Abstract

TGF‐β signaling is a key player in tumor progression and immune evasion, and is associated with poor response to cancer immunotherapies. Here, we identified ubiquitin‐specific peptidase 8 (USP8) as a metastasis enhancer and a highly active deubiquitinase in aggressive breast tumors. USP8 acts both as a cancer stemness‐promoting factor and an activator of the TGF‐β/SMAD signaling pathway. USP8 directly deubiquitinates and stabilizes the type II TGF‐β receptor TβRII, leading to its increased expression in the plasma membrane and in tumor‐derived extracellular vesicles (TEVs). Increased USP8 activity was observed in patients resistant to neoadjuvant chemotherapies. USP8 promotes TGF‐β/SMAD‐induced epithelial‐mesenchymal transition (EMT), invasion, and metastasis in tumor cells. USP8 expression also enables TβRII+ circulating extracellular vesicles (crEVs) to induce T cell exhaustion and chemoimmunotherapy resistance. Pharmacological inhibition of USP8 antagonizes TGF‐β/SMAD signaling, and reduces TβRII stability and the number of TβRII+ crEVs to prevent CD8+ T cell exhaustion and to reactivate anti‐tumor immunity. Our findings not only reveal a novel mechanism whereby USP8 regulates the cancer microenvironment but also demonstrate the therapeutic advantages of engineering USP8 inhibitors to simultaneously suppress metastasis and improve the efficacy of cancer immunotherapy.

Keywords: cancer immunotherapy, deubiquitinase, metastasis, TβRII, USP8

Subject Categories: Cancer, Immunology, Molecular Biology of Disease

A novel mechanism of cancer microenvironment regulation by the drug‐targetable deubiquitinase USP8 offers the possibility of simultaneously suppressing metastasis and improving immunotherapy efficacy.

Introduction

Transforming growth factor‐β (TGF‐β) is a cytostatic factor expressed in premalignant tumor cells but frequently switches to a prometastatic factor during the later stages of cancers (Moustakas et al, 2001; Kang et al, 2009; Ikushima & Miyazono, 2010; Zhang et al, 2013b). The mechanism by which this occurs is not well understood. Upon ligand binding, the TGF‐β type II serine/threonine kinase receptor (TβRII) activates the type I receptor (TβRI), which subsequently induces SMAD2/3 phosphorylation. Activated SMAD2/3 forms hetero‐oligomers with SMAD4 and accumulates in the nucleus to regulate the expression of target genes (Moustakas et al, 2001; Kang et al, 2009; Ikushima & Miyazono, 2010; Zhang et al, 2013b).

Ubiquitination of proteins can be reversed by deubiquitinase (DUB), a proteome made up of 90 members encoded by the human genome (Nijman et al, 2005; Nakada et al, 2010; Yuan et al, 2010; Williams et al, 2011). During TGF‐β signaling, SMAD7 recruits E3 ubiquitin ligase SMURF2 to activate TβRI and targets TβRI for ubiquitination and degradation. The latter process is known to be counteracted by ubiquitin‐specific peptidase 4 (USP4) and USP15 (Eichhorn et al, 2012; Zhang et al, 2012b). In contrast to TβRI, TβRII appears to be more unstable (Tang et al, 2011) and the stability and membrane localisation of TβRII are critical determinants of the sensitivity and duration of the TGF‐β signaling response. However, whether TβRII is also regulated by DUBs in cancer remains unclear.

Extracellular vesicles (EVs) are small (30–150 nm in diameter) membrane‐bound vesicles released into the extracellular milieu by various types of cells (Thery et al, 2002; Colombo et al, 2014). They contain functional biomolecules (proteins, lipids, RNA, and DNA) that can be horizontally transferred to recipient cells (Valadi et al, 2007; Cocucci et al, 2009; Melo et al, 2014; Thakur et al, 2014; Zhou et al, 2014). We found that TβRII was abundant and specifically enriched in EVs from the highly metastatic breast cancer cell and the triple‐negative breast cancer patients who failed to respond to these combined therapies. Given this fact, the inhibition of EV‐TβRII secretion is a critical factor for improving the efficacy of cancer therapies in the future. Here, we developed two new strategies for DUB screening and identified ubiquitin‐specific protease (USP) 8 as a metastasis enhancer. USP8 stimulates cancer stem cell traits and sustains metastatic growth via its binding to, and deubiquitination of, TβRII, improving its stability, particularly on the plasma membrane. Deubiquitination of TβRII facilitated by the frequent gain of USP8 function promotes TGF‐β/SMAD‐induced epithelial‐to‐mesenchymal transition (EMT), invasion, and metastasis of tumor cells, while increasing the secretion of TβRII+ crEVs enhances anti‐tumor T cell exhaustion in the host. This mechanism allows for the quick propagation of in vivo metastatic nodules that also confer chemoimmunotherapeutic resistance. In view of the vital influence of USP8 on cancer, we synthesized and validated a small‐molecule inhibitor of USP8 and demonstrated that this inhibitor efficiently reduced the stability of TβRII and the number of TβRII+ crEVs in the system. This prevents CD8+ T cell exhaustion and supports the re‐establishment of anti‐tumor responses by immune checkpoint inhibitors, leading to reduced tumor size and metastasis both in vitro and in vivo. These results suggest that USP8 may serve as a novel drug target and provide a strategy for improving the efficacy of breast cancer immunotherapy.

Results

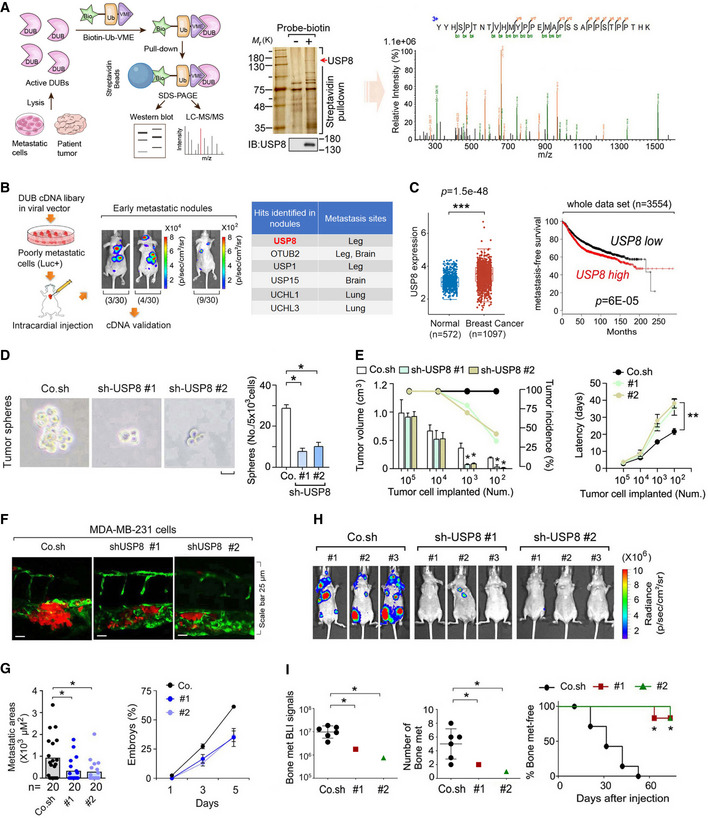

In vivo screening identified USP8 as a metastasis enhancer

We performed a DUB screening to identify the active DUBs linked to breast cancer metastasis. This workflow was designed to systematically profile active DUBs using a biotin‐Ub‐VME‐Ub‐based probe with a biotin label at the N terminus and a reactive vinyl methyl ester (VME) warhead that covalently binds to the catalytic cysteine in the C‐terminus of active DUBs. When this system was applied to metastatic breast tumor cells, the DUB probe pull down and subsequent identification by liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry (LC/MS–MS) revealed a panel of active DUBs (Liu et al, 2020). USP8 was shown to be highlighted in this panel and was scored as a significant prospect (Figs 1A and EV1A). A more extensive analysis further revealed that USP8 was more active in aggressive basal‐like breast cancer cells than in the less aggressive luminal‐like cells (Fig EV1B), and the analysis of primary and metastatic tissues from clinical samples demonstrated that USP8 activity was increased in the metastatic tumors (Fig EV1B), indicating that USP8 may contribute to metastasis.

Fig 1. In vivo screening identifies USP8 as a metastasis enhancer.

-

AFlow chart of an in vivo screen to identify active DUBs by using biotin‐Ub‐VME pull‐down assay (left panel), in which the USP8 peptide was identified by mass spectrometry analysis (right panel). Silver staining and immunoblot (middle panel) of precipitants pulled down by biotin‐Ub‐VME probe of MDA‐MB‐231 cells.

-

BExperimental procedure in vivo: flow chart and pictures of an in vivo screen to identify DUBs that promote breast cancer metastasis in mice (left panel). Low metastatic MDA‐MB‐231‐Luciferase/GFP breast cancer cells were infected with viral vectors expressing the DUB cDNAs and subsequently intracardially injected into nude mice. The mice were monitored for 4 weeks by in vivo BLI: of the 30 mice injected with cells expressing the DUB cDNA pool; 3 had metastases in the brain and bone (3/30), 4 had metastases on the back and in the bone (4/30), and 9 had micrometastasis (9/30); the 30 mice injected with control cells showed no detectable metastasis (30/30). Right panel: hints of the identified DUBs were shown.

-

CThe expression distribution of USP8 gene in breast cancer tumor tissues (n = 1,097) and normal tissues (n = 572), where the horizontal axis represents different groups of samples, the vertical axis represents the gene expression distribution (left panel). The box‐and‐whisker plots represent the medians (middle line), first quartiles (lower bound line), third quartiles (upper bound line), and the ±1.5× interquartile ranges (whisker lines). Kaplan–Meier curves show the metastasis‐free survival of individuals was negatively correlated with USP8 expression by log‐rank test (right panel).

-

DMCF10A‐RAS cells infected with control (Co.sh) or USP8 shRNA lentivirus (# 1 and # 2) were analyzed in a tumor sphere assay. The number of mammospheres with a diameter > 60 μm was quantified. The graph shows the number (No.) of tumor spheres per 5 × 103 cells seeded. Scale bar 50 μm.

-

EMCF10A‐RAS cells infected with control (Co.sh) or USP8 shRNA lentivirus (# 1 and # 2) were subcutaneously injected into nude mice at the indicated numbers. Mean of tumor volumes at week 5 (n = 10 mice for each group).

-

FMicroscopy pictures of representative images of zebrafish tail fin injected with control or USP8 stably depleted MDA‐MB‐231 cells at 5 days postinjection, n = 20 for each group.

-

GThe final invasive areas of zebrafish embryos displaying invasion and experimental metastasis at 5 dpi (left panel); Percentage of embryos injected with control or USP8 stably depleted MDA‐MB‐231 cells (# 1 and # 2) displaying metastasis at 1, 3, and 5 days postinjection (right panel).

-

HBioluminescent images of three representative mice from each group (n = 6) at week 6 were injected into left heart ventricle with control or MDA‐MB‐231 cells stably depleted of endogenous USP8 with two independent shRNA (# 1 and # 2).

-

IBLI signal (left panel), number of bone metastasis of every mouse (middle panel), and the percentage of bone metastasis‐free mice in each experimental group (n = 6 mice per group) followed in time as in (H) (right panel).

Data information: *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, (two‐tailed Student's t‐test (C (left), D, E (left), G (left), I (left, middle)) or two‐way ANOVA (C (right), E (right), I (right))). Data are analyzed of three independent experiments and shown as mean + SD (D, E (left)) or as mean ± SD (E (right), G, I (left, middle)).

Source data are available online for this figure.

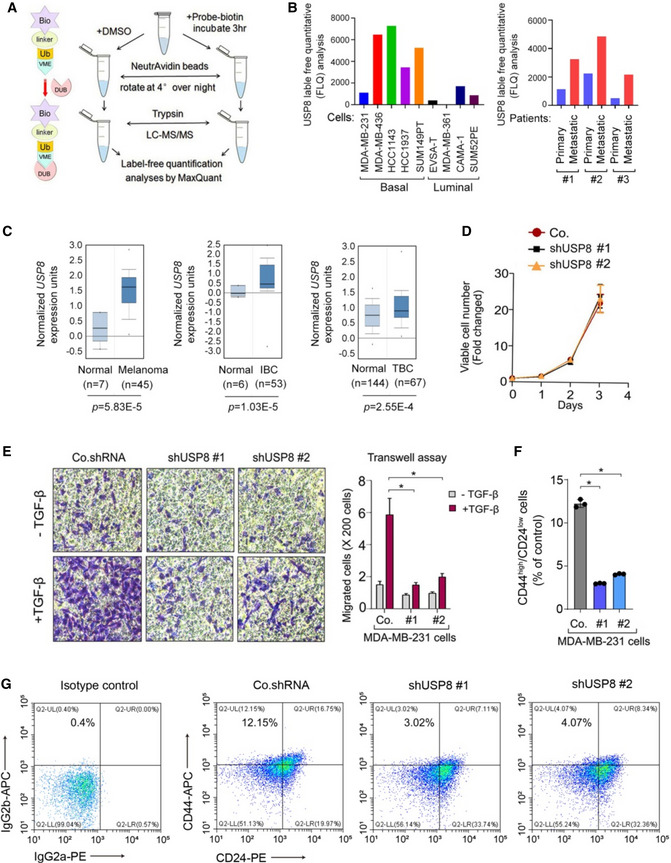

Fig EV1. A gain of function screen identifies USP8 as a metastasis‐activator.

- DUB activity profiling in cells by using biotin‐Ub‐VME pull‐down assay.

- Biotin ABP analysis of USP8 in breast cancer cell lines (left) and patients tumor samples (right).

- Oncomine data analysis of USP8 expression in Melanoma, IBC (Invasive Breast Carcinoma), TBC (Tubular Breast Carcinoma) vs. normal tissues.

- Viable cell number counts in control (Co.) and USP8 stably depleted‐MDA‐MB‐231 cells (with two independent shRNA: #1 and #2).

- Left panel: representative pictures of transwell assay performed in control or USP8 stably depleted‐MCF10A‐RAS (MII) cells. Quantification of migrated cells was shown in the right panel.

- Quantification of the CD44high/CD24low population in control (Co.) and USP8 stably depleted‐MDA‐MB‐231 cells (with two independent shRNA: #1 and #2) (n = 3 per group).

- A representative flow cytometric analysis of control (Co.) and USP8 stably depleted‐MDA‐MB‐231 cells (with two independent shRNA: #1 and #2) stained for CD24 and CD44.

Data information: *P < 0.05 (two‐tailed Student’s t test (C, E, F)). Data are shown as mean + SD (E) or as means ± SD (C, D, F).

Further, we performed another in vivo DUB cDNA library screen (Sowa et al, 2009) to identify other candidates associated with increased metastasis (Zhang et al, 2019). This assay produced more than 70 distinct DUB cDNA‐expressing MDA‐MB‐231 stable cell lines, which were mixed and introduced into nude mice using intracardial injection. Subsequent validation revealed that the nodules obtained in this assay produced large quantities of active USP8, confirming that USP8 may act as a tumor promoter in vivo (Fig 1B). In addition, TCGA and oncomine expression analyses of multiple databases revealed that USP8 was significantly upregulated in human breast cancers and melanoma (Fig 1C, left panel and Fig EV1C), and in a large public clinical microarray database of human breast tumors, we found a trend towards poor prognosis for the USP8‐high patients (Fig 1C, right panel).

We then examined the role of USP8 in the phenotypic behavior of breast cancer cells. Because metastasis is intimately linked to the tumor‐initiating capacity of primary tumors (Chaffer & Weinberg, 2011), we compared the self‐renewal potential, as assayed by the capacity of USP8‐knockdown and USP8‐expressing cells to form and propagate mammospheres in vitro and to give rise to tumors in vivo. USP8 knockdown had no significant effect on breast cancer cell proliferation but inhibited their migratory capacity (Fig EV1D and E). When cultured in suspension, knockdown of USP8 in RAS‐transformed MCF10A (MII) cells sharply reduced the number of tumor‐like mammospheres formed in vitro (Fig 1D), suggesting that USP8 promotes stemness in breast cancer cells. Next, we used fluorescence‐activated cell sorting (FACS) to assess specific stem cell markers CD44 and CD24 in MDA‐MB‐231 breast cancer cells. Stable knockdown of USP8 induced en masse reduction in the CD44high/CD24low population (Fig EV1F and G), suggesting that USP8 can induce the stem cell characteristics of breast cancer cells. We subsequently examined the supporting effect of USP8 expression on cancer stemness in vivo via the subcutaneous injection. USP8 knockdown was found to reduce tumor incidence and tumor growth, and prolonged the latency of a limited number of MCF10A‐RAS cells after their injection in mice (Fig 1E), indicating that this protein is required for cancer stemness.

To confirm the role of USP8 in cancer metastasis, we examined the effect of USP8 misexpression in vivo using a zebrafish embryo xenograft invasion model and a mouse xenograft metastasis model (Zhang et al, 2012b). USP8‐depleted MDA‐MB‐231 cells were injected into the ducts of Cuvier 48 h postfertilization (hpf) and analyzed over the next 5 days. Knockdown of USP8 by two independent shRNAs significantly reduced both the invasive cell area and the percentage of embryos showing invasion (Fig 1F and G). Moreover, while mice injected intracardially with control MDA‐MB‐231 cells began to develop detectable bone metastasis after 4 weeks, mice injected with two different USP8 knockdown clones developed fewer bone metastases after 8 weeks and had significantly longer bone metastasis‐free survival periods (Fig 1H and I), corroborating the strong prometastatic effect of USP8. Taken together, these data indicate that USP8 promotes cancer stemness and metastasis both in vitro and in vivo.

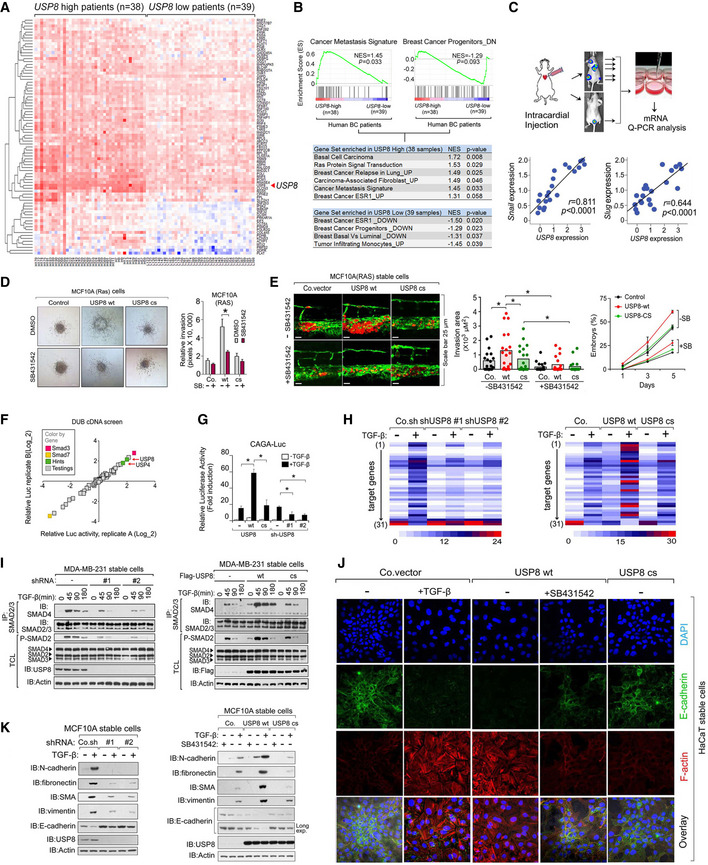

USP8 is a critical component in TGF‐β signaling

We next examined USP8 expression patterns in publicly available microarray datasets in an effort to establish whether the USP8‐induced promotion of metastasis, described above, influences the pathogenesis of human breast cancers. Gene‐set enrichment analysis (GSEA) of the NKI295 breast cancer patient dataset showed that gene signatures representing increased cancer metastasis were significantly enriched in patients with higher levels of USP8 (n = 38) when compared to these signatures in patients with lower levels of USP8 expression (n = 39), strongly indicating that USP8 expression correlates with breast cancer progression and poor prognosis (Fig 2A and B; Appendix Table S1). To identify the effects of USP8 on the cancer cell transcriptome, we performed qPCR analysis using cells isolated from metastatic nodules and found that USP8 expression correlates with the increased expression of several TGF‐β target genes involved in cancer cell invasion and metastasis, including Snai1 and Snai2 (Slug) (Fig 2C and Appendix Fig S1A), suggesting that USP8 may positively regulate TGF‐β signaling. Immunoblot analysis confirmed that the induction of Snail by TGF‐β could be further enhanced by USP8 wild‐type (wt), but not by USP8 cs (carrying a point mutation in C786, one of the key cysteine residues of the catalytic domain), and impaired upon USP8 depletion (Appendix Fig S1B). These observations indicate that USP8‐induced enhancement of cancer cell invasion and metastasis may be a result of increased TGF‐β signaling activation.

Fig 2. USP8 is a critical component of TGF‐β signaling.

-

AHeatmap of USP8‐correlated genes in a comparison of breast cancer patients with USP8‐high (n = 38) versus with USP8‐low (n = 39).

-

BPreranked gene‐set enrichment analysis (GSEA) in USP8‐high (n = 38) versus USP8‐low (n = 39) breast cancer patients.

-

CExperimental procedure in vivo: MDA‐MB‐231 cells were intracardially injected into nude mice (n = 10). qRT–PCR analysis of bone metastatic cells showing the correlations between USP8 and Snai1 or Snai2 (Slug) in cells isolated from multiple metastatic nodules (n = 21) from mice.

-

D3D spheroid invasion assay of MCF10A‐Ras cells showing USP8 wt increased TGF‐β‐induced invasion. The relative invasion was quantified and shown in the right panel.

-

EMCF10A‐Ras cells stably expressing control vector (Co.vec), USP8 wt, or USP8 cs were injected into the blood circulation of 48‐hpf zebrafish embryos. SB431542 (5 μM) was added to the zebrafish environment. Representative images of zebrafish at 5 dpi (left panel); the experimental metastatic areas (middle panel) and percentage of embryos showing metastasis (right panel) are shown, n = 20.

-

FDiagram of DUB cDNA screening data of TGF‐β‐induced SMAD3/ SMAD4‐dependent CAGA12‐Luc transcriptional reporter in HEK293T cells. The X‐ and Y‐axes are the relative luciferase activity in two replicates.

-

GCAGA12‐Luc transcriptional response of HEK293T cells transfected with USP8 wt/cs or shUSP8 (#1 and #2) as indicated and treated with TGF‐β (1 ng/ml) overnight.

-

HHeatmap of TGF‐β target genes by qRT–PCR analysis in control or MCF10A‐RAS cells stably depleting USP8 (#1 and #2 shRNA) or expressing USP8 wt/cs and treated with or without TGF‐β (2.5 ng/ml) for 8 h. Appendix Table S2 for details.

-

IImmunoblot analysis of total cell lysates, immunoprecipitates derived from control and USP8 stably depleted (#1 and #2 shRNA) (left panel) and USP8 wt/cs overexpressed (right panel) MDA‐MB‐231 cells treated with TGF‐β (2.5 ng/ml) for indicated time points.

-

JImmunofluorescence and 4, 6‐diamidino‐2‐phenylindole (DAPI) staining of HaCaT cells infected with control or USP8 wt/cs and treated with TGF‐β (2.5 ng/ml) and SB431542 (10 μM) for 72 h. Scale bar, 20 μm.

-

KImmunoblot analysis of cell lysate of control and USP8 stably depleted‐MCF10AR‐RAS (MII) cells treated with TGF‐β (5 ng/ml) for 48 h (left); Immunoblot analysis of cell lysate of control and USP8 wt or USP8 cs stably expressed‐MCF10AR‐RAS (MII) cells treated with TGF‐β (5 ng/ml) or SB431542 (10 μM) for 48 h (right).

Data information: *P < 0.05 (two‐tailed Student's t‐test (D, E (middle), G) or two‐way ANOVA (C, E (right), F)). Data are representative of at least three independent experiments and shown as mean + SD (D (right), G); Data are shown as mean ± SD (E (right)).

Source data are available online for this figure.

Given these results, we then examined the role of USP8 in TGF‐β‐induced enhancement of cancer cell stemness and metastasis. In a 3D cultured spheroid assay, USP8 wt, but not USP8 cs, promoted cancer cell invasion, which was attenuated by SB431542, a TβRI kinase inhibitor (Fig 2D). We then used a zebrafish model to link USP8‐potentiated metastasis to TGF‐β/SMAD activation in vivo. MCF10A‐Ras cells, which demonstrate intermediate aggressive behavior, were injected into the blood circulation of embryonic zebrafish; the fish were evaluated 5 days later, which revealed a marked increase in MCF10A‐Ras cell invasion in response to ectopic USP8 wt but no change in response to USP8 cs. In addition, treatment with SB431542 reduced invasion in all samples (Fig 2E). We then performed a screening process using a DUB cDNA library via a TGF‐β/SMAD transcriptional reporter assay (Dennler et al, 1998) and found that USP8 markedly increased the activity of the transcriptional reporter (Fig 2F). In addition, USP8 cs did not potentiate TGF‐β signaling or target gene expression (Fig 2G and H), which was consistent with the previous results and indicates that its DUB activity is essential to these more aggressive phenotypes. Knockdown experiments demonstrated that USP8 is required for the proper TGF‐β‐induced transcription of target genes, and typical TGF‐β target genes are consistently dependent on USP8 expression (Fig 2G and H). Next, we investigated the effect of USP8 misexpression on TGF‐β‐induced SMAD signaling in parental MDA‐MB‐231 cells. Ectopic expression of USP8 wt, but not USP8 cs, increased the magnitude and duration of TGF‐β‐induced SMAD2 phosphorylation and SMAD2‐SMAD4 complex formation (Fig 2I), while the depletion of USP8 had the opposite effect (Fig 2I).

TGF‐β stimulates the epithelial‐to‐mesenchymal transition (EMT), migration, invasion, and metastasis of breast cancer cells (Brabletz, 2012; Burgess, 2013; De Craene & Berx, 2013). Typical EMT changes include the upregulation of N‐cadherin, fibronectin, smooth muscle actin, and vimentin, and downregulation of E‐cadherin. When grown in 2% plasma‐containing medium, HaCaT cells supplemented with USP8 wt, but not USP8 cs, developed actin stress fibers, increased expression of Vimentin, and showed the downregulation of the surface expression of E‐cadherin, similar to a TGF‐β‐treated phenotype; these morphological changes were inhibited following the addition of SB431542, a TβRI kinase inhibitor (Fig 2J and Appendix Fig S1C). PCR array analysis and immunoblot also showed TGF‐β‐induced changes in the expression of various EMT markers, which were then attenuated upon USP8 depletion, while the ectopic expression of USP8 wt, but not USP8 cs, had the opposite effect (Fig 2H and K). Taken together, these results support the hypothesis that USP8 activates TGF‐β signaling, thereby supporting EMT and contributing to cancer stemness and metastasis.

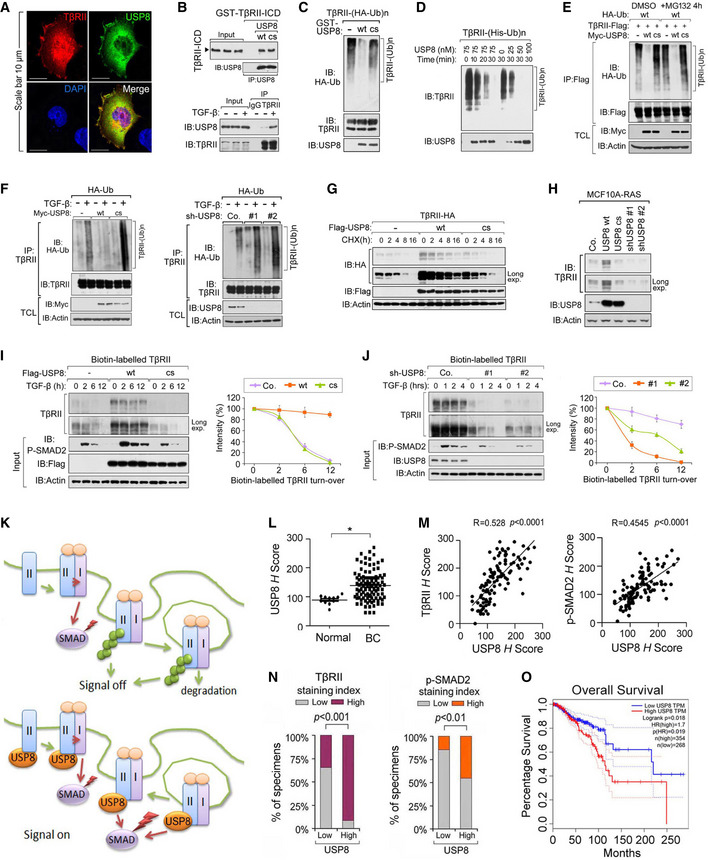

USP8 directly deubiquitinates and stabilizes TβRII at the plasma membrane

The findings described above suggest that USP8 acts as a TGF‐β pathway DUB upstream of R‐SMAD activation. USP8 co‐localized with TβRII at the cell surface (Fig 3A) and the intracellular domain of TβRII was found to associate directly with USP8 in vitro (Fig 3B). In nontransfected cells, the endogenous interaction between USP8 and TβRII was more efficient following TGF‐β stimulation (Fig 3B). Thus, USP8 is directly associated with TβRII. Of note, USP8 wt‐associated TβRII was not ubiquitinated, while USP8 cs‐associated TβRII was highly ubiquitinated (Appendix Fig S2A). Given this fact, we went on to examine whether USP8 serves as a DUB for TβRII. Flag‐tagged TβRII proteins were affinity purified, and their ubiquitination patterns were visualized using HA–ubiquitin immunoblotting. Polyubiquitination appeared as a major modification of TβRII. To demonstrate that USP8 directly deubiquitinates TβRII, we first performed an in vitro deubiquitination assay. Purified glutathione S‐transferase (GST)‐USP8 wt, but not GST‐USP8 cs, removed polyubiquitin chains from TβRII (Fig 3C). When an optimal concentration of USP8 was applied, 50% of the polyubiquitinated TβRII was cleaved within 25 min, suggesting that polyubiquitinated TβRII is a substrate for USP8 (Fig 3D). In cells, overexpression of USP8 wt, but not USP8 cs, inhibited TβRII polyubiquitination both in the presence and absence of the proteasome inhibitor MG132 (Fig 3E). Ectopic expression of USP8 wt, but not the USP8 cs mutant, inhibited TGF‐β‐induced TβRII ubiquitination at the endogenous level (Fig 3F). Conversely, USP8 depletion enhanced TGF‐β‐induced polyubiquitination of endogenous TβRII (Fig 3F). In addition, polyubiquitination of TGF‐β receptors has been reported to promote its internalization and degradation (Di Guglielmo et al, 2003). Co‐expressed USP8 wt but not USP8 cs increased the half‐life of TβRII (Fig 3G), while in breast cancer cells, endogenous TβRII accumulated in USP8 wt‐expressing cells and disappeared following USP8 depletion (Fig 3H). Therefore, we investigated whether USP8 regulates the TβRII levels at the plasma membrane, where the TGF‐β signal is initiated. Upon ectopic expression of USP8 wt, but not USP8 cs, biotin‐labeled cell surface TβRII displayed an elevated basal expression and a prolonged half‐life (Fig 3I). In comparison, USP8 depletion correlated with a much lower cell surface level of TβRII and accelerated TβRII turnover (Fig 3J). These findings suggest that USP8 is a DUB for TβRII and is essential in maintaining the stability of TβRII in the plasma membrane (Fig 3K).

Fig 3. USP8 directly deubiquitinates TβRII and stabilizes TβRII at the plasma membrane.

-

AImmunofluorescence and DAPI staining of HeLa cells transfected with TβRII‐HA and Flag‐USP8. Scale bar, 10 μm.

-

BUSP8 interacts with TβRII. Purified prokaryotically expressed USP8 and recombinant GST‐TβRII‐ICD were incubated in vitro and immunoprecipitated with anti‐USP8 antibody; immunoprecipitates were then immunoblotted for TβRII‐ICD and USP8 (top panel); Immunoblot analysis of total cell lysate derived from MDA‐MB‐231 cells treated with TGF‐β as indicated and immunoprecipitated with control IgG (ns) or anti‐TβRII antibody (bottom panel).

-

CImmunoblot analysis of anti‐TβRII immunoprecipitates from HEK293T cells stably expressing HA‐Ub and in vitro incubated with purified USP8 wt/cs.

-

DIB of Nickle‐pull down precipitants derived from His‐Ub stably expressed HEK293T cells incubated with purified USP8 protein as indicated time points.

-

EIB of TCL and immunoprecipitants derived from HEK293T cells transfected with indicated plasmids and treated with or without MG132 (10 μM) for 4 h.

-

FIB of TCL and immunoprecipitants derived from HA‐Ub stably expressed HEK293T cells transfected with Myc‐USP8 wt/cs (left panel) or infected with control (Co.sh) or USP8 shRNA lentivirus (#1 and #2) (right panel) and treated with TGF‐β (5 ng/ml) as indicated.

-

GIB of HeLa cells stably expressing TβRII‐HA and transfected with control empty vector (Co.vector) and Flag‐USP8 wt/cs plasmids and treated with CHX (20 μg/ml) for indicated time points.

-

HImmunoblot analysis of MCF10A‐RAS cells stably expressing USP8 wt/cs or USP8 shRNA (#1 and #2).

-

IImmunoblot analysis of biotinylated TβRII in MDA‐MB‐231 cells ectopically expressing USP8 wt/cs and treated with TGF‐β (5 ng/ml) as indicated (left panel). Quantification of the band intensities is shown in the right panel. Band intensity was normalized to the t = 0 controls (right panel). n = 2 technical replicates.

-

JImmunoblot analysis of biotinylated TβRII in MDA‐MB‐231 cells infected with lentivirus encoding control shRNA (Co.sh), USP8 shRNA (# 1 and # 2) and treated with TGF‐β (5 ng/ml) as indicated (left panel). Quantification of the band intensities is shown in right panel. Band intensity was normalized to the t = 0 controls (right panel). n = 2 technical replicates.

-

KWorking model in which USP8 deubiquitylates TβRII thus maintains cell surface level of TβRII that sustains SMAD activation.

-

LExpression of USP8 of normal tissues (n = 11) and breast cancer patients (n = 110). Data are mean ± s.e.m. P‐values from Student's t‐tests were indicated.

-

MScatter‐plot showing the positive correlation of USP8, TβRII, and p‐SMAD2 expression in patients (n = 110). H score of every tissue samples of USP8, TβRII, and p‐SMAD2 was calculated. Pearson's coefficient tests were performed to assess statistical significance.

-

NPercentage of specimens displaying low or high USP8 expression compared with the expression levels of TβRII and P‐SMAD2 in human breast cancer tissue (n = 110). P‐values from Student's t‐tests were indicated.

-

OGEPIA analysis curves showing the metastasis‐free survival of breast cancer patients was significantly correlated with USP8 expression by the log‐rank test in the TCGA and GTEx datasets (http://gepia.cancer‐pku.cn/). Cutoff‐high = 67%, cutoff‐low = 25%.

Data information: *P < 0.05 (two‐tailed Student's t‐test (L), two‐way ANOVA (I, J), Pearson's correlation test (M), log‐rank (O)). Data are shown as mean ± SD (I, J, L).

Source data are available online for this figure.

To determine the clinical relevance and validity of our findings in advanced human cancers, we examined the expression of TβRII and p‐SMAD2, and their relationship with USP8 in patient‐derived tissue samples. We performed IHC analysis on invasive breast carcinomas (110 cases), with tumor adjacent to normal breast tissue (11 cases) as controls. This analysis revealed that USP8, TβRII, and p‐SMAD2 were significantly upregulated in breast carcinomas and malignant tumors (stage I–III), when compared with normal breast tissues (NAT) (Fig 3L and Appendix Fig S2B and C). In addition, we observed a statistically significant correlation between USP8 and TβRII, USP8 and p‐SMAD2, and TβRII and p‐SMAD2 (Fig 3M and N, and Appendix Fig S2D–F), which was also consistent with our previous results. In the Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) database, high USP8 expression was associated with poor patient survival (Fig 3O). These findings confirmed our hypothesis that TβRII and TGF‐β/SMAD signaling are tightly regulated by USP8 in human cancers.

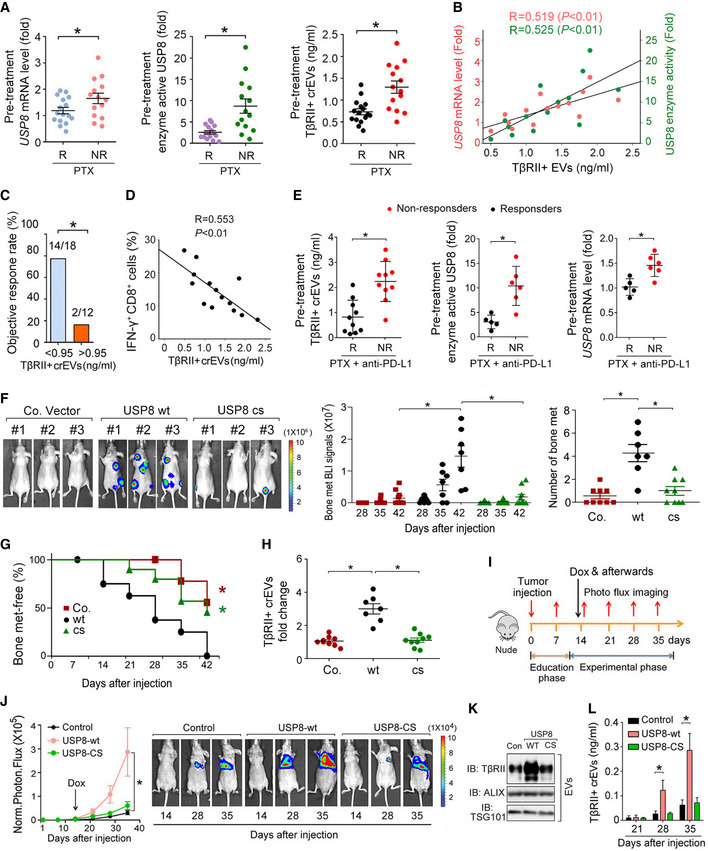

Gain of USP8 function promotes the secretion of EV‐TβRII and metastasis

We then investigated the clinical relevance of USP8 expression in breast cancer therapy. Resistance to neoadjuvant chemotherapies, such as paclitaxel (PTX) (Zardavas & Piccart, 2015), has been reported to facilitate breast cancer intravasation in primary tumors and extravasation to metastatic sites (DeMichele et al, 2017; Karagiannis et al, 2017). Interestingly, the pretreatment mRNA levels of USP8 and USP8 enzyme activity in patient‐derived tissue samples were found to be significantly higher in patients who failed to respond to PTX (Fig 4A). We next isolate and purified extracellular vesicles (EVs) from the plasma of breast cancer patients by ultracentrifugation, and subsequent transmission electron microscopy (TEM) and NanoSight nanoparticle tracking analysis (Appendix Fig S3A). In these PTX nonresponders, the level of TβRII on circulating extracellular vesicles (crEVs) in the plasma from breast cancer patients was also significantly increased and positively correlated with the USP8 mRNA and protein expression levels (Fig 4A and B). Moreover, a higher number of TβRII+ crEVs before treatment was associated with poorer clinical outcomes (Fig 4C). The percentage of IFN‐γ+ CD8+ T cells, as determined by FACS, was shown to inversely correlate with circulating EV‐TβRII in PTX nonresponders (Fig 4D).

Fig 4. Gain of USP8 function promotes the secretion of EV‐TβRII during metastasis.

-

AComparison of the pretreatment levels of USP8 mRNA in patient‐derived tissue samples by qRT–PCR (left panel), enzyme activity of USP8 in patient‐derived tissue samples by Ub‐VME (middle panel), and TβRII+ crEV level in the plasma from breast cancer patients by ELISA (right panel) between breast cancer patients with or without clinical response to PTX. R, responders; n = 16; NR, nonresponders; n = 14.

-

BPearson correlation of the USP8 mRNA or USP8 enzyme activity in patient‐derived tissue samples with the EV‐TβRII levels in the plasma from breast cancer patients without clinical response to PTX as in (A) (NR, n = 14).

-

CObjective response rate (ORR) for patients as in (A) (n = 30) with high (>0.95 ng/ml) and low (<0.95 ng/ml) pretreatment levels of circulating EV‐TβRII.

-

DPearson correlation of the percentage of IFN‐γ+ of CD8+ cells to the TβRII+ crEV level in the plasma from breast cancer patients without clinical response to PTX as in (A) (NR, n = 14).

-

ETβRII+ crEVs (left panel), the USP8 enzyme activity (middle panel), and USP8 mRNA (right panel) from breast cancer patients with or without clinical response to combined therapy using anti‐PD‐L1 (Atezolizumab) and paclitaxel. R, responders; n = 10 (left panel), n = 5 (middle and right panels, only 5 patient‐derived tissue samples obtained). NR, nonresponders; n = 10 (left panel), n = 6 (middle and right panels, only 5 patient‐derived tissue samples obtained).

-

F–HExperimental procedure in vivo: MDA‐MB‐231 cells were intracardially injected into nude mice. Bioluminescent imaging (BLI) of representative mice from each group at week 6 injected with control (n = 9) or MDA‐MB‐231 cells stably overexpressed with USP8‐WT (n = 7) or USP8‐CS (n = 9). BLI images are shown (F (left panel)). BLI signal of each mice (F (middle panel)) and the number of bone metastasis (F (right panel)) of every mouse, and the percentage of bone metastasis‐free mice survival in each experimental group followed in time (G). Fold change of circulating EV‐TβRII by ELISA analysis in plasma samples of mice in each experimental group at week 6 (H).

-

I–LExperimental procedure in vivo: nude mice were tail vein‐injected with 4T07‐Luc cells (5 × 105 cells per mouse) expressing control vector or doxycycline‐inducible USP8‐wt/cs and tumors were grown for 2 weeks, followed by the administration of doxycycline (n = 6 for each group) (I). Normalized BLI signals (left panel) and representative mice (right panel) from each group at the indicated times (J). Immunoblot analysis of the circulating EVs from plasma in mice (K). ELISA analysis of circulating exosomal TβRII level in plasma samples of mice at the indicated times (L).

Data information: *P < 0.05 (two‐tailed Student's t‐test (A, C, E, F, H, L), Pearson's correlation test (B, D), two‐way ANOVA (G, J (left))). Data are shown as mean + SD (L) or as mean ± SD (A, E, F, H, J (left)).

Source data are available online for this figure.

Combinations of PTX and anti‐PD‐L1 therapies prolonged progression‐free survival in patients with metastatic triple‐negative breast cancer (Schmid et al, 2018) and we found that pretreatment levels of EV‐TβRII were significantly higher in triple‐negative breast cancer patients who failed to respond to these combined therapies (Fig 4E). The USP8 enzyme activity and mRNA levels were also significantly higher in patients who failed to respond to chemoimmunotherapy (Fig 4E), which is consistent with the other results in this study. When we combine this data with our previous observations, these results suggest that USP8 gain of function in chemoimmunotherapy‐resistant patients likely increases the levels of EV‐TβRII and enhances tumor progression.

Next, we examined the effect of USP8 overexpression in vivo using a mouse xenograft metastasis model. Mice intracardially injected with control MDA‐MB‐231 cells began to develop detectable bone metastasis after 4 weeks. Forced expression of USP8 wt, but not of USP8 cs, significantly enhanced bone metastasis in mice within 42 days and significantly shortened bone metastasis‐free survival (Fig 4F and G). As expected, in the case of tumors expressing USP8 wt, but not USP8 cs, the TβRII levels in the crEVs from the plasma of mice were significantly enhanced (Fig 4H). Next, we generated 4T07 cells with doxycycline‐inducible USP8 wt or USP8 cs (Appendix Fig S3B) and used a mouse model to examine enhanced USP8 function in vivo. Nude mice treated with these cells via tail vein injection were then housed for 2 weeks before receiving their first dose of doxycycline (Fig 4I). USP8 wt‐expressing cells, but not USP8 cs‐expressing cells, exhibited significantly increased lung metastasis (Fig 4J). In line with this, TβRII levels and function were also shown to be specifically enhanced following the inducible expression of USP8 wt, in both the metastatic tumor cells (Appendix Fig S3C) and the circulating EVs from plasma of mice (Fig 4K). In addition, ELISA detected high levels of EV‐TβRII in mice containing inducible USP8 wt‐expressing tumor cells (Fig 4L). Taken together, these results suggest that the frequent gain of USP8 function following breast tumor treatment promotes the secretion of EV‐TβRII and drives breast cancer invasion and metastasis.

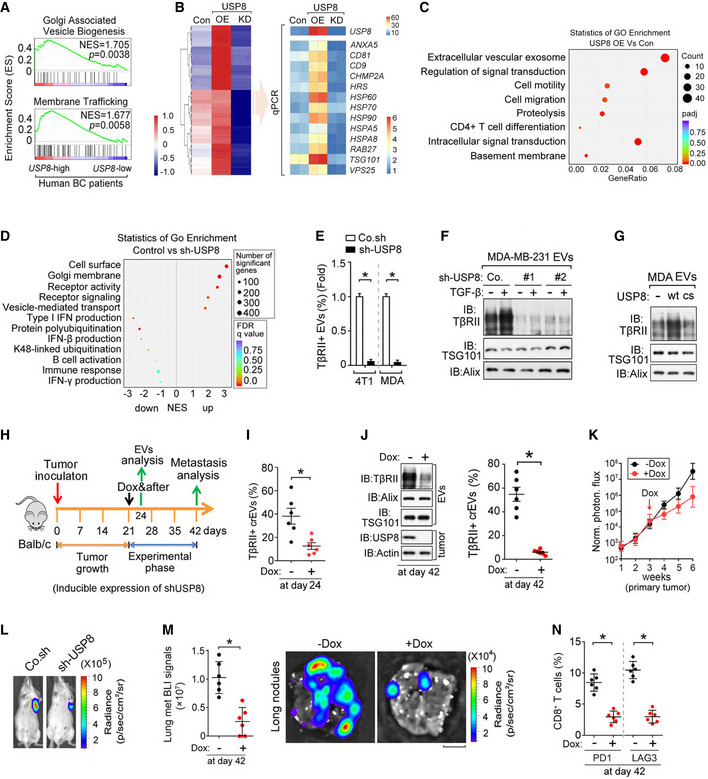

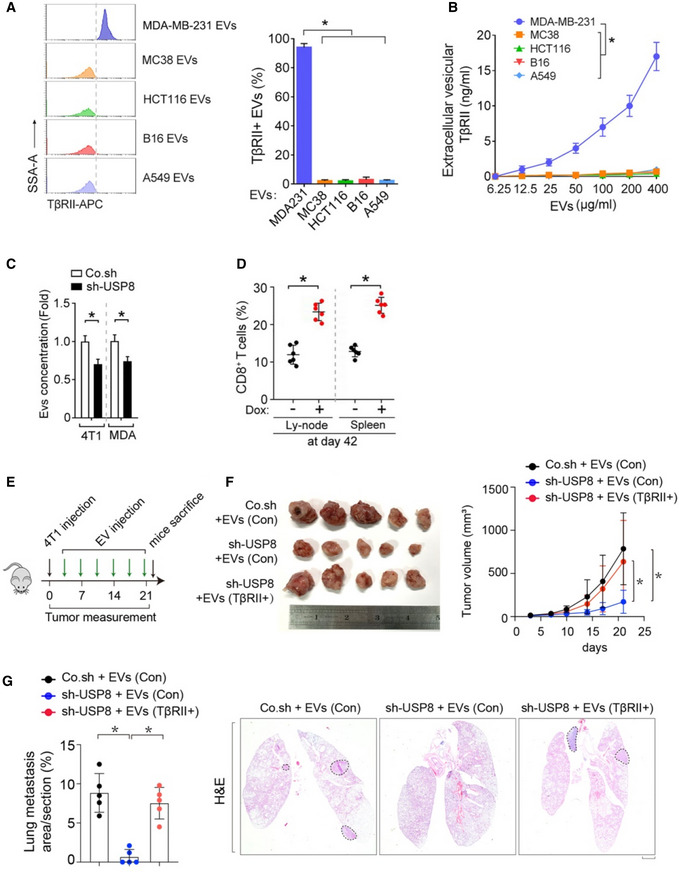

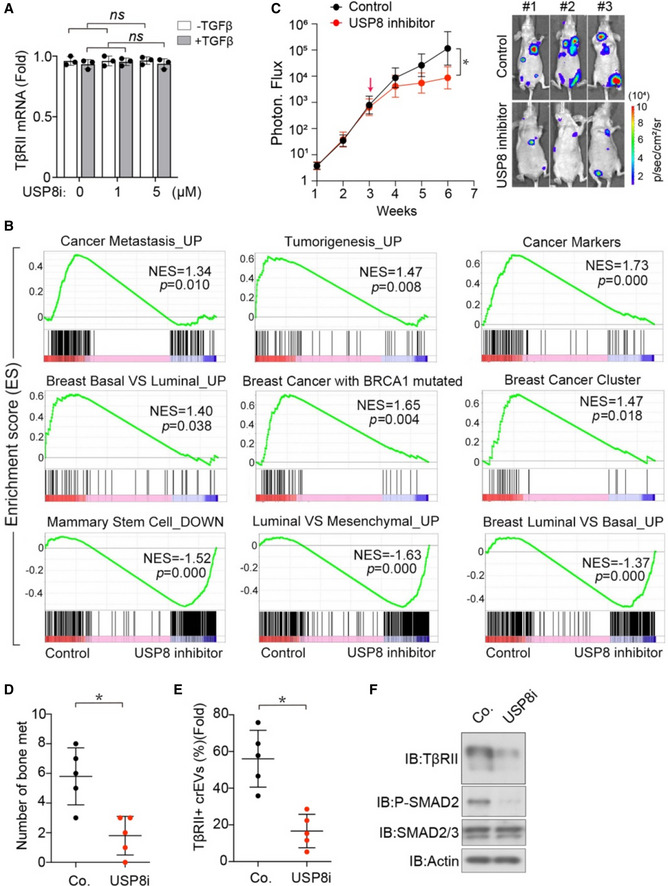

The level of TβRII in crEVs is dependent on deubiquitination by USP8

To investigate whether the above‐described USP8 results are related to the pathogenesis of human breast cancer, we examined USP8 expression patterns in publicly available microarray datasets. The GSEA of the NKI295 breast cancer patient dataset showed that gene signatures representing increased vesicle formation and membrane trafficking were significantly enriched in patients with higher levels of USP8 expression (n = 38) when compared with those with lower expression levels (n = 39) (Fig 5A). Gene expression analysis of MDA‐MB‐231 cells over or under expressing USP8 demonstrated a tangible link between USP8 expression and the expression of several extracellular vesicle‐related genes (Fig 5B). Gene‐set enrichment analysis (GSEA) of significantly up‐ and downregulated gene sets showed that high levels of USP8 correlated with an increase in the gene signatures representing enhanced cell membrane remodeling, vesicle transport, cell motility, and reduced immune responses (Fig 5C and D). These results are consistent with our observation that USP8 promotes the secretion of EV‐TβRII and metastasis. Interestingly, Flow cytometry and ELISA analysis showed that TβRII was abundant and specifically enriched in EVs of the highly metastatic breast cancer cell, but not form EVs of other types of cancer (Fig EV2A and B). To further determine the molecular mechanism by which USP8 regulates EV‐TβRII, we purified EVs from high‐metastatic (MDA‐MB‐231 and 4T1) breast cancer cells after depletion of USP8. Although USP8 depletion slightly reduced the total amount of tumor cell‐secreted EVs by approximately 25%, the TβRII+ TEVs were reduced to nearly undetectable levels (Fig 5E and EV2C), suggesting that USP8 specifically regulates TβRII expression. Immunoblots confirmed that EV‐TβRII levels could be sharply reduced by USP8 depletion, and markedly increased by USP8 overexpression (Fig 5F and G). The DUB activity of USP8 seems to be required for increases in EV‐TβRII production, as mutant USP8 cs, which lacks DUB activity, had no such effect (Fig 5G).

Fig 5. The TβRII levels in crEVs are dependent on deubiquitination by USP8.

-

AGene signatures indicating the Golgi‐associated vesicle biogenesis‐ and membrane trafficking‐related genes are significantly enriched in USP8‐high (n = 38) patients versus USP8‐low (n = 39) expressing patients; shown by preranked gene‐set enrichment analysis (GSEA).

-

BHeatmap shows the upregulated genes upon USP8 overexpression and the downregulated genes upon USP8 depletion when compared with control MDA‐MB‐231 cells by RNA‐seq analysis (left panel). qRT–PCR analysis of control or MDA‐MB‐231 cells stably overexpressing USP8 (USP8 OE) or USP8 shRNA (right panel).

-

CGo enrichment analysis of significantly altered gene sets in USP8 overexpressed MDA‐MB‐231 cells versus control.

-

DGo enrichment analysis of significant up‐ and downregulated gene sets in control versus USP8‐depleted MDA‐MB‐231 cells.

-

EFACS analysis of EVs from 4T1 and MDA‐MB‐231 cells infected with lentivirus encoding control shRNA (Co.sh) or USP8 shRNA.

-

FImmunoblot analysis of EVs from MDA‐MB‐231 cells infected with lentivirus encoding control shRNA (Co.sh) or USP8 shRNA (#1 & #2).

-

GImmunoblot analysis of the EVs derived from MDA‐MB‐231 cells ectopically expressing USP8 wt/cs.

-

HExperimental procedure in vivo: BALB/c mice were nipple injected with 4T1‐Luc cells (5 × 105 cells per mouse) expressing control shRNA or doxycycline‐inducible shRNA‐targeting USP8 (shUSP8), and tumors were grown for 3 weeks, followed by the administration of doxycycline for 3 weeks (n = 6 for each group).

-

IQuantification of the percentage of TβRII+ crEVs in plasma samples from mice at day 24.

-

JImmunoblot analysis of tumor and the TEVs (left panel) and quantification of the percentage of TβRII+ EVs (right panel) in plasma samples from mice at day 42.

-

KNormalized photon flux at the indicated times.

-

LRepresentative BLI signals of the primary tumor in each group at day 42 after implantation of 4T1 cells (2 × 105 cells per mouse, n = 6 per group).

-

MNormalized BLI signals (left panel) and bioluminescent images (right panel) of the lung metastasis nodules. Scale bars, 2 mm.

-

NPercentage of CD8+ T cells of tumor‐draining lymph nodes (TDLN) at day 42.

Data information: *P < 0.05 (two‐tailed Student's t‐test (E, I, J (right), M (left), N) or two‐way ANOVA (K). Data are representative of at least three independent experiments and shown as mean + SD (E); Data are shown as mean ± SD (I, J (right), M (left), N).

Source data are available online for this figure.

Fig EV2. Loss of USP8 increases the percentage of CD8+ T cells from lymph nodes and spleen.

-

AFACS analysis (left) and Quantification of TβRII in purified EVs from various types of cancer cell lines: metastatic bresat cancer cells (MDA‐MB‐231), colorectal cancer cells (MC38 and HCT116), melanoma B16 or lung cancer cells (A549).

-

BELISA analysis of TβRII in purified EVs from various types of cancer cell lines: metastatic bresat cancer cells (MDA‐MB‐231), colorectal cancer cells (MC38 and HCT116), melanoma B16 or lung cancer cells (A549).

-

CEVs concentration by nanosight of 4T1 and MDA‐MB‐231 cells infected with lentivirus encoding control shRNA (Co.sh) or USP8 shRNA.

-

DQuantification of the percentage of TβRII+ EVs in plasma samples from mice at day 42.

-

E–GExperimental analysis in vivo: BALB/c mice were nipple injected with control and USP8 stably depleted‐4T1 cells (5 × 105 cells per mouse), followed by tail vein‐injection of Co.EVs or TβRII+ EVs (50 μg per mouse every other day) for 3 weeks (n = 5 per group) (E). Bright view of primary tumor from each group at week 3 (left) and tumor volume measured in time (right) (F). Percentage of lung metastasis area of all mice (left) and representative HE stained lung sections (right) from each group at week 3 (G). Scale bar, 1 mm.

Data information: *P < 0.05 (two‐tailed Student's t test (A, C, D, G) or two‐way ANOVA (B, F)). Data are shown as mean + SD (A, C) or as means ± SD (B, D, F, G).

To examine whether USP8 could be an endogenous determinant of TβRII+ TEVs in tumors, we used a doxycycline‐inducible promoter to silence USP8 expression in 4T1 cells. Mice xenografted with these cells were treated with doxycycline 3 weeks after inoculation (Fig 5H). Plasma from mice not treated with doxycycline displayed TβRII+ TEVs ranging from 18 to 64% (average, 40%), while 3 days of doxycycline treatment reduced the abundance of TβRII+ TEVs to 13.4% (Fig 5I). Continuous doxycycline treatment for 3 weeks nearly abolished EV‐TβRII secretion (Fig 5J). Loss of USP8 also reduced the primary tumor size (Fig 5K and L), potently inhibited lung metastasis (Fig 5M), increased the percentages of CD8+ T cells from lymph nodes and spleen (Fig EV2D), and reduced the expression of inhibitory receptors such as PD1 and LAG3 on CD8+ T cells from tumor‐draining lymph nodes (Fig 5N). To determine the relative impact of TβRII on the overall effect of USP8, we transplanted control or USP8‐depleted 4T1 cells into mice followed by tail vein injection of in vitro collected TEVs from either their WT or TβRII null counterparts (Fig EV2E). Consistently, knockdown of USP8 significantly reduced both the tumor growth and lung metastasis (Fig EV2F and G). As shown, education with TβRII containing EVs could effectively rescue the tumor growth and metastasis in mice inoculated with USP8‐depleted 4T1 cells (Fig EV2F and G). These results indicated that TβRII+ EVs have a significant impact on the overall effect of USP8. In summary, these results identified USP8 as a determinant of TβRII levels in TEVs.

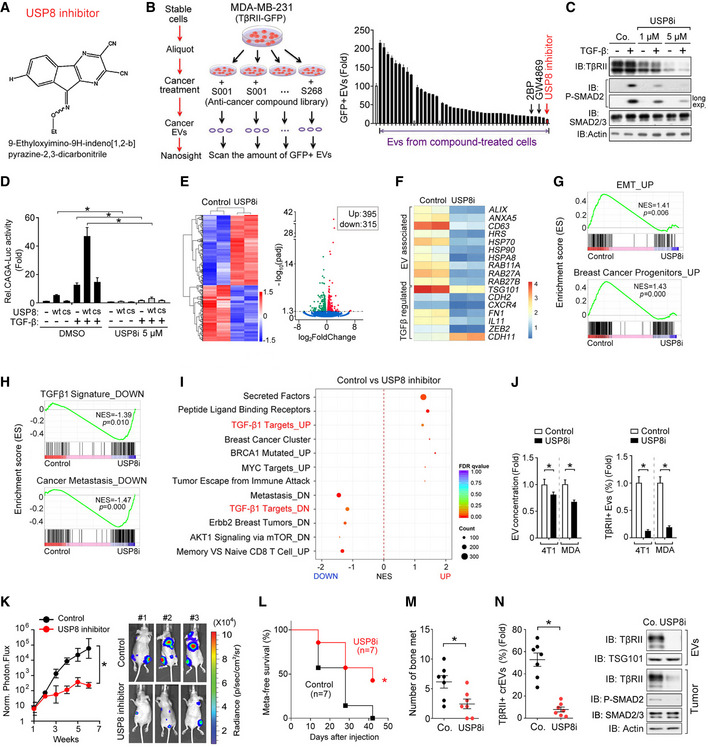

Pharmacological inhibition of USP8 inhibits TGF‐β/SMAD signaling and the secretion of EV‐TβRII

The above findings revealed that USP8 is a druggable target; thus, we synthesized a small‐molecule inhibitor that specifically blocks the enzymatic activity of USP8 (Colombo et al, 2010) (Fig 6A). To systematically identify the cancer cell components controlling the secretion of EV‐TβRII, we treated MDA‐MB‐231 cells stably expressing TβRII‐GFP with a cancer component inhibitor library comprising 268 small molecules targeting key oncogenic proteins (Gao et al, 2018) and then isolated EVs and analyzed the proportion of GFP+ EVs using nanosight scanning (Fig 6B). Notably, cells treated with GW4869 (an inhibitor of exosome biogenesis/release) and 2BP (a palmitoylation blocker) lost their ability to produce TβRII‐GFP+ TEVs altogether (Fig 6A and B), indicating that palmitoylation is likely required. As expected, the USP8 inhibitor was also validated on this screen and shown to be among the most effective compounds evaluated in this assay. Our inhibitor not only prevented the release of TβRII+ EVs (Fig 6B), but also reversed the activation of TGF‐β signaling in the donor, as exemplified by the fact that MDA‐MB‐231 cells treated with this compound were shown to present with reduced TβRII protein expression and TGF‐β‐induced SMAD2 phosphorylation (Fig 6C) but did not show any change in the expression of TβRII mRNA (Fig EV3A). In line with this, the USP8 inhibitor suppressed the basal and USP8 wt‐induced CAGA‐luc activities both in the absence and presence of the TGF‐β ligand (Fig 6D). RNA profiling identified the differentially expressed genes associated with USP8 inhibitor treatment; these included various genes associated with EV assembly and trafficking, and essential TGF‐β targets in EMT and metastasis (Fig 6E and F). GSEA and GO enrichment analysis showed that gene signatures representing increased EMT and cancer progression were significantly enriched in control cells, while the gene sets representing reduced TGF‐β signaling and metastasis were significantly enriched in cells treated with the USP8 inhibitor (Figs 6G–I and EV3B). In line with our previous observations of USP8 knockdown, the USP8 inhibitor slightly reduced the concentration of tumor‐derived EVs and notably reduced the levels of TβRII+ TEVs (Fig 6J).

Fig 6. Pharmacological inhibition of USP8 represses TGF‐β signaling and prevents the exosomal secretion of TβRII.

-

AStructure of the USP8 inhibitor, 9‐ethyloxyimino‐9H‐indeno [1,2‐b] pyrazine‐2,3‐dicarbonitrile.

-

BLeft: screening procedure for cellular components critical for the secretion of EV‐TβRII; Right: nanosight analysis of GFP positive EVs derived from MDA‐MB‐231 cells expressing TβRII‐GFP and pretreated with anti‐cancer compounds. n = 3 technical replicates.

-

CImmunoblot analysis of total cell lysates derived from MDA‐MB‐231 breast cancer cell treated with USP8 inhibitor and TGF‐β (2.5 ng/ml) as indicated.

-

DEffect of USP8 inhibitor (5 μM) on SMAD3/SMAD4‐dependent CAGA12‐Luc transcriptional response induced by TGF‐β (2.5 ng/ml) for 16 h in HEK293T cells transfected with control vector (Co.vec) or USP8 wt/cs. n = 3 biological replicates.

-

EHeatmap shows differentially expressed genes in control DMSO‐treated or USP8 inhibitor (5 μM)‐treated MDA‐MB‐231 cells for 24 h (left panel). Volcano plot of transcriptome profiles between control and USP8 inhibitor‐treated MDA‐MB‐231 cells (right panel). Red and green dots represent genes significantly upregulated and downregulated in control MDA‐MB‐231 cells. (P < 0.05, false discovery rate [FDR] < 0.1).

-

FqRT–PCR analysis of control (DMSO‐treated) or USP8 inhibitor (5 μM for 24 h) treated MDA‐MB‐231 cells. Relative mRNA levels are shown as a heatmap.

-

GGene signatures indicating the upregulated epithelial‐mesenchymal transition (EMT) (upper panel) and breast cancer progenitors‐related gene set (bottom panel) are significantly enriched in control cells; shown by preranked gene‐set enrichment analysis (GSEA).

-

HThe downregulated TGF‐β signaling (upper panel) and metastasis‐related gene sets (bottom panel) are significantly enriched in USP8 inhibitor‐treated MDA‐MB‐231 cells; shown by preranked gene‐set enrichment analysis (GSEA).

-

IGo enrichment analysis of significant up‐ and downregulated gene sets in control DMSO versus USP8 inhibitor‐treated MDA‐MB‐231 cells.

-

JThe total concentration of EVs by nanosight analysis (left) and the percentage of TβRII+ EVs by FACS (right) from 4T1 and MDA‐MB‐231 cells treated with USP8 inhibitor (5 μM) for 24 h. n = 3 technical replicates.

-

K–NExperimental procedure in vivo: MDA‐MB‐231‐Luc cells (1 × 105 per mouse) were intracardially injected into nude mice (n = 7 for each group). USP8 inhibitor (1 mg/kg) was injected on day 1 via intraperitoneal injection every the other day for 3 weeks. Normalized BLI signals (left panel) and BLI imaging of three representative nude mice from each group at week 6 (right panel) were shown (K). Percentage of metastasis‐free survival in each experimental group followed in time (L). Number of bone metastasis nodules (M). Percentage of TβRII+ crEVs in plasma samples from mice (left panel) and immunoblot analysis of metastatic tumor nodule in mice and circulating EVs from plasma (right panel) (N).

Data information: *P < 0.05 (two‐tailed Student's t‐test (D, J, M, N (left)) or two‐way ANOVA (K, L)). Data are shown as mean + SD (B, D, J) or as mean ± SD (K, M, N (left)).

Source data are available online for this figure.

Fig EV3. USP8 inhibitor represses cancer progression and metastasis.

-

ANormalized TβRII mRNA expression from MDA‐MB‐231 breast cancer cells treated with USP8 inhibitor and TGF‐β (2.5 ng/ml) as indicated.

-

BPre‐ranked gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) in MDA‐MB‐231 cells treated with control DMSO versus USP8 inhibitor (2 μM) for 24 h. The consensus signature of the genes correlated with various breast tumor characteristics that enriched in cells with normal USP8 activity (control) or cells with suppressed USP8 activity (USP8 inhibitor) were shown.

-

C–FExperimental analysis in vivo: MDA‐MB‐231‐Luc cells (1 × 105 per mouse) were intracardially injected into nude mice (n = 5 for each group). After 3 weeks, USP8 inhibitor (1 mg/kg) was injected via intraperitoneal injection every the other day for three weeks. BLI signals (left panel) and BLI imaging of three representive nude mice from each group at week 6 (right panel) were shown (C). Number of bone metastasis nodules (D). Percentage of TβRII+ crEVs in plasma samples from mice (E). Immunoblot analysis of metastatic tumor nodule in mice (F).

Data information: *P < 0.05 (two‐tailed Student's t test (A, D, E) or two‐way ANOVA (C)). Data are shown as mean ± SD (A, C, D, E).

Next, we used highly bone metastatic MDA‐MB‐231(BM) cells to evaluate the effect of USP8 inhibitors on tumor metastasis. Mice that had been intracardially injected with control MDA‐MB‐231 cells began to develop clear bone metastases after 2 weeks, and the number of metastatic nodules and the area covered by them expanded in the following weeks (Fig 6K). Mice treated with USP8 inhibitor for 3 weeks developed fewer bone metastases and had significantly longer metastasis‐free survival periods (Fig 6K–M). Untreated mice transplanted with MDA‐MB‐231 cells displayed TβRII+ crEV levels ranging from 30 to 75% (average, 55%), while the mice treated with the USP8 inhibitor produced less than 15% of the TβRII+ crEVs (Fig 6N, left panel). In addition, in vivo evaluations of the USP8 inhibitor demonstrated that this compound reduced TβRII levels, both in the crEVs and in the metastatic tumors (Fig 6N, right panel). Furthermore, we also performed a mice experiment to explore the effect of USP8 inhibitor in vivo with established lesions. Mice were firstly intracardially injected with MDA‐MB‐231‐luc cells for 3 weeks and then given USP8 inhibitor (Fig EV3C). As shown, both the bone metastases and TβRII+ crEV levels were significantly suppressed by USP8 inhibitor in mice with established, size‐matched lesions (Fig EV3D and E). TGF‐β/SMAD signaling was also inhibited in tumors (Fig EV3F). Taken together, these results demonstrated the potency of this small molecule when antagonizing TGF‐β/SMAD signaling in tumors and diminishing the secretion of EV‐TβRII.

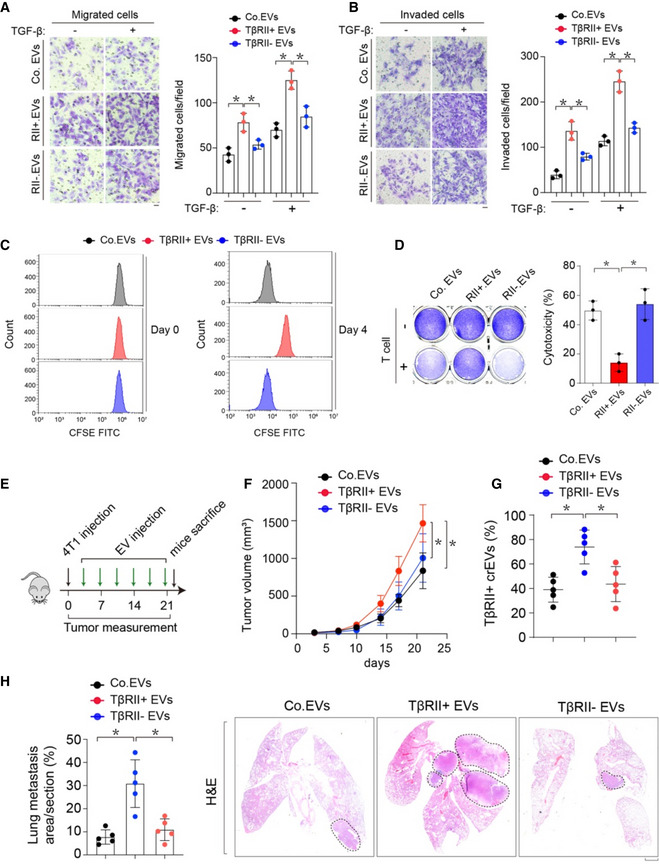

Pharmacological inhibition of USP8 alleviates T cell exhaustion and improves the efficacy of breast cancer immunotherapy

To address whether TβRII+ EVs are responsible for cancer progression, we co‐cultured TβRII+ EVs with MDA‐MB‐231 cancer cells and performed transwell assays with or without matrigel to evaluate the effect of TβRII+ EVs on the migration and invasion capacity of cancer cells. Transwell assay indicated that TβRII+ EVs significantly enhanced the migration and invasion of MDA‐MB‐231 cells with or without TGF‐β treatment. However, no significant changes in cell migration and invasion capacity were observed when cells were co‐cultured with control EVs or TβRII− EVs (Fig EV4A and B). Tumor immune escape is a major cause of tumor metastasis and has been implicated in the failure of some clinical tumor immunotherapy (Daassi et al, 2020). T cell exhaustion plays a crucial role in cancer immune dysfunction, which causes tumor recurrence and metastasis. T cell exhaustion is characterized by high and sustained expression of inhibitory receptors, progressive loss of capacity of producing effector cytokines, diminished proliferating capacity, and distinct transcriptional and epigenetic programs (Khan et al, 2019; McLane et al, 2019; Scott et al, 2019). Recent evidences suggest that exosomes, a small subset of EVs, are involved in numerous physiological and pathological processes and play essential roles in remodeling the tumor immune microenvironment even before the occurrence and metastasis of cancer (Chen et al, 2018; Poggio et al, 2019). We thus co‐cultured T cells with TβRII+ EVs and observed suppressed T cell proliferation and tumor‐killing capabilities by TβRII+ EVs (Fig EV4C and D). To investigate whether exogenously introduced EV‐TβRII could promote tumor growth and metastasis in the syngeneic model, we transplanted 4T1 cells in mice followed by tail vein injections of the in vitro collected TEVs from either their WT or TβRII null counterparts (Fig EV4E). Injection of EVs from the WT (TβRII+ EVs), but not TβRII null (TβRII− EVs), cells more strongly promoted tumor growth (Fig EV4F and G). In line with the tumor growth, cancer metastases were also elevated by TβRII+ EVs, but not TβRII− EVs (Fig EV4H). Together, these results consolidated that TβRII+ EVs increase tumor growth and metastasis in vivo.

Fig EV4. TβRII+ EVs increase tumor growth and metastasis in vivo .

-

A, BTranswell migration assay (A) and transwell invasion assay (B) using MDA‐MB‐231 cells co‐cultured with Co.EVs or TβRII+ or TβRII− EVs (50 μg) for 48 h. Representative figures from three independent experiments are shown. The quantification of migrated cells per field is shown in the bar graphs; mean ± SD.

-

CThe cellular proliferation of CD8+ T cells was analyzed using a 4‐day CFSE dilution assay.

-

DT cell‐mediated cancer cell killing assay: MDA‐MB‐231 cells co‐cultured with or without activated T cells for 48 h were subjected to crystal violet staining (left). MDA‐MB‐231‐to‐T cell ratio = 1:3. Quantification of cytotoxicity of T cells (right).

-

E–HExperimental analysis in vivo: BALB/c mice were nipple injected with 4T1 cells (5 × 105 cells per mouse), followed by tail vein‐injection of Co.EVs or TβRII+ or TβRII− EVs (50 μg per mouse every other day) for 3 weeks (n = 5 per group) (E). Tumor volume measured in time (F). Percentage of TβRII+ crEVs in plasma of all mice in each group at week 3 (G). Percentage of lung metastasis area of all mice (left) and representative HE stained lung sections (right) from each group at week 3 (H). Scale bar, 1 mm.

Data information: *P < 0.05 (two‐tailed Student's t test (A, B, D, G, H) or two‐way ANOVA (F)). Data are shown as mean ± SD (A, B, D, F, G, H).

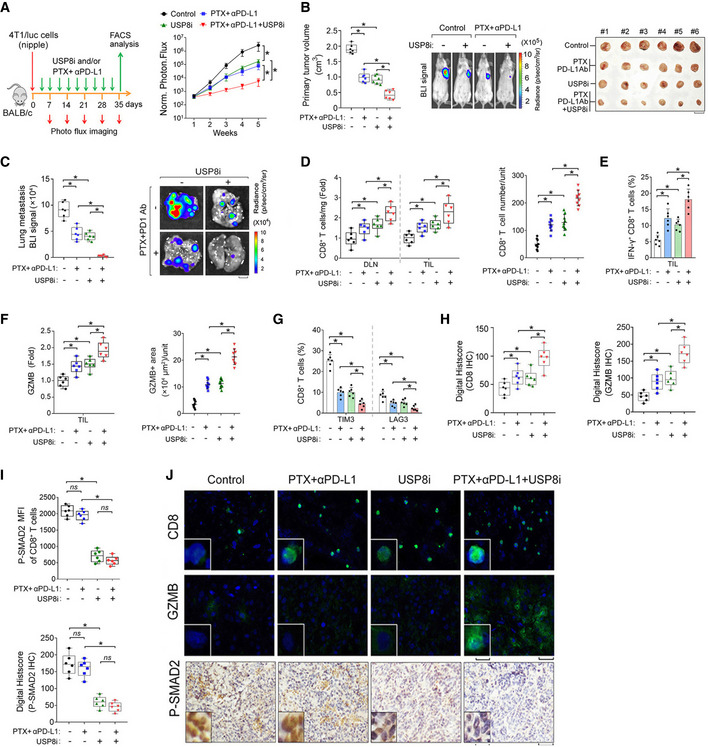

Our findings have shown that The EV‐TβRII levels were found to correlate with chemoimmunotherapy resistance in patients (Fig 4A–E). Particularly in PTX nonresponders, the percentage of IFN‐γ+ CD8+ T cells was inversely correlated with circulating EV‐TβRII (Fig 4D). Moreover, 4T1‐bearing balbc mice model showed that loss of USP8 inhibited CD8+ T exhaustion and enhanced anti‐tumor immunity (Fig 5H–N). Considering the crucial role of USP8 in controlling the secretion of EV‐TβRII and tumor progression, antagonizing USP8 with an inhibitor combined with anti‐PD‐L1 might have the potential to simultaneously prevent tumor progression and exhaustion of CD8+ T cells, thereby reactivating anti‐tumor immunity. Given this fact, we designed an experiment to confirm this probability. We used a USP8 inhibitor to diminish TβRII in tumors and TEVs, and combined this with PTX and anti‐PD‐L1 as a strategy for breast tumor therapy. In vitro, the combination of the USP8 inhibitor and PTX alone cooperatively reduced breast cancer cell survival in multiple breast cancer cell lines (Appendix Fig S4A and B). In vivo, mice inoculated with 4T1 cells were treated with USP8 inhibitor with or without the combination of PTX and anti‐PD‐L1 (Fig 7A). Although the therapeutic blockade of TβRII (USP8 inhibitor) alone or the use of PTX plus anti‐PD‐L1 alone already demonstrated notable reductions in tumor growth and metastasis, mice that received full combination treatments exhibited much stronger reductions in tumor burden and metastasis (Fig 7A–C and Appendix Fig S4C). When we compared this to the case for the treatment with the USP8 inhibitor alone or PTX plus anti‐PD‐L1 alone, the full combined treatment also resulted in a marked increase in the number of tumor‐infiltrating CD8+ T cells (Fig 7D), particularly, effector CD8+ T cells (Fig 7E–F and Appendix Fig S4D–E), and reduced expression of inhibitory receptors that induce T cell exhaustion (Fig 7G). Furthermore, quantitative histopathology and immunofluorescence of the primary tumors demonstrated that the number of tumor‐infiltrating CD8+ T cells, and the production of the cytokine GZMB, increased markedly in response to the full combined treatment (Fig 7H and J, and Appendix Fig S4F). We also observed that the phosphorylation of SMAD2 was significantly reduced not only in primary tumor cells, but also in tumor‐infiltrating CD8+ T cells (Fig 7I and J) following the application of the full combined therapy protocol. In patients, CIBERSORT revealed that the immune cell population (CD8+ T cells) in USP8 low breast tumors is significantly higher than that in USP8 high breast tumors (Appendix Fig S4G), showing USP8 high breast cancer tumors are associated with low infiltration of CD8+ T cells. Together, these results suggest that USP8 inhibition alleviates T cell exhaustion and improves breast cancer immunotherapy (Fig 8).

Fig 7. Pharmacological inhibition of USP8 alleviates tumor‐induced T cell exhaustion and improves the efficacy of breast cancer immunotherapy.

-

AExperimental analysis in vivo: BALB/c mice were nipple injected with 4T1 cells (5 × 105 cells per mouse), followed by intraperitoneal injection of USP8 inhibitor (1 mg/kg) and/or paclitaxel (PTX, 10 mg/kg) plus anti‐PD‐L1 (150 μg per mouse) antibody for 5 weeks (left panel); Normalized BLI signals of representative mice from each group at week 5 (right panel), n = 6 for each group.

-

BQuantification of the primary tumor volume (left panel), BLI imaging of representative mice (middle panel), and bright view of primary tumor (right panel) from each group at week 5. Scale bar, 1 cm.

-

CNormalized BLI signals (left panel) and representative BLI imaging (right panel) of lung metastasis nodules from each group at week 5. Scale bar, 2 mm.

-

DFold change relative to the control mean in total CD8+ T cell abundance from draining lymph node (DLN) and TIL (cells mg−1) (left panel). Quantification of CD8+ T cell by immunofluorescence and DAPI staining in the primary tumor (right panel).

-

EQuantification of the percentage of IFN‐γ+ cells among the CD8+ T cells populations from TIL.

-

FFold change relative to the control of CD8+ T cell GZMB mean fluorescence intensity by flow cytometry (left panel). Quantification of GZMB by immunofluorescence and DAPI staining in the primary tumor (right panel).

-

GQuantification of the percentage of CD8+ T cells expressing TIM3 or LAG3 from TIL.

-

HQuantification of CD8 (left) and GZMB (right) by immunohistochemistry at day 35 in the primary tumor.

-

IQuantification of CD8+ T cell P‐SMAD2 mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) by flow cytometry (upper panel). Quantification of p‐SMAD2 by immunohistochemistry at day 35 in the primary tumor (lower panel).

-

JRepresentative images of immunostaining of CD8 (upper panel), GZMB (middle panel), and immunohistochemistry of p‐SAMD2 (lower panel) in the 4T1 tumor mass. Unit = 300,000 mm2. Scale bar, 50 μm (inset, 10 μm) in immunofluorescence and scale bar, 100 μm (inset, 200 μm) in immunohistochemistry.

Data information: ns, not significant (P > 0.05) and *P < 0.05 (two‐tailed Student's t‐test (B–I) or two‐way ANOVA (A)). Data are shown as mean + SD (E, G) or as mean ± SD (A, B, C, D, F, H, I). Box‐and‐whisker plots (B, C, D, F, H, I), boxes show 25–75th percentile, lines show median, and whiskers show the range of data points.

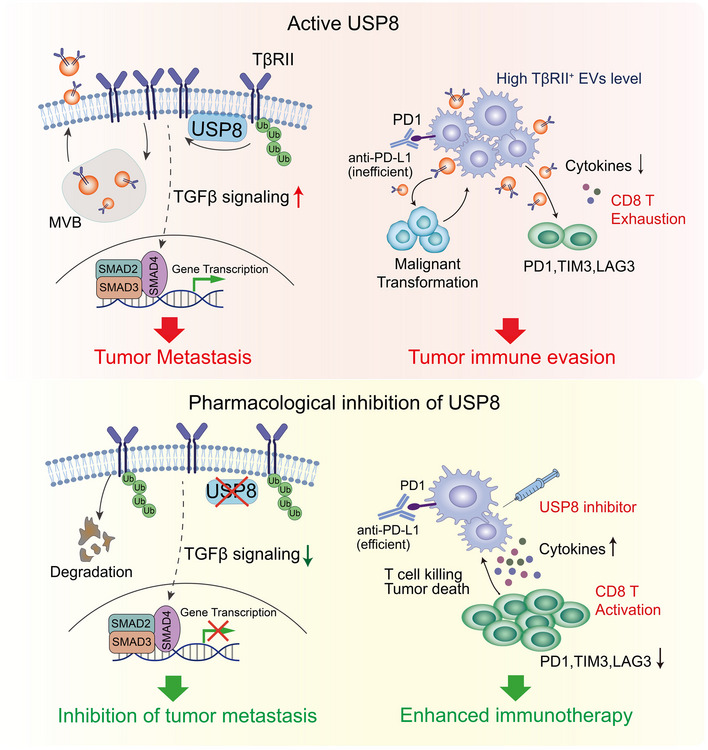

Fig 8. Working model of USP8 and its blockade in regulating cancer metastasis and exhaustion of CD8+ T cells.

Briefly, in aggressive breast cancer tumors, USP8, as the deubiquitinase for TβRII, enhances membrane location and EVs‐mediated the secretion of TβRII thereby stimulating TGF‐β/SMAD activation and increasing tumor metastasis in remote recipient cells. EV‐TβRII as cargo delivered to CD8+ T cells induces CD8+ T cell exhaustion and dysregulation of anti‐tumor immunity (upper). Blockade of USP8 with specific inhibitor not only suppresses the metastatic potential of tumor cells but also inhibits secretion of TβRII+ EV, this synergizes with anti‐PD‐L1 immunotherapy to alleviate CD8+ T cell exhaustion and boost CD8+ T cell effector function, which leads to effective anti‐tumor immunity (bottom).

Discussion

Here, we used multiple screening models to identify druggable DUBs linked to cancer metastasis. USP8 was identified as a key component of the TGF‐β/SMAD signaling pathway; it promotes the EMT, cancer stemness, and metastasis of cancer cells. TGF‐β type II receptor (TβRII) was subsequently identified as a direct target of USP8 that was deubiquitinated and stabilized in the plasma membrane fraction. We identified USP8 as a determinant of TβRII+ (TEVs), which are secreted by malignant breast cancer cells. We also elucidated the targeting efficacy of USP8 inhibitors as suppressors of TβRII stability and TβRII secretion through EVs. In addition, we showed that the pharmacological inhibition of USP8 antagonizes TGF‐β/SMAD signaling in cancer cells, thus blocking their metastatic potential and preventing the tumor‐induced exhaustion of CD8+ T cells, thereby improving the efficacy of cancer immunotherapy.

Cell surface TβRII is the first signaling molecule activated by TGF‐β ligands and is required for all TGF‐β signaling responses. Increased TβRII expression may contribute to cancer and drug resistance (Huang et al, 2012). This study provides important new insights into how TβRII cell surface expression and extracellular vesicle numbers might be regulated by USP8. By stabilizing and promoting the plasma membrane co‐localization of TβRII, USP8 promotes SMAD signaling, increasing the invasion, and metastasis of cancer cells. The TβRII on TEVs originates from the membrane of donor cells, and we identified USP8 as the TβRII DUB whose activity enhances the levels of its localization on the cell membrane location and its expression within extracellular vesicles. TβRII expression also positively correlates with USP8 expression in breast cancer tissue microarray analysis, further corroborating these findings.

Our study indicated that USP8 has two possible roles in enhancing the ability of breast cancer cells to become more metastatic. The first is through elevated levels of TβRII, which enhances TGF‐β signaling and increased cancer stemness, migration/invasion, and metastasis (tumor intrinsic). This clearly occurs in xenograft models where T cell anti‐tumor immunity is not a factor. The second is through the potential action of TβRII+ EVs on the suppression of T cell‐mediated anti‐tumor immunity. To explore the predominate mechanism of USP8 inhibitor in the syngeneic model, we injected 4T1 cells into an immunocompromised background to evaluate the effect of USP8 inhibitor on tumor growth and metastasis (Appendix Fig S5A and B). Antibody‐based depletion of CD8+ cells significantly promoted tumor growth and metastasis (Appendix Fig S5C and D). USP8 inhibitor could still impair tumor growth in such immunocompromised background (Appendix Fig S5C and D). These results suggested that the two mechanisms are both important in the syngeneic model.

In metastatic breast cancer cells, blocking USP8 DUB activity reverses TβRII expression, confirming that oncogenic TGF‐β signaling via TβRII is supported by USP8 DUB activity. Based on these findings, we attempted to counteract therapeutic resistance during immunotherapy by introducing a purified USP8 inhibitor. Blocking USP8 not only suppressed TGF‐β/SMAD activity in tumors, but also synergized with the effects of both anti‐PD‐L1 therapies and PTX to alleviate CD8+ T exhaustion and increase functional CD8+ T cell counts in the tumor bed, leading to an increase in anti‐tumor immunity. This means that these findings will have a significant impact on the future of immunotherapeutic approaches to treating cancer and suggest that a key component to improving their success is the targeting of the USP8 proteins. Current TGF‐β pathway inhibition is facilitated by neutralizing anti‐TGF‐β antibodies or kinase inhibitors that preferentially antagonize TβRI kinase activity (Akhurst, 2017). The latter has been shown to have little effect on TGF‐β‐induced non‐SMAD signaling pathways (Mu et al, 2012; Zhang, 2017). Based on our results, we propose that the development of targeted USP8 inhibitors that enable the selective inhibition of TβRII should be prioritized in future (pre) clinical studies. The specific role of USP8 in TβRII (but not TβRI) signaling may result in these inhibitors producing a more substantial therapeutic effect, reducing both the invasiveness and metastasis of cancer cells.

However, these results should be evaluated carefully. Studies using the conditional knockout of TβRII in other cancers have shown that the loss of TβRII may also promote invasion and metastasis (Novitskiy et al, 2011). Careful selection of patients who would benefit from TβRII‐targeted therapy may be needed. Seventy percent of all breast cancers are estrogen receptor α (ER)‐positive and therefore, treated with endocrine therapies. However, 25% of these patients eventually develop endocrine therapy resistance due to ESR1 gain‐of‐function mutations with ligand‐independent ER activity driving metastasis (Robinson et al, 2013; Toy et al, 2013; Jeselsohn et al, 2015). In the analysis of more than 500 breast cancer patients, the gain of ESR1 also correlated with the gain of USP8 (Appendix Fig S5E). Therefore, it is likely that changes in ESR1 also correlate with TβRII gain of function. Thus, endocrine therapy resistance by ESR1 activation could be a possible result of oncogenic TGF‐β activation. This raises the question of whether a combination approach to therapy including a TGF‐β antagonist might counteract well‐tolerated endocrine therapy in ER‐positive patients.

In conclusion, our study provides new insights into how the expression levels of membrane‐TβRII and EV‐TβRII are regulated by USP8‐mediated deubiquitination and how USP8 inhibition enhances the efficacy of experimental breast cancer immunotherapy. It will be interesting to see if the mechanisms we have described here extend to other cancer types, and if they do, whether these underappreciated roles of TGF‐β could serve as a foundation for improving the efficacy of therapeutic strategies against these devastating diseases.

Materials and Methods

Cell culture

HEK293T, HeLa, HaCaT, MDA‐MB‐231, 4T07, and 4T1 cells were originally from ATCC and cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% FBS (Cat No. FSP500, ExCell Bio) and 100 U ml−1 penicillin–streptomycin. MCF10A (MI); MCF10A‐RAS (MII) cell lines were obtained from Dr. Fred Miller (Barbara Ann Karmanos Cancer Institute, Detroit, USA) and cultured in DMEM/F12 supplemented with 5% horse plasma, 20 ng ml−1 epidermal growth factor (EGF), 0.5 μg ml−1 hydrocortisone, 100 ng ml−1 cholera toxin, and 100 U ml−1 penicillin–streptomycin. All cell lines were authenticated and negative for mycoplasma contamination. All cell lines were cultured in a humidifying atmosphere at 5% CO2 at 37°C and are free of mycoplasma contamination.

Extracellular vesicles isolation, purification, and characterization

For extracellular vesicle purification from cell culture supernatants, cells were plated at a density of 3 million per 10 cm plate and cultured in “extracellular vesicle‐depleted medium” (complete medium depleted of FBS‐derived extracellular vesicles by overnight centrifugation at 100,000 g) for 48–72 h. The culture media from 10 plates were pooled and subjected to sequential centrifugation steps: 300 g for 5 min at room temperature to remove floating, 2,000 g for 15 min at 4°C to remove dead cells, 16,000 g for 45 min at 4°C to separate microvesicles, the supernatants were then centrifuged twice at 10,000 g at 4°C for 2 h as described previously (Gao et al, 2018). In each extracellular vesicles/vesicle preparation, the concentration of total proteins was quantified by BCA Protein Assay Kit (Thermo Scientific).

For purification of circulating extracellular vesicles by differential centrifugation, venous citrated blood from breast cancer patients or healthy donors was centrifuged at 1,500 g for 30 min at room temperature to obtain cell‐free plasma. Then, 1 ml of the obtained plasma was centrifuged at 16,000 g for 45 min at 4°C to separate microvesicles. The collected supernatants were then centrifuged at 100,000 g for 2 h at 4°C to pellet the extracellular vesicles. In each extracellular vesicles/vesicle preparation, the concentration of total proteins was quantified by BCA Protein Assay Kit (Thermo Scientific).

Nanoparticle tracking analysis (NTA): The size and concentration of extracellular vesicles/vesicles purified from cell culture supernatants or patients' plasma were determined using a NanoSight NS500 (Malvern Instruments, Amesbury, UK), which is equipped with fast video capture and particle‐tracking software. A monochromatic laser beam at 405 nm was applied to the dilute suspension of vesicles (0.22 μm filtered) with a concentration within the recommended measurement range (1 × 106 to 10 × 108 particles/ml). The Nanoparticle tracking analysis software is optimized to analyze to give the mean, mode, and median vesicle size together with an estimate of the concentration.

Patients and specimen collection

Blood samples from healthy donors and patients with breast cancer were collected under the approved sample collection protocol by The First Affiliated Hospital of Zhejiang University Research Ethics Committee. Written informed consent was obtained from all subjects before blood collection. All experiments involving blood samples from healthy donors and patients were performed in accordance with relevant ethical regulations. Immune cell deconvolution was performed for RNA‐seq data using CIBERSORTx (http://cibersortx.stanford.edu; Newman et al, 2019).

Animal studies and mice metastasis models

Mice were bred under specific pathogen‐free conditions in the animal facilities and all mice experiments were approved by the Committee for Animal Welfare at Zhejiang University. Mice were purchased from the animal husbandry center of the Shanghai Institute of Cell Biology, Academia Sinica, Shanghai, China. For the intracardial injection assays, 5‐weeks‐old female BALB/c nude mice were anesthetized with isofluorane and single‐cell suspension of MDA‐MB‐231/luc cells (1 × 105/100 μl PBS) were inoculated into the left heart ventricle according to the method described by Arguello et al (1988). Bioluminescent imaging was used to verify successful injection and to monitor the metastatic outgrowth. After 6 weeks, all mice were killed and metastatic lesions were confirmed by histological analysis. For the tail vein injection assay, single‐cell suspensions of 4T1‐Luc or 4T07‐Luc cells (1 × 105/100 μl PBS) cells were injected into the tail vein of 5‐week‐old nude mice or female syngeneic BALB/c mice. Development of metastasis was monitored weekly by bioluminescent reporter imaging. After the indicated days/weeks, all mice were killed and lung metastases were analyzed. Mouse nipple implantation was based on a previously published method (Li et al, 2016). Female BALB/c mice were anesthetized and used for this assay. 1 × 105 4T1‐Luc cells were injected through the nipple area into the mammary fat pad. 21 days after injection, luciferin was injected and the primary tumors were analyzed, then the mice were euthanized and analyzed for the acquisition of secondary tumor(s). To deplete CD8+ T cells, mice were injected intraperitoneally with 100 μg of anti‐CD8α (53–6.7) or isotype on days −2, −1 (relative to tumor injection on day 0). All primary/metastatic tumors were detected by bioluminescence imaging (BLI) with the IVIS 100 (Caliper Life Sciences, Hopkinton, MA, USA). The BLI signal intensity was quantified as the sum of photons within a region of interest given as the total flux (photons/s). No randomization and blinding were used for mice experiments. For the EVs education experiments, all mice were treated with 100 μg EVs in 100 μl PBS via tail vein injection every other day for 3 weeks post‐tumor injection. Where indicated, mice were injected i.p. with USP8 inhibitor (1 mg/kg) or paclitaxel (10 mg/kg) post‐tumor injection. At the indicated times, mice were injected i.v. with 150 μg anti‐PD‐L1 (10F.9G2, BioXCell, cat. BE0101) or Rat IgG2b isotype control (BioXCell, cat. BE0090).

Zebrafish embryonic invasion and metastasis assay

In the zebrafish embryo xenograft model, mammalian tumor cells were injected into the zebrafish embryonic blood circulation (Zhang et al, 2012b). Approximately 400 tumor cells labeled with a red fluorescent cell tracer were injected into the blood of 48 h postfertilization (hpf) Fli‐Casper zebrafish embryos at the ducts of Cuvier. After injection, some of the tumor cells disseminate into the embryo blood circulation whilst the rest remain in the yolk. Zebrafish embryos are maintained for 5 days postinjection (dpi) at 33°C, a compromise for both the fish and cell lines. The tumor cells that enter the bloodstream preferentially invade and micrometastases into the posterior tail fin area. Invasion can be visualized as a single cell that has left the blood vessel, which can subsequently form a micrometastasis (3–50 cells). Pictures were taken by confocal microscopy at 1, 3, and 5 dpi, and the percentage of invasion and invasive cluster of cells were counted. Every experiment was repeated at least two times independently.

Isolation of lymphocytes from mice

Lymphocytes from the spleen or lymph nodes were depleted of erythrocytes by hypotonic lysis. To obtain tumor‐infiltrating lymphocytes, tumors were harvested, cut into small fragments, and treated with collagenase and hyaluronidase under agitation for 1 h at 37°C. Lymphocytes were purified by Percoll‐gradient centrifugation and washed with DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS. CD8+ T cells were isolated from spleens or tumors by using magnetic beads (Miltenyl Biotec). Pre‐experiments were conducted to ensure that this treatment did not affect the expression levels of any of the tested markers.

Flow cytometry analysis

For the intracellular cytokine staining, lymphocytes were first stained with anti‐CD3e PE (553063, BD), anti‐CD4 FITC (eBioscience, 11‐0042‐82), anti‐CD8 APC (100712, Biolgend), anti‐PD1 FITC (11‐9981‐82, RMP1‐30, eBioscience), anti‐LAG‐3 FITC (11‐2231‐82, eBioscience), anti‐TIM3 FITC (11‐5870‐82, RMT3‐23, eBioscience) fixed and permeabilized with a Cytofix/Cytoperm kit (554722, BD Biosciences PharMingen), and finally stained with anti‐IFN‐γ PE (12–7311‐81), anti‐GZMB FITC (372206, Biolgend) antibodies in accordance with the manufacturer's instructions. For the analysis of EVs, 20 μg EVs were mixed with 5 μl 4 μm aldehyde/sulphate latex beads (Invitrogen, no. 1743119) in 500 μl 1x PBS for 30 min at room temperature with continuous rotation. EVs‐bound beads were incubated with 1 μg anti‐TβRII APC‐conjugated antibody (no. FAB2411A, R&D) for 30 min. The percentage of positive beads was calculated relative to the total number of beads analyzed per sample (10,000 events). This percentage was therein referred to as the percentage of beads with TβRII+ EVs. All samples were analyzed with Beckman CytoFlex (Beckman) or FACSAria II (Becton Dickinson) machines. FACS data were analyzed with CytExpert software and FlowJo (TreeStar).

Lentiviral transduction and the generation of stable cell lines

Lentiviruses were produced by transfecting HEK293T cells with shRNA‐targeting plasmids and the helper plasmids pCMV‐VSVG, pMDLg‐RRE (gag/pol), and pRSV‐REV. The cell supernatants were harvested 48 h after transfection and were either used to infect cells or stored at −80°C.

To obtain stable cell lines, cells were infected at the low confluence (20%) for 24 h with lentiviral supernatants diluted 1:1 in a normal culture medium in the presence of 5 ng/ml of polybrene (Sigma). At 48 h after infection, the cells were placed under puromycin selection for 1 week and then passaged before use. Puromycin was used at 2 μg ml−1 to maintain MDA‐MB‐231, MCF10A‐RAS, 4T1, and 4T07 derivatives. Lentiviral shRNAs were obtained from Sigma (MISSION® shRNA). Typically, 5 shRNAs were identified and tested, and the two most effective shRNAs were used for the experiment. We used the following shRNAs:

TRCN0000197056 (1#) and TRCN0000195606 (#2) for human TβRII knockdown;

TRCN0000294600 (1#) and TRCN0000294529 (#2) for mouse TβRII knockdown;

TRCN0000284767 (1#) and TRCN0000007435 (#2) for human USP8 knockdown;

TRCN0000030744 (1#) and TRCN0000030747 (#2) for mouse USP8 knockdown.

Transcription reporter assay