Abstract

Introduction.

While immunotherapy strategies such as immune checkpoint inhibition and adoptive T cell therapy have become commonplace in cancer therapy, they suffer from limitations, including lack of patient response and toxicity. To wield the maximum potential of the immune system, cancer immunotherapy must integrate novel targets and therapeutic strategies with potential to augment clinical efficacy of currently utilized immunotherapies. PTPN22, a member of the protein tyrosine phosphatase (PTP) superfamily that downregulates T cell signaling and proliferation, has recently emerged as a systemically druggable and novel immunotherapy target.

Areas covered.

This review describes the basics of PTPN22 structure and function and provides comprehensive insight into recent advances in small molecule PTPN22 inhibitor development and the immense potential of PTPN22 inhibition to synergize with current immunotherapies.

Expert opinion.

It is apparent that small molecule PTPN22 inhibitors have enormous potential to augment efficacy of current immunotherapy strategies such as checkpoint inhibition and adoptive cell transfer. Nevertheless, several constraints must be overcome before these inhibitors can be applied as useful therapeutics, namely selectivity, potency, and in vivo efficacy.

Keywords: Autoimmune disorders, immunotherapy, LYP, PTPN22, PTPN22 inhibitors

1. Protein Tyrosine Phosphatases and PTPN22

Protein tyrosine phosphorylation status regulates the initiation, propagation, and termination of cellular signaling cascades. Protein-tyrosine phosphatases (PTPs), along with the opposing action of protein tyrosine kinases (PTKs), control cellular levels of tyrosine phosphorylation [1–3]. Accordingly, PTPs play an integral role in cellular processes such as growth, differentiation, apoptosis, and metabolism [1–3]. Aberrant PTP activity is associated with numerous human pathologies, including cancer, diabetes, autoimmune disorders and developmental disorders [4–8]. Despite their immense potential as therapeutic targets, PTPs remain a largely untapped drug discovery resource due to innate difficulties in PTP drug discovery (highly conserved and positively charged active sites) and a limited understanding of PTP biology [7,8]. Consisting of 107 members, the PTP superfamily is grouped into four classes [2,9]. PTPN22 (also known as LYP in humans or PEP in mice), the subject of this review, is a classical non-receptor PTP within the proline-rich subclass within class I. PTPN22 is expressed predominantly in immune cells and is a key negative regulator of T-cell receptor (TCR) signal transduction [10]. Notably, a PTPN22 single nucleotide polymorphism (C1858T) causing a missense R620W mutation within a poly-proline motif is implicated in the development of numerous autoimmune disorders [10]. Herein, we succinctly discuss basic elements of PTPN22’s structure, function, and prevalence in autoimmunity and provide in-depth discussion on PTPN22 inhibitor discovery and application to immunotherapy, along with our expert opinion and current state and prospects of the field.

2. PTPN22 Structure, Catalytic Mechanism, and Regulation

Murine PTPN22 was first discovered in 1992 during molecular cloning experiments aimed at elucidating novel genes encoding PTP domains [11]. Soon after, the human homologue was cloned and determined to be expressed in the thymus and spleen [12]. As shown in Figure 1A, PTPN22 consists of an N-terminal PTP catalytic domain (residues 1–300), a central interdomain region (residues 301–600), and a C-terminus that includes four poly-proline motifs (residues 601–807) [10]. The crystal structure of PTPN22’s catalytic domain has been determined [13–15], offering insight into the enzyme’s function and regulatory mechanisms. As with other PTPs, the PTPN22 catalytic domain features a central eight-stranded β-sheet bordered by six α-helices on one side and two α-helices on the other side (Figure 1B) [13]. The P-loop, consisting of the PTP signature motif (H226CSAGCGR233), sits at the base of the active site, which possesses a highly positive charge (Figure 1C). R233 provides key salt-bridges to the substrate’s phosphate group, while the WPD loop (residues 193–204) houses the key general acid/base residue D195 and is conformationally dynamic [13]. PTPN22 also possesses a unique insert consisting of residues 35–42 (Figure 1B).

Figure 1.

Structural features of PTPN22. (A) Schematic of the structure of PTPN22. The three major domains of PTPN22 [PTP domain (amino acids 1–300), interdomain (amino acids 301–600), and C-terminal domain (amino acids 601–807)] are indicated. (B) X-ray crystal structure of PTPN22 catalytic domain (PDB code: 2QCT) showing an open WPD loop and the PTPN22-specific insert (S35TKYKADK42). (C) Surface representation of the same X-ray crystal structure of PTP domain as B showing the active site, colored according to electrostatic potential (blue, most positive; red, most negative). The images B and C were prepared with PyMOL (http://www.pymol.org/).

The mechanism of PTPN22 catalyzed dephosphorylation hinges on catalytic C227, which exists as a thiolate anion (pKa ~ 5) within the active site microenvironment [2]. Upon substrate binding to the P-loop, this nucleophilic cysteine attacks the phosphate group, initiating the dephosphorylation process. Phosphate group cleavage is paired with protonation of the substrate tyrosyl leaving group by the general acid D195. Hydrolysis of the phospho-enzyme intermediate is facilitated by Q274, which coordinates a water molecule near the phospho-enzyme intermediate. Activation of water by the now general base D195 regenerates free enzyme. Mutation of residues C227 and D195 produces catalytically dead enzyme incapable of turning over substrate and has been utilized as a substrate-trapping mutant [16]. The C-terminal region of PTPN22 harbors four poly-proline motifs (P1-P4) (Figure 1A), of which P1 has been shown to bind Csk, an important enzyme in T-cell signaling [12,17–19]. One mutational study suggested this interdomain region inhibits enzymatic activity via intramolecular interaction between the catalytic and interdomain regions [20]. Phosphorylation of PTPN22 S35 by protein kinase C (PKC) abolishes Lck Y394 dephosphorylation inside Jurkat cells by altering conformation of the specific insert [13]. Furthermore, PTPN22 may be regulated by reversible oxidation as one crystal structure shows presence of a disulfide bond between catalytic C227 and C129 [15].

3. PTPN22 Substrates and PTPN22’s Role in T-Cell Signaling

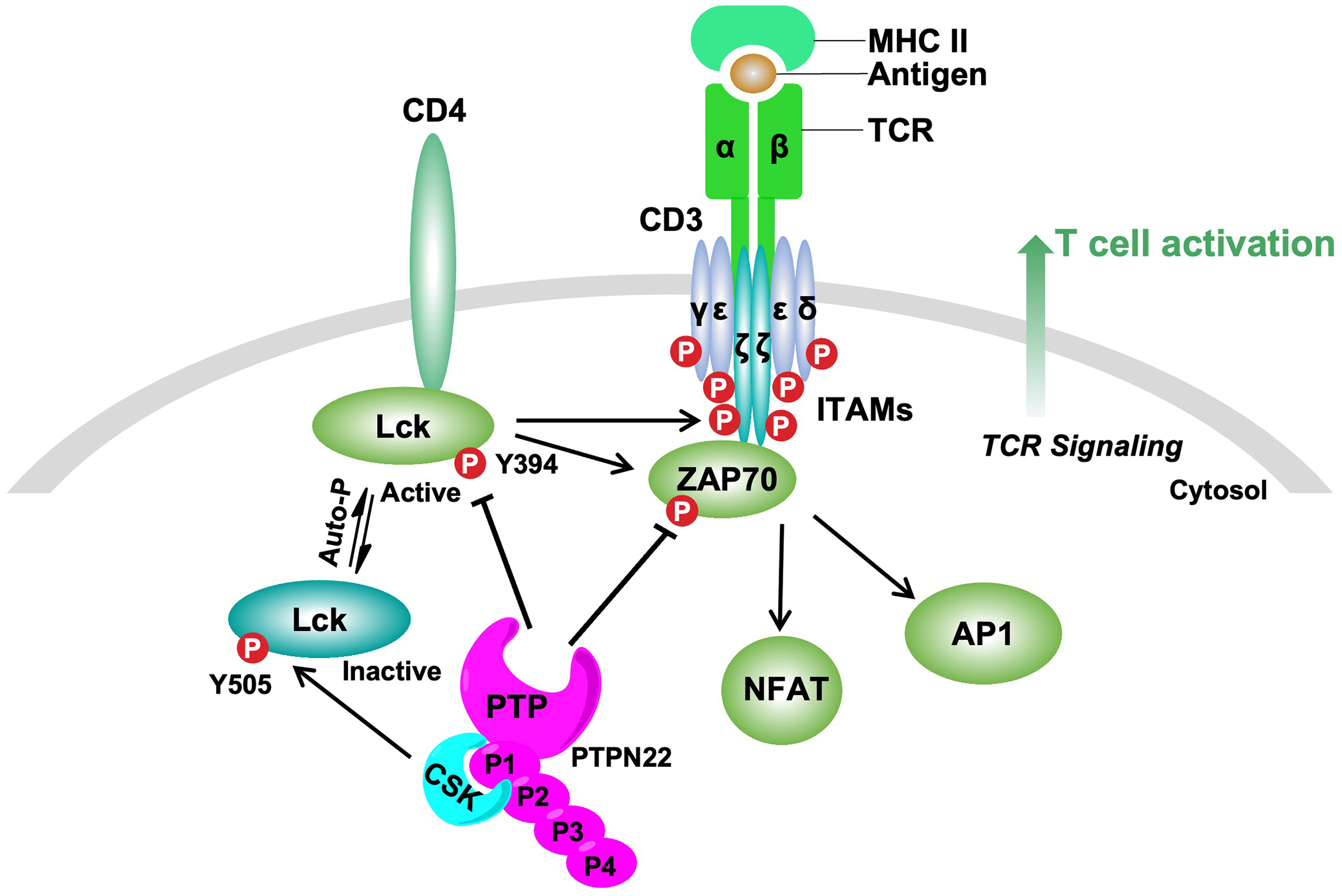

The T-cell signaling cascade (Figure 2) is initiated when an antigen ligand binds the TCR, resulting in deployment of the Src-family kinase Lck [21]. Autophosphorylation of Lck Y394 leads to a conformationally active enzyme, which phosphorylates tyrosine residues in the immunoreceptor tyrosine-based activation motifs (ITAMs) of the TCR-associated CD3 and zeta (ζ) chains [21]. Subsequently, the tandem Src homology 2 (SH2) domains of Zeta-associated protein kinase of 70 kDa (ZAP70) bind to these phosphorylated ITAMs, where it is phosphorylated and activated by Lck [21]. ZAP70 activity ultimately leads to activation of transcription factors, including nuclear factor of activated T-cells (NFAT) and activator protein 1 (AP1), cell growth, proliferation, and cytokine production (Figure 2) [21–26]. PTPN22 deficiency in T cells and small molecule inhibition of PTPN22 in Jurkat cells increases Lck Y394 phosphorylation [13,14,27–32]. PTPN22 was also shown to dephosphorylate TCR-CD3ζ, ZAP70 Y493, and VAV1 in substrate-trapping studies [16]. Proteins downstream of TCR signaling, such as the ATPase VCP/p97, were also implicated as PTPN22 substrates through substrate-trapping studies [16]. Dephosphorylation of the above substrates inhibits propagation of the TCR cascade and downregulates T cell signaling. Substrates needing further validation include c-Casitas B-lineage lymphoma (c-Cbl), Bcr-Abl, and Src kinase-associated protein of 55kDa homolog (SKAP-HOM) [10,12,33]. More studies are necessary to understand the functional interaction between PTPN22 and these proteins.

Figure 2.

Proposed function of PTPN22 in TCR signaling. PTPN22 behaves as a key negative regulator of T cell activation through dephosphorylation of mediators in signaling downstream of the TCR. The combined binding of major histocompatibility complex class II molecule (MHC II) to the TCR and the coreceptor CD4 initiates a signaling cascade, eventually resulting in formation of a multimeric signaling complex referred to as the ‘TCR signalosome’. The ‘TCR signalosome’ includes key signaling mediators (for example, Lck and ZAP70) and downstream adaptor proteins (for example, CD3 and zeta (ζ) chains). Upon TCR engagement, Lck become activated by phosphorylation in its activation motif (Y394). Then, Lck phosphorylates tyrosine residues in the immunoreceptor tyrosine-based activation motifs (ITAMs) of the TCR-associated CD3 and zeta (ζ) chains. Subsequently, the tandem Src homology 2 (SH2) domains of Zeta-associated protein kinase of 70 kDa (ZAP70) bind to these phosphorylated ITAMs, where it is phosphorylated and activated by Lck. ZAP70 activity ultimately leads to activation of transcription factors, including nuclear factor of activated T-cells (NFAT) and activator protein 1 (AP1). This signaling cascade leads to T cell activation. PTPN22 inhibits this process through dephosphorylation of the activating tyrosine of Lck and ZAP70, and other mediators of TCR signaling. Within this signaling cascade, PTPN22 forms a high stoichiometric complex with CSK, a kinase that inhibits Lck by phosphorylation on its negative regulatory tyrosine residue (Y505).

4. PTPN22-Csk Complex and PTPN22 R620W Variant

Csk, a potent negative regulator of T-cell signaling, phosphorylates the inhibitory Y505 in the C-terminus of Src family kinases such as Lck [34]. Lck inactivation requires both dephosphorylation of Y394 (in the activation loop) and phosphorylation of Y505 (stabilizes inactive conformation), thus complimentary activity of PTPN22 and Csk is surmised to lead to complete Lck inactivation [35,36]. A germline variant of PTPN22 (rs2476601), which results in the substitution of R620 for tryptophan (W) in the P1 poly-proline motif, abolishes the ability of PTPN22 to bind Csk. Unfortunately, there is no general agreement regarding the role of the PTPN22-Csk complex in TCR signaling. Co-expression of PTPN22-R620W or murine PTPN22-R619W with Csk leads to weakened inhibition of TCR signaling [37]. However, another study concludes that Csk promotes inhibitory phosphorylation of Y536 within the PTPN22 interdomain region [38]. Yet another study suggests Csk recruits PTPN22 to the lipid rafts, making its substrates inaccessible [35]. Nonetheless, rs2476601 was first linked to occurrence of type I diabetes [19], and multiple subsequent works have correlated this variant with numerous other autoimmune diseases [10,26].

5. PTPN22 R620W and Autoimmunity

While there is a host of data on PTPN22’s role in autoimmunity, comprehensive details are beyond the scope of this review. For detailed reviews on PTPN22 and autoimmunity, please see the following references [10,26,39]. Multiple studies have linked PTPN22 R620W to type I diabetes, rheumatoid arthritis, generalized vitiligo, systemic lupus erythematosus, immune thrombocytopenia, Grave’s disease, juvenile rheumatoid arthritis, Addison’s disease, myasthenia gravis, and idiopathic inflammatory myopathies [10,19,40]. This single nucleotide polymorphism in PTPN22 is most prevalent in Scandinavia and common in Northern Europeans [10,41]. Intuition would suggest that lack of this PTPN22-Csk interaction would lead to a loss of normal PTPN22 function, but conclusions have proven to be quite intricate. While initial studies suggested that PTPN22 R620W acted as a gain-of function mutant [42–46], others have reported that this variant constitutes a loss in function [47–49]. Furthermore, mice knocked-in for PTPN22 R619W (murine equivalent of PTPN22 R620W) phenocopy mice deficient in PTPN22 [50,51]. In agreement with the loss-of-function argument, PTPN22-deficient T cells [39,52,53], PTPN22-deficient mice [54, 58], and mice with PTPN22 R619W [55] possess enhanced T cell signaling. Likewise, studies show overexpression of PTPN22 R620W does not impede human CD4+ T cell activation [56]. Several hypotheses explaining this loss-of-function immunological phenotype include heightened calpain- and proteasomal-dependent degradation of the variant [50] and interference of PTPN22 R620W by a truncated isoform [57]. One group proposed a change-of-function model centered on the fact that the phosphoproteome for R620W is broader compared to that of WT PTPN22 [51]. Quite substantially, this variant, while increasing susceptibility to autoimmune disorders, was also found to confer protection against cancer in humans in several studies [54,55,58]. Collectively, these studies suggest PTPN22 may be targeted to enhance T cell function in cancer, particularly in the context of low affinity antigens.

6. PTPN22 as a Cancer Immunotherapy Target

PTPN22’s link to autoimmunity is quite interesting as there are multiple analogies between autoimmunity and tumor immunosurveillance [39,59,60]. Autoimmune T cells are hyperactive and recognize weak, self-antigens and resist downregulation mechanisms, while T cells in cancer do not respond to low-affinity tumor-associated antigens (TAAs) and are suppressed by restricted nutrients, hypoxia, presence of immunosuppressive cells (Tregs) and ligands (PD-L1/2), and high levels of immunosuppressive cytokines (TGFβ) [39]. Correspondingly, increasing T cell function via immunotherapy has become forefront in cancer therapy [61], illustrated by clinical application of immune checkpoint inhibitors (CPIs) and adoptive cell therapy (ACT). CPI therapy is characterized by obstruction of inhibitory immune receptors, encompassing antibodies to immune checkpoints programmed death 1 (PD-1) and cytotoxic lymphocyte antigen 4 (CTLA-4) [62,63]. ACT utilizes either engineered T cells expressing chimeric antigen receptors (CAR T cells) or tumor infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs) from patients, both of which result in tumor antigen recognition by T cells [64]. Nonetheless, these strategies possess limitations, namely non-responsiveness and toxicity in some patients [63,64], fueling exploration of novel immunomodulatory targets with potential to broaden immunotherapy options and offer new combination therapies that augment multiple pathways, thus improving clinical efficacy and safety. Targeting PTPN22, a key desensitization node in TCR signaling, has been shown to counter the immunosuppressive effects of TGFβ on T cells and enhance ACT and CPI efficacies across multiple tumor contextures.

Decreasing the activation threshold for TCR response to low affinity TAAs could greatly facilitate current immunotherapy strategies. Previously, increased IL-2 production in PTPN22-deficient CD8+ T cells was shown to neutralize the suppressive effects of TGFβ on TCR signaling [39,52,53]. Accordingly, ACT of PTPN22-deficient CD8+ T cells led to improved EL4 lymphoma tumor clearance in mice [39,53]. Moreover, these PTPN22-deficient CD8+ T cells produced more granzyme B (GzB) and IFNγ upon culture with ID8-T4 (low affinity antigen expressing) murine ovarian carcinoma cells in vitro and were more efficient at clearing ID8-T4 tumors in mice [53]. While both PTPN22-deficient and control cytotoxic T lymphocytes were equally effective at destroying ID8-N4 (high affinity) tumor cells in vitro, PTPN22-deficient CTLs were superior eradicating ID8-V4 (low affinity) tumor cells [52]. Expectedly, PTPN22-deficiency enhanced tumor reduction in both V4 and N4 ID8 tumors in mice upon CTL ACT, whereas control ACT had no effect on V4 (weak affinity antigen) tumor volume [52]. Of note, these ACT experiments were performed using the OT-1 TCR transgenic system, and N4, T4, and V4 refer to variants of the cognate ova-peptide. Conspicuously, PTPN22-deficient memory phenotype T cells also possessed significantly improved ability to destroy ID8-T4 cells in vitro, which persisted even after initial tumor clearance [52]. Likewise, PTPN22 deficiency increased memory phenotype T cell mediated EL4 tumor clearance in mice and increased IFNγ and TNF production [52]. Fully exhausted CD8+ T cells were formerly determined to be less efficient at eliminating tumors relative to memory phenotype T cells [65,66]. Markedly, PTPN22-deficiency prevents T cell exhaustion from chronic viral infections in mice [67,68]. Although this phenomenon is thought to be associated with interferon signaling and not intrinsic to T cells, these findings further highlight the potential of PTPN22-deficiency to increase tumor clearance. These data helped provide the impetus for studies on PTPN22 deficiency’s ability to synergize with checkpoint inhibitor therapy.

Association between adverse autoimmune-related events and clinical efficacy following CPI treatment has been documented [69,70], further inspiring studies on PTPN22 deficiency’s effects on CPI therapy. In combination therapy studies utilizing mice engrafted with colon adenocarcinoma tumor cell line MC38, 45% of PTPN22-deficient mice achieved complete response (CR) with anti-PD-L1 treatment, as compared to 20% for control (WT) mice [54]. Further analysis showed a significant increase in the absolute numbers of intratumoral CD8+ T cells and increases in the CD8/Treg ratio and tumor antigen specific CD8+ T cells, which is consistent with observed tumor shrinkage [54]. Moreover, increased levels of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells were present in draining lymph nodes (dLNs) of anti-PD-L1 treated PTPN22-deficient mice, along with increased CD8+ central memory T cells and CD4+ and CD8+ effector T cells. Increased expression of chemokine receptor CXCR3, activation marker ICOS, PD1, Ki-67, and GZMB followed expansion of CD8+ and CD4+ cells in these mice, confirming greater T cell activation and proliferation [54]. Antitumor immunity was also observed in other tumor models. Anti-PD-L1 treatment in PTPN22-deficient mice bearing CT26 tumors resulted in 50% CRs compared to no CRs in WT mice [54]. Furthermore, in a hepatocellular carcinoma tumor model, PTPN22-deficient mice achieved 50% spontaneous remissions (SRs), compared to no SRs in WT mice [54]. Notably, this suggested PTPN22 deficiency enhances anticancer immunity in different tumor contexts. Additional experiments revealed that loss of PTPN22 conferred spontaneous antitumor activity in both Hepa1-6.x1 hepatocellular carcinoma and E.G7-OVA tumor models [54]. Lastly, the autoimmune associated variant of PTPN22 (R620W), also referred to as rs2476601, was discovered to protect against development of non-melanoma skin cancers in human populations [54]. Many of these observations were corroborated independently by another group’s simultaneous studies (discussed below) on PTPN22.

Association of PTPN22 with immune regulation of cancer was also shown through a phenome-wide association study (PheWAS) [58]. In addition to the previously reported association of rs2476601 with autoimmune disorders such as rheumatoid arthritis, systemic lupus erythematosus, and thyroid disorders, a striking risk-preventive correlation between this variant and cancers of the skin, gastrointestinal tract, and central nervous system was observed [58]. Analysis of the Cancer Genome Atlas database showed significant correlation between PTPN22 expression and immune regulation markers in multiple cancer types, suggesting PTPN22 negatively regulates anticancer immunity [58]. Matching previous studies, PTPN22-deficient mice engrafted with MC38 cells showed markedly decreased tumor growth, gross tumor size, and tumor weights, as compared to WT mice [58]. Further analysis revealed increased presence of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells within the tumors, with increased levels of T-cells, tumor-associated macrophages (TAM) subsets, and NK cells, with cytotoxic CD8+ T-cells showing the greatest increase in PTPN22-deficient mice [58]. Importantly, pharmacologic abrogation of PTPN22 using small molecule inhibitor L-1, discussed in depth later in this review, revealed PTPN22 to be a systemically druggable immunotherapy target [58]. Expectedly, pharmacologic abrogation significantly reduced MC38 tumor growth in mice. Similar results were seen in mice with CT26 tumors. In both mouse models, modulation by L-1 led to highly enhanced presence of TAM, CD4+, and CD8+ T-cell subtypes [58]. Furthermore, combination of L-1 treatment and anti-PD-1 was significantly more efficacious at clearing tumors compared to either treatment alone. These findings highlight PTPN22 as a systemically druggable immunotherapy target that greatly augments anti-PD-1 efficacy.

7. Small-Molecule Inhibitors of PTPN22

Despite the potential high value of various PTP drug targets, PTPs remain a largely untapped therapeutic resource. Indeed, while over several dozen PTK kinase inhibitors are on the market, no PTP inhibitor has reached the clinic to date. Moreover, PTPs are generally labeled as undruggable targets due to the innate difficulty in PTP small molecule inhibitor development. Overall, PTPs possess highly conserved and positively charged active sites, making it difficult to obtain inhibitors with requisite selectivity and pharmacokinetic properties for clinical utility. Further exacerbating this difficulty is the limited understanding of PTP biology and disease. With amassing data implicating PTPN22 as a target for cancer immunotherapy, efforts in development of PTPN22 small-molecule inhibitors have been noted. Currently, all reported inhibitors engage the PTPN22 active site and possess competitive modes of inhibition, with the exception of two noncompetitive inhibitors. It is critical to note that reported IC50 values are from multiple laboratories and may be determined under differing assay conditions (i.e., use of substrate for IC50 measurement). Consequently, result comparisons may be challenging unless the same control compound and assay conditions were utilized. Likewise, inhibitor selectivity is crucial when analyzing changes in T cell signaling as multiple PTPs such as SHP-1, SHP-2, and CD45 also modulate TCR signaling [26].

Seminal work on development of PTPN22 inhibitors was based on a 6-hydroxybenzofuran-5-carboxylic acid scaffold (I-C11, Table 1), which possessed an IC50 of 4.6 ± 0.4 μM and greater than 7-fold selectivity against all examined PTPs (SHP2, HePTP, PTP-MEG2, FAP-1, VHR, CD45, LAR, and PTPα, with the exception of PTP1B (2.6-fold) [13]. Kinetic analyses revealed that I-C11 is a reversible, competitive inhibitor with a Ki of 2.9 ± 0.5μM. The cocrystal structure of PTPN22 in complex with I-C11 (PDB code 2QCT) shows the WPD-loop is fully open in the ligand-bound structure, with the inhibitor making contacts with both the active-site and a proximal site (Figure 3). The ligand’s carboxylic acid forms hydrogen bonds with the backbone amide of A229, the side chains of C227 and C129, and salt-bridges with R233 and K138. The ortho-hydroxyl further increases affinity through hydrogen bonds to E133, while the benzofuran ring π-π stacks with Y60 and participates in van der Waals with the side chains of Q274, A229, S228, and K138. The triazolidine ring makes van der Waals with Q274, while the distal naphthalene ring binds a peripheral site defined by F28, L29, and R33. Notably, the 2-phenyl ring of I-C11 is not resolved in the crystal structure, likely due to its flexibility and low contact with PTPN22. To assess effects on T-cell signaling in cells, Jurkat T cells expressing either wild-type PTPN22 or inhibitor insensitive PTPN22/S35E mutant were treated with I-C11 and anti-CD3 antibody. I-C11 increased TCR-stimulated Lck394 and ERK1/2 phosphorylation by 1.8- and 2.9-fold, respectively, in cells with WT PTPN22. No changes were seen when inhibitor insensitive PTPN22 was treated with I-C11, suggesting I-C11 augments T cell signaling by specific inhibition of PTPN22. Despite its high cellular efficacy, I-C11 possesses moderate potency and selectivity, and subsequent works focused on optimizing the scaffold.

Table 1.

Representative PTPN22 inhibitors reported in the literature.

| Inhibitor | Structure | IC50 (μM) | Ki (μM) | Mode of Inhibition |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| I-C11 |

|

4.6 ± 0.4a | 2.9 ± 0.5a | Competitive |

| 8b |

|

0.26 ± 0.01a | 0.11 ± 0.003a | Competitive |

| 526 |

|

0.27b | Not determined | Competitive |

| 4e |

|

Not determined | Not determined | Noncompetitive |

| A15 |

|

Not determined | 2.87 ± 0.03a | Competitive |

| NC1 |

|

4.3 ± 0.3a | Not determined | Noncompetitive |

| 9r |

|

2.85 ± 0.19a | 1.09 ± 0.22a | Competitive |

| 17 |

|

1.5 ± 0.3b | Not determined | Not determined |

| LTV-1 |

|

0.508b | 0.38 ± 0.06b | Competitive |

| L-1 |

|

1.4 ± 0.2a | 0.50 ± 0.03a | Competitive |

pNPP as substrate in kinetic assay;

DiFMUP as substrate in kinetic assay

Figure 3.

Cocrystal structure of PTPN22 in complex with I-C11 (PDB code: 2QCT) showing their detailed interactions. Hydrogen bonds and salt-bridge interactions are depicted as yellow dashed lines. Residues involved in hydrophobic and π-π stacking interactions are represented in a stick model. The image was prepared with PyMOL (http://www.pymol.org/).

Ensuing work on the 6-hydroxybenzofuran-5-carboxylic acid scaffold through a focused library approach yielded compound 8b (Table 1), which possessed an IC50 of 0.26 ± 0.01μM with at least 9-fold selectivity against a broad panel of PTPs (PTP1B, SHP1, SHP2, TC-PTP, HePTP, PTP-Meg2, PTP-PEST, FAP1, and PTPH1, the receptor-like PTPs, CD45, LAR, PTPα, PTPβ, PTPε, PTPγ, PTPμ, and PTPσ, etc.) [14]. Kinetic analyses revealed 8b is a competitive inhibitor with a Ki of 110 ± 3nM. The 8b-PTPN22 cocrystal structure (Figure 4) was obtained and details the structural basis of PTPN22 inhibition by 8b, which binds in a different orientation than I-C11. 8b’s carboxylic acid moiety makes hydrogen bonds with the side chain of R233 and Q278 and the backbone of C231. The salicylic acid hydroxyl group makes hydrogen bonds with the backbone amides of S228 and A229 and the R233 side chain. The benzofuran ring π-π stacks with Y60 and makes van der Waals contacts with the side chains of Q274, A229, and S228. The 2-phenyl ring of 8b π-π stacks with Y60 and makes van der Waal contacts with the D62 side chain. The cyclopropanamide carbonyl forms hydrogen bonds with the backbone of K61 and K62 and makes hydrophobic contacts with Y60, K61, and D62. The 3-chlorophenyl ring participates in van der Waals with the side chains of Q274 and T275. Compound 8b attenuated early TCR signaling and increased the phosphorylation of ZAP70 on Y319 in Jurkat T cells treated with 15μM 8b. 8b also induced downstream activation of TCR signaling, assessed by CD69 surface expression upon treatment with 15μM 8b. 8b was also active in mouse thymocytes and inhibited murine PTPN22. 8b was also shown to be active in vivo by down-regulating mast cell action and anaphylaxis in mice. Significantly, 8b, unlike I-C11, does not interact with the distal second site, which is equivalent to a second binding pocket in PTP1B. This may partially explain 8b’s improved selectivity.

Figure 4.

Cocrystal structure of PTPN22 in complex with 8b (PDB code: 4J51) showing their detailed interactions. Hydrogen bond interactions are depicted as yellow dashed lines. Residues involved in hydrophobic and π-π stacking interactions are represented in a stick model. The image was prepared with PyMOL (http://www.pymol.org/).

Guided by the previously reported compound I-C11 and its cocrystal structure with PTPN22, a library of small-molecule PTPN22 inhibitors was generated through click chemistry [29]. The naphthalene ring of I-C11 bound an additional pocket formed by F28, L29, K32, and R33 [13], thus modifications were made on the naphthalene ring in an attempt to enhance binding affinity. Furthermore, substitutions on the 2-phenyl ring, which was not resolved in the I-C11 cocrystal structure due to presumed flexibility and low protein contact, were made in hopes of increasing the affinity with PTPN22. The majority of analogs possessed greater potency than I-C11, with substitution by bromine on the naphthalene ring and methyl on the 2-phenyl ring (compound 526 in Table 1) proving most potent (IC50 0.27 μM). SAR analysis revealed substitution by methyl on the 2-phenyl ring to be the main driver of increased potency. Overall, presence of naphthalene proved more potent than substitution by phenyl, pyrene, cyclohexane, or quinoline rings. Molecular docking experiments revealed substitution on the 2-phenyl ring by methoxy and methyl make additional contacts with PTPN22, with the methoxy making electrostatic interactions with D195 and E277 through water-mediate hydrogen bonds. Multiple analogs showed increased NFAT/AP-1 activation in a luciferase assay compared to I-C11 and also increased the amount of phosphorylated Lck 394 and ζ in Jurkat cells to DMSO controls. Despite their improved cellular potencies, these compounds proved poorly selective against PTP1B, SHP1, CD45, HePTP, and LAR.

In addition to competitive inhibitors, noncompetitive PTPN22 small molecule inhibitors have been reported. One such inhibitor, 4e (Table 1), was discovered from a screen of 4,000 drug-like molecules [31]. Kinetic analyses and comparison to known competitive PTPN22 inhibitor I-C11 [13] suggested that 4e shows mixed inhibition with a significant noncompetitive component. Furthermore, dual inhibition plots show that binding of I-C11 and 4e are nonmutual. Moreover, peptide amide hydrogen/deuterium exchange mass spectrometry (DXMS) analysis revealed 4e interacts with the α1’ and α2’ helices of PTPN22. Docking studies and mutational analysis of L29 suggest 4e binds to a hydrophobic region outside the active site and interacts with several key residues. According to the model, 4e forms hydrogen bonds with R266 and S271 and hydrophobic contacts with PTPN22. 4e also enhanced T cell signaling in cells.

Using the crystal structure of previously reported inhibitor 8b [14] complexed with PTPN22 (PDB 4J51), Hou and coworkers performed a target-ligand interaction-based virtual screen and obtained multiple novel scaffolds against PTPN22 with Ki values ranging from 2.87 to 28.03μM, along with a covalent inhibitor with a Ki of 40.98 ± 13.19μM [30]. The most potent compound, A15, (Table 1) had a Ki of 2.87 ± 0.03μM and a competitive mode of inhibition. Molecular docking studies revealed putative hydrogen bonds and a salt bridge between the A15 carboxyl group and R233 and Q278. Additional interactions included π-π stacking of Y60 and the central phenyl ring of A15. Although moderately potent, A15 only possessed at least 2-fold selectivity for PTPN22 against a panel of PTPs (including PTPN18, STEP, MEG2, PTP1B, SSH2, PPM1A, and PPM1G) except for PTP1B. However, three other inhibitors (A2, A19, and A26) exhibited 3- to 5-fold selectivity for PTPN22 [30]. A15 and A19 enhanced TCR-induced phosphorylation of Lck at Y394 and phosphorylation of ERK. Ability of inhibitors to modulate TCR-mediated transcriptional activation of IL-2 was assessed by T-cell based NFAT/AP-1 reporter assays. Compounds A15 and A19 led to a greater than 2-fold higher firefly luciferase ratios than control vehicle, indicating these inhibitors promote the activation of TCR-mediated transcription. Lastly, A15 and A19 showed no effects on Lck and ERK phosphorylation in cells knocked down for PTPN22 with siRNA, suggesting their effects result from on-target interactions. Importantly, this study offers an alternative approach to discovery of novel PTPN22 inhibitors through a combination of pharmacophore-based screening and molecular docking experiments, along with providing multiple leads for further development.

Through a hit-based similarity search of their previously reported 2-iminothiazolidin-4-one inhibitor, A15 and its analogs, Li et al. reported a noncompetitive inhibitor for PTPN22 that binds both the active-site and a WPD pocket [32]. Compound NC1 (Table 1) had an IC50 of 4.3 ± 0.3 μM and at least 1.9-fold selectivity against a panel of PTPs (PTP1B, VHR, STEP, N18, Glepp, Slingshot2, etc.). Interestingly, NC1 showed a competitive mode of inhibition for the other PTPs tested. NC1 augmented the phosphorylation levels of ERK and Lck in T-cells. NC1 showed no effects on this phosphorylation in T-cells lacking endogenous PTPN22 expression, suggesting the T-cell signaling effects are a result of inhibition of PTPN22. Mutagenesis studies, computational fragment-centric topographic mapping, and molecular dynamics (MD) simulations indicated NC1 concurrently binds a WPD pocket and a secondary pocket beyond the active site. F19 NMR spectroscopic studies revealed NC1 restricts catalytically necessary WPD-loop closure.

Previously reported inhibitor A15 [30], discovered through assimilation of ligand and structure-based virtual screening, was modified via scaffold-hopping, yielding compound 9r (Table 1) [71]. The thiazolo [3,2-a] pyrimidin core of A15 was simplified to generate imidazolidine-2,4-dione and 2-thioxothiazolidin-4-one scaffolds. The most active compound, 9r, contained a cinnamic acid and possessed an IC50 of 2.85 ± 0.19μM and a competitive mode of inhibition with a Ki of 1.09 ± 0.22μM. Inhibitor 9r exhibited at least 5.4-fold selectivity against PTPN12, PTP1B, Glepp1, STEP, and SSH2. Molecular docking studies revealed the cinnamic acid formed hydrogen bonds with R233 and Q278, while the central aromatic ring π-π stacks with Y60. The N-phenyl substituted 2-thioxothiazolidine-4-one moiety bound to a pocket formed by R59, L106, S107, K136, and E140. The chlorine atom 9r also participated in a halogen bond with the side chain of S107. 9r was shown to increase levels of pLck394 and pERK in Jurkat cells.

Quite interestingly, one PTPN22 inhibitor was discovered through screening of Au(I) complexes. Due to previous reports of Au containing drugs inhibiting PTPs, the thiophilicity of Au, and use of gold (I) complexes in therapeutics, Karver et al. screened a library of gold (I) complexes derived from the drug auranofin against a panel of PTPs [72]. Several of these compounds were selective for PTPN22 against PTP-PEST, and markedly, compounds were inactive in the absence of Au. Notably, both selectivity and inhibition of PTPN22 differed for some compounds depending on the substrate used during screening. Top compound (compound 17, Table 1) possessed an IC50 of 1.5 ± 0.3 μM with 10-fold selectivity over PTP-PEST, HePTP, and CD45. Cellular studies showed increased phosphorylation of Lck Y394 and no changes in phosphorylation of Lck Y505, thus 17 does not inhibit CD45.

As part of an effort to corroborate the importance of PTPN22-Csk dissociation to downregulation of TCR signaling, Tautz and coworkers screened 50,000 drug-like molecules for PTPN22 inhibition [35]. Follow-up studies revealed 190 compounds displayed dose-dependent PTPN22 inhibition, with IC50 values ranging from 0.047 to 16.8μM. 33 of these compounds showed varying degrees of selectivity for PTPN22, with four inhibitors possessing dose-dependent augmentation of TCR-induced activation of proximal IL-2 reporter. One inhibitor in particular, LTV-1 (Table 1), dose-dependently enhanced TCR-signaling and showed increased Lck394 and ζ-chain phosphorylation in Jurkat cells. While LTV-1 could not be successfully docked into the active-site of WPD-closed PTPN22, LTV-1 was docked into the active site of WPD-open PTPN22. These docking experiments identified multiple hydrogen bonds between the benzoic acid moiety to the P-loop, thus mimicking phosphotyrosine of natural substrates. The ligand’s ether group also participates in van der Waals with the T275 side chain, while the benzylidene ring forms a cation-π interaction with the guanidinium group of R233. Finally, the scaffold’s toluene ring participates in hydrophobic interactions with a small hydrophobic pocket near the P-loop. LTV-1 possessed competitive to mixed inhibition with a Ki of 0.384 ± 0.061 μM. In vitro, specificity of LTV-1 for PTPN22 ranges to 3-fold for TCPTP and PTP1B, 46-fold over SHP1, 59-fold over CD45, and over 200-fold over PTP-PEST. LTV-1 treatment in Jurkat cells resulted in increased TCR-mediated T cell signaling. Treatment of HeLa cells, which do not express PTPN22, with LTV-1 showed no effects on cell viability, ruling out cytotoxicity of the scaffold.

In the first reported pharmacological approach to measure PTPN22’s potential in immunotherapy, a quinolone carboxylic acid scaffold was reported through a fragment-based approach [58]. This inhibitor, L-1 (Table 1), has an IC50 of 1.4 ± 0.2 μM with 7- to 10-fold selectivity for PTPN22 over 16 similar PTPs. Furthermore, L-1 has a Ki of 0.50 ± 0.03 μM and displayed competitive inhibition. Intraperitoneal administration in mice at 10mg/kg showed an average AUC of 4.55 μM·h and Cmax of 1.11 μM. To our knowledge, L-1 is the only PTPN22 inhibitor with reported in vivo pharmacokinetic activity. Strikingly, treatment of mouse MC38 xenograft model with L-1 led to diminished tumor growth compared to the control group, phenocopying studies using PTPN22-deficient mice. Moreover, L-1 treatment showed comparable antitumor effects in a CT26 model. Infiltration of TAM, CD8+, CD4+ T-cell subtypes were enhanced in L-1 treated MC38 tumor models. PTPN22 abrogation resulted in higher expression of CD69, PD-1, and LAG3 in T-cells, and CD69, and granzyme B in natural killer (NK) cells. Similar results were observed in the CT26 tumor model. Consistent with genetic studies, L-1 treatment in MC38 tumor model resulted in increased infiltration of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells, which is consistent with observation of tumor clearance. Notably, this increased immune response was determined to be dependent on PTPN22 as treatment of MC38 tumors with either vehicle or L-1 in PTPN22-deficient mice showed no appreciable differences in tumor growth. Expectedly, treatment of mice with L-1, but not an inactive but structurally similar compound, led to increased phosphorylation of Lck Y394 and ZAP70 Y493 in CD8+ T cells. Consistent with previously reported genetic data [54], pharmacological inhibition of PTPN22 enhanced anti-PD-1 therapy in both MC38 and CT26 models. This enhancement was superior to either monotherapy with either L-1 or anti-PD-1 only. Quite significantly, this study established PTPN22 as a systemic cancer immunotherapy target that can be modulated by small molecule inhibitors and exploited in both monotherapy and combination therapy with known CPIs.

Although not well-characterized, other reported PTPN22 inhibitors include 2-benzamidobenzoic acid derivatives from a high throughput virtual screen [73] and thiazolidine-2,4-diones and 2-thioxothiazolidin-4-ones scaffolds [74]. A covalent PTPN22 inhibitor was discovered by screening the NIH Molecular Libraries Small Molecules Repository, but selectivity data is lacking [75]. While not yet ready for advancement into clinical trials, the above compounds may provide promising leads for further development of PTPN22 inhibitors.

7. Conclusion.

PTPN22 is a key desensitization node in T cell signaling and immune response with multiple validated substrates and several putative ones. While there is still debate concerning the exact role of the R620W variant in autoimmunity, numerous studies have shown this mutation is beneficial in an oncology context. Global PTPN22 deletion enhances anti-tumor immunity and the response of effector T cells to antigens. PTPN22 deficiency/R620W variant enhances efficacy of both adoptive cell transfer and immune checkpoint inhibition therapies. PTPN22 targeting offers a systemic and validated approach for novel immunotherapies and combination strategies. Furthermore, correlation of the autoimmune-associated variant with diminished risk of cancer and more efficacious CPI response suggests PTPN22 may offer a valuable biomarker for immunotherapy response and precision oncology. Several small molecule PTPN22 inhibitors exist, with varying degrees of biological characterization for each. Strategies for their discovery include fragment and structure-based design, ligand-based design, virtual screening via docking and/or pharmacophore modeling, and high-throughput screening.

8. Expert Opinion.

We have come quite a long way from the discovery of PTPN22 to elucidating its structure, linking its R620W variant to autoimmune disorders, and implicating it as a cancer immunotherapy target. Several small molecule inhibitors have been developed and have corroborated genetic and biological evidence, such as PTPN22 substrates and role in immune response, while also providing the foundation for further drug discovery and optimization efforts. To date, major weaknesses of the field encompass an incomplete understanding of the role of the R620W variant in T cell signaling and generation of inhibitors with requisite properties for clinical utility. Regarding the R620W variant, many of the conclusions rely on overexpression studies, which are limited by comparable expression of both PTPN22 and other TCR effector proteins across different studies. Recently, immunotherapies such as checkpoint inhibition and adoptive T cell strategies have created exciting immunotherapies but are still hindered by their efficacy and toxicity profiles across a broad range of human patients. Correspondingly, novel immunotherapy targets are warranted to expand the arsenal of treatment options and allow for more robust combination therapies with greater efficacy and lower toxicity.

PTPN22 deletion and pharmacological abrogation by inhibitor L-1 reveal PTPN22 is a systemic and translatable target for immunotherapy. Excitingly, data suggests PTPN22 inhibition enhances T cell functionality while also countering the immunosuppression of tumor associated macrophages, thus offering a synergy that is not present in other T cell approaches (i.e., CAR T therapy). For eventual clinical translation of small molecule PTPN22 inhibitors, further improvements in potency, selectivity, drug-like properties and in vivo efficacy will be required. We believe that application of sound medicinal chemistry principles, combined with proactive attention to pharmacokinetic and drug-like properties and structure-based approaches for obtaining selectivity, will yield inhibitors that will ultimately be pushed into clinical studies, offering an electrifying new class of small molecules for immunotherapy. The PTPN22 drug discovery process could be greatly facilitated by advances in structural biology techniques (i.e., Cryo-EM or X-ray crystallography capabilities). For instance, different conformations of the WPD-loop could be exploited in inhibitor development. Furthermore, it’s not beyond the realm of possibility that generation of a full-length PTPN22 structure may reveal allosteric pockets, especially given the proposed intermolecular interaction between a motif of the interdomain and the catalytic domain. Continued advancements in computational techniques such as docking (particularly scoring functions) and molecular dynamics could also bolster these efforts. In the coming years, we envision that the role of PTPN22 in anti-cancer immunity will be clearer and studies combining targeting PTPN22 with other immunotherapies (such as cancer vaccines and cytokine treatments) will offer further compelling evidence of PTPN22’s therapeutic value. Quite provocatively, we believe that further efforts will generate clinically useful PTPN22 inhibitors, helping erase the stigma that PTPs are undruggable targets.

It is both significant and important to note that the majority of published PTPN22 inhibitors were created as potential therapies for autoimmunity [76], but much evidence suggests PTPN22 may not be a gain-of-function mutant. To our knowledge, no PTPN22 inhibitors have been tested in reliable models of autoimmunity in humans. In addition to orthosteric small molecules, future campaigns may try allosteric targeting by screening for inhibitors of full-length PTPN22 and discarding those that show inhibition against the catalytic domain. Additionally, the proteolysis targeting chimera (PROTAC) or hydrophobic tagging strategies based on current inhibitors may also yield a new modality of PTPN22 abrogation [77]. Finally, gene modification through CRISPR/Cas9 has been clinically used in adoptive cell transfer [80,81] and could be expanded to targeting PTPN22. Indeed, multiple studies editing PTPN22 with CRISPR/Cas9 in the context of immunotherapy have been published [55,82,83]. In one such study, deletion of PTPN22 in Jurkat cells lead to enhanced IL-2 production and TCR signaling [82]. Yet another paper showed CRISPR/Cas9 deletion of PTPN22 did not enhance efficacy of CAR T cell therapy in solid tumors, but these CAR T cells engaged high and not low-affinity antigens [83]. Importantly, this further emphasizes targeting PTPN22 in the context of low-affinity antigens. Lastly, PTPN22 could be targeted with siRNA as previously reported [84].

Article Highlights.

PTPN22 is a protein tyrosine phosphatase that negatively regulates T cell signaling.

PTPN22 is a novel, systemic, and translatable immunotherapy target.

There are multiple small molecule PTPN22 inhibitors to guide further optimization efforts.

Inhibition of PTPN22 by L-1 provides a compelling approach as a novel immunotherapy.

Presence of the R620W SNP may serve as a novel predictive biomarker for immunotherapy response by patients.

Funding:

This work was supported in part by the National Institutes of Health under grants R01CA69202 and R01CA207288.

Footnotes

Declaration of Interest:

The authors have no other relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript apart from those disclosed.

Reviewer Disclosures:

Peer reviewers on this manuscript have no relevant financial or other relationships to disclose.

Contributor Information

Brenson A. Jassim, Department of Medicinal Chemistry and Molecular Pharmacology, Purdue Institute for Drug Discovery, 720 Clinic Dr, West Lafayette, IN 47907.

Jianping Lin, Department of Medicinal Chemistry and Molecular Pharmacology, Purdue Institute for Drug Discovery, 720 Clinic Dr, West Lafayette, IN 47907.

Zhong-Yin Zhang, Distinguished Professor of Medicinal Chemistry, Robert C. and Charlotte P. Anderson Chair in Pharmacology, Director, Purdue Institute for Drug Discovery, 720 Clinic Dr, West Lafayette, IN 47907..

References

- 1.Hunter T Tyrosine phosphorylation: thirty years and counting. Curr Opin Cell Biology. 2009;21(2):140–146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tonks NK. Protein tyrosine phosphatases: from genes, to function, to disease. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2006;7(11):833–846 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; *informative review of PTP biology

- 3.Tonks NK. Protein tyrosine phosphatases - From housekeeping enzymes to master regulators of signal transduction. FEBS Journal 2013;280:346–378 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhang ZY. Protein tyrosine phosphatases: prospects for therapeutics. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 2001;5(4):416–423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tautz L, Pellecchia M, Mustelin T. Targeting the PTPome in human disease. Expert Opin Ther Targets 2006;10(1):157–177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Julien SG, Dubé N, Hardy S, et al. Inside the human cancer tyrosine phosphatome. Nat Rev Cancer 2011;11(1):35–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; *nicely summarizes roles of various PTPs in cancer

- 7.Zhang ZY. Drugging the Undruggable: Therapeutic Potential of Targeting Protein Tyrosine Phosphatases. Acc Chem Res 2016;50(1):122–129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; ** highlights the hurdles and approaches in developing small molecule inhibitors of PTPs.

- 8.de Munter S, Köhn M, Bollen M. Challenges and Opportunities in the Development of Protein Phosphatase-Directed Therapeutics. ACS Chem Biol 2013;8(1):36–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; *another key review summarizing the potential of protein phosphatase-based therapeutics

- 9.Alonso A, Sasin J, Bottini N, et al. Review Protein Tyrosine Phosphatases in the Human Genome. Cell 2004;117:699–711 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bottini N, Peterson EJ. Tyrosine phosphatase PTPN22: Multifunctional regulator of immune signaling, development, and disease. Annu Rev Immunol 2014;32:83–119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; ** an excellent review on PTPN22 immunoregulation function and role in autoimmunity

- 11.Matihews RJ, Bowne DB, Flores E, et al. Characterization of Hematopoietic Intracellular Protein Tyrosine Phosphatases: Description of a Phosphatase Containing an SH2 Domain and Another Enriched in Proline-, Glutamic Acid-, Serine-, and Threonine-Rich Sequences. Mol Cell Biol 1992;12(5):2396–2405 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cohen S, Dadi H, Shaoul E, et al. Cloning and Characterization of a Lymphoid-Specific, Inducible Human Protein Tyrosine Phosphatase, Lyp. Blood 1999;93(6):2013–24 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; **landmark discovery and identification of human PTPN22

- 13.Yu X, Sun J-P, He Y, et al. Structure, inhibitor, and regulatory mechanism of Lyp, a lymphoid-specific tyrosine phosphatase implicated in autoimmune diseases. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2007;104(50):19767–72 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; **seminal discovery of a small molecule PTPN22 inhibitor and first reported PTPN22 crystal structure

- 14.He Y, Liu S, Menon A, et al. A potent and selective small-molecule inhibitor for the lymphoid-specific tyrosine phosphatase (LYP), a target associated with autoimmune diseases. J Med Chem 2013;56:4990–5008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; *discovery of the highly potent and selective PTPN22 inhibitor 8b

- 15.Tsai SJ, Sen U, Zhao L, et al. Crystal Structure of the Human Lymphoid Tyrosine Phosphatase Catalytic Domain: Insights into Redox Regulation. Biochemistry 2009;48(22):4838–4845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wu J, Katrekar A, Honigberg LA, et al. Identification of substrates of human protein-tyrosine phosphatase PTPN22. J Biol Chem 2006;281(16):11002–10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; *discovery of multiple PTPN22 substrates involved in TCR signal propagation

- 17.Cloutier J-F, Veillette A Cooperative Inhibition of T-Cell Antigen Receptor Signaling by a Complex between a Kinase and a Phosphatase. J Exp Med 1999;189(1):111–21 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cloutier JF, Veillette A. Association of inhibitory tyrosine protein kinase p50csk with protein tyrosine phosphatase PEP in T cells and other hemopoietic cells. EMBO J 1996;15(18):4909–18 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bottini N, Musumeci L, Alonso A, et al. A functional variant of lymphoid tyrosine phosphatase is associated with type I diabetes. Nature Genetics. 2004;36(4):337–338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Liu Y, Stanford SM, Jog SP, et al. Regulation of Lymphoid Tyrosine Phosphatase Activity: Inhibition of the Catalytic Domain by the Proximal Interdomain. Biochemistry 2009;48(31):7525–32 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Courtney AH, Lo WL, Weiss A. TCR Signaling: Mechanisms of Initiation and Propagation. Trends Biochem Sci 2018;43(2):108–123 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; *nice summary of T cell signal propagation

- 22.Smith-Garvin JE, Koretzky GA, Jordan MS. T Cell Activation. Annu Rev Immunol 2009;27:591–619 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; *another nice review discussing TCR signaling

- 23.Mustelin T, Vang T, Bottini N. Protein tyrosine phosphatases and the immune response. Nat Rev Immunol 2005;5(1):43–57 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kane LP, Lin J, Weiss A. Signal transduction by the TCR for antigen. Curr Opin Immunol 2000;12(3):242–249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tybulewicz VLJ. Vav-family proteins in T-cell signalling. Curr Opin Immunol 2005;17(3):267–274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Castro-Sanchez P, Teagle AR, Prade S, et al. Modulation of TCR Signaling by Tyrosine Phosphatases: From Autoimmunity to Immunotherapy. Front Cell Dev Biol 2020;8:1541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hasegawa K, Martin F, Huang G, et al. PEST Domain-Enriched Tyrosine Phosphatase (PEP) Regulation of Effector/Memory T Cells. Science 2004;303(5658):685–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Maine CJ, Hamilton-Williams EE, Cheung J, et al. PTPN22 Alters the Development of Regulatory T Cells in the Thymus. J Immunol 2012;188(11):5267–5275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Vang T, Xie Y, Liu WH, et al. Inhibition of lymphoid tyrosine phosphatase by benzofuran salicylic acids. J Med Chem 2011;54(2):562–571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hou X, Li R, Li K, et al. Fast identification of novel lymphoid tyrosine phosphatase inhibitors using target-ligand interaction-based virtual screening. J Med Chem 2014;57(22):9309–9322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; *this study provided multiple lead compounds for further development through virtual screening

- 31.Stanford SM, Krishnamurthy D, Falk MD, et al. Discovery of a Novel Series of Inhibitors of Lymphoid Tyrosine Phosphatase with Activity in Human T Cells. J Med Chem 2011;54(6):1640–1654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; *first report of a noncompetitive PTPN22 inhibitor

- 32.Li K, Hou X, Li R, et al. Identification and structure-function analyses of an allosteric inhibitor of the tyrosine phosphatase PTPN22. J Biol Chem 2019;294(21):8653–8663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; *established targeting PTPN22 loop closure through allostery

- 33.Yu X, Chen M, Zhang S, et al. Substrate specificity of lymphoid-specific tyrosine phosphatase (Lyp) and identification of Src kinase-associated protein of 55 kDa homolog (SKAP-HOM) as a Lyp substrate. J Biol Chem 2011;286(35):30526–30534 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schmedt C, Saijo K, Niidome T, et al. Csk controls antigen receptor-mediated development and selection of T-lineage cells. Nature 1998;394(6696):901–904 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Vang T, Liu WH, Delacroix L, et al. LYP inhibits T-cell activation when dissociated from CSK. Nat Chem Biol 2012;8(5):437–446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gjörloff-Wingren A, Saxena M, Williams S, et al. Characterization of TCR-induced receptor-proximal signaling events negatively regulated by the protein tyrosine phosphatase PEP. Eur J Immunol 1999;29(12):3845–54 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Menard L, Saadoun D, Isnardi I, et al. The PTPN22 allele encoding an R620W variant interferes with the removal of developing autoreactive B cells in humans. J Clin Invest 2011;121(9):3635–44 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fiorillo E, Orrú V, Stanford SM, et al. Autoimmune-associated PTPN22 R620W Variation Reduces Phosphorylation of Lymphoid Phosphatase on an Inhibitory Tyrosine Residue. J Biol Chem 2010;285(34):26506–26518 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Brownlie RJ, Zamoyska R, Salmond RJ. Regulation of autoimmune and anti-tumour T-cell responses by PTPN22. Immunology 2018;154(3):377–382 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; *succinct review that includes early work on PTPN22 and possible immunotherapy role.

- 40.Stanford SM, Bottini N. PTPN22: The archetypal non-HLA autoimmunity gene. Nat Rev Rheumatol 2014;10(10):602–11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zheng J, Ibrahim S, Petersen F, et al. Meta-analysis reveals an association of PTPN22 C1858T with autoimmune diseases, which depends on the localization of the affected tissue. Genes Immun 2012;13(8):641–652 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Vang T, Congia M, Macis MD, et al. Autoimmune-associated lymphoid tyrosine phosphatase is a gain-of-function variant. Nat Genet 2005;37(12):1317–1319 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rieck M, Arechiga A, Onengut-Gumuscu S, et al. Genetic Variation in PTPN22 Corresponds to Altered Function of T and B Lymphocytes. J Immunol 2007;179(7):4704–4710 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Aarnisalo J, Treszl A, Svec P, et al. Reduced CD4+T cell activation in children with type 1 diabetes carrying the PTPN22/Lyp 620Trp variant. J Autoimmun 2008;31(1):13–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Cao Y, Yang J, Colby K, et al. High Basal Activity of the PTPN22 Gain-of-Function Variant Blunts Leukocyte Responsiveness Negatively Affecting IL-10 Production in ANCA Vasculitis. PLoS One 2012;7(8):E42783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Vang T, Landskron J, Viken MK, et al. The autoimmune-predisposing variant of lymphoid tyrosine phosphatase favors T helper 1 responses. Hum Immunol 2013;74(5):574–585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Burn GL, Cornish GH, Potrzebowska K, et al. Super-resolution imaging of the cytoplasmic phosphatase PTPN22 links integrin-mediated adhesion with autoimmunity. Sci Signal 2016;9(448):ra99 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lefvert AK, Zhao Y, Ramanujam R, et al. PTPN22 R620W promotes production of anti-AChR autoantibodies and IL-2 in myasthenia gravis. J Neuroimmunol 2008;197(2):110–113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zikherman J, Hermiston M, Steiner D, et al. PTPN22 Deficiency Cooperates with the CD45 E613R Allele to Break Tolerance on a Non-Autoimmune Background. J Immunol 2009;182(7):4093–4106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zhang J, Zahir N, Jiang Q, et al. The autoimmune disease–associated PTPN22 variant promotes calpain-mediated Lyp/Pep degradation associated with lymphocyte and dendritic cell hyperresponsiveness. Nat Genet 2011;43(9):902–907 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Dai X, James RG, Habib T, et al. A disease-associated PTPN22 variant promotes systemic autoimmunity in murine models. J Clin Invest 2013;123(5):2024–2036 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Brownlie RJ, Wright D, Zamoyska R, et al. Deletion of PTPN22 improves effector and memory CD8+ T cell responses to tumors. JCI Insight. 2019;5(16):E127847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; **an early study showing effects of PTPN22 deletion on tumor clearance.

- 53.Brownlie RJ, Garcia C, Ravasz M, et al. Resistance to TGFβ suppression and improved anti-tumor responses in CD8+ T cells lacking PTPN22. Nat Commun 2017;8(1):1343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; **establishes ability of PTPN22-deficiency to counter suppression of T cells by TGFβ

- 54.Cubas R, Khan Z, Gong Q, et al. Autoimmunity linked protein phosphatase PTPN22 as a target for cancer immunotherapy. J Immunother Cancer 2020;8(2):E001439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; **first reported study assessing targeting PTPN22 in combination with immunotherapy

- 55.Orozco RC, Marquardt K, Mowen K, et al. Title: Pro-autoimmune allele of tyrosine phosphatase, PTPN22, enhances tumor immunity. J Immunol 2021;207(6):1662–1671 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; *recent study showing autoimmune-associated PTPN22 R620W enhances T cell response to tumors

- 56.Perry DJ, Peters LD, Lakshmi PS, et al. Overexpression of the PTPN22 Autoimmune Risk Variant LYP-620W Fails to Restrain Human CD4 + T Cell Activation. J Immunol 2021;207(3):849–859 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Chang HH, Tai TS, Lu B, et al. PTPN22.6, a Dominant Negative Isoform of PTPN22 and Potential Biomarker of Rheumatoid Arthritis. PLoS One 2012;7(3):E33067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ho WJ, Croessmann S, Lin J, et al. Systemic inhibition of PTPN22 augments anticancer immunity. J Clin Invest 2021;131(17):E146950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; **revealed PTPN22 to be a systemically druggable immunotherapy target

- 59.Maueröder C, Munoz LE, Chaurio RA, et al. Tumor immunotherapy: Lessons from autoimmunity. Front Immunol 2014;5:212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Joseph CG, Darrah E, Shah AA, et al. Association of the autoimmune disease scleroderma with an immunologic response to cancer. Science 2014;343(6167):152–157 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Rosenberg SA. Entering the mainstream of cancer treatment. Nat Rev Clin Oncol 2014;11(11):630–632 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; *informative review on contemporary cancer immunotherapy strategies

- 62.Pardoll DM. The blockade of immune checkpoints in cancer immunotherapy. Nat Rev Cancer 2012;12(4):252–264 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Ribas A, Wolchok JD. Cancer immunotherapy using checkpoint blockade. Science 2018;359(6382):1350–1355 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Fesnak AD, June CH, Levine BL. Engineered T cells: the promise and challenges of cancer immunotherapy. Nat Rev Cancer 2016;16(9):566–581 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; *highlights successes and limitations of current cancer immunotherapies.

- 65.Thomas DA, Massagué J. TGF-beta directly targets cytotoxic T cell functions during tumor evasion of immune surveillance. Cancer Cell 2005;8:369–(5):369–380 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Gorelink L, Flavell RA. Immune-mediated eradication of tumors through the blockade of transforming growth factor-β signaling in T cells. Nature Med 2001;7(10):1118–1122 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Gattinoni L, Klebanoff CA, Palmer DC, et al. Acquisition of full effector function in vitro paradoxically impairs the in vivo antitumor efficacy of adoptively transferred CD8+ T cells. J Clin Invest 2005;115(6):1616–1626 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Klebanoff CA, Gattinoni L, Torabi-Parizi P, et al. Central memory self/tumor-reactive CD8+ T cells confer superior antitumor immunity compared with effector memory T cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2005;102(27):9571–9576 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Maine CJ, Teijaro JR, Marquardt K, et al. PTPN22 contributes to exhaustion of T lymphocytes during chronic viral infection. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2016;113(46):E7231–E7239 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Jofra T, Galvani G, Kuka M, et al. Extrinsic protein tyrosine phosphatase non-receptor 22 signals contribute to CD8 T cell exhaustion and promote persistence of chronic lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus infection. Front Immunol 2017;8:811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Eggermont AMM, Kicinski M, Blank CU, et al. Association Between Immune-Related Adverse Events and Recurrence-Free Survival Among Patients With Stage III Melanoma Randomized to Receive Pembrolizumab or Placebo: A Secondary Analysis of a Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Oncol 2020;6(4):519–527 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.June CH, Warshauer JT, Bluestone JA. Is autoimmunity the Achilles’ heel of cancer immunotherapy? Nat Med 2017;23(5):540–547 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Liang X, Fu H, Xiao P, et al. Design, synthesis and biological evaluation of imidazolidine-2,4-dione and 2-thioxothiazolidin-4-one derivatives as lymphoid-specific tyrosine phosphatase inhibitors. Bioorg Chem 2020;103:104124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; *provides practical example of scaffold hopping in PTPN22 inhibitor development.

- 74.Karver MR, Krishnamurthy D, Kulkarni RA, et al. Identifying Potent, Selective Protein Tyrosine Phosphatase Inhibitors from a Library of Au(I) Complexes. J Med Chem 2009;52(21):6912–6918 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; *illustrates discovery of gold-complexing small molecule PTPN22 inhibitor

- 75.Wu S, Bottini M, Rickert RC, et al. In Silico Screening for PTPN22 Inhibitors: Active Hits from an Inactive Phosphatase Conformation. ChemMedChem 2009;4(3):440–444 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Xie Y, Liu Y, Gong G, et al. Discovery of a novel submicromolar inhibitor of the lymphoid specific tyrosine phosphatase. Bioorg Med Chem Lett 2008;18(9):2840–2844 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Ahmed VF, Bottini N, Barrios AM. Covalent inhibition of the lymphoid tyrosine phosphatase. ChemMedChem 2014;9(2):296–299 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Du J, Qiao Y, Sun L, et al. Lymphoid-Specific Tyrosine Phosphatase (Lyp): A Potential Drug Target For Treatment of Autoimmune Diseases. Curr Drug Targets 2014;15(3):335–346 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Lai AC, Crews CM. Induced protein degradation: an emerging drug discovery paradigm. Nat Rev Drug Discov 2017;16(2):101–114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; *an excellent review on emerging protein degradation strategies.

- 80.Lu Y, Xue J, Deng T, et al. Safety and feasibility of CRISPR-edited T cells in patients with refractory non-small-cell lung cancer. Nat Med 2020;26(5):732–740 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Stadtmauer EA, Fraietta JA, Davis MM, et al. CRISPR-engineered T cells in patients with refractory cancer. Science 2020;28:367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Malissen B, Srikanth S, Valitutti S, et al. Crispr/Cas Mediated Deletion of PTPN22 in Jurkat T Cells Enhances TCR Signaling and Production of IL-2. Front Immunol 2018;9:2595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Du X, Darcy PK, Wiede F, et al. Targeting Protein Tyrosine Phosphatase 22 Does Not Enhance the Efficacy of Chimeric Antigen Receptor T Cells in Solid Tumors. Mol Cell Biol 2022;42(3):e0044921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Perri V, Pellegrino M, Ceccacci F, et al. Use of short interfering RNA delivered by cationic liposomes to enable efficient down-regulation of PTPN22 gene in human T lymphocytes. PLoS One 2017;12(4):e0175784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]