Abstract

Introduction: Reports examining the impact of oral health on the quality of life of refugees are lacking. The aim of this study was to examine factors influencing oral health-related quality of life (OHRQoL) among Syrian refugees in Jordan. Methods: A cross-sectional survey was conducted on a convenience sample of Syrian refugees, who attended dental clinics held at Azraq camp. The survey assessed the refugees’ oral hygiene practices, and measured their OHRQoL using the Arabic version of the United-Kingdom Oral Health-Related Quality of life measure. Results: In total, 102 refugees [36 male and 66 female; mean age 34 (SD = 10) years] participated. Overall, 12.7% did not brush their teeth and 86.3% did not use adjunctive dental cleaning methods. OHRQoL mean score was 56.55 (range 32–80). Comparison of the physical, social and psychological domains identified a statistically significant difference between the physical and the psychological domain mean scores (ANOVA; P = 0.044, Tukey’s test; P = 0.46). The factors which revealed association with OHRQoL scores in the univariable analyses, and remained significant in the multivariable linear regression analysis, were: age (P = 0.048), toothbrushing frequency (P = 0.001) and attending a dental clinic in the last year (P = 0.004). Conclusion: The physical aspect of quality of life was more negatively impacted than the psychological aspect. Toothbrushing frequency and attending a dental clinic at least once in the last year were associated with more positive OHRQoL scores. Older refugees seemed to be more vulnerable to the impact of poor oral health on OHRQoL.

Key words: Syrian, refugees, oral, health, quality of life

INTRODUCTION

The Syrian crisis was declared by the United Nations to be one of the worst refugee crises in world history1. Since the beginning of the Syrian crisis in 2011, over 650,000 Syrians have fled into Jordan; nearly one-third live in refugee camps2.

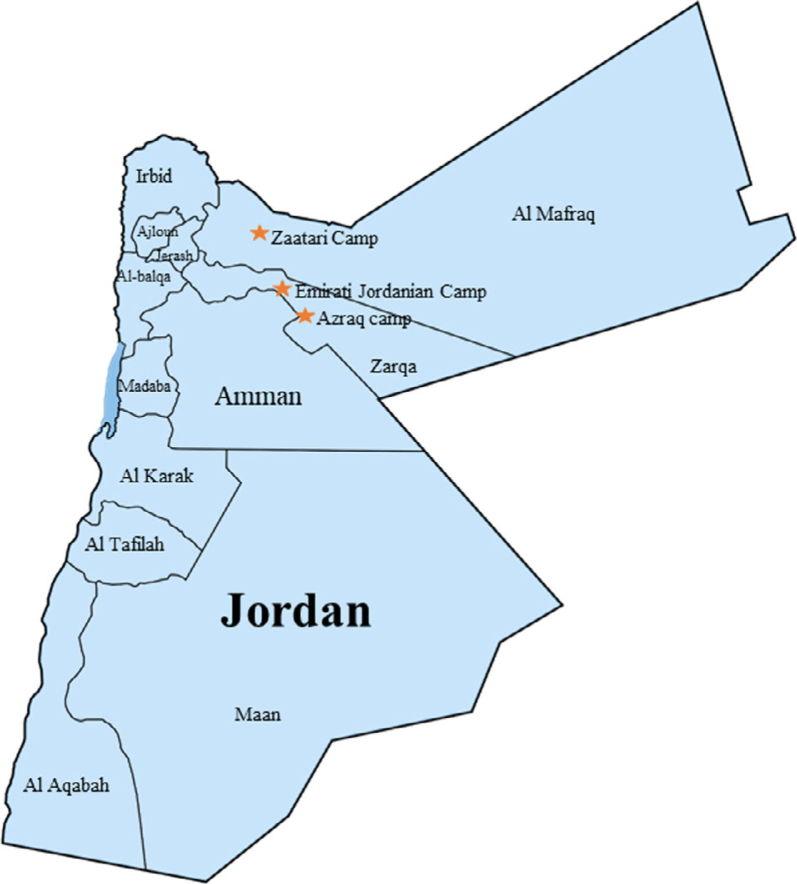

There are three main refugee camps in Jordan (Figure 1). The largest is Zaatari camp (which is also the second largest refugee camp in the world, hosting 78,552 refugees); the Emirati-Jordanian camp, hosting 6,831 refugees; and Azraq camp, which at the time of writing hosted 36,699 refugees and has the capacity to host up to 130,0003, 4, 5, 6.

Figure 1.

The locations and distribution of the Syrian refugees’ camps in Jordan; Zaatari, Emirati Jordanian and Azraq camps.

The refugee experience is characterised by displacement, conflict, human rights violations, persecution, family separation and prolonged times in transit with limited or no access to services or basic necessities; it often includes torture, as well as physical and sexual violence. Refugees are therefore exposed to various medical, psychological and social challenges7, 8, 9, 10, 11. A recent study demonstrated that nearly half of Syrian men in refugee camps suffer from anxiety and depression, and the majority of refugees perceive their health status as ‘bad’ or ‘very bad’. Importantly, more than half of Syrian refugees in the same study reported that their health deteriorated during their stay in the camp12.

The effect of refuge on oral health has only been sparsely studied. Previous studies, which were mainly conducted in developed countries, demonstrated a higher burden of oral diseases and a negative perception of oral health among refugees compared with host residents13, 14, 15, 16, 17. In a Norwegian study of refugees from the Middle East and Africa, in which oral health and impact of oral health on daily living were explored, most of the refugees were found to have clinically detectable caries, and the majority perceived their oral health as poor and in need of treatment. In addition, half of the refugees reported at least one negative impact on their daily life at least once a week14.

Poor oral health can negatively affect the physical, social and psychological well-being of the individual, and result in reduced quality of life18. A recent report by the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) revealed that acute dental conditions, including toothache and swelling, were the third most common acute health conditions among Syrian refugees living in refugee camps in Jordan19, 20. Poor oral health and acute dental conditions can negatively affect the quality of life of Syrian refugees. The present study therefore aimed to assess oral health-related quality of life (OHRQoL) among Syrian refugees in Jordan, using the Arabic version of the United Kingdom oral health-related quality of life (OHRQoL-UK) measure21, 22, and to identify and examine factors influencing the OHRQoL of refugees.

METHODS

The present study was conducted in full accordance with the World Medical Declaration of Helsinki and conformed to the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement for observational studies. The study protocol and consent procedure were reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board, the Deanship of Academic Research at the University of Jordan (IRB number: 5020/2018/19).

As part of a 5-day oral health awareness campaign at Azraq refugee camp, conducted from the 10th to the 14th of September 2017, pre-arranged field visits were performed to investigate OHRQoL among Syrian refugees. The Azraq camp is located in a remote desert area in the north of Jordan (Figure 1). The camp incorporates four primary health-care centres; medical health-care services are provided free of charge through two comprehensive clinics, two basic clinics and one hospital, which are distributed in different areas in the camp4. In addition, there are four dental clinics operating in different locations inside the camp.

Participants were included if they had Syrian nationality, were > 16 years of age and had been residents in the camp for at least 12 months. All patients who were attending the camp dental clinics for treatment or check-up during the study period were eligible to participate. Following a detailed explanation of the nature and purpose of the study, a written consent form was obtained from all the participants, or from their guardians if the participant was below 18 years of age. Participants who failed to sign consent forms, were edentulous or were known to have depression or chronic anxiety (based on their medical record), were excluded from the study. Edentulous patients were excluded from the study because such patients generally suffer from significantly lower OHRQoL than patients who have a full dentition or are even who are partially edentulous14.

Included participants were interviewed by two trained field investigators who explained the nature and the purpose of the study. Participants were then asked to complete a paper-based survey tool that contained information about gender, age, total duration of stay at the camp, social status, tobacco smoking, oral hygiene practices, and dental visits and attitudes.

In addition, participants were asked to complete the Arabic version of the OHRQoL-UK measure, which is a validated tool that assesses the impact of oral health on three main domains: physical; social; and psychological21, 22. In a previous study, the OHRQoL-UK measure demonstrated satisfactory reliability in terms of internal consistency with a high mean correlation between its items, as assessed by its Cronbach alpha value (0.94)21. Included in these three domains are 16 items related to quality of life. Participants’ responses to questions about the influence of oral health on each item in the OHRQoL-UK measure were recorded on a 5-point Likert scale as ‘very good effect’, ‘good effect’, ‘no effect’, ‘bad effect’ or ‘very bad effect’. The wording of the 5-point Likert scale used for the OHRQoL measure was checked against the original UK version. The ‘very good’ answer was given a score of 5, and the ‘very bad’ answer was given a score of 1, yielding a total score in the range of 16 to 80 (where a score of 16 represented the lowest possible OHRQoL score and a score of 80 represented the highest possible OHRQoL score). The higher the OHRQoL-UK measure score, the better the OHRQoL of the participant. The two field investigators were readily available to provide any necessary help or explanation to participants.

Data were analysed using the statistical package software, SPSS 22.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA)23. Internal consistency/reliability was assessed by evaluating the mean correlation between the items in the OHRQoL-UK measure using Cronbach alpha statistics. One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to compare the different quality of life domain mean scores within the sample, followed by a Tukey’s test to assess which domain mean differed from the rest. To determine which independent variables might be important predictors of the OHRQoL total score which is the dependent variable, univariable analyses were performed initially using an independent sample t-test and by calculating the Spearman rank correlation coefficient. Subsequently, variables that were found to be significant at P = 0.10 were incorporated into a multivariable linear regression analysis to assess the independent effect of each variable on OHRQoL scores. Variables with significance at P = 0.05 were selected for the multivariable analysis.

RESULTS

A total of 148 patients attended dental clinics for treatment or an evaluation during the study period, but only 102 Syrian refugees met the inclusion criteria and completed the questionnaire. The sample consisted of 36 (35.3%) men and 66 (64.7%) women, with a mean ± standard deviation (SD) age of 34 ± 10 (range: 16–64) years. The mean duration of stay in the camp was 1.75 ± 0.89 (range: 1.1–3.8) years. Of the participants, 22 were smokers and 80 were non-smokers. Most (n = 89) participants reported brushing their teeth at least once every day, and a minority (n = 14) stated use of additional oral hygiene measures on a regular basis. The additional oral hygiene habits included mouthwash (n = 3), miswak (n = 3) and toothpicks (n = 8). None reported the use of dental floss. Nearly half (n = 51) of participants reported visiting the dental clinic at least once during their stay in the camp, mainly for treatment of a toothache or dental infection.

Regarding the effect of oral health on the quality of life of the refugees, the mean total score for the OHRQoL-UK measure was 56.6 ± 7.8 (range: 32–80). The outcome (OHRQoL total score) was checked for normality of distribution visually using a histogram and a Q-Q plot, and was found to be normally distributed. In addition, The Shapiro–Wilk test reported a value of P > 0.05, which confirmed the normality of the data. The OHRQoL-UK measure used was found to have reached an acceptable level of internal consistency reliability, as determined by a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.78.

Negative impact of oral health on quality of life (i.e., reporting a bad or a very bad effect) were observed across the three domains; 28.8% of the participants reported negative impact on the physical domain, 25.4% on the social domain and 24.4% on the psychological domain (Table 1).

Table 1.

Impact of oral health on the different domains of the United Kingdom Oral Health-Related Quality of Life (OHRQoL-UK) measure

| Participant response* | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OHRQoL-UK items | Very bad effect | Bad effect | No effect | Good effect | Very good effect | Total |

| Physical domain | ||||||

| Eating (food enjoyment) | 11 (10.8) | 42 (41.2) | 6 (5.9) | 33 (32.4) | 10 (9.8) | |

| Appearance | 3 (2.9) | 25 (24.5) | 3 (2.9) | 61 (59.8) | 10 (9.8) | |

| Speech | 2 (2) | 3 (2.9) | 6 (5.9) | 72 (70.6) | 19 (18.6) | |

| Comfort (lack of pain) | 8 (7.8) | 41 (40.2) | 6 (5.9) | 31 (30.4) | 16 (15.7) | |

| Breath odour | 4 (3.9) | 31 (30.4) | 16 (15.7) | 38 (37.3) | 13 (12.7) | |

| General health | 2 (2.0) | 4 (3.9) | 3 (2.9) | 73 (71.6) | 20 (19.6) | |

| Total | 30 (4.9) | 146 (23.9) | 40 (6.5) | 308 (50.3) | 88 (14.4) | 612 (100.0) |

| Social domain | ||||||

| Smiling or laughing | 3 (2.9) | 18 (17.6) | 6 (5.9) | 53 (52.0) | 22 (21.6) | |

| Social life | N/A | 13 (12.7) | 4 (3.9) | 68 (66.7) | 17 (16.7) | |

| Romantic relationships | N/A | 14 (13.7) | 8 (7.8) | 63 (61.8) | 17 (16.7) | |

| Work (ability to do usual job) | 5 (4.9) | 35 (34.3) | 24 (23.5) | 25 (24.5) | 13 (12.7) | |

| Finance | 6 (5.9) | 36 (35.3) | 12 (11.8) | 44 (43.1) | 4 (3.9) | |

| Total | 14 (2.7) | 116 (22.7) | 54 (10.6) | 253 (49.6) | 73 (14.3) | 510 (100.0) |

| Psychological domain | ||||||

| Ability to relax or sleep | 10 (9.8) | 33 (32.4) | 3 (2.9) | 41 (40.2) | 15 (14.7) | |

| Confidence (lack of embarrassment) | 1 (1.0) | 2 (2.0) | 5 (4.9) | 78 (76.5) | 16 (15.7) | |

| Carefree manner (lack of worry) | 6 (5.9) | 18 (17.6) | 13 (12.7) | 62 (60.8) | 3 (2.9) | |

| Mood or happiness | 6 (5.9) | 12 (11.8) | 7 (6.9) | 63 (61.8) | 14 (13.7) | |

| Personality | N/A | 4 (3.9) | 4 (3.9) | 74 (72.5) | 20 (19.6) | |

| Total | 23 (4.5) | 69 (13.5) | 32 (6.3) | 318 (62.4) | 68 (13.3) | 510 (100.0) |

| Total | 67 (4.1) | 331 (20.3) | 126 (7.7) | 879 (53.9) | 229 (14.0) | 1632 (100.0) |

Values are given as n (%). Bold values indicate the answer reported most frequently for each item. Percentages may not add up to 100% exactly, as they were rounded to the nearest tenth.

Participants were asked to score the influence of oral health on each item in the OHRQoL-UK measure using the following 5-point Likert scale: ‘very bad effect’ (score = 1); ‘bad effect’ (score = 2); ‘no effect’ (score =3); ‘good effect’ (score = 4); or ‘very good effect’ (score = 5).

In order to compare the OHRQoL-UK measure scores between the three domains, the average score for each domain was calculated. The average score for the physical domain (3.45/5) was less than the average score for the social domain (3.5/5) and the psychological domain (3.67/5). Using one-way ANOVA, a statistically significant difference was detected between the average scores of the three domains (P = 0.044). A post-hoc Tukey’s test revealed a statistically significant difference between the physical domain and the psychological domain mean scores (P = 0.046, mean difference = −0.21, 95% CI: −0.42 to −0.003). No statistically significant difference was found between the physical and social domains mean scores (P = 0.862), or the social and psychological mean scores (P = 0.149).

Assessing each item of the three domains individually, it was observed that three items were reported by the majority of participants to be impacted negatively by oral health (i.e., reporting a bad or a very bad effect): eating/food enjoyment (n = 53, 52%); comfort/lack of pain (n = 49. 48%); and work/ability to do usual jobs (n = 40, 39.2%). As for the rest of the items, a higher number of participants reported a positive impact over a negative one.

The factors included in the univariable analyses to determine which independent variables might be important predictors of OHRQoL scores were gender, age, duration of stay at the camp, smoking, toothbrushing frequency and attending a dental clinic in the last year (Table 2).

Table 2.

Univariable statistical analyses (independent sample t-test and Spearman rank correlation coefficient) for factors tested for association with oral health-related quality of life (OHRQoL) scores

| Factor (variable) | n | OHRQoL scores | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | |||

| Male | 36 | 56.14 | |

| Female | 66 | 56.77 | |

| MD (95% CI) | −0.63 (−3.87 to 2.60) | 0.698 | |

| Age | |||

| Correlation coefficient | −0.28 | 0.004* | |

| Duration of stay at the camp | |||

| Correlation coefficient | 0.17 | 0.091* | |

| Smoking | |||

| No | 80 | 56.73 | |

| Yes | 22 | 55.90 | |

| MD (95% CI) | 0.82 (−2.94 to 4.57) | 0.667 | |

| Toothbrushing frequency | |||

| No/rarely | 13 | 48.77 | |

| At least once a day | 89 | 57.69 | |

| MD (95% CI) | −8.92 (−13.20 to −4.63) | <0.001* | |

| Adjunctive dental cleaning | |||

| No | 88 | 56.35 | |

| Yes | 14 | 57.79 | |

| MD (95% CI) | −1.43 (−5.92 to 3.50) | 0.527 | |

| Attended a dental clinic in the last year | |||

| No | 48 | 53.17 | |

| Yes | 51 | 60.12 | |

| Not able to confirm | 3 | ||

| MD (95% CI) | −6.95 (−9.66 to −4.24) | <0.001* | |

MD, mean difference.

Statistically significant at P = 0.1.

Age, duration of stay at camp, toothbrushing frequency and attending a dental clinic in the last year, were found to be significant in the univariable analyses, and were incorporated into a multivariable linear regression analysis. The assumption of the multivariable regression analysis was checked by a study of the residues and found to be satisfactory. The ANOVA was statistically significant (P < 0.001). Age, toothbrushing frequency and attending a dental clinic in the last year remained significant predictors of OHRQoL scores (Table 3).

Table 3.

Multivariable linear regression analyses of variables significant in the univariable analyses

| Model | Coefficient | P-value | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | −0.144 | 0.048* | −0.28 to −0.001 |

| Duration of stay at camp | 1.24 | 0.116 | −0.314 to 2.78 |

| Toothbrushing frequency (no/rarely or at least once a day) | 7.06 | 0.001* | 2.96 to 11.17 |

| Attending a dental clinic in the last year (no or yes) | 3.71 | 0.004* | 1.21 to 6.21 |

Dependent variable: OHRQoL-UK total scores. Predictors: age, duration of stay at camp, toothbrushing frequency (no/rarely or at least once a day) and attending a dental clinic in the last year (no or yes).

Statistically significant at P = 0.05.

DISCUSSION

This study is the first to examine factors associated with OHRQoL among Syrian refugees. It revealed the negative impact of poor oral health on the physical aspects of the refugees’ quality of life, and the positive relationship between regular toothbrushing and dental clinic attendance on the refugees’ OHRQoL.

Refugee populations suffer from poor oral health relative to that of the populations in their host countries13, 14, 15. Two of the main factors affecting oral health are oral hygiene practices and access to preventive/restorative dental care24. A study conducted in Somali refugees in Massachusetts found poor oral health to be associated with low utilisation of oral hygiene practices and poor access to preventive care25. The current study found that a relatively high percentage of the refugees (12.7%) were not brushing their teeth. This result was similar to that reported in a study of Middle Eastern and African refugees in Norway, in which toothbrushing was a daily habit for all the African refugees, whereas 13.4% of the Middle Eastern refugees did not brush their teeth at all14, and in contrast to a study of Hmong adult refugees in the USA, which reported that fewer than 1% did not brush their teeth26.

The lack of use of any adjunctive dental cleaning methods was reported by the majority of the sample in the current study. This was consistent with the study in Norway, for which only 5.3% reported the use of dental floss14. The use of dental floss was also reported to be rare among the Dinka and Nuer refugees from Sudan residing in the USA; however, they reported the use of toothpicks to be a common practice27. Toothpicks were the most commonly used adjunctive method in the current study.

Some of the participants in the current study could be considered as relatively newly arrived refugees and therefore might be preoccupied with settling in the camp, and not prioritising or paying attention to their oral hygiene28. These practices could also be a result of original cultural behaviours25, and the lack of acculturation of refugees residing in camps, compared with those residing within the communities of the host countries29. Stress and psychological trauma could also have impacted oral hygiene behaviours28, 30.

About half of the sample of refugees did not attend a dental clinic in the last year. Failure of refugees to attend a dental clinic regularly for treatment or an evaluation, could be a result of insufficient access to dental care31, the refugees themselves not prioritising their oral health28, lack of awareness of the health services provided32 or general cultural behaviours29. Access to oral health care is a major factor which could affect oral health33 and therefore could impact OHRQoL34. In Azraq camp, access could be considered as limited because of the small number of clinics serving a large population of refugees. A cross-sectional study in Al-Zaatari camp found that 75% of the sample of refugees reported that they received insufficient health care12. Unfortunately, oral health programmes within refugee camps are usually of low priority35. A recommendation must be made that the host countries address known barriers to preventive and restorative dental care15. In addition, other factors affecting regular dental attendance by refugee populations residing in camps should be assessed.

The Arabic version of the OHRQoL-UK measure was used when trying to understand the impact of oral health on the Syrian refugees residing in the Azraq camp. This measure was validated in a Syrian population22. It is based on the more recently revised World Health Organization (WHO) model of health: ‘structure–function–activity–participation’. Therefore, it has the unique ability to measure the positive, as well as the negative, aspects of participants’ perceptions of oral health, in contrast to other tools that are only capable of detecting the negative aspects36. This is important because oral health could have a positive impact on quality of life and not necessarily a negative one37.

After analysing the scores reported for the OHRQoL-UK measure in our study, it was found that the physical aspect was more negatively impacted than the psychological aspect. This could be because the refugees’ psychological state was severely affected by other factors, such as the traumatic events they experienced. Therefore, the oral health impact on their psychology would not have been a primary factor affecting their quality of life28.

Studies assessing the impact of oral health on the quality of life of refugees are scarce. Two studies which assessed the impact of oral health on the psychological stress levels and quality of sleep of the refugees found a correlation between caries experience and stress indicators38, 39. A study of the impact of oral health on daily life in Middle Eastern and African refugees in Norway found that half of the participants reported one or more negative impacts on daily life at least once weekly as a result of dental problems14. Negative impact of oral health on sleep/relaxation and social activities were reported significantly more by Middle Eastern refugees than by African refugees14. Another study which assessed the OHRQoL in the children of Syrian refugees through interviewing their parents, found poor oral health in children (especially dental pain) to negatively impact the children’s quality of life, and was associated with anger and frustration experienced by the children and their parents40.

In the current study, the majority of the refugees perceived their oral health to have a negative impact on their quality of life in the areas related to enjoyment of food, comfort and the ability to do work. On the other hand, areas such as personality, confidence, general health, speech, social activities, romantic relationships, smiling, happiness, appearance and lack of worry, were rated by the majority of the refugees to be less negatively affected by their oral health. These observations show some differences from reports in the literature. In a study which used the OHRQoL-UK measure, it was found that the UK public perceived their oral health to influence their quality of life primarily through appearance, followed by lack of pain and eating41. In other studies in the literature, concerns about aesthetics were prioritised by patients over the functioning of the dentition, such as biting and chewing42, 43. In a study which investigated the dental treatments that a refugee population wished to have, the participants listed conditions which are not often of concern to western populations27. This highlights the different dental needs of refugee populations from different cultural backgrounds, compared with the populations in the host countries13.

Edentulous patients were excluded from the current study. Had they been included, the psychological and social domains may have shown a more negative impact. However, as this population of patients generally have different clinical needs and different functional, aesthetic and psychological concerns, it would be rather difficult to compare them with dentate patients. Moreover, studies have shown that edentulous patients suffer from significantly lower OHRQoL than do dentate patients, and would be best assessed with a population-specific OHRQoL measure21.

Of the social demographic factors tested for association with OHRQoL scores, only age was found to be significantly associated with OHRQoL. The older the individual, the more his/her quality of life was negatively affected by oral health. However, the degree of negative correlation was slight. In a study which employed the OHRQoL-UK measure on the UK public, older people were more likely to have reduced OHRQoL scores41. This could be a result of the physiological oral changes and deterioration in oral function caused by chronic oral disease41, 44.

In the current study, OHRQoL scores did not seem to be affected by gender. As part of a literature review conducted to determine the association between social factors and OHRQoL, it was concluded that female subjects tended to perceive their oral health to have greater impact (positive or negative) on their quality of life than male subjects45. However, none of the studies in the review had samples that could be directly compared with a refugee population. Another explanation could be the extreme conditions that both male and female refugees experience, which might have masked any marginal differences between them regarding OHRQoL.

Duration of stay at the camp was found to be positively correlated with OHRQoL scores in the univariable analysis, but become insignificant when accounting for the other factors in the multivariable analysis. Those who recently arrived at the camp seemed to report lower OHRQoL scores. This may have been because of a lack of access to emergency dental services during the transition period and resettlement in the camp28. A number of studies have reported an association between smoking and oral health46, 47. In the current study, smoking did not seem to have an impact on OHRQoL scores.

The association between oral hygiene practices and OHRQoL was also examined. In a study on the Hmong refugee population in the USA, frequency of toothbrushing was found to be associated with better self-reported oral health. In the current study, those who brushed their teeth were likely to report a score 7.06 points higher than those who did not brush their teeth (95% CI: 2.96–11.17, P = 0.001). Poor individual oral hygiene practices were reported to contribute to poor oral health outcomes25, 28.

Attending a dental clinic in the last year was found to be a significant predictor of OHRQoL scores. Those who attended a dental clinic at least once in the last year were likely to report a score 3.71 points higher than those who did not attend (95% CI: 1.21–6.21, P = 0.004). This was not unexpected because regular dental attendance would provide the opportunity for prevention, early diagnosis and prompt intervention48. This was consistent with studies in the literature, which suggest that regular dental attenders have better oral health and OHRQoL than those who only visit a dentist when necessary49, 50, 51.

A limitation of the current study was the sample selection method. The sample was limited to refugees who were seeking dental treatment or a dental evaluation at the dental clinics in the camp. This could have affected the results of the study because the refugees attending the clinics could have been in dental pain and consequently rated items related to the physical domain more negatively. Therefore, how this sample would relate to the rest of the refugee population in the camp is not clear and is a limitation to the generalisability of these results. However, recruiting participants from hard-to-reach and restricted populations is acknowledged to be rather difficult15, 52. Conducting similar studies using different sample selection methods would be helpful in addressing this issue.

The current study provides good insight into the oral hygiene practices of the refugees and the areas of their quality of life impacted by their oral health, as well as the factors associated with it. Based on these findings, it is clear that improving access to dental care through increasing the resources allocated for oral health would help improve the quality of life of refugees. In addition, increasing awareness about the importance of oral hygiene practices and the services provided by the dental clinics available in the camp would help reduce the need for future dental treatment. As a result of the limited resources usually allocated to oral health35, providing emergency and restorative dental treatment to relieve dental pain and improve the physical functionality of the teeth should be prioritised in order to reduce the negative impact of oral health on the quality of life of refugees. Future research should further investigate the oral health needs and access to dental care of this population. Understanding the oral health needs of refugees would help in planning for essential interventions.

CONCLUSIONS

The physical aspects of quality of life seemed to be affected more than the psychological aspects by the oral health of the refugees. The negative impact of oral health was mainly observed in the refugees’ enjoyment of food, comfort and ability to do work. Toothbrushing and attending a dental clinic at least once a year seemed to be associated with higher OHRQoL scores. The older the individual, the more likely that their quality of life was negatively affected by their oral health.

Acknowledgements

Appreciation is expressed to Dr Sirin Shaban for her substantial input to this manuscript. No funding to declare.

Conflict of interest

None.

REFERENCES

- 1.Murphy A, Woodman M, Roberts B, et al. The neglected refugee crisis. BMJ (Clinical Research ed) 2016;352:i484. doi: 10.1136/bmj.i484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). Registered Syrian Refugees in Jordan [Internet]; 2018, July 29. Available from: https://data2.unhcr.org/en/situations/syria/location/36. Accessed 15 August 2018

- 3.United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). UNHCR Jordan Factsheet [Internet]; 2018, February. Available from: https://data2.unhcr.org/en/documents/details/62241. Accessed 15 August 2018

- 4.United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). Jordan Azraq Camp Factsheet [Internet]; 2018, April. Available from: https://data2.unhcr.org/en/documents/details/63538. Accessed 15 August 2018

- 5.United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). Jordan Factsheet: Zaatari Camp [Internet]; 2018, July 10. Available from: https://reliefweb.int/report/jordan/unhcr-jordan-factsheet-zaatari-camp-July-2018. Accessed 15 August 2018

- 6.United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). Emirati-Jordanian Camp Total Number of Concern [Internet]; 2018, July. Available from: https://data2.unhcr.org/en/situations/syria/location/41. Accessed 15 August 2018

- 7.El Arab R, Sagbakken M. Healthcare services for Syrian refugees in Jordan: a systematic review. Eur J Public Health. 2018;28:1079–1087. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/cky103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shrestha NM, Sharma B, Van Ommeren M, et al. Impact of torture on refugees displaced within the developing world: symptomatology among Bhutanese refugees in Nepal. JAMA. 1998;280:443–448. doi: 10.1001/jama.280.5.443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Eljedi A, Mikolajczyk RT, Kraemer A, et al. Health-related quality of life in diabetic patients and controls without diabetes in refugee camps in the Gaza strip: a cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health. 2006;6:268. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-6-268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ay M, Arcos González P, Castro DelgadoR. The perceived barriers of access to health care among a group of non-camp Syrian refugees in Jordan. Int J Health Serv. 2016;46:566–589. doi: 10.1177/0020731416636831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mollica RF, Donelan K, Tor S, et al. The effect of trauma and confinement on functional health and mental health status of Cambodians living in Thailand-Cambodia border camps. JAMA. 1993;270:581–586. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Al-Fahoum AS, Diomidous M, Mechili A, et al. The provision of health services in Jordan to Syrian refugees. Health Sci J. 2015;92:1. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Singh HK, Scott TE, Henshaw MM, et al. Oral health status of refugee torture survivors seeking care in the United States. Am J Public Health. 2008;98:2181–2182. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2007.120063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Høyvik AC, Lie B, Grjibovski AM, et al. Oral health challenges in refugees from the Middle East and Africa: a comparative study. J Immigr Minor Health. 2019;21:443–450. doi: 10.1007/s10903-018-0781-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Keboa MT, Hiles N, Macdonald ME. The oral health of refugees and asylum seekers: a scoping review. Global Health. 2016;12:59. doi: 10.1186/s12992-016-0200-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Van Berlaer G, Carbonell FB, Manantsoa S, et al. A refugee camp in the centre of Europe: clinical characteristics of asylum seekers arriving in Brussels. BMJ Open. 2016;6:e013963. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-013963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Okunseri C, Hodges JS, Born DO. Self-reported oral health perceptions of Somali adults in Minnesota: a pilot study. Int J Dent Hyg. 2008;6:114–118. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-5037.2008.00295.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Locker D. Measuring oral health: a conceptual framework. Community Dent Health. 1988;5:3–18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.High UN, Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). Azraq Health Information System Profile Report [Internet]; 2018, July. Available from: https://data2.unhcr.org/en/documents/details/64952. Accessed 15 August 2018

- 20.The United Nations Refugee Agency (UNHCR). Za’atri Public Health Profile [Internet]; 2018, March. Available from: https://reliefweb.int/report/jordan/zaatri-jordan-public-health-profile-second-quarter-2018-30-march-29-June-2018. Accessed 15 August 2018

- 21.McGrath C, Bedi R. An evaluation of a new measure of oral health related quality of life–OHQoL-UK (W) Community Dent Health. 2001;18:138–143. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McGrath C, Alkhatib MN, Al-Munif M, et al. Translation and validation of an Arabic version of the UK oral health related quality of life measure (OHQoL-UK) in Syria, Egypt and Saudi Arabia. Community Dent Health. 2003;20:241–245. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Corp IBM . IBM Corp; Armonk, NY: 2013. IBM SPSS statistics for windows, version 22.0. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Garcia RI, Cadoret CA, Henshaw M. Multicultural issues in oral health. Dent Clin North Am. 2008;52:319–332. doi: 10.1016/j.cden.2007.12.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Geltman PL, Adams JH, Cochran J, et al. The impact of functional health literacy and acculturation on the oral health status of Somali refugees living in Massachusetts. Am J Public Health. 2013;103:1516–1523. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2012.300885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Okunseri C, Yang M, Gonzalez C, et al. Hmong adults self-rated oral health: a pilot study. J Immigr Minor Health. 2008;10:81. doi: 10.1007/s10903-007-9054-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Willis MS, Bothun RM. Oral hygiene knowledge and practice among Dinka and Nuer from Sudan to the US. J Am Dent Hyg Assoc. 2011;85:306–315. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lamb CEF, Michaels C, Whelan AK. Refugees and oral health: lessons learned from stories of Hazara refugees. Aust Health Rev. 2009;33:618–627. doi: 10.1071/ah090618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Adams MJH, Young MS, Laird LD, et al. The cultural basis for oral health practices among Somali refugees pre-and post-resettlement in Massachusetts. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2013;24:1474. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2013.0154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kaplan I, Webster K. In: The Health of Refugees: Public Health Perspectives from Crisis to Settlement. Allote P, editor. Oxford University Press South Melbourne; New York: 2003. Refugee women and settlement: Gender and mental health; pp. 104–122. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Davidson N, Skull S, Calache H, et al. Equitable access to dental care for an at-risk group: a review of services for Australian refugees. Aust N Z J Public Health. 2007;31:73–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Flynn C. Healthcare Access for Syrian Refugees Lacking Legal Documentation in Jordan; 2016. Independent Study Project (ISP) Collection. 2372. Available from: https://digitalcollections.sit.edu/isp_collection/2372. Accessed 15 August 2018

- 33.Roucka TM. Access to dental care in two long-term refugee camps in western Tanzania; programme development and assessment. Int Dent J. 2011;61:109–115. doi: 10.1111/j.1875-595X.2011.00023.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Linden GJ, Lyons A, Scannapieco FA. Periodontal systemic associations: review of the evidence. J Periodontol. 2013;84:S8–S19. doi: 10.1902/jop.2013.1340010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ogunbodede EO, Mickenautsch S, Rudolph MJ. Oral health care in refugee situations: Liberian refugees in Ghana. J Refug Stud. 2000;13:328–335. [Google Scholar]

- 36.McGrath C, Bedi R, Gilthorpe MS. Oral health related quality of life–views of the public in the United Kingdom. Community Dent Health. 2000;17:3–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Abu-Awwad M, Hemmings K, Mannaa S, et al. Treatment outcomes and assessment of oral health related quality of life in treated Hypodontia patients. Eur J Prosthodont Restor Dent. 2017;25:49–56. doi: 10.1922/EJPRD_01586Abu-Awwad08. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Honkala E, Maidi D, Kolmakow S. Dental caries and stress among South African political refugees. Quintessence Int (Berl) 1992;23:579–583. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fox SH, Willis MS. Dental restorations for dinka and nuer refugees: a confluence of culture and healing. Transcult Psychiatry. 2010;47:452–472. doi: 10.1177/1363461510374559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pani SC, Al-Sibai SA, Rao AS, et al. Parental perception of oral health-related quality of life of Syrian refugee children. J Int Soc Prevent Commun Dentist. 2017;7:191. doi: 10.4103/jispcd.JISPCD_212_17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.McGrath C, Bedi R. Population based norming of the UK oral health related quality of life measure (OHQoL-UK) Br Dent J. 2002;193:521–524. doi: 10.1038/sj.bdj.4801616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Graham R, Mihaylov S, Jepson N, et al. Determining ‘need’ for a Removable Partial Denture: a qualitative study of factors that influence dentist provision and patient use. Br Dent J. 2006;200:155–158. doi: 10.1038/sj.bdj.4813193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Klages U, Bruckner A, Zentner A. Dental aesthetics, self-awareness, and oral health-related quality of life in young adults. Eur J Orthod. 2004;26:507–514. doi: 10.1093/ejo/26.5.507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Slade GD, Spencer AJ, Locker D, et al. Variations in the social impact of oral conditions among older adults in South Australia, Ontario, and North Carolina. J Dent Res. 1996;75:1439–1450. doi: 10.1177/00220345960750070301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Cohen-Carneiro F, Souza-Santos R, Rebelo MA. Quality of life related to oral health: contribution from social factors. Cien Saude Colet. 2011;16:1007–1015. doi: 10.1590/s1413-81232011000700033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Millar WJ, Locker D. Smoking and oral health status. J Can Dent Assoc. 2007;73:155. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Locker D. Smoking and oral health in older adults. Can J Public Health. 1992;83:429–432. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Amarasena N, Kapellas K, Skilton MR, et al. Factors associated with routine dental attendance among aboriginal Australians. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2016;27:67–80. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2016.0040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Thomson WM, Williams SM, Broadbent JM, et al. Long-term dental visiting patterns and adult oral health. J Dent Res. 2010;89:307–311. doi: 10.1177/0022034509356779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Davenport CF, Elley KM, Fry-Smith A, Taylor-Weetman CL, Taylor RS. The effectiveness of routine dental checks: a systematic review of the evidence base. Br Dent J. 2003;195:87–98. doi: 10.1038/sj.bdj.4810337. discussion 85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.McGrath C, Bedi R. Can dental attendance improve quality of life? Br Dent J. 2001;190:262–265. doi: 10.1038/sj.bdj.4800944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Méndez M, Font J. Amsterdam University Press; Amsterdam: 2013. Surveying ethnic minorities and immigrant populations: methodological challenges and research strategies. Available from: https://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt6wp7d2.4. Accessed 15 August 2018. [Google Scholar]