Abstract

Purpose:

We assessed sexual orientation-related patterns in the one-year longitudinal course (i.e., onset, remittance, persistence) and severity of suicidality.

Method:

Data were obtained from a prospective, population-based cohort representing nearly 2.4 million Swedish young adults.

Results:

A higher proportion of sexual minorities remitted (14.6%) compared to heterosexuals (9.5%). However, over twice as many sexual minorities (35.1%) experienced persistent suicidality as heterosexuals (15.0%). Plurisexual (e.g., bisexual, pansexual) young adults and sexual minorities aged 17–25 were at greatest risk for persistent and severe suicidality.

Conclusion:

Findings call for the identification of sexual orientation-related predictors of chronic suicidality to inform responsive clinical interventions.

Keywords: sexual orientation, persistent suicidality, disparities, longitudinal, population-based

Background

For over two decades, population-based studies have shown that sexual minorities are substantially more likely to report suicidal thoughts, plans, and attempts (i.e., suicidality) than heterosexuals [1]. However, this research often assesses the prevalence of suicidality at a single time point (past-year or lifetime) or focuses on investigating risk factors that explain sexual orientation disparities in suicidality [2,3]. While important, there are additional ways of examining suicidality that have important implications for public health surveillance and clinical intervention – namely, examining patterns in the longitudinal course (i.e., onset, remittance, persistence) and severity (e.g., frequency, closeness to suicide attempt) of suicidality.

Only one study, to our knowledge, has examined sexual orientation-related differences in the course and severity of suicidality, documenting that sexual minorities, compared to heterosexuals, reported a longer duration and more severe presentation of suicidality [4]. However, this study used cross-sectional, non-probability datasets and selected participants based on a history of suicidality, which is limited in two ways. First, determining the precise course of suicidality requires prospective data assessing recent suicidality (rather than past-year or lifetime) in order to track suicidality over time and to limit recall bias. Second, assessing suicidality severity requires a sample not selected on the outcome, which may bias estimates away from the null and cannot provide generalizable population-based estimates. Thus, to overcome limitations of previous research, the present study sought to examine sexual orientation differences in the course and severity of suicidality using the strongest design to date. To do so, we created a new prospective, population-based cohort of sexual minorities and heterosexuals assessed during late adolescence and young adulthood, which represent developmental periods of heightened risk for suicidality [5].

Method

Data were drawn from the baseline (wave 1, October 2019) and 12-month (wave 2, October 2020) assessments of the Pathways to Longitudinally Understanding Stress (PLUS) cohort, an ongoing longitudinal, population-based study. Participants were recruited from the 2015, 2016, and 2018 Swedish National Public Health Survey (SNPHS; N=181,937). Participants aged 17–34 who reported a sexual minority identity in the SNPHS were invited to participate in PLUS with a heterosexual comparison also from the SNPHS. In total, 5,885 were contacted and 2,222 provided written informed consent and completed baseline measures. All procedures involving human subjects were approved by Stockholm Regional Ethical Review Board (# 2018/1517–31).

At wave 1, participants were classified as sexual minorities (i.e., lesbian/gay or plurisexual [bisexual, pansexual]) or heterosexuals. Past-month suicidality was assessed using the Suicidal Ideation Attributes Scale (SIDAS), a validated 5-item self-report scale (range: 0–50); higher scores reflect greater severity [6]. Strengths of the SIDAS include that it measures several features of suicidal ideation severity, including frequency, controllability, closeness to attempt, distress, and interference with daily activities; it assesses past-month suicidality (rather than past-year or lifetime), thereby limiting recall bias; and it was developed for online use [6]. We classified the 12-month course of suicidality as none (no suicidality at either wave), onset (no suicidality at wave 1; suicidality present at wave 2), remittance (suicidality present at wave 1; no suicidality at wave 2), and persistence (suicidality present at both waves). We included 1.610 participants with non-missing SIDAS data. Those dropped from analyses were, on average, slightly younger and more likely to be male and to report lower income. We found no differences in the proportion of sexual minority respondents who were dropped due to missing SIDAS data and those who were retained (χ2 = 2.96, p > 0.05).

Analyses assigned weights based on the Swedish population making the sample representative of Swedish young adults. First, we quantified the prevalence of 12-month onset, remittance, and persistence of suicidality by sexual orientation. Rao-Scott Chi-Square tests were utilized to assess differences in the proportion of sexual minorities versus heterosexuals by 12-month course of suicidality. Second, we assessed sexual orientation differences in suicidality severity stratified by 12-month onset, remittance, and persistence.

Results

At baseline, participants were, on average, 26.1 years old. Approximately half of participants were cisgender women (50.3%), 48.1% were cisgender men, and 1.6% were transgender or gender non-binary. Nearly half of participants reported full-time employment (49.7%), nearly one-quarter reported being unemployed full-time students (23.0%), and the remainder reported part-time employment (20.2%) or being unemployed (7.2%). Most participants were born in Sweden (91.0%). Regarding sexual orientation, weighted prevalence estimates showed that 80.9% of participants were heterosexual, 13.5% were plurisexual, and 5.6% were gay/lesbian.

The prevalence, course, and severity of suicidality differs by sexual orientation. Fewer than half of sexual minorities experienced no suicidality at either wave (43.4%), compared to more than two-thirds of heterosexuals (68.4%; p<0.001). There were no sexual orientation differences in suicidality onset, with 7.0% of sexual minorities and 7.1% of heterosexuals experiencing onset. While a higher proportion of sexual minorities remitted (14.6%) compared to heterosexuals (9.5%; p<0.05), over twice as many sexual minorities (35.1%) experienced persistent suicidality as heterosexuals (15.0%; p<0.001).

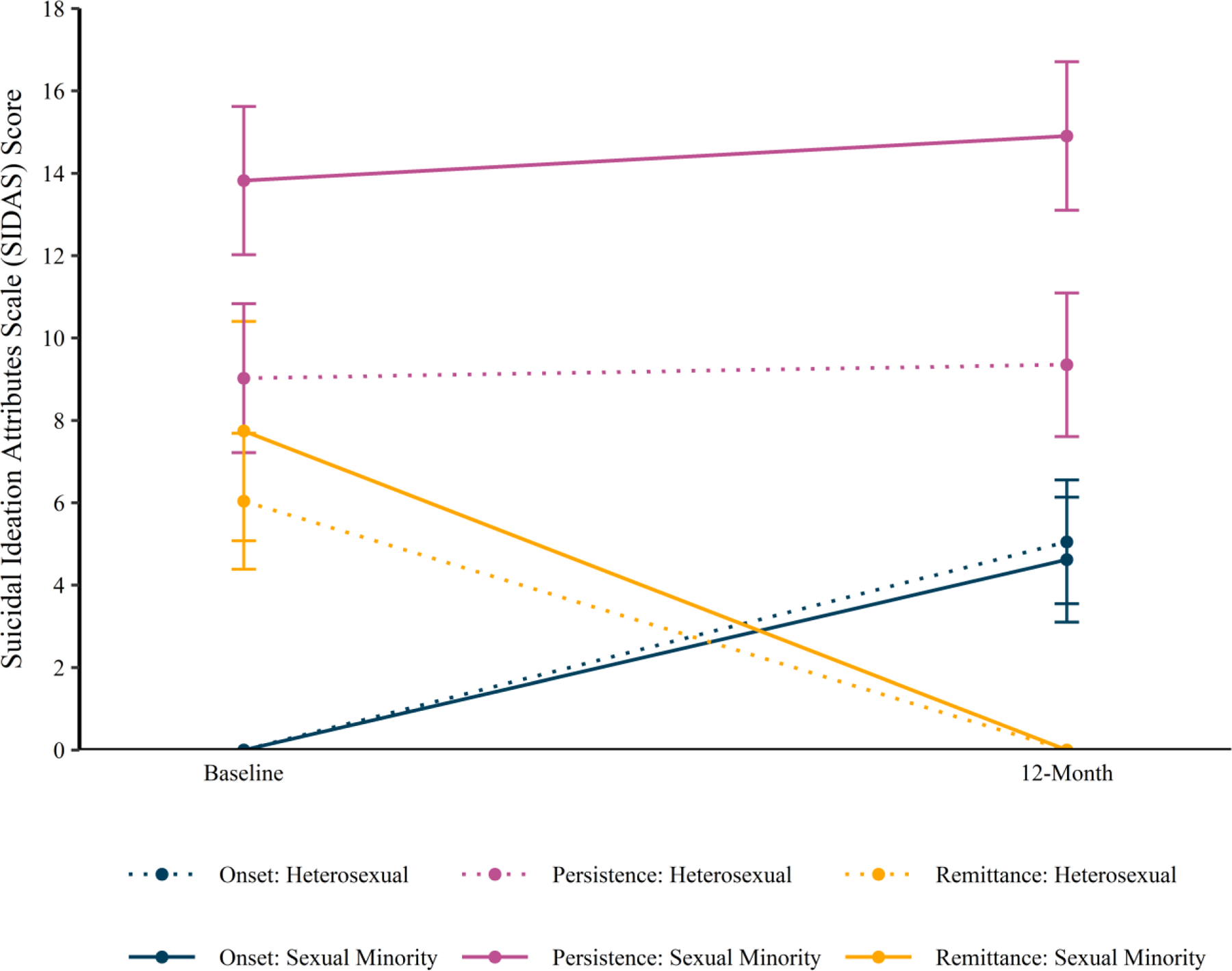

There was no evidence of sexual orientation differences in suicidality severity among those who experienced onset or who remitted (Figure 1). However, among those whose suicidality persisted, sexual minorities reported substantially higher severity (vs. heterosexuals) at both waves as depicted by non-overlapping 95% CIs.

Figure 1.

Suicidality severity with 95% confidence intervals by sexual orientation and 12-month suicidality onset, persistence, and remittance in a population-based cohort of young adults in Sweden

We conducted two sets of post-hoc analyses to examine whether particular subgroups of sexual minorities were at heightened risk. First, we examined plurisexual vs. lesbian/gay respondents, given elevated mental health risk among the former group [7]. The prevalence of onset and remittance did not differ between these groups; however, a substantially higher proportion of plurisexual respondents reported persistent suicidality (38.3%) compared to lesbian/gay respondents (27.5%; p<0.05). Second, we examined whether the persistence and severity of suicidality differed by age cohort among sexual minorities, given evidence that sexual minorities may experience two distinct periods of heightened risk for suicide, namely late adolescence (ages 17 to 25) and young adulthood (ages 26 to 34) [8,9]. In weighted frequency analyses, we found that a substantially higher proportion of sexual minorities ages 17 to 25 at baseline reported persistent suicidality (43.4%; 95% CI: 36.7%−50.1%) compared to sexual minorities ages 26 or older (25.7%; 95% CI: 20.2%−31.2%). However, among sexual minorities who reported persistent suicidality, there was no difference in the average suicidality severity at baseline and one-year follow-up between those ages 17 to 25 (mean = 14.7; 95% CI: 12.7–16.7) and ages 26 or older (mean = 13.7; 95% CI: 11.5–15.9; t-value = 0.90, p = 0.369).

Discussion

In a prospective, population-based cohort representing nearly 2.4 million Swedish young adults, we found that sexual minorities were substantially more likely to report persistent and severe suicidality compared to heterosexuals; further, plurisexual young adults and sexual minorities aged 25 and younger appeared to be at greatest risk for these outcomes. The current findings demonstrate that more than one-third of sexual minorities recruited for a national, population-based study without regard for suicide risk demonstrated persistent and severe suicidality, highlighting the public health imperative of suicide prevention efforts for this population.

A slightly higher proportion of sexual minorities remitted than heterosexuals; however, reasons for sexual minorities’ greater remittance are unknown and should be explored in future work. Future research with longer-term follow-up is also needed to capture the stability of persistence and remittance. Further, predictors of persistent suicidality are often different than predictors of onset [10]; thus, the current study calls for the identification of sexual orientation-related predictors of persistent suicidality to inform responsive clinical interventions.

These findings have several implications for research and intervention. Research is needed to examine whether evidence-based treatments that address chronic suicidality (e.g., dialectical behavior therapy [11]) require tailoring to address the unique concerns of sexual minorities. Further, future research conducted in other geographic regions is needed to determine the generalizability of these findings beyond the Swedish context, which has a highly supportive sociopolitical environment [12]. Additionally, future research involving younger individuals could help to determine whether the findings reported here also apply to childhood and early adolescence.

Regarding intervention implications, these findings underscore the need for comprehensive universal suicide risk assessment and prevention screening, especially in primary care settings where sexual minority young people may be represented, including colleges and universities [13] and sexual minority community health centers [14]. Additionally, given the high frequency of persistent and severe suicidality reported among sexual minority young adults in the general population, these findings also call for dissemination of sexual minority-affirmative mental health training for mental health professionals to bolster professionals’ clinical and cultural competence when working with sexual minorities at risk for suicide [15].

Funding statement:

This study was funded by the National Institute of Mental Health (MH, RB, JP, grant number R01MH118245). KC acknowledges funding support from the National Institute of Mental Health (grant number K01MH125073).

Footnotes

Declaration of interest: The authors have no relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose.

References

- 1.Haas AP, Eliason M, Mays VM, Mathy RM, Cochran SD, D’Augelli AR, et al. (2010) Suicide and suicide risk in lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender populations: review and recommendations. J Homosex 58(1):10–51. 10.1080/00918369.2011.534038 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fergusson DM, Horwood LJ, Ridder EM, Beautrais AL. (2005) Sexual orientation and mental health in a birth cohort of young adults. Psychol Med 35(7): 971–981. 10.1017/S0033291704004222 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wichstrøm L, Hegna K. (2003) Sexual orientation and suicide attempt: a longitudinal study of the general Norwegian adolescent population. J Abnorm Psychol 112(1):144. 10.1037/0021-843X.112.1.144 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fox KR, Hooley JM, Smith DM, Ribeiro JD, Huang X, Nock MK, et al. (2018) Self-injurious thoughts and behaviors may be more common and severe among people identifying as a sexual minority. Behav Ther 49(5):768–80. 10.1016/j.beth.2017.11.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Martínez-Alés G, Pamplin JR, Rutherford C, Gimbrone C, Kandula S, Olfson M, et al. (2021) Age, period, and cohort effects on suicide death in the United States from 1999 to 2018: moderation by sex, race, and firearm involvement. Mol Psychiatry 26(7):3374–3382. 10.1038/s41380-021-01078-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Van Spijker BA, Batterham PJ, Calear AL, Farrer L, Christensen H, Reynolds J, et al. (2014) The Suicidal Ideation Attributes Scale (SIDAS): Community‐based validation study of a new scale for the measurement of suicidal ideation. Suicide Life Threat Behav 44(4):408–19. 10.1111/sltb.12084 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ross LE, Salway T, Tarasoff LA, MacKay JM, Hawkins BW, & Fehr CP (2018). Prevalence of depression and anxiety among bisexual people compared to gay, lesbian, and heterosexual individuals: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Sex Res, 55(4–5), 435–456. 10.1080/00224499.2017.1387755 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Salway T, Gesink D, Ferlatte O, Rich AJ, Rhodes AE, Brennan DJ and Gilbert M, (2021) Age, period, and cohort patterns in the epidemiology of suicide attempts among sexual minorities in the United States and Canada: detection of a second peak in middle adulthood. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 56(2):283–294. 10.1007/s00127-020-01946-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Layland EK, Exten C, Mallory AB, Williams ND and Fish JN (2020) Suicide attempt rates and associations with discrimination are greatest in early adulthood for sexual minority adults across diverse racial and ethnic groups. LGBT Health 7(8):439–447. 10.1089/lgbt.2020.0142 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nock MK, Han G, Millner AJ, Gutierrez PM, Joiner TE, Hwang I, et al. (2018) Patterns and predictors of persistence of suicide ideation: Results from the Army Study to Assess Risk and Resilience in Servicemembers (Army STARRS). J Abnorm Psychol 127(7):650. 10.1037/abn0000379 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mehlum L, Ramberg M, Tørmoen AJ, Haga E, Diep LM, Stanley BH, et al. (2016) Dialectical behavior therapy compared with enhanced usual care for adolescents with repeated suicidal and self-harming behavior: outcomes over a one-year follow-up. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 55(4):295–300. 10.1016/j.jaac.2016.01.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hatzenbuehler ML, Bränström R, & Pachankis JE (2018). Societal-level explanations for reductions in sexual orientation mental health disparities: Results from a ten-year, population-based study in Sweden. Stigma Health 3(1):16–26. 10.1037/sah0000066 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Frick MG, Butler SA and deBoer DS (2021) Universal suicide screening in college primary care. J Am Coll Health 69(1):17–22. 10.1080/07448481.2019.1645677 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pachankis JE, Clark KA, Jackson SD, Pereira K and Levine D (2021) Current capacity and future implementation of mental health services in US LGBTQ community centers. Psychiatr Serv 72(6):669–676. 10.1176/appi.ps.202000575 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pachankis J, Soulliard Z, Seager van Dyk I, Layland E, Clark K, Levine D & Jackson S (2022) Training in LGBTQ-affirmative cognitive-behavioral therapy: A randomized controlled trial across LGBTQ community centers Unpublished Manuscript. Yale School of Public Health, New Haven, CT. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]