Abstract

Decorin and biglycan are two small leucine-rich proteoglycans (SLRPs) that regulate collagen fibrillogenesis and extracellular matrix assembly in tendon. The objective of this study was to determine the individual roles of these molecules in maintaining the structural and mechanical properties of tendon during homeostasis in mature mice. We hypothesized that knockdown of decorin in mature tendons would result in detrimental changes to tendon structure and mechanics while knockdown of biglycan would have a minor effect on these parameters. To achieve this objective, we created tamoxifen-inducible mouse knockdown models targeting decorin or biglycan inactivation. This enables the evaluation of the roles of these SLRPs in mature tendon without the abnormal tendon development caused by conventional knockout models. Contrary to our hypothesis, knockdown of decorin resulted in minor alterations to tendon structure and no changes to mechanics while knockdown of biglycan resulted in broad changes to tendon structure and mechanics. Specifically, knockdown of biglycan resulted in reduced insertion modulus, maximum stress, dynamic modulus, stress relaxation, and increased collagen fiber realignment during loading. Knockdown of decorin and biglycan produced similar changes to tendon microstructure by increasing the collagen fibril diameter relative to wild-type controls. Biglycan knockdown also decreased the cell nuclear aspect ratio, indicating a more spindle-like nuclear shape. Overall, the extensive changes to tendon structure and mechanics after knockout of biglycan, but not decorin, provides evidence that biglycan plays a major role in the maintenance of tendon structure and mechanics in mature mice during homeostasis.

Keywords: tendon, biomechanics, decorin, biglycan, proteoglycan

Introduction

Tendon is a dense connective tissue composed of highly organized uniaxial collagen fibrils that provides joint stability and transmits force between muscle and bone. It is composed primarily of collagens, water, proteoglycans, glycoproteins, and cells.1 The composition of the extracellular matrix (ECM) is vital for normal development and maintenance of tendon structure, mechanical properties, and function.2 Small leucine-rich proteoglycans (SLRPs) have been implicated in regulation of fibrillogenesis, and the resulting establishment of tendon structure and mechanics. The most abundant SLRPs in tendon are decorin and biglycan, two class I SLRPs with structurally similar core proteins with one or two glycosaminosglycan (GAG) chains, respectively, that compete for binding sites on fibrillar collagens.3,4 While decorin expression constitutes approximately 80% of SLRP expression in tendon,5 compensatory upregulation has been demonstrated with biglycan after knockdown, indicating functional redundancy between these proteins.6–8

Previous studies have attempted to determine the roles of decorin and biglycan in mature tendon mechanics and structure using knockout models.9–14 Overall, these studies consistently demonstrated that decorin and biglycan knockout impacted viscoelastic mechanics and collagen fibril structure, with decorin knockout often resulting in the more severe tendon phenotype while biglycan knockout impacted tendon properties to a lesser degree.11–14 This led to the suggestion of coordinated role for these SLRPs with biglycan having a more modulatory role during tendon development. However, the precise roles of decorin and biglycan in establishing and maintaining tendon properties during homeostasis is still unclear. A major obstacle in interpreting the results of these studies is the inability to isolate effects in homeostasis due to the impact of SLRP knockout during tendon development that occurs with the use of conventional knockout models. Tamoxifen (TM) inducible mouse knockdown models provide the ability to temporally control SLRP expression, removing the confounding variable of altered developmental processes when determining the precise roles of decorin and biglycan in maintaining mature, homeostatic tendon mechanical properties and structure.

Our lab has recently used TM-inducible knockdowns to explore changes in tendon mechanics, structure, and composition after loss of decorin and biglycan expression in adult mice.15 The TM-inducible compound-null decorin and biglycan (I-Dcn−/−/Bgn−/−) mouse model was used to define the effects of decorin and biglycan knockout (together) in mature mice 30 days after Cre induction.15 The absence of decorin and biglycan resulted in inferior mechanical properties and altered collagen fibril structure.15 However, the individual roles of decorin and biglycan in these changes, and whether one of these was the dominant driver of the changes, remains unknown.

Therefore, the purpose of this study was to determine the individual roles of each molecule in tendon mechanics and structure in mature mice during homeostasis utilizing TM-inducible knockdown of decorin or biglycan for 30 days in mature mice. Conventional knockouts that target decorin and biglycan indicated that decorin is the primary SLRP in developing and maintaining tendon structure and mechanics, while knockout of biglycan had minimal effect on these parameters.10,11,16 Additionally, biglycan expression is known to peak shortly after birth, while decorin expression stays consistent.17 Therefore, we hypothesized that knockdown of decorin in mature tendon would result in detrimental changes to tendon mechanics and structure, while knockdown of biglycan would have a lesser effect on these parameters.

Methods

Mice

Adult female wild type control mice, Dcn+/+/Bgn+/+ (WT, n=16) as well as inducible Dcnflox/flox (I-Dcn−/−, n=16), and Bgnflox/flox (I-Bgn−/−, n=16) mice were utilized. The conditional Dcnflox/flox and Bgnflox/flox mice with a tamoxifen (TM) inducible Cre, (B6.129-Gt(ROSA)26Sortm1(cre/ERT2)Tyj/J, Jackson Labs) have been previously described.15 All mice were in a C57/BL6 background (Charles River). Female mice were utilized for all groups in this study because Bgn is located on the X chromosome. All personnel were blinded during data collection. This study was approved by the University of South Florida and the University of Pennsylvania Institutional Animal Care and Use Committees.

Cre-induction Protocol

I-Dcn−/− and I-Bgn−/− knockout mice and WT mice received three consecutive daily intraperitoneal tamoxifen injections (4.5 mg/40 g body weight) beginning at 120d, then were euthanized at 150d.15 WT mice received tamoxifen injections to control for any unintended side effects.

Biomechanics

Patellar tendons (n = 12–14/group) were prepared for mechanical testing as previously described.18 Briefly, patella-tendon-tibia complexes were dissected, then scanned using a custom laser device to measure cross-sectional area.19 Verhoeff’s stain was used to apply stain lines at the tibial insertion, 1 mm and 2 mm from the tibial insertion, and at the distal patella for optical strain tracking. The tibia was secured in a custom 3D-printed pot using poly(methyl methacrylate). Custom fixtures were used to secure the pot and patella during mechanical testing.

During testing, tendons were loaded into a 1x phosphate-buffered saline bath at 37°C secured to a tensile testing system (Instron 5848, Instron, Norwood, MA) integrated with an established cross-polarized light setup.15,20 The viscoelastic testing protocol consisted of preconditioning, stress relaxations for 600 seconds at 3%, 4%, and 5% strain with each followed by a series of 10 frequency sweeps at 0.1, 1, 5, and 10 Hz, a return to gage length for 60 s, and ending with a ramp-to-failure at a strain rate of 0.1%/s. A series of image maps, each consisting of 18 images taken at 0.07s intervals with a 12s gap between each image map, were taken throughout the ramp-to-failure for collagen fiber realignment and optical strain tracking data.20 Collagen fiber realignment, outputted as circular variance, was calculated using a custom program, and has an inverse relationship with the realignment of collagen fibers (Matlab R2015a, Mathworks, Inc., Natick, MA).21

Maximum stress was calculated from stress-strain data. Optical tracking was used to compute midsubstance and insertion modulus at the tibial insertion (Matlab R2015a, Mathworks, Inc., Natick, MA). Dynamic modulus (E*) and tan (δ), representing the phase shift in the stress-strain relationship, were calculated at each strain-frequency combination.

Gene Expression and Protein Content

Real-time PCR

Patellar tendons were collected at the time of sacrifice and stored under liquid nitrogen. Frozen patellar tendons were cut into small pieces and total RNA was extracted using a RNeasy Micro Kit (QIAGEN). Total RNA (4 ng/well) was subjected to reverse transcription using the High-Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription Kit (Applied Biosystems) and real-time PCR was performed with Fast SYBR Green PCR master mix (Applied Biosystems) on a StepOnePlus Real Time PCR system (Applied Biosystems). The primer sequences are listed in Table 1. Each sample was run in duplicate (n = 5/group) and data were analyzed using StepOne software c2.0 (Applied Biosystems). b-actin was used as an internal control to standardize the amount of sample total RNA.

Table 1 –

Primer sequences used for real-time PCR.

| Forward Primer | Reverse Primer | |

|---|---|---|

| Dcn | TGAGCTTCAACAGCATCACC | AAGTCATTTTGCCCAACTGC |

| Bgn | CTACGCCCTGGTCTTGGTAA | ACTTTGCGGATACGGTTGTC |

| Fmod | GAAGGGTTGTTACGCAAATGG | AGATCACCCCCTAGTCTGGGTTA |

| Lum | TCCACTTCCAAAGTCCCTGCAAGA | AAGCCGAGACAGCATCCTCTTTGA |

| Kera | CCTGGAAAGCAAGGTGCTGTA | TCATAGGCCTGTCTCACACTCTGT |

| Col1a1 | CTTCACCTACAGCACCCTTGTG | TGACTGTCTTGCCCCAAGTTC |

| β-actin | AGATGACCCAGATCATGTTTGAGA | CACAGCCTGGATGGCTACGT |

Immuno-blots

Decorin and biglycan content was analyzed immuno-chemically using a Wes™ automated Western blotting system (ProteinSimple, San Jose, CA). Tendons were dissected at day 150. Individual mice (n=3) were used for each genotype. Two tendons from each mouse were cut into small pieces and protein was extracted using an extraction buffer composed of 4 M guanidine-HCl, 50 mM sodium acetate, pH 5.8 with proteinase inhibitor (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA) at 4°C for 48 hr with shaking. The extraction was clarified by centrifugation and then went through 7K MWCO Zeba Spin Desalting Columns (Peirce Biotechnology, Rockford, IL) to change to the digestion buffer containing 150 mM Tris-HCl, 150 mM NaCl, pH 7.3. Samples were digested with chondroitinase ABC (Seikagaku Biobusiness Corporation, Tokyo, Japan) for 24 hr at 37°C. Total protein concentration was determined using BCA protein assay kit (Pierce Biotechnology, Rockford, IL). Samples were diluted with 0.1× sample buffer (ProteinSimple, San Jose, CA) at a concentration of either 0.2 μg/μl for detecting biglycan or further diluted 10 times for detecting decorin using WES system. Denatured protein samples were loaded into single designated wells of Wes Separation 12–230 kDa 25 Capillary Cartridges, rabbit anti-mouse decorin (LF113, 1:500 dilution, provided by Dr. L. Fisher, NIH-NIDCR) antibody or biglycan antibody (LF159, 1:100 dilution, provided by Dr. L. Fisher, NIH-NIDCR) and the Wes anti-rabbit detection module was used for detection. Quantification by densitometry was performed using the area of the targeted protein and normalized to total protein amount, which was analyzed by loading an equal amount of protein to a separate capillary cartridge and detected with the Wes total protein detection module. All Wes reagents (separation module and detection modules) were purchased from ProteinSimple and the Wes assay was carried out following the manufacturer’s instructions. Data analyses were performed using the Compass Software (ProteinSimple).

Histology

For histological analysis (n = 4/group) the knee joint was isolated by cutting through the femur and tibia at the time of sacrifice. The knee was flexed to 90°, placed into a cassette, fixed in formalin, and processed using standard paraffin histological techniques. Samples were embedded in paraffin and sections were cut at 7 μm thickness before staining with hematoxylin and eosin. Two sections were imaged per sample, then cell nuclear shape and cellularity were quantified within a 2000 μm ×1500 μm region of interest (ROI) using commercial software (BIOQUANT Image Analysis Corporation, Nashville, TN).

Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM)

Patellar tendons from 4 different mice per group were analyzed using TEM. Samples were fixed in situ using standard methods.15,22,23 Post-staining with 2% aqueous uranyl acetate followed by 1% phosphotungstic acid, pH 3.2, was utilized for contrast enhancement. Cross sections through the midsubstance of the patellar tendons were examined at 80 kV using a JEOL 1400 transmission electron microscope. Images were digitally captured at an instrument magnification of 60,000x using an Orius widefield sidemount CCD camera at a resolution of 3648 × 2672. The digital images were masked and transferred to a RM Biometrics-Bioquant Image Analysis System (Memphis, TN) for analysis. Image magnification was calibrated using a line grating replica (PELCO®, Product No. 606). Fibril diameter analyses were completed using images from the central portion of the tendon. All fibrils within a 2800 nm × 2000 nm ROI on the digitized image were analyzed. Non-overlapping ROIs were placed based on fibril orientation (i.e., cross section) and absence of cells. Diameters were measured along the minor axis of the fibril. For measurements of fibril density, the total number of fibrils within the ROI was normalized for area.

Statistics

All data was tested for normality using the Shapiro-Wilk test. For all biomechanics measurements and gene and protein content, a one-way ANOVA across genotype with Bonferroni post-hoc test was performed. Collagen realignment data was analyzed using a two-way ANOVA across genotype and repeated strain level with Bonferroni post-hoc tests. Nuclear aspect ratio, cellularity, and fibril diameter distributions were compared using Kolmogorov-Smirnov tests with Bonferroni post-hoc. Statistical significance was set at p<0.05.

Results

Gene Expression and Protein Content

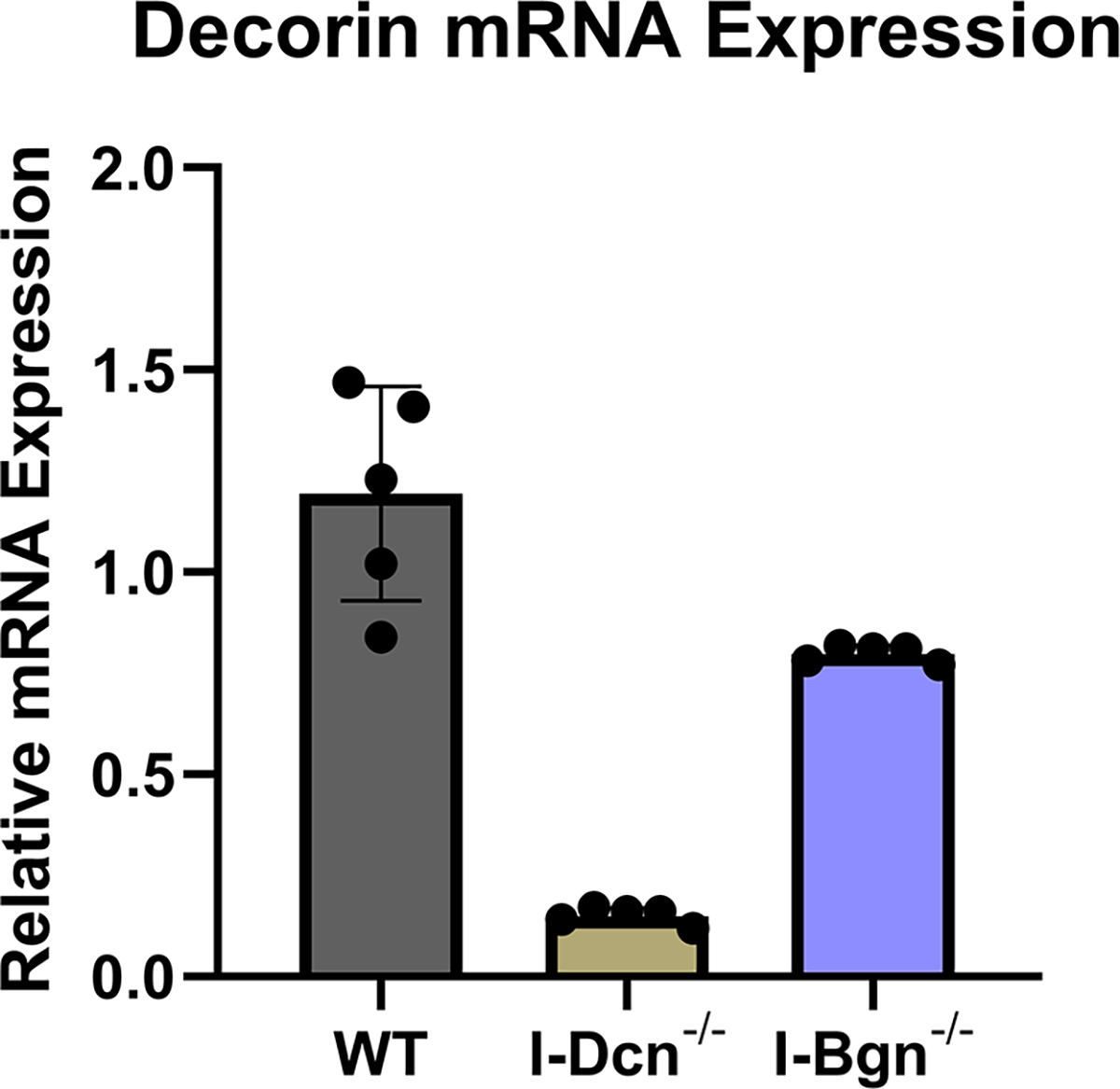

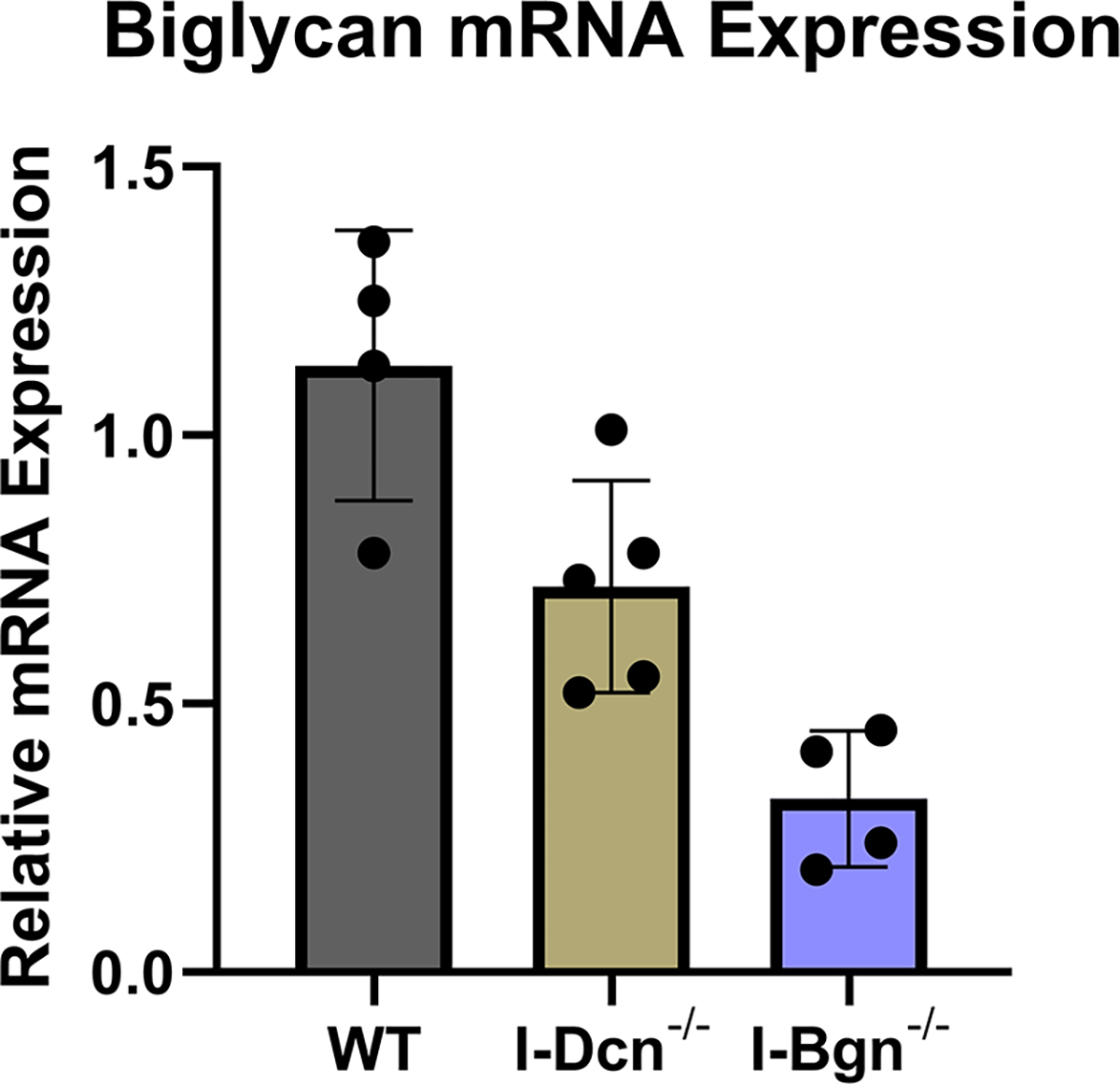

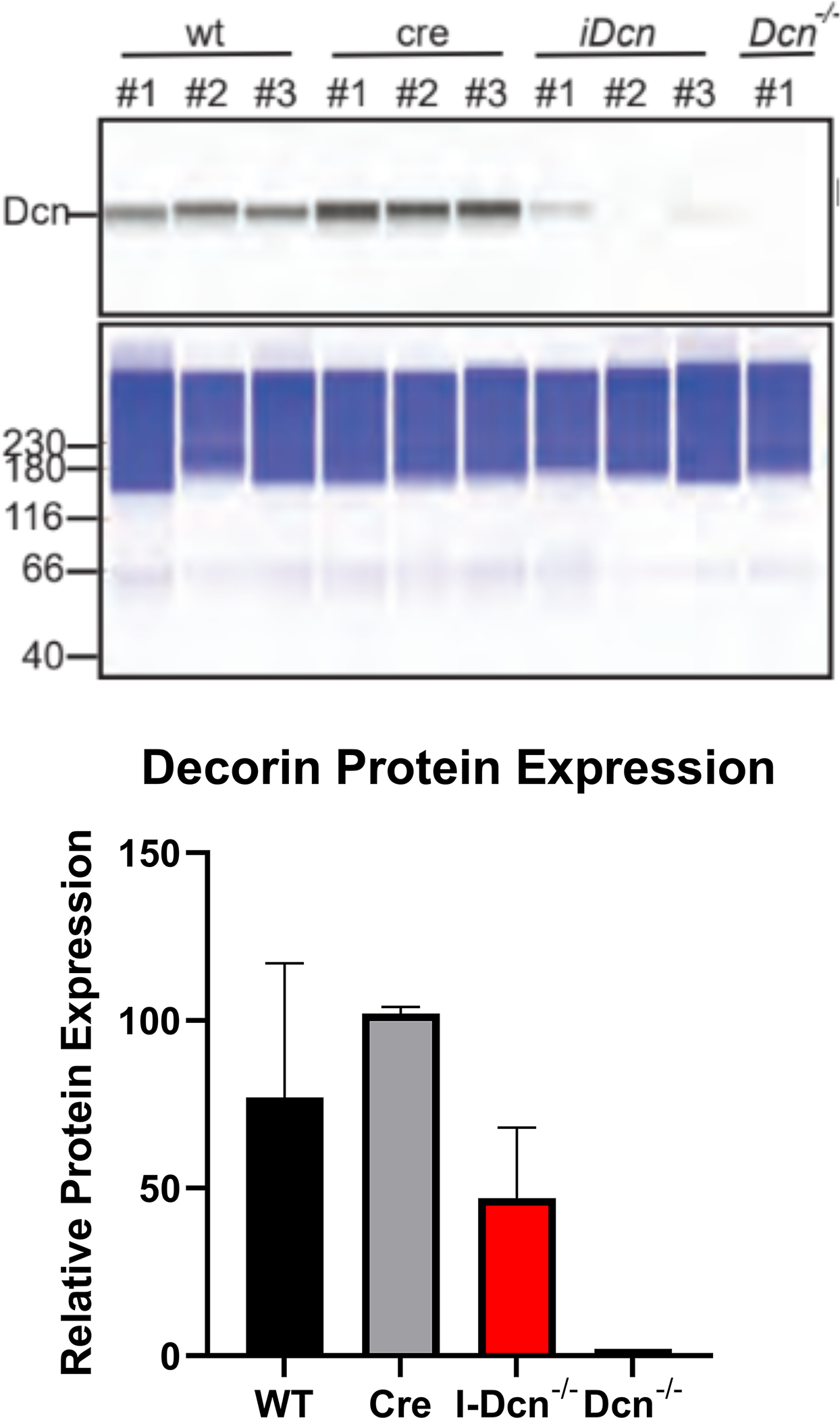

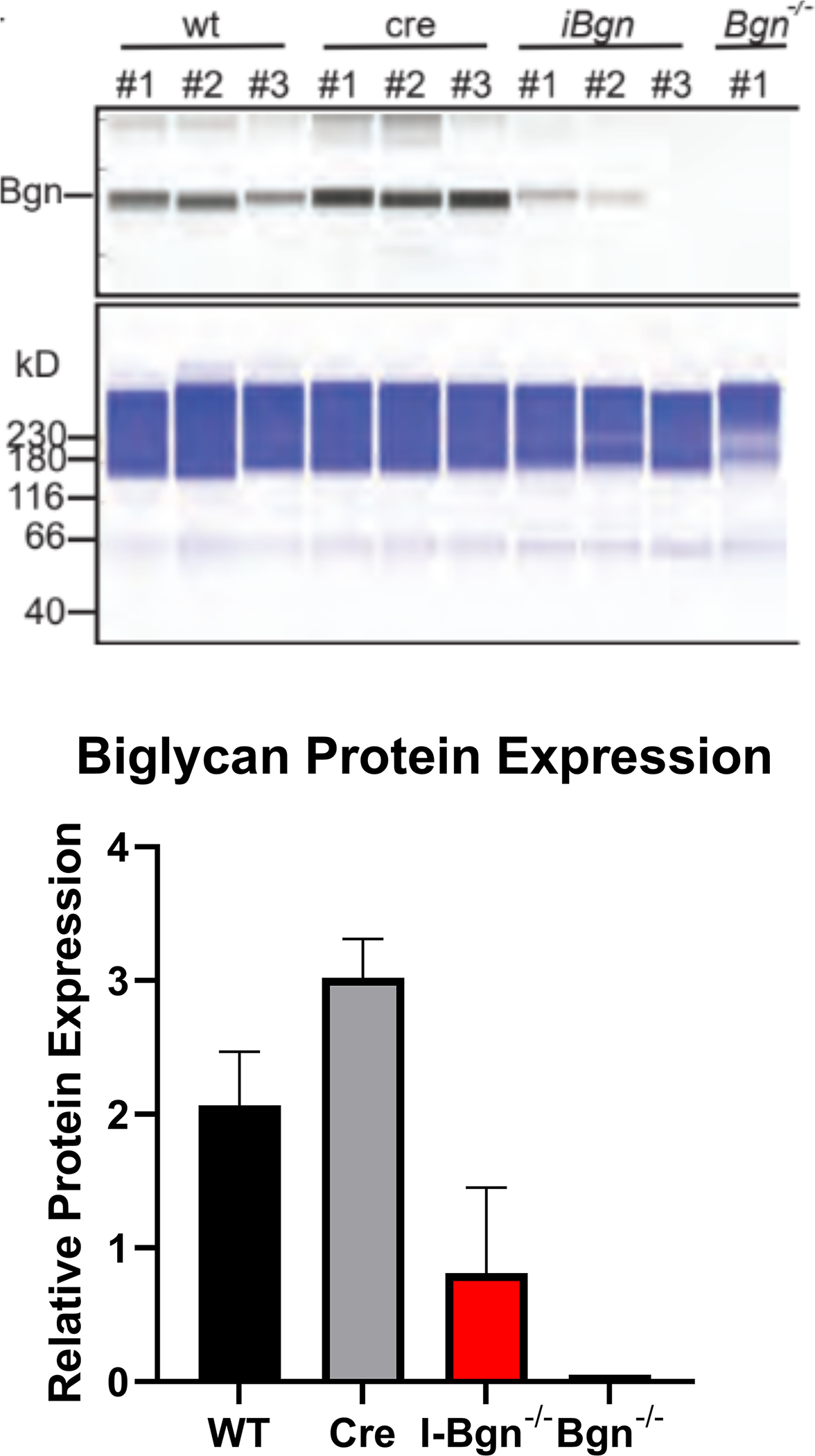

Both decorin and biglycan mRNA expression were knocked down in the patellar tendon 30 days after Cre induction in the mature I-Dcn−/− and I-Bgn−/− mice (Fig. 1A–B). Both groups showed consistent results with reduced protein content for decorin and biglycan in their respective knockdown groups 30 days after induction (Fig. 1C–D). Both knockdown groups were reduced compared to control groups. However, conventional knockout protein content was higher than what was observed in the traditional knockout mice. Presumably this is due to incomplete turnover of SLRPs deposited prior to knockdown. There was no evidence of compensatory upregulation of biglycan in I-Dcn−/− or decorin in I-Bgn−/− mice (Fig. 1A–B). The lack of compensation after knockdown of decorin and biglycan in our mouse models gives us confidence that the changes in phenotype are due to reduced content of the target protein, and not obscured by the functional redundancy between decorin and biglycan.

Figure 1 –

(A) Dcn mRNA expression was reduced in the I-Dcn−/− patellar tendons and (B) Bgn mRNA expression was reduced in the I-Bgn−/− patellar tendons after tamoxifen treatment. (C) The immunoblots revealed reduced decorin and (D) biglycan protein content in the I-Dcn−/− and I-Bgn−/− groups, respectively.

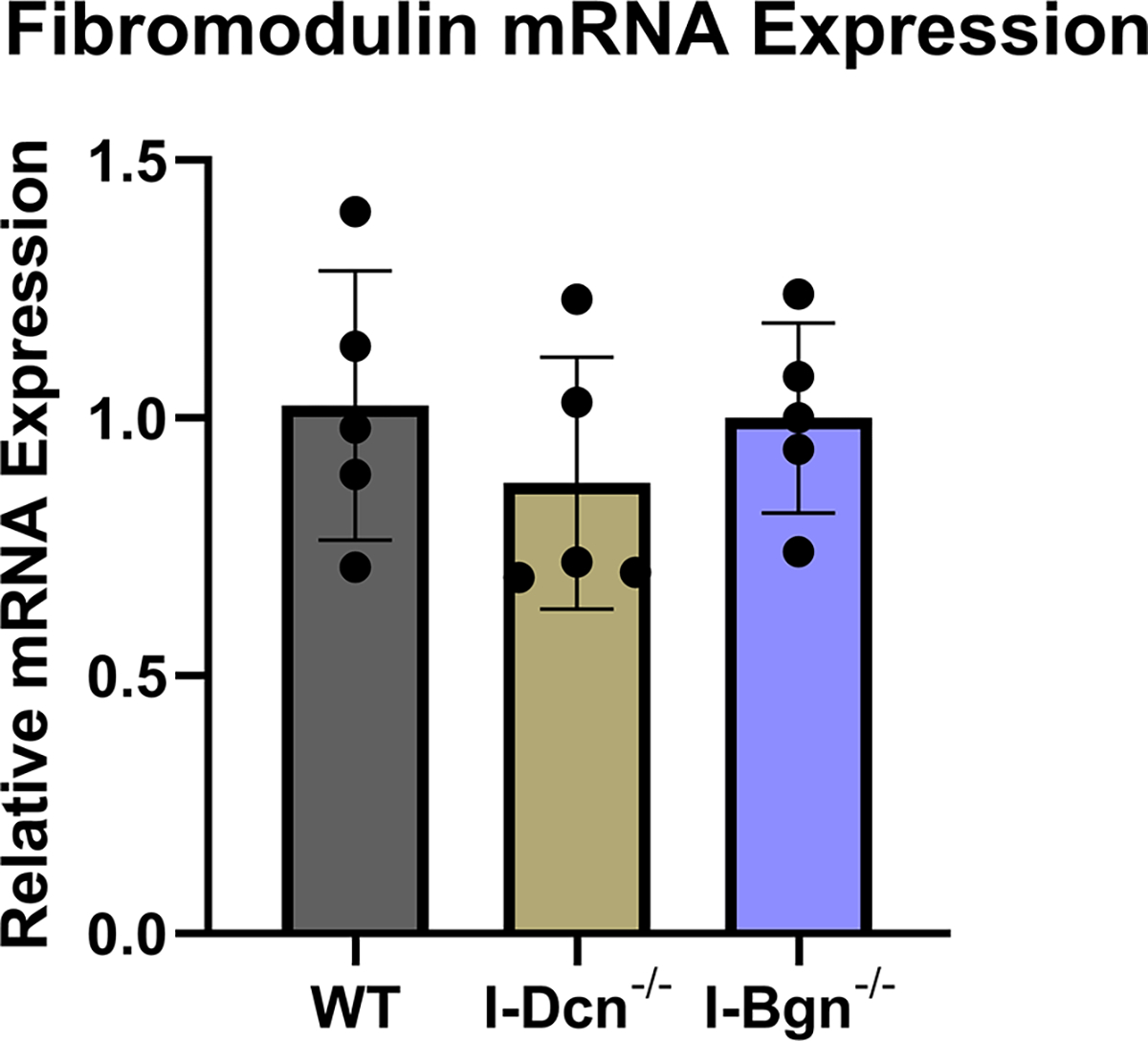

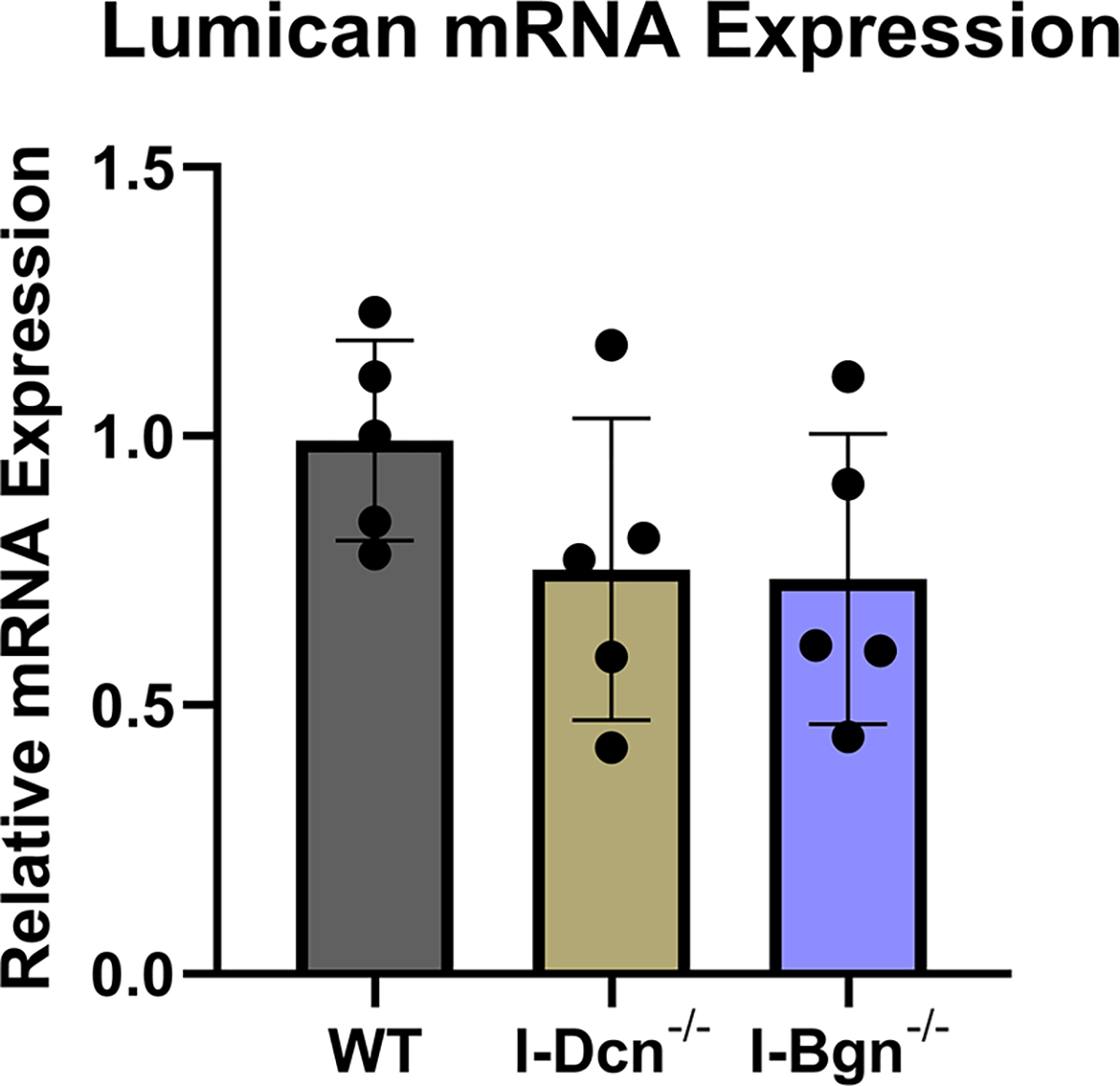

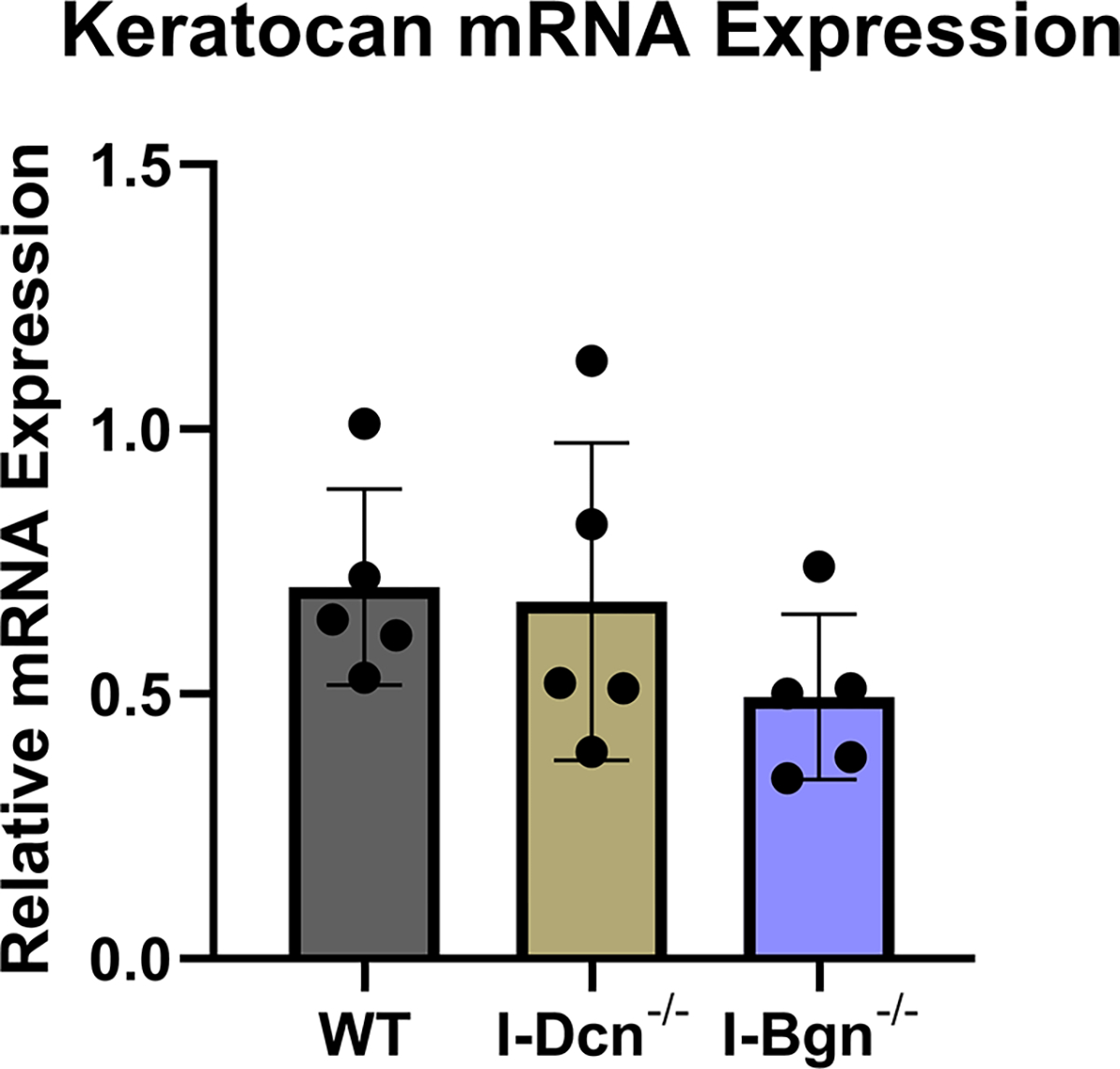

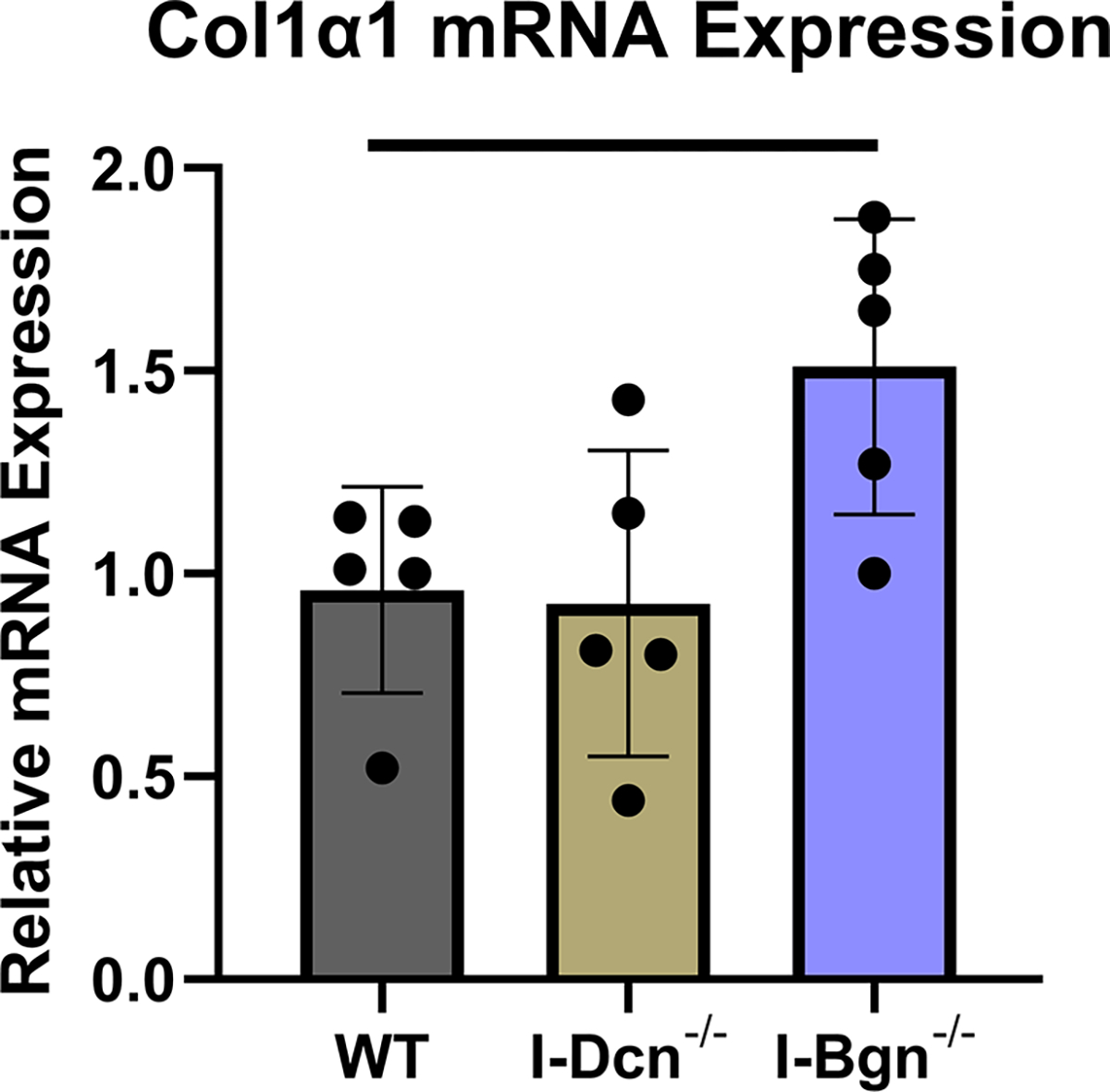

The expression of closely related class II SLRPs known to have roles in fibrillogenesis, fibromodulin (Fmod), lumican (Lum), and keratocan (Kera), were analyzed to determine if any compensatory alterations in expression occurred because of decorin of biglycan knockdown. No significant changes in mRNA expression of Fmod, Lum, or Kera were observed after knockdown of decorin or biglycan (Fig. 2A–C). Collagen I expression was examined after knockdown using the alpha1(I) chain of collagen I as a marker. Expression in I-Dcn−/− mice was comparable to that in WT control mice. However, there was a significant increase in collagen I expression I-Bgn−/− tendons compared to WT (Fig. 2D).

Figure 2 –

There were no changes in mRNA expression levels of (A) Fmod, (B) Lum, and (C) Kera after knockdown of decorin or biglycan. (D) Upregulation of Col1α1 was observed after biglycan knockdown.

Biomechanical Properties

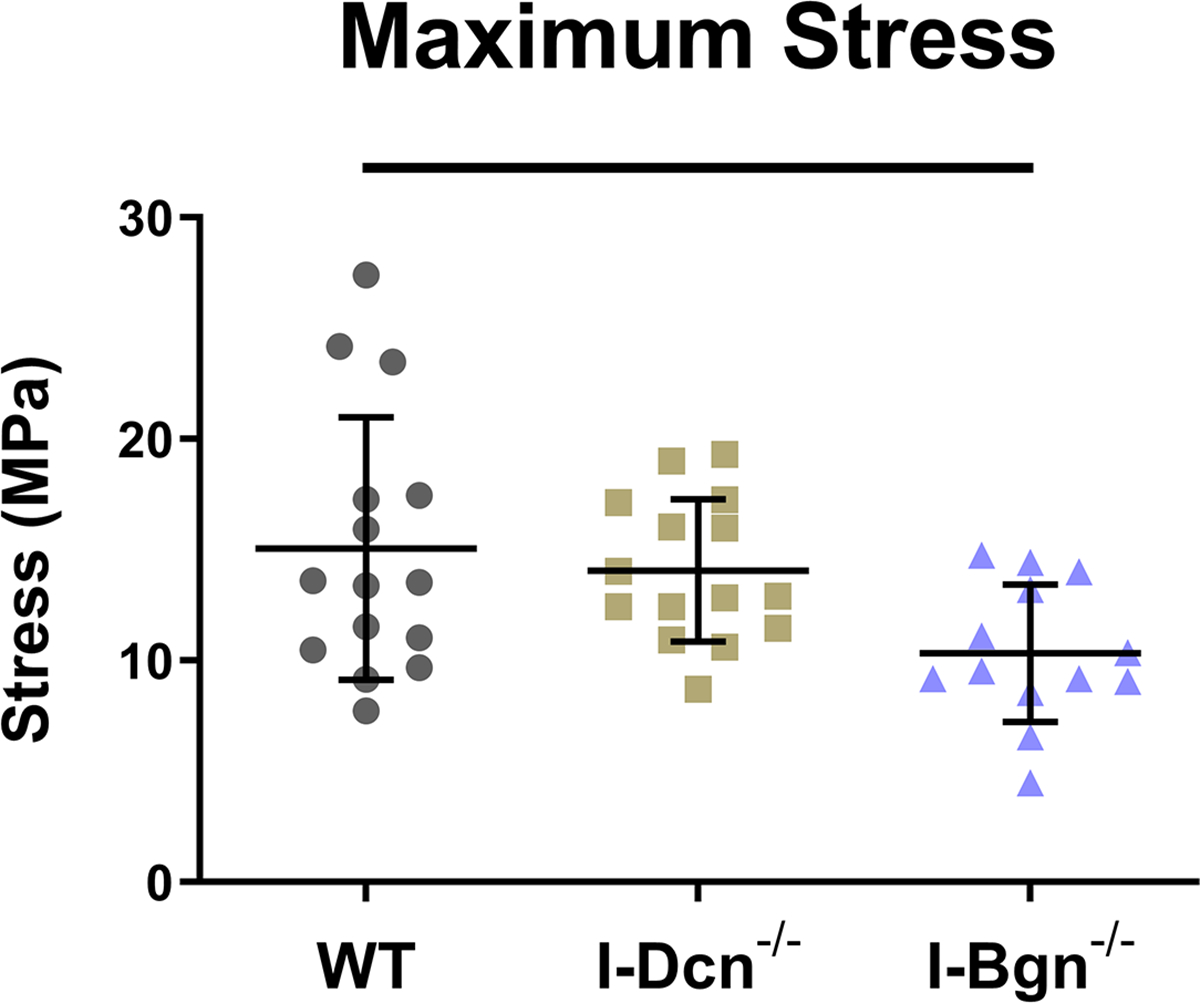

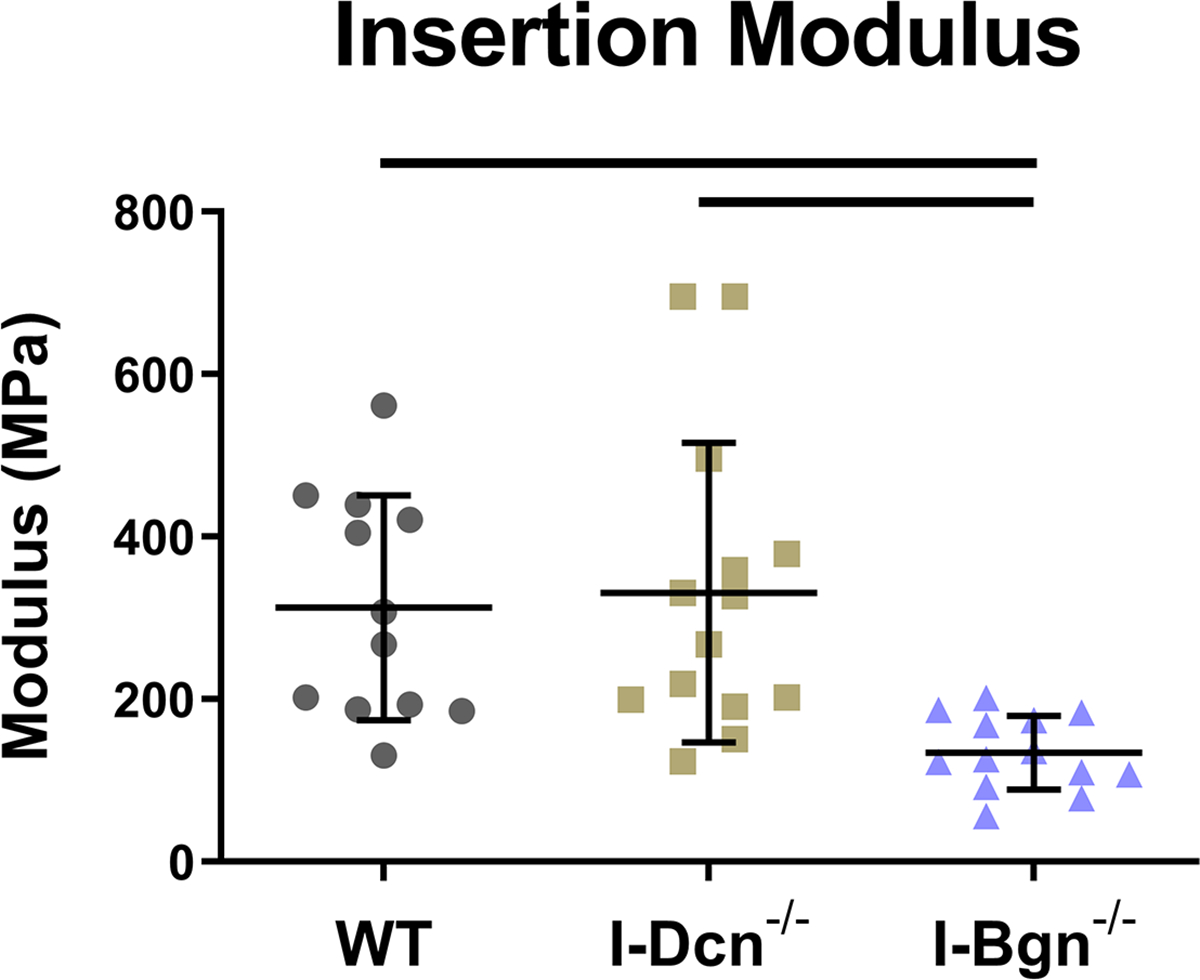

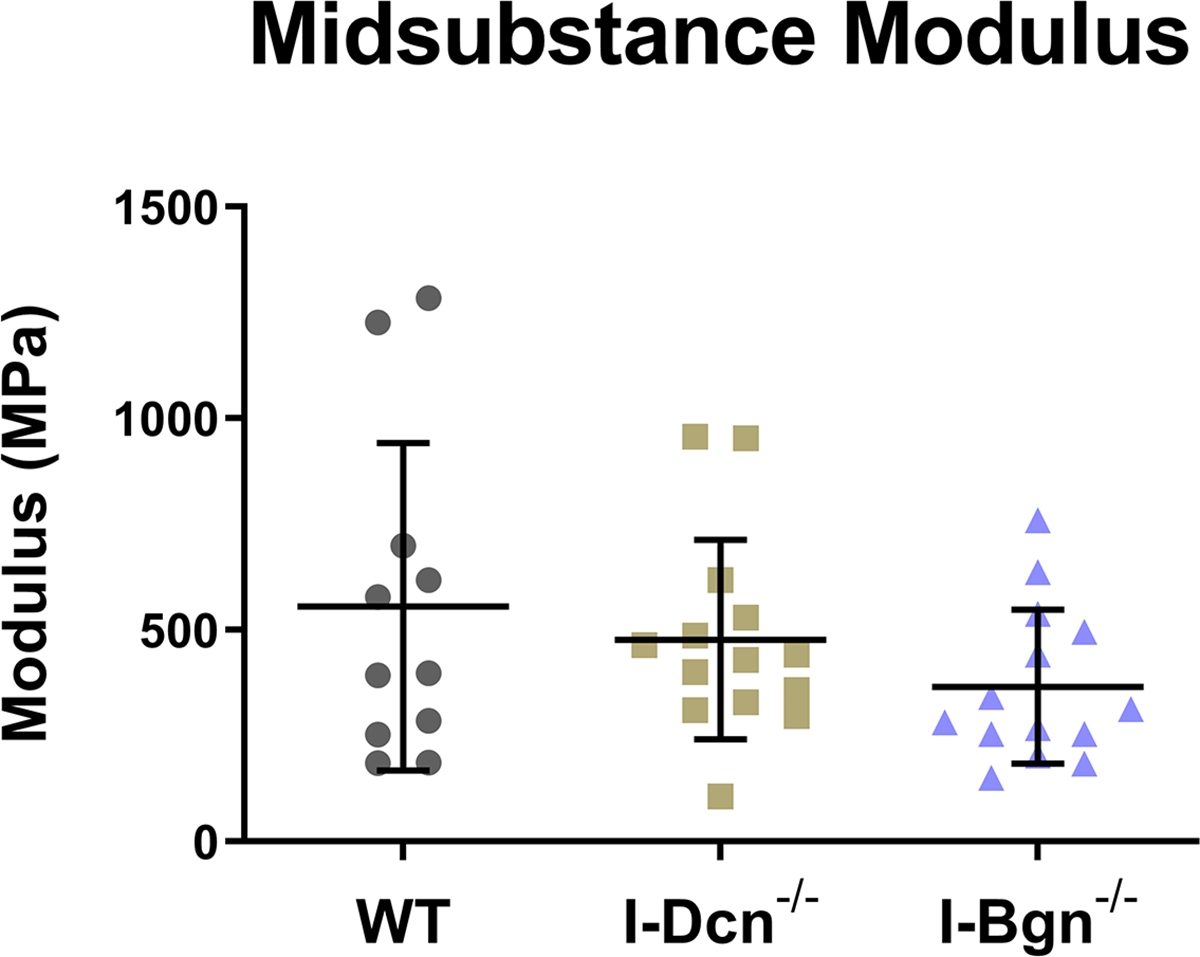

The quasistatic and viscoelastic biomechanical properties of the mouse patellar tendons were evaluated. Quasistatic mechanics analysis revealed decreased maximum stress in the I-Bgn−/− group vs WT, while no changes were seen in I-Dcn−/− (Fig. 3A). Insertion modulus showed a decrease in I-Bgn−/− compared to WT and I-Dcn−/− (Fig. 3B), while there were no differences between any groups in the midsubstance modulus (Fig. 3C). The tendons primarily failed at the tibial insertion with no sign of bony avulsion.

Figure 3 –

(A) Maximum stress and (B) insertion modulus were significantly reduced in the absence of biglycan, while these properties were unaffected in the absence of decorin. Midsubstance modulus was not affected in the absence of decorin or biglycan, indicating that the absence of biglycan has regional effects on patellar tendon mechanics.

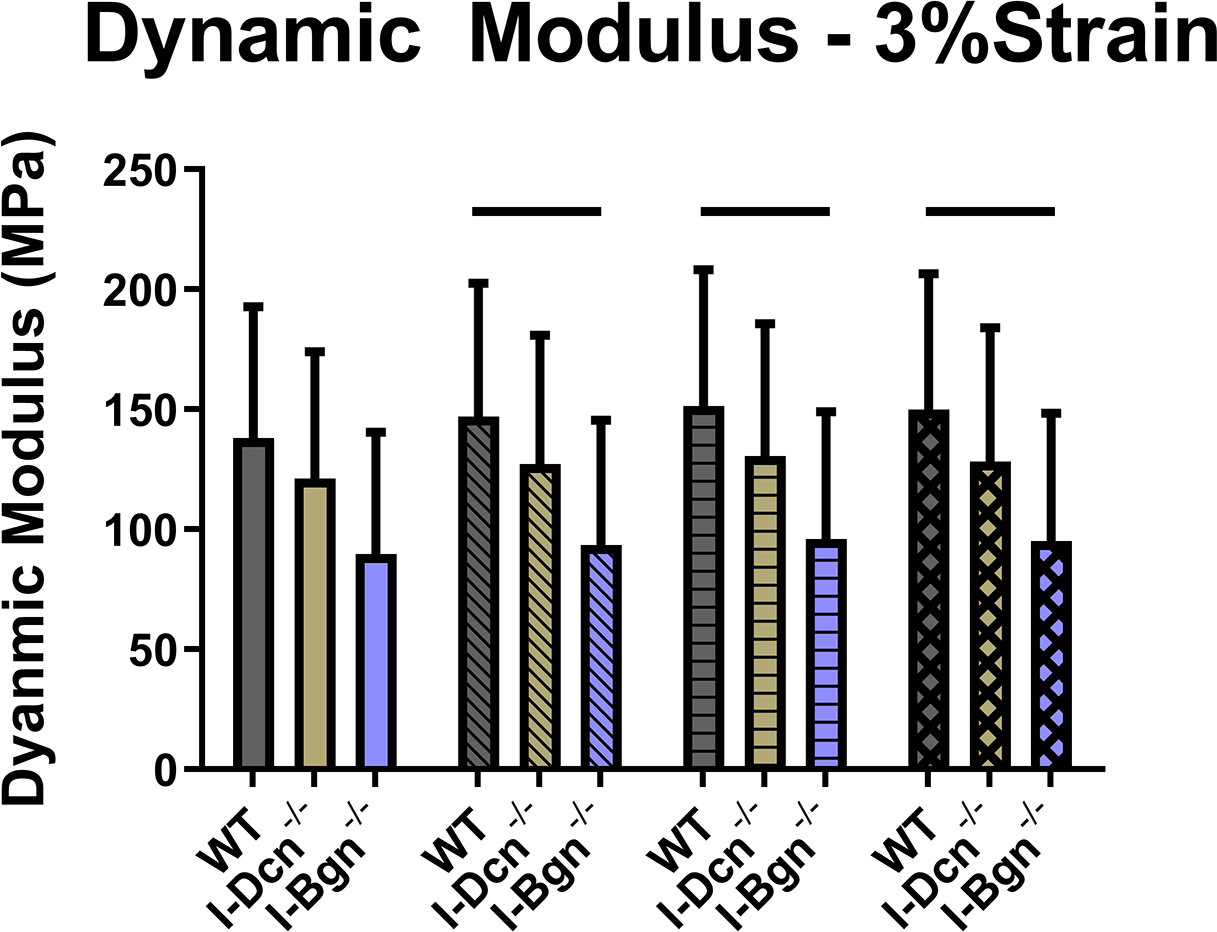

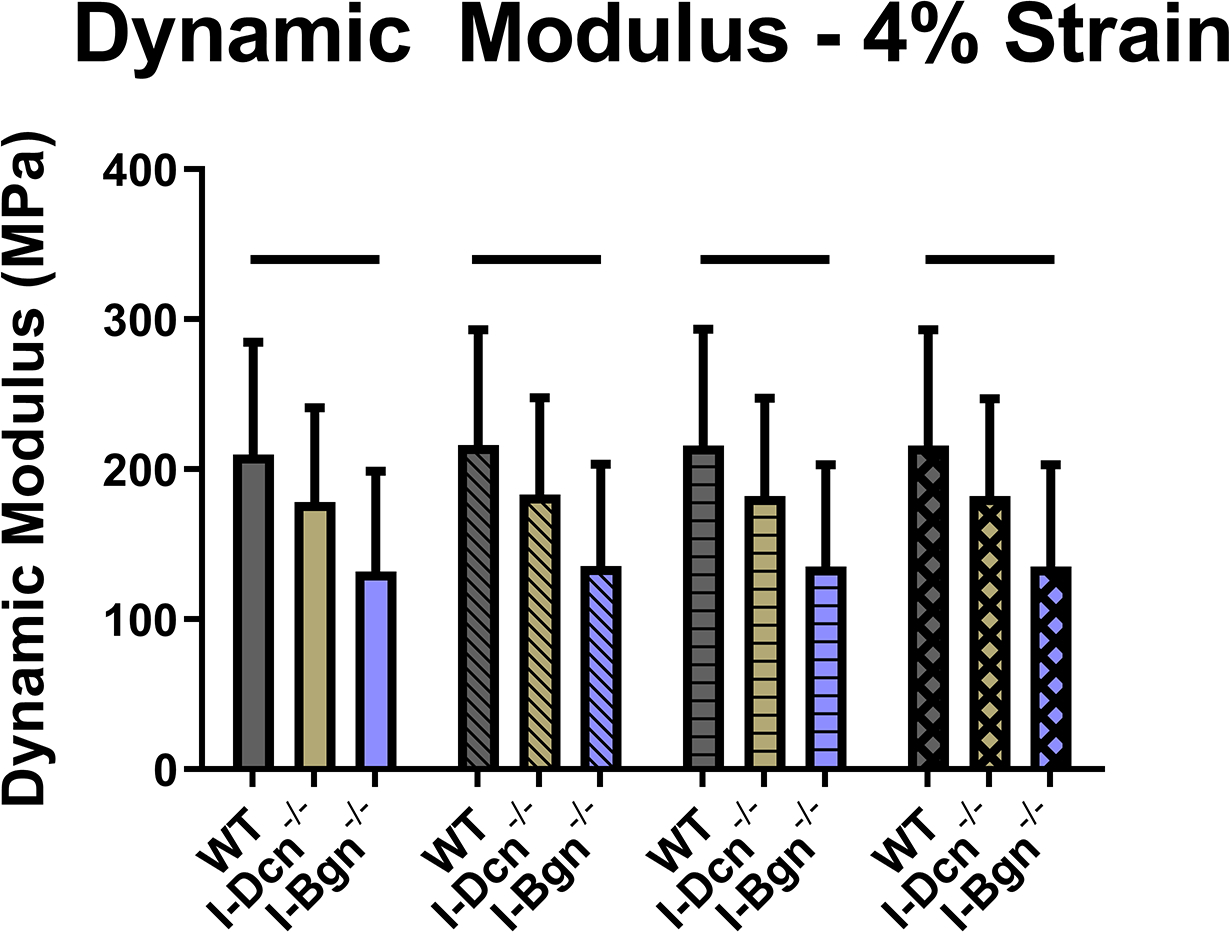

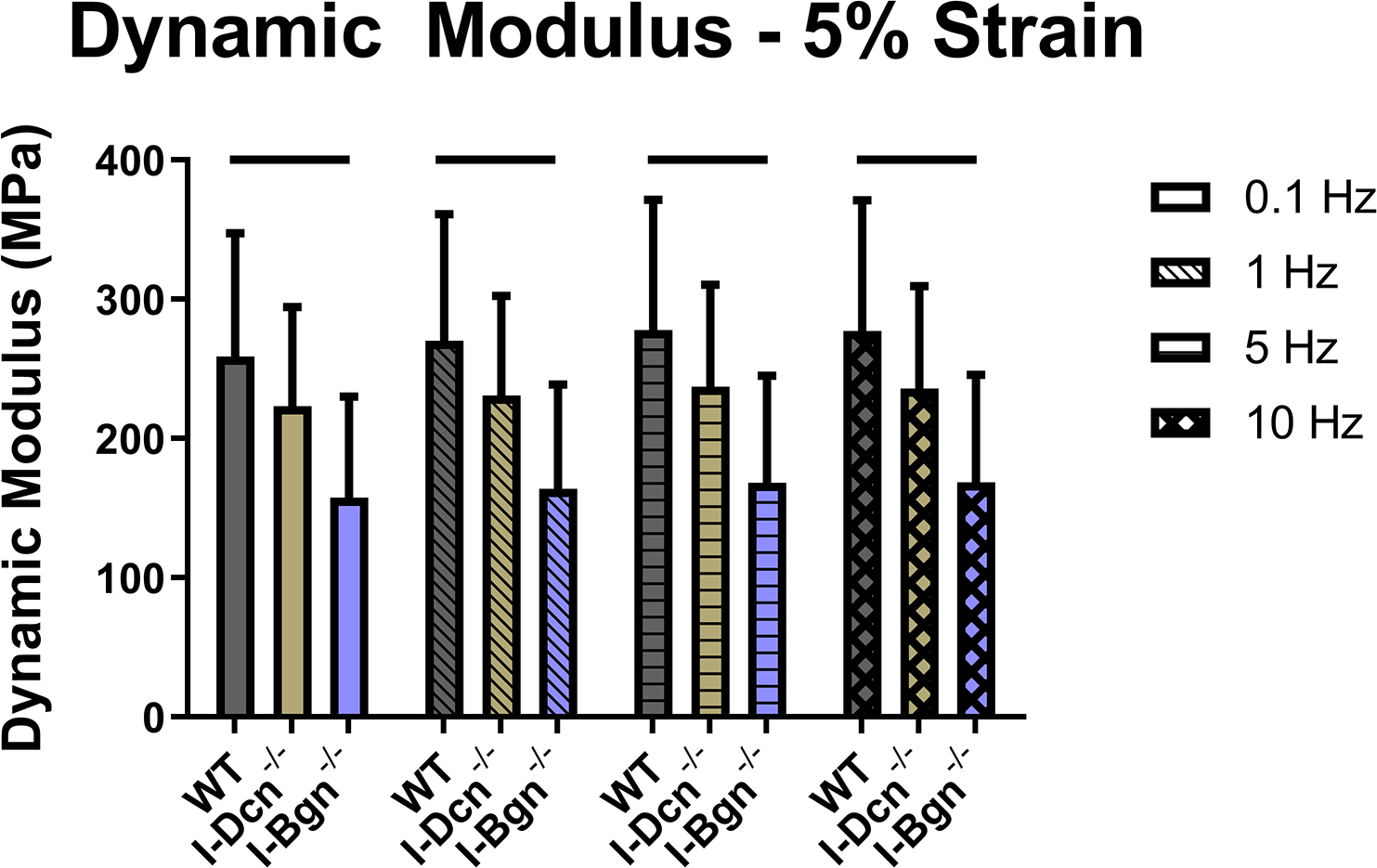

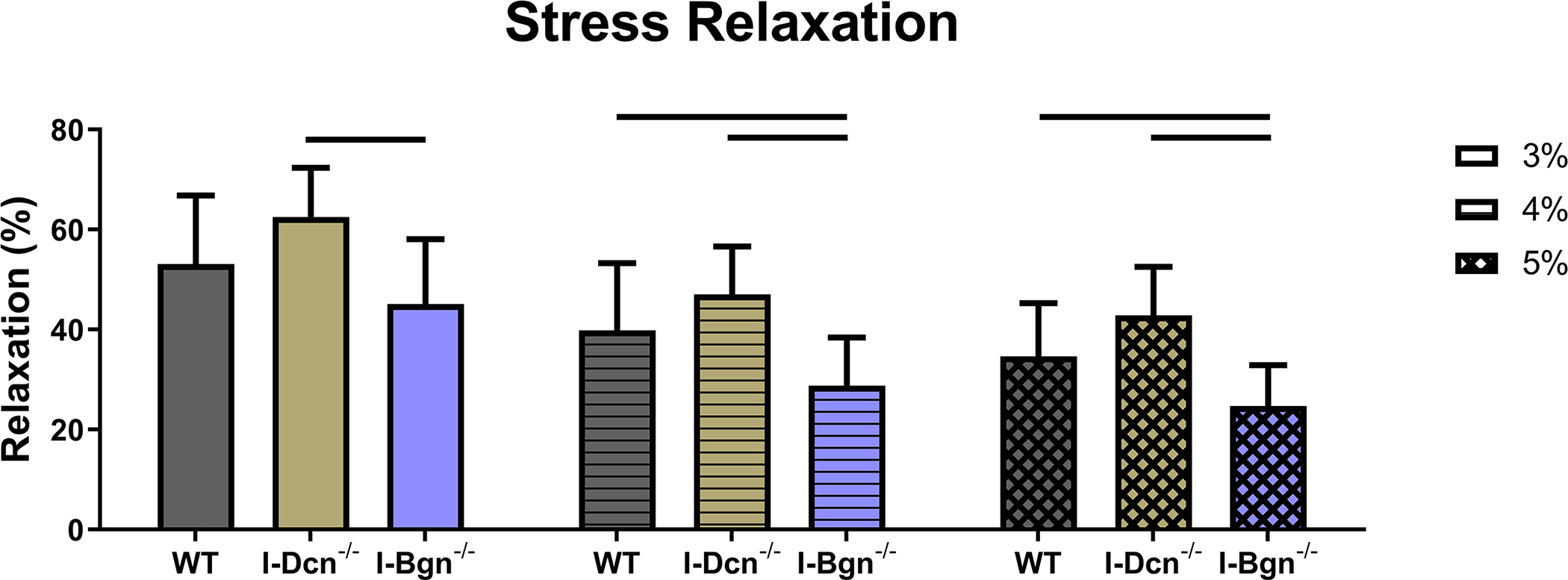

Viscoelastic mechanics were evaluated at 3%, 4%, and 5% (Fig. 4A–C) strain, correlating with the toe, transition, and linear regions of the stress-strain curve for mouse patellar tendons, respectively. Further supported by the quasistatic mechanics results, viscoelastic properties were reduced in the I-Bgn−/− group. Dynamic modulus was reduced in the absence of biglycan at all strains and frequencies compared to WT, except for 3% strain at 0.1 Hz (Fig. 4A). No changes to dynamic modulus were found in the absence of decorin, and no changes in phase shift were found between groups at any strain (not shown). Additionally, the stress relaxation tests showed a decrease in the percent relaxation between I-Bgn−/− and I-Dcn−/− at all strains and decreases between I-Bgn−/− and WT at 4% and 5% strain (Fig. 5).

Figure 4 –

Dynamic modulus decreased at (A) 3%, (B) 4%, and (C) 5% strain in the I-Bgn−/− group, indicating a reduced ability to resist deformation during dynamic loading. These results are consistent across all loading frequencies except for 0.1 Hz at 3% strain where no changes were present in the I-Bgn−/− group. No changes in dynamic modulus were observed after knockdown of decorin.

Figure 5 –

During the stress relaxation test at 3% strain, the percent relaxation of I-Bgn−/− tendons decreased compared to the I-Dcn−/− group. The precent relaxation of the I-Bgn−/− tendons also decreased at 4% and 5% strain relative to the I-Dcn−/− and WT groups.

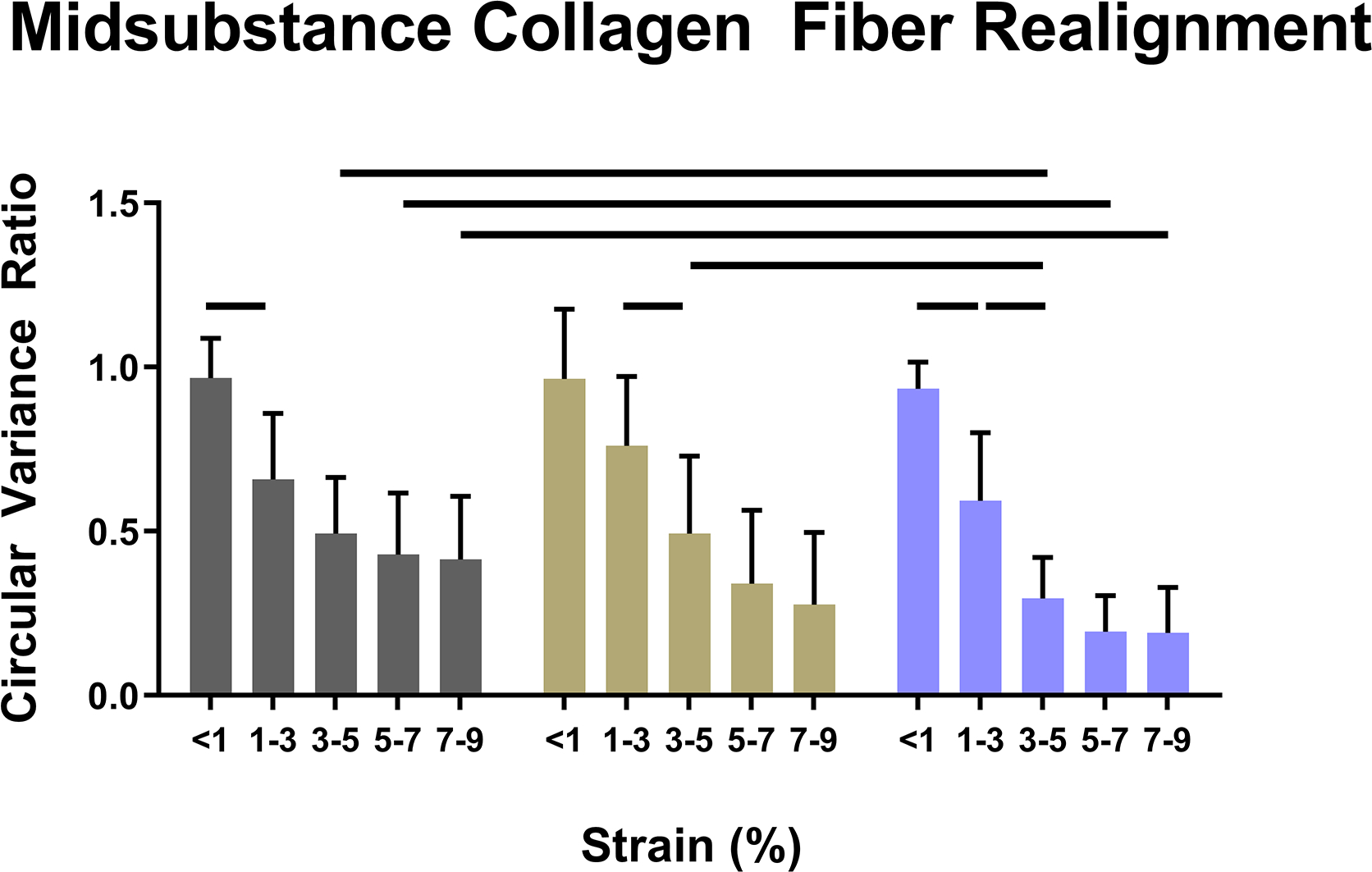

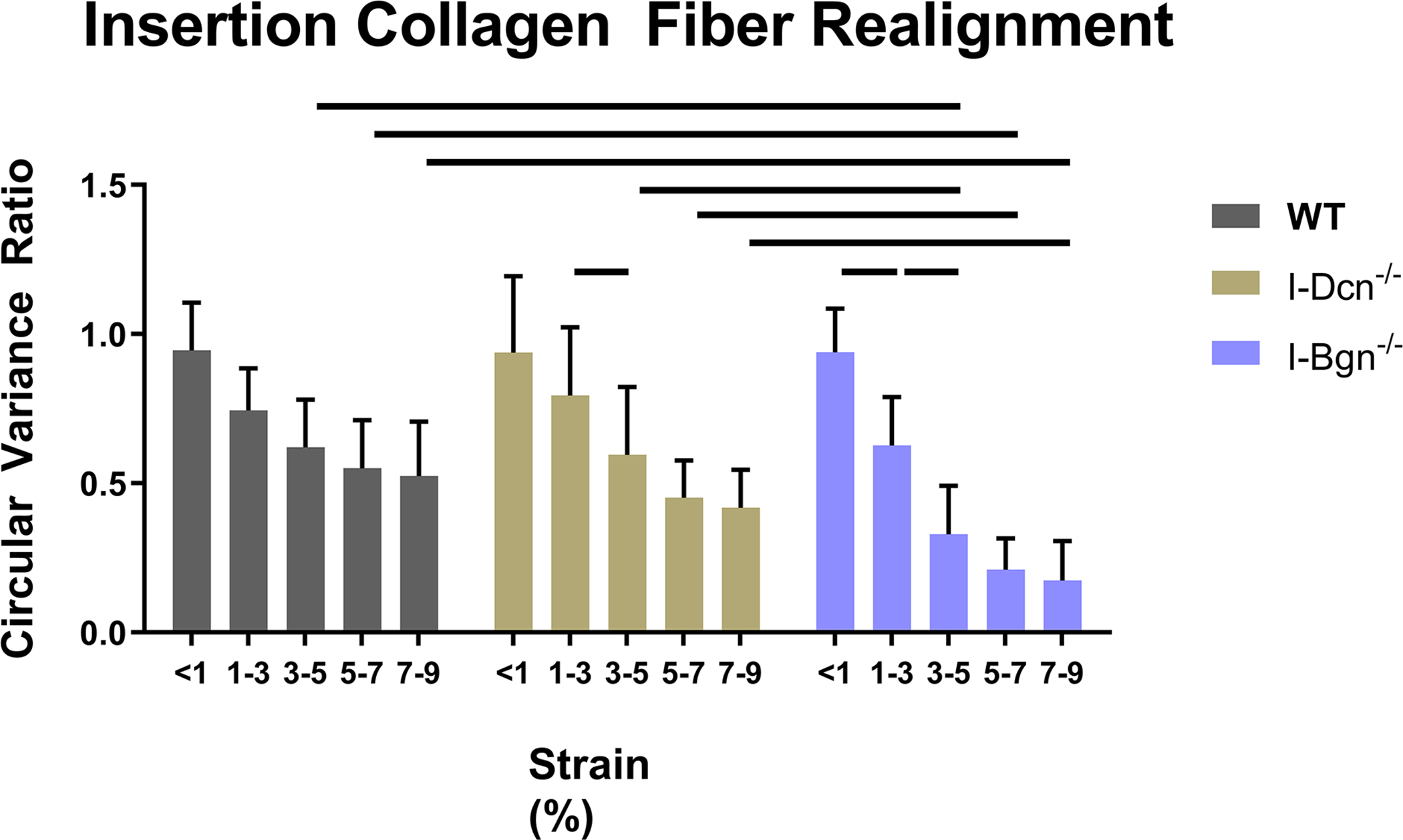

Collagen fiber realignment was altered in the absence of both decorin and biglycan (Fig. 6). In the midsubstance and insertion, I-Dcn−/− realignment was delayed, while I-Bgn−/− realignment occurred over a larger range of strains (Fig. 6A). I-Bgn−/− also showed increased levels of realignment in the midsubstance compared to I-Dcn−/− at 3–5% strain, and increased midsubstance realignment compared to WT at 3–5%, 5–7%, and 7–9% strain. Results were similar in the insertion, with the absence of biglycan resulting in increased realignment at 3–5%, 5–7%, and 7–9% strain compared to both WT and I-Dcn−/− (Fig. 6B).

Figure 6 –

Knockdown of decorin delayed collagen fiber realignment in the (A) midsubstance and (B) insertion regions of the tendons. Knockdown of biglycan caused fiber realignment to occur over a larger range of strains and to a greater extent than the I-Dcn−/− and WT groups in both regions of the tendon.

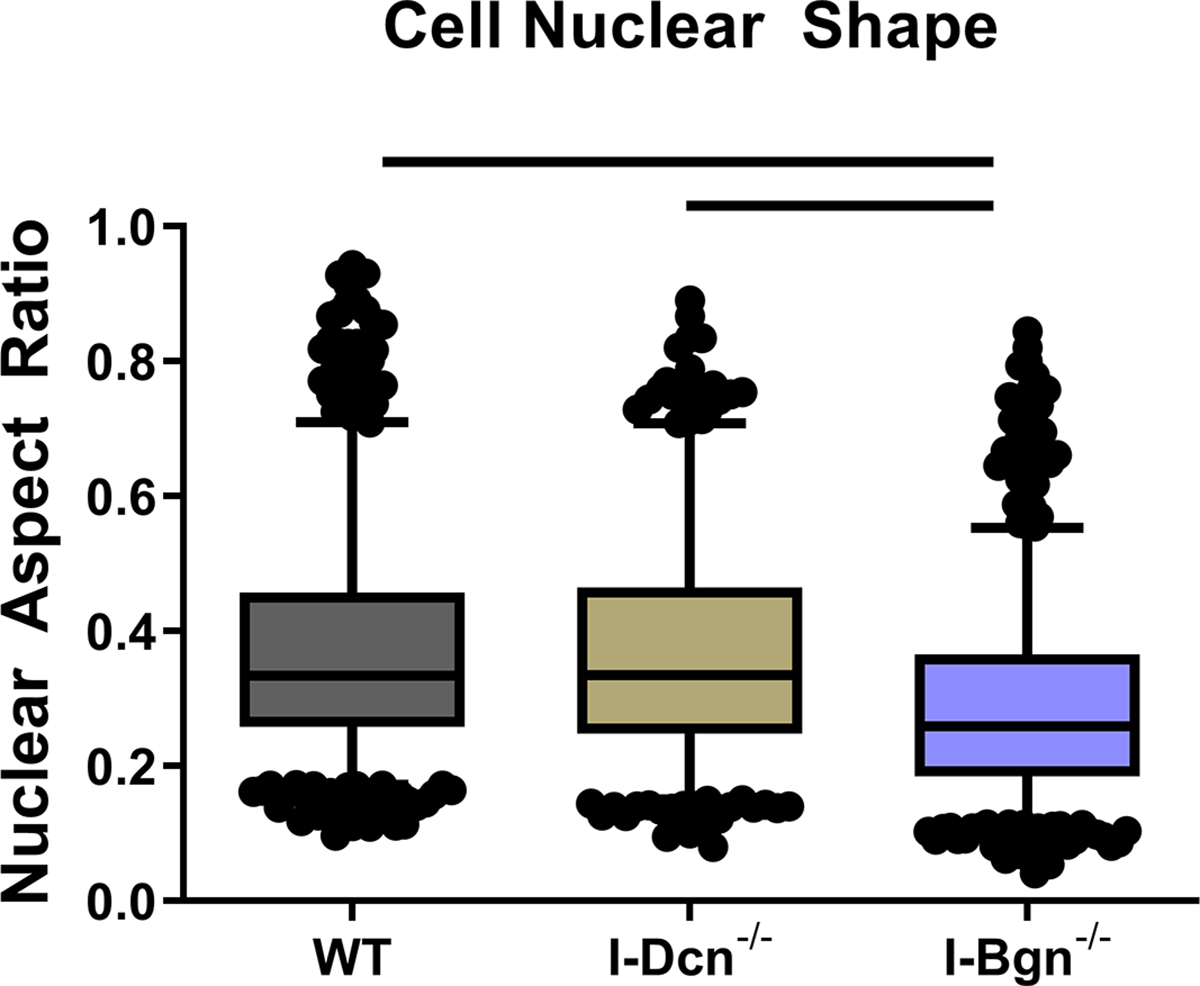

Histology

Histological analysis revealed no gross differences after SLRP knockdown. However, a decrease in nuclear aspect ratio was found in the absence of biglycan compared to WT and I-Dcn−/−, indicating a more spindle-like nuclear shape (Fig. 7). No changes were seen in cellularity (not shown).

Figure 7 –

Nuclear aspect ratio decreased in the I-Bgn−/− group compared to WT and I-Dcn−/− groups.

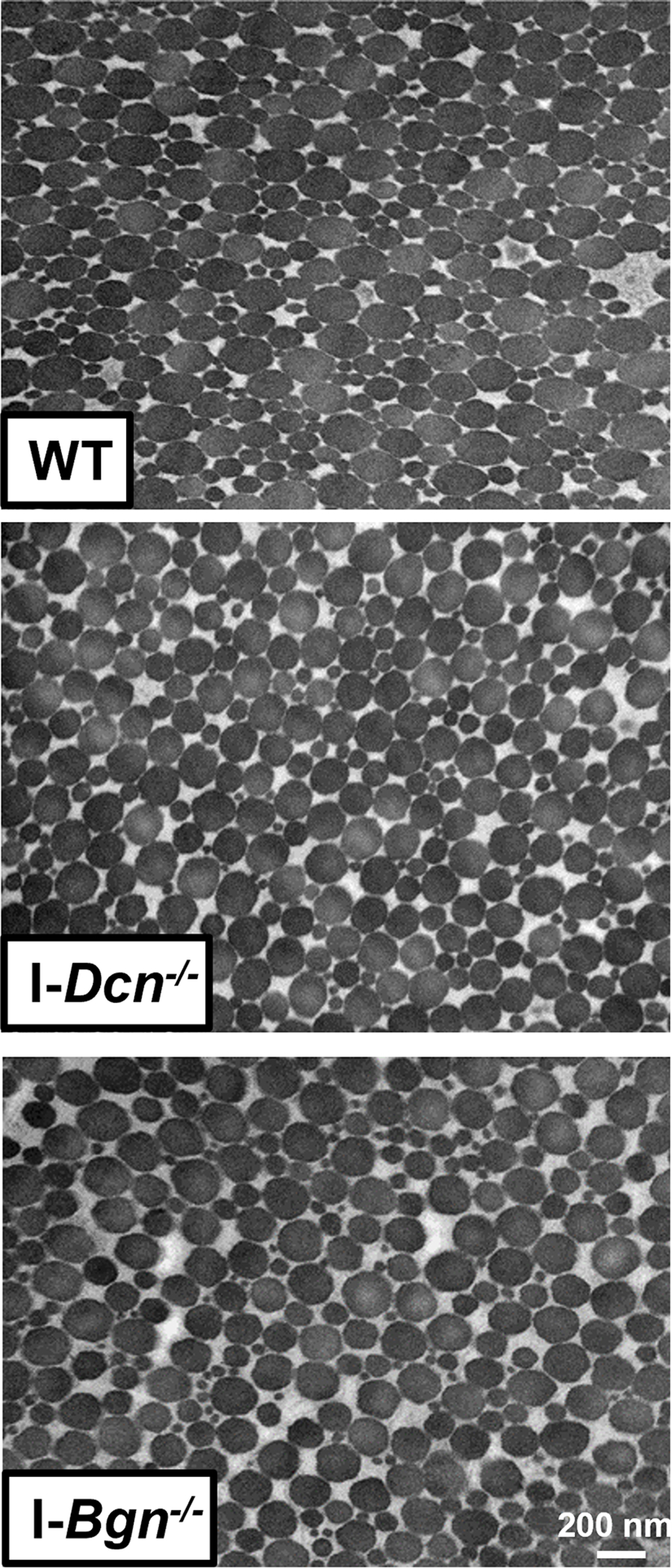

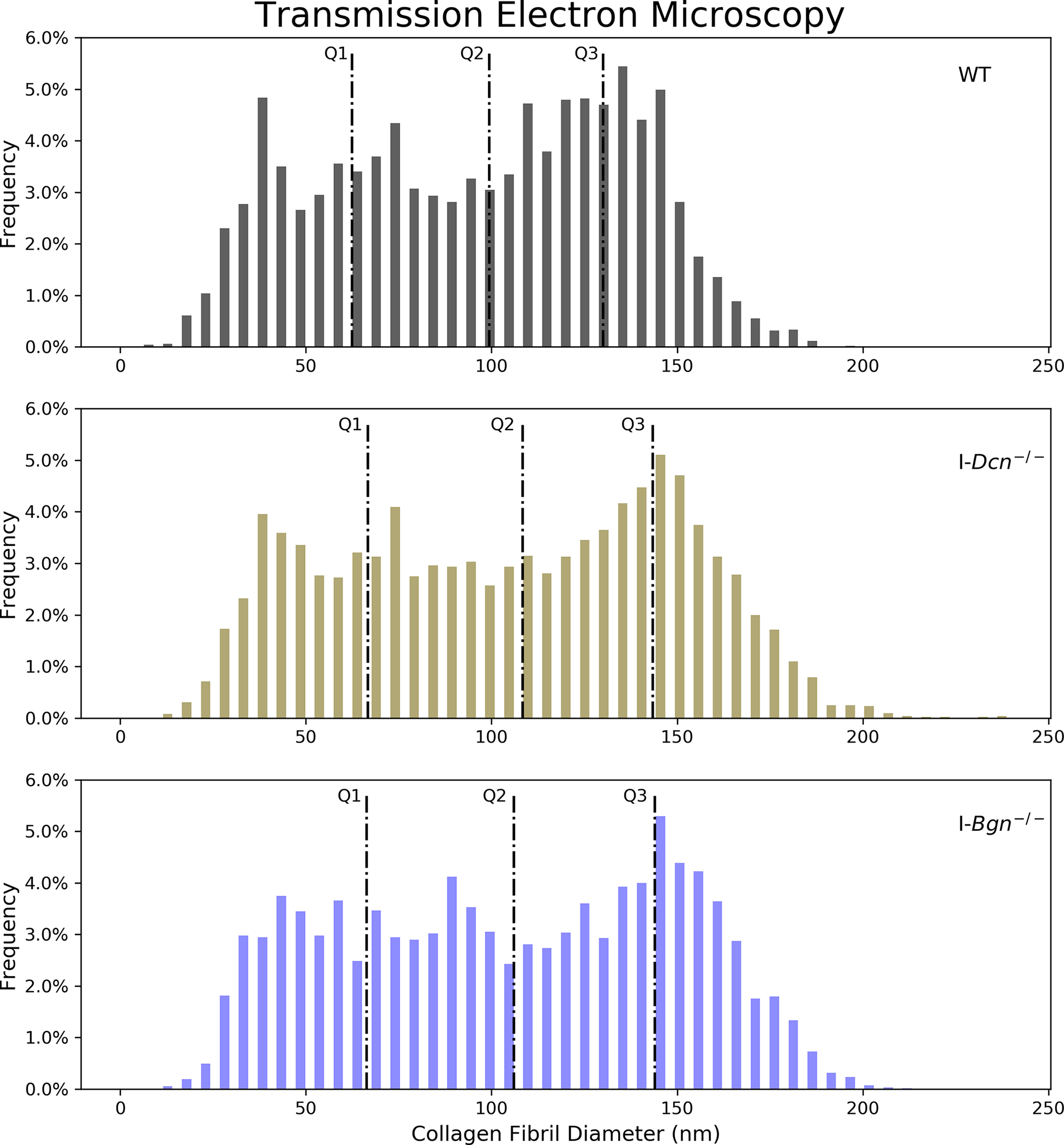

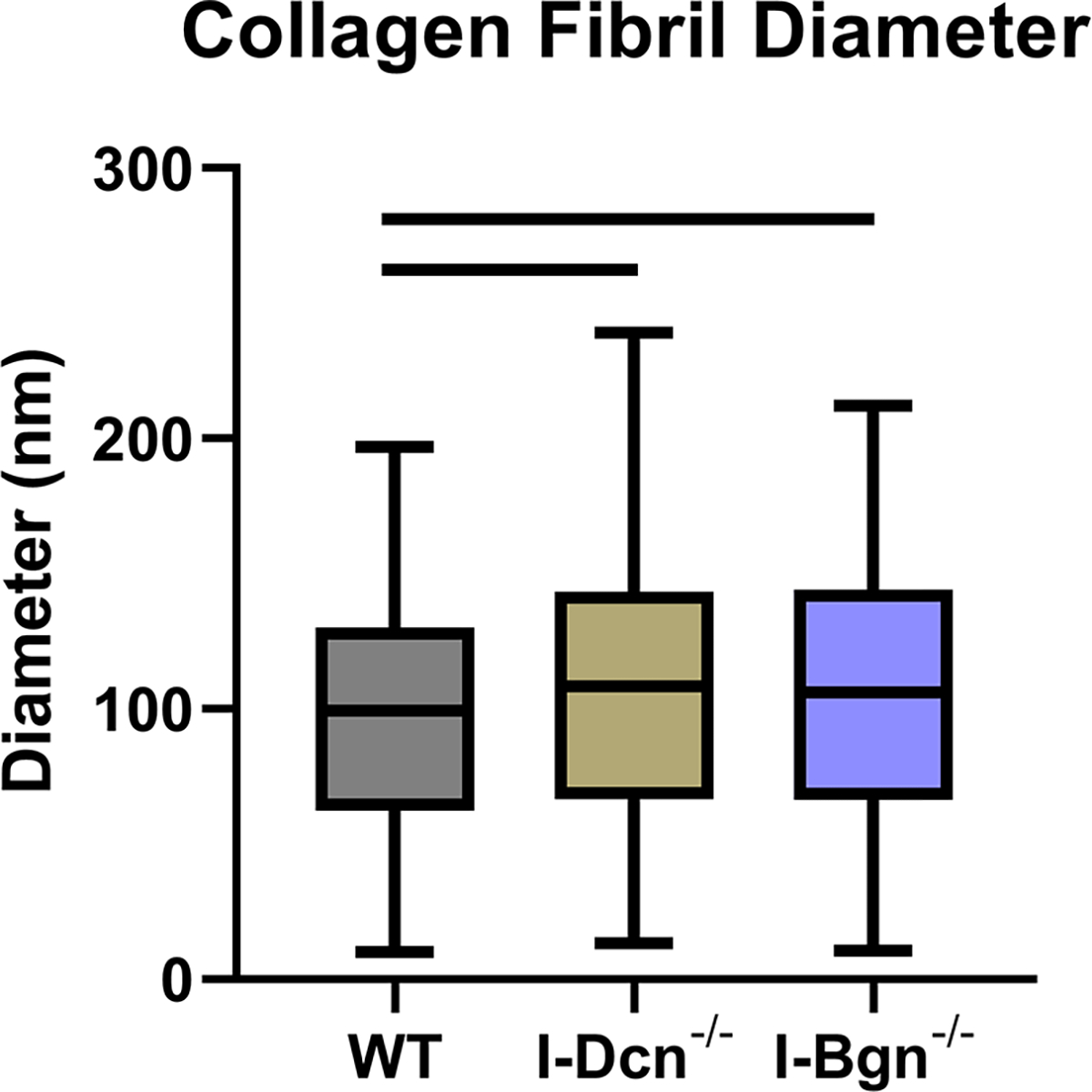

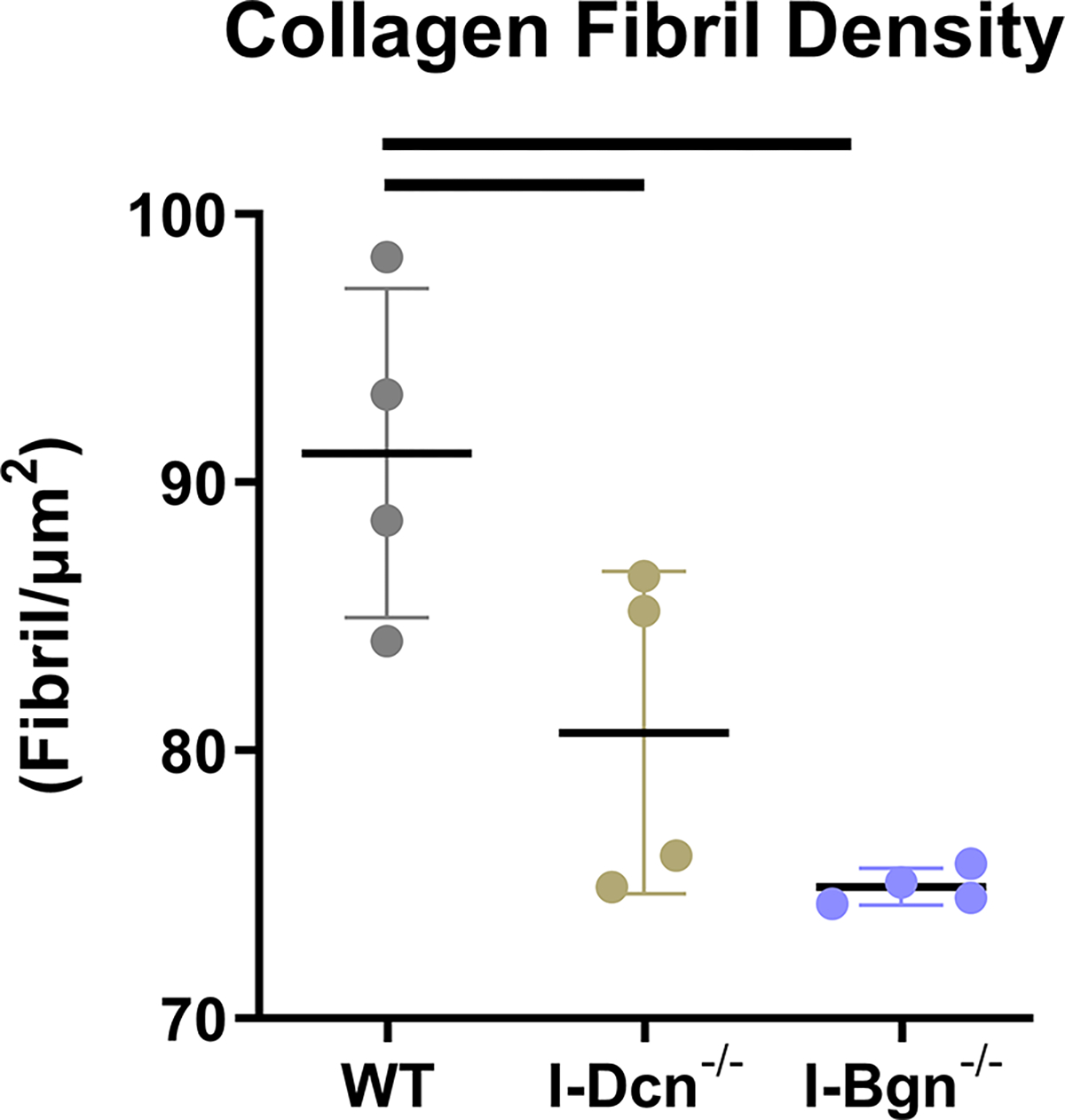

Transmission Electron Microscopy

Tendon collagen fibril diameters were measured 30 days after Cre induction in I-Dcn−/− and I-Bgn−/− and compared to controls using TEM. Overall collagen fibril structure was similar between WT, I-Dcn−/−, and I-Bgn−/− with circular cross-sectional profiles (Fig. 8A). However, I-Dcn−/− and I-Bgn−/− had increased fibril diameters compared to WT tendons (Fig. 8B and C). Median collagen fibril diameter was increased in I-Dcn−/− and I-Bgn−/− versus WT (108.4 nm, 106.0 nm, and 99.4 nm, respectively). Similar increases were found for quartiles 1 (66.7 nm, 66.4 nm, and 62.4 nm) and 3 (143.4 nm, 144.0 nm, and 130.1 nm). Collagen fibril density was also decreased in I-Dcn−/− and I-Bgn−/− compared to WT (Fig. 8D). Overall, the inducible knockdown groups had altered collagen fibril diameters with broader distributions versus WT, but the I-Dcn−/− and I-Bgn−/− distributions were comparable.

Figure 8 –

Transmission electron microscopy revealed increased collagen fibril diameter and decreased fibril density after SLRP knockdown. (A) All groups displayed circular cross-sectional collagen fibril profiles. (B) Knockdown of decorin and biglycan resulted in similar increases across all fibril diameter quartiles relative to WT, (C) resulting in an overall increase in collagen fibril diameter and (D) decrease in collagen fibril density.

Discussion

The objective of this study was to determine the regulatory roles of decorin and biglycan on tendon mechanics and structure during tendon homeostasis. We used TM-inducible models in skeletally mature mice to avoid the confounding variables associated with conventional knockouts that arise from undergoing development with altered expression. Similar to the present study, our previous work used a TM-inducible compound decorin/biglycan (I-Dcn−/−/Bgn−/−) knockdown mouse model to determine the regulatory roles of decorin and biglycan in maintaining structure and function in mature tendons.15 The I-Dcn−/−/Bgn−/− tendons revealed structural alterations compared to WT controls that occurred at the collagen fibril level, with a general increase across the entire fibril diameter distribution and a population of unusually large fibrils.15 These changes to I-Dcn−/−/Bgn−/− collagen fibril structure were similar to what was observed in conventional decorin-null tail tendons, which also produced a collagen fibril diameter distribution that was larger than WT across the entire distribution and included a population of unusually large fibrils.24,25 Due to the similarities in structural changes between I-Dcn−/−/Bgn−/− and decorin-null tendons we hypothesized that the I-Dcn−/−/Bgn−/− model may reflect the decorin-null phenotype. Since biglycan expression normally decreases after development17,24 we also hypothesized that decorin may be the primary regulator of tendon homeostasis at maturity while biglycan has either no regulatory role or a minor role. Based on these insights, in our present study we hypothesized that knockdown of decorin would result in detrimental alterations to tendon mechanics and structure, while biglycan knockdown would have no effect on these parameters.

The validity of our knockdown models was confirmed with substantial reductions in mRNA expression and protein content for decorin and biglycan in the I-Dcn−/− and I-Bgn−/− groups, respectively. No changes in gene expression were found in any of the fibril-associated class I or II SLRPs due to decorin or biglycan knockdown. This suggests that our I-Dcn−/− and I-Bgn−/− mice are effective models to study the regulatory roles of Dcn and Bgn in tendon since there are no compensatory upregulation of the class II SLRPs that have similarities in structure and function.

Contrary to our hypothesis, induced knockdown of decorin resulted in no changes to tendon mechanics. The only change to mechanics observed in I-Dcn−/− tendons was higher collagen realignment in the midsubstance between 3–5% strain compared to WT. Surprisingly, knockdown of biglycan resulted in broad changes to tendon mechanics. I-Bgn−/− tendons revealed changes to quasistatic and viscoelastic mechanics, with reductions in insertion modulus, maximum stress, dynamic modulus, and stress relaxation compared to WT. Collagen realignment of I-Bgn−/− tendons differed from the I-Dcn−/− tendons, with realignment occurring between 1%, 3%, and 5% strain and having a more aligned matrix from 5–9% strain in the midsubstance and insertion compared to WT and I-Dcn−/−. The collagen realignment observed in I-Bgn−/− tendons is analogous to the realignment demonstrated by I-Dcn−/−/Bgn−/− tendons, which also increased collagen realignment between 1%, 3%, and 5% strain and increased collagen fiber realignment from 5–9% strain compared to WT.15 There were further similarities between I-Bgn−/− and I-Dcn−/−/Bgn−/− tendons during dynamic loading, where both models produced a lower dynamic modulus compared to WT tendons at loading frequencies of 0.1, 1, 5, and 10 Hz.15 Overall, these data suggest that biglycan is playing an active regulatory role during tendon homeostasis that is comparable, if not more significant than, the role of decorin.

These results are surprising and in contrast to previous studies that showed conventional biglycan knockouts have little effect on tendon properties. Specifically, a previous study using conventional heterozygote and null biglycan knockout mice evaluated at 5 months of age demonstrated an increased dynamic modulus with no changes to quasistatic mechanics or fibril diameter.10 Conversely, knockout of decorin has previously revealed a greater effect on tendon mechanics including increased dynamic modulus, decreased phase shift, and increased stress relaxation.9 Another study examined decorin and biglycan knockout in mouse tail fascicles, patellar tendons, and flexor digitorum longus (FDL) tendons and found the results to be highly tendon dependent.14 Knockout of biglycan had no effect on quasistatic or viscoelastic properties in the tendon tail fascicle or patellar tendon, but a reduction in maximum stress and modulus was found in the FDL.14 Decorin knockout increased quasistatic mechanics in the patellar tendon and FDL and increased percent relaxation in the patellar tendon.14 The differential effects of decorin and biglycan knockout found in this study were attributed to differences in tendon location and function. Given the advantages of TM-inducible SLRP knockdown models including normal tendon development and no changes to SLRP expression, the data from the current study are likely more reliable to determine the effects of decorin and biglycan knockdown on tendon structure and mechanics than what has been described using traditional knockdown models.

The changes seen after knockdown of decorin and biglycan could also be due to tissue remodeling mediated by higher levels of TGF-β. Both decorin and biglycan can bind to TGF-β, which reduces TGF-β activity in the tissue. The inhibition of TGF-β via decorin and biglycan binding occurs in a dose-dependent manner, and the affinity to TGF-β is similar between decorin and biglycan.28 An increase in pro-fibrotic TGF-β-mediated tissue remodeling would be expected after knockdown of decorin or biglycan. However, given the high expression levels of decorin relative to biglycan in the tendon ECM, we would expect TGF-β activity to have a larger impact on the mechanics of I-Dcn−/− tendons than on the I-Bgn−/− tendons. It is possible that decorin or biglycan expression combined with fibromodulin is sufficient in preventing extensive remodeling by TGF-β since fibromodulin is more effective at sequestering TGF-β activity because of the ability to bind to both the active and latent forms of TGF-β.29

The structural changes associated with knockdown of decorin and biglycan were similar at the collagen fibril level with an increase in collagen fibril diameter and decreased collagen fibril density compared to WT. These changes to the tendon microstructure are likely due to the roles of decorin and biglycan in collagen fibrillogenesis. Decorin and biglycan play vital roles throughout the development of tendon structure, and this is attributed to the coordinate interactions between these two proteins during collagen fibrillogenesis. Knockout of decorin or biglycan has produced alterations to the collagen fibril diameter distribution and irregularly shaped fibrils that are maintained throughout adulthood. Additionally, decorin and biglycan play important roles in stabilizing mature collagen fibrils by preventing lateral fusion of smaller diameter fibrils. This study provides additional evidence that decorin and biglycan play vital roles in maintaining tendon microstructure in mature tissue.

Biglycan knockdown also produced surprising histology results. Previous studies showed an absence of changes to cellularity and nuclear shape with both decorin and biglycan knockout,15 while the inducible biglycan knockdown in the current study revealed decreased nuclear shape, which is associated with decreased cellular activity in tendon. A potential mechanism to explain the changes found in tendon after biglycan knockdown is the role of biglycan in maintaining the tendon stem/progenitor cell (TSPC) niche.26 TSPCs reside in a niche that is surrounded predominantly by ECM proteins. Evidence suggests that biglycan, and not decorin, plays a major role in the maintenance of this niche by regulating tendon progenitor differentiation, inflammation, and sequestering growth factors. Disruption of the TSPC niche using Bgn0/−Fmod−/− knockout mice resulted in an increase in the quantity of TSPCs and dysregulation in the balance of cytokines.26 Additonal evidence also suggests that disruption of the tissue niche in tendon can result in a switch from homeostasis to tissue degradation that is mediated by activation of the immune response, production of ROS, and activation proteolytic enzymes.27 A possible reason for the decreased mechanics observed in the I-Bgn−/− tendons is that knockdown of biglycan disrupted the tissue niche, which triggered a switch from homeostasis to a degenerative state.

This study is not without limitations. Our use of an inducible knockout model combined with the 30-day timeline does not ensure total knockout and clearance of the decorin and biglycan proteins. However, the tissue turnover rate of decorin and biglycan are approximately 18 days and 14 days, respectively, ensuring that this timeline is sufficient for reduced protein content in our models.30,31 This data is in agreement with the protein content data in this study. Additionally, this study examined a targeted set of markers, comprised of collagens and fibril associated SLRPs, while investigating the roles of decorin and biglycan in the maintenance of tendon structure and mechanics. Utilizing proteomics to capture all the protein content changes associated with decorin and biglycan knockdown would give a broader view of the molecular mechanisms at play. Finally, our histology results revealed changes in cellular phenotype because of biglycan knockdown. Future work analyzing various aspects of cellular behavior after knockdown of decorin or biglycan, for example cellular proliferation, senescence, apoptosis, and matrix production, would provide further insight into the roles of decorin and biglycan in cellular maintenance and signaling during homeostasis.

Our novel inducible I-Dcn−/− and I-Bgn−/− mouse models allowed for the analysis of decorin and biglycan knockdown in adult tendons without the confounding variables of SLRP knockout during development. Surprisingly, knockdown of biglycan resulted in alterations to tendon mechanics, and structure, while knockdown of decorin had no effects on mechanics and minor effects on tendon structure. This provides evidence against the idea that decorin plays the dominant role among SLRPs in tendon maintenance while biglycan has a minor modulatory role. Results from this study highlight the importance of TM-inducible models in evaluating the role of proteins in adult models. Future work will explore the effects of TM-inducible decorin and biglycan knockdown in aged tendons.

Acknowledgements

This material is based upon work supported by the NSF GRFP (DGE-1845298) and NIH/NIAMS (P30AR069619 and R01AR068057).

References

- 1.Taye N, Karoulias SZ, Hubmacher D. 2019. The “other” 15–40%: The Role of Non-Collagenous Extracellular Matrix Proteins and Minor Collagens in Tendon. J. Orthop. Res 38(1):23–35 [cited 2020 Jan 8] Available from: 10.1002/jor.24440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kjaer M 2004. Role of Extracellular Matrix in Adaptation of Tendon and Skeletal Muscle to Mechanical Loading. Physiol. Rev 84(2):649–698 Available from: 10.1152/physrev.00031.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhang G, Young BB, Ezura Y, et al. 2005. Development of tendon structure and function: Regulation of collagen fibrillogenesis. J. Musculoskelet. Neuronal Interact 5(1):5–21 [cited 2017 Aug 10] Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15788867. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Iozzo R V 1999. The biology of the small leucine-rich proteoglycans. Functional network of interactive proteins. J. Biol. Chem 274(27):18843–18846 [cited 2016 Aug 31] Available from: 10.1074/jbc.274.27.18843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Samiric T, Ilic MZ, Handley CJ. 2004. Characterisation of proteoglycans and their catabolic products in tendon and explant cultures of tendon. Matrix Biol 23(2):127–140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Casar JC, McKechnie BA, Fallon JR, et al. 2004. Transient up-regulation of biglycan during skeletal muscle regeneration: Delayed fiber growth along with decorin increase in biglycan-deficient mice. Dev. Biol 268(2):358–371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dunkman AA, Buckley MR, Mienaltowski MJ, et al. 2013. Decorin expression is important for age-related changes in tendon structure and mechanical properties. Matrix Biol 32(1):3–13 [cited 2016 Aug 26] Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23178232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhang G, Young BB, Ezura Y, et al. 2005. Development of tendon structure and function: Regulation of collagen fibrillogenesis. J. Musculoskelet. Neuronal Interact 5(1):5–21 [cited 2020 Dec 7] Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/15788867/. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dourte LM, Pathmanathan L, Jawad AF, et al. 2012. Influence of decorin on the mechanical, compositional, and structural properties of the mouse patellar tendon. J. Biomech. Eng 134(3):031005 [cited 2016 Jul 18] Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22482685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dourte LM, Pathmanathan L, Mienaltowski MJ, et al. 2013. Mechanical, compositional, and structural properties of the mouse patellar tendon with changes in biglycan gene expression. J. Orthop. Res 31(9):1430–1437 [cited 2017 Aug 10] Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23592048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gordon J, Freedman BR, Zuskov A, et al. 2015. Achilles tendons from decorin- and biglycan-null mouse models have inferior mechanical and structural properties predicted by an image-based empirical damage model. J. Biomech 48(10):2110–5 [cited 2016 Jul 13] Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25888014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Connizzo BK, Sarver JJ, Birk DE, et al. 2013. Effect of age and proteoglycan deficiency on collagen fiber re-alignment and mechanical properties in mouse supraspinatus tendon. J. Biomech. Eng 135(2):021019 [cited 2016 Aug 26] Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23445064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Elliott DM, Robinson PS, Gimbel JA, et al. 2003. Effect of altered matrix proteins on quasilinear viscoelastic properties in transgenic mouse tail tendons. Ann. Biomed. Eng 31(5):599–605 [cited 2018 Dec 6] Available from: 10.1114/1.1567282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Robinson PS, Huang T-F, Kazam E, et al. 2005. Influence of Decorin and Biglycan on Mechanical Properties of Multiple Tendons in Knockout Mice. J. Biomech. Eng 127(1):181 Available from: http://biomechanical.asmedigitalcollection.asme.org/article.aspx?articleid=1413750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Robinson KA, Sun M, Barnum CE, et al. 2017. Decorin and biglycan are necessary for maintaining collagen fibril structure, fiber realignment, and mechanical properties of mature tendons. Matrix Biol. [cited 2017 Sep 25] Available from: http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0945053X17301063?via%3Dihub. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhang G, Ezura Y, Chervoneva I, et al. 2006. Decorin regulates assembly of collagen fibrils and acquisition of biomechanical properties during tendon development. J. Cell. Biochem 98(6):1436–1449 [cited 2017 Aug 10] Available from: 10.1002/jcb.20776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ansorge HL, Adams SM, Birk DE, Soslowsky LJ. 2011. Mechanical, compositional and structural properties of the post-natal mouse Achilles tendon. Ann. Biomed. Eng 39(7):1904–1913 [cited 2016 May 17] Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21431455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dunkman AA, Buckley MR, Mienaltowski MJ, et al. 2014. The tendon injury response is influenced by decorin and biglycan. Ann. Biomed. Eng 42(3):619–630 [cited 2016 Jul 13] Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24072490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Favata M 2006. Scarless Healing in the Fetus: Implications and Strategies for Postnatal Tendon Repair.

- 20.Lake SP, Miller KS, Elliott DM, Soslowsky LJ. 2009. Effect of fiber distribution and realignment on the nonlinear and inhomogeneous mechanical properties of human supraspinatus tendon under longitudinal tensile loading. J. Orthop. Res 27(12):1596–1602 [cited 2016 May 31] Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19544524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Miller KS, Connizzo BK, Feeney E, Soslowsky LJ. 2012. Characterizing local collagen fiber re-alignment and crimp behavior throughout mechanical testing in a mature mouse supraspinatus tendon model. J. Biomech 45(12):2061–2065 [cited 2019 May 30] Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0021929012003387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Birk DE, Trelstad RL. 1986. Extracellular compartments in tendon morphogenesis: Collagen fibril, bundle, and macroaggregate formation. J. Cell Biol 103(1):231–240 [cited 2017 Aug 10] Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/3722266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Birk DE, Zycband EI, Woodruff S, et al. 1997. Collagen fibrillogenesis in situ: Fibril segments become long fibrils as the developing tendon matures. Dev. Dyn 208(3):291–298 [cited 2016 May 31] Available from: . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhang G, Ezura Y, Chervoneva I, et al. 2006. Decorin regulates assembly of collagen fibrils and acquisition of biomechanical properties during tendon development. J. Cell. Biochem 98(6):1436–1449 [cited 2017 Nov 10] Available from: 10.1002/jcb.20776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Corsi A, Xu T, Chen XD, et al. 2002. Phenotypic effects of biglycan deficiency are linked to collagen fibril abnormalities, are synergized by decorin deficiency, and mimic Ehlers-Danlos-like changes in bone and other connective tissues. J. Bone Miner. Res 17(7):1180–1189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bi Y, Ehirchiou D, Kilts TM, et al. 2007. Identification of tendon stem/progenitor cells and the role of the extracellular matrix in their niche. Nat. Med 13(10):1219–1227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wunderli SL, Blache U, Beretta Piccoli A, et al. 2020. Tendon response to matrix unloading is determined by the patho-physiological niche. Matrix Biol. 89:11–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kolb M, Margetts PJ, Sime PJ, Gauldie J. 2001. Proteoglycans decorin and biglycan differentially modulate TGF-β-mediated fibrotic responses in the lung. Am. J. Physiol. - Lung Cell. Mol. Physiol 280(6 24–6) [cited 2021 Dec 11] Available from: 10.1152/ajplung.2001.280.6.L1327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hildebrand A, Romaris M, Rasmussen LM, et al. 1994. Interaction of the small interstitial proteoglycans biglycan, decorin and fibromodulin with transforming growth factor beta. Biochem. J 302(Pt 2):527 [cited 2021 Dec 11] Available from: /pmc/articles/PMC1137259/?report=abstract. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Burton-Wurster N, Liu W, Matthews GL, et al. 2003. TGF beta 1 and biglycan, decorin, and fibromodulin metabolism in canine cartilage. Osteoarthr. Cartil 11(3):167–176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Blumberg P, Brenner R, Budny S, Kresse H. 1997. Increased turnover of small proteoglycans synthesized by human osteoblasts during cultivation with ascorbate and β-glycerophosphate. Calcif. Tissue Int 60(6):554–560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]