Abstract

Background: Political conflicts in the Palestinian Territories (PT) have resulted in systematic deterioration of socio-economic conditions and health. The World Health Organization (WHO) has emphasised the negative impacts of social crisis on children’ oral health and quality of life. Objectives: To assess the prevalence and trends in dental caries and poor gingival health of schoolchildren in the PT through the scholastic years 1998/1999 to 2012/2013. Methods: This is a retrospective study. Prevalence data on dental caries of primary and permanent dentitions among children 6, 12 and 16 years of age were gathered from annual oral health reports of the School Dental Health Programme (SDHP)-Ministry of Health. Caries was recorded according to WHO methods and criteria. Decayed, missing and filled teeth indices for primary (dmft) and permanent (DMFT) teeth were calculated. Gingival health status was examined according to the Community Periodontal Index (scores 1 and 2). Statistical analysis used SPSS. Results: In 2012/2013, dental caries prevalence rates and the index scores among schoolchildren were as follows, respectively: 56.4% and 2.7 dmft at age 6; 42.0% and 1.4 DMFT at age 12; and 38.7% and 1.7 DMFT at age 16. For all age groups, the d/D-component of the caries indices was high. Trends of dental-caries prevalence, caries experience and gingival bleeding were fairly constant over time from 1998/1999. Conclusion: The SDHP was established in order to prevent and control oral diseases among schoolchildren in the PT. The Programme is fairly passive and the survey indicates an urgent need for reorientation of activities towards population-based prevention and health promotion. The application of the WHO Health Promoting Schools concept is highly recommended.

Key words: Dental caries, gingival health, schoolchildren

Introduction

Globally, dental caries is a most prevalent chronic disease among children, and the disease affects 60–90% of schoolchildren1. In low- and middle-income countries the occurrence of dental caries has increased during recent years because of the growing consumption of sugars, poor nutrition, insufficient oral hygiene, inadequate exposure to fluoride and limited access to oral health-care services2., 3.. Poor oral health is particularly common among children living in deprived communities. Against this pattern, a remarkable decline in dental caries experience of children has been noted in industrialised countries, in parallel with the introduction of disease-prevention and school health programmes2., 4.. School health programmes are found to develop lifestyles important to oral health, encourage self-care practices, enable the effective use of fluoride for prevention of dental caries and to advance access to primary health-care services2., 5..

The Occupied Palestinian Territories have suffered from political conflicts and wars for decades. The political conditions have produced a serious deterioration in the economic and social lives of Palestinian people in both the Gaza Strip and the West Bank6., 7.. The prevalence of chronic and infectious diseases is high. Health programmes have been established by the Ministry of Health and the United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees in the Near East (UNRWA) but face severe financial restrictions that limit their ability to meet all the health needs of people7., 8..

The poor oral-health status of Palestinian children is caused by several factors. In addition to harmful sociobehavioural environments, oral health services are not universally available and services are not oriented effectively towards disease prevention and health promotion. Moreover, children have a low energy intake (5.17 ±1.41 MJ/day)9 which includes a high contribution of non-milk-extrinsic (NME) sugars (12.2%), well above the World Health Organization (WHO) critical standard of sugar intake to total energy10. Data collected from Department of Environmental Health in the Ministry of Health and Water Authority in Palestine have shown that the concentration of fluoride in drinking water is rather low (0.10–0.53 ppm F) in the West Bank, while somewhat higher in the Gaza Strip (0.00–9.6 ppm F). No water-fluoridation programmes for prevention of dental caries have been introduced in areas with a low concentration of fluoride in the drinking water and unfortunately very few Palestinian children have regular toothbrushing habits in childhood8., 9., 11., 12..

The WHO emphasises that underprivileged people often cannot afford dental treatment and this is particularly observed in vulnerable population groups. Consequently, in 2007 the World Health Assembly agreed on an action plan for oral health (Resolution WHA60.17) which emphasised the importance of primary health care for promoting the oral health of people living in poor societies13. In relation to children, school-based oral health intervention is essential as programmes serve large groups of children early in life and during the crucial period of their development14.

Oral diseases have a profound impact on a child’s performance in school, nutritional intake, growth and quality of life. To promote the oral health of Palestinian children and adolescents, the Palestinian Ministry of Health and UNRWA run the Palestinian School Dental Health Programme as part of the National Primary Health Care System. This programme was introduced in 1994 and aims to provide dental care for schoolchildren attending governmental, refugee (UNRWA) and private schools in the Palestinian Territories (the Gaza Strip and the West Bank)15. Children and adolescents were enrolled in the Programme on an incremental basis.

The objectives of the School Dental Health Programme are to prevent and control oral disease through screening and referral for dental care in primary health-care dental clinics and follow-up services, and to develop awareness of oral health through health communication and health promotion15. UNRWA has implemented a comprehensive preventive programme for children and mothers and operates from mobile dental clinics in all UNRWA schools in Palestinian camps16. Annual reports from the Palestinian Ministry of Health and UNRWA inform about poor oral health in schoolchildren11., 17.. Unfortunately, systematic studies evaluating the effect of the school dental-health programmes in the Palestinian Territories have not been conducted.

Therefore, the aim of this study was to measure the long-term trend of dental caries and gingival health in 6-, 12- and 16-year-old schoolchildren attending governmental and private schools in the Palestinian Territories during the scholastic years 1998–1999 to 2012–2013, to assess the need for dental care and to examine whether there are any differences in dental caries prevalence and experience between schoolchildren living in the Gaza Strip and the West Bank. This research was initiated to assess the appropriateness of the School Dental Health Programme and to assist the Ministry of Health in surveillance of oral health and in monitoring of the school programme as implemented by the Palestinian public health authorities.

Methods

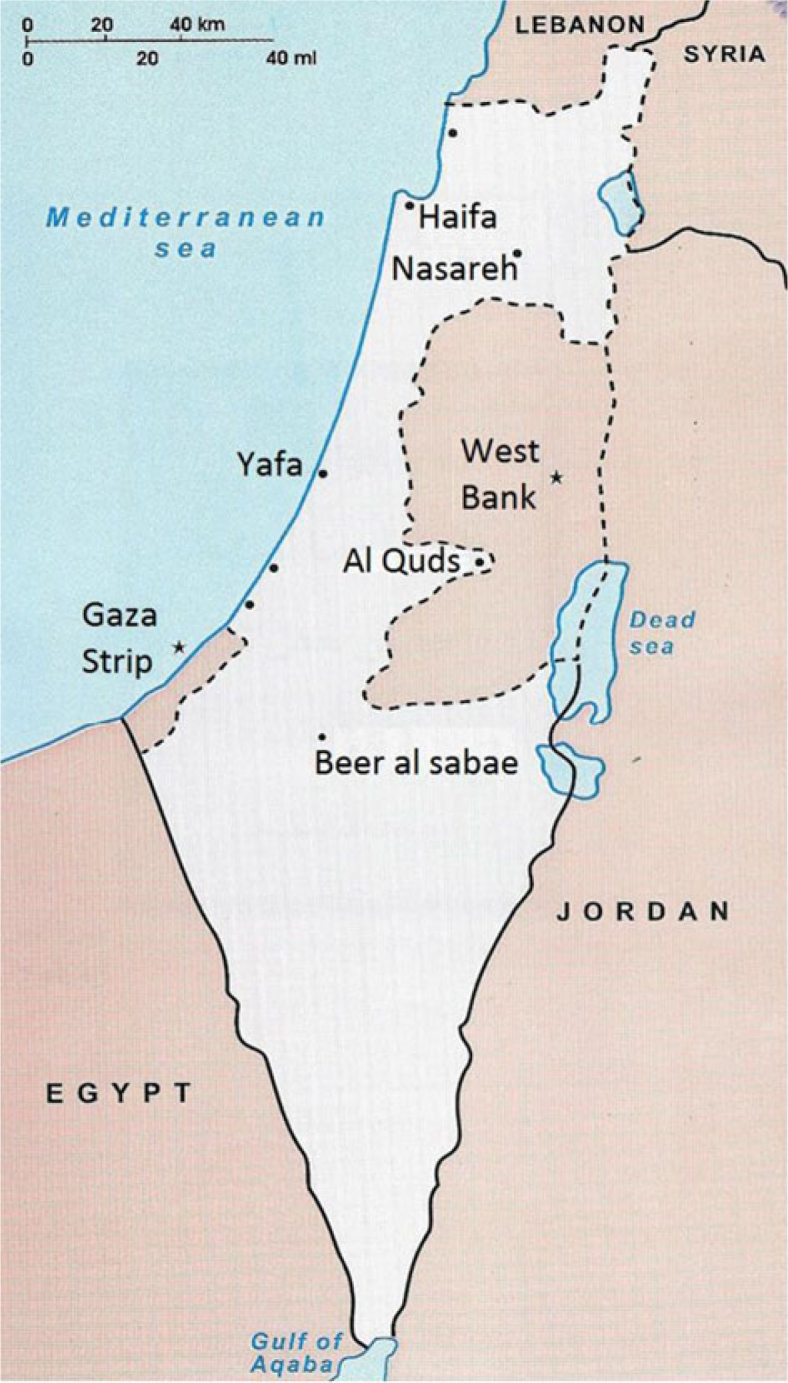

The Palestinian Territories comprise two geographically separated areas – the West Bank and the Gaza Strip (Figure 1). The West Bank encompasses an area of 5,800 km2 west of the River Jordan. The Gaza Strip is a narrow piece of land along the eastern coast of the Mediterranean Sea. The Gaza Strip is a highly populated territory with an area of 360 km2., 6., 18.. In 2014, the Palestinian population was approximately 4.55 million (2.79 million in the West Bank and 1.76 million in the Gaza Strip). Children under 15 years of age comprised 40.4% of the population (37.6% in the West Bank and 43.2% in the Gaza Strip)19. Refugees account for 71.3% of residents in the Gaza Strip and 31.7% of residents in the West Bank20.

Figure 1.

Map of the Palestinian Territories.

A reporting system has been established by the School Dental Health Programme to carry out surveillance of oral health among children served. The present study comprised all schoolchildren of 1st (6 years old), 7th (12 years old) and 10th (16 years old) grades covered by the Programme in the Palestinian Territories. The study population and average participation rates are summarised in Table 1.

Table 1.

Number of schoolchildren examined in 1st, 7th and 10th grade (6, 12 and 16 years of age) in Palestinian Territories in the scholastic years from 1998–1999 to 2012–2013 and average participation rates

| Scholastic year | No. of pupils examined | Participation rate of examination for the three grades | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1st grade (6 years of age) | 7th grade (12 years of age) | 10th grade (16 years of age) | ||

| 1998–1999 | 53,484 | 24,713 | 25,555 | 93.5 |

| 1999–2000 | 56,130 | 33,373 | 32,424 | 96.2 |

| 2000–2001 | 58,293 | 42,510 | 38,349 | 90.7 |

| 2001–2002 | 49,529 | 37,847 | 39,716 | 88.3 |

| 2002–2003 | 52,525 | 48,917 | 48,902 | 96.3 |

| 2003–2004 | 46,854 | – | – | 96.1 |

| 2004–2005 | 58,255 | 60,220 | 59,060 | 96.3 |

| 2005–2006 | – | – | – | 94.9 |

| 2006–2007 | 29,572 | 27,323 | 37,118 | 46.7 |

| 2007–2008 | 25,050 | 24,601 | 33,163 | 97.4 |

| 2008–2009 | 44,170 | 53,197 | 57,303 | 97.6 |

| 2009–2010 | 51,856 | 47,602 | 59,786 | 96.1 |

| 2010–2011 | 50,346 | 48,282 | 70,074 | 97.4 |

| 2011–2012 | 53,979 | 55,215 | 70,145 | 97.6 |

| 2012–2013 | 56,355 | 56,048 | 68,440 | 97.5 |

–,Values not available in Annual Health Reports of Ministry of Health in Palestinian Territories.

Data were obtained from annual health reports of the School Dental Health screening reports submitted to the Ministry of Health from 1998–1999 to 2012–2013.

Information was assembled on the prevalence of dental caries, namely caries experience of primary teeth as expressed by the dmft index [decayed, missing because of caries (extracted) and filled teeth] and by the DMFT index for caries in permanent teeth (Decayed, Missing because of caries, and Filled Teeth). The recording of dental caries followed the criteria recommended by the manual WHO Oral Health Surveys – Basic Methods21. Examinations included recording of dental caries at the cavity level observed under artificial light using dental mirrors and the WHO CPI periodontal probe. Gingival health status was assessed using the Community Periodontal Index (CPI) criteria of gingival bleeding. Dental officers of the School Dental Health programme were responsible for clinical examinations and a total of 13 dentists in the West Bank and eight dentists in the Gaza Strip were involved. Dentists engaged with school health teams examined children in classrooms. The dentists participated in training courses on the WHO methods used for clinical examinations and calibration. The examiners had to achieve Kappa scores greater than 0.7. The WHO standard for consistency of recording of dental caries and gingival health status was achieved21.

This study was reviewed and approved by the Ethics Committee in Palestine and was conducted according to the guidelines defined in the Declaration of Helsinki. The data used in the study were public health administrative data, and it was anonymised and de-identified before analysis. The IBM Statistical Package of Social Sciences Statistics (SPSS) Version 20 (IBM, SPSS, Armonk, NY, USA) was used for data entry and data analyses. The prevalence of dental caries and the mean dmft/DMFT were computed for statistical analyses. The chi-square test was applied for statistical evaluation of prevalence proportions, while the Student’s t-test or analysis of variance was used for evaluation of means. Time series analyses encompassed children living in the same settings and were organised according to the annual examinations of schoolchildren.

Results

Throughout the years 1998–1999 to 2012–2013 a remarkable increase in the number of children and adolescents covered by the School Dental Health Programme took place. At 1st grade (age 6) the number of children participating increased from 53,484 to 56,355, at 7th grade (age 12) the number increased from 24,713 to 56,048 and at 10th grade (age 16) the number increased from 25,555 to 68,440. In the scholastic years 2012–2013, the participation rate in school dental and oral health examinations was 97.5% of the target group, as shown in Table 1.

Table 2 presents the prevalence of dental caries and the mean dental caries experience in Palestinian children and adolescents according to age. Slightly more than half of the Palestinian children at age 6 had dental caries in their primary teeth, and on average their dental caries experience was 2.7 dmft. In all, the proportion of affected primary teeth in need of dental care was 80%. The prevalence rate and the amount of dental caries were significantly higher among children from the West Bank compared with children from the Gaza Strip (P < 0.001). The mean dental caries experience of children in the West Bank was approximately twice the mean of that for children of the Gaza Strip. At ages 12 and 16, around 40% of individuals were affected by dental caries in their permanent teeth and the amount of caries was 1.37 and 1.7 DMFT, respectively. As a whole, the number of affected permanent teeth requiring dental care was 78% among 12 year-old-schoolchildren and 68% among 16-year-old schoolchildren. In parallel, the caries prevalence rate and the severity of dental caries in the permanent dentition were relatively higher among individuals from the West Bank than the Gaza Strip (P < 0.01).

Table 2.

Dental caries prevalence (%) and mean caries experience [decayed, missing and filled teeth indices for primary teeth (dmft) and permanent teeth (DMFT)] of Palestinian schoolchildren 6, 12 and 16 years of age, according to the area of residence in the 2012–2013 scholastic year

| Indicators | Gaza Strip | West Bank | Palestinian Territories |

|---|---|---|---|

| 6 years old (Grade 1) | n = 17,009 | n = 39,346 | N = 56,355 |

| Caries prevalence (%) | 36.1 | 65.5*** | 56.4 |

| dt | 1.09 | 2.64 | 2.17 |

| mt | 0.19 | 0.42 | 0.35 |

| ft | 0.17 | 0.11 | 0.13 |

| dmft | 1.5 | 3.2** | 2.7 |

| 12 years old (Grade 7) | n = 14,000 | n = 42,048 | N = 56,048 |

| Caries prevalence (%) | 26.0 | 47.5* | 42.0 |

| DT | 0.46 | 1.28 | 1.07 |

| MT | 0.04 | 0.12 | 0.10 |

| FT | 0.11 | 0.22 | 0.2 |

| DMFT | 0.6* | 1.6* | 1.37 |

| 16 years old (Grade 10) | n = 29,330 | n = 39,110 | N = 68,440 |

| Caries prevalence (%) | 23.9 | 49.7* | 38.7 |

| DT | 0.57 | 1.58 | 1.15 |

| MT | 0.08 | 0.18 | 0.14 |

| FT | 0.27 | 0.49 | 0.39 |

| DMFT | 0.9* | 2.3* | 1.7 |

dt, mt, ft, index of decayed, missing or filled primary teeth; DT, MT, FT, index of decayed, missing or filled permanent teeth.

*P < 0.01; **P < 0.001; ***P < 0.0001.

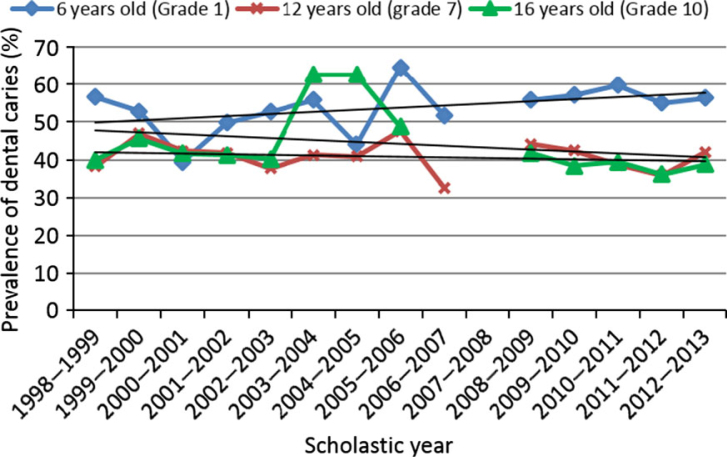

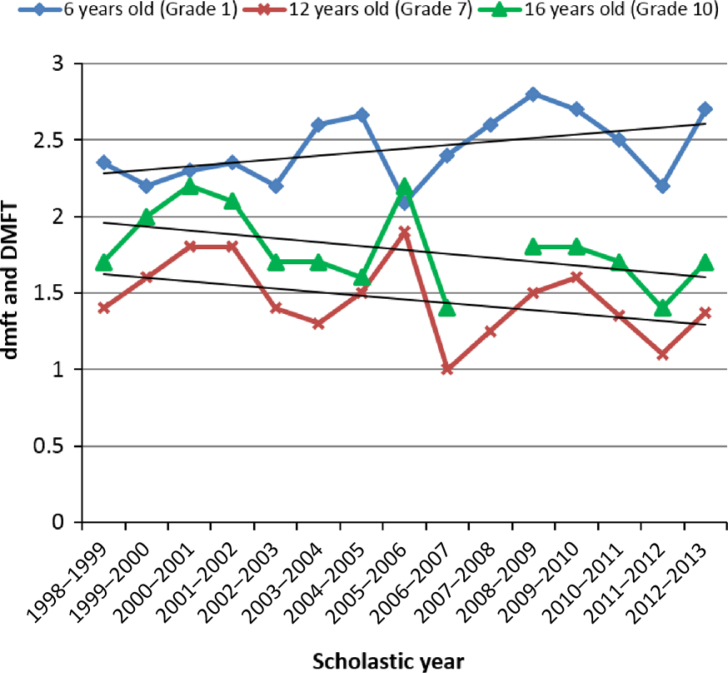

Figures 2and3 show the trends in the prevalence rate of dental caries and in dental caries experience for the scholastic years 1998–1999 to 2012–2013. The data refer to children of ages 6 and 12 years, and adolescents aged 16 years, in governmental and private schools in the Occupied Palestinian Territories. In general, the prevalence of dental caries was high among children 6 years of age and a slight increase over time was indicated. Meanwhile, the prevalence of dental caries showed minimal fluctuation in the 12- and 16-year-old schoolchildren. In parallel, for each year of study the caries experience level of 6-year-old schoolchildren was higher than in the two older age groups (i.e. 12- and 16-year-old schoolchildren). It is noteworthy that fluctuations over time were similar.

Figure 2.

Prevalence (%) of children with decayed teeth in 6-, 12- and 16-year-old schoolchildren (1st, 7th and 10th grades, respectively) in governmental and private schools in the Palestinian Territories.

Figure 3.

Mean dental caries experience (dmft/DMFT) in 6-, 12- and 16-year-old schoolchildren (1st, 7th and 10th grades, respectively) in governmental and private schools in the Palestinian Territories. dmft, decayed, missing and filled tooth index for primary teeth; DMFT, decayed, missing and filled tooth index for secondary teeth.

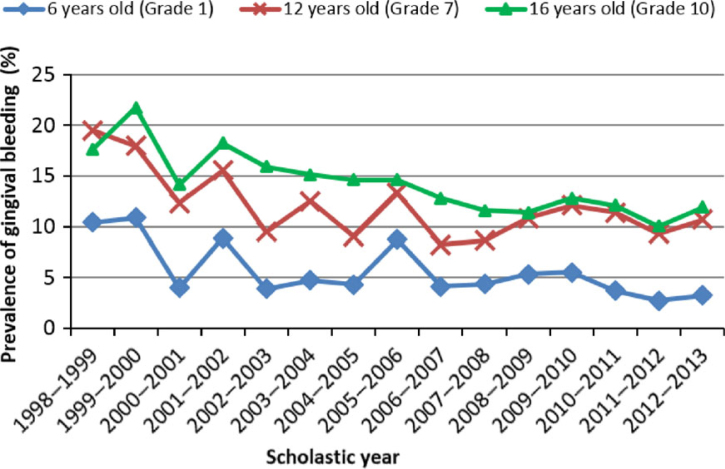

Gingival health

At the examination in 2012–2013, about 10% of 12- and 16-year-old schoolchildren were affected by gingival bleeding, demonstrating a decrease from just below 20% in 1998–1999. As shown in Figure 4, the prevalence of gingival bleeding was lower among 6-year-old schoolchildren compared with 12- and 16-year schoolchildren, decreasing from slightly over 10% in 1998–1999 to 3% in 2012–2013.

Figure 4.

Prevalence (%) of gingival bleeding (according to Community Periodontal Index) criteria: score 1 and score 2 in 6-, 12- and 16-year-old school children (1st, 7th and 10th grades, respectively, respectively) in governmental and private schools in the Palestinian Territories.

Discussion

Different national and local community surveys22., 23., 24. indicate that the prevalence of dental caries among children of certain Middle East countries is moderate according to the criteria of the WHO3. Meanwhile, surveys of 6-year-old schoolchildren carried out in certain countries around Palestine showed high prevalence rates (80–85%) of disease in primary teeth25., 26., 27.. A number of studies were undertaken in the late 1990s in order to assess dental caries experience of permanent teeth among children 12 years of age; DMFT estimates were reported as follows: 2.69 in Saudi Arabia22; 1.5 in Oman28; 1.5 in Iran26; 1.7 in Iraq29; 2.6 in Kuwait27; and 2.3 in Syria30. In the neighbouring country of Jordan31, 6-year-old schoolchildren had a prevalence of dental caries of 76% while the DMFT score was 1.1 at the age of 12.

In the present survey, clinical examinations were carried out by experienced dentists trained in WHO methods and criteria; calibration trials were conducted and the reproducibility level achieved was acceptable and consistent with the WHO criteria21. Children served by the School Dental Health Programme are considered as representative of children and adolescents living in the West Bank and in the Gaza Strip. The epidemiological survey in 2012–2013 was a population study because it comprised nearly all Palestinian schoolchildren (participation rate 97.5%) of the WHO standard ages. Obviously, the population group was lower in 1998–1999 and onwards as the programme was based on incremental enrolment of schoolchildren; importantly, the large number of participants ensures that valid estimates of disease are calculated and makes it possible to assess the disease profiles for each year of the survey.

Compared with other countries of the region, the current study of Palestinian children as a whole showed a somewhat lower prevalence rate among 6-year-old schoolchildren while the total caries experience of 12-year-old schoolchildren was moderate and similar to the level in Jordan31. Remarkably, the proportion of 6-year-old schoolchildren being free of dental caries was lower than the goal of at least 50% set by the WHO for the year 200032, whereas caries experience at age 12 was lower than the WHO maximum of 3 DMFT. For children of all ages, the prevalence of dental caries in the West Bank was nearly twice as high as the level among children in the Gaza Strip (Table 2); moreover, the amount of dental caries in children of the West Bank was approximately 2.5 times higher than the amount of dental caries in children of the Gaza Strip. The relatively lower level of disease in the Gaza Strip may be associated with a high concentration of fluoride (>1.5 ppm F) in home supply drinking water. Previous research in Palestine found a high positive association between dental fluorosis and fluoride concentration in drinking water; dental fluorosis varied between 60% and 78% among children exposed to drinking water which contained a high level of fluoride33., 34.. It is also worth noting that the need for dental care was high in both areas; for children 6 and 12 years of age, untreated dental caries made up around 80% of the total caries index. In parallel, among 16-year-old schoolchildren, two-thirds of teeth affected by dental caries were in need of dental care.

The School Health Programme run by the Palestinian Ministry of Health15 was established in 1994 to promote general and oral health of students in governmental and private schools. Oral health examinations of schoolchildren 6, 12 and 16 years of age were introduced for continuous evaluation of the dental health programme and to observe if oral health conditions would improve following introduction of preventive services23. The present time series analysis illustrates only minor changes in the occurrence of dental caries among children of all ages through the years 1998/1999 to 2012/2013. The analyses showed some yearly fluctuations in dental caries prevalence and in caries experience but the level of disease remained fairly stable. Unfortunately, no systematic studies have been carried out on possible changes in toothbrushing habits, fluoride exposure and consumption patterns of processed food and sugars over time, which might explain the fluctuations of dental caries observed among Palestinian schoolchildren. A few studies measured the contribution of NME sugars to total energy intake10, and case studies considered toothbrushing habits in childhood for Palestinian schoolchildren8., 9., 11., 12.. Thus, further studies are required to investigate any relationships between dental caries fluctuation and behavioural factors. Two factors indicate that the existing school dental health programme is somewhat insufficient in controlling dental caries: the treatment needs of children and adolescents are not covered adequately; and the burden of disease remains constant despite intervention.

The assessment of gingival health conditions was based on WHO criteria21. The prevalence of gingival bleeding among children and adolescents was relatively lower than observed in similar studies carried out in the region35. Therefore, some underestimation of the prevalence of gingival bleeding cannot be excluded. In Jordan, the rate of gingival bleeding among children 6 years of age was reported to be 17%31. It is worth noting that in Palestine the data on gingival health parallels the information obtained on dental caries (i.e. the occurrence of gingival bleeding was fairly constant throughout the time period).

The actual study verified that the oral health situation of children and adolescents in the Palestinian Territories is far from under control. It is anticipated that a substantial number of children and adolescents do not benefit sufficiently from education in school because of oral pain and discomfort. The existing school dental health programme in Palestine is somewhat passive; in addition to provision of oral health information, children have their teeth screened to detect if they are in need for dental care and referred for services by dentists at primary health services. Thus, systematic dental care should be organised to meet the needs of children and adolescents.

The disease burden may grow even worse unless population-directed oral disease prevention is strengthened. It is a matter of urgency to bring dental caries of schoolchildren under control through effective use of fluoride; sufficient exposure to fluoride for prevention of dental caries must include the adoption of regular toothbrushing habits by children and their use of fluoride-containing toothpaste (1,000–1,500 ppm F)36.

Primary schools are a unique platform for promotion of oral health in children and for creation of health support by parents. Children and adolescents spend considerable time in school and can be educated while their health habits are developing. The WHO has launched an efficient approach to school health work; the Health Promoting School (HPS) concept5., 13. has been shown to be applicable to oral health promotion oriented towards children and parents, and activities should involve schoolteachers with adequate training in health education at the classroom level. Active involvement of children, coupled with reinforcement of activities, is the key to effective learning from classroom-based oral health education, and regular group meetings with parents are instrumental to the advancement of parental support for oral health of children. The HPS concept aims at tackling the risk factors common to oral disease and chronic disease as it focusses on improving healthy lifestyles, including a healthy diet, low intake of sugars and personal hygiene of children and adolescents. Furthermore, promoting healthy environments is an important ambition of the approach.

Recently, such project has been established by the Ministry of Health in the Palestinian Territories based on the WHO HSPS concept. The project is being implemented by the School Dental Health Programme in collaboration with the WHO. The present study may serve as a baseline for evaluation of the effect of a strengthened school oral health programme in Palestine.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to project support from the Palestinian Ministry of Health. The study had no external funding.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.World Health Organization . World Health Organization; Geneva: 2013. The Oral Health Country Area Profile Project. Available from: www.mah.se/CAPP/Country-Oral-Health-Profiles. Accessed 1 February 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Petersen PE. Socio behavioral risk factors in dental caries – international perspectives. Community Dent Oral. 2005;33:274–279. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0528.2005.00235.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Petersen PE, Bourgeois D, Ogawa H, et al. The global burden of oral diseases and risks to oral health. Bull World Health Organ. 2005;83:661–669. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Marthaler TM, O’Mullane DM, Vrbic V. The prevalence of dental caries in Europe 1990–1995. Caries Res. 1996;30:237–255. doi: 10.1159/000262332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jürgensen N, Petersen PE. Promoting oral health of children through schools – results from a WHO global survey 2012. Community Dent Health. 2013;30:204–221. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ministry of Health . Ministry of Health-Health Management Information System; Palestine: 2006. The Status of Health in Palestine: Annual Report 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Abdeen Z, Greenough PG, Chandran A, et al. Assessment of the nutritional status of preschool-age children during the Second Intifada in Palestine. Food Nutr Bull. 2007;28:274–282. doi: 10.1177/156482650702800303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.UNRWA United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees in the Near East Department of Health . UNRWA; Jordan: 2011. The Annual Report of the Department of Health 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Abuhaloub L, Maguire A, Moynihan P. Total daily fluoride intake and the relative contributions of foods, drinks and toothpaste by 3–4 year-old children in the Gaza Strip – Palestine. Int J Paediatr Dent. 2015;25:127–135. doi: 10.1111/ipd.12108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Abuhaloub L, Maguire A, Moynihan P. Newcastle University; Newcastle Upon Tyne, UK: 2009. Identification of Sources of Fluoride Intake and Body Retention of Fluoride in Four-Year-Old Children in the Gaza Strip: Working Towards a Strategy for Dental Fluorosis Prevention. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ministry of Health . Ministry of Health-Health Management Information System; Palestine: 2011. The Annual Report of Oral Health Department. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ministry of Health . Ministry of Health-PHIC; Palestine-Gaza: 2014. Health Status in Palestine 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Petersen PE. World Health Organization global policy for improvement of oral health – World Health Assembly 2007. Int Dent J. 2008;58:115–121. doi: 10.1111/j.1875-595x.2008.tb00185.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.World Health Organization . World Health Organization; Geneva: 2003. WHO Information Series on School Health – Document 11 – Oral Health Promotion: An Essential Element of a Health-Promoting School. Available from: www.who.int/oral_health/media/en/orh_school_doc11.pdf. Accessed 10 September 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ministry of Health . Ministry of Health-Health Management Information System; Palestine: 2003. Health Status in Palestine 2002: Annual Report. [Google Scholar]

- 16.UNRWA United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees in the Near East . UNRWA; 2013. Emergency Appeal Report, oPt January – June 2013. Available from: http://www.unrwa.org/resources/reports/emergency-appeal-report-opt-January-%E2%80%93-June-2013. Accessed 15 October 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 17.UNRWA United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees in the Near East Department of Health . UNRWA; 2012. The Annual Report of the Department of Health 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shomar B, Müller G, Yahya A. Seasonal variations of chemical composition of water and bottom sediments in the wetland of Wadi Gaza, Gaza Strip. Wetl Ecol Manag. 2005;13:419–431. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics . Palestinian National Authority: Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics; 2015. Main Statistical Indicators in the West Bank and Gaza Strip. Available from: http://www.pcbs.gov.ps/Portals/_Rainbow/StatInd/StatisticalMainIndicators_E.htm. Accessed 22 May 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 20.UNRWA United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees in the Near East Department of Health . UNRWA; 2010. The Annual Report of the Department of Health 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 21.World Health Organization . 4th ed. World Health Organization; Geneva: 1997. Oral Health Surveys – Basic Methods. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Al-Tamimi S, Petersen PE. Oral health situation of schoolchildren, mothers and schoolteachers in Saudi Arabia. Int Dent J. 1998;48:180–186. doi: 10.1111/j.1875-595x.1998.tb00475.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vigild M, Skougaard MR, Hadi R, et al. Dental caries and dental fluorosis among 4-, 6-, 12- and 15-year-old children in kindergartens and public schools in Kuwait. Community Dent Health. 1996;13:47–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rajab LD, Petersen PE, Bakaeen G, et al. Oral health behaviour of schoolchildren and parents in Jordan. Int J Paediatr Dent. 2002;12:1–7. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-263x.2002.00359.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Al-Ismaily M, Chestnutt IG, Al-Khussaiby A, et al. Prevalence of dental caries in Omani 6-year-old children. Community Dent Oral. 1997;14:171–174. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pakshir HR. Oral health in Iran. Int Dent J. 2004;54(suppl 1):367–372. doi: 10.1111/j.1875-595x.2004.tb00013.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Al-Mutawa SA, Shyama M, Al-Duwairi Y, et al. Dental caries experience of Kuwaiti schoolchildren. Community Dent Health. 2006;23:31–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Al-Ismaily M, Al-Busaidy K, Al-Khussaiby A. The progression of dental disease in Omani schoolchildren. Int Dent J. 2004;57:409–410. doi: 10.1111/j.1875-595x.2004.tb00019.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ahmed NA, Astrøm AN, Skaug N, et al. Dental caries prevalence and risk factors among 12-year old schoolchildren from Baghdad, Iraq: a post-war survey. Int Dent J. 2007;57:36–44. doi: 10.1111/j.1875-595x.2007.tb00116.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Beiruti N, Van Palenstein Helderman WH. Oral health in Syria. Int Dent J. 2004;54(suppl 1):383–888. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rajab LD, Petersen PE, Baqain Z, et al. Oral health status among 6- and 12-year-old Jordanian schoolchildren. Oral Health Prev Dent. 2014;12:99–107. doi: 10.3290/j.ohpd.a31220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.WHO/FDI Global goals for oral health in the year 2000. FDI. Int Dent J. 1982;32:74–77. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shomar B, Muller G, Yahya A, et al. Fluorides in groundwater, soil and infused black tea and the occurrence of dental fluorosis among school children of the Gaza strip. J Water Health. 2004;2:23–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Abuhaloob L, Abed Y. Dental fluorosis and associated risk factors in Gaza Strip children. Birzeit Water Drops. 2011;9:93–106. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Petersen PE, Ogawa H. The global burden of periodontal disease: towards integration with chronic disease prevention and control. Periodontol 2000. 2012;60:15–39. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0757.2011.00425.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Petersen PE, Ogawa H. Prevention of dental caries through the use of fluoride – the WHO approach. Community Dent Health. 2016;33:68–69. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]