Abstract

Bacteriocin release protein is known to activate outer membrane phospholipase A (OMPLA), which results in the release of colicin from Escherichia coli. In vivo chemical cross-linking experiments revealed that the activation coincides with dimerization of OMPLA. Permeabilization of the cell envelope and dimerization were characterized by a lag time of 2 h.

Colicins are plasmid-encoded proteins produced by Escherichia coli and capable of killing E. coli and closely related species (18). Bacteriocin release protein (BRP) (also referred to as lysis protein) is a small lipoprotein that is essential for the release of colicin into the medium. BRP activates the endogenous outer membrane (OM) phospholipase (OMPLA) (6, 14, 20) which is important for the permeabilization of the cell envelope, since strains defective in the structural gene for OMPLA, pldA, do not release colicin. OMPLA is constitutively expressed, but enzymatic activity is detected in vivo only under adverse conditions (2, 7, 15, 17). Chemical cross-linking with formaldehyde suggested that OMPLA is present in whole cells in a monomeric state, whereas the dimeric form of the enzyme could be detected after sonication of the cells (10). We have shown in vitro that the monomeric state of OMPLA is inactive and that activation requires dimerization (10). In this study, we have investigated whether under physiologically relevant conditions activation of OMPLA involves dimerization.

The pACYC184-based plasmid pJL4 encodes chloramphenicol acetyltransferase (CAT) and contains the BRP gene from pCloDF13 of Enterobacter cloacae under control of the lpp/lac tandem promoter/operator (13). Plasmid pRB1 (4) contains the wild-type pldA gene under its own, constitutive promoter; pRB1-S144A (5) contains a pldA allele, which encodes an inactive S144A substitution mutant OMPLA. A 3,300-bp XmnI/NruI fragment of plasmid pMF20 (22), carrying the phoA gene encoding alkaline phosphatase (AP) under control of a constitutive, mutant promoter was subcloned into the unique HincII site of pRB1 and of pRB1-S144A, yielding plasmids pND19 and pND20, respectively. E. coli K-12 strain CE1303 (pldA recA56 [9]) transformed with pJL4 and either pND19 or pND20 was grown under agitation at 37°C in Luria broth supplemented with chloramphenicol (37 μg/ml) and ampicillin (50 μg/ml) and with 10 mM MgCl2 to prevent BRP-induced lysis (14, 20). When the optical density at 600 nm reached 0.3, 150 μM isopropyl-β-d-1-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) was added to induce BRP synthesis.

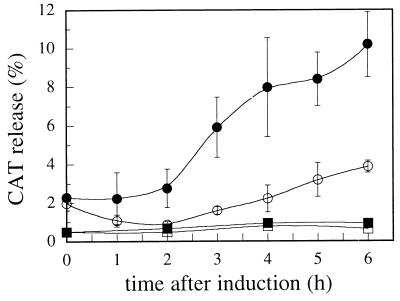

The permeabilization of the cell envelope was monitored by measuring the release of cytosolic CAT and of periplasmic AP into the medium. Measurement of CAT activity (23) revealed the presence of 1 to 2% of the total CAT activity in the medium before induction of BRP synthesis (Fig. 1). After induction, CAT activity in the medium increased to 10% of the total amount after a lag period of approximately 2 h (Fig. 1). This lag time is consistent with previous observations for the release of colicin E2 (20), cloacin DF13 (14) and marker enzymes (19). The release of CAT was dependent on the action of OMPLA, since it was much lower when an inactive mutant of OMPLA, in which the active-site serine was replaced by an alanine, was used (Fig. 1). However, also in the latter case, the levels of CAT in the supernatant were significantly higher than when BRP synthesis was not induced (Fig. 1), indicating that BRP alone is capable of a partial permeabilization of the cell envelope. Measurement of AP activity (26) revealed the presence of 5% of the total amount of AP produced in the medium when BRP synthesis was not induced. After induction of BRP synthesis, the release of AP increased to 27% of the total activity (data not shown). The release of AP was dependent on the activity of wild-type OMPLA and was again characterized by a lag time of 2 h (data not shown). These data show that periplasmic AP can enter the secretion pathway, suggestive of a sequential secretion process.

FIG. 1.

Release of CAT after induction of BRP synthesis. CE1303 cells containing pJL4 and either pND19 (wild-type OMPLA; filled circles) or pND20 (inactive mutant OMPLA; open circles) were induced with 150 μM IPTG at time zero. The release of CAT from the cells into the culture medium was monitored over time. The release is expressed as a percentage of enzyme activity present in the culture supernatant of the total enzyme activity determined after complete lysis of the culture by sonication. In control experiments, no IPTG was added (filled and open squares for wild-type and mutant OMPLA, respectively). The results are from three independent cultures, and standard deviations are indicated by the error bars.

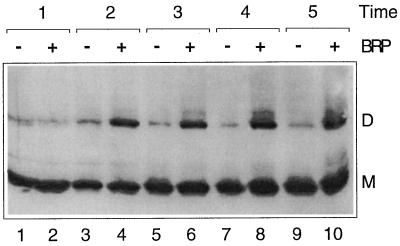

Dimerization of OMPLA was analyzed in vivo by chemical cross-linking with formaldehyde as described previously (10). Without induction of BRP synthesis, OMPLA was detected mostly as a monomeric species (Fig. 2, odd-numbered lanes). However, when BRP synthesis was induced, considerable amounts of dimer could be trapped (Fig. 2, lanes 4, 6, 8 and 10). The absence of dimeric cross-linking products before activation could be explained by the existence of OMPLA in a dimeric but cross-linking-incompetent state under normal conditions. However, when gluteraldehyde was used as a cross-linker with a longer spacer, dimers were also not observed (results not shown). Therefore, it is unlikely that OMPLA preexists in a dimeric state in the OM, although this possibility cannot be totally excluded. The dimerization of OMPLA was characterized by a considerable lag time, which correlates with the lag time observed for the release of CAT and AP into the medium. Moreover, it has been reported that the formation of lysophosphatidylethanolamine, the major hydrolysis product of the OMPLA-catalyzed reaction, is characterized by a similar lag time (6, 14, 20). BRP-induced dimerization was also detected for the inactive mutant OMPLA (data not shown).

FIG. 2.

In vivo cross-linking of OMPLA. CE1303 cells containing pJL4 and pND19 were grown either with (+) or without (−) IPTG to induce BRP synthesis. At several time points after the addition of IPTG (indicated in hours over the lanes), samples were collected, cross-linked, and analyzed on a gel. OMPLA was visualized by Western blotting with a monoclonal antibody and subsequent chemiluminescence detection (Renaissance Western blot ECL kit; DuPont). The positions of the monomer (M) and dimer (D) forms of OMPLA are indicated to the right of the gel.

What can we propose now for the molecular mechanism of BRP-mediated activation of OMPLA? The lag time of 2 h after induction of BRP expression before the onset of permeabilization of the cell envelope and dimerization of OMPLA is intriguing. Although the posttranslational processing of BRP is a slow process and takes minutes for completion (11), it is still rapid compared to the observed lag time. BRP is produced in large amounts up to 105 copies per cell (12), which are much larger than the small amounts of OMPLA present. Therefore, a specific, direct interaction between BRP and OMPLA is not very likely the direct trigger for activation. Diffusion rates within the OM are very low (25) due to the interactions between the negatively charged lipopolysaccharide molecules, which are interconnected via Mg2+- or Ca2+-mediated salt bridges and via hydrophobic interactions between the lipid A parts (16). The low diffusion rate together with the low abundance of the protein (380 copies per cell [21]) might normally prevent the dimerization of OMPLA. The incorporation of BRP in the OM could destabilize the membrane, especially if the localization is restricted to one leaflet (24). Such action correlates with our finding that, although with reduced efficiency, BRP alone is capable of permeating the OM. Morphological changes induced by BRP have been observed as blebs in the OM (27). Furthermore, low-level expression of the pColE1 BRP causes partial exfoliation of the OM (1). One can envisage that the BRP-mediated membrane perturbation relieves the lipid asymmetry of the OM and accelerates diffusion in the OM, thereby triggering OMPLA activation. In our model, we assume a uniform distribution of monomeric OMPLA within the OM. Recently, a method for the specific in vivo labeling of cysteine residues in the OM protein FhuA has been reported (3). The labeling of single-cysteine mutants of OMPLA with fluorescent probes could provide insight in the distribution of OMPLA over the cell surface, and we are currently investigating this possibility. Once activated, the enzyme will generate fatty acid and, more importantly, lysophospholipid, a compound known to destabilize membranes (8). The water solubility of lysophospholipid is likely sufficient to permit transport to the cytoplasmic membrane. The presence of large amounts of BRP and lysophospholipid in both membranes could allow for the direct transport of colicins and reporter enzymes through these membranes in a sequential manner.

Acknowledgments

We thank B. Oudega for the generous gift of plasmid pJL4 and for useful discussions.

REFERENCES

- 1.Aono R. Envelope alteration of Escherichia coli HB101 carrying pEAP31 caused by Kil peptide and its involvement in the extracellular release of periplasmic penicillinase from an alkaliphilic Bacillus. Biochem J. 1991;275:545–553. doi: 10.1042/bj2750545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Audet A, Nantel G, Proulx P. Phospholipase A activity in growing Escherichia coli cells. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1974;348:334–343. doi: 10.1016/0005-2760(74)90213-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bös C, Lorenzen D, Braun V. Specific in vivo labeling of cell surface-exposed protein loops: reactive cysteine in the predicted gating loop mark a ferrichrome binding site and a ligand-induced conformational change of the Escherichia coli FhuA protein. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:605–613. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.3.605-613.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brok R G P M, Brinkman E, van Boxtel R, Bekkers A C A P A, Verheij H M, Tommassen J. Molecular characterization of enterobacterial pldA genes encoding outer membrane phospholipase A. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:861–870. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.3.861-870.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brok R G P M, Ubarretxena Belandia I, Dekker N, Tommassen J, Verheij H M. Escherichia coli outer membrane phospholipase A: role of two serines in enzymatic activity. Biochemistry. 1996;35:7787–7793. doi: 10.1021/bi952970i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cavard D, Baty D, Howard S P, Verheij H M, Lazdunski C. Lipoprotein nature of the colicin A lysis protein: effect of amino acid substitutions at the site of modification and processing. J Bacteriol. 1987;169:2187–2194. doi: 10.1128/jb.169.5.2187-2194.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cronan J E J, Wulff D L. A role for phospholipid hydrolysis in the lysis of Escherichia coli infected with bacteriophage T4. Virology. 1969;38:241–246. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(69)90365-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cullis P R, de Kruijff B. Lipid polymorphism and the functional role of lipids in biological membranes. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1979;559:399–420. doi: 10.1016/0304-4157(79)90012-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.de Geus P, van Die I, Bergmans H, Tommassen J, de Haas G. Molecular cloning of pldA, the structural gene for outer membrane phospholipase of E. coli K12. Mol Gen Genet. 1983;190:150–155. doi: 10.1007/BF00330338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dekker N, Tommassen J, Lustig A, Rosenbusch J P, Verheij H M. Dimerization regulates the enzymatic activity of outer membrane phospholipase A. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:3179–3184. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.6.3179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Howard S P, Lindsay L. In vivo analysis of sequence requirements for processing and degradation of the colicin A lysis protein signal peptide. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:3026–3030. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.12.3026-3030.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Luirink J, Clark D M, Ras J, Verschoor E J, de Graaf F K, Oudega B. pCloDF13-encoded bacteriocin release proteins with shortened carboxyl-terminal segments are lipid modified and processed and function in release of cloacin DF13 and apparent host cell lysis. J Bacteriol. 1989;171:2673–2679. doi: 10.1128/jb.171.5.2673-2679.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Luirink J, de Graaf F, Oudega B. Uncoupling of synthesis and release of cloacin DF13 and its immunity protein by Escherichia coli. Mol Gen Genet. 1987;206:126–132. doi: 10.1007/BF00326547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Luirink J, van der Sande C, Tommassen J, Veltkamp E, de Graaf F K, Oudega B. Effects of divalent cations and of phospholipase A activity on excretion of cloacin DF13 and lysis of host cells. J Gen Microbiol. 1986;132:825–834. doi: 10.1099/00221287-132-3-825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Michel G P F, Stárka J. Phospholipase A activity with integrated phospholipid vesicles in intact cells of an envelope mutant of Escherichia coli. FEBS Lett. 1979;108:261–265. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(79)81224-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nikaido H. Outer membrane. In: Neidhardt F C, Curtiss III R, Ingraham J L, Lin E C C, Low K B, Magasanik B, Reznikoff W S, Riley M, Schaechter M, Umbarger H E, editors. Escherichia coli and Salmonella: cellular and molecular biology. 2nd ed. Washington, D.C: American Society for Microbiology; 1996. pp. 29–47. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Patriarca P, Beckerdite S, Elsbach P. Phospholipases and phospholipid turnover in Escherichia coli spheroplasts. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1972;260:593–600. doi: 10.1016/0005-2760(72)90008-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pugsley A P. The ins and outs of colicins. Part I. Production and translocation across membranes. Microbiol Sci. 1984;1:168–175. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pugsley A P, Rosenbusch J P. Release of colicin E2 from Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1981;147:186–192. doi: 10.1128/jb.147.1.186-192.1981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pugsley A P, Schwartz M. Colicin E2 release: lysis, leakage or secretion? Possible role of a phospholipase. EMBO J. 1984;3:2393–2397. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1984.tb02145.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Scandella C J, Kornberg A. A membrane-bound phospholipase A1 purified from Escherichia coli. Biochemistry. 1971;10:4447–4456. doi: 10.1021/bi00800a015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Scholten, M., R. van Boxtel, and J. Tommassen. Unpublished results.

- 23.Shaw W V. Chloramphenicol acetyltransferase from chloramphenicol-resistant bacteria. Methods Enzymol. 1975;43:737–755. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(75)43141-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sheetz M P, Singer S J. Biological membranes as bilayer couples. A molecular mechanism of drug-erythrocyte interactions. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1974;71:4457–4461. doi: 10.1073/pnas.71.11.4457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Smit J, Nikaido H. Outer membrane of gram-negative bacteria. XVIII. Electron microscopic studies on porin insertion sites and growth of cell surface of Salmonella typhimurium. J Bacteriol. 1978;135:687–702. doi: 10.1128/jb.135.2.687-702.1978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tommassen J, Lugtenberg B. Outer membrane protein e of Escherichia coli K-12 is co-regulated with alkaline phosphatase. J Bacteriol. 1980;143:151–157. doi: 10.1128/jb.143.1.151-157.1980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.van der Wal F J, Luirink J, Oudega B. Bacteriocin release proteins: mode of action, structure, and biotechnological application. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 1995;17:381–399. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.1995.tb00221.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]