Abstract

Study Objectives:

Medications for opioid use disorder (MOUD) prescribed in the Emergency Department (ED) have the potential to save lives and help people start and maintain recovery. We sought to explore patient perspectives regarding the initiation of buprenorphine and methadone in the ED with the goal of improving interactions and fostering shared decision-making (SDM) around these important treatment options.

Methods:

We conducted semi-structured interviews with a purposeful sample of people with Opioid Use Disorder (OUD) regarding ED visits and their experiences with MOUD. The interview guide was based on the Ottawa Decision Support Framework, a framework for examining decisional needs and tailoring decisional support, and the research team’s experience with MOUD and SDM. Interviews were recorded, transcribed, and analyzed in an iterative process using both the Ottawa Framework and a social-ecological framework. Themes were identified and organized and implications for clinical care were noted and discussed.

Results:

Twenty-six participants were interviewed, 7 in-person in the ED and 19 via video conferencing software. The majority had tried both buprenorphine and methadone, and almost all had been in an ED for an issue related to opioid use. Participants reported social, pharmacological, and emotional factors that played into their decision-making. Regarding buprenorphine, they noted advantages such as its efficacy and logistical ease, and disadvantages such as the need to wait to start it (risk of precipitated withdrawal) and that one could not use other opioids while taking it. Additionally, participants felt: 1. Both buprenorphine and methadone should be offered; 2. Because “one person’s pro is another person’s con,” clinicians will need to understand the facets of the options; 3. Clinicians will need to have these conversations without appearing judgmental; 4. Many patients may not be “ready” for MOUD, but it should still be offered.

Conclusions:

Although participants were supportive of offering buprenorphine in the ED, many felt methadone should also be offered. They felt that treatment should be tailored to an individual’s needs and circumstances, and clarified what factors might be important considerations for people with OUD.

Keywords: buprenorphine, MOUD, OUD, methadone, qualitative, shared decision-making, decision aid, conversation aid

Introduction

Deaths due to opioid overdose have continued to rise in the United States (US).1 Medications for Opioid Use Disorder (MOUD), including methadone and buprenorphine, are the most effective means to decrease future illicit opioid use and death.2–5 The initiation of MOUD, specifically buprenorphine, in low barrier environments where patients with OUD seek care, such as the Emergency Department (ED), have been shown to be feasible, safe and effective, even in resource-constrained settings.3,6,7

Despite thousands of ED visits annually for opioid overdoses and injection-related medical concerns and increasing data supporting the practice, few patients with OUD are started on buprenorphine during or immediately after an ED visit – in one study, less than 5% of over 6000 patients discharged from the ED after a non-fatal overdose filled a prescription for buprenorphine in the subsequent 90 days.8–11 To understand why the implementation of ED-based buprenorphine has lagged, research has focused on clinician-reported barriers to administering buprenorphine, including regulatory requirements, lack of training and infrastructure, discomfort and stigma, and perceived lack of appropriate follow-up care.11–19 However, the decision to initiate buprenorphine or methadone also involves patients, who have their own beliefs, preferences, and perspectives. Shared decision-making (SDM) puts patients at the center of clinical decisions.20 In other medical conditions, SDM has been shown to increase knowledge, trust, and adherence.21–23 An SDM framework that fosters conversations and addresses common misperceptions around the initiation of MOUD may improve the patient-provider interaction and ultimately increase ED-based MOUD administration.

Based on previous SDM literature, our conceptual framework posits that creating a conversation aid could increase provider comfort with initiating MOUD, and increase trust, knowledge and engagement for patients, leading to an increase in MOUD initiation and potentially adherence.15,20–23 (Supplementary Material A) As a first step towards the goal of fostering SDM around the treatment of OUD, we sought to explore and understand patient perspectives regarding the initiation of buprenorphine and methadone in the ED. Our rationale is that a better understanding of patients’ perspectives could help improve the quality of patient-centered conversations around the treatment of OUD, increase initiation of MOUD in the ED, and increase patient engagement and adherence to treatment following discharge. Although our initial plan was to examine perspectives around buprenorphine initiation, participants’ input encouraged us to include methadone as part of this inquiry.

Methods

Study Design

As few studies have addressed the needs of patients with OUD in the ED,24 and none have sought to foster SDM around ED MOUD treatment decisions, we used exploratory qualitative methods to conduct semi-structured interviews with people with OUD about their experiences with OUD, the ED, MOUD, and other facets of recovery.

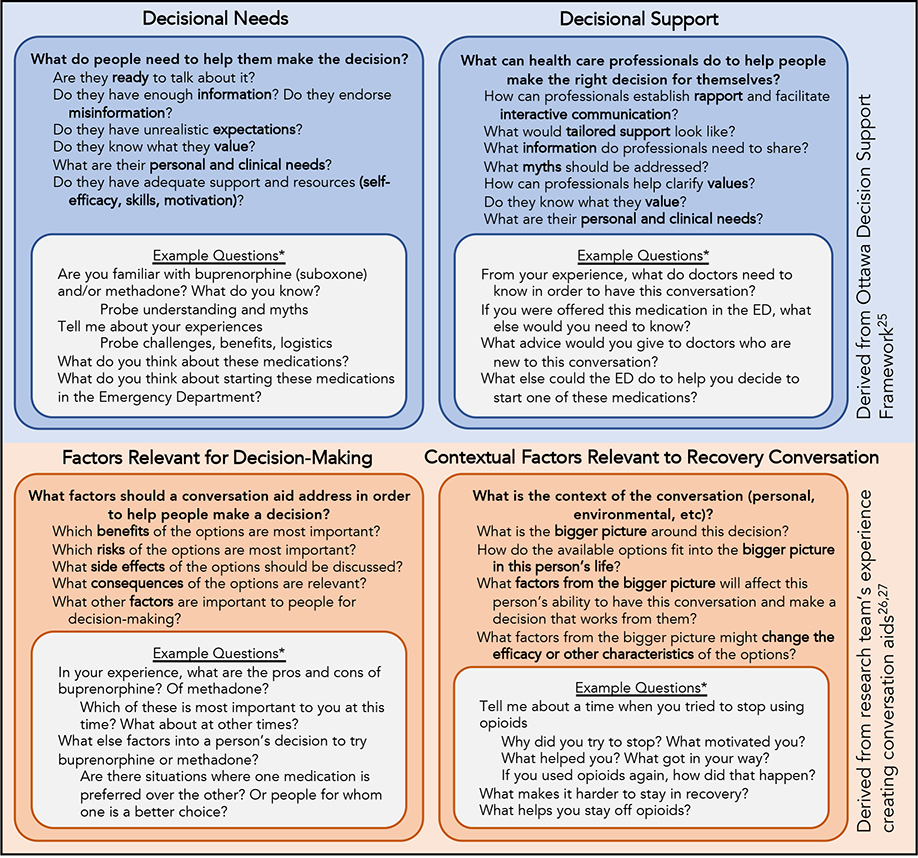

The interview guide was informed by the Ottawa Decision Support Framework, which posits that the first steps in fostering SDM require understanding decisional needs and then tailoring decision support.25 Based on the research team’s experience creating decision aids, two other domains were included in our framework: Factors Relevant for Decision-Making and Contextual Factors Relevant to Recovery Conversation.26,27 (Figure 1)

Figure 1.

Theoretical Framework for Interview Guide

*Examples only. Interview Guide can be found in Supplementary Materials

ED = Emergency Department

Interviews began with questions about the participant’s history of opioid use. They explored each participant’s experiences accessing ED care and OUD treatment, and their perspectives specifically about buprenorphine. After exploring experiences and perspectives, participants were told that EDs in their state were now required to offer buprenorphine, and that the interviewer sought both their thoughts on this and their advice to clinicians regarding caring for patients with OUD in the ED. In order to avoid leading questions about SDM, no questions directly defined or asked about perspectives on SDM for this clinical decision: the goal was to assess perspectives about MOUD that could inform SDM. The semi-structured interview guide was iteratively revised during interviews, and after initial piloting, questions were added asking for perspectives on methadone in addition to buprenorphine, based on participant’s responses and suggestions. (See Supplemental Materials C) The study was designed to comply with COREQ standards for qualitative research.28 The Baystate Medical Center Institutional Review Board determined the study exempt.

Study Setting and Population

We sought to explore the perspectives of patients with OUD – irrespective of their treatment experience with MOUD. Therefore, participants with a history of OUD were recruited from several settings. First, patients presenting to the Baystate Medical Center ED with an opioid-related complication (overdose, withdrawal), history of OUD, or history of MOUD use were identified from the tracking board and after discussion with clinical providers. Baystate Medical Center is a tertiary care academic center in western Massachusetts that sees >115,00 patient-visits per year. Second, fliers were placed around the ED with QR codes, encouraging anyone with a history of OUD to volunteer for the study via a confidential online registry. Third, fliers were shared with MOUD clinic directors around the region and state (including methadone and buprenorphine clinics) to encourage patient participation. Inclusion criteria were age over 17, ability to speak conversational English, and a history of OUD defined by ongoing or previous chronic misuse of prescription drugs, use of heroin or fentanyl, or participation in treatment programs. Goals for participant heterogeneity included 2–3 participants from each of the following groups: recent illicit opioid use (<7 days), recent buprenorphine use, recent methadone use, experience with abstinence without MOUD, experience with abstinence from non-injection opioids, experience with abstinence from injection opioids, and experience with overdose requiring ED visit. We planned to cease recruiting and interviewing when we had interviewed at least 15 participants, met goals for heterogeneity, and stopped seeing new themes in analysis (thematic saturation).29,30

Data Collection

Interviews took place in person or via video conferencing software or phone. Participants were given an explanation of the study and verbal consent was obtained. One to three members of the research team were present for each interview, based on availability and training. Interviews were led by team members with experience with qualitative methods. Interviewers conducted participant checking – ensuring they understood participant’s points and perspectives – in real time, as there was a plan in place to destroy participant’s contact information after interviews in order to protect their privacy. Participants were reimbursed for their time via a $20 gift card. Interviews were deidentified and transcribed verbatim.

Primary Data Analysis

Dedoose qualitative data management software was used for coding and analysis of transcripts. (Dedoose Version 8.1, SocioCultural Research Consultants, LLC, Los Angeles, CA.) The initial codebook was created by the three interviewers with input from two other clinician-researchers with extensive experience with qualitative methods and the treatment of patients with OUD. Each transcript was initially coded independently by 2 research team members as the codebook was developed. Coding proceeded with both a deductive and inductive approach.31,32 Via the deductive approach, codes expected based on our framework (Figure 1) were identified, named, and organized. Via the inductive approach, emergent themes were identified and then discussed. Discussions during coding revealed that many emergent codes relating to the context of self-defined recovery could be appropriately organized using a socio-ecological model of addiction, and that this context was relevant to inform shared decision-making in the ED.33 Discussions and refinement of the codebook continued as interviews continued. Interviews were conducted until both theoretical saturation and goals for participant heterogeneity were reached.30 All transcripts were re-coded by two members of the research team once the codebook was finalized, and discrepancies were decided by a third team member. The final codebook can be found in Supplemental Materials D.

Results

A total of 26 participants were interviewed, with 7 participants recruited and interviewed in-person in the ED, and 19 recruited from fliers and interviewed via video conferencing software (Figure 2). A recording device failed in one (in-ED) interview, so interviewer notes were used in lieu of a transcript. Nearly all participants had ED visits related to their opioid use, and goals for participant heterogeneity were met, due to the diverse life experiences of the participants (Supplemental Materials F). Thematic saturation was met, as few new concepts emerged from the last 5 interviews.30

Figure 2.

Participant recruitment

The majority of participants had used an unprescribed opioid within the past 2 years and had tried both methadone and buprenorphine. Many were currently using MOUD at the time of the interview. Participants’ mean age was 36 (Table 1) and they had substantial variation in self-defined recovery stories (Supplemental Materials F). To help understand decisional needs in the context of the whole patient, salient themes of participants’ recovery stories, organized via the socio-ecological model of addiction, are noted in Figure 3 (Contextual Factors Relevant to Recovery Conversation).33

Table 1.

Participant Demographics

| Characteristic | N=26 (%) |

|---|---|

| Gender (self-identified) | |

| Female | 16 (61.5) |

| Male | 10 (38.5) |

| Non-binary | 0 (0) |

| Age (mean = 35.6, median 36.5, SD 10.3) | |

| 18–30 | 7 (26.9) |

| 31–50 | 16 (61.5) |

| >50 | 3 (11.5) |

| Race (self-described) | |

| White | 21 (80.8) |

| Hispanic | 2 (7.6) |

| Black | 1 (3.8) |

| Native American | 1 (3.8) |

| Other | 1 (3.8) |

| Language Spoken at home (other than English) | |

| Spanish | 4 (15.4) |

| Insurance (only available for 21) | |

| Medicaid | 4 (19.0) |

| Commercial | 17 (81.0) |

| Highest Level of Education (only available for 25) | |

| 8th Grade or Less | 1 (4.0) |

| Some High School | 5 (20.0) |

| High School/GED | 9 (36.0) |

| Some college of 2-year degree | 8 (32.0) |

| 4-year college | 2 (8) |

| MOUD Tried | |

| Buprenorphine | 23 (88.5) |

| Methadone | 19 (73.1) |

| Both | 18 (69.2) |

| IV Drug Use | |

| Yes | 17 (65.4) |

| No | 9 (34.6) |

| Time since last unprescribed opioid (only available for 24) | |

| < 1 Week | 6 (25.0) |

| 1 Week- 6 months | 5 (20.1) |

| 6 months - 2 years | 4 (16.7) |

| > 2 years | 9 (37.5) |

Figure 3:

Contextual Factors Relevant to Recovery Conversation: Salient Barriers to and Facilitators of Recovery

1. Decisional Needs and Factors Relevant for Decision-Making

Participants were able to discuss their needs and the factors they considered when deciding whether to start MOUD. Factors generally fell into one of three categories – social, pharmacological, and emotional – and specific pros and cons are listed in Tables 2 and 3. Results as they relate to the original framework are visually represented in Figure 4.

Table 2.

Patient perspectives of pros and cons of buprenorphine, most salient themes and quotes

| Domains | Theme | Quotes | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pros | Social | Logistically easy | Suboxone is like, you can take it and forget about it…you don’t need to, like, “oh, Christ, I need to wake up and go to the methadone clinic, and I want to be the first person there or I’m going to be 40 deep and in a line.” (Participant D) I thought I would do methadone to nothing. So it was a setback in the fact that now I’m still on an MOUD. But if I have to be on one, I’d rather it be Suboxone. At least I have way more control over my life. I feel like and I feel like an actual full person now versus at the clinic. (Participant K) |

| Pharmacological | Effective | I haven’t had a craving in like, forever … I mean…it definitely did help. (Participant D) When I was sick and everything. It certainly made me feel better. So, that was a plus. (Participant E) When people are withdrawing down south and we can’t find our pills, we will buy suboxone ourselves in the streets. Like, that’s a go to, that’s the first thing we go to. If we can’t find pills, we’ll buy suboxone. (Participant Q) |

|

| Helps with urges, withdrawal, “helps you feel normal” | I tried Suboxone through my doctor…it almost took away the withdrawal symptoms, not fully… the majority of them. (Participant T) You don’t have that high…you just feel like everything’s okay. You just feel like, I always want to say normal, but I don’t know if that’s the right word, you’re just happy. Like, everything’s just good for you. Like you just feel normal. Without the high, like you don’t have to have it and you don’t crave it, it just, it does something to your receptors to where you just feel normal, like every single day. (Participant Q) |

||

| Prevents the use of other opioids (safety, prevents overdoses, can’t get high) | It’s more of like a feeling of like, I feel protected. I feel like if I went to use I… I wouldn’t die because I’m on Suboxone, you know, I mean, like, I feel like suboxone really helps me. (Participant I) | ||

| Fast Acting | Try suboxone first. It is easier on your body, like it starts working faster than methadone does. Like when you’re in withdrawal. It just stops you like, if you’ve at least been off opiates, like street drugs for at least two or three days. Like it just works faster, it gets right in your system and starts working immediately. (Participant Q) | ||

| Emotional | Psychological benefit of taking a medication every day | I would say that the benefits…like the ‘daily,’ I mean you’re still getting the daily pills. ‘Cause a lot of it is just ‘the daily,’ you know? (Participant C) | |

| Cons | Social | Can sell buprenorphine for heroin | When I went the suboxone route it was solely to sell it. Cause you can’t sell methadone. (Participant C) |

| Transportation needed | I always had a vehicle and a job to pay for my vehicle and gas and car insurance. There are so many people where they don’t have transportation to get to and from the clinic (Participant T) | ||

| Pharmacological | Buprenorphine made me feel worse (precipitated withdrawal, etc) | I got really really sick… Like shit, I felt terrible… I wasn’t in withdrawal yet. (Participant V) I tried Suboxone a long, long time ago at one time, I wasn’t even addicted. And it made me still very, very sick. Which was strange, because I didn’t have any opiates in my system. And it still made me very sick. (Participant Z) |

|

| Abusable | I know plenty of people that abuse them, you know. I mean, they abuse them to get high. Like Suboxone can definitely get you high if you abuse it. But if you take it the way you’re supposed to, and the way that my doctors telling me to, everything’s worked out fine. I haven’t got any high feelings from it. (Participant I) | ||

| Need to wait to start, need to be in severe withdrawal | The whole switch to the Suboxone was super difficult because it takes three or four days with the induction before you start feeling okay. And also, it’s not like methadone, where you can use as you’re going up…props to anyone that can get through that three or four days feeling absolutely like dogshit and not get high. But it never worked for me. (Participant B) | ||

| May not work well (if high opioid use, long acting opioids, fentanyl) | I just don’t think it helps with fentanyl. (Participant X) Suboxone doesn’t work great…if you’re on fentanyl. Fentanyl takes a very long time get out your system. So when you take it, you go into precipitated withdrawals, even if you have been sick for you know, four or five days. Fentanyl can be into your system up until a month. (Participant Z) |

||

| Can’t easily switch to buprenorphine from methadone | I took my Suboxone after I took my methadone, one day after. And it put me in complete withdrawals. I was puking like exorcist-type puke. (Participant Q) | ||

| Side effects, taste | I hate it…I don’t like the taste. (Participant V) | ||

| Dependence | This Suboxone…this animal is 10 times worse than the dope just because, you know, you’re not gonna be able to kick the suboxone, that’s for damn sure. (Participant H) | ||

| Emotional | Stigma of dependence (“trading one addiction for another”) | I guess I considered it (buprenorphine) still using…I wanted to just not be on anything. It was definitely because I felt judged because when you tell people you’re on Suboxone, or methadone, they’re automatically like… people think being on that isn’t being clean. (Participant T) It’s not really like you’re clean, because you’re still on a drug. (Participant Z) |

|

| Fear of precipitated withdrawal | You can’t give Suboxone at the emergency room for someone who’s only started withdrawal, they’re just going to get sicker. And they’re there because they can’t control it anymore. Because the withdrawals are so bad. They know, I know, most of them know, that if they take that suboxone that night, they’re just going to get way sicker. (Participant A) | ||

Table 3.

Patient perspectives of pros and cons of methadone, most salient themes and quotes

| Domains | Theme | Quotes | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pros | Social | Structure of methadone program is helpful (accountability due to need to show up daily) | That’s kind of why I like methadone better too, because I had to go there every day and show some, like, accountability. (Participant B) Anybody that needs a more strict, regimented recovery, I would say do methadone. (Participant D) |

| Pharmacological | Effective | I’ve had more of a success with methadone…I’ve been sober for a year. (Participant Q) | |

| Can continue to use opioids (and therefore quit gradually) | When I started dosing, I was at 30. So I would use a bundle, then I went up to 40. I would use like, you know, maybe still a bundle, eight bags, and then 50 it was like, eight or six, you know, I mean? So by the time I was at 100, it was like the bags weren’t even doing anything, I might as well just dose and save on money for food, cigarettes. (Participant B) I didn’t just stop using six months ago, because…you don’t get to the right amount for a while…I kept petitioning for a split dose. I didn’t get a split dose until January… the first day I got the split dose I never used again…that’s what I needed. (Interviewer: So prior to getting the split dose, you were still using a little bit on top?) Yes. (Participant Z) I was still using heavily at the start. As the dose went up, I couldn’t, like I stopped getting sick, like withdrawal. And so like, one day I didn’t use and then I felt okay. And then so it kind of then it became like a waste of money to use because my dose was high and I couldn’t feel anything anyways, and I wasn’t feeling sick anymore. So like one day of not using turned into like two days. And then two days turned into three and three turns into four. And then it just kind of proceeded like that. (Participant K) |

||

| Can start immediately, get immediate relief from withdrawal | Methadone is good for when you first check in and you’re coming from feeling like death, and you want to feel a little less like death… The thing about the Suboxone is they (detox) want you to wait like three days to take it. (Participant D) | ||

| Titratable | That’s why I really do believe it’s an awesome medication. If you are on the right dose, the correct dose of methadone. (Participant P) | ||

| Emotional | Psychological benefit of taking a medication every day | I know for me like I needed something. And it might be like the addict in me that was like, “Oh, I’m still taking an opiate every day.” But I would recommend methadone to anyone. (Participant B) | |

| Connection to methadone clinic (staff, counselors) | I’ve been lucky up pretty much with counselors at the clinics. I have a good counselor right now …We’re fairly close in age and sobriety time and past experiences and stuff… he understands where I’m coming from, but it does help…Yeah, so I think counseling helps a lot. (Participant F) | ||

| Cons | Social | Logistically difficult | I think it was having to go to the clinic every day, which, to me was a pain in the ass… I loved the groups…. the counselors and the workers, they really care…. but I just I needed to get back to life…it really it is liquid handcuffs, (they) really hold you down. (Participant A) I had to rearrange my entire life, so I could get there every morning. … it was just super inconvenient… I’ve been clean for eight years, you still are treating me like a child… there’s no there’s no working with someone … they call it liquid handcuffs for a reason. It’s like they’re always going to remind you of what you are. (Participant K) Down south is very different. And down there, you have to pay for methadone. And you have to have your own transportation there. (Participant Q) It’s very restrictive. You can’t go on vacation, you can’t do all sorts of things. Like it’s really restrictive. (Participant Z) |

| Transportation needed | (My) boyfriend at that time, was just like, I don’t want to drive you every day. (Participant X) | ||

| Cost/insurance | I would get on methadone for a couple of days and then I couldn’t afford it anymore. It was very expensive. (Participant Q) | ||

| Potential triggers at clinics (“others in line”) | I’ve heard way too many stories about people meeting people at methadone clinics and going on benders… you’re eventually gonna say, ‘fuck it,’ and ask them what they’re doing after the clinic. You know… It’s just like another gateway to fuck up. (Participant D) | ||

| Pharmacological | Can make you high | I can’t say I’m completely against it, but there’s the majority of people I know, they just use it to get high. (Participant L) | |

| Can continue to use | I wanted to get on methadone because I didn’t want to wake up dope sick anymore (not because I wanted to stop using). You know what I mean… when I was on methadone, I was still getting high. (Participant C) | ||

| Dependence & difficult to taper | I went to jail once on it and I’d rather detox off heroin any day over methadone cold turkey. (Participant F) | ||

| Can still have withdrawal | Unless they decide to stop using and then they have their dose put up. That’s the only way that they are able to stop using you know, because you’re still in withdrawal. Even if you’re getting that methadone, you’re still in withdrawal because you don’t have the heroin. (Participant P) | ||

| Needs titration (dose starts low but could also be too high) (move sedation here) | Methadone is one of the things - you have to give it time to work… they don’t generally give you anything higher than 30–35 milligrams to start. they actually go up gradually… and you still feel like crap (Participant P) you will have to use for at least the first month or so until you get up to a dose. You know, it’s not something that you could just take right away. And your, I mean, your withdrawals will stop, like, you’re not going to be on the right dose, like they’ll stop for a few hours, and then they’ll come back. Everyone’s dose is different. So you just have to be patient with that. (Participant Z) |

||

| Emotional | Stigma of dependence | I didn’t want my body to be chemically dependent on anything. I wanted my body to have nothing. No foreign substances in there. (Participant T) Some doctors and nurses still treat me like, “the methadone addict, the ex-junkie, she’s gonna use.” (Participant F) |

|

Figure 4.

Framework for incorporating participants’ needs and perspectives into Shared Decision-Making

ED = Emergency Department; OUD = Opioid Use Disorder: MOUD = Medications for Opioid Use Disorder

A. Experiences and attitudes regarding buprenorphine

All but two participants reported they had tried buprenorphine and liked it, felt it was effective in treating OUD, or felt it was at least “worth trying,” for someone with OUD. Participants listed numerous advantages to buprenorphine, most notably its logistical ease compared to methadone (e.g. at-home dosing) and that it was effective in helping with withdrawal, feeling normal, and avoiding street drugs (Table 2).

It works…(it) makes you feel better…’cause you’re off the drugs. (Participant V)

I just thought Suboxone (buprenorphine-naloxone) was easier for me because they will give you a prescription for it. And you can just take it home with you. And it’s just easier than having to go every single day somewhere. It’s just easier treatment. (Participant Q)

Many disadvantages were also noted: one could sell their buprenorphine and buy illicit opioids, one needed to be in severe withdrawal to start it, it could make one “feel worse” (trigger precipitated withdrawal) it was abusable, and it might not work for people who used a lot of opioids or who used fentanyl. Some concepts were considered both advantages and disadvantages. For example, the fact that you could not continue to use illicit opioids while on buprenorphine was considered both a pro and a con, often by the same people.

Regarding the initiation of buprenorphine in the ED, nearly all patients were unaware that buprenorphine was available from the ED, and felt ED-initiated buprenorphine was appropriate and beneficial.

I think that’s great. I think that is so good. When they send us out from the ER, they’re just like, “Oh, well, you’re better, you can just go.” Like, we’re just going to go find more drugs. I feel like they should help…because it’s an emergency room and that’s an emergency. (Participant Q)

I would think it would be a good way to get somebody on the track to recovery. (Participant E)

Participants consistently noted three reasons ED-initiated buprenorphine was important. First, initiating buprenorphine might save someone’s life. Second, even if a patient declined, if a clinician “leaves the door open,” the patient would know it was available and might return later. Third, the ED may be easier for people to access than a clinic or primary care office due to stigma and logistical barriers.

You just got to remember that this medication could be life-saving to that person and get their life back on track… It’s better than a needle. (Participant S)

All you can do is really leave the door open. You can’t force anybody to do anything. All you can really do is just let them know that the help is there and hope that they reach out. (Participant D)

Maybe once more people know, then that will encourage people to not stay home and go through withdrawal until they end up going and buying heroin … because they’re too ashamed to go in and talk to their doctor or they can’t get an appointment fast enough or whatever the case is. Like, maybe this will encourage people to go and get on it. (Participant P)

B. Knowledge/understanding about the mechanisms of action for buprenorphine

Most participants who had tried buprenorphine could explain that it had “blocking” properties and that these properties that would cause one to “feel worse” (precipitated withdrawal) if they were not yet in opioid withdrawal and could keep people from overdosing. However, several participants erroneously believed these effects were due to the naloxone component of the Suboxone (rather than from the buprenorphine itself). A few noted that they did not think that buprenorphine worked if someone was taking high doses of opioids or using fentanyl, as those were “in their system” for too long. One participant noted that although she felt buprenorphine would be great for someone in severe withdrawal, she didn’t know anyone who could “last long enough” to benefit from buprenorphine, as they would all end up using illicit opioids because of the severity of the withdrawal.

C. Experiences and attitudes about alternatives to buprenorphine

Notably, when discussing the advantages and disadvantages of buprenorphine, many participants felt that any conversation about MOUD should also include a discussion of the risks and benefits of methadone as well (Table 3).

I don’t think there’s any downsides to it (offering buprenorphine). I just think that they should offer that and methadone. But if they can only offer buprenorphine right now…I wouldn’t say they shouldn’t do it. (Participant B)

As with buprenorphine, some factors were considered both an advantage and a disadvantage. First, many participants felt methadone was beneficial in that people could keep using illicit opioids as they titrated to a therapeutic dose of methadone, allowing them to “ease into” recovery or abstinence, while others felt that this ability to keep using decreased a person’s likelihood of eventual recovery.

For suboxone, you have to be able to be clean for two days and none of these people are going to be able to do that. I have all the hope and faith in everybody, but it’s just not realistic. So I always recommend going to methadone first, because you can still use while you’re on methadone. And for a lot of us, that’s really important. There’s no wake-up call, “light switch” moment, it’s sort of a fluid thing. And even if they’re not ready to stop, methadone might keep them alive till they get to that point. Or it might - like me - make them get to that point. (Participant K)

Methadone is literally one of the worst…ideas in the entire world. Because you can still use with no repercussions on methadone. (Participant L)

Second, the very structured nature of methadone programs was considered helpful by many, but also logistically challenging. These two factors were also the two most frequently noted differences between methadone and suboxone.

So I think people choose Suboxone over methadone because they don’t want to go to the clinic every single day of their life. That’s even more controlling. You have to get up every day. Just like when you’re getting high, they (clinic) have that control over you…But then I also know people that choose methadone because they need the structure…I think it’s all preference. (Participant S)

A few people brought up alternatives to buprenorphine and methadone including depot naltrexone (Vivitrol) and quitting “cold turkey.” Neither of these options received many endorsements, the first due to logistical challenges (a required long period of abstinence) and the second due to lack of efficacy.

Whoever said they’re going to quit cold turkey is the turkey. Because they’re not. (Participant G)

2. Informing Decisional Support

A. Support of Shared Decision-Making

Participants were not asked specifically about the role of shared decision-making in ED care for patients with OUD, but many brought up tenets of SDM independently. They noted that what was a disadvantage for one person was an advantage for another, stressing the importance of tailoring treatment for OUD to an individual’s needs, values, and circumstances. Many participants also noted that at different points in their recovery, they had different needs, and what worked at one point in time might not have been appropriate for them at another time.

Just give them a choice… I’m an advocate for both (buprenorphine and methadone) now… There’s so many different pros and cons. And I just had to figure out which one was more suitable for me. It just all depends on your situation and you and where you are at in life, which one’s better for you. (Participant Q)

B. Clinician’s communication skills (knowledge and empathy)

The majority of participants noted that it was important for clinicians to avoid appearing judgmental. Most also noted that while they hoped that clinicians would get additional training to be able to explain the pros and cons of MOUD, they recognized that the clinicians were not experts in MOUD, and they felt that clinicians should be humble and honest about what they don’t know. Several noted that a “peer recovery” coach in the ED might be more beneficial than a physician, as they valued the advice and support of someone with lived experience.

…heroin addicts are people too… there’s more to that person, there’s more to their story…if you made a big mistake in your life, would you only want to be known by that one mistake? … I think people that haven’t experienced addiction, or didn’t have a close loved one that they watched, need to realize that we are people. There is more to us, we all have hopes and dreams, and all. And that little kindness, and help and understanding makes a big difference between somebody treating you like crap, and someone making you feel like a human being. (Participant F)

With regard to how they were treated in their own past ED encounters, participants reported varied experiences. Some noted that the stigma is improving, but is still strong and makes getting care difficult.

I definitely think the stigma is getting better, but it could be a lot, lot, lot better. I think people just need to get educated and not judge and they need to realize that …that’s a human being. That’s someone’s son or daughter, or mother or grandmother. (Participant S)

C. The “readiness” paradox

Participants emphasized personal “readiness” as an important factor. The majority of participants noted that one had to be “ready” to stop using illicit opioids. Many described this as an internal state, caused by “the right motivation,” and blamed their own past failures on not being ready or not “doing it for the right reasons.”

If you’re not ready to get clean, you’re not going to get clean. There’s no miracle drug out there… you got to be willing to put as much effort into sobriety as you did to get that morning fix every day. (Participant F)

However, participants gave many examples about how different factors pushed them towards a state of readiness, including caring healthcare providers, shared recovery stories, their children, or starting methadone and realizing a medication could help them “get their lives back.” (Figure 3) Many gave stories contradicting their own beliefs that “readiness” was an internal state that others could not influence.

Sometimes all it takes is like, the smallest, smallest little… like thought… they might want to get clean. (Participant B)

Get to know them a little bit and if they have kids bring up their kids, or their family, their friends. Any hope or aspirations they have remind them they can’t do any of that. They can’t be the person they can be until they take care of themselves. Sometimes… well, all the time, you need to hear that. (Participant S)

The second time (in the ED)…the nurse there really convinced me that I needed to go get help and after I left there that’s what I did…What she said? She was just telling me her own story and how her husband was an addict and how she saw him go through this all these years…I basically asked like, like what made him stop? And she was like, “himself. He had to do it for himself. He couldn’t do it because me or my child was telling him that he needed to stop. He had to figure it out on its own.”… That’s my whole thing. I had to figure out on my own and I did. (Participant I)

Additionally, most participants felt strongly that MOUD should be offered regardless of a person’s state of readiness.

If everybody wants to stop the opiate epidemic, then they should help. People need help… we just can’t stop. So we just need help. And I just think if everyone wants to stop the opioid epidemic, I think that that’s just the best thing they could do is to offer this. (Participant Q)

D. ED care to support patients with OUD

Outside of MOUD, participants felt that coordination with outpatient care (a “warm handoff”) would be helpful. They felt that improved coordination with psychiatric care, naloxone (to-go and training), peer recovery coaches, comfort medications (i.e. dicyclomine, acetaminophen, clonidine), lists of outpatient resources, and other methods of harm reduction would be useful.

3. Additional relevant themes identified by researchers

Research team members, in discussions about interviews, noticed some themes that were not expressed specifically by participants, but nonetheless might inform ED care around MOUD, specifically regarding the context of recovery (Contextual Factors Relevant to the Recovery Conversation, Figure 4).

A. Recovery means different things to different people

First, “recovery” clearly meant different things to different people: some defined recovery for themselves as abstinence from illicit opioids and MOUD, others felt being on MOUD without use of illicit opioids was recovery, and still others felt that occasional, controlled use of illicit opioids, while maintaining a job and using MOUD, was a stable recovery.

B. Relapse is part of recovery

Almost every recovery story was non-linear – relapse was part of every single story. While some people had not used in years, getting to the point of non-use always took multiple attempts and different methods. However, the majority of interviewees experienced periods of non-use - some for many years - where they were able to “get their lives back” and see how life could look when their addiction wasn’t controlling them. These periods, regardless of length, appeared to contribute to participants’ motivation and self-efficacy.

C. Psychiatric care should be integrated into OUD care

Lastly, participants gave numerous examples regarding their need for concomitant psychiatric care and therapy. Many noted successful recovery stories that included inpatient psychiatric care and MOUD, outpatient therapy, and coping skills learned from therapists. Many noted, in discussing relapses, that they “weren’t dealing with” their depression or PTSD, and that’s why they started using again. Many noted traumatic experiences as both part of how they ended up using opioids in the first place and a major barrier to recovery.

Yeah, the longer you use, the more trauma you come to, the more trauma, the harder it is to get over it. You just use to get rid of the trauma, more trauma happens, so you use more to forget about that trauma. You know, it’s an endless cycle. (Participant F)

Limitations

As with all qualitative exploration, these results should be seen as hypothesis-generating. Although the participants were sampled from a geographic region heavily affected by OUD, and several had moved around within the US, participants from other regions may have had different responses. In particular, the state in which interviews were conducted has near-universal health insurance coverage, and this affected participants’ ability to access MOUD. For this reason, and because two-thirds were recruited from MOUD clinics, this cohort may have had more experience with MOUD than ED patients from other regions, and possibly more positive attitudes. This may mean that in other locales, patients have more decisional needs regarding knowledge than these participants expressed.

Additionally, there is some qualitative evidence demonstrating that participant interviews regarding MOUD can be heavily influenced by the dominant discourse of 12 step abstinence-based messaging.34 This seems to be particularly evident when participants perceive interviewers as non-OUD patients or patients in long-term abstinence-based recovery, leading participants to “tell [them] what [they] want to hear.”34 This could have shaped some of the participants’ statements, such as the criticisms of methadone as not conducive to recovery because patients can still use illicit opioids while in treatment.

This study was focused on only one aspect of implementation: the interpersonal interaction within the ED. While a number of implementation barriers and facilitators were noted by participants, it was not the goal of this study to explore all implementation barriers.

Discussion

Successful ED-based MOUD initiation is a multi-step process that involves actions at the level of the individual, the institution, and the community before, during, and after the patient encounter.15 While prior studies have focused on addressing hospital-based systems and clinician barriers, ours is the first to explore the decisional needs for ED patients with OUD from the perspectives of people with lived experience. Our findings, though exploratory, have implications for ED care and for clinicians motivated to stem that tide of opioid-related morbidity and mortality (Table 4).

Table 4.

Findings and clinical implications as synthesized by the research team

| Finding | Implications for Clinicians, ED structure, and Shared Decision-Making Conversations |

|---|---|

| Participants noted that treatment should be tailored to an individual’s needs and current circumstances. | Clinicians may need training to be able to discuss the options for treatment that are available within their ED and community (both the pharmacology and the logistics). |

| Participants felt methadone should be offered as well as buprenorphine. | EDs should consider ways to provide methadone or create care linkages with methadone providers; cliniciands need to understand the pros and cons of methadone as well as buprenorphine. |

| Many characteristics of the different types of MOUD are not consistently pros or cons. Example: For some people, knowing they can still use heroin when on methadone will help them consider starting it, and this may be a path to recovery. Others feel this is a negative to methadone. |

Clinicians will need to be able to discuss these factors without assigning values to them, instead of the traditional “pros” and “cons” discussion. |

| The “readiness” paradox: although there was a lot of discussion of personal “readiness” as an internal state, participants noted external factors could increase readiness. | Recovery options should be offered regardless of stated “readiness,” both to encourage readiness and so that patients know that treatment is available when they are ready. Clinicians could encourage “readiness” by asking patients questions about motivators and previous success. |

| Many participants reported feeling worse after taking buprenorphine (i.e. experiencing precipitated withdrawal) | Understanding and explaining how to take buprenorphine will be necessary and clinicians will need to know how to treat precipitated withdrawal. Those who have experienced precipitated withdrawal are likely to be hesitant to try buprenorphine again. Clinicians will need to foster a trusting relationship so that patients |

| Some participants reported they weren’t sure buprenorphine would work for those using fentanyl or large amounts of opioids. | A discussion of types of opioids used may be necessary, as emerging evidence suggests patients using fentanyl may respond differently to buprenorphine.40–41 Alternative dosing strategies (both quantity and timing) may be necessary for those using fentanyl.42 |

| Relapse is part of recovery. | Every patient interaction is an opportunity to help someone restart their path to recovery. Discussing previous periods of success may foster self-efficacy. |

Our participants were not asked about shared decision-making, but their perspectives none-the-less support the use of SDM in this scenario. Participants generally agreed on the social, pharmacological, and emotional factors that would be important to patients – efficacy, ease of use/logistics, non-pharmacological structure of programs, and potential for misuse and concurrent illicit opioid use. The differing importance of these factors – as well as the substantial overlap between “pros” and “cons” – also supports the use of shared decision-making, and speaks to the need to have these conversations in a safe, non-judgmental way. Participants made it clear that the decision to start the various forms of MOUD is individual and “preference-sensitive,” a situation where “what matters to you?” is one of the most important questions a clinician can ask. As starting MOUD in the ED is a new skill for many ED clinicians, the framework presented, the participants’ insight, and the research team’s proposed implications (Table 4) can help clinicians understand how to have effective shared decision-making conversations.

Although participants felt that many patients won’t be “ready” to start MOUD, it was clear that just having the conversation might have benefits – either moving the patient towards readiness or just letting them know that MOUD in the ED is an option if they can’t access it elsewhere. Even a brief interaction that does not lead to a prescription may have positive downstream effects.

While these findings support SDM in the ED, they suggest clinicians may need more training around the provision of buprenorphine and methadone and the conversation may have to be tailored to what the ED and community realistically can offer. One tactic to address both these issues would be to have a peer recovery coach or navigator embedded in the ED to have these conversations. This “task shifting” has been found to be effective in other contexts, but has not been studied for SDM or treatment of OUD.35

Some of our findings triangulated the known literature and recently reported clinicians’ perspectives. Most participants did not know buprenorphine could be prescribed from the ED – likely because the vast majority of patients are not offered it.10,36 Participants felt clinicians needed more training and EDs needed to have mechanisms in place to assure smooth follow-up – barriers clinicians have endorsed in previous studies.14,15,17–19 Clinicians have noted concerns about diversion, and patients noted this as well.15 It is worth noting, however, that many participants reported they took non-prescribed buprenorphine for its intended usage, to avoid withdrawal and prevent overdose. This is consistent with the current literature: diverted buprenorphine is usually taken for its given therapeutic purpose and does decrease the likelihood of an overdose in those who take it.37,38Additionally, known structural barriers to MOUD access, such as insurance/cost and transportation, were noted.39

Participants noted an emerging issue with buprenorphine as the opioid supply is increasingly comprised of fentanyl rather than heroin – that people using fentanyl may have a higher risk of precipitated withdrawal despite a period of abstinence that was previously considered safe.40–43 This is emerging in the literature as an important issue, as it makes both people with OUD and clinicians hesitant to initiate buprenorphine.40–43 Fortunately, research addressing the treatment of precipitated withdrawal is a rapidly evolving; “micro” and “macro” dosing of buprenorphine may be effective, and IV ketamine has also been used with good effect.44–47 However, the actual risk of precipitated withdrawal for an individual patient is based on history of drug use (which drugs and when), and may be difficult for a clinician to predict. This has implications for SDM in this context: clinicians will need to effectively treat precipitated withdrawal and be able to reassure patients that they will be adequately treated should they have severe withdrawal. Failure to do so will undermine trust and future recovery efforts.

Lastly, several studies have noted that clinicians would benefit from feedback on patients’ experiences – this study provides some feedback: clinicians should know that MOUD is effective for many people and is enthusiastically welcomed by our participants, who spoke to us as representatives of our patients (Supplemental Materials F).14,15

While clinician training, embedded clinical pathways, coordinated and concurrent psychiatric care, and improved linkage to outpatient resources will improve implementation, our participants give us insights into how to have meaningful interactions. These results support the use of shared decision-making frameworks in the development of patient-centered interventions to increase the use of MOUD in the ED. While centering on patients will not address all barriers to the prescription of MOUD, helping clinicians provide patient-centered care may address stigma and improve communication, contributing to improved outcomes for this high-risk patient population. These results will help future efforts to create, refine, and assess tools that facilitate effective conversations around MOUD in the ED. Additionally, research will need to evaluate the long-term consequences of improved communication.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments:

The research team would like to thank the participants for their time and honesty.

No authors report any conflicts of interest. EMS, WS, and LW have received grants for investigator-initiated research, listed above in Funding.

Funding Sources/Disclosures:

Dr. Schoenfeld is supported by a grant from AHRQ 1K08HS025701-01A1; Dr. Soares is supported by a grant from NIDA: 1K08DA045933-01, Dr. Westafer is supported by a K23 from NHLBI

Footnotes

Prior Presentations: None

References

- 1.https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/pressroom/nchs_press_releases/2021/20211117.htm (Accessed December 2, 2021)

- 2.Sordo L, Barrio G, Bravo MJ, Indave BI, Degenhardt L, Wiessing L et al. Mortality risk during and after opioid substitution treatment: systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies BMJ 2017; 357 :j1550 doi: 10.1136/bmj.j1550 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.D’Onofrio G, O’Connor PG, Pantalon MV, et al. Emergency department–initiated buprenorphine/naloxone treatment for opioid dependence: a randomized clinical trial. Jama. 2015;313(16):1636–1644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kinsky S, Houck PR, Mayes K, Loveland D, Daley D, Schuster JM. A comparison of adherence, outcomes, and costs among opioid use disorder Medicaid patients treated with buprenorphine and methadone: a view from the payer perspective. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2019;104:15–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Connery HS. Medication-assisted treatment of opioid use disorder: review of the evidence and future directions. Harv Rev Psychiatry. 2015;23(2):63–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kelly T, Hoppe JA, Zuckerman M, Khoshnoud A, Sholl B, Heard K. A novel social work approach to emergency department buprenorphine induction and warm hand-off to community providers. Am J Emerg Med. 2020;38(6):1286–1290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Edwards FJ, Wicelinski R, Gallagher N, McKinzie A, White R, Domingos A. Treating opioid withdrawal with buprenorphine in a community hospital emergency department: an outreach program. Ann Emerg Med. 2020;75(1):49–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Houry D, Adams J. Emergency physicians and opioid overdoses: a call to aid. Ann Emerg Med. 2019;74(3):436–438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chua K-P et al. Naloxone and Buprenorphine Prescribing Following US Emergency Department Visits for Suspected Opioid Overdose: August 2019 to April 2021. Ann Emerg Med (2021) doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2021.10.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kilaru AS, Xiong A, Lowenstein M, et al. Incidence of Treatment for Opioid Use Disorder Following Nonfatal Overdose in Commercially Insured Patients. JAMA Network Open. 2020;3(5):e205852–13. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.5852 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schoenfeld EM, Westafer LM, Soares WE. Missed Opportunities to Save Lives-Treatments for Opioid Use Disorder After Overdose. JAMA Network Open. 2020;3(5):e206369. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.6369 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Collins AB, Beaudoin FL, Samuels EA, Wightman R, Baird J. Facilitators and barriers to post-overdose service delivery in Rhode Island emergency departments: A qualitative evaluation. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2021;130:108411. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2021.108411 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sokol R, Tammaro E, Kim JY, Stopka TJ. Linking MATTERS: Barriers and Facilitators to Implementing Emergency Department-Initiated Buprenorphine-Naloxone in Patients with Opioid Use Disorder and Linkage to Long-Term Care. Subst Use Misuse. 2021;56(7):1045–1053. doi: 10.1080/10826084.2021.1906280 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hawk KF, D’Onofrio G, Chawarski MC, et al. Barriers and Facilitators to Clinician Readiness to Provide Emergency Department-Initiated Buprenorphine. JAMA Network Open. 2020;3(5):e204561. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.4561 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schoenfeld EM, Soares WE, Schaeffer EM, Gitlin J, Burke K, Westafer LM. “This is part of emergency medicine now”: A qualitative assessment of emergency clinicians’ facilitators of and barriers to initiating buprenorphine. Acad Emerg Med. Published online 2021. doi: 10.1111/acem.14369 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fox L, Nelson LS. Emergency Department Initiation of Buprenorphine for Opioid Use Disorder: Current Status, and Future Potential. CNS Drugs. 2019;33(12):1147–1154. doi: 10.1007/s40263-019-00667-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lowenstein M, Kilaru A, Perrone J, Hemmons J, Abdel-Rahman D, Meisel ZF, Delgado MK. Barriers and facilitators for emergency department initiation of buprenorphine: A physician survey. The American Journal of Emergency Medicine. 2019;37(9):1787–1790. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2019.02.025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dong KA, Lavergne KJ, Salvalaggio G, et al. Emergency physician perspectives on initiating buprenorphine/naloxone in the emergency department: A qualitative study. J Am Coll Emerg Physicians Open. 2021;2(2):e12409. doi: 10.1002/emp2.12409 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Im D, Chary A, Condella A, et al. Emergency Department Clinicians’ Attitudes Toward Opioid Use Disorder and Emergency Department-initiated Buprenorphine Treatment: A Mixed-Methods Study. Western Journal of Emergency Medicine. 2020;21(2):261–271. doi: 10.5811/westjem.2019.11.44382 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Probst MA, Kanzaria HK, Schoenfeld EM, et al. Shared Decisionmaking in the Emergency Department: A Guiding Framework for Clinicians. Ann Emerg Med. 2017;70(5):688–695. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2017.03.063 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schoenfeld EM, Mader S, Houghton C, Wenger R, Probst MA, Schoenfeld DA, Lindenauer PK, Mazor KM. The Effect of Shared Decisionmaking on Patients’ Likelihood of Filing a Complaint or Lawsuit: A Simulation Study. Annals of Emergency Medicine. Published online 2019. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2018.11.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hess EP, Knoedler MA, Shah ND, Kline JA, Breslin M, Branda ME, Pencille LJ, Asplin BR, Nestler DM, Sadosty AT, Stiell IG, Ting HH, Montori VM. The Chest Pain Choice Decision Aid. Circulation Cardiovascular quality and outcomes. 2012;5(3):251–259. doi: 10.1161/circoutcomes.111.964791 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wilson SR, Strub P, Buist AS, Knowles SB, Lavori PW, Lapidus J, Vollmer WM. Shared Treatment Decision Making Improves Adherence and Outcomes in Poorly Controlled Asthma. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine. 2010;181(6):566–577. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200906-0907oc [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hawk K, Grau LE, Fiellin DA, Chawarski M, O’Connor PG, Cirillo N, Breen C, D’Onofrio G. A qualitative study of emergency department patients who survived an opioid overdose: Perspectives on treatment and unmet needs. Acad Emerg Med. 2021;28(5):542–552. doi: 10.1111/acem.14197 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hoefel L, O’Connor AM, Lewis KB, Boland L, Sikora L, Hu J, Stacey D. 20th Anniversary Update of the Ottawa Decision Support Framework Part 1: A Systematic Review of the Decisional Needs of People Making Health or Social Decisions. Med Decis Making. 2020;40(5):555–581. doi: 10.1177/0272989X20936209 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schoenfeld EM, Poronsky KE, Westafer LM, DiFronzo BM, Visintainer P, Scales CD, Hess EP, Lindenauer PK. Feasibility and efficacy of a decision aid for emergency department patients with suspected ureterolithiasis: protocol for an adaptive randomized controlled trial. Trials. Published online 2021:1–12. doi: 10.1186/s13063-021-05140-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schoenfeld EM, Houghton C, Patel PM, Merwin LW, Poronsky KP, Caroll AL, Santana CS, Breslin M, Scales CD, Lindenauer PK, Mazor KM, Hess EP. Shared Decision Making in Patients With Suspected Uncomplicated Ureterolithiasis: A Decision Aid Development Study. Acad Emerg Med. 2020;27(7):554–565. doi: 10.1111/acem.13917 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tong A, Sainsbury P, Craig J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. International Journal for Quality in Health Care. 2007;19(6):349–357. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/mzm042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Guest G. How Many Interviews Are Enough?: An Experiment with Data Saturation and Variability. Field Methods. 2006;18(1):59–82. doi: 10.1177/1525822x05279903 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Varpio L, Ajjawi R, Monrouxe LV, O’Brien BC, Rees CE. Shedding the cobra effect: problematising thematic emergence, triangulation, saturation and member checking. Medical Education. 2016;51(1):40–50. doi: 10.1111/medu.13124 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hsieh H-F, Shannon SE. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qualitative health research. 2005;15(9):1277–1288. doi: 10.1177/1049732305276687 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bingham AJ, Witkowsky P Deductive and inductive approaches to qualitative data analysis. Analyzing and interpreting qualitative data: After the interview (pp. 133–146). SAGE Publications. 2021 [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jalali MS, Botticelli M, Hwang RC et al. The opioid crisis: a contextual, social-ecological framework. Health Res Policy Sys 18, 87 (2020). 10.1186/s12961-020-00596-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Frank D The trouble with morality: the effects of 12-step discourse on addicts’ decision-making. J Psychoactive Drugs. 2011;43(3):245–256. doi: 10.1080/02791072.2011.605706 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Leong SL, Teoh SL, Fun WH, Lee SWH. Task shifting in primary care to tackle healthcare worker shortages: An umbrella review. Eur J Gen Pract. 2021. Dec;27(1):198–210. doi: 10.1080/13814788.2021.1954616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Holland WC, Meisel ZF, Nath B, et al. Interrupted Time Series of User-centered Clinical Decision Support Implementation for Emergency Department–initiated Buprenorphine for Opioid Use Disorder. Academic Emergency Medicine. 2020;27(8):753–763. doi: 10.1111/acem.14002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Silverstein SM, Daniulaityte R, Miller SC, Martins SS, Carlson RG. On my own terms: Motivations for self-treating opioid-use disorder with non-prescribed buprenorphine. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2020. May 1;210:107958. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2020.107958. Epub 2020 Mar 16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Carlson RG, Daniulaityte R, Silverstein SM, Nahhas RW, Martins SS. Unintentional drug overdose: Is more frequent use of non-prescribed buprenorphine associated with lower risk of overdose? Int J Drug Policy. 2020;79:102722. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2020.102722 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sharma A, Kelly SM, Mitchell SG, Gryczynski J, O’Grady KE, Schwartz RP. Update on Barriers to Pharmacotherapy for Opioid Use Disorders. Current Psychiatry Reports. Published online 2017:1–8. doi: 10.1007/s11920-017-0783-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Silverstein SM, Daniulaityte R, Martins SS, Miller SC, Carlson RG. “Everything is not right anymore”: Buprenorphine experiences in an era of illicit fentanyl. Int J Drug Policy. 2019;74:76–83. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2019.09.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Varshneya NB, Thakrar AP, Hobelmann JG, Dunn KE, Huhn AS. Evidence of Buprenorphine-precipitated Withdrawal in Persons Who Use Fentanyl. J Addict Med. 2021. Nov 23. doi: 10.1097/ADM.0000000000000922. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Shearer D, Young S, Fairbairn N, Brar R. Challenges with buprenorphine inductions in the context of the fentanyl overdose crisis: A case series. Drug Alcohol Rev. Published online 2021. doi: 10.1111/dar.13394 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sue KL, Cohen S, Tilley J, Yocheved A. A Plea From People Who Use Drugs to Clinicians: New Ways to Initiate Buprenorphine are Urgently Needed in the Fentanyl Era. J Addict Med. 2022;Publish Ahead of Print. doi: 10.1097/adm.0000000000000952 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hailozian C, Luftig J, Liang A, Outhay M, Ullal M, Anderson ES, Kalmin M, Shoptaw S, Greenwald MK, Herring AA. Synergistic Effect of Ketamine and Buprenorphine Observed in the Treatment of Buprenorphine Precipitated Opioid Withdrawal in a Patient With Fentanyl Use. J Addict Med. 2021. Nov 16. doi: 10.1097/ADM.0000000000000929. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ahmed S, Bhivandkar S, Lonergan BB, Suzuki J. Microinduction of Buprenorphine/Naloxone: A Review of the Literature. Am J Addict. 2021. Jul;30(4):305–315. doi: 10.1111/ajad.13135. Epub 2020 Dec 30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Antoine D, Huhn AS, Strain EC, Turner G, Jardot J, Hammond AS, Dunn KE. Method for Successfully Inducting Individuals Who Use Illicit Fentanyl Onto Buprenorphine/Naloxone. Am J Addict. 2021. Jan;30(1):83–87. doi: 10.1111/ajad.13069. Epub 2020 Jun 23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Quattlebaum THN, Kiyokawa M, Murata KA. A case of buprenorphine-precipitated withdrawal managed with high-dose buprenorphine. Fam Pract. 2022. Mar 24;39(2):292–294. doi: 10.1093/fampra/cmab073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.