SSRS), divergent (i.e., BSS, PHQ-9, UPPS-P), and external (i.e., SDS, WHODAS) validity. ROC analyses predicting NSSI disorder as assessed with the CANDI and NSSI behavior at 12-months (assessed with the C-SSRS) were used to assess predictive validity of the SNSI. All analyses were done in R version 4.0.2.

Results

Internal Consistency

SNSI scores demonstrated good internal consistency for the dichotomous (Cronbach’s alpha = .86) and continuous frequency (Cronbach’s alpha = .85) items.

Exploratory Factor Analysis

PCA was used to explore the factor structure of both the dichotomous and continuous frequency items of the SNSI. As can be seen in Supplementary Figure 1, visual inspection of the scree plots and parallel analysis indicated that the SNSI has a unidimensional factor structure, with one component explaining 43–49% of the variance in both the dichotomous and continuous frequency items.

Construct Validity

Dichotomous items.

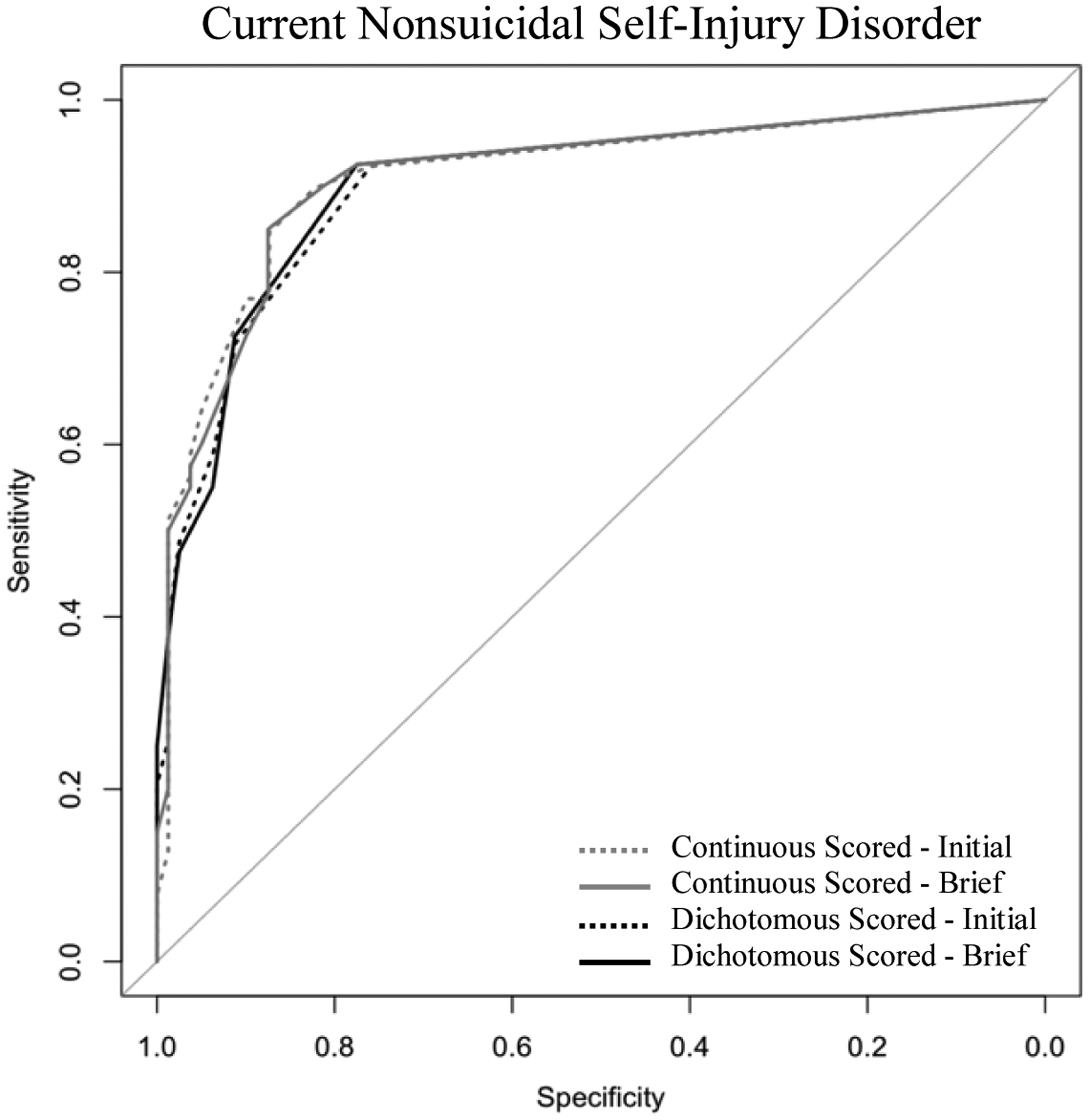

As expected, the current NSSI disorder group had significantly higher SNSI scores (M = 3.65, SD = 2.67) than the non-NSSI disorder group (M = 0.41, SD = 0.96, t (44.14) = 7.42, p <.001). The area under the curve (AUC) value for the SNSI dichotomous items identifying current NSSI disorder via the CANDI (.90, 95% CI [.85, .96]) was excellent. Further, within this unique sample where most of the self-injuring individuals met criteria for NSSI disorder, the SNSI also demonstrated good properties as a screen with an optimal cut point of one (sensitivity = .93, specificity = .78, NPV = .96, PPV = .67; see Table 3). Furthermore, there were no significant differences between the initial SNSI 16-item version and the final 10-item version with respect to identifying current NSSI disorder (AUC = .90, 95% CI [.84, .96]; Venkatraman’s bootstrapped test p = .22; see Figure 1).

Table 3.

SNSI (Dichotomous Items) Cut-Points Identifying Nonsuicidal Self-Injury Disorder

| Cut Score | Sensitivity | Specificity | NPV | PPV | AUC [95% CI] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SNSI Total Score | .90 [.85, .96] |

||||

| 0 | .99 | - | - | .33 | |

| 1 | .93 | .78 | .96 | .67 | |

| 2 | .73 | .91 | .87 | .81 | |

| 3 | .55 | .94 | .81 | .81 | |

| 4 | .48 | .98 | .79 | .90 | |

| 5 | .38 | .99 | .76 | .94 | |

| 6 | .25 | .99 | .73 | .99 | |

| 7 | .18 | .99 | .71 | .99 | |

| 8 | .13 | .99 | .70 | .99 | |

| 9 | .05 | .99 | .68 | .99 | |

| 10 | .- | .99 | .67 | - |

Note: SNSI dichotomous version identifying current nonsuicidal self-injury disorder (NSSI disorder) as assessed by the Clinician-Administered NSSI Disorder Index (CANDI), bolded values indicate optimal cut-point based on Youden’s statistic maximizing sensitivity and specificity values; NPV = negative predictive value, PPV = positive predictive value, AUC = area under the curve, CI = confidence interval.

Figure 1.

Comparison of Full-Length Initial SNSI and Brief SNSI Predicting Current Nonsuicidal Self-Injury Disorder.

Note: SNSI predicting current nonsuicidal self-injury disorder as assessed by the Clinician-Administered NSSI Disorder Index (CANDI). No significant differences between area under the curve (AUC) values (all Venkatraman’s tests p>.05).

Continuous items.

The current NSSI disorder group also had significantly higher SNSI continuous frequency scores (M = 11.33, SD = 9.52), compared to the non-NSSI disorder group (M = 1.08, SD = 2.98, t (42.86) = 6.65, p <.001). The AUC value for the SNSI continuous frequency scores identifying current NSSI disorder was excellent (.91, 95% CI [.85, .97]). The continuous items of the SNSI also demonstrated good properties as a screen with an optimal cut point of one (sensitivity = .93, specificity = .78, NPV = .95, PPV = .67). Furthermore, there were no significant differences between the initial 16-item SNSI version and the final 10-item version in predicting current NSSI disorder on the CANDI (AUC = .91, 95% CI [.85, .97]; Venkatraman’s bootstrapped test p = .42; see Figure 1).

Comparison with DSHI.

The utility of the dichotomous SNSI items for identifying current NSSI disorder on the CANDI was compared with that of the DSHI (AUC = .91, 95% CI [.84, .97]), with no significant differences observed (Venkatraman’s bootstrapped test, p = .30). Similarly, comparison of the continuous frequency SNSI items with the DSHI in relation to identifying current NSSI disorder on the CANDI revealed no significant differences (Venkatraman’s bootstrapped test, p = .28). The DSHI identified 47 individuals engaging in current NSSI while the SNSI identified an additional 12 individuals (n = 59) engaging in current NSSI reflecting an increased detection rate of 26%.

Comparison of dichotomous and continuous items.

No significant differences were observed in the predictive validity of the dichotomous and continuous frequency items of the SNSI within this sample with respect to identifying current NSSI disorder on the CANDI (Venkatraman’s bootstrapped test, p = .73; see Figure 1). Given evidence of comparable construct validity between the dichotomous and continuous frequency items of the SNSI, as well as the goal of using the SNSI as a screening measure, subsequent analyses focus on the dichotomous behavior items of the SNSI (see Appendix A). Results of analyses based on the continuous frequency items of the SNSI (see Appendix B) are presented in the Supplementary Materials.

Comparison of SNSI scores among different demographic groups.

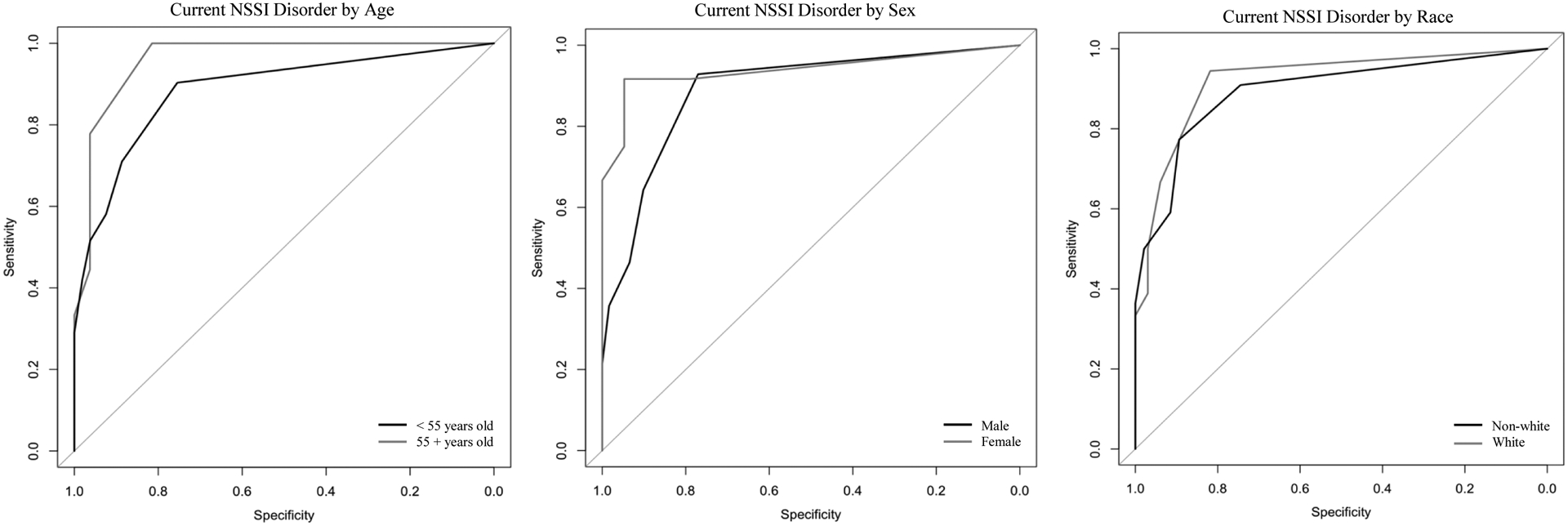

The utility of the SNSI with respect to identifying current NSSI disorder on the CANDI was compared among age, sex assigned at birth, and race groups (see Figure 2). There were no significant differences in AUC values between veterans older than 55 (.96, 95% CI [.91, .99]) and veterans younger than 55 (.89, 95% CI [.81, .96], Venkatraman’s bootstrapped test p = .64); male veterans (.89, 95% CI [.82, .96]) and female veterans (.94, 95% CI [.84, .99], Venkatraman’s bootstrapped test p = .77); and veterans identifying racially as white (.92, 95% CI [.84, .99]) and non-white (i.e., Black, Asian; .89, 95% CI [.81, .98], Venkatraman’s bootstrapped test p = .85). See Supplementary Table 2 for comparisons across age, sex assigned at birth, and race for the continuous frequency items of the SNSI.

Figure 2.

Comparison of SNSI (Dichotomous) Predicting Nonsuicidal Self-Injury Disorder by Age, Sex Assigned at Birth, and Race

Note: SNSI predicting current NSSI disorder as assessed by the Clinician-Administered NSSI Disorder Index (CANDI); NSSI = nonsuicidal self-injury, Sex = sex assigned at birth; No significant differences between area under the curve (AUC) values (all Venkatraman’s tests p>.05).

Convergent, Divergent, and External Validity

Table 4 presents correlations of the dichotomous and continuous frequency scores of the SNSI with the validity measures. Support was provided for the construct validity of the SNSI scores, which evidenced significant large correlations with past-year NSSI on the C-SSRS and past-year NSSI on the DSHI (rs = .59 – .90, p <.001). SNSI scores demonstrated small to moderate associations (rs .04 – .42, ps <.05) with divergent validity measures (i.e., BSS, PHQ-9, and UPPS-P subscale scores). Correlations of the SNSI scores with the divergent validity measures were compared to the correlations of the SNSI scores with the construct validity measures (i.e., DSHI and C-SSRS NSSI behaviors; see Diedenhofen & Musch, 2015). All correlations of the SNSI scores with the construct validity measures were significantly stronger (all ps <.05) than the correlations with the divergent validity measures. Finally, support was provided for the external validity of the SNSI, with moderate to large correlations found between both the dichotomous and continuous frequency SNSI scores and the WHODAS and SDS total and subscale scores (total scale rs .33 – .49, ps< .05; subscale rs .21 – .45).

Table 4.

SNSI Convergent, Divergent, and External Validity

| Group Differences | Correlations | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Current NSSI Disordera | No Current NSSI Disorder | p | Dichotomous SNSI Items | p | Continuous SNSI Items | p | |

| SNSI | |||||||

| Dichotomous Items | 3.65 ± 2.68 | 0.41 ± 0.96 | <.01 | - | - | .93 | <.01 |

| Continuous Items | 11.33 ± 9.52 | 1.08 ± 2.98 | <.01 | .93 | <.01 | - | - |

| Convergent Validity Measures | |||||||

| C-SSRS NSSI Behaviorsb | 97.6% (40) | 1.20% (1) | <.01 | .59 | <.01 | .54 | <.01 |

| DSHI Total | 3.24 ± 2.28 | 0.28 ± 0.72 | <.01 | .90 | <.01 | .82 | <.01 |

| Divergent Validity Measures | |||||||

| BSS Total | 8.24 ± 8.25 | 2.49 ± 5.10 | <.01 | .33 | <.01 | .27 | .02 |

| PHQ-9 Total | 16.26 ± 6.01 | 10.66 ± 6.60 | <.01 | .42 | <.01 | .44 | <.01 |

| UPPS-P | |||||||

| Negative Urgency | 2.63 ± 0.50 | 2.46 ± 0.58 | .12 | .24 | .01 | .29 | <.01 |

| Lack of Premeditation | 2.08 ± 0.51 | 1.99 ± 0.47 | .31 | .19 | .06 | .20 | .02 |

| Lack of Perseverance | 2.23 ± 0.53 | 2.06 ± 0.54 | .10 | .21 | .02 | .24 | <.01 |

| Sensation Seeking | 2.48 ± 0.62 | 2.47 ± 0.68 | .94 | .06 | .65 | .04 | .69 |

| Positive Urgency | 2.03 ± 0.64 | 2.01 ± 0.54 | .82 | .10 | .34 | .15 | .21 |

| External Validity Measures | |||||||

| WHODAS Total | 24.06 ± 15.19 | 17.83 ± 12.77 | .08 | .33 | .02 | .26 | .03 |

| WHODAS (no work items) | 25.55 ± 15.08 | 18.49 ± 12.42 | <.01 | .37 | <.01 | .35 | <.01 |

| Sheehan Disability Total | 11.09 ± 7.72 | 2.33 ± 5.98 | <.01 | .49 | <.01 | .44 | <.01 |

| Days lost | 3.71 ± 6.17 | 0.47 ± 3.65 | <.01 | .33 | .02 | .27 | .04 |

| Days unproductive | 5.73 ± 7.71 | 0.47 ± 3.24 | <.01 | .43 | <.01 | .45 | <.01 |

| Family | 4.29 ± 3.43 | 0.82 ± 2.21 | <.01 | .45 | <.01 | .43 | <.01 |

| Social | 5.12 ± 3.71 | 0.92 ± 2.29 | <.01 | .53 | <.01 | .51 | <.01 |

| Work | 1.82 ± 2.89 | 0.63 ± 2.08 | .04 | .21 | .03 | .11 | .22 |

Note:

current nonsuicidal self-injury disorder (NSSI disorder) as assessed by the Clinician-Administered NSSI Disorder Index (CANDI),

dichotomous variable, assessed with chi-square tests, t-tests used for all other continuous variables to assess group comparisons; Mean ± standard deviation; NSSI = nonsuicidal self-injury, p = p-value, C-SSRS = Columbia Suicide Severity Rating Scale, NSSI = nonsuicidal self-injury, BSS = Beck Scale for Suicide Ideation, PHQ-9 = Patient Health Questionnaire-9, UPPS-P = Urgency-Premeditation-Perseverance-Sensation Seeking-Positive Urgency Scale, WHODAS = World Health Organization Disability Assessment Schedule 2.0.

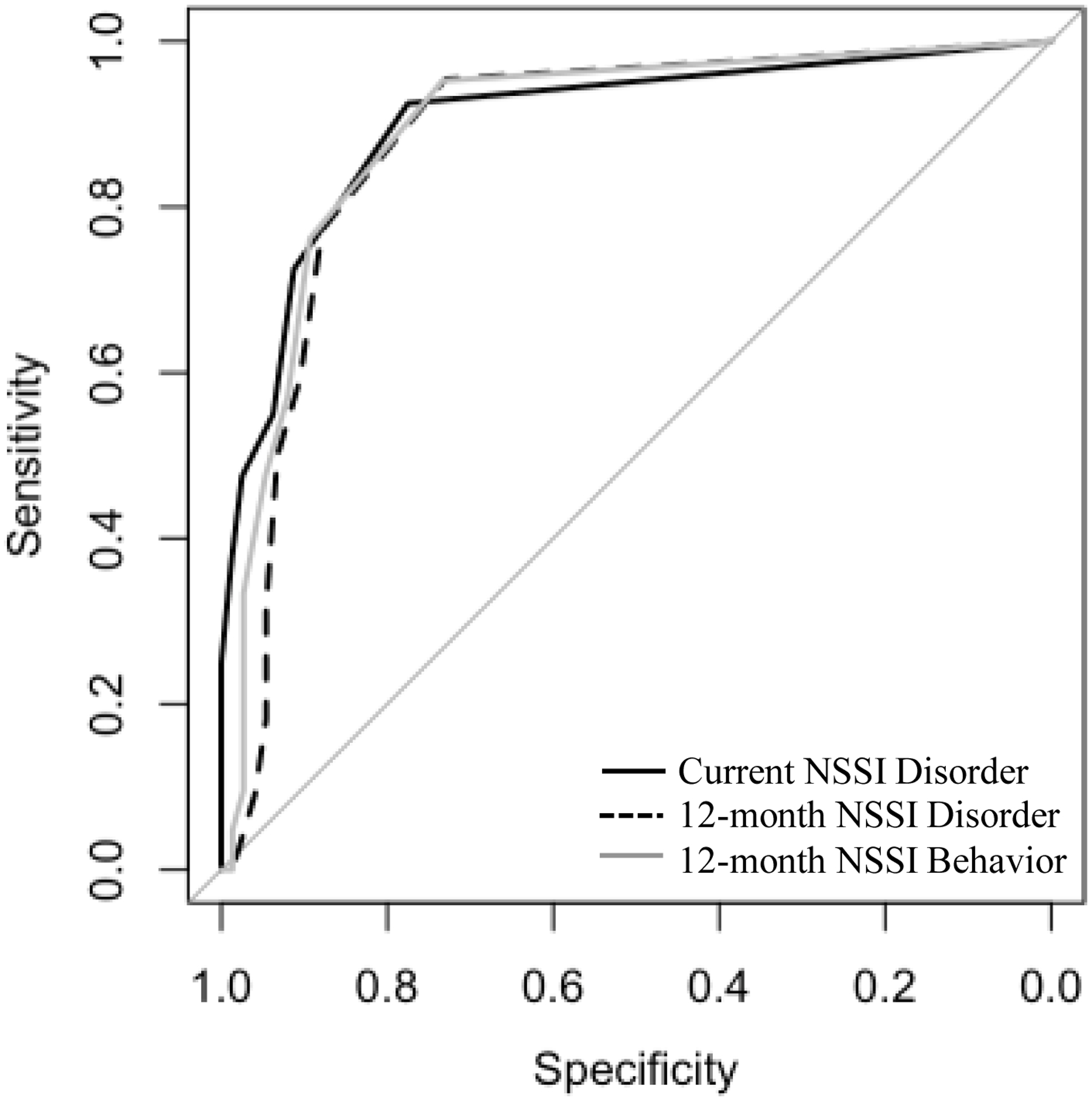

Predictive Validity

The SNSI scores demonstrated strong predictive validity with CANDI-assessed NSSI disorder (AUC = .88, 95% CI [.81, .96]) and C-SSRS NSSI behaviors (AUC = .90, 95% CI [.82, .97]) 12-months later, see Figure 3 and Supplementary Table 3.

Figure 3.

Predictive Validity of the SNSI (Dichotomous)

Note: SNSI dichotomous items predicting current Nonsuicidal Self-Injury Disorder (NSSI disorder), NSSI disorder assessed 12 months after baseline, and Columbia Suicide Severity Rating Scale (C-SSRS) NSSI assessed 12 months after baseline. NSSI disorder assessed at baseline and 12 months after baseline with the Clinician-Administered NSSI Disorder Index (CANDI).

Discussion

This initial development and validation study provides support for the SNSI as a brief, efficient, and psychometrically robust screen for identifying NSSI behaviors in primary care settings among clinically diverse patients. The SNSI was developed to screen for common NSSI behaviors, including those with high prevalence among male adults and veterans, in order to address the persistent under-identification of NSSI within this group (Kimbrel et al., 2017). In addition to demonstrating good internal consistency, strong construct and convergent validity, and good external validity, SNSI scores demonstrated predictive validity with respect to both NSSI behaviors and NSSI disorder one year later. Speaking to the utility of this screening measure for diverse groups of patients, performance of the SNSI was not influenced by patient age, sex assigned at birth, or race.

Although there are currently several validated clinical interviews and self-report measures of NSSI characteristics, the SNSI fills an important gap in NSSI assessment at the early identification stage (i.e., use as a screen). A brief and efficient screen is critical for the development of clinical pathways for patients currently engaging in NSSI behaviors who may benefit from identification and referral for more comprehensive NSSI assessments (e.g., CANDI interview) and treatment. Whereas other measures of NSSI include items with high endorsement rates among male adults (e.g., Direct and Indirect Self-Harm Inventory; Green et al., 2017), the SNSI is comparatively brief and, importantly, demonstrates predictive validity in relation to future NSSI and NSSI disorder. Although findings within this unique sample of veterans with particularly clinically significant NSSI (as evidenced by the high degree of overlap between NSSI behaviors and NSSI disorder) provided some initial evidence in support of the potential utility of the SNSI in identifying patients with NSSI disorder, these findings were likely influenced by the high degree of overlap between NSSI behaviors and NSSI disorder. Thus, the present sample and may not generalize to samples with a greater percentage of individuals with NSSI who do not meet criteria for NSSI disorder and the current study cannot speak to the diagnostic utility of the SNSI in predicting NSSI disorder among individuals with a range of NSSI.

Given the current rate of missed NSSI behaviors, especially among male adults (Kimbrel et al., 2017; Turner et al., 2019), there is presently a very real need for healthcare systems to begin routinely screening for NSSI behaviors. Not only are NSSI behaviors strongly associated with functional impairment (Selby et al., 2012; Selby et al., 2015; Turner et al., 2019), NSSI was recently identified as the top longitudinal predictor of suicide attempts in a meta-analysis of the past 50 years of research on risk factors for suicide (Franklin et al., 2017). As such, systematic screening for NSSI behaviors in healthcare systems and primary care settings may substantially increase the predictive validity of suicide risk algorithms based on electronic health records (EHR) data (as it is likely that many instances of NSSI are not being adequately captured in EHR currently). Furthermore, the SNSI may help identify individuals in need of more comprehensive assessment (e.g., clinical interview) and possible treatment. Given evidence suggesting that, at least within this sample, the optimal cut point on the SNSI is a one, future work should explore the utility of a single item version of the SNSI to further improve its efficiency (e.g., by combining the most commonly endorsed methods to a single item).

Study Limitations

Despite providing preliminary support for the SNSI as a brief and efficient screen, several limitations of the present study must be considered. Although close adherence to the Standards for Reporting of Diagnostic Accuracy (STARD) guidelines was emphasized, true masking of the index test (i.e., SNSI) to the reference standard (i.e., CANDI) was not possible due to ethical and safety considerations (Bossuyt et al., 2003). Given the strong relationship between NSSI behaviors and suicidality, clinical interviewers reviewed all sources of information for potential risk. This practice, although recommended and standard in NSSI research, may have inflated AUC estimates (e.g., Lloyd-Richardson et al., 2015; Singhal & Bhola, 2017). Efforts to reduce diagnostic accuracy bias, given the absence of masking, included use of a diagnostically complex sample (versus a distilled or healthy control design) and use of a longitudinal design to estimate predictive diagnostic accuracy (i.e., baseline SNSI predicting future NSSI behaviors). However, future work is needed to examine SNSI diagnostic accuracy estimates utilizing true rater masking. Another limitation of the present study is the absence of a test-retest estimate. Study visits were spaced one year apart precluding an appropriate timeframe to establish test-retest reliability estimates. In addition, although scores on the SNSI demonstrated strong construct and predictive validity with respect to NSSI disorder on the CANDI, there was limited variability in the severity of NSSI in the present sample, with most patients who endorsed NSSI in the past year also meeting criteria for NSSI disorder. Thus, it is not possible to differentiate the presence of past year NSSI from the presence of NSSI disorder within the current sample, precluding determination of the diagnostic utility of the SNSI in predicting NSSI disorder. Future research examining the diagnostic accuracy of SNSI scores with respect to NSSI disorder within a sample with more variable NSSI severity is needed. Additionally, future research is needed to examine the diagnostic utility of the SNSI in identifying NSSI disorder within a sample of individuals with NSSI.

Conclusion

Notwithstanding these limitations, the present study provides support for the SNSI as a brief, promising new screen for NSSI behaviors prevalent in both male and female adults. The SNSI demonstrated good psychometric properties in a demographically and clinically diverse sample. Additionally, the SNSI can be flexibly administered and scored to assess the presence versus absence of specific NSSI behaviors (i.e., dichotomous items) or the frequency of endorsed NSSI behaviors (i.e., continuous frequency items). The SNSI was designed for use as a brief initial self-report screen in primary care settings to identify high-risk individuals in need of more comprehensive NSSI assessment. Given its briefer administration time and straightforward instructions, as well as its comparable performance of the two SNSI versions, we recommend utilization of the dichotomous version of the SNSI in standard clinical settings; conversely, the continuous frequency version may be preferable in research settings or in the context of NSSI-specific treatments. Results of this study support the utility of the SNSI as an efficient screen for NSSI behaviors in both male and female adults and an important first step in developing clinical pathways (e.g., additional assessment and allocation of clinical resources) for patients with clinically significant NSSI.

Supplementary Material

Funding Statement:

This research was supported by a Merit Award to Dr. Kimbrel from the Clinical Sciences Research and Development Service of the Department of Veterans Affairs Office of Research and Development (#I01CX001486). Dr. Beckham was funded by a Senior Research Career Scientist award from VA Clinical Sciences Research and Development (IK6BX00377). Dr. Halverson was supported by a VA Office of Academic Affiliations Advanced Fellowship in Mental Illness Research and Treatment.

Appendix A. The Screen for Nonsuicidal Self-Injury (SNSI) Dichotomous Items

Sometimes people also hurt themselves on purpose when they do not want to die. For example, they might hurt themselves because it helps them to feel better when they’re upset, or because they want to punish themselves, or because they want to feel something. This type of self-injury is referred to as nonsuicidal self-injury because it involves injuring yourself on purpose when you don’t want to die. The following questions will ask you about different forms of nonsuicidal self-injury you may have used to hurt yourself on purpose when you were not suicidal.

Please indicate whether you have done any of the following during the past year:

| Screen for Nonsuicidal Self-injury (SNSI) Items | ||

|---|---|---|

| Have you ever intentionally cut yourself (e.g., on your wrists, legs, or torso)? | No | Yes |

| Have you ever intentionally burned yourself (e.g., with a lighter or cigarette)? | No | Yes |

| Have you ever intentionally scratched yourself to the point that you bled, or it left a mark? | No | Yes |

| Have you ever intentionally bitten your cheeks, lips, or other parts of your body to the point of bleeding or breaking the skin? | No | Yes |

| Have you ever intentionally stuck sharp objects (e.g., needles, pins, staples) into your skin? | No | Yes |

| Have you ever intentionally banged your head against walls or objects to the point of bruising or bleeding? | No | Yes |

| Have you ever intentionally punched or hit yourself to the point of bruising or bleeding? | No | Yes |

| Have you ever intentionally punched or hit walls or objects to the point of bruising or bleeding? | No | Yes |

| Have you ever intentionally prevented wounds from healing? | No | Yes |

| Have you ever done anything else to intentionally hurt or mutilate your body on purpose that resulted in tissue damage (e.g., bruising or bleeding)? Please specify: ________________________________________________________ |

No | Yes |

Scoring: “No” = 0, “Yes” = 1. Items are summed for a total score (range 0–10). Scores >1 indicate high-risk for NSSI disorder. Replacing “the past year” with “your lifetime” can be done to screen for lifetime NSSI behaviors. Note: if method(s) specified in last item are not examples of nonsuicidal self-injury (e.g., suicide attempt), item to be scored as a “No” = 0.

Appendix B. The Screen for Nonsuicidal Self-Injury (SNSI) Continuous Items

Sometimes people also hurt themselves on purpose when they don’t want to die. For example, they might hurt themselves because it helps them to feel better when they’re upset, or because they want to punish themselves, or because they want to feel something. This type of self-injury is referred to as nonsuicidal self-injury because it involves injuring yourself on purpose when you don’t want to die. The following questions will ask you about different forms of nonsuicidal self-injury you may have used to hurt yourself on purpose when you were not suicidal. Each question asks if you have ever hurt yourself in a particular way during your lifetime, and, if so, how many times. You will also be asked about the past year. Please answer each question as honestly and as accurately as you can.

| Screen for Nonsuicidal Self-injury (SNSI) Items | During the past year? | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| If yes, how many times? | |||||||

| Have you ever intentionally cut yourself (e.g., on your wrists, legs, or torso)? | No | Yes | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5+ |

| Have you ever intentionally burned yourself (e.g., with a lighter or cigarette)? | No | Yes | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5+ |

| Have you ever intentionally scratched yourself to the point that you bled, or it left a mark? | No | Yes | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5+ |

| Have you ever intentionally bitten your cheeks, lips, or other parts of your body to the point of bleeding or breaking the skin? | No | Yes | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5+ |

| Have you ever intentionally stuck sharp objects (e.g., needles, pins, staples) into your skin? | No | Yes | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5+ |

| Have you ever intentionally banged your head against walls or objects to the point of bruising or bleeding? | No | Yes | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5+ |

| Have you ever intentionally punched or hit yourself to the point of bruising or bleeding? | No | Yes | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5+ |

| Have you ever intentionally punched or hit walls or objects to the point of bruising or bleeding? | No | Yes | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5+ |

| Have you ever intentionally prevented wounds from healing? | No | Yes | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5+ |

| Have you ever done anything else to intentionally hurt or mutilate your body on purpose that resulted in tissue damage (e.g., bruising or bleeding)? Please specify: ________________________________________________________ |

No | Yes | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5+ |

Scoring: “No” = 0, “1” = 1, “2” = 2, “3” = 3, “4” = 4, “5+” = 5. Items are summed for a total score (range 0 – 50). Scores >1 indicate high-risk for Nonsuicidal Self-Injury Disorder. Note: if method(s) specified in last item are not examples of nonsuicidal self-injury (e.g., suicide attempt), item to be scored as a “No” = 0.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Disclosure: The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position or policy of the United States Government or Department of Veterans Affairs (VA). The authors have no other conflicts of interest to disclose.

Ethics Approval Statement: This research was approved by the Durham Veterans Affairs Health Care System Institutional Review Board. All participants provided informed consent.

References

- American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). https://doi.org/10/1176/appi/books.9780890425596 [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Brown GK, & Steer RA (1997). Psychometric characteristics of the Scale for Suicide with psychiatric outpatients. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 35, 1039–1046. 10.1016/S0005-7967(97)00073-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Kovacs M, & Weissman A (1979). Assessment of suicidal intention: The Scale for Suicide Ideation. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 47, 343–352. 10.1037//0022-006x.47.2.343 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bentley KH, Cassiello-Robbins CF, Vittorio L, Sauer-Zavala S, & Barlow DH (2015). The association between nonsuicidal self-injury and the emotional disorders: A meta-analytic review. Clinical Psychology Review, 37, 72–88. 10.1016/j.cpr.2015.02.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bliese PD, Wright KM, Adler AB, Cabrera O, Castro CA, & Hoge CW (2008). Validating the Primary Care Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Screen and the Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Checklist with soldiers returning from combat. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 76, 272–281. 10.1037/0022-006X.76.2.272 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bossuyt PM, Reitsma JB, Bruns DE, Gatsonis CA, Glasziou PP, Irwig LM, Moher D, Rennie D, De Vet HCW, & Lijmer JG (2003). The STARD Statement for reporting studies of diagnostic accuracy: Explanation and elaboration. Annals of Internal Medicine, 138, w1–w12. 10.7326/0003-4819-138-1-200301070-00012-w1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bresin K, & Schoenleber M (2015). Gender differences in the prevalence of nonsuicidal self-injury: A meta-analysis. Clinical Psychology Review, 38, 55–64. 10.1016/j.cpr.2015.02.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diedenhofen B, & Musch J (2015). Cocor: A comprehensive solution for the statistical comparison of correlations. PLoS ONE, 10, 1–12. 10.1371/journal.pone.0121945 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- First MB, Williams JBW, Karg RS, Spitzer RL (2015). Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-5—Research Version. 1–6. 10.1002/9781118625392.wbecp351 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Franklin JC, Ribeiro JD, Fox KR, Bentley KH, Kleiman EM, Huang X, Musacchio KM, Jaroszewski AC, Chang BP, & Nock MK (2017). Risk factors for suicidal thoughts and behaviors: A meta-analysis of 50 years of research. Psychological Bulletin, 143, 187–232. 10.1037/bul0000084 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gratz KL (2001). Measurement of deliberate self-harm: Preliminary data on the Deliberate Self-Harm Inventory. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment, 23, 253–263. 10.1023/A:1012779403943 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gratz KL, Dixon-Gordon KL, Chapman AL, & Tull MT (2015). Diagnosis and characterization of DSM-5 nonsuicidal self-injury disorder using the Clinician-Administered Nonsuicidal Self-Injury Disorder Index. Assessment, 22, 527–539. 10.1177/1073191114565878 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green JD, Hatgis C, Kearns JC, Nock MK, & Marx BP (2017). The Direct and Indirect Self-Harm Inventory (DISH): A new measure for assessing high-risk and self-harm behaviors among military veterans. Psychology of Men and Masculinity, 18, 208–214. 10.1037/men0000116 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- International Society for the Study of Self-Injury. (2018). What is self-injury? https://itriples.org/about-self-injury/what-is-self-injury.

- Kimbrel NA, Calhoun PS, & Beckham JC (2017). Nonsuicidal self-injury in men: A serious problem that has been overlooked for too long. World Psychiatry, 16, 108–109. 10.1002/wps.20357 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimbrel NA, Gratz KL, Tull MT, Morissette SB, Meyer EC, DeBeer BB, Silvia PJ, Calhoun PC, & Beckham JC (2015). Nonsuicidal self-injury as a predictor of active and passive suicidal ideation among Iraq/Afghanistan war veterans. Psychiatry Research, 227, 360–362. 10.1016/j.psychres.2015.03.026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimbrel NA, Thomas SP, Hicks TA, Hertzberg MA, Clancy CP, Elbogen EB, Meyer EC, DeBeer BB, Gross GM, Silvia PJ, Morissette SB, Gratz KL, Calhoun PS, & Beckham JC (2018). Wall/object punching: An important but under-recognized form of nonsuicidal self-injury. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior, 48, 501–511. 10.1111/sltb.12371 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klonsky ED (2011). Nonsuicidal self-injury in United States adults: Prevalence, sociodemographics, topography and functions. Psychological Medicine, 41, 1981–1986. 10.1017/S0033291710002497 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klonsky DE, May AM, & Glenn CR (2013). The relationship between nonsuicidal self-injury and attempted suicide: Converging evidence from four samples. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 122, 231–237. 10.1037/a0030278 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, & Williams JBW (2001). The PHQ-9: Validity of a brief depression severity measure. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 16, 606–613. 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lear MK, Penzenik ME, Forster JE, Starosta A, Brenner LA, & Nazem S (2021). Characteristics of nonsuicidal self-injury among veterans. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 77, 286–297. 10.1002/jclp.23027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lloyd-Richardson EE, Lewis SP, Whitlock JL, Rodham K, & Schatten HT (2015). Research with adolescents who engage in non-suicidal self-injury: Ethical considerations and challenges. Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and Mental Health, 9, 1–14. 10.1186/s13034-015-0071-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matarazzo BB, Brown GK, Stanley B, Forster JE, Billera M, Currier GW, Ghahramanlou-Holloway M, & Brenner LA (2019). Predictive validity of the Columbia-Suicide Severity Rating Scale among a cohort of at-risk veterans. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior, 49, 1255–1265. 10.1111/sltb.12515 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monteith LL, Holliday R, Miller C, Schneider AL, Hoffmire CA, Bahraini NH, & Forster JE (2020). Suicidal ideation, suicide attempt, and non-suicidal self-injury among female veterans: Prevalence, timing, and onset. Journal of Affective Disorders, 273, 350–357. 10.1016/j.jad.2020.04.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nock MK (2010). Self-Injury. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 6, 339–363. 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.121208.131258 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nock MK, Holmberg EB, Photos VI, & Michel BD (2007). Self-Injurious Thoughts and Behaviors Interview: Development, reliability, and validity in an adolescent sample. Psychological Assessment, 19, 309–317. 10.1037/1040-3590.19.3.309 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel TA, Mann AJD, Blakey SM, Aunon FM, Calhoun PS, Beckham JC, & Kimbrel NA (2021). Diagnostic correlates of nonsuicidal self-injury disorder among veterans with psychiatric disorders. Psychiatry Research, 296, 113672. 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113672 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Posner K, Brown GK, Stanley B, Brent DA, Yershova KV, Oquendo MA, Currier GW, Melvin GA, Greenhill L, Shen S, & Mann JJ (2011). The Columbia-Suicide Severity Rating Scale: Initial validity and internal consistency findings from three multisite studies with adolescents and adults. American Journal of Psychiatry, 168, 1266–1277. 10.1176/appi.ajp.2011.10111704 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Resnick HS, & Weaver T (1994). Habit Questionnaire. Charleston (SC): Medical University of South Carolina. [Google Scholar]

- Ribeiro JD, Franklin JC, Fox KR, Bentley KH, Kleiman EM, Chang BP, & Nock MK (2016). Self-injurious thoughts and behaviors as risk factors for future suicide ideation, attempts, and death: A meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Psychological Medicine, 46, 225–236. 10.1017/S0033291715001804 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sansone RA, Wiederman MW, & Sansone LA (1998). The Self-Harm Inventory (SHI): Development of a scale for identifying self-destructive behaviors and borderline personality disorder. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 54, 973–983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selby EA, Bender TW, Gordon KH, Nock MK, & Joiner TE (2012). Nonsuicidal self-injury (NSSI) disorder: A preliminary study. Personality Disorders: Theory, Research, and Treatment, 3, 167–175. 10.1037/a0024405 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selby EA, Kranzler A, Fehling KB, & Panza E (2015). Nonsuicidal self-injury disorder: The path to diagnostic validity and final obstacles. Clinical Psychology Review, 38, 79–91. 10.1016/j.cpr.2015.03.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheehan DV, Harnett-Sheehan K, & Raj BA (1996). The measurement of disability. In International Clinical Psychopharmacology (Vol. 11, Issue Suppl 3, pp. 89–95). Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. 10.1097/00004850-199606003-00015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singhal N, & Bhola P (2017). Ethical practices in community-based research in non-suicidal self-injury: A systematic review. Asian Journal of Psychiatry, 30, 127–134. 10.1016/j.ajp.2017.08.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swannell SV, Martin GE, Page A, Hasking P, & St John NJ (2014). Prevalence of nonsuicidal self-injury in nonclinical samples: Systematic review, meta-analysis and meta-regression. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior, 44, 273–303. 10.1111/sltb.12070 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Titov N, Dear BF, McMillan D, Anderson T, Zou J, & Sunderland M (2011). Psychometric comparison of the PHQ-9 and BDI-II for measuring response during treatment of depression. Cognitive Behaviour Therapy, 40, 126–136. 10.1080/16506073.2010.550059 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner BJ, Kleiman EM, & Nock MK (2019). Nonsuicidal self-injury prevalence, course, and association with suicidal thoughts and behaviors in two large, representative samples of US Army soldiers. Psychological Medicine, 49, 1470–1480. 10.1017/S0033291718002015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ustun TB, Kostanjesek N, Chatterji S, Rehm J, & Organization W. H. (n.d.). Measuring health and disability : Manual for WHO Disability Assessment Schedule (WHODAS 2.0) / edited by Üstün TB, Kostanjsek N, Chatterji S, Rehm J. World Health Organization. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/43974 [Google Scholar]

- Ward-Ciesielski EF, Schumacher JA, & Bagge CL (2016). Relations between nonsuicidal self-injury and suicide attempt characteristics in a sample of recent suicide attempters. Crisis, 37, 310–313. 10.1027/0227-5910/a000400 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wester K, Trepal H, & King K (2018). Nonsuicidal self-injury: Increased prevalence in engagement. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior, 48, 690–698. 10.1111/sltb.12389 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whiteside SP, & Lynam DR (2001). The five factor model and impulsivity: Using a structural model of personality to understand impulsivity. Personality and Individual Differences, 30, 669–689. 10.1016/S0191-8869(00)00064-7 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Whitlock J, Exner-Cortens D, & Purington A (2014). Assessment of nonsuicidal self-injury: Development and initial validation of the Non-Suicidal Self-Injury-Assessment Tool (NSSI-AT). Psychological Assessment, 26, 935–946. 10.1037/a0036611 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitlock J, Exner-Cortens D, & Purington A (2021). The Brief Non-Suicidal Self-Injury Assessment Tool (BNSSI-AT). http://www.selfinjury.bctr.cornell.edu/perch/resources/bnssi-at-revised-final-2.26.2018.pdf [DOI] [PubMed]

- Youden WJ (1950). Index for rating diagnostic tests. Cancer, 3, 32–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.