Abstract

Objective: The aim of this single-centre, cross-sectional study was to evaluate dental, periodontal and mycological findings, as well as oral behaviour, in patients before (pre-LTx) and after (post-LTx) liver transplantation. Methods: A total of 47 patients pre-LTx and 119 patients post-LTx were asked to participate. Oral health behaviour was assessed using a standardised questionnaire. Oral examinations included dental [decayed, missing and filled teeth (DMFT) index] and periodontal [papillary bleeding index (PBI), periodontal probing depth (PPD) and clinical attachment loss (CAL)] findings. For Candida screening, swabs from the oral mucosa were cultured. Statistical analysis was performed using the Student's t-test or the Mann–Whitney U-test, depending on whether or not the data followed a normal distribution; Fisher's exact test was also performed. The significance level was α = 5%. Results: A total of 110 patients were included (pre-LTx, n = 35; post-LTx, n = 75). Different patients were investigated in the post-LTx and pre-LTx groups. Lack of use of supplemental oral-hygiene aids was noted. Between-group comparisons failed to find significant overall differences in DMFT and periodontal status. The post-LTx group showed fewer decayed teeth (P = 0.03). A total of 86% of patients pre-LTx and 84% of patients post-LTx were found to need dental treatment, and 60% of patients pre-LTx and 55% of patients post-LTx showed a need for periodontal treatment. The prevalence of Candida albicans was high; however, there were no statistically significant differences between the groups in regard to fungal infection. Conclusion: Improved dental care pre- and post-transplant, including screening for fungal infections, is recommended to avoid systemic infections in LTx patients. Increased attention to oral health care, and interdisciplinary collaboration to provide guidance, is needed to improve the oral health of patients before and after LTx.

Key words: Dental care, liver transplantation, oral health, oral hygiene

Introduction

Since the first liver transplant, which was performed by Starzl in 1963, there have been extensive improvements in surgical techniques, means of immunosuppression and perioperative intensive care; consequently, liver transplantation (LTx) is now the standard therapy in patients with irreversible liver failure1. In 2014 #bib1 #bib758 patients were transplanted in the Eurotransplant area, and 1 #bib918 patients were registered for LTx and on the waiting list2. Patients awaiting LTx are known to be in poor general health as a result of their underlying liver disease (e.g. hepatocellular carcinoma, ethyltoxic cirrhosis or viral hepatitis). Dental and periodontal diseases are risk factors for systemic complications in this vulnerable patient group3. Moreover, immunosuppressive medication might be a predisposing factor for oral diseases after LTx4., 5.. To avoid complications, early dental assessment and, if necessary, rehabilitation, should be performed before organ transplantation6., 7., 8.. Furthermore, patients awaiting LTx have been found to present an increased need for dental, periodontal or surgical treatment3., 9., 10.. It has also been shown that LTx candidates lack proper dental behaviour, resulting in a higher risk for, and greater prevalence of, dental disease10.

Data regarding the oral health of LTx recipients have not been extensively reported. According to a survey, which included patients who had undergone liver, kidney and heart transplantations, patients had poor oral status after solid organ transplantation11. Previous results for LTx have suggested a lack of preventive dental care, which, in combination with immunosuppression, leads to oral and mucosal diseases5. In this context, the significance of fungal infections should not be underestimated. Oral Candida infections increase the risk of invasive fungal infections, resulting in increased mortality and morbidity in organ-transplant patients12., 13..

Considering the need for improved dental care and early dental rehabilitation, patients after LTx (post-LTx) should present with improved oral conditions compared with patients before LTx (pre-LTx). However, current data show a lack of proper oral health behaviour and status in both groups6., 7., 8., 9., 10., 11., in contrast to the need for a comprehensive preventive programme for these patients. Limited data concerning these topics are available, and, to the best of the authors’ knowledge, studies comparing the oral health and dental behaviour of patients pre- and post-LTx are not available.

Therefore, the aim of this study was to investigate the dental and periodontal status, as well as the dental behaviour, of patients pre- and post-LTx. Thereby, different patients were investigated pre- and post-LTx. In addition, patients were screened for the presence of Candida to detect fungal colonisation of the oral cavity. Thus, the study's focus was not on the potential influence of transplantation on oral health, but rather to gain insight into the oral health of both patient groups. Therefore, it sought to determine whether early dental rehabilitation of patients pre-LTx, and sufficient maintenance of patients post-LTx, should be performed, as suggested in the literature6., 7., 8., 9., 10., 11.. It was hypothesised that post-LTx, patients would show improved oral health and dental behaviour compared with patients awaiting LTx.

Methods

This clinical, single-centre cross-sectional study was reviewed and approved by the Ethics Committee of the University Medical Center Göttingen, Germany (No. 43/9/07), and the research was conducted in full accordance with the World Medical Association's Declaration of Helsinki. The patients were informed verbally, as well as in writing, about the study and provided written informed consent to participate.

Patients

From 1 February to 31 July 2012, 47 patients pre-LTx and 119 patients post-LTx, treated in the Department of General, Visceral and Pediatric Surgery of the University Medical Center Göttingen, were asked to participate in the study. Because this study was a cross-sectional study, different patients pre- and post-LTx were evaluated.

Pre-LTx group

Patients registered on the Eurotransplant waiting list for LTx in the Department of General and Visceral Surgery of the University Medical Center Göttingen were asked to participate in the study.

Post-LTx group

Patients who had undergone LTx, irrespective of the time span since transplantation, were asked to participate in the context of a regular/routine subsequent appointment at the transplantation outpatient clinic of the University Medical Center Göttingen.

The following exclusion criteria were applied equally to both groups: patients <18 years old; the presence of an additional infectious disease [human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection or tuberculosis (TBC)]; a seizure or nervous disorder; and the inability to undergo oral examinations.

Patient questionnaire

Patients in both groups were asked to complete a standardised anamnestic questionnaire. Questions were asked about general illnesses, general medications, the reason for transplantation and, in the case of post-LTx, the date of transplantation and current immunosuppressive therapy. In a separate dental anamnesis, the patients were asked whether information about the association between oral health and LTx had been provided and whether a dental check-up or comprehensive dental treatment had occurred before transplantation or registration on the Eurotransplant waiting list (yes/no, when). In addition, the patients were questioned about their personal oral-hygiene behaviour (toothbrush, fluoride gel, dental floss, etc.) and whether their dental visit was routine- or complaint-oriented.

Oral examination

All patients were examined under standardised conditions by an experienced dentist at the dental clinic of the University Medical Center Göttingen, and the examination included investigation of the oral mucosa, dental findings and periodontal status.

Inspection of the oral mucous membranes

At the beginning of the examination, the oral mucous membranes were examined visually.

Dental findings

The decayed, missing and filled teeth (DMFT) index was assessed visually using a mirror and probe. Based on the number of decayed, missing and filled teeth, the DMFT index was determined. All teeth with reasonable suspicion of, or definitely showing, a cavity in the dentin layer were assigned to the D (=decayed) component; filled and crowned teeth were evaluated using component F (=filled); and missing teeth were assigned to the M (=missing) component. The DMFT index generally reflects the caries experience of the person examined. In addition, the degree of caries restoration (%) was calculated according to the following equation: [FT/(DT + FT) × 100] [e.g. the ratio of filled teeth (FT) to decayed teeth (DT) plus filled teeth (FT)]14.

Periodontal status

Classification of gingival inflammation was performed using the papillary bleeding index (PBI). For this purpose, a periodontal probe (PCP 15; Hu-Friedy, Chicago, IL, USA) was used to evaluate bleeding of the marginal gingiva. The PBI ranged from a score of 0 (no bleeding/inflammation-free gingiva) to 4 (profuse bleeding/severe inflammation)15. For the investigation of periodontal status, periodontal probing depth (PPD) and bleeding on probing (BOP: positive), as well as clinical attachment loss (CAL), were assessed at six measurement points per tooth using a periodontal probe with a millimeter-scale. According to the definition of Page and Eke, there were three categories of periodontitis: (i) severe periodontitis; (ii) moderate periodontitis; and (iii) no/mild periodontitis16. The need for periodontal treatment was defined in accordance with a periodontal screening record/periodontal screening index (PSR®/PSI) score of 3 or 4 based on PPD (>3 mm)17.

Mycological screening

To screen for the presence of fungi, swabs from the oral mucosa in the area of the cheek, palate, tongue and edentulous jaw were obtained, streaked onto Candida Chromagar (Oxoid, Wesel, Germany) and incubated at 35 °C overnight. Colonies of different morphologies and/or colours were counted and their species was determined using matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry (MALDI-ToF MS) (MALDI Biotyper; Bruker Daltonics, Bremen, Germany). Species not positively identifiable by MALDI-ToF were identified by sequencing of the internal transcribed spacer locus18.

Statistical analysis

The data were entered prospectively into a Microsoft Excel-based database (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA). Statistical analyses were performed using the SPSS Statistics statistical software package, version 15® (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). For numerical data, the comparison of mean values was performed using the Student's t-test or the Mann–Whitney U-test, depending whether or not the data were normally distributed. Categorical variables were analysed using Fisher's exact test. A value of P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Patients

In the pre-LTx group, a total of 35 of 47 patients were included (participation quota: 75%); and for the post-LTx group #bib75 of 119 patients were included (participation quota: 63%). The patients who were not included did not meet the inclusion and exclusion criteria and/or provided no informed consent. The average age for patients in the pre-LTx group was 54.9 ± 8.5 years compared with 56.7 ± 12.3 years for patients in the post-LTx group. All demographic data and underlying liver diseases for transplantation are shown in Table 1. Overall, there was no significant difference between the groups.

Table 1.

Characteristics of patients before (pre-LTx group, n = 35) and after (post-LTx group, n = 75) liver transplantation

| Characteristic | Pre-LTx group | Post-LTx group | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex (male) | 51 (18) | 64 (48) | >0.05 |

| Age, years (range) | 54.9 ± 8.5 (32–66) | 56.7 ± 12.3 (21–75) | >0.05 |

| Smoking habits | |||

| Smoker | 39 (12/31) | 21 (14/68) | >0.05 |

| Non-smoker | 61 (19/31) | 79 (54/68) | |

| Causal underlying disease | |||

| HCC | 6 (2) | 16 (12) | >0.05 |

| Viral hepatitis | 17 (6) | 27 (20) | |

| EC | 49 (17) | 35 (26) | |

| Cryptogenic | 20 (7) | 12 (9) | |

| Other | 9 (3) | 10 (8) | |

| Comorbidities | |||

| Diabetes | 23 (8) | 36 (27) | >0.05 |

| CHD | 11 (4) | 7 (5) | |

| Arterial hypertension | 43 (15) | 49 (37) | |

| Kidney disease | 23 (4) | 20 (15) | |

| Osteoporosis | 9 (3) | 12 (9) | |

| GID | 9 (3) | 4 (3) | |

| Time after LTx | |||

| Years (range) | – | 4.8 ± 4.2 (1–16) | – |

| >1–5 years | – | 57 (43) | |

| >5 years | – | 29 (22) | |

| Immunosuppressive therapy | |||

| Cyclosporine | – | 12 (9) | – |

| Mycophenolate-mofetil | – | 51 (38) | |

| Tacrolimus | – | 64 (48) | |

| Sirolimus | – | 8 (6) | |

| Everolimus | – | 9 (7) | |

| Glucocorticosteroids | – | 33 (25) | |

CHD, coronary heart disease; EC, ethyltoxic cirrhosis; GID, gastrointestinal disease; HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma.

Data are given as % (n) or mean ± standard deviation (range).

The significance level was P < 0.05.

Patient questionnaire

The results of the patient questionnaire concerning dental check-ups and oral-hygiene behaviour are provided in Table 2. The number of returned answers is also displayed in Table 2 because not every patient answered each question. There were no significant differences between the two groups.

Table 2.

Questionnaire data obtained from patients before (pre-LTx group) and after (post-LTx group) liver transplantation

| Variable | Pre-LTx group | Post-LTx group | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Regular contact with a dentist | 64 (21/33) | 67 (45/67) | >0.05 |

| Reason for visiting a dentist | |||

| Control | 75 (21/28) | 60 (42/70) | >0.05 |

| Complaint | 22 (6/27) | 22 (15/67) | |

| Last dental examination | |||

| 0–3 months | 53 (16/30) | 56 (38/68) | >0.05 |

| 3–12 months | 23 (7/30) | 35 (24/68) | |

| >12 months | 23 (7/30) | 9 (6/68) | |

| Dental treatment before LTx | 62 (13/21) | 75 (48/64) | >0.05 |

| Information about antibiotic prophylaxis | 52 (16/31) | 78 (43/55) | >0.05 |

| Oral hygiene: toothbrushing | |||

| Less than once daily | 4 (1/26) | 11 (6/57) | >0.05 |

| Once or twice daily | 62 (16/26) | 68 (39/57) | |

| More than twice daily | 35 (9/26) | 25 (14/57) | |

| Oral hygiene aids | |||

| Manual toothbrush | 76 (22/29) | 70 (47/67) | >0.05 |

| Power toothbrush | 34 (10/29) | 42 (28/67) | |

| Dental floss/interdental brush | 14 (4/29) | 27 (18/67) | |

| Mouth rinse | 38 (11/29) | 48 (32/67) | |

| Fluoride gel | 0 | 10 (7/67) | |

Data are given as % (n). The total numbers differ because not every patient answered every question.

The significance level was P < 0.05.

Oral examination

Inspection of oral mucous membranes

No abnormalities or overgrowth of the oral mucosa were detected. Furthermore, no signs of Candida infection were found.

Dental findings (DMFT)

The dental findings of the patients in both groups are shown in Table 3. Five patients in each group were edentulous and therefore were not included in the calculation of DMFT. An overall significant difference between the groups was not found. However, the post-LTx group showed decidedly fewer decayed teeth (DT; P = 0.03). The degree of caries restoration was significantly higher in the post-LTx group, with a median of 100% (P = 0.04). Overall, the vast majority of patients in both groups showed a great need for dental treatment at the time of examination (86% and 84% of patients in the pre-LTx and the post-LTx groups, respectively).

Table 3.

Comparison of the oral health parameters in patients before (pre-LTx group, n = 35) and after (post-LTx group, n = 75) liver transplantation (LTx)

| Oral health parameters | Pre-LTx group | Post-LTx group | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| DMFT all patients | 23.7 ± 4.0 (10–28) | 22.8 ± 5.2 (11–28) | 0.47 |

| Edentulous patients | 11 (4) | 7 (5) | 0.26 |

| DMFT patients with teeth | 23.1 ± 3.9 (10–28) | 22.4 ± 5.2 (11–28) | 0.74 |

| DT patients with teeth | 2.5 ± 2.8 (0–11) | 1.2 ± 2.0 (0–11) | 0.03 |

| MT patients with teeth | 12.1 ± 6.9 (4–26) | 12.2 ± 7.6 (0–27) | 0.76 |

| FT patients with teeth | 8.6 ± 6.1 (0–19) | 8.9 ± 5.3 (0–20) | 0.82 |

| Degree of caries restoration | 84.6 (0–100) | 100 (0–100) | 0.04 |

| Gingival inflammation (PBI) | 0.52 ± 0.53 (0–1.40) | 0.55 ± 0.73 (0–2.85) | 0.82 |

| Periodontitis | |||

| No/mild | 17 (6) | 28 (21) | 0.67 |

| Moderate | 46 (16) | 49 (37) | 0.69 |

| Severe | 26 (9) | 16 (12) | 0.30 |

| Need for treatment | |||

| Dental | 86 (30) | 84 (63) | 1.00 |

| Periodontal | 60 (21) | 55 (41) | 0.68 |

DMFT, number of carious, missing and filled teeth (caries index); DT, carious teeth; FT, filled teeth; MT, missing teeth; PBI, papillary bleeding index.

Data are given as % (n), mean ± standard deviation or median (range).

Significance level was P < 0.05.

Significant results are in bold.

Periodontal status

Papillary bleeding index was similar in both groups. Periodontal findings were also not significantly different between the groups. With 60% and 55% of patients in the pre-LTx and the post-LTx groups, respectively, demonstrating a need for periodontal treatment (Table 3).

Candida screening

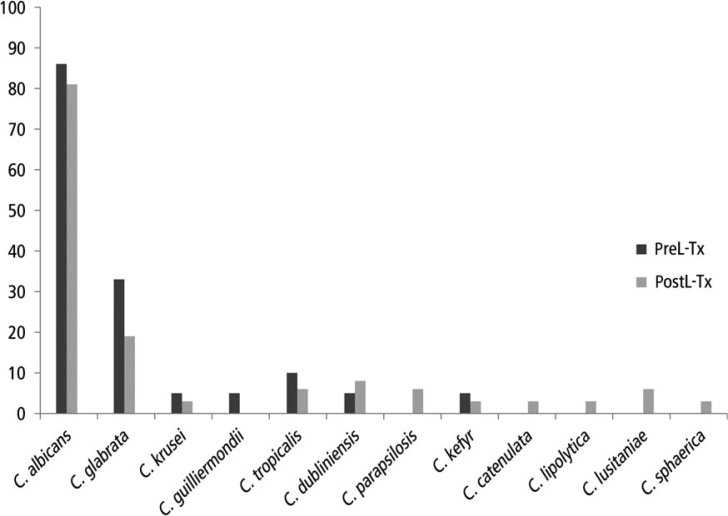

Twenty-one patients in the pre-LTx group and 36 patients in the post-LTx group were screened for fungi. Except for rare yeast species (Candida catenulata, Candida lipolytica, Candida lusitaniae and Candida sphaerica) being observed in the post-TX group, there was no significant difference in the occurrence of different species (Figure 1). In both groups, Candida albicans was the most common species of yeast, having a prevalence of 86% in patients pre-LTx and 81% in patients post-LTx (P = 0.18), followed by C. glabrata which was present in 33% of patients pre-LTx and in 19% of patients post-LTx) (P = 0.12).

Figure 1.

Findings of Candida species in the oral cavities of patients before (pre-LTx group, n = 21) and after (post-LTx group, n = 36) liver transplantation (LTx). Data are given as %. No significant differences were found between the groups (P > 0.05).

Discussion

Supplemental oral hygiene aids (i.e. dental floss, fluoride gel) was shown for all patients pre- and post-LTx. The majority of patients in both groups needed dental treatment, and more than half of the patients in each group also required periodontal treatment. Regarding Candida species, no significant differences between the groups was found. Candida albicans was detectable in the majority of patients.

Before interpretation of the results, it must be emphasized that different patients were investigated pre- and post-LTx in this cross-sectional study. Therefore, this limits any comparison between the two groups in the current study.

A previous cross-sectional study performed in our centre showed that information on oral health is rarely standardised across transplant centres, and both patients on the Eurotransplant waiting list and those who have received solid organ transplants (SOT) presented with poor oral health and dental status11. Comparing our results with the former study, a significantly higher number of patients received dental treatment before transplantation in the current population – 75% in the present study compared with 30% in the former study – indicating a greater awareness of oral health in transplant patients and especially within the transplant centre11. The use of supplemental oral hygiene aids, especially of dental floss, was higher in the previous study11. However, similar values for DT were found in the previous study (2.9 pre-SOT and 1.4 post-SOT), with no significant differences between groups, in contrast with the findings of the current study for LTx patients11. A Spanish study by Díaz-Ortiz et al.5 also demonstrated a lack of supplemental oral hygiene aids, but it also showed that only 41.5% of patients underwent dental treatment before LTx, which was nearly half of the number of patients undergoing dental treatment before LTx in the present study.

The present study did not investigate a healthy control group; however, the results can be discussed in relation to the fourth and fifth German oral health study (DMS IV and DMS V, respectively)19., 20., a representative study of the German population21. In this regard, our patients must be placed, in age, between the two age groups 35–44 and 65–74 years; in the present study patients had average ages of 54.9 and 56.7 years in the pre-LTx and post-LTx groups, respectively. The DMFT scores were, overall, slightly higher than in the 65–74 years age group in the DMS IV and DMS V (24.6 ± 5.3 pre-LTx and 23.7 ± 6.3 post-LTx). In particular, the DT values (2.2 ± 2.8 pre-LTx and 1.1 ± 1.9 post-LTx) were higher in both groups, indicating a slightly increased prevalence of caries in our patients compared with the general population (Table 4)19. Thus, the need for dental treatment remains high in patients with planned or previous LTx.

Table 4.

Dental [decayed, missing and filled teeth (DMFT)] and periodontal (need for periodontal treatment, PSR®/PSI) findings of the Fourth German Oral Health Study (DMS IV) and the present study

| Oral finding | DMS IV (2006) | DMS V (2016) | Present study | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age group 35–44 years | Age group 65–74 years | Age group 35–44 years | Age group 65–74 years old | Pre-LTx group 54.9 years | Post-LTx group 56.7 years | |

| DMFT | 14.5 ± 5.7 | 22.1 ± 5.9 | 11.2 | 17.7 | 24.6 ± 5.3 | 23.7 ± 6.3 |

| DT | 0.5 | 0.3 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 2.2 ± 2.8 | 1.1 ± 1.9 |

| MT | 2.4 | 14.1 | 2.1 | 11.1 | 14.8 ± 9.8 | 14.2 ± 9.5 |

| FT | 11.7 | 7.7 | 8.6 | 6.1 | 7.6 ± 6.4 | 8.4 ± 5.5 |

| Prevalence of periodontitis | ||||||

| No/mild | 27 | 19 | 49 | 35 | 19 | 30 |

| Moderate | 53 | 52 | 43 | 45 | 52 | 53 |

| Severe | 20 | 29 | 8 | 20 | 29 | 17 |

| Need for periodontal treatment (PSR®/PSI) | ||||||

| No (score 0–2) | 26.5 | 12 | 41 | 25 | 40 | 45 |

| Yes (score 3–4) | 73.5 | 88 | 59 | 75 | 60 | 55 |

DT, decayed teeth; FT, filled teeth; MT, missing teeth; PSR, periodontal screening record; PSI, periodontal screening index.

Data are given as % or mean ± standard deviation.

Regarding periodontal health, there was no significant difference with reference to the severity of periodontitis between the two groups in our study. Most patients were found to present with mild or moderate periodontitis. Compared with the results of the DMS IV and DMS V groups, there were fewer with severe periodontitis and therefore the need for periodontal treatment (60% of patients pre-LTx and 55% of patients post-LTx). This finding was also less pronounced than in the general population (Table 4)19., 20. and compared with the results of our former investigation11. A potential reason for the less severe periodontal condition, especially in the post-LTx group, could be the immunosuppressive medication. It has been shown that such medication might reduce periodontal inflammation22. A further reason could be periodontal treatment before organ transplantation. However, this remains speculative. The international literature has shown contradictory results, in which stable clinical periodontal conditions were reported for a period of 10 years in patients post-LTx23. In contrast, worse periodontal conditions were detected for cirrhotic patients and patients post-LTx compared with healthy controls24. Furthermore, similar results to those of the present study were found for patients before and after kidney transplantation25.

Several studies have investigated LTx candidates regarding dental and periodontal findings3., 8., 9., 10., 26.. For instance, Rustermeyer et al.3 showed that 64% of patients presented with a need for periodontal treatment before solid organ transplantation3, a value that is only slightly higher than the corresponding value in the present study. Lins et al.9 also found a high treatment need, and a reduction of mortality appeared to be associated with dental treatment. In accordance, previous studies of LTx candidates have concluded that there is a need to improve pretransplant dental treatment and prevention3., 9., 10., 26.. This demand is supported by the results of the current study. A major influencing factor could be a lack of consistent oral-hygiene behaviour, especially in the form of supplemental oral hygiene (i.e. use of dental floss and/or fluoride gel). A further problem appeared to be the high burden and the changes in lifestyles of the LTx candidates, leading to a reduced priority for dental care10. Nevertheless, early dental rehabilitation should be performed before transplantation. Instruction in, and motivation for, oral hygiene, as well as good periodontal maintenance, should help to prevent systemic complications in the vulnerable group of post-transplant patients. However, it must be considered that in the present study the same patients were not investigated both pre- and post-LTx, and the time after LTx was an average of 4.8 years. Consequently, it is possible that the oral health status immediately after LTx was better than at the time of investigation. Nevertheless, this outcome would also demonstrate a lack of maintenance among these vulnerable patients.

A further aspect was the screening of patients for the presence of Candida. The influence of immunosuppressive medication on the occurrence of Candida species cannot be concluded from our results. Dongari-Bagtzoglou et al.12 investigated colonisation of Candida species in patients after kidney and heart transplantation, and compared the results with those of a healthy control population. In contrast to their results, the prevalence of C. albicans, C. glabrata and C. tropicalis was shown to be markedly higher in our population pre- and post-LTx, than in their patients after solid transplantation. Therefore, an influence of the underlying hepatic disease on the occurrence of Candida species seems possible. Based on recent review articles, the prevalence of C. albicans in healthy adults ranges between 30% and 45%27., 28.. Compared with this rate, both the pre-LTx and post-LTx patients in the current study showed a higher prevalence of C. albicans. However, it is not possible to determine whether or not this high prevalence was pathologic, especially considering that no clinical manifestations of Candida infection were found.

Badiee et al.13 found LTx patients with Candida colonisation to be at risk for invasive fungal infections; therefore, they recommended control of fungal colonisation in transplanted patients. The high prevalence of Candida species in the current study, especially C. albicans, supports this recommendation. In accordance with this finding, screening for Candida species and corresponding therapy could be part of a special-care programme for transplant patients.

This study was, to the best of our knowledge, the first to compare dental, periodontal and fungal findings, as well as oral behaviour, in patients before and after LTx. It serves as a comprehensive overview and indicates problems in the care of LTx patients. However, this study was limited by the lack of a healthy control group. Similarly to the studies carried out previously by this working group11., 24., the fourth and fifth German oral health studies were used as a reference for the healthy general German population19., 20.. The German oral health study provides population-based, nationally representative data21, so this large study serves as an adequate but surrogate control group. Therefore, recruitment of a healthy control group was not essential. However, the conditions of data acquisition were not the same for both the present study and the German oral health study, adversely affecting the ability to compare results between the studies. Furthermore, while the dental examination was the same for both studies, periodontal examination was different in the German oral health study. There, for 10% of the patients a six-point full-mouth periodontal recording was executed. Based on these findings, a so-called inflation factor was calculated for determining the disease burden of all patients20., 21.. In the current study, for all patients a six-point full-mouth periodontal recording was performed.

Nevertheless, for sufficient interpretation of the fungal findings, a healthy control group is necessary. Furthermore, that different patients were investigated before and after transplantation was a limitation, but this patient group is very ill, and recruitment of suitable patients is difficult. In spite of these adverse factors, a total of 110 patients were included in the current study. A further limitation was the number of comorbidities (e.g. diabetes, coronary heart diseases, kidney diseases, etc.), which might have influenced oral health and behaviour. However, there were no significant differences between groups regarding this variable. Furthermore, it must be considered that the current investigation was performed as a cross-sectional study and is not a case–control study.

There is a vital need for guidelines on the dental care of patients before and after LTx. In addition, transplant candidates and recipients must be informed early about the importance of oral health. Interdisciplinary collaboration between dentists and physicians is strongly recommended.

Conclusion

Before and after LTx, patients presented a need for dental and periodontal treatment and showed deficiencies in oral hygiene behaviour. Consequently, improved pre- and post-transplant treatment (e.g. in the form of special-care programmes with maintenance care) are recommended. Screening and therapy for fungal infections should be part of these special care programmes to avoid systemic infections.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Agnieszka Goretzki for expert technical assistance. Furthermore, the authors thank Dr. Florian Widmer for the oral and dental examinations of patients and Prof. Dr. Rainer F. Mausberg for his helpful advice and support in the execution of the study. This study did not receive any financial support.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Starzl TE. History of clinical transplantation. World J Surg. 2000;24:759–782. doi: 10.1007/s002680010124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.EuroTransplant. Available from: www.eurotransplant.org. Accessed 1 October 2015.

- 3.Rustemeyer J, Bremerich A. Necessity of surgical dental foci treatment prior to organ transplantation and heart valve replacement. Clin Oral Investig. 2007;11:171–174. doi: 10.1007/s00784-007-0101-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Helenius-Hietala J, Ruokonen H, Grönroos L, et al. Oral mucosal health in liver transplant recipients and controls. Liver Transpl. 2014;20:72–80. doi: 10.1002/lt.23778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Díaz-Ortiz ML, Micó-Llorens JM, Gargallo-Albiol J, et al. Dental health in liver transplant patients. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal. 2005;10:72–76. 66–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Guggenheimer J, Eghtesad B, Stock DJ. Dental management of the (solid) organ transplant patient. Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Radiol Endod. 2003;95:383–389. doi: 10.1067/moe.2003.150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Maestre-Vera JR, Gómez-Lus Centelles ML. Antimicrobial prophylaxis in oral surgery and dental procedures. Med Oral Cir Bucal. 2006;12:E45–E52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Silva Santos PS, Fernandes KS, Gallottini MH. Assessment and management of oral health in liver transplant candidates. J Appl Oral Sci. 2012;20:241–245. doi: 10.1590/S1678-77572012000200020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lins L, Bittencourt PL, Evangelista MA, et al. Oral health profile of cirrhotic patients awaiting liver transplantation in the Brazilian Northeast. Transplant Proc. 2011;43:1319–1321. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2011.03.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Guggenheimer J, Eghtesad B, Close JM, et al. Dental health status of liver transplant candidates. Liver Transpl. 2007;13:280–286. doi: 10.1002/lt.21038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ziebolz D, Hraský V, Goralczyk A, et al. Dental care and oral health in solid organ transplant recipients: a single center cross-sectional study and survey of German transplant centers. Transpl Int. 2011;24:1179–1188. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-2277.2011.01325.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dongari-Bagtzoglou A, Dwivedi P, Ioannidou E, et al. Oral Candida infection and colonization in solid organ transplant recipients. Oral Microbiol Immunol. 2009;24:249–254. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-302X.2009.00505.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Badiee P, Kordbacheh P, Alborzi A, et al. Fungal infections in solid organ recipients. Exp Clin Transplant. 2005;3:385–389. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.WHO . 4th ed. WHO, Oral Health Unit; Geneva: 1997. World Health Organization: Oral Health Surveys, Basic Methods. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lange DE, Plagmann HC, Eenboom A, et al. Clinical methods for the objective evaluation of oral hygiene. Dtsch Zahnärztl Z. 1977;32:44–47. [in German]. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Page RC, Eke PI. Case definitions for use in population-based surveillance of periodontitis. J Periodontol. 2007;78:1387–1399. doi: 10.1902/jop.2007.060264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Diamanti-Kipioti A, Papapanou TN, Moraitaki-Zamitsai A, et al. Comparative estimation of periodontal conditions by means of different index systems. J Clin Periodontol. 1993;20:656–661. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051x.1993.tb00711.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chen YC, Eisner JD, Kattar MM, et al. Identification of medically important yeasts using PCR-based detection of DNA sequence polymorphisms in the internal transcribed spacer 2 region of the rRNA genes. J Clin Microbiol. 2000;38:2302–2310. doi: 10.1128/jcm.38.6.2302-2310.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Micheelis W, Schiffner U. Deutscher Zahnärzte Verlag DÄV; Köln: 2006. The Fourth German Oral Health Study (DMS IV) Institut der Deutschen Zahnärzte (Hrsg.); (IDZ Materialienreihe Band 31). [in German]. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jordan RA, Micheelis W. Deutscher Zahnärzte Verlag DÄV; Köln: 2016. The Fifth German Oral Health Study (DMS V) Institut der Deutschen Zahnärzte (Hrsg.); (IDZ Materialienreihe Band 35). [in German]. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jordan RA, Bodechtel C, Hertrampf K, et al. The Fifth German Oral Health Study (Fünfte Deutsche Mundgesundheitsstudie, DMS V) – rationale, design, and methods. BMC Oral Health. 2014;14:161. doi: 10.1186/1472-6831-14-161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Alani A, Seymour R. Systemic medication and the inflammatory cascade. Periodontol 2000. 2000;64:198–210. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0757.2012.00454.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Machtei EE, Falah M, Oettinger-Barak O, et al. Periodontal status in post-liver transplantation patients: 10 years of follow-up. Quintessence Int. 2012;43:879–885. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Oettinger-Barak O, Barak S, Machtei EE, et al. Periodontal changes in liver cirrhosis and post-transplantation patients. I: clinical findings. J Periodontol. 2001;72:1236–1240. doi: 10.1902/jop.2000.72.9.1236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schmalz G, Kauffels A, Kollmar O, et al. Oral behavior, dental, periodontal and microbiological findings in patients undergoing hemodialysis and after kidney transplantation. BMC Oral Health. 2016;16:72. doi: 10.1186/s12903-016-0274-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Helenius-Hietala J, Aberg F, Meurman JH, et al. Increased infection risk postliver transplant without pretransplant dental treatment. Oral Dis. 2013;19:271–278. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-0825.2012.01974.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Patil S, Rao RS, Majumdar B, et al. Clinical appearance of oral candida infection and therapeutic strategies. Front Microbiol. 2015;6:1391. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2015.01391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Akpan A, Morgan R. Oral candidiasis. Postgrad Med J. 2002;78:455–459. doi: 10.1136/pmj.78.922.455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]