Abstract

Purpose: Non-invasive treatment of root caries lesions (RCLs) may impact oral health-related quality of life (OHRQoL), but no evidence is available. The purpose of the study was to assess changes in OHRQoL among patients exposed to non-invasive treatment of RCLs with conventional or high-fluoride dentifrices. Methods: To be eligible, subjects had to be ≥60 years of age, independently living, with at least five teeth and one RCL. The 14-item Oral Health Impact Profile for adults in Spanish (OHIP-14Sp), oral examination and sociodemographic data were documented at the beginning of the study (T0). The presence and activity of RCLs were detected and diagnosed. Subjects were randomly assigned to either the control (1,450 ppm fluoride) or the experimental (5,000 ppm fluoride) treatment group. A new set of measurements was obtained at 12 months (T1). Mean comparisons were carried out using the Student’s t-test for total OHIP-14Sp scores. To determine whether T1 OHRQoL scores were different regarding sex, age, educational level and socio-economic status, mean OHIP-14Sp scores were obtained and compared with those variables at 12 months. Results: An overall improvement in OHRQoL after the non-invasive treatment of RCLs was verified when T1 was compared with T0 (P < 0.0001). Regarding treatment type, no significant differences were detected between groups (P = 0.114). Subjects with higher income and more years of formal education had better OHRQoL than those with a lower salary (P < 0.0001) and with fewer years of education (P = 0.0006). Conclusions: Non-invasive treatment for RCLs in community-dwelling elders appears to cause a positive impact on OHRQoL. Better OHRQoL was associated with higher socio-economic status and educational level. No significant differences were detected regarding the fluoride concentration in the dentifrices.

Key words: Quality of life, oral health-related quality of life, oral health, OHIP, root caries lesions, dental caries, fluoridated toothpaste, high-fluoride dentifrices, non-invasive treatment, elderly

INTRODUCTION

The world is facing an unprecedented demographic transition. In addition to living longer, people are retaining more teeth1., 2.. Having more teeth retained into older age has resulted in increased prevalence of the most frequent oral diseases: periodontal diseases and dental caries. Regarding dental caries, older adults are usually affected by root caries lesions (RCLs), with a worldwide prevalence of approximately 30–60%3. RCLs usually affect older adults with predisposing risk factors, including high root-caries experience, advanced age, smoking and medication use with resulting xerostomia, among many others that have been identified4. In this scenario, understanding the disease and its consequences is important. Restoration of RCLs is challenging, as restorative procedures are associated with difficulties in moisture control, the nature of the tissues for adhesion and the lack of retention in deeper root cavities. Furthermore, a growing number of patients with RCLs experience limited mobility, which means restrictions to traditional and appropriate restorative treatment5. On the other hand, dental anxiety or dental fear is reported for about 36% of the population, including 12% describing extreme dental fear6. Dental anxiety can have serious implications for a subject’s oral health, by acting as a barrier to dental care7. High dental anxiety has been associated with low oral health-related quality of life (OHRQoL)8., 9.. Conversely, when people attend routine dental visits a protective effect on OHRQoL10 has been found.

Considering the drawbacks of conventional therapy for RCLs, non-invasive treatment of these lesions is highly desirable for patients and clinicians and may impact OHRQoL. Several approaches to prevent initiation of, or to inactivate, RCLs have been proposed. A recent systematic review of the literature identified different types of applications and agents to reduce the initiation of, or to inactivate, RCLs11. Daily use of dentifrice containing 5,000 ppm fluoride showed greater efficacy in reducing active RCLs than dentifrices containing 1,100–1,450 ppm fluoride. We carried out a comprehensive search for the potential association between non-invasive therapies for RCLs and OHRQoL in older people, but no evidence seems to be available. The purpose of the present study, therefore, was to assess changes in self-reported OHRQoL among older patients exposed to non-invasive treatment of RCLs using high-fluoride toothpastes over a period of 1 year. This study is part of a randomised controlled clinical trial designed to evaluate arrest of RCL using non-invasive therapies with fluoridated dentifrices.

METHODS

Subjects

This longitudinal study was conducted among Chilean community-dwelling older adults who participated in a randomised controlled clinical trial of self-administered non-invasive therapy with high-fluoride dentifrices on preventing and arresting RCLs. The study protocol for this trial was registered at ClinicalTrials.gov NCT02647203. Data were collected from July 4, 2014 to December 18, 2015 in the School of Dentistry of the University of Talca. To be enrolled in the primary study, participants had to meet the following inclusion criteria: to be 60 years of age or older; independently living according to the Functional Evaluation of Older Adults (EFAM; its abbreviation in Spanish) criteria12; have at least five teeth and at least one RCL; and be able to answer the 14-item Oral Health Impact Profile for adults in Spanish (OHIP-14Sp) questionnaire13. Participants were excluded from the study if they showed signs of cognitive impairment or alcoholism, which were corroborated by the principal investigator. If there was no clarity on the exclusion criteria, the Short Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE-SF)14 and the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT-C Test)15 were applied.

Sample size was calculated using the software GRANMO, for the comparison of two means (presence of carious lesions) in independent populations, considering a previous study16. Accepting an alpha risk of 0.05 and a beta risk of 0.2 in a two-sided test, a total of 342 participants was required (n = 171 per group). A difference of ≥ 4 units was needed to consider the differences as statistically significant. The common standard deviation was assumed to be 11.79. When designing the study, an anticipated drop-out rate of 20% was established to calculate the sample size. Hence, a sample of 274 older adults was necessary. The study and the informed consent form were approved by the Bioethics Committee of the University of Talca (number: 2013-047). All participants signed an informed consent form and received oral explanation about the nature of the study.

Questionnaire

The instrument for the present investigation (OHIP-14Sp) was the Chilean validation13 of the OHIP-14 questionnaire developed by Slade and Spencer17. Items were grouped into seven domains and respondents were invited to answer the OHIP-14Sp questions on frequency of the problems. The responses were recorded using a 5-point Likert scale (0, never; 1, hardly ever; 2, occasionally; 3, fairly often; and 4, very often) using the original tool proposed by Slade and Spencer, based on the assumptions made by Locker et al.18., 19., 20. Questions were read out loud, one by one, by two trained dentists, making sure that the subjects clearly understood each question. A printed chart with a Likert-type scale, with clear and large characters, was used to show each oral question graphically, so the participants would have a visual reference to facilitate the answers. This ordinal scale is considered as a valid response scale for this type of survey21. Once all the questions were answered, the researchers filled in the questionnaire. This strategy was devised because of the high prevalence of elderly Chileans with low educational levels and high rate of visual problems. Scores were calculated using the additive method, considering values ranging between 0 and 56, which has demonstrated a high discriminatory ability22., 23., 24.. The final score was calculated by the sum of fairly often/very often responses, and occasionally/fairly often/very often responses. Thus, the total score ranged from 0 to 14, with higher scores indicating poorer OHRQoL13., 25..

Data collection

The OHIP-14Sp questionnaire was completed before starting the self-administered non-invasive therapy with fluoridated dentifrices at baseline (T0). Subsequently, all participants received one session of supragingival prophylaxis every 6 months. Oral examination and sociodemographic data of the participants were documented at the start of the study. RCLs were detected and diagnosed according to the International Caries Detection and Assessement System (ICDAS) II criteria for presence26 and according to Nyvad’s criteria for caries activity27., 28.. Baseline and follow-up clinical examinations were performed by one calibrated examiner (intra-examiner Kappa = 0.81). Subjects were interviewed to fill out a sociodemographic survey that included sex, age, socio-economic status and educational level. Once the evaluations were complete, each patient was provided with an oral hygiene kit, consisting of a toothbrush and toothpaste (either of high or low fluoride concentration, depending on the study arm to which the patient was randomly assigned for the clinical trial). The same protocol was applied again 12 months after starting treatment (T1). The protocol for the clinical trial of self-administered non-invasive therapies with fluoridated dentifrices included instructions for brushing twice a day, after breakfast and just before bedtime29, with the toothpaste containing 5,000 ppm fluoride as NaF (Duraphat® 5,000 Plus; Colgate-Palmolive, Therwill, Switzerland) or the toothpaste containing 1,450 ppm fluoride as NaF (Colgate Total®; Colgate-Palmolive, San José Iturbide, Mexico), without post-brushing water rinsing30 and only spitting out the excess toothpaste. A pea-sized amount of toothpaste (about 0.25 g) had to be used at each brushing. The correct dose of toothpaste was demonstrated to each participant. The toothpaste tubes were blinded with tape and both the patients and the study’s principal investigator were blinded to the type of treatment each participant received for the entire duration of the study. Subjects were instructed to replace, every 3 months, the toothbrushes (soft bristles) provided with a new toothbrush (Super 7 Soft, PHB®; Dentaid®, Cerdanyola, Spain), which was also provided by the researchers. At each toothbrush change, the protocol was reinforced to the participants to maximise compliance. Patients received the same material every 3 months (toothbrushes and fluoridated dentifrices).

Ethical considerations

The study was approved by the Bioethics Committee of the University of Talca (number: 2013-047). Procedures performed on human subjects followed the ethical standards of the Institutional and National Research Committee and the Helsinki Declaration of 1964 and its later amendments. Informed consent was signed by all participants in the study.

Data analysis

Mean comparisons were calculated using the Student’s t-test for total OHIP-14Sp scores at T0 and T1. To determine whether the T1 OHRQoL scores of subjects undergoing non-invasive therapies for RCLs were different regarding sex, age, educational level and socio-economic status, mean OHIP-14Sp scores obtained at the 12-month time-point were analysed for each of those sociodemographic variables. The Student’s t-test and ANOVA for educational level were used to estimate the differences, with a significance level of 0.05. Statistical analyses were performed using the statistical software R v3.2.2 (The R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria).

RESULTS

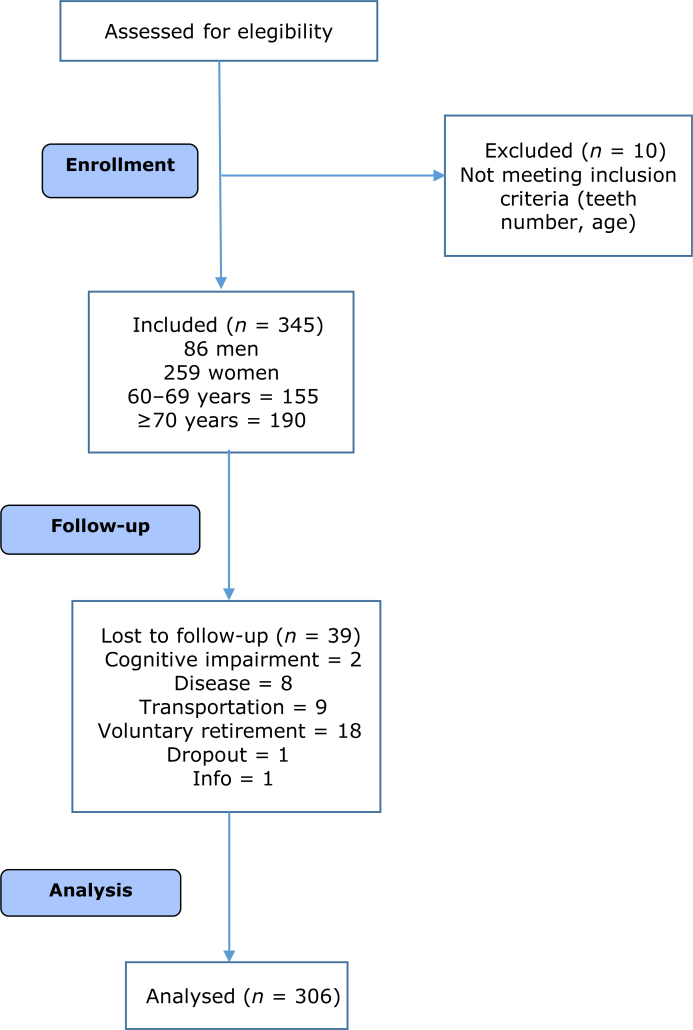

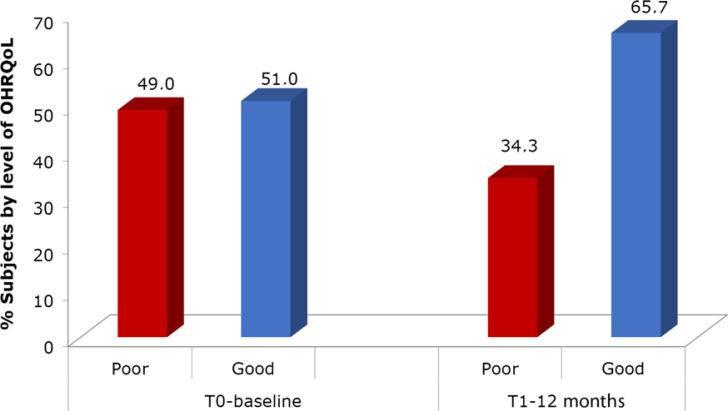

The OHIP-14Sp test was applied to 345 older adults at baseline (T0), before the start of the self-administered non-invasive therapy with fluoridated dentifrices. The second questionnaire (T1) was completed by 306 subjects. Of these 306 subjects, 75% were female and 25% were male, with mean age ± standard deviation (SD) of 69.63 ± 6.25 years. After 1 year, 39 individuals were lost to follow-up for different reasons (Figure 1). Sociodemographic variables are presented in Table 1. OHRQoL assessed at T0 showed that 51% of the subjects had a score lower than 14, which was considered as good OHRQoL. At T1 there was an overall increase, to 65.7%, in subjects with an OHRQoL score of lower than 14. Moreover, a reduction, from 49% at T0 to 34.3% at T1, was observed for subjects who self-reported poor OHRQoL (Figure 2). Mean comparison between OHIP-14Sp scores obtained at T0 and T1, regardless of the type of intervention received, showed significant differences between both scores (Student’s t-test, P <0.0001), with an overall improvement in OHRQoL after non-invasive treatment for RCLs (Table 2). When the variation in OHRQoL was analysed, according to the type of fluoridated dentifrice used, at T1, no significant differences were detected (Student’s t-test, P = 0.114).

Figure 1.

Flow diagram.

Table 1.

Sociodemographic characteristics of the study population of older adults

| Variable | n | % |

|---|---|---|

| Sex | ||

| Women | 231 | 75.5 |

| Men | 75 | 24.5 |

| Age (years) | ||

| 60–69 | 162 | 52.9 |

| ≥70 | 144 | 47.1 |

| Educational level (years) | ||

| >12 | 118 | 38.6 |

| 9–12 | 109 | 35.6 |

| ≤8 | 79 | 25.8 |

| Socio-economic status | ||

| Upper | 201 | 65.7 |

| Middle or lower | 105 | 34.3 |

Figure 2.

Changes in oral health-related quality of life (OHRQoL) after the 12-month follow-up (i.e. T1). Bars represent percentage of participants with poor (red) or good (blue) OHRQoL, according to a predetermined cut-off point.

Table 2.

Means comparison for the total 14-item Oral Health Impact Profile for adults in Spain (OHIP-14Sp) score at baseline (T0) and after 12 months of treatment (T1) of the study population of older adults

| OHRQoL (OHIP-14Sp) | Mean | SD | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| T0 | 15.85 | 9.9 | <0.0001 (T) |

| T1 | 12.22 | 9.3 |

OHRQoL, oral health-related quality of life; SD, standard deviation; T, Student’s t-test.

When exploring the influence of sociodemographic variables on OHRQoL at T1, significant differences were found between subjects with higher and lower socio-economic status (Student’s t-test, P <0.0001). Subjects with higher socio-economic status had lower OHIP-14Sp scores, indicating better OHRQoL than those with lower socio-economic status. Significant differences between OHIP-14Sp scores were detected for educational level (ANOVA, P = 0.0006). Participants with a low educational level, represented as ≤8 years of formal education, had higher OHIP-14Sp scores, indicating poor OHRQoL. No significant differences were observed for sex or age (Table 3).

Table 3.

Means comparison for the total 14-item Oral Health Impact Profile for adults in Spain (OHIP-14Sp) score for sociodemographic variables at the 12-month study time point (T1) of the non-invasive treatment for root caries lesions (RCLs)

| Sociodemographic variables | Mean | SD | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | |||

| Woman (n = 231) | 12.77 | 9.76 | 0.068 (T) |

| Man (n = 75) | 10.51 | 7.66 | |

| Age (years) | |||

| 60–69 (n = 162) | 12.66 | 9.65 | 0.378 (T) |

| ≥70 (n = 164) | 11.72 | 9.83 | |

| Socio-economic status | |||

| Upper (n = 201) | 10.44 | 8.28 | <0.0001 (T)* |

| Middle or lower (n = 105) | 15.61 | 10.29 | |

| Educational level (years) | |||

| >12 (n = 118) | 10.20 | 8.0001 | 0.0006 (A)* |

| 9–12 (n = 109) | 12.12 | 8.89 | |

| ≤8 (n = 79) | 15.35 | 10.92 | |

A, ANOVA/Tukey; SD, standard deviation; T, Student’s t-test.

P < 0.05.

DISCUSSION

Despite the improvement in OHRQoL after 1 year of non-invasive therapy with fluoridated dentifrices for RCLs, the results might be explained by multiple factors involved in the same intervention besides the use of the dentifrice. Indeed, no differences were detected between the experimental arms of the randomised controlled trial for RCLs. The original hypothesis was that higher concentrations of fluoride would decrease dentin hypersensitivity and the progression of RCLs, resulting in better OHRQoL. The results, however, failed to show differences between treatments, but did show an overall improvement in OHRQoL, regardless of the type of treatment. Hence, the search for an explanation of the results in OHRQoL must focus on other intervening factors. The prophylaxis performed on all the participants every 6 months could result in lower self-perceived halitosis, as such procedures have been shown to reduce the amounts of volatile sulphur compounds in patients with periodontitis31. Periodontal diseases may compromise OHRQoL. In fact, most studies have shown a negative impact of periodontitis on OHRQoL32. Furthermore, halitosis is part of one of the OHIP-14Sp dimensions, so its reduction may impact the overall questionnaire score and be interpreted as good OHRQoL. Similarly, supragingival prophylaxis every 6 months could have improved the periodontal condition, affecting oral health perception. Although several clinical studies have been conducted to assess the impact of periodontitis on OHRQoL, comparing and synthesising those findings is difficult as a result of the lack of clarity on an operational definition of the periodontal status and OHRQoL13., 33., 34., 35., 36., 37., 38. and the high heterogeneity of methods and reporting in the studies. It is therefore important to adjust for confounding factors, particularly any of the multiple clinical conditions that may impact people’s lives, consequently avoiding data misinterpretation or spurious associations32. Thus, preventive dental care received periodically during the intervention may lead to better OHRQoL. As a matter of fact, it has been shown that positive health-related behaviour and regular dental check-ups have a protective effect on OHRQoL and are associated with better dental status10., 39.. Furthermore, older adults who reported brushing once a day or less and who had fewer natural teeth also reported lower OHRQoL40 compared with those who brushed at least twice per day.

On the other hand, the Hawthorne effect could be another explanation for our results. This effect is recognised as a reaction of subjects to the realisation that they are in a study under observation41. The Hawthorne effect corresponds to any unexplained result in an experiment carried out on human subjects, on the assumption that the results occurred because of the mere presence of the subjects in the experiment. Thus, volunteers in a study have experiences or signs that otherwise would not have appeared had they not participated in the research42. The Hawthorne effect has been described to alter subject behaviours, which may account for the improvement in some of the outcome variables43., 44., 45., 46.. The Hawthorne effect, however, could be experienced by a limited amount of time, usually not exceeding 6 months45. Thus, based on the latter, we believe that this artifact can be ruled out in our study and the impact of the non-invasive therapy could be explained by a direct effect of the treatment, including a positive dental experience, as discussed below. Additionally, the non-invasive intervention applied here could have impacted dentin hypersensitivity, which is also one of the dimensions of the OHIP-14Sp. Fluoridated toothpastes containing 5,000 ppm fluoride may help to reduce, to some degree, the symptoms of dentin hypersensitivity associated with non-carious lesions and active RCLs47.

Another variable associated with a self-administered treatment is dental fear, which is likely to induce treatment delays, leading to more severe dental issues and/or symptomatic dental attendances. People with dental fear are usually afraid of visiting a dentist, and it has been reported that they have more missing teeth than people with lower or no dental fear48. A study from our group showed that older adults who self-reported dental fear were less likely to have visited a dentist than those who did not self-report dental fear49. As participants in our study experienced a relaxing clinical environment, without the use of a high-speed drill or any other invasive procedure, results in terms of perceived OHRQoL could also have been influenced by the absence of dental fear and high compliance.

The effect, on OHRQoL, of the interpersonal relationship between dentist and patient is an underexplored research area. Although few OHRQoL studies have examined into patient–provider dynamics50, studies from other fields have reported positive experiences in terms of patient communication, trust, empathy and respect, influencing health outcomes and therefore quality of life51. Unmet physical health-needs negatively affect quality of life52. This is likely to be similar in dental health. In our study, participants were periodically examined and listened to, so their positive OHRQoL may have derived from a better rapport. Trust in dental service providers could also have been particularly important for elders, typically less prone to engage in shared decisions with professionals, unlike younger adults. It has been shown that older people’s increased trust in physicians leads to a more compliant and deferential role53. Therefore, trust and confidence in dental professionals may ease stress and reduce hesitation during dental treatment. If lack of trust in a dentist is added to the unmet dental needs, dental anxiety, a factor known to be associated with poor OHRQoL, may be greatly increased54.

When analysing sociodemographic variables, significant differences were found between subjects with a high income compared with those with a low income, in that the former had a better OHRQoL. In our study, we intentionally chose to work with participants from clubs. People of higher socioeconomic status tend to participate more in clubs, as they do not have to work after retirement. A further benefit is that working with organised groups facilitates compliance and follow-up55. Furthermore, people of higher socioeconomic status usually retain more teeth. The same situation was observed regarding educational level. Subjects with ≤8 years of education had higher OHIP-14Sp scores, denoting worse OHRQoL, than subjects with >8 years of education. Demographic and socio-economic characteristics added to oral health status may have an impact on OHRQoL in older adults56., 57.. It has been reported that there is a gradient between social position and OHRQoL in elderly adults56., 57., 58.. Moreover, sociodemographic variables, including race, transport constraints, education and income, have been associated with OHRQoL59., 60.. It has been shown that poverty directly predicts poorer dental health, which leads to worse OHRQoL. Therefore, socio-economic inequalities are an important determinant of OHRQoL61. General oral disease in people from lower socio-economic status over a lifetime may explain the OHRQoL results. Our results agree with previous studies showing the relationship between socio-economic indicators and poor oral health in older people57., 58., 62., 63.. Regarding sex and age, there were no statistically significant differences in the perceived OHRQoL. The study had a greater proportion of women, like many other international studies64., 65.. Subjects were recruited from community clubs for older adults, which have a predominantly female participation, like other social organisations in Chile66. Yet, no statistically significant differences were found in OHRQoL between male and female older adults.

Subjectivity of the OHRQoL construct encourages the deepening of these findings through a qualitative approach. As discussed above, many variables may have intervened in explaining changes in OHRQoL. Thus, a deeper analysis of each is suggested. Although we decided to conduct the randomised controlled trial with both arms using non-invasive therapies for RCLs, it would be of interest to compare the effect, on OHRQoL, of a non-invasive treatment with a conventional treatment. Given the results of this study, non-invasive therapies for RCLs in community-dwelling older people seem an attractive option for many reasons.

CONCLUSIONS

Non-invasive treatment for RCLs in community-dwelling elders appears to impact positively on OHRQoL. Better oral health perception was associated with higher socio-economic status and educational level. No significant differences were detected regarding the fluoride concentration in the dentifrices. A deeper understanding of the reasons why this type of therapeutic approach may affect quality of life is strongly suggested and deserves further research.

Acknowledgements

Authors appreciate the collaboration of Francisca Araya-Bustos, research manager of the study.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Funding

This study was funded by the Interdisciplinary Excellence Research Program on Healthy Aging of the University of Talca and the Chilean Government Grant FONDECYT 1140623 to RAG.

References

- 1.Kinsella K, He W. U.S. Government Printing Office; Washington, DC: 2009. An Aging World: 2008. U.S. Census Bureau, International Population Reports P95/09-1. Available at: https://www.census.gov/prod/2009pubs/p95-09-1.pdf. Accessed 14 February 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Batchelor P. The changing epidemiology of oral diseases in the elderly, their growing importance for care and how they can be managed. Age Ageing. 2015;44:1064–1070. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afv148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Griffin SO, Griffin PM, Swann JL, et al. Estimating rates of new root caries in older adults. J Dent Res. 2004;83:634–638. doi: 10.1177/154405910408300810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ritter AV, Shugars DA, Bader JD. Root caries risk indicators: a systematic review of risk models. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2010;38:383–397. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0528.2010.00551.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lo EC, Luo Y, Tan HP, et al. ART and conventional root restorations in elders after 12 months. J Dent Res. 2006;85:929–932. doi: 10.1177/154405910608501011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hill KB, Chadwick B, Freeman R, et al. Adult Dental Health Survey 2009: relationships between dental attendance patterns, oral health behaviour and the current barriers to dental care. Br Dent J. 2013;214:25–32. doi: 10.1038/sj.bdj.2012.1176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Freeman R. Barriers to accessing dental care: patient factors. Br Dent J. 1999;187:141–144. doi: 10.1038/sj.bdj.4800224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McGrath C, Bedi R. Measuring the impact of oral health on quality of life in Britain using OHQoL-UK(W) J Public Health Dent. 2003;63:73–77. doi: 10.1111/j.1752-7325.2003.tb03478.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McGrath C, Bedi R. The association between dental anxiety and oral health-related quality of life in Britain. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2004;32:67–72. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0528.2004.00119.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Almoznino G, Aframian DJ, Sharav Y, et al. Lifestyle and dental attendance as predictors of oral health-related quality of life. Oral Dis. 2015;21:659–666. doi: 10.1111/odi.12331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wierichs RJ, Meyer-Lueckel H. Systematic review on noninvasive treatment of root caries lesions. J Dent Res. 2015;94:261–271. doi: 10.1177/0022034514557330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Silva J. Evaluación funcional adulto mayor EFAM-Chile. Medwave. 2005;5:e667. [Google Scholar]

- 13.León S, Bravo-Cavicchioli D, Correa-Beltrán G, et al. Validation of the Spanish version of the Oral Health Impact Profile (OHIP-14Sp) in elderly Chileans. BMC Oral Health. 2014;14:95. doi: 10.1186/1472-6831-14-95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Quiroga P, Albala C, Klaasen G. Validation of a screening test for age associated cognitive impairment, in Chile. Rev Med Chil. 2004;132:467–478. doi: 10.4067/s0034-98872004000400009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Babor T, Higgins-Biddle J, Saunders J, et al. 2nd ed. World Health Organization; Geneva: 2001. The Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test: Guidelines for Use in Primary Care [internet] Available at: http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/67205/1/WHO_MSD_MSB_01.6a.pdf. Accessed 29 November 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 16.León S, Bravo-Cavicchioli D, Giacaman RA, et al. Validation of the Spanish version of the oral health impact profile to assess an association between quality of life and oral health of elderly Chileans. Gerodontology. 2016;33:97–105. doi: 10.1111/ger.12124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Slade GD. Derivation and validation of a short-form oral health impact profile. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 1997;25:284–290. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0528.1997.tb00941.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Locker D. Measuring oral health: a conceptual framework. Community Dent Health. 1988;5:3–18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Locker D. Health outcomes of oral disorders. Int J Epidemiol. 1995;24(Suppl 1):S85–S89. doi: 10.1093/ije/24.supplement_1.s85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Likert R. A technique for the measurement of attitudes. Arch Psychol. 1932;140:1–55. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sierwald I, John MT, Durham J, et al. Validation of the response format of the Oral Health Impact Profile. Eur J Oral Sci. 2011;119:489–496. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0722.2011.00884.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Larsson P, List T, Lundström I, et al. Reliability and validity of a Swedish version of the Oral Health Impact Profile (OHIP-S) Acta Odontol Scand. 2004;62:147–152. doi: 10.1080/00016350410001496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Robinson PG, Gibson B, Khan FA, et al. Validity of two oral health-related quality of life measures. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2003;31:90–99. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0528.2003.00051.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rener-Sitar K, Petricević N, Celebić A, et al. Psychometric properties of Croatian and Slovenian short form of oral health impact profile questionnaires. Croat Med J. 2008;49:536–544. doi: 10.3325/cmj.2008.4.536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Khalifa N, Allen PF, Abu-bakr NH, et al. Psychometric properties and performance of the Oral Health Impact Profile (OHIP-14s-ar) among Sudanese adults. J Oral Sci. 2013;55:123–132. doi: 10.2334/josnusd.55.123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.International Caries Detection and Assessment System (ICDAS) Coordinating Committee. Criteria Manual: International Caries Detection and Assessment System (ICDASII). Workshop held in Baltimore, Maryland, 2005. 12th–14th March, 2005

- 27.Nyvad B, Machiulskiene V, Baelum V. Reliability of a new caries diagnostic system differentiating between active and inactive caries lesions. Caries Res. 1999;33:252–260. doi: 10.1159/000016526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fejerskov O. 3rd ed. Wiley Blackwell; Oxford: 2015. Dental Caries. The Disease and Its Clinical Management. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nordström A, Birkhed D. Preventive effect of high-fluoride dentifrice (5,000 ppm) in caries-active adolescents: a 2-year clinical trial. Caries Res. 2010;44:323–331. doi: 10.1159/000317490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nordström A, Birkhed D. Fluoride retention in proximal plaque and saliva using two NaF dentifrices containing 5,000 and 1,450 ppm F with and without water rinsing. Caries Res. 2009;43:64–69. doi: 10.1159/000201592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Guentsch A, Pfister W, Cachovan G, et al. Oral prophylaxis and its effects on halitosis-associated and inflammatory parameters in patients with chronic periodontitis. Int J Dent Hyg. 2014;12:199–207. doi: 10.1111/idh.12063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Al-Harthi LS, Cullinan MP, Leichter JW, et al. The impact of periodontitis on oral health-related quality of life: a review of the evidence from observational studies. Aust Dent J. 2013;58:274–277. doi: 10.1111/adj.12076. quiz 384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Reisine ST, Fertig J, Weber J, et al. Impact of dental conditions on patients’ quality of life. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 1989;17:7–10. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0528.1989.tb01816.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Needleman I, McGrath C, Floyd P, et al. Impact of oral health on the life quality of periodontal patients. J Clin Periodontol. 2004;31:454–457. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051X.2004.00498.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cunha-Cruz J, Hujoel PP, Kressin NR. Oral health-related quality of life of periodontal patients. J Periodontal Res. 2007;42:169–176. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0765.2006.00930.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Aslund M, Pjetursson BE, Lang NP. Measuring oral health-related quality-of-life using OHQoL-GE in periodontal patients presenting at the University of Berne, Switzerland. Oral Health Prev Dent. 2008;6:191–197. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jowett AK, Orr MT, Rawlinson A, et al. Psychosocial impact of periodontal disease and its treatment with 24-h root surface debridement. J Clin Periodontol. 2009;36:413–418. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051X.2009.01384.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Araújo AC, Gusmão ES, Batista JE, et al. Impact of periodontal disease on quality of life. Quintessence Int. 2010;41:e111–e118. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Montero J, Albaladejo A, Zalba JI. Influence of the usual motivation for dental attendance on dental status and oral health-related quality of life. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal. 2014;19:e225–e231. doi: 10.4317/medoral.19366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.dos Santos CM, Martins AB, de Marchi RJ, et al. Assessing changes in oral health-related quality of life and its factors in community-dwelling older Brazilians. Gerodontology. 2013;30:176–186. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-2358.2012.00656.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Adair J. The Hawthorne effect: a reconsideration of the methodological artifact. J Appl Psychol. 1984;69:334–345. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Parsons H. Hawthorne: an early OBM experiment. J Organ Behav Manage. 1992;12:27–43. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Claydon N, Hunter L, Moran J, et al. A 6-month home-usage trial of 0.1% and 0.2% delmopinol mouthwashes (I). Effects on plaque, gingivitis, supragingival calculus and tooth staining. J Clin Periodontol. 1996;1:220–228. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051x.1996.tb02079.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gilbert GH, Duncan RP, Campbell AM. Evaluation for an observation effect in a prospective cohort study of oral health outcomes. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 1998;26:233–240. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0528.1998.tb01956.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Feil PH, Grauer JS, Gadbury-Amyot CC, et al. Intentional use of the Hawthorne effect to improve oral hygiene compliance in orthodontic patients. J Dent Educ. 2002;66:1129–1135. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Owens J, Addy M, Faulkner J. An 18-week home-use study comparing the oral hygiene and gingival health benefits of triclosan and fluoride toothpastes. J Clin Periodontol. 1997;24(9):626–631. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051x.1997.tb00239.x. Pt 1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Petersson LG. The role of fluoride in the preventive management of dentin hypersensitivity and root caries. Clin Oral Investig. 2013;17(Suppl 1):S63–S71. doi: 10.1007/s00784-012-0916-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Armfield JM, Stewart JF, Spencer AJ. The vicious cycle of dental fear: exploring the interplay between oral health, service utilization and dental fear. BMC Oral Health. 2007;7:1. doi: 10.1186/1472-6831-7-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mariño R, Giacaman RA. Patterns of use of oral health care services and barriers to dental care among ambulatory older Chilean. BMC Oral Health. 2017;17:38. doi: 10.1186/s12903-016-0329-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Muirhead VE, Marcenes W, Wright D. Do health provider-patient relationships matter? Exploring dentist-patient relationships and oral health-related quality of life in older people. Age Ageing. 2014;43:399–405. doi: 10.1093/ageing/aft183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Beck RS, Daughtridge R, Sloane PD. Physician-patient communication in the primary care office: a systematic review. J Am Board Fam Pract. 2002;15:25–38. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Slade M, Leese M, Cahill S, et al. Patient-rated mental health needs and quality of life improvement. Br J Psychiatry. 2005;187:256–261. doi: 10.1192/bjp.187.3.256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Trachtenberg F, Dugan E, Hall MA. How patients’ trust relates to their involvement in medical care. J Fam Pract. 2005;54:344–352. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Mehrstedt M, John MT, Tönnies S, et al. Oral health-related quality of life in patients with dental anxiety. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2007;35:357–363. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0528.2007.00376.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Silva FC, Sampaio RF, Ferreira FR, et al. Influence of context in social participation of people with disabilities in Brazil. Rev Panam Salud Publica. 2013;34:250–256. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Fuentes-García A, Lera L, Sánchez H, et al. Oral health-related quality of life of older people from three South American cities. Gerodontology. 2013;30:67–75. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-2358.2012.00649.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Tsakos G, Sheiham A, Iliffe S, et al. The impact of educational level on oral health-related quality of life in older people in London. Eur J Oral Sci. 2009;117:286–292. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0722.2009.00619.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Erić J, Stančić I, Tihaček-Šojić L, et al. Prevalence, severity, and clinical determinants of oral impacts in older people in Bosnia and Herzegovina. Eur J Oral Sci. 2012;120:438–443. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0722.2012.00994.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Gilbert GH. Racial and socioeconomic disparities in health from population-based research to practice-based research: the example of oral health. J Dent Educ. 2005;69:1003–1014. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Makhija SK, Gilbert GH, Boykin MJ, et al. The relationship between sociodemographic factors and oral health-related quality of life in dentate and edentulous community-dwelling older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2006;54:1701–1712. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2006.00923.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Rebelo MA, Cardoso EM, Robinson PG, et al. Demographics, social position, dental status and oral health-related quality of life in community-dwelling older adults. Qual Life Res. 2016;25:1735–1742. doi: 10.1007/s11136-015-1209-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kressin NR, Atchison KA, Miller DR. Comparing the impact of oral disease in two populations of older adults: application of the geriatric oral health assessment index. J Public Health Dent. 1997;57:224–232. doi: 10.1111/j.1752-7325.1997.tb02979.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Locker D, Jokovic A. Three-year changes in self-perceived oral health status in an older Canadian population. J Dent Res. 1997;76:1292–1297. doi: 10.1177/00220345970760060901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Gao L, Green E, Barnes LE, et al. Changing non-participation in epidemiological studies of older people: evidence from the Cognitive Function and Ageing Study I and II. Age Ageing. 2015;44:867–873. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afv101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Nummela O, Sulander T, Helakorpi S, et al. Register-based data indicated nonparticipation bias in a health study among aging people. J Clin Epidemiol. 2011;64:1418–1425. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2011.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.SENAMA. Catastro Nacional de Organizaciones Sociales de Adultos Mayores; 2008. Available at: http://www.senama.cl/filesapp/CATASTRO_ORGANIZACIONES_2008.pdf. Accessed 1 May 2017