Abstract

Multi-drug resistance has called for a race to uncover alternatives to existing antibiotics. Phage therapy is one of the explored alternatives, including the use of endolysins, which are phage-encoded peptidoglycan hydrolases responsible for bacterial lysis. Endolysins have been extensively researched in different fields, including medicine, food, and agricultural applications. While the target specificity of various endolysins varies greatly between species, this current review focuses specifically on streptococcal endolysins. Streptococcus spp. causes numerous infections, from the common strep throat to much more serious life-threatening infections such as pneumonia and meningitis. It is reported as a major crisis in various industries, causing systemic infections associated with high mortality and morbidity, as well as economic losses, especially in the agricultural industry. This review highlights the types of catalytic and cell wall-binding domains found in streptococcal endolysins and gives a comprehensive account of the lytic ability of both native and engineered streptococcal endolysins studied thus far, as well as its potential application across different industries. Finally, it gives an overview of the advantages and limitations of these enzyme-based antibiotics, which has caused the term enzybiotics to be conferred to it.

Keywords: endolysins, streptococci, phages, enzybiotic, antibiotic alternative

Introduction

The unfortunate development of antibiotic-resistant strains is a natural phenomenon and is further exacerbated following the misuse and overuse of antibiotics, especially in the medical and agricultural industries (Roach and Donovan, 2015). As a result, antimicrobial resistant (AMR) pathogen-associated hospital-acquired infections caused by AMR strains have killed 99,000 people annually in the United States and are expected to kill 10 million people worldwide by 2050 (Aslam et al., 2018). The release of non-metabolized antibiotics or residues into the environment through feces can also accelerate the emergence of multidrug resistance (MDR) and AMR bacterial infections in society (Aslam et al., 2018; Alves-Barroco et al., 2020). Many bacterial infections are no longer treatable by common antibiotics (Prestinaci et al., 2015). In recent years, outbreaks of AMR bacterial infections, including Streptococcus spp., toward multiple antibiotics have been reported as a major crisis not only in the healthcare sector but also in agriculture and aquaculture industries.

Streptococcus spp. are Gram-positive, facultative anaerobes, non-motile, non-spore-forming, and oxidase-negative with either α-, β-, or non-hemolytic (γ) disposition (Pradeep et al., 2016; Renzhammer et al., 2020). Streptococcus spp. are classified by the expression of different Lancefield antigens found on the cell wall. Lancefield grouping is the traditional method which subdivides Streptococcus genus into 20 groups based on the presence of polysaccharides and teichoic acid antigens on the cell wall (Slater, 2007; Efstratiou et al., 2017). Among the groups, both group A Streptococcus (GAS) and group B Streptococcus (GBS) are the most prevalent human pathogens that cause systemic infections associated with high mortality and morbidity (van Hensbergen et al., 2018). Streptococcus pyogenes, which is a GAS bacterium, infects at least 700 million individuals each year, with a mortality rate of 15–30%, resulting in meningitis, toxic shock syndrome, and pharyngitis (Zorzoli et al., 2019). Streptococcus agalactiae, a GBS bacterium which is found in the human intestinal and urogenital tract microbiota, is frequently associated with post-cesarean surgical wound infection in pregnant women and infant meningitis (Haenni et al., 2018; Bobadilla et al., 2021). Streptococcus pneumoniae, on the other hand, is the major cause of meningitis and many different pulmonary infections, including sepsis (Jiang et al., 2018; Weiser et al., 2018). In the aquaculture industry, Streptococcus iniae and S. agalactiae have been identified as the most common pathogen associated with streptococcosis outbreaks, resulting in substantial economic losses (Pradeep et al., 2016; Osman et al., 2017). Streptococcus dysgalactiae subspecies equisimilis and Streptococcus suis infections in weaned piglets commonly cause pneumonia or meningitis, thus resulting in increased mortality rates and significant financial losses (Renzhammer et al., 2020).

To reduce the emergence of AMR bacterial strains, phage therapy has been extensively researched as an alternative treatment to bacterial infections. Phage therapy, also known as bacteriophage therapy, was once used to treat bacterial infections in the early 20th century (Duzgunes et al., 2021). However, the popularity of phage therapy was quickly shadowed by the discovery and development of penicillin and other broad-spectrum antibiotics (Murray et al., 2021). Following the discovery of penicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in the 1950s and methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA) in the 1960s, researchers started looking for antimicrobial alternatives (Guo et al., 2020). Due to the rise of AMR, phage therapy, which includes the use of phage lytic proteins such as endolysins, has become a popular research area as a viable antibiotic alternative. Endolysins or lysins were first described in the lysates of S. aureus in the early 1960s (Fischetti, 2018). They are phage-encoded peptidoglycan hydrolases responsible for degrading the peptidoglycan cell wall to release new phage progenies at the end of a phage lytic cycle (Roach and Donovan, 2015). Degradation of the peptidoglycan cell wall disrupts the osmotic balance between cellular and environmental osmotic pressure, resulting in cell lysis and death (Roach and Donovan, 2015; Murray et al., 2021). Due to its high specificity in targeting specific bonds in the peptidoglycan cell wall, endolysins have also been extensively used in various fields, for example, as a natural antibacterial agent in food preservation (Drulis-Kawa et al., 2015; Chang, 2020), as a protein-based narrow-spectrum disinfectant (Hoopes et al., 2009), and a topical skin application that targets MRSA (Totté et al., 2017).

At present, researchers have identified and tested many endolysins to establish their potential as new antimicrobial alternatives. However, no clinical trials involving endolysins targeting Streptococcus spp. have been conducted due to the lack of in vivo studies (Abdelkader et al., 2019; Abdelrahman et al., 2021). This review aims to discuss the different types of endolysins that target Streptococcus spp. and their current applications in different industries.

Endolysin structure

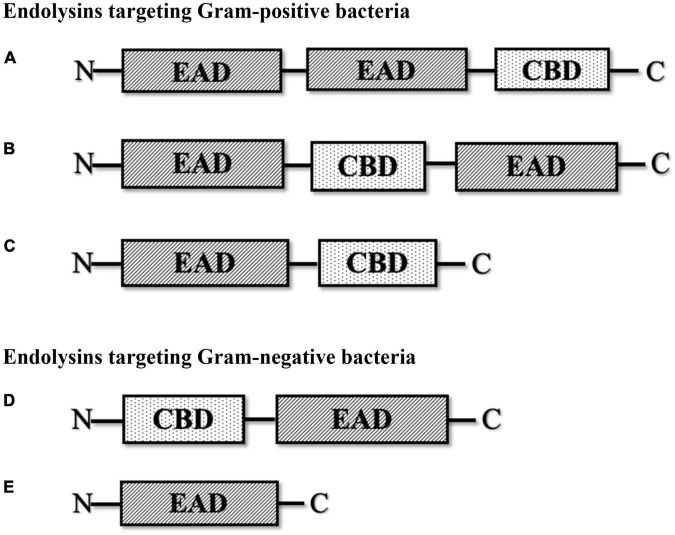

Endolysins are hydrolytic enzymes that can specifically identify and cleave the bacterial peptidoglycan cell wall. Most endolysins comprise a single polypeptide chain, usually greater than 25 kDa, and are composed of an N-terminal enzymatically active domain (EAD) and a C-terminal cell wall-binding domain (CBD), which are linked by a short flexible linker (Figure 1; Zhou et al., 2020). Endolysins are produced and expressed at the end of the phage lytic cycle, releasing phage progeny following degradation of the bacterial peptidoglycan cell wall (Chang, 2020; Zhou et al., 2020). Most endolysins pass through the cell wall with the help of holin proteins, which are small hydrophobic hole-forming proteins. Holin proteins trigger an opening on the cytoplasmic side and allow endolysins to hydrolyze the cell wall (Lin et al., 2017; Abdelrahman et al., 2021; Murray et al., 2021). However, some endolysins possess N-terminal signal peptides and are secreted without the help of holins, while the filamentous phage releases new progenies with an entirely different mechanism that does not lyse or kill the host cells (Schmelcher et al., 2012). The bacterial cell wall, which is made up of chains of N-acetylmuramic acid (MurNAc) and N-acetyl-D-glucosamine (GlcNAc) linked by glycosidic bonds (Vazquez et al., 2018; Dörr et al., 2019), regulates osmotic pressure and prevents the undesired passage of molecules (Dik et al., 2017; Dörr et al., 2019). The peptidoglycan cell wall of Gram-positive bacteria is multilayered, while that of Gram-negative bacteria is mono- or bilayered (Dik et al., 2017) and additionally possesses an outer membrane. Thus, in Gram-positive cells, endolysins can lyse peptidoglycan from the outside of the cell if applied externally, a phenomenon termed “lysis-from-without” as opposed to “lysis-from-within” (Schmelcher et al., 2012). The outer membrane of Gram-negative bacteria usually prevents endolysins from lysis-from-without, unless the endolysin has been engineered with outer membrane-permeabilizing peptides, such as in the case of artilysins (Schmelcher et al., 2012).

FIGURE 1.

Schematic structure of various types of phage-encoded peptidoglycan hydrolases (endolysin). (A) Multi-domain endolysin with more than one enzymatically active domain (EAD) and one C-terminal cell wall-binding domain (CBD). (B) Multi-domain endolysin with a centrally located CBD separating two EADs, found in Streptococcus phage (λSa2). (C) Endolysin with an N-terminal EAD and a C-terminal CBD, another common structure of endolysin, mostly found in streptococcal endolysins and phages infecting Listeria, Clostridium, and Bacillus. (D) Endolysin with an N-terminal CBD and a C-terminal EAD, found in some Pseudomonas phages (KZ114 and EL188). (E) Globular endolysin with only one EAD, found in most Gram-negative phages.

Endolysins targeting Gram-positive bacteria are generally composed of multiple domains, typically one or more enzymatically active domains (EADs) at the N terminus and a CBD at the C terminus. On the other hand, endolysins targeting Gram-negative bacteria are usually small single-domain globular proteins that only consist of EADs (Broendum et al., 2018; Chang, 2020; Murray et al., 2021). However, some Gram-negative endolysins also contain a CBD at the N terminus, such as Pseudomonas endolysin KZ144 (Chang, 2020) and endolysin EL188 (Walmagh et al., 2012). EADs are responsible for the hydrolytic degradation of cell walls, while CBDs are responsible for the endolysin recognition and binding specificity toward the bacterial cell wall (Ajuebor et al., 2016; Broendum et al., 2018).

To date, several CBDs have been described, including the lysin motif domain (LysM), bacterial Src homology 3 domain (SH3b), choline-binding domain, and Cpl-7-like CBD which is also known as CW-7 repeats (Bustamante et al., 2017; Chang and Ryu, 2017; Mitkowski et al., 2019; Muraosa et al., 2019). SH3b domains are present and well conserved in many staphylococcal phage endolysins. It has also been shown to bind and recognize glycine cross-bridges for most staphylococci (Chang and Ryu, 2017; Mitkowski et al., 2019). LysM domains were first found in the C terminus of a bacteriophage lysozyme which binds to GlcNAc residues in the cell wall peptidoglycan but has since been described in various prokaryotic and eukaryotic proteins including both bacterial and fungal proteins (Muraosa et al., 2019). The choline-binding domain is mostly found in pneumococcal phages like Cpl-1 and Pal. It consists of six tandem repeats of approximately 20 amino acids that share high homology with the choline-binding motif, LytA (Hermoso et al., 2003). The Cpl-7-like CBD was named after the Cpl-7 endolysin, which contains a CBD that is made of three identical repeats of 42 amino acid residues. It recognizes the GlcNAc-MurNAc-L-Ala-D-isoGln muropeptide in the cell wall and can also hydrolyze pneumococcal cell walls that contain choline or ethanolamine (Bustamante et al., 2012, 2017). Unlike the choline-binding domain, which is exclusively found in pneumococcal proteins and pneumococcal phage proteins, the Cpl-7-like CBD is also found in phages infecting other species, like S. agalactiae and S. suis (Pritchard et al., 2007; Wang et al., 2009). Due to the CBD recognition and binding specificity, endolysins that target Gram-positive bacteria tend to have a narrow host range compared to Gram-negative lysins (Ajuebor et al., 2016; Broendum et al., 2018; Murray et al., 2021). Its target specificity range can vary from the entire bacterial genus to a specific bacterial strain, making it a potential antibiotic alternative (Broendum et al., 2018). Although some endolysins can also lyse across genus, these are not as common (Gilmer et al., 2013).

Endolysins can be further subclassified into five different subgroups depending on the cleavage site of the peptidoglycan cell wall by the EADs (Ajuebor et al., 2016; Chang, 2020; Zhou et al., 2020). These subgroups are (a) lysozyme (N-acetylmuramidases), (b) glycosidases (N-acetyl-β-D-glucosamidases), (c) amidases (N-acetylmuramoyl-L-alanine), (d) endopeptidases (L-alanoyl-D-glutamate), and (e) lytic transglycosylases (Ajuebor et al., 2016; Chang, 2020; Zhou et al., 2020; Murray et al., 2021).

Lytic transglycosylases are non-hydrolytic enzymes that cleave the glycosidic bond of the peptidoglycan cell wall to form 1,6-anhydro-N-acetylmuramic acid (1,6-anhydroMurNAc) and GlcNAc. On the other hand, lysozymes are hydrolytic enzymes that cleave the same glycosidic bond using a different cleavage mechanism to form MurNAc and GlcNAc (Dik et al., 2017; Broendum et al., 2018; Byun et al., 2018; Jenkins et al., 2019). Amidases, also known as peptidoglycan amidases, are involved in the cleavage of amide bonds between N-acetylmuramic acid and L-alanine, separating the glycan strand from the stem peptide (Ajuebor et al., 2016; Broendum et al., 2018; Vermassen et al., 2019). Glycosidases, also known as glycoside hydrolases, cleave the glycan bond at the reducing side of GlcNAc (Broendum et al., 2018; Vermassen et al., 2019). Last, endopeptidases target and cleave the dipeptide-binding motif consisting of L-lysine and D-alanine links (Vermassen et al., 2019; Murray et al., 2021).

Sources and isolation of streptococcal endolysins

Streptococcal endolysins are encoded by streptococcal lytic or temperate phages, which exist naturally in the environment. Most reported streptococcal endolysins were either isolated and purified directly from the crude lysate of phage culture that shows lytic activity toward the host or from recombinant Escherichia coli that expresses cloned phage endolysins such as the PlyC endolysin. This endolysin was isolated and purified from the culture of phage C1, the first streptococcal Podoviridae isolated from a sewage plant (Nelson et al., 2001, 2003). PlyC exhibited lytic activity against groups A (S. pyogenes), C, and E Streptococcus with the strongest killing activity against group A Streptococcus (Nelson et al., 2001). The pneumococcal endolysin Pal was isolated from a CsCl density gradient centrifugation fraction of Dp-1 phage lysate that showed killing activity toward S. pneumoniae (Garcia, 1983). The Dp-1 phage was isolated from the throat of patients with upper respiratory disease similar to another pneumococcal phage Cp-1 (McDonnell et al., 1975; Ronda et al., 1981). Unlike Pal, the endolysin encoded by Cp-1 phage (Cpl-1) was isolated by cloning a DNA fragment of Cp-1, which showed similarity with the host autolysin LytA, into E. coli which produced a functional endolysin against S. pneumoniae (Garcia et al., 1987, 1988). S. pneumoniae is one of the major causes of pneumonia, meningitis, and sepsis in the respiratory tract, spinal fluid, and bloodstream, respectively. Therefore, the use of purified endolysins to treat pneumococcal infections is warranted due to an increasing trend of antimicrobial resistance (Jado et al., 2003; Hauser et al., 2012). Similarly, the recombinant endolysin gene from S. suis lytic phage SMP termed LySMP reportedly killed multiple strains of S. suis. The SMP phage was isolated from nasal swabs of Bama minipigs (Wang et al., 2009). Recently, two streptococcal endolysins 23TH_48 and SA01_53 were isolated using a similar approach, where the whole phage DNA of S. infantis 23TH siphovirus and S. anginosus SA01 siphovirus were sequenced, and the endolysin genes were cloned into E. coli. SA01_53 was found to lyse only its host target, while 23TH_48 exhibited a broader host range, which includes S. pneumoniae, thus making it a promising candidate to treat pneumococcal infections, in addition to Cpl-1 and Pal (van der Kamp et al., 2020).

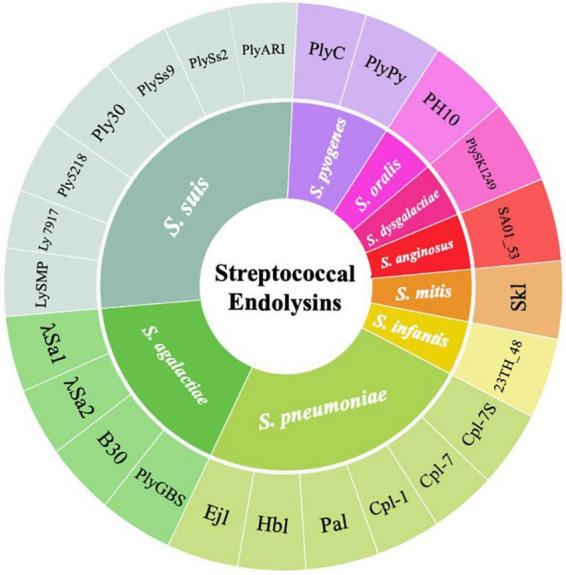

Many other streptococcal endolysin genes were also identified and cloned from temperate streptococcal phages. Temperate phages can be isolated via induction with mitomycin C and other inducers, or discovered by bioinformatics analysis that predicts the presence of prophage in the host genome. For example, the pneumococcal endolysins Hbl and Ejl were isolated from temperate phages, Siphoviridae HB-3 and Myoviridae EJ-1, obtained from mitomycin C-induced pneumococcal cultures (Bernheimer, 1979; Garcia et al., 1997). Similarly, PlyGBS and B30 endolysins were isolated from GBS temperate phages from screening multiple GBS strains induced by mitomycin C (Pritchard et al., 2004; Cheng et al., 2005). Despite the wide use of mitomycin C to induce temperate phages into its lytic cycle, a huge number of streptococcal temperate phages were not able to turn on the lytic cycle when exposed to this compound (Domelier et al., 2009). Therefore, various streptococcal endolysins were identified by analyzing the presence of integrase and phage-related genes in the host genome. This indicated the presence of temperate phages, followed by subsequently elucidating its putative endolysins using bioinformatics approaches. Such candidate gene products were cloned into E. coli for expression and tested for their lytic activity in vitro and in vivo. This approach was used to obtain the PlyPy endolysin from S. pyogenes, PlySK1249 from S. dysgalactiae, λSa1 and λSa2 from S. agalactiae, Skl from S. mitis, and PlySs2 and PlySs9 from S. suis serotypes 2 and 9 (Nelson et al., 2001; Llull et al., 2006; Gilmer et al., 2013; Oechslin et al., 2013; Lood et al., 2014; Vander Elst et al., 2020). An overall classification of streptococcal endolysins reported to date and their corresponding streptococcal species targets are summarized in Figure 2.

FIGURE 2.

Wheel diagram summary depicting the classification of streptococcal endolysins reported to date and their corresponding streptococcal species targets.

Enzymatically active domain and cell wall-binding domain of Streptococci-specific endolysins

Endolysins targeting Streptococcus species are unique due to the distinct types, numbers, and organization of EADs and CBDs (Table 1). These differences largely determine the strength and spectrum of the enzyme. Typically, the N-terminal domain consists of the EAD, and the C-terminal domain contains the CBD. However, some endolysins have an EAD at both N- and C-terminal domains with their CBD in the middle of the protein (Lood et al., 2014). Several endolysins hold more than one EAD, such as amidase, endopeptidase, and glycosidase domains, while others only have one EAD (Pritchard et al., 2007; McGowan et al., 2012; Vander Elst et al., 2020).

TABLE 1.

Streptococcal phage lysin and their origin, host range, enzymatically active domains (EADs), and cell wall-binding domains (CBDs).

| Phage origin | Endolysin | Host range | Enzymatically active domain | Cell wall-binding domain | References |

| S. agalactiae | B30 | Group A, B, C, E, G streptococcus |

N-terminal CHAP endopeptidase Middle Lysozyme |

C-terminal Putative SH3b |

Pritchard et al., 2004 |

| PlyGBS | GBS serotypes Ia, Ib, II, IIR, III, IIIR, V, GAS, GCS, GGS, GLS |

N-terminal CHAP endopeptidase Middle Lysozyme |

C-terminal Putative CBD |

Cheng et al., 2005 | |

| λSa1 | S. agalactiae, S. pneumoniae, S. aureus |

N-terminal Endopeptidase |

C-terminal SH3b |

Pritchard et al., 2007 | |

| λSa2 | S. agalactiae, S. pneumoniae, S. aureus |

N-terminal Endopeptidase C-terminal Glycosidase |

Middle Two copies of Cpl-7 CBD |

Pritchard et al., 2007 | |

| S. anginosus | SA01_53 | S. anginosus |

N-terminal Lysozyme |

C-terminal CW_7 |

van der Kamp et al., 2020 |

| S. dysgalactiae | PlySK1249 | S. dysgalactiae, S. agalactiae, S pyogenes |

N-terminal Amidase-3 C-terminal CHAP endopeptidase |

Middle LysM |

Oechslin et al., 2013 |

| S. infantis | 23TH_48 | S. infantis, S. pneumoniae |

N-terminal Amidase-5 |

C-terminal Choline-binding domain |

van der Kamp et al., 2020 |

| S. mitis | Skl | S. pneumoniae, S. mitis |

N-terminal CHAP amidase |

C-terminal Choline-binding domain |

Llull et al., 2006 |

| S. oralis | PH10 | S. oralis, S. pneumoniae, S. mitis |

N-terminal Lysozyme |

C-terminal Choline-binding domain |

van der Ploeg, 2010 |

| S. pneumoniae | Cpl-1 Cpl-7 Pal Hbl Ejl |

S. pneumoniae

S. pneumoniae |

N-terminal Lysozyme N-terminal Amidase |

C-terminal Choline-binding repeats (Cpl-1) CW_7 repeats (Cpl-7) C-terminal 6 Choline-binding repeats |

Bustamante et al., 2010; Diez-Martinez et al., 2013; Garcia et al., 1998; Romero et al., 1990; Diaz et al., 1992; Sheehan et al., 1997 |

| S. pyogenes | PlyC | Streptococcus groups A, C, E |

N-terminal PlyCA subunit CHAP amidase Lysozyme |

C-terminal PlyCB subunits An octamer of cell wall binding site |

McGowan et al., 2012; Nelson et al., 2001; Nelson et al., 2006 |

| PlyPy | Group A, B, and C streptococcus, S. uberis |

N-terminal CHAP endopeptidase |

C-terminal SH3b |

Lood et al., 2014 | |

| S. suis | LySMP | S. suis serotype 2, 7 and 9, Streptococcus equi ssp. zooepidemicus, Staphylococcus aureus |

N-terminal Endopeptidase and glycosidase (sequence homology with λSA2 and 263V/R) |

C-terminal Cpl-7 cell wall-binding domain |

Wang et al., 2009 |

| Ly 7917 | S. suis, S. equi ssp. zooepidemicus, S. aureus |

N-terminal CHAP |

C-terminal SH3b |

Ji et al., 2015 | |

| PlyARI | 30 S. suis strains, Staphylococcus aureus, and S. equi, medium affinity to S. pneumoniae and S. agalactiae |

N-terminal CHAP |

C-terminal SH3b |

Xiao et al., 2021 | |

| PlySs2 |

MRSA, VISA, S. suis, Listeria, Staphylococcus simulans, Staphylococcus epidermidis, S. equi, S. agalactiae, S. pyogenes, S. sanguinis, GGS, GES, and S. pneumoniae |

N-terminal CHAP |

C-terminal SH3_5 |

Gilmer et al., 2013; Vander Elst et al., 2020 | |

| PlySs9 | S. suis, S. uberis |

N-terminal Amidase C-terminal Endopeptidase |

Middle LysM |

Vander Elst et al., 2020 | |

| Ply30 | S. suis, S. equi subsp. Zooepidemicus |

N-terminal CHAP |

Middle SH3_5 |

Tang et al., 2015 | |

| Ply5218 | Multiple strains of S. suis | Unknown | Unknown | Zhang H. et al., 2016 |

CHAP, cysteine, histidine-dependent amidohydrolases/peptidases; GAS, group A Streptococcus; GBS, group B Streptococcus; GCS, group C Streptococcus; GES, Group E Streptococcus; GGS, group G Streptococcus; GLS, group L Streptococcus; MRSA, methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus; VISA, vancomycin intermediate Staphylococcus aureus.

The domain organization of PlyC, which is made up of a multimeric holoenzyme consisting of two major subunits, PlyCA and PlyCB, makes it one of the most unique endolysins among other streptococcal endolysins (McGowan et al., 2012). It exhibits potent lytic activity against S. pyogenes (GAS) and can also kill other streptococcal species, including GCS, and group E Streptococcus (GES) (Nelson et al., 2001). The N-terminal subunit PlyCA is connected to the C-terminal subunit PlyCB that is made of an octamer arranged in a ring-like structure. PlyCA was found to carry two EADs, CHAP and lysozyme domains, which contribute to the potency of the endolysin. For the CBD, the octamer in the PlyCB subunit is predicted to have eight distinct binding sites, which may broaden the host range and/or share a similar binding site that could enhance cell wall binding (McGowan et al., 2012). The full capacity of lysis is only achieved with the complete holoenzyme structure containing PlyCA and PlyCB (Nelson et al., 2006). On another note, PlyPy is an endolysin targeting S. pyogenes with only one EAD (CHAP) and one CBD (SH3). It also displays a wide host range, including S. pyogenes, GBS, GCS, and S. uberis, where the killing activity was high, but it showed low or no killing activity on other species such as S. suis, S. mutans, S. sobrinus, S. sanguinis, and S. pneumoniae (Lood et al., 2014).

Most endolysins targeting S. pneumoniae possess only one EAD. Endolysins Cpl-1 and Cpl-7 were proposed to have lysozyme activity, while Pal, Hbl, and Ejl have amidase activity (Romero et al., 1990; Diaz et al., 1992; Sheehan et al., 1997; Garcia et al., 1998; Bustamante et al., 2010). Unlike the broad host range of S. pyogenes endolysins, S. pneumoniae endolysins can only lyse one species. This is because the CBD of these enzymes, except Cpl-7, shares a remarkable similarity with the choline-binding repeats of LytA, an autolysin of S. pneumoniae involved in cell division (Romero et al., 1990; Diaz et al., 1992; Sheehan et al., 1997; Garcia et al., 1998; Bustamante et al., 2010). The choline-binding motif is key to S. pneumoniae recognition, which possess choline-containing teichoic acids in the cell wall. Interestingly, the CBD of Cpl-7 consists of three tandem repeats of 42 amino acids, termed CW_7, that are unrelated to the choline-binding motif of other pneumococcal endolysins (Bustamante et al., 2010). This motif was also found in endolysins of S. suis, S. anginosus, and S. agalactiae phages (Pritchard et al., 2007; Wang et al., 2009). Later, a new Cpl-7 derivative named Cpl-7S was developed by substituting 15 amino acids that shifted the charge at neutral pH from negative to positive. It enhanced the activity against S. pneumoniae and extended its host range to other species like S. pyogenes, E. faecalis, and S. mitis (Diez-Martinez et al., 2013).

The endolysins of S. suis were shown to have more varieties in terms of its EAD and CBD than other streptococcal species. For example, PlySs2 contains only one EAD (CHAP) and one CBD (SH3_5), whereas PlySs9 contains two EADs, one amidase at the N terminus and one endopeptidase at the C terminus with a LysM CBD in the middle (Vander Elst et al., 2020). PlySs2 showed a wider host range than PlySs9, which included MRSA, VISA, S. suis, Listeria, Staphylococcus simulans, Staphylococcus epidermidis, S. equi, S. agalactiae, S. pyogenes, S. sanguinis, GGS, GES, and S. pneumoniae. By contrast, PlySs9 can only lyse S. suis and S. uberis (Gilmer et al., 2013; Vander Elst et al., 2020). Also, a S. suis endolysin called LySMP can lyse S. suis serotypes 2, 7, and 9; Streptococcus equi ssp. Zooepidemicus; and S. aureus (Wang et al., 2009). It also has two N-terminal EADs: endopeptidase and glycosidase as shown by sequence homology with λSA2 and 263V/R S. agalactiae prophage. The CBD of this enzyme shares a high similarity with the Cpl-7-like CBD of S. pneumoniae endolysin (Wang et al., 2009). Other S. suis endolysins Ply30, Ly7917, and PlyARI have one CHAP EAD and SH3 CBD. They were shown to kill multiple strains of S. suis and S. equi ssp. zooepidemicus, while PlyARI had medium affinity toward S. pneumoniae and S. agalactiae (Ji et al., 2015; Tang et al., 2015; Xiao et al., 2021).

S. agalactiae endolysins such as PlyGBS, B30, λSa1, and λSa2 were also shown to have different types of EAD and CBD. PlyGBS and B30 endolysins have similar CHAP domains at the N terminus and glycosidase domain at the middle of the enzyme as their EAD, but the C-terminal CBD of PlyGBS is unknown, while B30 has an SH3b CBD (Cheng et al., 2005; Donovan et al., 2006b). The host range exhibited by these endolysins were also different, whereby PlyGBS could kill multiple strains of GBS, whereas B30 has wider lytic activity including activity against groups A, B, C, E, and G Streptococcus (Pritchard et al., 2004; Cheng et al., 2005). In addition, λSa1 and λSa2 endolysins, which originated from the same host 263V/R S. agalactiae, were shown to share a similar endopeptidase domain at the N terminus, but λSa2 has an additional amidase domain at its C terminus (Pritchard et al., 2007). The CBDs of these enzymes were also different where λSa1 contains an SH3b domain at the C terminus, while λSa2 consists of two copies of Cpl-7 CBD at the middle of the protein (Pritchard et al., 2007). Nonetheless, both enzymes showed similar lytic activity on S. agalactiae, S. pneumoniae, and S. aureus.

In addition to the native endolysin, engineering the EAD or CBD by altering the amino acid sequence or combining the domains from different endolysins to create “chimeolysin” (Table 2) could improve the potency and/or the host range of the endolysin. For example, Cpl-7S is a derivative of Cpl-7 endolysin that contains 15 amino acid substitutions in the CW_7 repeats. This engineered endolysin was shown to kill multidrug-resistant strains of S. pneumoniae, S. pyogenes, E. faecalis, and S. mitis. (Diez-Martinez et al., 2013). The chimeolysin Cpl-711 is a modified version of Cpl-7, which contains the EAD (lysozyme) from Cpl-7, a linker from Cpl-1, and the choline-binding CBD from Cpl-1. It was shown to be more potent than their parental enzyme, having stronger bactericidal activity against multidrug-resistant S. pneumoniae and retaining a wide host range, reduced biofilm production, and increased protection against infections in mice by 50% (Diez-Martinez et al., 2015).

TABLE 2.

List of engineered streptococcal endolysin (chimeolysin), including their origin, host range, enzymatically active domains (EADs), and cell wall-binding domains (CBDs).

| Chimeolysin/Artilysin | Lysin origin | Host range | Enzymatically active domain | Cell-wall binding domain | References |

| B30 fused with lysostaphin | B30 endolysin and Staphylococcus simulans lysostaphin | S. agalactiae, S. aureus, S. uberis, S. dysgalactiae | (i) CHAP endopeptidase, lysozyme (from B30), and glycylglycine endopeptidase (from lysostaphin) (ii) CHAP endopeptidase (from B30) and glycylglycine endopeptidase (from lysostaphin) |

(i) SH3b from B30 and SH3b from lysostaphin (ii) SH3b from lysostaphin only |

Donovan et al., 2006a |

| ClyJ, ClyJ-3, ClyJ-3m | PlyC endolysin and gp20 putative lysin | S. pneumoniae | CHAP domain of PlyC and amidase-2 from gp20 | Choline-binding domain from gp20 | Luo et al., 2020; Yang et al., 2019 |

| ClyR | PlyC endolysin and PlySs2 endolysin | S. pyogenes, S. agalactiae, S. dysgalactiae, S. equi, S. mutans, S. pneumoniae, S. suis and S. uberis, MRSA, VISA | CHAP domain of PlyC | SH3b domain from PlySs2 (PlySb) | Yang et al., 2015 |

| Cpl-7S | Cpl-7 endolysin | S. pneumoniae, S. pyogenes, E. faecalis, and S. mitis | Lysozyme | 15 amino acid substitution in CW_7 repeats | Diez-Martinez et al., 2013 |

| Cpl-711 | Cpl-1 endolysin and Cpl-7S endolysin | S. pneumoniae | Lysozyme from Cpl-7S | Linker and choline-binding domain from Cpl-1 | Diez-Martinez et al., 2015 |

| Csl2 | Cpl-7 endolysin and LySMP endolysin | S. suis, S. mitis, S. oralis, S. pseudopneumoniae | Lysozyme from Cpl-7 | Cpl-7-like CBD (CW_7 repeats) from LySMP | Vazquez et al., 2017 |

| PL3 | Pal endolysin and LytA autolysin | S. pneumoniae (including multi-resistant strains), S. pseudopneumoniae, S. mitis, S. oralis | Amidase from Pal | Choline-binding domain from LytA | Blazquez et al., 2016 |

CHAP, cysteine, histidine-dependent amidohydrolases/peptidases; MRSA, methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus; VISA, vancomycin intermediate Staphylococcus aureus.

Furthermore, ClyR is another chimeolysin that contains the CHAP EAD from PlyC and the CBD from PlySs2 which consists of the SH3b domain (Yang et al., 2015). It was selected due to its robust activity and extended host range through a screening method using E. coli, which involved the shuffling of EAD and CBD from various endolysin donors to produce a library of random chimeras. The random combination of endolysins was co-transformed into E. coli that expresses ClyN, another endolysin that was able to lyse E. coli from within, thus allowing the tested chimeolysin to enter the extracellular environment. The resulting chimeolysins were screened by spotting the clones onto a layer of target bacterial species, where the formation of plaque indicated an active chimeolysin. This screening method voided the need of purifying the chimeolysins before screening. In addition to that, ClyJ is another chimeolysin that contains the CHAP domain from PlyC. The CBD of this enzyme was taken from a putative endolysin, gp20 of the streptococcal phage SPSL1, which contained a choline-binding domain similar to LytA (Yang et al., 2019). ClyJ exhibited stronger activity against S. pneumoniae than Cpl-1, and it produced no resistance in bacteria after prolonged exposure to the enzyme (Yang et al., 2019). ClyJ also has several derivatives denoted as ClyJ-3 and ClyJ-3m, which are essentially truncated versions of ClyJ (Luo et al., 2020). ClyJ-3 has a shorter linker than the parental ClyJ, whereas ClyJ-3m is a variant of ClyJ-3, which has a truncated C-terminal tail. Similar to ClyJ, ClyJ-3 forms a dimer conformation upon binding with a choline molecule, while ClyJ-3m forms a monomer upon choline binding. The bactericidal activity was greatly enhanced in ClyJ-3m when compared to the parental enzymes ClyJ-3 and ClyJ (Luo et al., 2020).

In another report, PL3 is a chimeolysin which was derived from pneumococcal endolysin Pal and pneumococcal autolysin LytA (Blazquez et al., 2016). The EAD was taken from the N-acetylmuramoyl-L-alanine amidase from Pal, whereas the CBD consisted of the choline-binding domain from LytA. PL3 not only showed stronger lytic activity against choline-containing species than the parental enzyme but also showed remarkable stability. This enzyme showed activity at low doses (0.5–5 μg/ml), and it was able to retain its enzymatic activity after 4 weeks of incubation at 37°C (Blazquez et al., 2016). In yet another report, Csl2 chimeolysin was a combination of the glycoside hydrolase EAD from the Cpl-7 endolysin and the Cpl-7-like CBD (CW_7) from LySMP (Vazquez et al., 2017). It showed efficient killing of S. suis and S. mitis groups and also reducing biofilm formation in S. suis. In addition to that, the lytic activity was also proven in an infected zebrafish model, where the bacterial load in the blood was significantly lower when treated with a high dosage of Csl2 (Vazquez et al., 2017).

B30 S. agalactiae endolysin has also been modified to include lysostaphin from S. simulans to produce a chimeolysin, and two chimeolysins were produced—one which consisted of the full-length B30 in combination with S. simulans lysostaphin and the other consisted of a C-terminally truncated B30 in combination with S. simulans (Donovan et al., 2006a). The first construct had CHAP and lysozyme domains from B30 and glycylglycine endopeptidase from lysostaphin as the EAD, and two SH3b domains—one from B30 and the other from lysostaphin. The second construct only had CHAP from B30 and the endopeptidase and SH3b from lysostaphin. Both constructs showed activity against S. agalactiae, S. uberis, S. dysgalactiae, and S. aureus. Also, these chimeolysins which were cloned in an eukaryotic vector were shown to be successfully expressed in mammalian cells, therefore providing the possibility of creating transgenic mice and cattle which are resistant to mastitis (Donovan et al., 2006a).

Current applications of endolysins

Animal farming and the dairy industry

The prevalence of AMR bacterial strains and the outbreaks in animal farming are major global issues that have increased significantly in recent years. Endolysin has been studied as an alternative bactericidal and preservative agent in the bid to alleviate food security issues. While many endolysins have been identified and studied extensively for their efficacy against specific pathogenic bacteria in the food industry (Ajuebor et al., 2016; Chang, 2020; Xu, 2021), streptococcal endolysins are more applicable in the control of diseases in animal farming and its products, especially milk affected by mastitic cattle.

According to Schmelcher and Loessner (2016), streptococcal phage λSA2 and B30 endolysin had a synergistic lytic effect against S. agalactiae and S. uberis in milk and in a mouse mastitis model. It was also reported that λSA2 lysin had stronger activity than B30 lysin, with a reduction of 3.5-log CFU/mL at 100 μg/mL. Streptococcal phage Ply700 endolysin was also found to have a rapid, calcium-dependent lysis against S. uberis, S. pyogenes, and S. dysgalactiae while exhibiting a slight lysis activity toward S. agalactiae. Studies also showed that Ply700 lysin has substantial killing activity (reduction of 81% bacterial count) in milk at 50 μg/mL (Celia et al., 2008). On the other hand, ClyR was reported to show strong lytic activity against S. dysgalactiae and S. agalactiae in pasteurized milk with a reduction of 5-log CFU/mL at 25 μg/mL (Yang et al., 2015).

Another endolysin, PlyC lysin was shown to eliminate more than 20 clinical isolates of S. equi, the causative agent of equine strangles, a highly contagious disease affecting horses which can lead to mortality (Hoopes et al., 2009). It was reported that 1 μg of PlyC lysin can sterilize 8-log CFU/mL of S. equi within 30 min, which is 1,000 times more active than a common disinfectant, Virkon-S, used in the control of livestock diseases. Similarly, LySMP, which has an extensive lytic spectrum, is expected to be able to control S. suis infection in swine, which causes arthritis, endocarditis, meningitis, pneumonia, and septicemia. Importantly, S. suis is a zoonotic agent with human outbreaks reported in China in 1998, 1999, and 2005; thus, the control of this disease is pertinent (Wang et al., 2009).

Therapeutics

Phage therapy is an upcoming alternative therapeutic approach for a variety of animal and human infections by pathogenic bacteria. The lytic activity of various endolysins has also been tested and demonstrated by using in vivo mouse models. Cpl-1 lysin is a muramidase reported to rapidly lyse several other serotypes of S. pneumoniae. It has also been shown to eliminate S. pneumoniae nasopharyngeal colonization (Doehn et al., 2013). In addition, Cpl-1 dimers exhibited a 2-fold increase in antibacterial activity when compared to normal Cpl-1 (Resch et al., 2011). Ajuebor et al. (2016) also showed that Cpl-1 lysin could be aerosolized and administered through the respiratory airway to combat pneumococcal lung infections.

PlyC lysin, also referred to as the streptococcal C1 lysin, is a well-studied streptococcal endolysin with high specificity against group A, C, and E streptococci due to their two distinct EADs that have synergistic cleavage activities (Donovan and Foster-Frey, 2008; Shen et al., 2016; Vazquez et al., 2018; Linden et al., 2021). PlyC lysin was the first endolysin to exhibit in vivo efficacy following a nasopharyngeal challenge with S. pyogenes in mice. Other than that, PlyC lysin can also eliminate intracellular S. pyogenes by penetrating the epithelial cell lining of the respiratory tract (Vazquez et al., 2018; Linden et al., 2021).

Another endolysin, termed PlyPy lysin is derived from a prophage that infects S. pyogenes and was recently reported for its potential treatment of systemic bacteremia in mice. PlyPy lysin has a broad streptococci spectrum of activity with modest activity toward groups A, B, C, and E streptococci as well as S. uberis and S. gordonii (Xu, 2021). It is also the first S. pyogenes endolysin to be identified with a mechanism of action distinct from PlyC lysin (Donovan and Foster-Frey, 2008; Linden et al., 2021).

Biofilm elimination

Many pathogenic bacteria produce biofilm, resulting in resistance to many antimicrobial treatments, which is a major concern in food and clinical settings (Ajuebor et al., 2016; Ur Rahman et al., 2021). Shen et al. (2016) showed that PlyC lysin could rapidly degrade and kill S. pyogenes within the biofilm matrixes. Cpl-711 lysin, a chimeolysin with the fusion of Cpl-7 and Cpl-1, has improved antibiofilm and antimicrobial activities in vitro and in vivo over either of the parental enzymes (Linden et al., 2021). Studies have shown that treatment with Cpl-711 strongly reduced the attachment of S. pneumoniae to human epithelial cells, and a single intranasal dose of Cpl-711 significantly reduced nasopharyngeal colonization in a mouse model (Vazquez et al., 2018).

LySMP lysin, found in S. suis serotype 2 bacteriophage, was tested for lytic activity against S. suis biofilm formation. LySMP lysin has been shown to eliminate more than 80% of biofilm when compared to phages or antibiotics alone (Meng et al., 2011). In addition to that, studies have shown that treatment using 50 μg/mL of ClyR lysin can reduce the biofilm of S. mutans and S. sobrinus within 5 min. It also shows that continuous administration of ClyR lysin in rat models infected with S. mutans and S. sobrinus can lower the severity for over 40 days (Xu et al., 2018).

Advantages and limitations of endolysin therapy

Endolysins are highly specific and only lyse target bacteria depending on the presence of respective binding ligands with different cleavage mechanisms. This specificity has contributed to the narrow spectrum of endolysin lytic activity, which causes minimal disruption to other microbiota, thus giving it a huge advantage over broad range of antibiotics (Nayak et al., 2019; Schmelcher and Loessner, 2021). Studies have also shown that using more than one endolysin or combining endolysins with other antimicrobial agents enables a synergistic effect against bacterial infections. This can help reduce the required dose used for treatment and can also enhance the efficacy of the treatment (Nayak et al., 2019; Murray et al., 2021). For example, a study by Letrado et al. (2018) showed that the combination of lysin Cpl-711 with amoxicillin or cefotaxime resulted in a synergistic effect against MDR clinical isolates of S. pneumoniae.

The development of drug resistance in bacteria toward endolysin is also lower than that in antibiotics. Antibiotics work by interfering with the bacterial cell wall to prevent the growth and replication of bacteria, while endolysins work by lysing the bacterial cell wall. Furthermore, the binding and cleavage of endolysins target highly conserved regions of the cell wall, which are unlikely to mutate. Other than that, endolysins have not been reported to show any significant negative side effects or toxicity to mammalian cells (Romero-Calle et al., 2019). Endolysins also have a low environmental impact compared to antibiotics. For example, endolysins are composed mostly of proteins and can be rapidly inactivated or degraded by environmental factors, while non-metabolized antibiotics or residues that are released into the environment will have an impact on the environment that can indirectly accelerate the emergence of bacterial MDR (Loc-Carrillo and Abedon, 2011; Aslam et al., 2018; Alves-Barroco et al., 2020).

Although endolysins have many advantages, there are some challenges that limit the use of endolysin therapy. Endolysins show good efficacy in treating Gram-positive bacteria but are mostly ineffective against Gram-negative bacteria due to the outer membrane barrier. Fortunately, this problem can be potentially resolved with the addition of ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA), which helps permeabilize the cell membrane. EDTA is a chelating agent that disrupts the outer membrane and unveils the peptidoglycan cell wall for lysis (Abdelrahman et al., 2021; Murray et al., 2021). In addition, artilyzation of Gram-negative endolysins can also help overcome this limitation. Furthermore, the encapsulation of endolysins into delivery vehicles such as chitosan nanoparticles and mucoadhesive film approaches can also be studied to enhance their bioavailability (Tan et al., 2019; Gondil and Chhibber, 2021).

To date, the usage of phage therapy in most countries still faces regulatory issues due to the lack of established clinical trials and safety data. However, phage therapy remains active in places such as Poland and Georgia, which provide personalized phage treatments for patients with antibiotic-resistant infections. The regulatory framework of established phage therapy is still on-going as there are little phage-related products licensed and marketed to date. Therefore, further evidence of successful human trials in phage therapy that can help current regulatory agencies gain practicable insights into phage therapy is needed (Fauconnier, 2019; Pires et al., 2020).

In the clinical setting, another crucial limitation of endolysins is the possibility of immune reactions as endolysins are ultimately proteins. The inflammatory responses and toxicity of endolysins have been tested and evaluated in animal models, and some endolysins do indeed provoke an immune response when they are used systematically (Abdelrahman et al., 2021). However, antibodies are weak inactivators of endolysins and were found to be unable to diminish the lytic capability of endolysins in the studies reported (Loeffler et al., 2003; Zhang L. et al., 2016). Nevertheless, the half-life of endolysins could be shortened due to host immune response as observed for the Cpl-1 endolysin in mice, which could indicate that multiple dosage may be required for eradication of infections (Loeffler et al., 2003). In addition, endolysins have also been found to be largely non-toxic to hosts (Murray et al., 2021). It should however be noted that in a study involving repeated dosage of endolysin treatment in canine with daily injection of the endolysin SAL200 against Staphylococcus aureus for more than 1 week, there were some transient abnormal clinical signs observed, which included subdued behavior and vomiting (Jun et al., 2014). While the symptoms were mild and self-limiting (resolved in 1 h), more clinical trials are needed to further accentuate the safety profile of endolysins for treatment.

Despite multiple studies highlighting the potential of endolysins as an antibiotic alternative to combat AMR, its current cost remains a stumbling block at this point in time in addition to the limitations highlighted before. As with all protein-based therapeutics, cost is usually a constraint when it comes to practical industrial adoption owing to relatively high production, purification, storage, and supply chain expenses relative to conventional synthetic-based equivalents (Love et al., 2018; Garcia et al., 2019; Gontijo et al., 2021; Lee et al., 2022). Hence, economic analyses and in silico model simulations such as response surface methodology for large-scale production and process conditions including media optimization and bioreactor conditions can help reduce costs (Krysiak-Baltyn et al., 2018; Pournejati and Karbalaei-Heidari, 2020). Purification costs should also be taken into consideration, especially purification from endotoxins, since E. coli is the most commonly used host for recombinant endolysins. Alternatively, Gram-positive microbial cell factories such as lactic acid bacteria can be used to produce endolysins. They are generally recognized as safe (GRAS), do not produce endotoxins, and can double up as a delivery vehicle, which may rid the need for purification, especially when the endolysin is secreted out of the cell (Chandran et al., 2022; Lee et al., 2022). Continuous investments are required for various sectors to embrace and adopt new techniques more quickly, while endorsement of phage and endolysin-based products by policymakers is pivotal when pushing them as mainstream antimicrobials.

Conclusion

Phage therapy is currently a popular area of research with a high potential to become a treatment option for bacterial infections, including MDR bacteria. Their high recognition and binding specificity range can vary from the entire bacterial genus to a specific bacterial strain, making them a good candidate to replace antibiotic therapy. While some endolysins also can lyse across genus, these are not common. Further in vivo studies and clinical trials for various endolysins targeting different bacterial species are needed to ensure phage-derived lysins does not cause any form of toxicity, immunoreactions, and resistance to the target. Other than that, the development of chimeolysins and artilysins by using protein engineering and immune engineering has the potential to not only further improve lytic activity and target host range but also overcome undesired immunological responses when used systematically.

Author contributions

KW and MM wrote the main manuscript text. KW, MM, and MT prepared figures and tables. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Malaysia Research University Network under the MRUN Young Researchers Grant Scheme (MYRGS) project code MY-RGS 2019-1 and UCSI University Research Excellence and Innovation Grant (REIG) (REIG-FAS-2020/004).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

- Abdelkader K., Gerstmans H., Saafan A., Dishisha T., Briers Y. (2019). The preclinical and clinical progress of bacteriophages and their lytic enzymes: the parts are easier than the whole. Viruses 11:96. 10.3390/v11020096 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abdelrahman F., Easwaran M., Daramola O. I., Ragab S., Lynch S., Oduselu T. J., et al. (2021). Phage-encoded endolysins. Antibiotics 10:124. 10.3390/antibiotics10020124 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ajuebor J., Mcauliffe O., O’mahony J., Ross R. P., Hill C., Coffey A. (2016). Bacteriophage endolysins and their applications. Sci. Prog. 99 183–199. 10.3184/003685016X14627913637705 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alves-Barroco C., Rivas-García L., Fernandes A. R., Baptista P. V. (2020). Tackling Multidrug Resistance in Streptococci – From Novel Biotherapeutic Strategies to Nanomedicines. Front. Microbiol. 11:579916. 10.3389/fmicb.2020.579916 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aslam B., Wang W., Arshad M. I., Khurshid M., Muzammil S., Rasool M. H., et al. (2018). Antibiotic resistance: a rundown of a global crisis. Infect. Drug Resist. 11 1645–1658. 10.2147/IDR.S173867 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernheimer H. P. (1979). Lysogenic pneumococci and their bacteriophages. J. Bacteriol. 138 618–624. 10.1128/jb.138.2.618-624.1979 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blazquez B., Fresco-Taboada A., Iglesias-Bexiga M., Menendez M., Garcia P. (2016). PL3 amidase, a tailor-made lysin constructed by domain shuffling with potent killing activity against Pneumococci and related species. Front. Microbiol. 7:1156. 10.3389/fmicb.2016.01156 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bobadilla F. J., Novosak M. G., Cortese I. J., Delgado O. D., Laczeski M. E. (2021). Prevalence, serotypes and virulence genes of Streptococcus agalactiae isolated from pregnant women with 35 – 37 weeks of gestation. BMC Infect. Dis. 21:73. 10.1186/s12879-020-05603-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broendum S. S., Buckle A. M., Mcgowan S. (2018). Catalytic diversity and cell wall binding repeats in the phage-encoded endolysins. Mol. Microbiol. 110 879–896. 10.1111/mmi.14134 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bustamante N., Campillo N. E., Garcia E., Gallego C., Pera B., Diakun G. P., et al. (2010). Cpl-7, a lysozyme encoded by a pneumococcal bacteriophage with a novel cell wall-binding motif. J. Biol. Chem. 285 33184–33196. 10.1074/jbc.M110.154559 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bustamante N., Iglesias-Bexiga M., Bernardo-García N., Silva-Martín N., García G., Campanero-Rhodes M. A., et al. (2017). Deciphering how Cpl-7 cell wall-binding repeats recognize the bacterial peptidoglycan. Sci. Rep. 7:16494. 10.1038/s41598-017-16392-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bustamante N., Rico-Lastres P., García E., García P., Menéndez M. (2012). Thermal stability of Cpl-7 endolysin from the Streptococcus pneumoniae bacteriophage Cp-7; cell wall-targeting of its CW_7 motifs. PLoS One 7:e46654. 10.1371/journal.pone.0046654 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byun B., Mahasenan K. V., Dik D. A., Marous D. R., Speri E., Kumarasiri M., et al. (2018). Mechanism of the Escherichia coli MltE lytic transglycosylase, the cell-wall-penetrating enzyme for Type VI secretion system assembly. Sci. Rep. 8:4110. 10.1038/s41598-018-22527-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Celia L. K., Nelson D., Kerr D. E. (2008). Characterization of a bacteriophage lysin (Ply700) from Streptococcus uberis. Vet. Microbiol. 130 107–117. 10.1016/j.vetmic.2007.12.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chandran C., Tham H. Y., Abdul Rahim R., Lim S. H. E., Yusoff K., Song A. A. (2022). Lactococcus lactis secreting phage lysins as a potential antimicrobial against multi-drug resistant Staphylococcus aureus. PeerJ 10:e12648. 10.7717/peerj.12648 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang Y. (2020). Bacteriophage-derived endolysins applied as potent biocontrol agents to enhance food safety. Microorganisms 8:724. 10.3390/microorganisms8050724 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang Y., Ryu S. (2017). Characterization of a novel cell wall binding domain-containing Staphylococcus aureus endolysin LysSA97. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 101 147–158. 10.1007/s00253-016-7747-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng Q., Nelson D., Zhu S., Fischetti V. A. (2005). Removal of group b streptococci colonizing the vagina and oropharynx of mice with a bacteriophage lytic enzyme. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 49 111–117. 10.1128/AAC.49.1.111-117.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diaz E., Lopez R., Garcia J. L. (1992). EJ-1, a temperate bacteriophage of Streptococcus pneumoniae with a Myoviridae morphotype. J. Bacteriol. 174 5516–5525. 10.1128/jb.174.17.5516-5525.1992 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diez-Martinez R., De Paz H. D., Bustamante N., Garcia E., Menendez M., Garcia P. (2013). Improving the lethal effect of cpl-7, a pneumococcal phage lysozyme with broad bactericidal activity, by inverting the net charge of its cell wall-binding module. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 57 5355–5365. 10.1128/AAC.01372-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diez-Martinez R., De Paz H. D., Garcia-Fernandez E., Bustamante N., Euler C. W., Fischetti V. A., et al. (2015). A novel chimeric phage lysin with high in vitro and in vivo bactericidal activity against Streptococcus pneumoniae. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 70 1763–1773. 10.1093/jac/dkv038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dik D. A., Marous D. R., Fisher J. F., Mobashery S. (2017). Lytic Transglycosylases: concinnity in concision of the bacterial cell wall. Crit. Rev. Biochem. Mol. 52 503–542. 10.1080/10409238.2017.1337705 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doehn J. M., Fischer K., Reppe K., Gutbier B., Tschernig T., Hocke A. C., et al. (2013). Delivery of the endolysin Cpl-1 by inhalation rescues mice with fatal pneumococcal pneumonia. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 68 2111–2117. 10.1093/jac/dkt131 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Domelier A. S., Van Der Mee-Marquet N., Sizaret P. Y., Héry-Arnaud G., Lartigue M. F., Mereghetti L., et al. (2009). Molecular characterization and lytic activities of Streptococcus agalactiae bacteriophages and determination of lysogenic-strain features. J. Bacteriol. 191 4776–4785. 10.1128/JB.00426-09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donovan D. M., Foster-Frey J. (2008). LambdaSa2 prophage endolysin requires Cpl-7-binding domains and amidase-5 domain for antimicrobial lysis of streptococci. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 287 22–33. 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2008.01287.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donovan D. M., Foster-Frey J., Dong S., Rousseau G. M., Moineau S., Pritchard D. G. (2006b). The cell lysis activity of the streptococcus agalactiae bacteriophage b30 endolysin relies on the cysteine, histidine-dependent amidohydrolase/peptidase domain. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 72 5108–5112. 10.1128/AEM.03065-05 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donovan D. M., Dong S., Garrett W., Rousseau G. M., Moineau S., Pritchard D. G. (2006a). Peptidoglycan hydrolase fusions maintain their parental specificities. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 72 2988–2996. 10.1128/AEM.72.4.2988-2996.2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dörr T., Moynihan P. J., Mayer C. (2019). Editorial: bacterial cell wall structure and dynamics. Front. Microbiol. 10:2051. 10.3389/fmicb.2019.02051 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drulis-Kawa Z., Majkowska-Skrobek G., Maciejewska B. (2015). Bacteriophages and phage-derived proteins – application approaches. Curr. Med. Chem. 22 1757–1773. 10.2174/0929867322666150209152851 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duzgunes N., Sessevmez M., Yildirim M. (2021). Bacteriophage therapy of bacterial infections: the rediscovered frontier. Pharmaceuticals 14:34. 10.3390/ph14010034 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Efstratiou A., Lamagni T., Turner C. E. (2017). “Streptococci and Enterococci,” in Infectious diseases (4th ed), eds Cohen J., Powderly W. G., Opal S. M. (Amsterdam: Elsevier Ltd; ), 1523–1536. [Google Scholar]

- Fauconnier A. (2019). Phage therapy regulation: from night to dawn. Viruses 11:352. 10.3390/v11040352 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischetti V. A. (2018). Development of phage lysins as novel therapeutics: a historical perspective. Viruses 10:310. 10.3390/v10060310 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia E., Garcia J. L., Garcia P., Arraras A., Sanchez-Puelles J. M., Lopez R. (1988). Molecular evolution of lytic enzymes of Streptoccus pneumoniae and its bacteriophages. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 85 914–918. 10.1073/pnas.85.3.914 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia E., Garcia J. L., Garcia P., Arraras A., Sanchez-Puelles J. M., Lopez R. (1998). Molecular evolution of lytic enzymes of Streptococcus pneumoniae and its bacteriophages. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 85 914–918. 10.1073/pnas.85.3.914 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia J. L., Garcia E., Arraras A., Garcia P., Ronda C., Lopez R. (1987). Cloning, purification, and biochemical characterization of the pneumococcal bacteriophage Cp-1 lysin. J. Virol. 61 2573–2580. 10.1128/JVI.61.8.2573-2580.1987 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia P. (1983). A phage-associated murein hydrolase in Streptococcus pneumoniae infected with bacteriophage Dp-1. J. Gen. Microbiol. 129 489–497. 10.1099/00221287-129-2-489 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia P., Martin A. C., Lopez R. (1997). Bacteriophages of Streptococcus pneumoniae: a molecular approach. Microb. Drug Resist. 3 165–176. 10.1089/mdr.1997.3.165 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia R., Latz S., Romero J., Higuera G., Garcia K., Bastias R. (2019). Bacteriophage production models: an overview. Front. Microbiol. 10:1187. 10.3389/fmicb.2019.01187 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilmer D. B., Schmitz J. E., Euler C. W., Fischetti V. A. (2013). Novel bacteriophage lysin with broad lytic activity protects against mixed infection by Streptococcus pyogenes and methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 57 2743–2750. 10.1128/AAC.02526-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gondil V. S., Chhibber S. (2021). Bacteriophage and endolysins encapsulation systems: a promising strategy to improve therapeutic outcomes. Front. Pharmacol. 12:675440. 10.3389/fphar.2021.675440 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gontijo M. T. P., Jorge G. P., Brocchi M. (2021). Current status of endolysin-based treatments against Gram-negative bacteria. Antibiotics 10:1143. 10.3390/antibiotics10101143 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo Y., Song G., Sun M., Wang J., Wang Y. (2020). Prevalence and therapies of antibiotic-resistance in staphylococcus aureus. Front. Cell Infect. Microbiol. 10:107. 10.3389/fcimb.2020.00107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haenni M., Lupo A., Madec J. (2018). Antimicrobial resistance in Streptococcus spp. Microbiol. Spectr. 6 1–25. 10.1128/microbiolspec.ARBA-0008-2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hauser R., Blasche S., Dokland T., Haggard-Ljungquist E., von Brunn A., Salas M., et al. (2012). Bacteriophage protein-protein interactions. Adv. Virus Res. 83 219–298. 10.1016/B978-0-12-3944438-2.00006-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hermoso J. A., Monterroso B., Albert A., Galán B., Ahrazem O., García P., et al. (2003). Structural basis for selective recognition of pneumococcal cell wall by modular endolysin from phage Cp-1. Structure 11 1239–1249. 10.1016/j.str.2003.09.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoopes J. T., Stark C. J., Kim H. A., Sussman D. J., Donovan D. M., Nelson D. C. (2009). Use of a bacteriophage lysin, PlyC, as an enzyme disinfectant against Streptococcus equi. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 75 1388–1394. 10.1128/AEM.02195-08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jado I., Lopez R., Garcia E., Fenoll A., Casal J., Garcia P. (2003). Spanish Pneumococcal Infection Study Network. Phage lytic enzymes as therapy for antibiotic-resistant Streptococcus pneumoniae infection in a murine sepsis model. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 52 967–973. 10.1093/jac/dkg485 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenkins C. H., Wallis R., Allcock N., Barnes K. B., Richards M. I., Auty J. M., et al. (2019). The lytic transglycosylase, LtgG, controls cell morphology and virulence in Burkholderia pseudomallei. Sci. Rep. 9:11060. 10.1038/s41598-019-47483-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ji W., Huang Q., Sun L., Wang H., Yan Y., Sun J. (2015). A novel endolysin disrupts Streptococcus suis with high efficiency. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 362:fnv205. 10.1093/femsle/fnv205 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang H., Huai Y., Chen H., Uyeki T. M., Chen M., Guan X., et al. (2018). Invasive Streptococcus pneumoniae infection among hospitalized patients in Jingzhou city, China, 2010-2012. PLoS One 13:e0201312. 10.1371/journal.pone.0201312 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jun S. Y., Jung G. M., Yoon S. J., Choi Y. J., Koh W. S., Moon K. S., et al. (2014). Preclinical safety evaluation of intravenously administered SAL200 containing the recombinant phage endolysin SAL-1 as a pharmaceutical ingredient. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 58 2084–2088. 10.1128/AAC.02232-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krysiak-Baltyn K., Martin G. J. O., Gras S. L. (2018). Computational modelling of large scale phage production using a two-stage batch process. Pharmaceuticals 11:31. 10.3390/ph11020031 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee C., Kim H., Ryu S. (2022). Bacteriophage and endolysin engineering for biocontrol of food pathogens/pathogens in the food: recent advances and future trends. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. [Epub ahead of print]. 10.1080/10408398.2022.2059442 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Letrado P., Corsini B., Díez-Martínez R., Bustamante N., Yuste J. E., García P. (2018). Bactericidal synergism between antibiotics and phage endolysin Cpl-711 to kill multidrug-resistant pneumococcus. Future Microbiol. 13 1215–1223. 10.2217/fmb-2018-0077 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin D. M., Koskella B., Lin H. C. (2017). Phage therapy: an alternative to antibiotics in the age of multi-drug resistance. World J. Gastrointest. Pharmacol. Ther. 8 162–173. 10.4292/wjgpt.v8.i3.162 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linden S. B., Alreja A. B., Nelson D. C. (2021). Application of bacteriophage-derived endolysins to combat streptococcal disease: current State and perspectives. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 68 213–220. 10.1016/j.copbio.202101.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Llull D., Lopez R., Garcia E. (2006). Skl, a novel choline-binding N-acetylmuramoyl-L-alanine amidase of Streptococcus mitis SK137 containing a CHAP domain. FEBS Lett. 580 1959–1964. 10.1016/j.febslet.2006.02.060 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loc-Carrillo C., Abedon S. T. (2011). Pros and cons of phage therapy. Bacteriophage 1 111–114. 10.4161/bact.1.2.14590 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loeffler J. M., Djurkovic S., Fischetti V. A. (2003). Phage lytic enzyme Cpl-1 as a novel antimicrobial for Pneumococcal Bacteremia. Infect. Immun. 71 6199–6204. 10.1128/IAI.71.11.6199-6204.2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lood R., Raz A., Molina H., Euler C. W., Fischetti V. A. (2014). A highly active and negatively charged Streptococcus pyogenes lysin with a rare D-alanyl-L-alanine endopeptidase activity protects mice against streptococcal bacteremia. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 58 3073–3084. 10.1128/AAC.00115-14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Love M. J., Bhandari D., Dobson R. C. J., Billington C. (2018). Potential for bacteriophage endolysins to supplement or replace antibiotics in food production and clinical care. Antibiotics 7:17. 10.3390/antibiotics7010017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo D., Huang L., Gondil V. S., Zhou W., Yang W., Jia M., et al. (2020). A choline-Recognizing Monomeric Lysin, ClyJ-3m, Shows Elevated Activity against Streptococcus pneumoniae. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 64:e311–e320. 10.1128/AAC.00311-20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonnell M., Ronda-Lain C., Tomasz A. (1975). “Diplophage”: a bacteriophage of Diplococcus pneumoniae. Virology 63 577–582. 10.1016/0042-6822(75)90329-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGowan S., Buckle A. M., Mitchell M. S., Hoopes J. T., Gallagher D. T., Heselpoth R. D., et al. (2012). X-ray crystal structure of the streptococcal specific phage lysin PlyC. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 109 12752–12757. 10.1073/pnas.1208424109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meng X., Shi Y., Ji W., Meng X., Zhang J., Wang H., et al. (2011). Application of a bacteriophage lysin to disrupt biofilms formed by the animal pathogen Streptococcus suis. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 77 8272–8279. 10.1128/AEM.05151-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitkowski P., Jagielska E., Nowak E., Bujnicki J. M., Stefaniak F., Niedziałek D., et al. (2019). Structural bases of peptidoglycan recognition by lysostaphin SH3b domain. Sci. Rep. 9:5965. 10.1038/s41598-019-42435-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muraosa Y., Toyotome T., Yahiro M., Kamei K. (2019). Characterisation of novel-cell-wall LysM-domain proteins LdpA and LdpB from the human pathogenic fungus Aspergillus fumigatus. Sci. Rep. 9:3345. 10.1038/s41598-019-40039-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray E., Draper L. A., Ross R. P., Hill C. (2021). The advantages and challenges of using endolysins in a clinical setting. Viruses 13:680. 10.3390/v13040680 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nayak T., Singh R. K., Jaiswal L. K., Gupta A. (2019). Bacteriophage encoded endolysins as potential antibacterials. J. Sci. Res. 63 39–48. [Google Scholar]

- Nelson D., Loomis L., Fischetti V. A. (2001). Prevention and elimination of upper respiratory colonization of mice by group A streptococci by using a bacteriophage lytic enzyme. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 98 4107–4112. 10.1073/pnas.061038398 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson D., Schuch R., Chahales P., Zhu S., Fischetti V. A. (2006). PlyC: a multimeric bacteriophage lysin. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 103 10765–10777. 10.1073/pnas.0604521103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson D., Schuch R., Zhu S., Tscheme D. M., Fischetti V. A. (2003). Genomic sequence of C1, the first streptococcal phage. J. Bacteriol. 185 3325–3332. 10.1128/JB.185.11.3325-3332.2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oechslin F., Daraspe J., Giddey M., Moreillon P., Resch G. (2013). In vitro characterization of PlySK1249, a novel phage lysin, and assessment of its antibacterial activity in a mouse model of Streptococcus agalactiae bacteremia. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 57 6276–6283. 10.1128/AAC.01701-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osman K. M., Al-Maary K. S., Mubarak A. S., Dawoud T. M., Moussa I. M. I., Ibrahim M. D. S., et al. (2017). Characterization and susceptibility of streptococci and enterococci isolated from Nile tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus) showing septicaemia in aquaculture and wild sites in Egypt. BMC Vet. Res. 13:357. 10.1186/s12917-017-1289-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pires D. P., Costa A. R., Pinto G., Meneses L., Azeredo J. (2020). Current challenges and future opportunities of phage therapy. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 44 684–700. 10.1093/femsre/fuaa017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pournejati R., Karbalaei-Heidari H. R. (2020). Optimization of fermentation conditions to enhance cytotoxic metabolites production by bacillus velezensis strain RP137 from the persian gulf. Avicenna J. Med. Biotechnol. 12 116–123. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pradeep P. J., Suebsing R., Sirthammajak S., Kampeera J., Jitrakorn S., Saksmerprome V., et al. (2016). Evidence of vertical transmission and tissue tropism of Streptococcosis from naturally infected red tilapia (Oreochromis spp.). Aquac. Res. 3 58–66. 10.1016/j.aqrep/2015/12/002 26937337 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Prestinaci F., Pezzotti P., Pantosti A. (2015). Antimicrobial resistance: a global multifaceted phenomenon. Pathog. Glob. Health 109 309–318. 10.1179/2047773215Y.0000000030 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pritchard D. G., Dong S., Baker J. R., Engler J. A. (2004). The bifunctional peptidoglycan lysin of Streptococcus agalactiae bacteriophage B30. Microbiology 150 2079–2087. 10.1099/mic.0.27063-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pritchard D. G., Dong S., Kirk M. C., Cartee R. T., Baker J. R. (2007). LamdbaSa1 and LambdaSa2 prophage lysins of Streptococcus agalactiae. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 73 7150–7154. 10.1128/AEM.01783-07 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Renzhammer R., Loncaric I., Ladstätter M., Pinior B., Roch F. F., Spergser J., et al. (2020). Detection of various Streptococcus spp. and their antimicrobial resistance patterns in clinical specimens from austrian swine stocks. Antibiotics 9:893. 10.3390/antibiotics9120893 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Resch G., Moreillon P., Fischetti V. A. (2011). A stable phage lysin (Cpl-1) dimer with increased antipneumococcal activity and decreased plasma clearance. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 38 516–521. 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2011.08.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roach D. R., Donovan D. M. (2015). Antimicrobial bacteriophage-derived proteins and therapeutic applications. Bacteriophage 5:e1062590. 10.1080/21597081/2015.1062590 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romero A., Lopez R., Garcia P. (1990). Characterization of the pneumococcal bacteriophage HB-3 amidase: cloning and expression in Escherichia coli. J. Virol. 64 137–142. 10.1128/JVI.64.1.137-142.1990 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romero-Calle D., Benevides R. G., Góes-Neto A., Billington C. (2019). Bacteriophages as alternatives to antibiotics in clinical care. Antibiotics 8:138. 10.3390/antibiotics8030138 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ronda C., Lopez R., Garcia E. (1981). Isolation and characterization of a new bacteriophage, Cp-1, infecting Streptococcus pneumoniae. J. Virol. 40 551–559. 10.1128/jvi/40.2.551-559.1981 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmelcher M., Loessner M. J. (2016). Bacteriophage endolysins: applications for food safety. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 37 76–87. 10.1016/j.copbio.2015.10.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmelcher M., Loessner M. J. (2021). Bacteriophage endolysins — extending their application to tissues and the bloodstream. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 68 51–59. 10.1016/j.copbio.2020.09.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmelcher M., Donovan D. M., Loessner M. J. (2012). Bacteriophage endolysins as novel antimicrobials. Future Microbiol. 7 1147–1171. 10.2217/fmb.12.97 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheehan M. M., Garcia J. L., Lopez R., Garcia P. (1997). The lytic enzyme of the pneumococcal phage DP-1: a chimeric lysin of intergeneric origin. Mol. Microbiol. 25 717–725. 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.5101880.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen Y., Barros M., Vennemann T., Gallagher D. T., Yin Y., Linden S. B., et al. (2016). A bacteriophage endolysin that eliminates intracellular streptococci. Elife 5:e13152. 10.7554/eLife.13152 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slater J. (2007). “Bacterial infections of the equine respiratory tract,” in Equine Respiratory Medicine and Surgery, eds McGorum B. C., Dixon P. M., Robinson E. N., Schumacher J. (Amsterdam: Elsevier Ltd; ), 327–353. [Google Scholar]

- Tan E. W., Tan K. Y., Phang L. V., Kumar P. V., In L. L. (2019). Enhanced gastrointestinal survivability of recombinant Lactococcus lactis using a double coated mucoadhesive film approach. PLoS One 14:e0219912. 10.1371/journal.pone.0219912 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang F., Li D., Wang H., Ma Z., Lu C., Dai J. (2015). Prophage Lysin Ply30 Protects Mice from Streptococcus suis and Streptococcus equi subsp. zooepidemicus Infections. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 81 7377–7384. 10.1128/AEM.02300-15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Totté J. E. E., van Doorn M. B., Pasmans S. G. M. A. (2017). Successful Treatment of Chronic Staphylococcus aureus-Related Dermatoses with the Topical Endolysin Staphefekt SA.100: a Report of 3 Cases. Case Rep. Dermatol. 9 19–25. 10.1159/000473872 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ur Rahman M., Wang W., Sun Q., Shah J. A., Li C., Sun Y., et al. (2021). Endolysin, a promising solution against antimicrobial resistance. Antibiotics 10:1277. 10.3390/antibiotics10111277 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Kamp I., Draper L. A., Smith M. K., Buttimer C., Ross R. P., Hill C. (2020). A new phage lysin isolated from the oral microbiome targeting Streptococcus pneumoniae. Pharmaceuticals 13:478. 10.3390/ph13120478 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Ploeg J. R. (2010). Genome sequence of the temperate bacteriophage PH10 from Streptocccus oralis. Virus Genes 41 450–458. 10.1007/s11262-010-0525-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Hensbergen V. P., Movert E., de Maat V., Lüchtenborg C., Breton Y. L., Lambeau G., et al. (2018). Streptococcal Lancefield polysaccharides are critical cell wall determinants for human Group IIA secreted phospholipase A2 to exert its bactericidal effects. PLoS Pathog. 14:e1007348. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1007348 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vander Elst N., Linden S. B., Lavigne R., Meyer E., Briers Y., Nelson D. C. (2020). Characterization of the bacteriophage-derived endolysins PlySs2 and PlySs9 with in vitro lytic activity against Bovine Mastitis Streptococcus uberis. Antibiotics 9:621. 10.3390/antibiotics9090621 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vazquez R., Domenech M., Iglesias-Bexiga M., Menendez M., Garcia P. (2017). Csl2, a novel chimeric bacteriophage lysin to fight infections caused by Streptococcus suis, an emerging zoonotic pathogen. Sci. Rep. 7:16506. 10.1038/s41598-017-16736-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vazquez R., García E., García P. (2018). Phage lysins for fighting bacterial respiratory infections: a new generation of antimicrobials. Front. Immunol. 9:2252. 10.3389/fimmu.2018.02252 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vermassen A., Leroy S., Talon R., Provot C., Popowska M., Desvaux M. (2019). Cell wall hydrolases in bacteria: insight on the diversity of cell wall amidases, glycosidases and peptidases toward peptidoglycan. Front. Microbiol. 10:331. 10.3389/fmicb.2019.00331 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walmagh M., Briers Y., dos Santos S. B., Azeredo J., Lavigne R. (2012). Characterization of modular bacteriophage endolysins from Myoviridae Phages OBP, 201φ2-1 and PVP-SE1. PLoS One 7:e36991. 10.1371/journal.pone/0036991 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y., Sun J. H., Lu C. P. (2009). Purified recombinant phage lysin LySMP: an extensive spectrum of lytic activity for swine streptococci. Curr. Microbiol. 58 609–615. 10.1007/s00284-009-9379-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiser J. N., Ferreira D. M., Paton J. C. (2018). Streptococcus pneumoniae: transmission, colonization and invasion. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 16:355. 10.1038/s41579-018-0001-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao Y., Chen R., Li M., Qi Z., Yu Y., Pan Z., et al. (2021). The effectiveness of extended binding affinity of prophage lysin PlyARI against Streptococcus suis infection. Arch. Microbiol. 203 5163–5172. 10.1007/s00203-021-02438-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu J., Yang H., Bi Y., Li W., Wei H., Li Y. (2018). Activity of the chimeric lysin ClyR against common gram-positive oral microbes and its anticaries efficacy in rat models. Viruses 10:380. 10.3390/v10070380 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu Y. (2021). Phage and phage lysins: new era of bio-preservatives and food safety agents. J. Food Sci. 86 3349–3373. 10.1111/1750-3841.15843 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]