Abstract

Background: The aim of this study was to evaluate the suitability of a dichotomous index, based on a special interdental brushing tool, to detect initial pathological processes in interproximal areas. Furthermore, different techniques of interdental hygiene were compared. Methods: Participants (n = 108) were instructed to clean their teeth using the Bass technique and were randomly assigned to three groups according to the type of interdental cleaning used: group A, use of interdental brushes; group B, no interdental hygiene (the control group); and group C, use of dental floss. Approximal Plaque Index (API), Plaque Index (PI), modified Sulcus Bleeding Index (mSBI) and the Bleeding on Brushing Index (BOB) were measured at baseline, and after 2 (t1) and 4 (t2) weeks. Statistical analysis was performed using the Wilcoxon test and the Mann–Whitney U-test. Results: One-hundred and six participants completed the study. The BOB decreased significantly in all groups (P < 0.001) with the most pronounced reduction being recorded for group A (baseline: 49.3 ± 23.0%; 4 weeks: 5.1 ± 6.9%). Also, the mSBI (P < 0.001) decreased significantly in all groups during the study. The API appeared to be less affected by the oral hygiene than other indices. The highest correlation was observed between BOB and mSBI (r = 0.785, P < 0.001). Conclusion: The BOB is a valuable complement for the existing array of indices in preventive dentistry, and is able to detect potential pathological processes in interproximal spaces. Additionally, this study suggests that interdental hygiene with individually selected brushes is superior to flossing. Clinical relevance: With the BOB, gingival inflammation can be demonstrated to patients, which could increase compliance.

Key words: Dental hygiene, interproximal cleaning, interdental brushes, floss, index, preventive dentistry, bleeding on brushing

Introduction

In 1960, Russel stated that ‘the presence of oral debris is the most deleterious factor considered’ regarding periodontal diseases1. Likewise, more recent studies have also confirmed that dental plaque is the most important aetiological factor for the progression of periodontal diseases and development of dental caries2., 3., 4., 5., 6.. Although it is well known that proper oral hygiene can improve the status of the periodontium and reduce caries incidence, visible plaque on at least one tooth can be found in most patients7., 8., 9., 10.. Knowing that adherent bacteriological biofilms cause gingivitis as well as dental caries, which affect, in particular, the interproximal areas11., 12., preventive dentistry must focus on motivating patients to perform consistent interproximal hygiene in addition to conventional toothbrushing. A review from 2011 analysed studies that compared flossing plus toothbrushing versus toothbrushing alone13. Seven of the 12 studies demonstrated a statistically significant benefit regarding the reduction of gingivitis after 1 month, which was associated with flossing plus toothbrushing. A review from 2013 compared the efficiency of supplementing toothbrushing with either interdental brushing or flossing14. It was suggested that after 1 month, the use of interdental brushes, in combination with standard toothbrushing, could reduce the incidence of gingivitis more effectively than could flossing plus toothbrushing. In order to evaluate the relevance of different studies, the parameters examined have to be comparable. Greenstein stated in 1984: ‘The ideal parameter should be (i) objective and not susceptible to subjective interpretation, (ii) inexpensive, (iii) not time consuming and (iv) easily used by clinicians to ensure widespread application’15. Indices fulfill an important role in daily dental practice. They are used to identify high-risk patients and to monitor the patients’ oral disease and compliance over time.

Over the years, a variety of periodontal indices has been established. One of these indices, which uses bleeding as a criterion, is the Sulcus Bleeding Index (SBI), which was introduced in 1971 by Muehlemann & Son16. Dichotomous bleeding indices are used frequently because ‘gingival bleeding is an objective, easily assessed sign of inflammation that is associated with several periodontal diseases’17.

One of the most common indices is the Bleeding on Probing Index (BOP), which aims to assess subgingival bleeding associated with use of a periodontal probe18. As penetration of the probe tip into healthy tissues is believed to stop within the avascular junctional epithelium, no bleeding should be induced when appropriate force is used15., 19., 20.. This index was not considered in the present study as it is only used in patients with periodontitis to assess the depth of the pockets.

One advantage of dichotomous bleeding indices is a high negative predictive value associated with sites that do not show progression of periodontitis. On the other hand, the positive predictive value is extremely low21. The reason for this might be that gingivitis does not necessarily progress to chronic periodontitis, which leads to the proposal that bleeding indices work best as indicators for gingivitis or pockets at risk for active periodontal disease17., 18., 22..

Additionally, there are further limitations of the existing bleeding indices. How the probe is handled differs between clinicians regarding the angle used and the probing pressure, resulting in inconsistency in the reproducibility of measurements23.

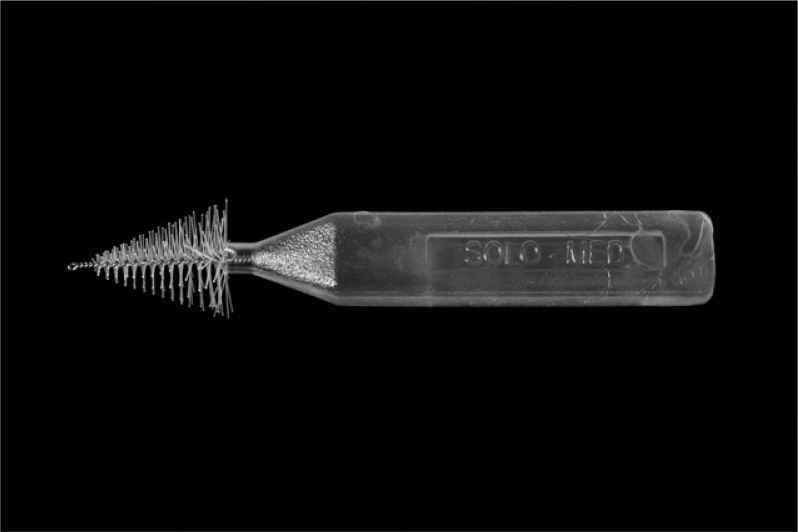

Furthermore, most of the indices commonly used fail to represent the interproximal conditions precisely, as those areas are generally not accessible using standard diagnostic tools6. As interdental sites usually seem to be strongly affected by gingivitis and periodontitis-associated bone loss12., 24., 25., an alternative that overcomes this problem would be beneficial. For assessment of the Eastman Interdental Bleeding Index (EIBI), a wooden stick is inserted horizontally into the interdental area26. Although this index has been shown to produce reliable results27, concerns regarding trauma to the papillae are justified. For this reason, Hofer et al.28 used interdental brushes instead of wooden sticks for the assessment of interdental gingivitis, revealing a highly significant correlation with the EIBI. In order to minimise gingival trauma, conical interdental brushes (e.g. the BOB-probe®; Figure 1) are used to determine the new Bleeding on Brushing Index (BOB) in the present study. Furthermore, interdental areas of different sizes can be measured with just one diagnostic tool, namely the BOB-probe®. Another difference from Hofer's study is the increased number of subjects and indices compared, as well as the observation of changes induced by improved oral-hygiene regimes over a period of 4 weeks.

Figure 1.

The BOB-probe®. A diagnostic tool, with synthetic bristles and a central core of stainless steel, for measuring the Bleeding on Brushing Index (BOB).

The aim of the present clinical study was to introduce a simple and reliable screening method to detect initial pathological processes in interproximal spaces. Therefore, a specific conical interdental brush (the BOB-probe®) was used to establish and validate a dichotomous index (BOB). This index was compared with the widespread modified Sulcus Bleeding Index (mSBI) and also with common plaque indexes [the Approximal Plaque Index (API) and the Plaque Index (PI)]. The API is a dichotomous index, but it is very strict, which means that even patients with clearly improved oral hygiene could not reach significantly lower API values. Furthermore, the interdental situation is not described adequately. The PI includes different scores but is restricted to vestibular surfaces only.

In addition, the efficiency of interdental brushing and flossing to reduce interproximal bleeding were evaluated and compared. The subjects’ basic oral hygiene in all groups was performed with toothbrush and toothpaste using the Bass technique29.

Materials and methods

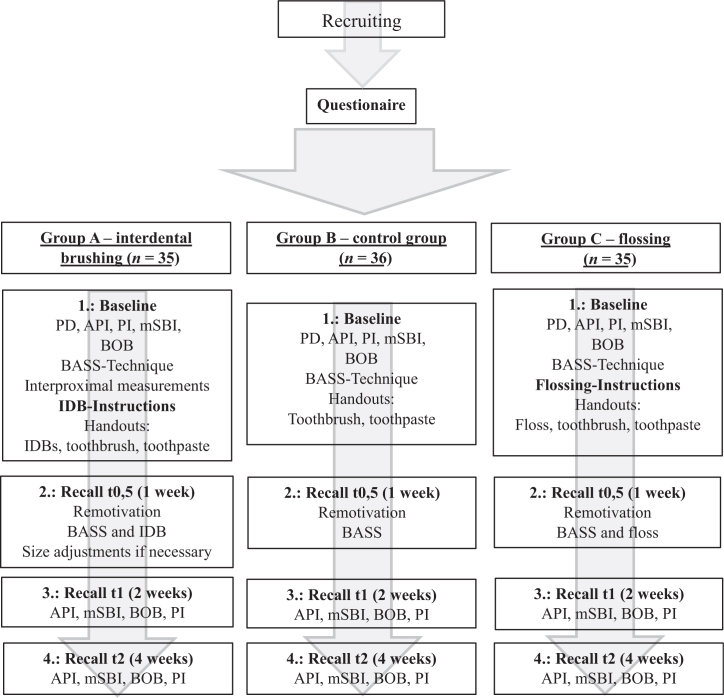

This single-centre, controlled, randomised study was conducted in a four-appointment parallel-group design (Figure 2) from 3 November 2014 to 13 April 2015. Two groups using different interproximal hygiene tools (group A: interproximal brushes – SOLO-STIX®; group C: floss – Elmex®) were compared with a control group (group B: no interproximal hygiene). Before the study was initiated, ethical approval was obtained by the Institutional Review Board of the Medical Faculty of the Technische Universität Dresden, Germany (EK 17012014). Volunteers were recruited via intranet of the Carl Gustav Carus University Clinic, bulletins and flyers in the period from 2 June 2014 to 19 December 2014. As a prerequisite, they provided their written consent to participate in the study.

Figure 2.

Study design. API, Approximal Plaque Index; BOB, Bleeding on Brushing Index; IDB, interdental brush; mSBI, modified Sulcus Bleeding Index; PI, Plaque Index; PD, probing depths.

The project was conducted in full accordance with the World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki.

Subjects

The participants were required to be of adult age (>18 years old), and to have a closed dental arch (without dental implants or fixed/removable partial dentures). Subjects were excluded from the clinical study if they had serious health conditions (e.g. diabetes mellitus, hepatitis, human immunodeficiency virus, malignancy, immune suppression, risk for endocarditis, alcohol or drug abuse) or a professional dental background (e.g. dental assistants, dentists), if they smoked, were pregnant, or regularly used antiepileptic drugs, calcium antagonist drugs or immune-suppressive drugs. Initially, good oral health with no signs of periodontal disease [Periodontal Screening Index (PSI) score of ≤2], caries or non-physiological salivary flow rate was assessed by oral examination by an experienced dentist. Initially, 157 subjects were screened, of whom 108 were eligible for inclusion in the study.

A sample size of 35 per group was calculated to have 80% power to detect a difference in a mean reduction of 0.5 on the PI scale between group A and group C. A variance estimate was taken from Christou et al.30 The participants were randomly assigned to the different groups. The allocation was performed by one of the examiners and by a dental assistant.

Parameters

Two dentists from the Clinic of Operative Dentistry performed the clinical examinations. Before the examinations these dentists had undergone a training procedure, with the aim of minimizing measurement error. The examiners assessed the indices to be compared in five ‘test subjects’ on consecutive days under the supervision of an experienced dentist.

The API31 was determined dichotomously in the first and third quadrants lingually and in the second and fourth quadrants buccally, at baseline, and after 2 and 4 weeks. As a preparatory part of the measurement, Mira-2-Ton-Solution was applied, and the supernatant was rinsed off with water.

Additionally, the PI32 (scored on a scale from 0 to 3), was measured at the buccal site of every tooth.

Furthermore, the mSBI33 was determined by moving a standardised periodontal probe within the sulcus towards the papilla from both sides, buccally in the first and third quadrants, and lingually in the second and fourth quadrants. After 10–30 seconds, the results were recorded dichotomously for every interproximal area.

Finally, the BOB was also measured dichotomously. For that purpose, a special conical interdental brush (BOB-probe®) was inserted buccally into the interproximal spaces with little force (~0.25 N) until slight resistance was sensed (Figure 1). After 10–30 seconds, bleeding in the interproximal areas was recorded.

Study protocol

Screening phase

All volunteers underwent a complete oral examination to confirm oral health and to ensure that the inclusion criteria were met. As part of the appointment, pocket depths (PD), PSI, mSBI, API, PI and BOB measurements were performed by the examiners. If the subject was eligible for inclusion in the study, further appointments were arranged.

Baseline examination (t0)

At baseline, PD, mSBI, API, PI and BOB measurements were performed again to determine the initial values. Additionally, interproximal spaces were measured in group A using a specific probe (BlueBee-Sonde®, made from semi-elastic plastic material) designed for measuring the size of interproximal spaces. Each mark on the probe represents two different sizes of interdental brush. Calibration procedures regarding the measurements were performed before the study to ensure accurate findings. Afterwards, all subjects were introduced to the Bass technique of toothbrushing. In addition, subjects in group A received instructions on how to use interdental brushes properly, and were told to use them once a day. Participants in group C were likewise trained on how to use floss correctly and daily. In group B no interdental hygiene was performed.

Finally, all subjects were given the same model of toothbrush (Oral-B® ClassicCare 35; Fa. Procter & Gamble GmbH, Schwalbach am Taunus, Germany) as well as the same toothpaste (Meridol® Zahnpasta; Fa. GABA GmbH, Hamburg, Germany). Group A was additionally provided with matching colour-coded interdental brushes (SOLO-STIX®; Fa. SOLO-MED GmbH, Trier, Germany) (Figure 3) based on the results of the BlueBee®-explorer, whereas group C received dental floss (Elmex® floss, unwaxed; Fa. GABA GmbH).

Figure 3.

SOLO-STIX®, Fa. SOLO-MED GmbH: 12 sizes of cylindrical interdental brushes used in the study (synthetic bristles, central core stainless steel).

First recall appointment (t0.5)

One week after the baseline examinations participants returned to the clinic to discuss possible problems and side effects. No clinical measurements were made. However, as some of the subjects showed slight shrinkage of their papillae, the interproximal spaces of patients in group A were remeasured and the size of the interdental brushes adjusted in order to ensure that the correct size of brush was being used. Furthermore, medication used in the interval between the baseline examination and the first recall appointment was documented for all subjects.

Second (t1) and third (t2) recall appointments

Participants underwent 2- and 4-week follow-up examinations. mSBI, API, PI and BOB measurements were taken again by the examiners. Additionally, responses to questions about possible problems and side effects, as well as on medication used between the different appointments, were recorded. Subsequently, a clinical examination was completed.

Statistics

Mean values and standard deviations were calculated for each variable using the participant as the observational unit. The dichotomous indices (API, mSBI and BOB) were calculated as a percentage (positive sites/present sites × 100), while PI was assessed as mean value (0–3). Between-group comparisons of mean API, mSBI, PI and BOB were performed using the Mann–Whitney U-test. Statistically significant differences within the groups were evaluated using the Wilcoxon test. It was decided to use non-parametric tests because of the right-skewed distribution, in particular for PI. Subsequently, Holm adjustments of significance for multiple comparisons were made (adjusted P was < 0.017). Furthermore, Pearson correlations were performed between the different groups. Statistical analysis was carried out using IBM SPSS Statistics 22; IBM Deutschland GmbH, Ehningen, Germany.

Results

Two subjects were excluded after randomisation: one for epilepsy (group A) and one for pregnancy (group C). Therefore, the data of 106 individuals (35 in group A, 36 in group B and 35 in group C; 57 women and 49 men), age range 19–50 (27.6 ± 6.3) years, were analysed. Compliance regarding oral hygiene was judged as adequate by the examiners.

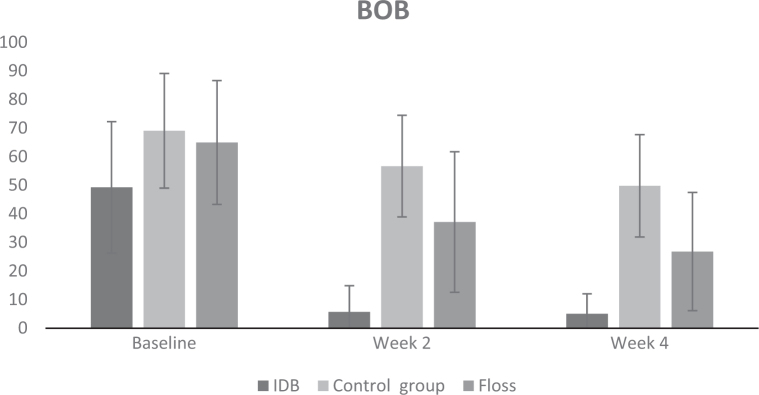

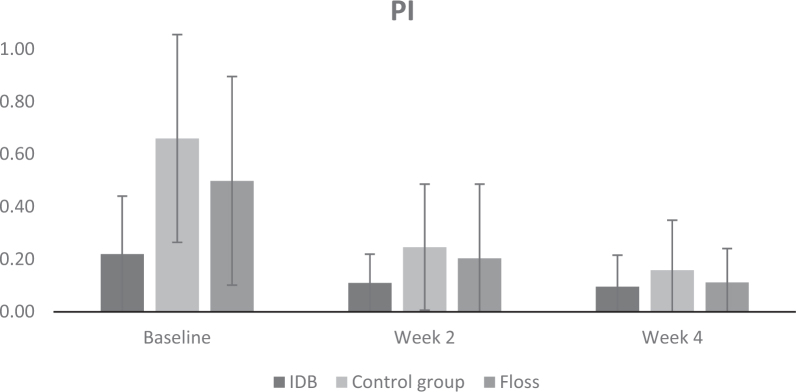

The clinically measured mean values for API, PI, mSBI and BOB at baseline (t0), and at 2-week (t1) and 4-week (t2) follow-up examinations, are presented in Figures 4–7 for all three groups; the results of the Wilcoxon test and the Mann–Whitney U-test are summarised in Tables 1 and 2.

Figure 4.

Approximal Plaque Index (API; in %) at baseline, and after 2 and 4 weeks, for group A [interdental brushes (IDB)], group B (control) and group C (floss). Bars represent mean; standard deviation is shown.

Figure 7.

Bleeding on Brushing Index (BOB; in %) at baseline, and after 2 and 4 weeks, for group A [interdental brushes (IDB)], group B (control) and group C (floss). Bars represent mean; standard deviation is shown.

Table 1.

Results of the Wilcoxon test within groups A–C

| Index | t0 | t0 versus tl | t0 versus t2 | tl versus t2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| API | ||||

| Group A | 73.5 | n.s. | n.s. | n.s. |

| Group B | 84.7 | n.s. | n.s. | n.s. |

| Group C | 86.1 | P < 0.001 | P < 0.001 | n.s. |

| PI | ||||

| Group A | 0.22 | n.s. | n.s. | n.s. |

| Group B | 0.66 | P < 0.001 | P < 0.001 | n.s. |

| Group C | 0.50 | P < 0.001 | P < 0.001 | n.s. |

| mSBI | ||||

| Group A | 26.3 | P < 0.001 | P < 0.001 | n.s. |

| Group B | 56.3 | n.s. | P < 0.001 | n.s. |

| Group C | 53.9 | P < 0.001 | P < 0.001 | n.s. |

| BOB | ||||

| Group A | 49.3 | P < 0.001 | P < 0.001 | n.s. |

| Group B | 69.1 | P < 0.001 | P < 0.001 | n.s. |

| Group C | 65.0 | P < 0.001 | P < 0.001 | P < 0.01 |

Group A adopted interdental brushes, group B served as the control group (no interdental hygiene) and group C used dental floss. t0, baseline; t1, 2 weeks; t2, 4 weeks. The indexes evaluated were the Approximal Plaque Index (API, %), the Plaque Index (PI, mean value), the modified Sulcus Bleeding Index (mSBI, %) and the Bleeding on Brushing Index (BOB, %). n.s., no significant difference.

Table 2.

Results of the pairwise comparison by the Mann–Whitney U-test for all indices and groups

| Index | A versus B | A versus C | B versus C |

|---|---|---|---|

| API | |||

| t0 | P < 0.001 | P < 0.001 | n.s. |

| tl | P < 0.001 | n.s. | n.s. |

| t2 | P < 0.001 | n.s. | n.s. |

| PI | |||

| t0 | P < 0.001 | P = 0.003 | n.s. |

| tl | n.s. | n.s. | n.s. |

| t2 | n.s. | n.s. | n.s. |

| mSBI | |||

| t0 | P < 0.001 | P < 0.001 | n.s. |

| tl | P < 0.001 | P < 0.001 | n.s. |

| t2 | P < 0.001 | n.s. | n.s. |

| BOB | |||

| t0 | P = 0.006 | P < 0.001 | n.s. |

| tl | P < 0.001 | P < 0.001 | n.s. |

| t2 | P < 0.001 | P < 0.001 | P < 0.001 |

Group A adopted interdental brushes, group B served as the control group (no interdental hygiene) and group C used dental floss. t0, baseline; t1, 2 weeks; t2, 4 weeks.The indexes evaluated were the Approximal Plaque Index (API, %), the Plaque Index (PI, mean value), the modified Sulcus Bleeding Index (mSBI, %) and the Bleeding on Brushing Index (BOB, %). n.s., no significant difference.

Approximal Plaque Index

The API appeared to be less affected by the oral hygiene measures than any of the other indices. However, the use of interproximal brushes (group A) led to a slight (non-significant) decrease of the API. In controls (group B), the mean API was not reduced conclusively, although these patients had been introduced to the Bass technique of toothbrushing. Upon supplementing the participants’ daily oral health-care routine with floss (group C), the mean API was reduced significantly (P < 0.001). All in all, no pronounced reduction of the API was observed.

Pairwise comparison between the groups using the Mann–Whitney U-test suggested a significant difference between groups A and B at 2 and 4 weeks of follow-up, in favour of group A (P < 0.001). Only initially did flossing yield a slight decrease of API values in comparison with the control group after 2 weeks (non-significant). Overall, no significant differences were detected between subjects who used interproximal brushes and those who flossed.

Plaque Index

Significant reduction of the PI was found in groups A and B over the course of the study (group B, P < 0.001; group C, P < 0.001) (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Plaque Index (PI) at baseline, and after 2 and 4 weeks, for group A [interdental brushes (IDB)], group B (control) and group C (floss). Bars represent mean; standard deviation is shown.

As a result of high variability, no significant differences were detected between the groups using the Mann–Whitney U-test.

Modified Sulcus Bleeding Index

The largest reduction in mSBI was found in group A (P < 0.001) (Figure 6). In comparison, a significant reduction of the mSBI was found in group B (the control group) only after 4 weeks (P < 0.001). Similarly to group A, subjects in group C showed a significant decrease in mSBI values after 2 and 4 weeks (P < 0.001).

Figure 6.

Modified Sulcus Bleeding Index (mSBI; in %) at baseline, and after 2 and 4 weeks, for group A [interdental brushes (IDB)], group B (control) and group C (floss). Bars represent mean; standard deviation is shown.

Based on the pairwise comparison using the Mann–Whitney U-test, significant differences were found between the interdental brushing group (group A) and the control group (group B), after both 2 and 4 weeks, in favour of group A (P < 0.001). The comparison of both interdental hygiene techniques in terms of reducing sulcus bleeding identified a significant advantage for interdental brushing after 2 weeks (P < 0.001). Interestingly, there was no significant difference when the results of the flossing group (group C) were compared with the results of the control group (group B).

Bleeding on Brushing Index

Implementation of the BOB was successful in the control group as well as in the experimental groups (Figure 7).

In line with the observations derived from the mSBI, subjects who used interproximal brushes (group A) were also able to reduce their BOB after both 2 and 4 weeks (P < 0.001).

Although the reduction of BOB was clearly less pronounced in groups B and C than in group A, the Wilcoxon test yielded significance at t1 and t2 for both groups (P < 0.001).

Compared with the other groups, those subjects who used interproximal brushes (group A) showed significantly better results after both 2 and 4 weeks (P < 0.001). The Mann–Whitney U-test also showed significant differences in favour of the flossing group (group C) compared with the control group (group B) (t2: P < 0.001).

Correlations

Pearson correlations between the different indices were calculated using measurements for all subjects at all visits. The weakest correlation, with a Pearson coefficient (r) of 0.448 (P < 0.001), was found between API and PI. Slightly higher correlations were observed for API and mSBI and BOB (r = 0.540, P < 0.001; r = 0.503, P < 0.001).

If the PI was compared to the BOB, the Pearson correlations revealed a coefficient of 0.498 (P < 0.001). The correlation of PI and mSBI was higher (r = 0.616, P < 0.001).

As expected, with a Pearson coefficient of r = 0.785 (P < 0.001), the strongest correlation was found between mSBI and BOB.

Discussion

The aim of the present study was to establish a new gingival inflammation index which would focus on interproximal areas and be of considerable practical relevance, but also to compare different techniques of interdental hygiene.

Dental caries, as well as gingivitis and periodontitis, are infectious diseases caused by adherent bacterial biofilms34. It is well known that effective prophylaxis can only be obtained by sustained control of this biofilm31. Deficiencies in oral hygiene can be detected based on the direct correlation of the biofilm present and light-pressure-associated bleeding caused by gingival inflammation16., 35.. Unfortunately, interdental areas prone to caries and periodontitis are poorly accessible by standard diagnostic tools6., 11., 25.. The BOB presents a solution to this problem, as it offers valuable information on potentially pathogenic processes in the interproximal area.

In contrast, the API must be viewed critically. Owing to its stringent grading, its capacity to capture pathological conditions is limited. Furthermore, in this study, the subjects’ improved interdental hygiene appeared to have no effect on the API values, which therefore limits the index as a suitable tool for patient motivation.

Similarly, the PI provides little benefit for patients with average to good oral hygiene. Although there were significant reductions in PI in all three study groups, this index is mainly helpful for patients with poor oral health who must improve their oral hygiene.

As expected, the mSBI showed a significant decrease in both test groups (group A, interdental brushing; group C, floss). Considerably less reduction was found in group B (control group). As the mSBI detects bleeding at the entrance, but not in the centre, of interdental spaces, its potential to assess interdental conditions is limited. Furthermore, trauma of the gingiva as a result of excessive force cannot be a confounder36.

According to the results obtained in this study, it can be concluded that the BOB is a valuable complement to and extension of the existing array of indices in preventive dentistry. Similarly to the mSBI, significantly less bleeding occurred in group A (interdental brushing) and group C (floss) compared with group B (control). The autonomy of this novel index could be confirmed by moderate correlations with common indices. The highest correlation was found with the mSBI, an index that assesses gingival inflammation in interproximal areas. As a result of its specific type of assessment and its potential to assess the central aspect of interdental spaces, the BOB can be considered as a new entity. Based on the direct correlation of existing biofilm and the prevalence of light-pressure-associated bleeding, the BOB might become a suitable index to measure, as well as to demonstrate gingival inflammation. As a result, the patients’ motivation regarding the performance of interdental hygiene could potentially be increased. Another advantage of the BOB is the utilisation of a dental-care product for home use as a diagnostic tool. Owing to its conical shape, the BOB-probe® (Figure 1) is suitable for assessing the BOB in most interproximal areas and can be considered much less traumatic than a periodontal probe. However, it has been shown to have some limits in evaluating narrow interproximal areas, especially between lower incisors. For this reason, the design of the BOB-probe® should be optimised.

The results of the present study show significant improvement for all indices (PI, mSBI, API and BOB) for both group A (interdental brushes) and group C (floss) at 2 and 4 weeks when compared with baseline values. Previous studies have suggested that interdental brushes are superior to flossing regarding the effect on plaque indices but not on bleeding indices30., 37., 38.. In contrast, Jackson et al.39 found ‘significantly less interdental plaque’ and ‘significantly less proportion of sites with interdental bleeding’ after use of interdental brushing when compared with flossing. The results of the present study confirm superiority of interdental brushes for the bleeding indices assessed. Significantly better results both at 2 and 4 weeks in favour of group A (interdental brushes) were obtained for mSBI and BOB. The reason for this might be that the plaque indices used fail to adequately assess the interdental conditions. It has also been stressed that ‘in young individuals in whom the papillae fill out the interdental spaces, dental floss is the only tool which can reach into this area’37. However, this statement cannot be supported by the present. After measuring the dimensions of the interproximal entrances using a specific probe (BlueBee-Sonde®), the interdental brushes of the correct size were used. Probably because of the availability of 10 different sizes, only a few problems regarding small interdental spaces were reported.

Clinically, some reduction in the size of the papillae was observed both in group A (interdental brushes) and group C (floss), which could be explained by reversal of the inflammation process accompanied by the subsequent detumescence of the gingiva39., 40.. Therefore, no evidence for traumatic alteration of the interproximal tissue caused by interdental brushes was suspected. However, as depicted in Figures 6 and 7 the mean values for mSBI and BOB in group C were similar after both 2 and 4 weeks but differed drastically in group A. Accordingly, it could be suggested that although the sizes of the interdental brushes were adjusted, trauma of the papillae had already occurred, leading to more pronounced resolution. Consequently, the BOB-probe® provoked less bleeding during assessment of BOB. This presumption is in contrast to the fact that the conical shape of the BOB-probe® should provoke inflammation-related bleeding, regardless of how far the gingiva was retracted. Therefore, another more likely explanation could be the greater efficiency of interdental plaque removal in group A, as almost no bleeding occurred while assessing the BOB. The difference from the mSBI values can be explained by the fact that the BOB is only assessed at the entrance, and not in the central areas, of interdental spaces.

Interestingly, some improvement in the indices was also noted for the subjects in group B (control group). It can be postulated that the mainly young participants performed oral hygiene more carefully, encouraged by their participation in the study and the instructions provided regarding the Bass technique. This emphasises the importance of proper oral hygiene using conventional toothbrushes.

Another important aspect, namely the compliance of the subjects, was noted. Psychological experiments have shown that ‘visual knowledge of progress and results is highly important for effective performance of a task’41. Transferring this assumption to the present study, the bleeding areas after the index assessment were shown to the subjects via a hand mirror. With basic information (bleeding = inflammation; no bleeding = healthy), the intent and outcome could be explained easily to the study participants. As a result, we noted exceptional compliance of subjects who were highly motivated by the reduction of bleeding after 2 weeks.

However, the study covered a period of only 4 weeks; therefore, there is a need to determine how interdental hygiene is executed and sustained over a longer period of time.

Conclusions and future directions

-

•

The BOB is a valuable complement to the existing array of indices in preventive dentistry. It is a new entity. The BOB is appropriate for different applications, namely prophylaxis, recall and assessment of caries risk.

-

•

The relevance of the API must be questioned.

-

•

Interdental hygiene with interdental brushes of sizes appropriate for each individual is superior to flossing.

-

•

The application of an adequate brushing technique reduces the amount of plaque in the oral cavity and thus reduces inflammation.

-

•

Future studies should investigate the sustainability of interdental hygiene with interdental brushes.

Acknowledgements

The study was supported by SOLO-MED GmbH, Trier, Germany.

Conflict of interest

The sponsor had no influence on either the evaluation of the data or the preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Russel AL, Ayers P. Periodontal disease and socioeconomic status in Birmingham, Alabama. Am J Public Health. 1960;50:206–214. doi: 10.2105/ajph.50.2.206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nishihara T, Koseki T. Microbial etiology of periodontitis. Periodontology. 2000;2004:14–26. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0757.2004.03671.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Socransky SS. Criteria for the infectious agents in dental caries and periodontal disease. J Clin Periodontol. 1979;6:16–21. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051x.1979.tb02114.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Marsh PD. Dental plaque as a biofilm and a microbial community – implications for health and disease. BMC Oral Health. 2006;6:S14. doi: 10.1186/1472-6831-6-S1-S14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Periasamy S, Kolenbrander PE. Mutualistic biofilm communities develop with porphyromonas gingivalis and initial, early, and late colonizers of enamel. J Bacteriol. 2009;191:6804–6811. doi: 10.1128/JB.01006-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Selwitz RH, Ismail AI, Pitts NB. Dental caries. Lancet. 2007;369:51–59. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60031-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Axelsson P, Lindhe J. Effect of controlled oral hygiene procedures on caries and periodontal disease in adults. J Clin Periodontol. 1978;5:133–151. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051x.1978.tb01914.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Axelsson P, Nyström B, Linde J. The long-term effect of plaque control program on tooth mortality, caries and periodontal disease in adults. J Clin Periodontol. 2004;31:749–757. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051X.2004.00563.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chapple ILC, Van der Weijden F, Doerfer C, et al. Primary prevention of periodontitis: managing gingivitis. J Clin Periodontol. 2015;42:71–76. doi: 10.1111/jcpe.12366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Morris AJ, Steele J, White DA. The oral cleanliness and periodontal health of UK adults in 1998. Br Dent J. 2001;191:186–192. doi: 10.1038/sj.bdj.4801135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Demirci M, Tuncer S, Yuceokur AA. Prevalence of caries on individual tooth surfaces and its distribution by age and gender in university clinic patients. Eur J Dent. 2010;4:270–279. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mandel ID. Dental plaque: nature, formation and effects. J Periodontol. 1966;37:357–367. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sambunjak D, Nickerson JW, Poklepovic T, et al. Flossing for the management of periodontal diseases and dental caries in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;12:CD008829. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD008829.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Poklepovic T, Worthington HV, Johnson TM, et al. Interdental brushing for the prevention and control of periodontal diseases and dental caries in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;12:CD009857. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD009857.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Greenstein G. The role of bleeding upon probing in the diagnosis of periodontal disease. A literature review. J Periodontol. 1984;55:684–688. doi: 10.1902/jop.1984.55.12.684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mühlemann HR, Son S. Gingival sulcus bleeding – a leading symptom in initial gingivitis. Helv Odontol Acta. 1971;15:107–113. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Newbrun E. Indices to measure gingival bleeding. J Periodontol. 1996;67:555–561. doi: 10.1902/jop.1996.67.6.555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ainamo J, Bay I. Problems and proposals for recording gingivitis and plaque. Int Dent J. 1975;25:229–235. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hancock EB, Wirthlin MR. The location of the periodontal probe tip in health and disease. J Periodontol. 1981;52:124–129. doi: 10.1902/jop.1981.52.3.124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Caton J, Greenstein G, Polson AM. Depth of periodontal probe penetration related to clinical and histological signs of gingival inflammation. J Periodontol. 1981;52:626–629. doi: 10.1902/jop.1981.52.10.626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lang NP, Adler R, Joss A, et al. Absence of bleeding on probing (An indicator of periodontal stability) J Clin Periodontol. 1990;17:714–721. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051x.1990.tb01059.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Löe H, Anerud A, Boysen H, et al. Natural history of periodontal disease in man. Rapid, moderate and no loss of attachment in Sri Lankan laborers 14 to 46 years of age. J Clin Periodontol. 1986;13:431–440. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051x.1986.tb01487.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Van der Weijden GA, Timmerman MF, Saxton CA, et al. Intra-/inter-examinar reproducibility study of gingival bleeding. J Periodont Res. 1994;29:236–241. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0765.1994.tb01217.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mühlemann HR, Mazor ZS. Gingivitis in Zürich school children. Helv Odontol Acta. 1958;2:3–12. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schei O, Waerhaug J, Lovdal A, et al. Alveolar bone loss as related to oral hygiene and age. J Periodontol. 1959;30:7–16. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Caton JG, Polson AM. The Interdental Bleeding Index a simplified procedure for monitoring gingival health. Compend Contin Educ Dent. 1985;6:88–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Barendregt DS, Timmerman MF, Van der Velden U, et al. Comparison of the bleeding on marginal probing index and the Eastman interdental bleeding index as indicators of gingivitis. J Clin Periodontol. 2002;29:195–200. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-051x.2002.290302.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hofer D, Sahrmann P, Attin T, et al. Comparison of marginal bleeding using a periodontal probe or an interdental brush as indicators of gingivitis. Int J Dent Hyg. 2011;9:211–215. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-5037.2010.00483.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gibson JA, Wade AB. Plaque removal by the Bass and Roll brushing techniques. J Periodontol. 1977;48:456–459. doi: 10.1902/jop.1977.48.8.456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Christou V, Timmerman MF, Van der Velden U, et al. Comparison of different approaches of interdental oral hygiene interdental brushes versus dental floss. J Periodontol. 1998;69:759–764. doi: 10.1902/jop.1998.69.7.759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lange DE, Plagmann HC, Eenboom A, et al. Clinical methods for the objective evaluation of oral hygiene. Dtsch Zahnärztl Z. 1977;32:44–47. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Silness J, Löe H. Periodontal disease in pregnancy II. Correlation between oral hygiene and periodontal condition. Acta Odontol Scand. 1964;22:121–135. doi: 10.3109/00016356408993968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mombelli A, van Oosten MAC, Schürch E, Jr, et al. The microbiota associated with successful or failing osseointegrated titanium implants. Oral Microbiol Immunol. 1987;2:145–151. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-302x.1987.tb00298.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wade WG. The oral microbiome in health and disease. Pharmacol Res. 2013;69:137–143. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2012.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Löe H, Theilade E, Jensen SB. Experimental gingivitis in man. J Periodontol. 1965;36:177–187. doi: 10.1902/jop.1965.36.3.177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Listgarten MA. Periodontal probing: what does it mean? J Clin Periodontol. 1980;7:165–176. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051x.1980.tb01960.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Slot DE, Dörfer CE, Van der Weijden GA. The efficancy of interdental brushes on plaque and parameters of periodontal inflammation a systematic review. Int J Dent Hyg. 2008;6:253–264. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-5037.2008.00330.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gjermo P, Flötra L. The effect of different methods of interdental cleaning. J Periodontal Res. 1970;5:230–236. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0765.1970.tb00722.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jackson MA, Kellett M, Worthington H, et al. Comparison of interdental cleaning methods a randomized controlled trial. J Periodontol. 2006;77:1421–1429. doi: 10.1902/jop.2006.050360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cercek JF, Kiger RD, Garrett S, et al. Relative effects of plaque control and instrumentation on the clinical parameters of human periodontal disease. J Clin Periodontol. 1983;10:46–56. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051x.1983.tb01266.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chase L. Motivation of young children: an experimental study of the influence of certain types of external incentives upon the performance of a task. Univ Iowa Stud Child Welfare. 1932;5:111. [Google Scholar]