Abstract

Background: Oral diseases affect most of the global population. The aim of this paper was to provide a contemporary analysis of ‘human resources for oral health’ (HROH) by examining the size and distribution of the dental workforce according to World Health Organization (WHO) region and in the most populous countries. Method: Publically available data on HROH and population size were sourced from the WHO, Central Intelligence Agency, United Nations, World Bank and the UK registration body. Population-to-dentist and dental-workforce ratios were calculated according to WHO region and for the 25 most populous countries globally. Workforce trends over time were examined for one high-income country, the UK. Results: The majority of the world’s 1.6 million dentists are based in Europe and the Americas, such that 69% of the world’s dentists serve 27% of the global population. Africa has only 1% of the global workforce and thus there are marked inequalities in access to dental personnel, as demonstrated by population to dental-workforce ratios. Gaps exist in dental-workforce data, most notably relating to mid-level clinical providers, such as dental hygienists and therapists, and HROH data are not regularly updated. Workforce expansion and migration may result in rapid changes in dentist numbers. Conclusion: Marked inequalities in the distribution of global HROH exist between regions and countries, with inequalities most apparent in areas of high population growth. Detailed contemporary data on all groups of HROH are required to inform global workforce reform in support of addressing population oral health needs.

Key words: Dental, population, workforce, human resources, global, inequalities, access, oral health

Introduction

Dentistry is the professional clinical discipline concerned with the prevention, detection, management and treatment of oral and dental diseases and their sequelae. The World Dental Federation (FDI) has instituted a ‘call for global action’ on meeting the challenge of oral disease1. Formally recognised as part of the chronic non-communicable disease burden by the United Nations (UN)2, and confirmed by the papers on the Global Burden of Disease3., 4., 5., 6., untreated dental caries in permanent teeth was the most prevalent oral condition of the 291 included in the 2010 analysis4. The major oral disorders (dental caries, periodontal diseases) and the outcome of their management (total tooth loss) are amongst the top 35 causes of years lived with a disability globally and together they are calculated to cause 15 million years of life lived with a disability (YLLD)4. Much disease should, where possible, be prevented; however, dental caries and periodontal diseases are progressive. Oral diseases must be treated, and the risk of future disease managed, in an evidence-based preventative manner5., 6.. The importance of having sufficient human resources for health was clearly recognised on the global landscape with the publication, in 2016, of the Global Strategy for Human Resources for Health, 20307., 8.. Within dentistry, the dental workforce, which may be equivalently termed ‘human resources for oral health’ (HROH), has not yet received the attention merited given the prevalence of oral diseases. This paper provides an introduction to some of the relevant issues.

Dental professionals serve the oral health needs and demands of patients across the life course and therefore any consideration of HROH must relate to the size and health of the population9. Population growth and longevity provide additional challenges10 and thus it is important to monitor the dental workforce globally in order to inform future planning within, and between, countries5., 8., 11.. The importance of good relationships between national and global dental associations has been emphasised12 in relation to workforce issues; and there is vigorous debate on the role of mid-level providers in delivering the necessary skill-mix for future dental care, particularly in relation to bringing care to areas and population groups that are under-served by dentists13. Meeting global health goals14., 15. and facilitating access to care includes an emphasis on country-specific action8. This paper aims to initiate debate by profiling the global dental workforce. The following research questions are addressed:

-

•

What is the size and distribution of the dental workforce according to region?

-

•

What is the variation in population-to-dentist ratio according to World Health Organization (WHO) region?

-

•

What is the variation in population to dental-workforce ratios in the world’s most populous countries?

-

•

How may workforce to population ratios change over time?

The aim of this paper is thus to provide a contemporary analysis of the global dental workforce (HROH), examining the size and distribution of the dental workforce (including variation in population to dental-workforce ratios) according to WHO region and, for the world’s 25 most populous countries, consider how the situation is changing and make recommendations for action.

Methods

Publicly available information on the dental workforce and populations, according to country, were sourced via the Internet. Dental workforce data from 191 countries out of the 193 UN member states were obtained from the WHO database16. Information on dental-workforce capacity, namely mid-level providers (dental hygienists and therapists), and oral health data were obtained from the Country Area Profile Project (CAPP)17. Population demographic data were obtained from the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) World Factbook18 and the WHO19, and projections of population growth were obtained from the UN Department of Economics and Social Affairs10. Country-specific data on wealth were obtained from the World Bank20. Using this information, the population-to-dentist ratio was calculated for each WHO region and the most populous countries globally. This is considered, together with available evidence on dental caries experience in 12-year-old children [decayed, missing and filled teeth (DMFT)]. Dental workforce data for the UK were obtained from the regulatory body for dental professionals, the General Dental Council (GDC)21., 22., 23., and population data were obtained from the Office of National Statistics24, to examine change in one populous high-income country over time.

Results

Available data from the FDI and the WHO suggest that there are at least 1.6 million dentists globally, unevenly distributed across the six WHO regions (Table 1). The Americas, followed by Europe, have the most dentists, hosting at least two-thirds of the profession (69%) in these two regions alone, whilst having only 26% of the population. In contrast, Africa has only 1% of the global workforce of dentists. Inequalities are even more apparent when considering population-to-dentist ratios, which range from approximately 1,400:1 in the Americas to over 40,000:1 in Africa.

Table 1.

Total number of dentists according to World Health Organization (WHO) region and globally

| Region | Total no. of dentists* | Population† | Population per dentist |

|---|---|---|---|

| The Americas | 671,189 | 966,494,931 | 1,440 |

| Europe | 450,555 | 906,995,748 | 2,013 |

| Western Pacific | 238,595 | 1,857,588,459 | 7,786 |

| South East Asia | 122,545 | 1,855,067,718 | 15,138 |

| Eastern Mediterranean | 110,545 | 612,580,128 | 5,541 |

| Africa | 22,110 | 927,370,720 | 41,943 |

| Global | 1,615,539 | 7,126,097,704 | 4,411 |

Intraregional disparities also exist. For example, within South East Asia, South Korea has a population-to-dentist ratio of 2,043:1, whereas in Nepal it is considerably higher, at 122,003:1. Within countries, variation in population-to-dentist ratio between urban and rural areas is most dramatic within low-income countries, which have fewer dentists overall. For example, whilst 65.7% of the population lives in rural settings in The Democratic Republic of Congo, 79% of dentists are located in urban areas.

The 25 largest countries in the world, hosting 5.25 billion of the world’s population, vary greatly in their dental need, as represented by mean levels of dental caries experience (DMFT of 12-year-old children) and dental-workforce capacity (Table 2). Inequalities in workforce provision between developed and developing countries may, however, appear even starker when examining the population per clinical dental professional, rather than merely per dentist. The data in Table 2 suggest that some countries with already high numbers of dentists may also have high numbers of mid-level providers. For example, Japan has nearly 95,000 dentists and over 73,000 dental hygienists, making a population-to-dental-workforce ratio of 1,342:1. Interestingly, South Korea has the highest reported levels of need in a populous country, with an average of 3.1 DMFT in 12-year-old children; it has a population-to-dentist ratio of 2,043:1, which is decreased to 1,297:1 when dental hygienists are included. In contrast, Ethiopia has a population-to-dentist ratio of 1.5 million:1, which is decreased only to 1 million:1 when other clinical dental personnel are included; thus, the majority of the dental caries experience in 12-year-old children is likely to be untreated. Ethiopia therefore provided an example of the extreme workforce capacity challenges that exist in parts of the African region. Moreover, out of the 25 largest countries in the world, the three with the highest population-to-dentist ratio are in the African region (Ethiopia, Democratic Republic of the Congo and Nigeria), despite having survey data showing oral disease in their 12-year-old children, albeit not be as high as in some other countries.

Table 2.

Dental professionals and dental diseases in the 25 largest countries by population

| Order of country (according to population size) | Country | Total population* | % Urban population† | Average DMFT in 12-year-old children‡ | Number of dentists§ | Date | Number of hygienists¶ (including dental therapists) | Date | Number of therapists¶ | Date | Population per dentist | Population per clinical dental provider |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | China | 1,343,239,923 | 47 | 0.5 | 51,012 | 2005 | 1995 | 16,643 | 1995 | 26,332 | 19,854 | |

| 2 | India | 1,205,073,612 | 30 | 1.3 | 93,332 | 2008 | 12,912 | 12,912 | ||||

| 3 | USA | 313,847,465 | 82 | 1.2 | 134,245 | 2000 | 112,000 | 2000 | 2,338 | 1,275 | ||

| 4 | Indonesia | 248,645,008 | 44 | 0.9 | 32,189 | 2010 | 2004 | 4,636 (inc. DH) | 2004 | 7,725 | 6,752 | |

| 5 | Brazil | 199,321,413 | 87 | 2.8 | 227,141 | 2008 | 390 | 2004 | 878 | 876 | ||

| 6 | Pakistan | 190,291,129 | 36 | 1.38 | 9,822 | 2009 | 350 | 2003 | 19,374 | 18,707 | ||

| 7 | Nigeria | 170,123,740 | 50 | 0.5 | 2,571 | 2008 | 400 | 2004 | 1,100 | 2004 | 66,170 | 41,789 |

| 8 | Bangladesh | 161,083,804 | 28 | 1 | 2,742 | 2007 | 58,747 | 58,747 | ||||

| 9 | Russian Federation | 142,517,670 | 73 | 2.9 | 45,628 | 2006 | 3,123 | 3,123 | ||||

| 10 | Japan | 127,368,088 | 67 | 1.7 | 94,882 | 2006 | 73,297 | 2004 | 1,342 | 1,342 | ||

| 11 | Mexico | 114,975,406 | 78 | 2 | 148,456 | 2004 | 5,000 | 2001 | 774 | 749 | ||

| 12 | Philippines | 103,775,002 | 49 | 2.9 | 45,903 | 2004 | 800 | 2000 | 2,261 | 2,222 | ||

| 13 | Viet Nam | 91,519,289 | 30 | 1.9 | 1,500** | (2002–9) | 800 | 2000 | 6,099 | 5,791 | ||

| 14 | Ethiopia | 91,195,675 | 17 | 1.55 | 60 | 2003 | 32 | 2000 | 1,519,928 | 991,257 | ||

| 15 | Egypt | 83,688,164 | 43 | 0.4 | 33,476 | 2009 | 2,500 | 2,500 | ||||

| 16 | Germany | 81,305,856 | 74 | 0.7 | 64,287 | 2009 | 350 | 2008 | 1,265 | 1,258 | ||

| 17 | Turkey | 79,749,461 | 70 | 1.9 | 20,589 | 2009 | 3,873 | 3,873 | ||||

| 18 | Iran | 78,868,711 | 71 | 1.9 | 13,210 | 2005 | 650 | 2004 | 5,970 | 5,690 | ||

| 19 | Democratic Republic of the Congo | 73,599,190 | 35 | 0.4-1.1 | 159 | 2004 | 462,888 | 462,888 | ||||

| 20 | Thailand | 67,091,089 | 34 | 1.9 | 4,129 | 2004 | 58 | 2004 | 3,307 | 2004 | 16,249 | 8,953 |

| 21 | France | 65,630,692 | 85 | 1.2 | 41,876 | 2010 | 0 | 2008 | 0 | 2008 | 1,567 | 1,567 |

| 22 | UK | 63,047,162 | 80 | 0.7 | 32,189 | 2010 | 5,340 | 2008 | 1,154 | 2008 | 1,959 | 1,630 |

| 23 | Italy | 61,261,254 | 68 | 1.1 | 31,085 | 2009 | 4,000 | 2007 | 1,971 | 1,746 | ||

| 24 | South Africa | 48,810,427 | 62 | 1.1 | 5,988 | 2004 | 955 | 2006 | 443 | 2006 | 8,151 | 6,609 |

| 25 | Republic of Korea | 48,860,500 | 83 | 3.1 | 23,912 | 2008 | 13,769 | 2000 | 2,043 | 1,297 |

Reference 18.

UN Department of Economics and Social Affairs, http://esa.un.org/unpd/wpp/Sorting-Tables/tab-sorting_population.htm, accessed 14th July 2012.

WHO Oral Health Database, http://www.mah.se/CAPP/Country-Oral-Health-Profiles/According-to-Alphabetical/Global-DMFT-for-12-year-olds-2011/, accessed 08th November 2012.

Reference 16.

Malmö University Oral Health Database, Country/Area Profile Project, http://www.mah.se/CAPP/, accessed 08th November 2012.

FDI Oral Health Atlas, http://www.fdiworldental.org/oral-health-atlas, accessed 08th November 2012.DH, dental hygienists; DMFT, decayed, missing and filled teeth.

The available information on dentists largely spans a period of 20 years from 1990 to 2010, with six countries having data prior to 1998. Many of the latter are small countries (e.g. Monaco and San Marino) and therefore are unlikely to have a major effect on the global calculations. Data on dentists from many of the low-income countries were not as up-to-date as those from high-income countries, and data on dental care professionals are almost non-existent. Although only a limited number of countries report data on dental hygienists and therapists, lack of evidence of mid-level providers may not mean that they do not exist.

Country-specific data highlight that the nature of the dental workforce may change quickly, and significantly, in a short timescale. For example, in the UK, between 2007 and 2014, the population increased by 5.1%, whilst the population of registered dentists increased by 15.8%, therefore significantly improving the population-to-dentist ratio in a 7-year time span (Table 3).

Table 3.

UK population and numbers of dentists registered with the General Dental Council from 2007 to 2014

| Variable | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| UK population* | 60.98M | 61.4M | 61.8M | 62.3M | 63.2M | 63.3M | 63.7M | 64.1M |

| Number of dentists† | 35,419 | 36,281 | 37,049 | 38,379 | 39,307 | 39,894 | 40,423 | 41,007 |

| Population per dentist | 1,722:1 | 1,692:1 | 1,668:1 | 1,622:1 | 1,607:1 | 1,587:1 | 1,576:1 | 1,256:1 |

Office for National Statistics. Population Estimates for UK, England and Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland, Population Estimates Timeseries 1971 to Current Year 2014 [Available from: http://www.ons.gov.uk/ons/rel/pop-estimate/population-estimates-for-uk-england-and-wales-scotland-and-northern-ireland/2013/sty-population-changes.html 09.03.2015].

General Dental Council. GDC Regulation Statistical Reports: Annual Reports and Accounts, 2011; 2012; 2013 and December 2014 Data [Available from: http://www.gdc-uk.org/Newsandpublications/factsandfigures/Pages/default.aspx 09.03.2015].M, million.

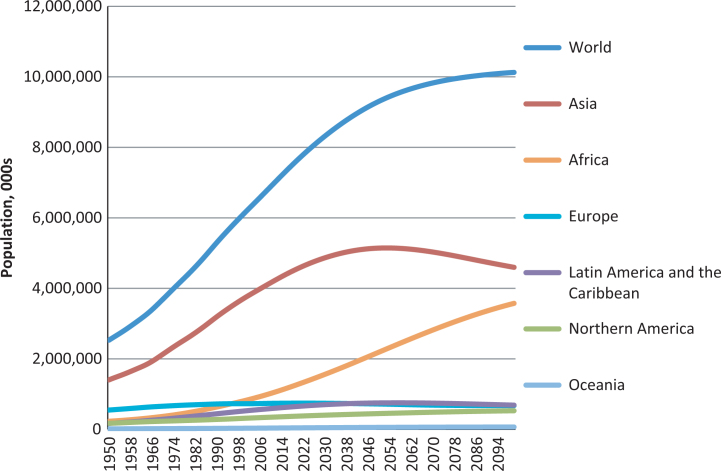

Looking to the future, population projections from the UN suggest that the populations of Asia and Africa are going to increase rapidly over the next 75 years (Figure 1). Importantly in relation to HROH, these are the two WHO regions in which large population-to-dentist ratios already exist, therefore suggesting that as the population increases, inequalities are set to increase unless there is a significant growth in dental-workforce capacity. In contrast, the population in areas that have a low number of people per dentist, such as the Americas and Europe, is predicted to increase only very slightly, whilst the number of dentists is likely to remain high and even increase.

Figure 1.

World population projections according to region and globally.

Source: United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division: World Population Prospects DEMOBASE extract. 2011.

Discussion

This paper provides evidence of current inequalities in the size and distribution of the dental workforce globally; inequalities that are predicted to increase. Furthermore, it highlights major gaps in HROH data and data quality, which must be addressed in line with the Global Strategy on Human Resources for Health, 20168. This descriptive analysis has a number of limitations that form an important component of the findings and recommendations for change.

First, the existing available global data are not all contemporary, making accurate reporting and comparison over time difficult. The pace of change at country level demonstrated in the UK, as a result of policy changes and regional migration, highlights the importance of regular monitoring. Accordingly, moving forward, regular updates from all countries are important to inform a global action in support of universal health coverage and the UN sustainable development goals.

Second, the actual sources of the data are not quoted in the databases to enable verification and updating of the data on a regular basis.

Third, even if the number of professionals is correct, it is important to recognise that the actual number of dentists does not reflect their commitment to dentistry as many choose to work part-time, or plan to do so25., 26., 27., 28., whilst others may not be working because of illness or maternity leave, or they may hold non-clinical administrative roles within the profession. Additionally, specialists can comprise up to 20% of dentists nationally29 and perhaps ought to be considered separately to primary care provision in workforce planning – a matter for further debate?

Fourth, although dental-workforce data generally are held by registration bodies, the registered workforce may not reflect the actual resident workforce. A dentist may be registered to practice in more than one country. For example, in the UK, in 2010, 6% of the GDC registrants were registered to a non-UK address22 and presumably were also on the register of their resident country and working there, or across countries. Thus, the number of dentists globally, both in actual numbers and whole time equivalents, may be lower than suggested by the data available and may not relate to workforce capacity to provide care.

Fifth, the data on dentists do not relate to the full clinical workforce as some countries have a significant volume of mid-level or ‘auxiliary’ clinical providers, such as dental therapists, hygienists, school nurses and dental assistants30, which are not reported. Interestingly, some high-income countries that already have a well-established dental profession and good dentist provision also have high auxiliary provision, further demonstrating the inequalities in HROH capacity. These professionals will not have been included in the numbers of dentists in the WHO data but are significantly contributing to dental care in these countries. Particularly in low- and middle-income countries, community health workers may play an important role in providing emergency dental care and in promoting oral health, yet there is no evidence on the extent of their contribution to the oral health agenda. Thus, in order to gain insight into dental personnel globally it would be helpful to collect data for auxiliary dental personnel as well as for dentists; this is not without its challenges, however, in that the remit and range of these mid-level providers varies greatly from country to country30.

Crude population-to-dentist ratios are acknowledged to be a very blunt instrument for workforce analysis given the caveats above. Nonetheless, such are the existing global disparities, however, that this simple method presents a very stark picture of the challenges. The data continue to suggest that over two-thirds (69%) of the world’s dentists appear to be practising in Europe and the Americas, although only 27% of the global population live in these WHO regions29. Looking to the future, given differential population growth, together with patterns of workforce education and migration, this disparity between Africa and the rest of the world is likely to increase further. And within Asia, there appears to be marked inequalities within the region because certain countries have a highly developed workforce, whereas others do not; and as a region they are likely to experience significant population growth.

Although the distribution of dentists and other dental professionals globally is far from uniform, it has to be acknowledged that the distribution of oral and dental disease is also non-uniform between and within countries. All too often, inequalities in health are compounded by poor access to dental professionals and uptake of dental care, which relate to the nature of the health-care system and the availability of HROH. In relation to future planning, population demography and needs must be considered; however, this is only possible where robust workforce and oral-health data are available. Low-income countries have difficulty in obtaining resources for surveys, both financial and human, and appear to be less likely to hold contemporary data to support the arguments for workforce development. Practitioners with no formal training and poor infection control may be the only option for pain relief, thus exposing their patients to additional health risks. Poor access to care and cost are the main factors influencing the use of alternative non-trained providers, and patients doing so have poorer reported oral health31. Addressing these issues could be helped by collaboration between high- and low-income countries working in partnership.

A professional career in dentistry spans at least four decades and so decisions on workforce training and education have long-term implications. Under current predictions, as outlined above, the population in the African and Asian regions is set to increase dramatically over the next 75 years; therefore, the population-to-dentist ratios may worsen unless there is appropriate action. Certain countries, such as India, have responded to this challenge by opening many private dental schools, with some 206 establishments currently operational32; however, this is not without its risks as there are insufficient opportunities for new graduates, which increases the risk of migration to high-income countries despite local oral health needs. It is very important to consider the issues around workforce migration in this era of global mobility, particularly as migration tends to increase inequalities in access to care between low- and high-income countries. It tends to be the more developed high-income countries that have targeted international recruitment in order to address perceived domestic shortages33; this is just one of the factors that has contributed to the growth in the UK dental workforce, together with increased student numbers34.

The needs in Africa are so great that it is not realistic, or appropriate, to meet them by training additional dentists and therefore alternative methods, such as using low- and mid-level providers, should be explored35., 36.. The Cameroon is just one of a number of countries providing evidence of the potential of mid-level providers of dental care as an alternative model37 to that of the American/European model, which has historically focussed largely on training dentists. Thus, each country needs to look carefully at the volume and composition of its current workforce, numbers in training across the dental team and workforce mobility, relating this to their oral health needs and changing population demography9, and of course paradigm of care. Given that oral diseases are largely preventable there is a strong need to tackle the wider determinants of health and re-orientate oral health-care towards prevention. Together, these initiatives, which require strong leadership, may in the longer term provide health care that is more appropriate than traditional models of dental care to the setting and population health needs.

In conclusion, major inequalities in dental-workforce provision exist globally and are evident between regions and countries. Furthermore, such inequalities are set to increase over the next 75 years, unless they are balanced by educational and health-system initiatives that train and retain appropriate HROH. New models of dental care are required to meet the oral health needs associated with the burden of non-communicable disease. Accurate and timely country-specific data on the dental workforce are therefore required to gain a clearer perspective on the global workforce and inform future developments. Overall, it is time for co-ordinated global action on HROH.

Acknowledgements

J.G. is funded by King’s College London Dental Institute and L.H. was funded by King’s College Hospital. There was no external funding for this project, which was supported by the host institutions.

Author contributions

J.G. developed the concept for this paper, and L.H. sourced and analysed the data. Both authors worked on the paper and approved the final version.

Conflict of interest

J.E.G. is the chair of the Dental Workforce Advisory Group for England within Health Education England (HEE) and is an Honorary Consultant in Dental Public Health to Public Health England (PHE). The views expressed are hers alone and do not represent the views of the National Health Service (NHS) or HEE.

References

- 1.FDI . 2nd ed. FDI World Dental Federation; Geneva: 2015. The Challenge of Oral Disease: A Call for Global Action. [Google Scholar]

- 2.United Nations . United Nations; 2011. Political Declaration of the High-level Meeting of the General Assembly on the Prevention and Control of Non-communicable Diseases. 24 January 2011. Contract No.: Agenda Item 111. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Murray CJL, Vos T, Lozano R, et al. Disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) for 291 diseases and injuries in 21 regions, 1990–2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet. 2012;380:2197–2223. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61689-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vos T, Flaxman AD, Naghavi M, et al. Years lived with disability (YLDs) for 1160 sequelae of 289 diseases and injuries 1990–2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet. 2012;380:2163–2196. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61729-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kassebaum NJ, Bernabé E, Dahiya M, et al. Global burden of untreated caries: a systematic review and metaregression. J Dent Res. 2015;94:650–658. doi: 10.1177/0022034515573272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kassebaum NJ, Bernabé E, Dahiya M, et al. Global burden of severe periodontitis in 1990–2010: a systematic review and meta-regression. J Dent Res. 2014;93:1045–1053. doi: 10.1177/0022034514552491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.GHWA, WHO . World Health Organization; Geneva: 2014. A Universal Truth: No Health without a Workforce. [Google Scholar]

- 8.World Health Organization . WHO; Geneva: 2016. Global Strategy on Human Resources for Health: Workforce 2030. Available from: http://www.who.int/hrh/resources/pub_globstrathrh-2030/en/. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gallagher JE, Wilson NHF. The future dental workforce? Br Dent J. 2009;206:195–199. doi: 10.1038/sj.bdj.2009.114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.United Nations. World Population Prospects DEMOBASE extract. 2011. In: United Nations DoEaSA, Population Division, editor. 2011.

- 11.World Health Organization . WHO; Geneva: 2016. WHO Country Assessment Tool on the Uses and Sources for Human Resources for Health (HRH) Data. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yamalik N, Mersel A, Cavalle E, et al. Collaboration between dental faculties and National Dental Associations (NDAs) within the World Dental Federation-European Regional Organization zone: an NDAs perspective. Int Dent J. 2011;61:307–313. doi: 10.1111/j.1875-595X.2011.00075.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Christensen CM, Grossman JH, Hwang J. McGraw Hill; New York, NY: 2009. Chapter 11: Regulatory Reform and the Disruption of Health Care. The Innovators’ Prescription: A Disruptive Solution for Health Care. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hobdell MH, Petersen PE, Clarkson J, et al. Global goals for oral health 2020. Int Dent J. 2003;53:285–288. doi: 10.1111/j.1875-595x.2003.tb00761.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.United Nations. Sustainable development goals 2030 2015. Available from: http://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/sustainable-development-goals/. Accessed 08 March 2017.

- 16.World Health Organization. Global Health Atlas 2009. Available from: http://apps.who.int/globalatlas/DataQuery/default.asp. Accessed 08 November 2012.

- 17.Beaglehole R, Benzian H, Crail J. Myriad Editions; Brighton: 2009. The Oral health atlas: mapping a neglected global health issue. FDI World Dental Federation; pp. 1–120. [Google Scholar]

- 18.CIA World Factbook, [Internet]. CIA; 2012. Available from: https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/rankorder/2119rank.html. Accessed 08 November 2012.

- 19.World Health Organization . WHO; Geneva: 2012. WHO Global Atlas. 08.11.2012. [Google Scholar]

- 20.The World Bank. GNI per capita (USD); 2012.

- 21.General Dental Council . General Dental Council; London: 2008. Annual Report, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 22.General Dental Council . General Dental Council; London: 2010. Dental Register: Summary Statistics Provided on Request. Annual Report. [Google Scholar]

- 23.General Dental Council. GDC Regulation Statistical Report: Annual Reports and Accounts, 2011. London; 2012.

- 24.Office for National Statistics. Population Estimates for UK, England and Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland, Population Estimates Timeseries 1971 to Current Year 2011. Available from: http://www.ons.gov.uk/ons/rel/pop-estimate/populationestimates-for-uk-england-and-wales-scotland-and-northern-ireland/population-estimates-timeseries-1971-to-current-year/index.html. Accessed 21 December 2011.

- 25.Gallagher JE, Clarke W, Wilson NHF. The emerging dental workforce: short-term expectations of, and influences on dental students graduating from a London Dental School in 2005. Prim Dent Care. 2008;15:91–101. doi: 10.1308/135576108784795392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gallagher JE, Patel R, Wilson NHF. The emerging dental workforce: long-term career expectations and influences. A quantitative study of final year dental students’ views on their long-term career from one London Dental School. BMC Oral Health. 2009;9:1–9. doi: 10.1186/1472-6831-9-35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gallagher JE, Clarke W, Wilson NHF. Why dentistry: a qualitative study of final year dental students’ views on their professional career? Eur J Dent Educ. 2008;12:89–98. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0579.2008.00506.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gallagher JE, Clarke W, Eaton K, et al. IADR; New Orleans, LA: 2007. Vocational Dental Practitioners’ Views on Healthcare Systems: A Qualitative Study. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gallagher JE. In: International Encyclopaedia of Public Health, 2. Heggenhougen K, Quah S, editors. Academic Press; San Diego, CA: 2008. Dentists; pp. 126–136. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nash DA, Friedman JW, Kardos TB, et al. Dental therapists: a global perspective. Int Dent J. 2008;58:61–70. doi: 10.1111/j.1875-595x.2008.tb00177.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Naidu RS, Gobin I, Newton JT. Perceptions and use of dental quacks (unqualified dental practitioners) and self rated oral health in Trinidad. Int Dent J. 2003;53:447–454. doi: 10.1002/j.1875-595x.2003.tb00886.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Health Medina Network for Health. Dental Colleges in India 2016 [updated 10.04.201516,10.2016]. Available from: http://www.medindia.net/education/dental_colleges.asp. Accessed 28 November 2016.

- 33.Hari Parkash H, Mathur VP, Duggal R, et al. Dental workforce issues: a global concern. J Dent Educ. 2006;70:22–26. [Google Scholar]

- 34.General Dental Council . GDC; London: 2016. Annual Report and Accounts, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 35.FDI World Dental Federation . FDI; Geneva-Cointrin: 2012. FDI World Dental Vision 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 36.World Health Organization . WHO; Geneva: 2010. Mid Level Providers: A Promising Resource to Reach the Millenium Development Goals. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Achembong L, Ashu A, Hagopian A, et al. Cameroon mid-level providers offer a promising public health dentistry model. Hum Resour Health. 2012;10:46. doi: 10.1186/1478-4491-10-46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]