Abstract

Background & Aims:

Substantial heterogeneity in terminology used for eosinophilic gastrointestinal diseases (EGID), particularly the catchall term “eosinophilic gastroenteritis”, limits clinical and research advances. We aimed to achieve an international consensus for standardized EGID nomenclature.

Methods:

This consensus process utilized Delphi methodology. An initial naming framework was proposed and refined in iterative fashion, then assessed in a first round of Delphi voting. Results were discussed in two consensus meetings, the framework was updated, and re-assessed in a second Delphi vote, with a 70% threshold set for agreement.

Results:

Of 91 experts participating, 85 (93%) completed the first and 82 (90%) completed the second Delphi surveys. Consensus was reached on all but two statements. “EGID” was the preferred umbrella term for disorders of GI tract eosinophilic inflammation in the absence of secondary causes (100% agreement). Involved GI tract segments will be named specifically and use an “Eo” abbreviation convention: eosinophilic gastritis (now abbreviated EoG), eosinophilic enteritis (EoN), and eosinophilic colitis (EoC). The term “eosinophilic gastroenteritis” is no longer preferred as the overall name (96% agreement). When >2 GI tract areas are involved, the name should reflect all of the involved areas.

Conclusions:

This international process resulted in consensus for updated EGID nomenclature for both clinical and research use. EGID will be the umbrella term rather than “eosinophilic gastroenteritis”, and specific naming conventions by location of GI tract involvement are recommended. As more data are developed, this framework can be updated to reflect best practices and the underlying science.

Keywords: eosinophilic gastrointestinal disease, eosinophilic gastroenteritis, Delphi, nomenclature, classification

Introduction

Eosinophilic gastrointestinal diseases (EGIDs) are chronic, immune-mediated disorders characterized clinically by GI symptoms and histologically by a pathologic increase in eosinophil-predominant inflammation in specific regions of the GI tract, in the absence of secondary causes of eosinophilia.1, 2 The best known of these is eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE),3–5 but the non-EoE EGIDs are now the subject of intensive study due to increased clinical awareness of these conditions. Non-EoE EGIDs can involve the stomach, small bowel, and colon, either individually or in any combination of segments, and can also vary in the depth of involvement of the GI tract layers. Recent investigations have focused on understanding the clinical presentation, epidemiology, natural history, pathogenesis, and effective treatments.6–22

At present, no guidelines exist for diagnosis or treatment of the non-EoE EGIDs, but efforts are actively underway to develop these. As this guideline process started, there was substantial confusion related to EGID terminology, particularly pertaining to the catchall term “eosinophilic gastroenteritis”. There has been variable use of this term in both clinical settings and research studies, with ambiguity and heterogeneity in its definition.8, 13, 23–26 Over many years, the phrase “eosinophilic gastroenteritis” has been used to indicate different sites of involvement including stomach alone, small bowel alone, stomach and small bowel, stomach or small bowel, or involvement anywhere along the GI tract.

This non-standardized use of nomenclature highlighted a need for a common language for non-EoE eosinophilic GI disease names, not just for clinical practice but also for the consistent data collection required for research to continue to advance the field. Therefore, the aim of this effort was to achieve an international consensus for consistent EGID nomenclature.

Methods

Overview and principles

This was an iterative and inclusive process with formalized feedback utilizing standard Delphi methods.27 A four-person steering group (ESD, NG, GTF, SSA) first reviewed the literature and developed several potential nomenclature systems, which were then shared and refined amongst an expanded focus group. Additional feedback was solicited from members of the Consortium of Eosinophilic Gastrointestinal Disease Researchers (CEGIR),28 as well as from members outside of this group. Based on the feedback, an initial nomenclature framework was proposed.

A number of principles guided the first part of the development process. First, when terminology was not ambiguous, the goal was to retain as much of the existing nomenclature as possible. This was to minimize confusion amongst clinicians, researchers, and patients and to retain existing International Classification of Diseases (ICD) codes. Second, was to strongly consider the removal of the term “eosinophilic gastroenteritis” from the framework, given the variability in its use. Third, was to create a basic level of nomenclature that would be intuitive and useful for clinical practice. Fourth, was to include a second tier of more detailed nomenclature that could be utilized for research purposes, with a focus on granularity in naming since terms can always be combined as future information is gained, but cannot be split. Fifth, was to solicit and receive feedback during the process from stakeholders, including patient advocacy groups, regulatory authorities, researchers, and clinicians. Sixth, was to move forward with the recognition that the framework developed would be a starting point and expected to change in the future, as informed by emerging data.

Delphi 1

After the framework had been established, the next step was the first Delphi round of questions. An international and multidisciplinary group of adult and pediatric clinicians and researchers with experience in EGIDs, esophageal disorders, immunology, functional disorders, and other areas, spanning specialities of gastroenterology, allergy, pathology, basic and translational science, and epidemiology, was recruited to complete a 42 question online survey distributed using the Qualtrics platform. Questions focused on use of the term “eosinophilic gastroenteritis” and other possible nomenclature options. A figure of the framework was presented at the beginning of the survey, and respondents were asked to rate their level of agreement to a series of statements on a five-point scale: strongly disagree, disagree, neither agree nor disagree, agree, and strongly agree. Free text comments were also allowed. Summary statistics for the responses were calculated and a level of agreement of 70% (the sum of “agree” and “strongly agree”) was set a priori.

Consensus meetings

After the initial Delphi responses were analyzed, all respondents participated in one of two scheduled consensus meetings in May, 2021. Two meetings were scheduled to accommodate the large number of participants who were located on five continents and because an in-person meeting was not possible due to the COVID-19 pandemic. These meetings were approached in identical fashion and conducted via a video conferencing platform with a chat interface. Data were reviewed and then the discussion focused on areas of disagreement, proposed new terminology, the role of the term “eosinophilic gastroenteritis”, and how to approach naming eosinophilic disease in the small bowel. Active participation was sought from all participants, and comments in the chat were recorded and reviewed. In addition, preliminary results were shared with stakeholders, including patient advocacy groups, industry representatives, and representatives from the Food and Drug Administration during the Gastroenterology Regulatory Endpoints and the Advancement of Therapeutics VI (GREAT VI) Workshop on EGIDs beyond EoE (July, 2021).29

Delphi 2

All feedback from the consensus meetings and additional comments received were incorporated into an updated framework. This was again done in an iterative fashion, first with the steering group and then with the extended focus group members. After this, a second round of Delphi questions was developed and distributed to the same large international group that completed the first Delphi round. There were 29 questions, again distributed in an online survey, focusing on the updated framework. Respondents were asked only whether they agreed or disagreed with each of the statements (two-point scale without a “neutral” option). Summary statistics for the responses were calculated and a level of agreement of 70% was set a priori.

Results

Demographics and variability in terminology use

Of the 91 experts invited to participate, 85 (93%) completed the first Delphi survey. There were 32 women (38%) and 53 men (62%), with a median time in practice of 21 years (interquartile range: 9–30). Nearly half (48%) of participants saw children and/or adolescents in practice, 12% saw adolescents and adults, 18% saw adults only, 14% saw patients of all ages, and 8% did not see patients. Practice settings were largely academic or university-based (91%), and 53% saw three or more non-EoE EGID patients per month (Table 1).

Table 1:

Characteristics of EGID nomenclature Delphi process (n=85)

| n (%), or median | |

|---|---|

| Sex | |

| Female | 32 (38) |

| Male | 53 (62) |

| Time in practice (median years, IQR, range) | 21 (9–30); range: 1–44 |

| Specialty | |

| Gastroenterology | 60 (70) |

| Allergy/Immunology | 15 (18) |

| Pathology | 5 (6) |

| Other | 5 (6) |

| Type of patients seen | |

| Children and/or adolescents | 41 (48) |

| Adolescents and adults | 10 (12) |

| Adults | 15 (18) |

| All ages | 12 (14) |

| Do not see patients | 7 (8) |

| Practice setting | |

| Academic/university | 77 (91) |

| Private/community practice | 4 (5) |

| Not practicing | 3 (3) |

| Industry | 1 (1) |

| Location | |

| North America | 49 (58) |

| South America | 2 (2) |

| Europe | 24 (28) |

| Asia | 6 (7) |

| Australia | 4 (5) |

| Non-EoE EGID patients seen per month | |

| <3 | 33 (47) |

| 3–5 | 13 (19) |

| 5–10 | 9 (13) |

| >10 | 15 (21) |

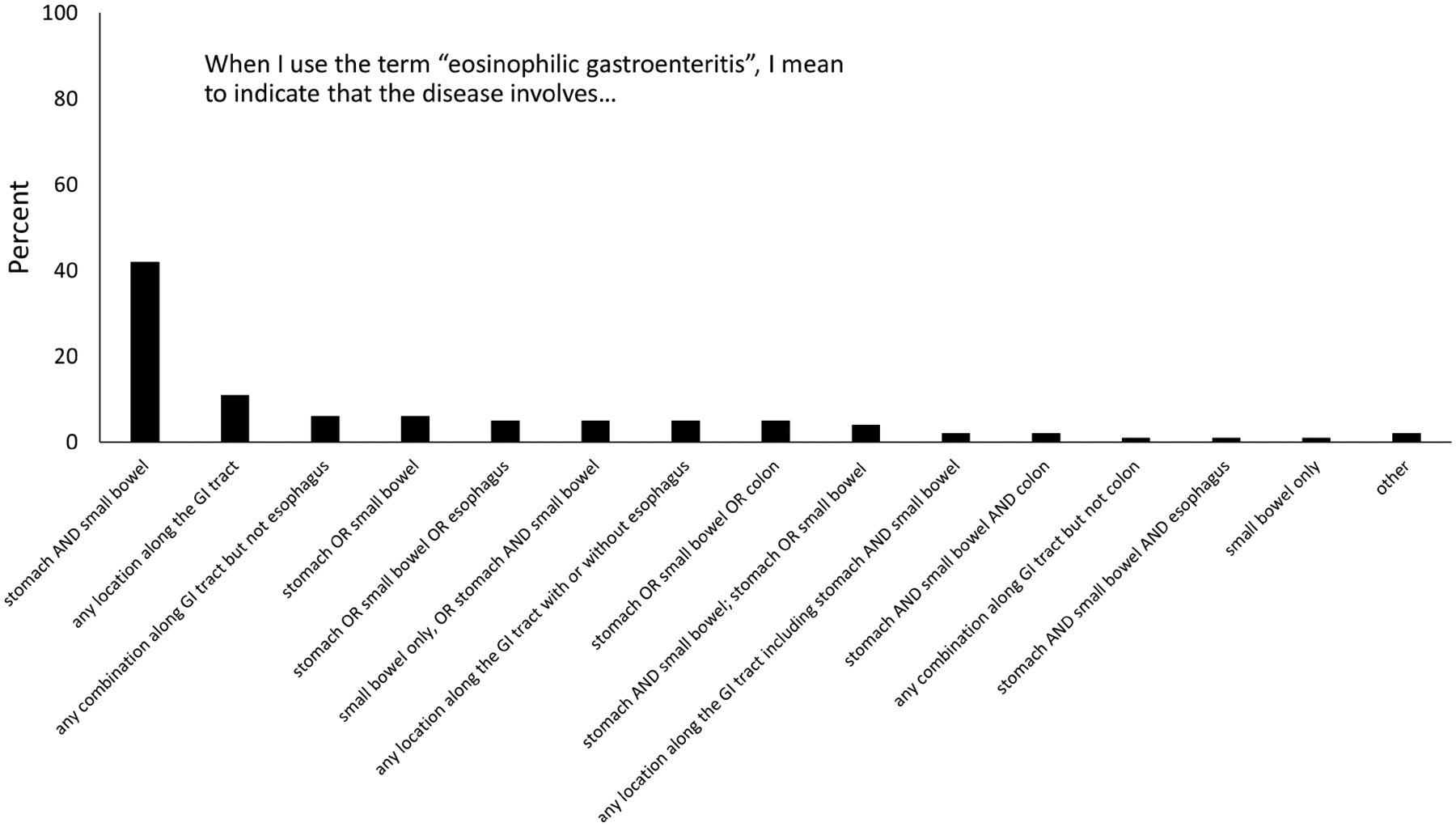

To gauge how participants currently viewed terminology, they were asked the question: “When I use the term “eosinophilic gastroenteritis”, I mean to indicate that the disease involves (please check all of the following that apply)”. There was no majority consensus answer to this question. The two most common answers were “stomach AND small bowel”, reported by 36 (42%), and “any location along the GI tract, reported by 11 (13%)”. However, there was substantial variability in responses, with more than 13 other definitions for “eosinophilic gastroenteritis” provided, representing a range of different locations along the GI tract (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Variability in responses for how the term “eosinophilic gastroenteritis” is used to reflect different areas of involvement in the GI tract.

Delphi 1 results and consensus meetings

Full data on the initial Delphi results are presented in Supplemental Table 1. There was strong agreement in the first round of the Delphi process and in the consensus meetings that the umbrella term for disorders of GI tract eosinophilic inflammation in the absence of secondary causes should be “eosinophilic gastrointestinal disease” (96% either agreed or strongly agreed), and that when an EGID involves only the esophagus, the name should remain EoE (97% either agreed or strongly agreed). There was also strong agreement that when an EGID involves only the stomach or colon, the name should be eosinophilic gastritis or eosinophilic colitis, respectively (95% agreed or strongly agreed for both).

There was no consensus on whether the term “eosinophilic gastroenteritis” should be removed from an EGID nomenclature system (10% strongly agree, 25% agree, 25% neutral, 30% disagree, 11% strongly disagree). In the initial survey comments and in the discussions during the meetings, reasons for removing the term were related to variability in use, unclear definition or meaning, and limitations related to an ability to know whether the stomach or bowel (or both) were involved. Reasons for retaining the term included its historical nature and use, its ongoing use in current research studies and protocols, and the need to potentially redefine the term (stomach and small bowel involvement only) but not use it as an umbrella term any longer. This last option carried weight and began to generate consensus.

During the Delphi 1 process, consensus was also not reached on what to name small bowel involvement alone, and there was 61% agreement, 19% neutral, and 21% disagreement with the term “eosinophilic pan-enteritis”. In the comments and discussion, there was debate as to whether specifying all parts of small bowel involvement (e.g. duodenum vs jejunum vs ileum) was necessary or even practical, given that assessment of the mid/distal small bowel may not be clinically indicated and performing deep enteroscopy and/or video capsule endoscopy may not be possible at all centers. Nevertheless, there was consensus on naming of eosinophilic duodenitis (75% strongly agreeing or agreeing, 21% neutral, 11% disagreeing). There was also debate about whether to include depth of wall layer involvement, EGID complications, or uninvestigated areas of the GI tract in the nomenclature framework (Supplemental Table 1).

Delphi 2 results

There were 82 responses from the 91 participants for the Delphi round 2 survey (90%), and overall consensus was reached on all statements from the updated framework (based on input from the Delphi round 1 and consensus meetings) with the exception of two statements (Table 2). There was universal (100%) consensus on using the umbrella term EGID for disorders of GI tract eosinophilic inflammation in the absence of secondary causes, as well as the names eosinophilic gastritis and eosinophilic colitis. There was 95% agreement to naming an EGID involving the small intestine as “eosinophilic enteritis”, and 94% agreement that it was desirable, but not required, to name specific locations of small bowel involvement, when known. There was also consensus for naming the individual segments of the small bowel (i.e. eosinophilic duodenitis).

Table 2:

Agreement data from round 2 of the Delphi voting process (n=82)

| Agree (n, %) | Disagree (n, %) | |

|---|---|---|

| The umbrella term for disorders of GI tract eosinophilic inflammation in the absence of secondary causes should be “eosinophilic gastrointestinal disease” (EGID) | 82 (100) | 0 (0) |

| When an EGID involves the esophagus, the name should remain “eosinophilic esophagitis” (EoE) | 80 (98) | 2 (2) |

| When an EGID involves the stomach, the name should be “eosinophilic gastritis” | 82 (100) | 0 (0) |

| When an EGID involves the colon, the name should be “eosinophilic colitis” | 82 (100) | 0 (0) |

| When an EGID involves the small intestine, the general name should be “eosinophilic enteritis” | 78 (95) | 4 (5) |

| For the abbreviation for eosinophilic gastritis, should it be “EG” or “EoG”? | EoG: 72 (88) | EG:10 (12) |

| For the abbreviation for eosinophilic colitis, should it be “EC” or “EoC”? | EoC: 72 (88) | EC: 10 (12) |

| For the abbreviation for eosinophilic enteritis, should it be “EEN” or “EoN” | EoN 65 (79) | EEN: 17 (21) |

| It is desirable, but not required, to name specific locations of small bowel involvement, if these are known. | 77 (94) | 5 (6) |

| When an EGID involves the duodenum, the name should be “eosinophilic duodenitis” | 76 (93) | 6 (7) |

| The abbreviation for eosinophilic duodenitis should be “EoD” | 75 (91) | 7 (9) |

| When an EGID involves the jejunum, the name should be “eosinophilic jejunitis” | 76 (94) | 6 (7) |

| The abbreviation for eosinophilic jejunitis should be “EoJ” | 73 (89) | 9 (11) |

| When an EGID involves the ileum, the name should be “eosinophilic ileitis” | 77 (94) | 5 (6) |

| The abbreviation for eosinophilic ileitis should be “Eol” | 74 (90) | 8 (10) |

| The term “eosinophilic gastroenteritis” should be redefined and only used to indicate gastric AND small bowel involvement | 68 (83) | 14 (17) |

| The term “eosinophilic gastroenteritis” will no longer be used as the umbrella term for EGIDs | 79 (96) | 3 (4) |

| For EGIDs that involve the stomach and/or small bowel and/or the colon, and ALSO the esophagus, the term to indicate this should be “with esophageal involvement” | 50 (61) | 32 (39) |

| When more than two GI tract areas (outside of the esophagus) are involved, the name should reflect the involved areas (ie stomach + duodenum = eosinophilic gastritis and duodenitis; duodenum + colon = eosinophilic duodenitis and colitis; etc) | 79 (96) | 3 (4) |

| The GI wall layer of involvement (or if this is unknown) should be noted | 65 (79) | 17 (21) |

| Complications of EGIDs (for example, protein-losing enteropathy, ascites, or numerous others) should be noted | 67 (82) | 15 (18) |

| Any areas of the GI tract that are not investigated or have unknown involvement should be noted | 53 (65) | 29 (35) |

For abbreviations, agreement was reached to have an “Eo” naming convention, consistent with what is already used for EoE. Therefore eosinophilic gastritis would be EoG, eosinophilic duodenitis would be EoD, and eosinophilic colitis would be EoC. There was debate around how to abbreviate small bowel involvement, but ultimately 79% agreed with “EoN”, indicating Eosinophilic eNteritis.

During the Delphi 2 process, the term “eosinophilic gastroenteritis” was deemphasized and will no longer be the preferred umbrella term for EGIDs (96% agreement). When used, it should only be used when both the stomach and the small bowel are involved (83% agreement). There was also consensus that when more than two GI tract areas (outside of the esophagus) are involved, the name should reflect the involved areas (96% agreement) (Table 2).

The first topic where consensus was not reached related to overlapping esophageal involvement. Only 61% agreed with the statement that for EGIDs that involve the stomach and/or small bowel and/or the colon, and ALSO the esophagus, the term to indicate this should be “with esophageal involvement”. The second topic was related to whether areas of the GI tract that were not investigated or had unknown involvement should be specified in the nomenclature framework (65% agreement).

Discussion

Research related to EGIDs is rapidly advancing. However, the field of non-EoE EGIDs is in a position similar to where EoE was in the early 2000s, without diagnostic or management guidelines, and with a literature that can be difficult to interpret based on different disease definitions and terminologies used.30 In particular, the term “eosinophilic gastroenteritis” has been confusing, as it has often been used to represent any type of eosinophilic GI infiltration, not just stomach and small bowel. In that context, our large, international, and multidisciplinary group came together to conduct a Delphi process to standardize EGID nomenclature. This step, while seemingly rudimentary, was essential to inform the guideline efforts that are now underway.

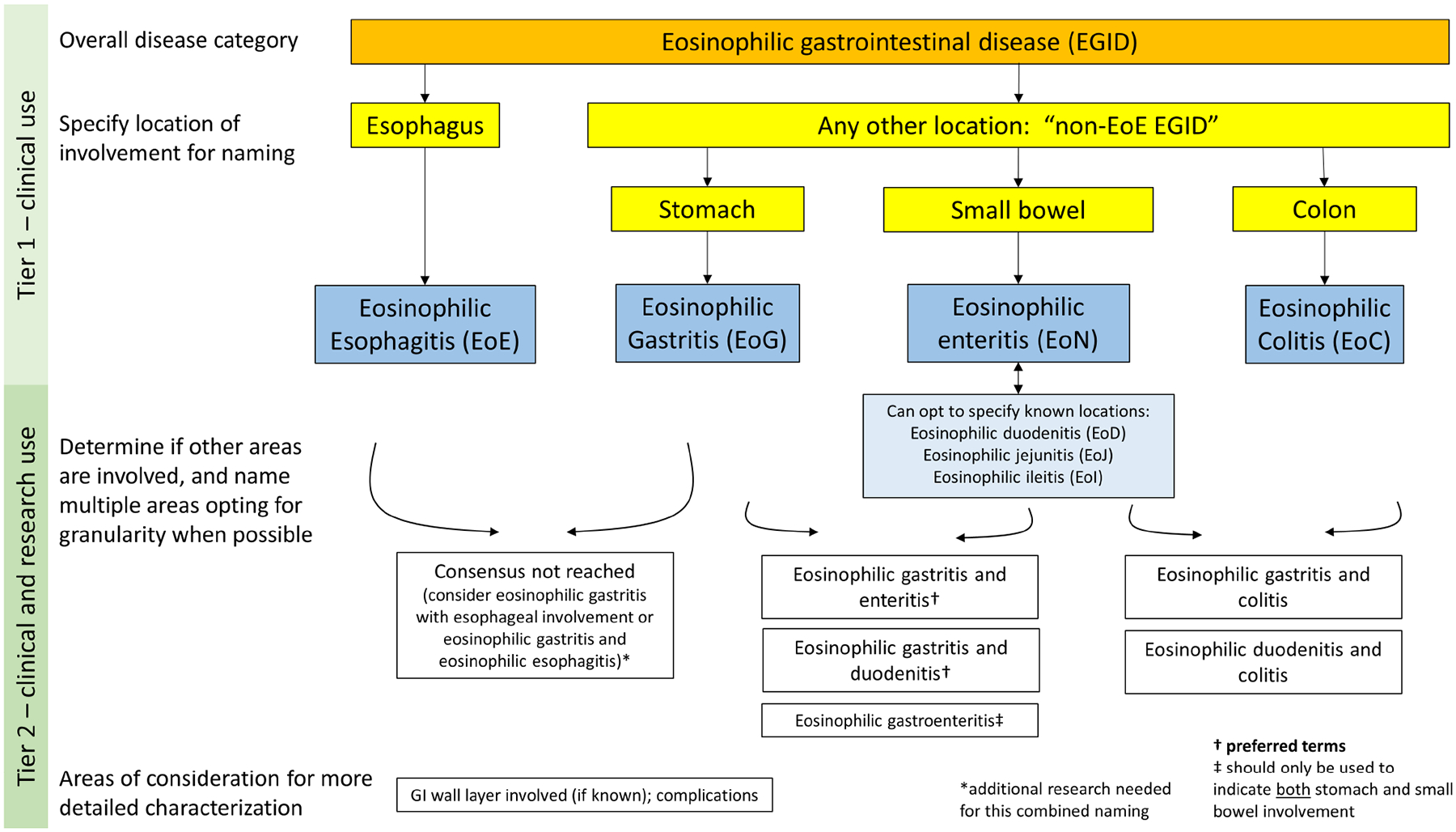

The results from this iterative and collaborative process showed that even amongst this group of experts, the term “eosinophilic gastroenteritis” was variably used, and agreement to redefine and deemphasize this term was reached. The new framework for EGID nomenclature that resulted from this Delphi process is presented in Figure 2. “EGID” should now be used as the umbrella term for diseases of the GI tract with pathologic eosinophilic infiltration in the absence of secondary causes. In the first tier of nomenclature that will be used routinely in clinical practice, esophageal involvement alone remains EoE. Any other location of involvement can be termed a “non-EoE EGID”. Naming is then by location of inflammation, with the stomach being termed eosinophilic gastritis (EoG), small bowel termed eosinophilic enteritis (EoN), and colon termed eosinophilic colitis (EoC). In the second tier of nomenclature, which can be used clinically but should be used for research, there is an emphasis on further granularity with naming, in particular when there is small bowel involvement and when there are multiple non-esophageal locations involved. For example, stomach and small bowel involvement should be termed eosinophilic gastritis and enteritis, and stomach and duodenal involvement should be termed eosinophilic gastritis and duodenitis. Because there was not consensus when the esophagus is also involved, this can either be termed “with esophageal involvement” or “EoE”, but with the understanding that by current diagnostic criteria, EoE is isolated to the esophagus.3 Additionally, the GI wall layer of involvement, if known, should be noted, along with complications that may be present. These can include protein-losing enteropathy, ascites, anemia, strictures, ulcers, perforations, or others.

Figure 2.

Consensus nomenclature framework for eosinophilic gastrointestinal diseases (EGIDs). Note that for naming multiple involved GI segments, representative examples are provided but not all possible combinations are listed.

While this process yielded nearly universal agreement on almost every facet of EGID nomenclature, there were exceptions that were vigorously debated, mostly concerning how to address patients with multiple areas of the GI tract involved. EGIDs with multiple areas of involvement are challenging since there are few data addressing whether there is a disease spectrum with a shared pathogenesis or not. In this context, many participants felt it was important to identify a “primary” location of the EGID named after taking into account the predominant symptoms, endoscopic features, and complications, not simply just the histologic findings. Therefore, a patient with gastric, small bowel, and colonic involvement, but with protein-losing enteropathy, malabsorption, diarrhea, and small bowel strictures, would be classified primarily as EoN. If this patient instead had anorexia, weight loss, abdominal pain, and gastric ulceration with pyloric stenosis, the classification would primarily be EoG. A similar issue was raised when the esophagus was involved. Some patients with esophageal and gastric involvement, for example, may have primarily “EoE-like” symptoms and findings (with dysphagia, esophageal stricturing, and need for dilation) but also have superimposed gastric symptoms, while some may have minimal dysphagia and heartburn, but abdominal pain and gastric ulceration predominate. The former patient might be classified as “EoE and EoG”, while the latter may be better termed “EoG with esophageal involvement”. However, it was acknowledged that this is likely a part of the nomenclature framework that will evolve in the future as pertinent data become available. Another major area of emphasis was that the clinical picture, and not the nomenclature, should drive the clinically-indicated evaluation and treatment. Therefore, while upper endoscopy is typically indicated in most cases of chronic GI symptoms, colonoscopy and additional deep enteroscopy or imaging techniques are not required in all patients. In particular, there was a strong desire to keep testing to what is clinically relevant and not over-investigate symptoms once a diagnosis is made, particularly in children. There is no need to “stage” entire GI tract or investigate areas of the bowel that are not responsible for symptoms. Further discussion of this topic, however, was beyond the scope of the nomenclature effort and will be more thoroughly addressed in diagnostic guidelines which are under development.

There are several limitations to acknowledge with the current consensus approach. First, the participants tended to be from academic or university settings, and therefore were not representative of all practitioners. However, an overriding goal of this process was to have a simplified approach in a “first tier” of nomenclature than can be adopted by all clinicians, and this was accomplished with the EGID umbrella term, the EoE vs non-EoE EGID designation, and the naming conventions for the gastric, small bowel, and colonic locations. We added a more complex “second tier” to be used in a research setting, or when a clinician would like to provide more details and granularity for better patient characterization and follow-up. This framework is analogous to a general gastroenterologist using the term ileocolonic Crohn’s in a patient with inflammatory bowel disease, whereas a researcher would use the full Montreal classification system.31 Second, this nomenclature is for luminal GI disorders, so does not currently apply to eosinophilic gallbladder, liver, or pancreatic diseases. Last, the small bowel nomenclature remains challenging. It may be either too general (enteritis), too specific (jejunitis), or limited (duodenitis, without noting additional small bowel extent). However, the current terms, designations, and conventions for naming multiple segments provides a reasonable and standardized starting point for the field.

A benefit of the EGID nomenclature process is that these identified limitations suggest clear and immediate directions for research. The debate about whether to use “esophageal involvement” or “EoE” can be addressed when molecular and pathogenic data are compared between patients with only esophageal involvement and patients with esophageal and “lower” involvement. If molecular profiles pathogenic mechanisms are the same in each case, then names can be the same; if the features, treatment, or prognosis are distinct, then the naming convention can also be different. Similarly, it remains to be investigated whether patients with gastric and small bowel involvement are the same as those with gastric alone or small bowel alone, though some data on clinical presentation and treatment response related to this question are beginning to emerge.12, 20–22 Naming precision will also be helpful for assessing and contextualizing therapeutic response. A final aspect to consider is how this nomenclature will ultimately mesh with the current ICD coding system. Current EGID ICD-10 codes include eosinophilic esophagitis (K20.0), eosinophilic gastritis or gastroenteritis (K52.81), and eosinophilic colitis (K52.82). If ongoing research supports the currently proposed updated nomenclature framework, then ICD coding will likely need to be updated to reflect this as well.

In conclusion, this international consensus process has resulted in updated EGID nomenclature that should be used for both clinical and research purposes. EGID will be the umbrella term for diseases of eosinophilic infiltration of the GI tract, and the term “eosinophilic gastroenteritis” will no longer be used in this role, and will ideally be replaced in favor of more specific naming conventions. If the term “eosinophilic gastroenteritis” is used, it should only be for the times that both stomach and small bowel are involved. The iterative and collaborative process led to agreement on nearly all aspects of the proposed nomenclature framework, and has identified future research directions. It is expected that as more data are collected, the nomenclature will again be updated to reflect best practices and the underlying pathogenesis of these disorders.

Supplementary Material

What you need to know.

Background:

There is substantial variability in terminology for naming eosinophilic gastrointestinal diseases (EGIDs), and there has been heterogenous use of the catchall term “eosinophilic gastroenteritis” in both clinical settings and research studies.

Findings:

This Delphi process, in which 91 experts participated, resulted in international consensus for a new nomenclature framework for EGIDs. “EGID” should now be used as the umbrella term for diseases of the GI tract with pathologic eosinophilic infiltration in the absence of secondary causes. Involvement of individual GI tract locations should be named specifically, and an “Eo” abbreviation convention should be used: EoG for eosinophilc gastritis, EoN for eosinophilic enteritis, and EoC for eosinophilic colitis; eosinophilic esophagitis remains EoE. The term “eosinophilic gastroenteritis” will no longer be used as an umbrella name.

Implications for patient care:

Patients, clinicians, and researchers should use this new nomenclature. The first tier of nomenclature can be used routinely in clinical practice, while the second tier can be used clinically and in research. This more specific naming paradigm will allow more precise clinical phenotyping, which will inform guideline development and future research directions.

Acknowledgements:

We gratefully acknowledge the input and review from the following patient advocacy groups and their representatives: American Partnership for Eosinophilic Disorders (APFED; Mary Jo Strobel), AusEE Inc (Sarah Gray), Campaign Urging Research for Eosinophilic Disease (CURED; Ellyn Kodroff), Eosinophilic Family Coalition (EFC; Amy Zicarelli), and EosNetwork (Amanda Cordell). We also thank Rhona Jackson for her administrative assistance in coordinating this process and manuscript submission.

Funding:

CEGIR (U54 AI117804) is part of the Rare Disease Clinical Research Network (RDCRN), an initiative of the Office of Rare Diseases Research (ORDR), NCATS, and is funded through collaboration between NIAID, NIDDK, and NCATS. CEGIR is also supported by patient advocacy groups including American Partnership for Eosinophilic Disorders (APFED), Campaign Urging Research for Eosinophilic Diseases (CURED), and Eosinophilic Family Coalition (EFC). As a member of the RDCRN, CEGIR is also supported by its Data Management and Coordinating Center (DMCC) (U2CTR002818).

Disclosures

Dellon – Research funding: Adare/Ellodi, Allakos, Arena, AstraZeneca, GSK, Meritage, Miraca, Nutricia, Celgene/Receptos/BMS, Regeneron, Shire/Takeda; Consultant: Abbott, Abbvie, Adare/Ellodi, Aimmune, Allakos, Amgen, Arena, AstraZeneca, Avir, Biorasi, Calypso, Celgene/Receptos/BMS, Celldex, Eli Lilly, EsoCap, GSK, Gossamer Bio, InveniAI, Landos, LucidDx, Morphic, Nutricia, Parexel/Calyx, Phathom, Regeneron, Revolo, Robarts/Alimentiv, Salix, Sanofi, Shire/Takeda, Target RWE; Educational grant: Allakos, Banner, Holoclara

Gonsalves – Consultant: Allakos, Astra-Zeneca, Knopp, Abbvie, Regeneron-Sanofi, Nutricia, Speakers Bureau: Takeda, Royalties; Up-to-Date

Abonia – Consultant: Takeda

Alexander – Consultant: Lucid Technologies; Research funding: Shire/Takeda, Adair, Regeneron; Financial Interest: Meritage Pharmacia

Arva – None

Atkins – None

Attwood – Consultant for Dr Falk Pharma, Eso-Cap, AstraZeneca and Regeneron/Sanofi, and has received speaker fees from Medtronic, Vifor Pharma and Rafa Pharma

Auth – Investigator fees from Dr Falk Pharma, and educational grants from Nutricia, Abbott and Mead Johnson; speakers fees from AbbVie; Advisory Board member for EosNetwork

Baily – None

Biederman – Consulting fees and/or speaker fees and/or research grants from Dr. Falk Pharma, GmbH, Germany, Vifor AG, Switzerland, Esocap AG, Switzerland, Sanofi-Aventis AG, Switzerland and Calypso Biotech SA

Blanchard – Employed by Société des Produits Nestlé S.A.

Bonis – None

Bose – None

Bredenoord – Research funding from Thelial, Nutricia, Bayer, Norgine, SST and received speaker and/or consultancy fees from Thelial, AstraZeneca, Celgene, Regeneron/Sanofi, Arena,

DrFalkPharma, Esocap, Calypso Biotech, Alimentiv

Chang – Advisory Boards for Takeda, Sanofi Genzyme, Lucid Diagnostics

Chehade – Consultant: Regeneron, Allakos, Adare/Ellodi, Shire/Takeda, AstraZeneca, Sanofi,

Bristol Myers Squibb, Phathom. Research funding: Regeneron, Allakos, Shire/Takeda, AstraZeneca, Adare/Ellodi, Danone

Collins – Consultant for Alimentiv (formerly Robarts Clinical Trials, Inc), Allakos, Arena, AstraZeneca, Calypso, Esocap, GlaxoSmithKline, Receptos/Celgene/BMC, Regeneron, and Takeda and received research funds from AstraZeneca, Receptos/Celgene/BMC, Regeneron, and Takeda

Di Lorenzo – None

Dias – Honoraria for lectures from Takeda, Ferrer, Danone; consulting fees from Adacyte

Dohil – The University of California, San Diego has a financial interest in Shire Pharmaceuticals the company to which oral viscous budesonide is licensed. Dr. Dohil and the University of California, San Diego may financially benefit from this interest if the company is successful in developing and marketing its own product. The terms of the arrangement have been reviewed by the University of California, San Diego in accordance with its conflict of interest policies

Dupont – Consultant: SAB Abbott, Biostime, Danone, Nestlé, Sodilac

Falk – Consulting: Shire/Takeda, Ellodi, Celgene/BMS, Sanofi/Regeneron, Allakos, Lucid Grant Support: Arena, Shire/Takeda, Ellodi, Celgene/BMS, Sanofi/Regeneron, Allakos, Lucid DSMB: Revolo

Ferreira – None

Fox – President of British Society of Allergy & Clinical Immunology & Chair of Health Advisory Board of Allergy UK, which both receive commercial sponsorship

Genta – None

Greuter – Consulting/speaker fees from Abbvie, Norgine, Pfizer, Takeda, Dr Falk Pharma, Janssen, received travel grants from Vifor Pharma, and a non-restricted research grant from Novartis Foundation for Biomedical Research

Gupta – Consultant: Abbott, Adare, Allakos, Celgene, Gossamer Bio, QOL, UpToDate, Medscape, Viaskin; research support: Shire; Allakos; Adare

Hirano – Consulting fees: Adare/Ellodi, Allakos, Amgen, Arena, AstraZeneca, Celgene/Receptos/BMS, Eli Lilly, EsoCap, Gossamer Bio, Parexel/Calyx, Phathom, Regeneron, Sanofi, and Shire/Takeda; research funding: Adare/Ellodi, Allakos, Arena, AstraZeneca, Meritage, Celgene/Receptos/BMS, Regeneron/Sanofi, and Shire/Takeda

Hiremath – None

Horsley-Silva – Research funding (clinical trial site) for Regeneron/Sanofi, Allakos, Celgene Brisol-Myers Squibb. Has participated in advisory board for Sanofi Genzyme

Ishihara – Scholarship donations from Nippon Kayaku Co., Ltd., JIMRO Co., Ltd., EA Pharma Co., Ltd., KYORIN Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., Zeria Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., Mitsubishi Tanabe Pharma Corporation and Mochida Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., Eisai, Co., Ltd., and Otsuka Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., and lecture fees from Abbvie GK, Takeda Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., JIMRO Co., Ltd., EA Pharma Co., Ltd., KYORIN Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., Zeria

Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., Mitsubishi Tanabe Pharma Corporation, Mochida Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., Daiichi Sankyo Co., Ltd., Janssen Pharmaceutical K.K., OLYMPUS, Otsuka

Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., AstraZeneca plc, Chugai Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., and Zeon Medical Inc.

Ishimura – Lecture fees from Takeda Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., and Otsuka Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., and research grant from AstraZeneca

Jensen – None

Gutiérrez-Junquera – None

Katzka – Research funding and consulting: Takeda and Regeron

Khoury – None

Kinoshita – None

Kliewer – None

Koletzko – Consulting/speaker fees from Abbvie, Biocodex, Danone, Janssen, Nestlé Nutrition, Pharmacosmos, Mead Johnson, Menarini, Shire, Takeda, ThermoFisher, Vifor

Leung – None

Liacouras – Consultant: Abbott, Ellodi, AstraZeneca; Speaker: Abbott

Lucendo – Research funding: Adare/Ellodi, Dr. Falk Pharma, and Regeneron; Consultant: Dr. Falk Pharma and EsoCap

Martin – None

McGowan – Research funding: Regeneron

Menard-Katcher – None

Metz – None

Miller – None

Moawad – Consultant and Advisory Board: Takeda, Sanofi/Regeneron

Muir – None

Mukkada – Consultant for Shire/Takeda, Allakos, Sanofi/Genzyme; Adjudication board for Alladapt

Murch – None

Nhu – Advisory Board consulting fees, Takeda, Sanofi Genzyme

Nomura – None

Nurko – Consultant for IHS

Ohtsuka – None

Oliva – Advisory and Speaker fees - Medtronic

Orel – Consultant and/or speaker for Nutricia, BioGaia, Medis, Abbvie, Lek, DrFalk

Papadopoulou – Research funding: Abbvie, United Pharmaceuticals, Dr. Falk Pharma GmbH, Takeda, Astra Zeneca; Advisory board: Adare Pharmaceuticals, Dr. Falk Pharma GmbH, Specialty Therapeutics; Honorarium for lectures: Uni-Pharma Pharmaceuticals, Nestle, Cross, Petsiavas

Patel – None

Pesek – Consultant for Takeda

Peterson – Consulting fees from Alladapt, Astra Zeneca, Allakos, Bristol Meyers Squibb, Ellodi, Lucid, Takeda, Regeneron, Medscape. She receives speakers fees from Takeda, Peerview, and Regeneron. She has equity in Nexeos Bio

Philpott – Consultant for Dr Falk Pharma and Arena Pharmaceuticals

Putnam – None

Richter – None

Rosen – Consultant – Jansen Pharmaceuticals

Ruffner – None

Safroneeva – Consulting or speaker fees from Alimentiv Inc., AVIR Pharma, Inc., and Sanofi-Aventis Deutschland GmbH

Schreiner – Consulting fees from Pfizer, Takeda and Janssen-Cilag and travel support from Falk, UCB and Pfizer

Schoepfer – None

Schroeder – Research funding: Regeneron, Allakos

Shah – Reckitt Healthcare Chief Medical Officer Nutrition

Souza – Research funding from Sanofi and Phathom Pharmaceuticals. Consultant for Cernostics, Phathom Pharmaceuticals, Interpace Diagnostics, Ironwood Pharmaceuticals, ISOThrive, CDx Diagnostics, Eli Lilly, and AstraZeneca

Spechler – Consultant for Phathom Pharmaceuticals, Ironwood Pharmaceuticals, Takeda Pharmaceuticals, Interpace Diagnostics, Cernostics, and ISOThrive

Spergel – None

Straumann – Consultant contracts with AstraZeneca, EsoCap, Falk Pharma International, Receptos-Celgene, Regeneron-Sanofi and Shire

Talley – Non-financial support from HVN National Science Challenge NZ, personal fees from Aviro Health (Digestive health) (2019), Anatara Life Sciences, Brisbane (2019), Allakos (gastric eosinophilic disease) (2021), Bayer [IBS] (2020), Danone (Probiotic) (2018), Planet Innovation (Gas capsule IBS) (2020), Takeda, Japan (gastroparesis) (2019), twoXAR (2019) (IBS drugs), Viscera Labs, (USA 2021) (IBS-diarrhoea), Dr Falk Pharma (2020) (EoE), Censa, Wellesley MA USA (2019) (Diabetic gastroparesis), Cadila PharmIncaceuticals (CME) (2019), Progenity Inc. San Diego, (USA 2019) (Intestinal capsule), Sanofi-aventis, Sydney (2019) (Probiotic), Glutagen (2020) (Celiac disease), ARENA Pharmaceuticals (2019) (Abdominal pain), IsoThrive (2021) (oesophageal microbiome), BluMaiden (2021), Rose Pharma (2021), Intrinsic Medicine (2021) outside the submitted work; In addition, Dr. Talley has a patent Nepean Dyspepsia Index (NDI) 1998, Biomarkers of IBS licensed, a patent Licensing Questionnaires Talley Bowel Disease Questionnaire licensed to Mayo/Talley, a patent Nestec European Patent licensed, and a patent Singapore Provisional Patent “Microbiota Modulation Of BDNF Tissue Repair Pathway” issued, “Diagnostic marker for functional gastrointestinal disorders” Australian Provisional Patent Application 2021901692. Committees: OzSage, Australian Medical Council (AMC) [Council Member]; Australian Telehealth Integration Programme; MBS Review Taskforce; NHMRC Principal Committee (Research Committee) Asia Pacific Association of Medical Journal Editors. Boards: GESA Board Member, Sax Institute, Committees of the Presidents of Medical Colleges. Community group: Advisory Board, IFFGD (International Foundation for Functional GI Disorders), AusEE. Miscellaneous: Avant Foundation (judging of research grants). Editorial: Medical Journal of Australia (Editor in Chief), Up to Date (Section Editor), Precision and Future Medicine, Sungkyunkwan University School of Medicine, South Korea, Med (Journal of Cell Press). Dr. Talley is supported by funding from the National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) to the Centre for Research Excellence in Digestive Health and he holds an NHMRC Investigator grant.

Thapar – Consultancy and speaker fees from Takeda and Danone/Nutricia

Vandenplas – None

Venkatesh – None

Vieira – None

von Arnim – Speaker and/or consultancy fees from EsoCap, Abbvie, Galapagos, Takeda, Dr. Falk foundation, Regeneron/Sanofi, Vifor, Amgen, Janssen

Walker – None

Wechsler – Consultant fees: Regeneron, Allakos, AstraZeneca, Sanofi, InvenAI. Clinical trial funding: Regeneron, Allakos

Wershil – Speaker: Mead Johnson Nutritionals, Abbott Nutrition

Wright – Research funding from Allakos

Yamada – None

Yang – None

Zevit – Advisory fees - Adare Pharmaceuticals, Dr. Falk Pharma; Speakers fees - Rafa, Sanofi Rothenberg - consultant for Pulm One, Spoon Guru, ClostraBio, Serpin Pharm, Allakos, Celldex, Celgene, Astra Zeneca, Adare/Ellodi Pharma, GlaxoSmith Kline, Regeneron/Sanofi, Revolo Biotherapeutics, and Guidepoint and has an equity interest in the first six listed, and royalties from reslizumab (Teva Pharmaceuticals), PEESSv2 (Mapi Research Trust) and UpToDate. M.E.R. is an inventor of patents owned by Cincinnati Children’s Hospital

Furuta – Founder-EnteroTrack, Research funding-Holoclara, Arena, NIH

Aceves – Co-Inventor, oral viscous budesonide, UCSD patented, Takeda licensed. Consultant-Regeneron, AstraZeneca

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an article that has undergone enhancements after acceptance, such as the addition of a cover page and metadata, and formatting for readability, but it is not yet the definitive version of record. This version will undergo additional copyediting, typesetting and review before it is published in its final form, but we are providing this version to give early visibility of the article. Please note that, during the production process, errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Rothenberg ME. Eosinophilic gastrointestinal disorders (EGID). J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2004;113(1):11–28; quiz 9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gonsalves N. Eosinophilic Gastrointestinal Disorders. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2019;57(2):272–85. Epub 2019/03/25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dellon ES, Liacouras CA, Molina-Infante J, et al. Updated international consensus diagnostic criteria for eosinophilic esophagitis: Proceedings of the AGREE conference. Gastroenterology. 2018;155:1022–33.e10. Epub 2018/07/17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hirano I, Chan ES, Rank MA, et al. AGA Institute and the Joint Task Force on Allergy-Immunology Practice Parameters Clinical Guidelines for the Management of Eosinophilic Esophagitis. Gastroenterology. 2020;158(6):1776–86. Epub 2020/05/04. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rank MA, Sharaf RN, Furuta GT, et al. Technical Review on the Management of Eosinophilic Esophagitis: A Report From the AGA Institute and the Joint Task Force on Allergy-Immunology Practice Parameters. Gastroenterology. 2020;158(6):1789–810 e15. Epub 2020/05/04. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pesek RD, Reed CC, Muir AB, et al. Increasing Rates of Diagnosis, Substantial Co-Occurrence, and Variable Treatment Patterns of Eosinophilic Gastritis, Gastroenteritis, and Colitis Based on 10-Year Data Across a Multicenter Consortium. Am J Gastroenterol. 2019;114(6):984–94. Epub 2019/04/23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pesek RD, Reed CC, Collins MH, et al. Association Between Endoscopic and Histologic Findings in a Multicenter Retrospective Cohort of Patients with Non-esophageal Eosinophilic Gastrointestinal Disorders. Dig Dis Sci. 2020;65(7):2024–35. Epub 2019/11/28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Reed C, Woosley JT, Dellon ES. Clinical characteristics, treatment outcomes, and resource utilization in children and adults with eosinophilic gastroenteritis. Dig Liver Dis. 2015;47(3):197–201. Epub 2014/12/31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ko HM, Morotti RA, Yershov O, et al. Eosinophilic gastritis in children: clinicopathological correlation, disease course, and response to therapy. Am J Gastroenterol. 2014;109(8):1277–85. Epub 2014/06/25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chang JY, Choung RS, Lee RM, et al. A shift in the clinical spectrum of eosinophilic gastroenteritis toward the mucosal disease type. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;8(8):669–75; quiz e88. Epub 2010/05/11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Grandinetti T, Biedermann L, Bussmann C, et al. Eosinophilic Gastroenteritis: Clinical Manifestation, Natural Course, and Evaluation of Treatment with Corticosteroids and Vedolizumab. Dig Dis Sci. 2019;64(8):2231–41. Epub 2019/04/15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yamamoto M, Nagashima S, Yamada Y, et al. Comparison of Nonesophageal Eosinophilic Gastrointestinal Disorders with Eosinophilic Esophagitis: A Nationwide Survey. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2021;9(9):3339–49.e8. Epub 2021/07/03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jensen ET, Martin CF, Kappelman MD, et al. Prevalence of Eosinophilic Gastritis, Gastroenteritis, and Colitis: Estimates From a National Administrative Database. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2016;62:36–42. Epub 2015/05/20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hiremath G, Kodroff E, Strobel MJ, et al. Individuals affected by eosinophilic gastrointestinal disorders have complex unmet needs and frequently experience unique barriers to care. Clin Res Hepatol Gastroenterol. 2018;42:483–93. Epub 2018/04/05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jensen ET, Aceves SS, Bonis PA, et al. High Patient Disease Burden in a Cross-Sectional, Multicenter Contact Registry Study of Eosinophilic Gastrointestinal Diseases. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2020;71:524–9. Epub 2020/06/17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chehade M, Kamboj AP, Atkins D, et al. Diagnostic Delay in Patients with Eosinophilic Gastritis and/or Duodenitis: A Population-Based Study. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2021;9:2050–9.e20. Epub 2021/01/14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Caldwell JM, Collins MH, Stucke EM, et al. Histologic eosinophilic gastritis is a systemic disorder associated with blood and extragastric eosinophilia, TH2 immunity, and a unique gastric transcriptome. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014;134(5):1114–24. Epub 2014/09/23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shoda T, Wen T, Caldwell JM, et al. Molecular, endoscopic, histologic, and circulating biomarker-based diagnosis of eosinophilic gastritis: Multi-site study. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2020;145(1):255–69. Epub 2019/11/19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Reed CC, Genta RM, Youngblood BA, et al. Mast Cell and Eosinophil Counts in Gastric and Duodenal Biopsy Specimens From Patients With and Without Eosinophilic Gastroenteritis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021;19:2102–11. Epub 2020/08/18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gonsalves N, Doerfler B, Zalewski A, et al. Results from the ELEMENT study: Prospective study of elemental diet in eosinophilic gastroenteritis nutrition trial. Gastroenterology. 2020(158 (Suppl 1)):S–43 (AB 229). [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dellon ES, Peterson KA, Murray JA, et al. Anti-Siglec-8 Antibody for Eosinophilic Gastritis and Duodenitis. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(17):1624–34. Epub 2020/10/22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dellon ES, Gonsalves N, Rothenberg ME, et al. Determination of Biopsy Yield That Optimally Detects Eosinophilic Gastritis and/or Duodenitis in a Randomized Trial of Lirentelimab. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021. Epub 2021/06/06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dellon ES, Collins MH, Bonis PA, et al. Substantial Variability in Biopsy Practice Patterns Among Gastroenterologists for Suspected Eosinophilic Gastrointestinal Disorders. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;14(12):1842–4. Epub 2016/04/27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Licari A, Votto M, Scudeller L, et al. Epidemiology of Nonesophageal Eosinophilic Gastrointestinal Diseases in Symptomatic Patients: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2020;8(6):1994–2003.e2. Epub 2020/02/18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ishihara S, Kinoshita Y, Schoepfer A. Eosinophilic Esophagitis, Eosinophilic Gastroenteritis, and Eosinophilic Colitis: Common Mechanisms and Differences between East and West. Inflamm Intest Dis. 2016;1(2):63–9. Epub 2016/07/01. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lucendo AJ, Serrano-Montalban B, Arias A, et al. Efficacy of Dietary Treatment for Inducing Disease Remission in Eosinophilic Gastroenteritis. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2015;61(1):56–64. Epub 2015/02/24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hohmann E, Brand JC, Rossi MJ, et al. Expert Opinion Is Necessary: Delphi Panel Methodology Facilitates a Scientific Approach to Consensus. Arthroscopy. 2018;34(2):349–51. Epub 2018/02/08. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gupta SK, Falk GW, Aceves SS, et al. Consortium of Eosinophilic Gastrointestinal Disease Researchers: Advancing the Field of Eosinophilic GI Disorders Through Collaboration. Gastroenterology. 2019;156(4):838–42. Epub 2018/11/20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rothenberg ME, Hottinger SKB, Gonsalves N, et al. Impressions and Aspirations from the FDA GREAT VI Workshop on Eosinophilic Gastrointestinal Disorders Beyond Eosinophilic Esophagitis and Perspectives for Progress in the Field. J Allergy Clin Immunol. in Press, 2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dellon ES, Aderoju A, Woosley JT, et al. Variability in diagnostic criteria for eosinophilic esophagitis: A systematic review. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102:2300–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Satsangi J, Silverberg MS, Vermeire S, et al. The Montreal classification of inflammatory bowel disease: controversies, consensus, and implications. Gut. 2006;55(6):749–53. Epub 2006/05/16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.