Abstract

Objectives: To describe antimicrobial prescribing by Belgian dentists in ambulatory care, from 2010 until 2016. Materials and methods: Reimbursement data from the Belgian National Institute for Health and Disability Insurance were analysed to evaluate antimicrobial prescribing (WHO ATC-codes J01/P01AB). Utilisation was expressed in defined daily doses (DDDs), and in DDDs and packages per 1000 inhabitants per day (DID and PID, respectively). Additionally, the number of DDD and packages per prescriber was calculated. Results: In 2016, the dentistry-related prescribing rate of ‘Antibacterials for systemic use’ (J01) and ‘Antiprotozoals’ (P01AB) was 1.607 and 0.014 DID, respectively. From 2010 to 2016, the DID rate of J01 increased by 6.3%, while the PID rate declined by 6.7%. Amoxicillin and amoxicillin with an enzyme inhibitor were the most often prescribed products, followed by clindamycin, clarithromycin, doxycycline, azithromycin and metronidazole. The proportion of amoxicillin relative to amoxicillin with an enzyme inhibitor was low. The narrow-spectrum antibiotic penicillin V was almost never prescribed. Conclusions: Antibiotics typically classified as broad- or extended-spectrum were prescribed most often by Belgian dentists during the period 2000–2016. Although the DID rate of all ‘Antibacterials for systemic use’ (J01) increased over the years, the number of prescriptions per dentist decreased since 2013. The high prescription level of amoxicillin with an enzyme inhibitor is particularly worrying. It indicates that there is a need for comprehensive clinical practice guidelines for Belgian dentists.

Key words: Antibiotics, antimicrobial utilisation, consumption, odontogenic infection, dentistry

INTRODUCTION

In dental practice, antibiotics are either prescribed for prophylactic or therapeutic use. The indications for antibiotic prophylaxis in dentistry are essentially limited to the prevention of infectious endocarditis (IE) and the treatment of severely immunocompromised patients1., 2., 3.. Today, antibiotic prophylaxis in patients with the highest risk of IE is only recommended when the dental procedure is considered invasive and involves manipulation of gingival tissue or the periapical region of teeth, or perforation of the oral mucosa4., 5., 6.. Indications for prescribing antibiotics for prophylactic reasons in dentistry are therefore limited to, for example, dental extractions, periodontal surgery and implant placement. Even under these circumstances, there is little evidence that supports the prophylactic use of antibiotics7.

Therapeutic use of antibiotics in odontogenic infections should be seen as adjunctive to a clinical intervention, not as an alternative8. Systemic antimicrobial therapy has for instance been suggested as an adjunct to periodontal therapy. However, clear guidelines for the use of these agents in periodontics are not available9. In daily practice, antibiotics are sometimes prescribed as the sole treatment of pulpitis, acute periapical infection or alveolar osteitis (dry socket), while these indications require a clinical intervention rather than an antimicrobial treatment10.

Indications for empirical antibiotic treatment include oral infections in combination with fever and/or evidence of systemic spread, such as the proliferation of lymph nodes, trismus and facial cellulitis8., 10.. If an antimicrobial treatment is indicated, antibiotics should be given for the shortest time possible. However, treatment duration should be weighed carefully, taking into account pharmacokinetics of the chosen product, the patients’ immune status, and the chances for relapse of the specific target disease10., 11.. The unnecessary use of broad-spectrum antibiotics should be avoided10., 12..

Any use of antimicrobials may result in the development of clinically relevant antimicrobial resistance (AMR). This risk increases if antimicrobials are used in a non-prudent way. Overuse of antibiotics together with an inappropriate choice, unadjusted formulation, dosage or duration of therapy, may not only lead to AMR but also to unfavourable side-effects13., 14.. According to the action plan of the European Commission of 2017, responsible use of antimicrobials in both human and veterinary medicine is one of the main approaches in tackling AMR15. This makes the monitoring of antimicrobial consumption an indispensable part of the fight against AMR. This plan should eventually lead to a more rational and targeted use, maximising the therapeutic effect and minimising the development of AMR14., 15..

These objectives are shared by the Belgian Antibiotic Policy Coordinating Committee (BAPCOC) that has published guidelines for antimicrobial use in Belgian ambulatory care16. The specific section on dentistry in the BAPCOC guidelines is limited to the treatment of dental abscesses, and does not contain advice on the antibiotic treatment of other oral infections that may require antimicrobial treatment, such as pericoronitis associated with the third molar teeth. More precisely, it states that ‘The primary treatment consists of the necessary dental care. Antibiotics are only indicated in case of local expansion of the abscess to the bone’. Amoxicillin is suggested as the first choice to treat dental abscesses, as it penetrates the bone well and as it is active against a wide range of oral pathogens16. The use of amoxicillin with an enzyme inhibitor is not recommended, because of its broad spectrum and its potential side-effects. Neither do they recommend the use of the narrow-spectrum antibiotic phenoxymethylpenicillin (penicillin V) in this setting. Although not always demonstrating good in vitro susceptibility and achieving lower bone penetration levels than amoxicillin, some studies indicate that penicillin V might remain an antibiotic of first choice when treating odontogenic abscesses, but only if the systemic antimicrobial treatment is accompanied by proper evacuation of pus, with local debridement12., 17., 18., 19..

Advice on antibiotic prophylaxis to prevent IE and prosthetic joint infections is provided by the Belgian Centre for Pharmacotherapeutic Information (BCFI-CBIP)6: following the British NICE guidelines, the use of prophylactic antibiotics should be restricted to high-risk patients undergoing invasive procedures. Optimal oral hygiene and regular dental check-ups are the best measures to prevent IE2., 6.. Good guidelines are certainly needed because a study by Mainjot et al.20, indicated a lack of knowledge and awareness of good antibiotic prescribing practices among Belgian dentists.

Data on the number of prescriptions as well as the types of antibiotics used in the Belgian ambulatory sector (i.e. outside the hospitals) are collected by the Belgian National Institute for Health and Disability Insurance (INAMI-RIZIV, Farmanet)21. Specific data on dentistry-related prescribing have not been reported nor discussed so far in the international literature. The aim of this study was to describe the actual antibiotic prescriptions by Belgian dentists, using available reimbursement data.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Ethics

This research did not directly involve human subjects. This is a retrospective study based on a data collection that is required by law, for which no permission is needed from an institutional review board. Research has been conducted in full accordance with ethical principles, including the World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki (version 2008). We received and analysed data that were already anonymised, de-identified and aggregated by the data provider (INAMI-RIZIV).

Methods

A retrospective study of antimicrobial utilisation, prescribed by Belgian dentists between 2010 and 2016, was performed using the latest available reimbursement data from INAMI-RIZIV, Farmanet21. In 2016, approximately 98.6% of the Belgian population was covered by a health insurance and hence were included in the database22. Only prescriptions actually collected by a patient in a community pharmacy were considered as consumed drugs and were included in the analyses. These include prescriptions made by dentists in both community settings as in hospital settings, as long as the patient was not hospitalised. In the latter case, the patient would receive his/her medication from the hospital pharmacy, and the prescription would not be included in this study.

The antimicrobials were classified according to the Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical (ATC) classification of the World Health Organisation (WHO)23. For the purpose of this study, the following ATC-codes relevant to dentistry were selected: J01 (Antibacterials for systemic use) and P01AB (Nitroimidazole derivatives used orally and rectally as antiprotozoals). Antimycotics were not included in the present study.

Antimicrobial use (numerator) was expressed in defined daily doses (DDDs, WHO version of January 201723) and number of packages. A DDD is the assumed average maintenance dose per day for a drug used for its main indication in adults24. The number of Belgian inhabitants (based on data of Eurostat25) and the number of prescribers (based on data of INAMI-RIZIV26) were used as a denominator to calculate DDDs and packages per 1,000 inhabitants per day (DID and PID, respectively), as well as DDDs and packages per prescriber. We could only consider active dentists in the calculation of DDDs/packages per prescriber, as RIZIV-INAMI only provided those data. A dentist was defined active by RIZIV-INAMI if (s)he performed at least 300 reimbursed procedures per year26. Prescriptions by maxillofacial surgeons that were collected in the ambulatory setting were included in these data as well. Finally, the dentistry-related use in DID was expressed proportionally over the overall ambulant use in DID in Belgium (based on the ESAC-Net data for the ambulatory sector for Belgium, same data source: INAMI-RIZIV, Farmanet21) within the selected ATC classes.

Data management, analysis and plotting were performed with STATA 14.2 (StataCorp. 2015. Stata Statistical Software: Release 14. College Station, TX: StataCorp LP). As only aggregated data were available, no tests for trends or confidence intervals were calculated.

RESULTS

The number of active dentists and maxillofacial surgeons in Belgium increased from 7,022 in 2010 to 7,653 in 2016 (+ 9.0%), while the number of Belgian inhabitants increased by 4.3% over the same period from 10.8 million to 11.3 million (Table 1). The total number of DDDs of ‘Antibacterials for systemic use’ (J01) prescribed by dentists increased by 11.2%, resulting in an increase of 6.3% in the DID rate from 1.512 in 2010 to 1.607 in 2016 (Table 2; Figure S1). The total number of DDDs of ‘Antiprotozoals’ (P01AB) increased by 37.2%, reflecting an increase of 31.2% in the DID rate from 0.011 in 2010 to 0.014 in 2016. The most often prescribed (ATC classified) antiprotozoal product was metronidazole (99.7% of all antiprotozoals prescribed).

Table 1.

Total number of active dentists (≥300 reimbursed procedures per year) and number of inhabitants in Belgium (2010–2016)

| 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of active dentists* (N) | ||||||

| 7,022 | 7,065 | 7,171 | 7,232 | 7,359 | 7,539 | 7,653 |

| Number of inhabitants† (N, ×106) | ||||||

| 10.840 | 11.001 | 11.095 | 11.162 | 11.181 | 11.237 | 11.311 |

Belgian National Institute for Health and Disability Insurance (INAMI-RIZIV).

Source: Eurostat, situation on 1 January of the respective year.

Table 2.

Antimicrobials prescribed by Belgian dentists in the ambulatory setting from 2010 to 2016, calculated in DDD (top), in DID (middle) and in DDD per prescriber (bottom)

| Antimicrobial group | 2010 |

2011 |

2012 |

2013 |

2014 |

2015 |

2016 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DDD (×1,000) | |||||||

| Antibacterials for systemic use (J01) | 5983.4 | 6130.4 | 6218.2 | 6455.0 | 6420.1 | 6597.8 | 6652.8 |

| Antiprotozoals (P01AB) | 43.2 | 45.4 | 47.8 | 50.9 | 54.6 | 58.9 | 59.3 |

| Antimicrobial product | DID | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amoxicillin (J01CA04) | 0.702 | 0.717 | 0.732 | 0.762 | 0.770 | 0.792 | 0.789 |

| Amoxicillin + enzyme inhibitor (J01CR02) | 0.561 | 0.570 | 0.565 | 0.595 | 0.587 | 0.609 | 0.620 |

| Ratio J01CA04/J01CR02* | 1.251 | 1.258 | 1.296 | 1.281 | 1.312 | 1.300 | 1.273 |

| Clindamycin (J01FF01) | 0.074 | 0.074 | 0.078 | 0.079 | 0.076 | 0.076 | 0.075 |

| Clarithromycin (J01FA09) | 0.058 | 0.055 | 0.049 | 0.045 | 0.043 | 0.040 | 0.039 |

| Doxycycline (J01AA02) | 0.050 | 0.049 | 0.045 | 0.042 | 0.036 | 0.034 | 0.031 |

| Azithromycin (J01FA10) | 0.025 | 0.024 | 0.025 | 0.025 | 0.025 | 0.026 | 0.027 |

| Metronidazole (P01AB01) | 0.011 | 0.011 | 0.012 | 0.012 | 0.013 | 0.014 | 0.014 |

| Spiramycin (J01FA02) | 0.009 | 0.008 | 0.007 | 0.007 | 0.006 | 0.006 | 0.005 |

| Cefuroxime (J01DC02) | 0.005 | 0.005 | 0.005 | 0.005 | 0.006 | 0.005 | 0.005 |

| Nitrofurantoin (J01XE01) | 0.002 | 0.002 | 0.003 | 0.003 | 0.003 | 0.003 | 0.003 |

| Phenoxymethylpenicillin (J01CE02) | <0.0001 | 0.0001 | 0.0001 | 0.0001 | 0.0001 | 0.0001 | 0.0001 |

| Other | 0.026 | 0.023 | 0.022 | 0.022 | 0.021 | 0.017 | 0.013 |

| Antibacterials for systemic use (J01) | 1.512 | 1.527 | 1.531 | 1.584 | 1.573 | 1.609 | 1.607 |

| Antiprotozoals (P01AB) | 0.011 | 0.011 | 0.012 | 0.013 | 0.013 | 0.014 | 0.014 |

| Total | 1.523 | 1.538 | 1.543 | 1.597 | 1.586 | 1.623 | 1.621 |

| Antimicrobial group | DDD/Prescriber | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Antibacterials for systemic use (J01) | 852 | 868 | 867 | 893 | 872 | 875 | 869 |

| Antiprotozoals (P01AB) | 6.2 | 6.4 | 6.7 | 7.0 | 7.4 | 7.8 | 7.7 |

Calculated as DID(J01CA04) divided by DID(J01CR02).

DDD, defined daily dose; DID, DDDs per 1,000 inhabitants per day.

Over the entire study period, dentists predominantly prescribed broad- or extended-spectrum penicillins such as amoxicillin, with and without an enzyme inhibitor (Table 2; Figure S1). These two antibiotics accounted for 87.7% of all DID of J01 in 2016 [(DID(J01CA04) + DID(J01CR02))/DID(J01)]. The total DID rate for amoxicillin rose from 0.702 in 2010 to 0.789 in 2016, representing a 12.4% increase. In that period, a similar increase could be observed for the amoxicillin/enzyme inhibitor combination (+10.6%). The proportion of amoxicillin alone relative to amoxicillin with an enzyme inhibitor [DID(J01CA04)/DID(J01CR02)] was low (1.273 in 2016), and relatively constant over the years (Table 2; Figure S1).

The DID rate for the lincosamide clindamycin, which is often prescribed for odontogenic infections in patients who are allergic to beta-lactam antibiotics, increased slightly from 0.074 in 2010 to 0.079 in 2013, and decreased again to 0.075 in 2016. Other products that were prescribed were macrolides (clarithromycin, azithromycin and spiramycin), tetracyclines (doxycycline), the 2nd generation cephalosporin cefuroxime, and nitrofurantoin. The DID rate for penicillin V remained very low (0.0001).

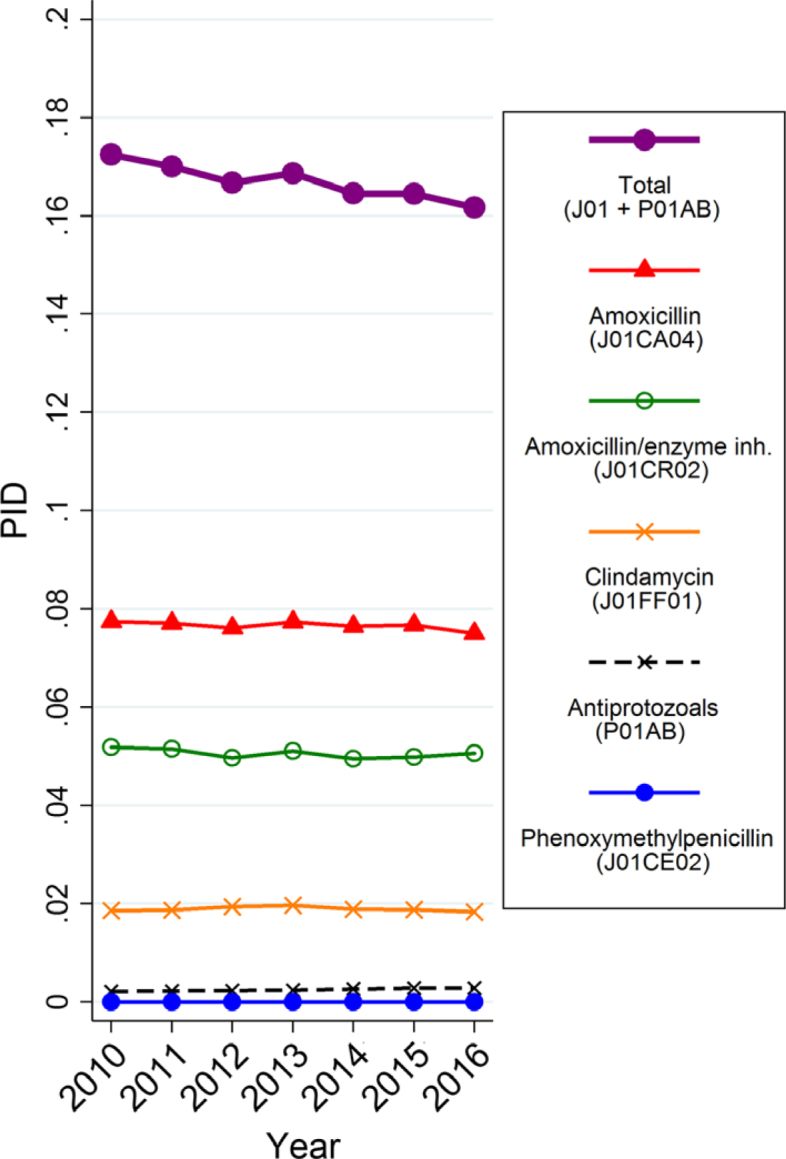

After an initial increase from 852 DDD/prescriber in 2010 to 893 DDD/prescriber in 2013, the mean rate of DDD/prescriber declined to 869 in 2016. Also in contrast to the total number of DDD and DID rate, the number of prescribed packages of J01 declined since 2013 (from a total of 674,000 in 2010, up to 677,000 in 2013, down to 657,000 packages in 2016), while the total number of packages of antiprotozoals increased by 34.2% (from almost 9,000 in 2010 up to nearly 12,000 in 2016; Table S1). Similar trends could be observed for the PID rate (Figure 1). The number of prescribed packages per dentist declined from 96 packages in 2010 to 86 in 2016 for J01. Again, the largest decrease started from 2013 onwards.

Figure 1.

Trends of dentistry-related antimicrobial use, expressed in number of packages per 1,000 inhabitants per day (PID) from 2010 to 2016 (Belgian ambulatory setting).

Proportion of dentistry-related antimicrobial use relative to the total ambulatory use

In 2016 the dentistry-related consumption represented 5.8% of the total J01 antibacterial use in the ambulatory setting (Table 3). The relative contribution in that year to the total antimicrobial use in ambulatory care was high for amoxicillin (10.5% of all amoxicillin used in Belgian ambulatory care was prescribed by dentists), amoxicillin with an enzyme inhibitor (8.4%), clindamycin (20.1%) and metronidazole (11.6%). In contrast, the relative contribution of penicillin V was very low (0.3%).

Table 3.

Relative contribution of dentistry-related antimicrobial use to the total ambulatory use in Belgium (2016)

| Antimicrobial product | Dentistry-related use (DID) | Total use in ambulatory setting (DID) | Proportion dentistry-related use to total ambulatory use (%)* |

|---|---|---|---|

| Amoxicillin (J01CA04) | 0.789 | 7.510 | 10.5 |

| Amoxicillin + enzyme inhibitor (J01CR02) | 0.620 | 7.380 | 8.4 |

| Clindamycin (J01FF01) | 0.075 | 0.373 | 20.1 |

| Clarithromycin (J01FA09) | 0.039 | 1.410 | 2.8 |

| Doxycycline (J01AA02) | 0.031 | 0.754 | 4.1 |

| Azithromycin (J01FA10) | 0.027 | 1.770 | 1.5 |

| Metronidazole (P01AB01) | 0.014 | 0.123 | 11.6 |

| Spiramycin (J01FA02) | 0.005 | 0.020 | 26.4 |

| Cefuroxime (J01DC02) | 0.005 | 1.240 | 0.4 |

| Nitrofurantoin (J01XE01) | 0.003 | 1.550 | 0.2 |

| Phenoxymethylpenicillin (J01CE02) | 0.0001 | 0.026 | 0.3 |

| Other | 0.013 | 5.354 | 0.2 |

| Antibacterials for systemic use (J01) | 1.607 | 27.510 | 5.8 |

| Antiprotozoals (P01AB) | 0.014 | 1.1340 | 10.7 |

| Total | 1.621 | 28.644 | 5.7 |

Calculated as: DID in column one divided by the DID in column two, multiplied by 100.

DID, defined daily dose (DDDs) per 1,000 inhabitants per day.

DISCUSSION

The results of the present study indicate that antibiotics typically classified as broad- or extended-spectrum were prescribed most often. Amoxicillin and amoxicillin with an enzyme inhibitor were the most often prescribed products, followed by clindamycin, clarithromycin, doxycycline, azithromycin and metronidazole. In contrast, the DID rate for the only real narrow-spectrum antibiotic available to dentists, penicillin V, remained very low (0.0001). Especially striking is the low proportion of amoxicillin relative to amoxicillin with an enzyme inhibitor, as the latter antibiotic is not recommended in the BAPCOC guidelines16. The committee issued a policy paper for the 2014–2019 term, outlining policies to improve antibiotic use and appropriateness of antibiotic prescriptions, and including targets for the various sectors27. One of the targets mentioned for the ambulatory sector is the increase in amoxicillin to amoxicillin + clavulanic acid ratio, from about 50/50 in 2014 to 80/20 by 2018. It remains to be seen whether this goal has been achieved. Amoxicillin in combination with an enzyme inhibitor is a highly effective product to combat anaerobic oral pathogens, but its use should be carefully weighed as this antibacterial product does not only promote the development of AMR and gut microbiota disturbances, it is also potentially hepatotoxic28., 29..

The seemingly contradictory observation that from 2010 to 2016 the DID rate increased by 6.3% (for J01), while the total PID rate declined by 6.7%, can be explained by the fact that over the years a substantial increase of DDDs per package for the most commonly used antibiotics has been seen in Belgium and other European countries30., 31., 32.. Consequently, differing trends can be observed over time in Belgium for these two units of measurement (DID vs. PID). The number of prescribed packages per dentist as well as the number of DDD per prescriber declined from 2013 onwards, indicating a ‘real’ decline in the number of prescriptions. One explanation for this may be the relatively rapid replacement over the last decade of the older population of dentists by younger colleagues26, who are possibly differently trained and better aware of recent advances in knowledge related to adverse events, AMR and good prescribing practices. This hypothesis remains to be investigated.

The relatively low level of dental antimicrobial use (5.8%) compared with total use in ambulatory care is largely a function of the relatively high community use in Belgium as a whole32. Especially clindamycin was prescribed relatively more often by dentists compared with other ambulatory care professionals. In 2016, dentists prescribed 20% of all clindamycin in Belgian ambulatory care. This raises the question whether Belgian dentists adequately assess beta-lactam allergies. Clindamycin has a favourable spectrum of activity against anaerobic infections and concentrates well in bone. It is therefore often recommended as a second choice in case of beta-lactam allergy. However, it also has a high potential for intestinal problems, from abdominal pain and diarrhoea to acute pseudomembranous colitis33.

Our findings are in line with a study describing the antimicrobial prescribing behaviour of Belgian dentists in 200420. That report, based on self-administered questionnaires filled out by a random sample of 268 dentists, stated that amoxicillin was the most often prescribed antimicrobial product by Belgian dentists that year (51.1% of all antimicrobial prescriptions), followed by amoxicillin with an enzyme inhibitor (24.0%) and clindamycin (6.6%). In 2016, Belgian dentists still prescribed amoxicillin most often [49.1% of DID (J01)], followed by amoxicillin with an enzyme inhibitor [38.6% of DID (J01)] and clindamycin [4.7% of DID (J01); Table 2]. Apparently, amoxicillin with an enzyme inhibitor is now prescribed more often, but the actual Farmanet reimbursement data of 200421 indicated that this antibiotic was more often prescribed than the percentage reported by the survey. The proportion of amoxicillin relative to amoxicillin with an enzyme inhibitor has not changed much since 2004.

A study performed in Norway revealed that the narrow-spectrum antibiotic penicillin V was the product of first choice of Norwegian dentists in 2004–2005, while amoxicillin with an enzyme inhibitor was hardly ever prescribed that year (DID < 0.001)34. Also in Sweden, the product of first choice was penicillin V (2012–2016), followed by amoxicillin and clindamycin35. Those antibiotic substances represented 73%, 9% and 9%, respectively, of all antibiotics prescribed by dentists in 2016. The total PID rate was more than two times less than the PID rate in Belgium in that same year (0.06 vs. 0.16)35. A study performed in England (1999) showed that amoxicillin was the most often prescribed product, followed by metronidazole and penicillin V. Prescriptions of amoxicillin with an enzyme inhibitor were not reported36. The question arises whether these large differences in prescribing behaviour compared with Belgium are due to an actual lower prevalence of AMR to narrow-spectrum antibiotics such as penicillin among oral target pathogens in Norway, Sweden and England, or due to a different attitude towards prescribing practices. Indeed, susceptibility to antimicrobials may vary substantially across countries13. Yet, a dentists’ choice of an antibiotic is usually empirical. It is rarely based on cultures, antimicrobial susceptibility tests or point-of-care testing10., 37..

Both in England and Norway, metronidazole was the second most prescribed antimicrobial34., 36.. In Belgium, the number of prescriptions of this antiprotozoal is rising every year. This is not surprising, as this product is – aside from antiprotozoal stricto senso – highly active against anaerobic oral bacteria and many are involved in periodontal disease38. A finding we did not anticipate was the prescription of the nitrofuran derivative nitrofurantoin (J01XE01). The rapid excretion of nitrofurantoin and the resulting high concentrations in urine make this antibiotic one of the primary choices in urinary tract infections39. Its low bioavailability in other body tissues such as bone makes this product unsuited for the treatment of oral infections40. Yet, it is the 10th most prescribed antimicrobial by Belgian dentists. This might be explained by the fact that, for example, upon request of the patient, some dentists also prescribe antimicrobials for other than dentistry-related indications, such as urinary tract infections. Dentists may also prescribe them for themselves or their family members.

A major strength of this study is the reporting of the actual prescription numbers, based on reimbursement data, thereby covering nearly 99% of the population over a relatively large and recent period. However, we need to acknowledge that a period of 7 years is too short to allow much inference about temporal trends occurring at a population level. Our figures are based on aggregated data, limiting the options for statistical inference, and they may underestimate the number of prescriptions for dentistry-related indications. Patients sometimes receive an antibiotic prescription from their general practitioner, prior to or even independent of visiting a dentist. It also remains hard to assess whether the total dentistry-related antimicrobial use is excessively high or not. This prescribing should be seen in relation to the prevalence of infections that require antimicrobial treatment. Unfortunately, at present no indications for the prescription of antibiotics have to be registered in Belgium. This means we also cannot describe the proportion of antibiotics that were prescribed for either prophylactic or curative purposes. The international literature suggests that most antibiotics in dentistry are prescribed for curative reasons41, and that severe odontogenic infections are rare. Theoretically, indications for antimicrobial use in dentistry are thus very limited10., 37..

In specific clinical situations, antibiotics remain an important asset in a dentist’s toolkit. Oral infections in combination with fever and/or evidence of systemic spread are examples of infections requiring antibiotic treatment, if supported by a clinical intervention. The existing guidelines on antimicrobial use in dentistry are non-exhaustive, and our data suggest that they are not followed by Belgian dentists in general. Currently, there are no antibiotic stewardship programs for dentists in the country. Because amoxicillin with an enzyme inhibitor is prescribed too often, rational use of antibiotics in Belgian dentistry needs to be promoted. Comprehensive clinical practice guidelines should be elaborated and disseminated among dentists. In addition, sensitisation campaigns and continuing education on the prudent use of antibiotics in dentistry should raise awareness of dentists’ responsibilities in the battle against AMR. Evaluating dentistry-related antimicrobial prescribing and AMR of oral or other pathogens after the implementation of these measures may give an indication of their impact.

CONCLUSION

From 2000 to 2016, amoxicillin and amoxicillin with an enzyme inhibitor were the most often prescribed products by Belgian dentists, followed by clindamycin, clarithromycin, doxycycline, azithromycin and metronidazole. The proportion of amoxicillin relative to amoxicillin with an enzyme inhibitor was low. The narrow-spectrum antibiotic penicillin V was rarely prescribed. Comprehensive clinical practice guidelines for dentists, in combination with sensitisation campaigns and continuing education, are needed in Belgium.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Marc de Falleur from the Belgian National Institute for Health and Disability Insurance, Farmanet (RIZIV-INAMI, Brussels, Belgium) for providing the reimbursement data and data on dental practitioners in Belgium.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Funding

There is no funding to disclose. The authors have no financial relationships relevant to this article to disclose.

SUPPORTING INFORMATION

Additional supporting information may be found in the online version of this article:

Figure S1 Trends of dentistry-related antimicrobial consumption expressed in defined daily doses (DDD) per 1,000 inhabitants per day (DID) from 2010 to 2016 (Belgian ambulatory setting).

Table S1 Antimicrobials prescribed by Belgian dentists in the ambulatory setting from 2010 to 2016, calculated in number of packages (top), in packages per 1,000 Inhabitants per day (PID; middle) and in number of packages per prescriber (bottom)

References

- 1.Cahill TJ, Dayer M, Prendergast B, et al. Do patients at risk of infective endocarditis need antibiotics before dental procedures? BMJ. 2017;358:j3942. doi: 10.1136/bmj.j3942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.NICE. Prophylaxis against infective endocarditis: antimicrobial prophylaxis against infective endocarditis in adults and children undergoing interventional procedures: National Institute for Health and Care Excellence; 2016. Available from: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/CG64. Accessed 5 April 2019 [PubMed]

- 3.Thornhill MH, Chambers JB, Dayer M, et al. A change in the NICE guidelines on antibiotic prophylaxis for dental procedures. Br J Gen Pract. 2016;66:460–461. doi: 10.3399/bjgp16X686749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wilson W, Taubert KA, Gewitz M, et al. Prevention of infective endocarditis: guidelines from the American Heart Association: a guideline from the American Heart Association Rheumatic Fever, Endocarditis and Kawasaki Disease Committee, Council on Cardiovascular Disease in the Young, and the Council on Clinical Cardiology, Council on Cardiovascular Surgery and Anesthesia, and the Quality of Care and Outcomes Research Interdisciplinary Working Group. J Am Dent Assoc. 2008;139(Suppl):3S–24S. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.2008.0346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Habib G, Lancellotti P, Iung B. 2015 ESC Guidelines on the management of infective endocarditis: a big step forward for an old disease. Heart. 2016;102:992–994. doi: 10.1136/heartjnl-2015-308791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.BCFI . Belgian Centre for Pharmacotherapeutic Information; Brussels: 2014. Folia pharmacotherapeutica, Volume 41, Number 7. Available from: http://www.bcfi.be/folia_pdfs/NL/P41N08.pdf. Accessed 5 April 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cahill TJ, Harrison JL, Jewell P, et al. Antibiotic prophylaxis for infective endocarditis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Heart. 2017;103:937–944. doi: 10.1136/heartjnl-2015-309102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Swift JQ, Gulden WS. Antibiotic therapy–managing odontogenic infections. Dent Clin North Am. 2002;46:623–633. doi: 10.1016/s0011-8532(02)00031-9. vii. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Feres M, Figueiredo LC, Soares GM, et al. Systemic antibiotics in the treatment of periodontitis. Periodontol 2000. 2015;67:131–186. doi: 10.1111/prd.12075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Martins JR, Chagas OL, Jr, Velasques BD, et al. The use of antibiotics in odontogenic infections: what is the best choice? A systematic review. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2017;75:2606.e1–2606.e11. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2017.08.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Martin MV, Longman LP, Hill JB, et al. Acute dentoalveolar infections: an investigation of the duration of antibiotic therapy. Br Dent J. 1997;183:135–137. doi: 10.1038/sj.bdj.4809444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Warnke PH, Becker ST, Springer IN, et al. Penicillin compared with other advanced broad spectrum antibiotics regarding antibacterial activity against oral pathogens isolated from odontogenic abscesses. J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 2008;36:462–467. doi: 10.1016/j.jcms.2008.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.ECDC . ECDC; Stockholm: 2017. Antimicrobial resistance surveillance in Europe 2016. Annual Report of the European Antimicrobial Resistance Surveillance Network (EARS-Net) Available from: https://ecdc.europa.eu/sites/portal/files/documents/AMR-surveillance-Europe-2016.pdf. Accessed 5 April 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Holmes AH, Moore LS, Sundsfjord A, et al. Understanding the mechanisms and drivers of antimicrobial resistance. Lancet. 2016;387:176–187. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00473-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.European Commission . European Commission; Brussels: 2017. Press release. Antimicrobial Resistance: Commission steps up the fight with new Action Plan. Available from: http://europa.eu/rapid/press-release_IP-17-1762_en.htm. Accessed 5 April 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 16.BAPCOC . Belgian Antibiotic Policy Coordination Committee (BAPCOC); Brussels: 2012. Belgian Guide to Anti-Infectious Treatment in Ambulatory Practice. Edition 2012. Available from: http://overlegorganen.gezondheid.belgie.be/sites/default/files/documents/2012_belgische_gids_voor_anti-inf_behandeling_in_ap.pdf. Accessed 5 April 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Al-Qamachi LH, Aga H, McMahon J, et al. Microbiology of odontogenic infections in deep neck spaces: a retrospective study. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2010;48:37–39. doi: 10.1016/j.bjoms.2008.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Heim N, Faron A, Wiedemeyer V, et al. Microbiology and antibiotic sensitivity of head and neck space infections of odontogenic origin. Differences in inpatient and outpatient management. J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 2017;45:1731–1735. doi: 10.1016/j.jcms.2017.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kuriyama T, Karasawa T, Nakagawa K, et al. Antimicrobial susceptibility of major pathogens of orofacial odontogenic infections to 11 beta-lactam antibiotics. Oral Microbiol Immunol. 2002;17:285–289. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-302x.2002.170504.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mainjot A, D’Hoore W, Vanheusden A, et al. Antibiotic prescribing in dental practice in Belgium. Int Endod J. 2009;42:1112–1117. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2591.2009.01642.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Farmanet . Farmanet, National Institute for Health and Disability Insurance (RIZIV-INAMI); Brussels: 2018. Statistics on medications delivered by public pharmacies. Available from: http://www.riziv.fgov.be/nl/statistieken/geneesmiddel/Paginas/Statistieken-geneesmiddelen-apotheken-farmanet.aspx. Accessed 5 April 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 22.RIZIV-INAMI . National Institute for Health and Disability Insurance (RIZIV-INAMI); Brussels: 2018. Statistics on persons affiliated with a health insurance fund. Available from: http://www.riziv.fgov.be/nl/toepassingen/Paginas/webtoepassing-statistieken-personen-aangesloten-ziekenfonds.aspx. Accessed 5 April 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 23.WHO . WHO Collaboration Centre for Drug Statistics Methodology; Olso: 2018. DDD and ATC-classification. Available from: https://www.whocc.no/atc_ddd_index. Accessed 5 April 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 24.WHO . WHO Collaborating Centre for Drug Statistics Methodology; Oslo: 2018. DDD: Definition and general considerations. Available from: https://www.whocc.no/ddd/definition_and_general_considera/. Accessed 5 April 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 25.EUROSTAT . EUROSTAT; Luxembourg: 2017. Population (demography, migration and projections) Available from: http://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/web/population-demography-migration-projections/population-data. Accessed 5 April 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 26.RIZIV-INAMI . National Institute for Health and Disability Insurance (RIZIV-INAMI); Brussels: 2016. Statistics on health care. Available from: https://www.riziv.fgov.be/nl/statistieken/geneesk-verzorging/Paginas/default.aspx. Accessed 5 April 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 27.BAPCOC . Belgian Antibiotic Policy Coordinating Committee; Brussels: 2014. Policy note legislature 2014-2019. Available from: https://overlegorganen.gezondheid.belgie.be/sites/default/files/documents/belgische_commissie_voor_de_coordinatie_van_het_antibioticabeleid/19100224.pdf. Accessed 5 April 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Garcia Rodriguez LA, Stricker BH, Zimmerman HJ. Risk of acute liver injury associated with the combination of amoxicillin and clavulanic acid. Arch Intern Med. 1996;156:1327–1332. doi: 10.1001/archinte.1996.00440110099013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zaidi SA. Hepatitis associated with amoxicillin/clavulanic acid and/or ciprofloxacin. Am J Med Sci. 2003;325:31–33. doi: 10.1097/00000441-200301000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bruyndonckx R, Hens N, Aerts M, et al. Measuring trends of outpatient antibiotic use in Europe: jointly modelling longitudinal data in defined daily doses and packages. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2014;69:1981–1986. doi: 10.1093/jac/dku063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Coenen S, Bruyndonckx R, Hens N, et al. Comment on: measurement units for antibiotic consumption in outpatients. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2014;69:3445–3446. doi: 10.1093/jac/dku292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.ECDC . European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC); Stockholm: 2017. Antimicrobial consumption interactive database (ESAC-Net) Available from: https://ecdc.europa.eu/en/antimicrobial-consumption/database/rates-country. Accessed 5 April 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Addy LD, Martin MV. Clindamycin and dentistry. Br Dent J. 2005;199:23–26. doi: 10.1038/sj.bdj.4812535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Al-Haroni M, Skaug N. Incidence of antibiotic prescribing in dental practice in Norway and its contribution to national consumption. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2007;59:1161–1166. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkm090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.SWEDRES|SVARM. Consumption of Antibiotics and Occurrence of Antibiotic Resistance in Sweden Solna/Uppsala; 2016. Available from: http://www.sva.se/globalassets/redesign2011/pdf/om_sva/publikationer/swedres_svarm2016.pdf. Accessed 5 April 2019

- 36.Palmer NO, Martin MV, Pealing R, et al. An analysis of antibiotic prescriptions from general dental practitioners in England. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2000;46:1033–1035. doi: 10.1093/jac/46.6.1033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Opitz D, Camerer C, Camerer DM, et al. Incidence and management of severe odontogenic infections-a retrospective analysis from 2004 to 2011. J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 2015;43:285–289. doi: 10.1016/j.jcms.2014.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lofmark S, Edlund C, Nord CE. Metronidazole is still the drug of choice for treatment of anaerobic infections. Clin Infect Dis. 2010;50(Suppl 1):S16–S23. doi: 10.1086/647939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Flores-Mireles AL, Walker JN, Caparon M, et al. Urinary tract infections: epidemiology, mechanisms of infection and treatment options. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2015;13:269–284. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro3432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Conklin JD. The pharmacokinetics of nitrofurantoin and its related bioavailability. Antibiot Chemother. 1971;1978:233–252. doi: 10.1159/000401065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chate RA, White S, Hale LR, et al. The impact of clinical audit on antibiotic prescribing in general dental practice. Br Dent J. 2006;201:635–641. doi: 10.1038/sj.bdj.4814261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]