Abstract

Introduction: ‘Quality’ in primary care dentistry is poorly defined. There are significant international efforts focussed on developing quality measures within dentistry. The aim of this research was to identify measures used to assess quality in primary care dentistry and categorise them according to which dimensions of quality they attempt to measure. Methods: Quality measures were identified from the peer-reviewed and grey literature. Peer-reviewed papers describing the development and validation of measures were identified using a structured literature search. Measures from the grey literature were identified using structured searches and direct contact with dental providers and institutions. Quality measures were categorised according to domains of structure, process and outcome and by disaggregated dimensions of quality. Results: From 22 studies, 11 validated measure sets (comprising nine patient satisfaction surveys and two practice assessment instruments) were identified from the peer-reviewed literature. From the grey literature, 24 measure sets, comprising 357 individual measures, were identified. Of these, 96 addressed structure, 174 addressed process and 87 addressed outcome. Only three of these 24 measure sets demonstrated evidence of validity testing. The identified measures failed to address dimensions of quality, such as efficiency and equity. Conclusions: There has been a proliferation in the development of dental quality measures in recent years. However, this development has not been guided by a clear understanding of the meaning of quality. Few existing measures have undergone rigorous validity or reliability testing. A consensus is needed to establish a definition of quality in dentistry. Identification of the important dimension of quality in dentistry will allow for the production of a core quality measurement set.

Key words: Quality, measurement, improvement, indicators

INTRODUCTION

Improving quality in primary dental care is a goal of international interest1., 2.. To improve the quality of health care, a definition of quality and the criteria used to assess quality must be established3. Most definitions of quality in primary care relate to medicine. Within medicine, several different definitions have been described4., 5., 6., 7., 8., 9., 10., 11., 12., 13.. Dentistry has a number of significant differences from medicine, which has led to suggestion of the need for a specific definition of quality in dentistry to be developed3. Whilst some specific definitions for quality in dentistry have been offered14., 15., there is no agreed definition or conceptual framework available describing what quality means for primary dental care1., 3., 16.. The World Dental Federation (FDI) has defined quality as ‘an iterative process involving dental professionals, patients and other stakeholders to develop and maintain goals and measures to achieve optimal health outcomes’2. This statement highlights the importance of measurement of quality in the process of improving patient care. However, the constituent parts of this and other definitions need to be considered further to ensure that all of the key dimensions of quality are captured. Furthermore, the view that dentistry is so different from other areas of health care that it merits its own definition must be tested.

Many quality assurance and improvement schemes have been attempted but are hampered by a weak evidence base17. The Institute of Medicine (IoM) in the USA has stated that quality measures in dentistry ‘lag far behind’ those in medicine and other health professions18. The IoM suggests that construction of quality measures would help to improve oral health and reduce inequalities18. A first step in this process would be to develop a comprehensive understanding of what type of measures have been developed and what dimensions of quality they are attempting to measure. Quality is complex and multi-dimensional; therefore, a structured approach to terminology usage is necessary to avoid confusion. We propose the following terminology for categorising quality measures:

Domains

The Donabedian system-based model of quality states that quality measures may address one or more of three domains, namely: the structures that contribute to the delivery of care; the processes of care; and the outcomes of care6. Measures of structure include assessments of the provision of facilities, staff and training. Process measures assess what the practitioner actually does, and outcomes measurements assess the impact of an intervention6. Evidence is required to show that the measurement and improvement of processes will lead to an improvement in outcomes19, for example, if placement of fissure sealants (process) leads to prevention of caries (outcome).

Dimensions

Quality may be disaggregated into different dimensions. These dimensions each give a partial view of quality7. The IoM definition of quality identifies dimensions of safety, effectiveness, timeliness, patient-centredness, efficiency and equity13. There is no consensus on the dimensions of quality that are most pertinent to dentistry.

An ideal measure set in dentistry would address each of the dimensions of quality across the domains of structure, process and outcome.

The aim of this research was to identify measures used to assess quality in primary care dentistry. Measures were categorised according to the IoM’s dimensions of quality and the Donabedian domains of the IoM. The identification of these measures will assist in the production of a framework to support further development of quality measures in dentistry.

METHODS

Peer-reviewed literature

A systematic search strategy was used to identify measures from the published literature (Appendix 1). Each identified measure was assessed for internal and external validity. The constituent parts of each measure were assessed for the Donabedian domain and IoM disaggregated dimension of quality that they measure.

Inclusion criteria

Types of study

Any cross-sectional or longitudinal study concerning the development or validation of a quality measure in primary care dentistry or that uses a previously reported measure.

Types of measure

The types of measure included were those that may be used by a dentist, patient or other stakeholder to assess quality in a primary care setting.

Studies were only selected if they presented the process by which the measure was developed and validated in sufficient detail. Measures that had their validity confirmed in later studies were also included.

Exclusion criteria

Non-peer-reviewed studies or opinion pieces, studies published in a language other than English, studies published pre-1970 and studies that did not describe development or validity testing of the measure were excluded.

Measures of oral health-related quality of life (OHRQoL), being primarily epidemiological tools, were excluded.

A structured systematic literature search was produced for use in MEDLINE (Appendix 1) and adjusted for other databases. The Databases used were MEDLINE via OVID (1946 to present), Psychinfo via OVID (1806 to present), EMBASE via OVID (1980 to present), Health and Psychosocial Instruments via OVID (1985 to present) and Social Policy and Practice via OVID.

The screening process was managed using an Endnote Library; references were initially screened according to title and abstract by MB, AG, MT, SC and LO, and irrelevant papers were removed. The remaining papers were double screened by MB and AG, with disagreements discussed with MT. Full-text papers were obtained for the remaining included studies. Reference lists of these studies were hand searched to obtain key sources that described the development or validation of the measures. Key journals were directly searched to identify articles that may have been missing from the literature search strategy.

Grey literature

Searching of the grey literature was completed using the OpenGrey database20 and through hand searching of the websites of large dental providers, dental associations, insurers and government bodies in English-speaking nations (the USA, Canada, the UK, Australia and New Zealand). Dental insurers and large corporate dental providers were contacted directly and asked to state any quality measures they use. The National Quality Forum’s ‘Environmental Scan, Gap Analysis & Measure Topics Prioritization’ was consulted, as this project had similar goals of measure identification as the present study17. A number of the measures identified within this study are no longer in use and were thus omitted. As measures from the grey literature are actively measuring and affecting clinical practice, exclusion criteria were limited to non-English references and publication before 1970.

Evaluation and categorisation of measures

As there is no established measure to assess the quality of quality measures within primary care dentistry, the measures were individually assessed to determine their internal and external validity. Measures that did not demonstrate face validity were excluded. Evaluation of the internal consistency of measures, such as Cronbach’s alpha scores, was extracted. An α < 0.5 suggests unacceptable internal consistency of the measure21. Measures of test–retest reliability, such as intraclass correlation coefficients and Spearman’s rank correlation coefficients, were also extracted. Each measure was categorised according to the Donabedian domains of Structure, Process and Outcome and then assessed against the six disaggregated dimensions of quality of the IoM definition of quality.

Method of analysis and synthesis

Structured tables were used to describe the data from each measure narratively to give an overview of the domains of quality evaluated using each measure and the dimensions of quality they address.

RESULTS

Measures from the peer-reviewed literature

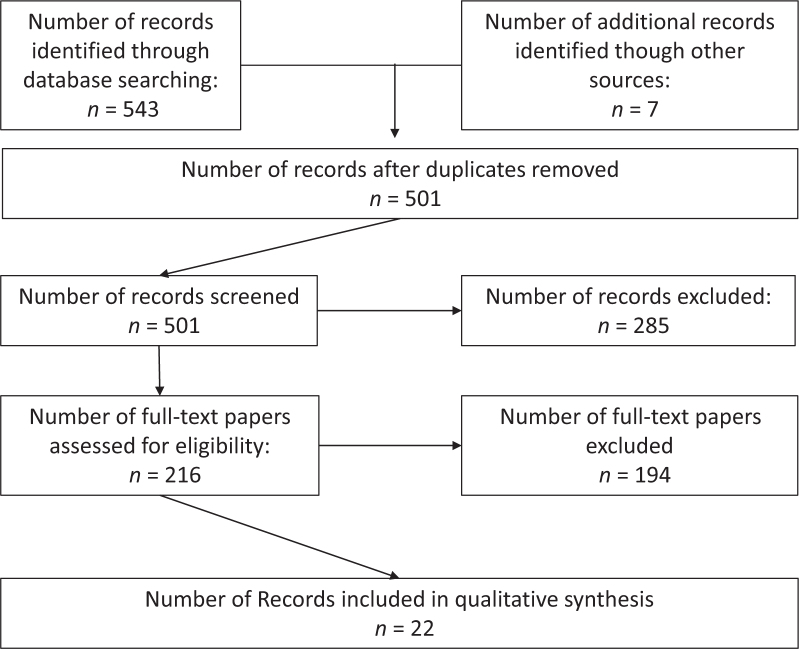

A flow diagram of the screening process is presented in Figure 1. A total of 543 papers were generated from the structured literature search. Seven additional papers were identified following further searches. Removal of 49 duplicates gave 501 papers for initial analysis. Of these, 285 were excluded as they were irrelevant. The full text of the remaining 216 papers was assessed. Following this, 22 papers met the inclusion criteria. Within these papers, 11 individual measure sets were identified: nine were patient satisfaction scales and two were practice assessment instruments for use by a dentist or practice manager.

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow diagram of literature screening and identification process.

Table 1 summarises the contents of each measure and describes the internal validity and reliability testing of the included measures. Further studies that make use of the measure are described. Satisfaction was assessed in the nine patient satisfaction scales using Likert-style scores. These measures were to be completed by the patient receiving treatment or by their parent/guardian. Similar ordinal rating scales were used by the measures described in the two practice assessment tools. These measures were designed to be completed by a dentist or manager in the dental practice.

Table 1.

Contents of each measure set identified in the peer-reviewed literature outcomes of internal validity and reliability testing of the measure sets identified in the peer-reviewed literature

| Measure set name and abbreviation | Key reference | Further references using measure | Description of measure contents | Items (n) | Type of measure | Internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha α) | Test–retest reliability | Domain | IoM dimensions of quality assessed |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dental Management Survey Brazil (Dimension 6) (DMS-BR) | Gonzales22 | N/A | Self-assessment tool for use by dentists and practice managers to assess the quality of safety and organisational aspects of dental care delivery | 6 | Practice assessment tool | α = 0.632 | Intraclass correlation coefficients = 0.93 and 0.94 | Structure | Safety, efficiency |

| Survey of Organisational Aspects of Dental Care (SOADC) | Goetz23 | N/A | Self-assessment tool of structural elements of the delivery of dental care, with focus on teamwork, leadership and the implementation of change within a practice | 20 | Practice assessment tool | α = 0.775 | Intraclass correlation coefficients = 0.732 | Structure | Safety, patient-centredness |

| Dental patient feedback on consultation skills (DPFCS) | Cheng et al.24 | Wong25 | Patient satisfaction scale on the quality of information provided by the dentist to patients in consultations and the atmosphere of trust generated | 16 | Patient satisfaction survey | α = 0.94 | Intraclass correlation coefficients = 0.89 | Outcome | Patient-centredness |

| Tool Developed from Parasurman and Zalathml Construct of quality | Bahadori26 | N/A | Patient satisfaction scale of the structures and processes of primary dental care. Focus on the settings in which dental care is delivered and communication between dentists and patients | 30 | Patient satisfaction survey | α = 0.71–0.91 | Not reported | Structure, process | Effectiveness, patient-centredness, timeliness, efficiency |

| Burdens in Prosthetic Dentistry Questionnaire (BiPD-Q) | Reissman27 | Hacker28 | Patient satisfaction scale of the perceived burdens of the processes of dental treatment during prosthetic dental procedures | 25 | Patient satisfaction survey | α = 0.87 | Not reported | Process | Patient-centredness |

| Burdens in Oral Surgery Questionnaire (BiOS-Q) | Reissman29 | N/A | Patient satisfaction scale of the perceived burdens of the processes of dental treatment during oral surgical procedures | 16 | Patient satisfaction survey | α = 0.84 | Intraclass correlation coefficients = 0.90 | Process | Patient-centredness |

| Tool after ‘Consensus workshop for selecting essential oral health indicators in Europe’ | Kikwilu30 | N/A | Patient satisfaction scale of the perceived quality of the setting of delivery of dental care and perceptions of treatment quality and communication | 11 | Patient satisfaction survey | α = 0.849 | Spearman rank correlation coefficients = 0.751–0.923 | Outcome | Effectiveness, timeliness |

| Tool developed from Consumer assessment of Healthcare Providers and systems | Keller31 | N/A | Patient satisfaction scale of the perceived quality of information, communication and dental care received by dental plan holders | 23 | Patient satisfaction survey | α = 0.74 | Not reported | Outcome | Timeliness, effectiveness |

| Quality from the Patient’s Perspective Questionnaire | Larrsson32 | Patient satisfaction scale regarding the communication, information given and environment of care deliver | 10 | Patient satisfaction survey | α = 0.83 and 0.84 | Not reported | Outcome | Effectiveness, patient-centredness | |

| Dental Visit Satisfaction Scale (DVSS) | Corah and O’Shea33 | Olausson34 Sun35 Hakeberg36 Stouthard37 |

Patient Satisfaction scale, communication of oral health, rapport with dentist and comfort during treatment | 10 | Patient satisfaction survey | α = 0.92 | Not reported | Outcome | Effectiveness, patient-centredness |

| Dental Satisfaction Questionnaire (DSQ) | Davies and Ware38 | Lee39 Milgrom40 Skaret41 Brennan42 Mascarenhas43 Chapko44 |

Patient satisfaction scale, assessing ease of access, communication and thoroughness of care | 10 | Patient satisfaction survey | α = (from Chapko) = 0.46–0.78 | Not reported | Structure Outcome |

Timeliness, patient-centredness, effectiveness |

All the included measure sets showed face validity. Cronbach’s alpha was used to describe internal validity in all of the measures. All were above the acceptable level of α = 0.721, except the Dental Management Survey Brazil (DMS-BR)22 with α = 0.632 (suggesting questionable internal consistency), and components of the Dental Satisfaction Questionnaire (DSQ)38. The validity of the DSQ is demonstrated by Chapko44; the measurement concept of ‘Cost’ was suggested as unreliable (α = 0.47). All other measures in this set had α > 0.6. Test–retest reliability was reported in five of the measures, using either intraclass correlation coefficients or Spearman rank correlation coefficients, all of which showed acceptable values.

The patient satisfaction scales broadly considered patient satisfaction with the care received. For these measures, satisfaction can be considered as an outcome of care. Where specific questions address the procedural aspects of care, the domain of process is also measured. The Burdens in Prosthetic Dentistry Questionnaire (BiPD-Q) 27 and Burdens in Oral Surgery Questionnaire (BiOS-Q)29 measures were specifically related to satisfaction with processes of care and the procedural elements of prosthetic dentistry and oral surgery. Structure was measured in the practice self-assessment tools [DMS-BR22 and Survey of Organisational Aspects of Dental Care (SOADC)23] and concerned the training of staff and provision of safety equipment and data management. The questionnaire developed by Bahadori et al.26 asked patients to rate the importance of a number of structures and processes within a dental clinic, including the state of facilities and the communication skills exhibited by the dentist.

The practice assessment measures (DMS-BR22, SOADC23) assessed the dimensions of (i) safety, with measures addressing the use and provision of personal protective equipment and (ii) efficacy, using measures of ability of practice members to work as a team. The patient satisfaction surveys covered a range of dimensions, for example: safety – satisfaction with cleanliness of facilities30; effectiveness – satisfaction with treatment received33; patient-centredness – perception of dentist caring about patient32; timeliness – satisfaction with waiting times to see a dentist31; efficiency – patient satisfaction of cost38 and equity – patient perception of dentist acceptance of them as a person33.

Measures from the grey literature

In total, 24 collections of quality measures sets were identified, with a total of 357 individual quality measures contained therein. Table 2 describes the measurement sets qualitatively in terms of what attributes they attempt to measure, evidence of validity testing and categorisation of measures according to domain and IoM dimensions. The majority of measures within these sets (n = 196/357) followed a numerator/denominator format, wherein the patients receiving a treatment process or reporting an outcome were classed as the numerator and a target population was identified as the denominator. These types of quality measure are presented as a percentage. A further 36 measures were patient satisfaction measures using Likert-style ordinal rating scores. The Denplan Excel Quality measures68 contain 122 checklist-style ‘yes/no’ responses. The only measures that described validity or test–retest reliability were those developed by the Dental Quality Alliance49., 50., 51.. These measures have been developed according to the National Quality Forum measure development guidance69.

Table 2.

Qualitative description of measure sets identified from the grey literature summarising evidence of validation, and categorisation of measure sets according to domains and dimensions of quality

| Measurement collection | Items (n) | Description of measure | Domains | Dimensions | Validation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dental Quality and Outcomes Framework45 | 15 | Measures of patient satisfaction of their dental state and dental practice, clinical effectiveness and patient safety | Process, Outcomes | Safety Effectiveness Patient-centredness Timeliness |

Not reported |

| NICE oral health in care home46 | 9 | Measure of the oral health needs of nursing and care home residents and the provision of care | Structure, Process, Outcome | Patient-centredness Effectiveness Equity |

Not reported |

| NICE oral health promotion in the community47 | 15 | Measures of access to health-promotion resources within the community | Structure, Process, Outcome | Patient-centredness Effectiveness Equity |

Not reported |

| Dental Assurance Framework Policy48 | 12 | Claim data-based assessment of provision of fluoride varnish, sealants and radiographs, rate of extractions, endodontics, patient reattendance and patient satisfaction | Process, Outcomes |

Effectiveness Patient-Centredness Timeliness |

Not reported |

| Dental Quality Alliance Adult Measures49 | 3 | Process indicators of the evaluation and ongoing care of patients with periodontitis and provision of topical fluoride in patients with elevated risk | Process | Effectiveness | Face validity gained through consensus of members. Data element and convergent validity testing undertaken |

| Dental Quality Alliance Paediatric measures50 | 12 | Measures of the utilisation of services; provision of sealants, fluoride, prevention, treatment; continuity of care; emergency department visits and follow-up cost | Process, Outcomes | Effectiveness | RAND-UCLA method used to gain consensus of face validity of measure concept. Data element collection validity assessed using Kappa statistics |

| Dental Quality alliance Electronic Paediatric measures51 | 2 | Measures of utilisation of preventive and treatment services | Process | Effectiveness | Face validity gained through consensus of members. Data element and convergent validity testing undertaken |

| Child and adolescent Health Measurement Initiative National Survey of Children’s Health52 | 3 | US national survey. Measures of utilisation of treatment services, preventive services and presence of toothache, bleeding gums, decay and cavities | Process, Outcomes | Effectiveness | Not reported |

| Child and adolescent Health Measurement Initiative National Survey of Children with Special Health Care Needs, 2009/201053 | 2 | US national survey, assessment of need and utilisation of preventive services | Process | Effectiveness | Not reported |

| National Network for Oral Health Access Dental Dashboard54 | 15 | Practice based dashboard to measure caries at recall, risk assessment, provision of sealants, topical fluoride, self-management goal setting and review, completion of treatment plans, recall rates, recommendations, and practice finances | Structure, process and outcome | Effectiveness Efficiency Patient-centredness |

Not reported |

| Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality Patient Experience Measures for the CAHPS® Dental Plan Survey55 | 21 | National patient survey to assess patient’s assessment of care from dentist and staff, access to dental care, dental plan costs and services and patient satisfaction | Outcomes | Patient-centredness Timeliness |

Not reported |

| Australian Council on Healthcare Standards56 | 13 | Measures of use of radiographs in new patients, retreatment rates, extraction of deciduous teeth, complications following extractions | Process, Outcomes | Effectiveness | Not reported |

| California Department of Health Care Services57 | 15 | Measures of the use of preventive services, sealants, fluoride varnish, treatment services, continuity of care | Process | Effectiveness | Not reported |

| Indian Health Service58 | 3 | Measure of receipt of topical fluoride dental sealants and access to oral health care | Process, Structure | Effectiveness | Not reported |

| HRSA HIV/AIDS bureau performance measures59 | 5 | Measures of provision of oral health education, periodontal screening, treatment planning and completion and taking dental and medical history in patients with HIV | Process | Effectiveness | Not reported |

| HRSA Oral Health Quality Improvement initiative60 | 9 | Treatment plan completion, use of services, provision of oral health education, sealants, fluoride, periodontal screening | Process | Effectiveness | Not reported |

| Q-METRIC61 | 1 | Measure of availability of services | Structure | Effectiveness | Not reported |

| CMS-146 Measures62 | 7 | Measures of use of dental services, preventive services, treatment services, sealant | Process | Effectiveness | Not reported |

| MCH Title V National Performance Measure for Oral Health Summary63 | 3 | Measure of percentages of: children with decay/cavities, pregnant women receiving dental care and children receiving preventive dental care | Process | Effectiveness | Not reported |

| Oral Health Disparities Collaborative Pilot Measures64 | 17 | Measures of rates of perinatal and early childhood caries, treatment plan construction and completion, paediatric dental examination and treatment plan. Fluoride varnish application, continuity of care and fluoride assessment | Process | Effectiveness Timeliness |

Not reported |

| Permanente dental associates65 | 32 | Measures of use of fluoride, sealants, clinical incidents, examination rate, continuity of care, specialist care referral, percentage of specialty care completed by general dentist | Process, Outcomes | Effectiveness Patient-centredness Safety Efficiency |

Not reported |

| NCQA 2017 State of Health Care Quality HEDIS measure annual dental visits66 | 1 | Measure of Medicaid members who attended for a dental visit | Process | Effectiveness | Not reported |

| Denplan Excel Patient Survey67 | 12 | Patient-reported outcome measures of satisfaction with their dental health and satisfaction with their dental care provision | Outcomes | Patient-centredness | Not reported |

| Denplan Excel Quality programme68 | 129 | 122 Checklist-style questions, rating of aspects of the structures and processes of dental care delivery against quality standards. Seven percentage measures of process | Structure, Process | Safety Effectiveness Efficiency |

Not reported |

Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems, CAHPS; Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, CMS-146; the Healthcare Effectiveness Data and Information Set, HEDIS; Health Resources & Services Administration, HRSA; Maternal and Child Health, MCH; National Committee for Quality Assurance, NCQA; National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, NICE; Quality Measurement, Evaluation, Testing, Review and Implementation Consortium, Q-METRIC.

Approximately half (48.7%, 174/357) of measures assessed processes of care provision. Common themes for process measures were the provision of fluoride, fissure sealants and annual reviews. There was a high degree of repetition of these concepts across a number of measure sets. A total of 24.4% (87/357) measured outcomes, with patient satisfaction ratings making up 52.9% (46/87) of these outcome measures. The remaining outcome measures included measures of longevity of restorations, rates of complications and new disease presence at recall. In addition, 26.8% (96/357) of the measures assessed structure. Of these 96 measures, 84 (87.5%) were derived from the ‘Denplan Excel’ quality measures, which quantified provision of equipment and staff within practices. The measures predominantly assessed dimensions of effectiveness, patient-centredness, safety and timeliness of treatment. There were few measures of efficiency or equity.

Quality measures gap analysis

The common themes identified in both the peer-reviewed and grey literature measures are compiled in Table 3. This table identifies the broad constituent element of quality that the measure attempts to capture (IoM Dimensions) and the nature of the measure (Donabedian’s Domains). The categorisation of domain refers to whether the measure assesses the structures of dental care delivery, the processes that are undertaken or outcomes that result from the delivery of care. As such, a measure of the provision of a treatment or preventive programme to a population is categorised as a process measure. This analysis shows a proliferation of measures developed for the assessment of process and outcomes within the dimensions of effectiveness and patient-centredness. Outcome measurement is predominantly achieved via patient satisfaction measures. Significant gaps in measures across the domains and dimensions of quality are evident.

Table 3.

Classification of all Peer-Reviewed and Grey Literature measures identified according to dimensions and domains

| Domains |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Structure | Process | Outcome | |

| Dimensions | |||

| Safe | Dentist : Nurse ratio | Recording of medical history | Patient satisfaction with cleanliness of facilities |

| Evidence of staff training/certification | Evidence of incident reporting being carried out | Patient satisfaction with quality improvement initiatives | |

| Evidence of ensuring that suppliers/contractors are certified | Number of serious incidents | ||

| Building set up to allow decontamination away from clinical areas | |||

| Evidence of complaints handling procedures | |||

| Evidence of data protection and handling procedures | |||

| Cleanliness of practice | |||

| Evidence of practice infection-control measures | |||

| Use of single-use equipment where feasible | |||

| Certification of buildings and surgery safety | |||

| Evidence of medical emergency equipment | |||

| Effective | Percentage of patients receiving oral health examination | Patient rating of comfort in daily function | |

| Percentage of patients receiving soft-tissue screening | Patient rating of comfort during visit | ||

| Percentage of patients receiving emergency treatment | Patient rating of ease to eat | ||

| Percentage of patients receiving planned treatment | Patient rating of appearance of teeth | ||

| Percentage of patients receiving preventive advice | Patient rating of comprehensiveness of examination/treatment | ||

| Number of patients having radiographs taken | Patient satisfaction with treatment received | ||

| Percentage of patients receiving dental follow-up after emergency department visit for dental cause | Patient rating of quality of treatment | ||

| Extraction to endodontics ratio | Periodontal health: number of sites with bleeding on probing | ||

| Evidence of caries and periodontal risk assessment being carried out | Caries: number of decayed teeth | ||

| Percentage of patients receiving treatment for caries | Caries: prevalence of early childhood caries | ||

| Prevention: fillings ratio | Caries: new caries at recall of patient | ||

| Number of referrals to medical care | Number of patients who are caries free | ||

| Number of referrals to secondary dental care | Plaque on children’s teeth | ||

| Percentage of patients with a recording of Basic Periodontal Examination | Referral to secondary care for paediatric tooth extraction | ||

| Percentage of patients having comprehensive periodontal examination | Emergency department visits from dental-related cause | ||

| Percentage of patients with history of periodontitis undergoing course of periodontal therapy | Patient-reported oral health-related quality of life | ||

| Percentage of patients with fluoride needs assessment | Proportion of endodontic teeth that required retreatment | ||

| Percentage of patients receiving preventive advice | Proportion of sealants that require retreatment | ||

| Provision of fissure sealants in high-risk groups | Number of deciduous teeth extracted | ||

| Provision of fluoride therapy in high-risk groups | Complications following treatment | ||

| Extractions following endodontics | |||

| Proportion of fillings that subsequently required retreatment/endodontics/extraction | |||

| Longevity of restorations | |||

| Patient-centred | Percentage of patients with named regular dentist | Evidence of assessment of needs | Patient satisfaction with communication – listening to patient concerns |

| Access to hygienist | Development of personalised treatment plans | Patient satisfaction with communication – showing concern | |

| Access to Out of Hours care | Setting self-management goals for patients | Patient satisfaction with communication – explaining treatments | |

| Comfort of dental practice | Time spent with patients | Patient satisfaction with communication – treatment/preventive advice | |

| Aesthetics of dental practice | Percentage of patients seeing same dentist/dental team at consecutive visits | Patient satisfaction with communication – giving appropriate level of information | |

| Ease of payment | Percentage of patients having treatment by their regular dentist | Patient perception of dentist’s acceptance of them as a person | |

| Percentage of patients who are able to see their own dentist for emergency treatment | Patient satisfaction with courtesy and respect of dental team | ||

| Extractions/endodontics completed by patient’s general dentist | Patient satisfaction with time spent with dental team | ||

| Length of treatment sessions (comfort to patient) | Patient satisfaction with helpfulness of staff | ||

| Patient rating of ‘atmosphere’ of dental environment | |||

| Percentage of patients who would recommend to friend | |||

| Patient rating of trust | |||

| Patient satisfaction of dental team’s ability to respond to their needs | |||

| Patient satisfaction with written information | |||

| Patient satisfaction with dentist | |||

| Patient rating of comfort of treatment | |||

| Patient-reported pain | |||

| Patient retention – number of patients who stay with practice over time period | |||

| Timely | Percentage of group of interest who have access to dentist | Timeliness of treatment plan completion | Patient satisfaction with waiting times – to get standard appointment |

| Percentage of group of interest who have access to oral health education | Timeliness of administrative claims | Patient satisfaction with waiting times – to get emergency appointment | |

| Patient satisfaction with waiting times – in surgery | |||

| Proportion of high-risk patients who have been able to access dentist | |||

| Efficient | Generalist: specialist ratio in primary care | Patient satisfaction with cost | |

| Quality of interpersonal relationships between members of dental team | Patient rating of structure of dental appointments | ||

| Dental team satisfaction with their leadership | Percentage of treatment plans completed | ||

| Dental team satisfaction with their ability to make changes | Number of patients failing to attend | ||

| Responsiveness of practice and team to making changes | Percentage of patients reattending within 3 months | ||

| Stress of team members within dental practice | Average cost of treatment per patient | ||

| Use of modern equipment | Number of dental encounters/hour | ||

| Longevity of restorations | |||

| Equity | Evidence of local arrangements to assess health needs | Percentage of group of interest that receive preventive advice/treatment in non-dental setting | Patient perception of dentist’s acceptance of them as a person |

| Local arrangements to identify high needs groups | Patient rating of ease of access | ||

| Local arrangements to ensure access for high-needs groups | |||

| Ease of access – car parking, disabled access | |||

DISCUSSION

This systematic review describes 11 measure collections (167 total measures) from the peer-reviewed literature and 24 measure collections (357 total measures) from the grey literature that may be used to assess quality in primary care dentistry. This study is the first known review of quality measures in primary care dentistry that uses a systematic review design, with the use of a priori inclusion and exclusion criteria.

Despite the structured searching methodology, it is difficult to ensure that a comprehensive list of measures has been captured, particularly those which appear in the grey literature. The pace at which new measures are being developed outside the peer-reviewed literature means that further measures are likely to have been produced since searching was completed. Whilst this search may not include every measure that is available, it does display the major trends of how quality is currently measured and therefore viewed by the dental profession. Only English language sources were used, as the cost associated with the translation of foreign language measures and papers would be prohibitive. This provides a view of quality measurement dominated by developed countries. Quality measures will necessarily reflect the context and the priorities in which care is delivered; measures formulated in the developed world may not be as relevant in less developed communities. FDI called for an international consensus on understanding quality in dentistry2, and the influence of local context and priorities should not be underestimated in working towards this goal.

Using valid and reliable tools to measure quality is vital in order to support day-to-day quality assessment and improvement of dental care. The 11 measure sets from the peer-reviewed literature22., 23., 24., 26., 27., 29., 30., 31., 32., 33., 38. and three measure sets from the grey literature50., 56., 57. represent measures available to researchers to assess dimensions of quality in relation to primary care dentistry. The majority of these measures showed acceptable levels of internal validity; however, their usefulness in delivering a clear picture of quality and to support quality improvement is unclear.

The gap analysis categorised the measures according to the IoM dimensions of quality and identified important areas of care in which specific dental measures were absent. Some of these gaps are possibly populated by measures used successfully in other areas of health care. It could also be the case that the IoM dimensions fail to describe significant elements of quality that are important to dentistry, such as cosmetic care, functional improvement and the discomfort and anxiety associated with dental procedures. Further dimensions described in the literature include tangibility26., 70., responsiveness26., 70., empathy26., 70., accessibility7., 12., coordination and continuity of care12, comprehensiveness12, technical quality5, acceptability71, legitimacy71, optimality71, relevance72, appropriateness11 and ‘caring function’11.

The majority of the measures within the grey literature focussed on processes of care. Core themes of fluoride prescription, provision of fissure sealants and dental attendance were identified from this search. However, without corresponding measures of resulting outcomes, these process measures may have limited utility19. The majority of outcome measures identified in this search assessed patient satisfaction. However, a review of patient satisfaction measures suggests that these are highly affected by disconfirmation and attribution bias and are inherently unreliable73. It has been suggested that the patient’s perception of technical competence is based on the communication and caring nature of the dentist rather than the work they actually carry out33. As the primary stakeholders of primary care dentistry, it is intuitively important that patients are provided with a service that provides satisfaction; however, measures of patient satisfaction give only a limited indication of the overall quality of care provided.

Consideration also needs to be given to the reasons for collecting data on quality; the various stakeholders in primary dental care have different priorities for their use. For example, policy makers may want to use such data to improve equity and access for a defined population. Dentists may wish to use quality measurement to fulfil a personal and professional desire to improve the care for their patients or as a way of marketing themselves or their practice. Patients may wish to use measures to compare the quality of care provided by different dentists. Providers of dental care may wish to use quality data for performance management of their dentists or as a way of remunerating and incentivising their dentists. Linking quality improvement to remuneration runs the risk of inducing unintended behaviour change, leading to alterations in the provision of care74; this may include services de-registering high-risk patients who threaten to lower their quality rating.

The majority of measures currently used within primary care dentistry have been developed by private companies, such as insurers or corporate care providers, and are not published in peer-reviewed journals. Two issues arise from this: first, time and resources are being used in the development of measures that have already been developed elsewhere; and, second, measures are being used without the scrutiny of the wider scientific community. The authors believe that international collaboration is required to develop valid and reliable measures that can be applied across a range of contexts.

CONCLUSIONS

This research has highlighted the lack of valid, reliable measures used to assess quality. Current efforts in producing quality measures are being conducted with little academic grounding, leading to measures of limited validity and utility that fail to capture some key elements of quality. International collaboration is required to agree on a definition of quality and a shared understanding of what quality means for dentistry. Consensus would guide the production of valid, reliable measures within an agreed framework for the benefit of patients.

Acknowledgements

No further acknowledgements are made. No financial support was provided for this project.

Competing interests

The authors have no competing interests to declare.

APPENDIX 1. SEARCH STRATEGY

The Following search strategy was used in MEDLINE:

-

1

exp *”Quality of Health Care”/

-

2

((quality or performance$ or satisf$) adj5 (indicat$ or activit$ or framework$ or tool$ or matrix or matrice$ or measure$ or guideline$ or accreditat$ or indices or index or certificat$ or regulat$ or assur$ or standard$ or control$ or audit$ or metric or improv$ or criteri$ or assess$ or valid$ or scale$ or checklist$)).ti,ab. not (quality adj2 life).mp. [mp=ti, ab, sh, hw, ot, kw, bt, id, cc, ac, de, md, sd, so, pt, an, tn, dm, mf, dv, fx, nm, kf, px, rx, ui, sy]

-

3

1 and 2

-

4

exp Dentists/

-

5

((dentist$ or (dental adj5 practitioner$)) not student$).ti,ab.

-

6

exp Dental auxiliaries/

-

7

((dental and (hygienist$ or therapist$)) not student$).ti,ab.

-

8

(“oral health practitioner” or “dental assistant$” or “dental auxil$” or “dental hygiene practitioner$” or “community dental health co-ordinator$” or “oral health co-ordinator$”).ti,ab.

-

9

4 or 5 or 6 or 7 or 8

-

10

3 and 9

-

11

Remove duplicates from 10

References

- 1.European Regional Organisation of the Fédération Dentaire Internationale. ERO-FDI WG Quality in Dentistry Report 2007-2010. 2010 [cited 03/04/2018]. [Available from: www.erodental.org/ddc/ddid97.]

- 2.FDI World Dental Federation. Quality in Dentistry. 2017 [cited 03/04/2018]. [Available from: http://www.fdiworlddental.org/resources/policy-statements-and-resolutions/quality-in-dentistry.] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 3.Campbell S, Tickle M. What is quality primary dental care? Br Dent J. 2013;215:135–139. doi: 10.1038/sj.bdj.2013.740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Maxwell RJ. Quality assessment in health. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed) 1984;288:1470–1472. doi: 10.1136/bmj.288.6428.1470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Blumenthal D. Part 1: Quality of care–what is it? N Engl J Med. 1996;335:891–894. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199609193351213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Donabedian A. Health Administration Press; Chicago, IL: 1980. The Definition of Quality and Approaches to its Assessment. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Campbell SM, Roland MO, Buetow SA. Defining quality of care. Soc Sci Med. 2000;51:1611–1625. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(00)00057-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Heath I, Rubinstein A, Stange KC, et al. Quality in primary health care: a multidimensional approach to complexity. BMJ. 2009;338:b1242. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b1242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Soni Raleigh V, Foot C. King’s Fund; London: 2010. Getting the Measure of Quality: Opportunities and Challenges. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Royal College of General Practitioners What sort of doctor? J R Coll Gen Pract. 1981;31:698–702. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Caper P. Defining quality in medical care. Health Aff. 1988;7:49–61. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.7.1.49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Health Services Research Group Quality of care: 1. What is quality and how can it be measured? CMAJ. 1992;146:2153–2158. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Institute of Medicine Committee on Quality of Health Care in America . National Academies Press; Washington, DC: 2001. Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tickle M, O’ Malley L, Brocklehurst P, et al. A national survey of the public’s views on quality in dental care. Br Dent J. 2015;219:E1. doi: 10.1038/sj.bdj.2015.595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Poorterman JH, Van Weert CM, Eijkman MA. Quality assurance in dentistry: the Dutch approach. Int J Qual Health Care. 1998;10:345–350. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/10.4.345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mills I, Batchelor P. Quality indicators: the rationale behind their use in NHS dentistry. Br Dent J. 2011;211:11–15. doi: 10.1038/sj.bdj.2011.521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.National Quality Forum . National Quality Forum; Washington, DC: 2012. Oral Health Performance Measurement: Environmental Scan, Gap Analysis & Measure Topics Prioritization. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Institute of Medicine and National Research Council Committee on Oral Health Access to Services . National Academies Press; Washington, DC: 2011. Improving Access to Oral Health Care for Vulnerable and Underserved Populations. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bader JD. Challenges in quality assessment of dental care. J Am Dent Assoc. 2009;140:1456–1464. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.2009.0084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.OpenGrey [Internet] [cited 29/03/2018]. [Available from: http://www.opengrey.eu.]

- 21.DeVellis R. Sage; Thousand Oaks, CA: 2003. Scale Development: Theory and Applications. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gonzales PS, Martins IEF, Biazevic MG, et al. Dental Management Survey Brazil (DMS-BR): creation and validation of a management instrument. Braz Oral Res. 2017;31:e26. doi: 10.1590/1807-3107BOR-2017.vol31.0026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Goetz K, Hasse P, Szecsenyi J, et al. Questionnaire for measuring organisational attributes in dental-care practices: psychometric properties and test-retest reliability. Int Dent J. 2016;66:93–98. doi: 10.1111/idj.12209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cheng BS, McGrath C, Bridges SM, et al. Development and evaluation of a Dental Patient Feedback on Consultation skills (DPFC) measure to enhance communication. Community Dent Health. 2015;32:226–230. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wong HM, Bridges SM, McGrath CP, et al. Impact of prominent themes in clinician-patient conversations on caregiver’s perceived quality of communication with paediatric dental visits. PLoS ONE. 2017;12:e0169059. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0169059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bahadori M, Raadabadi M, Ravangard R, et al. Factors affecting dental service quality. Int J Health Care Qual Assur. 2015;28:678–689. doi: 10.1108/IJHCQA-12-2014-0112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Reissmann DR, Hacker T, Farhan D, et al. The Burdens in Prosthetic Dentistry Questionnaire (BiPD-Q): development and validation of a patient-based measure for process-related quality of care in prosthetic dentistry. Int J Prosthodont. 2013;26:250–259. doi: 10.11607/ijp.3266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hacker T, Heydecke G, Reissmann DR. Impact of procedures during prosthodontic treatment on patients’ perceived burdens. J Dent. 2015;43:51–57. doi: 10.1016/j.jdent.2014.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Reissmann DR, Semmusch J, Farhan D, et al. Development and validation of the Burdens in Oral Surgery Questionnaire (BiOS-Q) J Oral Rehabil. 2013;40:780–787. doi: 10.1111/joor.12092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kikwilu EN, Kahabuka FK, Masalu JR, et al. Satisfaction with urgent oral care among adult Tanzanians. J Oral Sci. 2009;51:47–54. doi: 10.2334/josnusd.51.47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Keller S, Martin CGC, Evensen CT, et al. The development and testing of a survey instrument for benchmarking dental plan performance using insured patients’ experiences as a gauge of dental care quality. J Am Dent Assoc. 2009;140:229–237. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.2009.0137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Larsson BW, Bergstrom K. Adolescents’ perception of the quality of orthodontic treatment. Scand J Caring Sci. 2005;19:95–101. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-6712.2005.00325.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Corah NL, O’Shea RM, Pace LF, et al. Development of a patient measure of satisfaction with the dentist: the Dental Visit Satisfaction Scale. J Behav Med. 1984;7:367–373. doi: 10.1007/BF00845270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Olausson M, Esfahani N, Ostlin J, et al. Native-born versus foreign-born patients’ perception of communication and care in Swedish dental service. Swed Dent J. 2016;40:91–100. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sun N, Burnside G, Harris R. Patient satisfaction with care by dental therapists. Br Dent J. 2010;208:E9. doi: 10.1038/sj.bdj.2010.209. discussion 212–213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hakeberg M, Heidari E, Norinder M, et al. A Swedish version of the Dental Visit Satisfaction Scale. Acta Odontol Scand. 2000;58:19–24. doi: 10.1080/000163500429389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Stouthard ME, Hartman CA, Hoogstraten J. Development of a Dutch version of the Dental Visit Satisfaction Scale. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 1992;20:351–353. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0528.1992.tb00697.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Davies AR, Ware JE., Jr Measuring patient satisfaction with dental care. Soc Sci Med A. 1981;15:751–760. doi: 10.1016/0271-7123(81)90019-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lee CT, Zhang S, Leung YY, et al. Patients’ satisfaction and prevalence of complications on surgical extraction of third molar. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2015;9:257–263. doi: 10.2147/PPA.S76236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Milgrom P, Spiekerman C, Grembowski D. Dissatisfaction with dental care among mothers of Medicaid-enrolled children. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2008;36:451–458. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0528.2007.00423.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Skaret E, Berg E, Raadal M, et al. Reliability and validity of the Dental Satisfaction Questionnaire in a population of 23-year-olds in Norway. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2004;32:25–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0528.2004.00118.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Brennan DS, Gaughwin A, Spencer AJ. Differences in dimensions of satisfaction with private and public dental care among children. Int Dent J. 2001;51:77–82. doi: 10.1002/j.1875-595x.2001.tb00826.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mascarenhas AK. Patient satisfaction with the comprehensive care model of dental care delivery. J Dent Educ. 2001;65:1266–1271. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chapko MK, Bergner M, Green K, et al. Development and validation of a measure of dental patient satisfaction. Med Care. 1985;23:39–49. doi: 10.1097/00005650-198501000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Department of Health . Department of Health; London, UK: 2016. Dental Quality and Outcomes Framework. [Google Scholar]

- 46.National Institute for Health and care Excellence . National Institute for Health and care Excellence; London: 2017. Oral Health in Care Homes: Quality standard. [Google Scholar]

- 47.National Institute for Health and Care Excellence . National Institute for Health and Care Excellence; London: 2016. Oral Health Promotion in the Community: Quality Standard. [Google Scholar]

- 48.NHS England. Dental Assurance Framework; [2014 cited 03/04/2018]. [Available from: https://www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2014/05/dental-assurance-frmwrk-may.pdf]

- 49.Dental Quality Alliance User Guide for Adult Measures Calculated using administrative Claims data. 2018 [cited 03/04/2018]. [Available from: https://www.ada.org/~/media/ADA/Science%20and%20Research/Files/DQA_2018_Adult_Measures_User_Guide.pdf?la=en.]

- 50.Dental Quality Alliance. User Guide for Pediatric Measures Calculated Using Administrative Claims Data 2018 [cited 03/04/2018]. [Available from: https://www.ada.org/~/media/ADA/Science%20and%20Research/Files/DQA_2018_Pediatric_%20Measures_User_Guide.pdf?la=en.]

- 51.Dental Quality Alliance. Electronic Pediatric Measures. 2016. [cited 03/04/2018]. [Available from: https://www.ada.org/en/science-research/dental-quality-alliance/dqa-measure-activities/electronic-pediatric-measures.]

- 52.The Child and Adolescent Health Measurement Initiative. Guide to Topics & Questions Asked: National Survey of Children’s Health. 2016 [cited 03/04/2018]. [Available from: http://childhealthdata.org/learn/NSCH/topics_questions/2016-nsch-guide-to-topics-and-questions.]

- 53.The Child and Adolescent Health Measurement Inititiative. Guide to Topics & Questions Asked: National Survey of Children with Special Health Care Needs, 2009/2010. 2010 [cited 05/04/2018]. [Available from: http://childhealthdata.org/learn/NS-CSHCN/topics_questions/3.3.0-2009-10-national-survey-of-cshcn--topics-questions.]

- 54.National Network for Oral Health Access. The Dental Dashboard. 2015 [cited 03/04/2018]. [Available from: http://www.nnoha.org/resources/dental-dashboard-information/.]

- 55.Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Patient Experience Measures for the CAHPS® Dental Plan Survey Rockville, MD. 2011 [cited 03/04/2018]. [Available from: https://www.ahrq.gov/cahps/surveys-guidance/dental/about/survey-measures.html.]

- 56.Australian Council on Healthcare Standards . 18th ed. Australia; Sydney: 2017. Australasian Clinical Indicator Report. [Google Scholar]

- 57.California Department of Health Care Services. FFS Performance Measures California. 2018 [cited 03/04/2018]. [Available from: http://www.dhcs.ca.gov/services/Pages/FFSPerformanceMeasures.aspx.]

- 58.Indian Health Service. GPRA/GPRAMA resource guide. 2013 [cited 03/04/2018]. [Available from: https://www.ihs.gov/california/tasks/sites/default/assets/File/GPRA/GPRAResourceGuide_v2.pdf.]

- 59.Health Resources & Services Administration. HIV/AIDS Bureau Performance measures. 2017 [cited 03/04/2018]. [Available from: https://hab.hrsa.gov/sites/default/files/hab/clinical-quality-management/oralhealthmeasures.pdf.]

- 60.Anderson JR, editor. HRSA’s Oral Health Quality Improvement Initiative. National Oral Health Conference; 2010; St Louis, MO. Conference Presentation [cited 03/04/2018]. [Available from: http://www.nationaloralhealthconference.com/docs/presentations/2010/Jay%20Anderson%20-%20Improving%20Oral%20Healthcare%20in%20Safety%20Net%20Setti.pdf.]

- 61.National Quality Measures Clearinghouse . Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ); Rockville, MD: 2015. Availability of services: the number of dental providers who have provided any dental procedure to at least one child, per 1,000 eligible children. [cited 03/04/2018]. [Available from: https://www.qualitymeasures.ahrq.gov/summaries/summary/49899/availability-of-services-the-number-of-dental-providers-who-have-provided-any-dental-procedure-to-at-least-one-child-per-1000-eligible-children?q=dental.] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Medicaid. 2700.4 Instructions for Completing Form CMS-416: Annual Early and Periodic Screening, Diagnostic, and Treatment (EPSDT) Participation Report 2017 [cited 03/04/2018]. [Available from: https://www.medicaid.gov/medicaid/benefits/downloads/cms-416-instructions.pdf.]

- 63.Association of State & Territorial Dental Directors. MCH Title V National Performance Measure for Oral Health Details and Recommended Actions. Reno; 2015 [cited 03/04/2018]. [Available from: http://www.astdd.org/docs/mch-npm-combined-summary-and-detailed-overview-03-20-2015.pdf.]

- 64.The Health Resources and Services Administration’s Health Disparities Collaborative. Oral Health Disparities Collaborative Implementation Manual 2012 [cited 03/04/2018]. [Available from: http://www.nnoha.org/nnoha-content/uploads/2013/09/OHDC-Implementation-Manual-with-References.pdf.]

- 65.Snyder J. Quality Measurement Models 2015 [cited 03/04/2018]. [Available from: http://www.ada.org/en/science-research/dental-quality-alliance/2015-dqa-conference.]

- 66.National Care Quality Alliance. Annual Dental Visits 2017 [cited 03/04/2018]. [Available from: http://www.ncqa.org/report-cards/health-plans/state-of-health-care-quality/2017-table-of-contents/dental.]

- 67.Denplan. Denplan Excel Patient Survey 2016 [cited 03/04/2018]. [Available from: https://www.hilltondentistry.co.uk/pdfs/excel-patient-survey-questionnaire.pdf.]

- 68.Denplan. Excel Practice Assessment Survey. 2016

- 69.Dental Quality Alliance . American Dental Association; Chicago, IL: 2016. Procedure Manual for Performance Measures Development and Maintenance. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Parasuraman A, Zeithaml VA, Berry LL. A conceptual-model of service quality and its implications for future-research. J Mark. 1985;49:41–50. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Donabedian A. The seven pillars of quality. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 1990;114:1115–1118. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Maxwell RJ. Dimensions of quality revisited: from thought to action. Qual Health Care. 1992;1:171–177. doi: 10.1136/qshc.1.3.171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Newsome PR, Wright GH. A review of patient satisfaction: 1. Concepts of satisfaction. Br Dent J. 1999;186:161–165. doi: 10.1038/sj.bdj.4800052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Brocklehurst P, Price J, Glenny AM, et al. The effect of different methods of remuneration on the behaviour of primary care dentists. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;11:CD009853. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD009853.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]