Abstract

Introduction: High levels of patients’ pain and anxiety characterise dental emergencies. The main objective of this study was to examine the self-reported attitudes of dental students towards these parameters in emergency conditions. A secondary objective was to determine if individual parameters (gender, personal experience of dental pain, personal dental anxiety and year of study) might affect their attitudes. Methods: One-hundred and eighty-seven undergraduate dental students with clinical practice completed a multiple-choice self-administered questionnaire online. The aforesaid individual parameters were collected and the students were asked to rate the frequency of their behaviour towards items representing good management of patients’ pain and anxiety. The chi-square test of independence, Fisher's exact test and multiple logistic regression models were used for statistical analysis. Results: Oral assessment of anxiety before treatment was scarce and was significantly associated with the students having personally experienced dental pain (P = 0.007). Pre-, intra- and postoperative pain appeared to be managed unequally by the students. Male students were significantly less likely to inform patients about postoperative pain (P = 0.014). More clinical experience was associated with less systematic consideration for intra-operative pain (P < 0.05). Being dentally anxious showed no significant association with higher frequencies of behaviours towards patients’ pain and anxiety. Conclusions: These findings highlight the need for educational improvement regarding pain and anxiety in emergency conditions, especially concerning the assessment methods and continuity in the control of pain. Emergency dental care appears to be a very suitable field for contextual learning.

Key words: Anxiety, dental education, emergency, ethics, pain

Introduction

From a pragmatic point of view, efficient management of dental emergencies implies that dentists make a reliable diagnosis and quickly perform the corresponding treatment. However, high levels of anxiety and pain in patients characterise dental emergencies1: the use of medical care is mainly motivated by the presence of existing pain2 and patients often do not seek a consultation until the pain is unbearable, leading to an emergency seeking-care pattern3., 4.. In acute-pain situations, pain and anxiety are indistinguishable and have a synergic action: perceived or anticipated pain increases anxiety and the latter not only lowers the pain threshold but may also lead to the perception of normally non-painful stimuli as painful5. Therefore, these parameters have to be jointly assessed and managed during emergency care in order to avoid the damaging impact of a traumatic experience for the patient, potentially initiating or increasing dental anxiety by a conditioning pathway6. Dental anxiety may lead to avoidance behaviour regarding dental care, favouring poor oral conditions, acute painful episodes and major repercussions on patients’ daily lives by affecting general health, social life and work performance7., 8.. Moreover, anxious patients are likely to use emergency consultations as a pattern for dental care, despite the highly stressful context, leading to a vicious cycle of dental fear, pain and emergency consultation needs9. As emergency care can be the first step to access routine dental treatment, particular attention should be paid to these situations. Comprehensive behaviour, considering both technical and relational aspects, should be adopted by dentists. As a consequence, taking into account patients’ anxiety and pain should be considered as being just as important as the technical procedures when evaluating students’ skills in a patient-centred approach to dental education10.

The purpose of this study was to examine the self-reported attitudes of dental students towards patients’ pain and patients’ anxiety in dental emergency conditions and to evaluate the need for improvement of the teaching methods regarding these topics. To the best of our knowledge, no study has yet investigated this issue. As the students involved in the present research had followed the same education programme, a second objective was to determine if individual parameters (gender, personal experience of dental pain, personal dental anxiety and year of study) might affect their attitudes.

Methods

Educational framework

A descriptive, cross-sectional study was conducted at the Dental School of the University of Aix-Marseille (Marseille, France). In France, 6 years are required to graduate from dental school. In the preclinical period (year 1 to year 3), education remains theoretical. At Marseille Dental School the students begin to be sensitised to patients’ dental anxiety in year 3, through psychology courses. Anaesthesiology and pharmacology are taught in the same year. Classes directly related to pain and anxiety management take place during the first semesters of years 4 and 5. In year 4, the lecture is focussed on these topics in emergency conditions, while in year 5 it refers to child dental care. In year 6, no courses involve any topics related to pain and/or anxiety management. As soon as the students begin to provide dental care (from year 4 to year 6), management of emergency care situations is a mandatory part of their training. The diagnosis and treatment stages are supervised by various senior instructors whose clinical practice in the hospital is not limited to emergency care. During emergency care, students do not use anxiety evaluation scales.

Participants

All undergraduate dental students having clinical practice involving emergency patients (i.e. students in years 4–6) were involved in the survey, yielding a total of 238 students. A multiple-choice self-administered questionnaire entitled ‘Survey on the management of dental emergencies by dental students’ was sent to the students by e-mail. Each participant received a written explanation of the terms of the study prior to participation. It specified that answering the questionnaire would involve no specific knowledge but personal experience, and that voluntary completion of the questionnaire was considered as informed consent to participate in the study.

The investigation conformed to the provisions of the Declaration of Helsinki, and the agreement of the Ethics Committee of Aix-Marseille University was obtained before starting. The survey was started by the end of the academic year considering that the students had to acquire professional experience to answer the questionnaire properly. Answering the questionnaire was conducted online and anonymously. Two recalls were sent with an intervening 15-day interval.

Questionnaire

Demographic data, including the age and gender of students and their year of study, were collected. The students were asked about their personal experience of dental pain (PEDP). PEDP was considered as positive if students reported a ‘yes’ answer to the question ‘Have you ever felt provoked and/or spontaneous dental pain?’. Dental anxiety among students was evaluated using the Modified Dental Anxiety Scale (MDAS), which consists of a validated self-assessment scale based on five questions related to projected anxiety regarding dental treatment11. Each question permitted assessment of anxiety on a scale ranging from 1 (not anxious) to 5 (extremely anxious). The addition of all scores provided a total (MDAS score), the minimum value being 5 (not anxious) and the maximum value being 25 (extremely anxious). Dental anxiety was considered as being present for an MDAS score of ≥ 11, with a score of 19 being considered as a breakpoint referring to dentally phobic subjects11.

Questions were developed regarding students’ attitudes in a dental emergency setting towards patients’ pain and patients’ anxiety (Table 1). All items were indicators of good management of these two parameters based on literature review12., 13., 14., 15., 16., 17., 18., 19., 20. (Table 2). In Table 1, items 1, 5 and 6 concern anxiety management and items 2, 3, 4, 7 and 8 concern pain management. Time support was divided into three stages: before, during and after dental treatment (pre-, intra- and postoperative periods). The students were asked to determine the frequency of their behaviour towards these items, ranking it from ‘never’ to ‘always’.

Table 1.

Repartition of the students’ self-declared frequency of behaviours regarding patients’ pain and patients’ anxiety (n = 187)

| Questions developed | LFB (%) | HFB (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Never | Occasionally | Often | Always | ||

| When receiving an emergency patient, before starting to treat… | |||||

| Item 1 | … you ask the patient about his/her dental anxiety. | 19.3 | 47.1 | 24.6 | 9.0 |

| Item 2 | … you ask the patient about existing dental pain. | 1.1 | 2.1 | 4.3 | 92.5 |

| When receiving an emergency patient, during treatment… | |||||

| Item 3 | … if the gesture requires anaesthesia you ask the patient about the efficacy of anaesthesia. | 3.8 | 20.3 | 20.3 | 55.6 |

| Item 4 | … you ask the patient about pain provoked by your procedure. | 3.2 | 11.2 | 21.9 | 63.7 |

| Item 5 | … you provide the patient reassuring words. | 0 | 7.0 | 34.7 | 58.3 |

| Item 6 | … you allow the patient to suspend treatment by a gesture or a word. | 1.1 | 7.0 | 13.9 | 78.0 |

| When receiving an emergency patient, after treatment… | |||||

| Item 7 | … you inform the patient about the possibility of postoperative pain. | 0.5 | 13.9 | 35.8 | 49.8 |

| Item 8 | … you consider the necessity for a painkiller prescription. | 1.6 | 24.1 | 40.6 | 33.7 |

Values are given as a percentage. Bold values indicate proportion of systematic behaviour. HFB, high-frequency behaviour; LFB, low-frequency behaviour.

Table 2.

Overview of the management strategies for patients’ anxiety and pain in dentistry, as recommended in the literature

| Recommended ways to manage patients’ pain and anxiety | Authorsref. no. |

|---|---|

| Asking the patient about anxiety before dental treatment | Corah et al.12 |

| Lodge & Tripp14 | |

| Armfield et al.18 | |

| Using a dental anxiety scale prior to dental treatment | Dailey et al.16 |

| De Jongh et al.17 | |

| Allowing the patient to withdraw care (‘providing control’) | O'Shea et al.13 |

| De Jongh et al.17 | |

| Providing effective anaesthesia | O'Shea et al.13 |

| De Jongh et al.17 | |

| Brahm et al.20 | |

| Taking into account pain as a symptom, an intra-operative issue and a possible consequence of the treatment | O'Shea et al.13 |

| Desjardins15 | |

| Brahm et al.20 | |

| Briefing the patient on possible postoperative pain | Desjardins15 |

| Muglali & Komerik19 | |

| Considering prescription of appropriate painkillers | Desjardins15 |

| Muglali & Komerik19 |

Statistical analysis

The chi-square test of independence or Fisher's exact test was used, as appropriate, to test the association between two categorical variables. For multivariate analysis, multiple logistic regression models were performed to test the factors associated with dependent variables representing some behaviours towards pain and anxiety. The items representing these behaviours were previously recoded into binary variables: low-frequency behaviours (LFB) (‘never’ or ‘occasionally’ answers) versus high-frequency behaviours (HFB) (‘often’ or ‘always’ answers). For statistical reasons, five of the items were used as a dependent variable in a multiple binary logistic regression model. In each of these models, we systematically adjusted for sex and year of study and we were particularly interested in the search for significance of the PEDP and the ‘presence of a dental anxiety’ variables. The event modelled was having reported HFB to the considered binary item.

Statistical analysis was performed using SAS 9.4 Software (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA), specifically through use of the FREQ and LOGISTIC procedures, and the significance level used was 0.05.

Results

General characteristics

Of the 238 students involved in the study, 187 returned the questionnaire, yielding a global response rate of 78.6% (with no questionnaire being excluded from the analysis). Response rate according to year of study was 88% for students in year 4, 76.1% for students in year 5 and 69.4% for students in year 6.

The age of the participants ranged from 20 to 35 [mean ± standard deviation (SD): 23.47 ± 1.99] years and 61% of the respondents were women. PEDP was reported by 51.3% of the respondents. The MDAS score among students ranged from 5 to 22 (mean ± SD: 8.89 ± 3.15). Dental anxiety was present in 27.3% of the sample (MDAS score ≥ 11).

Self-reported students’ attitudes regarding pain and anxiety

A majority of the students declared HFB regarding all items relative to management of pain and anxiety, except for the item ‘asking about dental anxiety’. Whereas 96.8% of the sample ‘often’ to ‘always’ asked patients about existing pain before treatment, only 33.6% did so for anxiety (Table 1).

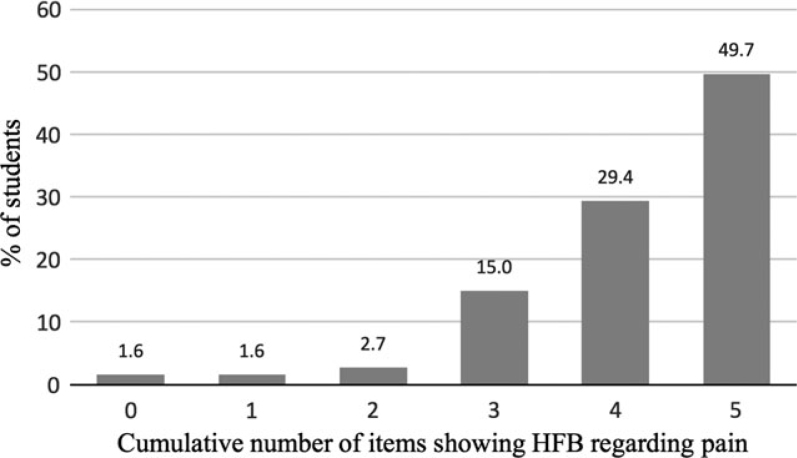

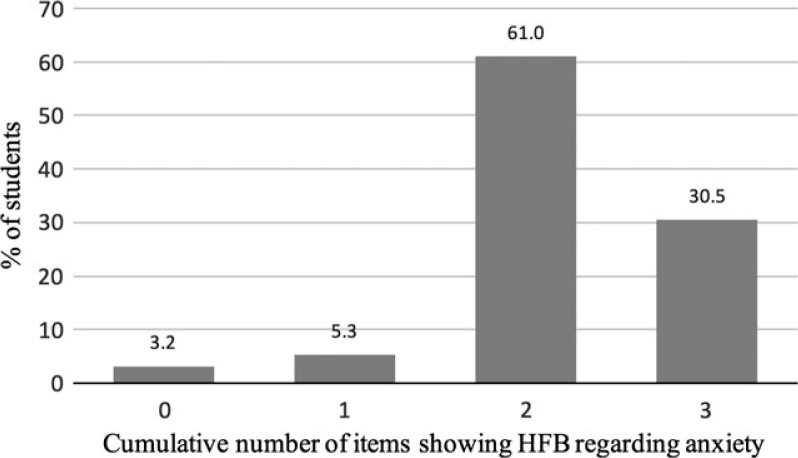

For each student, the number of items showing HFB regarding pain (five items) and the number of items showing HFB regarding anxiety (three items) were calculated. The results showed that 49.7% of the respondents declared HFB for all five items related to pain management and 29.4% did so for four items out of five (Figure 1). On the other hand, 30.5% of the students declared HFB for all three items relative to anxiety management and 61% did so for two items out of three (Figure 2). Among these, asking patients about their anxiety was the missing behaviour in 94.7% of cases. Often to always asking patients about their anxiety before treatment was significantly associated with the students having personally experienced dental pain (P = 0.007).

Figure 1.

Distribution of number of high-frequency behaviours (HFB) regarding pain among the students.

Figure 2.

Distribution of number of high-frequency behaviours (HFB) regarding anxiety among the students.

Systematic use of management techniques was analysed considering only the ‘always’ answers. Concerning anxiety, ‘providing control’ (78%) followed by ‘having reassuring words’ (58.3%) were the systematic behaviours most commonly implemented. Concerning pain, always asking patients about existing pain before starting to treat was performed by 92.5% of the students, while 63.7% systematically enquired about pain caused by the operative procedure, 55.6% systematically asked about the efficiency of anaesthesia, 49.8% systematically warned patients about possible postoperative pain and 33.7% always considered a painkiller prescription (Table 1).

Association of management behaviours with individual parameters

Among the items relating to management strategies, five out of eight were selected as dependent variables in the multiple logistic regression models (Table 3). These were items for which the proportion of answers reporting LFB and the proportion of answers reporting HFB were both greater than 10% (items 1, 3, 4, 7 and 8).

Table 3.

Multiple logistic regression models (n = 187)

| Asking the patient about anxiety | Asking the patient about the efficacy of anaesthesia | Asking the patient about pain provoked by procedure | Informing the patient about the possibility of postoperative pain | Considering the necessity for a painkiller prescription | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | 95% CI | P | OR | 95% CI | P | OR | 95% CI | P | OR | 95% CI | P | OR | 95% CI | P | |

| Gender | |||||||||||||||

| Female | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||||||||

| Male | 0.67 | 0.35–1.30 | 0.239 | 1.76 | 0.83–3.74 | 0.139 | 1.69 | 0.66–4.36 | 0.275 | 0.33 | 0.14–0.80 | 0.014 | 0.90 | 0.45–1.81 | 0.769 |

| Year of study | |||||||||||||||

| Sixth | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||||||||

| Fourth | 1.73 | 0.75–4.01 | 0.200 | 2.79 | 1.19–6.57 | 0.018 | 5.07 | 1.81–14.17 | 0.002 | 2.66 | 0.98–7.23 | 0.055 | 0.997 | 0.43–2.29 | 0.994 |

| Fifth | 1.78 | 0.74–4.30 | 0.198 | 3.16 | 1.28–7.81 | 0.013 | 5.74 | 1.90–17.33 | 0.002 | 3.74 | 1.19–11.76 | 0.023 | 1.49 | 0.59–3.71 | 0.396 |

| PEDP | |||||||||||||||

| No | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||||||||

| Yes | 2.40 | 1.25–4.61 | 0.009 | 1.93 | 0.93–4.01 | 0.078 | 1.71 | 0.69–4.20 | 0.245 | 0.83 | 0.34–2.00 | 0.680 | 0.51 | 0.25–1.03 | 0.060 |

| Presence of dental anxiety* | |||||||||||||||

| No | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||||||||

| Yes | 0.84 | 0.41–1.70 | 0.622 | 1.42 | 0.62–3.24 | 0.408 | 0.97 | 0.36–2.64 | 0.959 | 0.80 | 0.30–2.14 | 0.662 | 1.27 | 0.58–2.79 | 0.545 |

Modified Dental Anxiety Scale MDAS) score ≥ 11.

Bold values indicate statistical significance at the 0.05 level.

For each logistic regression, the event modelled was having reported high-frequency behaviour (HFB).95% CI, 95% confidence interval; LFB, low-frequency behaviour; OR, odds ratio; PEDP, personal experience of dental pain.

The multiple logistic regression models showed some significant associations between students adopting HFB and individual parameters. Male students were significantly less likely to inform patients about postoperative pain [odds ratio (OR) = 0.33; 95% confidence interval: 0.14–0.80]. The year of study variable showed significant association with HFB related to the intra-operative and postoperative management of pain. Indeed, students in years 4 and 5 asked patients significantly more frequently about the efficacy of anaesthesia and about pain during procedures than did students in year 6 (P < 0.05). Students in year 5 were significantly more likely to warn patients more often about postoperative pain than were students in year 6 (OR = 3.74; P = 0.023). Reporting a PEDP was significantly associated with asking about dental anxiety (OR = 2.40; P = 0.009). Finally, we found no significant association between students being dentally anxious and adopting HFB when managing patients’ pain and patients’ anxiety (Table 3).

Discussion

The present study first aimed to examine how dental students control two essential and interdependent characteristics – pain and anxiety – of patients consulting for emergency care. Control of these elements was investigated from two perspectives: assessment and management. The global response rate achieved (78.6%) was in the expected range in comparison with the rate reported in other studies involving dental students21., 22., 23..

Concerning assessment, the very high rate of students ‘often’ to ‘always’ asking patients about existing pain prior to treatment (96.8%) highlights the fact that a large majority of students might consider pain as a major dimension of emergency dental care. Whereas a previous publication suggested that dental students should be encouraged to ask patients directly about dental anxiety14, our findings indicated that this was rarely carried out by the students of the dental school of Marseille: one-third (33.6%) ‘often’ to ‘always’ asked patients about anxiety before treatment, but only 9% did so systematically. However, effective evaluation of patients’ anxiety prior to treatment may strongly affect the management of anxious patients16., 24.. The earlier the anxiety is diagnosed, the more the treatment is likely to succeed16. Indeed, a diagnosis of anxiety allows the practitioner to adopt a patient-centred care approach and to prevent actions that may have adverse effects on a patient's anxiety24.

These findings raised questions not only about the students’ awareness of anxiety related to emergency situations but also about the means they possibly used to assess it. Considering that the students involved in our investigation did not use anxiety evaluation scales, we postulate that they may either not evaluate anxiety at all or may use unreliable methods, such as subjective evaluation based on observation of patients’ behaviour14.

Once identified, anxiety and pain need to be managed. Concerning anxiety, psychological measures should primarily be used because pharmacological control is incompatible with the limited time of emergency care. Intra-operative behavioural management strategies, such as ‘reassuring words’ or ‘providing control’, were systematically implemented by 58.3% and 78%, respectively, of the sample. These percentages are higher than those presented in a previous study in which 40% of the students interviewed declared giving reassurance to the patient during treatment and only 8% declared offering the patient some control over the procedure13.

Concerning pain, the present study showed that pre-, intra- and postoperative pain were not considered equally by the students. Whereas a large majority of the students always sought pain information from the patient prior to treatment, intra-operative pain received less frequent attention and less than half of the students always considered occurrence and control of postoperative pain. However, according to patients, dentists’ explicit dedication to pain prevention has been defined as the most important practitioner behaviour to reduce anxiety12. These results highlighted the need to improve students’ behaviour regarding management of pain during, but also after, dental procedures. Indeed, unexpected pain may be highly anxiety-provoking and perceived as resulting from dentists’ intervention more than the initial dental issue. Systematic and continuous control of pain is crucial because patients’ memory for acute pain is reconstructed and emphasised over time, particularly in anxious patients25.

A second aim of the study was to determine if individual parameters, such as gender, personal dental anxiety, PEDP or year of study, could affect the students’ attitudes towards patients’ pain and anxiety. Gender did not appear as a determinant factor in the students’ behaviour overall. It showed significant association with one HFB out of five, as male students were significantly less likely than female students to inform patients about postoperative pain.

Previous publications have discussed the possible influence of students’ personal dental anxiety on their relationships with patients, speculating that it could either have adverse effects on the quality of treatment or promote a more caring relationship with patients26., 27.. Slightly more than one-quarter (27.3%) of students in the present study showed moderate to high dental anxiety and we found no evidence that being dentally anxious could significantly impact their attitudes towards patients’ pain and anxiety. On the other hand, reporting PEDP (51.3%) led to a more frequent search for patients’ anxiety prior to treatment but was not significantly associated with higher frequencies of intra-operative and postoperative pain and anxiety management. These results are relevant to previous studies on empathy, which concluded that a personal experience of pain is not required to perceive and understand the pain of others28., 29..

Finally, our study demonstrated that more clinical experience could be associated with less systematic consideration for intra-operative pain. Indeed, students in year 6 significantly less frequently asked patients about the efficacy of anaesthesia and about pain caused by dental procedures than students in years 4 and 5. In the actual curriculum provided at the University of Marseille, pain is addressed through theoretical courses in years 4 and 5, but not in year 6. We postulate that students could feel more involved in patients’ pain when having been taught more recently on this topic, highlighting a potential need for complementary clinical education. Another and non-exclusive explanation for this significant difference in attitudes towards intra-operative pain could be higher self-confidence of year 6 students in their technical skills because this has been shown to increase with clinical experience30.

Within the limitations of the present study related to French dental students, our investigation highlighted that the students’ attitudes regarding pain and anxiety of patients consulting for emergency dental care would need to be improved, especially in the assessment of anxiety and the establishment of continuity in the management of pain at each step of the treatment. These results are in line with previous conclusions related to educational needs regarding pain and anxiety management20., 31., 32..

Promoting a patient-centred care approach, which includes control of pain and anxiety, should constitute an ethical and educational part of the dental students’ curriculum10. It may enhance the immediate quality of care for patients not only in public hospitals but also those in private dental offices by improving the behaviour of future dentists. Moreover, it may benefit the students themselves because the way they learn to cope with anxious patients during training may influence their future practice and their own perceived stress13., 20.. A study on orofacial pain diagnosis concluded that dental students were in demand for more clinical education related to specific topics such as pain32. We suggest that emergency situations would be a very suitable field for in-situation learning and contextualisation of theoretical knowledge around the themes of anxiety and pain management. As several teachers may be involved in this transversal educational field, harmonisation between the teachers’ lectures in preclinical and clinical education is recommended to standardise the training of the students. Finally, it should be emphasized that greater educational needs may actually exist because this work relies on students’ self-reported attitudes. In-situation observational surveys of students’ behaviour, also considering patients’ perception, should be developed in further studies to confirm our findings and provide more accurate information on these issues.

Conclusions

This study provided a descriptive analysis of dental students’ attitudes towards patients’ pain and patients’ anxiety in a dental emergency setting. It raised educational issues by highlighting the need for improvement of these topics in the dental curriculum in order to enhance both the behaviour of future dentists and patient care. Clinical education should allow contextualisation of the theoretical knowledge and we suggest that emergency dental care would be the perfect field in which to enhance students’ learning on pain and anxiety. To that end, continuity between preclinical and clinical education should remain a main concern.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Professor Gérard Levy for his valuable contribution to this manuscript and Mrs Nicky Maya for the English revision. They would also like to thank the students who participated in this study. This study was not supported by any funding.

Competing interests

The authors deny any conflict of interest.

Ethics statement

The investigation conformed to the provisions of the Declaration of Helsinki and the agreement of the Ethics Committee of Aix-Marseille University was obtained prior to starting. Each participant received a written explanation of the terms of the study prior to participation. It specified that answering the questionnaire would involve no specific knowledge but personal experience and that voluntary completion of the questionnaire was considered as informed consent to participate in the study.

References

- 1.Kanegane K, Penha SS, Munhoz CD, et al. Dental anxiety and salivary cortisol levels before urgent dental care. J Oral Sci. 2009;51:515–520. doi: 10.2334/josnusd.51.515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Leigh H, Reiser M. Plenum Press; New York: 1980. The Patient: Biological, Psychological, and social Dimensions of Medical Practice. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kanegane K, Penha SS, Borsatti MA, et al. Dental anxiety in an emergency dental service. Rev Saude Publica. 2003;37:786–792. doi: 10.1590/s0034-89102003000600015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pau AKH, Croucher R, Marcenes W. Prevalence estimates and associated factors for dental pain: a review. Oral Health Prev Dent. 2003;1:209–220. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Litt MD. A model of pain and anxiety associated with acute stressors: distress in dental procedures. Behav Res Ther. 1996;34:459–476. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(96)00015-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Weiner AA, Sheehan DV. Etiology of dental anxiety: psychological trauma or CNS chemical imbalance? Gen Dent. 1990;38:39–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cohen SM, Fiske J, Newton JT. The impact of dental anxiety on daily living. Br Dent J. 2000;189:385–390. doi: 10.1038/sj.bdj.4800777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mehrstedt M, Tönnies S, Eisentraut I. Dental fears, health status, and quality of life. Anesth Prog. 2004;51:90–94. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Armfield JM, Stewart JF, Spencer AJ. The vicious cycle of dental fear: exploring the interplay between oral health, service utilization and dental fear. BMC Oral Health. 2007;7:1. doi: 10.1186/1472-6831-7-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Formicola AJ, Myers R, Hasler JF, et al. Evolution of dental school clinics as patient care delivery centers. J Dent Educ. 2008;72:110–127. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Humphris GM, Morrison T, Lindsay SJ. The Modified Dental Anxiety Scale: validation and United Kingdom norms. Community Dent Health. 1995;12:143–150. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Corah NL, O'Shea RM, Bissell GD, et al. The dentist-patient relationship: perceived dentist behaviors that reduce patient anxiety and increase satisfaction. J Am Dent Assoc. 1988;116:73–76. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.1988.0162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.O'Shea RM, Mendola P, Corah NL. Dental students’ treatment of anxious patients. Soc Sci Med. 1991;32:229–232. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(91)90064-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lodge J, Tripp G. Dental students’ perception of patient anxiety. N Z Dent J. 1993;89:50–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Desjardins PJ. Patient pain and anxiety: the medical and psychologic challenges facing oral and maxillofacial surgery. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2000;58:1–3. doi: 10.1053/joms.2000.17885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dailey Y-M, Humphris GM, Lennon MA. Reducing patients’ state anxiety in general dental practice: a randomized controlled trial. J Dent Res. 2002;81:319–322. doi: 10.1177/154405910208100506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.De Jongh A, Adair P, Meijerink-Anderson M. Clinical management of dental anxiety: what works for whom? Int Dent J. 2005;55:73–80. doi: 10.1111/j.1875-595x.2005.tb00037.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Armfield JM, Spencer AJ, Stewart JF. Dental fear in Australia: who's afraid of the dentist? Aust Dent J. 2006;51:78–85. doi: 10.1111/j.1834-7819.2006.tb00405.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Muglali M, Komerik N. Factors related to patients’ anxiety before and after oral surgery. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2008;66:870–877. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2007.06.662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Brahm C-O, Lundgren J, Carlsson SG, et al. Dentists’ skills with fearful patients: education and treatment. Eur J Oral Sci. 2013;121:283–291. doi: 10.1111/eos.12017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kaakko T, Milgrom P, Coldwell SE, et al. Dental fear among university students: implications for pharmacological research. Anesth Prog. 1998;45:62–67. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Al-Omari WM, Al-Omiri MK. Dental anxiety among university students and its correlation with their field of study. J Appl Oral Sci. 2009;17:199–203. doi: 10.1590/S1678-77572009000300013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sghaireen MG, Zwiri AMA, Alzoubi IA, et al. Anxiety due to dental treatment and procedures among university students and its correlation with their gender and field of study. Int J Dent. 2013;2013:647436. doi: 10.1155/2013/647436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Armfield JM, Heaton LJ. Management of fear and anxiety in the dental clinic: a review. Aust Dent J. 2013;58:390–407. doi: 10.1111/adj.12118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kent G. Memory of dental pain. Pain. 1985;21:187–194. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(85)90288-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Acharya S, Sangam DK. Dental anxiety and its relationship with self-perceived health locus of control among Indian dental students. Oral Health Prev Dent. 2010;8:9–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Storjord HP, Teodorsen MM, Bergdahl J, et al. Dental anxiety: a comparison of students of dentistry, biology, and psychology. J Multidiscip Healthc. 2014;7:413–418. doi: 10.2147/JMDH.S69178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Danziger N, Prkachin KM, Willer J-C. Is pain the price of empathy? The perception of others’ pain in patients with congenital insensitivity to pain. Brain J Neurol. 2006;129:2494–2507. doi: 10.1093/brain/awl155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Danziger N, Faillenot I, Peyron R. Can we share a pain we never felt? Neural correlates of empathy in patients with congenital insensitivity to pain. Neuron. 2009;61:203–212. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.11.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Al-Dajani M. Dental students’ perceptions of undergraduate clinical training in oral and maxillofacial surgery in an integrated curriculum in Saudi Arabia. J Educ Eval Health Prof. 2015;12:45. doi: 10.3352/jeehp.2015.12.45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ivanoff CS, Hottel TL. A four-tier problem-solving scaffold to teach pain management in dental school. J Dent Educ. 2013;77:723–731. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Teich ST, Alonso AA, Lang L, et al. Dental students’ learning experiences and preferences regarding orofacial pain: a cross-sectional study. J Dent Educ. 2015;79:1208–1214. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]